Abstract

Using a multisite community sample of 585 children, this study examined how protective and vulnerability factors alter trajectories of teacher-reported externalizing and internalizing behavior from kindergarten through Grade 8 for children who were and were not physically abused during the first 5 years of life. Early lifetime history of physical abuse (11.8% of sample) was determined through interviews with mothers during the prekindergarten period; mothers and children provided data on vulnerability and protective factors. Regardless of whether the child was abused, being African American; being male; having low early social competence, low early socioeconomic status (SES), and low adolescent SES; and experiencing adolescent harsh discipline, low monitoring, and low parental knowledge were related to higher levels of externalizing problems over time. Having low early social competence, low early SES, low adolescent SES, and low proactive parenting were related to higher levels of internalizing problems over time. Furthermore, resilience effects, defined as significant interaction effects, were found for unilateral parental decision making (lower levels are protective of externalizing outcomes for abused children), early stress (lower levels are protective of internalizing outcomes for abused children), adolescent stress (lower levels are protective of internalizing outcomes for abused children), and hostile attributions (higher levels are protective of internalizing outcomes for abused children). The findings provide a great deal of support for an additive or main effect perspective on vulnerability and protective factors and some support for an interactive perspective. It appears that some protective and vulnerability factors do not have stronger effects for physically abused children, but instead are equally beneficial or harmful to children regardless of their abuse status.

Research indicates that individuals who have been physically abused early in life are at greater risk than are their nonabused peers for demonstrating externalizing behaviors such as aggression (Lansford et al., 2002), conduct disorders (Lynch & Cicchetti, 1998), and delinquency (Stouthamer-Loeber, Loeber, Homish, & Wei, 2001). It also demonstrates that physically abused children are at greater risk for displaying internalizing emotional distress including symptoms of depression (Toth, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1992), anxiety (Johnson et al., 2002), and maladaptive peer relationships (Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1997).

Despite the developmental risks of physical abuse, several studies suggest that some individuals exposed to early childhood abuse are able to develop with few if any difficulties (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1997; Cicchetti, Rogosch, Lynch, & Holt, 1993; Egeland & Farber, 1987; Luthar, 1991; Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; McGloin & Widom, 2001; Moran & Eckenrode, 1992). Why are some children able to develop well despite experiencing negative events in early childhood? What is it about individuals and their environment that aids them in overcoming their negative life experiences? How can such characteristics be promoted in individuals who lack them to improve their developmental outcomes? Answering these questions could lead to the development of effective preventive-intervention strategies that promote the well-being of children and families at risk for physical abuse.

Early research attempting to shed light on this topic used the terms invulnerable and invincible to describe children who continued along a positive developmental trajectory despite facing considerable adversity (Anthony, 1974). These researchers attributed positive developmental outcomes to personality or coping styles that seemed, to make some children, but not others, resistant to risk conditions. This emphasis on individual invulnerability and invincibility is problematic for several reasons: (a) the terms invulnerability and invincibility imply an absolute resistance to damage, (b) they imply that the characteristic applies to all risk conditions, (c) the terms imply that the concept is an intrinsic characteristic of the child, (d) the terms suggest that the characteristic is static (Rutter, 1985), and (e) labeling children as invulnerable or invincible implies that they are fundamentally different from other children (Cowen et al., 1997).

In an attempt to resolve these problems, researchers have suggested the use of the term resilience. Luthar et al. (2000) define resilience as a dynamic process wherein an individual displays positive adaptation despite experiences of significant adversity or trauma. Inherent within this definition of resilience are multiple domains of functioning and a temporal dimension, which allows for more than a snapshot of individuals' adaptation throughout their development (Luthar et al., 2000). Although this definition is widely accepted by resilience researchers, there is still variability in how the construct is operationalized across studies (Kaplan, 1999; Luthar et al., 2000; McGloin & Widom, 2001).

Protective and Vulnerability Factors

Much of the research on resilience has centered on identifying and understanding the interplay of protective and vulnerability factors and the developmental outcomes of children exposed to various types of negative life events, including physical abuse (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993; Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000). Following Luthar et al. (2000), we construe protective and vulnerability factors as characteristics of children and their environments that respectively diminish or increase the probability of poor outcomes, One might expect the importance of particular protective and vulnerability factors in promoting resilience to depend on the type of negative life event a child has experienced. The key developmental issues facing a child who has been physically abused may be quite different from the key developmental issues facing a child who has experienced a natural disaster or witnessed a crime. Therefore, the kinds of protective and vulnerability factors that promote resilience in these children may also differ.

At least two key developmental issues are likely to face children who have been physically abused. First, because these children have been hurt by an adult, they may have difficulty trusting the abusive adult or other adults in the future. An important developmental task would be to overcome a lack of trust to be able to form positive social relationships with others. When a child has been abused by an adult with whom he or she continues to live, the task may be even harder because the child would have to continue to rely on this adult to provide for his or her needs and might be fearful about the possibility of being abused again in the future. Second, because these children have been treated aggressively, they may have difficulty learning not to behave aggressively. Dodge, Bates, and Pettit (1990) demonstrated that children who have been physically abused have biased ways of processing social information, and these biases mediate the association between being physically abused and behaving aggressively. Thus, an important developmental task would be to learn to interpret the behaviors of others in less biased ways and to learn not to behave aggressively. Protective and vulnerability factors that help physically abused children to manage these key developmental issues are likely to promote resilience.

Two primary models have been proposed to explain how multiple protective and vulnerability factors relate to each other to influence developmental outcomes. The additive, or “main effect,” model holds that factors cumulate to enhance either protection or risk. For example, a child who is physically abused and living in poverty and exposed to community violence is at greater risk for negative developmental outcomes than is a child with fewer of these vulnerability factors. An alternative approach is the interactive model, which presupposes interactions between protective and vulnerability factors and an adversity condition such as abuse. Resilience models, in Luthar et al.'s (2000) framework, refer to interactive effects by which a protective factor results in enhanced outcomes given some adversity condition.

Vulnerability and protective factors can derive from several levels of influence, with a broad conceptual distinction between child characteristics (e.g., social competence, social cognitive functioning) and factors external to the child (e.g., characteristics of the family and parenting). In terms of the child's own characteristics, social competence serves as a buffer between early negative experiences and later negative developmental outcomes (Chen, Li, Li, Li, & Liu, 2000; Luthar, 1991). Children who demonstrate the ability to navigate through the social world, by developing friendships (Ladd, Kochenderfer, & Coleman, 1997) and successfully finding solutions to social problems (Lochman & Wells, 2002), are better able to avoid negative outcomes than are their less socially competent peers. For abused children, social competence may be especially important if it enables them to form trusting and positive relationships with others. On the other hand, children who demonstrate hostile attribution biases (i.e., interpret ambiguous behaviors of others as having hostile intent) are at greater risk for developing externalizing problems (Dodge, Price, Bachorowski, & Newman, 1990). For abused children, hostile attributions have been found to mediate the link between experiencing abuse and subsequently behaving aggressively (Dodge et al., 1990). The gender (Maccoby, 1990) and ethnicity (Ogbu, 1985) of the child also play a role in later development and adjustment and have been found to moderate the association between a number of vulnerability factors and developmental outcomes; for example, there is some evidence that experiencing physical abuse is more related to behavior problems for African American than European American children (Lansford et al., 2002).1

Several studies have examined how characteristics of individual children serve as protective factors for children who have been abused. For example, Moran and. Eckenrode (1.992) found that personality characteristics interacted with abuse status in predicting depression of adolescent females. In a prospective study of maltreated and nonmaltreated children, McGloin and Widom (2001) found that females who had been maltreated during childhood were more likely as adults to demonstrate resilience (defined as meeting criteria for success in at least six of eight important domains of functioning such as employment and psychiatric disorder) than were males who had been maltreated. Females also were found to demonstrate resilience across a larger number of functional domains. Recent evidence suggests that a specific genetic factor that confers high levels of monoamine oxidase A expression protects against the development of antisocial behaviors for boys who experience abuse during childhood (Caspi et al., 2002; Foley et al., 2004).

In terms of factors external to the child, family poverty (McLoyd, 1998) and stress (Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz, & Simons, 1994) have clear, negative impact on children's developmental outcomes. Researchers have also noted that children living in dangerous neighborhoods are at greater risk for developing externalizing and internalizing problems (e.g., Attar, Guerra, & Tolan, 1994). Parenting behaviors are also important examples of protective and vulnerability factors. These include positive parenting (Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 1997) and parental monitoring (Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992), which appear to be protective factors, and physical discipline (Gershoff, 2002) and unilateral parental decision making during adolescence (Lansford, Criss, Pettit, Dodge, & Bates, 2003), which seem more likely to be vulnerability factors.

Overall, research supports the intuitive claim that children who have positive relationships with their parents have far better outcomes than children whose relationships with their parents are marked by negative interactions (e.g., Darling & Steinberg, 1993). However, the more relevant question for the present study is how parenting and similar environmental factors may act as protective or vulnerability factors specifically for children who have been physically abused. In a longitudinal study of children from socioeconomically disadvantaged families, Cicchetti and Rogosch (1997) found that factors external to the child (in particular, characteristics of social relationships such as emotional availability of the mother and positive relationships with other adults) were important predictors of adaptive functioning for nonmaltreated children, but not for maltreated children. In contrast, for maltreated children, factors internal to the child (ego resilience, ego overcontrol, and positive self-esteem) were more important predictors of adaptive functioning.

In terms of key developmental tasks (e.g., overcoming a lack of trust to be able to form positive social relationships with others, learning not to behave aggressively) facing physically abused children, living in a dangerous neighborhood may pose an additional risk both in terms of providing more aggressive role models who demonstrate the aggressive behavior for which abused children are at risk and in terms of not providing a community context that fosters trust. The constellation of parenting behaviors that physically abused children experience may be important in shaping whether the child comes to trust his or her parents or other adults following the abuse. Clearly, it is important to study multiple pathways that children and adolescents take toward adaptive outcomes and whether these pathways differ for children who have and have not been maltreated (Cicchetti et al., 1993).

Direction of This Study

Cicchetti and Garmezy (1993) cautioned that empirical research on resilience is needed to keep up with theoretical discussions of its importance as a construct. Although a large body of research has focused on identifying and documenting vulnerability and protective factors, few studies have implemented a multimethod, multiple informant longitudinal design to provide rigorous tests of the efficacy of these protective and vulnerability factors over time. The current study follows a large, community sample of children prospectively for 9 years. One previous study using these data (Keiley, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, 2000) used cross-domain latent growth modeling to examine effects of race, socioeconomic status (SES), gender, and peer rejection on trajectories of mother-reported and teacher-reported adjustment, as defined by intercepts and slopes of externalizing and internalizing behavior trajectories over time; each of these factors was found to affect the developmental trajectories of children's behavior problems. A second study using these data (Keiley, Howe, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 2001) employed growth curve modeling techniques to look at the differential effects of early childhood and later childhood abuse on developmental trajectories of internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Children who experienced physical abuse in the first 5 years of life were found to be at greater risk of developing externalizing and internalizing behavior problems than were children who experienced physical abuse after the first 5 years of life. The current study attempts to take this previous work a step further by exploring the main effects of specific protective and vulnerability factors on trajectories of internalizing and externalizing problems and the moderating effects of these protective and vulnerability factors on the trajectories of children who were and were not physically abused.

The guiding principles in the selection of particular protective and vulnerability factors to include in the models were that these factors had been found in previous research to be importantly related to children's internalizing and externalizing behavior problems and that there be a strong conceptual rationale for believing they could moderate the effects of physical abuse on trajectories of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems over time. For example, previous research has suggested that hostile attribution biases mediate the effects of physical abuse on subsequent externalizing behaviors; children who have been physically abused are more likely to attribute hostile intentions to others in ambiguous social situations, and making hostile attributions is, in turn, predictive of externalizing behaviors (Dodge et al., 1990). It is also possible that hostile attributions would moderate the effects of abuse on trajectories of behavior problems. Nonabused children may have elevated trajectories of externalizing behaviors if they tend to make hostile attributions, but the link between abuse and externalizing problems may be amplified for abused children who also make hostile attributions. The same pattern may be found with internalizing behaviors.

For the other selected moderators as well, we would expect experiencing an additional vulnerability factor to exacerbate the effects of physical abuse early in life, whereas experiencing a protective factor would mitigate the effects of physical abuse on trajectories of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. In particular, proactive parenting, adolescent harsh discipline, parental decision making, monitoring, and parental knowledge all may be important for abused children because these are aspects of parent–child relationship quality that may be relevant to children's formation of close and caring relationships with adults, which is a key developmental task for children who have been physically abused. As described above, another key developmental task for children who have been physically abused is to learn not to behave aggressively, a challenge because these children have been treated aggressively by an adult. Early social competence may be especially protective for physically abused children because this characteristic might offer abused children more options than aggression for responding to social situations; neighborhood danger may work in the opposite direction by providing abused children with more aggressive models that may increase the risk of abused children's future aggressiveness. SES and family-level stress during childhood and adolescence provide insight into contexts in which abused children and their families are situated. These contexts are related both to the quality of parent–child relationships and to resources outside the family to which children would have access, and may thus be particularly important for children who have been physically abused.

Protective and vulnerability factors were measured at points in time when they were believed to have the most important consequences for children's development. SES and stress were assessed during childhood as well as adolescence because they were expected to be important across different developmental periods; separate variables were constructed to reflect early versus later indicators of these constructs because it was possible that their effects would vary over time. Other constructs were assessed at times when the developmental literature suggests they are most salient to children's adjustment and family functioning. For example, monitoring, parental knowledge, and unilateral parental decision making were assessed in early adolescence when parents have less direct control over their-children, distal forms of supervision become more important, and adolescents generally begin making more of their own decisions. Similarly, neighborhood danger was assessed in early adolescence because as adolescents spend more time with peers during this developmental stage, dangerous neighborhoods are likely to present adolescents with opportunities to engage in risky behaviors that were less salient earlier in their development, which may have implications for their externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Although hostile attributions may be important across different developmental stages, we included a measure from childhood so it would be temporally closer to the time of the abuse, which has been shown to affect children's hostile attributions (Dodge et al., 1990).

To summarize, the goal of the current study is to illuminate the consequences protective and vulnerability factors have for developmental trajectories of children abused early in life. This study addresses the following questions: (a) what are the normative main effects of protective and vulnerability factors on behavior problem trajectories for children who were not physically abused during the first 5 years of life? (b) In what ways do protective and vulnerability factors moderate the association between early physical abuse and trajectories of externalizing and internalizing behaviors? Modeling differential effects of vulnerability and protective factors on externalizing versus internalizing behavior problems has not been as central a focus of previous research on sequelae of child abuse as it is in the current study.

Method

Participants

The families in the current investigation were participants in a multisite longitudinal study of socialization (Dodge et al., 1990; Pettit et al., 1997). Participants were recruited when the children entered kindergarten in 1987 or 1988 at three sites; Knoxville and Nashville, TN, and Bloomington, IN. Parents were approached at random during kindergarten preregistration and asked if they would participate in a longitudinal study of child development. About 15% of children at the targeted schools did not preregister. These participants were recruited on the first day of school or by letter or telephone. Of those asked, approximately 75% agreed to participate: The sample consisted of 585 families at the first assessment. Males comprised 52% of the sample. Eighty-one percent of the sample were European American, 17% were African American, and 2% were from other ethnic groups. Follow-up assessments were conducted annually through Grade 8. Eighty-two percent of the original sample had at least partial data available for Grade 8; abused and nonabused children were equally likely to have available data in Grade 8, χ2(1, N = 585) = 1.68, p > .10.

Procedures and measures

During the summer before children started kindergarten or within the first weeks of school, in-depth interviews were conducted with mothers and children in their homes. Mothers completed additional interviews and questionnaires annually thereafter. Children completed additional interviews when they were in first, second, seventh, and eighth grades. Finally, children's teachers in kindergarten through eighth grade completed questionnaires. Summaries of measures along with descriptive statistics are provided in Tables 1 and 2; bivariate correlations are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Bivariate correlations.

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Abused | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. Ethnicity | .09 | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Gender | .02 | −.03 | — | |||||||||||||||

| 4. Early social competence | −.19 | −.16 | −.20 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 5. Early hostile attributions | .10 | .28 | .01 | −.12 | — | |||||||||||||

| 6. Early SES | −.21 | −.40 | .05 | .32 | −.18 | — | ||||||||||||

| 7. Adolescent SES | −.20 | −.39 | .06 | .27 | −.23 | .75 | — | |||||||||||

| 8. Early stress | .19 | .01 | .03 | −.13 | .02 | −.21 | −.24 | — | ||||||||||

| 9. Adolescent stress | .18 | .06 | −.01 | −.16 | .10 | −.20 | −.21 | .54 | — | |||||||||

| 10. Neighborhood danger | .19 | .42 | −.04 | −.19 | .24 | −.40 | −.40 | .11 | .18 | — | ||||||||

| 11. Proactive parenting | −.07 | −.10 | .00 | .15 | .01 | .19 | .17 | −.02 | −.04 | −.11 | — | |||||||

| 12. Adolescent harsh discipline | .16 | .27 | .06 | −.25 | .20 | −.29 | −.30 | .14 | .17 | .31 | −.11 | — | ||||||

| 13. Parental decision making | −.07 | −.21 | −.10 | .15 | −.21 | .13 | .12 | −.05 | −.03 | −.20 | .04 | −.28 | — | |||||

| 14. Monitoring | −.14 | −.29 | −.11 | .24 | −.13 | .28 | .22 | −.06 | −.16 | −.26 | .12 | −.22 | −.02 | — | ||||

| 15. Parental knowledge | −.09 | −.16 | −.08 | .22 | −.06 | .23 | .24 | −.13 | −.11 | −.21 | .06 | −.17 | .12 | .25 | — | |||

| 16. Externalizing kindergarten | .19 | .07 | .14 | −.55 | .09 | −.23 | −.19 | .11 | .12 | .10 | −.12 | .22 | −.05 | −.17 | −.10 | — | ||

| 17. Externalizing 8th grade | .18 | .23 | .15 | −.40 | .08 | −.33 | −.29 | .07 | .15 | .23 | −.09 | .23 | −.04 | −.33 | −.21 | .29 | — | |

| 18. Internalizing kindergarten | .10 | .01 | .02 | −.14 | .03 | −.12 | −.14 | .07 | .06 | .03 | −.08 | .10 | −.02 | .06 | −.09 | .15 | .01 | — |

| 19. Internalizing 8th grade | .11 | .07 | −.04 | −.23 | −.03 | −.18 | −.18 | .12 | .11 | .10 | .00 | .03 | .07 | .14 | .16 | .19 | .39 | .13 |

Abuse status

During the interview before children started kindergarten, mothers responded to a variety of questions regarding the child's misbehavior, their own discipline practices, and whether the child had ever been physically harmed by an adult. Following this discussion, interviewers paused to rate privately the probability that the child had been severely harmed, using a criterion of intentional strikes to the child by an adult that left visible marks for more than 24 hr or that required medical attention. A score of 0 was assigned if abuse had definitely not or probably not occurred, and a score of 1 was assigned if abuse had probably occurred, definitely occurred, or if authorities had been involved. Agreement between independent raters for this classification was 90% (κ = .56; Dodge, Pettit, Bates, & Valente, 1995). Sixty-nine children (11.8% of the sample) were classified as having experienced early physical abuse, a rate comparable to other reports using national samples (e.g., Straus & Gelles, 1990); however, because of parents' reluctance to report, this is likely an underestimate of the proportion of children who had actually experienced physical abuse (see National Research Council, 1993). All parents signed statements of informed consent before participating in the study and were aware that cases of abuse made known to the researchers would be reported as appropriate. Each child classified as abused was discussed with experts from relevant local agencies to determine which cases should be reported to the Department of Human Services. Authorities had been involved with 7 of the 69 children classified as physically abused, and six new cases were reported to agencies; the other cases were determined not to be cases of ongoing abuse and imminent danger (and thus were not reportable in Tennessee and Indiana at that time).

Child characteristics

Two variables were used as indicators of child characteristics. First, children's teachers in kindergarten, first, and second grades rated the children's skills in seven domains: understanding others' feelings, being socially aware of what is happening in a situation, accurately interpreting what a peer is trying to do, refraining from overimpulsive responding, generating many solutions to interpersonal problems, generating good quality solutions to interpersonal problems, and being aware of the effects of their behavior on others. Teachers rated each item on a 5-point scale (1 = very poor, 5 = very good). Items were averaged across the three grades to create a measure of early social competence (α = .96).

Second, when children were in kindergarten, first, second, and third grades, they were presented with 8 cartoon stories depicting negative outcomes (e.g., being bumped by a peer and spilling a drink; asking peers to play and having them say no; Dodge et al., 1995). In each story, the peers' intentions were ambiguous. Following the presentation of each story, the child was asked to indicate why the peers acted the way they did. The child's responses were coded by the interviewer as attributing benign (coded as 0) or hostile (coded as 1) intent to the peer in the story. Interrater agreement in these ratings has been found to be high (Dodge, Pettit, McClaskey, & Brown, 1986). To create a composite variable reflecting the child's hostile attributional bias, responses were averaged across the eight stories, standardized within year, averaged across the 4 years, and restandardized (α = .73; see Dodge et al., 1995).2

Factors external to the child

Five variables were used as indicators of family context. First, a measure of early SES was based on the Hollingshead (1979) Four-Factor Index of Social Status computed from parental education and occupation levels when the child was in kindergarten. Second, a comparable measure of adolescent SES was based on the Hollingshead Index computed from parental education and occupation levels averaged across years when the child was in fifth through eighth grades. Third, in each year, mothers were asked whether they had experienced each of 15 major stressors (e.g., death of a family member, divorce). An index of family early stress was created by averaging responses to these questions (each rated 0 = had not occurred, 1 = had occurred; see Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1994) across the 5-year period from the time the child was in kindergarten through fourth grade. Fourth, an index of family adolescent stress was the average across the 4-year period from the time when the child was in fifth grade through eighth grade. Fifth, when children were in sixth grade, their mothers answered six questions about neighborhood danger adapted from the Self-Care Checklist (see Pettit, Bates, Dodge, & Meece, 1999; Posner & Vandell, 1994). Mothers were asked the following: “How safe (a) is your neighborhood, (b) do you feel coming home alone, (c) do you think it is for your child to play outside when you are not at home, (d) do you feel your child is playing outside when you are at home, (e) do you feel while you are in your house alone, and (f) do you feel walking in your neighborhood alone?” (1 = very safe, to 6 = very unsafe). Responses were averaged to create a scale (α = .90).

Five variables were used as indicators of parenting behaviors. First, proactive parenting was assessed before the child started kindergarten through interviewer ratings of mothers' reports on the Concerns and Constraints interview (see Pettit et al., 1997). Mothers were presented with five hypothetical vignettes that described a child's misbehavior (e.g., losing a race and calling the winner a bad name, teasing a peer about being dumb). Mothers were then asked a series of questions about what they would do if their child behaved in this manner and what they could do to prevent their child from misbehaving that way in the future. On the basis of mothers' responses regarding prevention, the interviewer rated the responses to each vignette on a 5-point scale (1 = do nothing, is unpreventable, 5 = preventable, anticipatory, situation specific). An average score across the five vignettes was created (α = .63).

Second, when adolescents were in Grades 6 and 8, mothers completed an oral and written interview during which they were asked how often during the last year they dealt with their child's misbehavior by using physical discipline including (a) slapping or hitting with their hand, (b) spanking, and (c) using a belt or paddle. The frequency of each of these three types of discipline was rated on a 4-point scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = frequently); the items were averaged to create a scale reflecting adolescent harsh discipline (α = .79).

Third, a measure of unilateral parental decision making based on an instrument developed by Steinberg, Elmen, and Mounts (1989) was used when the adolescent was in sixth grade to assess the degree to which the parent made decisions for the adolescent concerning daily activities (e.g., how to spend money, what to eat, which movies to see). Parents rated 16 items on a 4-point scale (1 = child decides, 2 = joint decision, 3 = discuss but parent has final say, 4 = parent decides; Lansford et al., 2003). Items were averaged to create the final unilateral parental decision making score (α = .72).

Fourth, a measure of parent-reported monitoring was created by averaging nine items (α = .71; see Pettit et al., 1999), which were adapted from other similar measures of parental monitoring (Brown, Mounts, Lamborn, & Steinberg, 1993; Capaldi & Patterson, 1989; Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, & Skinner, 1991). The scale anchors differed somewhat across items, but each was rated using a 5-point scale. When their child was in sixth grade, mothers were asked to rate how much they knew about the child's friends and activities, how difficult it was to track their child's whereabouts, and the likelihood of adult supervision at the homes of the child's friends.

Fifth, when they were in seventh and eighth grades, children were asked how much their parents really know about who their friends are, how they spend their money, where they are after school, where they are at night, and what they do with free time (1 = they don't know, 2 = they know a little, 3 = they know a lot). A measure of parental knowledge was created by averaging responses to these items (α = .80).

Internalizing and externalizing behaviors

Children's teachers each year in kindergarten through Grade 8 completed the 113-item Teacher Report Form of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986). Teachers reported whether each item was not true (0), somewhat or sometimes true (1), or very or often true (2) of the child. Items were summed to create separate scales reflecting internalizing and externalizing behavior problems in each year.

Results

Overview

Analyses were conducted in two parts, addressing the different research questions. In each part, models were fit separately for the two outcomes, externalizing and internalizing behavior. First, the normative main effects of the selected predictors were examined in the non-abused sample. Second, the differential effects of the predictors in the two groups were tested, enabling an examination of the interaction between abuse and different child and family characteristics and the detection of resilience effects.

Sample characteristics and missing data

Sixty-nine (11.8%) of the 585 respondents were classified as abused. Nineteen percent (19%) of African American target children were in the abused group; 10% of non-African American target children were in the abused group, χ2 (1, N = 585) = 5.11, p < .03. Twelve percent (1.2%) of male children were abused; 11% of female children were abused, χ2 (1, N = 585) = .30, p > .10. Seven percent (7%) of children whose biological parents were married when the child was in kindergarten were abused; 19% of children whose biological parents were not married when the child was in kindergarten were abused, χ2 (1, N = 585) = 15.90, p < .001. Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and sample sizes of the continuous predictor variables in the abused and nonabused groups; Table 2 presents the same information for teacher-rated externalizing and internalizing behavior scores at each year.

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

| Nonabused | Abused | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | M | SD | n | M | SD | n |

| Child characteristics | ||||||

| Early social competence* | 3.40 | 0.75 | 513 | 2.94 | 0.79 | 67 |

| Early hostile attributions* | −0.04 | 1.00 | 449 | 0.27 | 1.00 | 61 |

| Factors external to child | ||||||

| Early SES* | 40.60 | 13.70 | 504 | 31.50 | 13.90 | 66 |

| Adolescent SES* | 39.80 | 12.90 | 446 | 31.50 | 11.60 | 54 |

| Early stress* | 0.18 | 0.10 | 516 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 69 |

| Adolescent stress* | 0.15 | 0.10 | 446 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 54 |

| Neighborhood danger* | 1.93 | 0.81 | 415 | 2.43 | 0.90 | 50 |

| Proactive parenting | 3.32 | 0.65 | 500 | 3.18 | 0.74 | 66 |

| Adolescent harsh discipline* | 1.38 | 0.43 | 436 | 1.62 | 0.60 | 52 |

| Parental decision making | 2.66 | 0.35 | 437 | 2.58 | 0.34 | 52 |

| Monitoring* | 4.66 | 0.35 | 415 | 4.49 | 0.49 | 50 |

| Parental knowledge | 2.61 | 0.29 | 414 | 2.56 | 0.31 | 49 |

Note: Nonabused, n = 516; abused, n = 69.

Significant mean difference by t test, p < .05.

Table 2. Behavior problem sample statistics.

| Nonabused | Abused | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct and Grade | M | SD | n | M | SD | n |

| Externalizing behavior problems | ||||||

| K* | 5.17 | 8.08 | 509 | 10.25 | 11.53 | 65 |

| 1* | 6.22 | 9.36 | 481 | 9.98 | 11.48 | 56 |

| 2* | 6.21 | 9.56 | 458 | 13.34 | 14.14 | 59 |

| 3* | 5.89 | 9.29 | 443 | 12.53 | 13.84 | 55 |

| 4* | 5.70 | 9.20 | 416 | 13.67 | 13.59 | 52 |

| 5* | 6.58 | 9.63 | 406 | 13.29 | 12.56 | 42 |

| 6* | 6.43 | 9.86 | 396 | 12.73 | 14.11 | 48 |

| 7* | 6.13 | 9.46 | 379 | 11.09 | 11.45 | 47 |

| 8* | 7.02 | 11.00 | 356 | 13.66 | 14.22 | 47 |

| Internalizing behavior problems | ||||||

| K | 4.08 | 5.03 | 509 | 5.63 | 6.07 | 65 |

| 1* | 5.20 | 5.72 | 481 | 7.18 | 4.92 | 56 |

| 2* | 5.49 | 6.14 | 458 | 8.24 | 6.91 | 59 |

| 3* | 5.45 | 6.29 | 443 | 9.71 | 8.53 | 55 |

| 4 | 4.90 | 5.43 | 416 | 5.92 | 6.04 | 52 |

| 5 | 5.48 | 6.44 | 406 | 8.71 | 10.24 | 42 |

| 6* | 5.38 | 6.40 | 396 | 8.35 | 7.85 | 48 |

| 7* | 4.86 | 6.32 | 379 | 7.60 | 7.21 | 47 |

| 8* | 4.79 | 5.98 | 356 | 6.85 | 6.37 | 47 |

Note: Nonabused, n = 516; abused, n = 69.

Significant mean difference by t test, p < .05.

The tabled values are based on those respondents providing valid data for each variable, with no adjustments for attrition. In subsequent analyses, models were estimated using the missing data facility in Mplus v.2.02 (Muthen & Muthen, 2001); Mplus uses full information at maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) with missing data, which results in unbiased parameter estimates and appropriate standard errors when data are missing at random (MAR). FIML estimates are generally superior to those obtained with listwise deletion or other ad hoc methods, even when the MAR assumption is not fully met (Schafer & Graham, 2002).

Impact of predictors

The impact of the selected predictors on the trajectories of externalizing and internalizing behavior problems was examined in the non-abused sample to assess the normative effects.3 Ethnicity (African American vs. non African American) and gender were modeled as exogenous covariates, predicting the latent trajectory parameters. The models included intercept terms (set at kindergarten); slope terms (incremented by 0.5 each year; this term represents the instantaneous growth at the kindergarten wave); and acceleration, or quadratic, terms (the square of the slope term; this term represents the change in the rate of growth [slope] at each wave). Scaling factors for the latent slope and acceleration factors were based on a unit increment every 2 years. This was done for reasons of numerical precision; that is, by treating each year as 0.5 units of time, we avoided overly large path coefficients for the acceleration term (the coefficient for the effect of the acceleration factor on Grade 8 behavior is 42 = 16, rather than 82 = 64). This has no effect on the model properties, only on the scaling.

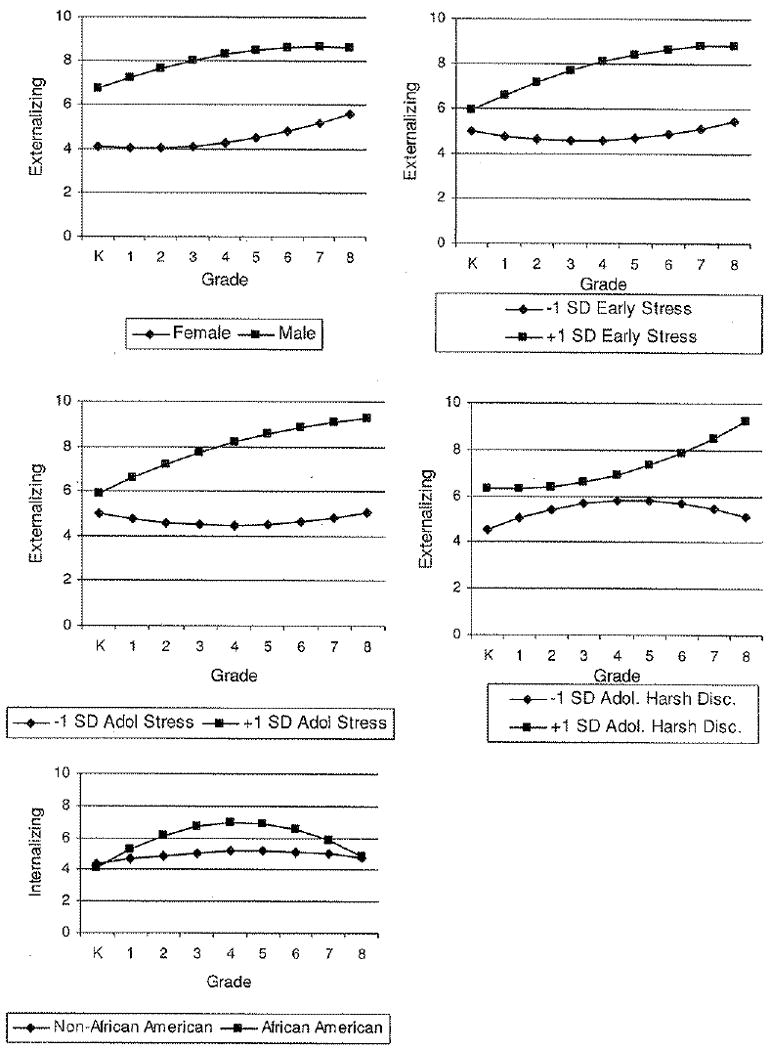

For each predictor, a model was estimated in which the predictor was related to the three trajectory components, covarying ethnicity and gender (the statistics reported for the effects' of each ethnicity and gender covaried the other, but no other predictors). Table 4 presents the test results: a 3 degree of freedom test of the overall impact, and, where that was statistically significant, estimates of the impact on each of the trajectory parameters (all continuous predictors were standardized in the sub-sample; thus, the estimates of effects are per standard deviation change in the predictor). In the absence of a significant effect on the acceleration component, the nature of the effect on the trajectory as a whole can generally be discerned from the effect estimates reported in Table 4. For those cases with significant effects on the acceleration term, Figure 1 depicts the model-implied trajectories at representative values of the predictors (i.e., the expected values at each grade, given the mean levels of the trajectory parameters and useful levels of the other predictors).

Table 4. Effects on trajectory parameters among nonabused children.

| Externalizing | Internalizing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | χ2 (3) | Intercept | Slope | Accel. | χ2 (3) | Intercept | Slope | Accel. |

| Child characteristics | ||||||||

| Ethnicity (African American) | 51.38*** | 1.85* (0.87) | 1.71* (0.74) | −0.06(0.19) | 13.64** | −0.21 (0.52) | 1.80** (0.57) | −0.43** (0.14) |

| Gender (male) | 33.36*** | 2.65*** (0.68) | 1.26* (0.58) | −0.29* (0.15) | 0.92 | — | — | — |

| Early social competence | 273.03*** | −4.73*** (0.29) | −0.10(0.30) | 0.13† (0.08) | 88.92*** | −1.02*** (0.20) | −0.32 (0.23) | 0.04 (0.06) |

| Early hostile attributions | 4.89 | — | — | — | 1.04 | — | — | — |

| Factors external to child | ||||||||

| Early SES | 44.28*** | −1.77*** (0.35) | 0.12(0.31) | −0.08 (0.08) | 33.33*** | −0.61*** (0.21) | 0.01 (0.24) | −0.06 (0.06) |

| Adolescent SES | 34.87*** | −1.20** (0.39) | −0.18(0.32) | −0.05 (0.08) | 40.56*** | −0.87*** (0.23) | 0.13 (0.25) | −0.08 (0.06) |

| Early stress | 13.94** | 0.48 (0.34) | 0.77* (0.32) | −0.17* (0.08) | 21.13*** | 0.02 (0.21) | 0.51* (0.24) | −0.07(0.06) |

| Adolescent stress | 36.52*** | 0.47 (0.38) | 0.99* (0.31) | −0.15† (0.08) | 33.73*** | 0.15 (0.21) | 0.40† (0.23) | −0.02 (0.06) |

| Neighborhood danger | 20.11*** | 0.51 (0.41) | 0.62† (0.34) | −0.05 (0.08) | 7.12† | — | — | — |

| Proactive parenting | 6.60† | — | — | — | 8.33* | −0.46* (0.20) | −0.02 (0.23) | 0.04 (0.06) |

| Adolescent harsh discipline | 20.47*** | 0.88* (0.38) | −0.62* (0.31) | 0.23** (0.08) | 5.03 | — | — | — |

| Parental decision making | 1.43 | — | — | — | 0.28 | — | — | — |

| Monitoring | 20.09*** | −0.96* (0.39) | 0.13(0.32) | −0.11 (0.08) | 12.14** | 0.18 (0.23) | −0.15(0.25) | −0.04 (0.06) |

| Parental knowledge | 22.11*** | −1.09** (0.37) | 0.02 (0.31) | −0.07(0.08) | 9.87* | −0.19(0.22) | 0.07 (0.24) | −0.06 (0.06) |

Note: Nonabused, n = 516. The values are the effects on the trajectory parameters and standard errors per standard deviation change (category change for demographics) in predictors after covarying ethnicity and gender.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

The trajectories of teacher-reported externalizing and internalizing behaviors with significant effects of gender, stress, adolescent harsh discipline, and ethnicity on the acceleration factor.

Most of the predictors had significant overall impacts on the trajectories of externalizing and/or internalizing behavior problems. The bulk of these effects were on the overall levels (intercepts) of behavior problem scores. Effect sizes can be estimated based on the estimated standard deviations of the trajectory intercepts. The intercept of the externalizing behavior trajectory had an estimated standard deviation of 6.20; by comparison, the effects of differences in social competence were especially large (4.73), exceeding half of the intercept standard deviation per unit (standard deviation) change in the predictor. Similarly, effects on the intercept of internalizing behavior can be compared to the estimated standard deviation of 2.60.

Resilience effects

To identify resilience effects, the impact of each predictor on the latent trajectory parameters was modeled separately in the abused and nonabused groups.4 Resilience, as a form of interaction between abuse and the predictor, would be evident where abuse had less impact at certain values of the predictor variable, or, conversely, that the predictor's impact was greater in the abused group. This interaction was tested for each predictor by applying the constraint that the effect of the predictor on the trajectory was equal between groups, controlling for ethnicity and gender.

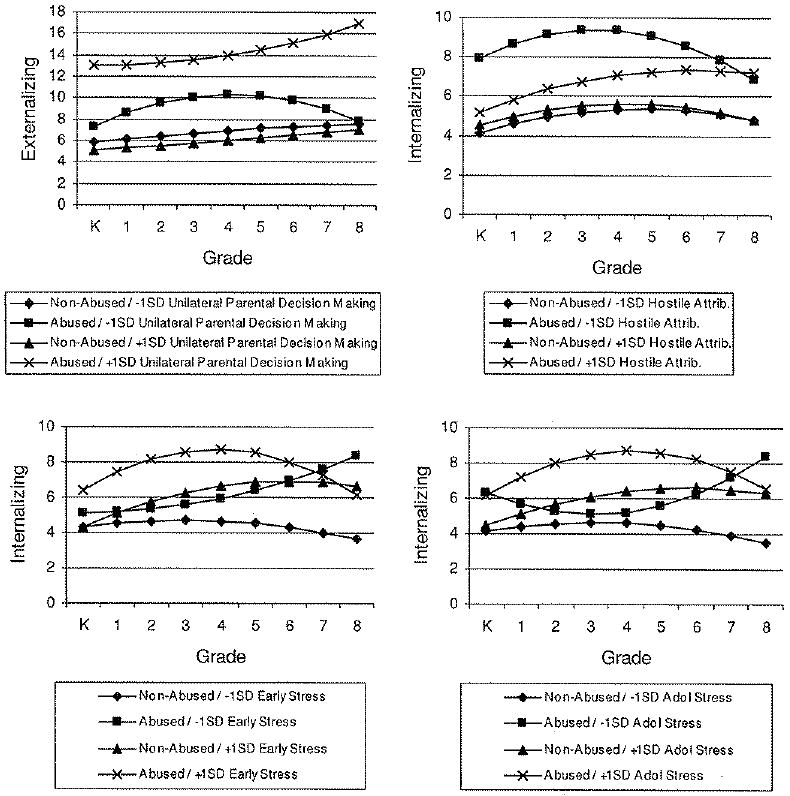

For externalizing behavior, a significant interaction with abuse was found for one factor external to the child, unilateral parental decision making, full model χ2 (114) = 163.55, p < .001, comparative fix index (CFI) = .976, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = .973, root mean square error analysis (RMSEA) = .039 (90% confidence interval [CI] = .024 and .051), restricted model χ2 (117) = 173.04, p < .001, CFI = .972, TLI = .970, RMSEA = .040 (90% CI = .027 and .053), likelihood ratio [LR] χ2 (3) = 9.49, p < .03.5 The parameter estimates are summarized in Table 5, including tests of the overall impact of the predictor in each group; Figure 2 shows the model-implied trajectories in each group at representative levels of the predictors. As Figure 2 shows, by Grade 8, abused children with parents low on unilateral decision making showed levels of externalizing behavior problems similar to those of nonabused children (regardless of levels of unilateral parental decision making).

Table 5. Effects of predictors by abuse.

| Nonabused | Abused | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome and Predictor | χ2(3) | Intercept | Slope | Accel. | χ2(3) | Intercept | Slope | Accel. |

| Externalizing behavior | ||||||||

| Parental decision making | 1.42 | −0.37 (0.38) | −0.12(0.31) | 0.04 (0.08) | 8.80* | 2.86†(1.50) | −1.44(1.38) | 0.47 (0.34) |

| Internalizing behavior | ||||||||

| Early stress | 21.10*** | 0.02 (0.21) | 0.54* (0.25) | −0.07 (0.06) | 9.70* | 0.90 (0.58) | 0.54 (0.90) | −0.23(0.21) |

| Adolescent stress | 33.65*** | 0.15 (0.22) | 0.42† (0.24) | −0.03 (0.06) | 13.12** | −0.10 (0.63) | 2.04* (0.87) | −0.56** (0.20) |

| Early hostile attributions | 1.19 | 0.20 (0.22) | −0.01 (0.24) | −0.01 (0.06) | 7.68† | −1.37* (0.65) | −0.16(0.97) | 0.14 (0.22) |

Note: Nonabused, n = 516; abused, n = 69. The values are the effects on the trajectory parameters and standard errors per standard deviation change in predictors after covarying ethnicity and gender. The χ2 values are for the overall effect of the predictor on the trajectory parameters within the respective abuse-status group.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 2.

The trajectories of teacher-reported externalizing and internalizing behavior with resilience effects of stress, unilateral parental decision making, and hostile attributions.

For internalizing behavior, a significant interaction was found for one child characteristic, early hostile attributions, full model χ2 (114) = 131.95, p > .10, CFI = .960, TLI = .956, RMSEA = .023 (90% CI = .000 and .039), restricted model χ2 (117) = 140.91, p < .07, CFI = .946, TLI = .942, RMSEA = .026 (90% CI = .000 and .041), LR χ2 (3) = 8.96, p < .03. Early tendencies to make hostile attributions had an apparently beneficial effect on early internalizing behavior problems among abused children, but no effect among nonabused children; the former effect was not apparent by the end of the time frame.

For internalizing behavior, a significant interaction also was found for early stress, full model χ2 (114) = 136.87, p < .08, CFI = .952, TLI = .946, RMSEA = .026 (90% CI = .000 and .041), restricted model χ2 (117) = 146.26, p < .04, CFI = .938, TLI = .933, RMSEA = .029 (90% CI = .008 and .043), LR χ2 (3) = 9.39, p < .03. Early internalizing problems were highest among abused respondents with elevated early family stress, suggesting a vulnerability process. By Grade 8, the predicted values were less distinct, and highest for abused respondents with lower early family stress.

Finally, for internalizing behavior, a significant interaction was found for adolescent stress, χ2 (114) = 147.28, p < .02, CFI = .933, TLI = .926, RMSEA = .032 (90% CI = .013 and .045), restricted model χ2 (117) = 161.547, p < .01, CFI = .911, TLI = .904, RMSEA = .036 (90% CI = .021 and .049), LR χ2 (3) = 14.27, p < .01. As would be expected, adolescent stress did not predict internalizing problems at kindergarten. Among abused respondents, those with higher levels of family stress in adolescence showed more internalizing problems until Grade 7, when the trajectories crossed. Among nonabused respondents, stress led to a divergence in the trajectories that increased with time.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to advance understanding of the role that vulnerability and protective factors have in shaping trajectories of externalizing and internalizing behaviors as well as how these vulnerability and protective factors moderate associations between early experiences of physical abuse and later trajectories of externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Our hypothesis that protective factors would be related to dampened trajectories of externalizing and internalizing problems, whereas vulnerability factors would be related to higher levels of externalizing and internalizing problems over time was generally supported by the findings.

We found limited support for our hypothesis regarding the differential harm or benefit conferred by additional vulnerability factors or protective factors, respectively, for children who experienced abuse versus those who did not. Four of the vulnerability and protective factors we examined moderated the association between physical abuse and internalizing and externalizing behavior trajectories.

For externalizing behavior, a significant interaction with abuse was found for unilateral parental decision making. Trajectories of externalizing behavior for abused children experiencing low levels of unilateral parental decision making were only somewhat elevated compared to nonabused children who had low levels of unilateral parental decision making (a protective–stabilizing effect; Luthar et al., 2000). Both abused and nonabused children who were high in unilateral parental decision making had elevated externalizing behavior trajectories, but this was especially the case for the abused children.

For internalizing behavior, significant interactions were found for early stress, adolescent stress, and hostile attributions. A vulnerability process was suggested in relation to early stress; early internalizing problems were highest for abused respondents with elevated early family stress. Adolescent stress was not related to internalizing in kindergarten (as would be expected), but among abused respondents, those with higher levels of family stress in adolescence showed more internalizing problems until Grade 7; however starting in Grade 5 abused respondents who experienced higher levels of stress during adolescence showed a downward curve in their trajectory of internalizing problems. This finding suggests that there is a counterintuitive inverse relation between stress and internalizing problems during adolescence for adolescents who were abused as children, even though they continue to show higher levels of internalizing problems than do other adolescents. One possibility is that experiencing family stress gives these vulnerable adolescents a problem around which to rally with their families, which may have the unexpected effect of decreasing their internalizing problems. Future research will be necessary to investigate whether the finding replicates and, if so, why.

The pattern of findings was especially interesting, and surprising, for hostile attributions. For the nonabused children, hostile attributions had no apparent effects on internalizing behavior trajectories. For the abused children, however, those high in early hostile attributions showed fewer internalizing problems than those low in hostile attributions. It appears that, for abused children, making hostile attributions may be an adaptive strategy in buffering them from internalizing problems, although not from externalizing problems. Perhaps attributing hostile intent in a truly hostile environment helps abused children to avoid internalizing problems that may result from self blame in their circumstances (Lynch & Cicchetti, 1998). This finding may be analogous to findings termed pathologic adaptation to violence, which show that some youth experience emotional numbing in response to witnessing frequent violence in the community; the emotional numbing reduces internalizing problems but may also increase violent behavior (Garbarino, 1995; Ng-Mak, Salzinger, Feldman, & Stueve, 2004; Schwab-Stone et al., 1995).

Thus, our findings provide a great deal of support for an additive or main effect perspective on vulnerability and protective factors and some support for an interactive perspective, both for child characteristics and for factors external to the child. It appears that some protective and vulnerability factors do not have stronger effects for physically abused children but instead are equally beneficial or harmful (within the power of our study to detect differences) to children regardless of their abuse status. Examining effects of vulnerability and protective factors on trajectories of internalizing and externalizing behaviors rather than developmental outcomes at a single point in time is not yet common in the resilience literature, and therefore this study represents an important direction for the resilience area.

Limitations, Future Directions, and Conclusions

Because the present study used a community rather than clinical sample, the experience of physical abuse is not confounded with the substantiation and treatment of abuse, which may exacerbate effects of the original abuse (Barnett, Manley, & Cicchetti, 1993). Because most cases of child abuse go unreported (National Research Council, 1993), studies drawing from clinical samples are likely to be biased by including only those cases of abuse that have attracted the attention of Child Protective Services, which limits the generalizability of findings. The present study's inclusion of children who have been physically harmed in early life but who have not necessarily been identified by public agencies does not confound the experience of physical abuse with experiences that follow its public substantiation. Along with these advantages, however, is the disadvantage that the abused children in our sample likely experienced different levels of risk. The consequences of child abuse may vary by the severity and chronicity of the abuse (Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001), the child's interpretation of the incident (Shields, Ryan, & Cicchetti, 2001), and the family and community response to the abuse (Molnar, Buka, Brennan, Holton, & Earls, 2003); our abused sample is likely diverse in these respects. Furthermore, retrospective reports of abuse are subject to biases in recall and reporting. Because parents were made aware of the obligation to report suspected cases of child abuse to child protective service agencies, they probably underreported abusive incidents. Future research will benefit from examining developmental trajectories of internalizing and externalizing behaviors in relation to vulnerability and protective factors that include more detailed information about the circumstances of abuse and a variety of methods to assess whether abuse occurred.

The present study focused on children's experience of physical abuse; results should not be generalized to sexual abuse, emotional abuse, or neglect. Of the approximately 3 million children who are referred annually to local child protective service agencies as possible victims of maltreatment, approximately 25% are suspected of having been physically abused (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Clearly, documenting trajectories of externalizing and internalizing behaviors associated with sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect as well as examining protective and vulnerability factors that may moderate these trajectories remain important issues to be addressed in future research.

Future research also will benefit from including a broader range of vulnerability and protective factors than those included in this study and from adopting a mediation approach to examine mechanisms through which vulnerability and protective factors exert their influence in increasing or decreasing risk for poor outcomes among abused children. For example, other child characteristics such as the child's intelligence as well as other factors external to the child such as community violence, the quality of the child's relationship with the nonabusing parent, and support from adults outside the family have been included in previous studies of resilience (see Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000). These and other vulnerability and protective factors would be candidates for inclusion in future studies that examine developmental trajectories of adjustment in the face of physical abuse. Yet another direction for future research will be to examine effects of multiple vulnerability and protective factors simultaneously rather than one at a time (see Pettit, 2000).

In a related point, our analysis was limited by the pattern of data collection of possible moderators. Some variables (e.g., stress) were measured on each occasion; others, including parental decision making, only once. Our analysis approach did not reflect the timing of measurement, even of those variables measured only once. Rather, each variable was construed as a time-invariant characteristic of the child or the child's environment. This may have resulted in some variables tending to show their greatest impact near the time of measurement. Future work could incorporate timing of measurement in a more sophisticated fashion. Another point regarding the selected potential moderators is that our analysis did not accommodate the intercorrelations among the predictors. Each predictor was modeled separately, This resulted in clear statements about each variable's effects, but did not model the covariances.

Another measurement limitation is the age of the sample at study entry. Our measurement of abuse is based on events in the first 5 years of the child's life; however, our measurement did not begin until after that point. Thus, we do not have data that precede the abuse. This complicates interpretation of our models: if we had had preabuse data, we could have more clearly segregated the portions of the trajectories that are affected by the abuse from those that might have differed beforehand. As it stands, some of the differences captured by our tests may reflect differences due to the child's background in early life. However, focusing only on differences in trajectories after age 5 could fail to detect important effects of maltreatment. Intercept differences (which result from processes, including abuse, that occurred prior to the start of the study) and differences in trajectories from that starting point are both of interest in the present investigation. It is possible that our study underestimated differences in trajectories between the abused and nonabused groups because we were not able to capture differences in trajectories prior to age 5.

Another possible limitation, more technical, is the large number of comparisons in the analysis strategy. Four of the tests of interactions were significant; this is probably more than would be expected by chance, but not an overwhelmingly robust pattern. Our approach was to be broadly systematic in searching for moderator effects, within the theoretical framework of the major developmental tasks that face children who have been physically abused. For statistical reasons (McClelland & Judd, 1993), it is challenging to detect moderator effects. More conclusive research would be facilitated by a larger sample of abused children, enhancing power to detect interactions.

Competent functioning has been defined differently throughout the abuse literature. Commonly used indicators of competence have included self-esteem (Lynch & Cicchetti, 1998), social skills (Trickett, 1997), cognitive ability (Rogosch, Cicchetti, & Aber, 1995), and a lack of depressive symptoms (Johnson et al., 2002). In the present study, we chose to look at low levels of children's externalizing and internalizing behaviors as indicators of children's competent functioning. Future research should explore developmental trajectories of other areas of competence, as well as externalizing and internalizing behaviors reported by respondents other than children's teachers (as was done in the present study) and observed directly by researchers. An additional direction for future research will be to elucidate how developmental trajectories of diverse indicators of competence may be affected differently by protective and vulnerability factors. Using multiple informants and observational data will contribute to minimizing method variance.

In addition to examining other measures of competent functioning, it will be important for future research to consider simultaneously children's resilience across a number of domains; that type of approach would raise the question of how to define resilience. For example, if a child shows no problems in one domain but has problems in other, would that child be considered resilient? In our own study, although adolescents who had been abused and who also had high levels of hostile attributions had fewer internalizing behavior problems than those who had lower levels of hostile attributions, this finding does not take into account whether these adolescents' problems were manifested through externalizing behaviors instead. For the clearest understanding of resilience, it will be necessary to examine children's profile of competence across several domains.

In summary, our results suggest two main findings. First, regardless of whether the child was abused, being African American, being male, having low early social competence, low early SES, low adolescent SES, and experiencing adolescent harsh discipline, low monitoring, and low parental knowledge elevated trajectories of externalizing problems; having low early social competence, low early SES, low adolescent SES, and low proactive parenting elevated trajectories of internalizing problems. Second, unilateral parental decision making, early stress, adolescent stress, and hostile attributions moderated the link between early physical abuse and trajectories of externalizing and internalizing behaviors, suggesting resilience effects.

A message for clinicians and others who work with abused children in applied settings is that attention should be paid to vulnerability and protective factors in addition to focusing on the abuse itself. For example, perhaps social skills interventions designed to boost social competence could powerfully modify trajectories of externalizing and internalizing problems of physically abused children.

Acknowledgments

The Child Development Project was funded by Grants MH42498, MH56961, MH57024, and MH57095 from the National Institute of Mental Health and HD30572 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. We are grateful for the ongoing dedication of the Child Development Project participants and research staff. Portions of these results were presented at the 2002 American Psychological Society convention in New Orleans, LA.

Footnotes

The finding that physical abuse is related to more behavior problems for African American than European American children in this sample is different from the finding in the same sample that parents' use of nonabusive physical discipline is related to problem behaviors for European American children but not for African American children (Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1996; Lansford, Deater-Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 2004). This suggests that physical discipline and physical abuse are qualitatively different experiences, and findings about ethnic differences in one should not be generalized to ethnic differences in the other.

We focused on hostile attributions rather than including all of the measures of social information processing assessed by Dodge et al. (1995) because making attributions might be an especially important process for abused children trying to make sense of why the abuse occurred.

We restricted this analysis to the nonabused sample to provide a context for interpretation of the moderating effects of abuse; of course, a general survey of the effects of these variables would require use of the full sample.

When adolescents were in Grade 8, parents were asked a question about whether anyone had ever expressed concerns or accusations about the child being physically abused since the child started kindergarten. Of the 69 children in the group designated as being abused prior to kindergarten, 15 children's parents said there had been concerns about abuse since that time; of the children who were not in the abused group prior to kindergarten, 58 children's parents said there had been concerns about abuse since that time. We reran all of the moderation analyses excluding the 58 children in this later abuse group. The substantive findings remained unchanged; the same moderators were and were not significant.

A nonsignificant chi square indicates that the model-implied covariances do not differ significantly from the sample data. However, large sample sizes, deviations from normality, and other factors can result in significant chi square statistics even when the difference from the sample data is small. Conventionally, CFI and TLI values over .95 are taken to indicate good approximate fit, and RMSEA values below .08 are acceptable (values below .05 are preferable). Comparisons between nested models (i.e., where the parameters estimated in one model are a subset of the parameters estimated in the other) are typically tested by the LR test, in which the difference in the chi square statistics of the two models is distributed as a chi square, with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in the number of parameters.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for Teacher's Report Form and J991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Teacher's Report Form and teacher version of the Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony EJ. Introduction: The syndrome of the psychologically vulnerable child. In: Anthony EJ, Koupernik C, editors. The child in his family: Children at psychiatric risk. New York: Wiley; 1974. pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Atter B, Guerra N, Tolan P. Neighborhood disadvantage, stressful life events, and adjustment in urban elementary-school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994;23:391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manley JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Ciccheitti D, Toth SL, editors. Advances in applied developmental psychology: Vol 8. Child abuse, child development and social policy. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1993. pp. 7–73. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Mounts N, Lamborn SD, Steinberg L. Parenting practices and peer group affiliation in adolescence. Child Development. 1993;64:467–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Patterson GR. Psychometric properties of fourteen latent constructs from the Oregon Youth Study. New York: Springer–Verlag; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, Mill J, Martin J, Craig IW, et al. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science. 2002;297:851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1072290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Li D, Li Z, Li B, Liu M. Sociable and prosocial dimensions of social competence in Chinese children: Common and unique contributions to social, academic, and psychological adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:302–314. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Garmezy N, editors. Development and Psychopathology. Vol. 5. 1993. Milestones in the development of resilience; pp. 497–774. Special Issue. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Lynch M. Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: Consequences for children's development. Psychiatry. 1993;56:96–118. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. The role of self-organization in the promotion of resilience in maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:797–815. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Lynch M, Holt KD. Resilience in maltreated children: Processes leading to adaptive outcome. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:629–647. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65:541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen EL, Wyman PA, Work WC, Kim JY, Fagen DB, Magnus KB. Follow-up of young stress-affected and stress-resilient urban children. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:565–577. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Physical discipline among African American and European American mothers: Links to children's externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, Skinner ML. Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Socialization mediators of the relation between socioeconomic status and child conduct problems. Child Development. 1994;65:649–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. How the experience of early physical abuse leads children to become chronically aggressive. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology: Vol 8. Developmental perspectives on trauma. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1997. pp. 263–288. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Valente E. Social information-processing patterns partially mediate the effect of early physical abuse on later conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:632–643. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, McClaskey CL, Brown M. Social competence in children. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1986;51(2 Serial No 213) [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Price JM, Bachorowski J, Newman JP. Hostile attributional biases in severely aggressive adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:385–392. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Farber E. Invulnerability among abused and neglected children. In: Anthony EJ, Cohler B, editors. The invulnerable child. New York: Guilford Press; 1987. pp. 253–288. [Google Scholar]

- Foley DL, Eaves LJ, Wormley B, Silberg JL, Maes HH, Kuhn J, et al. Childhood adversity, monoamine oxidase A genotype, and risk for conduct disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:738–744. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J. Raising children in a socially toxic environment. San Francisco, CA: Jossey–Bass; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:539–579. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four-Factor Index of Social Status. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1979. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RM, Kotch JB, Catellier DJ, Winsor JR, Dufort V, Hunter W, et al. Adverse behavioral and emotional outcomes from child abuse and witnessed violence. Child Maltreatment. 2002;7:179–186. doi: 10.1177/1077559502007003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan HB. Toward an understanding of resilience: A critical review of definitions and models. In: Glantz MD, Johnson JL, editors. Resilience and development: Positive life adaptations Longitudinal research in the social and behavioral sciences. New York: Kluwer; 1999. pp. 17–83. [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS. A cross-domain growth analysis: Externalizing and internalizing behaviors during 8 years of childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:161–179. doi: 10.1023/a:1005122814723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiley MK, Howe TR, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. The timing of child physical maltreatment: A cross-domain growth analysis of impact on adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:891–912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer BJ, Coleman CC. Classroom peer acceptance, friendship, and victimization: Distinct relational systems that contribute uniquely to children's school adjustment? Child Development. 1997;68:1181–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Criss MM, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Bates JE. Friendship quality, peer group affiliation, and peer antisocial behavior as moderators of the link between negative parenting and adolescent externalizing behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:161–184. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.1302002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Ethnic differences in the link between physical discipline and later adolescent externalizing behaviors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:801–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Crozier J, Kaplow J. A 12-year prospective study of the long-term effects of early child physical maltreatment on psychological, behavioral, and academic problems in adolescence. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:824–830. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Wells KC. Contextual social–cognitive mediators and child outcome: A test of the theoretical model in the coping power program. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:945–967. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS. Vulnerability and resilience. A study of high-risk adolescents. Child Development. 1991;62:600–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D. The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:857–885. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Cicchetti D. An ecological–transactional analysis of children and contexts: The longitudinal interplay among child maltreatment, community violence, and children's symptomatology. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:235–257. doi: 10.1017/s095457949800159x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist. 1990;45:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children's adjustment: Contributions of developmental liming and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GH, Judd CM. Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:376–390. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGloin JM, Widom CS. Resilience among abused and neglected children grown up. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:1021–1038. doi: 10.1017/s095457940100414x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Buka SL, Brennan RT, Holton JK, Earls F. A multilevel study of neighborhoods and parent-to-child physical aggression: Results from the Project on Human Development in Chicago neighborhoods. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:84–97. doi: 10.1177/1077559502250822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran PB, Eckenrode J. Protective personality characteristics among adolescent victims of maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1992;16:743–754. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user's guide. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Understanding child abuse and neglect. Washington, DC: Author; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ng-Mak DS, Salzinger S, Feldman RS, Stueve CA. Pathologic adaptation to community violence among inner-city youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004;74:196–208. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU. A cultural ecology of competence among inner-city Blacks. In: Spencer MB, Brookins GK, Allen WR, editors. Beginnings: The social and affective development of Black children. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1985. pp. 44–66. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid J, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castilia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit G. Mechanisms in the cycle of maladaptation: The life-course perspective. Prevention and Treatment. 2000;3 Article 35. Retrieved from http://journals.apa.org/prevention/volume3/pre0030035c.html.

- Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Supportive parenting, ecological context, and children's adjustment: A seven-year longitudinal study. Child Development. 1997;68:908–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]