Summary

The periaqueductal gray (PAG) plays an important role in morphine antinociception and tolerance. Co-localization of mu-opioid and NMDA receptors on dendrites in the PAG suggests that glutamate may modulate morphine antinociception. Moreover, the involvement of glutamate in spinally mediated tolerance to morphine suggests that glutamate receptors may contribute to PAG mediated tolerance. These hypotheses were tested by microinjecting glutamate receptor antagonists and morphine into the ventrolateral PAG (vPAG) of the rat. Microinjection of the non-specific glutamate receptor antagonist kynurenic acid or the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 into the vPAG did not affect nociception. However, co-administration of these antagonists with morphine into the vPAG enhanced the acute antinociceptive effects of morphine as measured by a leftward shift in the morphine dose-response curves. Repeated microinjections of morphine into the vPAG caused a rightward shift in the dose response curve for antinociception whether the glutamate receptor antagonists kynurenic acid or MK-801 were co-administered or not. The lack of effect of microinjecting glutamate receptor antagonists into the vPAG indicates that tonic glutamate release in the PAG does not contribute to nociceptive tone. That these antagonists enhance morphine antinociception indicates that endogenous glutamate counteracts the antinociceptive effect of morphine in the vPAG. However, this compensatory glutamate release does not contribute to tolerance to the antinociceptive effects of microinjecting morphine into the vPAG. Previous research showing that glutamate contributes to spinal mechanisms of tolerance indicate that different tolerance mechanisms are engaged in the vPAG and spinal cord.

Keywords: Pain modulation, Opioid, NMDA receptors, Analgesia, Morphine tolerance

1. Introduction

The ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vPAG) is part of a descending system that modulates nociception at the spinal level. Microinjection of morphine into the PAG produces complete and profound antinociception (Jacquet and Lajtha, 1974; Jensen and Yaksh, 1986; Morgan et al., 1998), and blocking opioid receptors in the PAG attenuates the antinociception produced by systemic administration of morphine (Bernal et al., 2007; Lane et al., 2005; Zambotti et al., 1982). Both behavioral and in vitro slice recordings indicate that opioids produce antinociception by inhibiting GABAergic neurons in the PAG (Chieng and Christie, 1994; Depaulis et al., 1987; Moreau and Fields, 1986; Vaughan et al., 1997b).

A number of studies suggest that glutamate may also play a role in opioid antinociception mediated by the PAG. Both excitatory amino acid receptors (Albin et al., 1990; Tolle et al., 1993) and neurons labeled with glutamate (Beitz, 1990; Clements et al., 1987; Ottersen and Storm-Mathisen, 1984) are found in the PAG. Microinjection of excitatory amino acids into the PAG produces antinociception (Behbehani and Fields, 1979; Jacquet, 1988; Jensen and Yaksh, 1992; Morgan et al., 1998; Urca et al., 1980). Presumably, this antinociception is produced by direct activation of PAG output neurons. However, co-localization of mu-opioid and NMDA receptors on the dendrites of PAG neurons (Commons et al., 1999) suggests that glutamate has multiple functions in the PAG. Given that morphine inhibits and glutamate excites PAG neurons (Vaughan and Christie, 1997; Vaughan et al., 1997a), co-localization of these receptors suggests that glutamate may also counteract the antinociceptive effects of morphine—an effect that could contribute to the development of tolerance. Glutamate receptors have been shown to contribute to tolerance to spinal administration of morphine (Trujillo and Akil, 1991; Trujillo and Akil, 1994).

Tolerance to the antinociceptive effects of morphine develops rapidly with repeated microinjection or continuous administration into the ventrolateral PAG (vPAG) (Jacquet and Lajtha, 1976; Lane and Morgan, 2005; Morgan et al., 2006; Siuciak and Advokat, 1987; Tortorici et al., 1999; Tortorici et al., 2001). Moreover, tolerance to the antinociceptive effect of systemic morphine administration is attenuated by blocking opioid action within the vPAG (Lane et al., 2005). Glutamate, NMDA receptors in particular, have been shown to contribute to tolerance to the antinociceptive effects of systemic or intrathecal administration of opioids (Mao, 1999; Trujillo and Akil, 1991). It is not known whether glutamate plays a similar role in tolerance mediated by the vPAG. The present study tested this hypothesis by microinjecting morphine and glutamate receptor antagonists into the vPAG.

2. Results

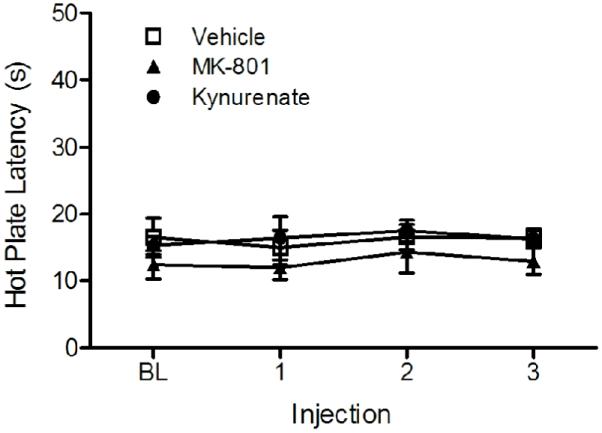

Experiment 1: Microinjection of Glutamate Receptor Antagonists

The objective of this experiment was to determine whether tonically released glutamate in the vPAG modulates nociception. This hypothesis was tested by microinjecting glutamate receptor antagonists into the vPAG. Microinjection of increasing cumulative doses of excitatory amino acid receptor antagonists into the PAG had no effect on hot plate latency. The mean hot plate latency for rats microinjected with kynurenic acid (N = 4) or MK-801 (N = 5) never varied by more than 2 s from the baseline latency despite administration of increasing cumulative doses (Figure 1). Likewise, repeated microinjection of the DMSO vehicle did not alter hot plate latency from the baseline value. The mean hot plate latency for rats injected with kynurenic acid and MK-801 did not differ from vehicle treated rats (F(2,12) = 1.308, n.s.). These data demonstrate that blocking vPAG glutamate receptors does not alter nociceptive tone.

Figure 1.

Microinjection of glutamate receptor antagonists into the vPAG had no effect on nociception. Hot plate latency was consistent and did not differ from vehicle treated control rats despite microinjection of increasing cumulative doses of kynurenic acid (30, 100, & 300 ng/0.4 μl) or MK-801 (30, 100, & 300 ng/0.4 μl) into the vPAG.

Experiment 2: Glutamate Modulation of Morphine Antinociception

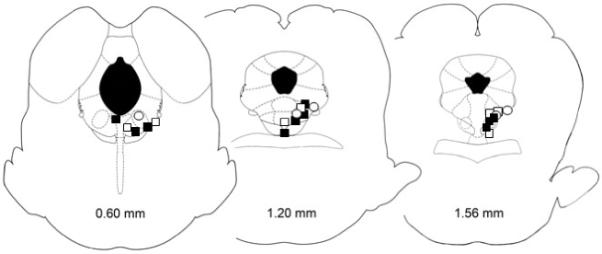

The objective of this experiment was to determine whether glutamate modulates the antinociception produced by microinjecting morphine into the vPAG. The role of glutamate in morphine antinociception was assessed by microinjecting morphine into the vPAG with and without co-administration of kynurenic acid or MK-801. The microinjection sites for this experiment are shown in Figure 2. These microinjections, along with those from the other experiments, were located in or immediately adjacent to the vPAG. Acute microinjection of cumulative half-log doses of morphine into the vPAG (N = 10) produced a dose-dependent increase in hot-plate latency as reported previously (Morgan et al., 2006). Four of the ten rats injected with the highest cumulative dose of morphine (10 μg) reached the cutoff latency of 50 s, and 9 of the 10 had hot plate latencies greater than 31 s.

Figure 2.

Location of microinjection sites in the vPAG (Paxinos and Watson, 2005). This figure shows the injection sites for the acute antinociceptive effects of morphine (filled squares) and morphine paired with kynurenic acid (open squares) or MK-801 (open circles). There was no difference in the location of the microinjections for these three groups. Moreover, these injection sites are representative of the injection sites for the other experiments. Data were used from 119 of 187 injection sites (66%) in or immediately adjacent to the vPAG.

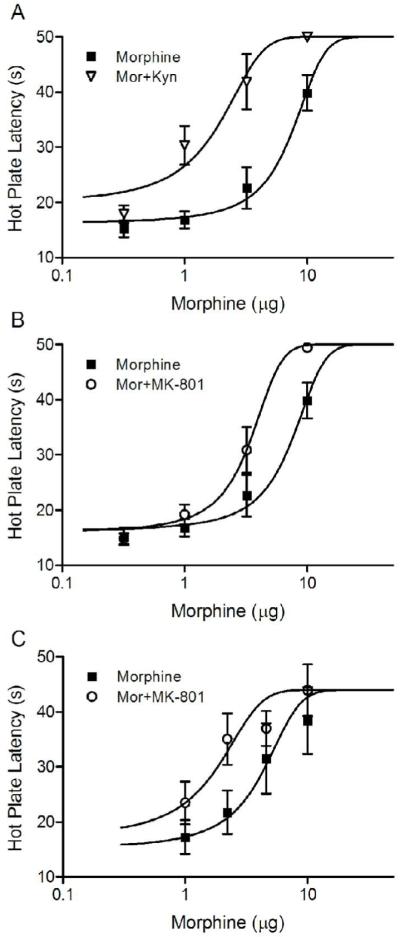

Microinjection of kynurenic acid with morphine into the vPAG (N = 7) enhanced antinociception at every morphine dose from 1 to 10 μg (Figure 3A). All of the rats injected with kynurenic acid reached the cutoff latency of 50 s following microinjection of 10 μg of morphine. This kynurenic acid-induced enhancement resulted in a large leftward shift in the morphine dose-response curve. Microinjection of kynurenic acid caused a significant decrease in the half maximal antinociceptive effect of morphine from a D50 value of 7.3 μg (95% confidence interval = 5.9 - 8.7 μg) to 1.6 μg (1.0 - 2.3 μg) (F(1,76) = 31.03, p < .05).

Figure 3.

Enhancement of morphine antinociception produced by co-administration of glutamate receptor antagonists into the vPAG. Microinjection of kynurenic acid with the first injection of morphine caused a large leftward shift in the morphine dose response curve (A). A similar, although less pronounced leftward shift in the morphine dose response curve was produced by co-administration of the NMDA antagonist MK-801 with the first injection of morphine (B). A change in the MK-801 vehicle from DMSO (B) to saline (C) had no effect. Co-administration of MK-801 in saline with the first dose of morphine into the vPAG caused a comparable leftward shift in the morphine dose response curve (C).

A similar, although less dramatic shift occurred in rats microinjected with MK-801 and morphine into the vPAG (N = 5). Microinjection of MK-801 into the vPAG enhanced the antinociceptive effect of morphine as demonstrated by a leftward shift in the dose response curve (Figure 3B). The D50 for rats injected with MK-801 and morphine was significantly lower (3.3 μg; 2.8 - 3.9 μg) than rats treated with morphine alone (7.3 μg; F (1,69) = 22.37, p < .05).

Given that microinjection of the DMSO vehicle into the vPAG can alter morphine antinociception (Fossum et al., 2008), the MK-801 experiment described above was repeated using saline as the vehicle. In this experiment, third instead of half log doses were used to produce a more accurate D50 value. Microinjection of MK-801 enhanced morphine potency as demonstrated by a change in the D50 for morphine antinociception from 4.0 (CI = 2.3 - 5.7 μg; N = 7) to 1.6 ug (0.9 - 2.2 μg; N = 6) when morphine and MK-801 were administered together (F(1,6) = 6.77, p < .05; Figure 3C). These data show that co-administration of MK-801 and morphine caused a similar leftward shift in the morphine dose-response curve whether mixed in saline or DMSO.

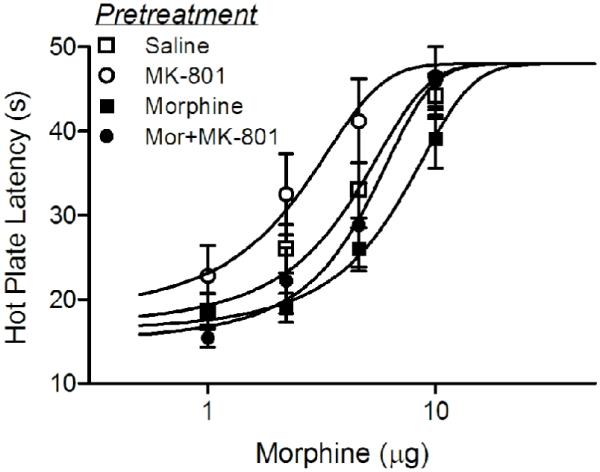

Experiment 3: Glutamate Modulation of Morphine Tolerance

The objective of this experiment was to determine whether glutamate contributes to the development of tolerance to the antinociceptive effect of microinjecting morphine into the vPAG. Although glutamate receptor antagonists enhanced morphine antinociception in Experiment 2, they had no effect on the development of tolerance to morphine. Repeated morphine microinjection into the vPAG (N = 15) caused an increase in the D50 for antinociception compared to saline pretreated rats (N = 16) from 3.5 (2.7 - 4.3 μg) to 5.8 μg (4.6—7.0 μg) as would be expected with the development of tolerance (Figure 4). A similar rightward shift in the morphine dose-response curve occurred in rats pretreated with morphine and MK-801 (D50 = 4.7 μg; 3.4 - 6.0 μg) compared to rats pretreated with MK-801 alone (D50 = 2.1 μg; 1.3 - 2.9 μg). Although these shifts in the morphine dose-response curves are relatively small, they are statistically significant (F(3,162) = 6.20, p < .05) and consistent with a previous study using repeated injections to induce tolerance (Morgan et al., 2006). There was no significant difference in the dose-response curves for rats pretreated with morphine regardless of whether MK-801 was co-administered or not (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Microinjection of MK-801 into the vPAG did not block the development of morphine tolerance. Rats pretreated with twice daily injections of morphine for two days showed a rightward shift in the morphine dose response curve compared to saline pretreated rats. Rats pretreated with MK-801 alone showed a slight leftward shift in the morphine dose-response curve, but rats pretreated with morphine and MK-801 showed a comparable rightward shift in the morphine dose-response curve. That is, repeated microinjections of morphine into the vPAG produced a rightward shift in the morphine dose-response curve relative to the control group for each condition as would be expected with the development of tolerance.

Co-administration of kynurenic acid and morphine into the vPAG also had no effect on the development of tolerance. The D50 for morphine antinociception in rats pretreated with kynurenic acid and morphine on Trials 1 - 4 (4.3 μg; 2.4 - 6.3 μg; N = 7) did not differ from rats pretreated with morphine alone (5.3 μg; 3.4 - 7.1 μg; N = 8; F(1,70) = 0.52, n.s.). Taken together these data indicate that glutamate antagonists have no effect on tolerance to repeated microinjections of morphine into the vPAG.

3. Discussion

The present data show that microinjection of glutamate receptor antagonists into the vPAG enhance the acute antinociceptive effects of morphine. Microinjection of these antagonists alone had no effect on nociception and repeated administration of glutamate receptor antagonists had no effect on the development of morphine tolerance. These data are surprising because glutamate has been shown to contribute to morphine tolerance at the spinal level (Trujillo and Akil, 1991; Trujillo and Akil, 1994).

The lack of a change in nociception following microinjection of glutamate receptor antagonists into the vPAG suggests that either glutamate is not tonically released or tonic release does not modulate nociception. Previous research shows that significant levels of glutamate are recovered with PAG microdialysis during basal conditions (Maione et al., 1999; Maione et al., 2000; Marabese et al., 2005; Renno et al., 1992). At least some of this recovered glutamate is released synaptically because perfusion of the PAG with tetrodotoxin or calcium-free artificial CSF reduces glutamate recovery (Marabese et al., 2005). In addition, bath administration of glutamate receptor antagonists reduces the spontaneous excitatory post-synaptic potentials evident in in vitro slice recordings from the PAG (Vaughan and Christie, 1997). Thus, our data indicate that tonically released glutamate does not alter nociceptive tone.

The finding that glutamate receptor antagonists enhance morphine antinociception contrasts with an earlier study showing that microinjection of NMDA antagonists into the PAG blocks morphine antinociception (Jacquet, 1988). Our enhancement of morphine antinociception is consistent with the enhancement that occurs with systemic administration of morphine and glutamate receptor antagonists (Allen and Dykstra, 2001; Bespalov et al., 1998; Bulka et al., 2002; Fischer et al., 2005; Larcher et al., 1998; Mao et al., 1996; Plesan et al., 1998), although both enhancement and inhibition of morphine antinociception has been reported (Craft and Lee, 2005; Trujillo and Akil, 1994). Variations in test time, morphine dose, nociceptive test, and the particular antagonist used have been shown to influence the direction of glutamate modulation of morphine antinociception following systemic administration (Craft and Lee, 2005). The differences in the nociceptive test (hot plate vs. tail flick and noxious pinch), test time (test 15 vs. 60 min after morphine), or morphine dose (dose response vs. 25 nmol) between the present data and Jacquet’s study could cause this discrepancy. It should be emphasized that the enhancement of morphine antinociception reported here occurred with both the non-specific glutamate receptor antagonist kynurenic acid and the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801. Moreover, this enhancement occurred across a full range of morphine doses and with DMSO and saline as the vehicle.

The enhancement of morphine antinociception produced by microinjection of glutamate receptor antagonists into the vPAG suggests that glutamate release compensates for morphine antinociception. Although the antinociception produced by microinjection of glutamate receptor agonists into the PAG (Behbehani and Fields, 1979; Jacquet, 1988; Jensen and Yaksh, 1992; Urca et al., 1980) appears to contradict the enhanced morphine antinociception produced by glutamate receptor antagonists, the compensatory and antinociceptive effects of glutamate are mediated by different parts of the neural circuit for antinociception. Morphine produces antinociception by inhibiting GABAergic neurons which disinhibit PAG output neurons (Depaulis et al., 1987; Moreau and Fields, 1986; Vaughan et al., 1997b). Direct activation of PAG output neurons whether by disinhibition, electrical stimulation (Mayer et al., 1971; Reynolds, 1969), microinjection of excitatory amino acids (Behbehani and Fields, 1979; Berrino et al., 2001; Jacquet, 1988; Jensen and Yaksh, 1992; Urca et al., 1980), or microinjection of the GABA receptor antagonist bicuculline (Morgan et al., 2003; Morgan and Clayton, 2005) produces antinociception.

Co-localization of NMDA and mu-opioid receptors on dendrites within the PAG (Commons et al., 1999) suggests that the compensatory effects of glutamate are mediated by excitation of the same GABAergic neurons inhibited by morphine. Whether glutamate is released as a compensatory response to morphine administration or in response to noxious stimuli is unclear. A wide range of noxious stimuli (hot plate, formalin injection, or chronic inflammation) has been shown to stimulate the release of glutamate in the PAG (Renno, 1998; Sherman and Gebhart, 1974; Silva et al., 2000). Thus, the repeated hot plate testing associated with the cumulative dose procedure used in the present study may be sufficient to evoke sufficient glutamate release to dampen the antinociceptive effects of morphine. Previous research has shown that repeated nociceptive testing is sufficient to reduce the antinociceptive effects of PAG microinjections of morphine (Lane and Morgan, 2005).

The present data demonstrate that glutamate receptor activation is not necessary for activation of PAG output neurons. Morphine inhibition of GABA release is sufficient to activate these neurons. These data contrast with previous data examining the pharmacology of pain modulation in the rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM). Activation of a class of RVM neurons known as off-cells (Fields et al., 1983) produces antinociception (Heinricher et al., 1994; Morgan et al., 1992). Microinjection of NMDA receptor antagonists into the RVM blocks both the off-cell activation and antinociception produced by morphine administration (Heinricher et al., 1999; Heinricher et al., 2001). Thus, even though the antinociception produced from the PAG is mediated by the RVM (Heinricher et al., 1992; Morgan et al., 1992; Sandkuhler and Gebhart, 1984), glutamate does not contribute to nociceptive modulation in the same manner in the PAG and RVM.

The lack of involvement of vPAG glutamate receptors in tolerance to the antinociceptive effect of morphine is surprising. Glutamate receptor antagonists have been shown to attenuate the development of tolerance to systemic or spinal administration of morphine (Mao, 1999; Trujillo and Akil, 1991). Given that the vPAG plays a key role in tolerance to the antinociceptive effect of systemically administered morphine (Lane et al., 2005), we expected glutamate to contribute to tolerance mediated by the vPAG. Moreover, the enhanced antinociception following microinjection of acute glutamate receptor antagonists with morphine would be expected to enhance the development of tolerance. However, the present data show that blocking NMDA receptors by co-administering MK-801 (or kynurenic acid) with repeated microinjections of morphine into the vPAG did not disrupt the development of tolerance. These data are consistent with a recent report showing that chronic morphine administration in mice did not alter the expression of NMDA receptors in the PAG (Kozela and Popik, 2007).

These data suggest that tolerance is mediated by different mechanism in the vPAG and spinal cord. In contrast to the present data, morphine tolerance mediated by the spinal cord is disrupted by co-administration of NMDA receptor antagonists (Trujillo and Akil, 1991; Trujillo and Akil, 1994). Another difference is that tolerance develops to repeated administration of the mu-opioid receptor agonist DAMGO when injected into the vPAG (Meyer et al., 2007), but not when injected intrathecally (He et al., 2002). In fact, intrathecal administration of DAMGO has been reported to attenuate tolerance to spinally administered morphine (He et al., 2002). Other differences in the mechanisms underlying tolerance are sure to be revealed as research at these two sites progress. Recent data suggest that enhancement of the sensitivity of mu-opioid receptors (Ingram et al., 2008), possibly mediated by upregulation of adenylyl cyclase (Ingram et al., 1998) may underlie tolerance to morphine in the vPAG. Current studies testing this hypothesis are underway.

4. Experimental Procedure

Subjects

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (240-390 g) were anesthetized with equithesin (3 mL/kg, i.p.) and implanted with a guide cannula (23 gauge; 9 mm long) aimed at the vlPAG using stereotaxic techniques (AP: +1.7 mm, ML: +0.6 mm, DV: -4.6 mm from lambda). The guide cannula was attached to two screws in the skull by dental cement. A stylet was inserted to plug the guide cannula and the rat was treated prophylactically with the antibiotic cefazolin (15 mg/0.15 ml, i.m.). Rats were maintained under a heat lamp until awake.

Following surgery, rats were housed individually in a room maintained on a reverse light/dark schedule (lights off at 7:00 AM). Food and water were available at all times except during testing. Rats were handled daily before and after surgery. Behavioral testing was initiated at least 7 days following surgery. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Efforts were made to minimize the number and potential suffering of the rats.

Behavioral Assessment

Nociception was assessed using the hot plate test. The hot plate test consisted of measuring the latency for a rat to lick a hind paw when placed on a hot plate (52.5°C). The rat was removed from the hot plate if no response occurred within 50 s.

Microinjections

Drugs were administered through a 31-gauge injection cannula inserted into and extending 2 mm beyond the tip of the guide cannula. Before the start of the experiment, rats received a sham injection in which the injector was inserted through the guide cannula, but no drug was administered. This procedure reduces confounds due to mechanical stimulation of neurons during testing and habituates rats to the microinjection procedure. Microinjections were administered in a volume of 0.4 μl at a rate of 0.1 μl/10 s while the rat was gently restrained by hand. The injection cannula remained in place an additional 20 s to minimize backflow of the drug up the cannula track. Following the injection, the stylet was replaced and the rat was returned to its home cage.

A cumulative dose procedure was used to assess the antinociceptive potency of morphine sulfate (a gift from National Institutes of Health). This procedure consists of microinjecting increasing cumulative doses of morphine (1.0, 1.2, 2.4, & 5.4 μg/0.4 μl) into the vPAG at 20 min intervals resulting in third log doses of 1, 2.2, 4.6, & 10 μg/0.4 μl (Morgan et al., 2006). Nociception was assessed 15 min after each injection. Half log doses (0.32, 1, 3.2, & 10 μg/0.4 μl) were used in the first part of Experiment 2 to guarantee the full antinociceptive range was covered. Subsequent experiments used third log doses because increasing the number of injections defining the slope of the curve produces a more accurate measure of potency, and a wide range of doses was not needed because the effective dose range was determined in the first part of Experiment 2.

Experiment 1: Microinjection of Glutamate Antagonists

Increasing cumulative half log doses of the non-selective excitatory amino acid antagonist kynurenic acid (30, 100, & 300 ng/0.4 μl) and the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 (30, 100, & 300 ng/0.4 μl) were microinjected into the PAG at 20 min intervals in the absence of morphine. Both drugs were mixed in a 20% DMSO/80% saline solution. Nociception was assessed using the hot plate test 15 min after each injection.

Experiment 2: Glutamate Modulation of Morphine Antinociception

Kynurenic acid (100 ng) or MK-801 (300 ng) were microinjected with the lowest dose of morphine into the PAG followed by increasing cumulative doses of morphine. This drug cocktail and the morphine alone control were mixed in 20%DMSO/80% saline. Subsequent doses of morphine were mixed in saline and injected in the absence of kynurenic acid or MK-801.

Given that using DMSO as the vehicle can alter the antinociceptive effect of microinjecting morphine into the vPAG (Fossum et al., 2008), this experiment was repeated with MK-801 dissolved in saline to make sure any changes in morphine antinociception were caused by MK-801 and not DMSO. Kynurenic acid was not used in this part of the experiment because it cannot be dissolved in saline. MK-801 (300 ng) was combined with the lowest dose of morphine followed by increasing cumulative doses of morphine every 20 min.

Experiment 3: Glutamate Modulation of Morphine Tolerance

MK-801 (300 ng) was microinjected with or without morphine into the vPAG twice a day for two consecutive days. Control groups received repeated microinjections of saline or morphine without MK-801 in the solution. Nociception was assessed following the first, but not subsequent injections to minimize changes in hot plate latency produced by repeated testing (Lane and Morgan, 2005). Tolerance was assessed on Day 3 by microinjecting cumulative doses of morphine into the vPAG as described previously. The effect of co-administration of kynurenic acid with and without morphine on tolerance was assessed also. The only difference between these experiments was that a 20% DMSO solution was used as the vehicle for kynurenic acid.

Histology

Rats were sacrificed following testing by administering a lethal dose of Halothane. The microinjection site was marked by injecting Cresyl Violet (0.2 μl) into the vPAG. The brain was removed and placed in formalin (10%). At least 2 days later the brain was sectioned coronally (100 μm) and the location of the injection site identified (Paxinos and Watson, 2005).

Data Analysis

Morphine dose response curves and the half maximal dose for antinociception (D50) (Tallarida, 2000) were calculated from raw hot plate data using non-linear regression (GraphPad, Prism). The lower limit for calculating D50 values was the mean baseline score, and the upper limit was the mean hot plate latency following administration of the highest morphine dose (10 μg). Changes in morphine potency as a result of microinjecting glutamate antagonists were assessed using ANOVA. A repeated measures ANOVA (Group x Trial) was used to assess differences in hot plate latency as a result of injecting kynurenic acid and MK-801 alone. Only rats with injections in or on the border of the ventrolateral PAG were included in data analysis.

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH grant DA015498.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albin RL, Makowiec RL, Hollingsworth Z, Dure L.S.t., Penney JB, Young AB. Excitatory amino acid binding sites in the periaqueductal gray of the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1990;118:112–5. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RM, Dykstra LA. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists potentiate the antinociceptive effects of morphine in squirrel monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:288–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behbehani MM, Fields HL. Evidence that an excitatory connection between the periaqueductal gray and nucleus raphe magnus mediates stimulation produced analgesia. Brain Res. 1979;170:85–93. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90942-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitz AJ. Relationship of glutamate and aspartate to the periaqueductal gray-raphe magnus projection: analysis using immunocytochemistry and microdialysis. J Histochem Cytochem. 1990;38:1755–65. doi: 10.1177/38.12.1701457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal SA, Morgan MM, Craft RM. PAG mu opioid receptor activation underlies sex differences in morphine antinociception. Behav Brain Res. 2007;177:126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrino L, Oliva P, Rossi F, Palazzo E, Nobili B, Maione S. Interaction between metabotropic and NMDA glutamate receptors in the periaqueductal grey pain modulatory system. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001;364:437–43. doi: 10.1007/s002100100477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bespalov A, Kudryashova M, Zvartau E. Prolongation of morphine analgesia by competitive NMDA receptor antagonist D-CPPene (SDZ EAA 494) in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;351:299–305. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulka A, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Xu XJ. Differential antinociception by morphine and methadone in two sub-strains of Sprague-Dawley rats and its potentiation by dextromethorphan. Brain Res. 2002;942:95–100. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieng B, Christie MJ. Inhibition by opioids acting on mu-receptors of GABAergic and glutamatergic postsynaptic potentials in single rat periaqueductal gray neurones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:303–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb16209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements JR, Madl JE, Johnson RL, Larson AA, Beitz AJ. Localization of glutamate, glutaminase, aspartate and aspartate aminotransferase in the rat midbrain periaqueductal gray. Exp Brain Res. 1987;67:594–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00247290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commons KG, van Bockstaele EJ, Pfaff DW. Frequent colocalization of mu opioid and NMDA-type glutamate receptors at postsynaptic sites in periaqueductal gray neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1999;408:549–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM, Lee DA. NMDA antagonist modulation of morphine antinociception in female vs. male rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;80:639–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depaulis A, Morgan MM, Liebeskind JC. GABAergic modulation of the analgesic effects of morphine microinjected in the ventral periaqueductal gray matter of the rat. Brain Res. 1987;436:223–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL, Bry J, Hentall I, Zorman G. The activity of neurons in the rostral medulla of the rat during withdrawal from noxious heat. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2545–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-12-02545.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer BD, Carrigan KA, Dykstra LA. Effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists on acute morphine-induced and l-methadone-induced antinociception in mice. J Pain. 2005;6:425–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossum EN, Lisowski MJ, Macey TA, Ingram SL, Morgan MM. Microinjection of the vehicle dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) into the periaqueductal gray modulates morphine antinociception. Brain Res. 2008;1204:53–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Fong J, von Zastrow M, Whistler JL. Regulation of opioid receptor trafficking and morphine tolerance by receptor oligomerization. Cell. 2002;108:271–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00613-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinricher MM, Morgan MM, Fields HL. Direct and indirect actions of morphine on medullary neurons that modulate nociception. Neuroscience. 1992;48:533–43. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90400-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinricher MM, Morgan MM, Tortorici V, Fields HL. Disinhibition of off-cells and antinociception produced by an opioid action within the rostral ventromedial medulla. Neuroscience. 1994;63:279–88. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinricher MM, McGaraughty S, Farr DA. The role of excitatory amino acid transmission within the rostral ventromedial medulla in the antinociceptive actions of systemically administered morphine. Pain. 1999;81:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinricher MM, Schouten JC, Jobst EE. Activation of brainstem N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors is required for the analgesic actions of morphine given systemically. Pain. 2001;92:129–38. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00480-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram SL, Vaughan CW, Bagley EE, Connor M, Christie MJ. Enhanced opioid efficacy in opioid dependence is caused by an altered signal transduction pathway. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10269–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10269.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram SL, Macey TA, Fossum EN, Morgan MM. Tolerance to repeated morphine administration is associated with increased potency of opioid agonists. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2494–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquet YF, Lajtha A. Paradoxical effects after microinjection of morphine in the periaqueductal gray matter in the rat. Science. 1974;185:1055–7. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4156.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquet YF, Lajtha A. The periaqueductal gray: site of morphine analgesia and tolerance as shown by 2-way cross tolerance between systemic and intracerebral injections. Brain Res. 1976;103:501–13. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquet YF. The NMDA receptor: central role in pain inhibition in rat periaqueductal gray. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;154:271–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TS, Yaksh TL. Comparison of antinociceptive action of morphine in the periaqueductal gray, medial and paramedial medulla in rat. Brain Res. 1986;363:99–113. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TS, Yaksh TL. The antinociceptive activity of excitatory amino acids in the rat brainstem: an anatomical and pharmacological analysis. Brain Res. 1992;569:255–67. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90637-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozela E, Popik P. A complete analysis of NMDA receptor subunits in periaqueductal grey and ventromedial medulla of morphine tolerant mice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:290–3. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane DA, Morgan MM. Antinociceptive tolerance to morphine from repeated nociceptive testing in the rat. Brain Res. 2005;1047:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane DA, Patel PA, Morgan MM. Evidence for an intrinsic mechanism of antinociceptive tolerance within the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray of rats. Neuroscience. 2005;135:227–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larcher A, Laulin JP, Celerier E, Le Moal M, Simonnet G. Acute tolerance associated with a single opiate administration: involvement of N-methyl-D-aspartate-dependent pain facilitatory systems. Neuroscience. 1998;84:583–9. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00556-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maione S, Marabese I, Oliva P, de Novellis V, Stella L, Rossi F, Filippelli A. Periaqueductal gray matter glutamate and GABA decrease following subcutaneous formalin injection in rat. Neuroreport. 1999;10:1403–7. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199905140-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maione S, Oliva P, Marabese I, Palazzo E, Rossi F, Berrino L, Filippelli A. Periaqueductal gray matter metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate formalin-induced nociception. Pain. 2000;85:183–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Price DD, Caruso FS, Mayer DJ. Oral administration of dextromethorphan prevents the development of morphine tolerance and dependence in rats. Pain. 1996;67:361–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J. NMDA and opioid receptors: their interactions in antinociception, tolerance and neuroplasticity. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1999;30:289–304. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marabese I, de Novellis V, Palazzo E, Mariani L, Siniscalco D, Rodella L, Rossi F, Maione S. Differential roles of mGlu8 receptors in the regulation of glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid release at periaqueductal grey level. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49(Suppl 1):157–66. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer DJ, Wolfle TL, Akil H, Carder B, Liebeskind JC. Analgesia from electrical stimulation in the brainstem of the rat. Science. 1971;174:1351–4. doi: 10.1126/science.174.4016.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer PJ, Fossum EN, Ingram SL, Morgan MM. Analgesic tolerance to microinjection of the micro-opioid agonist DAMGO into the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:1580–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau JL, Fields HL. Evidence for GABA involvement in midbrain control of medullary neurons that modulate nociceptive transmission. Brain Res. 1986;397:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MM, Heinricher MM, Fields HL. Circuitry linking opioid-sensitive nociceptive modulatory systems in periaqueductal gray and spinal cord with rostral ventromedial medulla. Neuroscience. 1992;47:863–71. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MM, Whitney PK, Gold MS. Immobility and flight associated with antinociception produced by activation of the ventral and lateral/dorsal regions of the rat periaqueductal gray. Brain Res. 1998;804:159–66. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00669-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MM, Clayton CC, Lane DA. Behavioral evidence linking opioid-sensitive GABAergic neurons in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray to morphine tolerance. Neuroscience. 2003;118:227–32. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00822-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MM, Clayton CC. Defensive behaviors evoked from the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray of the rat: comparison of opioid and GABA disinhibition. Behav Brain Res. 2005;164:61–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MM, Fossum EN, Levine CS, Ingram SL. Antinociceptive tolerance revealed by cumulative intracranial microinjections of morphine into the periaqueductal gray in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;85:214–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J. Glutamate- and GABA-containing neurons in the mouse and rat brain, as demonstrated with a new immunocytochemical technique. J Comp Neurol. 1984;229:374–92. doi: 10.1002/cne.902290308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson SJ. The rat brain, in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; Sydney: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Plesan A, Hedman U, Xu XJ, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. Comparison of ketamine and dextromethorphan in potentiating the antinociceptive effect of morphine in rats. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:825–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199804000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renno WM, Mullett MA, Beitz AJ. Systemic morphine reduces GABA release in the lateral but not the medial portion of the midbrain periaqueductal gray of the rat. Brain Res. 1992;594:221–32. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renno WM. Microdialysis of excitatory amino acids in the periaqueductal gray of the rat after unilateral peripheral inflammation. Amino Acids. 1998;14:319–31. doi: 10.1007/BF01318851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DV. Surgery in the rat during electrical analgesia induced by focal brain stimulation. Science. 1969;164:444–5. doi: 10.1126/science.164.3878.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandkuhler J, Gebhart GF. Relative contributions of the nucleus raphe magnus and adjacent medullary reticular formation to the inhibition by stimulation in the periaqueductal gray of a spinal nociceptive reflex in the pentobarbital-anesthetized rat. Brain Res. 1984;305:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)91121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman AD, Gebhart GF. Pain-induced alteration of glutamate in periaqueductal central gray and its reversal by morphine. Life Sci. 1974;15:1781–9. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(74)90179-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva E, Hernandez L, Contreras Q, Guerrero F, Alba G. Noxious stimulation increases glutamate and arginine in the periaqueductal gray matter in rats: a microdialysis study. Pain. 2000;87:131–5. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00275-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuciak JA, Advokat C. Tolerance to morphine microinjections in the periaqueductal gray (PAG) induces tolerance to systemic, but not intrathecal morphine. Brain Res. 1987;424:311–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91476-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida RJ. Drug Synergism and Dose-Effect Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tolle TR, Berthele A, Zieglgansberger W, Seeburg PH, Wisden W. The differential expression of 16 NMDA and non-NMDA receptor subunits in the rat spinal cord and in periaqueductal gray. J Neurosci. 1993;13:5009–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-12-05009.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortorici V, Robbins CS, Morgan MM. Tolerance to the antinociceptive effect of morphine microinjections into the ventral but not lateral-dorsal periaqueductal gray of the rat. Behav Neurosci. 1999;113:833–9. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.113.4.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortorici V, Morgan MM, Vanegas H. Tolerance to repeated microinjection of morphine into the periaqueductal gray is associated with changes in the behavior of off- and on-cells in the rostral ventromedial medulla of rats. Pain. 2001;89:237–44. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo KA, Akil H. Inhibition of morphine tolerance and dependence by the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801. Science. 1991;251:85–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1824728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo KA, Akil H. Inhibition of opiate tolerance by non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists. Brain Res. 1994;633:178–88. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91538-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urca G, Nahin RL, Liebeskind JC. Glutamate-induced analgesia: blockade and potentiation by naloxone. Brain Res. 1980;192:523–30. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90902-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan CW, Christie MJ. Presynaptic inhibitory action of opioids on synaptic transmission in the rat periaqueductal grey in vitro. J Physiol. 1997;498(Pt 2):463–72. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan CW, Ingram SL, Christie MJ. Actions of the ORL1 receptor ligand nociceptin on membrane properties of rat periaqueductal gray neurons in vitro. J Neurosci. 1997a;17:996–1003. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00996.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan CW, Ingram SL, Connor MA, Christie MJ. How opioids inhibit GABA-mediated neurotransmission. Nature. 1997b;390:611–4. doi: 10.1038/37610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambotti F, Zonta N, Parenti M, Tommasi R, Vicentini L, Conci F, Mantegazza P. Periaqueductal gray matter involvement in the muscimol-induced decrease of morphine antinociception. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1982;318:368–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00501180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]