Abstract

Schistosomiasis is a chronic parasitic disease affecting hundreds of millions of individuals worldwide. Current treatment depends on a single agent, praziquantel, raising concerns of emergence of resistant parasites. Here, we continue our explorations of an oxadiazole-2-oxide class of compounds we recently identified as inhibitors of thioredoxin glutathione reductase (TGR), a selenocysteine-containing flavoenzyme required by the parasite to maintain proper cellular redox balance. Through systematic evaluation of the core molecular structure of this chemotype we define the essential pharmacophore, establish a link between the nitric oxide donation and TGR inhibition, determine the selectivity for this chemotype versus related reductase enzymes and present evidence that these agents can be modified to possess appropriate drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic properties. The mechanistic link between exogenous NO donation and parasite injury is expanded and better defined. The results of these studies verify the utility of oxadiazole-2-oxides as novel inhibitors of TGR and as efficacious anti-schistosomal reagents.

Introduction

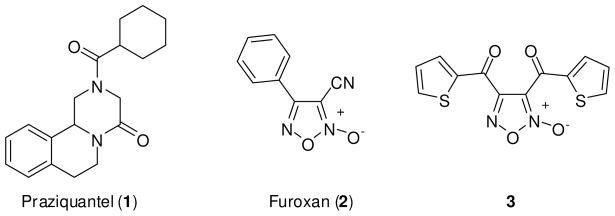

The chronic infectious disease schistosomiasis is a major neglected disease caused by trematode flatworms of the genus Schistosoma.1 Estimates suggest that a staggering 200+ million individuals suffer with this disease worldwide and the sub-Saharan Africa region experiences an estimated 280,000 deaths annually from schistosomiasis.2,3 Further, schistosomiasis causes altered immune responses to infections and vaccinations, increased perinatal transmission of HIV and increased susceptibility to and transmission of malaria, tuberculosis, hepatitis C and HIV.1,4 Schistosomiasis ranks among the most prominent neglected diseases due to the lack of interest from commercial pharmaceutical enterprises. It is rampant in impoverished populations due to inadequate sanitation and tainted water supplies and the burden of infection perpetuates these conditions. There is currently no vaccine for schistosomiasis and treatment of the disease is accomplished solely through the use of praziquantel (PZQ) (1) (Figure 1).5,6 The low cost of this agent (< $0.25 USD/dose) and its efficacy against the adult form of all schistosome species has lead to its widespread use (tens of millions of annual treatments).7 Because individuals do not acquire immunity after treatment and are rapidly reinfected, treatment must be administered annually or biannually. Although PZQ’s mechanism of action is not fully understood, research suggests that PZQ alters homeostasis of calcium resulting in a state of schistosomal paralysis that leads to exposure and increased susceptibility to the host immune system.8 A recent study has demonstrated that RNAi knockdown of the voltage-operated calcium channel β subunit ablated praziquantel efficacy in Dugesia japonica.9 The dependence and extensive use of PZQ has triggered concerns about the emergence of drug resistant parasites and evidence of drug resistance has been reported.10 Given the solitary and precarious reliance on PZQ for the control of such a widespread disease there is an urgent need to define novel targets and drugs for the treatment of schistosomiasis.

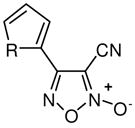

Figure 1.

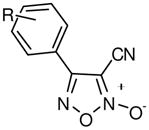

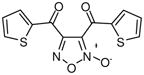

Structures of praziquantel (1), furoxan (2) and bis(thiophen-2-ylmethanone)-furoxan (3).

The schistosome lifecycle requires a snail intermediate host and a mammalian definitive host. Schistosome development in humans is complex and begins with cercarial penetration of human skin. Following entry into the circulatory system, parasites travel through the lungs and ultimately situate in the liver where they grow, differentiate, mate and then migrate to the urogenital system or mesenteric veins of the hepatoportal system to commence egg production. Given their wide tissue distribution and long life-span (up to 30 years), schistosomes have evolved robust defense mechanisms to mitigate oxidative damage and the host immune response. Most eukaryotes have multiple enzymatic processes to detoxify reactive oxygen species. In humans, these detoxification pathways depend upon two NADPH-dependent flavoenzymes that maintain glutathione and thioredoxin in their reduced state, aptly named glutathione reductase (GR) and thioredoxin reductase (TrxR).11,12 Biochemical, reverse genetic and genomic analysis of S. mansoni provide evidence that reduction of both glutathione and thioredoxin in schistosomes is dependent upon a single multifunctional selenocysteine-containing flavoenzyme designated thioredoxin glutathione reductase (TGR).13 A crystal structure of TGR (which contains a total of 13 cysteine residues and one selenocysteine) has been presented and offers a structural rationale for this dual activity.14 The dependence of schistosomes on a single, biochemically unique redox system is theorized to present an opportunity for drug development. Williams and coworkers revealed TGR as the putative molecular target of potassium antimonyl tartrate (a former treatment option for schistosomiasis) and that RNA interference targeting TGR resulted in rapid larval death (>90% in 4 days).15 Additionally, the disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug auranofin (a gold containing sugar conjugate) was found to be a potent inhibitor of TGR and killing of ex vivo parasites by this agent paralleled inhibition of TGR.13,15

These results present convincing evidence that TGR is an appropriate molecular target for pharmacological intervention and potential chemotherapy for schistosomiasis. We recently reported the development and validation of assays based upon the redox cascade of TGR in concert with peroxiredoxin2 (Prx2) using fluorescence intensity change associated with the consumption of NADPH16, and via a colorimetric approach utilizing reduction of Ellman’s reagent.17 A quantitative high-throughput screen18 of the NIH Molecular Libraries19 Small Molecule Repository was performed and numerous small molecule actives were identified.16 The chemotypes identified from this screen showed a range of potencies (including several in the low nanomolar range) and were validated as agents capable of inhibiting TGR in both the screening (Prx2-coupled NADPH consumption) and the follow-up (DTNB reduction) assay formats. Selected compounds were then advanced to investigations involving ex vivo worm cultures from each Schistosoma species that infects humans (S. mansoni, S. japonicum and S. haematobium). One agent, the well studied oxadiazole-2-oxide designated furoxan (2) (Figure 1), was capable of potent ex vivo worm killing at modest concentrations (10 μM) and, importantly, against all developmental stages of worm (transformed skin larva, lung-stage schistosomula, juvenile liver worms and adult worms).20 Based upon this encouraging result, furoxan (2) was entered into an in vivo evaluation in S. mansoni infected mice. Five consecutive daily intraperitoneal treatments of 10 mg/kg of 2 were performed in mice during the skin-stage infection (day 1–5), the juvenile/liver-stage infection (day 23–27) and the adult/egg-laying stage infection (day 37–41) and efficacy was quantified by adult worm burdens at day 49.20 Significant reduction of worm burdens and hepatomegaly and splenomegaly were noted for treatment groups at each parasite life stage. Both male and female worms were affected and a lower number of egg-induced granulomas were noted in comparison to control groups. Taken as a whole, the activity of furoxan (2) far exceeds the activity criteria set forth by the World Health Organization for candidate therapeutic development for schistosomiasis.21

The oxadiazole-2-oxide core is a well-studied structural motif explored by Ponzio in the early half of the 20th century and more recently expanded upon by Gasco and coworkers as a preeminent class of nitric oxide (NO) donating compounds.22,23 NO [the nitrogen-oxygen radical (NO·) not to be confused with the nitroxyl anion (NO−)]24,25 is a well studied physiological signaling agent best known for its ability to relax smooth muscle tissue resulting in vasodilatation and increased blood flow.26 NO has been implicated in numerous biochemical processes and, importantly, elevated and sustained levels of NO can be toxic. Gasco first reported the thiol mediated release of NO from furoxan (2) and the resulting vasodilatory properties in 1994.27 Since that time, the core oxadiazole-2-oxide moiety has been conjugated to numerous bioactive compounds in attempts to make chimeric small molecules with dual activities including NO-donating β–adrenoceptor agonists,28 NO-donating aspirin conjugates29 and NO-donating proton pump inhibitors.30

There is ample direct and indirect evidence that NO can act as an antischistosomal and, more broadly, antiparasitic molecule.31–33 NO produced by human white cells has been shown to kill larval schistosome parasites.34 NO produced through inducible NO synthase activation is a core component of the immune response and direct evidence of NO being a primary aspect of host defense against Echinococcus granulosus and Trypanosoma congolense has been presented.35,36 Winberg et al. recently demonstrated that NO production diminished Leishmania donovani promastigotes ability to inhibit periphagosomal F-actin breakdown, allowing normal phagosomal maturation and parasite killing.37 Beyond innate activation of the NO synthase, exogenous NO from small molecule NO donors has shown promise in several arenas. A topical formulation of S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) was reported as an effective treatment option for the control of cutaneous leishmaniasis.38 A class of bicyclic nitroimidazoles was recently reported as a deazaflavin-dependent nitroreductase prodrug that releases oxidized nitrogen molecules that are converted to NO and are capable of anaerobic killing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.39 Further, the mainstays of Chagas disease chemotherapy are benznidazole and nifurtimox (agents with heteroaromatic nitro moieties). 40 Recently, Wilkinson et al demonstrated that these prodrugs are activated in T. cruzi by a NADPH-dependent type I nitroreductase.41 It is entirely plausible that this process results in the generation of NO.

Given the relationship between NO and antiparasitic activity and the prior research on furoxan (2) as a NO donor compound, it was sensible to assess the NO generating capacity of these agents. In the presence of a free thiol (cysteine) it was determined that furoxan (2) was an effective NO donor compound (as judged by ABTS42 oxidation).20 Analysis of NO release by 2 in the presence of TGR was found to be dependent on the presence of NADPH. Interestingly, several oxadiazole-2-oxide analogues with potent TGR inhibition, for instance bis(thiophen-2-ylmethanone)-furoxan (3) (TGR IC50 of ~ 60 nM), were capable of NO generation in the presence of cysteine but not in the presence of TGR/NADPH. This ultimately proved significant as only oxadiazole-2-oxides that generated NO in the presence of TGR/NADPH were capable of ex vivo worm killing.20 The association between NO release and worm killing was further evidenced by the partial mitigation of furoxan (2) induced parasite death by the presence of a NO scavenger molecule C-PTIO.20,43 Clearly, there is a relationship between NO release and the activity of this chemotype versus schistosomiasis. Here, we define the molecular pharmacophore of these agents, optimize compounds in terms of NO generation and potency versus TGR and worm killing efficacy, provide mechanistic evidence for TGR inhibition and parasite death and discuss the selectivity and bioavailability of chosen analogues.

Results and Discussion

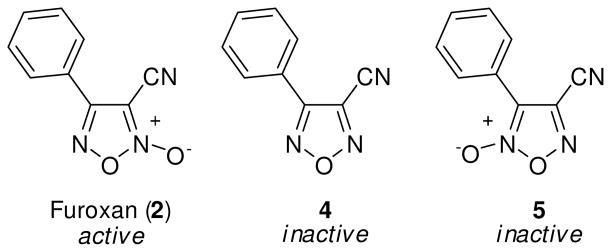

Prior to any optimization effort to improve this chemotype’s ability to inhibit TGR and effectively act as an anti-schistosomal agent we needed to establish a mechanistic link between NO donation and TGR inhibition. As such, our first considerations involved the synthetic deconstruction of the molecular structure of 2. Various synthetic pathways for oxadiazole-2-oxides have been reviewed by Gasco and coworkers.22,23 Additionally, Maloney and coworkers have recently described the synthetic elaboration of the small molecule oxadiazole-2-oxides described in this report.44 From the outset, an examination of the N-oxide moiety was of paramount importance. To better understand this key structural feature of the compound we examined analogues that lack (derivative 4) and regiochemically transpose (derivative 5) the N-oxide (Figure 2). As opposed to furoxan (2), both 4 and 5 gave no appreciable NO release with TGR nor was either analogue active versus TGR or an effective ex vivo worm killing agent. Our next consideration was to determine the importance of the nitrile functionality. To explore the structure activity relationships (SAR) of this moiety, we considered analogues along the scale of oxidation states (i.e. alkyl to acyl). Several analogues were accessible intermediates of synthesis of 2 (including derivatives 7 and 8) while others required a separate synthetic effort (derivatives 6, 9 and 10).44 The SAR of these analogues provided the first indication of the complexity surrounding the relationship between NO release, TGR inhibition and worm killing (described through visual examination of cultured worms treated with 10 μM of compound over a 72 hour time-course). The methyl analogue 6 was inactive as a NO donor and a TGR inhibitor and was essentially inactive in the worm killing evaluation (Table 1). The hydroxyl analogue 7 regained the ability to inhibit TGR (IC50 of 11.3 μM) but was only a weak NO donor and possessed minimal ability to kill ex vivo worms. The aldehyde 8 and carboxylic acid 9 were noted to be potent inhibitors of TGR (IC50 of 0.11 μM and 0.63 μM, respectively). Surprisingly, these analogues possessed only modest NO donating abilities and were ineffective worm killing agents. Interestingly, the aldehyde moiety in 8 would be capable of entering into electrophilic/nucleophilic reactive mechanisms with cysteine (and selenocysteine) residues in a similar fashion to the nitrile of 2. The only analogue in this SAR series that retained both TGR inhibition and worm killing ability was the amide 10, albeit at slightly lower potency and efficacy. With these results in place it seems reasonable to consider the 3-cyano-1,2,5-oxadiazole-2-oxide core as the pharmacophore for these agents in terms of TGR inhibition, NO donating potential and worm killing efficacy.

Figure 2.

Structure activity relationships of the N-oxide moiety.

Table 1.

SAR of Nitrile Substitutions

| Analogue | R′ | TGRa | TGRa | Ex Vivo Parasite Killingb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM) | Max Resp. (% inh) | 2 hr | 4 hr | 8 hr | 16 hr | 24 hr | 48 hr | 72 hr | |||

2,6,10 |

2 | CN | 6.3 | − 102 | n.e. | curling | 25%D | 40%D | 100%D | 100%D | 100%D |

| 6 | CH3 | > 50 | − 15 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | sluggish | 5%D | |

| 7 | CH2OH | 11.2 | − 100 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | sluggish | sluggish | 10%D | |

| 8 | CHO | 0.11 | − 105 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | sluggish | 3%D | 5%D | |

| 9 | COOH | 0.63 | − 95 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | |

| 10 | CONH2 | 17.8 | − 75 | n.e. | n.e. | 12%D | 27%D | 60%D | 100%D | 100%D | |

data represents the results from three separate experiments.

Data collected by visual examination of worm movement and shape. n.e. (no effect) = all worms are scored as active in culture with typical appearance; curling = worms are seen to curl rather than stretch and contract; sluggish = worm movement is significantly reduced; % D = % of worms dead as judged by lack of movement.

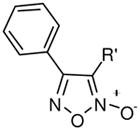

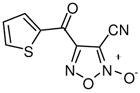

With a verified and consistent definition of the pharmacophore, we next turned to a systematic evaluation of the phenyl ring through the appraisal of standard substitutions (including methyl, methoxy, halo, trifluoromethyl, nitro, hydroxyl and phenyl) and replacements (including heterocycles furan and thiophene). The results are detailed in Table 2 and show clear evidence that the majority of analogues preserving the core 3-cyano-1,2,5-oxadiazole-2-oxide moiety (11–18, 20–29) retain TGR inhibition and worm killing capacity (11–18, 20–28 were additionally noted to be capable NO donating molecules). The SAR trends revealed that electron-withdrawing substitutions (halo, trifluoromethyl and nitro) provided slight potency enhancements and the meta-position seemed favored [in general, substitutions at the ortho position were not synthetically viable (compound 21 was the lone exception)]. Importantly, there was general agreement between TGR inhibition and worm killing efficacy. For instance, analogues 12–17 possessed TGR IC50 between 2 μM and 4 μM and were at least as efficacious as furoxan (2) in terms of worm killing. Conversely, several analogues with TGR IC50 values between 9 μM and 18 μM and were generally less active against worms in culture. From this phenyl ring scan there were several intriguing lessons. The unique difference between substitutions at the meta and para positions was further highlighted by the hydroxyl analogues 19 and 27. Analogue 19 possessed good TGR inhibition but was inactive as a worm killing agent, while 27 was among the least potent analogues for TGR inhibition yet retained respectable activity versus worms. Replacement of the phenyl ring with heterocycles furan and thiophene (analogues 28 and 29, respectively) resulted in derivatives with slightly improved potencies for TGR inhibition, good NO release profiles and good worm killing efficacy. Another important exploration involved the substitution of the 4 position of the oxadiazole ring with a substituted carbonyl. Data from our initial studies on compounds with acyl substitutions on the oxadiazole ring system (such as in 3) and analogues presented here (such as aldehyde 8) demonstrate that such functionality confers significant potency enhancements in terms of TGR inhibition. These analogues, however, are devoid of the key 3-cyano-1,2,5-oxadiazole-2-oxide pharmacophore and were markedly less active versus cultured worms. We were, therefore, eager to examine an analogue that possessed both the nitrile moiety and a ketone moiety. As such, we synthesized a novel oxadiazole-2-oxide (analogue 30) that satisfies these requirements (it should be noted that 30 required an entirely novel synthetic route spanning a total of 9 transformations44). The inhibition of TGR by 30 was in alignment with our previous results for 3 and 8 (potency of 63 nM). Unfortunately, like the aforementioned analogues, 30 was devoid of activity versus worms in culture.

Table 2.

SAR of Phenyl Ring Substitutions and Substitutions on the 3 and 4 Carbons of the Oxadiazole Ring.

| Analogue | R | TGRa | TGRa | Ex Vivo Parasite Killingb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM) | Max Resp. (% inh) | 2 hr | 4 hr | 8 hr | 16 hr | 24 hr | 48 hr | 72 hr | |||

2,11–27 |

2 | NA | 6.3 | − 102 | n.e. | curling | 25%D | 40%D | 100%D | 100%D | 100%D |

| 3 | NA | 0.04 | − 101 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | |

| 11 | 3-NO2 | 2.2 | − 107 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | sluggish | 10%D | 15%D | 21%D | |

| 12 | 3-CF3 | 2.5 | − 102 | n.e. | n.e. | 7%D | 25%D | 54%D | 100%D | 100%D | |

| 13 | 3-Br, 4-F | 2.8 | − 102 | n.e. | n.e. | curling | 5%D | 50%D | 75%D | 100%D | |

3 |

14 | 3-Br | 2.8 | − 100 | n.e. | n.e. | 20%D | 39%D | 100%D | 100%D | 100%D |

| 15 | 3-Cl | 3.5 | − 101 | n.e. | sluggish | 15%D | 20%D | 64%D | 80%D | 100%D | |

| 16 | 4-Br | 3.5 | − 99 | n.e. | sluggish | 39%D | 60%D | 100%D | 100%D | 100%D | |

| 17 | 4-Cl | 4.0 | − 99 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | sluggish | 42%D | 60%D | 100%D | |

| 18 | 4-CF3 | 7.1 | − 103 | n.e. | n.e. | 12%D | 20%D | 64%D | 80%D | 100%D | |

28, 29 |

19 | 3-OH | 7.1 | − 96 | n.e. | n.e. | ND | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. |

| 20 | 4-F | 7.9 | − 103 | n.e. | n.e. | 5%D | 15%D | 72%D | 100%D | 100%D | |

| 21 | 2-OMe | 7.9 | − 96 | n.e. | n.e. | 4%D | 11%D | 40%D | 50%D | 60%D | |

| 22 | 3,4,5-OMe | 8.9 | − 102 | n.e. | n.e. | 7%D | sluggish | 40%D | 70%D | 75%D | |

| 23 | 3-OMe | 8.9 | − 102 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | 7%D | 12%D | 20%D | |

| 24 | 4-OMe | 10.0 | − 97 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | 10%D | 29%D | 60%D | 100%D | |

30 |

25 | 4-Me | 11.2 | − 98 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | 15%D | 50%D | 55%D | 70%D |

| 26 | 4-Ph | 15.8 | − 71 | n.e. | n.e. | sluggish | sluggish | 20%D | 40%D | 45%D | |

| 27 | 4-OH | 17.9 | − 64 | n.e. | n.e. | sluggish | 15%D | 40%D | 60%D | 100%D | |

| 28 | O | 2.8 | − 95 | n.e. | n.e. | 10%D | 40%D | 70%D | 100%D | 100%D | |

| 29 | S | 3.5 | − 94 | n.e. | n.e. | ND | 25%D | 25%D | 100%D | 100%D | |

| 30 | NA | 0.063 | − 102 | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | n.e. | |

data represents the results from three separate experiments.

Data collected by visual examination of worm movement and shape. n.e. (no effect) = all worms are scored as active in culture with typical appearance; curling = worms are seen to curl rather than stretch and contract; sluggish = worm movement is significantly reduced; % D = % of worms dead as judged by lack of movement. ND = not determined.

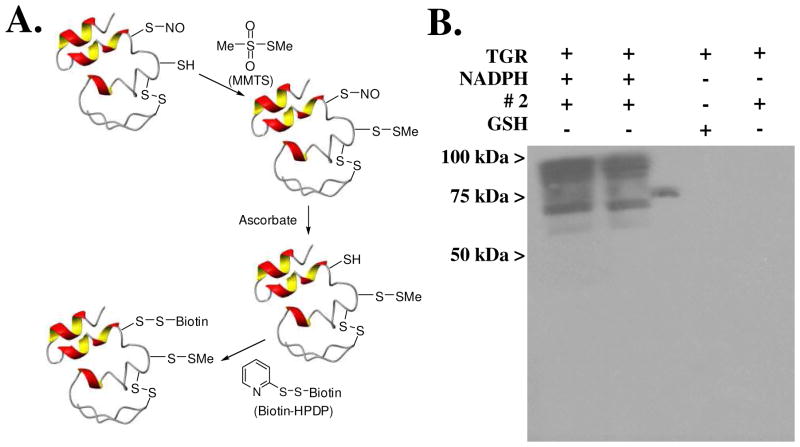

The results of these studies provide solid evidence that inhibition of TGR by oxadiazole-2-oxides must be coupled with the ability of these small molecules to act as a NO donating compound in order to effect parasite death. A major question, however, concerns the role that molecular NO plays in TGR inhibition and ultimately worm killing. That NO can modify protein structure and function by the act of S-nitrosylation was first shown in the early 1990s.45,46 Becker et al subsequently showed that human GR can be inhibited by NO donating compounds and an active site cysteine residue is oxidized as a result.47 Additionally, S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues on coxsackieviral protease 2A, 3C and rhinovirus 3C is recognized to affect coxsackievirus and rhinovirus, respectively.48–50 Given the aforementioned precedence and the intriguing presence of 13 cysteine residues and one selenocysteine in TGR, we set out to examine the potential role of S-nitrosylation (or Se-nitrosylation) during TGR inhibition by 2. To explore this possibility, we took advantage of the well known biotin-switch assay introduced by Snyder and coworkers.51,52 A cartoon representation of the principal experiment is outlined in Figure 3A. Here, recombinant TGR was incubated with and without NADPH, furoxan (2) and glutathione (GSH). After incubation the reactants were removed from TGR on a spin column and by acetone precipitation of TGR. All cysteine (or selenocysteine) residues that remain in their reduced sulfhydryl form are then capped by methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS). TGR was then treated with reduced ascorbate to return all S-nitrosylated cysteines (or Se-nitrosylated selenocysteines) to their reduced form, followed by reaction with the thiol-modifying reagent biotin-HPDP to allow visualization of labeled protein. After purification of the protein on a spin column and acetone precipitation it was analyzed by native-Western blotting using a HRP-streptavidin conjugate to identify biotinylated proteins (Figure 3B). The results shown clearly indicate that recombinant TGR is S-nitrosylated by 2 and that the nitrosylation depends on the protein activity (i.e. requires NADPH) (Figure 3B). The experiment was performed with pure, recombinant TGR and analyzed on a native gel; additional bands are likely the result of both monomeric and dimeric proteins and multiple S-nitrosylation events. No TGR labeling was observed when incubation was with GSH or in the absence of NADPH.

Figure 3.

A. Cartoon representation of the Biotin-switch assay (see ref 49 and 50). B. Detection of S-nitrosylation in recombinant S. mansoni TGR after reaction with furoxan (2) 20 μM (lane 1) and 10 μM (lane 2) ± NADPH. The molecular weight of unmodified recombinant TGR is 64,880 Daltons.

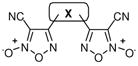

The results from this experiment strongly suggest that NO plays a significant role in TGR inhibition and likely in parasite killing. Based upon this knowledge, our thoughts regarding the optimization of the oxadiazole-2-oxide chemotype focused on ways to optimize the NO donating qualities of individual compounds. Our previous attempts to optimize the compound through a standard phenyl ring scan (Table 2) provided evidence that the electron-withdrawing nature of the substituent at the 4-position of the oxadiazole ring was beneficial. While this makes mechanistic sense, even the most electron deficient phenyl rings provided only modest potency enhancements in terms of TGR inhibition and no discernable benefit in worm killing. Our next consideration was to explore analogues capable of delivering two equivalents of NO. To this end, we synthesized and evaluated several bis-oxadiazole-2-oxide derivatives linked through substituted phenyl rings and heterocycles. The results for these agents are shown in Table 3 and demonstrate the validity of the theory. All bis-oxadiazole-2-oxide analogues were capable of TGR inhibition at potencies exceeding furoxan (2) and worm killing profiles also demonstrated similarity to furoxan (2) and in some cases modest improvements (analogues 33, 34, and 35 were examined in a separate experiment). Worm death will not occur until the GSH/GSSG ratio reaches a critical point and the overall worm redox balance is unrecoverable, making it difficult to derive correlations between worm killing and TGR inhibition below a certain level.

Table 3.

SAR of Bis Oxadiazole-2-Oxides

| Analogue | X | TGRa | TGRa | Ex Vivo Parasite Killingb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM) | Max Resp. (% inh) | 2 hr | 4 hr | 8 hr | 16 hr | 24 hr | 48 hr | |||

31–35 |

2 | NA | 6.3 | − 102 | n.e. | curling | 25%D | 40%D | 100%D | 100%D |

| 31 | 1,3-Phenyl | 3.5 | − 95 | n.e. | curling | 45%D | 60%D | 100%D | 100%D | |

| 32 | 1,4-Phenyl | 1.0 | − 98 | n.e. | n.e. | ND | 55%D | 82%D | 100%D | |

| 33 | 5-Fluoro-1,3 Phenyl | 0.48 | − 95 | n.e. | n.e. | ND | 55%D | 78%D | 100%D | |

| 34 | 2,5-Thiophene | 0.40 | − 102 | n.e. | 8%D | ND | 62%D | 82%D | 100%D | |

| 35 | 2,4-Thiophene | 0.35 | − 92 | n.e. | 15%D | ND | 55%D | 91%D | 100%D | |

data represents the results from three separate experiments.

Data collected by visual examination of worm movement and shape. n.e. (no effect) = all worms are scored as active in culture with typical appearance; curling = worms are seen to curl rather than stretch and contract; sluggish = worm movement is significantly reduced; % D = % of worms dead as judged by lack of movement. ND = not determined.

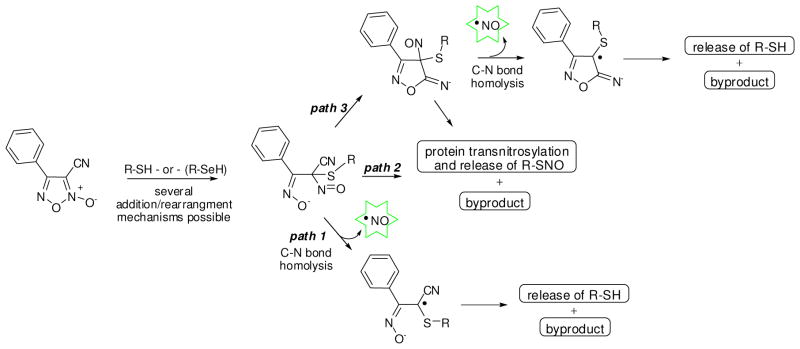

With a growing understanding of this chemotype’s potential and the advancements of several analogues with improved properties, it was important to consider the mechanism of NO donation from oxadiazole-2-oxides. A mechanistic rationale for NO donation that is initiated through nucleophilic attack (presumably by the sulfhydryl moiety of a cysteine residue or by selenocysteine) at either the 3 or 4 position of the oxadiazole ring and subsequent rearrangement of the heterocycle in a manner that allows release of the nitroxyl anion (NO−) has been presented.22,23 An enzymatic oxidation is posited to transform this agent to NO (NO·). It is important to note that the nitroxyl anion (NO−) exists as a triplet that reacts very rapidly with triplet dioxygen to form peroxynitrite ion. Thus, it is unlikely that the transformation from NO− to NO· occurs via oxidation by molecular oxygen. Additionally, the previously reported mechanism27 suggests a permanent ligation between the attacking nucleophile and the rearranged carbon scaffold of furoxan (2). While this mechanism is plausible, there are several aspects that are not consistent with the data from our study. Foremost, this mechanism does not account for the release of NO (rather than NO−) during a reaction with cysteine (i.e. in an environment lacking an enzyme capable of oxidizing NO− to NO·). A second issue is the stoichiometry of the processes. Our previous data suggests that TGR acts catalytically on furoxan (2) in terms of NO release. A 10 μM concentration of 2 in the presence of 15 nM of TGR and NADPH resulted in the generation of ~ 15 mole % of NO relative to 2; i.e. ~ 1500 nM NO from only 15 nM of TGR -or- 100 equivalents of NO per enzyme equivalent. Obviously TGR has the ability to attack furoxan (2), effect molecular rearrangement and release of NO, and subsequently release from the heterocycle scaffold in such a manner that it retains the ability to re-enter the cycle with another molecule of furoxan (2). Presumably, this cycle continues until a critical concentration of NO is present and the enzyme is sufficiently S-nitrosylated as to lose activity. Given these inconsistencies, we sought evidence of alternate mechanisms.

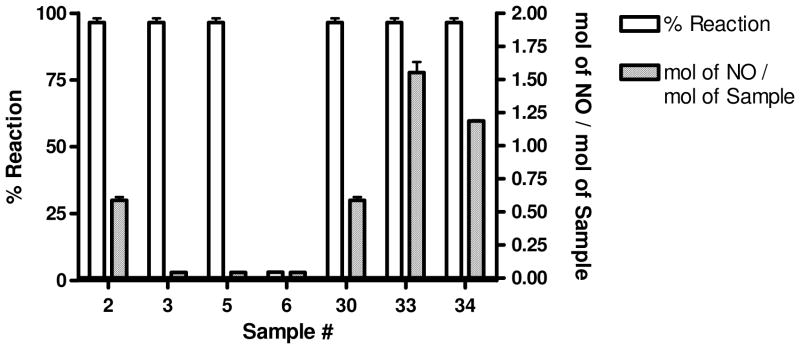

Recently, Chakrapani et al presented experimental evidence of NO donation from C-nitroso compounds through a first-order homolytic C-N bond scission event.52 Interestingly, this mechanism required a geminal nitrile moiety to allow homolysis of the C-N bond. Moreover, the reactivity between nitrile groups and free thiols is well established and explored.54 To further explore the mechanistic release of NO, we examined selected analogues ability to donate NO as judged by the aforementioned ABTS method (see the supporting information section for these data). The results confirmed that analogues must be capable of generating NO in the presence of TGR and NADPH to be effective worm killing agents. The ABTS method provides a measure of the oxidation products of NO rather than NO itself. To more exactly quantify the release of NO, we examined the release of NO quantitatively through a well known chemiluminescent assay that relies upon the reaction between NO and ozone to produce an activated NO2 species that produces an intense chemiluminescence emission.54 Additionally, selected analogues were characterized for their ability to react with free cysteine (as judged by consumption of starting material detected across an HPLC gradient). For these experiments, we selected a number of compounds with specific SAR in terms of TGR inhibition and worm killing ability (Figure 4). Furoxan (2) was noted to react fully with cysteine and produce approximately 0.6 equivalents of NO per equivalent of 2. Gratifyingly, bis-oxadiazole-2-oxide analogues 33 and 34 were both cysteine reactive and produced more NO equivalents relative to furoxan (2) (1.55 molar equivalents for 33 and 1.19 molar equivalents for 34). Analogue 6, with the replacement of the nitrile with a methyl group, was not capable of reacting with cysteine nor was 6 capable of NO donation. Most interestingly, derivatives 3 (with the bis-thiophene ketone moiety) and 5 (with a transposed N-O moiety, but retaining the nitrile) did react with cysteine, but did not generate NO. An additionally interesting result was that compound 30 (with both thiophene ketone and nitrile moieties) reacted with cysteine and was capable of releasing NO. From this result, the failure of 30 to produce worm death is unexplained.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of furoxan (2) and selected analogues for reactivity with free cysteine as judged by consumption of reagent and the molar ratio of NO release per stoichiometric equivalent of reagent.

Mechanistically, it is not possible to identify the location of the initial nucleophilic attack, but the ultimate result is addition into the oxadiazole ring system alpha to the nitrile (Figure 5). The ring system would likely open resulting in a quaternary alkyl-thio-nitroso-nitrile species that is highly similar to the C-nitroso compounds shown by Chakrapani et al to be capable of homolytic C-N bond cleavage and release of NO (path 1). Alternatively, this intermediate could undergo transnitrosylation and release of R-SNO and a byproduct of the original oxadiazole-2-oxide heterocycle (path 2). It is further possible that this intermediate could rearrange to form an isoxazol-5(4H)-imine type intermediate prior to homolytic C-N bond cleavage and release of NO (path 3). A second mechanistic issue is the ultimate release of the attacking nucleophile from the core oxadiazole scaffold. While plausible mechanisms can be envisioned for this de-ligation event, there is currently no experimental evidence for how it would proceed. Interestingly, we tested this point through the synthesis of a biotinylated version of furoxan (2) (conjugated through an ether linkage at the 4-position of the phenyl ring) and subsequent treatment of this analogue with recombinant TGR and NADPH. Gel analysis of the resulting mixture provided evidence that TGR was not cross-linked to biotin, further suggesting that TGR reacts with oxadiazole-2-oxides in a catalytic rather than terminally reactive mechanism (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Schematic description of potential mechanisms for NO release by oxadiazole-2-oxides via reaction with reactive thiols (or with selenol).

These insights into the interaction of oxadiazole-2-oxides with TGR suggest that the preeminent mechanistic event is the nucleophilic attack by either cysteine or selenocysteine residues on TGR. Selenium has a unique role in biology and the biosynthesis of selenocysteine residues and, ultimately, selenoproteins has been the subject of numerous reviews.56 To date, 25 human proteins have been characterized that contain selenocysteine residues and each retain a specified cellular function (over 300 selenoprotein families have been found in nature).57 A minimalist view of atomic sulfur and selenium highlight several divergent properties that translate into important biochemical differences for selenocysteine and cysteine residues. Primary among these variations are the relative pKa values for both amino acids (8.5 for cysteine versus 5.2 for selenocysteine) and the stronger nucleophilicity of selenocysteine.58–60 Evolutionary analyses clearly suggest that selenocysteine supports unique roles in selenoproteins that can not easily be maintained by cysteine.61 The strikingly low pKa of selenocysteine results in full anionic character for this residue at physiological pH. In several instances, the divergent activities of selenocysteine and cysteine residues have been exploited. For instance, Filipovska and coworkers recently reported the rational design of gold (I) containing N-heterocyclic carbene complexes that target the selenocysteine-containing TrxR and are selectively toxic to cancer cells.62 Arnér and coworkers have found that forms of selenium compromised thioredoxin reductase-derived apoptotic proteins (SecTRAPs) may have prooxidant toxic properties in addition to a loss of thioredoxin reducing capacity.63

While there is not yet any direct evidence, it seems reasonable to assume that the enhanced nucleophilicity associated with the selenocysteine residues (including the one found in TGR) makes this moiety a likely candidate for the initial attack on furoxan (2) and other oxadiazole-2-oxides. As such, it was important to explore the selectivity of this chemotype with regards to its ability to act as a general electrophile for other selenocysteine containing enzymes. Additionally, it was essential to consider if these compounds inhibit related host enzymes, most significantly GR and TrxR. To resolve both questions we assayed several analogues versus human GR and rat TrxR (rat TrxR is a selenoprotein64 while human GR is not). We found that furoxan (2) does not inhibit recombinant human GR (IC50 > 50 μM) or recombinant rat TrxR (IC50 > 400 μM) (Table 4). Of interest was the discovery that three of the agents tested (the aldehyde 8 and phenyl ring analogues 15 and 18) were found to inhibit both hGR and rat TrxR, albeit with reduced affinity. The aldehyde derivative 8 may yield insight into the mechanism of these agents and the discovery of inhibitors of both hGR and rat TrxR is an important finding on its own accord. More important for this study, however, is the fact that several of the anti-schisotosomal analogues were found not to be inhibitors of the TGR-related mammalian host enzymes. Taken as a whole, the data presented here provides strong evidence supporting the selective action by oxadiazole-2-oxides against schistosomes and suggests that the interaction of this chemotype with TGR is dependent upon both binding affinity and appropriately aligned reactivities.

Table 4.

Comparative inhibition of selected analogues versus TGR, human GR and rat TrxR.

| Analogue | TGRa | hGRb | rTrxRb |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μM) | IC50 (μM) | IC50 (μM) | |

| 2 | 6.3 | > 50 | > 400 |

| 6 | > 50 | > 50 | > 400 |

| 7 | 11.2 | > 50 | > 400 |

| 8 | 0.11 | 35.2 | < 12.5 |

| 9 | 0.63 | > 50 | > 400 |

| 10 | 17.8 | > 50 | > 400 |

| 11 | 2.2 | > 50 | ca. 150 |

| 12 | 2.5 | > 50 | ca. 250 |

| 13 | 2.8 | > 50 | ca. 250 |

| 14 | 2.8 | > 50 | ca. 150 |

| 15 | 3.5 | 35.7 | < 12.5 |

| 16 | 3.5 | > 50 | ca. 250 |

| 17 | 4.0 | > 50 | > 400 |

| 18 | 7.1 | 45.3 | < 12.5 |

| 20 | 7.9 | > 50 | ca. 300 |

| 22 | 8.9 | > 50 | ca. 150 |

| 23 | 8.9 | > 50 | > 400 |

| 24 | 10.0 | > 50 | > 400 |

| 25 | 11.2 | > 50 | > 400 |

| 27 | 17.9 | > 50 | > 400 |

| 28 | 2.8 | > 50 | ca. 350 |

| 31 | 3.5 | > 50 | ca. 150 |

data represents the results from three separate experiments.

Methods for determining inhibitory potential versus hGR and rTrxR are presented in the supporting information section.

We were further interested in determining if the oxadiazole-2-oxide scaffold has suitable properties for oral bioavailability. Since therapies for schistosomiasis are intended to be single dose agents (as opposed to chronic treatments), we were initially and primarily interested in determining selected analogues’ potential for passive membrane permeation and stability in liver microsomes. Profiles of these agents binding to the human Ether-à-go-go Related Gene (hERG) potassium channel and inhibition of selected members of the cytochrome P450 class of enzymes were also of interest. Our own investigations of these agents suggested highly variable solubilities in water. We were interested to go beyond conjectural evaluations of this property (i.e. HPLC retention times) and establish more reliable data for selected analogues. Consequently, solubility measurements (in both μM and μg/mL) and LogD determinations were ascertained. The results of these profiles are shown in Table 5. Several compounds had only modest water solubility including furoxan (2), 16, 31, 32, and 34. Analogues containing the thiophene ring were noted as having better solubility profiles, including 29 and 35. Interestingly, the addition of a single fluorine moiety to the bis-oxadiazole-2-oxide analogue 31 resulted in an impressive gain in solubility (see derivative 33).

Table 5.

Solubility and Selected ADME Properties for Chosen Analogues

| Analogue | Solubilitya (μM) |

Solubilitya (μg/mL) |

LogDb | Caco-2 Permeabilityc mean A->B |

Caco-2 Permeabilityc mean B->A |

Microsomal stabilityd |

hERG FastPatche |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 30.1 | 5.6 | 2.42 | 1.0 | 0 | 8/63 | 13.2% |

| 16 | 18.6 | 5.0 | 3.1 | 7.9 | 4.8 | 10/67 | 5.5% |

| 29 | 240.4 | 46.4 | 2.54 | 8.4 | 9.0 | 1/64 | 3.4% |

| 31 | 5.0 | 1.5 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | 7.8% |

| 32 | 3.7 | 1.1 | ND* | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 33 | 89.1 | 28.0 | 2.91 | 7.9 | 2.7 | 20/51 | 29.4% |

| 34 | 11.5 | 3.5 | 2.92 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 3/56 | 83.9% |

| 35 | 122.2 | 36.9 | 2.92 | 9.4 | 3.4 | 12/52 | 57.2% |

kinetic solubility analysis was performed by Analiza Inc. and are based upon quantitative nitrogen detection as described (www.analiza.com). The data represents results from three separate experiments with an average intraassay %CV of 4.5%.

LogD analysis was performed by Analiza Inc. and are based upon octanol/buffer partitioning and quantitative nitrogen detection of sample content as described (www.analiza.com). The data represents results from three separate experiments and is corrected to calibration standards and adjusted to account for fixed amounts of DMSO.

Caco-2 permeability analysis was performed by Apredica Inc. and are based upon monolayer Caco-2 cells applied to collagen-coated BioCoat Cell Environment at 24,500 cells per well as described (www.apredica.com). Data are expressed in Papp (apparent permeability) in 10−6 cm s−1. Atenolol was used as a low permeability control (mean A->B = 1.2 and mean B->A = 1.2) and propanolol was used as a high permeability control (mean A->B = 20.3 and mean B->A = 17.4).

Microsomal stability analysis was performed by Apredica Inc. and are based upon duplicate incubations of test reagent with liver microsomes (human and rat; only human data is shown) over 60 minutes at 37 °C as described (www.apredica.com). LC/MS/MS is utilized to quantitate remaining test reagent and the data is reported as % remaining. Analysis in the absence and presence of NADPH was performed to assess NADPH free degradation. Data is listed as NADPH (+) degradation/NADPH (−) degradation.

hERG FastPatch analysis was performed by Apredica Inc. using an automated patch clamp electrophysiological procedure using HEK293 cells stably transfected with hERG cDNA as described (www.apredica.com). Test reagents were applied at standard concentrations (10 μM) and data is recorded as mean % inhibition from three separate experiments.

Beyond solubility profiling, several analogues were found to have modest ability to permeate artificial Caco-2 cell monolayers [apical to basolateral (A→B) permeability was typically greater than basolateral to apical (B→A)]. Furoxan (2) was not found to pass through Caco-2 cells, however, several analogues (including 16, 29, 33 and 35) were noted to possess adequate Caco-2 profiles. While these data does not guarantee successful realization of these analogues as orally available agents, it does dispel concerns that the oxadiazole-2-oxide scaffolds are incapable of passive membrane permeation. Analysis of these analogues in liver microsomes (over 1 hour in the presence/absence of NADPH) suggests that these compounds are only moderately stable and may possess short half-lives in intact animal models. However, the variable data (for instance compound 29 versus 33) suggests that more robust analogues may be found through additional modification. Further, the hERG and Cyp profiles for these agents were generally reasonable. Taken as a whole, these data suggests that properly substituted oxadiazole-2-oxides may possess efficacy and ADMET properties adequate for clinical application.

Conclusion

Given the widespread morbidity and mortality associated with schistosomiasis and the precarious reliance on PZQ as the exclusive anti-schistosomal agent, development of new treatments for the disease is critical. Here, we present data from our continued evaluation of the oxadiazole-2-oxide class of reagents as inhibitors of the multifunctional selenocysteine-containing flavoenzyme TGR. Through chemical modification of the lead agent [furoxan (2)] we have defined the pharmacophore as the 3-cyano-1,2,5-oxadiazole-2-oxide moiety and established SARs surrounding the phenyl ring of the core structure. Through use of the biotin-switch assay, we have shown that incubation of TGR with furoxan (2) leads to S-nitrosylation (or Se-nitrosylation) of TGR. These data allowed us to focus our attention on analogues capable of dual release of NO resulting in agents with superior activity versus ex vivo parasites. We have further defined the selectivity of these agents as compared to other reductases including human GR and rat TrxR (also a selenoprotein). Finally, a preliminary evaluation of selected in vitro pharmacokinetic properties, including water solubility, Caco-2 cell permeability and microsomal stability, suggest that the oxadiazole-2-oxide chemotype can possess the properties required for an orally bioavailable clinical reagent. We are currently developing models to examine the oral efficacy of selected agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Allison Peck for critical reading of this manuscript. This research was supported by the Molecular Libraries Initiative of the National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research, the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Cancer Institute, and Center for Cancer Research. Schistosome life stages used in this research were supplied in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Schistosomiasis Resource Center at the Biomedical Research Institute (Rockville, Maryland, United States) through NIAID Contract N01-AI-30026.

Abbreviations

- TGR

thioredoxin glutathione reductase

- NO

nitric oxide

- PZQ

praziquantel

- GR

glutathione reductase

- TrxR

thioredoxin reductase

- Prx2

peroxiredoxin2

- GSH

glutathione

Footnotes

Supporting Information. An extended table of TGR inhibition and NO release profiles for selected analogues and experimental methods for TGR biochemical assay protocol, Ex vivo worm assay protocol, GR assay protocol, biotin-switch assay protocol, TrxR1 assay protocol (DNTB), NO release protocol, reactivity of oxadiazole-2-oxides with Cys (HPLC Assay) and characterization of compounds are detailed. This material is available free of charge via the Internet.

References

- 1.Hotez PJ, Brindley PJ, Bethony JM, King CH, Pearce EJ, Jacobson J. Helminth infections: the great neglected tropical deseases. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1311–1321. doi: 10.1172/JCI34261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinmann P, Keiser J, Bos R, Tanner M, Utzinger J. Schistosomiasis and water resources development: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimates of people at risk. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:411–425. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Werf MJ, de Vlas SJ, Brooker S, Looman CW, Nagelkerke NJ, Habbema JD, Engels D. Quantification of clinical morbidity associated with schistosome infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Acta Trop. 2003;86:125–139. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(03)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King CH, Dangerfield-Cha M. The unacknowledged impact of chromic schistosomiasis. Chronic Illn. 2008;4:65–79. doi: 10.1177/1742395307084407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gönnert R, Andrews P. Praziquantel, a new broad spectrum antischistosomal agent. Z Parasitenk. 1977;52:129–150. doi: 10.1007/BF00389899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagan P, Appleton CC, Coles GC, Kusel JR, Tchuem Tchuenté LA. Schistosomiasis control: keep taking the tablets. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fenwick A, Webster JP. Schistosomiasis: challenges for control, treatment and drug resistance. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19:577–582. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000247591.13671.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenberg RM. Are Ca2+ channels targets of Praziquantel action? Int J Parasitol. 2004;35:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nogi T, Zhang D, Chan JD, Marchant JS. A Novel Biological Activity of Praziquantel Requiring Voltage-Operated Ca2+ Channel β Subunits: Subversion of Flatworm Regenerative Polarity. PLoS NT D. 2009;3:e464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doenhoff MJ, Cioli D, Utzinger J. Praziquantel: mechanisms of action, resistance and new derivatives for schistosomiasis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:659–667. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328318978f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Townsend DM, Tew KD, Tapiero H. The importance of glutathione in human disease. Biomed Pharmacother. 2003;57:145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(03)00043-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lillig CH, Holmgren A. Thioredoxin and related molecules – from biology to health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:25–47. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alger HM, Sayed AA, Stadecker MJ, Williams DL. Molecular and enzymatic characterisation of Schistosoma mansoni thioredoxin. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:1285–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angelucci F, Miele AE, Boumis G, Dimastrogiovanni D, Brunori M, Bellelli A. Glutathione reductase and thioredoxin reductase at the crossroad: The structure of Schistosoma mansoni thioredoxin glutathione reductase. Proteins. 2008;72:936–945. doi: 10.1002/prot.21986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuntz AN, Davioud-Charvet E, Sayed AA, Califf LL, Dessolin J, Arnér ES, Williams DL. Thioredoxin glutathione reductase from Schistosoma mansoni: an essential parasite enzyme and a key drug target. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Sayed AA, Wang Y, Nelson ME, Thomas CJ, Inglese J, Williams DL, Austin CP. Quantitative high-throughput screen identifies inhibitors of the schistosoma mansoni redox cascade. PLoS NT D. 2008;2:e127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lea WA, Jadhav A, Rai G, Sayed AA, Cass CL, Inglese J, Williams DL, Austin CP, Simeonov A. A 1,536-well-based kinetic HTS assay for inhibitors of Schistosoma mansoni thioredoxin glutathione reductase. Assay Drug Dev Tech. 2008;6:551–555. doi: 10.1089/adt.2008.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Austin CP, Brady LS, Insel TR, Collins FS. NIH Molecular Libraries Initiative. Science. 2004;306:1138. doi: 10.1126/science.1105511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inglese J, Auld DS, Jadhav A, Johnson RL, Simeonov A, Yasgar A, Zheng W, Austin CP. Quantitative high-throughput screening: A titration-based approach that efficiently identifies biological activities in large chemical libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11473–11478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sayed AA, Simeonov A, Thomas CJ, Inglese J, Austin CP, Williams DL. Identification of oxadiazoles as new drug leads for the control of schistosomiasis. Nature Med. 2008;4:407–412. doi: 10.1038/nm1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nwaka S, Hudson A. Innovative lead discovery strategies for tropical diseases. Nature Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:941–955. doi: 10.1038/nrd2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasco A, Fruttero R, Sorba G, Di Stilo A, Calvino R. NO donors: Focus on furoxan derivatives. Pure Appl Chem. 2004;76:973–981. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasco A, Schoenafinger K. The NO-releasing heterocycles. In: Wang G, Cai TB, Taniguchi N, editors. Nitric Oxide Nonors. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim Germany: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nature Rev Drug Disc. 2008;7:156–167. doi: 10.1038/nrd2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paolocci N, Jackson MI, Lopez BE, Miranda K, Tocchetti CG, Wink DA, Hobbs AJ, Fukuto JM. The pharmacology of nitroxyl (HNO) and its therapeutic potential: Not just the janus face of NO. Pharm Ther. 2007;113:442–458. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ignarro LJ. Nitric Oxide Biology and Pathobiology. Academic Press; San Diego: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medana C, Ermondi G, Fruttero R, Di Stilo A, Ferretti C, Gasco A. Furoxans as nitric oxide donors. 4-phenyl-3-furoxancarbonitrile: thiol-mediated nitric oxide release and biological evaluation. J Med Chem. 1994;37:4412–4416. doi: 10.1021/jm00051a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buonsanti MF, Bertinaria M, Di Stilo A, Cena C, Fruttero R, Gasco A. Nitric oxide donor β2-agonists: furoxan derivatives containing the fenoterol moiety and related furazans. J Med Chem. 2007;50:5003–5011. doi: 10.1021/jm0704595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turnbull CM, Cena C, Fruttero R, Gasco A, Rossi AG, Megson IL. Mechanism of action of novel NO-releasing furoxan derivatives of aspirin in human platelets. British J Pharm. 2006;148:517–526. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sorba G, Galli U, Cena C, Fruttero R, Gasco A, Morini G, Adami M, Coruzzi G, Brenciaglia MI, Dubini F. A new furoxan NO-donor rabeprazole derivative and related compounds. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:899–903. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brunet LR. Nitric oxide in parasitic infections. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:1457–1467. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colasanti M, Gradoni L, Mattu M, Persichini T, Salvati L, Venturini G, Ascenzi P. Molecular basis for the anti-parasitic effect on NO. Int J Mol Med. 2002;9:131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rivero A. Nitric oxide: an antiparasitic molecule of invertebrates. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.James SL, Glaven J. Macrophage cytotoxicity against schistosomula of Schistosoma mansoni involves arginine-dependent production of reactive nitrogen intermediates. J Immunol. 1989;143:4208–4212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amri M, Aissa SA, Belguendouz H, Mezioug D, Touil-Boukoffa C. In vitro antihydatic action of IFN- is dependent on the nitric oxide pathway. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2007;27:781–787. doi: 10.1089/jir.2007.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magez S, Radwanska M, Drennan M, Fick L, Baral TN, Allie N, Jacobs M, Nedospasov S, Brombacher F, Ryffel B, De Baetselier P. Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Receptor-1 (TNFp55) Signal transduction and macrophage-derived soluble TNF are crucial for Nitric Oxide-mediated Trypansosoma congolense parasite killing. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:954–962. doi: 10.1086/520815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winberg ME, Rasmusson B, Sundqvist T. Leishmania donovani: inhibition of phagosomal maturation is rescued by nitric oxide in macrophages. Exp Parasitol. 2007;117:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.López-Jaramillo P, Ruano C, Rivera J, Terán E, Salazar-Irigoyen R, Esplugues JV, Moncada S. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis with nitric-oxide donor. Lancet. 1998;351:1176–1177. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh R, Manjunatha U, Boshoff HIM, Ha YW, Niyomrattanakit P, Ledwidge R, Dowd CS, Lee IY, Kim P, Zhang L, Kang S, Keller TH, Jiricek J, Barry CE. PA-824 Kills Nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis by Intracellular NO Release. Science. 2008;322:1392–1395. doi: 10.1126/science.1164571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mady C, Ianni BM, de Souza JL., Jr Benznidazole and Chagas disease: can an old drug be the answer to an old problem? Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:1427–1433. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.10.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilkinson SR, Taylor MC, Horn D, Kelly JM, Cheeseman I. A mechanism for cross-resistance to nifurtimox and benznidazole in trypanosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5022–5027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711014105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nims RW, Darbyshire JF, Saavedra JE, Christodoulou D, Hanbauer I, Cox GW, Grisham MB, Laval F, Cook JA, Krishna MC, Wink DA. Colorimetric methods for the determination of nitric oxide concentration in neutral aqueous solutions. Methods. 1995;7:48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akaike T, Yoshida M, Miyamoto Y, Sato K, Kohno M, Sasamoto K, Miyazaki K, Ueda S, Maeda H. Antagonistic action of imidazolineoxyl N-Oxides against endothelium-derived relaxing factor/NO through a radical reaction. Biochemistry. 1993;32:827–832. doi: 10.1021/bi00054a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rai G, Thomas CJ, Leister W, Maloney DJ. Synthesis of oxadiazole-2-oxide analogues as potential antischistosomal agents. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:1710–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.01.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lei SZ, Pan ZH, Aggarwal SK, Chen HS, Hartman J, Sucher NJ, Lipton SA. Effect of nitric oxide production on the redox modulatory site of the NMDA receptor-channel complex. Neuron. 1992;8:1087–1099. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stamler JS, Simon DI, Osborne JA, Mullins ME, Jaraki O, Michel T, Singel DJ, Loscalzo J. S-Nitrosylation of proteins with nitric oxide: synthesis and characterization of biologically active compounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:444–448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Becker K, Savvides SN, Keese M, Schirmer RH, Karplus PA. Enzyme inactivation through sulfhydryl oxidation by physiologic NO-carriers. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:267–271. doi: 10.1038/nsb0498-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Badorff C, Fichtlscherer B, Rhoads RE, Zeiher AM, Muelsch A, Dimmeler S, Knowlton KU. Nitric oxide inhibits dystrophin proteolysis by coxsackieviral protease 2A through S-nitrosylation. Circulation. 2000;102:2276–2281. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.18.2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saura M, Zaragoza C, McMillian A, Quick RA, Hohenadl C, Lowenstein JM, Lowenstein CJ. An antiviral mechanism of nitric oxide: Inhibition of a viral protease. Immunity. 1999;10:21–28. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xian M, Wang QM, Chen X, Wang K, Wang PG. S-Nitrosothiols as novel, reversible inhibitors of human rhinovirus 3C protease. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:2097–2100. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jaffrey SR, Snyder SH. The biotin switch method for the detection of S-nitrosylated proteins. Sci STKE. 2001;86:pl1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.86.pl1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaffrey SR, Fang M, Snyder SH. Nitrosopeptide mapping: A novel methodologyrevease S-nitrosylation of Dexras1 on a single cysteine residue. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1329–1335. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chakrapani H, Bartberger MD, Toone EJ. C-Nitroso Donors of Nitric Oxide. J Org Chem. 2009;74:1450–1453. doi: 10.1021/jo802517t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oballa RM, Truchon JF, Bayly CI, Chauret N, Day S, Crane S, Berthelette C. A generally applicable method for assessing the electrophilicity and reactivity of diverse nitrile-containing compounds. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:998–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fontijn A, Sabadell AJ, Ronco RJ. Homogeneous Chemiluminescent Measurement of Nitric Oxide with Ozone. Anal Chem. 1970;42:575–579. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hatfield DL, Carlson BA, Xu XM, Mix H, Gladyshev VN. Selenocysteine incorporation machinery and the role of selenoproteins in development and health. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2006;81:97–142. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(06)81003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kryukov GV, Gladyschev VN. The prokaryotic selenoproteome. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:538–543. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benesch RE, Benesch R. The acid strength of the SH group in cysteine and related compounds. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:5877–5881. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huber RE, Criddle RS. Comparison of the chemical properties of selenocysteine and selenocystine with their sulfur analogs. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1967;122:164–173. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(67)90136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johansson L, Gafvelin G, Arnér ESJ. Selenocysteine in proteins-properties and biotechnological use. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2005;1726:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Castellano S, Andrés AM, Bosch E, Bayes M, Guigó R, Clark AG. Low Exchangeability of Selenocysteine, the 21st Amino Acid, in Vertebrate Proteins. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:2031–2040. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hickey JL, Ruhayel RA, Barnard PJ, Baker MV, Berners-Price SJ, Filipovska A. Mitochondria-Targeted Chemotherapeutics: The Rational Design of Gold (I) N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes that are Selectively Toxic to Cancer Cells and Target Protein Selenols in Preference to Thiols. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12570–12571. doi: 10.1021/ja804027j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anestål K, Prast-Nielsen S, Cenas N, Arnér ESJ. Cell Death by SecTRAPs: Thioredoxin Reductase as a Prooxidant Killer of Cells. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhong L, Arnér ESJ, Ljung J, Aslund F, Holmgren A. Rat and calf thioredoxin reductase are homologous to glutathione reductase with a carboxyl-terminal elongation containing a conserved catalytically active penultimate selenocysteine residue. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8581–8591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.