Abstract

Objective

To describe the prevalence of refractive error in the United States.

Methods

The 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) used an autorefractor to obtain refractive error data on a nationally representative sample of the U.S. non-institutionalized, civilian population aged ≥12 years. Using data from the eye with greater absolute spherical equivalent (SphEq) value, we defined clinically important refractive error as: hyperopia: SphEq ≥+3.0D; myopia: SphEq ≤−1.0D; and astigmatism: cylinder ≥1.0D in either eye.

Results

Of 14,213 participants aged ≥20 years who had an NHANES examination, refractive error data were obtained for 12,010 (84.5%). The age-standardized prevalences of hyperopia, myopia, and astigmatism were 3.6% (95% confidence interval (CI), 3.2–4.0%), 33.1% (95% CI, 31.5–34.7%), and 36.2% (95% CI, 34.9–37.5%), respectively. Myopia was more prevalent in females (40%) than in males (33%; p<0.0001) among 20–39-year-olds. Persons aged ≥60 years were less likely to have myopia and more likely to have hyperopia and/or astigmatism than younger persons. Myopia was more common in non-Hispanic whites (35.2%) than in non-Hispanic blacks (28.6%; p<0.0001) or Mexican Americans (25.1%; p<0.0001).

Conclusions

Estimates based on the 1999–2004 NHANES vision examination data indicate that clinically important refractive error affects half of the U.S. population aged ≥20 years.

Introduction

Refractive error is recognized as one of the most important causes of correctable visual impairment (1, 2, 3, 4), accounting for nearly 80% of the visual impairment in persons aged 12 years and older in the United States (5). Providing eye care services to the large number of persons who use or need refractive correction involves substantial expense: the direct annual cost of refractive correction for distance visual impairment is estimated to be between $3.8 and $7.2 billion (6) for persons aged 12 years and older (based on an estimated annual direct cost per person of $35 to $56), and in a separate study of persons aged 40 years and older, $5.5 billion (7). We used the 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data to estimate the population prevalence of refractive error and to describe the refractive characteristics of the U.S. population in greater detail.

Methods

NHANES is an ongoing nationally representative survey of the U.S. civilian, non-institutionalized population conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (8, 9). Participants in the NHANES undergo a home interview and subsequent comprehensive physical examination and functional assessment in a Mobile Examination Center (MEC) (8). The 1999–2004 NHANES protocol was reviewed and approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board. All participants (parent or guardian of minors) gave their written informed consent after receiving a description of the study and the potential risks of participation.

Demographic characteristics were collected at the household interview. Participants reported their ethnicity and race (10). NCHS later categorized these classifications into non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, Mexican American, or “other” (including Asian (various countries), Pacific Islander, Native American, non-Mexican-American Hispanic, or multiracial).

The vision examination was conducted on participants aged 12 years and older. A NIDEK ARK-760 autorefractor (Nidek Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used to measure the refractive error of each eye after corrective lenses had been removed. Three separate measurements of sphere, cylinder, and axis were acquired and averaged by the ARK-760. For myopia and hyperopia, we categorized participants based on the refractive error measurements from the eye with the larger absolute value of spherical equivalent (SphEq). If one eye had missing refractive error data, data from the non-missing eye were used. Refractions were recorded in plus cylinder notation and SphEq was computed as the sphere measurement plus half the cylinder measurement. Clinically important myopia was defined as myopic SphEq of at least −1.0 diopter; clinically important hyperopia was defined as hyperopic SphEq of +3.0 diopters or more. Severe myopia was defined as myopic SphEq of at least −5.0 diopters (11,12). We also present data with myopia defined as SphEq of at least −0.5 diopter. Astigmatism was defined as cylinder ≥ 1.0 diopter in the eye with the larger cylinder value.

Because of time constraints imposed by the comprehensive NHANES examination, it was not feasible to obtain cycloplegic refractions. Accommodation may therefore have affected the measurement of refractive error, particularly in younger participants, despite the auto fogging used by the autorefractor to minimize accommodation. Consequently, for persons aged 12–19 years, prevalence of myopia is likely to be overestimated and prevalence of hyperopia is likely to be underestimated by the autorefractor measurements. We therefore have not used refractive error data from NHANES 1999–2004 for estimating the prevalence of refractive error among persons aged 12–19 years.

Refractive error data obtained from eyes with a history of cataract surgery or refractive surgery, or in which contact lenses were worn during objective refraction, were treated as missing values. Participants excluded from analyses (n=2203) included those reporting a history of cataract surgery (n=791) or refractive surgery (n=142) in both eyes, or who wore contact lenses during objective refraction (n=19), or who were missing autorefractor data for both eyes (n=1251 due to lack of time, inability to cooperate with the protocol, or equipment malfunction). We included 615 participants with refractive error data for only one eye (the fellow eye had cataract extraction (n=264), refractive surgery (n=21), or missing autorefractor data (n=330)).

The NHANES utilizes a complex, multistage probability sample design with oversampling within selected demographic subgroups (13). Sampling weights derived by NCHS statisticians reflect the probability of selection into the sample and incorporate adjustments for differential non-response and poststratification (14, 15), and their incorporation into analyses (using SUDAAN (Software for the Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data, version 9.0.0, Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC 16) ensures that the weighted estimates reflect the U.S. population sizes for specified demographic categories and that standard errors are unbiased (17,18). We age-standardized prevalence estimates to the U.S. 2000 Census population (19).

Results

A total of 14,213 participants aged 20 years and older participated in the 1999–2004 NHANES MEC examination. Of these, 12,010 (84.5%) had complete refractive error data (Table 1). Participants with incomplete refractive error data were more likely to be older, female, report lower income, and have fewer years of formal education.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants aged 20 years and older reporting to the Mobile Examination Center, NHANES 1999–2004.

| Complete refractive error data (n=12,010) |

Incomplete refractive error data (n=2,203) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % | 95% CI* | N | % | 95% CI |

| Age | ||||||

| 20–39 | 4653 | 41.6 | 39.9–43.3 | 415 | 24.6 | 21.6–27.5 |

| 40–59 | 3776 | 39.4 | 38.0–40.8 | 385 | 27.6 | 25.2–30.1 |

| 60+ | 3581 | 19.0 | 17.8–20.2 | 1403 | 47.8 | 44.4–51.2 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 6220 | 51.2 | 50.5–52.0 | 1258 | 58.8 | 55.4–62.2 |

| Male | 5790 | 48.8 | 48.0–49.5 | 945 | 41.2 | 37.8–44.6 |

| Race-ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 2343 | 10.6 | 8.6–12.6 | 404 | 13.2 | 10.3–16.0 |

| Mexican American | 2728 | 7.1 | 5.4–8.7 | 479 | 9.6 | 7.2–12.1 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 5841 | 71.8 | 68.5–75.1 | 1160 | 68.0 | 64.0–72.0 |

| Other† | 998 | 10.4 | 7.9–13.0 | 160 | 9.2 | 6.2–12.1 |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than High School | 3682 | 19.9 | 18.6–21.2 | 968 | 26.6 | 23.9–29.3 |

| High School | 2899 | 26.5 | 24.9–28.0 | 472 | 24.8 | 21.7–27.9 |

| Some college | 5413 | 53.6 | 51.6–55.7 | 747 | 48.6 | 44.8–52.3 |

| Income | ||||||

| Below poverty level | 1985 | 13.3 | 11.9–14.7 | 445 | 17.5 | 14.6–20.4 |

| At or near poverty level | 2810 | 20.8 | 19.1–22.4 | 619 | 23.2 | 20.9–25.5 |

| Above (2x) poverty level | 6212 | 65.9 | 63.4–68.4 | 882 | 59.2 | 55.2–63.3 |

| Health insurance, < 65 yrs | ||||||

| Uninsured | 2411 | 19.8 | 18.2–21.5 | 249 | 18.6 | 15.7–21.5 |

| Private (± other coverage) | 5818 | 70.7 | 68.6–72.8 | 523 | 65.8 | 61.7–70.0 |

| Medicaid (no private coverage) | 634 | 4.6 | 3.8–5.4 | 101 | 9.3 | 6.8–11.7 |

| Medicare/other federal | 403 | 4.9 | 4.0–5.7 | 60 | 6.3 | 4.3–8.3 |

| Health insurance, >=65 yrs | ||||||

| Uninsured | 62 | 1.0 | 0.5–1.4 | 21 | 1.0 | 0.4–1.6 |

| Private only | 224 | 8.4 | 6.4–10.5 | 80 | 6.0 | 3.8–8.3 |

| Private + Medicare | 986 | 46.0 | 42.6–49.3 | 452 | 42.8 | 38.9–46.7 |

| Medicare ± other federal | 1148 | 42.5 | 39.3–45.8 | 630 | 47.4 | 43.5–51.2 |

| Medicaid and/or other federal | 98 | 2.1 | 1.4–2.8 | 45 | 2.8 | 1.3–4.3 |

CI: Confidence interval.

”Other”: persons reporting their race-ethnicity as Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Asian Indian, Southeast Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander, non-Mexican-American Hispanic, or multiracial.

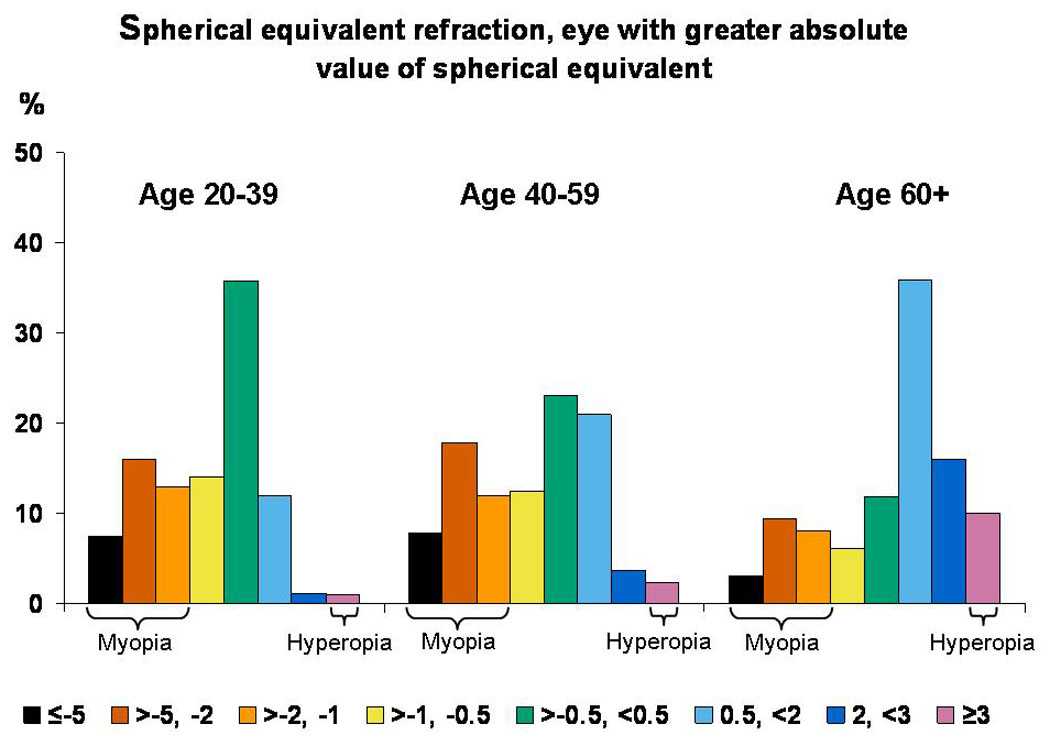

The distribution of SphEq refraction by age is shown in Figure 1. Participants aged 60 years and older were less likely to have myopic refractive error and more likely to have hyperopic refractive error than younger individuals.

Figure 1.

Distribution of spherical equivalent, by age. Data for those aged 12–19 years are not 4 shown because of the possible effects of accommodation on non-cycloplegic refractions.

Hyperopia

The prevalence of hyperopia (SphEq ≥3.0D) (Table 2) for ages 20–39, 40–59, and ≥60 years was 1.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.6–1.4%), 2.4 % (CI, 1.7–3.0%), and 10.0% (CI, 9.1–10.9%), respectively. In persons aged 60 years and older, hyperopia was more common in females (12.9%) than in males (6.6%; p<0.0001).

Table 2.

Prevalence of hyperopia (≥ 3 diopter spherical equivalent) by race-ethnicity, gender, and age, NHANES 1999–2004.

| Prevalence and 95% CI* for ages: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–39 years |

40–59 years |

60 years and older |

20 years and older |

40 years and older |

|

| Total | 1.0 | 2.4 | 10.0 | 3.6 | 5.3 |

| 0.6–1.4 | 1.7–3.0 | 9.1–10.9 | 3.2–4.0 | 4.7–5.8 | |

| Males | 1.3 | 2.2 | 6.6 | 2.8 | 3.8 |

| 0.7–1.8 | 1.4–2.9 | 5.1–8.0 | 2.4–3.2 | 3.2–4.5 | |

| Females | 0.8 | 2.7 | 12.9 | 4.2 | 6.5 |

| 0.3–1.3 | 1.7–3.6 | 11.4–14.4 | 3.7–4.8 | 5.7–7.3 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 0.8 | 2.2 | 5.6 | 2.5 | 3.5 |

| black | 0.2–1.5 | 1.0–3.4 | 3.8–7.3 | 1.6–3.2 | 2.4–4.6 |

| Males | 1.6 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

| 0.3–2.9 | 0.3–3.0 | 0.3–4.0 | 1.0–2.4 | 0.8–2.7 | |

| Females | 0.3 | 2.7 | 8.0 | 3.0 | 4.8 |

| 0.0–0.6 | 0.9–4.4 | 4.8–11.1 | 1.8–4.1 | 2.9–6.6 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 1.1 | 2.5 | 10.2 | 3.7 | 5.4 |

| white | 0.6–1.7 | 1.7–3.3 | 9.2–11.2 | 3.3–4.2 | 4.8–6.1 |

| Males | 1.2 | 2.3 | 6.9 | 3.0 | 4.1 |

| 0.4–2.0 | 1.5–3.2 | 5.2–8.5 | 2.5–3.4 | 3.4–4.8 | |

| Females | 1.0 | 2.7 | 13.1 | 4.4 | 6.6 |

| 0.3–1.7 | 1.5–4.0 | 11.5–14.8 | 3.7–5.1 | 5.6–7.6 | |

| Mexican | 0.4 | 1.5 | 8.7 | 2.7 | 4.2 |

| American | 0.0–0.7 | 0.7–2.2 | 6.6–10.9 | 2.0–3.4 | 3.2–5.3 |

| Males | 0.2 | 0.7 | 5.6 | 1.6 | 2.6 |

| 0.0–0.5 | 0.0–1.6 | 2.6–8.6 | 0.8–2.4 | 1.3–3.9 | |

| Females | 0.6 | 2.3 | 11.6 | 3.8 | 5.8 |

| 0.0–1.2 | 1.1–3.4 | 9.1–14.1 | 2.8–4.7 | 4.4–7.3 | |

| Other | 1.3 | 2.3 | 12.8 | 4.4 | 6.4 |

| 0.2–2.4 | 0.8–3.8 | 6.5–19.2 | 2.7–6.0 | 3.8–8.9 | |

| Males | 2.1 | 2.2 | 7.8 | 3.4 | 4.3 |

| 0.2–4.0 | 0.0–4.6 | 3.0–12.5 | 1.7–5.2 | 1.8–6.8 | |

| Females | 0.5 | 2.4 | 16.4 | 4.9 | 7.8 |

| 0.0–1.5 | 0.1–4.8 | 7.8–24.9 | 2.9–6.9 | 4.4–11.2 | |

CI: Confidence interval.

Myopia

The overall pattern of myopia prevalence by age and gender was similar, regardless of the definition of myopia (≤−1.0D, ≤−0.5D, or ≤−5.0D): prevalence estimates were approximately equal for the 20–39 and 40–59-year age groups and markedly lower for those aged ≥60 years, and for those aged 20–39 years, females had higher prevalence than males. For myopia defined as SphEq ≤−1.0D (Table 3), prevalence estimates for ages 20–39, 40–59, and ≥60 years were 36.2% (CI, 34.2–38.3%), 37.6% (CI, 35.1–40.1%), and 20.5% (CI, 18.3–22.8%), respectively. Myopia ≤−1.0D was more prevalent in non-Hispanic whites (35.2%) than in non-Hispanic blacks (28.6%; p<0.0001) or Mexican Americans (25.1%; p<0.0001). For those aged 60 years and older, no differences in prevalence were observed among race-ethnicity categories or between males and females. For ages 20–39 and 40–59 years, prevalence of myopia ≤−1.0D was higher for non-Hispanic whites (38.7 and 40.6%, respectively) than for non-Hispanic blacks (32.0%, p=0.0004; 32.1%, p=0.0003) or Mexican Americans (27.1%, p<0.0001; 26.4%, p<0.0001). For those aged 20 to 39 years, females had a slightly higher prevalence of myopia ≤−1.0D (39.9%) than did males (32.6%; p<0.0001).

Table 3.

Prevalence of myopia (≤ −1 diopter spherical equivalent) by race-ethnicity, gender, and age, NHANES 1999–2004.

| Prevalence and 95% CI* for ages: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–39 years |

40–59 years |

60 years and older |

20 years and older |

40 years and older |

|

| Total | 36.2 | 37.6 | 20.5 | 33.1 | 31.0 |

| 34.2–38.3 | 35.1–40.1 | 18.3–22.8 | 31.5–34.7 | 29.1–32.9 | |

| Males | 32.6 | 36.9 | 22.8 | 31.9 | 31.5 |

| 29.9–35.2 | 33.9–40.0 | 20.0–25.4 | 30.1–33.8 | 29.2–33.7 | |

| Females | 39.9 | 38.2 | 18.6 | 34.4 | 30.7 |

| 37.1–42.8 | 35.1–42.1 | 15.5–21.8 | 32.3–36.4 | 28.4–32.9 | |

| Non–Hispanic | 32.0 | 32.1 | 17.3 | 28.6 | 26.4 |

| black | 29.0–35.0 | 28.1–36.1 | 13.7–20.9 | 26.2–31.1 | 23.2–29.7 |

| Males | 32.0 | 32.1 | 17.3 | 26.2 | 27.3 |

| 29.0–35.0 | 28.1–36.1 | 13.7–20.9 | 23.0–29.4 | 23.4–31.3 | |

| Females | 38.2 | 31.3 | 16.6 | 30.6 | 25.7 |

| 33.7–42.7 | 26.1–36.5 | 11.4–21.9 | 27.5–33.8 | 21.4–29.9 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 38.7 | 40.6 | 20.7 | 35.2 | 33.0 |

| white | 36.0–41.4 | 37.7–43.5 | 18.1–23.3 | 33.2–37.3 | 30.7–35.2 |

| Males | 35.1 | 39.0 | 23.1 | 33.8 | 32.9 |

| 31.8–38.5 | 35.3–42.6 | 20.0–26.2 | 31.6–36.0 | 30.2–35.5 | |

| Females | 42.3 | 42.3 | 18.6 | 36.8 | 33.2 |

| 38.4–46.3 | 38.6–46.0 | 15.0–22.0 | 34.2–39.5 | 30.3–36.0 | |

| Mexican | 27.1 | 26.4 | 19.6 | 25.1 | 23.8 |

| American | 23.4–30.7 | 23.4–29.4 | 17.3–21.9 | 23.0–27.2 | 21.6–26.0 |

| Males | 23.9 | 22.0 | 22.1 | 22.8 | 22.1 |

| 19.5–28.3 | 18.2–25.9 | 18.5–25.8 | 19.9–25.7 | 19.2–24.9 | |

| Females | 30.9 | 31.1 | 17.3 | 27.8 | 25.8 |

| 26.8–35.0 | 25.9–36.3 | 13.7–21.0 | 25.0–30.6 | 22.2–29.4 | |

| Other | 35.6 | 26.8 | 23.0 | 29.4 | 25.4 |

| 30.4–40.8 | 19.4–34.3 | 16.3–29.8 | 25.3–33.6 | 19.6–31.1 | |

| Males | 34.6 | 33.6 | 23.5 | 31.6 | 29.7 |

| 26.4–42.8 | 22.7–44.4 | 12.9–34.1 | 26.1–37.2 | 21.9–37.5 | |

| Females | 36.7 | 22.0 | 22.7 | 28.0 | 22.3 |

| 30.0–43.4 | 14.7–29.4 | 12.3–33.2 | 23.2–32.8 | 16.3–28.3 | |

CI: Confidence interval.

Prevalence of myopia defined as SphEq ≤−0.5D (Table 4) for ages 20–39, 40–59, and ≥60 years was 50.2% (CI, 47.8–52.7%), 50.1% (CI, 47.8–52.4%), and 26.5% (CI, 24.0–29.0%), respectively. Myopia ≤−0.5D was most prevalent in those categorized as non-Hispanic white (46.0%), compared with those categorized as non-Hispanic black (41.5%; p=0.003) or Mexican American (40.8%; p=0.0002). The prevalence of myopia ≤−0.5D did not differ significantly between males and females except in those aged 20–39 years, where the prevalence in females (53.9%) was significantly higher than in males (46.6%; p=0.0002).

Table 4.

Prevalence of myopia (≤ −0.5 diopter spherical equivalent) by race-ethnicity, gender, and age, NHANES 1999–2004.

| Prevalence and 95% CI* for ages: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–39 years |

40–59 years |

60 years and older |

20 years and older |

40 years and older |

|

| Total | 50.2 | 50.1 | 26.5 | 44.7 | 41.0 |

| 47.8–52.7 | 47.8–52.4 | 24.0–29.0 | 43.0–46.4 | 39.2–42.9 | |

| Males | 46.6 | 50.2 | 29.5 | 44.0 | 42.3 |

| 43.6–49.7 | 47.7–52.7 | 26.4–32.7 | 42.1–45.9 | 40.1–44.5 | |

| Females | 53.9 | 50.0 | 23.9 | 45.5 | 40.0 |

| 51.2–56.6 | 47.1–52.9 | 20.3–27.4 | 43.6–47.4 | 37.7–42.3 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 49.0 | 44.3 | 23.9 | 41.5 | 36.5 |

| black | 45.6–52.4 | 39.4–49.2 | 20.3–27.6 | 38.7–44.2 | 32.8–40.2 |

| Males | 43.2 | 44.6 | 26.6 | 39.8 | 37.6 |

| 37.5–48.8 | 38.8–50.3 | 22.1–31.0 | 36.2–43.5 | 33.3–42.0 | |

| Females | 53.8 | 44.2 | 22.1 | 42.9 | 35.7 |

| 49.1–58.4 | 37.5–50.8 | 16.4–27.7 | 39.2–46.5 | 30.6–40.7 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 51.3 | 52.6 | 26.4 | 46.0 | 42.6 |

| white | 48.6–54.0 | 49.8–55.4 | 23.5–29.3 | 44.0–48.0 | 40.2–44.9 |

| Males | 47.6 | 51.8 | 29.4 | 44.9 | 43.2 |

| 43.8–51.3 | 48.5–55.0 | 25.7–33.0 | 42.5–47.3 | 40.4–46.0 | |

| Females | 55.1 | 53.5 | 23.8 | 47.3 | 42.1 |

| 51.7–58.5 | 50.0–57.1 | 19.8–27.7 | 44.8–49.8 | 39.2–45.1 | |

| Mexican | 47.4 | 41.8 | 27.8 | 40.8 | 36.4 |

| American | 43.8–51.0 | 38.6–44.9 | 24.1–31.4 | 38.5–43.0 | 33.7–39.1 |

| Males | 47.0 | 38.8 | 32.0 | 40.5 | 36.2 |

| 42.1–52.0 | 34.8–42.8 | 26.7–37.4 | 37.3–43.6 | 32.5–39.8 | |

| Females | 47.8 | 45.0 | 23.9 | 41.2 | 36.9 |

| 44.0–51.8 | 40.1–49.8 | 18.9–28.9 | 38.4–44.1 | 33.3–40.4 | |

| Other | 48.8 | 42.0 | 30.2 | 41.9 | 37.4 |

| 42.0–55.5 | 33.8–50.1 | 23.5–36.9 | 37.6–46.3 | 31.6–43.2 | |

| Males | 44.8 | 50.4 | 34.1 | 44.4 | 44.1 |

| 35.2–54.3 | 39.5–61.2 | 21.6–46.5 | 38.6–50.2 | 35.7–52.5 | |

| Females | 53.0 | 36.0 | 27.5 | 40.7 | 32.7 |

| 45.6–60.3 | 27.3–44.6 | 18.1–36.9 | 35.7–45.8 | 26.7–38.8 | |

CI: Confidence interval.

Prevalence of severe myopia (SphEq ≤−5.0D) (Table 5) for ages 20–39, 40–59, and ≥60 years was 7.4% (CI, 6.5–8.3%), 7.8% (CI, 6.4–9.1%), and 3.1% (CI, 2.2–3.9%), respectively. Severe myopia was most prevalent in those categorized as non-Hispanic white (7.0%), compared with non-Hispanic blacks (4.7%; p=0.001) and Mexican Americans (3.6%; p<0.0001). The prevalence of severe myopia did not differ significantly between males and females except in those aged 20–39 years, where the prevalence in females (9.2%) was significantly higher than in males (5.6%; p<0.0001).

Table 5.

Prevalence of severe myopia (≤ −5 diopter spherical equivalent) by race-ethnicity, gender, and age, NHANES 1999–2004.

| Prevalence and 95% CI* for ages: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–39 years |

40–59 years |

60 years and older |

20 years and older |

40 years and older |

|

| Total | 7.4 | 7.8 | 3.1 | 6.5 | 6.0 |

| 6.5–8.3 | 6.4–9.1 | 2.2–3.9 | 5.8–7.2 | 5.0–6.9 | |

| Males | 5.6 | 6.8 | 3.2 | 5.5 | 5.4 |

| 4.4–6.8 | 4.9–8.6 | 2.0–4.4 | 4.6–6.4 | 4.1–6.7 | |

| Females | 9.2 | 8.8 | 2.9 | 7.6 | 6.5 |

| 7.8–10.5 | 7.3–10.3 | 1.8–4.1 | 6.8–8.4 | 5.6–7.5 | |

| Non–Hispanic | 5.5 | 5.7 | 2.0 | 4.7 | 4.3 |

| black | 3.5–7.4 | 4.0–7.4 | 0.9–3.0 | 3.7–5.8 | 3.2–5.4 |

| Males | 3.0 | 3.6 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| 1.0–4.9 | 1.7–5.6 | 0.6–4.4 | 2.1–4.1 | 2.0–4.4 | |

| Females | 7.5 | 7.4 | 1.6 | 6.1 | 5.2 |

| 4.5–10.6 | 4.5–10.4 | 0.1–3.1 | 4.5–7.7 | 3.4–7.0 | |

| Non–Hispanic | 7.9 | 8.5 | 3.0 | 7.0 | 6.4 |

| white | 6.5–9.3 | 6.7–10.4 | 2.1–4.0 | 6.0–8.0 | 5.2–7.7 |

| Males | 6.5 | 7.4 | 3.5 | 6.1 | 5.9 |

| 4.8–8.2 | 5.0–9.8 | 2.1–4.9 | 5.0–7.3 | 4.3–7.5 | |

| Females | 9.4 | 9.7 | 2.7 | 7.9 | 7.0 |

| 7.2–11.5 | 7.7–11.6 | 1.4–3.9 | 6.7–9.2 | 5.7–8.3 | |

| Mexican | 4.2 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 3.3 |

| American | 2.5–5.8 | 2.5–4.8 | 1.5–3.8 | 2.8–4.5 | 2.5–4.0 |

| Males | 2.8 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 2.0 |

| 1.6–4.0 | 0.6–2.2 | 0.7–5.2 | 1.6–3.0 | 1.0–3.0 | |

| Females | 5.9 | 6.0 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 4.6 |

| 2.9–8.9 | 3.6–8.5 | 0.9–4.0 | 3.5–6.8 | 3.2–6.1 | |

| Other | 9.1 | 6.7 | 4.6 | 7.2 | 5.9 |

| 6.6–11.6 | 2.9–10.6 | 1.1–8.2 | 5.1–9.2 | 3.2–8.6 | |

| Males | 6.0 | 8.2 | 0.5 | 5.5 | 5.2 |

| 3.2–8.9 | 1.9–14.5 | 0.0–1.5 | 3.0–8.1 | 1.3–9.1 | |

| Females | 12.3 | 5.7 | 7.5 | 8.8 | 6.4 |

| 8.4–16.3 | 1.8–9.6 | 1.6–13.4 | 6.1–11.4 | 3.2–9.6 | |

CI: Confidence interval.

Astigmatism

The prevalence of astigmatism (Table 6) increased with increasing age: for ages 20–39, 40–59, and ≥60 years, prevalence estimates were 23.1% (CI, 21.6–24.5%), 27.6% (CI, 25.8–29.3%), and 50.1% (CI, 48.2–52.0%), respectively. Prevalence of astigmatism varied little by race-ethnicity category. In those aged 60 years and older, astigmatism was more prevalent among males (54.9%) than among females (46.1%; p<0.0001).

Table 6.

Prevalence of astigmatism (≥ 1 diopter cylinder) by race-ethnicity, gender, and age, NHANES 1999–2004.

| Prevalence and 95% CI* for ages: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–39 years |

40–59 years |

60 years and older |

20 years and older |

40 years and older |

|

| Total | 23.1 | 27.6 | 50.1 | 36.2 | 31.0 |

| 21.6–24.5 | 25.8–29.3 | 48.2–52.0 | 34.9–37.5 | 30.1–32.0 | |

| Males | 24.1 | 28.4 | 54.9 | 38.6 | 32.8 |

| 22.2–26.0 | 26.0–30.8 | 52.3–57.4 | 36.8–40.3 | 31.7–33.9 | |

| Females | 22.1 | 26.8 | 46.1 | 34.2 | 29.48 |

| 20.1–24.0 | 24.6–29.0 | 43.1–49.2 | 32.3–36.1 | 28.0–30.8 | |

| Non–Hispanic | 24.5 | 29.7 | 49.8 | 37.4 | 32.3 |

| black | 21.2–27.9 | 27.2–32.3 | 44.9–54.7 | 34.8–40.1 | 30.2–34.5 |

| Males | 24.8 | 30.3 | 54.5 | 39.6 | 33.7 |

| 20.7–29.0 | 25.1–35.5 | 47.5–61.4 | 35.6–43.5 | 30.4–37.0 | |

| Females | 24.3 | 29.3 | 46.5 | 35.9 | 31.3 |

| 19.9–28.7 | 24.6–33.9 | 40.6–52.4 | 32.1–39.6 | 28.8–33.8 | |

| Non–Hispanic | 22.8 | 27.9 | 50.4 | 36.5 | 31.1 |

| white | 20.5–25.0 | 25.8–29.9 | 48.2–52.6 | 35.0–38.0 | 29.8–32.3 |

| Males | 24.3 | 28.4 | 55.5 | 38.8 | 33.1 |

| 21.5–27.2 | 25.4–31.4 | 52.8–58.2 | 36.6–40.9 | 31.6–34.6 | |

| Females | 21.2 | 27.4 | 45.9 | 34.5 | 29.2 |

| 18.4–23.9 | 24.8–30.0 | 42.4–49.4 | 32.2–36.7 | 27.4–31.0 | |

| Mexican | 21.5 | 27.1 | 51.3 | 36.4 | 30.5 |

| American | 18.8–24.2 | 24.6–29.5 | 49.0–53.6 | 34.7–38.0 | 28.7–32.3 |

| Males | 20.3 | 26.5 | 59.2 | 39.0 | 31.6 |

| 16.9–23.6 | 22.6–30.4 | 54.5–63.7 | 35.9–42.1 | 29.0–34.2 | |

| Females | 23.1 | 27.7 | 44.2 | 34.0 | 29.7 |

| 18.9–27.3 | 23.7–31.8 | 40.4–48.0 | 31.5–36.6 | 27.2–32.2 | |

| Other | 24.5 | 23.2 | 47.1 | 32.4 | 29.2 |

| 19.0–30.0 | 17.5–29.0 | 37.1–57.0 | 27.4–37.4 | 25.1–33.4 | |

| Males | 25.6 | 27.4 | 44.2 | 33.8 | 30.6 |

| 19.2–32.0 | 17.9–36.9 | 31.6–56.7 | 26.7–41.0 | 25.5–35.6 | |

| Females | 23.3 | 20.2 | 49.2 | 31.3 | 28.2 |

| 16.4–30.2 | 13.3–27.1 | 37.4–60.8 | 24.8–37.8 | 23.4–32.9 | |

CI: Confidence interval.

Any clinically important refractive error

The prevalence of any clinically important refractive error (myopia, hyperopia, and/or astigmatism) (table available online only, at www.archophthalmol.com) increased with increasing age. Prevalence estimates for ages 20–39, 40–59, and ≥60 years were 46.3% (CI, 44.5–48.0%), 50.6% (CI, 48.1–53.0%), and 62.7% (CI, 60.3–65.1%), respectively. Prevalence of any clinically important refractive error was lower for Mexican Americans (44.4%) than for non-Hispanic whites (53.4%; p<0.0001) or non-Hispanic blacks (49.3%; p=0.002). For those aged 60 years and older, the prevalence of any clinically important refractive error was higher in males (66.8%) than in females (59.2%; p=0.0003).

Discussion

We found that refractive error was common in the U.S. population aged 20 years and older: the prevalence of myopia was 33%; of severe myopia, 6.5%, of hyperopia, 3.6 %; and of astigmatism, 36%. Our estimated prevalence of myopia was higher than the 25% reported in previous U.S. studies (20,11; discussed further below) and similar (in persons aged 40 years and older) to that of ethnic Chinese persons in Singapore (12). General overall statements regarding the distribution of myopia among demographic subgroups cannot be made, since we found statistically significant interactions between age and gender (p=.0003) and between age and race/ethnicity (p=.0002), as well as a borderline statistically significant interaction between gender and race/ethnicity (p=.07). Overall, it appears that the pattern of myopia prevalence by age is similar, regardless of the definition of myopia, with nearly identical prevalence estimates within the 20–39 and 40–59-year age groups and a markedly lower prevalence for the 60+ age group (approximately half that for the younger ages). Gender differences in myopia prevalence were observed within the 20–39-year age group, where myopia (SphEq ≤−1.0D) was more prevalent in females (40%) than in males (33%; p<0.0001); the same pattern was observed for myopia defined as SphEq ≤−0.5D (p=0.0002) and for myopia defined as SphEq ≤−5.0D (p<0.0001). The prevalence of myopia ≤−0.5D was similar to that found in studies of Asian populations (12). Gender differences in refractive error prevalence were also observed within the 60+ age group, where hyperopia was more common (13% versus 7%; p<0.0001), and astigmatism less common (46% versus 66%; p<0.0001) among females than among males. Prevalence of refractive error varied by age, with those aged 60 years and older being less likely to have myopia (p<0.0001 for all myopia definitions) and more likely to have hyperopia (p<0.0001) and/or astigmatism (p<0.0001) than younger persons. Although hyperopia and astigmatism prevalence did not vary among race-ethnicity categories, myopia prevalence was higher in non-Hispanic whites than in non-Hispanic blacks (38.7% versus 28.6%; p<0.0001) or Mexican Americans (38.7% versus 25.1%; p<0.0001) (although this race-ethnicity difference was not apparent in those aged 60 years and older).

Most previous epidemiologic studies providing prevalence estimates for refractive error were limited to a specific geographic location or age group. The 1971–1972 NHANES study provided the first U.S.-wide population-based prevalence estimates for many eye conditions, including refractive error. Sperduto and colleagues (20) found that the prevalence of myopia in the U.S. in persons aged 12–54 years was approximately 25% (right eye, based on lensometry (for those with visual acuity 20/40 or better) or on retinoscopy (for those with worse visual acuity)), compared with 33.1% in the current study (in persons aged 20 years and older). The prevalence estimates for myopia are substantially higher for both non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white participants in 1999–2004 (28.6% and 35.2%, respectively) than in 1971–72 (13.0% and 26.3%, respectively). It is possible that myopia prevalence in the U.S. has increased over the 30-year period between the two NHANES studies. A previous study documented an increased prevalence of myopia over a 12-year period in young Israeli adults (21) and attributed it to a possible cohort effect. However, because of considerable differences in the methodology used to define myopia in the two NHANES studies, additional research would be required to conclude that prevalence of myopia had increased, and, if so, to explore possible reasons for such an increase.

Recently, the Eye Disease Prevalence Research Group (EDPRG) performed a meta-analysis of existing population-based studies in persons 40 years or older (conducted from 1985 – 2000) to derive robust population estimates for the prevalence of refractive error in the U.S. and in other countries (11). Definitions of hyperopia, myopia, and severe myopia were the same as in our study. Our NHANES-based estimate of prevalence of myopia in the U.S. for persons aged 40 years and older was 31.0% (CI, 29.1–32.9%), substantially higher than the EDPRG estimate for the U.S. (25.4%; CI, 24.5–26.4%). Prevalence of myopia was higher in the recent NHANES study than in the EDPRG for both non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic whites.

The prevalence of myopia ≤−0.5D in the current study was 41.0% for persons aged 40 years and older. Wong et al found a similar prevalence of myopia (38.7%) in ethnic Chinese persons living in Singapore (12). However, the prevalence of severe myopia in the current study was lower (6.0%) than that found by Wong et al (9.1%), possibly attributable to differences in the age structure of the two populations, since the U.S. may have a higher proportion of older individuals (who have a relatively lower prevalence of myopia) than Singapore. Our estimated prevalence of myopia ≤−0.5D for persons aged 60 years and older was 26.5%, greater than the 19.5% estimated from the Rotterdam study (ages 55 and older (22)). The prevalence of myopia in the Blue Mountains Eye Study was 15% (23), strikingly lower than the prevalence of myopia ≤−0.5D found in the current NHANES and that reported from the Beaver Dam Eye Study (24). The Blue Mountains and Rotterdam populations may have a different distribution of underlying risk factors for myopia that could explain their lower prevalence estimates, but we are unable to address this issue within the scope of the current study.

Our myopia prevalence estimates for non-Hispanic black participants aged 40 –59 years (32.1%; CI, 28.1–36.1%) were also higher than those reported by the Barbados Eye Study (25, conducted from 1987– 1992) for participants aged 40–59 years (9%). Our prevalence estimates for myopia in those aged 60 years and older appear comparable to those reported from the Barbados study.

The EDPRG results for Hispanic individuals were based on a single study (4) in a Mexican-American population (Proyecto Ver (Nogales, Arizona)). Recently, the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study (LALES) (26) reported prevalence estimates of myopia for Hispanic persons aged 40 years and older (over 90% of whom reported Mexican ancestry (27)). For those aged 40–59 years, the prevalence of myopia among NHANES Mexican American participants was higher than their LALES and EDPRG counterparts. For those aged 60 years and older, NHANES and LALES prevalences were similar and higher than those from the EDPRG.

It is not possible for us to compare results for “other” race-ethnicity with previous studies, because this category includes participants with a wide range of ancestries and NHANES does not provide data to allow further differentiation within this subgroup. However, since the NHANES sample as a whole is designed to represent the entire U.S. population, it is important to include the “other” subgroup in calculating estimates for the entire U.S. population.

We found that the prevalence of myopia was lowest in participants aged 60 years and older, consistent with other population-based studies (28, 29). Although it is possible that the lower prevalence of myopia in those aged 60 years and older is due to a cohort effect, as reported in other, younger populations (21, 30), this observation may also be due to intrinsic, age-related changes in the refractive components of the eye (31,32).

The observed lower prevalence of myopia in persons aged 60 years and older may also be due in part to an association of cataract surgery (a criterion for exclusion) with myopic refractive status (33). Because we have no information on the refractive status of participants prior to cataract surgery, we are unable to explore this hypothesis.

Our study has several important limitations. Because of time constraints and potential for participant fatigue, we could not perform a full ophthalmic exam on all participants in the MEC. Our study protocol therefore included the use of an autorefractor, operated according to a standard protocol by trained operators. Our non-cycloplegic refraction values were based on the mean of three measurements by the autorefractor and did not include subjective refinement. This may have resulted in over-estimates of the true number with myopia (34), especially among younger participants, who have a higher amplitude of accommodation. Because of this concern we did not use the NHANES 1999–2004 data to provide prevalence estimates of refractive error for those aged 12–19 years.

As in the EDPRG, we categorized participants based on the refractive characteristics of the eye with greater absolute value SphEq, resulting in an estimated myopia prevalence of 32.99% (CI, 31.47–34.52%, based on 5709 individuals). If we had considered an individual as myopic if either eye was myopic (35), we would have classified an additional 15 participants as myopic, resulting in a prevalence of 33.05 % (CI, 31.52–34.58%).

Although the NHANES sampling weights correct for non-response within population subgroups, it is possible that NHANES participants who had vision data had different refractive characteristics than those who did not. Response rates to the home interview and MEC examination were lower in older individuals (36). Participants who reported for the MEC examination may have had missing vision data due to equipment malfunction or inability to cooperate with the examination.

Because refractive error’s impact on visual acuity can be mitigated relatively easily, it has sometimes been overlooked as an important cause of visual impairment (37,38). Many previous epidemiologic studies based definitions of visual impairment on best-corrected, rather than presenting (i.e., with habitual correction) visual acuity (39). However, newer research has focused attention on the benefits of correcting refractive error (40,41). A recent analysis found that a substantial proportion of the economic burden posed by vision disorders is due to refractive error, concluding: “… interventions to diagnose and treat uncorrected refractive error have the potential to be highly cost-effective based on the improvements in patient quality of life they generate” (7).

In summary, the NHANES 1999–2004 data show that half of the U.S. population aged 20 years and older has some type of clinically important refractive error. Refractive error is therefore the most common condition affecting the ocular health of the U.S. population, involving young adults, middle-aged persons, and older adults of all ethnicities. In our previous study (6) we estimated the annual direct cost of providing refractive correction to the 100 million people who need it to achieve good vision as exceeding $3.5 billion (not including the costs of identifying those who need refractive correction). Others estimated the economic burden (including indirect costs) of refractive error in those aged 40 years and older to be $5.5 billion (7). Accurate, current estimates of the prevalence of refractive error are essential for projecting vision care needs and planning for delivery of vision care services to the large number of people affected.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The NHANES is sponsored by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Additional funding for the NHANES Vision Component was provided by the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health (Intramural Research Program grant Z01EY000402). The authors have no financial interest in any aspect of this research.

Role of the Sponsor: NCHS provided funding support for the NHANES and was involved in the design, management, and conduct of the study and in data collection, but was not involved in the analysis or interpretation of the vision examination study results or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The National Eye Institute provided funding support for the vision examination and was involved in the design and conduct of the vision component, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the vision data, and in the preparation, review, and approval of this article before submission.

We thank the staff of the National Center for Health Statistics at the, National Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, especially Brenda G. Lewis, BS, ASCP, MPH, for their expert assistance with all technical aspects of the vision component; the staff at Westat, Inc, especially Kay Apodaca, BA, MSW, and Beryl D. Carew, MPH, BN, for their role with data collection activities; Susan K. Corwin, CO, COMT for training field staff; and the participants in NHANES, without whose time and dedication this study would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Vitale had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Vitale, Sperduto. Acquisition of data: Vitale, Cotch, Ferris. Analysis and interpretation of data: Vitale, Ellwein, Cotch, Ferris, Sperduto. Drafting of the manuscript: Vitale. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Vitale, Ellwein, Cotch, Ferris, Sperduto. Statistical analysis: Vitale.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no financial interest in any aspect of this research.

References

- 1.Evans BJ, Rowlands G. Correctable visual impairment in older people: a major unmet need. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2004;24:161–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2004.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munoz B, West SK, Rubin GS, et al. Causes of blindness and visual impairment in a population of older Americans. The Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:819–825. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chia E-M, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, Smith W, Cumming RR, Mitchell P. Impact of bilateral visual impairment on health-related quality of life: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:71–76. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munoz B, West SK, Rodriguez J, et al. Blindness, visual impairment and the problem of uncorrected refractive error in a Mexican-American population: Proyecto VER. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:608–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitale S, Cotch MF, Sperduto RD. Prevalence of visual impairment in the United States. JAMA. 2006;295:2158–2163. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vitale S, Cotch MF, Sperduto RD, Ellwein L. Costs of refractive correction of distance vision impairment in the United States, 1999–2002. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2163–2170. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rein DB, Ping Zhang P, Wirth KE, et al. The economic burden of major adult visual disorders in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1754–1760. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Center for Health Statistics: Plan and operation of the HANES I augmentation survey of adults 25–74 Years, United States, 1974–1975. Series l, No. 14. DHEW Publication No. PHS 78-1314. Public Health Service. Washington, D.C. U.S. Government Printing Office; Vital and Health Statistics. 1978 June; [PubMed]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) [Accessed 16 February 2005];Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. 1999–2004 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/datalink.htm.

- 10.Waksberg J, Levine D, Marker D. [Accessed 5 July 2007];U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; Assessment of major federal data sets for analyses of Hispanic and Asian or Pacific Islander Subgroups and Native Americans, Appendix B: Inventory of selected existing federal data bases. 2000 May; http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/minority-db00/task2/APP-B.HTM#nhanes.

- 11.Kempen JH, Mitchell P, Lee KE, et al. The prevalence of refractive errors among adults in the United States, Western Europe, and Australia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:495–505. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong TY, Foster PJ, Hee J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors in adult Chinese in Singapore. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2486–2494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malec D, Davis WW, Cao X. Model-based small area estimates of overweight prevalence using sample selection adjustment. Stat Med. 1999;18:3189–3200. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19991215)18:23<3189::aid-sim309>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [Accessed 27 July 2007];Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004; Analytic guidelines. 2004 June; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_general_guidelines_june_04.pdf.

- 15.Graubard BI, Fears TR. Standard errors for attributable risk for simple and complex sample designs. Biometrics. 2005;61:847–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [Accessed 27 July 2007];Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002; NHANES 1999–2000 addendum to the NHANES III analytic guidelines. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/guidelines1.pdf.

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [Accessed 27 July 2007];Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1996; Analytic and reporting guidelines: the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, NHANES III (1988–94) 1996 October; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes3/nh3gui.pdf.

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [Accessed 27 July 2007];Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006; Analytic and reporting guidelines. 2006 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/nhanes_analytic_guidelines_dec_2005.pdf.

- 19.Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics; Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. Healthy People 2010 Statistical Notes, No. 20. 2001 January; [PubMed]

- 20.Sperduto RD, Seigel D, Roberts J, Rowland M. Prevalence of myopia in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:405–407. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040010405011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dayan YB, Levin A, Morad Y, et al. The changing prevalence of myopia in young adults: a 13-year series of population-based prevalence surveys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2760–2765. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikram MK, van Leeuwen R, Vingerling JR, Hofman A, de Jong PT. Relationship between refraction and prevalent as well as incident age-related maculopathy: the Rotterdam Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3778–3782. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Attebo K, Ivers RQ, Mitchell P. Refractive errors in an older population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1066–1072. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Q, Klein BEK, Klein R, Moss SE. Refractive status in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:4344–4347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu SY, Nemesure B, Leske MC. Refractive errors in a black adult population: the Barbados Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2179–2184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarczy-Hornoch K, Ying-Lai M, Varma R, Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group Myopic refractive error in adult Latinos: The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1845–1852. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varma R, Paz SH, Azen SP, Klein R, et al. The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study: design, methods, and baseline data. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shufelt C, Fraser-Bell S, Ying-Lai M, et al. Refractive error, ocular biometry, and lens opalescence in an adult population: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4450–4460. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee KE, Klein BE, Klein R. Changes in refractive error over a 5-year interval in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1645–1649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rose K, Smith W, Morgan I, Mitchell P. The increasing prevalence of myopia: implications for Australia. Clin Exper Ophthalmol. 2001;29(3):116–120. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2001.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mutti DO, Zadnik K. Age-related decreases in the prevalence of myopia: longitudinal change or cohort effect? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2103–2107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hemenger RP, Garner LF, Ooi CS. Change with age of the refractive index gradient of the human ocular lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:703–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Younan C, Mitchell P, Cumming RG, Rochtchina E, Wang JJ. Myopia and incident cataract and cataract surgery: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3625–3632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao J, Mao J, Luo R, Li F, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB. Accuracy of noncycloplegic autorefraction in school-age children in China. Optom Vis Sci. 2004;81:49–55. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Negrel AD, Maul E, Pokharel GP, Zhao J, Ellwein LB. Refractive Error Study in Children: sampling and measurement methods for a multi-country survey. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:421–426. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [Accessed 27 July 2007];Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Weighted and unweighted response rates for NHANES by gender and age. 2007

- 37.Dandona L, Dandona R. What is the global burden of visual impairment? BMC Med. 2006;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carden SM. Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Comment on "Prevalence of visual impairment in the United States". Surv Ophthalmol. 2006;51:525–526. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dandona L, Dandona R. Revision of visual impairment definitions in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases. BMC Med. 2006:4–7. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coleman AL, Yu F, Keeler E, Mangione CM. Treatment of uncorrected refractive error improves vision-specific quality of life. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2006;54(6):883–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Owsley C, McGwin G, Jr, Scilley K, Meek GC, Seker D, Dyer A. Effect of refractive error correction on health-related quality of life and depression in older nursing home residents. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:1471–1477. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.11.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.