Abstract

Some chemosensory proteins (CSPs) are expressed in insect sensory appendages and are thought to be involved in chemical signaling by ants. We identified fourteen unique CSP sequences in EST libraries of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. One member of this group (Si-CSP1) is highly expressed in worker antennae, suggesting an olfactory function. A shotgun proteomic analysis of antennal proteins confirms the high level of Si-CSP1 expression, and also shows expression of another CSP and two odorant-binding proteins (OBPs). We cloned and expressed the coding sequence for Si-CSP1. We used cyclodextrins as solubilizers to investigate ligand binding. Fire ant cuticular lipids strongly inhibit Si-CSP1 binding to the fluorescent dye N-phenyl-naphthylamine, suggesting cuticular substances are ligands for Si-CSP1. Analysis of the cuticular lipids shows that the endogenous ligands of Si-CSP1 are not cuticular hydrocarbons.

Keywords: chemosensory proteins, Solenopsis invicta, proteomics, cuticular lipids, cyclodextrin

Introduction

Social insects restrict the benefits of altrusim to their kin by using nestmate recognition signals. The recognition system involves production, detection, and interpretation of chemical signals on the surface of the cuticle (Vander Meer & Morel, 1998). Often the nestmate recognition signals consist of cuticular hydrocarbons (Howard & Blomquist, 2005). In the carpenter ant, Campanotus japonicus, specialized antennal sensilla capture cuticular hydrocarbons by means of a hydrophobic ligand-binding protein known as a chemosensory protein (CSP), which transports them to the olfactory receptor neurons (Ozaki et al., 2005). Insects express CSP paralogs in a variety of tissues (Wanner et al., 2004; Pelosi et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2006; Forêt et al., 2007). The hydrocarbon-binding CSP of C. japonicus is expressed at high levels in the antenna, and it is the only CSP detected there. Antennal CSPs with similar sequences have been reported in several ant, wasp and bee species (Ishida et al., 2002; Briand et al., 2002; Cavello et al., 2003; Cavello et al., 2005; Forêt et al., 2007; Leal & Ishida, 2008). Nestmate recognition signals consisting of cuticular hydrocarbons have been found in many species of ant (Thomas et al., 1999; Lahav et al., 1999; Wagner et al., 2000). However, non-hydrocarbon cuticular lipids (e.g. fatty alcohols, fatty acids, wax esters) are often present in the extracts used for behavioral studies, but their roles in recognition are rarely studied (Vander Meer & Morel, 1998; Howard & Blomquist, 2005; Hefetz, 2007). It is not known how widespread is the use of cuticular hydrocarbons as nestmate recognition signals by social insects, nor is it known whether the major antennal CSP is the exclusive carrier of nestmate recognition signals to the olfactory receptor neurons. We have now identified Si-CSP1 as the major antennal CSP of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. We report here on the ligand-binding properties of recombinantly expressed Si-CSP1, using fluorescence spectroscopy as well as the ligand capture method we previously developed (Renthal, 2003).

Results and discussion

Fire ant chemosensory proteins

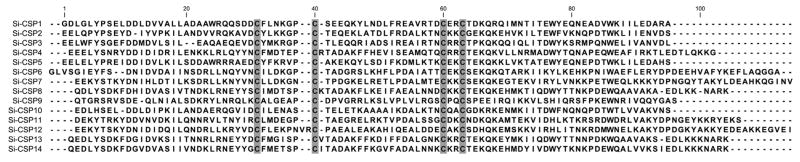

We used a pattern search of a preliminary version of the Lausanne Fire Ant EST library, which revealed 11 chemosensory protein (CSP) sequences. Subsequently, we identified three additional sequences using BLAST. The 14 CSP sequences are shown in Fig. 1, and they are also listed in Table 1 with the Genbank accession numbers. We also found additional sequences that differ at a small number of positions from the sequences in Fig. 1, but it is not yet clear whether the variation is due to sequencing errors, polymorphism or to functionally different CSPs. We constructed three dimensional models of the S. invicta CSPs, using the Swiss-Model Server (Guex and Peitsch, 1997; Schwede et al., 2002) with amino acid sequence homology to the liganded and unliganded forms of CSPMbraA6 from Mamestra brassicae (Campanacci et al., 2003; Protein Data Bank files 1n8u and 1kx8). The liganded models are all hollow cylinders, with the interior cavities in most models open at both ends and spanning the entire length of the molecule. The volume and shape of the cavities differ for each CSP, suggesting that some of the CSPs are selective for specific ligand molecules.

Figure 1.

Alignment of CSPs from S. invicta. Sequences were aligned by CLC Sequence Viewer 4. Conserved cysteines are shaded. The N-terminal amino acid for Si-CSP1 was determined by Edman degradation. Most other N-termini were predicted from signal sequence cleavage sites (not shown) using SignalP 3.0 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). The EST for Si-CSP7 lacks a full signal peptide, and its N-terminus was predicted by similarity with Si-CSP12. The EST for Si-CSP11 is a fragment that lacks both the N-terminus and C-terminus of the protein; the full sequence shown was obtained by PCR.

Table 1. Sequences coding for CSPs in Fire Ant EST Libraries.

For many of the CSPs, the same or similar sequences appear in several ESTs. Only one example is given for each. Numbers 1–14 were assigned arbitrarily.

| Name | Accession # | EST name |

|---|---|---|

| Si-CSP1 | EE134548 | SiJWH08ACX |

| Si-CSP2 | EE145825 | SiJWB07CAO2 |

| Si-CSP3 | EE145392 | SiJWE02CAI2 |

| Si-CSP4 | EE137035 | SiJWH09BBE |

| Si-CSP5 | EE141402 | SiJWD02BDQC |

| Si-CSP6 | EE130243 | SiJWH07ABA |

| Si-CSP7 | EH413134 | 13B10 |

| Si-CSP8 | EE138976 | SiJWF11BCE |

| Si-CSP9 | EE129471 | SiJWB03ACR |

| Si-CSP10 | EE142271 | SiJWG02BBO2 |

| Si-CSP11 | FJ748890 | SiJWE02AAV |

| Si-CSP12 | EE148685 | SiJWG08ABE |

| Si-CSP13 | EE132485 | SiJWA03ABI |

| Si-CSP14 | EE141365 | SiJWE03BDJ |

The fourteen chemosensory protein (CSP) sequences we identified in S. invicta EST libraries (Table 1 and Fig. 1) compare with 20 reported in Locusta migratoria and Tribolium castaneum, 10 in Mamestra brassicae and Bombyx mori, 9 in Nasonia vitripennis, 7 in Anopheles gambiae, 6 in Apis mellifera, and 4 in Drosophila melanogaster (Pelosi et al., 2005; Forêt, 2007). Thus, S. invicta has more CSPs than are yet known for any other hymenopteran.

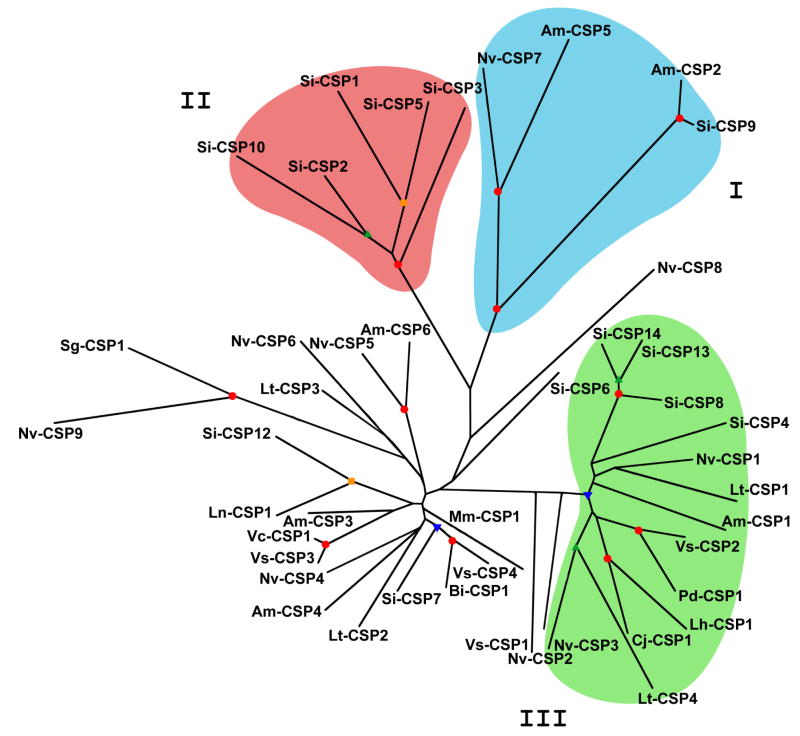

A neighbor-joining tree of hymenopteran CSPs (Fig. 2) shows three sequence groups supported by high bootstrap values. Group I is similar to a clade identified by Forêt et al. (2007) and characterized as “Divergent CSPs”, since these CSPs lack some of the sequences conserved across many orders. Group I CSPs, including Si-CSP9, may have a role in development, as this group includes Am-CSP5, which is expressed only in the egg (Forêt et al., 2007), and appears to function in development of the embryonic integument (Maleszka et al., 2007). Group II contains the fire ant CSPs that we identified in the antenna, Si-CSP1 and Si-CSP3 (Table 2) (discussed below), along with Si-CSP2, Si-CSP5 and Si-CSP10. Group II lacks known CSPs from any other species. A BLAST search of these sequences against all insect DNA and EST sequences also showed no other closely related CSPs. The complete A. mellifera genome and several large wasp EST libraries were included in this search. Therefore, it appears likely that group II contains CSPs which are unique to ants, and perhaps unique to Myrmicine ants. Similar paralogous expansions of CSPs were previously observed in other large analyses of CSPs (Wanner et al., 2004; Pelosi et al., 2006; Forêt et al., 2007). Group III is similar to Hymenoptera Class 1 identified by Wanner et al. (2004). It includes the A. mellifera protein Am-CSP1, which is strongly expressed in the antenna, as well as in other tissues (Forêt et al., 2007), and also L. humile, C. japonicus and P. dominulus CSPs which are known to be expressed in the antenna (Ishida et al., 2002; Cavello et al., 2003; Ozaki et al., 2005). Four fire ant CSPs are in this clade: Si-CSP4, 8, 13 and 14. However, these proteins were not detected in the proteomic analysis of fire ant worker antennae (Table 2) (discussed below).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of hymenopteran CSPs. Neighbor-joining tree compares fire ant CSP sequences with other known hymenopteran CSPs. Si, Solenopsis invicta; Am, Apis mellifera; Bi, Bombus ignitus; Cj, Camponotus japonicus; Lh, Linepithema humile; Ln, Lasius niger; Lt, Lysiphlebus testaceipes; Mm, Microplitis mediator; Nv, Nasonia vitripennis; Pd, Polistes dominulus; Sg, Scleroderma guani; Vc, Vespa crabro; Vs, Vespula squamosa. Background shading highlights three proposed groups of hymenopteran CSPs. Colored markers at branches indicate bootstrap values: red = 90–100%, yellow = 80–89%, green = 70–79%, blue=60–69%.

Table 2. Proteins identified in capillary LC/MS/MS analysis of S. invicta antennal proteins.

| GenInfo Identifier | EST | Protein | Mascot Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 121964777 | C317 | β-Tubulin | 252 |

| 121964735 | C248 | Actin | 201 |

| 124240097 | SiJWE08BBF | Histone 2A | 161 |

| 124222403 | SiJWC04AAD | Chitin-binding | 154 |

| 121964734 | SiJWH08ACX | Si-CSP1 | 151 |

| 124232022 | SiJWD12BBF | Tropomyosin | 138 |

| 121964680 | C180 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 124 |

| 124222949 | SiJWB03AAQ | Chitin-binding | 112 |

| 121974028 | SiJWA06BBS | Si-OBP1 | 111 |

| 124224024 | SiJWA05ADL | Histone 3A | 110 |

| 121964340 | 20H2 | F1 ATP synthase β | 108 |

| 124228667 | SiJWB02AAB | Peroxiredoxin | 106 |

| 124232601 | SiJWH11BBT | Troponin T | 88 |

| 124231738 | SiJWD04BAP | Histone H1/5 | 84 |

| 121964804 | C402 | Aldolase | 79 |

| 124226954 | SiJWE02CAI2 | Si-CSP3 | 78 |

| 124222931 | SiJWC09AAO | Aldo-keto reductase/K channel | 77 |

| 121964716 | C220 | Annexin | 75 |

| 124234459 | SiJWG08BCG1 | Glutathione S transferase | 73 |

| 121964299 | SiJWB01BCJ2 | Fatty acid binding protein | 68 |

| 121964667 | SiJWA05BBH | Si-OBP9 (Gp-9), B allele | 66 |

| 124223427 | SiJWG01AAX | DNA-binding protein | 65 |

| 124229994 | SiJWC03ABM | Protease M16 | 65 |

| 124229908 | SiJWD12ABJ | Medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | 63 |

| 121963759 | 9B1 | JH-inducible protein | 63 |

| 124234194 | SiJWE09BBC2 | Catalase | 61 |

| 124230070 | SiJWA12ABU | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase hinge protein | 61 |

| 124228506 | SiJWE06ACA | Histone H4 | 61 |

| 124230878 | SiJWA07ADR | F1 ATP synthase α | 58 |

| 121964677 | C188 | Calreticulin | 57 |

| 124240522 | SiJWG05BBT | Malate dehydrogenase | 56 |

| 121962904 | 1G12 | Multiple inositol polyphosphate phosphatase | 56 |

| 124228315 | SiJWB07ACG | Chitinase | 53 |

| 121964856 | SiJWD06ABI | Apolipophorin III | 52 |

| 124228358 | SiJWB09AAD | Phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase | 51 |

| 121964514 | SiJWF10BAQ | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | 47 |

| 124231612 | SiJWH10ABW | Sec63 domain protein | 46 |

| 124236391 | SiJWC08BCW2 | Mitochondrial porin | 46 |

| 121964623 | C22 | Elongation factor-1 α | 46 |

| 124236266 | SiJWH11CADR7G01 | Seryl-tRNA synthetase | 42 |

| 124230254 | SiJWD12ADC | α-Tubulin | 42 |

| 121964611 | C5 | Paramyosin | 42 |

Expression of Si-CSP1 in S. invicta worker antenna

Proteins extracted from fire ant worker antennae were analyzed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3). The major low molecular weight protein was subjected to N-terminal Edman degradation, giving the sequence GDLGLYPSEL… This corresponds to the sequence beginning 22 amino acids from the presumed initiation methionine in the protein sequence translated from Genbank cDNA sequence AY713302 (Leal and Ishida, 2008), and also to the protein sequence translated from near the 5′ end of EE134548 (SiJWH08ACX) in the Lausanne Fire Ant EST Library. We refer to this antennal CSP as Si-CSP1. To test whether other CSPs are expressed at high levels in worker antennae, we used a shotgun proteomics approach. Fifty S. invicta worker antenna pairs were extracted and cleaved with trypsin. The tryptic peptides were directly analyzed by capillary LC/MS/MS to view the worker antennal proteome. The results (Table 2) show that Si-CSP1 is detected in the antenna at a high level. We also detected peptides from Si-CSP3. The expression of Si-CSP1 in the antenna was further localized by Leal and Ishida (2008) to the antennal club (the two distal antennal segments). They found no Si-CSP1 in the funiculus, pedicel or scape. We previously showed that all of the porous sensilla are in the club of the S. invicta antenna (Renthal et al., 2003). Since the hemolymph and cuticle are continuous throughout the antenna, Si-CSP1 must be expressed in a compartment that is unique to the antennal club, most likely olfactory sensilla.

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of S. invicta worker antenna proteins. Proteins were electro-blotted onto PVDF film, stained with Coomassie blue, and imaged. The circled spot was cut out and subjected to N-terminal Edman degradation. Sequence corresponds to Si-CSP1.

Of the 42 proteins identified in Table 2, many have known or possible functions in olfaction, including two members of the odorant-binding protein (OBP) family, glutathione- and peroxide-related enzymes (Rogers et al., 1999; Novoselov et al., 1999), and hydrophobic ligand-binding proteins, including a lipocalin and apolipophorin III, which we previously identified as a major antennal protein in the fire ant (Guntur et al., 2004). The two antennal OBPs are Si-OBP9 (Gp-9) and Si-OBP1. Previous studies suggested that Gp-9 is present in the hemolymph (Krieger and Ross, 2002), so it is not clear whether it is expressed in the antenna and whether it has a particular role in olfaction. However, Si-OBP1 is a sequence homolog of A. mellifera OBP1, known to be expressed only in the honeybee antenna (Forêt and Maleszka, 2006) and reported to bind to the queen pheromone (Danty et al., 1999). Our finding of Si-OBP1 and Si-OBP9 (Gp-9) is the first report of a member of the OBP family in an ant antenna. Previous analyses of ant antennal proteins found only CSPs (Ishida et al., 2002; Ozaki et al., 2005), and this generated a discussion of whether some ants might preferably use CSPs rather than OBPs for olfaction (Cavello et al., 2005). The presence of Si-OBP1 in the fire ant antenna suggests that S. invicta may use both OBPs and CSPs for olfaction.

Recombinant Si-CSP1

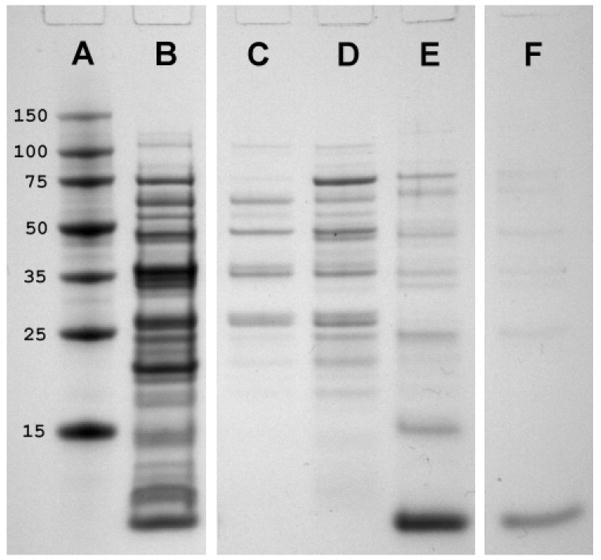

Because the most abundant CSP in C. japonicus worker antennae was shown to bind to nestmate recognition signals, we reasoned that Si-CSP1, the most abundant CSP in S. invicta worker antennae, may also be involved in nestmate recognition. Therefore, we expressed recombinant Si-CSP1 in order to determine its ligand binding properties. Transformed E. coli cells were induced to express Si-CSP1. Extraction from the cell pellet and purification (Fig. 4) typically yielded 20 mL of 50–100 μM Si-CSP1 per liter of medium. For some experiments, a final gel permeation step on a Superdex-75 column was included. Calibration of the column with proteins of known molecular weight showed that Si-CSP1 (expected molecular weight = 10.7 kDa) eluted at the same position as horse myoglobin (molecular weight = 17.7 kDa), indicating that Si-CSP1 is a dimer under physiological conditions.

Figure 4.

Purification of Si-CSP1 from E. coli. Lane A: mol. wt. markers, kDa; B: whole cell extract; C: DEAE column flowthrough; D: 0.2 M NaCl wash; E: 0.35 M NaCl wash; F: phenyl sepharose eluent.

Recombinant Si-CSP1 was cleaved with trypsin and the tryptic peptides were analyzed by capillary LC/MS/MS, confirming the expected amino acid sequence with 74% sequence coverage. Although an N-terminal methionine had been engineered into the sequence from the Nde I restriction site, the mass spectrum shows that this amino acid was post-translationally removed by E. coli methionine N-terminal peptidase.

Ligand binding properties of Si-CSP1

We studied the ligand-binding properties of recombinant Si-CSP1, the major fire ant worker antennal CSP. Because the major CSP of Camponotus japonicus was shown to be involved in nestmate recognition (Ozaki et al., 2005), we speculated that knowing the endogenous ligands of Si-CSP1 could provide information about the nestmate recognition signaling system of fire ants. Previous studies of CSPs from other insects showed that 1-N-phenylnaphthylamine (NPN) undergoes a strong fluorescence enhancement upon binding (Ban et al., 2002). Therefore, we measured fluorescence excitation spectra of NPN added to Si-CSP1, monitoring the emission of NPN at 410 nm, a wavelength where it has low fluorescence in water (Fig. 5A). The upper curve of Fig. 5A indicates strong binding to Si-CSP1: the emission of the dye shifts to 410 nm, showing that it is in a non-polar environment. Also, a peak appears at 280 nm, due to fluorescence resonance energy transfer (Lakowicz, 2006) from tryptophan in Si-CSP1 to the bound NPN, indicating that the dye and the tryptophan are in close spatial proximity. The homology model for liganded Si-CSP1 shows a tryptophan near each open end of the ligand-binding cavity (Trp 24 and Trp 83). Plotted as a binding curve, the fluorescence enhancement levels off at high NPN concentrations, indicating binding to discrete sites (Fig. 5B). We have modeled the binding with a cooperative Adair-type sequential binding model (Imai, 1973), assuming two interacting binding sites. The line in Fig. 5B is fit with dissociation constants of K1 = 30 μM and K2 = 8 μM. The stronger binding occurs only after the weaker site is filled.

Figure 5.

Binding of 1-N-phenylnaphthylamine (NPN) to Si-CSP1. A. Fluorescence excitation spectra. Curve 1: 0.6 μM Si-CSP1 plus 10 μM NPN in 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.2. Curve 2: 10 μM NPN in 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.2. Curve 3: 0.6 μM Si-CSP1 in 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.2. B. Change in fluorescence as NPN is added to Si-CSP1. Excitation wavelength, 340 nm. Line fitted to data assuming two binding sites and cooperative interaction. Ordinates are in arbitrary units of fluorescence intensity.

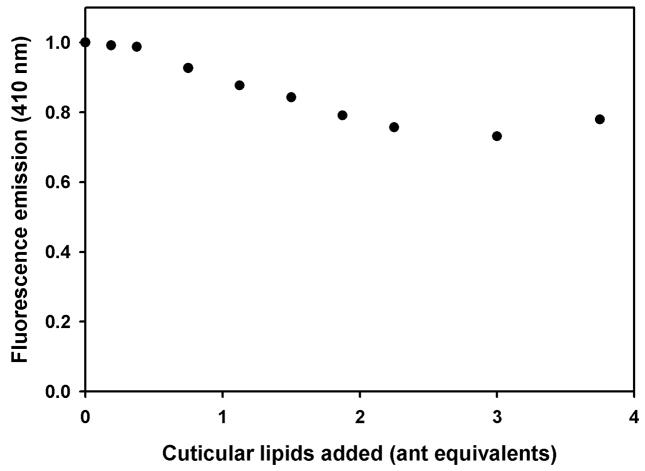

We used NPN binding to test the relative affinities for Si-CSP1 of components of S. invicta cuticular lipids. Ligands for CSPs in other insects were shown to compete with NPN for the CSP binding site (Ban et al., 2002; 2003), causing a decrease in fluorescence with increasing added ligand. Alkane solvent extracts of fire ant cuticle are known to contain a variety of polar lipids in addition to hydrocarbons (Lok et al., 1975). We concentrated pentane washes of fire ant worker cuticle and separated the components by thin layer chromatography (TLC) into four fractions. Based on Rf values (Kates, 1972), we tentatively identify the main components of fraction I as hydrocarbons and wax esters, fraction II as triglycerides, fraction III as fatty acids, and fraction IV as sterols. The Si-CSP1/NPN complex was titrated with purified fractions. The per cent displacement of NPN by the TLC fractions was: I, 13%; II, 7 %; III, 21%; and IV, 0%. The results for fraction III are shown in Fig. 6. However, conclusions from this experiment are limited by the low resolution of TLC separations, and also by the insolubility of the cuticular extracts in aqueous buffer.

Figure 6.

Binding of cuticular lipids to Si-CSP1. Fraction III from TLC separation of cuticular lipids added to NPN/Si-CSP1 complex. Fluorescence decrease shows components of fraction III (probably fatty acids) displace NPN from its binding site on Si-CSP1. Ordinate is fluorescence relative to no addition of fraction III.

Cyclodextrins as hydrophobic ligand transfer agents

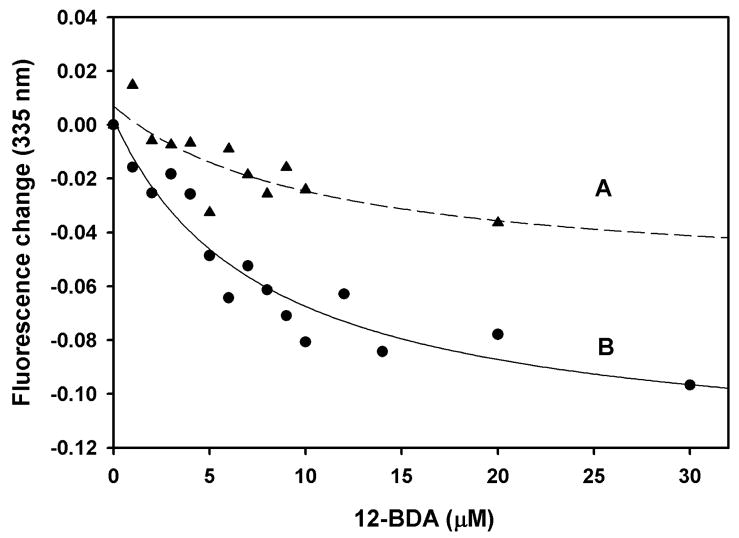

In the competitive binding experiments (Fig. 6), the amount of cuticular lipids added were approximately in a 10-fold molar excess over protein, yet the results suggest that the ligands cannot displace all of the NPN from Si-CP1 (estimate based on the cuticular lipid analysis of Lok et al., 1975). To test whether this could be an artifact of the low aqueous solubility of cuticular lipids, we sought a solubilizing agent which would not compete with the ligands for the CSP binding site. Cyclodextrins (CDs) are widely used as carriers for water-insoluble substances in the pharmaceutical industry (Szejtli, 1998). Therefore, we tested the effect of β-CD on the binding of 12-bromododecanoic acid (12-BDA) to Si-CSP1. Brominated fatty acid esters were previously shown to quench the intrinsic fluorescence of CSPs from moths (Campanacci et al., 2003). We found that, as expected, 12-BDA quenches the tryptophan fluorescence of Si-CSP1 (Fig. 7), indicating that it binds to Si-CSP1. However, the quenching was greater when the same amount of 12-BDA was added along with β-CD. The results suggest that 12-BDA, which is only slightly soluble in water, is more soluble if β-CD is present. Lines fitted to the data in Fig. 7 show that cyclodextrin does not enhance the affinity of 12-BDA for Si-CSP1, but instead β-CD makes more 12-BDA available for binding.

Figure 7.

Cyclodextrin transfers 12-bromododecanoic acid (12-BDA) to Si-CSP1. A. Binding of 12-BDA to Si-CSP1 detected by quenching of tryptophan fluorescence. B. Same as A. except with 0.5 mM β-cyclodextrin. Conditions: 0.6 μM Si-CSP1, 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.2. 12-BDA added as 1 μL aliquots of 1 mM or 10 mM stock solutions in methanol. Excitation wavelength, 280 nm. Emission wavelength, 335 nm. Lines fitted to data assuming saturation binding of 12-BDA to a single site on Si-CSP1.

Although CDs enhance the amount of ligand available for binding to Si-CSP1, the competition between endogenous ligands and NPN binding cannot be measured in the presence of CDs because NPN binds to β- and γ-CD, with fluorescence enhancement that renders it useless for competition studies. However, we found that ligand-transfer and NPN competition could be done in separate steps. First Si-CSP1 was electrostatically adsorbed onto a solid support (DEAE cellulose). Next, the adsorbed Si-CSP1 was equilibrated with a cuticular lipid extract dispersed in a mixture of α-, β-, and γ-CD, allowing Si-CSP1 to select the components for which it has a high affinity. Then, the lipid-CD complex was washed away, leaving Si-CSP1 adsorbed on the solid support bound to any lipids it captured. Finally, the Si-CSP1 was eluted from the solid support with a salt wash. The eluted Si-CSP1, completely free of CD, was then titrated with NPN to assess the available binding sites. We found that Si-CSP1 that had been exposed to a CD dispersion of cuticular lipids showed virtually no binding to NPN (Fig. 8). The cuticular lipids equilibrated with the sample had approximately a 6:1 molar ratio of hydrocarbons to protein and about 1:1 fatty acids and esters to protein (Lok et al., 1975). A control sample of Si-CSP1 was equilibrated on DEAE cellulose with CD containing no cuticular extract, and we found that there was no inhibition of NPN binding (Fig. 8). Thus, components of the fire ant cuticular extract bind tightly to Si-CSP1 and cannot be displaced by NPN.

Figure 8.

Binding of cuticular lipids to Si-CSP1. Binding of NPN to Si-CSP1 (circles) enhances the dye fluorescence (similar to Fig. 5B). However, Si-CSP1 which first had been exposed to cuticular lipids carried by cyclodextrins (triangles) shows NPN fluorescence diminished to the same level as a control sample lacking Si-CSP1 (squares). Si-CSP1 bound to DEAE-cellulose and exposed to cyclodextrins lacking the cuticular extract (diamonds) had no effect on subsequent NPN binding.

Previous studies of hydrophobic ligand-binding proteins have been limited by the problem of water-insolubility of the ligands. A variety of methods to overcome this problem have been reported, including transferring the ligands across a liquid/liquid or liquid/solid phase boundary (Du and Prestwich, 1995; Margaryan et al., 2006), or dispersing the ligand in detergent micelles (Ozaki et al., 2005). There are drawbacks to these methods. Using two-phase systems makes it difficult to measure meaningful binding free energy changes. Using detergents can be a problem because the detergent monomer may compete with ligands for the binding site on the protein. One advantage of cyclodextrins as dispersing agents for hydrophobic ligands is that, unlike detergents, cyclodextrins do not directly compete with ligands for binding sites on the protein. Furthermore, cyclodextrins may permit exact measurements of binding free energy changes by linked equilibria.

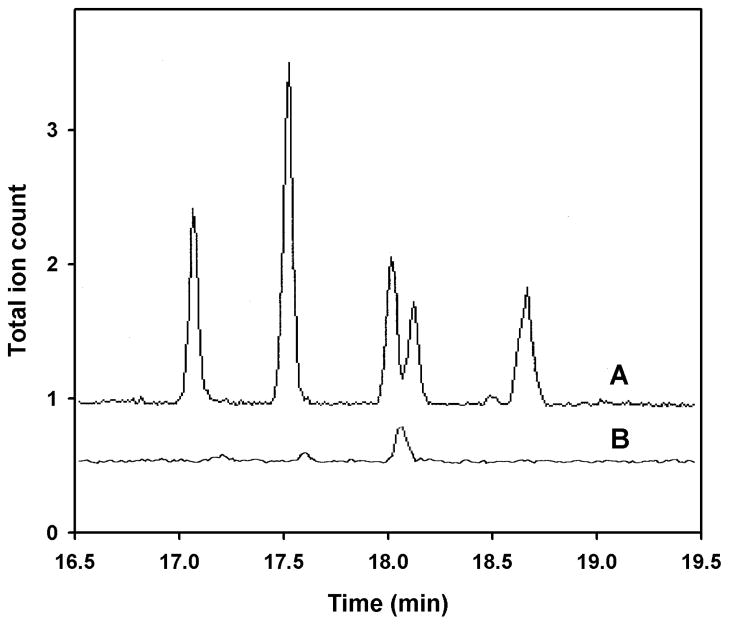

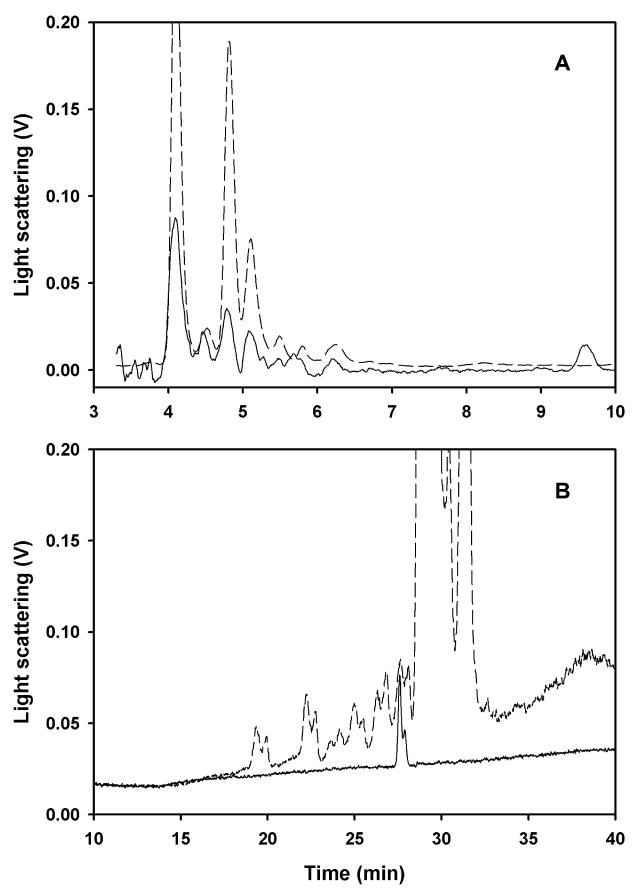

Nestmate recognition signals

In order to find out what components of cuticular lipids had been captured by Si-CSP1, we extracted the eluted Si-CSP1 with methylene chloride and analyzed the extract by GCMS and HPLC. The results show that Si-CSP1 does not bind to cuticular hydrocarbons (Fig. 9), but Si-CSP1 does bind to polar cuticular lipids (Fig. 10). The compounds captured by Si-CSP1 have elution times characteristic of fatty acids (Fig. 10A) and esters such as triglycerides (Fig. 10B). If the major S. invicta CSP carries nestmate recognition signals, by analogy to Cj-CSP1 (Ozaki et al., 2005), then cuticular hydrocarbons are not involved in nestmate recognition in S. invicta. Alternatively, if the nestmate recognition signals in S. invicta are composed of cuticular hydrocarbons, then the major antennal CSP does not carry this signal. Tschinkel (2006) summarized many behavioral and chemical experiments reported by Vander Meer and colleagues and argued that cuticular hydrocarbons were unlikely to be the nestmate recognition signal in S. invicta. To clarify this issue, we plan to identify the substances captured by Si-CSP1 (Fig. 10) and test them for activity in nestmate recognition.

Figure 9.

Cuticular hydrocarbon GC analysis of ligands captured by Si-CSP1. A). GC trace of pentane extract of fire ant cuticle showing 5 main components of cuticular hydrocarbons. B). Si-CSP1 bound to DEAE cellulose was equilibrated with the same extract as in A dispersed in cyclodextrins, eluted with salt, and extracted with methylene chloride. GC trace in B is scaled to the amount of extract in A, assuming each Si-CSP1 molecule can capture at least one hydrocarbon molecule. Mass spectrum of peak in trace B at 18.1 min identifies it as a polysiloxane contaminant. Total ion current X 10−5.

Figure 10.

Cuticular lipid HPLC analysis of ligands captured by Si-CSP1. Si-CSP1 bound to DEAE cellulose was equilibrated with cyclodextrin-dispersed CHCl3/methanol fraction (A), or cyclodextrin-dispersed pentane fraction (B), of silica-purified cuticular lipids, followed by salt elution and CHCl3/methanol extraction. HPLC analysis on C18 column, eluted with linear gradient between acetonitrile:isopropanol 1:1 and chloroform. Dashed lines: whole extract; solid lines: captured by Si-CSP1. In (A) whole extract is at 1/5 scale for clarity.

Experimental procedures

Ants

Polygyne colonies of S. invicta were collected by floatation (Jouvenaz et al., 1977) from nests found in Bexar County, Texas, and maintained in the lab in plastic trays.

2D gel electrophoresis and N-terminal sequencing

Two dimensional gel electrophoresis and N-terminal sequencing were done as previously described (Guntur et al., 2004).

Identification of CSP sequences in the Lausanne fire ant EST library

The Lausanne fire ant EST library (Wang et al., 2007) was downloaded onto a Dell 670 workstation in the UTSA Computational Biology Core Facility. The library was expanded into a six-frame translation. Stand-alone Blast was used to run a Seedtop pattern search, with the following Prosite pattern: C-x(6)-C-x(18,19)-C-x(2)-C. Other hymenopteran CSP sequences were identified with BLAST, using the translated S. invicta sequences to search hymenopteran EST libraries. Sequences were aligned using CLC Sequence Viewer software (CLC bio, Arhus, Denmark) and arranged in a phylogenetic tree using Phylip software.

Recombinant CSP1

cDNA derived from fire ant antennae, containing the Si-CSP1 gene, was amplified by PCR with the following primers: forward, 5′ TTAGCATATGGGAGACTTGGGACTCTATCC; and reverse, 5′ TTAGGCTCGGGCATCTTCAAGTATTATTTTCCAAA. The primers introduced an Nde I restriction site in the forward primer and an Xho I restriction site in the reverse primer. The PCR product was cloned into pCR-blunt-II™ (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The gene was then moved into pET21a and used to transform BL21 (λDE3) E. coli cells. Expression was induced overnight at 28° in lactose-containing LB medium. The cell pellet was extracted with t-butanol/water and the aqueous phase was precipitated with 0.5 M ammonium sulfate. The supernatant was dialyzed and applied to a DE52 column. The 0.35 M NaCl eluent was applied to a phenyl sepharose column in 0.5 M ammonium sulfate and eluted with 20 mM Tris, pH 8.4 A final purification step was done on a Superdex-75 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) in 0.02 M Tris, pH 7.2, 0.1 M NaCl.

Mass spectrometry

Antennal extracts (Guntur et al., 2004) or purified recombinant CSP1 fractions were unfolded in 8 M guanidinium containing 5 mM dithiothreitol at 60°C for 1 hr followed by treatment with 20 mM iodoacetamide. After addition of excess dithiothreitol and six-fold dilution with buffer, the protein was hydrolyzed with trypsin (Gold, mass spectrometry grade, Promega; 1:20 w:w) for 1 hr at 37°C. Capillary liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) was performed with a 50 μm internal diameter capillary LC column packed with 10 cm of 5 μm C18 particles, a linear gradient from 2 to 98% acetonitrile\0.1% formic acid at 500 nL/min (Eksigent, Livermore, CA) in 60 min, and a linear ion trap (ThermoFisher, San Jose, CA) where the top 7 ions are fragmented by collision-induced dissociation. MASCOT (Matrixscience, London, UK) searches of MS/MS spectra were performed with a 10 node Linux cluster against a 6-frame translation of the NCBI S. invicta EST database with 1000 ppm and 0.8 Da precursor and product ion mass tolerances, respectively.

Cuticular lipid analysis

For each extraction, thirty ice-anesthetized foraging workers were extracted for 5 min at room temperature in 2 mL pentane. After evaporation under N2, the residue was solubilized in a small volume of pentane and spotted on a glass-backed silica TLC plates (250 μm silica gel 60, Sigma). The plates were developed first with petroleum ether:toluene 9:1 v:v and then with hexane:ethyl acetate:acetic acid 6:4:0.4 v:v:v. Lipids were visualized by ashing (5% concentrated sulfuric acid/ethanol spray followed by heating to 110°C). Regions on non-ashed plates corresponding to lipid spots were scraped, eluted with 1 mL methanol, and concentrated to 200 μL by evaporation under N2. Hydrocarbon analyses of extracts were done on a HP 5971A GC/MS using an Agilent HP-1 column. For some experiments (e.g. Fig. 10), cuticular pentane washes were fractionated on Waters (Milford, MA) Sep-Pak Classic silica cartridges and then eluted with pentane, followed by chloroform:methanol 1:1 (v:v). HPLC analysis was done on a Grace (Deerfield, IL) Alltima HP C18 HL 5 μ column, using LDC Constametric pumps and a Varian 380-LC evaporative light scattering detector. The Sep-Pak fractions were dried under N2 and applied to the C18 column in hexane (pentane fraction) or acetonitrile:isopropanol 1:1 (v:v) (chloroform:methanol fraction). Prior to sample injection, the column was equilibrated with acetonitrile:isopropanol 1:1. Three minutes after injection, a 30 minute linear gradient was run with chloroform, ending at 60% acetonitrile:isopropanol 1:1 and 40% chloroform. With this separation system, palmitic acid eluted at 5.1 min and tripalmitin eluted at 24.2 min.

Ligand binding

Fluorescence spectra were measured on a PTI QuantaMaster QM4 fluorometer. Ligand capture experiments were done as follows. Twenty worker ants were washed with 2 mL pentane for 5 min. and the pentane was removed and evaporated under a flow of nitrogen. The residue was dissolved in 20 μL acetonitrile and added to 1.2 mL 20 mM Tris, pH 8.4 containing 0.17 mM each of α-, β-, and γ-cyclodextrin. In some experiments (e.g. Fig. 10) separate dried pentane and chloroform/methanol Sep-Pak fractions were solubilized in acetonitrile:isopropanol 1:1 and added to aqueous cyclodextrins. A solution of 0.8 mL of Si-CSP1 (80 nmol) in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.4 was combined with the cyclodextrin-solubilized cuticular extract and added to 250 mg buffer-washed DEAE cellulose (Whatman DE52; equilibrated with 5 mL 20 mM Tris, pH 8.4 and washed twice, by centrifugation and resuspension, with 5 mL portions of 20 mM Tris, pH 8.4). The suspension was stirred gently with a magnetic stirring bar for 20 min at room temperature and then centrifuged. After two washes with 20 mM Tris, pH 8.4, the Si-CSP1 was eluted from the DE52 by gently stirring for 10 min with 1 mL of 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, containing 150 mM NaCl. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed and extracted with hexane, or methylene chloride, or chloroform and methanol (Bligh and Dyer, 1959). The organic layer was removed, evaporated, and resuspended in a smaller volume of solvent for subsequent analysis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sruthi Eedala for technical assistance, and John Wang and Laurent Keller for providing access to the Lausanne Fire Ant EST library prior to its release. Supported by grants from the Texas Imported Fire Ant Research and Management Program and the National Institutes of Health (G12 RR013646).

References

- Ban LP, Zhang L, Yan Y, Pelosi P. Binding properties of a locust’s chemosensory protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:50–54. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ban LP, Scaloni A, Brandazza A, Angeli S, Zhang L, Yan YH, Pelosi P. Chemosensory proteins of Locusta migratoria. Insect Mol Biol. 2003;12:125–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method for total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briand L, Swasdipan N, Nespoulous C, Bézirard V, Blon F, Huet JC, Ebert P, Pernollet JC. Characterization of a chemosensory protein (ASP3c) from honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) as a brood pheromone carrier. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:4586–4596. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanacci V, Lartigue A, Hällberg BM, Alwyn Jones T, Giudici-Orticoni MT, Tegoni M, Cambillau C. Moth chemosensory protein exhibits drastic conformational changes and cooperativity on ligand binding. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5069–5074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0836654100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvello M, Guerra N, Brandazza A, D’Ambrosio C, Scaloni A, Dani FR, Turillazzi S, Pelosi P. Soluble proteins of chemical communication in the social wasp Polistes dominulus. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1933–1943. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3186-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvello M, Brandazza A, Navarrini A, Dani FR, Turillazzi S, Felicioli A, Pelosi P. Expression of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in some Hymenoptera. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danty E, Briand L, Michard-Vanhee C, Perez V, Arnold G, Gaudemer O, Huet D, Huet JC, Ouali C, Masson C, Pernollet JC. Cloning and expression of a queen pheromone-binding protein in the honeybee: an olfactory-specific, developmentally regulated protein. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7468–7475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07468.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du G, Prestwich GD. Protein structure encodes the ligand binding specificity in pheromone binding proteins. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8726–8732. doi: 10.1021/bi00027a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forêt S. PhD dissertation. Australian National University; 2007. Function and evolution of putative odorant carriers in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) [Google Scholar]

- Forêt S, Maleszka R. Function and evolution of a gene family encoding odorant binding-like proteins in a social insect, the honey bee (Apis mellifera) Genome Res. 2006;16:1404–1413. doi: 10.1101/gr.5075706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forêt S, Wanner KW, Maleszka R. Chemosensory proteins in the honey bee: Insights from the annotated genome, comparative analyses and expressional profiling. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2007;37:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntur KVP, Velasquez D, Chadwell L, Carroll CA, Weintraub ST, Cassill JA, Renthal R. Apolipophorin-III-like protein expressed in the antenna of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2004;57:101–110. doi: 10.1002/arch.20019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefetz A. The evolution of hydrocarbon pheromone parsimony in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) – interplay of colony odor uniformity and odor idiosyncrasy. A review. Myrmecological News. 2007;10:59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Howard RH, Blomquist GJ. Ecological, behavioral, and biochemical aspects of insect hydrocarbons. Annu Rev Entomol. 2005;50:371–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K. Analyses of oxygen equilibria of native and chemically modified human adult hemoglobins on the basis of Adair’s stepwise oxygenation theory and the allosteric model of Monod, Wyman, and Changeux. Biochemistry. 1973;12:798–808. doi: 10.1021/bi00729a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida Y, Chiang V, Leal WS. Protein that makes sense in the Argentine ant. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:505–507. doi: 10.1007/s00114-002-0368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouvenaz DP, Allen GE, Banks WA, Wojcik DP. A survey for pathogens of fire ants, Solenopsis spp. in the southeastern United States. Florida Ent. 1977;60:275–279. [Google Scholar]

- Kates M. Techniques of lipidology. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1972. p. 503. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger MJB, Ross KG. Identification of a major gene regulating complex social behavior. Science. 2002;295:328–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1065247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahav S, Soroker V, Hefetz A, Vander Meer RK. Direct behavioral evidence for hydrocarbons as ant recognition discriminators. Naturwissenschaften. 1999;86:246–249. [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz JR. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. Springer; NY: 2006. pp. 443–527. [Google Scholar]

- Leal WS, Ishida Y. GP-9s are ubiquitous proteins unlikely involved in olfactory mediation of social organization in the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(11):e3762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok JB, Cupp EW, Blomquist GJ. Cuticular lipids of the imported fire ants, Solenopsis invicta and richteri. Insect Biochem. 1975;5:821–829. [Google Scholar]

- Margaryan A, Moaddel R, Aldrich JR, Tsuruda JM, Chen AM, Leal WS, Wainer IW. Synthesis of an immobilized Bombyx mori pheromone-binding protein liquid chromatography stationary phase. Talanta. 2006;70:752–755. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2006.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleszka J, Forêt S, Maleszka R. RNAi-induced phenotypes suggest a novel role for a chemosensory protein CSP5 in the development of embryonic integument in the honeybee (Apis mellifera) Dev Genes Evol. 2007;217:189–196. doi: 10.1007/s00427-006-0127-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novoselov SV, Peshenko IV, Popov VI, Novoselov VI, Bystrova MF, Evdokimov VJ, Kamzalov SS, Merkulova MI, Shuvaeva TM, Lipkin VM, Fesenko EE. Localization of 28-kDa peroxiredoxin in rat epithelial tissues and its antioxidant properties. Cell and Tissue Res. 1999;298:471–480. doi: 10.1007/s004419900115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki M, Wada-Katsumata A, Fujikawa K, Iwasaki M, Yokohari F, Satoji Y, Nisimura T, Yamaoka R. Ant nestmate and non-nestmate discrimination by a chemosensory sensillum. Science. 2005;309:311–314. doi: 10.1126/science.1105244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi P, Calvello M, Ban L. Diversity of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in insects. Chem Senses. 2005;30 (suppl 1):i291–i292. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelosi P, Zhou JJ, Ban LP, Calvello M. Soluble proteins in insect chemical communication. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1658–1676. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5607-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renthal R. Discovering pheromones of the red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta Buren): A review of and proposed new target for pheromone disruption. J Agricultural and Urban Entomol. 2003;20:113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Renthal R, Velasquez D, Olmos D, Hampton J, Wergin WP. Structure and distribution of antennal sensilla of the red imported fire ant. Micron. 2003;34:405–413. doi: 10.1016/S0968-4328(03)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ME, Jani MK, Vogt RG. An olfactory-specific glutathione-S-transferase in the sphinx moth Manduca sexta. J Exp Biol. 1999;202:1625–1637. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.12.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwede T, Kopp J, Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31:3381–3385. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szejtli J. Introduction and general overview of cyclodextrin chemistry. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1743–1753. doi: 10.1021/cr970022c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas ML, Parry LJ, Allan RA, Elgar MA. Geographic affinity, cuticular hydrocarbons and colony recognition in the Australian meat ant Iridomyrmex purpureus. Naturwissenschaften. 1999;86:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tschinkel WR. The Fire Ants. Harvard U. Press; Cambridge: 2006. pp. 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Vander Meer R, Morel L. Nestmate recognition in ants. In: Vander Meer R, Breed MD, Espelie KE, Winston ML, editors. Pheromone Communication in Social Insects. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1998. pp. 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D, Tissot M, Cuevas W, Gordon DM. Harvester ants utilize cuticular hydrocarbons in nestmate recognition. J Chem Ecol. 2000;26:2245–2257. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Jemielity S, Uva P, Wurm Y, Graff J, Keller L. An annotated cDNA library and microarray for large-scale gene-expression studies in the ant Solenopsis invicta. Genome Biology. 2007;8(1):R9. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-1-r9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner K, Willis L, Theilmann D, Isman M, Feng Q, Plettner E. Analysis of the insect OS-D-like gene family. J Chem Ecol. 2004;30:889–911. doi: 10.1023/b:joec.0000028457.51147.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou JJ, Kan Y, Antoniw J, Pickett JA, Field LM. Genome and EST analyses and expression of a gene family with putative functions in insect chemoreception. Chem Senses. 2006;31:453–465. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjj050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]