Abstract

Background

Cachexia is a devastating syndrome of body wasting that worsens quality of life and survival for patients suffering from diseases such as cancer, chronic kidney disease and chronic heart failure. Successful treatments have been elusive in humans, leaving a clear need for the development of new treatment compounds. Animal models of cachexia are able to recapitulate the clinical findings from human disease and have provided a much-needed means of testing the efficacy of prospective therapies.

Objective

This review focuses on animal models of cachexia caused by cancer, chronic heart failure and chronic kidney disease, including the features of these models, their implementation, and commonly-followed outcome measures.

Conclusion

Given a dire clinical need for effective treatments of cachexia, animal models will continue a vital role in assessing the efficacy and safety of potential treatments prior to testing in humans. Also important in the future will be the use of animal models to assess the durability of effect from anti-cachexia treatments and their effect on prognosis of the underlying disease states.

1. Introduction

Cachexia is a wasting disease that is associated with and worsens the course of multiple underlying disease processes, including cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic heart failure, AIDS and other chronic diseases [1]. Each of these diseases produces clinical symptoms that are strikingly similar, given the differences in underlying etiology [2,3]. These similarities include increased energy expenditure, loss of lean body mass and fat mass, and a decrease in appetite despite increased energy needs. Partly because of a lack of successful treatment, there is much interest in the development of successful compounds to reverse the energy imbalance, and potentially improve quality of life in these settings. The importance of research into treatments for cachexia is further emphasized by the potential to improve the underlying disease state and survival outcomes via resolution of cachexia.

Despite the gravity of cachexia as a disease process, few large-scale human trials have been conducted to evaluate compounds as potential treatments for cachexia. This is partly because of the wide heterogeneity of presentations from any given underlying disease, which increases the expense of such trials by necessitating large enrollment targets to achieve adequate power. Because of the difficulties in generating clinical trials for cachexia, well-characterized animal models are needed now more than ever to demonstrate efficacy of prospective treatments and to continue to explore etiologies of disease, potentially identifying new therapeutic targets.

This review will focus on multiple rodent models designed to mimic specific underlying human diseases associated with cachexia, including cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic heart failure, and radiation-associated anorexia. As we will see, of chief importance in each of these models is the inclusion of endpoints important to clinical outcomes. The most important of these endpoints relate to food intake, weight gain/loss and changes in body composition. We will further address challenges associated with each of these models—including animal welfare concerns—as well as areas of research that may help to address some of these challenges.

2. Inflammatory models of anorexia

Much of our understanding of the pathophysiology of disease-associated cachexia has its roots in longstanding observations of animal responses to acute inflammation. Animals that are injected with lipopolysaccaride (LPS, bacterial endotoxin [4–7]) or specific inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α or IL-1β [8–12] exhibit an intense decrease in food intake and increase in resting energy expenditure as seen in disease-associated cachexia. Following a single injection of inflammatory agents in the periphery or via intracerebroventricular cannula, animals exhibit a decrease in food intake by 40–50% over a 12 hour period, before returning to baseline food-seeking behavior (or even above baseline) by 24 hours after injection. Repeated injections or prolonged infusions gradually result in a tolerance to the inflammatory stimulus and gradual return to baseline despite repeated exposures.[7,13]

The anorexic response to inflammation has been used to provide early glimpses into the efficacy of some compounds that have been shown to ameliorate this anorexic response.[4–6,12] Nevertheless, the rapid onset of anorexia using these intense inflammatory models of anorexia and their short-term duration of effect detract from their relevance as models to assess the clinical efficacy of prospective treatments for cachexia of chronic disease. Instead, the vast majority of animal models of cachexia focus on the underlying disease causing symptoms of cachexia.

3. Cancer Cachexia

3.1. Pathophysiology of animal models

Cancer is the underlying disease process that has been best studied for its association with cachexia. This is not surprising given that cancer cachexia affects up to 80 percent of patients of certain types of cancer [14]. The presence of cachexia is associated with a worsened prognosis and contributes to up to 20% of cancer deaths [14,15]. In humans, multiple solid tumors are associated with cachexia, which can be a result of both cachexia-inducing factors as well as the inflammatory process that accompanies the tumor [16–18].

Animal models used to simulate the process in humans have predominantly utlilized implanted tumor cell lines, such as Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) [5,6,19–23], colorectal tumors [24–26], syngenic sarcomas [6,27–31], and other types of stable, cachectogenic neoplasms. These cell lines are implanted subcutaneously into experimental animals and are allowed to grow to a particular burden at which point they cause symptoms of cachexia. The implanted cell lines do not metastasize significantly—a key difference from cachexia-causing neoplasms in humans—but implanted tumors have been demonstrated to be similar in many other ways to cachexia-causing neoplasms in humans. With respect to etiology of cachexia, the commonly-used tumor lines induce cachexia through release of cachexia-inducing factors and stimulation of host-tumor interactions. Many of these implanted tumor cells express or induce inflammatory cytokines or prostaglandins [32–35]. In this way, these tumors mimic cancer cachexia in humans.

Similarly, implanted tumor models have been reported to result in key features of cachexia, including anorexia, weight loss, loss of lean and fat mass and increased energy expenditure [5,6]. These features are discussed in further detail below in the section on Endpoints. Choice of a given tumor cell line as a model for cachexia must therefore be influenced by features of cachexia known to be caused by that cell line in conjunction with the endpoints that will be followed to test the efficacy of a prospective compound. Demonstration of a compound’s efficacy in attenuating multiple features of cachexia portends well for the generalizeablity of the treatment to human disease and potentially to cachexia due to other underlying disease states that may share the same pathophysiologic underpinnings. Nevertheless, demonstration of treatment efficacy for an isolated symptom of cachexia such as in alleviating anorexia may have important implications for patient quality of life and warrant further investigation regarding overall outcomes.

3.2. Basic protocol

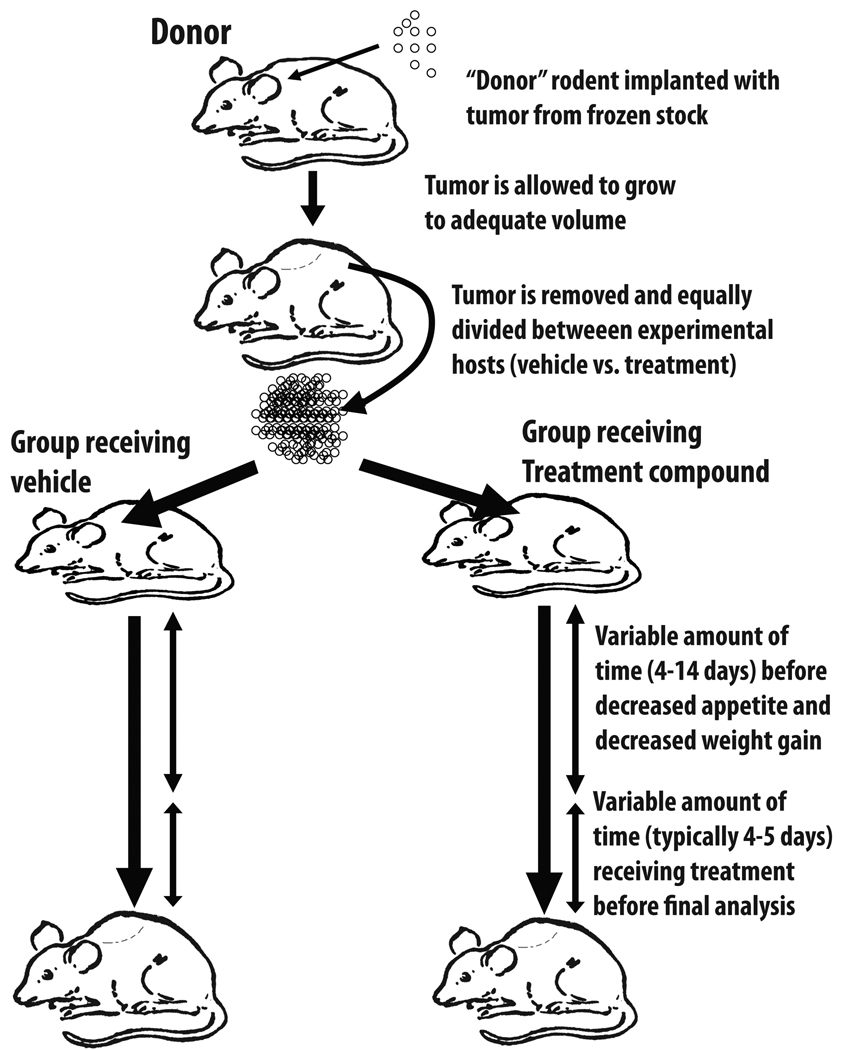

Although tumors may vary in the severity of their symptoms of cachexia and in the species that can be used for a particular model of cachexia, the most frequently-used models employ a similar basic protocol. The preferred technique involves the use of a “donor” animal to grow up tumor tissue prior to implantation into experimental animals. Use of a donor as described below helps to insure even distribution of viable tumor cells into animals randomized to receive the treatment compound or placebo, eliminating variations in tumor viability that may be noted when tumor cells are taken from frozen storage. Alternatively, tumor cells from cell culture or frozen stock are implanted directly into experimental animals.

When using a donor, the basic protocol involves the animal being sedated and receiving two small bilateral incisions in the skin overlying the upper-limb or lower-limb flank. The subcutaneous tissue is separated with hemostats to create a small pocket. Tumor cells procured from cell culture or frozen stocks are placed into this subcutaneous space of the donor animal (Figure 1). The wound is sutured or stapled and the animal is typically housed individually to prevent other experimental animals from re-opening the wound. The donor tumor is then allowed to grow to an adequate size over 10–14 days before being removed and is then split into several 0.1–0.3 g alloquots that are placed into groups of experimental animals. Sham-treated experimental animals receive an implantation of non-malignant material such as muscle cells or saline.

Figure 1.

Tumor implantation to produce cancer cachexia. Tumor cells from tissue culture are initially implanted in a donor mouse/rat prior and grown up prior to dividing between compound- and vehicle-treated animals. This approach better insures equal division of tumor cells between treatment groups.

Treatment with the prospective compound is usually initiated once the tumor has grown to the point of producing symptoms of cachexia, though occasionally treatment is begun soon after tumor implantation [26]. Depending on the tumor cell line, implanted tumor volume, and species, the tumor burden producing significant cachexia occurs 4–14 days after initial implantation. This tumor burden marks when treatment efficacy can first be demonstrated; however, it also limits the length of treatment, as worsening symptoms of cachexia raise concern for the animal’s wellbeing. Weight loss can exceed 25% of body weight and the tumors used in these protocols can reach more than 1 cm3 and have the potential to ulcerate. Detailed surveillance protocols to assess for animal morbidity are thus imperative to protect against moribund animals. These surveillance protocols involve regular assessment of animals for signs of distress, including physical appearance and behavioral patterns and the euthanizing of animals with excess morbidity. These important ethical safeguards ultimately limit the length of time that treatment experiments can last.

Thus, the therapeutic window of time for testing treatments in models of cancer cachexia is begins when appetite is first affected and ends when morbidity worsens. Compounds are thus typically administered over a 4–5 day period and are given via injection, ICV administration or oral dosing. The short time frame of treatment is unfortunate for several reasons: 1) it necessitates rapid action of the treatment compound, 2) it requires a substantial treatment effect to demonstrate improvements in endpoints after relatively brief treatment, 3) it is less likely to identify tolerance that the animal may develop to the treatment compound, 4) it does not allow evaluation of the treatment compound on the severity of the underlying disease. Nevertheless, this short time frame of treatment improves the feasibility of multiple short intervention experiments and provides a rigorous test of a compound’s efficacy. This protocol has thus been used with multiple compounds to demonstrate improvements in multiple clinically-important endpoints as outlined below.

3.3. Endpoints followed

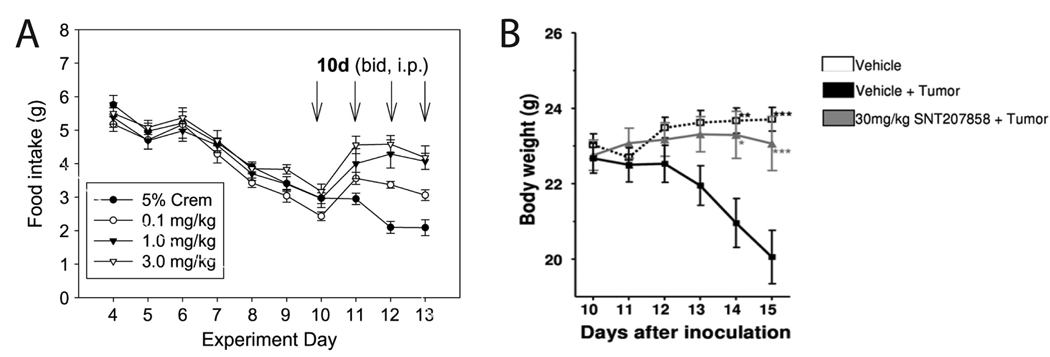

Chief among the features of cachexia used to evaluate in animal models is anorexia. Depending on the model used, this decrease in food intake occurs following 4–14 days of tumor burden, resulting in at first a minor decrease in food intake before exhibiting a severe decrease in food intake shortly thereafter (Figure 2A [23]). The timing has a variable dependence on tumor size: in the Yoshida model, tumors are often quite sizable before anorexia is noted [36–38], whereas in the MAC16 tumor model, the tumor need only be 1% of the body weight [39,40]. In Lewis Lung Carcinoma model, the decrease in food intake usually occurs at 4–10 days of tumor burden, and the severe decrease occurs at approximately 14 days after implantation.

Figure 2.

Changes in food intake and body weight in tumor-bearing animals. A. Mice implanted with Lewis Lung Carcinoma exhibited gradual decrease in food intake starting 4 days after tumor implantation. This decrease in food intake was ameliorated in a dose-dependant manner during 4 days of treatment with a melanocortin antagonist. (Used by permission from reference [23].) B. Mice implanted with C26 adenocarcinoma exhibited weight loss starting 12 days after tumor implantion. This weight loss was blocked via oral treatment with a melanocortin antagonist starting the day after tumor implantation. (Reproduced from Weyermann P et al. Orally available selective melanocortin-4 receptor antagonists stimulate food intake and reduce cancer-induced cachexia in mice. PLoS One 2009;4:e4774, with permission [26].)

Investigators using animal model of cachexia frequently report efficacy in terms of final day’s food intake (prior to euthanizing) in the treatment group as compared to tumor-bearing controls. For faster-growing tumor cell lines, data may be alternatively be reported as cumulative food over the treatment course.

Weight gain is reported alongside food intake as another essential endpoint to follow (Figure 2B [26]). Similar to changes in food intake, total body weight does not usually change until symptoms of cachexia have started to accumulate, including decreased appetite and increased resting energy expenditure. One notable feature of assessing weight gain in cachexia that is unique to tumor models is the consideration of tumor weight when assessing drug efficacy for improving weight gain. Tumor weights are reported alongside bodyweight, since a medication that improves appetite but also stimulates tumor growth is not likely to be useful in clinical settings.

The next feature considered in the evaluation of efficacy in cachexia models relates to changes in body composition. Implanted tumors frequently result in a decrease in lean and fat mass over the course of tumor burden in quantities that can be severe depending on the time course followed. Body composition changes are usually evaluated via dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) before and after tumor placement or treatment. Other methodologies of body composition determination include dry carcass evaluation [41,42] and nuclear magnetic resonance [43]. The advantages to using DXA include the ability to obtain pre- and post-treatment data that includes evidence of bone mineral changes. Over the long-term, bone mineral content is lost in the setting of cachexia [44], though treatment courses are usually short enough as to make it difficult to note improvement in bone mineralization as a result of therapy. Certainly for the pre-treatment evaluation, DXA requires sedation of animals, which carries a small risk to the animals and requires more surveillance. For the post-treatment evaluation, the tumors are most frequently removed to better allow for comparison to sham-treated animals.

Dry carcass analysis has the advantage that because it does not require sedation, it is easier to employ on a large-scale measure [42]. Unfortunately, carcass analysis is unable to provide pre-treatment measurements, relying instead on a similar group of animals euthanized before tumor implantation. As such, carcass analysis provides a less exact report of body composition changes.

Whole animal nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurements overcome some of the problems with DXA and carcass analysis in that they are able to provide data regarding lean and fat mass of alive, mobile animals who do not require sedation. The drawbacks of these instruments are the expense of the equipment and lack of data regarding bone mineralization.

Finally, other features of human cachexia that are also measured as clinically-significant endpoints in animal models are an increase in resting energy expenditure and a decrease in voluntary movement. These processes can be detected via the use of metabolic clam cages [5,6] that can detect animal movement and temperature and can be equipped to measure indirect calorimetry [19].

Rarely are each of the above endpoints evaluated for a given compound, though demonstration of efficacy across these endpoints lends support for the compound’s effect on root causes of cachexia as opposed to treating individual symptoms alone. One endpoint not yet measured (because of ethical concerns) is the effect of the treatment compound on disease survival. Examination of effect on overall morbidity as an endpoint is possible, however, if humane, blinded assessment of animal morbidity were used to trigger euthanizing. Use of slower-growing, more indolent tumors may also improve the feasibility of such assessments of the effects on worsening disease state (and by inference, mortality). Animals receiving a therapeutic compound that ameliorates cachexia may be hypothesized to stave off morbidity as a result of treatment. These experiments would require careful ethical planning, but would have important implications for human disease, with the implication that successful treatment of cachexia may prolong overall survival.

Additionally, as human studies become more difficult to perform, animal models will be able to answer further questions regarding additional systemic effects of treatment compounds via detailed analysis of heart rate and blood pressure during treatment and necropsies following at the experiment’s end.

It is likely that not all tumor cell lines used in cachexia research effect each of these features of cachexia equally, and clearly the choice of model used and the particular endpoints to be evaluated should be chosen based on known cachexia features of a given tumor line.

3.4. Tumor types and treatments tested

Tumors used in models of cancer cachexia include both spontaneous tumors such as the Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC, first isolated from a C57Bl6 mouse by Margaret Lewis at the Wistar Institute in 1951) and induced tumors. The LLC is the most commonly-used and best-characterized animal model of cancer cachexia [5,6,19–22]. LLC cell lines are available for purchase through the American Type Culture Collection, a non-profit tissue-culture distribution center.

A variety of induced tumor cell lines are also used in mouse and rat models of cancer cachexia, including methylcholanthrene-induced sarcomas (e.g. MCG-101 in mice [29] and other varieties in rats [27,28,30,31], C26 colorectal carcinoma (mice)[24–26], prostate tumors [45], Yoshida AH-130 hepatoma (rats) [36–38,46], EHS chondrosarcomas (mice) [6], MAC16 colon adenocarcinoma [39,40], and Walker 256 carcinosarcomas (rat) [47]. Cross-species cell lines—including human lines—can be used in nude mice [48,49].

As mentioned previously, the successful treatment of cancer cachexia in humans has been elusive thus far. Hope for future success in humans has been bolstered by efficacy of multiple compounds in animal models, particularly melanocortin-4 receptor antagonists [6,50] and ghrelin [27,41,49,51]. Success using combinations of factors [47] and nutritional approaches [28,52] have also been reported. Other treatments have focused on ameliorating muscle wasting specifically [37,46]. Clearly, the importance of developing and testing new compounds continues as the clinical need for the treatment of cancer cachexia remains dire.

4. Cardiac Cachexia

Second to cancer cachexia in the number of humans affected, cachexia due to chronic heart failure is experienced by approximately 5 million Americans [53]. Cardiac cachexia involves similar features of other forms of cachexia, including anorexia, lean and fat mass loss and increased energy expenditure [54,55]. It is also felt to be due at least in part to inflammatory mediators produced in response to bacterial toxins absorbed through an edematous bowel wall [56], though other mechanisms are likely also responsible [57]. Animal models replicate the clinical findings of cardiac cachexia, relying on surgical techniques to either cause infarction of cardiac muscle or in limit left ventricular output to lead to congestive heart failure.

4.1. Myocardial infarction model

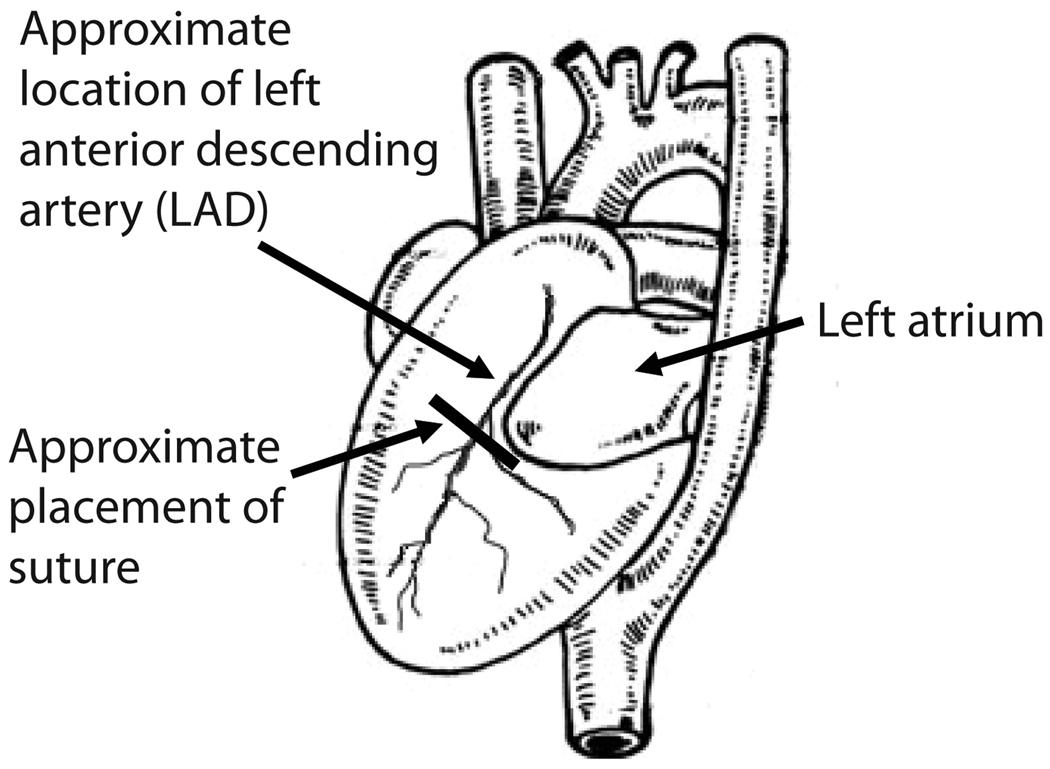

The myocardial infarction model involves surgical ligation of the anterior left descending artery (Figure 3). This can be performed in mice [58–60] and rats [61,62] in similar fashion. The procedure is performed via a sternotomy with a suture being placed just inferior to the left atrium. The suture is placed in a relatively blind fashion (i.e., the coronary itself is not visible), and the anatomy of the coronary artery is varied between animals. Because of this, the surgeon’s experience factors heavily in the procedure. When sutures are placed too superficially they may not ligate the artery and may not result in myocardial infarction. Sutures that placed more deeply in the myocardium are more likely to ligate the artery but may also perforate the myocardium. For this reason, this model can have a variable response regarding the production of myocardial infarction and a relatively high early mortality rate. Sham animals ideally receive identical needle placement without constricting the artery.

Figure 3.

Location of suture placement to ligate the left anterior descending artery. In the LAD ligation model, a sternotomy reveals the anterior surface of the heart, though the artery itself can be variable and is not visible to the surgeon. A suture is placed just inferior to the left atrium to block all perfusion distal to that point (Figure adapted from Green EL, editor: Biology of the Laboratory Mouse. ed Second, Ben Harbor, Maine, The Jackson Laboratory, 1968 [85] with permission.)

Following ligation, animals experience myocardial infarction and exhibit worsening systolic dysfunction. They develop an indolent course of worsening appetite, decreased weight gain, lean and fat body wasting, and increased basal VO2 utilization [58,59,61,62]. When the procedure is performed on fully-growth male rats (12 months old), frank weight loss is observed, as opposed to the decrease in weight gain seen in younger rats (<8 months old) [63]. Occasionally furosemide is given to both the treatment and placebo groups to decrease accumulation of edema [61].

4.2. Aortic banding model

An alternative model of cardiac cachexia utilizes restriction of cardiac output via aortic banding, which can also be performed in mice and rats. This model involves use of a left thoracic incision and constricture of the left ascending aorta using titanium clips. Over the ensuing 2–4 weeks, the animal develops congestive heart failure, with a decrease in appetite and a decrease in weight gain [58,59]. Some commercial vendors will perform this surgery prior to shipment of the animal, decreasing variability of surgical results that might occur as a laboratory technician accumulates experience over time.

4.3. Treatment course and endpoints

Following both of these procedures, symptoms of cachexia occur over the first 4 weeks following surgery, with a drop in food intake apparent by 3–4 weeks following surgery. Treatment with the prospective compound begins at 4 weeks after surgery and is given for 2–4 weeks. Given the long-term nature of the disease, treatment is more likely to be administered via oral dosing or via subcutaneous or intraperitoneal injection, though ICV administration has also been used.

The relatively longer time-frame required before animals develop severe morbidity allows for a longer period of testing in these models of cardiac cachexia than in the models of cancer cachexia, though it also requires an increase in resources utilized. As such, compounds with demonstrated efficacy using models of cardiac cachexia have already passed early tests for the development of tolerance to the treatment compound, in contrast to the short courses tested for cancer cachexia.

Many of the endpoints and techniques used to evaluate efficacy in cardiac cachexia overlap with those used for cancer cachexia. Food intake is followed and is most frequently reported in cumulative terms over the course of treatment. Changes in total body mass, lean mass and fat mass are important endpoints and are measured via DXA or NMR. Oxygen consumption and total energy expenditure can be assessed using clam cages and indirect calorimtry [58,59,61].

However, evaluation of the effect of putative cachexia treatments in animal models of chronic heart failure are unique in that they involve analysis of many technical aspects of cardiovascular function such as ventricular pressures and cardiac output. This involves carefully-performed techniques such as echocardiography and ventricular catheterization [61,62]. Additionally, gross- and histologic analysis of the myocardium is a critical aspect of these experiments, in order to verify efficacy of induced MI or aortic banding [58,59].

The effects of analyzing such a wide array of effects can lead to divergent results, such as the finding that ghrelin mimetics improve body weight gain and lean mass retention in the setting of cardiac cachexia without having significant effects on cardiovascular parameters [61]. Additional compounds tested using these models of cardiac cachexia include melanocortin antagonists [58,59]. Though treatment with beta-adrenergic antagonists has been shown to be efficacious in humans [64–66], their effects on cachexia using these rodent models has not been significantly characterized.

5. Animal Models of Chronic Kidney Disease

Chronic kidney disease results in cachexia in a large percentage of individuals on dialysis, and as seen in other types of cachexia, is associated with worsened outcomes [67,68]. As seen in cancer cachexia and chronic heart disease, the anorexia of CKD is felt to be due to increases in inflammation in this setting [67,71], though acidosis seen in this setting can also contribute to muscle wasting [72,73]. Animal models of CKD focus on increasing uremia in animals as a means of affecting changes in food intake and body composition. In testing for efficacy of compounds for the treatment of cachexia, surgical models have been employed in both mice and rats, gradually restricting the amount of functional kidney tissue and producing uremia.

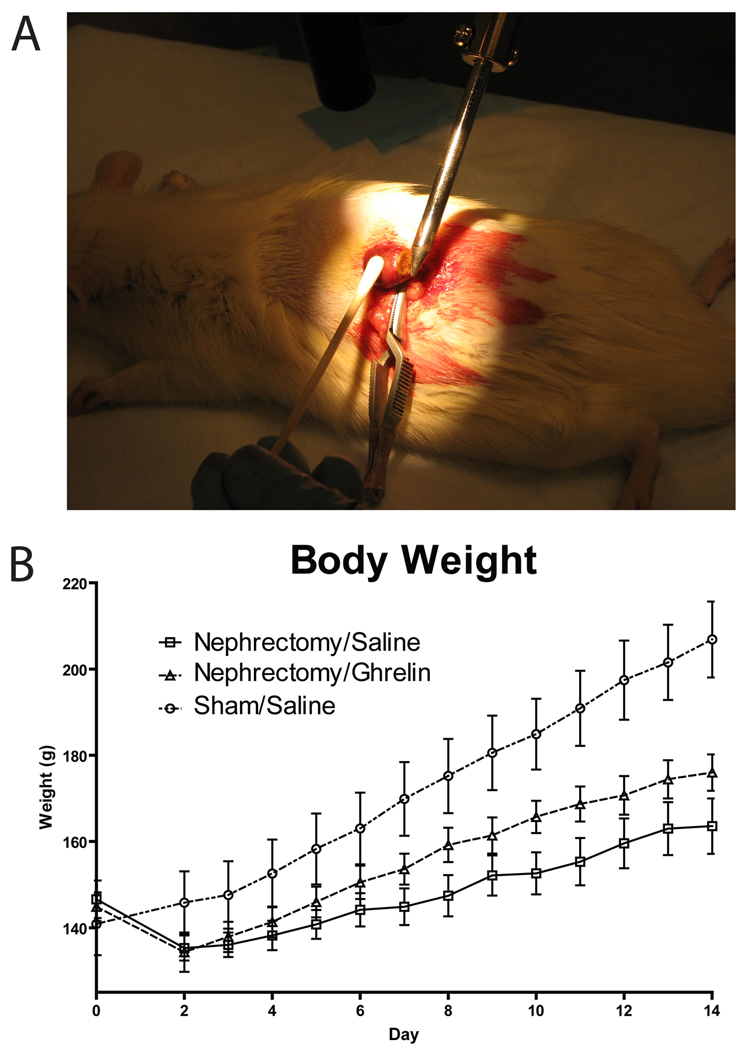

The 5/6 nephrectomy model is a two-staged procedure that results in only 1/6 of a functional kidney and resultant uremia. This procedure has been reported in both mice [74–76] and rats [44]. In the first stage of the procedure, one of the animal’s kidneys is isolated with care to maintain an intact vascular supply (Figure 4). The upper 1/3 and the lower 1/3 of the kidney is then excised, and cautery is used to control bleeding and induce scarring. Care is taken, however, to preserve the middle 1/3 of the kidney and the renal artery and vein. Once bleeding has stabilized, this portion is returned to the retroperitoneum and the wound sutured. The animal is then allowed to recover for 7–10 days before a second surgery is performed in which the contralateral kidney is surgically removed following ligation of the renal vessels. In both cases, sham-operated animals have the kidney isolated and the renal capsule incised prior to replacement of the intact kidney and wound closure.

Figure 4.

Surgical approach and weight effects of the 5/6 nephrectomy model. A. During the first stage of the procedure, one kidney is isolated and the upper and lower portion are excised and cauterized to leave the central 1/3 of the kidney functional. A second procedure then removes the contralateral kidney approximately 1 week later. (Photo by author.) B. Following the second procedure, weight gain is compromised vs. sham-treated animals but may be improved, as shown here during treatment with ghrelin. (Figure adapted from DeBoer MD et al. Ghrelin treatment of chronic kidney disease: improvements in lean body mass and cytokine profile. Endocrinology 2008;149:827–835. [44]; with permission.

Following removal of the second kidney, the animal becomes rapidly uremic, with creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels that increase by 100–200% over the ensuing 14 days. It is important to measure these levels at experiment’s end to document renal insufficiency. It is further important to assess for acidosis, which may produce symptoms of cachexia, including muscle wasting [72,73]. The 5/6 nephrectomy model is not typically associated with the production of acidosis when followed for 21-day periods after the second surgery [74–76].

Following the second stage surgery, appetite may decrease over a two-week period [44], though cumulative food intake may not differ from sham-operated animals [74–76]. Because of alterations in energy expenditure, poor weight gain is seen even without change in food intake, with a 60–85 percent decrease in weight gain vs. sham-operated animals [74–76]. Though animals do not loose overall weight over the course of the experiments, there are notable decreases in lean body mass (−1–5% in mice, 2% gain in young rats) and fat mass (−1–17% in mice, −30% in rats), compared to sham-operated animals that show gains in lean mass (+2–10% in mice, +50% in rats) and fat mass (+4–10% in mice, +28% in rats) [74–77].

Similar to the models of cancer cachexia and cardiac cachexia, another important endpoint followed in models of CKD is resting energy expenditure using clam cages with indirect calorimetry [74–76]. Following 2 weeks of after nephrectomy, animals have a 3–12% increase in basal metabolic rate compared to sham-treated animals. Measurement of basal metabolic rate enables calculation of the efficiency of food consumption, which is reduced by over 60% [74–76].

The CKD model has also been used to evaluate the effect of anti-cachexia treatment on muscle degradation dynamics, including analysis of the ubiquitome-proteosome [77] and myostatin pathways [76], as well as effects on mitochondrial protein activity [78] and uncoupling protein expression [75].

Similar to the models of cancer and cardiac cachexia, the models of CKD have been used to demonstrate efficacy of melanocortin-inhibitors [74–76] and ghrelin [44] on improving appetite, weight gain and lean body mass.

6. Other Animal Models of Cachexia

Additional models of cachexia including a short-term model of radiation-induced injury, which is produced by exposure of rodents to full-body radiation, resulting in a 25% reduction in food intake and weight loss over the subsequent 24 hours. This model has been used to demonstrate efficacy of the native melanocortin receptor antagonist AgRP [79].

Chemotherapy-induced anorexia is frequently referred to as dyspepsia and is thought to be due to a decrease in gastric emptying [80]. These symptoms can be induced via administration of cisplatin, an alkylating agent used extensively in cancer treatment. Cisplatin injections over a 3-day period results in anorexia and weight loss that keeps cisplatin-treated animals below the weight of control animals over a 7 day period. This technique has been used to demonstrate efficacy of ghrelin treatment to alleviate this weight loss [81,82].

7. Conclusion

Animal models of cachexia and anorexia provide an effective means of simulating the wasting associated with multiple underlying diseases. In the absence of large-scale human-subject trials of potential therapies, these models have been instrumental in demonstrating efficacy of a variety of different treatment compounds. During short- and intermediate-length treatment courses many of these compounds have been shown to improve multiple symptoms of cachexia, resulting in increased food intake, improved weight gain and decreased loss of lean and fat mass. With a large clinical need and continued lack of adequate treatments for patients with cachexia, these animal models allow for documenting multiple important outcomes—including toxicity—while limiting variables. As such, use of these models to further the discovery of new treatments remains of paramount importance to increase the likelihood of identifying safe and effective treatments for humans.

8. Expert opinion

The long gap in time between the initial demonstration of efficacy of some of these compounds (particularly the melanocortin antagonists [83]) in animal models and their application in humans fuels some concern that some treatments may carry risks that are not yet reported in the literature. Certainly, there have been notable appetite-suppressing medications that were promising at some stages of their development but were found to have unanticipated effects (e.g. fenfluramine [84] and melanocortin agonists [84], found cause valvular heart disease and hypertension, respectively). These concerns serve to highlight the importance of comprehensive testing in animal models prior to human application, examining for systemic effects on cardiovascular function and on the underlying disease state and collaborating with pathology laboratories to perform necropsies.

Collaborations with laboratories from different fields could also improve assessment of beneficial effects of treatment compounds. The complexities involved in evaluating a host of endpoints in these animal models make it difficult for a single group to fully investigate all of the important outcome measures for any given model. Interdisciplinary collaborations would reward researchers by providing novel insights regarding widespread effects of a prospective treatment compound. For example, many of the same humans—and likely mice—that suffer from chronic kidney disease are also more likely to develop cardiac disease [68]. Investigators who may be well-skilled in inducing renal disease in an animal model may lack the training and equipment to perform echocardiography or cardiac catheterization to evaluate the effects of their compound on cardiovascular outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Similarly, cancer researchers may collaborate with a neuroscience laboratory to administer a compound via intraventricular cannula. As has always been true in science, the sharing of ideas and techniques leads to innovation and furthers discovery.

Other outcomes that require more effort are the durability of anti-cachexia treatment and the effects of anti-cachexia compounds on the underlying disease state. When seen in clinical settings, cachexia is associated with a worsened prognosis. With the exception of treatment of cardiac cachexia leading to improved survival [58,59], effects of treatment on morbidity and mortality are lacking. When possible, it will be informative to assess the effect of treatment on the health of the animal. Analysis of effects on morbidity could be analyzed using blinded analysis of scoring systems of animal distress, with humane criteria to tigger euthanizing, to give an indication whether animals treated for cachexia live longer and with fewer sequelae of their underlying disease.

It will continue to be important to assess compounds for the common symptoms of cachexia using multiple models of disease to better suggest generalizability and treatment of proximal pathways responsible for cachexia. When possible, comparison of a compound’s efficacy using head-to-head application with established compounds (for example, SHU 9119, an early melanocortin antagonist [45]) would help to gauge one compound’s performance relative to another.

In summary, the future will need to bring use of these animal models to evaluate the effect of emerging compounds on primary endpoints such as increased food intake. However, these models will also enable researchers to more fully characterize established anti-cachexia compounds related to the underlying disease, the potential for tolerance, and unanticipated systemic side effects such as hepatic and cardiovascular sequelae.

In the end, trials of anti-cachexia compounds using human subjects are desperately needed prior to achieving the ultimate goal of improving the quality of life and (hopefully) the prognosis for humans suffering from cachexia. Nevertheless, human trials will not take place without the rigorous assessment of current and future compounds via careful testing in animal models, enabling an important progression from mice to men.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of interest

The authors’ work is funded by the NIH (grant HD060739-01)

References

- 1.Tisdale MJ. Biology of cachexia. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1763–1773. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.23.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeBoer MD, Marks DL. Therapy insight: Use of melanocortin antagonists in the treatment of cachexia in chronic disease. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2:459–466. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laviano A, Meguid MM, Inui A, Muscaritoli M, Rossi-Fanelli F. Therapy insight: Cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome--when all you can eat is yourself. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:158–165. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang QH, Hruby VJ, Tatro JB. Role of central melanocortins in endotoxin-induced anorexia. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:R864–R871. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.3.R864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks DL, Butler AA, Turner R, Brookhart GB, Cone RD. Differential role of melanocortin receptor subtypes in cachexia. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1513–1523. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marks DL, Ling N, Cone RD. Role of the Central Melanocortin System in Cachexia. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1432–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Reilly B, Vander AJ, Kluger MJ. Effects of chronic infusion of lipopolysaccharide on food intake and body temperature of the rat. Physiol Behav. 1988;42:287–291. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(88)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plata-Salaman CR, Oomura Y, Kai Y. Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 beta: suppression of food intake by direct action in the central nervous system. Brain Res. 1988;448:106–114. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kent S, Rodriguez F, Kelley KW, Dantzer R. Reduction in food and water intake induced by microinjection of interleukin-1 beta in the ventromedial hypothalamus of the rat. Physiol Behav. 1994;56:1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90339-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sonti G, Ilyin SE, Plata-Salaman CR. Anorexia induced by cytokine interactions at pathophysiological concentrations. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R1394–R1402. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.6.R1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reyes TM, Sawchenko PE. Involvement of the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus in interleukin-1-induced anorexia. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5091–5099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05091.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeBoer MD, Scarlett JM, Levasseur PR, Grant WF, Marks DL. Administration of IL-1beta to the 4th ventricle causes anorexia that is blocked by agouti-related peptide and that coincides with activation of tyrosine-hydroxylase neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract. Peptides. 2009;30:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otterness IG, Golden HW, Brissette WH, Seymour PA, Daumy GO. Effects of continuously administered murine interleukin-1 alpha: tolerance development and granuloma formation. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2742–2750. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.9.2742-2750.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan BH, Fearon KC. Cachexia: prevalence and impact in medicine. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:400–407. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328300ecc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dewys WD, Begg C, Lavin PT, Band PR, Bennett JM, Bertino JR, Cohen MH, Douglass HO, Jr, Engstrom PF, Ezdinli EZ, Horton J, Johnson GJ, Moertel CG, Oken MM, Perlia C, Rosenbaum C, Silverstein MN, Skeel RT, Sponzo RW, Tormey DC. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Med. 1980;69:491–497. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(05)80001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deans C, Wigmore SJ. Systemic inflammation, cachexia and prognosis in patients with cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2005;8:265–269. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000165004.93707.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeBoer MD, Marks DL. Cachexia: lessons from melanocortin antagonism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fearon KCH, Moses AGM. Cancer Cachexia. Int. J. Cardiol. 2002;85:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markison S, Foster AC, Chen C, Brookhart GB, Hesse A, Hoare SR, Fleck BA, Brown BT, Marks DL. The regulation of feeding and metabolic rate and the prevention of murine cancer cachexia with a small-molecule melanocortin-4 receptor antagonist. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2766–2773. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholson JR, Kohler G, Schaerer F, Senn C, Weyermann P, Hofbauer KG. Peripheral administration of a melanocortin 4-receptor inverse agonist prevents loss of lean body mass in tumor-bearing mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:771–777. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.097725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang W, Tucci FC, Tran JA, Fleck BA, Wen J, Markison S, Marinkovic D, Chen CW, Arellano M, Hoare SR, Johns M, Foster AC, Saunders J, Chen C. Pyrrolidinones as potent functional antagonists of the human melanocortin-4 receptor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:5610–5613. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.07.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran JA, Jiang W, Tucci FC, Fleck BA, Wen J, Sai Y, Madan A, Chen TK, Markison S, Foster AC, Hoare SR, Marks D, Harman J, Chen CW, Arellano M, Marinkovic D, Bozigian H, Saunders J, Chen C. Design, synthesis, in vitro, and in vivo characterization of phenylpiperazines and pyridinylpiperazines as potent and selective antagonists of the melanocortin-4 receptor. J Med Chem. 2007;50:6356–6366. doi: 10.1021/jm701137s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen C, Tucci FC, Jiang W, Tran JA, Fleck BA, Hoare SR, Wen J, Chen T, Johns M, Markison S, Foster AC, Marinkovic D, Chen CW, Arellano M, Harman J, Saunders J, Bozigian H, Marks D. Pharmacological and pharmacokinetic characterization of 2-piperazine-alpha-isopropyl benzylamine derivatives as melanocortin-4 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:5606–5618. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joppa MA, Gogas KR, Foster AC, Markison S. Central infusion of the melanocortin receptor antagonist agouti-related peptide (AgRP(83–132)) prevents cachexia-related symptoms induced by radiation and colon-26 tumors in mice. Peptides. 2007;28:636–642. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vos TJ, Caracoti A, Che JL, Dai M, Farrer CA, Forsyth NE, Drabic SV, Horlick RA, Lamppu D, Yowe DL, Balani S, Li P, Zeng H, Joseph IB, Rodriguez LE, Maguire MP, Patane MA, Claiborne CF. Identification of 2-[2-[2-(5-bromo-2- methoxyphenyl)-ethyl]-3-fluorophenyl]-4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazole (ML00253764), a small molecule melanocortin 4 receptor antagonist that effectively reduces tumor-induced weight loss in a mouse model. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1602–1604. doi: 10.1021/jm034244g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weyermann P, Dallmann R, Magyar J, Anklin C, Hufschmid M, Dubach-Powell J, Courdier-Fruh I, Hennebohle M, Nordhoff S, Mondadori C. Orally available selective melanocortin-4 receptor antagonists stimulate food intake and reduce cancer-induced cachexia in mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeBoer MD, Zhu XX, Levasseur P, Meguid MM, Suzuki S, Inui A, Taylor JE, Halem HA, Dong JZ, Datta R, Culler MD, Marks DL. Ghrelin treatment causes increased food intake and retention of lean body mass in a rat model of cancer cachexia. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3004–3012. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramos EJ, Middleton FA, Laviano A, Sato T, Romanova I, Das UN, Chen C, Qi Y, Meguid MM. Effects of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on tumor-bearing rats. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:716–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Z, Wang W, Qiu W, Fan Y, Zhao J, Wang Y, Zheng Q. Involvement of ghrelin-growth hormone secretagogue receptor system in pathoclinical profiles of digestive system cancer. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2007;39:992–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2007.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramos EJ, Romanova IV, Suzuki S, Chen C, Ugrumov MV, Sato T, Goncalves CG, Meguid MM. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on orexigenic and anorexigenic modulators at the onset of anorexia. Brain Res. 2005;1046:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goncalves CG, Ramos EJ, Romanova IV, Suzuki S, Chen C, Meguid MM. Omega-3 fatty acids improve appetite in cancer anorexia, but tumor resecting restores it. Surgery. 2006;139:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rebeca R, Bracht L, Noleto GR, Martinez GR, Cadena SM, Carnieri EG, Rocha ME, de Oliveira MB. Production of cachexia mediators by Walker 256 cells from ascitic tumors. Cell Biochem Funct. 2008;26:731–738. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cahlin C, Korner A, Axelsson H, Wang W, Lundholm K, Svanberg E. Experimental cancer cachexia: the role of host-derived cytokines interleukin (IL)-6, IL-12, interferon-gamma, and tumor necrosis factor alpha evaluated in gene knockout, tumor-bearing mice on C57 Bl background and eicosanoid-dependent cachexia. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5488–5493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Argiles JM, Busquets S, Garcia-Martinez C, Lopez-Soriano FJ. Mediators involved in the cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome: past, present, and future. Nutrition. 2005;21:977–985. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim S, Takahashi H, Lin WW, Descargues P, Grivennikov S, Kim Y, Luo JL, Karin M. Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature. 2009;457:102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature07623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Busquets S, Alvarez B, van Royen M, Carbo N, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Argiles JM. Lack of effect of the cytokine suppressive agent FR167653 on tumour growth and cachexia in rats bearing the Yoshida AH-130 ascites hepatoma. Cancer Lett. 2000;157:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Busquets S, Figueras MT, Fuster G, Almendro V, Moore-Carrasco R, Ametller E, Argiles JM, Lopez-Soriano FJ. Anticachectic effects of formoterol: a drug for potential treatment of muscle wasting. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6725–6731. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muscaritoli M, Costelli P, Bossola M, Grieco G, Bonelli G, Bellantone R, Doglietto GB, Rossi-Fanelli F, Baccino FM. Effects of simvastatin administration in an experimental model of cancer cachexia. Nutrition. 2003;19:936–939. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bibby MC, Double JA, Ali SA, Fearon KC, Brennan RA, Tisdale MJ. Characterization of a transplantable adenocarcinoma of the mouse colon producing cachexia in recipient animals. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;78:539–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beck SA, Tisdale MJ. Production of lipolytic and proteolytic factors by a murine tumor-producing cachexia in the host. Cancer Res. 1987;47:5919–5923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang W, Andersson M, Iresjo BM, Lonnroth C, Lundholm K. Effects of ghrelin on anorexia in tumor-bearing mice with eicosanoid-related cachexia. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:1393–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eden E, Lindmark L, Karlberg I, Lundholm K. Role of whole-body lipids and nitrogen as limiting factors for survival in tumor-bearing mice with anorexia and cachexia. Cancer Res. 1983;43:3707–3711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang XM, Tang GY, Cheng YS, Zhou B. Evaluation of a rabbit rectal VX2 carcinoma model using computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2139–2144. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeBoer MD, Zhu X, Levasseur PR, Inui A, Hu Z, Han G, Mitch WE, Taylor JE, Halem HA, Dong JZ, Datta R, Culler MD, Marks DL. Ghrelin treatment of chronic kidney disease: improvements in lean body mass and cytokine profile. Endocrinology. 2008;149:827–835. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wisse BE, Frayo RS, Schwartz MW, Cummings DE. Reversal of cancer anorexia by blockade of central melanocortin receptors in rats. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3292–3301. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.8.8324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carbo N, Lopez-Soriano J, Tarrago T, Gonzalez O, Llovera M, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Argiles JM. Comparative effects of beta2-adrenergic agonists on muscle waste associated with tumour growth. Cancer Lett. 1997;115:113–118. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)04718-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piffar PM, Fernandez R, Tchaikovski O, Hirabara SM, Folador A, Pinto GJ, Jakobi S, Gobbo-Bordon D, Rohn TV, Fabricio VE, Moretto KD, Tosta E, Curi R, Fernandes LC. Naproxen, clenbuterol and insulin administration ameliorates cancer cachexia and reduce tumor growth in Walker 256 tumor-bearing rats. Cancer Lett. 2003;201:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanada T, Toshinai K, Date Y, Kajimura N, Tsukada T, Hayashi Y, Kangawa K, Nakazato M. Upregulation of ghrelin expression in cachectic nude mice bearing human melanoma cells. Metabolism. 2004;53:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2003.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hanada T, Toshinai K, Kajimura N, Nara-Ashizawa N, Tsukada T, Hayashi Y, Osuye K, Kangawa K, Matsukura S, Nakazato M. Anti-cachectic effect of ghrelin in nude mice bearing human melanoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:275–279. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)03028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeBoer M. Update on melanocortin interventions for cachexia: Progress toward clinical application. Nutrition. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.07.003. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeBoer MD. Emergence of ghrelin as a treatment for cachexia syndromes. Nutrition. 2008;24:806–814. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Norren K, Kegler D, Argiles JM, Luiking Y, Gorselink M, Laviano A, Arts K, Faber J, Jansen H, van der Beek EM, van Helvoort A. Dietary supplementation with a specific combination of high protein, leucine, and fish oil improves muscle function and daily activity in tumour-bearing cachectic mice. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:713–722. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.von Haehling S, Lainscak M, Springer J, Anker SD. Cardiac cachexia: a systematic overview. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121:227–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anker S. Cachexia and cardiology. Circulation. 2006;113:f53–f54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anker SD, Ponikowski P, Varney S, Chua TP, Clark AL, Webb-Peploe KM, Harrington D, Kox WJ, Poole-Wilson PA, Coats AJ. Wasting as independent risk factor for mortality in chronic heart failure. Lancet. 1997;349:1050–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rauchhaus M, Coats AJ, Anker SD. The endotoxin-lipoprotein hypothesis. Lancet. 2000;356:930–933. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02690-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anker SD, Sharma R. The syndrome of cardiac cachexia. Int J Cardiol. 2002;85:51–66. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bowe DD, Scarlett JM, Basra AK, Steiner RA, Marks DL. Blockade of central melanocortin signaling promotes accumulation of lean body mass in rodent models of chronic heart failure. J Investig Med. 2007;55:S77. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Basra AK, Scarlett JM, Bowe DD, Steiner RA, Marks DL. Central melanocortin blockade attenuates cardiac cachexia in a rat model of chronic heart failure. J Investig Med. 2008;56:229–230. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gould KE, Taffet GE, Michael LH, Christie RM, Konkol DL, Pocius JS, Zachariah JP, Chaupin DF, Daniel SL, Sandusky GE, Jr, Hartley CJ, Entman ML. Heart failure and greater infarct expansion in middle-aged mice: a relevant model for postinfarction failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H615–H621. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00206.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Akashi YJ, Palus S, Datta R, Halem H, Taylor JE, Thoene-Reineke C, Dong J, Thum T, Culler MD, Anker SD, Springer J. No effects of human ghrelin on cardiac function despite profound effects on body composition in a rat model of heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.06.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nagaya N, Uematsu M, Kojima M, Ikeda Y, Yoshihara F, Shimizu W, Hosoda H, Hirota Y, Ishida H, Mori H, Kangawa K. Chronic administration of ghrelin improves left ventricular dysfunction and attenuates development of cardiac cachexia in rats with heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:1430–1435. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.095575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Palus S, Akashi Y, von Haehling S, Anker SD, Springer J. The influence of age and sex on disease development in a novel animal model of cardiac cachexia. Int J Cardiol. 2009;133:388–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hryniewicz K, Androne AS, Hudaihed A, Katz SD. Partial reversal of cachexia by beta-adrenergic receptor blocker therapy in patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2003;9:464–468. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(03)00582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lainscak M, Keber I, Anker SD. Body composition changes in patients with systolic heart failure treated with beta blockers: a pilot study. Int J Cardiol. 2006;106:319–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Springer J, Filippatos G, Akashi YJ, Anker SD. Prognosis and therapy approaches of cardiac cachexia. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2006;21:229–233. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000221585.94490.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chertow GM, Johansen KL, Lew N, Lazarus JM, Lowrie EG. Vintage, nutritional status, and survival in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2000;57:1176–1181. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang AY, Sea MM, Tang N, Sanderson JE, Lui SF, Li PK, Woo J. Resting energy expenditure and subsequent mortality risk in peritoneal dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:3134–3143. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000144206.29951.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mak RH, Cheung W, Cone RD, Marks DL. Orexigenic and anorexigenic mechanisms in the control of nutrition in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:427–431. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1789-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mak RH, Cheung W, Cone RD, Marks DL. Mechanisms of disease: Cytokine and adipokine signaling in uremic cachexia. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:527–534. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qureshi AR, Alvestrand A, Divino-Filho JC, Gutierrez A, Heimburger O, Lindholm B, Bergstrom J. Inflammation, malnutrition, and cardiac disease as predictors of mortality in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13 Suppl 1:S28–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mitch WE. Malnutrition: a frequent misdiagnosis for hemodialysis patients. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:437–439. doi: 10.1172/JCI16494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pickering WP, Price SR, Bircher G, Marinovic AC, Mitch WE, Walls J. Nutrition in CAPD: serum bicarbonate and the ubiquitin-proteasome system in muscle. Kidney Int. 2002;61:1286–1292. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheung W, Yu PX, Little BM, Cone RD, Marks DL, Mak RH. Role of leptin and melanocortin signaling in uremia-associated cachexia. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1659–1665. doi: 10.1172/JCI22521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheung WW, Kuo HJ, Markison S, Chen C, Foster AC, Marks DL, Mak RH. Peripheral administration of the melanocortin-4 receptor antagonist NBI-12i ameliorates uremia-associated cachexia in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:2517–2524. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006091024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cheung WW, Rosengren S, Boyle DL, Mak RH. Modulation of melanocortin signaling ameliorates uremic cachexia. Kidney Int. 2008;74:180–186. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barazzoni R, Zhu XX, DeBoer MD, Datta R, Culler MD, Zanetti M, Guarnieri G, Marks DL. Combined effects of ghrelin and attenuated anorexia enhance skeletal muscle mitochondrial oxidative capacity and AKT phosphorylation in rats with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.411. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Joppa MA, Gogas KR, Foster AC, Markison S. Central infusion of the melanocortin receptor antagonist agouti-related peptide (AgRP(83–132)) prevents cachexia-related symptoms induced by radiation and colon-26 tumors in mice. Peptides. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nelson K, Walsh D, Sheehan F. Cancer and chemotherapy-related upper gastrointestinal symptoms: the role of abnormal gastric motor function and its evaluation in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:455–461. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garcia JM, Cata JP, Dougherty PM, Smith RG. Ghrelin prevents cisplatin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and cachexia. Endocrinology. 2008;149:455–460. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu YL, Malik NM, Sanger GJ, Andrews PL. Ghrelin alleviates cancer chemotherapy-associated dyspepsia in rodents. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;58:326–333. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.DeBoer MD. Melanocortin interventions in cachexia: how soon from bench to bedside? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10:457–462. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328108f441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Connolly HM, Crary JL, McGoon MD, Hensrud DD, Edwards BS, Edwards WD, Schaff HV. Valvular heart disease associated with fenfluramine-phentermine. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:581–588. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708283370901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Greenfield JR, Miller JW, Keogh JM, Henning E, Satterwhite JH, Cameron GS, Astruc B, Mayer JP, Brage S, See TC, Lomas DJ, O'Rahilly S, Farooqi IS. Modulation of blood pressure by central melanocortinergic pathways. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:44–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Green EL, editor. Biology of the Laboratory Mouse. ed Second. Ben Harbor, Maine: The Jackson Laboratory; 1968. [Google Scholar]