Summary

The non-heme iron oxygenase VioC from Streptomyces vinaceus catalyzes Fe(II)- and α-ketoglutarate-dependent Cβ-hydroxylation of L-arginine during the biosynthesis of the tuberactinomycin antibiotic viomycin. Crystal structures of VioC were determined in complexes with the cofactor Fe(II), the substrate L-arginine, the product (2S,3S)-hydroxyarginine (hArg), and the coproduct succinate at 1.1–1.3 Å resolution. The overall structure reveals a β-helix core fold with two additional helical subdomains common to nonheme iron oxygenases of the CAS-like (CSL) superfamily. In contrast to other CAS-like oxygenases, which catalyze the formation of threo diastereomers, VioC produces the erythro diastereomer of Cβ-hydroxylated L-arginine. This unexpected stereospecificity is caused by conformational control of the bound substrate, which enforces a gauche(−) conformer for χ1 instead of the trans conformers observed for the asparagine oxygenase AsnO and other members of the CSL superfamily. Additionally, the substrate specificity of VioC was investigated. The sidechain of the L-arginine substrate projects outward from the active site by making mainly interactions with the C-terminal helical subdomain. Accordingly, VioC exerts broadened substrate specificity by accepting the analogues L-homoarginine and L-canavanine for Cβ-hydroxylation.

Keywords: non-ribosomal peptide synthesis, iron(II)/α-ketoglutarate-dependent oxygenase, Cβ-hydroxylation of L-arginine, viomycin, oxidoreductase

Introduction

The tuberactinomycin family of non-ribosomal peptide antibiotics includes viomycin (tuberactinomycin B) and the capreomycins. These highly basic, cyclic pentapeptides are characterized by the incorporation of nonproteinogenic amino acids such as the L-arginine-derived (2S,3R)-capreomycidine residue or its 5-hydroxy derivative L-tuberactidine (Fig. 1A) [1,2]. The cyclic portion of this residue is essential for antimicrobial activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but the nephrotoxic and ototoxic side effects limit the clinical use of these antibiotics [3]. In addition, the tuberactinomycin antibiotics are applicable for the treatment of bacterial infections caused by vancomycin-resistant enterococci and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains [4]. Since they act by inhibiting bacterial protein biosynthesis, their mode of action concerning the interactions with a variety of ribosomal functions has been studied extensively using the example of viomycin produced by Streptomyces vinaceus [5–8].

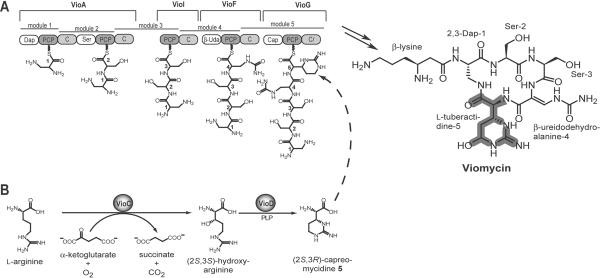

Fig. 1.

Biosynthesis of Viomycin. A) Schematic representation of the viomycin synthetase cluster. The four distinct synthetases VioA, VioI, VioF, and VioG comprise five modules that are subdivided into 14 domains. Each module activates and incorporates one specific precursor into the growing peptide chain. The dashed arrow marks the position where (2S,3R)-capreomycidine is incorporated. After release and macrolactamization the cyclic pentapeptide is modified by the action of several tailoring enzymes present in the viomycin biosynthetic gene cluster resulting in the fully assembled antibiotic viomycin. B) Biosynthesis of (2S,3R)-capreomycidine by the action of VioC and VioD as precursor for the non-ribosomal peptide synthesis.

The biosynthesis of the tuberactinomycin antibiotics proceeds via a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) mechanism combined with the action of so-called tailoring enzymes that act in trans to modify the assembled peptide or to synthesize the building blocks for the NRP synthesis [9,10]. In the case of viomycin, the annotation of the biosynthesis gene cluster revealed six genes encoding for distinct non-ribosomal peptide synthetases of which four synthetases are proposed to be involved in the assembly of the pentapeptide core (Fig. 1A) [4,11]. Recent studies concerning the adenylation domain (A-domain) specificity of VioF revealed a β-ureidoalanine (β-Uda) activation leading to the proposition of a new model for the order of the NRPS's during viomycin biosynthesis [11]. Although module 3 lacks the A-domain, it is postulated that each of the five modules incorporate one residue into the growing peptide chain, whereas the adenylation domain of module 2 activates two molecules of L-serine (Fig. 1A). Another striking feature of these NRPSs is related to the C-terminus of the synthetase VioG. Although there is no need for a further condensation reaction, this NRPS contains a truncated condensation domain with unknown function. Interestingly, no standard thioesterase that catalyzes the cyclization or hydrolysis of the assembled peptide chain is found in the viomycin gene cluster [12].

A large number of NRPS-associated tailoring enzymes encoded by the biosynthesis gene cluster in Streptomyces vinaceus are thought to be involved in the precursor biosynthesis required for viomycin assembly [3,4,11]. Concerning the production of the nonproteinogenic amino acid (2S,3R)-capreomycidine, which is incorporated into the growing peptide chain by the synthetase VioG [13], precursor labeling studies determined that this residue is derived from L-arginine [14]. It was previously shown that two enzymes, VioC and VioD, from the biosynthetic pathway of viomycin catalyze the conversion of free L-arginine to (2S,3R)-capreomycidine via the intermediate (2S,3S)-hydroxyarginine (Fig. 1B) [15–17]. This residue is likely hydroxylated by the non-heme iron oxygenase VioQ as a post-assembly modification yielding the L-tuberactidine residue found in viomycin [4,11,13].

The enzyme VioC, which catalyzes the C3-hydroxylation of L-arginine, shares significant sequence identity to the non-heme iron oxygenase AsnO (~36%) from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) involved in the biosynthesis of CDA [18] and to the trifunctional clavaminate synthase (CAS) from Streptomyces clavuligerus (~33%) that catalyzes the hydroxylation of a β-lactam precursor [19]. All these enzymes are members of the CAS-like (CSL) superfamily of oxygenases that are Fe(II)- and α-ketoglutarate (αKG)-dependent [20].

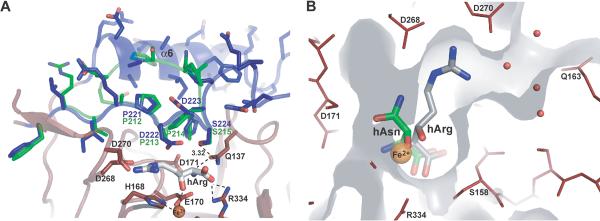

These non-heme iron oxygenases share a common β-helix core fold, the so called jelly roll fold, and are characterized by a 2-His-1-carboxylate facial triad involved in iron coordination [21,22]. Typically, these enzymes catalyze the hydroxylation of unactivated methylene groups where the stereochemistry is retained [23]. The catalytic mechanism of Fe(II)-/αKG-dependent oxygenases has been extensively studied by X-ray crystallography and spectroscopy [20,21]. These studies revealed that iron is activated for dioxygen binding by substrate coordination next to the preformed Fe(II)•αKG•enzyme complex (Fig. 2). The Fe(II)•dioxygen adduct reacts to a Fe(IV)-peroxo or a Fe(III)-superoxo species, which in turn attacks the 2-ketogroup of αKG. The following oxidative decomposition of α-ketoglutarate forms succinate and CO2 and leads to the formation of a Fe(IV)-oxo species that abstracts a hydrogen radical from the unactivated methylene group of the substrate [24,25]. The hydroxyl-group is then transferred to the substrate by radical recombination (Fig. 2) [20,21]. Interestingly, a large number of Cβ-hydroxylations catalyzed by CAS-like enzymes result in the threo diastereomers such as (2S,3S)-hydroxyasparagine produced by AsnO [18], (2S,3S)-hydroxyaspartate generated by SyrP from Pseudomonas syringae [26], or the hydroxylated β-lactam moiety during clavulanic acid biosynthesis [27]. In contrast, it was found that the hydroxylation reaction catalyzed by VioC yields (2S,3S)-hydroxyarginine that corresponds to the erythro diastereomer [15,16]. Furthermore, the two oxygenases MppO from Streptomyces hygroscopicus and AspH from Pseudomonas syringae also catalyze Cβ-hydroxylations which lead to erythro diastereomeric products [26,28].

Fig. 2.

Proposed reaction mechanism for the VioC catalytic cycle. Hydrogen transfer from the β-CH2 group of arginine, by a reactive ferryl-oxo intermediate, yields substrate and Fe(III)-OH radicals that recombine under formation of (2S,3S)-hydroxyarginine.

In this study, we investigated the substrate specificity of the non-heme iron oxygenase VioC and the kinetic parameters for the hydroxylation reaction of the accepted substrates. Furthermore, high-resolution crystal structures of VioC were obtained as complexes with L-arginine, tartrate, and Fe(II) at 1.3 Å resolution, with hArg at 1.10 Å resolution, and with hArg, succinate, and Fe(II) at 1.16 Å resolution. The structural data give first insight into the arrangement of the active site of a CSL oxygenase producing erythro diastereomers of Cβ-hydroxylated compounds. The elucidation of the (2S,3R)-capreomycidine biosynthesis pathway is of great interest as this precursor is incorporated into a large number of antibiotics such as the tuberactinomycin family or streptothricin broad-spectrum antibiotics [29].

Results and Discussion

Overproduction and purification of VioC

The gene from Streptomyces vinaceus coding for VioC (TrEMBL entry Q6WZB0; 358 aa) was expressed as a fusion with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells with a mass of 41.6 kDa. Recombinant VioC was purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography and gel filtration as soluble protein with > 95% purity as displayed by SDS-PAGE analysis with yields of 1.3 mg per liter of bacterial culture. The protein mass was verified by mass spectrometric (MS) analysis.

Substrate specificity and kinetic parameters of VioC

The Cβ-hydroxylation activity of VioC was previously shown by incubating the recombinant enzyme with free L-arginine, FeSO4, and αKG [15]. In addition, the stereochemistry of this hydroxylation reaction was determined by NMR analysis of the product [15] and by comparison of the retention times of the product with synthetic standards by HPLC analysis [16]. Furthermore, D-arginine and NG-methyl-L-arginine were tested as possible substrates for VioC, but hydroxylation could not be detected by HPLC analysis [16]. To determine the substrate specificity of VioC in more detail, the enzyme was incubated with several L-arginine derivatives or several other L-amino acids (Table 1) in the presence of αKG and (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2. HPLC-MS analysis of the reactions revealed the ability of VioC to hydroxylate not only L-arginine but also its derivatives L-homoarginine and L-canavanine (Fig. 3A, Table 1). Apparently, the enzyme tolerates a slightly modified side chain of the substrate. In contrast to this, D-arginine, NG-methyl-L-arginine, NG-hydroxy-nor-L-arginine and all other tested amino acids are not accepted for hydroxylation (Table 1). The kinetic parameters of VioC for its native substrate L-arginine were determined to an apparent KM of 3.40 ± 0.45 mM and a kcat of 2611 ± 196 min−1. This leads to a catalytic efficiency of kcat/KM = 767 ± 183 min−1 mM−1 (Table 1). The enzyme shows a 6.5 fold lower catalytic efficiency in hydroxylating L-homo-arginine (kcat/KM = 118 ± 47.1 min−1 mM−1) and a 12 fold lower catalytic efficiency in the presence of the other nonnative substrate L-canavanine (kcat/KM = 63.3 ± 17 min−1 mM−1) (Table 1). These values clearly demonstrate that L-arginine is the preferred substrate of VioC. It is converted to the hydroxylated form with the highest catalytic efficiency and turnover number kcat. Nevertheless, L-homoarginine and L-canavanine are converted to the hydroxylated derivatives with catalytic efficiencies that are in a similar range as the catalytic efficiency of L-arginine hydroxylation. Some other αKG- and Fe(II)-dependent oxygenases exert comparable catalytic efficiencies. For example, the L-asparagine hydroxylating oxygenase AsnO from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) exhibits a kcat/KM of 620 min−1 mM−1 and the non-heme iron dioxygenase PtlH from Streptomyces avermitilis that catalyzes the hydroxylation of 1-deoxypentalenic acid during pentalenolactone biosynthesis shows a catalytic efficiency of 442 min−1 mM−1 [18,30].

Table 1.

Substrate specificity and kinetic parameters for the hydroxylation reaction catalyzed by VioC

| Substratesa | m/z [M+H]+ substrate | m/z [M+H]+ hydroxylated product | m/z [M+H]+ observedb | Hydroxylation | KM (mM) | kcat (min-1) | kcat/KM (min-1 mM-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Arginine | 175.1 | 191.1 | 191.1 | Yes | 3.40 ± 0.45 | 2611 ± 196 | 767 ± 183 |

| D-Arginine | 175.1 | 191.1 | 175.2 | No | / | / | / |

| L-Homoarginine | 189.1 | 205.1 | 205.0 | Yes | 7.05 ± 2.35 | 831 ± 166 | 118 ± 47.1 |

| L-Canavanine | 177.1 | 193.1 | 193.1 | Yes | 1.16 ± 0.20 | 73.2 ± 3.9 | 63.3 ± 17 |

| NG-Hydroxy- | 177.1 | 193.1 | 177.2 | No | / | / | / |

| nor-L-argimne NG-Methyl-L-arginine | 189.1 | 205.1 | 189.0 | No | / | / | / |

The following L-amino acids were also tested as possible subtrates, but hydroxylation could not be observed: Gln, Phe, Leu, Ile, Trp, Lys, Orn, Asp.

Masses observed by HPLC-MS after 1.5 h incubation of VioC with Fe(II), αKG, and the corresponding substrate.

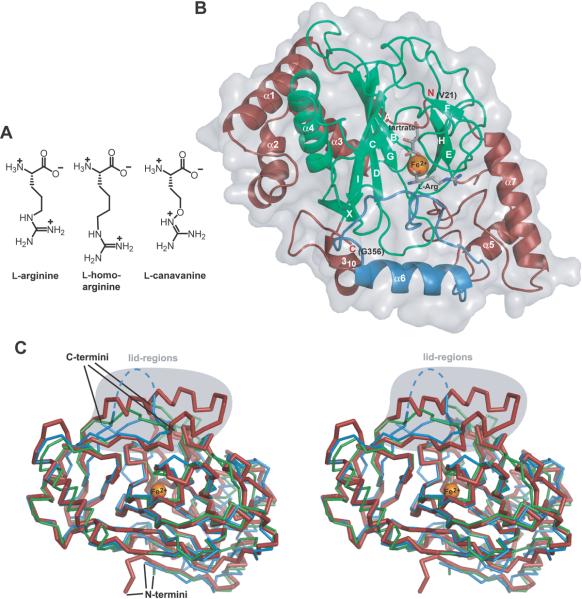

Fig. 3.

A) Chemical structures of the substrates accepted by VioC. B) Overall structure of the substrate complex VioC•L-Arg•tartrate•Fe(II). The β-strands B, G, D, I, and C build the major side of the jelly roll fold and the minor side is built by the β-strands F, E, and H. The flexible lid region is shown in blue, the bound Fe(II) depicted in orange, and the cosubstrate mimic and the substrate are shown in gray. C) A stereo diagram shows the comparison of the ribbon diagram of the VioC•L-Arg•tartrate•Fe(II) complex (red, bold) with the AsnO•hAsn•succinate•Fe(II) complex (green, PDB accession code 2OG7) and with CAS (blue, PDB accession code 1DRY). The position of the iron atom is marked as an orange sphere. The lid regions (VioC: residues F217–P250; AsnO: residues F208–E223; CAS: residues M197–G207 with disordered parts indicated by dashed lines) are highlighted in gray.

Overall structure description

The crystal structure of VioC was solved at 1.3 Å resolution by molecular replacement using the related structure of AsnO [18] as a search model. Crystals of VioC were assigned to space group C2. Each asymmetric unit contains one VioC molecule that was defined for the residues V21–G356. The structure of VioC consists of a core of nine β-strands (A–I) (Table 2), of which eight build up the jelly roll fold that is also found in structures of other members of the CSL oxygenase family. The major sheet of this topology is formed by the five β-strands B, G, D, I, and C and the minor sheet consists of the three β-strands F, E, and H (Fig. 3B). This core is placed between two highly α-helical regions. The N-terminal region (residues V21–L80) contains three helices (α1–α3) and one β-strand (A) parallel to the first β-strand B of the jelly roll core. The linkage of the fourth (E) and fifth (F) β-strand of the jelly roll fold is built up by an extended insert (residues V199–L296) consisting of the helices α5–α7. In addition, two flexible loop regions are found within this insertion (residues F213–R237 and R249–E279) and another loop region bordering the active site is placed between the β-strands C and D (residues V146–D179).

Table 2.

Assignment of secondary structure elements in VioC

| β-Sheets | Residues | α-Helices | Residues | 310-Helix | Residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | S25-F27 | α1 | P31-R47 | 310 | L341-A347 |

| B | A86-R90 | α2 | P54-E66 | ||

| C | T144-V146 | α3 | R69-L80 | ||

| D | D179-L186 | α4 | P112-L128 | ||

| E | T194-G198 | α5 | E206-F213 | ||

| F | Y297-L299 | α6 | R237-D248 | ||

| G | G304-D310 | α7 | E279-S295 | ||

| H | A314-R318 | ||||

| I | W331-T338 | ||||

| X | D130-W134 |

A comparison of the crystal structures of CAS [27], AsnO [18] and VioC (Fig. 3C) shows the high structural similarity of these enzymes with an overall root mean square deviation (rmsd) of 1.32 Å for 169 Cα-positions between VioC and AsnO, and 1.36 Å for 236 Cα-positions between VioC and CAS, respectively (Table 3). These values were obtained by a secondary structure matching alignment with VioC as a reference and demonstrate the high structural relationship in the CSL oxygenase superfamily whose general hallmark is the presence of the two α-helical subdomains in addition to the catalytic jelly roll fold. Although the presence of these α-helical subdomains might be an evolutionary relic at least the C-terminal one is intimately involved in active site formation by bordering therein bound substrate.

Table 3.

SSM alignment of VioC

| Proteina | Organism | PDB | rmsd (Å) | Nalgnb | %sec | Substrate | Catalyzed reaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VioC | Streptomyces sp. ATCC11861 | 2WBO | 0.0 | 358 | 100 | L-arginine | β-hydroxylation |

| AsnO | Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) | 2OG7 [18] | 1.55 | 292 | 36 | L-asparagine | β-hydroxylation |

| clavaminate synthase | Streptomyces clavuligerus | 1DRY [27] | 1.74 | 284 | 33 | proclava-minic acid | hydroxylation/oxi-dative cyclization & desaturation |

| GAB protein | Escherichia coli | 1JR7 [40] | 2.75 | 252 | 15 | n.d.d | n.d.d |

|

| |||||||

| taurine/αKG dioxygenase TauD | Escherichia coli | 1OTJ [41] | 2.49 | 212 | 15 | taurine | oxidative cleavage |

| carbapenem synthase | Erwinia carotovora | 1NX8 [42] | 2.46 | 198 | 19 | carba-penam | epimerization/desaturation |

| alkylsulfatase ATSK | Pseudomonas putida S-313 | 1VZ4 [43] | 2.14 | 189 | 18 | alkyl sulfates | oxidative cleavage |

| AT3G21360 | Arabidopsis thaliana | 1Y0Z [44] | 2.87 | 212 | 14 | n.d.d | n.d.d |

| 2636534 | Bacillus subtilis | 1VRB | 3.95 | 152 | 11 | n.d.d | n.d.d |

Structural alignments were carried out using the SSM server (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/ssm/cgi-bin/ssmserver) with default settings.

Length of alignment Nalgn query and target structures are aligned in 3D on the basis of spatial closeness, minimizing rmsd and maximizing the number of aligned residues.

Sequence identity %seq is a fraction of pairs of identical residues Nident among all aligned in percents: %seq =Nident/ Nalig.

n.d. = not determined.

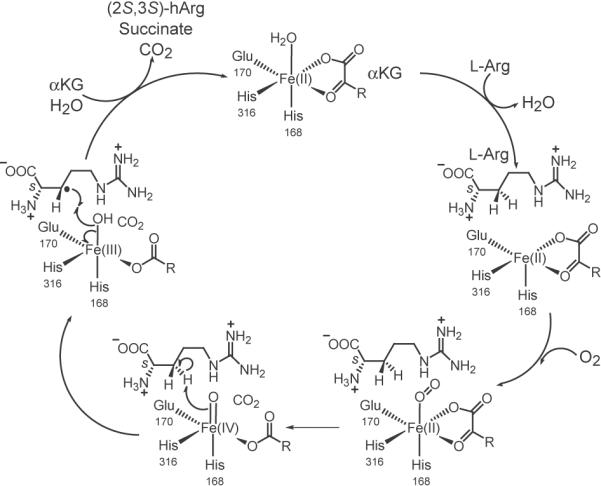

Active Site of VioC

Crystals of the substrate complex were obtained by crystallization of purified VioC in the presence of K-/Na-tartrate yielding a structure at 1.3 Å resolution comprising L-arginine, tartrate, and an iron ion. The positions of the Fe(II)-cofactor, the substrate L-arginine, and the cosubstrate mimic tartrate were clearly indicated by difference electron density map of the active site (Fig. 4A) indicating that iron and L-arginine were copurified during the preparation of recombinant VioC. An iron-free, but (2S,3S)-hydroxyarginine (hArg) containing structure was obtained at 1.1 Å resolution by crystallizing VioC in the presence of citrate and the reaction product hArg. Finally, a structure of the product complex with hArg, succinate, and iron bound to the active site was obtained by cocrystallization of VioC with hArg at 1.16 Å resolution. The active site region is also clearly delineated by atomic-resolution electron density (Fig. 4B, 4C).

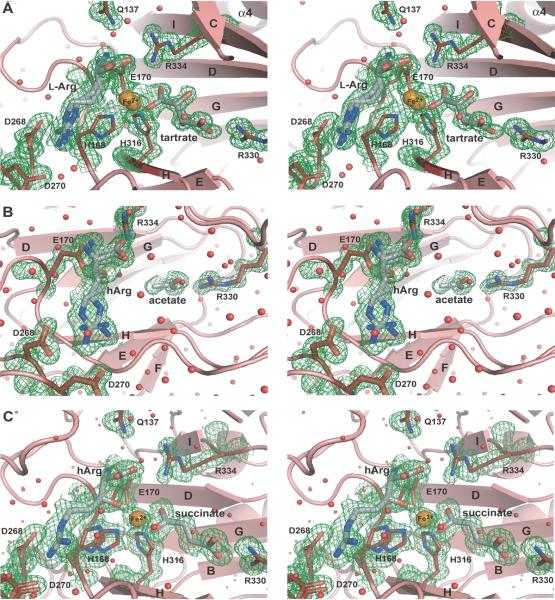

Fig. 4.

Active site of VioC. A) Stereo diagram of the active site of the substrate complex. The 2Fobs-Fcalc electron density (contouring level 1.0 σ ≡ 0.39 e−/Å3) shows the bound iron (orange), tartrate, and L-arginine (gray). Notably, the substrate L-arginine and the iron are coordinated in two different conformations with 75% and 25% occupancy, respectively. B) Stereo diagram of the coordination of hArg in the active site of VioC in the VioC•hArg complex with an overall 80% occupancy for hArg (gray), where each coordinated conformer exhibits 40% occupancy. Additionally, a fragment corresponding to an acetate ion was indicated by the 2Fobs-Fcalc electron density (contouring level 0.8 σ ≡ 0.35 e−/Å3) of the binding site of the αKG cosubstrate. C) Stereo diagram of the active site of the VioC•hArg•succinate•Fe(II) complex with iron shown in orange and hArg and succinate shown in gray. The 2Fobs-Fcalc electron density was calculated with a contouring level of 0.8 σ ≡ 0.35 e−/Å3. Water molecules are depicted as red spheres.

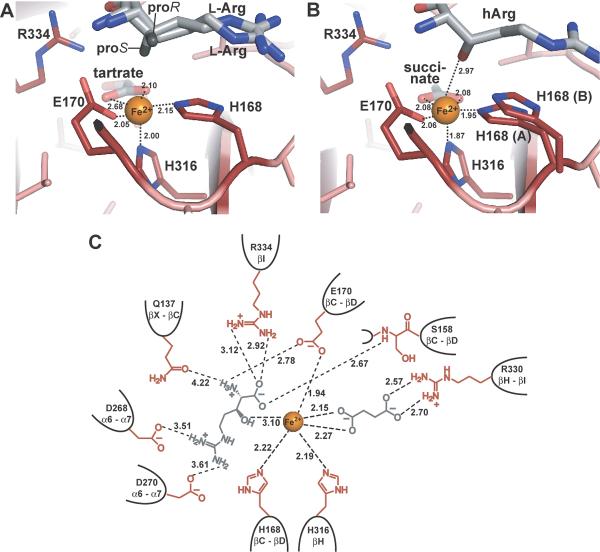

The VioC•L-Arg•Fe(II)•tartrate complex reveals that the ferrous iron is pentacoordinated by one carboxyl group of tartrate and the so called 2-His-1-carboxylate facial triad (Fig. 4A, 5). This iron binding motif (HXD/E…H) is conserved in almost all known non-heme iron-dependent oxygenases [20,21]. In the case of VioC it is made up by the residues H168, E170, and H316. These residues are positioned within the loop linking β-strands C and D (H168 and E170) and on β-strand H (H316) indicating that the iron binding facial triad is located near the minor sheet of the jelly roll fold. Instead of the natural cosubstrate α-ketoglutarate a tartrate molecule is bound in this substrate complex of VioC. As a cosubstrate mimic the tartrate is similarly bound as found before for αKG and succinate in other CSL oxygenases [20,21]. The coordination of the 1-carboxylate of αKG is known to be either trans to the proximal histidine (H168) or trans to the distal histidine (H316) [21]. Accordingly, one carboxyl group of the tartrate coordinates in a monodentate manner to the ferrous iron thus being placed in trans to the distal histidine, whereas the other carboxyl group is bound to VioC via a salt bridge to the guanidinium group of R330 (Fig. 2, 4A, 5A). R330 that forms the salt bridge to the tartrate is conserved in almost all Fe(II)-/αKG-dependent oxygenases and usually located 14–22 residues after the distal histidine [20]. In VioC, this arginine is positioned 14 residues after the distal histidine of the iron binding motif. The iron adopts a distorted octahedral conformation and shows conformational heterogeneity by being found at two positions with approximate occupancies of 75%/25%. As the two positions are split by only 1.1 Å, the presence of an Fe-O species can be excluded in the VioC•L-Arg•Fe(II)•tartrate complex. Interestingly, this heterogeneity for the iron site is also reflected by the nearby bound L-arginine that adopts two different conformers with a ~3:1 ratio in the active site (Fig. 5A, Table 4). Both conformers of the arginine have a strained geometry within the active site by adopting eclipsed rotamers along the χ2 and χ3 torsion angles (Table 4).

Fig. 5.

Interactions in the active site of VioC. A) Coordination of ferrous iron in the substrate complex VioC•L-Arg•tartrate•Fe(II) with the iron ion depicted in orange and L-arginine and tartrate shown in gray. B) Coordination of the iron ion in the active site of the product complex VioC•hArg•succinate•Fe(II). The product hArg and the coproduct succinate are shown in gray. C) Schematic representation of the interactions in the active site of the product complex of VioC. The involved residues are specified by their number in the peptide chain and by the secondary structure element from which they are derived. Distances are indicated in Å and by dashed lines.

Table 4.

Rotamers of bound L-arginine and (2S,3S)-hydroxyarginine in VioC

| Complex | χ1 [°] | χ2 [°] | χ3 [°] | χ4 [°] | Occupancya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VioC·L-Arg·Fe(II)·tartrate | 173.9 | 126.3 | 168.8 | −153.5 | 0.75 |

| −159.9 | 73.7 | 118.9 | 76.4 | 0.25 | |

| VioC·hArg | −168.6 | 159.9 | 148.4 | 177.2 | 0.40 |

| −163.0 | 90.0 | 121.7 | 71.5 | 0.40 | |

| VioC·hArg·Fe(II)·succinate | −160.0 | 91.2 | 126.6 | 60.8 | 0.70 |

Occupancies were optimized to give an absence of the significant 2Fobs-Fcalc electron density and consistent B-factors with surrounding residues.

The structure of the VioC•hArg•Fe(II)•succinate complex shows that the coproduct of the hydroxylation reaction, succinate, is coordinated in a bidentate way to VioC's active site in much the same way as tartrate in the substrate complex (Fig. 4, 5). In electron density maps calculated at 1.16 Å resolution conformational heterogeneity is again observed at the iron binding site, where the side chain of the proximal histidine is found in two alternative conformations. Together with the 1.1 Å structure of the VioC•hArg complex the earlier, chemically assigned (2S,3S)-stereochemistry of the hydroxylation product hArg is now verified [15,16]. The distance between the hydroxylated Cβ methylene group and the catalytic iron is 4.2 Å. In the VioC•L-Arg•Fe(II)•tartrate complex both observed conformers of the substrate are suitably oriented to point with the proS-hydrogen atom of the Cβ group towards the catalytic iron. With an iron-hydroxyl distance of 3.1 Å the structure of the VioC•hArg•Fe(II)•succinate complex indicates a rather loose coordination of the product to the active site iron (Fig. 4C, 5).

Concerning the recognition of L-arginine and hArg by VioC as a substrate and product, respectively, the structures imply two conserved coordination sites for the α-amino group of L-arginine (Fig. 4, 5). The residues Q137 and E170 form a hydrogen bond and salt bridge with the α-amino group, although the carboxyl group of E170 also coordinates the catalytic iron. Furthermore, the carboxyl group of L-arginine forms a salt bridge with the side chain of R334 and a hydrogen bond to the peptide group of residue S158. In addition, the guanidinium group of the L-arginine side chain forms salt bridges to the closely adjoined side chains of the acidic residues D268 and D270.

Lid Region of VioC

Upon substrate binding a flexible, lid-like region (residues F217–P250) shields the active site of VioC. The lid region is completely disordered in the apo-form (residues R220–E251) (data not shown), but becomes ordered after iron and substrate complexation. The product complex of VioC exhibits the same lid organization as the substrate complex, but a comparison with the lid region of AsnO reveals a significantly longer lid region for VioC (Fig. 6A). Here, parts of the lid are coiled up to helix α6 which packs against the extended stretch lining the active site. In contrast to AsnO, where the active site is sealed by a hydrophobic wedge of three consecutive proline residues, the active site of VioC is bordered by only one proline residue (P221) and two aspartate residues (D222 and D223). The side chain of residue D222 apparently stabilizes the guanidinium group of the substrate via long-range electrostatic interactions and so supports the correct orientation of L-arginine in the active site. Another interaction between the lid region and the active site, which was also observed in AsnO, is a hydrogen bond established by the hydroxyl group of the side chain of S224 and the carboxamide group of the side chain of Q137. Residue Q137 is suitably orientated to interact with the α-amino group of L-arginine. These findings indicate that, although the lid regions of AsnO and VioC are indeed conformationally different, a nearly conserved region is involved in active site formation after substrate binding. Interestingly, the disorder of the lid region appears to be increased in the product rather than in the substrate complexes. In the VioC•hArg complex the short stretch T232–Q235 that is about 19 Å distant from the bound hArg is not defined by electron density, as also found for the VioC•hArg•succinate•iron complex where A233–G236 are missing. In addition, the remaining residues of the lid region (R220–D248) exhibit only about 80% occupancy. Overall, this implies that minor changes in the active site exert significant effects on lid motility of this CAS-like oxygenase.

Fig. 6.

Lid-control of substrate binding. A) Comparison of the lid regions of VioC (blue) and AsnO (green). The side chain of residue S224 forms a hydrogen bond to Q137 that coordinates the α-amino group of hArg (distance is indicated in Å). The residues sealing the active site are also specified. B) Superposition of hArg (gray) and hAsn (green) coordination in the active sites of VioC and AsnO. The catalytic iron is shown in orange. Water molecules near the entrance/exit site for substrates and products of VioC are marked in red.

As observed before in several other oxygenases the active site of non-heme iron-dependent oxygenases can be canopied by a flexible lid region upon substrate binding. In the case of CAS, this loop region remains partly disordered although Fe(II), αKG, and the substrate are bound in the active site (Fig. 3C) [27]. In contrast to this finding, the lid region of AsnO becomes ordered upon complexation of iron. Here, the lid region of AsnO shields the active site in the presence of bound product to keep bulk solvent out [18]. Tryptophan oxygenase from chicken, also a non-heme iron enzyme, shows a similar behavior upon tryptophan binding as a substrate. Substrate binding triggers conformational changes to a more closed topology where two loops close around the active site [31]. Another example for canopying the active site is found in the crystal structure of the Fe(II)-/αKG-dependent dioxygenase PtlH from Streptomyces avermitilis. This enzyme shields its active site after substrate binding by an α-helix that stabilizes the bound substrate during catalysis [32].

Substrate and Stereospecificity

As described above, VioC exhibits strong substrate specificity for its native substrate L-arginine, but also tolerates L-homoarginine and L-canavanine (Fig. 3A, Table 1). These findings can be explained by the coordination of L-arginine in the active site of VioC (Fig. 4, 5, 6B). As the stereochemistry of the Cα-atom is crucial to allow the manifold interactions between its α-carboxy and α-amino substituents with the enzyme, only the L-enantiomer can be accomodated in the binding pocket. Another appealing feature is the salt bridges between the guanidinium group of L-arginine and its surrounding residues D268 and D270. With a distance of about 3.5 Å, there is sufficient space in the active site to accommodate at least one additional methylene group in the side chain of L-arginine as exemplified by the binding and catalytic turnover of L-homoarginine. Concerning L-canavanine turnover by VioC, the modified guanidinium group is likely to be analogously bound by the acidic residues D268 and D270. The oxygen atom of L-canavanine (Fig. 3A) that replaces the Cδ methylene group is tolerated, since this position is not directly recognized by the enzyme. The results also indicate why NG-methyl-L-arginine and NG-hydroxy-nor-L-arginine are not acceptable for hydroxylation: Although being directed towards the surface of VioC a terminal methylation or hydroxylation of the guanidinium group sterically interferes with the intimate salt bridge formation to D268 and D270. Altogether, the VioC structures corroborate only partly the predictions made before for the substrate binding residues in the active sites of CSL oxygenases [18], as they differ in regard to the interaction sites with the substrate's side chain.

Most non-heme oxygenases exhibit high substrate specificities. For example the αKG- and Fe(II)-dependent oxygenase AsnO from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) accepts only free L-asparagine as a substrate [18] and the oxygenase SyrP from Pseudomonas syringae converts only L-aspartate tethered as a pantetheinyl thioester to the corresponding peptidyl carrier protein during syringomycin biosynthesis [26]. There also exist examples for a more tolerant substrate recognition. The two oxygenases RdpA and SdpA from Sphingomonas herbicidovorans MH, which are involved in the degradation of phenoxy-alkanoic acid herbicides, recognize either [2-(4-chloro-2-methylphenoxy)propanoic acid] or [2-(2,4-dichlorophenoxy)propanoic acid] with RdpA transforming the (R) enantiomers and SdpA being specific for the (S) enantiomers [33,34]. In addition, the non-heme oxygenase AspH from Pseudomonas syringae hydroxylates free L-Asp, L-Asp-SNAC, and a linear nonapeptide containing an asparagine residue [26].

The stereospecificity with which VioC catalyzes the Cβ-hydroxylation of a nonactivated methylene moiety was unexpected, as it differs from that of other CAS-like oxygenases. Using the obtained atomic-resolution crystal structures the observed erythro specificity of VioC can now be explained. The product (2S,3S)-hydroxyarginine is coordinated to the catalytic iron in a different manner than for example hAsn in the active site of AsnO (Fig. 6B) [18]. VioC forms a channel from the active site to the surface wherein bound hArg is located. In contrast, the side chain of bound hAsn in AsnO is facing inwards of the enzyme complex. The different substrate binding mode is caused by conformational control of the enzyme on the side chain rotamer of the bound substrate. For example, in AsnO a trans conformer is selected for the χ1 torsion angle of bound L-asparagine, whereas in VioC a gauche(−) rotamer is observed for L-arginine (Table 4). Due to the different rotamers adopted by the substrates in the active sites of VioC and AsnO only VioC is capable to direct the proS-hydrogen of its Cβ group toward the ferryl [Fe(IV)=O] intermediate that is formed during catalysis, whereas in AsnO the proR-hydrogen is suitably positioned to be transferred onto the ferryl intermediate.

Conclusions

The assigned stereospecificity of the Cβ-hydroxylation reaction of L-arginine by VioC is now proven by high-resolution crystal structures of both substrate and product complexes. In addition, the observed substrate tolerance of VioC reflects the unusual coordination mode of the substrate within the active site of VioC. The C-terminal α-helical subdomain with its lid region and the α6–α7 loop causes the substrate to adopt a unique χ1-conformer that differs from other related CAS-like oxygenases. This implies a role of at least the C-terminal subdomain in this subclass of αKG-dependent oxygenases in directing substrate conformation and restricting the range of acceptable substrates.

One challenging task for synthetic chemists is still the stereoselective synthesis of β-hydroxylated amino acids, given that these compounds are of significant interest by being found in several antibiotics [18,20,35] and bioactive compounds. To our knowledge, this is the first crystal structure of a CSL oxygenase catalyzing the formation of erythro diastereomeric products. Together with earlier structures of threo diastereomer producing oxygenases like AsnO [18] or CAS [27], there is now sufficient information to reengineer these oxygenases for generating enzymatically new building blocks for natural product biosynthesis. The family of CSL oxygenases demonstrates how conformational control is exerted on bound substrates to control the stereospecificity of the catalyzed reaction.

Experimental Procedures

Protein expression and purification of VioC

The expression plasmid pET28vioC [15] was used to transform E. coli strain BL21(DE3). VioC was overproduced as an N-terminally hexahistidine tagged protein in LB medium supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg mL−1). 500 mL cultures were grown at 37 °C until an OD600 of 0.6 and protein expression was induced with IPTG (0.5 mM). After incubation for 3 h at 30 °C the cells were harvested by centrifugation (7000 rpm, 15 min, 4 °C) and resuspended in 50 mM Hepes pH 8.0 and 300 mM NaCl. The cells were lysed by two passages through an EmulsiFlex-C5 (Avestin) at 10000 psi and VioC was purified by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography using an ÄKTA purifier system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The concentration of the eluent imidazole was changed linearly between 3 and 250 mM. Fractions containing the recombinant protein were identified by 12% SDS-PAGE analysis, pooled, and further purified and dialyzed against either 25 mM Hepes pH 7.0 and 50 mM NaCl or 10 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0 using gel filtration chromatography on a Superdex 75 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The fractions were also analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE and those containing VioC were concentrated and directly subjected to crystallization. The concentration of the protein solution was measured spectrophotometrically at 280 nm using the calculated molar extinction coefficient of VioC (47630 M−1 cm−1).

Determination of enzyme specificity and kinetic parameters

Recombinant VioC (5 μM) was incubated with different substrates (500 μM) (see Table 1), the cosubstrate α-ketoglutarate (1.0 mM), and the cofactor (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2 (1.0 mM) in 10 mM Tris/HCl buffer (pH 8.0) for 1.5 h at 30 °C. The reactions were stopped by adding 4% (v/v) perfluoropentanoic acid. Control reactions were carried out without VioC. The reactions were analyzed via reversed-phase HPLC-MS analysis on a Hypercarb column (Thermo Electron Corporation, pore diameter of 250 Å, particle size of 5 μm, 100% carbon) using the following mobile phases: 20 mM aqueous perfluoropentanoic acid (A), and acetonitrile (B). The following gradient was applied: 0–50% B in 10 min and 50–80% B in 10 min with a flow rate of 0.2 mL min−1 at 20 °C. The ESI-MS analysis of the reaction mixture was performed with an Agilent 1100 MSD (Agilent Technologies) using the positive single-ion monitoring (SIM) mode.

Kinetic parameters were determined by incubating 0.25 μM VioC with 1.0 mM αKG, 1.0 mM (NH4)2Fe(SO4)2, and substrate concentrations between 75 μM and 8.0 mM in 10 mM Tris/HCl buffer (pH 8.0) for 30 s at 30 °C. After stopping the reactions by addition of 4% (v/v) perfluoropentanoic acid they were also analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC-MS using the conditions described above. The kinetic parameters were calculated assuming Michaelis-Menten behavior and using the programs Enzyme Kinetics and Sigma Plot 8.0.

Crystallization of VioC

Crystallization trials were performed at 18 °C by the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method. Crystals of VioC complexed with the substrate L-arginine and the cofactor Fe(II) were obtained in several conditions using the NeXtal Anion Suite kit (Qiagen) and a protein concentration of 8.0 mg/mL in 25 mM Hepes pH 7.0 and 50 mM NaCl. Best crystals were obtained in 1.2 M potassium-/sodium-tartrate, 0.1 M Tris/HCl pH 8.5 without any prior addition of L-arginine or Fe(II). The product complex was achieved by cocrystallization of recombinant VioC with (2S,3S)-hydroxyarginine. The synthesis of this compound was performed enzymatically as described previously [15]. In the cocrystallization experiment 11 mg/mL protein solution in 25 mM Hepes pH 7.0 and 50 mM NaCl and 3 mM (2S,3S)-hydroxyarginine were used for a screening against the NeXtal Anion Suite kit (Qiagen). Again crystals were obtained in several conditions, where the best crystals were achieved in 1.0 M sodium succinate, 0.1 M Tris/HCl pH 8.5 and 0.6 M tri-sodium citrate, 0.1 M Hepes pH 7.5. Additionally, a crystal of the apo-form of VioC was obtained, but it showed strong anisotropic scattering and was hence not finally refined.

Data collection and structure determination

Monoclinic VioC crystals were transferred to a cryoprotection solution containing the mother liquor components and 30% (v/v) glycerol before being flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data sets for the substrate complex were collected at beamline X06SA at SLS, Villigen, Switzerland and data sets for the product complexes were recorded at beamline ID14-4 at ESRF, Grenoble, France. The X-ray data were integrated by XDS and scaled by XSCALE [36]. The crystal structure of the substrate complex of VioC was solved by molecular replacement using MOLREP [37] and a homology model based on the structure of apo-AsnO (PDB accession code 2OG5) [18] whose lid region was truncated (initial R-factor 0.338, correlation coefficient 0.720 for data between 2.8 and 20 Å). Further manual and automatic refinement of this and the other complexes proceeded with COOT and REFMAC5 (Table 5) [38,39]. Anisotropic refinement of B-factors was justified for the product complexes due to the atomic resolution of their datasets and a drop of Rfree of more than 2 %.

Table 5.

Data collection and refinement

| VioC·L-Arg·Fe(II)·tartrate | VioC·hArg | VioC·hArg·Fe(II)·succinate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data processing | |||

| Beam line | XO6SA, SLS | ID14-4, ESRF | ID14-4, ESRF |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9794 | 0.9755 | 0.9795 |

| Detector | PILATUS-6M | ADSC315r | ADSC315r |

| Space group | C2 | C2 | C2 |

| a,b,c(Å);β(°) | 80.63, 67.34, | 80.91,66.83, 62.73; | 80.77, 66.93, |

| 62.42; 108.83 | 109.16 | 62.90; 109.16 | |

| Resolution (Å) | 20.0–1.3 | 20.0–1.10 | 20.0–1.16 |

| Total reflections | 329984 | 448872 | 293649 |

| Unique reflections | 76258 | 123576 | 99570 |

| Completenessa (%) | 98.3 (90.2) | 97.0 (84.9) | 91.3 (65.7) |

| <I> / σ<I>a | 10.1 (2.6) | 14.1 (1.5) | 10.6 (2.1) |

| R merge b | 0.080 (0.631) | 0.040 (0.571) | 0.063 (0.249) |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 12.4 | 9.07 | 9.62 |

| Refinement | |||

| Rworka,c | 0.161 (0.305) | 0.143 (0.293) | 0.132 (0.252) |

| Rfreea,d | 0.212 (0.304) | 0.178 (0.336) | 0.171 (0.293) |

| Used reflections | 74865 | 121303 | 97778 |

| Mean B-factor(Å2) | 17.52 | 14.18 | 13.98 |

| No. of atoms | 2954 | 3232 | 3170 |

| No. water mol. | 288 | 451 | 381 |

| No. heterogens | 13 | 10 | 12 |

| r.m.s.d. from ideal | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 | 0.011 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles (deg.) | 1.13 | 1.45 | 1.36 |

| Torsions (deg.) | 7.54 | 6.79 | 7.20 |

values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shell

Rmerge = Σhkl Σi (Ii(hkl) - <I (hkl) >) / Σhkl Σi Ii(hkl)

Rwork = Σ (Fobs–Fcalc) / Σ(Fobs)

Rfree crystallographic R-factor based on 5.1% of the data withheld from the refinement for cross-validation

RCSB protein data bank accession numbers

Crystal structures and structure factors were deposited in the RCSB under accession numbers 2WBO for the substrate•tartrate•iron complex, 2WBQ for the complex with hArg, and 2WBP for the complex with hArg•succinate•iron.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Alan Tanovic, Florian Peuckert, and Petra Gnau for technical assistance during crystallization. The authors thank A. McCarthy for support at synchrotron beam line ID14-4 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, and S. Russo at X06SA, Swiss Light Source, Villingen. Mohamed A. Marahiel and Lars-Oliver Essen would like to thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) for financial support. Work by Michael G. Thomas was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (AI065850).

Abbreviations

- A-domain

adenylation domain

- αKG

α-ketoglutarate

- β-Uda

β-ureidoalanine

- CAS

clavaminic acid synthase

- CDA

calcium-dependent antibiotic

- CSL

CAS-like

- hArg

(2S,3S)-hydroxyarginine

- hAsn

(2S,3S)-hydroxyasparagine

- HPLC-MS

high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- IPTG

isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- NADH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- Ni-NTA

nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NRPS

non-ribosomal peptide synthetase

- RCSB

Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics

- r.m.s.d.

root mean square deviation

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecylsulfate polyacrylamide gelelectrophoresis

- SSM

secondary structure matching

References

- 1.Bartz QR, Ehrlich J, Mold JD, Penner MA, Smith RM. Viomycin, a new tuberculostatic antibiotic. Am Rev Tuberc. 1951;63:4–6. doi: 10.1164/art.1951.63.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagata A, Ando T, Izumi R, Sakakibara H, Take T. Studies on tuberactinomycin (tuberactin), a new antibiotic. I. Taxonomy of producing strain, isolation and characterization. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1968;21:681–687. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.21.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yin X, O'Hare T, Gould SJ, Zabriskie TM. Identification and cloning of genes encoding viomycin biosynthesis from Streptomyces vinaceus and evidence for involvement of a rare oxygenase. Gene. 2003;312:215–224. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00617-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas MG, Chan YA, Ozanick SG. Deciphering tuberactinomycin biosynthesis: isolation, sequencing, and annotation of the viomycin biosynthetic gene cluster. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2823–2830. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2823-2830.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liou YF, Tanaka N. Dual actions of viomycin on the ribosomal functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;71:477–483. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90812-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marrero P, Cabanas MJ, Modolell J. Induction of translational errors (misreading) by tuberactinomycins and capreomycins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;97:1047–1042. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)91481-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Modolell J, Vazquez The inhibition of ribosomal translocation by viomycin. Eur J Biochem. 1977;81:491–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johansen SK, Maus CE, Plikaytis BB, Douthwaite S. Capreomycin binds across the ribosomal subunit interface using tlyA-encoded 2'-O-methylations in 16S and 23S rRNAs. Mol Cell. 2006;23:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marahiel MA, Stachelhaus T, Mootz HD. Modular Peptide Synthetases Involved in Nonribosomal Peptide Synthesis. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2651–2674. doi: 10.1021/cr960029e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh CT, Chen H, Keating TA, Hubbard BK, Losey HC, Luo L, Marshall CG, Miller DA, Patel HM. Tailoring enzymes that modify nonribosomal peptides during and after chain elongation on NRPS assembly lines. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2001;5:525–534. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barkei JJ, Kevany BM, Felnagle EA, Thomas MG. Investigations into Viomycin Biosynthesis by Using Heterologous Production in Streptomyces lividans. Chembiochem. 2009;10:366–376. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohli RM, Walsh CT. Enzymology of acyl chain macrocyclization in natural product biosynthesis. Chem Commun (Camb) 2003:297–307. doi: 10.1039/b208333g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fei X, Yin X, Zhang L, Zabriskie TM. Roles of VioG and VioQ in the incorporation and modification of the Capreomycidine residue in the peptide antibiotic viomycin. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:618–622. doi: 10.1021/np060605u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter JH, 2nd, Du Bus RH, Dyer JR, Floyd JC, Rice KC, Shaw PD. Biosynthesis of viomycin. II. Origin of beta-lysine and viomycidine. Biochemistry. 1974;13:1227–1233. doi: 10.1021/bi00703a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ju J, Ozanick SG, Shen B, Thomas MG. Conversion of (2S)-arginine to (2S,3R)-capreomycidine by VioC and VioD from the viomycin biosynthetic pathway of Streptomyces sp. strain ATCC11861. Chembiochem. 2004;5:1281–1285. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin X, Zabriskie TM. VioC is a non-heme iron, alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent oxygenase that catalyzes the formation of 3S-hydroxy-L-arginine during viomycin biosynthesis. Chembiochem. 2004;5:1274–1277. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin X, McPhail KL, Kim KJ, Zabriskie TM. Formation of the nonproteinogenic amino acid 2S,3R-capreomycidine by VioD from the viomycin biosynthesis pathway. Chembiochem. 2004;5:1278–1281. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strieker M, Kopp F, Mahlert C, Essen LO, Marahiel MA. Mechanistic and structural basis of stereospecific Cbeta-hydroxylation in calcium-dependent antibiotic, a daptomycin-type lipopeptide. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:187–196. doi: 10.1021/cb700012y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen SE, Paradkar AS. Biosynthesis and molecular genetics of clavulanic acid. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1999;75:125–133. doi: 10.1023/a:1001755724055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hausinger RP. FeII/alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent hydroxylases and related enzymes. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:21–68. doi: 10.1080/10409230490440541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clifton IJ, McDonough MA, Ehrismann D, Kershaw NJ, Granatino N, Schofield CJ. Structural studies on 2-oxoglutarate oxygenases and related double-stranded beta-helix fold proteins. J Inorg Biochem. 2006;100:644–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruijnincx PC, van Koten G, Klein Gebbink RJ. Mononuclear non-heme iron enzymes with the 2-His-1-carboxylate facial triad: recent developments in enzymology and modeling studies. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:2716–2744. doi: 10.1039/b707179p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldwin JE, Field RA, Lawrence CC, Merritt KD, Schofield CJ. Proline 4-hydroxylase: stereochemical course of the reaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:7489–7492. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffart LM, Barr EW, Guyer RB, Bollinger JM, Jr., Krebs C. Direct spectroscopic detection of a C-H-cleaving high-spin Fe(IV) complex in a prolyl-4-hydroxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14738–14743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604005103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price JC, Barr EW, Hoffart LM, Krebs C, Bollinger JM., Jr. Kinetic dissection of the catalytic mechanism of taurine:alpha-ketoglutarate dioxygenase (TauD) from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8138–8147. doi: 10.1021/bi050227c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh GM, Fortin PD, Koglin A, Walsh CT. beta-Hydroxylation of the aspartyl residue in the phytotoxin syringomycin E: characterization of two candidate hydroxylases AspH and SyrP in Pseudomonas syringae. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11310–11320. doi: 10.1021/bi801322z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Z, Ren J, Stammers DK, Baldwin JE, Harlos K, Schofield CJ. Structural origins of the selectivity of the trifunctional oxygenase clavaminic acid synthase. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:127–133. doi: 10.1038/72398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haltli B, Tan Y, Magarvey NA, Wagenaar M, Yin X, Greenstein M, Hucul JA, Zabriskie TM. Investigating beta-hydroxyenduracididine formation in the biosynthesis of the mannopeptimycins. Chem Biol. 2005;12:1163–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinkus KJ, Tann CH, Gould SJ. The biosynthesis of the streptolidine moiety in streptothricin F. Tetrahedron. 1983;39:3493–3505. [Google Scholar]

- 30.You Z, Omura S, Ikeda H, Cane DE. Pentalenolactone biosynthesis. Molecular cloning and assignment of biochemical function to PtlH, a non-heme iron dioxygenase of Streptomyces avermitilis. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6566–6567. doi: 10.1021/ja061469i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Windahl MS, Petersen CR, Christensen HE, Harris P. Crystal structure of tryptophan hydroxylase with bound amino acid substrate. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12087–12094. doi: 10.1021/bi8015263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.You Z, Omura S, Ikeda H, Cane DE, Jogl G. Crystal structure of the non-heme iron dioxygenase PtlH in pentalenolactone biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36552–36560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706358200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muller TA, Fleischmann T, van der Meer JR, Kohler HP. Purification and characterization of two enantioselective alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases, RdpA and SdpA, from Sphingomonas herbicidovorans MH. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:4853–4861. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02758-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller TA, Zavodszky MI, Feig M, Kuhn LA, Hausinger RP. Structural basis for the enantiospecificities of R- and S-specific phenoxypropionate/alpha-ketoglutarate dioxygenases. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1356–1368. doi: 10.1110/ps.052059406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kershaw NJ, Caines ME, Sleeman MC, Schofield CJ. The enzymology of clavam and carbapenem biosynthesis. Chem Commun (Camb) 2005:4251–4263. doi: 10.1039/b505964j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kabsch W. Automatic Processing of Rotation Diffraction Data from Crystals of Initially Unknown Symmetry and Cell Constants. J. Appl. Cryst. 1993;26:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Cryst. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collaborative Computing Project Number 4 The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chance MR, Bresnick AR, Burley SK, Jiang JS, Lima CD, Sali A, Almo SC, Bonanno JB, Buglino JA, Boulton S, Chen H, Eswar N, He G, Huang R, Ilyin V, McMahan L, Pieper U, Ray S, Vidal M, Wang LK. Structural genomics: a pipeline for providing structures for the biologist. Protein Sci. 2002;11:723–738. doi: 10.1110/ps.4570102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Brien JR, Schuller DJ, Yang VS, Dillard BD, Lanzilotta WN. Substrate-induced conformational changes in Escherichia coli taurine/alpha-ketoglutarate dioxygenase and insight into the oligomeric structure. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5547–5554. doi: 10.1021/bi0341096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clifton IJ, Doan LX, Sleeman MC, Topf M, Suzuki H, Wilmouth RC, Schofield CJ. Crystal structure of carbapenem synthase (CarC) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20843–20850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213054200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muller I, Kahnert A, Pape T, Sheldrick GM, Meyer-Klaucke W, Dierks T, Kertesz M, Uson I. Crystal structure of the alkylsulfatase AtsK: insights into the catalytic mechanism of the Fe(II) alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase superfamily. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3075–3088. doi: 10.1021/bi035752v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bitto E, Bingman CA, Allard ST, Wesenberg GE, Aceti DJ, Wrobel RL, Frederick RO, Sreenath H, Vojtik FC, Jeon WB, Newman CS, Primm J, Sussman MR, Fox BG, Markley JL, Phillips GN., Jr. The structure at 2.4 A resolution of the protein from gene locus At3g21360, a putative Fe(II)/2-oxoglutarate-dependent enzyme from Arabidopsis thaliana. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2005;61:469–472. doi: 10.1107/S1744309105011565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]