Abstract

Comparison of the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) in 42 Mycoplasma bovis clinical isolates revealed amino acid substitutions at both GyrA (position 83) and ParC (position 84) in 10/11 enrofloxacin-resistant strains. The mutation present in the parC QRDR was discriminative for enrofloxacin resistance by parC PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism. Comparison of molecular profiles by insertion sequence typing suggests that the currently prevalent enrofloxacin-resistant M. bovis strain evolved by selection under field conditions from one of the susceptible strains.

Fluoroquinolones are broad-spectrum antimicrobials highly effective for treatment of a variety of clinical and veterinary infections, including Mycoplasma bovis infection in cattle. Their antibacterial activity is due mainly to inhibition of DNA replication. Resistance can arise spontaneously due to point mutations that result in amino acid substitutions within the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) of DNA gyrase subunits GyrA and GyrB and/or topoisomerase IV subunits ParC and ParE (5, 11, 12).

In the present study, 91 M. bovis strains isolated in Israel from cattle with pneumonia (82), bovine respiratory disease (3), mastitis (3), or arthritis (3) were examined for enrofloxacin susceptibility. These strains include 34 isolates for which geographic origin, clinical condition, and susceptibility profiles have previously been described (8) and an additional 57 M. bovis strains isolated in 2006 (26), 2007 (5), and 2008 (26) that were not characterized for susceptibility.

In vitro susceptibility for enrofloxacin (Vetranal) was determined by the broth microdilution method, according to the guidelines recommended by Hannan (10), as previously described (8). M. bovis was considered susceptible to enrofloxacin when the MIC was ≤0.25 μg/ml, intermediately susceptible with a MIC of 0.5 to 1 μg/ml, and resistant when the MIC was ≥2 μg/ml, according to the CLSI criteria for veterinary pathogenic bacteria (other than mycoplasmas) in cattle (19).

M. bovis genomic DNA was extracted from 10-ml logarithmic-phase broth cultures using the DNA isolation kit for cell/tissue (Roche). Amplification of the QRDR encoding regions was done with gene-specific primers designed on the basis of the sequences of the following genes in M. bovis strain PG45: gyrA (gyrA-F, 5′-GACGAATCATCTAGCGAG-3′, and gyrA-R, 5′-GCCTTCTAGCATCAAAGTAGC-3′); gyrB (gyrB-F, 5′-CCTTGTTGCCATTGTGTC-3′, and gyrB-R, 5′-CCATCGACATCAGCATCAGTC-3′); parE (parE-F, 5′-GGTACTCCTGAAGCTAAAAGTGC-3′, and parE-R, 5′-GAATATGTGCGCCATCAG-3′); and parC (parC-F, 5′-GAGCAACAGTTAAACGATTTG-3′, and parC-R, 5′-GGCATAACAACTGGCTCTT-3′). PCRs were performed in 50 μl ready-mix PCR master mix (ABGene, Surrey, United Kingdom) with 30 pmol/μl of each primer (Sigma) and about 100 ng DNA in an MJ Research PT200 thermocycler (Waltham, MA) as follows: 3 min at 95°C; 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s; and 72°C for 10 min. The amplicons of 531 bp, 555 bp, 488 bp, and 502 bp, containing the QRDRs of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE, respectively, were purified from the gel using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Germany). Sequencing was performed at the DNA Sequencing Unit, Weizmann Institute (Rehovot, Israel), utilizing the Applied Biosystems DNA sequencer with the ABI BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequence editing, consensus, and alignment construction were performed using Lasergene software, version 5.06/5.51, 2003 (DNAStar, Inc., Madison, WI), and the ExPASy Molecular Biology server (available at http://expasy.org/).

Initially, molecular characterization of the QRDRs of GyrA, GyrB, ParC, and ParE was performed for 34 previously described (8) clinical isolates of M. bovis differing in the levels of susceptibility to enrofloxacin (Table 1, numbers 1 to 34). Most nucleotide (nt) substitutions within the gyrA-amplified products were synonymous with only one substitution (C to T), resulting in an amino acid change from Ser to Phe at position 83 (Escherichia coli numbering). With two exceptions, this substitution appeared in all intermediate and resistant M. bovis strains tested (Table 1, numbers 24 to 38 and 40 to 42). However, three M. bovis isolates with MICs in the susceptible range (0.32 μg/ml) possessed Phe, and one strain with an intermediate MIC (0.63 μg/ml) contained Ser at position 83 (Table 1, numbers 20 to 22 and 23, respectively).

TABLE 1.

MIC and molecular characterization of the QRDR in clinical isolates of M. bovis

| Isolate no. | Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a | Amino acid change in QRDRsb |

IS major type (ISMbov3/ISMbov4)d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GyrA (position 83) | ParC (position 84) | ||||

| PG45 | 0.16 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | NT | |

| 1 | 330 | 0.08 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | I (A/1) |

| 2 | 861 | 0.08 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | II (B/2) |

| 3 | 8998 | 0.08 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | NT |

| 4 | 2670 | 0.08 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | III (C/3) |

| 5 | 111-2 | 0.16 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | IV (D/4) |

| 6 | 3222 | 0.16 | Ser(S) | Asp (D) | V (E/5) |

| 7 | 4554 | 0.16 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | VI (A/6) |

| 8 | 5180 | 0.16 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | NT |

| 9 | K | 0.16 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | NT |

| 10 | 2E | 0.16 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | NT |

| 11 | 2D | 0.16 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | NT |

| 12 | H | 0.16 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | NT |

| 13 | 9249 | 0.16 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | VII (F/2) |

| 14 | 6099 | 0.16 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | NT |

| 15 | 9603 | 0.16 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | VIII (G/2) |

| 16 | 476-2 | 0.16 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | NT |

| 17 | 6226 | 0.32 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | NT |

| 18 | 8934 | 0.32 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | NT |

| 19 | 7910 | 0.32 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | IX (F/7) |

| 20 | 1416 | 0.32 | Phe (F) | Asp (D) | X (H/2) |

| 21 | 7043 | 0.32 | Phe (F) | Asp (D) | X (H/2) |

| 22 | 2029 | 0.32 | Phe (F) | Asp (D) | X (H/2) |

| 23 | 170 | 0.63 | Ser (S) | Asp (D) | NT |

| 24 | 77 | 0.63 | Phe (F) | Asp (D) | X (H/2) |

| 25 | 3179 | 0.63 | Phe (F) | Asp (D) | X (H/2) |

| 26 | 2643 | 1.25 | Phe (F) | Asp (D) | X (H/2) |

| 27 | 5848 | 1.25 | Phe (F) | Asp (D) | X (H/2) |

| 28 | 2458 | 1.25 | Phe (F) | Asp (D) | X (H/2) |

| 29 | 3036 | 1.25 | Phe (F) | Asp (D) | X (H/2) |

| 30 | 3374 | 1.25 | Phe (F) | Asp (D) | X (H/2) |

| 31 | 1306 | 1.25 | Phe (F) | Asp (D) | X (H/2) |

| 32 | 1972 | 2.5 | Phe (F) | Asn (N) | XI (H/8) |

| 33 | 3181 | 2.5 | Phe (F) | Asn (N) | X (H/2) |

| 34 | 8830 | 5 | Phe (F) | Asn (N) | X (H/2) |

| 35 | 4243c | 2.5 | Phe (F) | Asn (N) | VII (F/2) |

| 36 | 1665c | 2.5 | Phe (F) | Asn (N) | XII (A/4) |

| 37 | 4241c | 2.5 | Phe (F) | Asn (N) | VII (F/2) |

| 38 | 0523c | 2.5 | Phe (F) | Asn (N) | VII (F/2) |

| 39 | 4925c | 2.5 | Ser (S) | Asn (N) | XIII (A/7) |

| 40 | 9771c | 5 | Phe (F) | Asn (N) | X (H/2) |

| 41 | 0962c | 5 | Phe (F) | Asn (N) | XIV (I/7) |

| 42 | 4879c | 5 | Phe (F) | Asn (N) | XV (I/4) |

MIC was obtained by broth microdilution method.

E. coli numbering. Amino acid (nt) changes from Ser to Phe at position 83 in the GyrA QRDRs and from Asn to Asp at position 84 in the ParC QRDRs are shown in bold.

Enrofloxacin-resistant M. bovis strains identified by parC PCR-RFLP analysis.

NT, not tested.

The predicted amino acid sequence of the GyrB QRDR revealed one nonsynonymous substitution (position 440, Val/Ile) in four susceptible M. bovis strains: 861, 8998, 2670, and 111-2 (data not shown). In addition, some diversity in the non-QRDR region of the gyrB amplicon, unrelated to susceptibility, was determined (data not shown). No amino acid substitutions were found within the QRDR of ParE.

Comparison of the ParC QRDRs revealed the presence of an Asn/Asp substitution at position 84, resulting from the change of nt G to A at position 265 of the parC amplicon (corresponding to positions 250 and 283 of the E. coli and M. bovis parC genes, respectively) in all M. bovis enrofloxacin-resistant strains and only in these strains (Table 1, numbers 32 to 34). Restriction enzyme site analysis revealed that this G-to-A nt substitution generates the restriction site for PsiI (T/TATAA) at nt 262 to 266. Restriction of the amplicon of resistant strains with PsiI (parC PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism [RFLP]) yielded the predicted 262- and 226-bp fragments that are readily distinguished in a standard agarose gel from the 488-bp nonrestricted amplicon of sensitive M. bovis field isolates (data not shown).

Analysis of genomic DNAs of the cohort of M. bovis clinical isolates with unknown enrofloxacin susceptibility by parC PCR-RFLP resulted in 8/57 strains restricted by parC PsiI (Table 1, numbers 35 to 42) and possessing the same amino acid substitutions observed with the three previously identified enrofloxacin-resistant strains (Table 1, numbers 32 to 34). In parallel, preliminary screening of the cohort of 57 M. bovis clinical isolates for enrofloxacin resistance was performed on agar containing enrofloxacin at a concentration above the susceptibility cutoff value, according to recommendations for the agar dilution method (10). For the test, 5-μl aliquots of each M. bovis culture, containing 104 to 105 color-changing units/ml, were spotted according to a standard pattern on an agar plate containing 2.5 μg/ml of enrofloxacin or no antibiotic. After 5 days of incubation at 37°C in the presence of CO2, growth was determined microscopically. Two strains with MICs determined in the microbroth test (strain 8830 with a MIC of 5 μg/ml and strain 330 with a MIC of 0.08 μg/ml) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Comparison of growth levels between plates with and without antibiotics identified 8/57 isolates that grew in the presence of 2.5 μg/ml of enrofloxacin; the same isolates were restricted with PsiI in the parC PCR-RFLP test (Table 1, numbers 35 to 42, respectively). The MICs of these isolates were 2.5 to 5 μg/ml by the conventional microbroth method. According to criteria of the CLSI (19), all eight M. bovis strains containing a PsiI site within the QRDR of the parC amplicon were resistant to enrofloxacin (Table 1, numbers 35 to 42).

The genetic variability of M. bovis isolates in this study was assessed by insertion sequence (IS) hybridization profiles, as previously described (15, 18). Primers (Mbov-3-F, 5′-GGTGGTTTGATATACAAAACT-3′, and Mbov-3-R, 5′-GGACGAAGAGATAATTTACC-3′; and Mbov-4-F, 5′-CCTAGCACTGGCGAAATA-3′, and Mbov-4-R, 5′-CCTCTAATGAAAGGTCAAC-3′) were used to amplify M. bovis PG45 genomic fragments corresponding to ISMbov3 and ISMbov4 elements (15, 23). The amplification parameters were 95°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 52°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and 72°C for 10 min. The IS-specific probes were labeled by digoxigenin-11-dUTP using the PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions and were used in Southern blot analysis of genomic DNAs digested with 10 U HindIII restriction enzyme (Fermentas). IS pattern analysis was by visual comparison using exposed X-ray film (Fujifilm). Isolates were considered identical if the major band patterns were the same with both probes.

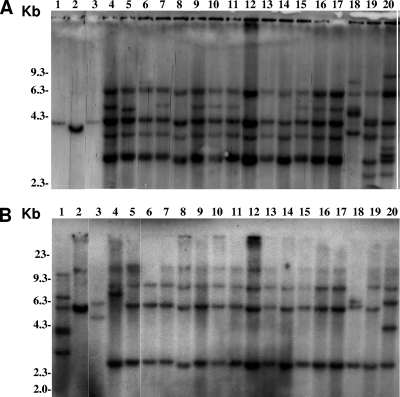

Overall, among the 33 representative M. bovis field isolates tested, nine ISMbov3-related types, arbitrarily designated A through I, and eight ISMbov3-related types, designated 1 to 8, were distinguished, respectively (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Fifteen major molecular types (I to XV) were identified, based on the composite of the ISMbov3 and ISMbov4 patterns (Table 1). Five molecular types (XI to XV) were uniquely present in the cohort of M. bovis enrofloxacin-resistant strains. However, the predominant IS hybridization profile was X (H/2), present in 13/33 M. bovis strains, including two isolates susceptible to enrofloxacin, eight isolates with intermediate susceptibility, and three resistant strains (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Representative IS profiles of M. bovis enrofloxacin-resistant and -susceptible strains. Hybridization patterns obtained by ISMbov3 (A) and ISMbov4 (B) elements are presented. Molecular size markers are indicated on the left of each panel. M. bovis strains used in lanes 1 to 20 are 330, 111-2, 4554, 1972, 3181, 7043, 5848, 3179, 1306, 8830, 3374, 1416, 2029, 77, 2458, 3036, 2643, 81, 9603, and 7910. The predominant IS hybridization profile X (H/2), found in three, eight, and three M. bovis strains that were resistant, intermediately susceptible, and susceptible, respectively, to enrofloxacin, can be seen in lanes 5 to 17.

The data presented here suggest that a change in GyrA (at position 83, Ser to Phe) is sufficient to achieve an intermediate level of susceptibility to fluoroquinolone, but a concurrent modification in the ParC protein (at position 84, Asp to Asn) is required for resistance. Previous studies have reported hot spots for amino acid substitutions at GyrA Ser-83 and ParC Asp-84 in other bacteria and mycoplasmas (2, 3, 7, 14, 16, 22, 25).

Today, in vitro susceptibility testing of mycoplasma isolates is not routinely performed. Conventional antimicrobial susceptibility testing by broth microdilution, agar dilution, or Etest methods (9, 10) requires isolation of mycoplasmas in pure culture, requiring 2 to 3 weeks. In this context, the development of a rapid genetic assay for detection of mycoplasma resistance may be attractive. Several studies have described the use of different genetic methods, such as PCR-RFLP analysis (1, 6, 13, 20), PCR-oligonucleotide ligation (4), and a real-time PCR assay (21, 24), for rapidly screening key gene mutations associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in various microorganisms. However, the only molecular/genetic methods reported for mycoplasmas are for detection of macrolide resistance, and nothing has been reported for fluoroquinolones (17, 26). The PCR-RFLP described here is a simple and rapid method for the detection of fluoroquinolone-resistant M. bovis strains and can be carried out as a routine assay in a diagnostic laboratory.

Results of the molecular typing suggest that the currently prevalent enrofloxacin-resistant M. bovis strain evolved by selection under field conditions from one of the susceptible strains. However, this apparently was not a unique occurrence, as evidenced by the presence of resistant strains with different IS molecular patterns.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to M. J. Calcutt and K. Wise (Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, University of Missouri—Columbia, Columbia) as well as to B. A. Methe (J. Craig Venter Institute, Rockville, MD) for providing nucleotide sequences of the gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes of M. bovis strain PG45.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 August 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso, R., M. Galimand, and P. Courvalin. 2004. An extended PCR-RFLP assay for detection of parC, parE and gyrA mutations in fluoroquinolone-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:682-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bebear, C., J. Renaudin, A. Charron, H. Renaudin, B. de Barbeyrac, T. Schaeverbeke, and C. Bebear. 1999. Mutations in the gyrA, parC, and parE genes associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Mycoplasma hominis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:954-956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bébéar, C. M., H. Renaudin, A. Charron, M. Clerc, S. Pereyre, and C. Bébéar. 2003. DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV mutations in clinical isolates of Ureaplasma spp. and Mycoplasma hominis resistant to fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3323-3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bui, M.-H., G. G. Stone, A. M. Nilius, L. Almer, and R. K. Flamm. 2003. PCR-oligonucleotide ligation assay for detection of point mutations associated with quinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1456-1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, F. J., and H. J. Lo. 2003. Molecular mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 36:1-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deguchi, T., M. Yasuda, M. Nakano, S. Ozeki, T. Ezaki, S. Maeda, I. Saito, and Y. Kawada. 1996. Rapid detection of point mutations of the Neisseria gonorrhoeae gyrA gene associated with decreased susceptibilities to quinolones. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2255-2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffy, L., J. Glass, G. Hall, R. Avery, R. Rackley, S. Peterson, and K. Waites. 2006. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Ureaplasma parvum in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1590-1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerchman, I., S. Levisohn, I. Mikula, and I. Lysnyansky. 2009. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility Mycoplasma bovis isolated in Israel from local and imported cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 137:268-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerchman, I., I. Lysnyansky, S. Perk, and S. Levisohn. 2008. In vitro susceptibilities to fluoroquinolones in current and archived Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae isolates from meat-type turkeys. Vet. Microbiol. 131:266-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hannan, P. C. 2000. Guidelines and recommendations for antimicrobial minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing against veterinary mycoplasma species. Vet. Res. 31:373-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooper, D. C. 1998. Bacterial topoisomerases, anti-topoisomerases, and anti-topoisomerase resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:S54-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins, K. L., R. H. Davies, and E. J. Threlfall. 2005. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli and Salmonella: recent developments. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 25:358-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ip, M., S. S. L. Chau, F. Chi, A. Qi, and R. W. M. Lai. 2006. Rapid screening of fluoroquinolone resistance determinants in Streptococcus pneumoniae by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism and single-strand conformational polymorphism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:970-975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Carrou, J., M. Laurentie, M. Kobisch, and A. V. Gautier-Bouchardon. 2006. Persistence of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae in experimentally infected pigs after marbofloxacin treatment and detection of mutations in the parC gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1959-1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lysnyansky, I., M. J. Calcutt, I. Ben-Barak, Y. Ron, S. Levisohn, B. A. Methe, and D. Yogev. 2009. Molecular characterization of newly-identified IS3, IS4 and IS30 insertion sequence-like elements in Mycoplasma bovis and their possible roles in genome plasticity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 294:172-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lysnyansky, I., I. Gerchman, S. Perk, and S. Levisohn. 2008. Molecular characterization and typing of enrofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Avian Dis. 52:685-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuoka, M., M. Narita, N. Okazaki, H. Ohya, T. Yamazaki, K. Ouchi, I. Suzuki, T. Andoh, T. Kenri, Y. Sasaki, A. Horino, M. Shintani, Y. Arakawa, and T. Sasaki. 2004. Characterization and molecular analysis of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae clinical isolates obtained in Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4624-4630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miles, K., L. McAuliffe, A. Persson, R. D. Ayling, and R. A. Nicholas. 2005. Insertion sequence profiling of UK Mycoplasma bovis field isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 107:301-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NCCLS. 2002. Development of in vitro susceptibility testing criteria and quality control parameters for veterinary antimicrobial agents; approved guideline M37-A2. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 20.Ozeki, S., T. Deguchi, M. Nakano, T. Kawamura, Y. Nishino, and Y. Kawada. 1997. Development of a rapid assay for detecting gyrA mutations in Escherichia coli and determination of incidence of gyrA mutations in clinical strains isolated from patients with complicated urinary tract infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2315-2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page, S., F. Vernel-Pauillac, O. O'Connor, S. Bremont, F. Charavay, P. Courvalin, C. Goarant, and S. Le Hello. 2008. Real-time PCR detection of gyrA and parC mutations in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4155-4158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reinhardt, A. K., C. M. Bébéar, M. Kobisch, I. Kempf, and A. V. Gautier-Bouchardon. 2002. Characterization of mutations in DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV involved in quinolone resistance of Mycoplasma gallisepticum mutants obtained in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:590-593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas, A., A. Linden, J. Mainil, D. F. Bischof, J. Frey, and E. M. Vilei. 2005. Mycoplasma bovis shares insertion sequences with Mycoplasma agalactiae and Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC: evolutionary and developmental aspects. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 245:249-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vernel-Pauillac, F., V. Falcot, D. Whiley, and F. Merien. 2006. Rapid detection of a chromosomally mediated penicillin resistance-associated ponA mutation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae using a real-time PCR assay. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 255:66-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vicca, J., D. Maes, T. Stakenborg, P. Butaye, F. Minion, J. Peeters, A. de Kruif, A. Decostere, and F. Haesebrouck. 2007. Resistance mechanism against fluoroquinolones in Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae field isolates. Microb. Drug Resist. 13:166-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolff, B. J., W. L. Thacker, S. B. Schwartz, and J. M. Winchell. 2008. Detection of macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae by real-time PCR and high resolution melt analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3542-3549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]