Abstract

Background

While over 70% of younger women with nonmetastatic breast cancer (BC) receive adjuvant chemotherapy, only about 15–20% of elderly women with BC receive chemotherapy. The decision to treat may be associated with non-medical factors, such as patient, physician or practice characteristics. We evaluated the association between oncologist characteristics and the receipt of chemotherapy in elderly women with BC.

Methods

Women >65 years, diagnosed with stages I-III BC, between 1991–2002, were identified in the SEER-Medicare database. The Physician Unique Identification Number was linked to the American Medical Association Masterfile to obtain information on oncologists. We investigated the association of demographic, tumor, and oncologist-related factors with receipt of chemotherapy, using Generalized Estimating Equations to control for clustering. We defined patients as low-risk (estrogen/progesterone receptor positive, stage I/II) and high-risk (estrogen/progesterone receptor-negative, stage II/III).

Results

Of 42,544 women identified, 8,714 (20%) were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. In a hierarchical analysis, women who underwent chemotherapy were more likely be treated by oncologists primarily employed in a private-practice (OR=1.40;95%CI 1.23–1.59), and who graduated after 1975 (OR=1.12; 95%CI 1.01–1.26), and were less likely to have an oncologist trained in the US (OR=0.83;95%CI 0.74–0.93). The association between private-practice setting and receipt of chemotherapy was similar for patients at high-risk (OR=1.55) and low-risk (OR=1.35) for cancer recurrence.

Conclusions

Elderly women with BC treated by oncologists who were employed in a private practice were more likely to receive chemotherapy. Efforts to differentiate whether these associations reflect experience, practice setting, insurance type, or other economic incentives are warranted.

Introduction

One of the most important advances of medical oncology over the past 30 years has been the gradual refinement through large-scale randomized trials of the use of adjuvant systemic therapy for breast cancer. Professional guidelines dating back to the late 1990’s recommended that chemotherapy be considered for all women with invasive breast cancer, especially those with positive lymph nodes or estrogen receptor (ER) negative tumors.1–3 These guidelines for chemotherapy use are related to the risk of recurrence. Assessment of risk has traditionally been based on the patient’s menopausal status, tumor stage, and tumor characteristics. The use of chemotherapy for small, hormone receptor-positive cancers is less clear-cut, and involves choice by the patient and physician and shared decision making.

The elderly are generally under-represented in clinical trials. Because of the uncertain benefit of chemotherapy, elderly women are less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy compared to younger women.4–8 Studies that used the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology and End-Results (SEER)-Medicare database have demonstrated an improvement in survival for some women over the age of 65 years with early stage breast cancer who were treated with chemotherapy.7–9 While there were slight differences, overall the studies found an approximate 25% survival benefit for women with lymph-node positive, hormone receptor negative cancers, after controlling for multiple confounding variables. The use of chemotherapy decreased with increasing age, black race and increased comorbidity, and use increased with year of diagnosis, tumor size, number of positive lymph nodes and higher tumor grade. No benefits were observed for patients with lymph-node negative disease or for patients with hormone receptor positive cancers.7, 8 Since it is also now known that elderly patients treated on cooperative group clinical trials experience similar reductions in breast cancer mortality and recurrence as younger patients, the identification of modifiable factors that influence the undertreatment of high-risk and overtreatment of low-risk elderly women is necessary.10

Research on the determinants of receipt of cancer treatment has mostly focused on patient-related factors, such as race/ethnicity, geographic location, age, and socioeconomic status. Relatively less research has evaluated the role of the physician and practice setting in the receipt of cancer care. In this study, we used the SEER-Medicare database to investigate the association of oncologist characteristics, such as gender, type of degree, year of graduation and practice setting (private vs non-private), with receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy for elderly patients with early stage breast cancer. We determined patterns of use both in patients at high-risk and those at low-risk for a breast cancer recurrence.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Database

We utilized the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End-Results (SEER)-Medicare linked database, which was co-developed by the U.S. National Cancer Institute and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The SEER Program represented roughly 14% of the United States population in 1991, and since 2000 represents approximately 26%. Medicare covers hospital services, physician services, some drug therapy, and other medical services for more than 97% of persons aged >65 years. The linked SEER-Medicare database contains clinical, demographic, and medical claims data on patients >65 years of age and is a unique population-based resource for longitudinal epidemiologic and health outcomes studies. Its characteristics and validation have been comprehensively reported elsewhere 11, 12

To obtain information on the characteristics of the SEER-Medicare patients’ physicians, we used the Unique Physician Identification Number (UPIN) to link the Medicare claims with the American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile, as described elsewhere.13 This file contains data collected from physician members of the AMA, including gender, age, medical degree (MD or DO), location of medical school (US vs foreign), year of graduation, employment setting (private vs non-private), and specialty.13 Physicians records are continuously updated and verified by the AMA.14

Patient Selection

We initially identified all female Medicare participants aged >65 years who were diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer from January 1, 1991 through December 31, 2002 who had either a lumpectomy or mastectomy within 90 days of diagnosis (61,867). We then selected patients who underwent consultation with an oncologist within I year following diagnosis (n=42,544). We used Medicare claims to identify patients who had initiated chemotherapy within 6 months following surgery. Women who were not members of a health maintenance organization (HMO) and had Medicare Parts A and B during the 12 months prior to their diagnosis and until death/censoring, and women who had a prior breast cancer or other cancer, end-stage renal disease, or a breast cancer diagnosis without histologic confirmation were excluded.

A subset of the patients were categorized according to the NCCN guidelines. Patients were classified as having a high risk of recurrence if they had tumors that were estrogen and progesterone receptor negative and had stage II or III cancer (n=2,947). Low recurrence risk patients were defined as hormone receptor positive and stage I or II (28,859).

Oncologist Characteristics

Oncologist characteristics that were analyzed, based on the variables in the AMA Masterfile included gender, year of graduation (<1975 or ≥1975; about 50% cutpoint), primary employment setting (private vs. other), location of training (United States vs. other), and type of degree (Medical Doctor [MD] or Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine [DO]). Private primary employment setting was defined as self employed solo, two-physician, or group practice (011, 013, 021, 030). Other employment settings included medical school, non-government hospital, governmental hospital or VA. In our sample, only 6% had missing data for this category. Physician age was categorized by decade of birth. Physicians’ patient volumes (i.e., total number of claims for breast cancer patients in the database 1992–2002) were dichotomized, as 1–40 vs >40 patients. We defined high patient volume as an oncologist who consulted on >40 patients in the sample. We chose this cutoff because it represented the top 10% of the oncologists with regard to numbers of patients from this cohort who underwent chemotherapy treatment based on the distribution of consultations.

Measurement of Treatments and Outcomes

We identified and categorized patients with respect to the chemotherapy they received using the SEER-Medicare linked databases and ICD-9-CM procedure, CPT-4, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS), and ICD-9-CM V codes. These codes have been found to capture virtually all breast cancer cases.15

We categorized patients as having had chemotherapy exposure in the Medicare files using codes for ICD-9-CM diagnosis, ICD-9-CM procedural, Current Procedural Terminology, HCPCS, and revenue center codes. We included codes 'v581', 'v662', 'v 672', 'E9331', 'E9307', '9925', 'Q0083', 'Q0084', 'Q0085' CPT codes for administration of chemo '96400' thru '96499' & '96500' thru '96599' 'J9000' thru 'J9999'; DRG CODE='410' and Revenue Center Codes ='0331','0332','0335'.

Socioeconomic status of patients

We generated an aggregate SES score from education, poverty and income data from the 2000 census track data, following the method adapted by Du et al.16 Patients were ranked on a 1–5 scale, where 1 was the lowest value, based on a formula incorporating these variables weighted equally. The 394 patients with missing data were assigned to the lowest SES category. The results did not change if they were assigned a separate category. In the final analysis, the first and second rankings were combined.

Comorbid disease

To assess the prevalence of comorbid disease in our cohort, we used the Klabunde adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity index.17, 18 Medicare inpatient and outpatient claims were searched for ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes. Each condition was weighted, and patients were assigned a score based on the Klabunde-Charlson index 18

Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test was used to compare oncologist-related, demographic, and clinical characteristics between patients who received chemotherapy and those who did not and between patients who consulted with an oncologist in private practice vs those who consulted with an oncologist in another practice setting. Univariate odds ratios were calculated individually for each variable. All hypothesis tests were two-sided.

The Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) methodology was introduced by Zeger and Liang 19 to deal with clustering in data that otherwise would be analyzed by means of a generalized linear model, and GEEs (PROC GENMOD in SAS) have become an important strategy in the analysis of correlated data 19, 20. We used GEEs to account for the correlations of outcome measures among patients who had the same physician. The unit of analysis was the patient. For each patient, the physician’s unique UPIN number was used as the clustering variable. The model assumptions were: the data had a binomial distribution, the link function was logit, and the type of variance was exchangeable.

We evaluated the odds of chemotherapy for all the categories of each variable, controlling for all the other variables in the model. The model included: 1) oncologist characteristics (gender, type of degree, country of training, practice type, patient volume); 2) patient demographic variables (age, race, place of residence, marital status, SES); and 3) clinical variables (tumor grade, AJCC stage, hormone receptor status, comorbidity score). We also performed separate analyses for the high-risk and low-risk of recurrence groups. All statistical analyses were conducted using the SAS system for Windows, Version 9.13.

Results

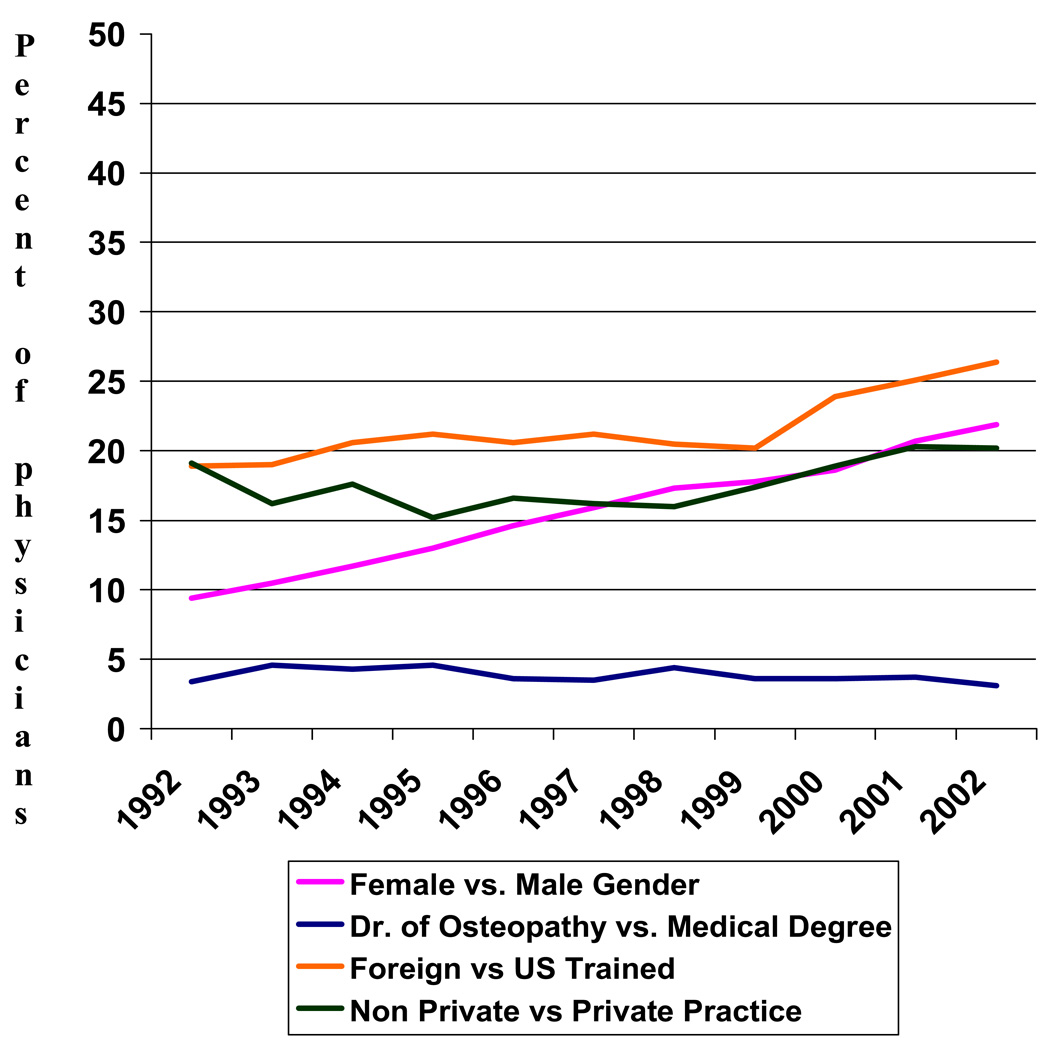

We identified 42,544 women in SEER-Medicare who were diagnosed with stages I-IIII breast cancer during the study period and who met our eligibility criteria. A total of 2,833 oncologists consulted on these patients. We defined 28,859 patients as low-risk for recurrence, of whom 4,366 (15%) received chemotherapy, while 2,947 patients were defined as high-risk, of whom 1,791 (61%) received chemotherapy. Overall, 20% of women in the cohort received chemotherapy, with chemotherapy use increasing from 8% to 34% between 1992 and 2002. The oncologists who administered chemotherapy on these patients were predominantly male (80%), in private practice (72%), trained in the US (72%), and holders of a medical degree (MD) (97%) as opposed to an osteopathic degree (DO). Only the number of female oncologists and the number of oncologists who graduated after 1975 increased over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Change in Oncologist Characteristics between 1992 and 2002

Table 2 reports the odds of receipt of chemotherapy across individual demographic and clinical characteristics of the patient and the characteristics of the oncologists. Patients consulting with an oncologist who had primary employment in private vs non-private practice, who was foreign trained as opposed to US trained, or who graduated after 1975 as opposed to before, were more likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncologists in private practice were more likely to be male, have a larger patient panel, and have graduated prior to 1975 (Table 1).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between receipt of chemotherapy among elderly patients With early stage breast cancer, and the characteristics of their oncologists, and their own demographic and clinical characteristics* (N=42,544)

| Characteristics | N | % | Unadjusted Odds Ratios (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratios (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received chemotherapy | 8714 | 20.0 | ||

| a. Oncologist characteristics | ||||

| Degree | ||||

| DO | 324 | 20.2 | Reference | Reference |

| MD | 8390 | 20.4 | 1.01(0.90–1.15) | 0.87 (0.65–1.16) |

| US-trained | ||||

| No | 2112 | 22.1 | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 6602 | 20.0 | 0.88 (0.83–0.93)* | 0.83 (0.74–0.93)* |

| Date of graduation | ||||

| <1975 | 3722 | 18.9 | Reference | Reference |

| ≥1975 | 4992 | 21.9 | 1.20 (1.15–1.26)* | 1.12 (1.01–1.26)* |

| Type of practice | ||||

| Non-private | 1356 | 17.4 | Reference | Reference |

| Private | 7358 | 21.2 | 1.27 (1.19–1.36)* | 1.40 (1.23–1.60)* |

| # Patients in cohort | ||||

| 1–40 | 4681 | 21.3 | Reference | Reference |

| >40 | 4033 | 19.6 | 0.90 (0.86–0.94)* | 1.07 (0.93–1.23) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 7205 | 20.4 | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 1509 | 20.8 | 1.03 (0.96–1.09) | 0.99 (0.87–1.14) |

| b. Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||

| 65–69 | 3261 | 34.4 | Reference | Reference |

| 70–74 | 3052 | 24.2 | 0.61 (0.58–0.65)* | 0.53 (0.49–0.57)* |

| 75–79 | 1762 | 16.2 | 0.37 (0.34–0.39)* | 0.27 (0.25–0.30)* |

| 80+ | 639 | 6.7 | 0.14 (0.12–0.15)* | 0.07 (0.06–0.08)* |

| Race | ||||

| White | 7693 | 20.1 | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 563 | 24.9 | 1.32 (1.19–1.45)* | 0.99 (0.86–1.15) |

| Hispanic | 109 | 22.1 | 1.13 (0.91–1.39) | 0.90 (0.69–1.18) |

| Other | 349 | 22.1 | 1.13 (0.99–1.27) | 1.01 (0.86–1.18) |

| Residence | ||||

| Non-metropolitan | 811 | 20.3 | Reference | Reference |

| Metropolitan | 7903 | 20.5 | 0.99 (0.91–1.07) | 0.93 (0.82–1.06) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Unmarried | 3903 | 17.8 | Reference | Reference |

| Married | 4580 | 23.7 | 1.43 (1.36–1.50)* | 1.17 (1.10–1.24)* |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Lowest quartile | 2594 | 20.0 | Reference | Reference |

| 2nd quartile | 2120 | 20.4 | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | 1.02 (0.93–1.12) |

| 3rd quartile | 1877 | 20.8 | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) |

| 4th quartile | 2062 | 21.1 | 1.07 (1.01–1.16)* | 1.11 (1.01–1.22)* |

| c. Patient clinical characteristics | ||||

| Stage | ||||

| I | 1566 | 6.9 | Reference | Reference |

| II | 5899 | 34.2 | 6.96 (6.55–7.39)* | 8.43 (7.72–9.09)* |

| III | 1249 | 46.3 | 11.57 (10.6–12.7)* | 17.68 (15.19–19.74)* |

| Hormone receptor status | ||||

| Er+ and/or PR+ | 5089 | 16.6 | Reference | Reference |

| Er− and PR− | 2384 | 47.9 | 4.54 (4.26–4.83)* | 4.52 (4.13–4.93)* |

| Grade | ||||

| Well/moderately differentiated | 3615 | 15 | Reference | Reference |

| Poorly differentiated | 4112 | 33.4 | 2.83 (2.69–2.99)* | 1.78 (1.67–1.90)* |

| Unknown | 987 | 15.8 | 1.06 (0.98–1.15) | 1.05 (0.94–1.16) |

| Comorbidity score | ||||

| 0 | 5627 | 21.8 | Reference | Reference |

| 1 | 2134 | 19.9 | 0.88 (0.84–0.94)* | 0.89 (0.83–0.95)* |

| >1 | 953 | 15.8 | 0.67 (0.62–0.72)* | 0.60 (0.55–0.66)* |

P-value <0.001

DO=Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine; ER=estrogen receptor; PR=progesterone receptor.

Odds Ratios based on univariate logistic regression.

Table 1.

Characteristics of oncologists in the cohort treating women for early stage breast cancer in private practice 1992–2002 (N=2,833)

| Private | Non-Private | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oncologist Chracteristics | N | % | N | % | N | % | P value* | |

| 2036 | 72 | 797 | 28 | 2833 | ||||

| Degree | ||||||||

| MD | 1989 | 72 | 775 | 28 | 2764 | 97.5 | 0.48 | |

| DO | 47 | 68 | 22 | 32 | 69 | 2.5 | ||

| US-trained | ||||||||

| No | 559 | 70 | 240 | 30 | 799 | 28.2 | 0.16 | |

| Yes | 1477 | 73 | 557 | 27 | 2034 | 71.8 | ||

| Year of graduation | ||||||||

| <1975 | 100 | 78 | 310 | 22 | 1410 | 50.0 | <.0001 | |

| ≥1975 | 936 | 66 | 487 | 34 | 1423 | 50.0 | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 1677 | 74 | 603 | 26 | 2280 | 80.5 | <.0001 | |

| Female | 359 | 65 | 194 | 35 | 553 | 19.5 | ||

| # of patients in the cohort | ||||||||

| 1–40 | 1791 | 70 | 753 | 30 | 2544 | 89.8 | <.0001 | |

| >40 | 245 | 85 | 44 | 15 | 289 | 10.2 | ||

P value based on chi-square statistical test

MD=Medical Degree

DO=Doctor of Osteopathy

Controlling for known demographic and clinical confounders, lower likelihood of receiving chemotherapy was observed among patients with a US vs non-US trained oncologist (OR=0.83, 95%CI 0.74–0.93, p=0.001), but greater likelihood of receiving chemotherapy with an oncologist in private vs non-private practice (OR=1.40, 95% CI 1.23–1.60, p<0.0001) (Table 2). Receipt of chemotherapy was also associated with younger age at diagnosis, higher SES, less favorable tumor characteristics, more recent year of diagnosis, fewer comorbid conditions, and being married.

To evaluate patterns of care in patients at low-risk and high-risk for cancer recurrence, we conducted separate GEE analyses of the association between oncologist practice and receipt of chemotherapy, among patients stratified into two groups by risk of recurrence (High Risk and Low Risk) (Table 3). The association between primary practice type and use of chemotherapy was similar for patients with high risk (OR=1.55) and those with low risk (OR-1.35) for cancer recurrence

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of associations between receipt of chemotherapy and demographic, tumor, and oncologist characteristics among elderly patients who had high-risk and low-risk breast cancer (n=37,806)

| HIGH RECURRENCE RISK | LOW RECURRENCE RISK | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

| a. Surgeon characteristics | |||||

| Degree | |||||

| DO | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| MD | 1.19 | 0.73–1.94 | 0.77 | 0.54–1.10 | |

| US-trained | |||||

| No | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Yes | 0.85 | 0.68–1.07 | 0.74* | 0.65–0.86 | |

| Type of practice | |||||

| Non-private | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Private | 1.55* | 1.22–1.98 | 1.35* | 1.16–1.56 | |

| #patients in practice | |||||

| 1–40 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| >40 | 0.93 | 0.76–1.13 | 1.03 | 0.73–0.98 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Female | 1.12 | 0.87–1.42 | 0.97 | 0.83–1.14 | |

| Year of graduation | |||||

| <1975 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| ≥1975 | 1.25* | 1.02–1.52 | 1.42* | 1.25–1.62 | |

| b. Patient demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age at diagnosis | |||||

| 65–69 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| 70–74 | 0.62* | 0.49–0.77 | 0.52* | 0.47–0.56 | |

| 75–79 | 0.36* | 0.27–0.45 | 0.28* | 0.25–0.32 | |

| 80+ | 0.11* | 0.08–0.14 | 0.07* | 0.06–0.09 | |

| Race | |||||

| White | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Black | 0.99 | 0.73–1.33 | 1.12 | 0.92–1.37 | |

| Hispanic | 1.39 | 0.53–1.82 | 1.01 | 0.70–1.47 | |

| Residence | |||||

| Metropolitan | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Non-metropolitan | 1.26 | 0.92–1.73 | 0.99 | 0.84–1.18 | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Unmarried | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Married | 0.10* | 0.94–1.31 | 1.20 | 1.11–1.30 | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||

| Lowest quartile | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| 2nd quartile | 1.26* | 1.02–1.55 | 1.16* | 1.03–1.31 | |

| 3rd quartile | 1.22 | 0.98–1.54 | 1.24* | 1.11–1.40 | |

| Highest quartile | 1.37* | 1.06–1.75 | 1.32* | 1.17–1.49 | |

| c. Patient clinical characteristics | |||||

| Stage | |||||

| I | - | - | 1.00 | Referent | |

| II | 1.00 | Referent | 10.03* | 9.03–11.14 | |

| III | 1.85* | 1.46–2.34 | - | - | |

| Grade | |||||

| Well/moderately differentiated | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| Poorly differentiated | 1.36* | 1.12–1.66 | 1.59* | 1.46–1.73 | |

| Unknown | 0.83 | 0.61–1.14 | 0.80* | 0.71–0.90 | |

| Comorbidity score | |||||

| 0 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | |

| 1 | 0.79* | 0.66–0.96 | 0.97 | 0.89–1.06 | |

| >1 | 0.58* | 0.47–0.73 | 0.67* | 0.59–0.76 | |

P-Value <0.01

Each variable was corrected for the other listed characteristics and year of diagnosis.

DO=Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine; ER=estrogen receptor; PR=progesterone receptor.

Low Risk: ER/PR Pos; Stage I-II - N=28859

High Risk ER/PR Neg; Stage II-III – 2947

Discussion

In this population-based study of elderly women with early stage breast cancer, we found that the number of elderly women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy increased from 8% to 34% between 1992 and 2002, with 61% of high-risk patients and 15% of low-risk patients undergoing chemotherapy. We have now shown that patients treated by physicians who have their primary employment in a private practice are more likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy for early stage breast cancer. This relationship holds both for patients with high and low risks of cancer recurrence. In addition, we confirmed that, after controlling for physician characteristics, the clinical and demographic characteristics known to influence treatment also influenced adjuvant chemotherapy use in our model.

Research on the determinants of receipt of cancer treatment has mostly focused on patient factors, such as race/ethnicity, geographic location, age, and socioeconomic status. In our study we also found that younger age, being married, and high socioeconomic status were all associated with greater likelihood to receive chemotherapy. While we found that black women were more likely to receive chemotherapy in the unadjusted analysis, the association disappeared in the adjusted analysis. This is consistent with other studies in this patient population.7 On the other hand, relatively little research has evaluated the role of oncologist characteristics in cancer treatment decisions. Investigators have reported the composite influence of the physician’s characteristics on the receipt of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer,21 radiation after breast conservation surgery22 as well as on referral to an oncologist after a diagnosis of colon 23 or lung cancer.24 It is increasingly apparent that patients with similar demographic and clinical characteristics may be treated differently depending on the physician they consult. 25, 26 No prior studies have investigated the influence of physician and practice setting.

We were surprised to see the strong and consistent relationship between practice setting and chemotherapy use independent of physician characteristics, and were even more surprised to see that this association was similar both for patients with a clear indication due to high recurrence risk, as well as for those who were likely to have only minimal benefit. What might explain this association? One possibility may relate to patient volume, since the oncologists in private practice generally had a higher patient volume, which may then translate into a greater comfort level treating elderly patients. However, the association between panel size and chemotherapy use was weak, and did not modify the association with practice setting. Another possibility is that it is related to patient selection factors. Patients may choose to see physicians for chemotherapy in private settings due to convenience, and patients with more complicated medical conditions may be treated at university hospitals and clinics where they are less likely to receive chemotherapy; therefore, these results may be a product of selection bias. However, many of these biases are controlled for in the multivariate analysis. Another possibility is that it is related to patients’ insurance status. Patients seen in a private practice setting are, in general, more likely to have private insurance and to be of higher SES. While all of the patients in this cohort had Medicare coverage and were not covered under an HMO, physician practice patterns may be influenced by the type of patients in the overall practice. Research has shown that payment mechanisms influence physicians’ clinical decision making, 27 that physicians are more likely to recommend services for insured than for uninsured patients.28, and that salaried vs. fee-for-service reimbursement influences physician behavior.29. In a survey of medical oncologists, the majority of physicians reported that out-of-pocket costs could influence chemotherapy decisions; however, only 30% reported that costs had actually influenced their treatment decisions.30 In another survey, only 16% of oncologists acknowledged omitting treatment options on the basis of their perceptions of a patient’s ability to afford treatment.31

A less honorable possibility is that recommendations for chemotherapy are influenced by financial reimbursement and personal compensation that ensues from chemotherapy administration. An issue that has plagued oncology is the conflict-of-interest that ensues from the administration of chemotherapy drugs. Many practices buy chemotherapy drugs at discounted prices, and then administer these drugs in the office. Profit is generated from the difference between what is paid for the drug and what is charged to insurers and government programs. Some estimates indicate that oncologists in private practice make the bulk of their practice revenue from chemotherapy concessions.32 While the majority of oncologists are motivated by patient desires, the potential for conflict of interest in the system has raised concerns, and has resulted in proposals to regulate the reimbursement system.32

Patients also play a large role in the ultimate decision to undergo treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy. Acceptance of adjuvant chemotherapy by a woman with breast cancer occurs often after an assessment of risk and benefit, a process referred to as “shared decision making”. While there are some patients with a low recurrence risk who are willing to accept a a very small benefit despite the risk of treatment related complications, there are others who clearly benefit due to the higher risk of recurrence and NCCN guidelines recommend chemotherapy. A recent study found that only 45% of 4,395 women with early-stage breast cancer received treatment consistent with NCCN guidelines. The authors concluded that the reasons for low adherence to guidelines were multifactorial and included insufficient health system supports to clinicians, inadequate organization and delivery systems, and ineffective continuing medical education.33 Similarly, a recent study of 275 women with early-stage breast cancer found that 16% of patients who should have received adjuvant chemotherapy did not.34 Studies have shown that chemotherapy use in the elderly decreases with increasing age, number of comorbid conditions, and favorable tumor characteristics.5

Our study has some weaknesses. The SEER-Medicare dataset that we used for these analyses does not include data on a number of variables that might have also been associated with receipt of adjuvant chemotherapy, such as psychological outlook, communication with the physician, or health behaviors and specific contraindications, such as performance status. However given the very large size of our sample, these unmeasured variables are often correlated with the variables used in the analysis, and are unlikely to have a significant influence on the point estimates. It is also possible that there was some misclassification of the private practice variable. In addition, incomplete billing in medical centers or government hospitals could also result in biased results.

Our study demonstrates a small but independent association between both oncologist primary practice setting and location of medical training, and the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with localized breast cancer, regardless of the risk for BC recurrence. This study adds significantly to the limited investigation of the influence of practice setting and physician characteristics on treatment. To improve the quality of cancer care, efforts to differentiate whether these associations reflect experience, education, practice setting, insurance type, or other economic incentives are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hershman is the recipient of an ASCO Advanced Clinical Research Award. Drs. Herhsman and Neugut are the recipients of grants from the American Cancer Society (RSGT-08-009-01-CPHPS and RSGT-01-02404-CPHPS). Mr. McBride is the recipient of a R25 fellowship from NCI (CA09461).

This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The analysis, interpretation, reporting of the data, writing of the manuscript, and decision to publish, were the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Branch, Division of Cancer Prevention and Population Science, NCI; the Office of Information Services, and the Office of Strategic Planning, HCFA; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

References

- 1.NIH consensus conference. Treatment of early-stage breast cancer. Jama. 1991;265(3):391–395. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=1984541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson RW, Goldstein LJ, Gradishar WJ, Lichter AS, McCormick B, Moe RE, et al. NCCN Breast Cancer Practice Guidelines. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Oncology (Williston Park) 1996;10(11 Suppl):47–75. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=8953596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Consensus conference. Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Jama. 1985;254(24):3461–3463. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=4068189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15894097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du XL, Key CR, Osborne C, Mahnken JD, Goodwin JS. Discrepancy between consensus recommendations and actual community use of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(2):90–97. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-2-200301210-00009. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12529090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodard S, Nadella PC, Kotur L, Wilson J, Burak WE, Shapiro CL. Older women with breast carcinoma are less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy: evidence of possible age bias? Cancer. 2003;98(6):1141–1149. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11640. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12973837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elkin EB, Hurria A, Mitra N, Schrag D, Panageas KS. Adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in older women with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer: assessing outcome in a population-based, observational cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2757–2764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6053. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16782916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giordano SH, Duan Z, Kuo YF, Hortobagyi GN, Goodwin JS. Use and outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2750–2756. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3028. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16782915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du XL, Jones DV, Zhang D. Effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive operable breast cancer in older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(9):1137–1144. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.9.1137. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16183952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muss HB, Woolf S, Berry D, Cirrincione C, Weiss RB, Budman D, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in older and younger women with lymph node-positive breast cancer. Jama. 2005;293(9):1073–1081. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.9.1073. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15741529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren JL, Harlan LC, Fahey A, Virnig BA, Freeman JL, Klabunde CN, et al. Utility of the SEER-Medicare data to identify chemotherapy use. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl) doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020944.17670.D7. IV-55–61. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12187169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, Bach PB, Riley GF. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl) doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. IV-3–18. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12187163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldwin LM, Adamache W, Klabunde CN, Kenward K, Dahlman C, J LW. Linking physician characteristics and medicare claims data: issues in data availability, quality, and measurement. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl) doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00012. IV-82–95. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12187173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.AMA Physician Masterfile. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du XL, Osborne C, Goodwin JS. Population-based assessment of hospitalizations for toxicity from chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(24):4636–4642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.088. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12488407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du XL, Fang S, Vernon SW, El-Serag H, Shih YT, Davila J, et al. Racial disparities and socioeconomic status in association with survival in a large population-based cohort of elderly patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2007;110(3):660–669. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22826. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17582625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson ME, Sax FL, MacKenzie CR, Fields SD, Braham RL, Douglas RG., Jr Assessing illness severity: does clinical judgment work? J Chronic Dis. 1986;39(6):439–452. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90111-6. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=3086355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=11146273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(4):1049–1060. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=3233245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panageas KS, Schrag D, Russell Localio A, Venkatraman ES, Begg CB. Properties of analysis methods that account for clustering in volume-outcome studies when the primary predictor is cluster size. Stat Med. 2006;26(9):2017–2035. doi: 10.1002/sim.2657. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17016864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shahinian VB, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Determinants of androgen deprivation therapy use for prostate cancer: role of the urologist. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(12):839–845. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj230. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16788157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hershman DL, Buono D, McBride RB, Tsai WY, Joseph KA, Grann VR, et al. Surgeon characteristics and receipt of adjuvant radiotherapy in women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(3):199–206. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm320. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18230795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo R, Giordano SH, Zhang DD, Freeman J, Goodwin JS. The role of the surgeon in whether patients with lymph node-positive colon cancer see a medical oncologist. Cancer. 2007;109(5):975–982. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22462. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17265530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Earle CC, Neumann PJ, Gelber RD, Weinstein MC, Weeks JC. Impact of referral patterns on the use of chemotherapy for lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(7):1786–1792. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.142. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=11919235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franks P, Williams GC, Zwanziger J, Mooney C, Sorbero M. Why do physicians vary so widely in their referral rates? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(3):163–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.04079.x. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=10718896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freiman MP. The rate of adoption of new procedures among physicians. The impact of specialty and practice characteristics. Med Care. 1985;23(8):939–945. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198508000-00001. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=4021579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen J, Andersen R, Brook R, Kominski G, Albert PS, Wenger N. The effects of payment method on clinical decision-making: physician responses to clinical scenarios. Med Care. 2004;42(3):297–302. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114918.50088.1c. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15076830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mort EA, Edwards JN, Emmons DW, Convery K, Blumenthal D. Physician response to patient insurance status in ambulatory care clinical decision-making. Implications for quality of care. Med Care. 1996;34(8):783–797. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199608000-00006. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=8709660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hickson GB, Altemeier WA, Perrin JM. Physician reimbursement by salary or fee-for-service: effect on physician practice behavior in a randomized prospective study. Pediatrics. 1987;80(3):344–350. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=3627885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nadler E, Eckert B, Neumann PJ. Do oncologists believe new cancer drugs offer good value? Oncologist. 2006;11(2):90–95. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-2-90. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16476830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schrag D, Hanger M. Medical oncologists' views on communicating with patients about chemotherapy costs: a pilot survey. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(2):233–237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2437. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17210946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abelson R. Drug Sales Bring Huge Profits, and Scrutiny, to Cancer Doctors New York Times New York. 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bloom BS, de Pouvourville N, Chhatre S, Jayadevappa R, Weinberg D. Breast cancer treatment in clinical practice compared to best evidence and practice guidelines. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(1):26–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601439. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=14710201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bickell NA, McEvoy MD. Physicians' reasons for failing to deliver effective breast cancer care: a framework for underuse. Med Care. 2003;41(3):442–446. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000052978.49993.27. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12618647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]