Abstract

The study of conflict has dominated psychological research on marriage. This article documents its move from center stage, outlining how a broader canvas accommodates a richer picture of marriage. A brief sampling of new constructs such as forgiveness and sacrifice points to an organizing theme of transformative processes in emerging marital research. The implications of marital transformations are explored including spontaneous remission of distress, nonlinear dynamic systems that may produce unexpected and discontinuous change, possible nonarbitrary definitions of marital discord, and the potential for developing other constructs related to self-transformation in marital research.

Keywords: Commitment, Conflict, Marriage, Relationship Processes, Religion, Satisfaction

Since changing economic and social conditions at the beginning of the last century prompted scientific study of problems in families, marital research has retained a focus on marital distress and dissolution. Central to this focus is the special status accorded conflict in the literature on marriage, especially in the scholarship developed by more psychologically trained and clinically oriented marital researchers. We argue, however, that the focus on conflict has become limiting, and that recent empirical developments have created a new intellectual climate in which the study of transformative processes will assume center stage.

Conflict: From Center to Side Stage

Has there truly been a focus on conflict among psychologically trained marital researchers? We believe so, and offer several lines of evidence. First, many of the most influential theories of marriage found in the clinical psychological literature tend to reflect the view that “distress results from couples' aversive and ineffectual response to conflict” (Koerner & Jacobson, 1994, p. 208). Second, Rusbult's work on accommodation has focused attention on constructive responses between partners in response to conflicting desires (Rusbult, Zembrodt, & Gunn, 1982). Third, observational research on marriage has focused on what spouses do when they disagree with each other, and reviews of marital interaction are dominated by studies of conflict and problem solving (see Booth, Crouter, & Clements, 2001; Kelly, Fincham, & Beach, 2003; Weiss & Heyman, 1997). Fourth, programs to prevent marital distress (see Bodenmann & Shantinath, 2004; Markman, Renick, Floyd, Stanley, & Clements, 1993; Stanley, Blumberg, & Markman, 1999) and interventions to ameliorate distress often target conflict dynamics (see Baucom, Shoham, Mueser, Daiuto, & Stickle, 1998).

The status accorded conflict in the marital literature generated by psychological researchers is not without merit. For example, marital conflict is associated with increased risk for a major depressive episode (Whisman & Bruce, 1999), abuse of partners (O'Leary & Cano, 2001), and alcohol problems (Murphy & O'Farrell, 1994). Hostile behaviors are related to alterations in immunological and cardiovascular systems (Ewart, Taylor, Kraemer, & Agras, 1991; Kiecolt-Glaser, McGuire, Robles, & Glaser, 2002; Malarkey, Kiecolt-Glaser, Pearl, & Glaser, 1994) making it no surprise that conflict is associated with poorer health (Burman & Margolin 1992, Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001).

Perhaps drawing the most attention of all, conflict has enjoyed a reputation as a clear risk factor for marital distress and divorce (e.g., Christensen & Walczynski, 1997; Clements, Stanley, & Markman, 2004; Gottman, 1994). Finally, marital conflict between parents is also associated with poorer parenting (see Erel & Burman, 1995) and poorer child adjustment (see Fincham, 1998; Grych & Fincham, 2001). Because of these associations, conflict is a salient topic in public policy discussions on marriage (e.g., Stanley, 2004).

Notwithstanding the preceding observations, scholars have recently suggested that conflict may be less central, or at least less capable of explaining outcomes, than our theories, research, and interventions suggest (e.g., Bradbury, Rogge, & Lawrence, 2001; Fincham, 2003). Prompting this more cautious view are three observations. First, longitudinal findings show that conflict, taken by itself, accounts for a small portion of the variability in later marital outcomes, suggesting that other factors (whether currently discovered or not) need to be considered in predicting these outcomes (see Karney & Bradbury, 1995). Second, although there is much evidence that conflict is a reliable prospective risk factor, the ability to “predict” marital outcomes from interaction is considerably less than what many think because of data set specific variance (see Heyman & Slep, 2001). Third, there occasionally appear reversal effects suggesting either inconstancy or greater complexity in the way that negative interaction affects outcomes, with Fincham and Beach (1999) noting that dimensions such as attachment and commitment may help resolve such complexities.

Stanley (2007) has argued that we are in a new stage of marital research that reflects a growing momentum toward larger meanings and deeper motivations about relationships, including a focus on constructs that are decidedly more positive (see also Stanley & Markman, 1998). Indeed, it appears to have taken some time for psychologists to realize what scholars in other disciplines have previously noted, namely, that a good marriage provides spouses with a sense of meaning in their lives (Aldous, 1996). We suggest that this momentum has set the stage for examination of transformative, rather than merely incremental, change in relationships.

Why these shifts in the field are important should be obvious. Researchers “see” most clearly what they measure, and therefore the constructs measured dominate what they talk and think about. When the conversation is dominated by a singular focus, other compelling but more nuanced stories may be missed. The growth of knowledge has also been constricted by conceptual limitations imposed by available statistical methods. Conceptual change in our understanding of marital processes will need to occur hand in hand with the development of the new statistical tools for analyzing discontinuous change processes. As Gottman, Swanson, and Swanson (2002) note, processes that unfold over a large number of iterations can produce surprising discontinuities or “jumps” in the behavior of the system. These discontinuities can take a system from one state to a qualitatively different state, resulting in a change in the order variables in the system (i.e., those variables that indicate a fundamental transition in the functioning of the system; Nowak & Vallacher, 1998). Techniques for detecting the presence of such iterative processes and the discontinuities need to be refined. We address some of these emerging approaches in considering nonlinear, dynamic systems and taxometric procedures.

In short, the seeds of change are being sown in the marital research literature. Because there is as yet no analysis of these nascent developments, there is the danger that they will not be seen as a response to a common stimulus and so will not coalesce into an additive critique of current limitations in the field. In providing such an analysis, we identify a thread that links several seemingly diverse developments and sets the stage for understanding self-regulatory, transformative processes in marriage.

The broader context within which these changes are occurring is outlined next followed by selected examples of the change. We then turn to focus squarely on iterative and transformative processes in marriage, and, in so doing address such issues as spontaneous remission of marital distress, which have received remarkably little conceptual or empirical attention from marital scholars.

No Construct is an Island

Paraphrasing Donne's classic meditation, we now consider the broader context for the developments outlined earlier. We first note four ways in which this shift in focus beyond dissatisfaction and conflict facilitates the growth of knowledge. First, it allows us to describe the interplay between conflict and other processes that may moderate or give clearer theoretical meaning to its effects. Second, it moves our attention beyond the behavior of the actors—the couples themselves— to encompass forces within the environment that affect them, a perspective emphasized by interdependence theory (Berscheid, 1999) as well as by the ecological model derived from Bronfenbrenner (1989). As Bradbury and Karney (2004) argue, to understand and help couples, we must also be prepared to address contextual processes such as poverty and racism that may set the stage for conflict or limit couples' responses in important ways. Third, the larger context of personal meaning and motivation for the actors involved becomes important. This context, in turn, enriches the theoretical framework within which research informs educational or therapeutic efforts. Fourth, it leads to an expectation of nonmonotonic and nonlinear effects. This expanded view of change may suggest additional mechanisms for understanding relationship repair – and ultimately relationship transformation.

The times they are a-changing

Accompanying the change from within the area of more clinically oriented marital work has been a broader contextual change, the emergence of relationship science (see Berscheid, 1999). In psychology, this emergence heralded spectacular growth in research on close relationships among social psychologists while also promoting existing interest in the study of family relationships among clinical and developmental psychologists. Perhaps because social psychologists focused primarily on nonmarital relationships, the interplay between social and clinical psychological literatures has been limited. As more social psychologists study marriage, however, this circumstance has begun to change. The change is most evident in regard to the construct most intensively studied in social psychological research on relationships, attachment (Hazan & Shaver, 1987), with couple therapy models emerging based on this work (see Johnson, 2004).

Concurrent with this change has been the very recent shift to focus on “health” rather than pathology. Health is more complex than illness, and we would not be the first to note that health is not the mere absence of illness. Similarly, Notarius and Markman (1993) suggested that Tolstoy got it wrong about couples and conflict in the opening lines of Anna Karenina when he wrote, “All happy families resemble one another, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” They suggest that couples are relatively nonunique when it comes to conflict (illness), and the diversity (and complexity) may well be on the more positive end (health). Stanley (2007) suggests that this may well be why more positive, meaning-related constructs have received so much less attention; they appear to be more complex, harder to conceptualize, and harder to measure. Broad dissemination of these constructs is further hindered by the substantial case that exists for the view that “bad is stronger than good” or more salient across a vast array of human experience (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001). Notwithstanding these hurdles, the widespread shift to the study of health suggests an intellectual context in which a one-dimensional focus on conflict is likely to fare poorly relative to constructs that provide greater capacity to describe and explain complex and nonlinear adaptive changes over time. Consistent with this new focus is the emphasis on “healthy” marriage in public policy (e.g., Ooms & Wilson, 2004; Stanley, 2004). Finally, the emergence of positive psychology, or the scientific study of subjective well-being and optimal human functioning, with its emphasis on more complex constructs (e.g., hope, virtue, character, see Linley, Joseph, Harrington, & Wood, 2006) has provided a propitious environment for change in the marital field.

Dylan's refrain captures poignantly the current state of play in marital research. We attempt to reflect the changing times in the next two sections knowing that any effort to do so will necessarily be incomplete. Indeed, the changes now occurring in our field may be so broad that attempts to catalogue all the elements would necessarily be doomed to fail. Our goal therefore is not to be comprehensive but to provide a sufficient sampling to make apparent an underlying thread: Couples can sometimes change without outside influences (i.e., without professional help). This is the heart of normal, marital self-regulation and the basis for transformative processes in marriage.

Exemplars of the Emerging Focus

In this section, we outline some new foci in the marital literature beginning with the recognition that there is a positive dimension in marital relationships that is distinct from the negative dimension. We follow the thread begun by this observation to increased attention on social support in marriage, and then explore the more complex self-regulatory domains of forgiveness, commitment, sacrifice, and sanctification in relationships. Running through the necessarily selective threads of research that we present, we hypothesize a single dimension that is consistent with the change we have been describing: self-regulatory mechanisms located within the dyad that provide the average couple with ways to forge deeper connection or to effect repairs of the relationship after experiencing distance and frustration. We make no claim that the ensuing research highlights are necessarily the most important or most representative of those available. They are, however, ones we know particularly well and they serve the broader purpose of this article. Their sole function here is to allow us to illustrate the underlying thread that binds together many recent developments that lead ultimately to consideration of dyadic self-transformation.

Differentiation of Positive and Negative Dimensions of Marital Quality

An important development in the effort to break free from one-dimensional thinking was the observation that marital satisfaction can be conceptualized and measured better as two separate dimensions than as one (Fincham, Beach, & Kemp-Fincham, 1997; see also Huston & Melz, 2004). Although there were previous attempts to make a similar distinction (cf. Braiker & Kelley, 1979; Johnson, White, Edwards, & Booth, 1986; Orden & Bradburn, 1968), they confounded reports of satisfaction and reports of behavior (see Fincham & Bradbury, 1987) which may account for why they never took root in the marital literature. This carving apart of what looked like one dimension allows the study not only of happy (high in positivity and low in negativity) and unhappy (low in positivity and high in negativity) spouses but also ambivalent spouses (high in positivity and in negativity) and indifferent spouses (low in positivity and in negativity), two groups that have not received attention in prior research. As predicted, data obtained to capture a two-dimensional conception of relationship satisfaction indicated that the dimensions had different correlates and accounted for unique variance in reported marital behaviors and attributions (Fincham & Linfield, 1997). More importantly, the surplus conceptual value test was met as these findings held even when marital adjustment scores were statistically controlled. Moreover, ambivalent wives differed reliably in their behaviors and attributions from indifferent wives, fitting well the theory suggested by these two dimensions (Fincham & Linfield, 1997). The distinction also opened new avenues of inquiry by introducing a new type of complexity into measurement of marital change. For instance, it would be theoretically important if happily married spouses first increased negative evaluations only (became ambivalent) before then decreasing positive evaluations and becoming distressed, as compared to a progression in which negative evaluations increased and positive evaluations decreased at the same time. Such progressions may, in turn, differ in important ways from one where there is simply a decline in positive evaluations over time.

The conceptual distinction between positive and negative raises the question of how positive behaviors exert their influence. The study of supportive behaviors within marital relationships has been illuminating in this regard. For example, observational methods have been developed to code interactions where one spouse talks about a personal issue he or she would like to change and the other is asked to respond. This work has shown that supportive spouse behavior is related to marital satisfaction and is more important than negative behavior in determining the perceived supportiveness of an interaction. Moreover, wives' supportive behavior predicts marital stress 12 months later while controlling for initial marital stress and depression (Cutrona, 1996; Davila, Bradbury, Cohan, & Tochluk, 1997). Hence, compromised conflict skills lead to greater risk of marital deterioration in the context of poor support communication (see also Carels & Baucom, 1999; Saitzyk, Floyd, & Kroll, 1997). In a similar vein, Caughlin and Huston (2002) found that the demand-withdraw pattern was unrelated to marital satisfaction in the context of high affectional expression but the two variables were inversely related in the context of average or low affectional expression. In each of these cases, assessing positivity independently of negativity provides important evidence of how the effects of negativity are moderated by the ability to maintain a positive connection.

One conclusion to be drawn from this research is that positive behaviors are essential for a correct characterization of the role of conflict in marital outcomes, suggesting that marital outcomes are not a simple linear function of marital conflict (cf. Fowers, 2001; Huston et al., 2001). In examining the exemplars we now turn to—forgiveness, commitment, sacrifice, and sanctification—one can see the influence of social psychology. In one way or another, each encompasses a type of transformation of motivation, as described by Kelley and Thibaut (1978). Because of their potential to help couples accommodate to external challenges or potentially problematic partner behavior, the constructs we now focus on can be seen as changing the mutual influence of specific partner behaviors or the growth parameters in the successive states that characterize marital dynamics unfolding over time. As such, these processes have the potential to dampen the response of a nonlinear dynamic system to perturbations caused by partner behavior or external events as well as to lead to qualitative shifts in the couple system over time.

Forgiveness

Many researchers and clinicians believe that forgiveness is the cornerstone of a successful marriage, a view that is shared by spouses themselves (Fenell, 1993). Although attempts to integrate forgiveness into broader theories of marriage hardly exist, forgiveness can be seen conceptually as falling on a dimension of positive coping responses, such as social support. The examination of forgiveness, however, clearly moves the field toward something that is more than just a positive transaction between partners. Forgiveness appears to be a relatively powerful dynamic that involves motivational transformation (McCullough, Worthington, & Rachal, 1997). It can be viewed as one example of a dyadic self-repair process with the potential to influence exchanges over time by changing the degree to which each partner's behavior serves to determine the other's response, potentially changing the course and outcome of dyadic processes. From the standpoint of understanding nonlinear dynamic processes, it might be considered a variable that moderates reactions to partner behavior (i.e., changing the mutual influence in the dynamic system created by the dyad).

Gordon, Baucom, and Snyder (2004) argue that forgiveness is important in situations where marital assumptions or relationship standards have been breached. Similarly, in contextual family therapy (e.g., Boszormenyi-Nagy & Krasner, 1986), Hargrave and Sells (1997) propose that forgiveness is important when transgressions violate partners' relational ethics and sense of justice in the marriage. Because assumptions and standards of marital relationships are threatened all too often, forgiveness may be a regular component of repair in healthy marital relationships. Suggesting its importance, forgiveness has been linked to several key constructs in the marital domain (for reviews see Fincham, Hall, & Beach, 2005). Given the salience of negative events in human relationships (Baumeister et al., 2001), it is unlikely that a stream of positive events can successfully counter a large negative event, especially if the event is traumatic. The potency of negative events necessitates repair processes that are fundamentally transformative. Otherwise, as Fincham, Beach, and Davila (2004) suggest, unresolved transgressions may spillover into future conflicts and, in turn, impede their resolution thereby putting the couple at risk for negative, downward cycles of interaction.

The emerging data suggest that forgiveness has considerable power to elucidate the process of repair in marital relationships. Further, it is a construct that provides important new opportunities for marital intervention and prevention.

Commitment and Sacrifice

The in-depth, empirical study of marital commitment began with the pioneering works of sociologist Michael Johnson (e.g., 1982) and social psychologist Caryl Rusbult (e.g., 1980). Johnson was developing a framework on the nature and correlates of commitment whereas Rusbult and colleagues developed their theory of commitment within the framework of interdependence theory (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978) leading to a more experimental approach. Until the late 90s, however, commitment generally remained on the sidelines in clinically oriented marital research. In a strong sign of the construct's arrival, there is an entire volume on the subject (Jones & Adams, 1999) and numerous papers exist on how commitment can be conceptualized and measured (Adams & Jones, 1997; Johnson, Caughlin, & Huston, 1999; Stanley & Markman, 1992).

The central distinction in commitment research is between commitment as the intrinsic desire to be with the partner in the future and commitment defined in terms of limits on personal choice. The former can be referred to as dedication (Stanley & Markman, 1992) or personal commitment (Johnson et al., 1999) and the latter as constraint commitment (Stanley & Markman, 1992). Constraints can be subdivided further into forces of moral pressure (internal) and forces that are more structural, such as external limitations resulting from options or costs (Adams & Jones, 1997; Johnson, et al., 1999). On one hand, constraints have been given little attention in our field, yet it is difficult to explain the persistence of chronically unhappy relationships without an understanding of constraints. On the other hand, when average people are asked about commitment, they are most likely to respond in terms of dedication (Stanley & Markman, 1992). Levinger (1979) posited years ago that the development of commitment to a future together had the effect of transforming two individuals into an us. In essence, dedication reflects the development of an identity of us with a future that is reinforced even as it reinforces relationship quality through such processes as accommodation and sacrifice.

Flowing directly from scholarship on commitment, and especially strongly linked conceptually to the construct of dedication, is a growing literature examining sacrifice in romantic relationships. Whitton, Stanley, and Markman (2002) note significant advances in the study of the positive role that sacrifice can play in marriage. They highlight the importance of understanding the perception (or meaning) of sacrifices, especially in light of the fact that a growing body of findings do not support the view that sacrifice is a major causes of depression and relationship dissatisfaction in women (Jack, 1991; Lerner, 1988). In the context of marriage, sacrifice refers to behavior in which one gives up some immediate personal desire to benefit the marriage or the partner (Whitton et al., 2002), reflecting the transformation from self-focus to couple focus (Wieselquist, Rusbult, Foster, & Agnew, 1999).

Van Lange and colleagues (1997) note that sacrifice is not a cost of the relationship in exchange theory terms because of the transformation of motivation that occurs within an individual (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978). Costs, by definition, represent an exchange perceived to result in a net, personal loss. For those partners who report greater willingness to sacrifice, however, the very same behavior that could represent a cost is reappraised with an emphasis on us and our future, turning it into a source of satisfaction rather than a cost (Whitton et al., 2002). Indeed, self-reports of personal satisfaction from sacrificing for one's mate are associated with both concurrent marital adjustment (Stanley & Markman, 1992) and marital adjustment over time, with attitudes about sacrifice predicting later better than earlier marital adjustment (Stanley, Whitton, Low, Clements, & Markman, 2006). Similarly Van Lange and colleagues have found that those who report more willingness to sacrifice also report greater satisfaction, commitment, and relationship persistence (e.g., Van Lange et al., 1997; Wieselquist et al., 1999). Finally, recent findings show that sacrifice attitudes and perception of personal loss are more strongly related to long-term commitment among men than women (e.g., Stanley et al, 2006; Whitton, Stanley, & Markman, in press) suggesting that, on average, healthy sacrifice is more closely linked to relationship commitment among men than among women.

Not only is the growing literature on sacrifice consistent with transformation, flowing as it does directly from the concept of transformation of motivation, but the apparent potency of sacrifice is consistent with the notion of nonlinear change. Specifically, researchers speculate that sacrifice may have a very high symbolic value with regard to commitment between partners because varying types of sacrificial behaviors, small and large, are salient in the otherwise mundane stream of experience (Stanley et al., 2006; Wieselquist et al., 1999). In other words, partners may too readily acclimate to what positives they do exchange; if so, behaviors that stand out as reflecting thoughtfulness and commitment might have more than a mere additive effect.

Sanctification

The construct of sanctification has been put forth in psychological martial research by Annette Mahoney, Ken Pargament, and colleagues (e.g., Mahoney et al., 1999). It refers to the process whereby an aspect of life is perceived by people as having divine character and significance (Pargament & Mahoney, 2005). As such, sanctification is more explicitly religious in its content than are most constructs in the marital area. It further is an illustration of embeddedness in broader, community-supported systems of meaning that are important in this discussion. In particular, to the extent that processes such as forgiveness or commitment are themselves subject to the effects of perturbations from outside or inside the marital dyadic system, it is important to consider the extent to which they are themselves regulated by broader systems of meaning. If these broader systems have sufficient potency that they can help reset or regulate the key dyadic relationship parameters that control marital homeostasis, understanding their role will be crucial in mapping out the functional system that results in marital success or failure. We return to develop this theme when we address directly the implications of iterative processes in marital relationships (see section, Nonlinear Dynamical Systems)

Parke (2001) notes that research on religion “is rarely represented in the scientific journals devoted to family issues” (p. 555). This omission is all the more remarkable given the interests and values of most people (Mahoney et al., 1999). Religious beliefs and practice warrant much greater attention because the very meaning and importance of marriage has been understood by many people, if not most, from a religious perspective (Mahoney, Pargament, Murray-Swank, & Murray-Swank, 2003). In addition, religious influences on the organization of family life as well as on family outcomes may be particularly important in some cultural contexts (Brody, Stoneman, Flor, & McCrary, 1994), highlighting the utility of assessing and including religious variables in our models of marital functioning. At the empirical level, there is a positive association between religiosity and marital stability and satisfaction. Further, three longitudinal studies indicate that religiousness predicts lower risk of divorce and divorce proneness, and not vice versa (Booth, Johnson et al., 1995; Clydesdale, 1997; Fergusson, Horwood, & Shannon, 1984). These findings suggest that something in the deep meaning structures or cultural patterns associated with religious behavior influences marital outcomes.

Mahoney, Pargament, and colleagues have greatly advanced understanding of how such meanings are related to marital quality in their research on sanctification. To examine sanctification in marital dynamics, they assessed the extent to which spouses view marriage as a manifestation of God (e.g., “God is present in my marriage,” “My marriage is influenced by God's actions in our lives.”) and has sacred qualities (e.g., holy, spiritual, see Mahoney et al., 2003). These sanctification measures are related to marital satisfaction, greater collaboration and less conflict in resolving disagreements, and greater investment in the marriage (Mahoney et al., 1999). These relationships remained after controlling for demographic variables and global markers of religiousness.

Religion has the apparent potential to help couples build marital intimacy, stimulate companionship, and perhaps offer unique cognitive and behavioral resources for couples dealing with marital stressors. Indeed, religion provides one domain in which the concept of transformation is fundamental and meaningful. There are likely others but our larger point is that few have been studied in sufficient depth to fully understand the implications for marital transformation. Regardless of one's view of the specific construct of sanctification, the thinking reflected in this line of research represents a strong movement toward incorporating both a cultural context and personal meaning into our understanding of marital functioning.

Summary and implications

Our brief summary of some current developments in marital research suggests that the intellectual climate in psychological research on marriage was changed first, by the idea that deficits alone are not enough to adequately explain marital health, and then by an increasing number of researchers who experienced dissatisfaction with the limitations of a unidimensional model of marital discord. This momentum has been driving the field in a new direction, a direction that involves identifying sources of strength and possibly transformation, and that extends well beyond conflict. Indeed, Weiss has argued for using behavioral analytic strategies, not merely for studying conflict behavior, but to learn about instances of mastery over significant challenges throughout couple development (Weiss, 2005; Weiss & Heyman, 2004). This notion is consistent with our view that the field is shifting toward understanding positive, transformative processes.

This movement we are attempting to capture here has paved the way for greater attention to complexity, resilience, and ultimately context, motivation, and meaning systems. We are suggesting that increased attention to internal dynamics and deeper meaning link seemingly disparate developments in the marital area. We believe these trends will inexorably lead the field to focus on second order constructs. It is critical, however, that such constructs be embedded in a conceptual framework that highlights the potential for self-regulatory, transformative processes within marriage, including processes by which couples change without obvious outside intervention, because such change would be of both conceptual and practical (e.g., therapy and education) significance. We explore the implications of this new perspective in the next section focusing on spontaneous remission, nonlinear dynamic systems in marriage, the possibility of nonarbitrary definitions of marital discord, and the potential for other constructs to emerge that are related to self-transformation in marital research.

The New Horizon: Self-Regulatory, Transformative Processes in Marriage

Once we focus on strengths, coping, and deeper systems of meaning, rather than conflict, we begin to ask new questions. One simple but profoundly important question is whether distressed couples invariably need external interventions such as marital education or couple therapy when they experience relationship distress. That is, one might ask whether, in the absence of some external intervention or event, couples having difficulties will inevitably experience a downward spiral leading to increasing difficulties over time and ultimately, marital misery or separation. Increased attention to motivation and self-regulation, in turn, leads us to dramatically restructure the question and ask instead: Is there an inherent capacity in many relationships for marital self-repair and relationship generated change, even in the absence of outside intervention? If so, there may be substantial implications both for those couples who receive marital therapy or premarital interventions and for those who do not because such a process would likely open a window on the very essence of transformation. Although we have efficacious marital interventions (see Baucom et al., 1998), these interventions are plagued by the problem of relapse; even successful premarital education is believed to have time limited positive effects (see Stanley, 2001). Thus a corollary question arises: Can naturally occurring marital self-repair processes be harnessed to improve existing treatments, especially the maintenance of treatment gains over time? We now address the intriguing question of spontaneous remission.

Spontaneous Remission of Marital Distress

To our knowledge, the only longitudinal data set that has been used to address the question of spontaneous remission of marital discord was the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH), analyzed by Waite and Luo (2002). Waite and Luo (2002) found that nearly two thirds (62%) of unhappily married spouses who stayed married reported that their marriages were happy five years later (and 77% of unhappily married spouses remained married). In addition, the most unhappily married spouses reported the most dramatic turnarounds: Among those who rated their marriages as very unhappy, almost 8 out of 10 who avoided divorce reported that they were happily married five years later. This study challenges a common assumption among marital researchers that marital discord does not undergo spontaneous remission, an assumption based on the lack of evidence of spontaneous remission in untreated, treatment seeking populations (see Baucom et al., 1998).

The report by Waite and Luo (2002) is, of course, subject to methodological challenges. For example, one might question the validity of their single-item measure as an index of marital impairment and dissatisfaction or the correlational nature of their data. Using a more robust set of measures and a representative data set with four time points over 12 years, Hawkins and Booth (2005) found that 16% of couples were in stable, low quality marriages in which the individuals did not do better over time than those who divorced. If Waite and Lou's analyses suggest that some couples rebound, Hawkins and Booth's suggest there are also some couples without bounce. The contrast between couples who bounce back and those who do not suggests that it is important to examine the possibility of naturally occurring self-repair processes over longer time frames and using new conceptual tools.

Self-repair processes may be similar to those already relatively well described in emerging literatures such as that on marital forgiveness. Or there may be processes that are less well understood and perhaps more deeply embedded in cultural traditions, such as might be the case for processes related to sacrifice or sanctification of marriage. Regardless of the exact nature of self-repair processes, it is important to examine other longitudinal data sets for evidence of spontaneous remission. In particular, we may learn a great deal about marital self-repair processes by contrasting the behavior of couples who stay unhappily together with those who demonstrate spontaneous remission of their distress. Such information, in turn, may be useful for interventions. If spontaneous remission proves to be a relatively common phenomenon, it will provide an important stimulus to the study of self-repair processes in distressed couples. Even if it is a rare, but non-negligible phenomenon, it may provide important clues about nonlinear change in marriage.

Nonlinear Dynamical Systems

The new intellectual landscape that we documented earlier also prompts questions about the nature of marital processes, especially the simple, linear change processes that pervade the marital literature. It seems especially conducive to theorizing that focuses on complex nonlinear dynamic processes in marriage (see Gottman et al., 2002, for an historical overview). The nonlinear dynamic view already has strong resonance with many marital and family researchers because it captures intuitions about circular processes in family systems. Mutual influence processes of the sort typically hypothesized to occur in marriages and families necessarily posit iterative patterns in which a previous partner behavior provides the raw material for a response that, in turn, will become the starting point for the partner's next behavior. As a result, even though some of the language of nonlinear dynamic systems is new for marital and family researchers (e.g., control and influence parameters, see below), the underlying ideas are not. As Gottman et al. (2002) suggest, the excitement of this approach is its potential to formalize intuition about the consequences of repetitive cycles of interaction and the sometimes unexpected consequences it reveals as systemic behavior unfolds over many iterations.

Commitment, sacrifice, and forgiveness may be viewed as factors that gain considerable predictive power from their ability to influence iterative dyadic processes. Each can be thought of as contributing to homeostatic mechanisms that protect the couple. They do so by regulating both the degree to which a negative partner behavior elicits a correspondingly negative response (i.e., regulating the mutual influence parameter) as well as the extent to which negative partner behavior produces a change in the overall view of the relationship (i.e. regulating the control variable that determines the impact of partner behavior on other outcomes). These two types of effects (influence variables and control variables) are important for nonlinear dynamics in couple interaction.

Influence Variables

The behavior of two individuals linked together by a parameter that represents the degree of influence between them can be very different from the unconstrained behavior that would be displayed by the individuals considered alone. The result of linking systems with an influence parameter has been explored in several contexts. One demonstration provided by Nowak and Vallacher (1998) used self-influencing systems that were complex in their behavior (i.e., individual, nonrepeating streams of behavior). When they linked the individuals in a single system connected by a mutual influence variable, there was a remarkable and interesting result. At a certain point, there was a dramatic transition from uncoordinated interaction (each individual's behavior is relatively independent of the other) to highly coordinated interaction. That is, as the system became more interdependent, the behavior of the system demonstrated new emergent properties that did not depend on the specific characteristics of the individual members (see p. 196). Under some settings of the influence parameter, the system became self-determining across a wide range of external influences (i.e., impervious to outside influence).

This type of demonstration shows how iterative processes unfolding over many repetitions may lead inevitably to both partners engaging in problematic behavior even if neither was initially so inclined. By decreasing the degree of influence, the effect of negative partner behavior may be decreased, allowing some individuals to show little long-term disruption in their view of the relationship even after a serious initial perturbation. Factors such as commitment, sacrifice, and forgiveness may serve their protective function, in part, by decreasing the influence of negative partner behavior across repetitive cycles (e.g., by reducing tit-for-tat responding) and so dampening the impact of negative partner behavior on the relationship. In dyads with fewer protective factors, increasing disruption and negativity may be occasioned by a wide range of initial perturbations.

Control Variables

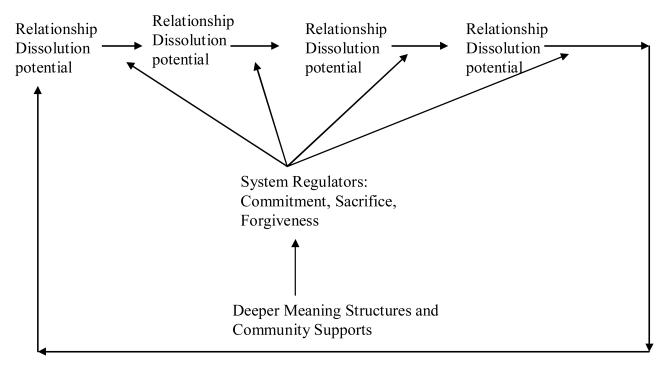

Control variables regulate changes in the internal representation of the relationship and thereby affect the rate of growth in key relationship outcomes across iterations. A similar idea is found in interaction effects in which the effect of one variable changes as a function of a second variable. The second variable is acting as a control variable for the effect of the first variable. Each of the variables we have reviewed also has the potential to play a role in regulating the changes in the internal representation of the relationship that occur across iterations as individuals think about their relationship over time. The logic of iterative processes can be used to illustrate the importance of control variables for understanding the internal dynamics of relationships. For illustrative purposes consider the construct of relationship dissolution potential, an outcome of applied significance that might be taken to reflect the moment to moment fluctuations in tendency toward relationship dissolution (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Influence of System Regulators Across Iteration

Using a given level of relationship dissolution potential as the starting point, the output of an equation involving the system control variable (e.g., commitment, sacrifice, forgiveness) provides the next starting point for each subsequent iteration. From this relatively simple starting point, one can model the way in which relationship dissolution potential might change over time following an initial perturbation in the system. The model suggests that each successive relationship dissolution potential value is both the result of the prior relationship dissolution potential value as well as a primary input into one's future relationship dissolution potential value. Simple iterative equations can be used to demonstrate a range of circumstances in which a particular function, relationship dissolution potentialn = f(relationship dissolution potentialn-1, forgiveness), may lead to a steady state outcome at some levels of the control variable, but multiple values or even a chaotic series of values for other levels of the control variable. For example, a particular level of forgiveness in a relationship may be sufficient to allow the relationship to survive perturbations introduced by partner behavior, bouncing around in the aftermath of a transgression but eventually returning to the relationships original steady state value. In contrast, a lower level of forgiveness may produce a continuing alternation between values of relationship dissolution potential or perhaps the emergence of a steady state value that exceeds the point needed to overcome external constraints and initiate separation or divorce. Although we focused on relationship dissolution potential, the same logic can be used to examine a range of relationship outcome variables.

Having briefly considered influence and control variables it can be noted that variables such as commitment, sacrifice, and forgiveness play a dual role. They not only serve as influence variables that regulate the circular processes linking partner behaviors but also serve as control variables that regulate the flow of internal mental states. As a result, they ultimately lead to shifts in patterns of intentional behavior and willingness to engage in various forms of relationship enhancing or relationship diminishing behavior.

As can be seen in this simple illustration, the power of variables such as commitment, sacrifice, and forgiveness comes not from their ability to dramatically alter a particular transition during a single iteration. Rather, their power comes from their potential to influence each turn – to some degree – as an iterative process unfolds over time. When events or partner transgressions cause some perturbation in the system leading to contemplation of relationship dissolution, the system regulators (commitment, sacrifice, and forgiveness among others) have the potential to influence the transition from one state to the next, leading the system back to a steady state, assuming the perturbation was within the capacity of the system to handle.

In addition to the introduction of complexity into the domain of marital and family research, and their potential to tie intraindividual changes to dyadic interaction, the constructs of commitment, sacrifice, and forgiveness also illustrate the potential for system influence and control variables to be embedded in larger meaning contexts as well as in larger social contexts with important effects on the unfolding of iterative processes over time. As our brief review of the construct of sanctification indicated, individuals often have deep connections to particular systems of meaning that in turn have implications for potential control and influence variables such as commitment, sacrifice, and forgiveness. When individuals are embedded in systems that support these patterns of response, they are likely to be able to reset or initiate protective behaviors when they are needed, making these patterns of response more available and more readily sustained across iterations. An example of this pattern would be a wife who views her marriage as sanctified and consequently believes that sacrifice for the relationship is a rewarding opportunity. In this case, the meaning system within which willingness to sacrifice is embedded might reinforce and sustain an initial willingness to sacrifice even if it suffered a temporary reduction because of partner behavior or external circumstances. Sacrificial behaviors, in turn, may become a particularly salient and important symbol of an ongoing level of commitment (as the controlling variable) that conveys the intention to reacquire a positive equilibrium, reinforcing trust when it is most needed (regarding linkage to trust, see Stanley et al., 2006; Wieselquist et al., 1999).

The recent upsurge in the use of computer simulations of dynamical systems in disparate areas of science may prove to be particularly relevant to marital researchers because such simulations can be used to explore the behavior of complex dyadic systems over time. In particular, simulations of dynamical systems can provide evidence: (a) that dyadic systems can have emergent properties, (b) that distinct subpopulations can diverge starkly despite similarity in initial starting points, (c) that some problematic relationship dynamics can become self-perpetuating or alternatively self-healing, (d) that dyadic systems can be disordered in the absence of disorder at the individual level, and (e) that some simple system characteristics may prevent the emergence of systemic disorder. One interesting effect of nonlinear dynamics is the potential for dynamic processes to occasion self-transformation of couples in the absence of outside intervention. Linked to empirical examination of particular dyadic systems, mathematical models have the potential to be quite persuasive (again, see Gottman et al., 2002, for an example). We turn to briefly consider one implication of this perspective before illustrating the kind of marital self-transformation framework that it suggests.

Nonarbitrary Definitions of Distress and Marital Discord

Self-transformation and internal dynamics in marital relationships also create the potential for new, nonarbitrary definitions of marital discord as well as nonarbitrary premarital recommendations regarding needed protective factors. The potential for discontinuity and nonlinear change suggests that there may be qualitative and not merely quantitative shifts as one moves from relatively satisfied couples, or even dissatisfied couples who have the potential to recover spontaneously, to those who are locked into a self-perpetuating cycle of marital discord. As a consequence, some dyads may diverge from other similar seeming dyads over multiple iterations of interaction and eventually show evidence that they are in a qualitatively different state.

Taxometrics (Waller & Meehl, 1998) is an approach that may help us identify just such qualitative shifts as well as better investigate the type of variables that may predict them. Taxometric investigation is designed to see whether a particular dimension changes gradually and continuously, or alternatively if it has a nonarbitrary boundary at which point it becomes qualitatively different. It can also provide evidence that such categories are not arbitrary and do not merely capture outliers from the normal population.

If spontaneous remission of marital discord and/or discontinuities between discordant and nondiscordant married couples are identified, this suggests the potential for a nonarbitrary distinction between marital distress and marital discord. Distress would be a common state affecting many couples at some point during their marriage, but the term maritally discordant might be reserved for those couples in which there was a break down in self-repair processes and little potential for self-generated recovery. If so, we might find that even theorizing focused on marital dissatisfaction and conflict becomes richer as a result of the emerging intellectual climate in the marital area. Supporting the possibility of a nonarbitrary distinction between discordant and nondiscordant couples, Beach et al. (2005) found evidence of a discontinuity in marital satisfaction scores such that approximately 20% of a community sample experienced marriage in a way that was qualitatively, not merely quantitatively, different from their peers.

To the extent that discontinuities in marriage are replicated across samples and measures, this will lend support to the current trend in the literature toward complexity and transformation. That is, if some couples diverge from other couples over time, leading them to look less like their nondiscordant peers, and if this occurs because of differences in key control and influence variables, it strongly suggests the presence of iterative processes and the potential for analysis from a nonlinear dynamic perspective.

Example of a marital self-transformation framework for understanding dynamic processes in marriage

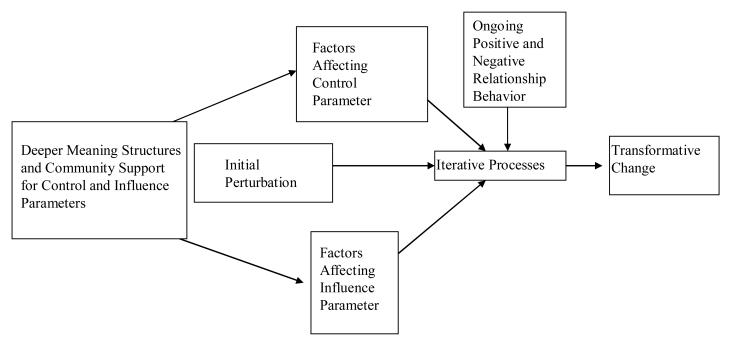

What kind of new model lingers on the horizon of marital research? As the preceding comments suggest, the marital area is moving toward models that embrace complexity, motivation, dynamic processes, and the importance of marital self-transformation. We offer an example of a rudimentary heuristic framework in Figure 2 with the proviso that it should be interpreted as an attempt to capture the broad new categories of effects available to marital researchers rather to serve as a specific model of marital outcomes. In particular, it is meant to illustrate the interconnection of dyadic level influence and internal control processes and not to supplant the constructs that have been advanced in existing models of marital change.

Figure 2.

Framework for understanding transformative processes in marriage

It can be seen that the framework shown in Figure 2 begins by acknowledging deep meaning structures and community support. These factors are meant to capture the role of the larger context within which dyadic influence and control variables are often embedded. In a related vein, the broad constructs of negative dyadic and positive dyadic behavior are meant to recognize the relative independence of positive and negative processes in dyadic relationships as well as their embeddedness within socioeconomic, community level, and societal processes. The newer element of the model is its focus on the role of variables that change the degree of mutual influence between partners and that control the unfolding of iterative processes within an individual over time. These influence and control variables also capture the self-organizing principle of relationship goals and so respond to the challenge of better understanding the role of emergent goals that characterize couples locked in destructive interactions (see Fincham & Beach, 1999).

Figure 2 suggests that initial perturbations may be prompted by external stressors or by partner behavior. Once underway, a perturbation may influence positive and negative marital processes and may become the input for the ongoing iterative transactions that unfold moment to moment within an individual as well as between partners. For example, if the initial perturbation is a particularly bad argument, there may be many reminders of the disagreement for each partner over the course of a week, and each reminder may produce another cycle of interpretation allowing the control variable to operate. Similarly, many of the reminders may prompt dyadic interactions providing an occasion for the influence parameter to operate. For couples high in control parameters and (low) in influence parameters because of variables such as commitment, sacrifice, and forgiveness, the overall view of the relationship may be relatively constant, resulting in a high likelihood of accommodative or repair processes in response to negative partner behavior. As a consequence, such couples may display a relatively stable set point for their view of the relationship. For couples lower in control and higher in influence parameters, however, very different processes may unfold over time leading to lower trust in the relationship, weaker accommodative tendencies, and fewer repair processes. Formalizing these differences in the manner that has been accomplished in other areas of nonlinear dynamic science may reveal interesting and unanticipated couple differences as well as suggesting new directions for intervention, maintenance of gains, and prevention of marital discord.

The framework also indicates that iterative processes may give rise to transformative change. This is the unfulfilled promise of the framework and represents an area of important future research in the marital area. Transformative change would be discontinuous positive or negative change following an iterative process and would lead a couple to function in an entirely different manner than they did before. On the negative side, for example, transformative change would be captured by a couple permanently moving from very little divorce potential to a separated or divorced status. On the positive side, transformative change might be captured by a couple who, confronted with a relationship difficulty, find that they emerge more secure in their relationship and more mutually trusting of each other than they were before (i.e., with a substantially enhanced view of the relationship). As a consequence their relationship might function differently than it did before they overcame the challenge together.

This framework captures insights from several models and builds upon them (e.g., Gottman, 1994; Karney & Bradbury, 1995; Rusbult et al., 2003) by suggesting that even couples with good marital skills may fall victim to destructive marital patterns if they do not have methods for self-repair. Without methods for changing negative processes over time, or for changing direction once negative interactions begin, even the best marital skills for dealing with conflict may provide couples with an insufficient basis for long-term marital satisfaction. The framework would seem to have considerable potential to help us understand the impact of forgiveness (a transformation of motivation), commitment (a powerful influence on motivation), valuing sacrifice (a potent means of shifting the cost/reward ratio and so influencing motivation), and sanctification (tying marital behavior to a broader motivational system). More importantly, it provides the flexibility to suggest a range of new interventions and new directions for research and is consistent with increased interest in other areas that have identified self-transformative change processes (e.g., post-traumatic growth, Tedeschi, & Calhoun, 2004).

Some further implications for research and practice

Self-regulatory transformative processes and the potential for dramatic improvement and growth even in the context of seriously disturbed relationships suggests that important and potentially powerful marital change processes have yet to be well explicated. Even as we continue to explore the power of forgiveness, sacrifice, and commitment to account for change in marriage as well as to maintain gains over time, it appears likely that the field will move toward new constructs that capture more of the potential power of sudden and discontinuous change in marital behavior. In this context, there is likely to be a focus on identification of new control variables and new variables that change mutual influence parameters in addition to already identified positive and negative processes that contribute to marital change. At the same time, better statistical methods for recognizing discontinuity and points of discontinuity in the effect of control variables will be increasingly important.

To the extent that key factors changing degree of mutual influence and control variables such as commitment, sacrifice, and forgiveness can be better defined and delineated, development of self-repair and perhaps even self-transformation modules in prevention programs become important. Such strategies may help those involved in marital prevention and intervention make better use of natural relationship recovery processes or to strengthen them if they have been weakened or damaged. In some cases, such a shift in the field may suggest the value of less intervention rather than more intervention. If so, the emergence of marital self-transformation as a topic of study may coincide with a profound self-transformation of marital intervention and marital research as well.

Conclusion

We have traversed a great deal of territory in this article. Beginning with a central construct in the marital literature, conflict, we documented its move from center stage and outlined how a broader canvas could paint a richer picture of marriage. A brief sampling of new foci in the marital area such as forgiveness, sacrifice, and sanctification made apparent an underlying theme, transformative processes in marriage. The implications of self-regulatory transformations in marriage are profound, and we considered the possibility that some marital processes have the potential to produce more than incremental, linear change. In particular, if dyadic processes are iterative, they may produce unexpected and potentially discontinuous change in marital outcomes. Understanding the nature of these iterative processes, the key control and influence parameters that govern their unfolding, and the points at which discontinuities emerge, has the potential to help us understand spontaneous remission of marital discord, harnessing them has the potential to provide powerful new methods for protecting or improving marital relationships. The new horizon in marital research appears every bit as exciting as any that has come before.

We did not extend these analyses to other dyadic processes in families such as parenting, or broader processes such as triadic interactions, or the influence of community context. It is hopefully clear, however, that these domains are subject to very similar analyses and that similar conclusions are likely to be forthcoming for many of the specific areas of interest to family researchers. One of the attractions of the current analysis is that it points toward the potential for higher level integration across subsystems in families.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful and helpful input on this paper. Preparation of this manuscript was generously supported by a grant from the Administration for Children and Families to the first author, a grant from the John Templeton Foundation to the first and third authors, and grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (5-RO1-MH35525-12) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1R01HD48780-1A1) to the second author and colleague Howard Markman.

Contributor Information

Frank D. Fincham, Florida State University

Scott M. Stanley, University of Denver

Steven R.H. Beach, University of Georgia

References

- Adams JM, Jones WH. The conceptualization of marital commitment: An integrative analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:1177–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Aldous J. Family careers: Rethinking the developmental perspective. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Shoham DH, Mueser KT, Daiuto AD, Stickle TR. Empirically supported couple and family interventions for marital distress and adult mental health problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:53–88. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, Vohs KD. Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology. 2001;5:323–370. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Wamboldt M, Kaslow NJ, Heyman RE, Reiss D. Describing relationship problems in DSM-V: Toward better guidance for research and clinical practice. Journal of Family Psychology. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.3.359. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E. The greening of relationship science. American Psychologist. 1999;54:260–266. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.4.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Shantinah SD. The couples coping enhancement training (CCET): A new approach to prevention of marital distress based upon stress and coping. Family Relations. 2004;53:477–484. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Crouter AC, Clements M, editors. Couples in conflict. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Johnson DR, Branaman A, Sica A. Belief and behavior: Does religion matter in today's marriage? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:661–671. [Google Scholar]

- Boszormenyi-Nagy I, Krasner B. Between give and take: A clinical guide to contextual therapy. Brunner/Mazel; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Karney BR. Understanding and altering the longitudinal course of marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:862–879. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, Rogge R, Lawrence E. Reconsidering the role of conflict in marriage. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, Clements M, editors. Couples in conflict. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 59–81. [Google Scholar]

- Braiker HB, Kelley HH. Conflict in the development of close relationships. In: Burgess RL, Huston TL, editors. Social exchange in developing relationships. Academic; New York: 1979. pp. 135–168. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Stoneman Z, Flor D, McCrary C. Religion's role in organizing family relationships: Family process in rural, two-parent African American families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:878–888. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. Annals of Child Development. 1989;6:187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Burman B, Margolin G. Analysis of the association between marital relationships and health problems: An interactional perspective. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:39–63. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carels RA, Baucom DH. Support in marriage: Factors associated with on-line perceptions of support helpfulness. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Walczynski P. Conflict and satisfaction in couples. In: Sternberg RJ, Hojjat M, editors. Satisfaction in close relationships. Guilford Press; New York: 1997. pp. 249–274. [Google Scholar]

- Clements ML, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Before they said “I do”: Discriminating among marital outcomes over 13 years based on premarital data. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:613–626. [Google Scholar]

- Clydesdale TT. Family behaviors among early U.S. baby boomers: Exploring the effects of religion and income change, 1965-1982. Social Forces. 1997;76:605–635. [Google Scholar]

- Caughlin JP, Huston TL. A contextual analysis of the association between demand/withdraw and marital satisfaction. Personal Relationships. 2002;9:95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona C. Social support in couples. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Bradbury TN, Cohan CL, Tochluk S. Marital functioning and depressive symptoms: Evidence for a stress generation model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:849–861. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.4.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erel O, Burman B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:108–132. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewart CK, Taylor CB, Kraemer HC, Agras WS. High blood pressure and marital discord: Not being nasty matters more than being nice. Health Psychology. 1991;103:155–63. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.3.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenell D. Characteristics of long-term first marriages. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 1993;15:446–460. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Shannon FT. A proportional hazards model of family breakdown. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1984;46:539–549. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD. Child development and marital relations. Child Development. 1998;69:543–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD. The kiss of the porcupines: From attributing responsibility to forgiving. Personal Relationships. 2000;7:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD. Marital conflict: Correlates, structure and context. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SRH. Conflict in marriage: Implications for working with couples. Annual Review of Psychology. 1999;50:47–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SR, Davila J. Forgiveness and conflict resolution in marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:72–81. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SR, Kemp-Fincham SI. Marital quality: A new theoretical perspective. In: Sternberg RJ, Hojjat M, editors. Satisfaction in close relationships. Guilford Press; New York: 1997. pp. 275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Bradbury TN. The assessment of marital quality: A reevaluation. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1987;49:797–809. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Hall JH, Beach SRH. 'Til lack of forgiveness doth us part: Forgiveness in marriage. In: Worthington EL, editor. Handbook of forgiveness. Wiley; New York: 2005. pp. 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Linfield KJ. A new look at marital quality: Can spouses feel positive and negative about their marriage? Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:489–502. [Google Scholar]

- Fowers BJ. The limits of a technical concept of a good marriage: Examining the role of virtues in communication skills. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2001;27:327–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2001.tb00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KC, Baucom DH, Snyder DK. An integrative intervention for promoting recovery from extramarital affairs. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy. 2004;30:213–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman J. What predicts divorce? The relationship between marital process and marital outcomes. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Swanson C, Swanson K. A general systems theory of marriage: Nonlinear difference equation modeling of marital interaction. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6:326–340. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD, editors. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and applications. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hargrave TD, Sells JN. The development of a forgiveness scale. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1997;23:41–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1997.tb00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins DN, Booth A. Unhappily ever after: Effects of long-term, low-quality marriages on well-being. Social Forces. 2005;84:445–465. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton TB, Pratt EL. The effects of religious homogamy on marital satisfaction and stability. Journal of Family Issues. 1990;11:191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, Slep AM. The hazards of predicting divorce without cross validation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:473–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, Caughlin JP, Houts RM, Smith SE, George LJ. The connubial crucible: Newlywed years as predictors of marital delight, distress, and divorce. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:237–252. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston TL, Chorost AF. Behavioral buffers on the effect of negativity on marital satisfaction: A longitudinal study. Personal Relationships. 1994;1:223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Huston T, Melz H. The case for (promoting) marriage: The devil is in the details. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:943–958. [Google Scholar]

- Jack DC. Silencing the self: Women and depression. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins KW. Religion and families. In: Bahr SJ, editor. Family research: A sixty-year review,1930-1990. Vol. 1. Lexington Books; New York: 1992. pp. 235–288. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. The social and cognitive features of the dissolution of commitment to relationships. In: Duck S, editor. Personal relationships: Dissolving personal relationships. Academic Press; New York: 1982. pp. 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Caughlin JP, Huston TL. The tripartite nature of marital commitment: Personal, moral, and structural reasons to stay married. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:160–177. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DR, White LK, Edwards JN, Booth A. Dimensions of marital quality: Toward methodological and conceptual refinement. Journal of Family Issues. 1986;7:31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. The practice of emotionally focused marital therapy creating connection. Routledge; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jones W, Adams J. Handbook of interpersonal commitment and relationship stability. Plenum; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Contextual influences on marriage: Implications for policy and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH, Thibaut JW. Interpersonal Relations: A theory of interdependence. Wiley; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A, Fincham FD, Beach SRH. Emerging perspectives on couple communication. In: Greene JO, Burlson BR, editors. Handbook of communication and social interaction skills. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 723–752. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF, Glaser R. Psychoneuroimmunology: psychological influences on immune function and health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:537–47. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerner K, Jacobson NJ. Emotion and behavior in couple therapy. In: Johnson SM, Greenberg LS, editors. The heart of the matter: Perspectives on emotion in marital therapy. Brunner/Mazel; New York: 1994. pp. 207–226. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner HG. Women in therapy. Aronson; Northvale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Levinger G. A social exchange view on the dissolution of pair relationships. In: Burgess RL, Huston TL, editors. Social exchange in developing relationships. Academic Press; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Linley P, Joseph S, Harrington S, Wood A. Positive psychology: Past, present, and (possible) future. Journal of Positive Psychology. 2006;1:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Pargament KI, Jewell T, Swank AB, Scott E, Emery E, Rye M. Marriage and the spiritual realm: The role of proximal and distal religious constructs in marital functioning. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Pargament KI, Murray-Swank A, Murray-Swank N. Religion and the sanctification of family relationships. Review of Religious Research. 2003;40:220–236. [Google Scholar]

- Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Pearl D, Glaser R. Hostile behavior during marital conflict alters pituitary and adrenal hormones. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1994;56:41–51. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199401000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman HJ, Renick MJ, Floyd F, Stanley S, Clements M. Preventing marital distress through communication and conflict management training: A four and five year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;62:70–77. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Worthington EL, Jr., Rachal KC. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:321–336. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, O'Farrell TJ. Factors associated with marital aggression in male alcoholics. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:321–35. [Google Scholar]

- Notarius CI, Markman H. We can work it out: Making sense of marital conflict. Putnam; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak A, Vallacher RA. Dynamical social psychology. Guilford; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary KD, Cano A. Marital discord and partner abuse: Correlates and causes of depression. In: Beach SRH, editor. Marital and family processes in depression. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Ooms TJ, Wilson PC. The challenges of offering couples and marriage education to low income couples. Family Relations. 2004;53:440–446. [Google Scholar]

- Orden SR, Bradburn NM. Dimensions of marriage happiness. American Journal of Sociology. 1968;73:715–731. doi: 10.1086/224565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke R. Introduction to the special section on families and religion: A call for a recommitment by researchers, practitioners, and policymakers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:555–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. Guilford Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Mahoney A. Sacred matters: Sanctification as vital topic for the psychology of religion. International Journal of the Psychology of Religion. 2005;15:179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Pasch LA, Bradbury TN. Social support, conflict, and the development of marital dysfunction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:219–230. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE. Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1980;16:172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE, Zembrodt IM, Gunn LK. Exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect: Responses to dissatisfaction in romantic involvement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1982;43:1230–1242. [Google Scholar]

- Saitzyk AR, Floyd FJ, Kroll AB. Sequential analysis of autonomy-interdependence and affiliation-disaffiliation in couples' social support interactions. Personal Relationships. 1997;4:341–360. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM. Testimony on healthy marriage before the committee on Finance, Subcommittee on Social Security and Family Policy, U.S. Senate. Washington, DC: May 5, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM. Assessing couple and marital relationships: Beyond form and toward a deeper knowledge of function. In: Hofferth S, Casper L, editors. Handbook of measurement issues in family research. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2007. pp. 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Blumberg SL, Markman HJ. Helping couples fight for their marriages: The PREP approach. In: Berger R, Hannah M, editors. Handbook of preventive approaches in couple therapy. Brunner/Mazel; New York: 1999. pp. 279–303. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Assessing commitment in personal relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1992;54:595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Acting on what we know: The hope of prevention. In: Ooms T, editor. Strategies to strengthen marriage: What we know, what we need to know. Family Impact Seminar; Washington DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ, Whitton S. Communication, conflict, and commitment: Insights on the foundations of relationship success from a national survey. Family Process. 2002;41:659–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]