Abstract

Background

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is an important risk factor of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes (T2DM). Previous studies have suggested an inverse relationship between physical activity and MetS. However, these findings were inconsistent; and few investigators have examined these associations among South Americans. We estimated the prevalence of MetS and its association with leisure time physical activity (LTPA) among Peruvian adults.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study of 1,675 individuals (619 men and 1056 women) was conducted among residents in Lima and Callao, Peru. Information about LTPA, socio-demographic, and other lifestyle characteristics were collected by interview. The presence of MetS was defined using the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) criteria.

Results

Overall, the prevalence of MetS was 26.9% and was more common among women (29.9%) than men (21.6%). Habitual participation in LTPA was associated with a 23% reduced risk of MetS (OR=0.77; 95% CI: 0.60–1.03). There was an inverse trend of MetS risk with amount of LTPA (p=0.016). Compared with non-exercisers, those who exercised < 150 minutes/week had a 21% reduced risk of MetS (AOR= 0.79; 95% CI 0.60–1.04). Individuals who exercised ≥ 150 minutes/week, compared with non-exercisers, had a 42% reduced risk of MetS (AOR=0.58; 95% CI: 0.36–0.93). Associations of similar magnitudes were observed when men and women were studied separately.

Conclusion

These data document a high prevalence of MetS and suggest an association with LTPA among urban dwelling Peruvians. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm these observations and to examine interventions that may promote increased physical activity in this population.

Keywords: Metabolic Syndrome, Physical Activity, Peru

Background

Chronic diseases accounts for 60% of all deaths globally, more than double the number of deaths caused by infectious diseases, maternal and perinatal conditions, and nutritional deficiencies combined [1]. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is now recognized as the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in developing countries [2]. Metabolic syndrome (MetS), a constellation of metabolic abnormalities, is an important risk factor of CVD and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) (3). Previous studies have suggested an inverse relationship between physical activity and MetS [3–5]. However, these were inconsistent and few have examined these associations among populations outside of North America, Europe and Asia. This gap in literature is particularly evident for South American populations where the prevalence of obesity, and physical inactivity have increased with economic growth and development [6, 7] and rapid urbanization [8]. Peru, for instance, has emerged as one South American country that has undergone considerable economic growth and has had concomitant increases in the prevalence of CVD risk factors [7]. To date, we are aware of only four studies documenting the prevalence of MetS among Peruvians [6, 9–11]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no published reports that evaluated the relationship between physical activity and MetS in Peru.

In light of the increasing burden of CVD in developing countries [12], increases in the prevalence of CVD risk factors such as physical inactivity and obesity, and the scarcity of cardiovascular epidemiology studies conducted among South Americans, we estimated the prevalence of MetS and it association with leisure time physical activity (LTPA) among Peruvian adults. Results from our study will help in developing evidence-based health promotion and disease prevention programs that are relevant to South American population.

Materials and methods

Design and Participants

Study subjects were Peruvian men and women who participated in the Prevalencia de Factores de Riesgo de Enfermedades No-Transmissibles (Prevalence of Risk Factors for Non Transmissible Diseases) referred to as the FRENT study. The primary objective of the FRENT study was to determine the prevalence and risk factors associated to non-transmissible diseases among residents in Lima and Callao, Peru. Investigators used a multistage, probabilistic stratified sampling strategy to identify and recruit participants for the study. Using maps of n Lima and Callao, investigators grouped the 31 metropolitan districts of Lima in five strata based on their economic profiles. A three-stage sampling strategy was then implemented within each strata. Briefly, within each strata, blocks were selected at random (stage 1), then households were selected at random from blocks; and finally after household census were taken, one member of each sampled household was randomly selected to participate in an in-person interview and medical exam. Individuals < 15 years of age, those who reported less than 12 month residence status in Lima, and women who were pregnant at the time of sampling were ineligible for inclusion in the FRENT study. Approximately 71% of individuals who were invited to participate in the study elected to do so. For the study described here, we excluded subjects < 18 years of age. The final analyzed sample included 1,675 individuals (619 men and 1056 women) FRENT study participants after the exclusion of 96 participants.

Data Collection and Variable Specification

Each participant was interviewed by a trained interviewer using a structured questionnaire validated by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) for assessing the prevalence of non transmissible disease (NTD) risk factors [13]. The questionnaire inquired about individuals’ participation in leisure time physical activity during a typical week. Participants were queried about the number of days per week they engaged in moderate physical exercise (e.g., riding a bicycle or swimming at a leisurely pace) and the amount of time engaged in such activities each week. Information about age, gender, educational attainment, and medical history was also obtained via in-person interviews. Height and weight were measured with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes. Waist circumference was measured from the midpoint between the iliac crest and the lower ribs measured at the sides. Hip circumference was measured at the point of the maximum circumference over the buttocks. After participants had been seated for at least 5 minutes, and again after 30 minutes during the interview a resting blood pressure was measured using a Mercury Desk Sphygmomanometer, these two values were averaged. A follow-up visit to participants’ home was made the next morning to collect a blood sample after a 12-hour fast. Aliquots of serum were used to determine participants’ fasting glucose concentrations and lipid profiles. Serum triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), glucose, and insulin were measured at the Peruvian National Institute of Health Laboratory in Lima, Peru. TG concentrations were determined by standardized enzymatic procedures using glycerol phosphate oxidase assay. HDL-C was measured by a chemical precipitation technique using dextran sulfate. Participants’ fasting serum glucose (FSG) was determined using standardized glucose oxidase method (glucose oxidase GOD-PAP). All laboratory assays were completed without knowledge of participants’ medical history. Lipid, lipoprotein and FSG concentrations were reported as mg/dl.

For the present analysis, participants were classified as being engaged in LTPA (yes vs. no). Those who were engaged in LTPA were further classified as having inadequate or adequate amount of weekly exercise. Inadequate and adequate weekly exercise categories were created in accordance with the recommendation by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), the American Health Association (AHA), and the 1996 US Surgeon General’s Report on Physical Activity and Health. Briefly these organizations recommend that individuals participate in at least 30 minutes of modest physical activity, most if not all, days of the week [14–16]. Total minutes per week spent engaging in LTPA were classified in to three categories using cut-points used previously [17]: (1) no exercise (0 min/week), (2) inadequate LTPA (< 150 minutes/week), and (3) adequate LTPA (>150 min/wk). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as kg/m2. Overweight and obesity were defined as a participant with BMI between 25–29.99 kg/m2 and ≥30 kg/m2, respectively. In accordance with the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) of the National Cholesterol Education Program [18, 19] MetS was defined when three or more of the following attributes were present: 1) mean value of systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥130 mmHg, mean value of diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥85 mmHg; 2) abdominal obesity (waist circumference >102 cm in men and >88 cm in women); 3) low HDL-C (< 40mg/dl in men and < 50mg/dl in women); 4) TGs ≥150mg/dl; 5) FSG ≥100mg/dl or current anti-diabetic medication use [20].

All subjects provided informed consent and all rresearch protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of National Institute of Health in Peru, Dos de Mayo Hospital, Peru and the Human Subjects Division at the University of Washington, USA.

Statistical Analyses

We first explored frequency distributions of socio-demographic, clinical and behavioral characteristics of subjects. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard error of means (SEM). Categorical variables were expressed as number (percent, %). Chi-Square tests were used to evaluate differences in the distribution of categorical variables for study groups. Student’s t tests were used to evaluate differences means for study groups. Logistic regression procedures were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and confidence intervals (CI) of MetS according to differing levels of LPTA. Confounding factors were evaluated on the basis of their hypothesized relationship with variables representing LPTA (e.g., the dichotomous LPTA variable [yes/no]; or level of exercise [none/inadequate/adequate weekly exercise]. In multivariate analysis, tests for linear trend across increasing categories of LTPA were conducted by treating the three-level LTPA variable as a continuous variable [21]. Confounding was assessed by entering potential covariates into a logistic regression model one at a time, and by comparing the adjusted and unadjusted ORs. Final logistic regression models included covariates that altered unadjusted ORs by at least 10% [21]. Logistic regression analyses were repeated for men and women separately. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 14.0, SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) software. All reported p-values are two tailed and confidence intervals were calculated at the 95% level.

Results

Metabolic characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Overall, the prevalence of MetS was 26.9% and was more common among women (29.9%) than men (21.6%). The mean systolic blood pressure was higher for men than for women. Men had higher abdominal obesity (i.e., waist circumference) as compared with women. Fasting serum glucose concentrations were similar for both groups. TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C concentrations of were higher, on average, for women as compared with men. However, mean TG concentrations were higher among men than women.

Table 1.

Clinical and Metabolic Characteristics of the Study Population, Lima, Peru 2006

| Characteristics | Women (N=1056) |

Men (N=619) |

*P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| BMI (Kg/m2) | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 9(0.9) | 12(1.9) | <0.001 |

| Normal (18.5 – 24.9) | 438(41.5) | 231(37.3) | |

| Overweight (25.0 – 29.9) | 374(35.4) | 272(43.9) | |

| Obese (>30.0) | 235(22.3) | 104(16.8) | |

| Metabolic Syndrome | |||

| No | 740(70.1) | 485(78.4) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 316(29.9) | 134(21.6) | |

| Mean ±SE | Mean ± SE | ||

| Waist Circumference(cm) | 89.2 ± 0.4 | 92.4 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 99.9 ± 0.4 | 99.0 ± 0.3 | 0.064 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 188.1 ± 1.3 | 181.6 ± 1.6 | 0.002 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 48.5 ± 0.4 | 42.7 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 118.8 ± 1.0 | 115.2 ± 1.3 | 0.035 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 131.8 ± 2.8 | 155.3 ± 4.1 | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (g/dL) | 90.1 ± 0.9 | 90.1 ± 1.0 | 0.778 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 115.1 ± 0.5 | 121.1 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 72.1 ± 0.3 | 76.1 ± 0.4 | <0.010 |

P-value from Chi-Square test for categorical variables or from Student’s t-test for continuous variables.

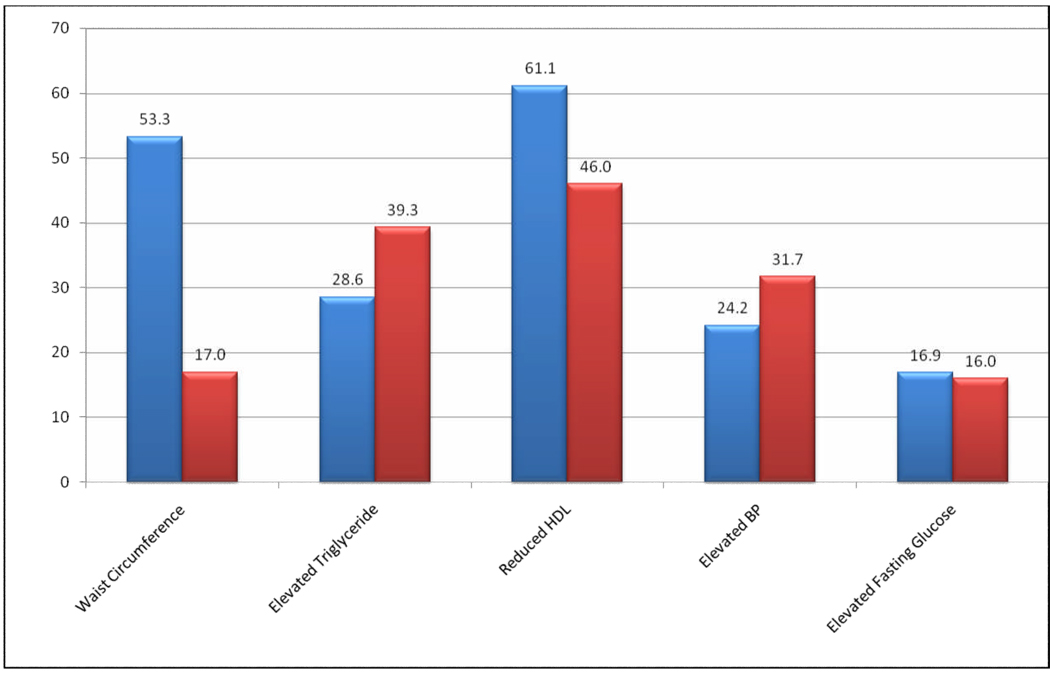

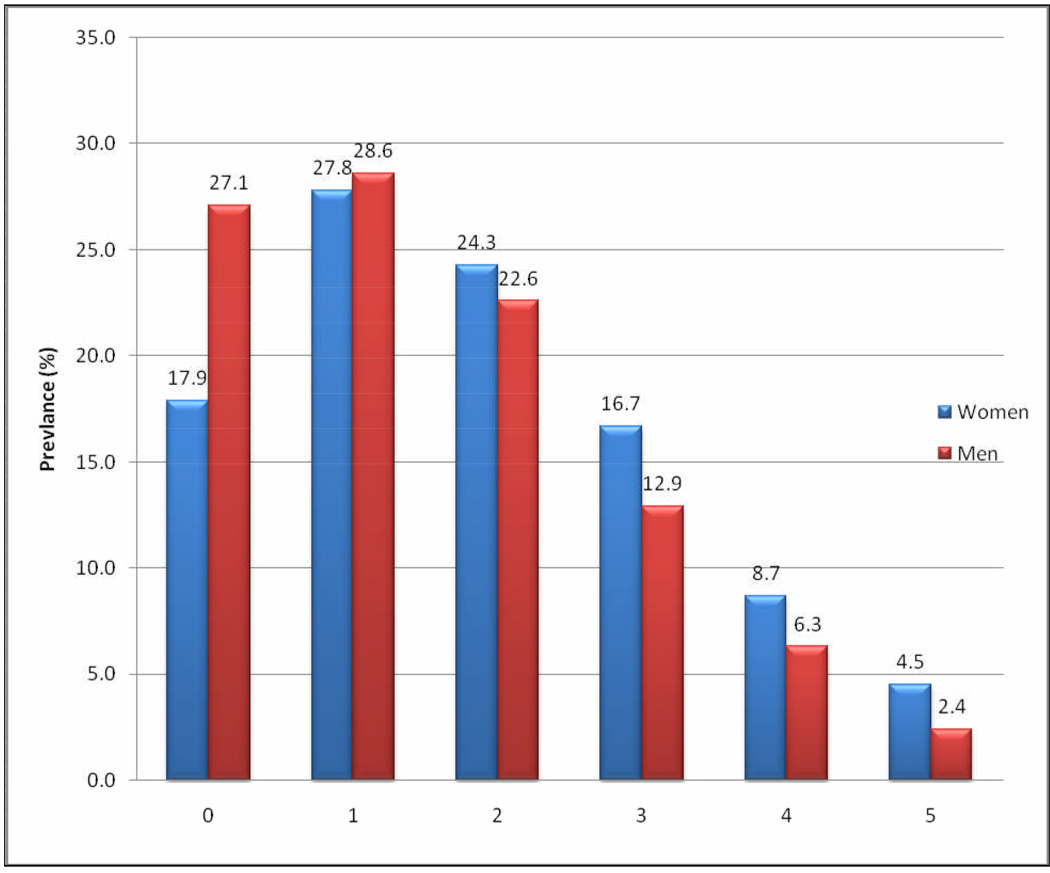

The prevalence of each component of MetS is summarized in Figure 1. Reduced HDL-C (61.1%) and abdominal obesity (53.3%) were the most common MetS components among women; whilst reduced HDL-C (46.0%) and elevated TG concentrations (39.3%) were most common among men. Abdominal obesity was far less common among men as compared with their female counterparts (17.0% vs. 53.3%). Figure 2 shows the presence of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 components of MetS among men and women. Overall, women had increased numbers of MetS components compared with men.

Figure 1. Prevalence of Each Component of Metabolic Syndrome.

*Metabolic syndrome components: 1) mean value of systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥130 mmHg, mean value of diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 85 mmHg; 2) abdominal obesity (waist circumference >102 cm in men and >88 cm in women); 3) low HDLC (< 40mg/dl in men and < 50mg/dl in women); 4) TGs ≥150mg/dl; 5) FSG ≥100mg/dl or current anti-diabetic medication use.

Figure 2.

Number of Metabolic Syndrome components by gender

Women with MetS, as compared with those without the syndrome were older (p<0.001) and less well educated (p<0.001) (Table 2). Men with MetS, as compared with their counterparts without the syndrome, were older (p<0.001), less well educated (p<0.001), were more likely to have ever smoked cigarettes (p=0.031), and were less likely to report habitual engagement in adequate levels of LTPA (p=0.05).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Study Population According to Metabolic Syndrome, Lima, Peru 2006

| Among Women | Among Men | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Syndrome | Metabolic Syndrome | |||||||||

| No (N = 740) |

Yes (N = 316) |

No (N = 485) |

Yes (N = 134) |

|||||||

| Characteristics | n | % | n | % | p-value* | n | % | n | % | P-value* |

| Age (Years) | ||||||||||

| ≤ 24 | 149 | 20.1 | 5 | 1.6 | <0.001 | 132 | 27.2 | 4 | 3.0 | <0.001 |

| 25–34 | 206 | 27.8 | 36 | 11.4 | 128 | 26.4 | 21 | 15.7 | ||

| 35–44 | 182 | 24.6 | 66 | 20.9 | 85 | 17.5 | 27 | 20.1 | ||

| 45–54 | 111 | 15.0 | 77 | 24.3 | 56 | 11.5 | 36 | 26.9 | ||

| 55–64 | 54 | 7.3 | 76 | 24.1 | 42 | 8.7 | 28 | 20.9 | ||

| ≥65 | 38 | 5.2 | 56 | 17.7 | 42 | 8.7 | 18 | 13.4 | ||

| Education† | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| ≤ 6 years | 100 | 14.0 | 91 | 29.4 | 50 | 10.6 | 20 | 15.3 | ||

| 7–12 years | 343 | 48.0 | 132 | 42.6 | 240 | 50.8 | 43 | 32.8 | ||

| >12 years | 272 | 38.0 | 87 | 28.1 | 182 | 38.6 | 68 | 51.9 | ||

| Ever smoked | 0.273 | 0.031 | ||||||||

| No | 627 | 84.7 | 259 | 82.0 | 279 | 57.5 | 63 | 47.0 | ||

| Yes | 113 | 15.3 | 57 | 18.0 | 206 | 42.5 | 71 | 53.0 | ||

| Current smoker | 0.651 | 0.4024 | ||||||||

| No | 670 | 90.5 | 283 | 89.6 | 337 | 69.5 | 88 | 65.7 | ||

| Yes | 70 | 9.5 | 33 | 10.4 | 148 | 30.5 | 46 | 34.3 | ||

| Leisure time physical activity | 0.080 | 0.112 | ||||||||

| No | 161 | 21.8 | 85 | 26.9 | 139 | 28.7 | 48 | 35.8 | ||

| Yes | 579 | 78.2 | 231 | 73.1 | 346 | 71.3 | 86 | 64.2 | ||

|

Adequacy of leisure time physical activity |

0.097 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| No exercise | 161 | 21.8 | 85 | 26.9 | 139 | 28.7 | 48 | 35.8 | ||

| Inadequate: <150 min/week | 501 | 67.7 | 207 | 65.5 | 283 | 58.3 | 77 | 57.5 | ||

| Adequate: ≥ 50 min/week | 78 | 10.5 | 24 | 7.6 | 63 | 13.0 | 9 | 6.7 | ||

P-value from Chi-Square tests

Numbers/percentages may not add up to the total number due to missing data

Habitual participation in LTPA was associated with a 23% reduced risk of MetS (OR= 0.77 95%CI: 0.60–0.98) (Table 3). The association was attenuated slightly after adjustment for age, education, smoking status and gender (AOR = 0.79; 95% CI: 0.60–1.03), and became insignificant. There was an inverse trend of MetS risk with amount of LTPA (p-value for linear trend=0.016). Compared with non-exercisers, those who exercised <150 minutes/week had a 21% reduced risk of MetS (AOR = 0.79; 95% CI 0.60–1.04). Individuals who exercised ≥150 minutes/week, compared with non-exercisers, had a 42% reduced risk of MetS (AOR = 0.58; 95% CI: 0.36–0.93). Associations of similar magnitudes were observed when men and women were studied separately.

Table 3.

Distributions of Study Participants and Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) for Metabolic Syndrome According to Leisure Time Physical Activity, Lima, Peru 2006.

| Engagement in Leisure Time Physical Activity (LTPA) |

Metabolic Syndrome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N=1225) |

Yes (N=450) |

Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|||

| N | % | n | % | |||

| All | ||||||

| No | 300 | 24.5 | 133 | 29.6 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference)* |

| Yes | 925 | 75.5 | 317 | 70.4 | 0.77(0.60–0.98) | 0.79(0.60–1.03) |

| Inadequate: <150 min/week | 784 | 64.0 | 284 | 63.1 | 0.81(0.64–1.04) | 0.79(0.60–1.04) |

| Adequate: ≥ 50 min/week | 141 | 11.5 | 33 | 7.3 | 0.52(0.34–081) | 0.58(0.36–0.93) |

| p for trend | 0.004 | 0.016 | ||||

| Among Men |

No (N=485) |

Yes (N=134) |

||||

| No | 139 | 28.7 | 48 | 35.8 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference)** |

| Yes | 346 | 71.3 | 86 | 64.2 | 0.72(0.48–1.07) | 0.86(0.55–1.33) |

| Inadequate: <150 min/week | 283 | 58.3 | 77 | 57.5 | 0.78(0.52–1.19) | 0.90(0.57–1.41) |

| Adequate: ≥ 50 min/week | 63 | 13.0 | 9 | 6.7 | 0.41(0.19–0.89) | 0.61(0.27–1.39) |

| p for trend | 0.027 | 0.318 | ||||

| Among Women |

No (N=740) |

Yes (N=316) |

||||

| No | 161 | 21.8 | 85 | 26.9 | 1.00(Reference) | 1.00 (Reference)*** |

| Yes | 579 | 78.2 | 231 | 73.1 | 0.76(0.56–1.02) | 0.73(0.52–1.03) |

| Inadequate: <150 min/week | 501 | 67.7 | 207 | 65.5 | 0.78(0.57–1.06) | 0.75(0.53–1.07) |

| Adequate: ≥ 50 min/week | 78 | 10.5 | 24 | 7.6 | 0.58(0.34–0.98) | 0.63(0.35–1.11) |

| p for trend | 0.031 | 0.067 | ||||

Adjusted for age, education, and gender

Adjusted for age, education and smoking

Adjusted for adjusted for age and education

Discussion

The results of this study confirm and expand the literature in multiple ways. First, study findings confirm a high prevalence of the syndrome (26.9% overall). Second, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported examination of the association between the prevalence of MetS and LTPA among Peruvians. Habitual participation in LTPA was associated with a 21% reduced risk of MetS and we noted an inverse trend of MetS risk with amount of LTPA (p=0.016). Individuals who exercised ≥ 150 minutes/week, compared with non-exercisers, had a 42% reduced risk of MetS (AOR = 0.58; 95% CI: 0.36–0.93). Associations of similar magnitudes were observed when men and women were studied separately. These findings have important public and clinical implications as populations in developed and developing countries, like Peru, experience new challenges five the obesity epidemic.

Few studies have investigated the prevalence of MetS among South Americans. We are aware of only four published reports documenting the prevalence of MetS among Peruvians [9–11, 22]. Soto et al, in their cross sectional study of adults in the Lambayeque, a northern district of Lima, reported prevalence estimates of 29.9% among women and 23.1% among men [11]. More recently, Medina-Lezama et al, recently reported prevalence estimates of 23.2% among women and 14.3% among men who reside in Arequipa, the second largest city in Peru. [9]. These estimates were largely corroborated by Lorenzo et al, who reported MetS prevalence estimates of 25.6% and 11.5% among female and male residents of low-income coastal districts in Lima [22]. MetS prevalence estimates from our population-based sample of Peruvians residing in Lima and Callao (29.9% for women and 21.6% for men) are largely similar to those reported by Soto et al [11]. Differences in estimated MetS prevalence across studies may be attributed to variations in population characteristics, sampling strategies, methods of data collection, and diagnostic criteria used for across studies [9].

Our observations of inverse associations of MetS with LPTA are consistent with some [23–26], though not all [3, 27] previous reports. Ford et al, in their cross-sectional study of US adults reported an inverse trend of MetS among men and women who exercised[17]. The magnitude of observed associations in their study and our present study are comparable with the magnitude of associations reported in prospective cohort studies [23, 28]. Over the last years, Peru has seen an increased epidemiological and nutritional transition that changed the morbidity and mortality profile of the country[12]. This is in part due to the rapid urbanization which is accompanied by the increased access to energy-dense industrialized foods [29] and technological changes that lead to reduced physical activity [30]. Although a large body of evidence has clearly demonstrated that physical inactivity as an important modifiable risk factor for MetS among populations in North America and Europe [4, 5], data regarding the relation between physical activity and Mets is inexistent in Peru. Ramirez-Vargas and colleagues in their study among male adults in Oaxaca, Mexico reported that physical activity as an independent protective factor of MetS (OR=0.40 95%CI p<0.001) [25]. Similarly Sofi et al in Italy reported a statistically significant association between leisure time physical activity and MetS components (P<0.05) [26]. Ma et al in their national survey among employed populations in China reported a significantly reduced risk of metabolic syndrome with increased physical activity [4]. Oguma and Shioda-Tagawa [5], in their meta-analysis of 23 studies conducted in industrialized countries, reported a significant reduction risk of CVD with physical activity among women. Furthermore, the investigators noted that inactive women would benefit by even slightly increasing their physical activity which could be walking 1hour per week or less [5]. Our findings and those of others, however, are dissimilar to reports from other teams of investigators [3, 27]. For instance, Dalacorte et al, in their study of elderly Brazilians reported no associations of MetS with physical activity [3]. Despite differences in study subject characteristics and operational definitions of leisure time physical activity, our study results are in agreement with these previous reports that showed physical activity to be an important protective factor for MetS [4, 5, 25, 26]

Strengths of our study include the extensive CVD risk-factor data available for study participants, and the unique opportunity to assess these risk factors in a population-based sample representative of adult residents of Lima, Peru. Limitations of our study include the cross-sectional design, which precludes our ability to define the temporal relation between participants’ habitual LPTA and incident MetS. Additionally, physical activity was based on self-report and thus is subject to errors and is less accurate than objective measures of physical activity (e.g., by accelerometers[31] or cardio-respiratory fitness[32]). Objective measures of physical activity and cardio-respiratory fitness, however, are difficult to obtain in large population-based epidemiological studies [26]. Concordance of findings from studies using self-reported physical activity measures with those that assessing physical activity using direct measures serve to attenuate some concerns about measurement error.

Results from observational epidemiologic studies [23–26] and from randomized trials [33, 34] have consistently demonstrated an inverse relationship between physical activity and MetS. The observed statistical association in our study and those reported by other investigators are biologically plausible. As hypothesized by several investigators, abdominal obesity and insulin resistance are believed to be the primary physiological mechanisms for development of MetS [35, 36]. Changes in life style have shown to reduce insulin resistance and obesity. Among modifications in lifestyle, an increase in physical activity plays an important role[36].

In conclusion, the prevalence of MetS observed in this study was high and engaging in LTPA was associated with decreased risk of MetS. Research has shown that MetS is associated with an increased risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease-related morbidity and mortality, resulting in an enormous economic burden to society [37]. Investigators in Latin America have called for a country-specific epidemiologic data to help bring public health policy changes for surveillance, prevention, and intervention [6]. The high prevalence of MetS reported in this study calls for clinical preventive services to identify and control the existing metabolic abnormalities among patients. Moreover, development and implementation of public health programs that promote physical activity and balanced diet are needed to help reduce the burden of disease.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an award from the National Institutes of Health, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (T37-MD001449)

References

- 1.WHO. Prevention Chronic Disease: A vital Investment. [Accessed October 15, 2008];Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Report. 2008 Available at: http://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/contents/part1.pdf.

- 2.Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould CL, Hofman KJ. The global burden of chronic diseases: overcoming impediments to prevention and control. JAMA. 2004;291:2616–2622. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalacorte RR, Reichert C, Vieira JL. Metabolic syndrome and physical activity in southern Brazilian community-dwelling elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1372–1373. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma G, Luan D, Li Y, Liu A, Hu X, Cui Z, et al. Physical activity level and its association with metabolic syndrome among an employed population in China. Obes Rev. 2008;9 Suppl 1:113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oguma Y, Shinoda-Tagawa T. Physical activity decreases cardiovascular disease risk in women: review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:407–418. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schargrodsky H, Hernandez-Hernandez R, Champagne BM, Silva H, Vinueza R, Silva Aycaguer LC, et al. CARMELA: assessment of cardiovascular risk in seven Latin American cities. Am J Med. 2008;121:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacoby E, Goldstein J, Lopez A, Nunez E, Lopez T. Social class, family, and life-style factors associated with overweight and obesity among adults in Peruvian cities. Prev Med. 2003;37:396–405. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galea S, Vlahov D. Urban health: evidence, challenges, and directions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:341–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medina-Lezama J, Zea-Diaz H, Morey-Vargas OL, Bolanos-Salazar JF, Munoz-Atahualpa E, Postigo-MacDowall M, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Peruvian Andean hispanics: the PREVENCION study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;78:270–281. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seclen S, Villena A, Larrad MT, Gamarra D, Herrera B, Perez CF, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in the mestizo population of Peru. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2006;4:1–6. doi: 10.1089/met.2006.4.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soto V, Vergara WE, Neciosup PE, Prevalencia Y. Factores De Riesgo De Síndrome Metabólico En Población Adulta Del Departamento De Lambayeque, Perú - 2004. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2005;22:254–261. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraser B. Peru's epidemiological transition. Lancet. 2006;367:2049–2050. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68906-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan American Health Organization(PAHO) [Accessed October 15, 2008];Countrywide Integrated Noncommunicable Diseases Intervention (CINDI) Programme. Available at: http://www.paho.org/english/ad/dpc/nc/hcncindi.pdf.

- 14.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, Haskell WL, Macera CA, Bouchard C, et al. Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402–407. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers J. Cardiology patient pages. Exercise and cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2003;107:e2–e5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048890.59383.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. 1996

- 17.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356–359. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiwaku K, Nogi A, Kitajima K, Anuurad E, Enkhmaa B, Yamasaki M, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome using the modified ATP III definitions for workers in Japan, Korea and Mongolia. J Occup Health. 2005;47:126–135. doi: 10.1539/joh.47.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lorenzo C, Serrano-Rios M, Martinez-Larrad MT, Gonzalez-Sanchez JL, Seclen S, Villena A, et al. Geographic variations of the International Diabetes Federation and the National Cholesterol Education Program-Adult Treatment Panel III definitions of the metabolic syndrome in nondiabetic subjects. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:685–691. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holme I, Tonstad S, Sogaard AJ, Larsen PG, Haheim LL. Leisure time physical activity in middle age predicts the metabolic syndrome in old age: results of a 28-year follow-up of men in the Oslo study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park YW, Zhu S, Palaniappan L, Heshka S, Carnethon MR, Heymsfield SB. The metabolic syndrome: prevalence and associated risk factor findings in the US population from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:427–436. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramirez-Vargas E, Arnaud-Vinas Mdel R, Delisle H. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and associated lifestyles in adult males from Oaxaca, Mexico. Salud publica de Mexico. 2007;49:94–102. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342007000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sofi F, Capalbo A, Marcucci R, Gori AM, Fedi S, Macchi C, et al. Leisure time but not occupational physical activity significantly affects cardiovascular risk factors in an adult population. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:947–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delavar MA, Sann ML, Syed Hassan STB, Lin KG, Hanachi P. Physical Activity and the Metabolic Syndrome in Middle Aged Women, Babol, Mazandaran province, Iran. Eur J Sci Res. 2008;22:411–421. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang X, Telama R, Hirvensalo M, Mattsson N, Viikari JS, Raitakari OT. The longitudinal effects of physical activity history on metabolic syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:1424–1431. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318172ced4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harpham T, Stephens C. Urbanization and health in developing countries. World Health Stat Q. 1991;44:62–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popkin BM. The nutrition transition in low-income countries: an emerging crisis. Nutr Rev. 1994;52:285–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1994.tb01460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strath SJ, Brage S, Ekelund U. Integration of physiological and accelerometer data to improve physical activity assessment. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:S563–S571. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185650.68232.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jurca R, Jackson AS, LaMonte MJ, Morrow JR, Jr, Blair SN, Wareham NJ, et al. Assessing cardiorespiratory fitness without performing exercise testing. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drexel H, Saely CH, Langer P, Loruenser G, Marte T, Risch L, et al. Metabolic and antiinflammatory benefits of eccentric endurance exercise - a pilot study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008;38:218–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.01937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slentz CA, Aiken LB, Houmard JA, Bales CW, Johnson JL, Tanner CJ. Inactivity, exercise, and visceral fat. STRRIDE: a randomized, controlled study of exercise intensity and amount. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1613–1618. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00124.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reaven GM. Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–1607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Churilla JR, Zoeller RF. Physical Activity and the Metabolic Syndrome: A Review of the Evidence Physical Activity. AJLM. 2008;2:118–125. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Forsen B, Lahti K, Nissen M, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:683–689. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]