Abstract

Selective ligands to the Peripheral Benzodiazepine Receptor (PBR) may induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. An over-expression of PBR in certain cancers allowed us to consider the use of highly selective ligands to PBR for receptor-mediated drug targeting to tumors. With this in mind, we prepared PBR-targeted nanoparticulate drug delivery systems (PEG-PE micelles) loaded with the anticancer drug paclitaxel (PCL) to test possible synergistic anticancer effects. PEG2k-PE-based polymeric micelles with and without PCL were prepared in HBS, pH 7.5, and conjugated with a PBR-ligand (CB86) in 0.45% of DMSO. The cytotoxic effect of such micelles against the LN 18 human glioblastoma cell line was studied in cell culture. The micelles maintained their size and size distribution and remained intact without drug release after the PBR-ligand conjugation. The PCL-loaded PBR-targeted micelles showed a significantly enhanced toxicity against human glioblastoma LN 18 cancer cells in vitro. Thus, PBR-targeted nanopreparations may potentially serve as a new nanomedicine for targeted cancer therapy.

Keywords: PEG-PE micelles, PBR receptor, drug delivery, paclitaxel, cytotoxicity

INTRODUCTION

Poor water solubility is a property of many drugs including powerful anticancer ones. Paclitaxel (PCL), a diterpenoid extracted from Taxus brevifolia, is a strong mitotic inhibitor of cell replication used in various cancer treatments including breast, ovarian, liver, head and neck cancers 1. It has a water solubility of less than 1 μg/mL 2. Because of this, it is currently used in a formulation made with Cremophor EL and ethanol 1:1 (v/v) and subsequently diluted in saline solutions prior to intravenous administration. However, this Cremophor EL/ethanol mixture provokes serious undesirable side effects, such as hypersensitivity, nephrotoxicity, and neurotoxicity 3–5. In attempts to minimize these problems, a variety of PCL drug delivery systems have been investigated 6.

Our study focused on micelles, spherical colloidal nanoparticles formed by self-assembly of amphiphilic polymeric molecules. In water, the hydrophobic fragments of these molecules form the core of a micelle, the compartment into which the poorly water soluble drug is entrapped 7. In this way, its water solubility and bioavailability are increased. In addition, due to their small size (5–100 nm), micelles spontaneously accumulate in pathological areas with leaky blood capillaries (such as in infarcted or tumorous areas). This phenomenon is known as the EPR (enhanced permeability and retention) effect 6, 8, 9. Here, we have used micelles made of the polyethylene glycol-phosphatidylethanolamine (PEG-PE) conjugate, since they are stable, long-circulating and have been successfully used to entrap and deliver various poorly water soluble drugs, including anticancer drugs 6. Furthermore, they have been shown to increase the pharmacological effect of the entrapped drug when conjugating specific targeting molecules, such as monoclonal antibodies and certain other ligands, with drug-loaded micelles, to selectively enhance micelle uptake (both cellular and sub-cellular) at specific disease sites 10, 11.

In this study, we specifically investigated the conjugation of a hydrophobic compound, the PBR-ligand (Peripheral Benzodiazepine Receptor ligand), with pre-formed PCL-loaded PEG-PE micelles, and the possible synergistic effect of the PBR-ligand attachment on the anticancer activity of the micellar drug. PBRs are located on the outer membrane of mitochondria, and expressed either in the central nervous system (mostly in glial cells) or in the peripheral organs involved in steroidogenesis 12, 13. The PBR potentially mediates antitumor effects since it belongs to a multiproteic complex known as the “Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore” (MPTP) 14, which plays a key role in control of the apoptotic process. It is involved in numerous physiological functions and pathological effects 15, and its ligands have been shown to modulate the MPTP pores and subsequent apoptotic events. Agonists for PBR may stimulate the opening of these pores, and trigger the cascade of apoptosis 16. In some neuropathologies, brain cancers and traumatic and toxic brain injuries that the PBR density is altered17 and results in a “receptorial overexpression” compared to healthy tissue. Additionally, in some pathologies, a significant correlation has been noted between the PBR overexpression and poor prognosis or metastatic development 18.

With this in mind, we designed a preparation of PEG-PE micelles loaded with PCL and surface-modified with a PBR-ligand (imidazopyridine derivative) and assayed for the in vitro synergism between PCL and PBR-ligand on human glioblastoma LN 18 cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy (polyethylene glycol)-2000] (PEG2k–PE) and phosphatidylethanolamine lissamine rhodamine B (Rh-PE, Mw 1233 Da) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA) and used without further purification. p-nitrophenyloxycarbonyl p-NP-PEG2k–PE was synthesized in our laboratory according to an established procedure 19. Paclitaxel (PCL), and triethylamine (TEA) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). The PBR-ligand, N,N-Di-n-propyl-[2-(4-chlorophenyl)-8-aminoimidazo-[1,2-a]pyridin-3-yl]acetamide (known as CB86), was synthesized according to a published procedure 20–22. Methanol (CH3OH), acetonitrile, chloroform (CHCl3) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased as analytical grade preparations from Fisher Scientific and used without further purification.

Cell culture

Human glioblastoma LN18 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), at 37 °C and 5% CO2. DMEM and supplements (fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin and amphotericin B) were from CellGro (Kansas City, MO, USA). The Hoechst 33342 (a nucleic acid stain) was purchased from Molecular Probes Inc. (Eugene, OR, USA) and Cell Titer 96® Aqueos One Solution (for cytotoxicity assay) from Promega (Medison, WI).

Preparation of CB86-conjugated and PCL-loaded micelles (targeted micelles)

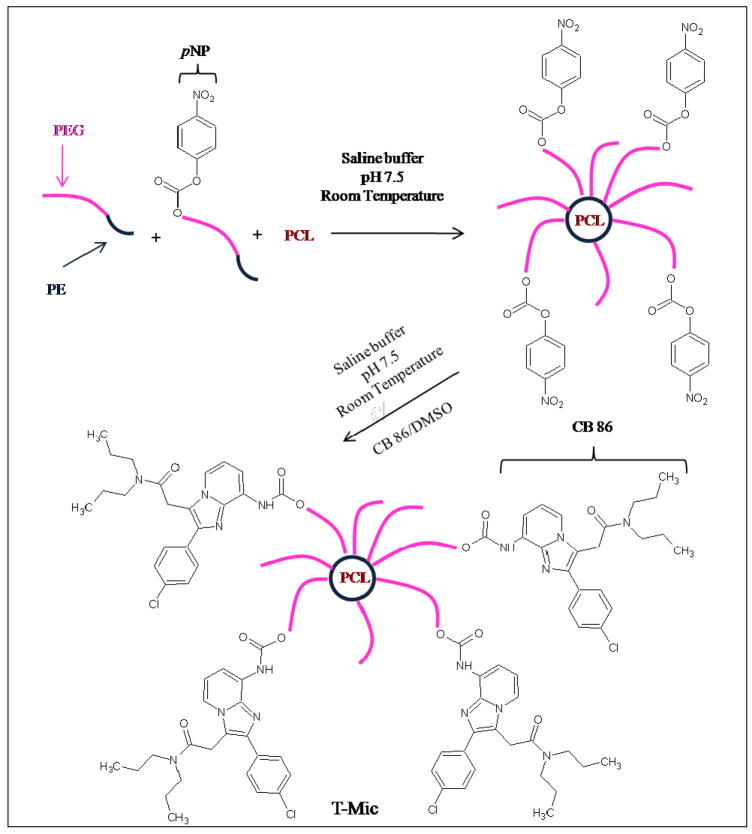

The CB86-conjugated and PCL-loaded micelles (surface-modified targeted micelles, T-Mic) were prepared as follows. A thin polymeric film 23, 24 was formed in a round-bottom flask by removing the organic solvents from the mixed solution of PEG2k-PE and p-NP- PEG2k-PE (10% w/w of PEG2k-PE) in chloroform and PCL in methanol (0.75 mg of paclitaxel per 16.5 mg of polymers) by rotary evaporation with the temperature of the warming bath below 40 °C. Whenever required, 0.5% wt of Rh-PE (% wRh-PE/wpolymer) was added to the polymeric mixture for fluorescent labeling. The film was further dried under vacuum for 4 hours (LABCONCO, Freeze Dry System, Freezone ®) at −48 °C to remove traces of solvents. To generate spontaneous self-assembly of micelles, the dry polymeric film was hydrated at room temperature with HBS, pH 7.5, at a PEG2k-PE concentration of 3.6 mM (10 mg of micelle-forming material per 1 mL buffer). The hydrated mixture was vigorously vortexed for 5 min and sonicated for 7 more min. The non-incorporated PCL was removed by filtration of the micelle suspension through a 0.2 μm nylon membrane (Millipore Co., Bedford, MA). For the conjugation of the PBR-ligand (CB86) with micelles via the interaction of PBR-ligand amino-groups with p-nitrophenyloxycarbonyl-activated termini of some PEG chains (Figure 1) 10, 25, the suspension of micelles was incubated at room temperature, in darkness, without oxygen, for 4 h with a solution of CB86 in DMSO (0.45% of DMSO of the total buffer volume) at a 10-fold molar excess of CB86 (2.06 mg or 5.36×10−6 moles of CB86 per 1.5 mg or 5.36×10−7 moles of activated polymer). After the CB86 solution was added to the micelles, the mixture was sonicated for a few seconds for better dispersion of the compound in the reaction system.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the CB86 conjugation at the micelle surface. T-Mic micelles loaded with PCL were synthesized by incubating pNP- activated micelles in HBS buffer (pH 7.5), at room temperature, for 4 hours with CB86 in DMSO (0.45% on the total volume of the micelle suspension). The same procedure was followed to make empty T-Mic micelles. During their preparation, a certain amount of CB86 could also become loosely associated with micelles via non-covalent binding (not shown in this scheme).

The unbound PBR-ligand (CB86), DMSO, and liberated p-nitrophenol were removed by dialyzing 1.65 ml of a micelle sample for 24 h against 250 mL of HBS (pH 7.4) using a regenerated cellulose membrane (RC) dialysis bag (SpectraPor®) with the cut-off size of 1000 Da at 4 °C with several buffer changes. The micelles were additionally filtered through a 0.2 μm nylon membrane.

The same procedure was followed for preparing plain micelles (micelles with no conjugated CB86 on their surface, and made of 100% wt PEG-PE, P-Mic) with or without PCL.

Micelles size and zeta potential (ζ)

The micelle size and size distribution were measured by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) using a Zeta Plus instrument (Brookhaven Instrument Corporation, Holtsville, NY). The micelle suspension was analyzed after the appropriate dilution required for DLS. For each sample, micelle size distribution measurement was done for six cycles per run.

The Zeta-potential of micelle formulations was measured by a Zeta Phase Analysis Light scattering (PALS) with an ultra sensitive Zeta Potential Analyzer instrument (Brookhaven Instruments, Holtsville, NY). The micelle suspensions were diluted with deionized water 1:30/micelles:water. All zeta-potential measurements were performed in triplicate.

Critical micelle concentration (CMC)

The CMC for both preparations (empty T-Mic and P-Mic) was determined by the pyrene method 26, 27. In glass test tubes, a solution of pyrene (1 mg) in chloroform was added for each tube. The solvent was removed under high vacuum overnight at room temperature and in darkness. Each tube containing 1 mg of pyrene crystals was incubated and shaken in darkness at room temperature for 24 h with known dilutions of the micelle suspensions that ranged between 7.2×10−7 M and 3.6×10−4 M. The unincorporated pyrene in the micelles was filtered through 0.2 μm nylon filters. Each dilution was analyzed by fluorescence spectroscopy to evaluate the amount of pyrene retained in micelles and to directly correlate to the concentration of the micelles themselves. The fluorescence was recorded at the excitation wavelength of 339 nm and emission of 390 nm by an F-2000 fluorescence spectrometer (Hitachi, Japan). The CMC value corresponds to the concentration of the polymer at which the sharp increase in solution fluorescence is observed because of partial pyrene solubilization by the appearing micelles.

1H NMR and GPC analysis

The 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 500 MHz spectrometer in deuterated chloroform (CDCl3), and the spectra of empty CB86-conjugated T-Mic and pNP-activated micelles precursor were compared for a full characterization of all the micelle components.

The GPC analysis was performed using a Hitachi D-7000 HPLC system equipped with a diode array assay, a Shodex KW 804 column, at a flow rate of 1 mL/min with phosphate buffer (100 mM phosphate and 150 mM Na2SO4), pH 7.0, as a mobile phase. The empty and loaded T-Mic were detected at λ 254 nm (the absorbance wavelength of the PBR-ligand).

PCL loading and the CB86 amount

The content of the solubilized PCL in P-Mic and T-Mic and the amount of the PBR-ligand CB86 were measured by the reversed phase HPLC (D-7000 HPLC system, Hitachi, Japan) using a XBridge column (4.6mm×250mm, Waters, Milliford, USA). A known amount of micelles was solubilized with acetonitrile (to release free PCL) (1:20 = micelle suspension:acetonitrile, v/v) and then analyzed with acetonitrile:water (52:48 % v/v) as the mobile phase, at a 1.0 mL/min flow rate and with the detection at 227 nm (the absorbance wavelength of paclitaxel). Each run was done in triplicate. The PCL loading was determined using a calibration curve obtained in the same conditions using standard concentrations of PCL in acetonitrile (ranging between 0.189 and 30.25 μg/mL), the correlation factor r2 was 0.999.

To evaluate the amount of the CB86, a known volume of T-Mic (empty and/or loaded) was diluted in methanol (1:20 = micelle suspension:methanol, v/v) and then analyzed with methanol:water (80:20 % v/v) as a mobile phase, at 1.0 mL/min and detected at 254 nm. Each run was done in triplicate. To determine the concentration of the CB86, a calibration curve of standard concentrations of the ligand in methanol (ranging between 0.192 and 30.75 μg/mL) was used. Its correlation coefficient r2 was 0.998.

Kinetics of drug release and carbamate group hydrolysis

The release of the anticancer drug from PCL-loaded P-Mic and T-Mic, and the stability of the bond between PBR-ligand and the micelle surface were monitored in sink conditions for 48 h at 37 °C, with continuous shaking at 100 rpm (Environ Shaker, Lab Line) using micelle samples placed in a regenerated cellulose dialysis bag (cut-off size of 1000 Da, SpectraPor®). 1 mL of PCL-loaded micelles was dialyzed against 25 mL of 1 M sodium salicylate (known to increase the PCL solubility28). Similarly, the same volume of CB86-conjugated micelles was dialyzed against HBS, pH 7.4. At determined time-points, 1 mL aliquots were withdrawn from the release medium and replaced with the same volume of fresh buffer. The amount of PCL released and CB86 hydrolyzed were detected by HPLC (as described above).

Micelle storage stability

The micelle stability was followed at different storage conditions. A sample of each preparation (empty and loaded P-Mic and T-Mic) was stored as a micelle suspension at pH 7.4 for 1 mo at 4 °C, or as a lyophilized powder at −20 °C for 3 mo. Changes in micelle size and size distribution as well as polymer coagulation and drug precipitation were followed using DLS and HPLC as described above.

Micelle serum stability

For testing the micelle stability in the presence of blood proteins, empty and/or loaded P-Mic and T-Mic were incubated at 1.8 mM concentration in FBS for 24 h at 37 °C and then analyzed by DLS for possible changes in size distribution.

Endocytosis of micelles by LN 18 human gliobastoma cells

The LN 18 cells were grown on pre-sterilized glass cover slips placed on the bottom of a six well plate. After 24 h (at a confluence around 60%), they were washed once using complete medium (2 mL) and then incubated with 100 μL of empty and PCL-loaded Rh-PE-labeled micelles (0.5 mg polymer/mL medium) for 3, 6 and 12 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 (the required conditions for optimal cell growth). After incubation, the cells were washed 3 times with 2 mL of complete DMEM and then incubated for another 15 min with 2 mL of 100 nM Hoechst 3342. They were washed again with DMEM, and then three additional times with 2 mL of sterile HBS buffer, pH 7.4. The cover slips with the adherent cells were put face-down on glass slides (25×75×1.0 mm3; Microscope Slides Precleaned, Superfrost, Fisherbrand) with a drop of buffer and observed at 100× magnification on the fluorescence microscope29 with a Nikon Eclipse E400 Microscope (Nikon, Japan), using the UV-2B filter (for studying nuclei labeled with Hoechst) and TRICT filter (for Rh-PE micelles). Each time, pictures of bright field, nuclei, and internalized micelles were taken.

Micelle internalization into LN 18 cells by fluorescence spectroscopy

LN 18 glioblastoma cells were grown in 6-well plates (in DMEM complete medium) to reach 60% of confluence. To compare the rate of the internalization of different formulations, the cells were then incubated with empty and drug-loaded Rh-PE-labeled P-Mic and T-Mic (200 μL of micelles/2 ml of DMEM) for 3, 5, 7 and 8 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. At the determined time-points, they were washed as described in the previous paragraph, and lysed with 1 mL of 5N NaCl (1 h incubation with the cells). The fluorescence of the samples (depending on the amount of Rh-labeled cell-associated micelles) was measured at the excitation wavelength of 550 nm and emission wavelength of 590 nm using the Hitachi F-2000 fluorescence spectrometer (Hitachi, Japan). The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Pro-apoptotic activity of CB86-conjugated empty T-Mic

To test whether CB86-conjugated empty micelles by themselves demonstrate the pro-apoptotic activity, a preliminary study was done comparing the effect of the empty Rh-PE-labeled P-Mic and empty Rh-PE-labeled T-Mic after 26 h of incubation. The LN 18 cells were grown in flasks (to complete confluence) and then seeded on pre-sterilized glass cover slips (22 × 22 mm, FisherBrand) placed on the bottom of a six-well plate. They were treated as previously described for the study of the endocytosis, and then incubated with 200 μL (in 2 mL of the complete medium) of empty Rh-PE-labeled T-Mic (surface-conjugated with 13.6 μM of CB86) and empty Rh-PE-labeled P-Mic at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After incubation, the cover slips with attached cells were put face-down on the glass slides with mounting media (Fluormount-G, Southern Biotech). The images from the fluorescence microscope were taken at 40× magnification with the UV-2B filter and TRICT filter.

In vitro cytotoxicity

The in vitro cell viability test was performed with human glioblastoma LN 18 cells 30 which express the PBR on their mitochondria 31. Assay results were evaluated using the MTS test. LN 18 cells were grown in 75 cm2 flasks to complete confluence. Then, they were seeded (1×104 cells/well) in 96-well plates (Corning, Inc., NY) and kept for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The cells were washed with 100 μL/well of fresh DMEM complete medium and incubated with dilutions of free PCL, empty and PCL-loaded P-Mic, and empty and PCL-loaded T-Mic. The concentrations of incubated PCL (for all the preparations) and CB86 ranged from 14.90 nM to 402 nM and from 41 nM to 1.11 μM, respectively, while for the micelle-forming polymer concentration varied between 1.39 μM and 38.9 μM (see Table I). After an additional 72 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2, the cells were washed with DMEM, and incubated with 20 μL of MTS diluted in 100 μL of medium for about 2 h. MTS is chemically reduced by cells into formazan, which is soluble in the tissue culture medium. The cell viability was determined by measuring the absorbance of the produced formazan with an ELISA reader (Labsystems Multiscan MCC/340) at 492 nm and expressed as the percentage of live cells of the total non-treated cells. The cytotoxicity of different preparations was also evaluated to compare the IC50 values of PCL-containing micelle formulations with the free PCL, and calculated using the ED50 PLUS v.10 software. The P values were calculated with Graph Pad software and considered significant when ≤0.05.

Table I.

Summary of the concentrations of PCL, CB86 and polymer incubated with LN 18 cells

| Dilutions | PCL | CB86* | Micelle-forming polymer |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 14.90 nM | 41 nM | 1.39 μM |

| B | 44.69 nM | 123 nM | 4.22 μM |

| C | 134 nM | 370 nM | 12.8 μM |

| D | 402 nM | 1.11 3M | 38.9 μM |

Concentrations of each component used for the cytotoxicity studies for T-Mic incubated with LN 18 glioblastoma cells. The same concentration of PCL was used as the P-Mic and the free PCL, and the same concentration of CB86 has been used for empty and loaded T-Mic micelles. The amount of the micelle-forming PEG-PE polymer was comparable for all the micelle formulations (empty and loaded T-Mic and P-Mic).

This amount includes the total CB86 amount associated with the micelles, conjugated and not.

RESULTS

Micelle preparation, ligand attachment and drug loading

The T-Mic containing 10% (w/w) of p-NP-PEG2k-PE in their formulation were surface-modified according to the scheme shown in the Figure 1. The average conjugation yield was about 40% (CB86-ligand moles of the total available p-NP-PEG2k-PE moles) as determined by the HPLC (as described in “Material and Methods” section). To support the evidence for the conjugation of CB86 on the micelle surface, empty P-Mic (100% wt of PEG-PE) were prepared, and subsequently incubated with CB86/DMSO at the same molar ratio (16.5 mg of polymer/1.65 HBS buffer pH 7.5, and 2.06 mg of CB86/0.45% v/v of DMSO) at the same conditions used to make the empty T-Mic. The CB86 amount detected for empty P-Mic incubated with the PBR-ligand provided us the content of CB86 entrapped in the core of micelles or weakly bound on the surface non-covalently. About 20% of the total CB86 content was detected for empty T-Mic. Thus, the difference between the total CB86 amount calculated for T-Mic and P-Mic formulations gave us an average value for the PBR-ligand covalently attached on the micelle surface.

The drug loading (expressed as the amount of PCL associated with 1 mg of the micelle-forming material) was similar for T-Mic and P-Mic (1.28% or 128 ± 0.51 μg of PCL/mL of T-Mic vs 1.36% or 136 ±0.23 μg of PCL/mL of P-Mic).

Micelle size and zeta-potential

The size distributions and the mean diameters for T-Mic and P-Mic showed no significant differences among empty and loaded both plain and targeted micelles. The size distributions ranged between 9.5–18.8 nm for T-Mic and 8.7–18.6 nm for P-Mic (both empty and loaded) with a low polydispersity index.

The zeta potential for P-Mic (empty or loaded) was −7.23 mV compared to −0.18 mV for the T-Mic (empty or loaded), which was expected after the attachment of the CB86, PBR-ligand, on the micelle surface. See Table II for micelle properties.

Table II.

Summary of T-Mic and P-Mic micelle properties

| Size distribution (nm) | P.I.± S.D. (n=4) | ZP± S.D. (n=4) (−mV) | Loading±S.D. (n=4) (μgPCL/mlmicelles) | Conjugation (%molCB86/molp-NP-PEG-PE) (n=4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL-loaded P-Mic | 8.7–18.6 | 0.046±0.056 | 7.23±2.896 | 136±0.23 | - |

| PCL-loaded T-Mic | 9.5–18.8 | 0.104±0.028 | 0.18±0.931 | 128±0.51 | ca. 40* |

Summary of size distribution, polydispersity index (P.I.), zeta potential (ZP), loading (and their associated standard deviation, S.D.), and conjugation yield for the comparison between PCL-loaded P-Mic and T-Mic.

Includes non-covalently attached CB86 in T-Mic.

Critical micelle concentration (CMC)

The in vitro and in vivo stability of micelles depends on the corresponding CMC values. The low CMC value of the PEG2k-PE micelles (meaning a high stability) was demonstrated in previous studies 24, 32. Here, we compared the CMC values for empty P-Mic and T-Mic to confirm that the use of a small amount of organic solvent in micelle preparation at the end did not change their properties and stability. Indeed, for both preparations the CMC values were approximately 3×10−5 M.

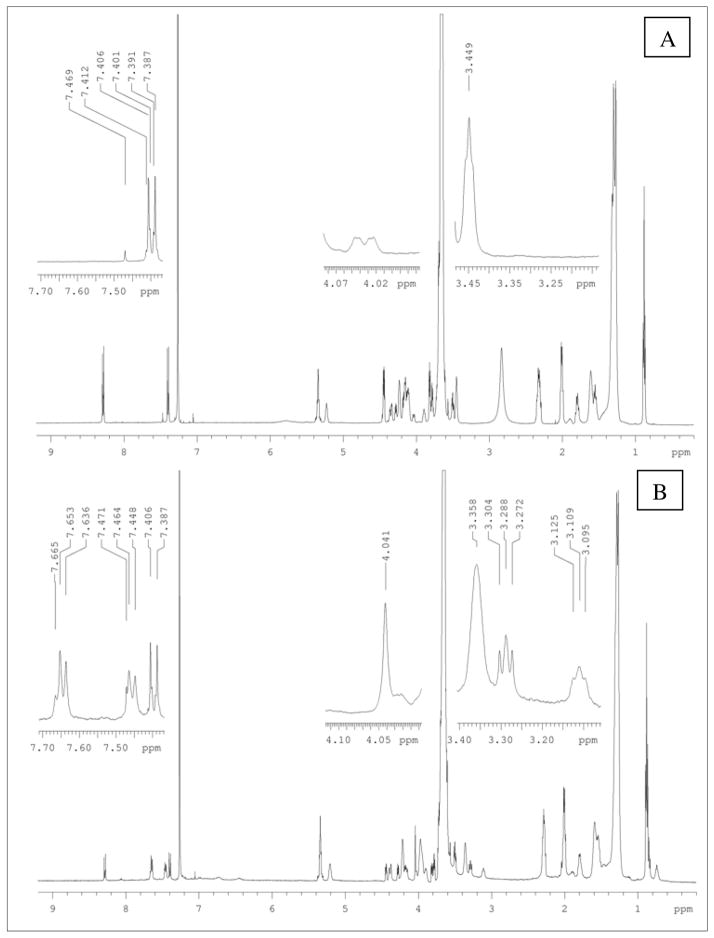

1H NMR and GPC analysis

…..For better characterization, the 1H NMR analysis was performed in CDCl3, to allow study of all the components forming the empty T-Mic: the hydrophilic PEG, the hydrophobic PE and the CB86. The related peaks are the following (d (ppm)): 0.69 (-CH3, CB86), 1.26 (-CH2-, PE), 3.11 (-CH2-N-, CB86), 3.28 (-CH2-N-, CB86), 3.5 and 3.6 (-CH2-, PEG), 4.04 (-CH-C=O, CB86), 7.4 –8.37 (Ar, pNP-), 7.48 –7.65 (Ar, CB86); see Figure 2 A and B. No significant chemical shifts were visible comparing the two spectra, perhaps due to weak changes in the electronic environment around the new bond. It also appeared that a portion of the pNP-groups in T-Mic was not completely hydrolyzed by the analysis time.

Figure 2.

A and B. 1H NMR (in CDCl3) of empty pNP-activated micelles (A) and empty T-Mic formulation (B). The insets highlight (for comparison between A and B in the same resonance areas) the characteristic peaks of CB86 absent in the corresponding precursor before the incubation with CB86.

With GPC analysis, the detection of the characteristic peak of the micelles (retention time around 9.30 minutes) at 254 nm (absorbance wavelength of the PBR-ligand) showed that CB86 is associated with the micelles, and additionally confirmed (together with size distribution analysis) that the low volume of the organic solvent used for making the empty and/or loaded T-Mic did not affect micelle integrity (profile not shown).

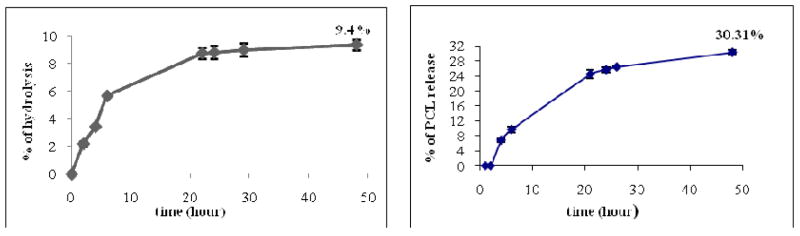

Drug release from PCL-loaded T-Mic and P-Mic

The drug release from P-Mic and T-Mic at sink conditions (48 h at 37 °C, and continuous shaking) showed that the maximum release of PCL from both P-Mic and T-Mic formulations was about 30% of the total incorporated drug after 48 h (Figure 3). The release was monitored by HPLC at 227nm. No significant differences were found between the PCL release from P-Mic and T-Mic.

Figure 3.

Left panel: kinetics of carbamate group hydrolysis of CB86 for empty T-Mic formulation. The kinetics was studied in HBS pH 7.4, at 37 °C and under continuous shaking for 48 h. Less than 10% of the total CB86 amount associated with the micelles was released in these conditions. Right panel: PCL release from T-Mic formulation. The release was studied in 1 M sodium salicylate, 37 °C, with continuous shaking for 48 h. Around 30% of PCL was released in this medium (able to increase its water solubility). The profile of PCL release from P-Mic (here not shown) is similar.

Kinetics of carbamate group hydrolysis

We also studied the stability of the bond between the CB86 and the micelles in the same conditions (HBS pH 7.4, 37 °C, continuous shaking). After a 48 h dialysis at sink conditions, we observed less than 10% of the initial ligand release (Figure 3). This small release (followed by the HPLC at 254 nm) may be due to the contribution of a certain amount of CB86 non-covalently and loosely associated with the micelle surface. This results highlight the good stability of the T-Mic formulation.

Micelle storage stability

The drug-loaded P-Mic and T-Mic were stable when stored as micelle suspension at 4 °C for 1 month and as a freeze-dried powder for 3 months at −20 °C. Neither precipitation of drug and/or CB86 hydrolysis nor micelle size/size distribution changes were observed during the storage period for either the micelle suspension or the micelle powder after re-hydration. Also, no degradation of PCL and CB86 occur during the storage, as confirmed by HPLC by comparison to the initial fresh formulations.

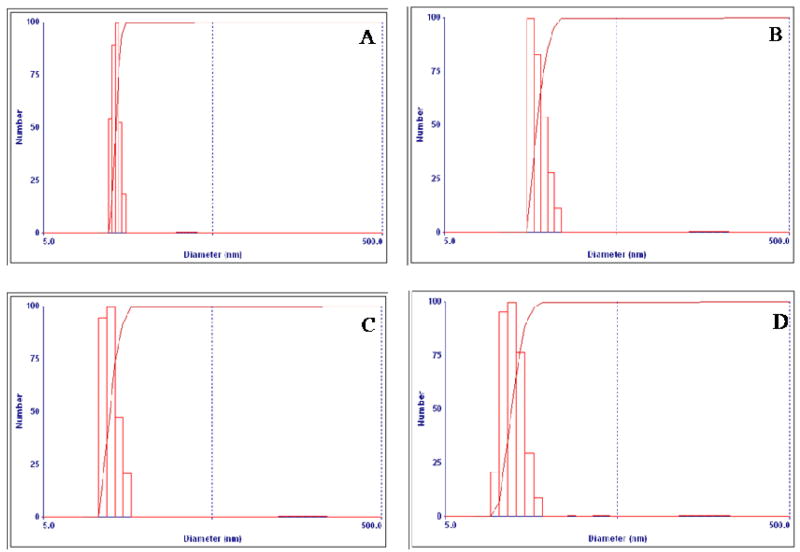

Micelle stability in FBS

Micelle stability in FBS was investigated at 37 °C for 24 h by comparing the micelle size and size distribution before and after incubating the empty and/or loaded T-Mic and the P-Mic with the serum. The polidispersity of the formulations was increased slightly, but no significant size alteration was found for either preparation. This means that these formulations protected their loading up to the moment of their uptake (certainly taking place in less than in 24 h). The stability of micelle size distribution was confirmed by DLS. The size distribution before and after serum incubation of PCL loaded T-Mic and P-Mic is shown, in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Size distribution of PCL-loaded P-Mic and T-Mic micelles before and after incubation in FBS. A and B images compare the PCL-loaded P-Mic formulation, C and D - the PCL-loaded T-Mic one. The micelles were incubated at a concentration of 1.8 mM in FBS for 24 h, at 37 °C. The micelle size was analyzed before and after incubation with serum by DLS. The polydispersity of the formulations was slightly increased, but no significant size alteration was noticed.

Internalization of micelles into LN 18 human glioblastoma cells by fluorescence microscopy and spectroscopy

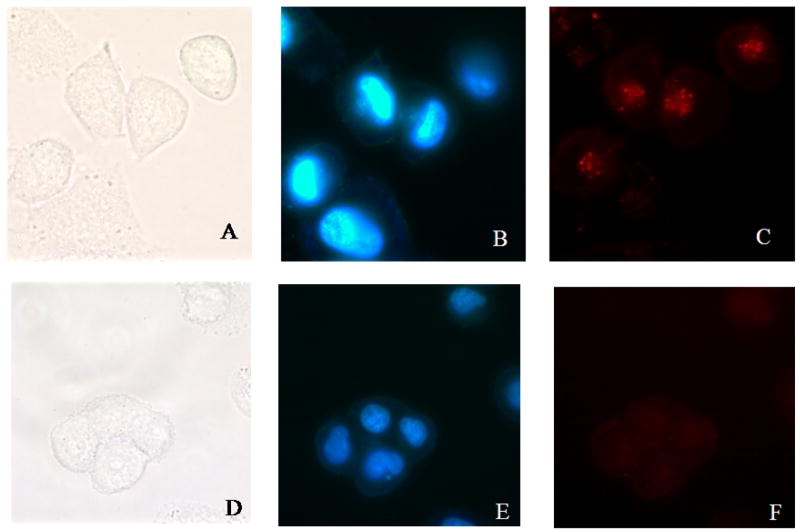

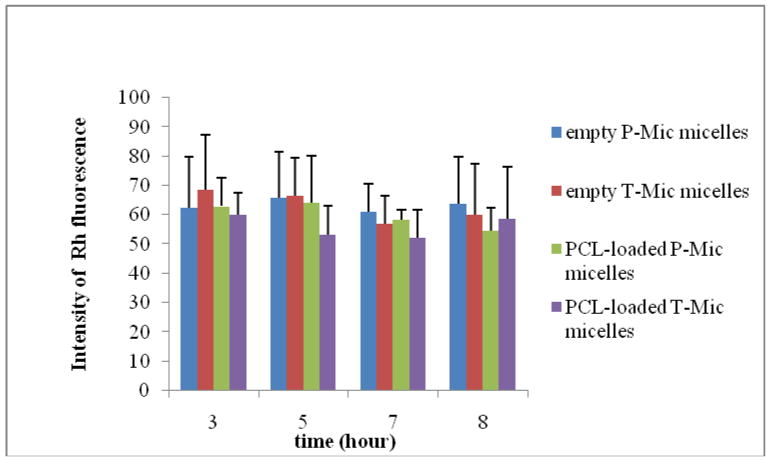

We have studied the uptake of empty P-Mic and T-Mic by LN 18 human glioblastoma cells in similar conditions. By fluorescence microscopy, we clearly observed the presence of all types of micelles (Rh-PE-labeled) inside living cells already after 3 h with no visible difference in the intensity of uptake between P-Mic and T-Mic. Figure 5 shows the uptake of empty P-Mic and T-Mic upon the 3 h incubation. For an additional comparison, the internalization was also studied by fluorescence spectroscopy. The cells were incubated with each of the micelle formulations, and lysed at determined time-points. Their content was analyzed for the intensity of the fluorescence (corresponding to the internalized rhodamine-labeled micelles). The higher the intensity, the greater is the amount of micelles internalized. As shown in Figure 6, there was no significant difference among the preparations. The micelles are completely taken up by the cells by 3 h.

Figure 5.

Endocytosis (observed with the fluorescence microscope, 100× magnification) of empty P-Mic (upper panel) and empty T-Mic (lower panel) micelles (100 μL of micelles/2 ml of DMEM) after a 3 h incubation with LN 18 human glioblastoma. A/D: bright field; B/E: Hoestch labeled nuclei; C/F: Rh-PE labeled internalized micelles into the cells. The picture shows that both formulations were taken up by the cells by 3 h.

Figure 6.

Internalization (calculated from the fluorescence spectroscopy data) of empty and PCL-loaded P-Mic and T-Mic micelles by the LN 18 cells. The cells were incubated for 3, 5, 7, and 8 h with 200 μl of Rh-labeled formulations (diluted up to 2ml of DMEM). They were then incubated with a 5 N NaCl to lyse the cells and analyze the amount of the micelles taken up by the cells. The fluorescence intensity of the samples was recorded at the excitation wavelength of 550 nm and emission wavelength of 590 nm. It is evident that all types of micelles were totally internalized already at 3 h incubation.

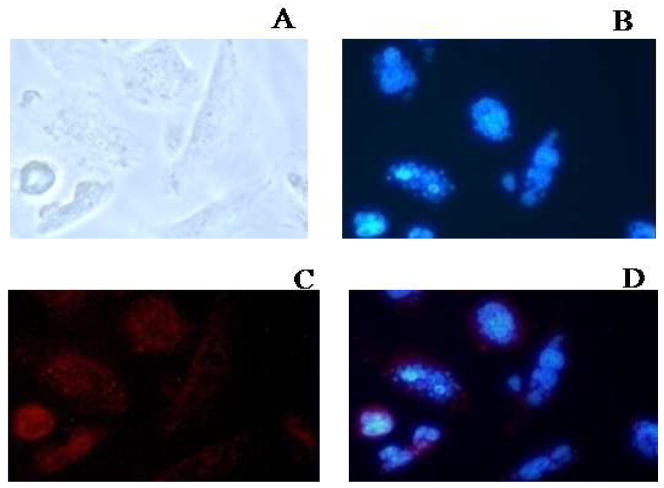

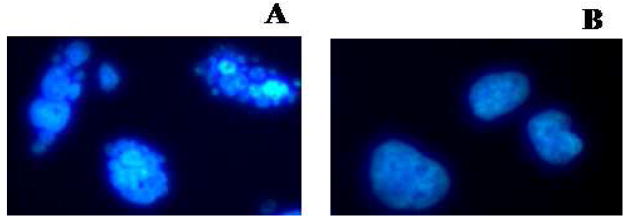

Pro-apoptotic activity of CB86 ligand-conjugated empty micelles

We tested the empty CB86 ligand-conjugated T-Mic for pro-apoptotic activity against LN 18 cells expressing the PBR receptor on their mitochondria. The tests were performed by comparison of the effect of the same amount (200 μL of micelles/2 mL complete DMEM medium) of empty P-Mic and T-Mic, the latter with 13.6 μM of CB 86. The CB86 concentration was determined by HPLC as previously described. Observing the nuclei with the fluorescence microscope, apoptosis was clearly visible after 26 h incubation. This process started in cells incubated with T-Mic (the formation of “blebs” because of the breaking of nuclei), but not in the case of P-Mic treatment (Figure 7 and 7 insert). This observation can be explained only by the pro-apoptotic activity of the PBR-ligand, CB86, after binding the PBR receptor that mediates the cascade of apoptosis.

Figure 7.

Pro-apoptotic activity after a 26 h incubation (observed with the fluorescence microscope, 40× magnification) of empty T-Mic micelles (200 μl micelles in 2ml of medium). A: bright field; B: Hoestch labeled nuclei; C: Rh-PE labeled T-Mic internalized into the cells; D: merge between B and C. In the panel B the portion of cells visible starting apoptosis is clearly.

Figure 7 insert.

Comparison of the effect of the 26 hour incubation of the same amount of empty T-Mic (on the left, A) and P-Mic (on the right, B) on the LN 18 nuclei. The pictures are a magnification of images taken at 40× magnification. On the left, the presence of blebs (irregular rounded spots due to broken chromatin indicating apoptosis) is clearly visible. On the right healthy round shaped cell nuclei are shown.

Cytotoxicity assay

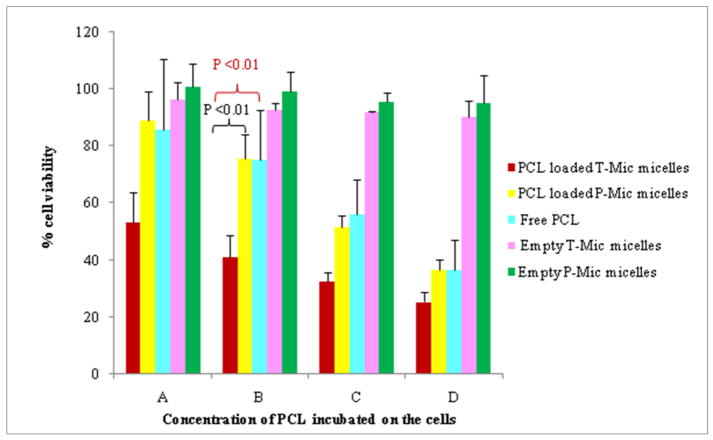

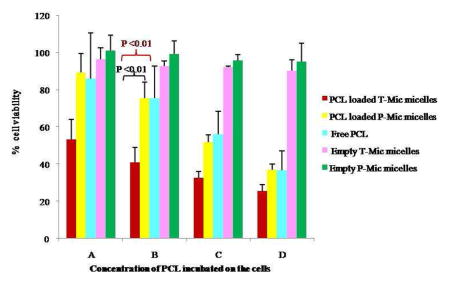

The glioblastoma LN 18 cell line was chosen for this study since it is known to express a high level of the PBR on its mitochondria. The cytotoxicity test showed the synergistic action of PCL and PBR-ligand of the T-Mic formulation in vitro, resulting in a significantly decreased viability of the cells treated with T-Mic compared to those treated with PCL-loaded P-Mic or free drug (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Viability on LN 18 cells after 72 hour incubation with PCL-loaded T-Mic, PCL-loaded P-Mic and free PCL. Empty T-Mic and P-Mic were used as positive controls. (PCL concentrations: A= 14.9 nM, B= 44.69 nM, C= 134 nM, D= 402 nM). The test has been performed 4 times, and P <0.01.

The IC50 values (as PCL quantity) determined for PCL-loaded T-Mic and P-Mic and for free PCL also support the presence of a synergistic effect for a PCL-loaded T-Mic formulation (Table III). In fact, the IC50 value of T-Mic micelles (175.1 nM) is much lower if compared to drug-loaded P-Mic and the free PCL.

Table III.

IC50 values

| IC50 | |

|---|---|

| FREE PCL | 271.1 nM |

| PCL-LOADED P-MIC | 267.0 nM |

| PCL-LOADED T-MIC | 175.1 nM |

Comparison of IC50 values related to the amount of PCL for the three preparations. (These values were calculated based on the results obtained from the cytotoxicity test. These values were derived from the data shown in the graph in Figure 8, n=4 and P <0.05).

DISCUSSION

We have shown that PCL-loaded micelles can be surface-modified with the PBR-ligand, CB86. The use of a small quantity of an organic solvent (DMSO) in the process of micelle preparation does not affect micelle integrity and properties. The comparison between the amount of CB86 associated with empty P-Mic incubated with the ligand at the same ratio and same conditions as used to prepare the T-Mic, confirmed the conjugation and provided us with its average yield. The NMR in CDCl3 characterized the T-Mic formulation in comparison to its precursor, and the GPC further demonstrated that the intact micelle structure is preserved after the contact with the organic solvent. Both, empty and loaded T-Mic and P-Mic demonstrate similar size, size distribution, PCL loading and release profiles, storage stability, and serum stability. The difference in their Zeta-potential can be attributed to the presence of the CB86 on the surface of T-Mic.

To test the hypothesis of a possible pro-apoptotic synergism between the PBR-ligand and the PCL, we chose LN 18 glioblastoma cell line as a model, since it expresses the PBR on its mitochondria. When studying the uptake of empty or loaded P-Mic and T-Mic by LN 18 cells, we observed good micelle uptake at 3 h without a visible difference between the two micellar preparations. At the same time, even empty T-Mic were clearly able to provoke the apoptosis in LN 18 cells as judged by the nuclear fragmentation in T-Mic-treated cells in contrast to the cells treated with P-Mic, confirming that the CB86, PBR-ligand, initiates apoptosis in cells over-expressing PBR on their mitochondria (Figure 7 and 7 insert).

This pro-apoptotic action of the PBR-ligand resulted in good synergism with PCL, when both agents were components of the same micellar formulation. The comparison of the cytotoxicity of PCL-loaded P-Mic and T-Mic confirmed the greater effective cell killing by T-Mic. The synergistic action was especially noticeable at the higher dilutions (as PCL) tested (from 402 nM to 14.9 nM of PCL), see Figure 8. A synergistic effect of the CB86 and PCL is also supported by the IC50 values determined for different preparations after normalization for PCL quantity. For the PCL-loaded T-Mic micelles it is 175.1 nM compared to 267.0 nM for P-Mic and 271.1 nM for the free PCL.

Thus, we have demonstrated with in vitro tests that the PCL-loaded PEG-PE-based micelles additionally modified with the PBR-ligand, CB86, i.e. PBR-targeted micelles expressed a significantly enhanced toxicity against human glioblastoma LN 18 cancer cells due to the synergistic effect of the PBR-ligand with PCL. PBR-targeted nanopreparations loaded with anti-cancer drugs should be considered potentially promising anti-tumor nanomedicines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grant RO1 EB001961 to Vladimir P. Torchilin. This study is also a part of the PhD thesis of TM.

Abbreviations

- PCL

paclitaxel

- PEG-PE

polyethylene glycol-phosphatidylethanolamine

- p-NP-PEG-PE

p-nitrophenyloxycarbonyl-PEG-PE

- Rh-PE

phosphatidylethanolamine lissamine rhodamine

- PBR

Peripheral Benzodiazepine Receptor

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- MTS

[3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium]

- HBS

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer saline

- NaCl

sodium chloride

- T-Mic

targeted micelles

- P-Mic

plain micelles

References

- 1.Papas S, Akoumianaki T, Kalogiros C, Hadjiarapoglou L, Theodoropoulos PA, Tsikaris V. Synthesis and antitumor activity of peptide-paclitaxel conjugates. J Pept Sci. 2007;13(10):662–71. doi: 10.1002/psc.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathew AE, Mejillano MR, Nath JP, Himes RH, Stella VJ. Synthesis and evaluation of some water-soluble prodrugs and derivatives of taxol with antitumor activity. J Med Chem. 1992;35(1):145–51. doi: 10.1021/jm00079a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singla AK, Garg A, Aggarwal D. Paclitaxel and its formulations. Int J Pharm. 2002;235(1–2):179–92. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00986-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szebeni J, Muggia FM, Alving CR. Complement activation by Cremophor EL as a possible contributor to hypersensitivity to paclitaxel: an in vitro study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(4):300–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.4.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss RB, Donehower RC, Wiernik PH, Ohnuma T, Gralla RJ, Trump DL, Baker JR, Jr, Van Echo DA, Von Hoff DD, Leyland-Jones B. Hypersensitivity reactions from taxol. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8(7):1263–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torchilin VP. Recent approaches to intracellular delivery of drugs and DNA and organelle targeting. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2006;8:343–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torchilin VP. Micellar nanocarriers: pharmaceutical perspectives. Pharm Res. 2007;24(1):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torchilin VP. Targeted pharmaceutical nanocarriers for cancer therapy and imaging. Aaps J. 2007;9(2):E128–47. doi: 10.1208/aapsj0902015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: a review. J Control Release. 2000;65(1–2):271–84. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torchilin VP, Lukyanov AN, Gao Z, Papahadjopoulos-Sternberg B. Immunomicelles: targeted pharmaceutical carriers for poorly soluble drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(10):6039–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoo HS, Park TG. Folate receptor targeted biodegradable polymeric doxorubicin micelles. J Control Release. 2004;96(2):273–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papadopoulos V, Amri H, Li H, Boujrad N, Vidic B, Garnier M. Targeted disruption of the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor gene inhibits steroidogenesis in the R2C Leydig tumor cell line. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(51):32129–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anholt RR, De Souza EB, Oster-Granite ML, Snyder SH. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors: autoradiographic localization in whole-body sections of neonatal rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985;233(2):517–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decaudin D. Peripheral benzodiazepine receptor and its clinical targeting. Anticancer Drugs. 2004;15(8):737–45. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200409000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McEnery MW, Snowman AM, Trifiletti RR, Snyder SH. Isolation of the mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptor: association with the voltage-dependent anion channel and the adenine nucleotide carrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(8):3170–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chelli B, Lena A, Vanacore R, Da Pozzo E, Costa B, Rossi L, Salvetti A, Scatena F, Ceruti S, Abbracchio MP, Gremigni V, Martini C. Peripheral benzodiazepine receptor ligands: mitochondrial transmembrane potential depolarization and apoptosis induction in rat C6 glioma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68(1):125–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casellas P, Galiegue S, Basile AS. Peripheral benzodiazepine receptors and mitochondrial function. Neurochem Int. 2002;40(6):475–86. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(01)00118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maaser K, Grabowski P, Oezdem Y, Krahn A, Heine B, Stein H, Buhr H, Zeitz M, Scherubl H. Up-regulation of the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor during human colorectal carcinogenesis and tumor spread. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(5):1751–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torchilin VP, Levchenko TS, Lukyanov AN, Khaw BA, Klibanov AL, Rammohan R, Samokhin GP, Whiteman KR. p-Nitrophenylcarbonyl-PEG-PE-liposomes: fast and simple attachment of specific ligands including monoclonal antibodies to distal ends of PEG chains via p-nitrophenylcarbonyl groups. Novel 2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine derivatives as potent and selective ligands for peripheral benzodiazepine receptors: synthesis, binding affinity, and in vivo studies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1511(2):397–411. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(01)00165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trapani G, Franco M, Latrofa A, Ricciardi L, Carotti A, Serra M, Sanna E, Biggio G, Liso G. Novel 2-Phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine Derivatives as Potent and Selective Ligands for Pheripheral Benzodiazepine Receptors: Synthesis, Binding Affinity, and in Vivo Studies. J Med Chem. 1999;42(19):3934–41. doi: 10.1021/jm991035g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trapani G, Laquintana V, Denora N, Trapani A, Lopedota A, Latrofa A, Franco M, Serra M, Pisu MG, Floris I, Sanna E, Biggio G, Liso G. Structure-activity relationships and effects on neuroactive steroid synthesis in a series of 2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridineacetamide peripheral benzodiazepine receptors ligands. J Med Chem. 2005;48(1):292–305. doi: 10.1021/jm049610q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trapani G, Laquintana V, Latrofa A, Ma J, Reed K, Serra M, Biggio G, Liso G, Gallo JM. Peripheral benzodiazepine receptor ligand-melphalan conjugates for potential selective drug delivery to brain tumors. Bioconjug Chem. 2003;14(4):830–9. doi: 10.1021/bc034023p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lukyanov AN, Gao Z, Torchilin VP. Micelles from polyethylene glycol/phosphatidylethanolamine conjugates for tumor drug delivery. J Control Release. 2003;91(1–2):97–102. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00217-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lukyanov AN, Torchilin VP. Micelles from lipid derivatives of water-soluble polymers as delivery systems for poorly soluble drugs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56(9):1273–89. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lukyanov AN, Elbayoumi TA, Chakilam AR, Torchilin VP. Tumor-targeted liposomes: doxorubicin-loaded long-circulating liposomes modified with anti-cancer antibody. J Control Release. 2004;100(1):135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones M, Leroux J. Polymeric micelles - a new generation of colloidal drug carriers. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 1999;48(2):101–11. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(99)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.La SB, Okano T, Kataoka K. Preparation and characterization of the micelle-forming polymeric drug indomethacin-incorporated poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(beta-benzyl L-aspartate) block copolymer micelles. J Pharm Sci. 1996;85(1):85–90. doi: 10.1021/js950204r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho YW, Lee J, Lee SC, Huh KM, Park K. Hydrotropic agents for study of in vitro paclitaxel release from polymeric micelles. J Control Release. 2004;97(2):249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torchilin VP. Fluorescence microscopy to follow the targeting of liposomes and micelles to cells and their intracellular fate. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57(1):95–109. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hans G, Wislet-Gendebien S, Lallemend F, Robe P, Rogister B, Belachew S, Nguyen L, Malgrange B, Moonen G, Rigo JM. Peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR) ligand cytotoxicity unrelated to PBR expression. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69(5):819–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veenman L, Levin E, Weisinger G, Leschiner S, Spanier I, Snyder SH, Weizman A, Gavish M. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor density and in vitro tumorigenicity of glioma cell lines. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68(4):689–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dabholkar RD, Sawant RM, Mongayt DA, Devarajan PV, Torchilin VP. Polyethylene glycol-phosphatidylethanolamine conjugate (PEG-PE)-based mixed micelles: some properties, loading with paclitaxel, and modulation of P-glycoprotein-mediated efflux. Int J Pharm. 2006;315(1–2):148–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]