Abstract

Background and Objectives

The incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery is known to be very rare; there have been few prior studies on this topic. We evaluated the incidence, predictors, and prognosis of atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery.

Subjects and Methods

Patients who underwent noncardiothoracic surgery at our medical center under general anesthesia were enrolled. We reviewed medical records retrospectively and evaluated whether the atrial fibrillation developed postoperatively or was pre-existing. Patients who had a previous history of atrial fibrillation or atrial fibrillation on the pre-operative electrocardiogram were excluded.

Results

Between January 2005 and December 2006, 7,756 patients (mean age: 69 years, male: 46%) underwent noncardiothoracic surgery in Samsung Medical Center and 30 patients (0.39%) were diagnosed with newly-developed atrial fibrillation. Patients who developed atrial fibrillation were significantly older and had significantly lower body mass indexes. Newly-developed atrial fibrillation was detected in 0.53% of the male patients and 0.26% of the female patients. The incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation after an emergency operation was more frequent than that of elective operations (p<0.001). According to the multivariate analysis, age and emergency operations were independent predictors for new onset atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery. Postoperative atrial fibrillation developed after a median of 2 days after the noncardiothoracic surgery and was associated with a longer hospitalization and increased in-hospital mortality. Four (13.3%) patients died and the causes of death were non-cardiovascular events such as pneumonia or hemorrhage.

Conclusion

Postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery is a rare complication and is associated with older age and emergency operations. Patients who develop atrial fibrillation have longer hospitalizations and higher in-hospital mortality rates.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Surgery, Postoperative complications

Introduction

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation is somewhat higher in the elderly population; the researchers in one study found atrial fibrillation in 0.7% of people older than 40 years and in 2.1% of those older than 65 years in Korea.1) Furthermore, atrial fibrillation occurs in 10% to 65% of patients after cardiac surgery and is known to be associated with increased morbidity and mortality and longer hospital stays.2) In comparison to postoperative atrial fibrillation in cardiothoracic surgery, the incidence of atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery is very rare; few studies on this topic have been reported. Although one study on postoperative atrial fibrillation in noncardiothoracic surgical patients in the United States was reported, it included participants who had had a history of atrial fibrillation.3) We evaluated the incidence, predictors, and prognosis of new onset atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery.

Subjects and Methods

Patients who underwent noncardiothoracic surgery under general anesthesia between January 2005 and December 2006 at the Samsung Medical Center in Korea were enrolled. Patients who had a previous history of atrial fibrillation or who had atrial fibrillation on the pre-operative electrocardiogram were excluded from participating. Patients who were younger than 62 years were excluded because the incidence of atrial fibrillation in young people is very low.

Postoperative atrial fibrillation was defined as a new onset of atrial fibrillation after surgery and during hospitalization. We reviewed the medical records, including the pre- and post-operative electrocardiograms, vital signs, consult sheets, discharge summaries, nursing information, and intensive care unit records of these patients and determined whether the atrial fibrillation was preexisting or new onset.

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows (version 13.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all of the analyses. Continuous data are expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD) and the categorical data are expressed as percentages. Statistical comparisons of the baseline and the outcome variables were performed for the categorical data using the Chisquared test or Fisher's exact test (if the expected value of the variable was <5 in at least on group). For continuous variables, Student's t-test was applied. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between the predictor variables. A p of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

During 2 years, a total of 7,756 patients who were older than 61 years and underwent noncardiothoracic surgery at the Samsung Medical Center were enrolled. The mean age was 68.9±5.3 years and 3,600 (46.4%) of the patients were male. The mean body weight was 61.7±9.8 kg and the mean height was 158.3±9.0 cm. The prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus were 47.8% and 19.5%, respectively. We found that 12.5% of the patients were current smokers at the time of their surgeries. A total of 3,392 (43.7%) patients underwent general surgery, 2,239 (28.9%) patients orthopedic surgery, 655 (8.4%) patients neurosurgery, 575 (7.4%) patients head & neck surgery, 511 (6.6%) patients urologic surgery, 261 (3.4%) patients gynecologic surgery, and 123 (1.59%) patients underwent other surgeries. Additionally, 868 (11.2%) of these 7,756 patients had emergency operations. Finally, the mean hospital stay for all patients was 13.9±18.8 days and a total of 68 (0.9%) patients died while in the hospital. During postoperative care, 164 (2.11%) patients had myocardial infarction and 37 (0.48%) patients had positive blood cultures.

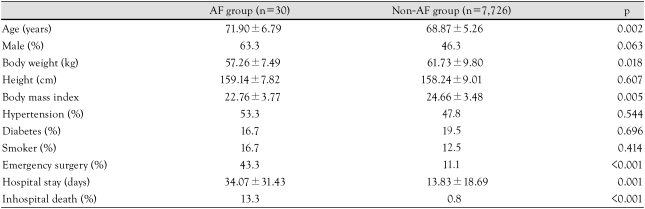

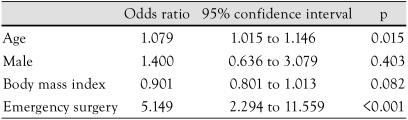

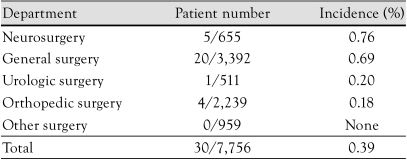

During their hospitalizations, 30 (0.39%) patients were diagnosed with newly-developed atrial fibrillation after a noncardiothoracic operation. There were no significant differences in height or in the proportion of smokers between the patients in the atrial fibrillation group and the patients in the non-atrial fibrillation group (Table 1). The patients with newly-developed atrial fibrillation had similar proportions of medical comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes compared with the group of patients who did not develop atrial fibrillation. Newly-developed atrial fibrillation was detected in 19 (0.53%) of the 3,600 male patients and in 11 (0.26%) of the 4,156 female patients; there was no significant difference in the multivariate analysis (Table 2). Patients who developed atrial fibrillation were significantly older and had lower body mass indexes than patients who did not. Postoperative atrial fibrillation developed more frequently among patients who underwent an emergency operation than in those who underwent an elective operation (1.5% vs. 0.2%, p<0.001). According to the multivariate analysis, age and an emergency operation were independent predictors for developing new onset atrial fibrillation after a noncardiothoracic surgery (Table 2). According to the associated surgical departments, postoperative atrial fibrillation was the most common after neurosurgery and did not occur after gynecologic, head and neck, plastic, or ophthalmologic surgeries (Table 3).

Table 1.

Comparisons of variables between the AF group and the non-AF group

AF: atrial fibrillation

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of predictors for the development of postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery

Table 3.

Incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation according to the associated surgical department

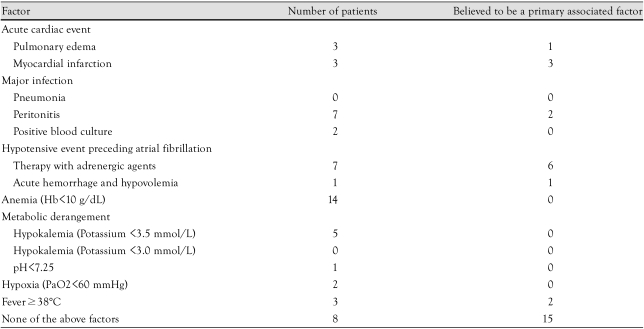

Table 4 shows the predisposing factors contributing to the development of new postoperative atrial fibrillation. Fifteen patients (50%) had no predisposing factors that could cause atrial fibrillation and six patients (20%) had hypotensive events that required adrenergic agents to maintain their systolic blood pressure.

Table 4.

Factors contributing to the onset of new postoperative atrial fibrillation

Twenty-eight patients who developed atrial fibrillation underwent Doppler echocardiography preoperatively or after the development of atrial fibrillation. The mean left atrial dimension and mean left ventricular ejection fraction were 41.7±5.9 mm and 58.4±12.3%, respectively. Seven patients had regional wall motion abnormalities and four patients had ejection fractions below 55%. One patient had a prosthetic mitral and aortic valve and two patients had mild to moderate tricuspid or mitral valve regurgitation.

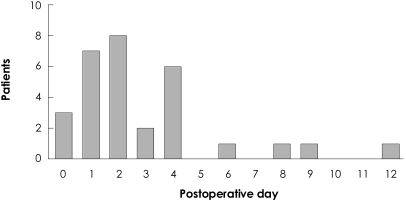

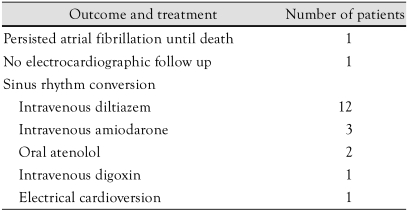

Postoperative atrial fibrillations after noncardiothoracic surgery developed after a median of 2 days (with the earliest occurring on the day of the operation and the latest occurring after 12 days) (Fig. 1). In all of these patients except two, the atrial fibrillation was converted to a sinus rhythm during the hospitalization. One patient died without sinus conversion and the other patient was not followed up electrocardiographically (Table 5). Twelve patients needed intravenous diltiazem, three patients needed intravenous amiodarone, two patients needed oral atenolol, one patient needed intravenous digoxin, one patient needed electrical cardioversion, and 11 patients did not need any intervention for sinus rhythm conversion. Patients who developed postoperative atrial fibrillation were hospitalized longer and had a higher in-hospital mortality rate (Table 1). A total of four patients died prior to their discharge; the causes of death were non-cardiovascular events such as pneumonia, intra-abdominal abscess, or hemorrhage.

Fig. 1.

The postoperative day on which newly-developed atrial fibrillationz was observed. Postoperative atrial fibrillations after noncardiothoracic surgery developed after a median of 2 days (the earliest development was on the operation day and the latest onset was after 12 days).

Table 5.

Treatment of new postoperative atrial fibrillation

Discussion

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the general population is increasing in part because of the aging population and is associated with ischemic strokes and even mortality.4) There are many studies examining the epidemiology, pathophysiology, and the prevention and management of atrial fibrillation.4),5) However, there were few studies about the incidence and consequences of atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgeries.3),6) Brathwaite et al.6) reported that the incidence of new-onset atrial arrhythmias was 10.2%, higher than the incidence reported in the general population. However, these participants were patients who were admitted to the surgical intensive care units after noncardiothoracic surgery. Our incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation after non-cardiothoracic surgery was 0.39% and similar to the 0.37% found in an American report by Christians et al.3) However, Christians et al.3) included patients who had a history of atrial fibrillation, and if those patients were excluded, the incidence would be reduced to 0.27%. However, considering that they included young patients who we excluded in our study because the incidence of atrial fibrillation is low in younger people, the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery in the two studies are comparable. The incidence of atrial fibrillation in this study may be underestimated because asymptomatic atrial fibrillation may not be symptomatic and physicians sometimes do not describe the symptoms or signs of atrial fibrillation in the medical record. Because this limitation results from the retrospective nature of this study, we expect that the incidence would increase if we monitored every postoperative patient with continuous electrocardiography. However, it would be impossible for all of the postoperative patients to be monitored electrocardiographically postoperatively.

We do not know the exact mechanism of postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery, and obviously direct irritation is not a possible cause. Almost one-third of the patients converted to sinus rhythms without any interventions. When the patients did die, the cause of death was not associated with any cardiac problems, which was similar to the findings of Brathwaite et al.6) Therefore, the mechanism of postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery is not a local problem, but related to systemic inflammation or the excessive production of catecholamines.7)

Risk factors for the development of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery are older age, male sex, hypertension, higher body mass index, left atrial enlargement, vascular surgery, and a previous history of atrial fibrillation.7),8) It is possible that the risk factors are different for noncardiothoracic surgery, because the mechanisms may be different. In this study, old age and emergency operations were significantly associated with an increased incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation.

Recently, Zacharias et al.9) documented that body mass index was an important determinant of new-onset atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery and obesity and metabolic syndrome are considered as independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery.7) However, in our study the mean body mass index of patients who developed atrial fibrillation was significantly lower than that of patients who did not. It is uncertain whether a lower body mass index is an independent risk factor because so few patients developed atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery. However, considering that lean people are vulnerable to systemic illnesses like obesity paradox for heart failure,10) this may be a real finding though additional studies are required to confirm this observation.

With the available Doppler echocardiographic data, the mean left atrial dimension was found to be 41.7±5.9 mm. Seventeen (60.71%) of the 28 patients who underwent Doppler echocardiography preoperatively or after the development of atrial fibrillation had left atrial dimensions larger than 35.5 mm, which was the mean size for the Korean population based on data collected in a Korean multicenter study.11) Therefore, left atrial enlargement is likely to be related to postoperative atrial fibrillation. However, valvular dysfunction is not likely to be risk factor because only two of the patients who developed atrial fibrillation had mild to moderate degrees of valvular regurgitation and none had valvular stenosis of greater than a mild degree.

Because of the retrospective nature of this study, there were many limitations and the prospective studies would be required for the incidence and predisposing factors of postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery in Korean patients.

In summary, the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery was 0.39% and was a relatively rare complication. It was associated with older age and emergency surgeries and the extension of hospital stays. Although the in-hospital mortality of patients with new onset atrial fibrillation was increased, the cause of death was not associated with heart problems; most patients who developed postoperative atrial fibrillation after noncardiothoracic surgery had benign courses. Therefore, if postoperative atrial fibrillation occurs, close monitoring and prudent general care are warranted.

References

- 1.Jeong JH. Prevalence of and risk factors for atrial fibrillation in Korean adults older than 40 years. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:26–30. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maisel WH, Rawn JD, Stevenson WG. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:1061–1073. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-12-200112180-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christians KK, Wu B, Quebbeman EJ, Brasel KJ. Postoperative atrial fibrillation in noncardiothoracic surgical patients. Am J Surg. 2001;182:713–715. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00799-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krahn AD, Manfreda J, Tate RB, Mathewson FA, Cuddy TE. The natural history of atrial fibrillation: incidence, risk factors, and prognosis in the Manitoba Follow-Up Study. Am J Med. 1995;98:476–484. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falk RH. Atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1067–1078. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brathwaite D, Weissman C. The new onset of atrial arrhythmias following major noncardiothoracic surgery is associated with increased mortality. Chest. 1998;114:462–468. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.2.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Echahidi N, Pibarot P, O'Hara G, Mathieu P. Mechanisms, prevention, and treatment of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jongnarangsin K, Oral H. Postoperative atrial fibrillation. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zacharias A, Schwann TA, Riordan CJ, Durham SJ, Shah AS, Habib RH. Obesity and risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2005;112:3247–3255. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.553743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis JP, Selter JG, Wang Y, et al. The obesity paradox: body mass index and outcomes in patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:55–61. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park SW. Multicenter trial for estimation of normal values of echocardiographic indices in Korea. Korean Circ J. 2000;30:373–382. [Google Scholar]