Abstract

Porous Nitinol (PNT) has found vast applications in the medical industry as interbody fusion devices, synthetic bone grafts, etc. However, the tendency of the PNT to corrode is anticipated to be greater as compared to solid nitinol since there is a larger surface area in contact with body fluids. In such cases, surface preparation is known to play a major role in a material’s biocompatibility. In an effort to check the effect of surface treatments on the in vitro corrosion properties of PNT, in this investigation, they were subjected to different surface treatments such as boiling in water, dry heating, and passivation. The localized corrosion resistance of alloys before and after each treatment was evaluated in phosphate buffer saline solution (PBS) using cyclic polarization tests in accordance with ASTM F 2129-08.

Keywords: biocompatibility, corrosion, cyclic polarization, passivation, porous NiTi

1. Introduction

Porous Nitinol (PNT) is utilized in a wide variety of medical applications such as bone grafts, intervertebral fusion devices, dental implants, tissue repair, and bone reconstruction due to good osteoconductive properties (Ref 1–3), open porosity (65 ± 5%), high strength, and super elastic behavior. Corrosion of Nitinol implants not only leads to failure of the device but also may result in allergic, toxic, and carcinogenic effects in patients (Ref 4, 5). Although Nitinol normally has a 1:1 ratio of titanium and nickel, the phase responsible for the shape memory effect, NiTi, occurs at compositions between 49.5 and 53 at.% Ni. Nevertheless, researchers (Ref 6) have shown that the Ti:Ni ratio varies as much as one order of magnitude as a result of surface treatment. In an effort to understand the effect of surface treatments on the localized corrosion resistance of PNT, a combination of four methods of surface treatment were utilized, namely boiling in distilled water at 132 °C for 30 min, dry heating in a continuous supply of air at 132 °C for 1 h, etching in acid mixture for 1 min, and passivation in 20% concentrated nitric acid for 20 min. The susceptibility to corrosion of surface-treated PNT was evaluated by conducting cyclic polarization tests in accordance with ASTM F 2129-08 (Ref 7). This is the currently preferred in vitro method for assessing the corrosion resistance of implantable medical devices, where the difference between the break down potential, Eb, and rest potential, Er, is used as a measure of the resistance to localized corrosion. Five samples were subjected to each of the aforementioned surface treatments and the average values of Eb and Er were evaluated.

2. Materials

2.1 Test Articles

PNT specimens (Actipore) used in this investigation were obtained from Biorthex Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada. The material was prepared by the self-propagating high-temperature synthesis (SHS) method with the following physical properties: 230 ± 130 μm pores, 65 ± 5% porosity, Ø = 12.5 ± 0.25 mm, and L = 30.0 ± 0.1 mm. Several discs of thickness 2.5 ± 0.25 mm were cut with a high-speed saw.

2.2 Reagents

Phosphate buffer saline solution (PBS) of pH 7.2, a reagent grade chemical conforming to the specifications of the Committee on Analytical Reagents of the American Chemical Society was used as the standard test solution.

1HF + 4HNO3 + H2O acid mixture was used as the etchant for the PNT samples 20% conc. HNO3 was used as the passivation solution.

3. Experimental Methods

3.1 Specimen Preparation

The following surface treatments were adopted:

(a) PNT samples were initially etched (Ref 8) in an acid mixture comprising of 1HF + 4HNO3 + 5H2O at room temperature with continuous ultrasonic stirring for 1 min; (b) Etched samples were boiled in distilled water (Ref 9) at 132 °C for 30 min. These samples were then passivated by immersing them in 20% conc. HNO3 at 80 °C for 20 min (Ref 10); (c) Untreated PNT samples were first dry heated (Ref 9) at 132 °C in a tubular furnace with a continuously supply of air for 1 h and then passivated; (d) Untreated PNT was first water boiled and then passivated.

3.2 Cyclic Polarization Tests

In vitro cyclic polarization tests were conducted (Ref 11) in accordance with the ASTM F 2129-08 (Ref 7) standard on as-received PNT and surface-treated PNTs. The Gammry corrosion cell was first cleaned with deionized water, rinsed with PBS solution, and filled with approximately 50 mL of PBS. The cell with contents was brought up to 37 °C by placing it in a controlled temperature water bath. The PBS solution was purged with ultrahigh-purity nitrogen for 30 min prior to immersion of the pellet. The pellet was immersed with nitrogen purging for an additional 30 min before starting the cyclic polarization tests. A saturated calomel electrode was used as the reference electrode and it was inserted into a Luggin Capillary. The surface area of the pellet in contact with PBS was carefully calculated to increase the accuracy of the corrosion parameters. The cyclic polarization option was selected on a Salartron SI 1287 Electrochemical Interface with a scan rate of 0.167 mV/s over a potential range between −0.5 and 1.5 V versus a saturated calomel electrode (SCE).

4. Results

Cyclic polarization tests were conducted and the average corrosion parameters for five surface treatments each utilizing five samples are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Average corrosion parameters obtained for treated and untreated PNTs

| Corrosion parameters | Untreated PNT | Etched, water boiled, and passivated PNT | Dry-heated and passivated PNT | Water boiled and passivated PNT | Etched PNT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb, V | 1.0841 | 1.1010 | 1.0546 | 1.0587 | 0.9507 |

| Er, V | −0.2272 | −0.3280 | −0.1162 | −0.1942 | −0.3995 |

| Ep, V | 1.0536 | 1.0472 | 0.9810 | 0.9800 | 0.9139 |

| Eb − Er, V | 1.3113 | 1.5005 | 1.1708 | 1.2530 | 1.2787 |

5. Discussion

Table 1 shows the average corrosion parameters for the treated and untreated PNTs. The PNT that was etched, water boiled, and passivated was found to have superior resistance to pitting corrosion in terms of the Eb − Er (1.5005), whereas the dry-heated and passivated PNT showed the least corrosion resistance (1.1708). The higher resistance to pitting corrosion exhibited by the former etched, water boiled, and passivated PNT was attributed to selective etching of nickel oxides from the surface of the PNT (Ref 12), so that after water boiling and passivation, a higher proportion of titanium oxide was produced at the surface (Ref 6). The least corrosion resistance exhibited by the latter was due to the oxidation of Nitinol at elevated temperature, which leads to the formation of nickel oxide species that are more prone to corrosion (Ref 6). There was no significant difference in corrosion resistance between the untreated (as-received) PNT and those subjected to water boiling with passivation and etching. The highest break down potential (Eb 1.1010 V) was observed for the etched, water boiled, and passivated sample. The etched sample had the lowest value (Eb 0.9507 V). The highest protection potential, EP, was obtained for the untreated sample, followed by the etched, water boiled, and passivated sample.

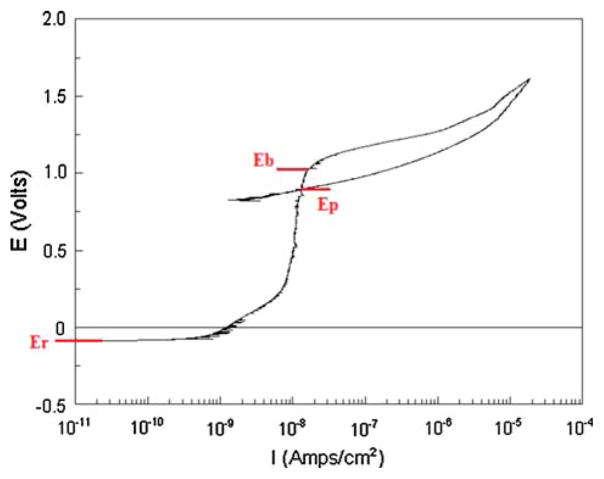

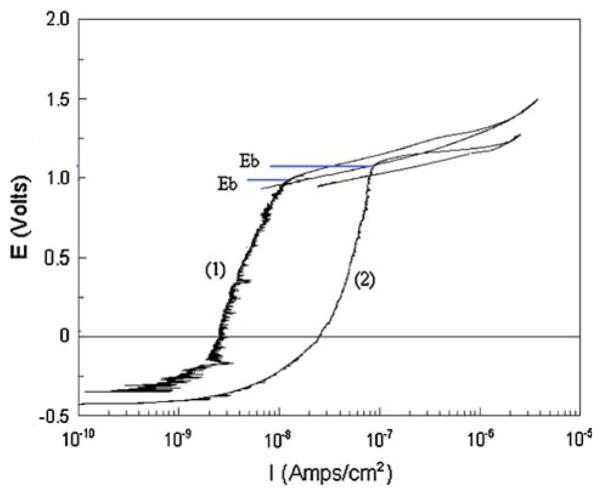

The cyclic polarization curve shown in Fig. 1 represents the general corrosion behavior of PNTs in this investigation. Figure 2 shows a comparison of cyclic polarization curves and break down potential (Eb) values for untreated and etched, water boiled, and passivated PNTs (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Cyclic polarization curve of an etched PNT sample showing Eb, break down potential, Ep, protection potential, and Er, rest or open circuit potential

Fig. 2.

A comparison of cyclic polarization curves and break down potential (Eb) values for (1) untreated and (2) etched + water boiled + passivated PNTs

Table 2.

Summary of test results

| Untreated sample |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb | Er | Ep | Eb − Er | |

| Mean | 1.0841 | −0.2272 | 1.0536 | 1.3113 |

| SD | 0.06229 | 0.09259 | 0.0800 | 0.0654 |

| Max | 1.1520 | −0.1346 | 1.1320 | 1.4050 |

| Min | 1.0100 | −0.3200 | 0.9550 | 1.2168 |

| Etch only |

Dry heated + Passivated |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb | Er | Ep | Eb − Er | Eb | Er | Ep | Eb − Er | |

| Mean | 0.9507 | −0.3280 | 0.9139 | 1.2787 | 1.0546 | −0.1162 | 0.9810 | 1.1708 |

| SD | 0.0154 | 0.0917 | 0.0765 | 0.0964 | 0.0244 | 0.0538 | 0.0446 | 0.0467 |

| Max | 0.9200 | −0.1734 | 0.9400 | 1.3813 | 1.0700 | 0.2107 | 1.0350 | 1.2457 |

| Min | 0.0961 | −0.4213 | 0.8970 | 1.1284 | 1.018 | 0.0561 | 0.9100 | 1.1347 |

| Etched + water boiled + passivated |

Water boiled + Passivated |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eb | Er | Ep | Eb − Er | Eb | Er | Ep | Eb − Er | |

| Mean | 1.1010 | −0.3280 | 1.0472 | 1.5005 | 1.0587 | −0.1942 | 0.9800 | 1.2530 |

| SD | 0.0164 | 0.0381 | 0.0398 | 0.0446 | 0.0375 | 0.0222 | 0.0112 | 0.0264 |

| Max | 1.1100 | −0.4335 | 1.1040 | 1.5400 | 1.0700 | −0.1627 | 0.9950 | 1.2752 |

| Min | 1.0750 | −0.3573 | 1.0150 | 1.4960 | 1.0450 | −0.2252 | 0.9650 | 1.2077 |

6. Conclusion

In vitro corrosion tests (ASTM F 2129-08) in PBS solution were conducted on surface-treated PNT to assess its localized corrosion resistance. Since Nitinol oxidation at elevated temperature leads to the formation of different oxide species, it is more prone to corrosion. This was verified in the case of dry-heated and passivated PNT samples, which revealed the least resistance to pitting corrosion than all tested samples. The etched, water boiled, and passivated sample produced the highest resistance to pitting corrosion. This was attributed to selective etching of nickel oxides from the surface of the PNT and the formation of a higher proportion of titanium oxide after water boiling and passivation.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number SC3GM084816 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This article is an invited paper selected from presentations at Shape Memory and Superelastic Technologies 2008, held September 21–25, 2008, in Stresa, Italy, and has been expanded from the original presentation.

References

- 1.Assad M, Jarzem P, Leroux MA, Rivard CH. Porous Nitinol for Intervertebral Fusion: A Histomorphometry and Radiological Study in Sheep. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2003;64(2):107–120. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.10530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu MH. Fabrication of Nitinol Materials and Components. Proceedings of the International Conference on Shape Memory and Super-elastic Technologies; Kunming, China. 2001. pp. 285–292. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayers RA, Simske SJ, Bateman TA, Petkus A, Sachdeva RLC, Gyunter VE. Effect of Nitinol Implants Porosity on Cranial Bone in Growth and Apposition After 6 weeks. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 1999;45(1):42–47. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199904)45:1<42::aid-jbm6>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riepe G, Heintz C, Chakfe N, Morlock M, Fengles WG, Imig H. Degradation of Stentor Device After Implantation in Human Beings. Proceedings of the International Conference on Shape Memory and Superelastic Technologies; Pacific Groove, CA. 2000. pp. 279–283. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li YH, Rao GB, Rong LJ, Li YY, Ke W. Effect of Pores on Corrosion Characteristics of Porous NiTi Alloy in Simulated Body Fluid. Mater Sci Eng A. 2003;363:356–359. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shabalovskaya SA. Physicochemical and Biological Aspects of Nitinol as a Biomaterial. Int Mater Rev. 2001;46(4):230–250. [Google Scholar]

- 7.“Standard Test Method for Conducting Cyclic Potentiodynamic Polarization Measurements to Determine the Corrosion Susceptibility of Small Implant Devices,” ASTM F 2129-08, Annual Book of ASTM Standards

- 8.Trigwell S, Hayden RD, Nelson KF, Selvaduray G. Effects of Surface Treatment on the Surface Chemistry of NiTi Alloy for Biomedical Applications. Surf Interface Anal. 1998;26:483–489. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thierry B, Tabrizian M, Savadogo O, Yahia L’H. Effects of Sterilization Processes on NiTi Alloy: Surface Characterization. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2000;49(1):685–693. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200001)49:1<88::aid-jbm11>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Brien B, Carroll WM, Kelly MJ. Passivation of Nitinol Wire for Vascular Implants—A Demonstration of the Benefits. Biomaterials. 2002;23(8):1739–1748. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munroe N, Haider W, Datye A, Wu KH. Corrosion Behavior of Electropolished Implants Alloys. Proceedings of the International Conference on Shape Memory and Superelastic Technologies; Dec 3–5, 2007; Tsukuba, Japan. 2007. pp. 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shabalovskaya S, Rondelli G, Anderegg J, Simpson B, Budko S. Effect of Chemical Etching and Aging in Boiling Water on the Corrosion Resistance of Nitinol Wires with Black Oxide Resulting from Manufacturing Process. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2003;66:331–340. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]