Abstract

The in vitro activity of nemonoxacin (TG-873870), a novel nonfluorinated quinolone, was tested against 2,440 clinical isolates. Nemonoxacin was at least fourfold more active than levofloxacin and moxifloxacin against most gram-positive cocci tested (shown by the following MIC90/range [μg/ml] values; community-associated methicillin [meticillin]-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, 0.5/0.015 to 2; Staphylococcus epidermidis, 0.5/0.015 to 4 for methicillin-susceptible staphylococci and 2/0.12 to 2 for methicillin-resistant staphylococci; Streptococcus pneumoniae, 0.015/≤0.008 to 0.25; Enterococcus faecalis, 1/0.03 to 128). Nemonoxacin activity against gram-negative bacilli was similar to levofloxacin and moxifloxacin (MIC90/range [μg/ml]; Escherichia coli, 32/≤0.015 to ≥512; Klebsiella pneumoniae, 2/≤0.015 to 128; K. oxytoca, 0.5/0.06 to 1; Proteus mirabilis, 16/0.25 to ≥512; Pseudomonas aeruginosa, 32/≤0.015 to ≥512; Acinetobacter baumannii, 1/0.12 to 16).

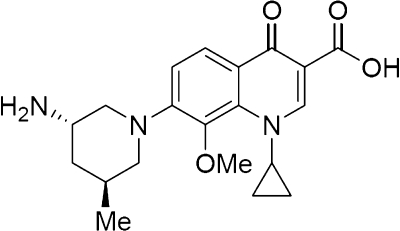

Nemonoxacin (TG-873870) (TaiGen Biotechnology Co. Ltd.) is a novel C-8-methoxy nonfluorinated quinolone that is currently being investigated for clinical use (Fig. 1). On the basis of other fluoroquinolones with similar chemical structures, nemonoxacin is expected to have a broad spectrum of activity and reduced toxicity. C-8-methoxy substituents have been associated with an improved spectrum of activity, including increased activity against gram-positive cocci, and reduced mutant selection (1, 13). The removal of the fluorine residue may reduce the incidence of toxic side effects (2).

FIG. 1.

Nemonoxacin chemical structure. Me, methyl group.

The activity of nemonoxacin against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Nocardia spp. has been described previously (9, 15). Current studies with nemonoxacin indicate that it is active against a variety of gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, including antibiotic-resistant organisms like methicillin (meticillin)-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (8, 12, 16). Good safety and efficacy data have been reported for animal studies (6-8). Nemonoxacin was noted to have a safety profile similar to that of levofloxacin in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia (16).

The purpose of this study was to assess the activity of nemonoxacin and other fluoroquinolones against gram-positive and gram-negative organisms obtained from Canadian hospitals as part of the CANWARD 2007 study. The most prevalent gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens collected as part of the CANWARD study (www.can-r.ca) were included in this analysis.

(Abstracts of this data were presented at a joint meeting of the 48th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy and the 46th Infectious Diseases Society of America, Washington, DC, 2008, abstr. C1-1957 and F1-2057.)

Clinical isolates were collected as part of CANWARD, an ongoing national surveillance system designed to assess pathogen prevalence and antibiotic resistance from respiratory, skin and soft tissue, urinary, and bacteremic infections in Canadian hospitals (18). Twelve sentinel hospitals from across Canada submitted clinical isolates from blood, respiratory, urine, and wound/intravenous site specimens from patients affiliated with hospital clinics, emergency rooms, medical/surgical wards, and intensive care units. All organisms were deemed clinically significant and identified at the originating center using local site criteria.

The organisms evaluated in this study included 374 methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) isolates, 127 MRSA (25 community-associated MRSA [CA-MRSA] isolates and 99 hospital-associated MRSA [HA-MRSA] isolates), 43 methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus epidermidis (MSSE) isolates, 9 methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis (MRSE) isolates, 655 Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates (including 32 penicillin-resistant isolates), 81 Enterococcus faecalis isolates, 38 Enterococcus faecium isolates, 599 Escherichia coli isolates,199 Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates, 32 Klebsiella oxytoca isolates, 72 Enterobacter cloacae isolates, 33 Proteus mirabilis isolates, 137 Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates, 26 Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolates, and 15 Acinetobacter baumannii isolates.

In vitro susceptibilities were determined by the broth microdilution method in accordance with the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (3). The fluoroquinolones tested in this study included ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and nemonoxacin. Custom-designed 96-well microdilution panels containing doubling dilutions of the antimicrobial agents in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth with 5% lysed horse blood were produced to determine the MICs. Quality control of the broth microdilution panels was conducted using appropriate CLSI organisms and MIC ranges (3). Quality control for nemonoxacin was performed using the following ATCC quality control organisms with moxifloxacin ranges: S. pneumoniae 49619, S. aureus 29213, E. faecalis 29212, E. coli 25922, and P. aeruginosa 27853. MICs were interpreted on the basis of CLSI breakpoints (4).

MRSA were assigned to the Canadian epidemic strain types (CMRSA-1 to CMRSA-10) (14) by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) or staphylococcal protein A (spa) typing (5, 10) as previously described (11). CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA were differentiated genotypically (by PFGE pattern), as epidemiologic data were unavailable (11). CMRSA-7 (USA400) and CMRSA-10 (USA300) isolates were identified as CA-MRSA, while organisms with all other CMRSA patterns were considered HA-MRSA. Isolates that were not assigned to one of the epidemic strains by PFGE or spa typing were labeled “unique” and were not considered HA-MRSA or CA-MRSA (11).

In 2007, 7,881 clinical isolates were collected as part of CANWARD (18). The in vitro activity of nemonoxacin was tested against 2,440 gram-positive cocci and gram-negative bacilli.

Table 1 presents the MIC distributions and MIC90s for nemonoxacin and other fluoroquinolones against gram-positive cocci. Nemonoxacin displayed greater activity than the other fluoroquinolones tested against the MSSA (MIC90, 0.12 μg/ml). In addition, nemonoxacin displayed slightly greater activity than the other fluoroquinolones tested against the MRSA (nemonoxacin, 4 μg/ml; ciprofloxacin, ≥16 μg/ml; levofloxacin, ≥32 μg/ml; moxifloxacin, 8 μg/ml [MIC50s shown]). The activity of all of the fluoroquinolones was reduced against MRSA, but nemonoxacin was the least affected (Table 1). The higher nemonoxacin MICs of ≥4 μg/ml were noted only among the HA-MRSA that displayed high levels of resistance to levofloxacin and moxifloxacin. By PFGE, the majority of these isolates were genetically unrelated to other strains in the study (40%) or were in small clusters of two or three isolates (28%) (11). Interestingly, nemonoxacin remained highly active against CA-MRSA (MIC50, 0.25 μg/ml; MIC90, 0.5 μg/ml). The activity of nemonoxacin was significantly greater against S. aureus with levofloxacin MICs of <2 μg/ml (MIC90, 0.06 μg/ml) than isolates with levofloxacin MICs of ≥2 μg/ml (MIC90, 16 μg/ml). Nemonoxacin was at least eightfold more active than the other fluoroquinolones against S. epidermidis (MSSE and MRSE). The activity of nemonoxacin against S. pneumoniae (MIC90, 0.015 μg/ml), including penicillin-resistant strains (MIC90, 0.03 μg/ml), was the greatest of the fluoroquinolones tested. Similarly, nemonoxacin was the most active fluoroquinolone against E. faecalis. Nemonoxacin was more active against E. faecalis (MIC90, 1 μg/ml) than E. faecium (MIC90, 128 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

In vitro activity of nemonoxacin and other fluoroquinolones against gram-positive cocci

| Organism (n) | FQa | No. of isolates (% [cumulative]) with the following MIC (μg/ml)b: |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.008 | 0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | ≥256 | ||

| S. aureus | |||||||||||||||||

| MSSA (374) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 21c (5.6) | 93 (30.5) | 155 (71.9) | 63 (88.8) | 10 (91.4) | 4 (92.5) | 5 (93.9) | 4 (94.9) | 4 (96) | 11 (98.9) | 1 (99.2) | 2 (99.7) | 1 (100) | ||||

| CIP | 1c (0.3) | 4 (1.3) | 57 (16.6) | 181 (65) | 80 (86.4) | 13 (89.8) | 6 (91.4) | 32d (100) | |||||||||

| LVX | 2c (0.5) | 48 (13.4) | 256 (81.8) | 26 (88.8) | 10 (91.4) | 2 (92) | 6 (93.6) | 24d (100) | |||||||||

| MXF | 229c (61.2) | 99 (87.7) | 14 (91.4) | 1 (91.7) | 5 (93) | 3 (93.9) | 17 (98.4) | 6d (100) | |||||||||

| MRSA (127) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 6 (4.7) | 2 (6.3) | 4 (9.4) | 9 (16.5) | 10 (24.4) | 13 (34.6) | 4 (37.8) | 35 (65.4) | 12 (74.8) | 29 (97.6) | 3 (100) | ||||||

| CIP | 1 (0.8) | 7 (6.3) | 3 (8.7) | 1 (9.4) | 115d(100) | ||||||||||||

| LVX | 1 (0.8) | 10 (8.7) | 1 (9.4) | 17 (22.8) | 2 (24.4) | 96d(100) | |||||||||||

| MXF | 8c (6.3) | 4 (9.4) | 15 (21.3) | 6 (26) | 32 (51.2) | 62d(100) | |||||||||||

| Levofloxacin-susceptible S. aureus (355) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 21c (5.9) | 99 (33.8) | 158 (78.3) | 67 (97.1) | 10 (100) | ||||||||||||

| CIP | 1c (0.3) | 4 (1.4) | 58 (17.7) | 189 (71) | 83 (94.4) | 13 (98) | 7 (100) | ||||||||||

| MXF | 238c (67) | 103 (96.1) | 14 (100) | ||||||||||||||

| Non-levofloxacin-susceptible S. aureus (147) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 13 (8.9) | 15 (19) | 17 (30.6) | 8 (36.1) | 46 (67.3) | 13 (76.2) | 31 (97.3) | 1 (98) | 3 (100) | ||||||||

| CIP | 147d(100) | ||||||||||||||||

| MXF | 1 (0.7) | 20 (14.3) | 9 (20.4) | 49 (53.7) | 68d(100) | ||||||||||||

| CA-MRSA (25) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 4 (16) | 3 (28) | 8 (60) | 9 (92) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

| CIP | 1 (4) | 3 (16) | 3 (28) | 1 (32) | 17 (100)d | ||||||||||||

| LVX | 1 (4) | 6 (24) | 1 (32) | 16 (96) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

| MXF | 5c (20) | 3 (32) | 15 (92) | 2 (100) | |||||||||||||

| HA-MRSA (99) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (4) | 1 (5.1) | 13 (18.2) | 4 (22.2) | 35 (57.6) | 11 (68.7) | 28 (97) | 3 (100) | |||||||

| CIP | 3 (3) | 96d(100) | |||||||||||||||

| LVX | 3 (3) | 1 (4) | 1 (5.1) | 94d(100) | |||||||||||||

| MXF | 3c (3) | 4 (7.1) | 32 (39.4) | 60d(100) | |||||||||||||

| S. epidermidis | |||||||||||||||||

| MSSE (43) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 16 (37.2) | 7 (53.5) | 2 (58.1) | 4 (67.4) | 8 (86) | 3 (93) | 1 (95.3) | 1 (97.8) | 1 (100) | ||||||||

| CIP | 2c (4.7) | 4 (14) | 15 (48.8) | 2 (53.9) | 3 (60.5) | 2 (65.1) | 15d(100) | ||||||||||

| LVX | 5 (11.6) | 18 (53.5) | 1 (55.8) | 3 (62.8) | 6 (76.7) | 5 (88.4) | 5d(100) | ||||||||||

| MXF | 13c (30.2) | 10 (53.5) | 1 (55.8) | 3 (62.8) | 5 (74.4) | 7 (90.7) | 1 (93) | 3d (100) | |||||||||

| MRSE (9) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 1 (11.1) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (100) | ||||||||||||||

| CIP | 1 (11.1) | 8d(100) | |||||||||||||||

| LVX | 1 (11.1) | 2 (33.3) | 6d(100) | ||||||||||||||

| MXF | 1 (11.1) | 2 (33.3) | 6d(100) | ||||||||||||||

| S. pneumoniae (655) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 126c (19.2) | 470 (91) | 53 (99.1) | 2 (99.4) | 2 (99.7) | 2 (100) | |||||||||||

| CIP | 2c (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 8 (1.8) | 150 (24.7) | 266 (65.3) | 199 (95.7) | 16 (98.2) | 6 (99.1) | 6d (100) | ||||||||

| LVX | 3c (0.5) | 5 (1.2) | 59 (10.2) | 387 (69.3) | 177 (96.3) | 20 (99.4) | 1 (99.5) | 2 (99.8) | 1 (100) | ||||||||

| MXF | 123c (18.9) | 409 (81.6) | 112 (98.8) | 2 (99.1) | 2 (99.4) | 3 (99.8) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||

| Penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae (32) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 27 (84.4) | 4 (96.9) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||||

| CIP | 2 (6.3) | 7 (28.1) | 20 (90.6) | 2 (96.9) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

| LVX | 1 (3.1) | 16 (53.1) | 12 (90.6) | 3 (100) | |||||||||||||

| MXF | 3c (9.4) | 16 (59.4) | 13 (100) | ||||||||||||||

| E. faecalis (81) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 2 (2.5) | 13 (18.5) | 31 (56.8) | 9 (67.9) | 2 (70.4) | 16 (90.1) | 6 (97.5) | 1 (98.8) | 1 (100) | ||||||||

| CIP | 2 (2.5) | 6 (9.9) | 27 (43.2) | 17 (64.2) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (67.9) | 26d(100) | ||||||||||

| LVX | 2 (2.5) | 27 (35.8) | 26 (67.9) | 26d(100) | |||||||||||||

| MXF | 1c (1.2) | 3 (4.9) | 32 (44.4) | 17 (65.4) | 2 (67.9) | 4 (72.8) | 22d(100) | ||||||||||

| E. faecium (38) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 3 (7.9) | 3 (15.8) | 5 (28.9) | 1 (31.6) | 4 (42.1) | 1 (44.7) | 4 (55.3) | 9 (79) | 2 (84.2) | 6 (100) | |||||||

| CIP | 6 (15.8) | 3 (23.7) | 1 (26.3) | 1 (28.9) | 27d(100) | ||||||||||||

| LVX | 4 (10.5) | 5 (23.7) | 2 (28.9) | 27d(100) | |||||||||||||

| MXF | 5 (13.2) | 2 (18.4) | 3 (26.3) | 1 (28.9) | 2 (34.2) | 25d(100) | |||||||||||

FQ, fluoroquinolone; NMX, nemonoxacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; LVX, levofloxacin; MXF, moxifloxacin.

The numbers of isolates and cumulative percentages for MIC90 values are shown in boldface type.

Lowest concentration tested. The actual MICs of some isolates may be lower than indicated.

Highest concentration tested. The actual MICs of some isolates may be higher than indicated.

The activity of nemonoxacin and other fluoroquinolones against gram-negative bacilli is displayed in Table 2 as MIC distributions and MIC90s. Among the members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, nemonoxacin displayed activity similar to the activities of the other fluoroquinolones (nemonoxacin MIC90s, 0.5 to 32 μg/ml; ciprofloxacin MIC90s, ≤0.06 to ≥16 μg/ml; levofloxacin MIC90s, ≤0.06 to 16 μg/ml; moxifloxacin MIC90s, 0.12 to ≥16 μg/ml). Comparable activity between nemonoxacin and moxifloxacin was noted for P. aeruginosa (MIC90s, ≥8 μg/ml), while nemonoxacin activity for S. maltophilia (MIC90s, ≥4 μg/ml) was similar to levofloxacin activity. Similarly to levofloxacin and moxifloxacin, nemonoxacin displayed good activity against A. baumannii (MIC90, 1 μg/ml).

TABLE 2.

In vitro activity of nemonoxacin and other antimicrobials against gram-negative bacilli

| Organism (n) | FQa | No. of isolates (% [cumulative]) with the following MIC (μg/ml)b: |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | ≥512 | ||

| E. coli (599) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 1c (0.2) | 8 (1.5) | 127 (22.7) | 211 (57.9) | 65 (68.8) | 22 (72.5) | 14 (74.8) | 4 (75.5) | 2 (75.8) | 20 (79.1) | 84 (93.2) | 30 (98.2) | 7 (99.3) | 2 (99.7) | 2d (100) | ||

| CIP | 404c (67.4) | 10 (69.1) | 22 (72.8) | 8 (74.1) | 7 (75.3) | 1 (75.5) | 1 (75.6) | 27 (80.1) | 119d(100) | ||||||||

| LVX | 398c (66.4) | 8 (67.8) | 13 (70) | 22 (73.6) | 9 (75.1) | 3 (75.6) | 17 (78.5) | 84 (92.5) | 45d (100) | ||||||||

| MXF | 361c (60.3) | 41 (67.1) | 10 (68.8) | 28 (73.5) | 10 (75.1) | 2 (75.5) | 11 (77.3) | 18 (80.3) | 118d(100) | ||||||||

| K. pneumoniae (199) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 1c (0.5) | 1 (1) | 1 (1.5) | 51 (27.1) | 82 (68.3) | 19 (77.9) | 18 (86.9) | 10 (92) | 4 (94) | 2 (95) | 1 (95.5) | 5 (98) | 1 (98.5) | 3 (100) | |||

| CIP | 147c (73.9) | 12 (79.9) | 11 (85.4) | 12 (91.5) | 1 (92) | 2 (93) | 1 (93.5) | 2 (94.5) | 11d (100) | ||||||||

| LVX | 139c (69.8) | 15 (77.4) | 2 (78.4) | 18 (87.4) | 10 (92.5) | 1 (93) | 6 (96) | 5 (98.5) | 3d (100) | ||||||||

| MXF | 48c (24.1) | 96 (72.4) | 11 (77.9) | 12 (83.9) | 15 (91.5) | 3 (93) | 3 (94.5) | 3 (96) | 8d (100) | ||||||||

| K. oxytoca (32) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 2 (6.3) | 7 (28.1) | 17 (81.3) | 5 (96.9) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

| CIP | 30c(93.8) | 1 (96.9) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||||

| LVX | 30c(93.8) | 2 (100) | |||||||||||||||

| MXF | 15c (46.9) | 15 (93.8) | 2 (100) | ||||||||||||||

| E. cloacae (72) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 6 (8.3) | 31 (51.4) | 23 (83.3) | 5 (90.3) | 1 (91.7) | 1 (93.1) | 2 (95.8) | 2 (98.6) | 1 (100) | ||||||||

| CIP | 64c (88.9) | 1 (90.3) | 1 (91.7) | 4 (97.2) | 1 (98.6) | 1 (100) | |||||||||||

| LVX | 63c (87.5) | 2 (90.3) | 1 (91.7) | 1 (93.1) | 3 (97.2) | 1 (98.6) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||

| MXF | 49c (68.1) | 14 (87.5) | 2 (90.3) | 1 (91.7) | 1 (93.1) | 1 (94.4) | 3 (98.6) | 1d (100) | |||||||||

| P. mirabilis (33) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 8 (24.2) | 10 (54.5) | 7 (75.8) | 1 (78.8) | 1 (81.8) | 3 (90.9) | 1 (93.9) | 1 (97) | 1d (100) | ||||||||

| CIP | 21c (63.6) | 3 (72.7) | 2 (78.8) | 1 (81.8) | 1 (84.8) | 5 (100) | |||||||||||

| LVX | 11c (33.3) | 10 (63.6) | 4 (75.8) | 1 (78.8) | 2 (84.8) | 3 (93.9) | 1 (97) | 1d (100) | |||||||||

| MXF | 1 (3) | 9 (30.3) | 11 (63.6) | 5 (78.8) | 1 (81.8) | 1 (84.8) | 5d(100) | ||||||||||

| P. aeruginosa (137) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 1c (0.7) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (4.4) | 14 (14.6) | 50 (51.1) | 21 (66.4) | 16 (78.1) | 1 (78.8) | 10 (86.1) | 7 (91.2) | 6 (95.6) | 3 (97.8) | 2 (99.3) | 1d (100) | |||

| CIP | 10c (7.3) | 28 (27.7) | 35 (53.3) | 16 (65) | 13 (74.5) | 7 (79.6) | 8 (85.4) | 7 (90.5) | 13d (100) | ||||||||

| LVX | 3c (2.2) | 4 (5.1) | 7 (10.2) | 44 (42.3) | 24 (59.9) | 14 (70.1) | 12 (78.8) | 8 (84.7) | 8 (90.5) | 13d (100) | |||||||

| MXF | 2c (1.5) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (5.8) | 24 (23.4) | 38 (51.1) | 18 (64.2) | 17 (76.6) | 32d(100) | |||||||||

| S. maltophilia (26) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 1 (3.8) | 6 (26.9) | 4 (42.3) | 8 (73.1) | 2 (80.8) | 3 (92.3) | 2 (100) | ||||||||||

| CIP | 1c (3.8) | 1 (7.7) | 7 (34.6) | 9 (69.2) | 3 (80.8) | 5d(100) | |||||||||||

| LVX | 1c (3.8) | 1 (7.7) | 10 (46.2) | 6 (69.2) | 4 (84.6) | 2 (92.3) | 2 (100) | ||||||||||

| MXF | 2 (7.7) | 2 (15.4) | 7 (42.3) | 6 (65.4) | 3 (76.9) | 4 (92.3) | 2 (100) | ||||||||||

| A. baumannii (15) | |||||||||||||||||

| NMX | 4 (26.7) | 7 (73.3) | 2 (86.7) | 1 (93.3) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

| CIP | 2 (13.3) | 6 (53.3) | 4 (80) | 1 (86.7) | 1 (93.3) | 1 (100) | |||||||||||

| LVX | 1c (6.7) | 5 (40) | 6 (80) | 1 (86.7) | 1 (93.3) | 1d (100) | |||||||||||

| MXF | 6c (40) | 6 (80) | 1 (86.7) | 1 (93.3) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

FQ, fluoroquinolone; NMX, nemonoxacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; LVX, levofloxacin; MXF, moxifloxacin.

The numbers of isolates and cumulative percentages for MIC90 values are shown in boldface type.

Lowest concentration tested. The actual MICs of some isolates may be lower than indicated.

Highest concentration tested. The actual MICs of some isolates may be higher than indicated.

On the basis of the free area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h (ƒAUC0-24) achieved using a 750-mg dose of nemonoxacin in the community-acquired pneumonia trial (49.1 μg·h/ml; C. Richard King, TaiGen Biotechnology Co. Ltd., personal communication), favorable ƒAUC0-24-to-MIC ratios (ƒAUC0-24/MIC) are attainable with many of the organisms described in this study. The ƒAUC0-24/MIC required to eradicate pathogens and prevent the emergence of resistance is dependent on the specific pathogen-quinolone combination, but it is generally accepted that ƒAUC0-24/MICs of ≥100 to 125 are needed for gram-negative bacilli (17). Among the gram-positive cocci, ratios of <40 (but >30) have been established for S. pneumoniae (17). Accordingly, nemonoxacin displays good pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics at the 750-mg dose with S. aureus (ƒAUC0-24/MIC, 393), CA-MRSA (ƒAUC0-24/MIC, 98), S. epidermidis (ƒAUC0-24/MIC, 98), and S. pneumoniae, including the penicillin-resistant isolates (ƒAUC0-24/MIC, >393). Similar to other fluoroquinolones, on the basis of the MICs for some gram-negative bacilli in this study, ƒAUC0-24/MICs of ≥100 to 125 would not be achieved with a nemonoxacin dose of 750 mg.

This study details the activity of nemonoxacin and other fluoroquinolones against a large collection of Canadian clinical isolates from the CANWARD 2007 surveillance program. Nemonoxacin displayed greater activity than the other fluoroquinolones against MSSA, MSSE, MRSE, S. pneumoniae, and E. faecalis. Nemonoxacin was more active than other fluoroquinolones versus MRSA. Interestingly, nemonoxacin maintained better activity against CA-MRSA than against HA-MRSA. Compared to CA-MRSA, the HA-MRSA isolates displayed greater resistance rates to all of the tested fluoroquinolones. The increase in the nemonoxacin MIC90 against non-levofloxacin-susceptible S. aureus compared to levofloxacin-susceptible S. aureus indicates that the activity of nemonoxacin against S. aureus is related to the activity of the fluoroquinolone class, in general. The greater susceptibility of the currently circulating strains of CA-MRSA to the fluoroquinolone class compared to HA-MRSA may account for the stronger activity of nemonoxacin observed against CA-MRSA. However, as CA-MRSA isolates become increasingly resistant to other antimicrobial agents, including the fluoroquinolones, the activity of nemonoxacin may be adversely affected. Against the gram-negative bacilli, nemonoxacin was found to have activity comparable to those of levofloxacin and moxifloxacin.

At this time, fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates from the CANWARD study are not molecularly characterized. Accordingly, a limitation of this study is the lack of analysis of nemonoxacin activity against isolates with known quinolone resistance-associated mutations. Future studies with characterized isolates are necessary.

The good activity of nemonoxacin against gram-positive and gram-negative organisms described herein suggests that further investigations with this novel C-8-methoxy nonfluorinated quinolone are warranted. In particular, the activity of nemonoxacin against gram-positive cocci should be studied further.

Acknowledgments

The participation of the CANWARD health care centers is gratefully acknowledged (D. Roscoe, Vancouver Hospital, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; R. Rennie, University of Alberta Hospitals, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; J. Blondeau, Royal University Hospital, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada; D. J. Hoban and G. G. Zhanel, Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada; Z. Hussain, London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ontario, Canada; C. Lee, St. Joseph's Hospital, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada; S. Poutanen, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada; F. Chan, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; M. Laverdiere, Hopital Maisonneuve-Rosemont, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; V. Loo, Montreal General Hospital and Royal Victoria Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada; R. Davidson, Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada).

Financial support for the CANWARD study was provided in part by Abbott Laboratories Ltd., Janssen-Ortho Inc., Pfizer Canada Inc., TaiGen Biotechnology Co. Ltd., and Wyeth Canada Inc. Nemonoxacin powder was kindly provided by TaiGen Biotechnology Co. Ltd.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 September 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson, M. I., and A. P. MacGowan. 2003. Development of the quinolones. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51(Suppl. 1):1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry, A. L., P. C. Fuchs, and S. D. Brown. 2001. In vitro activities of three nonfluorinated quinolones against representative bacterial isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1923-1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2006. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. M7-A7. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 4.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Eighteenth informational supplement. M100-S18. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 5.Golding, G., J. Campbell, D. Spreitzer, J. Veyhl, K. Surynicz, and A. Simor. 2008. A preliminary guideline for the assignment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to a Canadian pulsed-field gel electrophoresis epidemic type using spa typing. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 19:273-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu, C. H., Y. M. Chen, and C. P. Chow. 2008. Systemic hypersensitivity of nemonoxacin, a novel potent broad-spectrum non-fluorinated quinolone, in guinea pigs, abstr. F1-2055. Abstr. Joint Meet. 48th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. and 46th Annu. Meet. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am.

- 7.Hsu, C. H., L. Lin, R. Leunk, and D. Reichart. 2008. In vivo efficacy of nemonoxacin in a mouse protection model, abstr. B1-1005. Abstr. Joint Meet. 48th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemotherapy and 46th Annu. Meet. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am.

- 8.Hsu, C. H., L. Lin, R. Leunk, and D. Reichart. 2008. In vivo efficacy of nemonoxacin in a mouse pulmonary infection model, abstr. B-056. Abstr. Joint Meet. 48th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. and 46th Annu. Meet. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am.

- 9.Lai, C. C., C. K. Tan, S. H. Lin, C. H. Liao, C. H. Chou, H. L. Hsu, Y. T. Huang, and P. R. Hsueh. 2009. Comparative in vitro activities of nemonoxacin, doripenem, tigecycline and 16 other antimicrobials against Nocardia brasiliensis, Nocardia asteroides and unusual Nocardia species. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulvey, M. R., L. Chui, J. Ismail, L. Louie, C. Murphy, N. Chang, and M. Alfa. 2001. Development of a Canadian standardized protocol for subtyping methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3481-3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nichol, K. A., M. McCracken, M. R. DeCorby, K. Thompson, M. R. Mulvey, J. A. Karlowsky, D. J. Hoban, and G. G. Zhanel. 2009. Comparison of community-associated and health care-associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Canada: results from CANWARD 2007. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 20:31A-36A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pankuch, G. A., K. Kosowska-Shick, P. McGhee, C. R. King, and P. Appelbaum. 2008. Comparative antistaphylococcal activity of nemonoxacin, a novel broad-spectrum quinolone, abstr. C1-189. Abstr. Joint Meet. 48th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. and 46th Annu. Meet. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am.

- 13.Peterson, L. R. 2001. Quinolone molecular structure-activity relationships: what we have learned about improving antimicrobial activity. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:S180-S186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simor, A., D. Boyd, A. Louie, A. McGeer, M. R. Mulvey, and B. Willey. 1999. Characterization and proposed nomenclature of epidemic strains of MRSA in Canada. Can. J. Infect. Dis. 10:333-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan, C. K., C. C. Lai, C. H. Liao, C. H. Chou, H. L. Hsu, Y. T. Huang, and P. R. Hsueh. 2009. Comparative in vitro activities of the new quinolone nemonoxacin (TG-873870), gemifloxacin and other quinolones against clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:428-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Rensburg, D. J., R. P. Perng, L. Lin, and H. Zhang. 2008. Efficacy and safety of nemonoxacin versus levofloxacin for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, abstr. L-678. Abstr. Joint Meet. 48th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. and 46th Annu. Meet. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am.

- 17.Wright, D. H., G. H. Brown, M. L. Peterson, and J. C. Rotschafer. 2000. Application of fluoroquinolone pharmacodynamics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:669-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhanel, G. G., J. A. Karlowsky, M. DeCorby, K. Nichol, A. Wierzbowski, P. J. Baudry, P. Lagace-Wiens, A. Walkty, F. Schweizer, H. Adam, M. McCracken, M. R. Mulvey, and D. J. Hoban. 2009. Prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant pathogens in Canadian hospitals: results of the Canadian Ward Surveillance Study (CANWARD 2007). Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 20:9A-19A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]