Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) constitutes a rising threat to public health. Despite extensive research in cellular and animal models, identifying the pathogenic agent present in the human brain and showing that it confers key features of AD have not been achieved. We extracted soluble amyloid β–protein (Aβ) oligomers directly from the cerebral cortex of typical AD subjects. The oligomers potently inhibited long term potentiation (LTP), enhanced long term depression (LTD), and reduced dendritic spine density in normal rodent hippocampus. Soluble Aβ from AD brain also disrupted the memory of a learned behavior in normal rats. These various effects were specifically attributable to Aβ dimers. Mechanistically, metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) were required for LTD enhancement and NMDA receptors (NMDAR) for spine loss. Co-administering antibodies to the Aβ N-terminus prevented the LTP and LTD deficits, whereas antibodies to the mid-region or C-terminus were less effective. Insoluble amyloid plaque cores from AD cortex did not impair LTP unless they were first solubilized to release Aβ dimers, suggesting that plaque cores are largely inactive but sequester Aβ dimers that are synaptotoxic. We conclude that soluble Aβ oligomers extracted from AD brains potently impair synapse structure and function and that dimers are the smallest synaptotoxic species.

AD is distinguished histopathologically from other dementias by abundant extraneuronal deposits of amyloid β-protein (Aβ). Numerous reports describe neuronal alterations induced by supraphysiological concentrations of synthetic Aβ peptides, by Aβ species secreted by cultured cells, or by complex mixtures of Aβ assembly forms in the brains of APP transgenic mice1–5. While these findings demonstrate that Aβ can alter synapse physiology in experimental models, the nature of the pathogenic species in the human brain and direct demonstration of its neurobiological effects are unresolved.

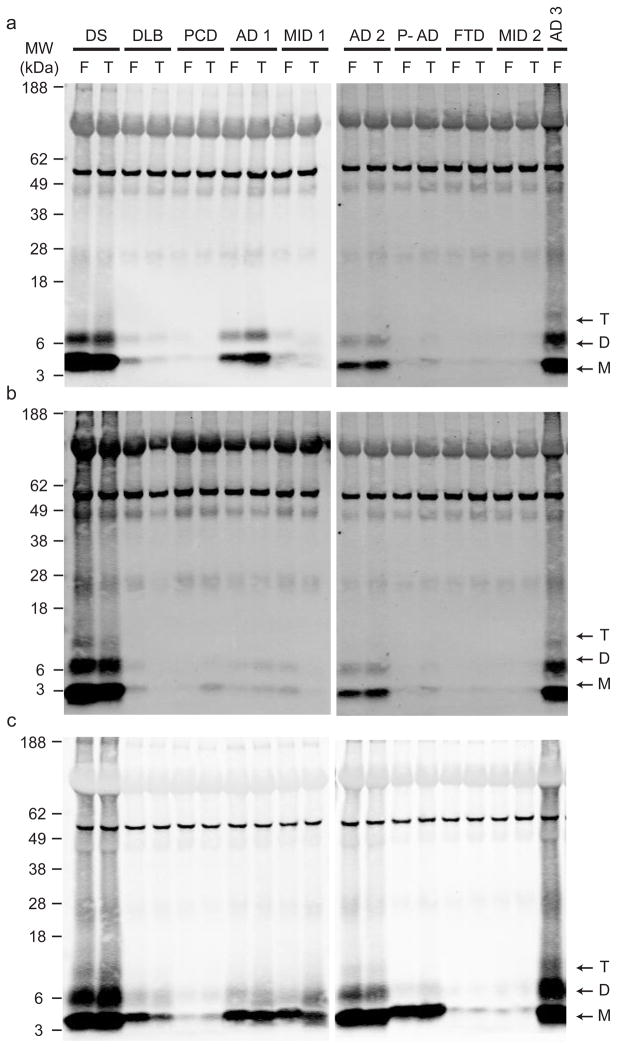

Aqueously soluble (Tris-buffered saline (TBS)), detergent-soluble (TBS+1% Triton) and “insoluble” (5M GuHCl) extracts were prepared by sequential centrifugation of brain homogenates from humans with various neuropathologically confirmed dementias (Supp. Table 1a). Sensitive immunoprecipitation/Western blotting (IP/WB)5,6 revealed Aβ monomers and lithium dodecylsulfate (LDS)-stable dimers and trimers in all three extracts of the frontal and temporal cortices of AD subjects and an adult with Down’s syndrome and AD (Fig. 1). Cortical extracts from some non-AD subjects showed modest levels of Aβ in the insoluble (GuHCl) extracts (Fig. 1c,) but little or none in the soluble (TBS) extracts (Fig. 1a) compared to the AD cases. Notably, a subject with AD histopathology but no clinical AD (pathological AD, P-AD) showed Aβ in the insoluble but not the soluble fraction. While Aβ was detectable in all three sequential extracts, we chose to characterize the physiologic effects of the TBS-soluble fraction because AD dementia correlates strongly with soluble Aβ levels7–9. Indeed, the profile of our extracts suggested that levels of TBS-soluble Aβ correlated best with the clinical AD state (Fig. 1a vs. c). Moreover, we wished to focus on the earliest Aβ assemblies: soluble oligomers that form initially from monomers.

Figure 1.

Monomeric and oligomeric Aβ is detected in brain extracts of humans with clinically and neuropathologically typical late-onset AD. IP/WB analysis (see Methods) was performed on supernatants of the soluble (a, TBS), membrane-associated (b, TBS-TX100) and insoluble (c, GuHCl) sequential extracts of frontal (F) and temporal (T) cortex homogenates from various individuals diagnosed with different forms of dementia (see Supp. Table 1). Samples were IP’ed with polyclonal Aβ antibody R1282 and blotted with monoclonals 2G3 (Aβ40) + 21F12 (Aβ42). Subject key: DS, Down’s syndrome with AD; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; PCD, paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; MID, multi-infarct dementia; P-AD, “pathological AD” (i.e., scattered amyloid plaques without a history of clinical AD); FTD, frontotemporal dementia. See Supp. Table 1a for further information.

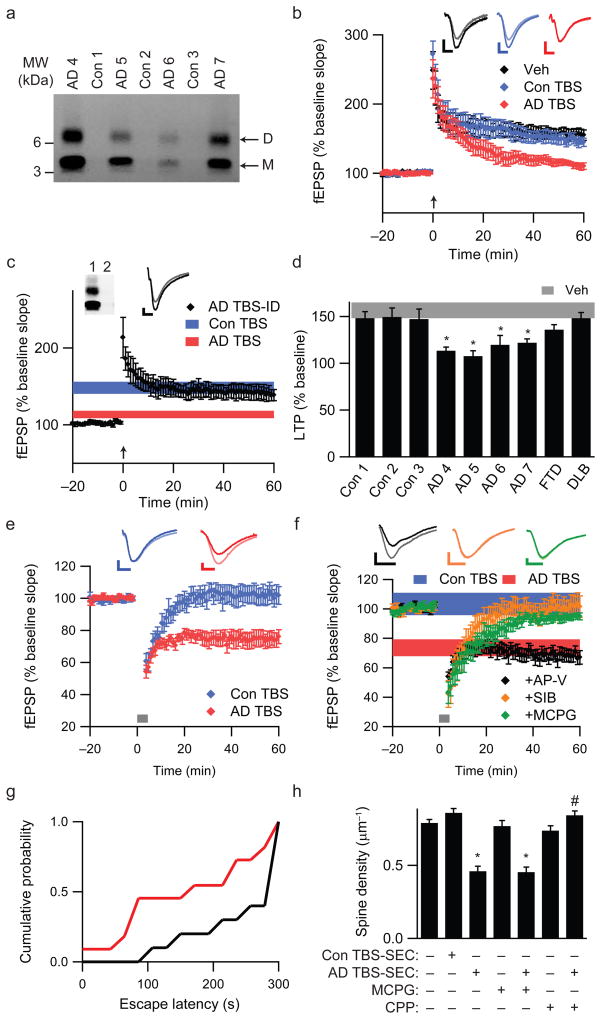

We first asked whether soluble Aβ from AD cortex (Fig. 2a; Supp. Table 1b) alters long-term potentiation (LTP) in mouse hippocampus. TBS extracts from control (Con TBS) or AD (AD TBS) cortex did not alter basal synaptic transmission or paired-pulse ratio (Supp. Figs. 1a,b), indicating that neurotransmitter release probability was unaffected10. Slices exposed to TBS vehicle (Veh) or Con TBS for 20 minutes exhibited robust LTP induction following high-frequency stimulation (HFS) (152.9 ± 9.1% and 144.2 ± 7.1% of baseline fEPSP slope, respectively) (Fig. 2b). In contrast, AD TBS inhibited LTP (111.3 ± 3.9%, P<0.05) (Fig. 2b). Immunodepleting AD TBS with an Aβ antiserum (R1282) prevented the LTP inhibition (Fig. 2c), indicating that Aβ was necessary. The effect of AD TBS on LTP was strongly dose-dependent (Supp. Fig. 1d). Importantly, TBS extracts prepared identically from FTD or DLB cortices did not significantly alter LTP (137.0 ± 5.3% and 148.1 ± 6.1%, respectively) (Fig. 2d; Supp. Fig. 1e). Additional brain extracts from two control and three AD subjects fully replicated the above findings (Figs. 2a,d).

Figure 2.

Soluble Aβ extracted from AD brain alters hippocampal synapse physiology and learned behavior. (a) IP/WB of the TBS brain extracts used to study LTP. Clinical and neuropathological diagnoses for each of these seven cases are provided in Supp. Table 1b. (b) Summary data of LTP induction following two 100 Hz stimuli (HFS, arrow) of slices treated with 500 μL each of TBS vehicle (Veh; n=8 slices), Con 1 TBS extract (Con TBS; n=6) or AD 4 TBS extract (AD TBS; n=8). Insets show average baseline (light) and post-HFS (dark) fEPSP traces; calibration bars 5 msec/0.2 mV. (c) LTP is induced normally in hippocampal slices treated with 500 μL of immunodepleted AD TBS (AD TBS-ID). The summary LTP data for Con TBS (blue, n=6 slices) and AD TBS (red, n=8 slices) from Fig. 2b are represented as horizontal bars depicting means ± SEMs of fEPSP slopes at ~50–60 min post-HFS. Inset: Two sequential IP’s (R1282) of AD TBS blotted with 2G3+21F12. (d) Summary LTP data (means ± SEMs) for 3 different control subjects (Con 1, n=6; Con 2, n=6; Con 3, n=6), 4 AD subjects (AD 4 n=8; AD 5, n=5; AD 6, n=6; AD 7, n=6), 1 FTD subject (n=5) and 1 DLB subject (n=6). For comparison, LTP data from Fig. 2b for Veh are represented by the grey horizontal bar. *P<0.05 compared with Veh. (e) Summary LTD data for slices treated with 500 μL Con TBS (blue, n=7) or AD TBS (red, n=8) for 10 min prior to a weak stimulation protocol of 300 pulses at 1 Hz, indicated by the small grey bar. Calibration bars 5 msec/0.2 mV. (f) Summary LTD data for co-administration of AD TBS with either 50 μM AP-V (black, n=8), 500 μM (R/S)-MCPG (green, n=7) or 3 μM SIB1757 (orange, n=6). For comparison, LTD data (means ± SEM) for Con TBS (blue) and AD TBS (red) are shown as horizontal bars. (g) Cumulative probability distribution representing escape latency for animals receiving AD TBS (red) or AD TBS-ID (black) at 48 hr after training. Animals receiving AD TBS had a significantly shorter mean escape latency than animals receiving AD TBS-ID (174 ± 31.7 sec and 255 ± 22.8 sec, respectively; P<0.05; n=11 and 10 rats). h. Summary spine density data for pyramidal cells exposed to SEC-enriched TBS extract from AD brain (AD TBS-SEC) or from Con brain (Con TBS-SEC) and also for slices treated with 500 μM MCPG or 20 μM CPP in the presence or absence of AD TBS-SEC. *,#P<0.05 vs. Con TBS-SEC and vs. AD TBS-SEC, respectively.

Long-term depression (LTD) of hippocampal synapses is induced by repetitive subthreshold stimulation11. Standard protocols for LTD induction in adult rodent hippocampus require delivery of 600–900 pulses at low frequency12,13. Accordingly, 300 pulses at 1 Hz failed to induce LTD in the presence of vehicle or Con TBS (Fig. 2e). However, AD TBS facilitated LTD induction by this weak stimulus (74.7 ± 4.8% of baseline for AD TBS vs. 101.9 ± 5.6% for Con TBS, P<0.05) (Fig. 2e). LTD induced with AD TBS was NMDAR-independent, as the NMDAR antagonist AP-V did not block this effect (68.1 ± 4.3%) (Fig. 2f). However, both MCPG, a Group I/II mGluR antagonist (94.8 ± 2.4%, P<0.05), and SIB1757, an mGluR5 antagonist (101.1 ± 6.9%, P<0.05), prevented LTD facilitation by AD TBS (Fig. 2f). Whereas mGluR activation was necessary for the LTD facilitation by soluble Aβ, SIB1757 did not prevent AD TBS-mediated LTP inhibition (Supp. Fig. 1f). This finding is consistent with earlier data that Aβ can influence synaptic plasticity through various receptors, including NMDAR, mGluR and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors14–17.

Passive administration of monoclonal Aβ antibodies has entered human testing. We found that the ability of a co-administered Aβ antibody to block the above LTD facilitation correlated with its ability to IP soluble Aβ from AD TBS (Supp. Fig. 2). Antibodies to the free N-terminus of Aβ (3D6; 82E1) almost completely precipitated soluble Aβ from AD TBS and also prevented the LTD facilitation (98.4 ± 3.0%), whereas antibodies to the Aβ C-termini (2G3, 21F12) weakly precipitated Aβ and did not block the LTD effect (72.1 ± 4.9%) (Supp. Fig. 2a,b). Aβ mid-region antibodies IP’d a fraction of the Aβ species in AD TBS and only partially blocked the LTD effect (Supp. Figs. 2a, c). Similarly, N-terminal but not C-terminal antibodies neutralized the LTP deficit (Supp. Fig. 2d).

To assess the effects of soluble AD cortical extracts directly on memory function, rats were trained on a step-through passive avoidance task18. At 0, 3 or 6 hr post-training, AD TBS or R1282-immunodepleted AD TBS (AD TBS-ID) (Supp. Fig. 3a) was microinjected into the lateral ventricle. AD TBS administered 3 hr post-training significantly impaired the animals’ recall of the learned behavior 48 hr later (Fig. 2g). The latency to enter the dark chamber, where the rat had received a shock during training, was significantly shorter for animals injected with AD TBS than with AD TBS-ID. Notably, AD TBS injected at 0 or 6 hr after training did not significantly alter the escape latency (Supp. Fig. 3). The 3 hr post-training time point at which AD TBS significantly impaired recall is consistent with the temporal pattern of transcriptional regulation of synapse remodelling following passive avoidance training19.

Decreased synapse density is the strongest neuropathological correlate of the degree of dementia in AD20. To determine whether soluble Aβ in AD brain contributes directly to synapse loss, we quantified dendritic spine density in GFP-transfected pyramidal cells in organotypic rat hippocampal slices21. To properly reconstitute brain extracts in slice culture medium, TBS extracts underwent non-denaturing size exclusion chromatography (SEC). Pyramidal neurons in slices cultured for 10 days with plain medium (sham) or medium reconstituted with lyophilized SEC fractions of Con TBS (Con TBS-SEC) displayed similar spine densities (0.79 ± 0.02 and 0.86 ± 0.03 spines/μm, n=6/890 and 5/628 cells/spines, respectively). In contrast, slice medium reconstituted with SEC fractions from AD TBS (AD TBS-SEC) caused a 47% decrease in spine density vs. Con TBS-SEC (0.46 ± 0.03 spines/μm, P<0.05; n=6/517) (Fig. 2h; Supp. Fig. 4). MCPG did not prevent the loss of spines with AD TBS-SEC treatment (0.45 ± 0.03 spines/μm; n=5/337) (Fig. 2h). CPP, an NMDAR antagonist, did not alter spine density when applied alone but prevented the decrease observed with AD TBS-SEC (0.73 ± 0.03 and 0.84 ± 0.03, respectively; n=5/619 and 5/748; P<0.05 for AD TBS-SEC alone vs. AD TBS-SEC with CPP) (Fig. 2h). These findings support prior evidence that NMDAR activation is necessary for Aβ-mediated spine loss16,17.

We next asked which soluble Aβ species present in AD brain mediated these effects on synapse physiology. Two lines of evidence indicated that the Aβ-immunoreactive species migrating at 8 kDa on LDS-PAGE gels were true Aβ dimers. First, mass spectrometry of the 4 and 8 kDa bands IP’d from the GuHCl extract of AD cortex confirmed that each contained tryptic peptides of human Aβ (Supp. Fig. 5b–e). Second, IP of this extract with an Aβ40-specific antibody (2G3) and WB with an Aβ42-specific antibody (21F12) revealed an Aβ40/42 heterodimer migrating at 8 kDa (Supp. Fig. 5a). Performing this co-IP using 21F12 for both IP and WB yielded a much stronger dimer signal, indicating that most of the 8 kDa species are Aβ42/42 homodimers (Supp. Fig. 5a).

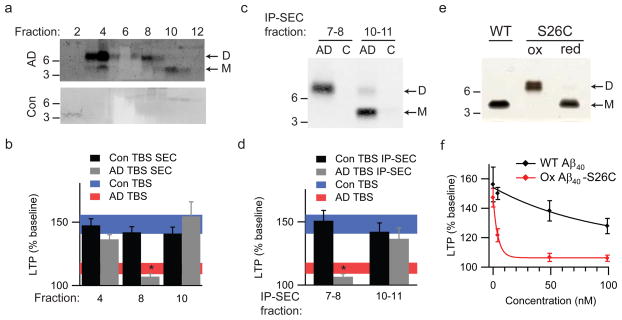

Having confirmed that the 8 kDa bands detected by WB in AD brain samples (Figs. 1 and 2a) are bona fide Aβ dimers, we used non-denaturing SEC to separate the various Aβ species in AD TBS and characterized their respective effects on LTP. Most of the Aβ in AD TBS eluted in the void volume (>60 kDa, based on co-eluting linear polydextran standards22), but this higher MW complex dissociated into Aβ monomers and dimers when denatured by LDS-PAGE (Fig. 3a, fractions 3–4). The SEC profile also showed dimers eluting at ~8–16 kDa (fractions 7–8) and monomers at ~3–6 kDa (fractions 10–11). Taken together, these results indicate that in AD cortex, soluble Aβ exists in various assemblies, with the smallest native oligomer being a dimer.

Figure 3.

Soluble dimers are the smallest Aβ assembly form in human brain to acutely perturb synapse physiology. (a) TBS extracts of AD (top panel) and control (bottom panel) brains were subjected to non-denaturing SEC. SEC fractions were lyophilized and WB’d with 2G3+21F12; molecular weights (in kDa) on left. Note that Aβ monomer and dimer in the AD TBS extract is recovered from material that elutes at the end of the void volume (fractions 3/4). Control (Con) brain extracts were devoid of Aβ. (b) Summary LTP data (means ± SEMs) for slices treated with SEC fractions from AD or Con TBS extracts (n=6 slices for all samples), as characterized in Fig. 3a. (c) Representative WB (2G3+21F12) of IP-SEC fractionation of AD TBS and Con TBS. TBS extracts (500 μL) were immunoprecipitated with 3D6 (3 μg/mL), eluted with sample buffer and subjected to SEC. Dimer-enriched (fractions 7–8) and monomer-enriched (fractions 10–11) IP-SEC fractions were separately pooled, as were corresponding fractions from Con TBS. (d) Summary LTP data (means ± SEMs) for slices treated with IP-SEC fractions of AD and control brain TBS extracts, as characterized in Fig. 3c (Con fractions 10–11, n=5; AD fractions 10–11, n=5; Con fractions 7–8, n=7; AD fractions 7–8, n=7). (e) Mutant Aβ40-S26C forms dimers under oxidizing conditions (ox), which can be reduced to monomers by treating with β-ME (red). Silver stain was performed with 100 ng wildtype Aβ40 (wt) peptide or the mutant peptide (f) Summary LTP data (means ± SEMs) for slices treated with 5, 50, or 100 nM of either wt Aβ40 (black) or oxidized Aβ40-S26C (red) reveals that the oxidized Aβ40-S26C dimer inhibits LTP with much greater potency (100 nM Aβ40-S26C, n=4; n=5 for all other treatments). The vehicle controls (plotted at 0 nM) were 50 mM ammonium acetate (n=4) for the S26C peptide and 0.1% ammonium hydroxide (n=4) for wt peptide.

To establish which soluble Aβ species were responsible for the impaired synaptic plasticity, SEC fractions of AD TBS containing either higher MW complexes (AD SEC 4), native Aβ dimers (AD SEC 8) or monomers (AD SEC 10) were each tested separately. Only AD SEC 8 significantly inhibited LTP (107.0 ± 2.2%; P<0.05 vs. Con TBS), whereas AD SEC 4, AD SEC 10, and identically prepared fractions from Con TBS were all inactive (Fig. 3b). Notably, AD SEC 4 fraction contained the highest concentration of Aβ (Fig. 3a), suggesting that the specific activity of this higher MW Aβ assembly is very low. To achieve a purer preparation of Aβ dimers, AD TBS was IP’d with 3D6, eluted with denaturing LDS buffer and subjected to SEC (IP-SEC) (Fig. 3c). Most of the soluble Aβ now eluted at the size of dimers (fractions 7–8) rather than in the void volume (Supp. Fig. 6), suggesting that elution with LDS disrupts non-covalent interactions among the higher MW Aβ assemblies. LTP was significantly inhibited by IP-SEC fractions 7–8, containing Aβ dimers (106.6 ± 2.4%, P<0.05), but not by fractions 10–11 containing monomers nor by any IP-SEC fractions from Con TBS (Fig. 3d).

Although these SEC experiments show that soluble Aβ dimers inhibit LTP, it remained possible that a small molecule from human brain was bound to the Aβ dimers and was required to impair LTP. To address this possibility, we generated a synthetic Aβ40 peptide in which serine 26 was mutated to cysteine (Aβ40-S26C). An Aβ dimer was observed upon oxidation (Fig. 3e), and this inhibited LTP nearly 20-fold more potently than did wild-type synthetic Aβ40 (Fig. 3f). This pure, synthetic dimer cannot contain any other factors present in AD TBS, establishing that Aβ dimers alone are sufficient to perturb synapse physiology.

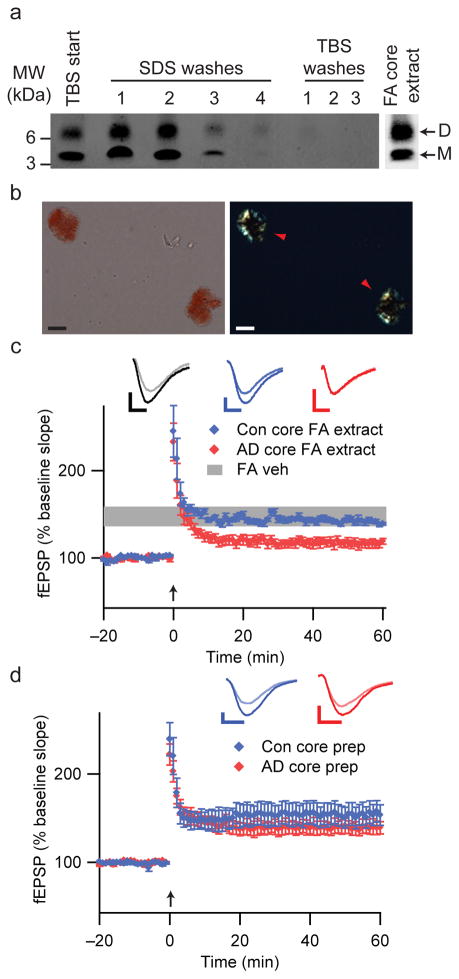

Previous studies suggested that unlike soluble Aβ levels, amyloid plaque burden correlates poorly with AD severity7,9,20. We asked whether insoluble amyloid cores isolated from AD cortex can inhibit hippocampal LTP. To isolate these detergent-resistant foci of fibrillar Aβ from neuritic plaques23–25, we homogenized TBS-insoluble pellets of plaque-rich AD cortex in 2% SDS24. IP/WB of supernatants after washing in SDS buffer showed that no additional Aβ was liberated by SDS or TBS from this preparation (Fig. 4a). Congo red staining of the residual pellet revealed intact amyloid cores displaying characteristic birefringence (Fig. 4b). Although resistant to disruption by many solvents, AD amyloid cores are efficiently solubilized by formic acid23,24. This treatment released Aβ dimers and monomers from the washed cores (Fig. 4a). When this formic acid extract of the AD core prep was applied to hippocampal slices, LTP was inhibited (116.2 ± 4.6%, P<0.05 vs. formic acid vehicle; Fig. 4c). Formic acid extracts of identically prepared fractions from control brain allowed normal LTP (Fig. 4c). Thus, amyloid cores contain Aβ dimers that can impair synaptic plasticity. In contrast, addition of intact cores (Fig. 4b) to the ACSF perfusate did not affect LTP (139.4 ± 7.6%, Fig. 4d). Therefore, in physiologic buffer (ACSF), amyloid cores do not acutely release soluble Aβ dimers to alter synaptic plasticity. IP/WB analyses revealed that Aβ dimers also were not released from amyloid cores incubated in physiological buffers at 37°C for 24 hr (Supp. Fig. 7), suggesting that highly insoluble Aβ aggregates such as amyloid plaque cores represent dimer-rich structures that do not readily dissociate.

Figure 4.

Insoluble amyloid cores contain Aβ dimers with synaptotoxic potential but are not readily released. (a) IP/WB of sequential extracts of the TBS-insoluble pellet prepared from 100 mg of a plaque-rich AD brain (case AD 5 from Fig. 2a) (see Methods). The final TBS washes reveal that no additional soluble Aβ can be extracted from the pellet after 4 sequential SDS washes. The remaining core-rich pellet was then incubated in formic acid (FA core extract) and analyzed by IP/WB, revealing that the insoluble cores contain Aβ monomers and dimers (far right lane). (b) Core preps following the final TBS wash as in Fig. 4a were stained with 0.2% Congo red and visualized by brightfield (left) and polarization (right) microscopy. Isolated amyloid cores display characteristic birefringence with Congo red (red arrowheads). Material prepared similarly from Con 3 (Fig. 2a) did not contain any such structures. Scale bar = 5 μm. (c) Cores prepared as in Figs. 4a, b were extracted with 88% formic acid and neutralized with NaOH. Summary LTP data for slices treated with just FA/NaOH vehicle (FA Veh, n=5), or with FA/NaOH core extracts from AD (AD core FA extract, n=7) or control (Con core FA extract, n=5) brains. Calibration bars, 5 msec/0.2 mV. (d) Summary LTP data for slices exposed to intact core preps isolated as in Fig. 4a, b from 100 mg AD cortex (AD core prep, n=5) or Con cortex (Con core prep, n=5). Calibration bars, 5 msec/0.3 mV.

Here, we show that soluble Aβ isolated directly from AD brains potently and consistently induces several AD-like phenotypes in normal adult rodents: it decreases dendritic spine density, inhibits LTP and facilitates LTD in hippocampus, and interferes with the memory of a learned behavior. We used non-denaturing gel filtration coupled with IP/WB and subsequent immunodepletion or neutralization with epitope-specific Aβ antibodies to ascribe the pathogenic effects to soluble Aβ oligomers, principally dimers.

Our findings support the emerging concept that the effects of Aβ in AD center initially on subtly altered synapse function. Neither Aβ monomers nor insoluble amyloid plaque cores significantly altered synaptic plasticity. This does not mean that insoluble amyloid plaques have no pathogenic role; their invariant accumulation may signify that they serve as relatively inert reservoirs of small bioactive oligomers, and they may disassemble more readily in the presence of lipids26. That plaque cores may release locally active Aβ species in vivo is suggested by a penumbra of synapse loss around cores in APP transgenic mice27.

Our examination of soluble dimers obtained from AD brain is partially consistent with findings using synthetic2 or cell-derived5,28 Aβ oligomers. However, there are unresolved differences regarding the precise biochemical nature of the synaptotoxic species found in these various systems. For example, we did not detect (Fig. 1 and Supp. Fig. 6) a soluble, SDS-stable dodecamer of Aβ in human cortical extracts such as the Aβ*56 species observed in brain extracts from certain APP transgenic mice29. Soluble Aβ complexes from AD cortex eluted in the void volume (>70 kDa) upon non-denaturing SEC, but these dissociated into dimers and monomers upon LDS-PAGE. Some AD and aged control CSF samples that contain soluble Aβ dimers were recently shown to impair LTP30, a finding consistent with our data. However, the invariant detection of dimers in the soluble fraction of AD cortex and their multiple synaptic effects strongly suggest that cortical dimers contribute directly to synapse dysfunction in AD patients, whereas any additional effects of CSF dimers in the minority of AD subjects who have them30 remain to be determined.

Mechanistically, we show that soluble Aβ dimers from AD cortex induce their effects by perturbing glutamatergic synaptic transmission. Although we find that mGluRs are required for the induction of LTD while NMDARs are needed for spine loss, these receptors are unlikely to be the sole effector targets of soluble Aβ oligomers. Aβ extracted from human brain can now serve as the most pathophysiologically relevant material for further pathway analysis and for preclinical validation of agents designed to neutralize Aβ aggregates. Our findings fulfill an essential requirement for establishing disease causation in AD.

METHODS

Human brain sample preparation

Brain specimens from deceased human subjects were collected at autopsy following informed consent from the next of kin under protocols approved by the Partners Human Research Committee at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the ERC/IRB committee at Beaumont Hospital in Dublin, Ireland. Each subject’s clinical and neuropathological diagnoses are provided in Supp. Tables 1. Frozen human temporal or frontal cortices containing white and grey matter were weighed. Freshly prepared, ice cold Tris-buffered saline (TBS) consisting of 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4 was added to the frozen cortex at 4:1 (TBS volume:brain wet wt) and homogenized with 25 strokes at a setting of 10 on a mechanical Dounce homogenizer. The homogenate was spun at 175,000 g in a TLA100.2 rotor on a Beckman TL 100. The supernate (called TBS extract) was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C, and the pellet was re-homogenized (4:1 v:w) in TBS + 1% Triton X-100 and spun as above. The resultant sup (called TBS-TX extract) was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C, and the pellet was re-homogenized in TBS + 5 M guanidine HCl, pH 8.0, and incubated on a Nutator for 12–16 hr at RT; the resultant sup (GuHCl extract) was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC)

One mL aliquots of the TBS-soluble AD brain extract were injected onto a Superdex 75 (10/30HR) column (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and eluted at a flow rate of 1 ml/min into 1 ml SEC fractions using 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 8.5. 750 μL were removed and stored at −80°C. The remaining 250 μL were lyophilized, reconstituted in 15 μL of 2X lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) sample buffer, heated at 70 °C for 5 min and electrophoresed on a 26-well 4–12% bis-tris gel using MES running buffer (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to 0.2 μm nitrocellulose and Western blotted (WB) for Aβ with 1 μg/ml 2G3 + 21F12 (gifts of Elan, plc) using the LiCor Odyssey Infrared Imaging System. SEC fractions containing higher order Aβ assemblies, LDS-stable Aβ dimers or Aβ monomers were pooled separately prior to lyophilizing into 450 μL aliquots.

Immunoprecipitation (IP)/WB analysis of Aβ in human brain extracts

We used an IP/WB protocol described previously6 to detect Aβ in the TBS, TBS-TX and GuHCl extracts. TBS extracts were IP’ed directly with either polyclonal Aβ antiserum R1282 (1:50) plus Protein A sepharose (PAS; Sigma) or monoclonal Aβ antibodies 3D6 (3 μg/mL) or 2G3 + 21F12 (each at 3 μg/mL) (gifts of Elan, plc) plus Protein G agarose (PGA; Roche) and PAS. GuHCl extracts were diluted 1:40 in DMEM and then IP’ed with R1282 (at 1:50) and PAS or else with 2 μg/mL 266+2G3+21F12 and PGA and PAS. Silver staining used the SilverQuest kit fast protocol (Invitrogen).

Hippocampal slice electrophysiology recording

The Harvard Medical School Standing Committee on Animals approved all experiments involving vertebrate animals used for electrophysiology and dendritic spine analysis. Standard field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSP) in the CA1 region of the mouse hippocampus were recorded. A unipolar stimulating electrode (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) was placed in the Schaffer collaterals of CA3 neurons to deliver test and conditioning stimuli. A borosilicate glass recording electrode filled with ACSF was positioned in stratum radiatum of CA1, 200–300 μm from the stimulating electrode. fEPSPs in CA1 were induced by 2 test stimuli at 0.05 Hz with an intensity that elicited a fEPSP amplitude 40~50% of maximum. Once a stable test response was attained for at least 30–60 min, experimental treatments were added to the 9.5 mL ACSF perfusate, and a baseline was recorded for an additional 20 min. These treatments included: 500 μL TBS extract, 500 μL TBS vehicle, 50 μM AP-V, 500 μM (R/S)-MCPG (Tocris) or 3 μM SIB1757. Lyophilized 450 μL aliquots of SEC fractions of GuHCl extracts described above were reconstituted in 500 μL ACSF and added to the slice perfusates. To induce LTP, we applied two consecutive trains (1 s) of stimuli at 100 Hz separated by 20 s, a protocol that induced LTP lasting approximately 1.5 hr in wt mice of this genetic background. To induce LTD, 300 pulses were delivered at 1 Hz. The field potentials were amplified 100x using an Axon Instruments 200B amplifer and digitized with Digidata 1322A. The data were sampled at 10 kHz and filtered at 2 kHz. Traces were obtained by pClamp 9.2 and analyzed using the Clampfit 9.2 program. LTP and LTD values reported throughout were measured at 60 min after the conditioning stimulus unless stated otherwise. Paired-pulse responses were monitored at 50 ms inter-stimulus intervals. The facilitation ratio was calculated as fEPSP2 slope/fEPSP1 slope. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test were used to determine statistical significance.

Passive Avoidance Conditioning

Passive avoidance training was performed as described previously18 (see Supplemental Methods). Wistar rats were administered AD TBS or AD TBS immunodepleted with R1282 at 0, 3, or 6 hr post-training. Recall of the passive avoidance conditioning was evaluated 24 and 48 hr post-training by recording the latency to enter the dark chamber, with a criterion time of 300 s. Data from the passive avoidance studies were analyzed by ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test.

Dendritic spine density analysis

The apical dendrites of pyramidal cells in organotypic hippocampal slices were prepared, treated, imaged and analyzed as described17 (see Supplemental Methods). Slices were treated for 10 d with AD TBS-SEC or Con TBS-SEC. Pharmacologic treatments were performed with 20 μM D-CPP or 500 μM (R/S)-MCPG in the presence or absence of AD TBS-SEC for 10 d.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Mass spectrometry was performed by the Taplin Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility (S. Gygi). We thank X. Sun and W. Qiu for performing ELISA. We thank members of the Selkoe laboratory for helpful comments. G.M.S. recognizes L. Gurumani for support and encouragement. This work was supported by National Institute on Aging grant AG R01 027443 (D.J.S., G.M.S., S.L., T.H.M., N.E.S.), Science Foundation Ireland grant 03/IN3/B403C (C.M.R., A.G-M.), and Wellcome Trust grant 067660 (D.M.W., I.S.).

References

- 1.Lorenzo A, Yankner BA. Beta-amyloid neurotoxicity requires fibril formation and is inhibited by congo red. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12243–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambert MP, et al. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6448–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mucke L, et al. High-level neuronal expression of abeta 1–42 in wild-type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4050–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan D, et al. A beta peptide vaccination prevents memory loss in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2000;408:982–5. doi: 10.1038/35050116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh DM, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–9. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh DM, Tseng BP, Rydel RE, Podlisny MB, Selkoe DJ. The oligomerization of amyloid beta-protein begins intracellularly in cells derived from human brain. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10831–9. doi: 10.1021/bi001048s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLean CA, et al. Soluble pool of Abeta amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:860–6. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199912)46:6<860::aid-ana8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuo YM, et al. Water-soluble Abeta (N-40, N-42) oligomers in normal and Alzheimer disease brains. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4077–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lue LF, et al. Soluble amyloid beta peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:853–62. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulz PE, Cook EP, Johnston D. Changes in paired-pulse facilitation suggest presynaptic involvement in long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5325–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05325.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kemp N, Bashir ZI. Long-term depression: a cascade of induction and expression mechanisms. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:339–65. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dudek SM, Bear MF. Homosynaptic long-term depression in area CA1 of hippocampus and effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4363–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulkey RM, Malenka RC. Mechanisms underlying induction of homosynaptic long-term depression in area CA1 of the hippocampus. Neuron. 1992;9:967–75. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90248-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tyszkiewicz JP, Yan Z. beta-Amyloid peptides impair PKC-dependent functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors in prefrontal cortical neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:3102–11. doi: 10.1152/jn.00939.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh H, et al. AMPAR removal underlies Abeta-induced synaptic depression and dendritic spine loss. Neuron. 2006;52:831–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lacor PN, et al. Abeta oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27:796–807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3501-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shankar GM, et al. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2866–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox GB, O’Connell AW, Murphy KJ, Regan CM. Memory consolidation induces a transient and time-dependent increase in the frequency of neural cell adhesion molecule polysialylated cells in the adult rat hippocampus. J Neurochem. 1995;65:2796–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65062796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Sullivan NC, et al. Temporal change in gene expression in the rat dentate gyrus following passive avoidance learning. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1085–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terry RD, et al. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:572–80. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tavazoie SF, Alvarez VA, Ridenour DA, Kwiatkowski DJ, Sabatini BL. Regulation of neuronal morphology and function by the tumor suppressors Tsc1 and Tsc2. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1727–34. doi: 10.1038/nn1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walsh DM, et al. Certain inhibitors of synthetic amyloid beta-peptide (Abeta) fibrillogenesis block oligomerization of natural Abeta and thereby rescue long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2455–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4391-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masters CL, et al. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:4245–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selkoe DJ, Abraham CR, Podlisny MB, Duffy LK. Isolation of low-molecular-weight proteins from amyloid plaque fibers in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 1986;46:1820–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb08501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roher AE, Palmer KC, Yurewicz EC, Ball MJ, Greenberg BD. Morphological and biochemical analyses of amyloid plaque core proteins purified from Alzheimer disease brain tissue. J Neurochem. 1993;61:1916–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb09834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martins IC, et al. Lipids revert inert Abeta amyloid fibrils to neurotoxic protofibrils that affect learning in mice. Embo J. 2008;27:224–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spires TL, et al. Dendritic spine abnormalities in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice demonstrated by gene transfer and intravital multiphoton microscopy. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7278–87. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1879-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cleary JP, et al. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-beta protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lesne S, et al. A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klyubin I, et al. Amyloid beta protein dimer-containing human CSF disrupts synaptic plasticity: prevention by systemic passive immunization. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4231–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5161-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.