Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic value of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and assess the correlation between the volume of the ischemic lesion and neurobehavioral status during the subacute stage of ischemic stroke. Ischemic stroke was induced in 6 healthy laboratory beagles through permanent occlusion of the middle cerebral artery (MCAO). T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), measurement of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) ratio, and neurobehavioral evaluation were performed 3 times serially by using a 1.5-T MR system: before and 3 and 10 d after MCAO. Ischemic lesions demonstrated T2 hyperintensity, FLAIR hyperintensity, and DWI hyperintensity. The ADC ratio was decreased initially but then was increased at 10 d after MCAO. Ischemic lesion volumes on T2-weighted and FLAIR imaging were not significantly different from those on DWI. The lesion volume and neurobehavioral score showed strong correlation. Our results suggest that conventional MRI may be a reliable diagnostic tool during the subacute stage of canine ischemic stroke.

Abbreviations: ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PWI, perfusion-weighted imaging

In human medicine, stroke is a leading cause of adult mortality and neurologic disability worldwide.1 Strokes previously were thought to be uncommon in small animals, but the true prevalence is unknown.4 These events are now recognized more frequently in dogs because of increased use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).5,14,17

Because the infusion of thrombolytic agents, such as urokinase or tissue plasminogen activator, within 3 to 6 h of the onset symptoms is effective in restoring blood flow and improving stroke outcome in humans,19 the detection of early ischemic changes is now thought to be necessary to improve patient outcome. Computed tomography and conventional MRI are not sufficiently sensitive to predict the presence and extent of ischemic damage during the acute stage after a stroke.12,20 Therefore several MRI sequences, such as fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI), and MR angiography, have been developed for early diagnosis and subsequent follow-up of ischemic stroke.3 High-field magnetic strengths (at least 1.5 T) are necessary to perform these sequences.

In contrast to the situation in humans, ischemic stroke in many dogs is diagnosed during the subacute stage—24 h to 6 wk after the vascular insult—due to the time lag between the onset of clinical signs to referral and to the lack of standard diagnostic protocols for ischemic stroke in dogs. In most reports of strokes in dogs, the median interval between the onset of neurologic dysfunction and performance of an MRI was more than 2 d.5,14,17 Whereas DWI has marked sensitivity to very early ischemic changes in the brain, T2-weighted and FLAIR images gradually become more hyperintense later (that is, during the first 24 h after the insult).3 Therefore, hyperintensity on T2-weighted and FLAIR images is believed to be representative of mature lesions.15 In light of these findings, we hypothesized that conventional MR sequences, such as T2-weighted and FLAIR imaging as well as DWI would be used for the diagnosis of the subacute stage of ischemic stroke in dogs.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic value of MRI and assess the correlation between the volume of ischemic lesions and neurobehavioral status during the subacute stage of ischemic stroke in dogs. We therefore investigated the lesion volume of T2-weighted and FLAIR images compared with that on DWI images. Furthermore, we assessed the relationship between the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) of the ischemic lesions and the neurobehavioral status of the dogs.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

The study population comprised 6 healthy laboratory beagles (2 male and 4 female, 2- to 3 y old, weighing 10 to 13 kg; Harlan Interfauna, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, UK) were used. All of the dogs were healthy without history of neurologic disease; they had no signs of neurologic problems on physical examination. They were screened for metabolic diseases by means of a complete blood count and serum chemistry analysis. After arrival to our facility, the beagles were acclimated and assessed daily for neurobehavioral abnormalities and general health status for 2 wk. Each dog was housed under a controlled photoperiod (lights on, 0800 to 2000) in a single cage and fed twice daily with commercial dry food (Science Diet, Hill's Pet Nutrition, Topeka, KS), and fresh water was supplied continuously by automatic dispensers. Room temperature was 18 to 24 °C, with a relative humidity of 55% ± 10% and 8 air changes per hour. The quarantine and housing measures for dogs were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Konkuk University (Seoul, South Korea), which also approved the surgical procedures and experimental protocol. The approved study endpoint was 10 d after MCAO. After completion of the imaging studies at 10 d after induction of stroke, all dogs were euthanized with sodium pentobarbital (80 mg/kg IV; Entobar Injection, Hanrim Pharm, Gyeonggi, Korea). The brains were carefully removed, and the occlusion site was identified.

In addition to the study population, 3 healthy laboratory beagles (1 male and 2 female, age, 2 to 3 y; weight, 10 to 12 kg; Harlan Interfauna, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, UK) were included as a control group. Control beagles were maintained, evaluated, and underwent surgery according to the same procedures as described for study animals, except that control dogs did not undergo MCAO.

Animal preparation, monitoring, and surgical procedure.

Dogs were fasted for 12 h before the induction of anesthesia, premedicated with atropine (0.02 mg/kg SC; Atropine sulfate, Je-Il Pharm, Daegu, South Korea) and acepromazine (0.2 mg/kg IM; Sedaject, Samu Median, Chungnam, South Korea), anesthetized 30 min after premedication by using propofol (5 mg/kg IV; Anepol, Hana Pharm, Gyeonggi, South Korea), orally intubated, and mechanically ventilated. Anesthesia was maintained with isoflurane (Attane, Minrad, Orchard Park, NY) at 2% to 3% of the inspired volume during surgery. The oxygen delivery and ventilation rates were monitored continuously and adjusted as needed to maintain heart rate, blood oxygen saturation and blood pH within normal limits. Rectal temperature was monitored continuously and maintained at 37 to 38 °C throughout surgery.

Cerebral ischemia was induced by MCAO as previously described.9 Briefly, a cervical incision was made, and then the right internal and external carotid arteries were exposed. An embolus was made previously by attaching silicone (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) to the end of silk suture (4–0; B Braun Medical Industries, Penang, Malaysia). The size of the silicone embolus was standardized by curing for 24 h in the tip of a 20-gauge venous catheter (Becton Dickinson Korea, Gyeongbuk, South Korea). Synthetic emboli were inserted through the internal carotid artery to the origin of the MCA, and then the neck incision was sutured. Delivery of the embolus was confirmed by arterial backflow in the syringe. The MCAO remained in place in all dogs until they were euthanized.

Postsurgical management.

After surgery, the dogs recovered from anesthesia in cages in the animal recovery room. Recirculating warm water blankets were placed beneath a portion of their cages, and the dogs were observed continuously until they had recovered fully (about 24 h). At 24 h after surgery, they were transported to the holding area and monitored periodically until euthanasia. Ampicillin (20 mg/kg PO every 12 h; Ampi-10, Unibiotech, Gyeonggi, South Korea) was administered to the dogs for 1 wk to prevent bacterial infection. The incision site was examined and cleaned as needed until healed. To control pain, butorphanol (0.4 mg/kg IM; Butophan, Myungmoon Pharm, Seoul, South Korea) was given as needed, usually twice a day for the first 3 to 5 d after surgery.

Neurobehavioral scoring.

Neurobehavioral scoring was performed by modifying a standardized categorical rating scale.16 The scoring was performed for motor function (1, no deficit; 2, hemiparetic but able to walk; 3, stands only with assistance; 4, hemiplegic and unable to stand; 5, comatose or dead, not testable), consciousness (1, normal; 2, mildly reduced; 3, severely reduced; 4, comatose or dead), head turning (0, absent; 1, posturing and turns toward side of infarct; 2, unable to lift head, comatose, or dead), circling (0, absent; 1, present; 2, unable to walk or dead), and hemianopsia (0, absent; 1, present; 2, unable to test because of reduced consciousness or death). According to this scoring system, a completely normal dog would have a total score of 2, and a dog with the most severe deficits (comatose or dead) would have a total score of 15. Each dog was evaluated prior to MCAO and 3 and 10 d after MCAO.

MRI protocol.

Imaging was performed with a 1.5-T MR system (Magnetom Avanto, Siemens AG, Berlin, Germany). The scans were performed serially on 3 occasions for each ischemic model: before and 3 and 10 d after MCAO. All images were acquired in the transverse orientation. The MR protocol included T2-weighted, FLAIR, and DWI images. T2-weighted images were acquired by using a turbospin echo sequence with a repetition time of 6980 ms, echo time of 86 ms, 30 sections, 3-mm slice thickness, field of view of 15 × 15 cm, and 512 × 512 matrix. The FLAIR sequence had a repetition time of 8670 ms, echo time of 115 ms, inversion time of 2500 ms, 30 sections, 3-mm slice thickness, field of view of 15 × 15 cm, and 512 × 512 matrix. Each of the transverse slices obtained with spin–echo DWI (repetition time/echo time 2900/108 ms, 3-mm slice thickness, field of view of 16.7 × 16.7 cm, and 256 × 256 matrix) was acquired with b values of 0 and 1000 s/mm2 along all 3 orthogonal (x, y, z) axes. Blood gases, glucose, and hematocrit were measured at each time MRI sequences were performed.

Image analysis.

An experienced neurologist and radiologist, without knowledge of the clinical data, each examined the T2-weighted, FLAIR, and DWI images independently. The ischemic lesions were measured on a separate workstation by using imaging software (MRIcro, Chris Rorden, Columbia, SC). For T2-weighted and FLAIR images, the areas of abnormal hyperintensity were traced on each slice. To measure the lesion size on DWI scans, a region of interest was drawn to include all voxels with an abnormal appearance on the b1000 image. These areas of abnormal hyperintensity were summed and multiplied with the section thickness plus the interslice gap to calculate the lesion volume.

Measurement of ADC.

From the DWI images, ADC trace maps were calculated by averaging the acquisition in 3 directions using computer software (DPTools, Denis Ducreux, Paris, France). To calculate the mean ADC of the ischemic lesion, the region of interest outlining the hyperintensity of the lesion on the DWI images was transferred to the corresponding ADC map. Ratios were calculated based on the ADC of the ischemic area and corresponding contralateral region.

Evaluation of ischemic area by TTC staining.

At the end of the study, the brains were carefully removed and dissected into 2-mm coronal sections. The fresh brain slices were immersed in a 2% solution of 2, 3, and 5-triphenyl-tetrazolium chloride (TTC; Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in normal saline at 37 °C for 30 min. The volume of ischemic lesion was determined as the product of average slice thickness (2-mm) and the sum of lesion volume in all brain slices calculated by using image analysis software (PhotoShop 4.0, Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise stated. Paired t tests were used for comparison of the lesion volumes identified by MRI scans and the lesion volume, ADC ratio, and neurobehavioral score at 3 and 10 d after MCAO. In addition, unstained lesions on TTC staining were compared volumetrically with the abnormal lesions on the MRI scans. Spearman rank correlations between the neurobehavioral status and both lesion volume and ADC ratio were calculated. Statistical significance was set at a P value of less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed by using a statistical software package (SAS version 12.0, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Control dogs (n = 3), which underwent surgery without MCAO, showed no abnormalities in physiologic, imaging, or neurobehavioral parameters (data not shown).

Physiologic parameters.

In all dogs, physiologic parameters were well maintained before and at 3 and 10 d after MCAO (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physiologic parameters of 6 experimented dogs examined before and 3 and 10 d after MCAO

| Before |

3 d |

10 d |

||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| PaO2 (mm Hg) | 98.5 | 8.4 | 96.4 | 7.8 | 97.1 | 10.2 |

| PaCO2 (mm Hg) | 36.3 | 3.1 | 38.8 | 3.3 | 37.1 | 5.8 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 43.6 | 2.2 | 47.8 | 6.3 | 46.5 | 5.3 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 98.5 | 12.9 | 104.8 | 13.7 | 107.2 | 8.6 |

| Temperature (°C) | 38.8 | 1.1 | 38.2 | 0.6 | 37.9 | 0.7 |

PaO2, partial pressure of arterial oxygen; PaCO2, partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide

Neurobehavioral deficits.

Dogs showed neurologic signs of telencephalic or diencephalic lesions, including reduced responsiveness, head turning and circling in an ipsilateral direction to the lesion, walking into walls, contralateral hemiparesis, hemianopsia, and unilateral hemineglect. Mean neurobehavioral scores (Table 2) decreased between 3 and 10 d after MCAO (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

ADC ratios, neurobehavioral scores, and lesion volumes in 6 experimented dogs evaluated by T2-weighted, FLAIR, and DWI imaging at 3 and 10 d after MCAO

| 3 d |

10 d |

|||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Lesion volume (mL) | ||||

| T2 | 3.44 | 2.96 | 3.26 | 3.13 |

| FLAIR | 4.39 | 3.79 | 3.89 | 3.70 |

| DWI | 4.81 | 4.15 | 2.97 | 3.16 |

| ADC ratio | 0.77 | 0.08 | 1.13 | 0.14 |

| Neurobehavioral score | 4.83 | 1.94 | 3.83 | 1.47 |

Image analysis.

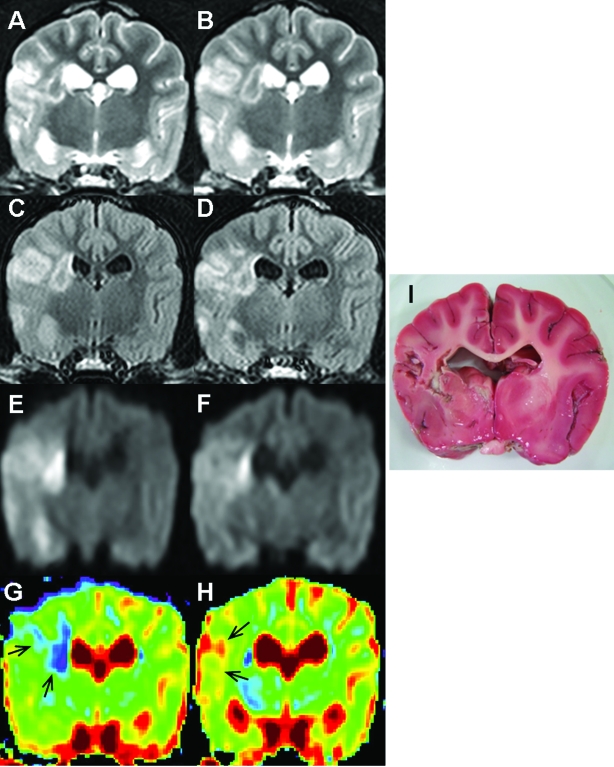

MRI examinations revealed unilateral, striatocapsular, and cerebral cortex lesions demonstrating T2 hyperintensity, FLAIR hyperintensity, and DWI hyperintensity (Figure 1 A through F). Compared with T2-weighted images, FLAIR images had decreased signal due to cerebrospinal fluid, allowing better visualization of periventricular lesions. The ADC values for the ischemic lesions decreased (Figure 1 G). The mean ADC of ischemic lesions was 77% lower than that of corresponding areas of the contralateral hemispheres at 3 d after MCAO. However, the ADC ratios were increased at 10 d after MCAO (Figure 1 H). These abnormal lesions noted on the MRI scans were not stained by TTC (Figure 1 I). The lesion volume on TTC staining (3.15 ± 3.06 mL) matched well with the lesion volume on T2-weighted, FLAIR, and DWI images (P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

MR images of the brain of a dog with permanent MCAO. Images A, C, E, and G were obtained at 3 d after MCAO; images B, D, F, and H were obtained at 10 d after MCAO. T2 hyperintensity (A and B), FLAIR hyperintensity (C and D), and DWI hyperintensity (E and F) were found in the right cerebral cortex and at striatocapsular lesions. Compared with T2-weighted images, FLAIR imaging showed suppression of signal from cerebrospinal fluid, thereby allowing better visualization of periventricular lesions. These lesions were decreased at 10 d after MCAO. The ADC value for the ischemic lesions was decreased on the ADC map at 3 d after MCAO (G; arrows, blue region) but increased at 10 d after MCAO (H; arrows, red region). The ADC ratio of the lesion was 0.79 at 3 d after MCAO and 1.06 at 10 d after MCAO. These abnormal lesions noted by using MRI were atrophied and did not stain with TTC (I).

The mean ADC ratios and lesion volumes measured on T2-weighted, FLAIR, and DWI scans are summarized in Table 2. The mean lesion volume was largest on the DWI and FLAIR scans at 3 and 10 d after MCAO. However lesion volumes among 3 different MR scans did not differ significantly at 3 and 10 d after MCAO, respectively. The volume of the ischemic lesion on DWI images decreased (P < 0.05) and the ADC ratio increased (P < 0.01) between 3 and 10 d after MCAO. The change in the mean volume of the lesions on the T2-weighted and FLAIR scans did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05).

Correlation between neurobehavioral status and ischemic lesion volume and ADC ratio.

Spearman rank correlations between neurobehavioral status and both lesion volume and ADC ratio during the subacute stage of ischemic stroke are shown in Table 3. There was a strong correlation between the volume of the lesion identified on each MRI scan and the neurobehavioral score (r ≥ 0.90, P < 0.05). However, the ADC ratio and neurobehavioral score did not correlate significantly (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Spearman rank correlations between the neurobehavioral score and lesion volumes and the ADC ratio of 6 experimented dogs during the subacute stage of ischemic stroke

| Neurobehavioral score |

||||

| 3 d after MCAO |

10 d after MCAO |

|||

| r | P | r | P | |

| Lesion volume | ||||

| T2-WI | 0.90 | 0.04 | 0.93 | 0.04 |

| FLAIR | 0.90 | 0.04 | 0.93 | 0.04 |

| DWI | 0.99 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 0.04 |

| ADC ratio | −0.60 | 0.21 | 0.75 | 0.08 |

Discussion

Our results showed that conventional MR sequences, including T2-weighted and FLAIR images as well as DWI, were useful imaging methods for the detection of ischemic lesions during the subacute stage of ischemic stroke. The volume of the lesions did not differ significantly among the 3 imaging modalities. In addition, a strong correlation between lesion volume and neurobehavioral status was demonstrated.

Diffusion-weighted imaging measures the restricted motion of water molecules from the intracellular space (that is, cytotoxic edema formation) in brain tissue.7 This modality has become a key imaging method for the detection of ischemic injury and for characterization of the development of acute and subacute stages of stroke.21 The decrease in the ADC of water in ischemic brain tissue causes a signal increase in the DWI.8 The observed signal intensity is influenced initially by cytotoxic edema secondary to ischemia and later by vasogenic edema.2 Cytotoxic (intracellular) edema may be evident by 1 h after a stroke, but its detection with T2-weighted and FLAIR scans may be difficult at this time.7 Vasogenic (extracellular) edema is associated principally with T2 relaxation time, and its identification with conventional MRI may be subtle within the first 24 h of a stroke.2,7 Therefore, conventional MRI has been considered useful for the description of the mature lesion and vasogenic edema but was not believed to be sensitive enough for the early detection of acute ischemic tissue damage.21

In this study, because we performed MR scans more than 3 d after stroke, ischemic lesions were identified easily on T2-weighted, FLAIR, and DWI images. Because the volume of the lesions detected did not differ significantly between the imaging modalities, conventional MR sequences can be a useful diagnostic tool during the subacute stage of ischemic stroke in dogs. In all embolized dogs, lesion volumes decreased between 3 and 10 d after MCAO, whereas the ADC ratio increased. Further, between 3 and 10 d after MCAO, the changes in lesion volume by DWI and ADC ratio were statistically significant. The decrease in the volume of the ischemic lesions over these 7 d likely reflects atrophy in the infarcted hemisphere and a diminution in volume due to decreased brain swelling. This reversibility of volume has been established previously in animal models and clinical reports.6,10,13 To confirm this hypothesis, additional studies with a larger sample size are needed.

In humans, the ADC ratio ranges from 0.5 to 0.8 during an acute stroke.12,20 In the examined dogs, the mean ADC ratio was 0.77 ± 0.08 at 3 d after MCAO and 1.13 ± 0.14 at 10 d thereafter. Generally, ADC values remain below normal over the first 8 to 10 d after a stroke and progress to pseudonormal and supranormal values (due to cellular necrosis or lysis) at chronic intervals beyond 10 d, making it possible, to some extent, to estimate the age of the infarct.1,3 These findings correspond to the results of the present study. Necropsy and TTC staining confirmed the atrophic or necrotic lesions were related to the increase in the ADC value.

Until recently, the predictive value of the volume of lesions on the MRI with respect to the clinical severity during the subacute stage of ischemic stroke had been unclear.15,18 In the present study, lesion volumes on the T2-weighted, FLAIR, and DWI images were significantly related to the neurobehavioral status of the dogs. These findings may have been due to the location of the infarct. Generally, the neurologic deficits associated with ischemic stroke are associated strongly with the branch of the cerebral artery that is occluded and the location of the resulting ischemic injury. Therefore, the more regions of the brain that are injured from the ischemic attack, the more likely the presence of neurobehavioral signs. If the dogs had seizures, their neurobehavioral status would be more severely affected, even in dogs with small brain lesions. However, seizures are an uncommon manifestation of ischemic stroke in dogs5,17 and did not occur in any of the dogs in the present study.

In the current study, the ADC ratio was not related to the neurobehavioral status of the dogs. Generally, the ADC value is related to the severity and extent of neuronal damage and the degree of regional metabolic alterations.11,12 It has usually been reported to be lower at the core of the lesion than at its periphery.20 In the examined dogs, the ADC varied widely among various locations within the ischemic lesions.

In summary, the volume of ischemic lesions on T2-weighted and FLAIR scans did not different significantly from that on DWI scans. Therefore when advanced MR techniques, such as DWI, PWI, and MR angiography, and high-field magnetic strengths cannot be used, conventional MRI is a legitimate alternative diagnostic option during the subacute stage of ischemic stroke. In addition, the volume of the ischemic lesion was correlated significantly with the neurobehavioral status during the subacute phase after stroke. Therefore, measuring the volume of the lesion by using MRI may provide useful information for the management and evaluation of dogs with ischemic stroke.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grant (R11-2002-103) funded by the South Korea government (MEST) and by the Bio R&D program through the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (M10530010001-06N3001-00110) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology.

References

- 1.Aronen HJ, Laakso MP, Moser M, Perkiö J. 2007. Diffusion- and perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging techniques in stroke recovery. Eura Medicophys 43:271–284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen PE, Simon JE, Hill MD, Sohn CH, Dickhoff P, Morrish WF, Sevick RJ, Frayne R. 2006. Acute ischemic stroke: accuracy of diffusion-weighted MR imaging—effects of b value and cerebrospinal fluid suppression. Radiology 238:232–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garosi LS. 2007. Imaging of cerebrovascular accidents, p 368–369. In: Proceedings of the 25th American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine Forum, Seattle, WA, Jun 6-9 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garosi LS, McConnell JF. 2005. Ischaemic stroke in dogs and humans: a comparative review. J Small Anim Pract 46:521–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garosi L, McConnell JF, Platt SR, Barone G, Baron JC, de Lahunta A, Schatzberg SJ. 2006. Clinical and topographic magnetic resonance characteristics of suspected brain infarction in 40 dogs. J Vet Intern Med 20:311–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant PE, He J, Halpern EF, Wu O, Schaefer PW, Schwamm LH, Budzik RF, Sorensen AG, Koroshetz WJ, Gonzalez RG. 2001. Frequency and clinical context of decreased apparent diffusion coefficient reversal in the human brain. Radiology 221:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hillock SM, Dewey CW, Stefanacci JD, Fondacaro JV. 2006. Vascular encephalopathies in dogs: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Compendium 28:208–217 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoehn M, Nicolay K, Franke C, van der Sanden B. 2001. Application of magnetic resonance to animal models of cerebral ischemia. J Magn Reson Imaging 14:491–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang BT, Lee JH, Jung DI, Park C, Gu SH, Jeon HW, Jang DP, Lim CY, Quan FS, Kim YB, Cho ZH, Woo EJ, Park HM. 2007. Canine model of ischemic stroke with permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion: clinical and histopathological findings. J Vet Sci 8:369–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kidwell CS, Saver JL, Mattiello J, Starkman S, Vinuela F, Duckwiler G, Gobin YP, Jahan R, Vespa P, Kalafut M, Alger JR. 2000. Thrombolytic reversal of acute human cerebral ischemic injury shown by diffusion–perfusion magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol 47:462–469 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight RA, Dereski MO, Helpern JA, Ordidge RJ, Chopp M. 1994. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of evolving focal cerebral ischemia: comparison with histopathology in rats. Stroke 25:1252–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee DH, Kang DW, Ahn JS, Choi CG, Kim SJ, Suh DC. 2005. Imaging of the ischemic penumbra in acute stroke. Korean J Radiol 6:64–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li F, Silva MD, Liu KF, Helmer KG, Omae T, Fenstermacher JD, Sotak CH, Fisher M. 2000. Secondary decline in apparent diffusion coefficient and neurological outcomes after a short period of focal brain ischemia in rats. Ann Neurol 48:236–244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McConnell JF, Garosi LS, Platt SR. 2005. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of presumed cerebellar cerebrovascular accident in 12 dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 46:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peeling J, Corbett D, Del Bigio MR, Hudzik TJ, Campbell TM, Palmer GC. 2001. Rat middle cerebral artery occlusion: correlations between histopathology, T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging, and behavioral indices. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 10:166–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purdy PD, Devous MD, Batjer HH, White CL, Meyer Y, Samson DS. 1989. Microfibrillar collagen model of canine cerebral infarction. Stroke 20:1361–1367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossmeisl JH, Jr, Rohleder JJ, Pickett JP, Duncan R, Herring IP. 2007. Presumed and confirmed striatocapsular brain infarctions in 6 dogs. Vet Ophthalmol 10:23–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schiemanck SK, Post MWM, Witkamp Th D, Kappelle LJ, Prevo AJH. 2005. Relationship between ischemic lesion volume and functional status in the 2nd week after middle cerebral artery stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 19:133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaibani A, Khawar S, Shin W, Cashen TA, Schirf B, Rohany M, Kakodkar S, Carroll TJ. 2006. First results in an MR imaging-compatible canine model of acute stroke. Am J Neuroradiol 27:1788–1793 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Everdingen KJ, van der Grond J, Kappelle LJ, Ramos LMP, Mali WPTM. 1998. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in acute stroke. Stroke 29:1783–1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber R, Ramos-Cabrer P, Hoehn M. 2006. Present status of magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy in animal stroke models. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 26:591–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]