Abstract

Tumor secreted proteins/peptides (tumor secretome) act as mediators of tumor-host communication in the tumor microenvironment. Therefore, development of anti-cancer drugs targeting secretome may effectively control tumor progression. Novel techniques including a capillary ultrafiltration (CUF) probe and a dermis-based cell-trapped system (DBCTS) linked to a tissue chamber were utilized to sample in vivo secretome from tumor masses and microenvironments. The CUF probe and tissue chamber were evaluated in the context of in vivo secretome sampling. Both techniques have been successfully integrated with mass spectrometry for secretome identification. A secretome containing multiple proteins and peptides can be analyzed by NanoLC-LTQ mass spectrometry, which is specially suited to identifying proteins in a complex mixture. In the future, the establishment of comprehensive proteomes of various host and tumor cells, as well as plasma will help in distinguishing the cellular sources of secretome. Many detection methods have been patented regarding probes and peptide used for identification of tumors.

Keywords: Tumor secretion, ultrafiltration, secretome, drugs, mass spectrometry, tissue chamber

Introduction

Secreted proteins and peptides (secretome) including cytokines and growth factors involved in cell-cell interaction play a central role in host defense system against tumor formation [1]. Secretome is a rich source of new drug and vaccine targets, and is becoming a main focus of new medicine discovery programs throughout the industry [2]. Although many anti-cancer drugs targeting secreted proteins have been revealed [3, 4], comprehensive secretomes for various cancers are still necessary for the future development of the most potent and cancer cell-specific drugs. Identification of proteins and/or peptides released in the medium of in vitro tumor cell culture has been widely used to characterize the tumor secretome. However, the secretory pattern in vitro does not always match well with the in vivo secretome. We recently developed two novel technologies to harvest tumor secretome in vivo [5-8]. First, a technology utilizing capillary ultrafiltration (CUF) probes allows capturing of secretome in vivo from various animal tissues at different time points [5-7, 9]. The CUF probe provides a unique device for collecting secretome from various sizes of tumors. Second, we employed a de-epidermized dermis as a biological scaffold to trap tumor cells in a three-dimensional (3D) skin equivalent [10, 11]. The dermis-based cell-trapped system (DBCTS) created a tumor microenvironment by inserting a tumor cell-trapped skin equivalent into a perforated tissue chamber. Tissue chamber fluid containing tumor secretome was drawn by pecutaneous aspiration. Both technologies conferred modalities for localized sampling of secretome in the tumor microenvironment and thus provided quantitation of local concentrations of secretome that cannot be achieved by sampling circulating blood. In addition, both technologies have been efficiently integrated with mass spectrometry to identify a mixture of multiple proteins and peptides in tumor secretome [5,8,12, 13].

Tumor Secretome

Cells in a tumor microenvironment are composed of the proliferative tumor cells as well as many immune effector cells including T cells, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, eosinophils and neutrophils. Thus, there is a dynamic interaction within the tumor microenvironment where host and tumor cells compete against each other for survival [14]. The invention patented by Hirofumi, et al. provide method of inhibiting production of BCL2 gene product which allow treatment or prevention of melanoma [15]. Conjugates are patented by Haval, et al., which are useful for generating or enhancing an immune response against the antigen or infectious agent [16]. Although many theories have been proposed, the mechanisms underlying the dynamic communication between tumor and host cells are not fully understood. The decrease of surface antigens such as major histocompatibility (MHC) class I from tumors may explain some of the failure of immunosurveillance, resulting in tumor progression [17]. Loss of surface antigens, however, does not explain the survival of all tumors. It has been reported that sera of cancer patients were full of an impressive variety of immunosuppressive proteins, indicating that many immunosuppressive substances may be secreted from either tumor or host cells [18]. These secreted substances within tumor microenvironments can be defined as tumor secretome. It has been shown that human cancer cell lines release soluble factors that alter the maturation of dendritic cells, providing one potential mechanism for the escape of tumors from the host defense system [19]. One of these soluble factors was identified as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [19]. In stem cell research, the existence of stem cells in tumor cell populations also provides an alternative explanation for tumor progression. Abundant evidence indicates that cancers contain their own stem cells that are distinguished by their self-renewing capacity and differentiation ability [20]. Cancer stem cells might play an influential role in tumor initiation and progression. Recent studies using stem cell-like tumor cells indicated that cancer stem cells express secreted angiogenic factors such as VEGF that prompote tumor angiogenesis and growth [21]. Therefore, dysregulation of cancer stem cell secretion may be a crucial step to suppress the development of cancer. AK022567, recently patented by Yasufumi, et al., is useful as an angiogenesis inhibitor. These polypeptides and antibodies against the polypeptides are useful for screening of a candidate compound as an angiogenesis inhibitor or promoter [22]. Stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) has been applied to compare the secretome from pancreatic cancer-derived cells with that from non-neoplastic pancreatic ductal cells [23]. More than 140 differentially secreted proteins have been identified as members of tumor secretome, several of which were consistent with previous report [23]. These secreted proteins in pancreatic cancer included cathepsin D, macrophage colony stimulation factor, fibronectin receptor, profilin I and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP-7). In addition, the thymosin family of peptides (secreted in the tumor masses), annexin II (over-expressed in several tumors), and defensins (secreted by host cells such as neutrophils) may also fall into this category as members of tumor secretome [18, 24]. Of particular interest, a recent review suggests that CXCL12 chemokine can be secreted by host cells to attract cancer cells, acting through its cognate receptor, CXCR4, which is expressed in tumor cells [1]. Many cytokines such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and interleukin (IL)-10 secreted by either the tumor, immunocompetent cells, or both, can exert immunosuppressive effects. There is also evidence that other cytokines, including circulating IL-6, could contribute to peripheral T cell dysfunction, enabling tumor cells to escape immune surveillance by preventing anti-tumor immune responses [18, 25]. Clinically, elevated serum concentrations and increased expression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α are present in various pre-neoplastic and malignant diseases, compared with serum and tissue from healthy individuals [26]. Increasing evidence suggests that TNF-α may regulate many critical processes involved in tumor progression [27]. TNF-α-released from cancer and host cells can trigger a range of mediators including matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) and cell adhesion molecules [28]. Recent studies have shown that many of the processes involved in tumor progression are sustained by chronic TNF-α production and that inhibition of this key pro-inflammatory molecule may lead to novel cancer treatments [29]. Overall, the secretome released from the tumors and/or host cells may play a vital role in tumor growth. Development of anti-cancer drugs targeting tumor secretome may provide a valuable modality to combat the tumor progression.

Anti-Cancer Drugs Targeting Cytokines and Growth Factors

A very successful story of secretome targeting in a clinical disease is the development of anti-TNF therapy for rheumatoid arthritis [30, 31]. It is based on a well founded rationale that TNF is a central player in the cytokine cascade in the rheumatoid joint from the initial discovery of a “soup” of secreted cytokines in the synovial fluid to later animal and human studies. There are 3 immunoglobin-based drugs that can inhibit TNF activities are approved by US Food and Drug administration (FDA): Infliximab (Remicade), Adalimumab (Humira) and Etanercept (Enbrel). The former two antibodies directly bind to TNF and the latter one targets its receptor. When the treatment was extended to other autoimmune or inflammatory diseases, the results were seldom encouraging [32, 33]. Therefore, it might be beneficial to develop a more comprehensive profile of the secretome in those diseases that failed to response.

The signaling of TNF in the development of cancer is intriguing despite controversies regarding anti-TNF treatment for cancer. While clinical trials have been conducted to target TNF for its tumor promoting effect in the cancer microenvironment [34], data compiled from multiple clinical trials for rheumatoid arthritis have shown a dose-dependent increased risk of malignancy in patients with anti-TNF treatment [35]. Nevertheless, targeting other secreted growth factors has been successfully documented for cancer treatment. These include a long list of pro- and anti- angiogenic factors [36]. For example, bevacizumab (Avastin), a humanized monoclonal antibody binds to VEGF with high specificity, thereby blocking angiogenesis. It was approved by FDA to treat colon cancer in 2004 and lung cancer in 2006 [37]. Recently, it has been found that stem cell-like glioma cells (SCLGC) were able to release VEGF [21]. SCLGC-conditioned medium considerably enhanced endothelial cell migration and blood vessel formation. Importantly, the pro-angiogenic effects of SCLGC on endothelial cells were specifically blocked by the anti-VEGF neutralizing antibody bevacizumab, suggesting that secreted VEGF in conditioned medium played a key role in SCLGC-induced angiogenesis. Additionally, bevacizumab suppressed growth of xenografts derived from SCLGC, indicating that bevacizumab is a potent antiangiogenic medicine, and that targeting pro-angiogenic factors such as VEGF from stem cell-like tumor populations may be crucial for cancer therapy. A new invention provides FGFR fusion proteins that are used to treat proliferation disorders including cancers and disorders of angiogenesis [38].

There are many hurdles in the way of going a comprehensive profile of tumor secretome. Conventional methods probed the tumor secretome by identifying released proteins/peptides from the medium of in vitro tumor cell culture and then analyzing their properties in vivo. However, the data from the in vitro experiments rarely fitt well with in vivo animal models. Spinning down the homogenized tumor masses and then collecting supernatants is one alternative way to obtain tumor secretome. However, tumor secretome collected from homogenized tumor masses are frequently contaminated by other proteins/peptides, which leak from the damaged tumor tissues. In addition, it normally requires sacrificing many animals to obtain a dynamic secretion pattern. Ultrafiltration using a permeable membrane is a method that has been applied for dynamically sampling in vivo secretome [37]. Like microdialysis, ultrafiltration sampling generally collected a small volume of sample unless long-term collection was performed. Implantation of a perforated tissue chamber into living animals is a method to harvest body fluid that contains ample secretome. Most importantly, an implanted tissue chamber was capable of collecting a larger volume of samples for further analysis.

In Vivo Microdialysis Sampling

Microdialysis sampling creates a concentration gradient to drive the passive diffusion of substances across a semi-permeable hollow membrane [39]. Although microdialysis sampling has difficulty in detecting peptides and proteins, it is a useful means to filter macromolecules out of the extracellular fluids. Peptide and protein sampling using the microdialysis sampling approach poses many mass transfer challenges. The primary challenges associated with the in vivo collection of proteins using microdialysis sampling include the greatly reduced recovery caused by lower analyte diffusivity and large volume needed for analysis via classic immunoassay detection [40]. To efficiently capture cytokines and peptides, improvements have been made by creating different affinity-reagents (antibody- and heparin-immobilized beads) that are amenable with microdialysis sampling procedures [39]. Furthermore, microdialysis sampling has been currently upgraded for the collection of in vivo cytokines and growth factors. Cytokines (approximately 8–80 kDa) with picomolar concentrations are a group of secreted proteins that are usually undetectable in extracellular fluids or tissues under normal situations. Most of the cytokines were produced only when cells were exposed to biological stimulation. Thus, elevated production of cytokines is recognized as a sign of activation of cytokine pathways associated with inflammation or disease initiation. Due to high specificity and sensitivity, an enzyme linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA) is the most broadly used method to quantify cytokines in biological matrices, although a typical ELISA can only detect one cytokine at a time and requires at least 100 μl sample volumes. Recently, cytokine antibody arrays requiring a smaller volume of sample have been developed [41]. It has been highlighted that microdialysis sampling possesses many advantages for collecting cytokines from local microenvironment [42]. It has been recently reported that the concentration of IL-6 in the interstitial fluid was 100-fold higher than in the plasma [43]. In combination with microspheres, cytokines including TNF-α, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1 and IL-6 became detectable in freely-moving animals [39, 41]. Evidence has shown that microdialysis was able to efficiently sample various growth factors in breast cancer [44], and cytokines (IL-1beta and IL-6) in the interstitial fluid of the brain of patients with severe head injuries [45]. Recently, scientists in Stenken's group have embarked on using mass spectrometry to probe for the presence of matrix metalloproteinases [40]. On-line coupling of in vivo microdialysis with mass spectrometry has been established [40]. Deterding and coworkers used a miniature hollow-fiber microdialysis device to optimize the online desalting of small-volume samples. For peptide detection online, the device was directly linked to a dynamic nanoelectrospray ionization assembly interfaced with an ion trap mass spectrometer [46]. Microdialysis sampling has several technical limitations. First, fluids collected by microdialysis do not directly reflect the tissue concentration since the injected perfusion fluids diluted the samples. Furthermore, sampling of proteins with larger molecular weights remains a hard task since microdialysis sampling is mainly reliant on diffusion of the analyte into the dialysate.

In Vivo Ultrafiltration Sampling of Tumor Secretome

Unlike microdialysis, sample concentration in the ultrafiltration-collected fluids directly reflects the tissue concentration since substances cross the ultrafiltration membrane by convection together with the fluids in which are dissolved [47]. The ultrafiltration sampling technique applies a vacuum to semi-permeable membranes to extract fluids containing secretome from the extracellular space [48-51]. In comparison with microdialysis, ultrafiltration collects a small volume sample and thus allows samples to be taken more frequently. Furthermore, it is of value for in vivo monitoring because no dilution factor has to be considered [37]. Ultrafiltration sampling was originally employed to monitor the concentrations of ions and glucose in the subcutaneous tissue, blood, saliva, and other biological fluids [37]. Recently, our laboratory combined this technology with mass spectrometry for in vivo detection of peptides and proteins [5-7, 9]. A CUF probe (Fig. 1A) has been newly developed based on ultrafiltration technology. A semi-permeable hollow membrane is positioned at the front of CUF probe and connected to a polytetrafluroethylene (PTFE) tube. The semi-permeable hollow membranes with a range of molecular weight cutoffs (MWCOs) can be made with various surface-charged materials. The probe was connected to a vacutainer to allow negative pressure to drive the ultrafiltration process and collect extracellular fluids. The sampling efficiency of CUF probes has been demonstrated by implanting probes into mice to collect in vivo secretomes from ear skin [7], skin wounds [6], sodium lauryl sulfate-treated skin [9] and solid tumors [5].

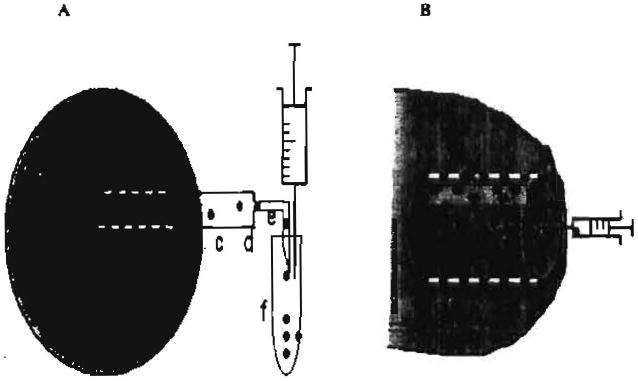

Fig. (1).

Sampling tumor secretome in vivo using a CUF probe or a tissue chamber.

(A) A CUF probe can be introduced into a growing tumor mass in a mouse. The probe dynamically collects the in vivo tumor secretome either released from tumor cells (T) or host cells (H). The collection can be short-term (< 1h) from an anesthetized mouse or long-term (several weeks) from a conscious mouse that wears an elastomer saddles tether attached a balanced level arm for free moving [9]. The probe extracts tumor secretome by using a vacuum applied to a semi-permeable hollow membrane (a). The vacuum can be generated by withdrawing a syringe from the vacutainer. The sampling efficiency of the CUF probe depends on the various pore sizes and surface charges of semi-permeable membranes as well as the nature of proteins/peptides. The probe can be also fabricated to match the various sizes of tumor masses. One end of the semi-permeable hollow membrane fiber is glued with a small, section of fused silica capillary (b) and joined to a PTFE tubing (c), while the other end is completely sealed with epoxy. A sharpened needle (e) is connected to the end of the PTFE ultramicrobore tube (d) and inserted into the vacutainer.

(B) A tissue chamber (internal and external diameters, 1.5 and 3.0 mm, respectively; length, 1 cm) was composed of a closed PTFE teflon cylinder with 12 spaced 0.1 mm holes [8]. A dead de-epidermized dermis was used as a scaffold to grow tumor cells (T) three-dimensionally. The dead dermis was prepared as described [8]. The tumor cell-trapped dermis then was inserted into a tissue chamber. A tissue chamber bearing tumor cell-trapped dermis was subcutaneously implanted into the mice. Seven days post implantation, the tissue chamber was fully integrated with mouse tissues and surrounded with blood vessels (V). Host infiltrated cells (H) were detectable within chamber. Tissue chamber fluid containing secretome was drawn by pecutaneous aspiration. Solid dots: tumor secretome.

A regressive tumor model was employed to evaluate the effectiveness of CUF probe sampling of in vivo secretome. C3H/HeN mice were injected with ultraviolet (UV)-induced fibrosarcoma UV-2240 cell lines. The injection induced a significant tumor for the first two weeks. However, the tumor regressed between the second and third week, and completely disappeared by four weeks post- injection. CUF probes were implanted into tumor masses at progressive and regressive stages [5, 52] and collected in vivo tumor secretome for 6 h. During sample collection, the semi-permeable membrane in the front end of CUF probe was entirely enclosed by a tumor mass. A multiple protein/peptide mixture in the collected secretome was cleaved with trypsin. Although used extensively in proteomics, two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE) gels are insensitive to low abundance and/or secretory proteins/peptides. Thus, the complex mixture of tryptic digests was directly subjected to matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) and quadrupole time of flight (Q-TOF) MS/MS for protein identification and peptide sequencing. Comparison of the MALDI-TOF MS spectra of fluids from tumor masses at progressive and regressive, we found at least five peptide peaks (1087.4, 1436.6, 1885.8, 1981.7, and 2048.2 m/z) that were exclusively present in tumors at the progressive stage [5]. At least twelve peptide peaks (1088.6, 1029.5, 1171.6, 1198.7, 1340.5, 1469.7, 1961.0, 2138.3, 2199.0, 2746.4, and 3240.7 m/z) were detected exclusively in tumors at the regressive stage. Tryptic peptides from both tumor groups were subjected to Q-TOF MS/MS for amino acid sequencing in order to identify the observed peptide peaks shown in the MALDI-TOF MS spectra. After electro-spraying the tryptic peptides of fluids directly into the source of the Q-TOF MS/MS, ten in vivo tumor secreted proteins were sequenced. We identified five secreted proteins (cyclophilin-A, S100A4, profilin-1, thymosin beta 4 and 10) from a progressive tumor mass and five secreted proteins (apolipoprotein A-1, apolipoprotein C-1, fetuin-A, alpha-1 antitrypsin 1-6, and contrapsin) from a regressive tumor mass. These identified proteins have been reported to be highly associated with tumor formation. The latest invention relates to methods for screening for proteases and substrates susceptible to cleavage by proteases. This invention allow for the screening of proteases in an environment where the proteases are normally present, in particular within a living organism [53]. Methods using the polypeptides to identify compounds that modulate protease activity are patent by Edwin, et al. The polypeptides also serve as tumor markers [54]. Huinink and coworkers developed an ultrafiltration collection device (UCD) for continuous sampling [13]. The UCD consists of a hollow fiber, a coil, and a flow creator. The use of hollow fibers made from various materials results in different adsorption of proteins and/or peptides. The UCD was incorporated with surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (SELDI-TOF-MS) for protein profiling. Although SELDI-TOF-MS linked to UCD was successfully used for protein detection, proteins in the UCD-collected samples could not be sequenced by SELDI-TOF-MS. We did not identify any cytokines in the tumor secretome by using the CUF probes in conjunction with mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometers may be not sensitive enough to detect cytokines that are typically present at relatively low concentrations in the pg/ml range. Although ELISA may be the best way to measure cytokines [41], the technique failed to detect the unknown proteins and required a larger volume sample. Recently, we developed a new technology by inserting a tumor cell-trapped skin equivalent into a perforated tissue chamber to mimic a tumor microenvironment (Fig. 1B) [8]. The technology enabled us to harvest a larger sample volume for cytokine detection.

Tissue Chamber

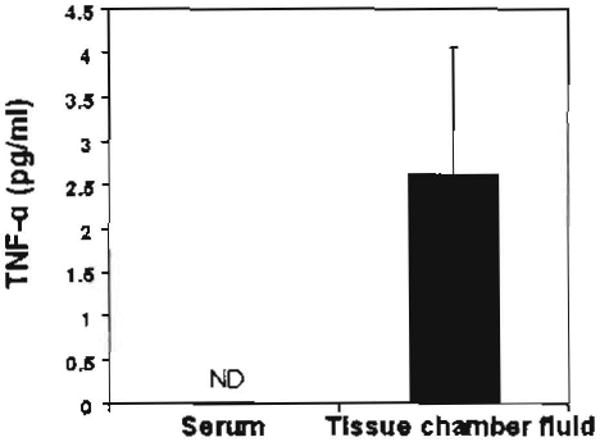

Originally, the tissue chamber was used as an in vivo model to investigate various aspects of prosthetic infections (e.g., bacterial adherence, host response and defense to pathogens) and to determine the efficacy of antimicrobial therapy [55]. In this model, a perforated polymer cylinder was subcutaneously implanted into guinea pigs, rats, or mice. The implanted chamber was surrounded with peripheral tissues to allow for accumulating non-hemorrhagic interstitial fluid. The tissue chamber fluid contained various infiltrated inflammatory cells such as macrophages, lymphocytes, and polymorphonuclear leuko-cytes [56]. As a result, the model has been widely used to assess the local inflammatory responses to various physiological stimulations [57]. We used this model to explore the host response to tumorigenesis. We first examined if the tissue chamber was capable of collecting in vivo pro-inflammatory cytokines. A modified tissue chamber was fabricated by using a perforated PTFE teflon cylinder with 12 regularly spaced 0.1 mm holes. To ensure the chamber was fully integrated into the subcutaneous environment, the chamber was maintained in the ICR mice for 7 days after subcu-taneous implantation. Tissue chamber fluid and serum were collected for cytokine detection by an ELISA assay. TNF-α was abundantly detected in the tissue chamber fluid (2.6 ± 1.4 pg/ml), but undetectable in the serum (Fig. 2), indicating that a large volume sample collected by tissue chamber enabled detection of cytokines by ELISA. More importantly, the data also demonstrated the ability of the tissue chamber to entrap the secretome, which thus became detectable before being diluted into circulating systems.

Fig. (2).

Detection of TNF-α cytokine In the tissue chamber fluid.

An empty tissue chamber lacking tumor cells was subcutaneously implanted into ICR mice. The tissue chamber fluid was collected seven days after implantation. The serum was collected from mouse eyes at the same time. The concentration of TNF-α was determined with an ELISA kit (R & D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN). Error bars represented mean ± SE of five separate experiments. ND: undetected.

The tissue chamber model has been applied for establishing a tumor microenvironment. A newly designed technology called DBCTS was employed to grow the regressive (UV-2240) and progressive (UV-2237) tumor cells in a 3D manner [8]. A tissue chamber inserted with a tumor cell-trapped dermis was implanted into C3H/HeN mice. One day after insertion of a cell-trapped dermis, infiltrated host cells including macrophages, neutrophils, NK and T cells were found in tissue chamber fluids, suggesting that host cells were recruited into tissue chamber fluids to react with tumor cells within the tissue chambers. The in vivo secretome created by host-tumor interaction was characterized from samples collected from tissue chamber fluids via isotope-coded protein label (ICPL) labeling mass spectrometric analysis. Hundreds of proteins comprising in vivo secretome have been identified and quantified via ICPL linked to high throughput NanoLC-LTQ MS analysis. More intriguingly, three secreted proteins, myeloperoxidase, alpha-2-macro-globulin and a vitamin D-binding protein, have different abundances within the in vivo secretome in response to progressive and regressive tumor cells.

Summary and Future Developments

A tumor mass secretome contains multiple proteins/peptides secreted either from tumor or host cells. Unraveling tumor secretome composition will facilitate the development of anti-cancer drugs specifically targeting secreted proteins/peptides. The methodology of in vivo sampling with ultrafiltration and microdialysis has been compared [37]. Here, we briefly summarized the features of sampling with CUF probes and tissue chambers (Table 1). CUF probe sampling driven by vacuum provides a promising method for obtaining in vivo, dynamic, and relatively pure tumor secretome. The CUF probe can perform localized-sampling of secretome directly from the tumor microenvironment. Mass spectrometry integrated with CUF probe sampling enables secretome identification. Semi-permeable hollow membranes with various MWCOs at the front of CUF probes selectively filter out proteins with larger molecular weights, decreasing the complexity of collected samples, and thus benefiting protein identification by mass spectrometry. Although it has been demonstrated that the semi-permeable hollow membrane can serve as a bioreactor to grow the tumor cells [58], using it to create a tumor microenvironment had not been established yet. A perforated tissue chamber integrated with DBCTS has been successfully applied to mimic a tumor microenvironment [8]. The tumor cells within a chamber can cause the infiltration of host cells. A larger volume of tissue chamber fluid obtained by pecutaneous aspiration is beneficial for cytokine detection. Secretome in tissue chamber fluid was detectable by high throughput mass spectrometry analysis. Proteins in the fluids collected either from CUF probes or tissue chambers are a complex mixture composed of secreted proteins, cell matrix proteins as well as proteins from interstitial fluid or plasma. In the future, the establishment of comprehensive proteomes of various host cells, tumor cells and plasma will be of assistance in tracking the cell sources of secretomes.

Table 1.

Comparison of CUF Probe and Tissue Chamber Sampling

| CUF probe | Tissue chamber | |

|---|---|---|

| Key component | Semi-permeable membrane | Perforated polymer cylinder |

| Tumor cell growth | Yes [58] | Yes [8] |

| Mimic tumor microenvironment | Not established | Yes |

| In vivo secretome sampling | Yes, a small volume | Yes, a large volume |

| Collection | Vacuum | Pecutaneous aspiration |

| Host cell infiltration | No | Yes |

| Secretome identification | Mass spectrometry and others | Mass spectrometry and others |

| Secretome purity | Relatively pure | Not pure |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants [R01-AI067395-01, R21-R022754-01, R21-158002-01 (C.-M. H.) and P30-AI36214-12S1 (Y.-T. L.)]. We thank Daniel T. Macleod for critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CUF

Capillary ultrafiltration

- DBCTS

Dermis-based cell-trapped system

- 2-DE

Two-dimensional electrophoresis

- ELISA

Enzyme linked immunoabsorbent assay

- FDA

Food and Drug administration

- ICPL

Isotope-coded protein label

- IGFBP-7

Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7

- IL

Interleukin

- MALDI-TOF MS

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight MS

- MCP

Monocyte chemoattractant protein

- MHC

Major histocompatibility

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinases

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- MWCOs

Molecular weight cutoffs

- NK

Natural killer

- NanoLC-TLQ

Nano liquid chromatography linear ion trap

- PTFE

Polytetrafluroethylene

- Q-TOF MS/MS

Quadrupole time of flight MS/MS

- SELDU-TOF-MS

Surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- SCLGC

Stem cell-like glioma cells

- SILAC

Stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture

- TGF

Transforming growth factor

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- UCD

Ultrafiltration collection device

- ND

Undetected

- UV

Ultraviolet

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- 1.Burger JA, Kipps TJ. CXCR4: a key receptor in the crosstalk between tumor cells and their microenvironment. Blood. 2006;107:1761–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonin-Debs AL, Boche I, Gille H, Brinkmann U. Development of secreted proteins as biotherapeutic agents. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:551–8. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shinkaruk S, Bayle M, Lain G, Deleris G. Vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF), an emerging target for cancer chemotherapy. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 2003;3:95–117. doi: 10.2174/1568011033353452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohe Y, Kasai T, Heike Y, Saijo N. [Clinical trial of IL-12 for cancer patients] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1998;25:177–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang CM, Ananthaswamy HN, Barnes S, et al. Mass spectrometric proteomics profiles of in vivo tumor secretomes: capillary ultrafiltration sampling of regressive tumor masses. Proteomics. 2006;6:6107–16. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang CM, Wang CC, Barnes S, Elmets CA. In vivo detection of secreted proteins from wounded skin using capillary ultrafiltration probes and mass spectrometric proteomics. Proteomics. 2006;6:5805–14. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang CM, Wang CC, Kawai M, Barnes S, Elmets CA. In vivo protein sampling using capillary ultrafiltration semi-permeable hollow fiber and protein identification via mass spectrometry-based proteomics. J Chromatogr A. 2006;1109:144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.11.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Y, Elmets CA, Smith JW, et al. Quantitative proteomes and in vivo secretomes of progressive and regressive UV-induced fibrosarcoma tumor cells: Mimicking tumor microenvironment using a dermis-based cell-trapped system linked to tissue chamber. Proteomics. 2007;7:4589–600. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang CM, Wang CC, Kawai M, Barnes S, Elmets CA. Surfactant sodium lauryl sulfate enhances skin vaccination: molecular characterization via a novel technique using ultrafiltration capillaries and mass spectrometric proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:523–32. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500259-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma L, Shi Y, Chen Y, et al. In vitro and in vivo biological performance of collagen-chitosan/silicone membrane bilayer dermal equivalent. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2007;18:2185–91. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hata K. Current issues regarding skin substitutes using living cells as industrial materials. J Artif Organs. 2007;10:129–32. doi: 10.1007/s10047-006-0371-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hathout Y. Approaches to the study of the cell secretome. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2007;4:239–48. doi: 10.1586/14789450.4.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huinink KD, Venema K, Roelofsen H, Korf J. In vitro sampling and storage of proteins with an ultrafiltration collection device (UCD) and analysis with absorbance spectrometry and SELDI-TOF-MS. Analyst. 2005;130:1168–74. doi: 10.1039/b503136b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poggi A, Zocchi MR. Mechanisms of tumor escape: role of tumor microenvironment in inducing apoptosis of cytolytic effector cells. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2006;54:323–33. doi: 10.1007/s00005-006-0038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doi H, Saito S, Murakami K, Kunta Y. 2007 EP071782822. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shirwan H, Elpek K, Yolcu E. 2007 WO07067681. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seliger B. Strategies of tumor immune evasion. BioDrugs. 2005;19:347–54. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200519060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochsenbein AF. Principles of tumor immunosurveillance and implications for immunotherapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9:1043–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabrilovich DI, Chen HL, Girgis KR, et al. Production of vascular endothelial growth factor by human tumors inhibits the functional maturation of dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:1096–103. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang P, Zuo H, Ozaki T, Nakagomi N, Kakudo K. Cancer stem cell hypothesis in thyroid cancer. Pathol Int. 2006;56:485–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bao S, Wu Q, Sathornsurnetee S, et al. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7843–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato Y, Sonoda H, Ohta H. 2007 EP071839669. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gronborg M, Kristiansen TZ, Iwahori A, et al. Biomarker discovery from pancreatic cancer secretome using a differential proteomic approach. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:157–71. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500178-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshimoto T, Yamaai T, Mizukawa N, et al. Different expression patterns of beta-defensins in human squamous cell carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:4629–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawelec G. Tumour escape: antitumour effectors too much of a good thing? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:262–74. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0469-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szlosarek P, Charles KA, Balkwill FR. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha as a tumour promoter. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:745–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guadagni F, Ferroni P, Palmirorta R, et al. Review. TNF/VEGF cross-talk in chronic inflammation-related cancer initiation and progression: an early target in anticancer therapeutic strategy. In Vivo. 2007;21:147–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S, Sandur SK, Pandey MK, Sethi G. Inflammation and cancer how hot is the link? Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1605–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foa R, Massaia M, Cardona S, et al. Production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha by B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells: a possible regulatory role of TNF in the progression of the disease. Blood. 1990;76:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Williams RO, Woody JN, Maini RN. The transfer of a laboratory based hypothesis to a clinically useful therapy: the development of anti-TNF therapy of rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2004;18:59–80. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott DL, Kingsley GH. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:704–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct055183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calabrese L. The yin and yang of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73:251–6. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.73.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luqmani R. Treatment of polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis: are we any further forward? Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:674–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-9-200705010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balkwill F. TNF-alpha in promotion and progression of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:409–16. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, et al. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. Jama. 2006;295:2275–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.19.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Folkman J. Angiogenesis: an organizing principle for drug discovery? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:273–86. doi: 10.1038/nrd2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leegsma-Vogt G, Janle E, Ash SR, Venema K, Korf J. Utilization of in vivo ultrafiltration in biomedical research and clinical applications. Life Sci. 2003;73:2005–18. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00569-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams L, Bosch E, Doberstein S, Hestir K, Hollenbaugh D, Leo E, Qin M, Sadra A, Wong J, Wu G, Zhang H. 2007 WO070141239. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duo J, Fletcher H, Stenken JA. Natural and synthetic affinity agents as microdialysis sampling mass transport enhancers: current progress and future perspectives. Biosens Bioelectron. 2006;22:449–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ao X, Stenken JA. Microdialysis sampling of cytokines. Methods. 2006;38:331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joukhadar C, Muller M. Microdialysis: current applications in clinical pharmacokinetic studies and its potential role in the future. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:895–913. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544090-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Price KE, Vandaveer SS, Lunte CE, Lanve CK. Tissue targeted metabolomics: metabolic profiling by microdialysis sampling and microcoil NMR. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2005;38:904–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sopasakis VR, Sandqvist M, Gustafson B, et al. High local concentrations and effects on differentiation implicate interleukin-6 as a paracrine regulator. Obes Res. 2004;12:454–60. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dabrosin C. Microdialysis - an in vivo technique for studies of growth factors in breast cancer. Front Biosci. 2005;10:1329–35. doi: 10.2741/1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winter CD, Pringle AK, Clough GF, Church MK. Raised parenchymal interleukin-6 levels correlate with improved outcome after traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2004;127:315–20. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deterding LJ, Dix K, Burka LT, Tomer KB. On-line coupling of in vivo microdialysis with tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1992;64:2636–41. doi: 10.1021/ac00045a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Janle EM, Kissinger PT. Microdialysis and ultrafiltration. Adv Food Nutr Res. 1996;40:183–96. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4526(08)60028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Odland RM, Kizziar R, Rheuark D, Simental A. The effect of capillary ultrafiltration probes on skin flap edema. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:210–4. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2003.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Janle EM, Sojka JE. Use of ultrafiltration probes in sheep to collect interstitial fluid for measurement of calcium and magnesium. Conlemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2000;39:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imsilp K, Whittem T, Koritz GD, Zachary JF, Schaeffer DJ. Inflammatory response to intramuscular implantation of polyacrylonitrile ultrafiltration probes in sheep. Vet Res. 2000;31:623–34. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Linhares MC, Kissinger PT. Capillary ultrafiltration: in vivo sampling probes for small molecules. Anal Chem. 1992;64:2831–5. doi: 10.1021/ac00046a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fernandez A, Chen PW, Aggarwal BB, Ananthaswamy HN. Resistance of Ha-ras oncogene-induced progressor tumor variants to tumor necrosis factor and interferon-gamma. Lymphokine Cytokine Res. 1992;11:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Budde P, Schulz-Knappe P. 2007 EP071795606. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Madison EL, Yeh JC. US20077172892. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zimmerli W. Experimental models in the investigation of device-related infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31 D:97–102. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_d.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bergholm AM, Henning C, Holm SE. Static and dynamic properties of tissue cage fluid in rabbits. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1984;3:126–30. doi: 10.1007/BF02014329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dawson J, Rordorf-Adam C, Geiger T, et al. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) production in a mouse tissue chamber model of inflammation. I. Development and initial characterisation of the model. Agents Actions. 1993;38:247–54. doi: 10.1007/BF01976217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gloeckner H, Lemke HD. New miniaturized hollow-fiber bioreactor for in vivo like cell culture, cell expansion, and production of cell-derived products. Biotcehnol Prog. 2001;17:828–31. doi: 10.1021/bp010069q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]