Abstract

This work demonstrates the assembly of TiO2 nanoparticles with attached DNA oligonucleotides into a 3D mesh structure by allowing base pairing between oligonucleotides. A change of the ratio of DNA oligonucleotide molecules and TiO2 nanoparticles regulates the size of the mesh as characterized by UV-visible light spectra, transmission electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy images. This type of 3D mesh, based on TiO2-DNA oligonucleotide nanoconjugates, can be used for studies of nanoparticle assemblies in material science, energy science related to dye-sensitized solar cells, environmental science as well as characterization of DNA interacting proteins in the field of molecular biology. As an example of one such assembly, proliferating cell nuclear antigen protein (PCNA) was cloned, its activity verified, and the protein was purified, loaded onto double strand DNA oligonucleotide-TiO2 nanoconjugates, and imaged by atomic force microscopy. This type of approach may be used to sample and perhaps quantify and/or extract specific cellular proteins from complex cellular protein mixtures affinity based on their affinity for chosen DNA segments assembled into the 3D matrix.

Keywords: Titanium dioxide nanoparticles, DNA, PCNA protein, atomic force microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, assembly, agarose, nanoconjugate

1. Introduction

A titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticle (NP) is a photo-catalytic, broad-band-gap semiconductor nanomaterial that is highly stable, non-toxic, and inexpensive.1 TiO2 is widely used in diverse research and industrial fields: 1) in environmental science as a non-toxic photocatalyst for oxidative decomposition of various organic and gas pollutants;2 2) in biological science as a TiO2-DNA oligonucleotide nanoconjugate for subcellular targeting;3, 4 and 3) in energy science as a key component of dye-sensitized solar cells capable of converting sunlight into chemical energy.5 In all of these three areas of investigation, the use of TiO2 nanoparticles organized into a 3D superstructure could lead to more efficient approaches to reach the desired goals. In environmental science, a 3D mesh may be a more efficient photocatalyst than random nanoparticle assemblies. In energy science, recent research on dye-sensitized solar cells has demonstrated that organized, orderly TiO2 nanoparticles increase solar conversion efficiency by 50% compared to traditional TiO2 films composed of randomly distributed nanoparticles.6 In biology, characterization of DNA interacting proteins done in a repetitive 3D matrix may increase the speed of discovery of novel protein-nucleic acid interactions and complicated DNA-multi protein complexes.

An efficient way to pre-organize TiO2 nanoparticles into two-dimensional (2-D) or three-dimensional (3-D) superstructures is to use short molecules of DNA-oligonucleotides as linkers.7 There are three known approaches by which DNA was used as a mediator of nanoparticle formation or for building of nanoparticle assemblies. First, DNA can be used as an electronegative structure attracting metal cations to be adsorbed onto the DNA backbone and then subsequently become reduced into continuous nanoparticulate-superstructures.8 Second, modified nanoparticles/nanocrystals with positively charged shells can be assembled along DNA molecule backbones as a guiding, negatively charged “organizer” molecule.9 Finally, nanoparticles/nanocrystals with DNA tethered to them can form different superstructures due to base pairing.10 In this work, we describe approaches to assemble TiO2 nanoparticles through hybridization of DNA tethered onto them into nanoconjugate superstructures.

2. Experimental Section

1). Methods

(1) Conjugation of DNA oligonucleotides to TiO2 nanoparticles

The preparation of colloidal TiO2 has been described in detail elsewhere.3 Briefly, synthesis was done in aqueous solution by adding TiCl4 dropwise to cooled water. Nanoparticles of 3-6 nm were prepared. Previous work has shown TiO2 spheres of this size are anatase crystals; their conjugation with dopamine is stable for years, therefore stability of nanoparticle-oligonucleotide nanoconjugates matches stability of free DNA oligonucleotides which is about one month at 4°C.3,12 DNA oligonucleotides used in these experiments were “T2” 5′ carboxy-dTCAGCCTGGTCTACCAAGCAAACTCCAGTACAGCCAGGGAACATGAGAGAC 3′ and “T5” 5′ carboxy-dTGTCTCTCATGTTCCCTGGCTGTACTGGAGTTTGCTTGGTAGACCAGGCTG 3′. These oligonucleotides (Midlands Scientific, TX) were synthesized to be complementary to each other; together they hybridize into double-stranded DNA. Synthesis was carried out so that both oligonucleotides have a 5′ terminal carboxyl group; oligonucleotide stocks are stored frozen at -80 °C as a 100 μM stock solution in 10 mM Na2HPO4 phosphate buffer (10 mM phosphate; 20 mM sodium) at pH 6.5. A condensation reaction through intermediate N-hydroxyl-succinimide ester was used to bind the carboxyl group of the oligonucleotide to the amino group of dopamine by an amide bond.11 Briefly, the DNA terminal carboxyl group of oligonucleotides is bound to O-N-succinimidyl-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate (TSTU) in the presence of N,N-diisopropylethyl amine (i-PRTEN) in N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF). In the second step, the succinimidyl group is replaced with dopamine through its terminal amino group in the presence of dioxane. This solution was thoroughly dialyzed against water to remove free dopamine unbound to oligonucleotides. In the final step, dopamine end-labeled oligonucleotides are bound to TiO2 particles modified by glycidyl isopropyl ether (GIE).3 The stability of the dopamine-surface TiO2 complex is stronger than the stability of the complex formed between the TiO2 surface and glycidyl isopropyl ether, and therefore dopamine easily replaces GIE at the nanoparticle surface.12 At the conclusion of this procedure nanoconjugates are stored in 10 mM Na2HPO4 phosphate buffer pH=6.5. The amide bond between dopamine and oligonucleotide is stable, and the stability of the bond between dopamine and the surface of the TiO2 nanoparticle is also great. Thus, oligonucleotide-modified nanoparticles behave similar to ‘free’ oligonucleotides, and they are stable for up to one month when stored in the refrigerator at 4 °C.

Due to the fact that dopamine modified oligonucleotides readily bind nanoparticle surface, we were able to accomplish different DNA oligonucleotide loading per nanoparticle by using different mixing ratios of nanoparticles and oligonucleotide DNA molecules. Rapid mixing of the two components of the nanoconjugate lead to a reaction where average number of oligonucleotides per nanoparticle is controlled by DNA:nanoparticle stoichiometry. Two different ratios of DNA oligonucleotide: nanoparticle were used to achieve high DNA or low DNA oligonucleotide loading per nanoparticle. For high DNA loading per nanoparticle 50 μL of 100 μM T2 or T5 oligonucleotide was mixed with 200 μL of 10 μM of nanoparticle; for low DNA loading per nanoparticle 50 μL of 20 μM T2 or T5 oligonucleotide was mixed with 200 μL of 10 μM of nanoparticle.

(2) Annealing of Complementary DNA-TiO2 Nanoconjugates

For the creation of double-stranded TiO2-dsDNA-TiO2 nanoparticle dumbbells and [-TiO2-dsDNA-]n superstructures, TiO2-T2 and TiO2-T5 nanoconjugates were mixed in equal molar ratios and incubated for 3 min at 95 °C followed by gradual cooling to room temperature overnight. Because these nanoconjugates were suspended in 10 mM disodium phosphate buffer, presence of sodium (20 mM final concentration) aided the hybridization. Generally, hybridization reactions often require higher concentrations of sodium; nevertheless, oligonucleotides used were 50 mers and their hybrids were very stable in 20 mM sodium, with about 65°C melting temperature. In those cases when nanoparticle superstructures were to be embedded in agarose, pre-melted 2% agarose in 10 mM disodium phosphate buffer pH=6.5 was added to the nanoparticles V:V at 95 °C. As agarose solidified, it embedded the [-TiO2-dsDNA-]n superstructures in 3D space. All of these reactions were carried out in total volumes of 200 to 400 μL.

For PCNA protein loading onto the nanoconjugates, nanoconjugates with double strand DNA were prepared by annealing between TiO2-T2 nanoconjugate and free T5 oligonucleotide. Purified PCNA protein was mixed with TiO2-dsDNA in a molar ratio in excess of 3:1 because PCNA protein loads onto DNA by forming trimers.13

(3) Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) Protein Cloning and Isolation

PCNA gene cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using PCNA specific primers (sense 5′atgttcgaggcgcgcctggtc and antisense 5′ agatccttcttcatcctcga). Once cloned and verified by sequencing, this coding DNA was re-cloned into a plasmid pEF6/V5-His (Invitrogen) wherein additional coding sequence was added at the C or N terminus of the PCNA coding sequence, introducing a V5 epitope and six consecutive histidine amino acids at either end of the PCNA protein coding sequence. These additional histidines allowed the cloned protein to be purified on a nickel-containing column, using Ni column kit (Quiagen). Epitope V5 of the PCNA protein is used for immunohistochemistry differentiation between native and cloned protein. The human breast cancer cell line MCF-7/WS8 (American Type Culture Collection) was grown in 5% CO2 in RPMI1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, with the addition of antibiotic and antimycotic. Recombinant PCNA gene was introduced into the cells complexed with the SuperFect Reagent (Qiagen). Three days after transfection recombinant PCNA protein was isolated and a nickel-containing bead column (Dynal) was used for protein purification. A standard Western blot was used to confirm the size of the purified protein (data not shown).

(4) PCNA Protein Function Verification

MCF-7/WS8 human breast cancer cells were grown on glass coverslips until they reached ∼40% confluency, and then they were transfected with a recombinant PCNA gene construct. After 24 hours, transfected cells were rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fixed in ice-cold methanol for 5 minutes, and rinsed again with PBS containing 0.01 % Tween and 0.5 % bovine serum albumin (BSA) prior to staining with antibodies. Transfected cells were stained with an antibody against the V5 epitope (anti-V5 mouse antibody, Invitrogen), present in the recombinant PCNA protein, and a secondary antibody (rabbit anti-mouse antibody labeled with rhodamine, Rockland); while control cells were stained for endogenous PCNA (mouse anti-PCNA FITC-conjugated antibody, Chemicon International). All cells were rinsed three times with a PBS-Tween-BSA solution, mounted on slides using a PPD mounting media (1mg/mL P-phenylenediamine, 10mM Tris buffer at pH 8.5 and 50% glycerol, all components obtained from Sigma), and imaged by confocal fluorescence microscopy to determine if the recombinant PCNA displayed during synthesis phase (S phase) of the cell cycle shows the same subcellular localization patterns as endogenous (non-recombinant) PCNA.

(5) Sample Preparation for Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

For each TEM sample 6μL of nanoconjugates, hybridized nanoconjugates or nanoconjugate superstructures were stained with 5 μL of 1.5% uranyl acetate solution and deposited on gold grids with carbon film coating for support. Uranyl acetate staining was done in order to stain DNA and allow imaging of the DNA components of the nanoconjugates under the electron beam.14 These samples were rinsed in double distilled water three times, excess water was removed by filter paper and the samples were dried for 1-3 hours before storage.

The samples embedded in agarose were processed as it is usually done with cultured cells prepared for TEM.15 Nanoconjugates with complementary DNA sequences were first allowed to hybridize in solution as it was cooling from 90°C to 50°C. At that temperature, melted agarose at 50°C was added to these samples and their cooling continued until they reached room temperature. During cooling the agarose was gradually solidifying thus capturing the hybridized nanoconjugate network in 3D space; from being free floating in suspension, the network became embedded in agarose substrate. Subsequently, the agarose block with 3D mesh structure suspended in it in 3D was cut into 1-2mm cubes, dehydrated in a series of solvents commonly used for preparation of cells and tissues as TEM samples; in the end, final solvent was replaced by epon resin. Finally, liquid resin solution permeating the agarose was solidified by baking. Once embedded in resin these samples were sectioned at roughly 200 nm, stained by uranyl acetate and imaged at the Cell Imaging Facility. Uranyl acetate does not stain the agarose but it does stain DNA, as known from the studies of agarose embedded cultured cell samples imaging by TEM (upon staining, cell nuclei are very visible while agarose matrix remains entirely transparent).

(6) Sample Preparation for Atomic Force Microscopy

The freshly cut mica was used as an imaging substrate. Usually, 5 μL of 5mM of MgCl2 solution was deposited on the newly cleaved mica surface to create a positive charged interface to immobilize the negatively charged TiO2–DNA nanoconjugates. After 5-10 minutes, the modified surface was rinsed with double distilled water and pure ethanol three times each to remove the unbound Mg2+ and other inorganic and organic impurities.

For preparation of nanoconjugates with PCNA protein loaded onto them, we used low DNA loading nanoconjugates TiO2-T2 and free complementary oligonucleotides T5 to anneal TiO2-dsDNA nanoconjugates. A drop of 20 μL of these nanoconjugates were mixed with purified recombinant PCNA protein from 10 million MCF-7/W8 cells transfected with the recombinant PCNA gene in a buffer containing 30 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 5% glycerol, 40 mM KCl, and 8 mM CaCl2 thus modifying a procedure published by others.13 After application of the sample onto mica, extensive washes were performed.

2) Equipment

(1) UV–Visible Light Spectrometry

The optical properties of TiO2 nanoparticles, TiO2-T2 and TiO2-T5 (TiO2-ssDNA) nanoconjugates and hybridized TiO2-T2-T5-TiO2 (TiO2-dsDNA-TiO2 and [-TiO2-dsDNA-]n) nanoconjugate solutions and superstructures were monitored by NanoDrop (ND-1000) spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Each time 2 μL of sample solution was used for measurement.

(2) Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

A JEOL 1220 transmission electron microscope at Cell Imaging Facility at Northwestern University, equipped with a megapixel-resolution Kodak digital camera and operated at 60 kV, was used for measurements.

(3) AFM Imaging

AFM images were acquired using a Digital Instruments Multimode atomic force microscope (Veeco Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA) equipped with a NanoScope IIIa controller and an E-scanner, at NUANCE center of Northwestern University. Imaging was performed in tapping mode in air. Single-crystalline ultrasharp silicon tips were used (Veeco Instruments) for imaging. These AFM silicon probe tips have 20-50 nm diameter; therefore the images of structures smaller than 20nm are difficult to distinguish and appear deformed compared to the original structures.16 All images are presented after flattening.

(4) Confocal Fluorescent Microscopy

We used a LSM 510 laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss) at the Northwestern University Cell Imaging Facility. Excitation lasers and emission filters for fluorophores were set as follows: for rhodamine 543nm and 560-615nm and for FITC 488nm and 505-530nm. An optical slice of approximately 1 μm was taken through the midsection of the cell nucleus.

3. Results and Discussion

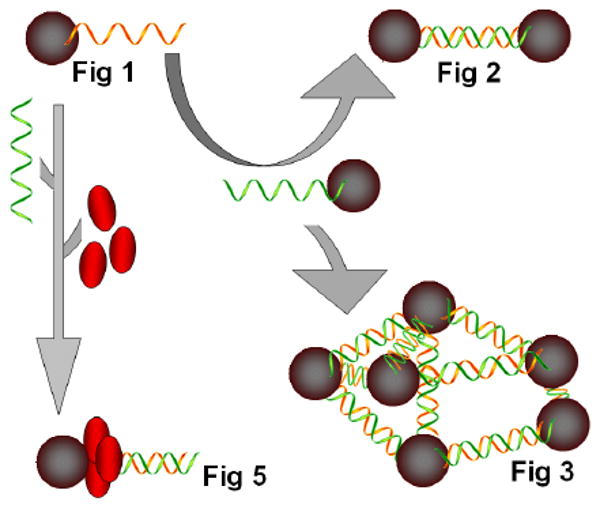

Our strategy for assembling TiO2 nanoparticles to form either 2D structures such as dumbbells or 3D net superstructures is shown in the Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

A schematic presentation of preparation of TiO2 nanoconjugate assemblies shown in Figures 1, 2, 3 and 5. Represented (in clockwise direction) are: single nanoconjugate TiO2-ssDNA (presented in Figure 1); a nanoconjugate combined with low DNA load complementary nanoconjugate to form TiO2-dsDNA-TiO2 assemblies of only several nanoconjugates (presented in Figure 2); nanoconjugates combined with high DNA load complementary nanoconjugates to form [-TiO2-dsDNA-]n assemblies (presented in Figure 3); a single nanoconjugate TiO2-ssDNA hybridized with a complementary ssDNA to form a TiO2-dsDNA was subsequently loaded with PCNA protein monomers (presented in red) to form TiO2-dsDNA-PCNA trimers (Figure 5).

First, the 5′ terminal carboxyl groups of DNA oligonucleotides T2 and T5 (for their sequences see Materials Section) were each conjugated with dopamine molecules to form two dopamine-single stranded DNA complexes. Secondly, these oligonucleotides were conjugated separately with TiO2 nanoparticles to form TiO2-ssDNA nanoconjugates via bidentate complexes between the -OH groups of dopamine and under-coordinated Ti-O molecules on the surface of TiO2 nanoparticles. Two different ratios of DNA:nanoparticle were used; 2:1 for nanoconjugates with low oligonucleotide loading and 10:1 for nanoconjugates with high oligonucleotide loading. Thirdly, solutions containing complementary-sequence nanoconjugates TiO2-T2 and TiO2-T5 were mixed in equal volumes and nanoconjugates were annealed to each other, since T2 and T5 are complementary oligonucleotides and form dsDNA. When high loading of DNA per nanoparticle was used 3D network superstructures (predominant formula of these structures is [-TiO2-dsDNA-]n) were formed through DNA base pairing interactions. When low DNA loading per nanoparticle was used, nanoconjugates assemble the TiO2 nanoparticles into dumbbells (predominant formula of these structures is TiO2-dsDNA-TiO2) or three point rods. Theoretical length of 50 nucleotides long DNA molecule that is formed by hybridization of T2 and T5 oligonucleotides is about 17 nm.

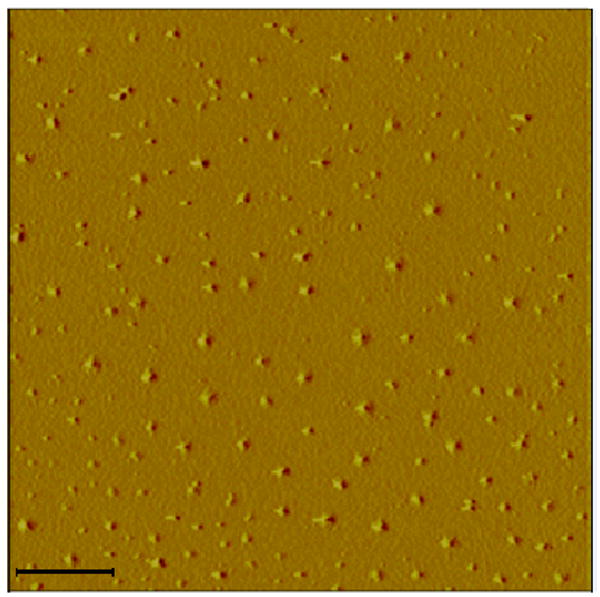

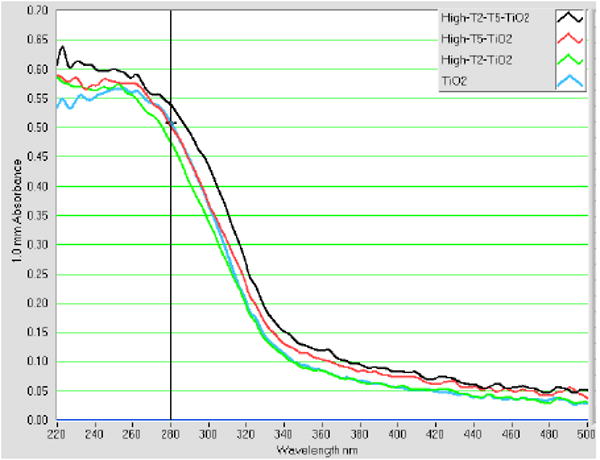

Nanoparticles and nanoconjugates that do not form mismatch structures do not aggregate as shown by AFM analysis (Figure 1a) and the UV-vis spectra absorbance (Figure 1b). In Figure 1a, a large area of mica shows well dispersed nanoconjugates, with occasionally easily distinguishable attached DNA molecules. These were TiO2-T2 (TiO2-ssDNA) nanoconjugates with low DNA loading. The UV-visible spectra of TiO2 nanoparticles, TiO2-oligonucleotide nanoconjugates, and hybridized nanoconjugates superstructure [-TiO2-dsDNA-]n are shown in Figure 1b. Free nanoparticle and one type of nanoconjugates (TiO2-T2 oligonucleotide) showed almost identical UV-vis spectra. Another type of nanoconjugate (TiO2-T5 oligonucleotide) showed a minor red shift, suggesting nanoparticle “aggregation” which is caused by the propensity of this TiO2-ssDNA to form relatively stable mismatch dimmers (hence it forms low quantity of TiO2-dsDNA- TiO2). Finally, the nanoconjugate assembly formed after annealing of complementary nanoconjugates shows a much more obvious red shift caused by “aggregation” of nanoconjugates into an semi-ordered [-TiO2-dsDNA-]n structure, where [-TiO2-dsDNA-]n is formed through hybridization of fully complementary DNA oligonucleotides attached to the nanoparticles. It is well known that aggregation of nanoparticles/nanocrystals into quasi -two-dimensional or -three-dimensional superstructures causes a red shift of the absorbance peak because of an appearance of a longitudinal component in the spectra in the assembled nanoconjugates.9b, 17 We find that in our samples that such “aggregation” depends on DNA oligonucleotide hybridization.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1a. AFM topographical image of TiO2–ssDNA (prepared with T2 ssDNA oligonucleotide) nanoconjugates. These TiO2 nanoconjugates show no spontaneous aggregation and are well dispersed, which matches the behavior of these nanoconjugates detected by UV-visible light absorption analysis (Figure 1b). Scale bar is 100 nm.

Fig. 1b. UV-vis spectra of nanoparticles, nanocomposites and nanocomposite assembly.

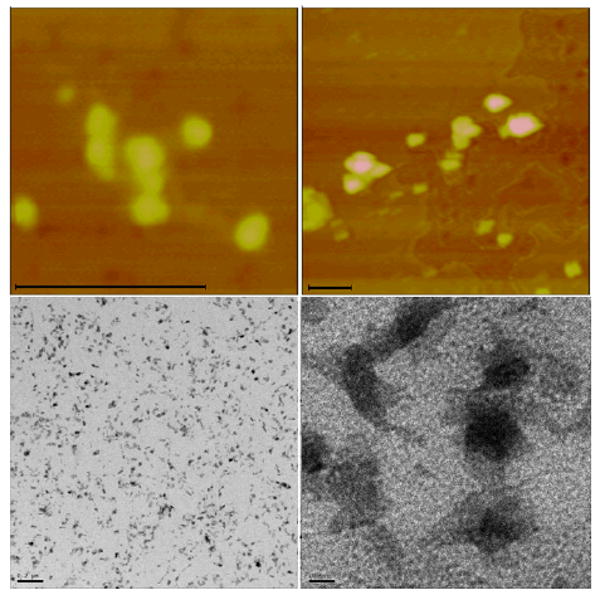

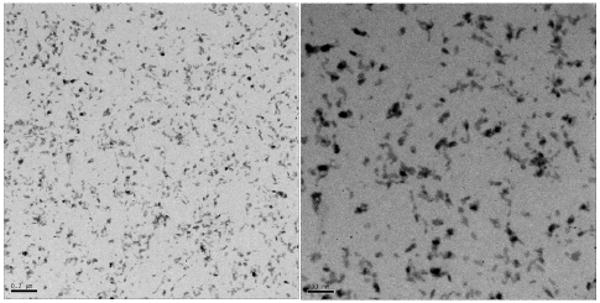

Figure 2a shows the mini-assemblies made of nanoconjugates with low DNA loading. These structures are predominantly dumbbells or three point rods and their formula is best described as TiO2-dsDNA-TiO2. Images in Figure 2a are two AFM topological images and two TEM images with lower and higher magnification. TEM samples were stained by uranyl acetate which stains DNA and lends it sufficient contrast to render it visible in TEM. Limited assembly sizes are visible in both AFM and TEM images and in the additional TEM images (Figure 2b). These assembles are formed through hybridization of DNA oligonucleotides; since there are only a few DNA molecules per each nanoparticle, these assemblies are limited in size.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2a. Topographic AFM images (top row) of TiO2-dsDNA-TiO2 nanoconjugate 2D assemblies TiO2-dsDNA-TiO2 formed from nanoconjugates with low DNA loading (DNA:TiO2=2:1), as explained in the text and Scheme 1; and TEM images (bottom row) of the same type of assemblies, deposited on carbon coated gold EM grids, stained by uranyl acetate. Scale bars for AFM images are 100 nm; and 200 and 10 nm for TEM images (left to right).

Fig. 2b. TEM of TiO2-dsDNA-TiO2, 200 and 100 nm scale (Left to Right).

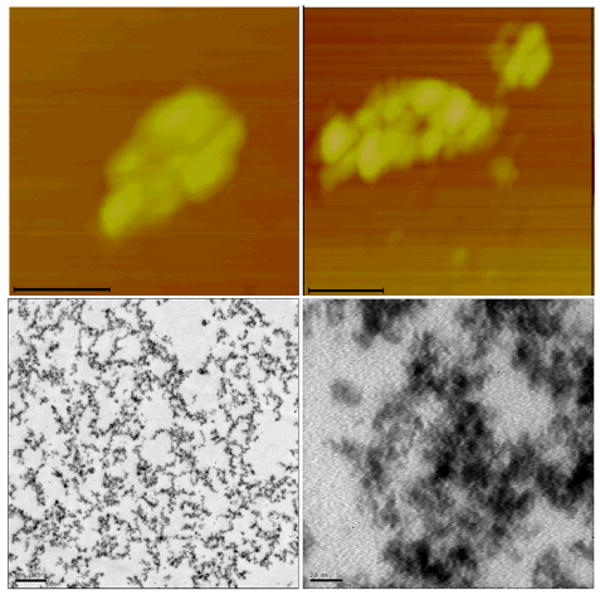

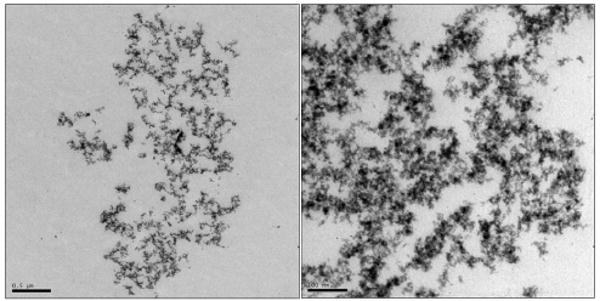

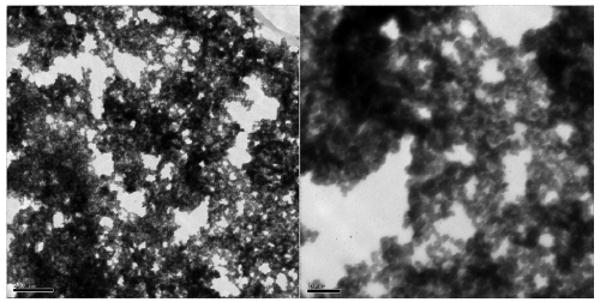

In Figure 3a, two topologic AFM images and two TEM images with lower and higher magnification show the complexes composed of TiO2 nanoconjugates with high DNA loading (∼10 DNA molecules per each TiO2 nanoparticle). Because these nanoconjugates have high oligonucleotide loading each nanoparticle formed many hybridization connections with many other nanoconjugates, thus assembling into a large-scale TiO2 nanoconjugate superstructure, a 3D network which can best be explained by the formula [TiO2-dsDNA-]n. In the TEM images samples were “frozen” in agarose and subsequently dehydrated and embedded in resin in such a way as to preserve the structure of the nanoconjugate network in 3D. This approach was borrowed from the cell embedding procedures for TEM which help preserve the 3D subcellular structures during dehydration and embedding. DNA of the nanoconjugates was stained by uranyl acetate during preparation of TEM samples, and is now visible as the lighter gray fronds of material, while nanoparticles look spherical. In AFM images, such assemblies appear as large nanoparticle aggregates, very different than the nanoconjugates not assembled into networks by hybridization (Figure 1a). Additional TEM images of this type of large nanoconjugate network are shown in Figures 3b and 3c (both with resin embedding and sectioning and with drying of the network without embedding.).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3a. AFM (top row) topographical images and TEM (bottom row) images of uranyl acetate stained nanoconjugate superstructures [TiO2-dsDNA-]n formed by hybridization of nanoconjugates with high DNA loading (DNA:TiO2=10:1), as explained in the text and Scheme 1. Scale bars on AFM images are 100 nm, and on the TEM images 500 and 20 nm (left to right). TEM image was prepared from a sample which was embedded in agarose post-hybridization in order to preserve the 3D structure of the nanoconjugate assembly; this assembly was prepared for 2D TEM imaging by sectioning.

Fig. 3b. TEM of –[TiO2-dsDNA]- in agarose, scale bar: 500 nm (Left) and 100 nm (Right).

Fig. 3c. TEM of –[TiO2-dsDNA]- without agarose, scale bar: 200 nm (Left) and 50 nm (Right).

In an effort toward the use of nanoconjugate networks as matrices for loading and study of DNA binding proteins, we initiated a proof of principle work with proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) protein and nanoconjugates. As a first step in this work, we cloned PCNA coding sequence into a protein expression plasmid that functions in eukaryotic cells. This created a recombinant protein sequence that could be expressed in eukaryotic cells. Therefore we were able firstly to prove correct DNA binding behavior of this recombinant PCNA protein; and secondly, to isolate the recombinant protein in order to use it in vitro for loading onto nanoconjugate dsDNA.

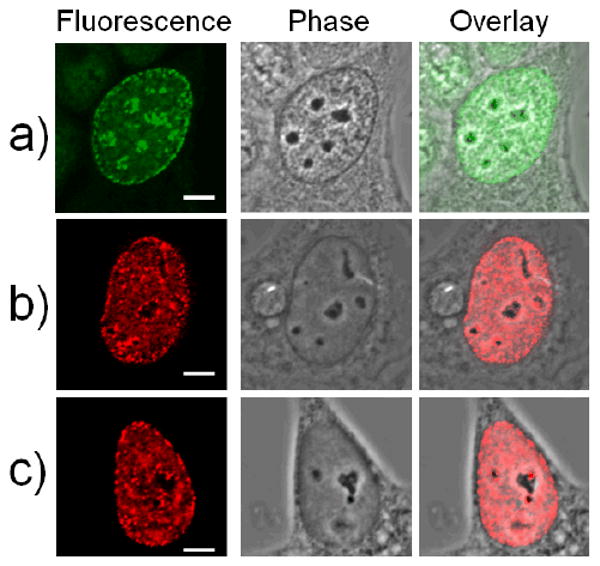

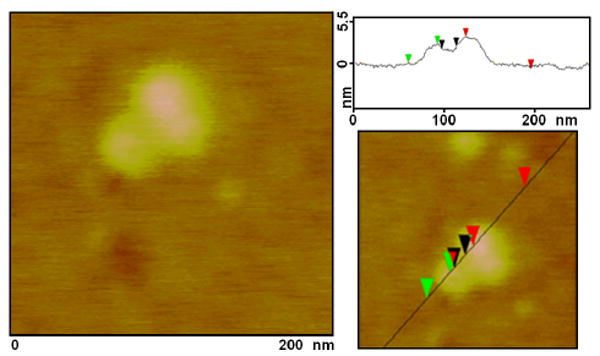

The protein PCNA is distributed in a diffuse pattern in the nuclei of cells in G1 stage of the cell cycle, while its distribution during the synthesis (S) phase of the cell cycle is punctuate. Specifically, in mid-S phase of the cell cycle PCNA distribution (in addition to remaining punctuate throughout the nucleus) becomes perinuclear and perinucleolar. This mid-S phase PCNA distribution is the defining mark of cells at this stage of DNA synthesis and has been extremely well documented in the literature over the last two decades.18 Both of the recombinant PCNA proteins we cloned showed this pattern of intracellular distribution (Figure 4). Recombinant PCNA was found (i) in the nucleus only, with no protein in the cytoplasm; (ii) showing punctuate (not diffuse) mid-S phase perinuclear and perinucleolar pattern, which demonstrates that the mutant protein follows the distribution pattern of the wild type/endogenous PCNA protein. This signifies that the recombinant PCNA is both translocated from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and loaded onto DNA inside the nucleus (punctuate pattern) just as the native protein. Overexpressed proteins very often completely fill the nucleus and cytoplasm of the cell in a diffuse manner, making comparisons between distributions of mutants and endogenous proteins impossible. The fact that these recombinant PCNA proteins display the characteristic perinuclear and perinucleolar distributions associated with middle synthesis phase (rather than that completely filling the entire nucleus and cytoplasm of the cell) attests to their functionality. As a next step, we assembled monomeric PCNA protein into trimers on dsDNA of TiO2-dsDNA nanoconjugates and imaged the nanoconjugate-PCNA trimer complexes by AFM (explanation on Scheme 1, Figure 5). PCNA protein loading onto DNA was done under experimental conditions used by others to load and arrest the PCNA protein trimers on fork shaped DNA oligonucleotides.13 Under experimental conditions established by Tom and others13 and used in this experiment, PCNA trimers can not traverse triple DNA helix (about 3nm width); likewise they are unable to pass over the nanoparticle (5-10nm), and tethering of nanoparticles to DNA prevented PCNA trimers from slipping off the DNA. Sample of TiO2-dsDNA-PCNA3 was applied onto mica, extensively washed and imaged by AFM. AFM was performed in air, and dry PCNA trimers (∼70 kD ring around DNA) on dsDNA on the nanoconjugate appeared about 2.5 nm high. Therefore, dsDNA associated with nanoparticles presents an acceptable substrate for DNA binding proteins.

Fig. 4.

Confocal fluorescence imaging of individual MCF7/W8 cells stained with antibodies for native proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (green) and two different recombinant PCNA proteins (red). All three cells presented are in synthesis (S) stage of the cell cycle and demonstrate (i) perinuclear and (ii) perinucleolar distribution patterns characteristic of middle synthesis phase of the cell cycle, when the pattern of PCNA protein localization is most distinct. (a) Native PCNA protein pattern showing early middle S phase PCNA staining pattern; (b) Recombinant PCNA protein extended at C terminus shows middle S phase PCNA staining pattern; (c) Recombinant PCNA protein extended at N terminus, shows middle S phase PCNA staining pattern. Scale bar is 5 μm.

Fig. 5.

Topographic AFM image (and accompanying height graph) of a TiO2-dsDNA nanoconjugate loaded with a trimer of recombinant PCNA, according to the procedure of Tom and others (Tom S et al., 2000, J Biol. Chem.). This protein trimer is about 70 kDal in size. In this and other cases PCNA trimer height appeared to be about 2.5 nm. Nanoparticle sizes showed average heights of 5-10 nm.

4. Conclusions

Using different oligonucleotide loading, we synthesized nanoconjugates with an average of 2 oligonucleotides per nanoparticle (low DNA loading) or 10 ssDNA oligobnucleotides per nanoparticle (high DNA loading). Using the first of these two different nanoconjugate formulations (low DNA loading) we were able to create simple, 2D structures with several nanoconjugates hybridized to each other as dumbels or three point rods. Hybridization of the nanoconjugates with high DNA loading, on the other hand, led to creation of nanoconjugate 3D networks. To prepare TiO2-ssDNA nanoconjugates we used dopamine as a connector between metal oxide and DNA oligonucleotide. TiO2-ssDNA nanoconjugates were assembled via a bidentate complex of the -OH groups on dopamine and under-coordinated Ti atoms on the surface of TiO2 nanoparticles.12 This approach was previously used by us;3,4 moreover, other groups used dopamine as a connector between dopamine functionalized proteins and surface of another metal oxide nanoparticle Fe3O4.19 In order to create nanoconjugate assemblies we employed the process of temperature sensitive DNA oligonucleotide hybridization, a DNA sequence dependent process which can be easily controlled through the choice of the sequence used.

A change of the ratio of between DNA oligonucleotides and TiO2 nanoparticles determined which superstructures were formed between nanoconjugates carrying complementary DNA sequences. A low oligonucleotide per nanoparticle loading resulted in formation of simple dumbbell structures with no more than several nanoparticles, while nanoparticles with high oligonucleotide loading assembled into complex 3D structures. This approach of assembling the TiO2 nanoparticles may be useful for environmental sciences, nanomaterial sciences and energy science related to dye-sensitized solar cells;2-6 due to the high specificity of DNA hybridization and ability to control the distance between nanoparticles within the assembled nanoconjugates network.

The nanoconjugate 3D networks allow for diverse applications in biomedicine and biology due to the inherent biocompatibility of TiO2 nanoparticles.3,4,20 For example, working with cells in culture, we were able to show that TiO2 nanoconjugates with DNA oligonucleotides have the ability to hybridize with the cellular genomic and mitochondrial DNA; this capacity of nanoconjugates can be used for biomedical imaging.3,4,20,23 Additional possible uses of nanoconjugates for basic molecular biology research can be envisioned as well. As an example, we were able to show that a recombinant PCNA protein can assemble into trimers on TiO2-dsDNA nanoconjugates, just as it does on fork-shaped oligonucleotides.13,2 In cells, PCNA forms a homotrimeric ring that serves as a DNA sliding clamp for DNA polymerase delta and other proteins important in DNA replication. PCNA also interacts with many other proteins, including those involved in Okazaki fragment joining, DNA mismatch repair, DNA methylation and chromatin assembly/reorganization, acting as a docking station for these proteins.22 Now, using nanoconjugate networks as ordered 3D DNA arrays we may be able to characterize DNA interactions with DNA binding proteins in novel structural-functional ways. Each unit of the 3D mesh has the same dsDNA sequence segment and we may now be able to study individual proteins' interactions with such DNA sequence segments. Additionally, this approach may be used to sample (and perhaps quantify and/or extract from complex cellular protein mixtures) specific cellular proteins that have affinity for chosen DNA segments assembled into the 3D matrix.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants CA107467, EB002100, U54CA63920, and P50 CA89018. We also thank both Cell Imaging Facility and NUANCE center of Northwestern University for the use of TEM and AFM equipment and Mr. Lennell Reynolds of Cell Imaging Facility for resin embedding and sectioning of agarose embedded samples.

References

- 1.Chen X, Mao SS. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2006;6:906–925. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2006.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chatterjee D, Dasgupta S. J Photochem Photobiol C: Photochem Rev. 2005;6:186–205. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paunesku T, Rajh T, Wiederrecht G, Maser J, Vogt S, Stojicevic N, Protic M, Lai B, Oryhon J, Thurnauer M, Woloschak GE. Nature Mater. 2003;2:343–346. doi: 10.1038/nmat875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paunesku T, Vogt S, Lai B, Maser J, Stojicevic N, Thurn KT, Osipo C, Liu H, Legnini D, Wang Z, Lee C, Woloschak GE. Nano Lett. 2007;7:596–601. doi: 10.1021/nl0624723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Gratzel M. Nature. 2001;414:338–344. doi: 10.1038/35104607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gratzel M. J Photochem Photobiol A: Photochem. 2004;164:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zukalova M, Zukal A, Kava L, Nazeeruddin MK, Liska P, Gratzel M. Nano Lett. 2005;5:1789–1792. doi: 10.1021/nl051401l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niemeyer CM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:4128–4158. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011119)40:22<4128::AID-ANIE4128>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun E, Eichen Y, Sivan U, Ben-Yoseph G. Nature. 1998;391:775–778. doi: 10.1038/35826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Torimoto T, Yanashita M, Kuwabata S, Sakata T, Meri H, Yoneyama H. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:8799–8803. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang G, Murray RW. Nano Lett. 2004;4:95–101. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wu A, Cheng W, Li Z, Jiang J, Wang E. Talanta. 2006;68:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL, Mucic RC, Storhoff JJ. Nature. 1996;382:607–609. doi: 10.1038/382607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Alivisatos AP, Johnsson KP, Peng X, Wilson TE, Loweth CJ, Jr, Bruchez MP, Schultz PG. Nature. 1996;382:609–611. doi: 10.1038/382609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boncheva M, Scheibler L, Lincoln P, Vogel H, Akerman B. Langmuir. 1999;15:4317–4320. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajh T, Chen LX, Lukas K, Liu T, Thurnauer MC, Tiede DM. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:10543–10552. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tom S, Henricksen LA, Bambara RA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(14):10498–10505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Zobel CR, Beer M. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1961;11:336–346. doi: 10.1083/jcb.10.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huxley HE, Zubay G. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1961;11:273–296. doi: 10.1083/jcb.11.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strausbauch P, Roberson L, Sehgal N. J Electron Microsc Tech. 1985;2:261–262. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Hansma HG, Revenko I, Kim K, Laney DE. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:713–720. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.4.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu A, Yu L, Li Z, Yang H, Wang E. Anal Biochem. 2004;325:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Niemeyer CM, Ceyhan B, Gao S, Chi LF, Peschel S, Simon U. ChemPhysChem. 2001;2:384–388. doi: 10.1002/1439-7641(20010618)2:6<384::AID-CPHC384>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao YW, Jin R, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7961–7962. doi: 10.1021/ja011342n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Celis JE, Celis A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82(10):3262–3266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nakayasu H, Berezney R. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Somanathan S, Suchyna TM, Siegel AJ, Berezney R. J Cellular Biochem. 2001;81:56–67. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(20010401)81:1<56::aid-jcb1023>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu C, Xu K, Gu H, Zheng R, Liu H, Zhang X, Guo Z, Xu B. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9938–9939. doi: 10.1021/ja0464802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Thurn KT, Brown EMB, Wu A, Vogt S, Lai B, Maser J, Paunesku T, Woloschak GE. Nanoscale Research Letters. 2007;2:430–441. doi: 10.1007/s11671-007-9081-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Paunesku T, Vogt S, Maser J, Lai B, Woloschak GE. J Cellular Biochem. 2006;99:1489–1502. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Podust VN, Chang LS, Ott R, Dianov GL, Fanning E. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(48):31992–31999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Paunesku T, Mittal S, Protic M, Oryhon J, Korolev SV, Joachimiak A, Woloschak GE. Int J Radiat Biol. 2001;77(10):1007–1021. doi: 10.1080/09553000110069335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Maga G, Hubscher U. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 15):3051–3060. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Endres P, Paunesku T, Vogt S, Meade T, Woloschak GE. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(51):15760–15761. doi: 10.1021/ja0772389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]