Abstract

Many currently available diagnostic tests for typhoid fever lack sensitivity and/or specificity, especially in areas of the world where the disease is endemic. In order to identify a diagnostic test that better correlates with typhoid fever, we evaluated immune responses to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (serovar Typhi) in individuals with suspected typhoid fever in Dhaka, Bangladesh. We enrolled 112 individuals with suspected typhoid fever, cultured day 0 blood for serovar Typhi organisms, and performed Widal assays on days 0, 5, and 20. We harvested peripheral blood lymphocytes and analyzed antibody levels in supernatants collected on days 0, 5, and 20 (using an antibody-in-lymphocyte-supernatant [ALS] assay), as well as in plasma on these days. We measured ALS reactivity to a serovar Typhi membrane preparation (MP), a formalin-inactivated whole-cell preparation, and serovar Typhi lipopolysaccharide. We measured responses in healthy Bangladeshi, as well as in Bangladeshi febrile patients with confirmed dengue fever or leptospirosis. We categorized suspected typhoid fever individuals into different groups (groups I to V) based on blood culture results, Widal titer, and clinical features. Responses to MP antigen in the immunoglobulin A isotype were detectable at the time of presentation in the plasma of 81% of patients. The ALS assay, however, tested positive in all patients with documented or highly suspicious typhoid, suggesting that such a response could be the basis of improved diagnostic point-of-care-assay for serovar Typhi infection. It can be important for use in epidemiological studies, as well as in difficult cases involving fevers of unknown origin.

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (serovar Typhi) is the cause of typhoid fever, an illness that affects over 20,000,000 individuals worldwide each year, killing over 200,000 (5, 8, 16). The largest burden of typhoid fever is borne by impoverished individuals in resource-poor areas of the world. Serovar Typhi is a human-restricted invasive enteric pathogen which, after ingestion, crosses the intestinal mucosa, is taken up by gut-associated lymphoreticular tissues, and enters the systemic circulation. Both mucosal and systemic host immune responses are stimulated after infection. Serovar Typhi is an intracellular pathogen, and antibody and cell-mediated immune responses occur after infection or immunization with live oral attenuated typhoid vaccines (10, 25, 34).

Diagnostic tests for typhoid fever often lack sensitivity and/or specificity, especially in areas of the world that are endemic for typhoid fever, where clinically distinguishing typhoid fever from other febrile illnesses is difficult (5, 17, 39). Microbiologic culturing of blood is approximately 30 to 70% sensitive, with the highest sensitivity being associated with an absence of prior use of antibiotics and the culturing of larger volumes of blood, features that complicate this mode of diagnosis in young children (5, 6, 8, 36). Microbiologic culturing of bone marrow aspirates is more sensitive than blood but often clinically impractical (1, 11, 12). Serum Widal assay titers are often nonspecific in endemic settings and are of limited value unless titers are markedly elevated or are analyzed for changes from acute to convalescent phases of illness (18, 33, 38). Molecular diagnostic assays including PCR are promising, but issues of practicality, contamination, and quality control have limited their use in many resource-poor areas of the world (14).

Since serovar Typhi interacts with both the mucosal and the systemic immune systems, we were interested to determine whether analyses of mucosal immune responses would give improved insight into this human-restricted infection. Activated mucosal lymphocytes migrate from intestinal tissue and circulate within peripheral blood before rehoming to mucosal tissues (20, 31). This migration peaks 1 to 2 weeks after intestinal infection and may be measured by using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in an antibody-secreting cell (ASC) assay (19, 26) or in supernatants recovered from harvested PBMC (the “antibody in lymphocyte supernatant” [ALS] assay) (7, 31). Although ALS and ASC responses have previously been measured after immunization with oral live attenuated typhoid vaccines, detailed analyses of ALS or ASC responses in individuals with wild-type typhoid fever are lacking (21, 24). In order to gain further insight into mucosal immune responses during wild-type serovar Typhi infection, we undertook a study to characterize the serum and ALS responses to serovar Typhi among individuals with suspected typhoid fever in Bangladesh.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants and specimens.

Individuals 3 to 59 years of age who presented to the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B)-Dhaka Hospital or Dhaka Medical College Hospital with fever of 3 to 7 days duration (≥39°C), without an obvious focus of infection and lacking an alternate diagnosis, were eligible for enrollment. Because of the widespread availability of antibiotics in Bangladesh, prior use of antibiotics was not an exclusion criterion for the present study. Individuals were queried regarding headache, abdominal discomfort or pain, constipation, diarrhea, vomiting, myalgia, and loss of appetite and were assessed for lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, rash, rose spots on the lower chest and upper abdomen, coated tongue, and relative bradycardia. We collected venous blood (5 ml from children <5 years old, and 10 ml from all others) at enrollment (day 0) and 5 and 20 days later. For children <5 years of age, 3 ml of day 0 blood was microbiologically cultured; for older individuals, 5 ml of day 0 blood was microbiologically cultured. All patients suspected of having typhoid fever were initially treated with oral ciprofloxacin (10 mg/kg of body weight twice a day, up to 500 mg twice daily) or cefixime (4 mg/kg of body weight twice a day, up to 200 mg twice daily) or injectable ceftriaxone (100 mg/kg of body weight, up to 1 g/day), and this was continued for up to 14 days at the discretion of the attending physician.

We also collected single blood and stool samples from healthy Bangladeshi adults (n = 32) who denied any illness, fever, or diarrhea in the preceding 3 months and were of the same socioeconomic status as the patients (30). We also analyzed immune responses using previously collected acute and convalescent-phase serum specimens from patients with culture-confirmed cholera (n = 5) (2) and febrile illnesses due to serologically confirmed dengue (n = 5) and leptospirosis (n = 5) (23). The study and all sample collections and analyses were approved by the ethical and research review committees of the ICDDR,B.

Diagnosis of typhoid fever by blood culture and Widal test.

Microbiological culturing of day 0 blood was performed by using a BacT/Alert automated system, and positive bottles were subcultured on MacConkey agar. Colonies were identified by standard biochemical tests and by reaction with Salmonella-specific antisera (35). Antimicrobial sensitivity was assessed by the disc diffusion method on a Mueller-Hinton agar plate with Oxoid disks (Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom) containing ampicillin, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim, cefixime, and gentamicin (3). Widal assays were performed using twofold dilutions of plasma by a slide agglutination test with typhoid-specific antigens (Omega Diagnostics, Scotland, United Kingdom). A titer of ≥320 for serovar Typhi H and/or O antigen was considered a positive response (27, 28).

Isolation of PBMC and collection of plasma and ALS specimens.

We diluted heparinized blood in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 mM [pH 7.2]) and isolated PBMC by density gradient centrifugation on Ficoll-Isopaque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). We resuspended isolated PBMC to a concentration of 107cells/ml in RPMI complete medium RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Ogden, UT), 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 100 mM pyruvate, and 200 mM l-glutamine (Gibco) (31). We incubated cells for 48 h at 37°C with 5% CO2, collected supernatants, and added a protease inhibitor solution as previously described (21, 31). Plasma and ALS specimens were tested for typhoid-specific antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Serovar Typhi antigens used in the study.

In the present study, we used a serovar Typhi lipopolysaccharide (LPS) preparation, a formalin inactivated whole-cell (WC) preparation, and a membrane preparation (MP). LPS was prepared from a wild-type clinical isolate of serovar Typhi (strain ST004) isolated in Bangladesh, using a previously reported phenol-water extraction procedure, followed by enzyme treatment with proteinase K, DNase, and RNase and ultracentrifugation (9, 13). For preparation of WC extract, we cultured the wild-type clinical isolate on nutrient agar plates and harvested into PBS. After addition of formalin (0.5%) and vortexing, we placed the cell suspension in a petri dish and incubated overnight at 37°C and confirmed the absence of viability by streaking an aliquot on a MacConkey agar plate, followed by additional overnight incubation at 37°C. We adjusted the suspension to 10 ml with PBS, centrifuged for 8 min at 6,000 × g, washed once with PBS, and adjusted the optical density to 0.40 at 600 nm with PBS (∼1010 CFU/ml). We prepared MP antigen by using a previously described procedure (4). Briefly, we cultured the strain on sheep blood agar plates (n = 20) and harvested in Tris buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 5 mM MgCl2). We sonicated the mixture, centrifuged at 1,400 × g for 10 min, transferred the supernatant to fresh tubes, centrifuged at 14,900 × g for 30 min, suspended the pellet in 10 ml of Tris buffer, and determined the protein content by the Bio-Rad protein assay (37).

Detection of typhoid-specific antibodies in specimens by ELISA.

We assayed immunoglobulin A (IgA), IgG, and IgM isotype-specific antibody responses to LPS, WC, and MP by using ELISA. We coated microtiter plates (Nunc F; Nunc, Denmark) with 100 μl of LPS (2.5 μg/ml), WC (108 CFU/ml), and MP (2 μg/ml for plasma and 10 μg/ml for ALS) and blocked them with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS (29, 31). To detect antigen-specific responses, we added 100 μl of dilutions of plasma in PBS-Tween 0.1% bovine serum albumin (1:25 for IgA and IgM and 1:50 for IgG isotypes) or 100 μl (1:2 dilution for IgA) of ALS specimens to coated plates, which were then incubated for 90 min at 37°C. After a washing step with 0.05% PBS-Tween, we detected responses using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies to either human IgA, IgG (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) or IgM (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) (1:100 in PBS-Tween for IgA and IgM isotypes and 1:500 for IgG isotypes), developed plates with ortho-phenylene diamine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) in 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer and 0.1% hydrogen peroxide, and read the plates kinetically at 450 nm for 5 min at 19-s intervals as previously described (13). The maximal rate of optical density change was expressed as milli-optical density absorbance units per minute. To control among plates, readings of unknowns were divided by readings of an in-house pooled convalescent-phase standard sera of blood culture-confirmed typhoid patients, multiplied by 100, and expressed as ELISA units. A positive response was defined as being a value greater than two standard deviations (SD) above the geometric mean of healthy controls (32).

Statistical analysis.

We used SigmaStat (version3.1), Prism4, and SPSS (version 12.0 for Windows) for data management, analysis, and graphical presentation. Statistical evaluation of differences between groups was performed by using the Mann-Whitney U test, and evaluation of differences between study days in a group were performed by using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

RESULTS

Clinical and microbiological features in study subjects.

A total of 112 febrile subjects met the inclusion criteria and completed the follow-up appointments. The median age was 24 years, with a range of 3 to 59 years (see Table 1 for the clinical characteristics). Of these, 26 participants (23%) were positive by blood culture for serovar Typhi. Of the isolated serovar Typhi organisms, 16 (62%) were resistant to ampicillin, 16 (62%) were resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 24 (92%) were resistant to nalidixic acid, and 7 (27%) were resistant to ciprofloxacin, but all (100%) remained susceptible to gentamicin, cefixime, and ceftriaxone. Of the 112 study participants, 51(46%) reported antibiotic use prior to enrollment. Of the 26 blood culture-confirmed patients, 7 (27%) reported use of ciprofloxacin prior to presenting for medical care, and all 7 grew a serovar Typhi strain that was resistant to ciprofloxacin. Another 13 individuals (12%) had a negative blood culture, but a fourfold increase of Widal titer comparing either day 5 or day 20 blood samples to day 0 samples. Of these, 5 (38%) reported ciprofloxacin use before presenting for medical care. A total of 41 participants (37%) had a negative blood culture and did not have a fourfold change in Widal titer but did have at least one Widal titer of ≥320; of these, 18 (44%) reported use of ciprofloxacin before presenting for medical care. For the remaining 32 patients, 21 (66%) reported the use of any antibiotic before presenting for medical care. After enrollment, all patients were treated with antimicrobial agents, and 42 (38%) were hospitalized at the discretion of the attending physician. By day 5, 80 (71%) were afebrile, and by day 20 all were afebrile and well. There was no clinically evident intestinal hemorrhage or perforation, and no patient died.

TABLE 1.

Clinical features in study participants

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Baseline data | |

| Sample size | 112 |

| Median age in yr (25th, 75th percentile) | 24 (15, 30) |

| No. of patients with serovar Typhi in blood (%) | 26 (23.2) |

| Median maximum temp in °C (25th, 75th percentile) | 39 (39, 40) |

| Gender | |

| No. of males (%) | 52 (44) |

| No. of females (%) | 60 (54) |

| Clinical features | |

| Duration of fever in days at presentation (25th, 75th percentile) | 5 (4, 6) |

| No. of patients (%) with: | |

| Headache | 92 (82) |

| Abdominal pain | 62 (55) |

| Constipation | 38 (34) |

| Coated tongue | 63 (56) |

| Diarrhea | 17 (15) |

| Vomiting | 10 (9) |

| Rose spot | 10 (9) |

| Rash | 7 (6) |

| Median pulse/min (25th, 75th percentile) | 83 (74, 88) |

Subgrouping of study subjects for analyses.

Patients were categorized as follows. For comparison purposes, we grouped patients into a number of groups: group I, illness characterized with at least 3 days of high-grade fever and positive blood culture (n = 26); group II, compatible illness and a fourfold increase in Widal assay from day 0 baseline sample to convalescent period (n = 13); group III, compatible illness and a Widal titer of ≥320 (n = 41); group IV, an illness suspicious for clinical typhoid fever, but with a negative blood culture and Widal titer but with an anti-serovar Typhi IgA response in the ALS assay that was >2 SD above the geometric mean measured in healthy Bangladeshi controls (>10 ELISA units) (n = 14); and group V, patients with an illness compatible with enteric fever but negative by all tests (n = 18). There were no patients in more than one group. Healthy controls ranged in age from 24 to 35 years (median, 27 years).

Plasma antibody responses.

LPS-specific IgA and IgG responses were increased in patient groups I to III at all time points compared to healthy controls and compared to group V patients (P = 0.05 to <0.0001). In group IV patients, the LPS IgA response was increased at the acute stage only (Fig. 1). Compared to healthy controls, elevated LPS-IgM responses were seen at all time points and in all group I to IV patients (P ≤ 0.001; data not shown). Patients in group V did not have increased serovar Typhi LPS-specific responses at any time point in any antibody isotype.

FIG. 1.

LPS-specific IgA and IgG antibody responses in plasma specimens of different study groups on different study days. Groups: group I (Gr-I), blood culture positive; GrII, fourfold change in Widal; GrIII, Widal titer of ≥320; GrIV, negative culture and Widal but an anti-serovar Typhi IgA titer of >10 ELISA units in an ALS assay; GrV, all assays negative; HC, healthy controls. Geometric means with standard errors of the mean (SEM) are shown for day 0 (D0), day 5 (D5), and day 20 (D20). The responder rate was calculated with a cutoff of >GM plus two SD of healthy controls (55 and 119 ELISA units for IgA and IgG, respectively). Statistical difference compared to healthy controls: ***, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.005; *, P < 0.05. Statistical difference compared to GrV: φ, P < 0.05.

Anti-WC (killed WC bacterial preparation) IgA and IgG responses were seen in group I to III patients compared to healthy controls (Fig. 2). Group IV and V patients were not statistically different from healthy controls in either IgA or IgG anti-WC responses. Using a cutoff value of healthy control geometric mean plus 2 SD, 17/26 (65%) blood culture-positive patients had positive WC-specific IgA responses on day 0 blood, 23 (88%) on day 5 blood, and 14 (53%) on day 20 blood. Similarly, using a cutoff value of healthy control geometric mean plus 2 SD, 19/26 (73%) blood culture positive patients had positive anti-WC IgG responses on day 0 blood, 23 (88%) on day 5 blood, and 21 (81%) on day 20 blood. Significant anti-WC IgM responses compared to healthy controls were only seen in group I patients and were low in magnitude (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Formalin-inactivated Salmonella Typhi WC-specific IgA and IgG antibody responses in plasma specimen of different groups on different study days (see Fig. 1 legend for details). Geometric means with the SEM are shown for day 0 (D0), day 5 (D5), and day 20 (D20). The responder rate was calculated with a cutoff of >GM plus two SD of healthy controls (59 and 114 ELISA units for IgA and IgG, respectively). Statistical difference compared to healthy controls: ***, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.005; *, P < 0.05. Statistical difference compared to GrV: φ, P < 0.05.

MP-specific IgA responses were seen at presentation in group I to IV patients and at presentation and at later time points in group I to III patients compared to healthy controls (Fig. 3). Using a cutoff value of healthy control geometric mean plus two SD, 21/26 (81%) blood culture-positive patients had positive anti-MP IgA responses at the time of presentation (day 0). Of the 13 patients in group II, 8 (58%) were also positive for MP-IgA responses at presentation. Of those in group III, 18/41 (43%) patients were positive for MP-IgA responses on study day 0; 22/41 (54%) were positive on day 5, and 14/41 (44%) were positive on day 20. The MP IgG responses were only different from healthy controls in blood culture-confirmed (group I) patients at later time points and not in the day 0 plasma samples. The MP IgG responses were also not different from healthy controls in any other group at any other time point. Anti-MP IgM responses were not significantly different in any group at any time point compared to those measured in healthy controls (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

IgA and IgG antibody responses to Salmonella Typhi MP in plasma specimen of different study groups on different study days (see Fig. 1 legend for details). Geometric means with the SEM are shown for day 0 (D0), day 5 (D5), and day 20 (D20). Responder rates were calculated with a cutoff of >GM plus two SD of healthy controls (61 and 143 milliabsorbance units/min for IgA and IgG, respectively). Statistical difference compared to healthy controls: ***, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.005; *, P < 0.05. Statistical difference compared to GrV: φ, P < 0.05.

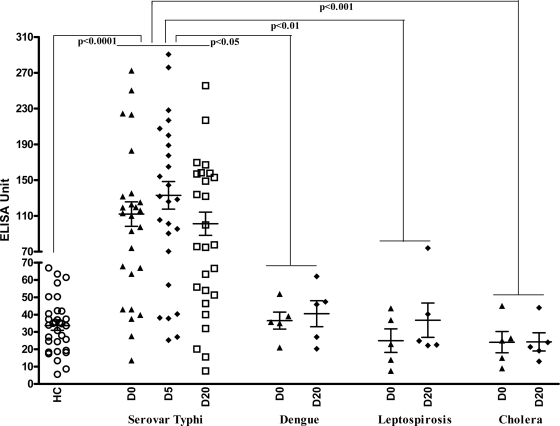

Comparison to reactivity in other illnesses using plasma.

We compared the MP IgA responses in serovar Typhi blood culture-positive individuals for MP IgA responses in plasma obtained from patients with other confirmed causes of febrile illness or enteric disease caused by V. cholerae O1 (Fig. 4). The MP IgA responses were elevated at all time points in serovar Typhi blood culture-confirmed patients compared to individuals with confirmed dengue, leptospirosis, and cholera and healthy controls (P ≤ 0.05 to 0.001). Focusing on blood drawn at the time of presentation (day 0 sample) and using a cutoff value of geometric mean of healthy controls plus two SD (61 ELISA units), a positive plasma anti-MP IgA on day 0 was ca. 76% sensitive and 87% specific for blood culture-confirmed serovar Typhi infection versus all comparison groups and 76% sensitive and 100% specific when blood culture-confirmed cases were compared to febrile cases caused by other illnesses (leptospirosis and dengue). When considering only those individuals with blood culture-confirmed serovar Typhi bacteremia (as a confirmed positive; n = 26), and all febrile and healthy controls (as confirmed negatives; n = 42), having a day 0 plasma MP-IgA level greater than 61 had a positive predictive value of 88%, and having a value of ≤60 was associated with a negative predictive value of 89%.

FIG. 4.

Dot plot of MP-specific IgA responses in plasma of patients with documented serovar Typhi bacteremia (n = 26), confirmed dengue (n = 5), leptospirosis (n = 5), cholera (n = 5), and healthy controls (HC; n = 32). The line represents the geometric mean, and bars represent the SEM for day 0 (D0) and convalescent stages day 5 (D5) and day 20 (D20).

Serovar Typhi-specific response in ALS specimens.

In order to more directly evaluate mucosal IgA responses, we also measured anti-serovar Typhi responses in ALS fluid of individuals with suspected typhoid. Compared to healthy controls, the anti-WC- and anti-MP-specific IgA responses in ALS fluid in group I to IV patients was significantly elevated at all time points, including in the sample collected at the time of presentation, with the MP-specific responses being of higher magnitude than the WC-specific responses (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

MP- and WC-specific IgA responses in ALS specimens of different study groups on different study days (see Fig. 1 legend for details). Geometric means with the SEM are shown for day 0 (D0), day 5 (D5), and day 20 (D20). Statistical difference compared to healthy controls: ***, P < 0.0001; **, P < 0.005; *, P < 0.05. Statistical difference compared to GrV: φ, P < 0.05.

Comparison of IgA responses in plasma and ALS specimens to MP at the acute stage of disease (day 0).

We compared anti-MP IgA responses in ALS and plasma in our different groups of patients in acute-phase samples collected at the time of presentation (Table 2). Defining a positive response as being greater than two SD above the geometric mean of healthy controls (≥61 ELISA units, plasma; >10 ELISA units, ALS), 21/26 (81%) of group I and 8/13 (58%) of group II patients had positive plasma responses on day 0, and 100% of both groups had positive ALS responses. Moreover, 18/41 (43%) group III patients with a Widal titer of ≥320 were positive in plasma, and 70% were positive in ALS. Of the remaining 32 patients, 14 (44%) had a positive ALS response, and of these 9 (28%) were also positive in plasma.

TABLE 2.

MP specific IgA responses in plasma and ALS specimens at the acute stage of diseasea

| Group | Characteristics | Sample size | IgA response (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | ALS | |||

| I | Blood culture positive | 26 | 21 (81) | 26 (100) |

| II | Fourfold Widal titer change | 13 | 8 (58) | 13 (100) |

| III | ≥320 Widal titer | 41 | 18 (43) | 29 (70) |

| IV | Culture negative, Widal negative but a >10 ELISA unit ALS response | 14 | 4 (29) | 14 (100) |

| V | Culture negative, Widal negative and a ≤10 ELISA unit ALS response | 18 | 5 (28) | 0 (0) |

Analyses of specimens on study day 1 from patients subgrouped according to different clinical and immunological characteristics. Positive responses were calculated as >GM plus two standard deviations of healthy control results; plasma MP-IgA response cutoff, ≥61 ELISA units; ALS MP-IgA response cutoff, >10 ELISA units.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we characterized antibody responses in individuals with suspected enteric fever in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Definitive diagnosis of typhoid fever is problematic, complicating the application of any gold standard to our study. We therefore considered responses based on the key assays available in resource-poor areas of the world, blood culture positivity, and Widal serology, and grouped patients into those with definitive typhoid, an illness highly suspicious for typhoid and with a fourfold increase in Widal titer, and an illness that we characterized as possible typhoid (with a Widal titer of ≥320). We found serovar Typhi MP-specific IgA responses in the majority of individuals with confirmed and highly suspicious typhoid fever, suggesting that IgA responses could be used to evaluate individuals with a febrile illness compatible with typhoid.

We analyzed serovar Typhi-specific responses using three antigen preparations—LPS, WC, and a MP—and found that both IgG and IgA against LPS and WC were present across our characterized groups but that MP-specific responses were restricted to the IgA isotype (with the exception that blood cultured confirmed patients also had a positive IgG anti-MP responses). These results suggest that measurement of the MP IgA responses warrants further development as a diagnostic test for individuals with suspected typhoid. The MP includes many surface-exposed or associated serovar Typhi antigens, and whether sensitivity and specificity could be improved or decreased using a more refined preparation is currently unclear.

The presence of serovar Typhi responses in the IgA isotype may reflect the fact that Salmonella first enters epithelial cells of the intestinal tract, before being taken up by professional phagocytic cells, including macrophages. Although activation of systemic immune responses during Salmonella is well described, there are more limited data characterizing mucosal immune responses during wild-type serovar Typhi infection. Serum and salivary anti-serovar Typhi LPS IgA responses during wild-type infection have been previously reported (15), and ASC and ALS responses that measure transient presence of mucosal lymphocytes in peripheral circulation after intestinal activation have been reported in vaccinees receiving oral attenuated strains of serovar Typhi (21, 22, 24) but have not been previously described in individuals with wild-type infection. The ALS specimen that we have used to measure the responses are those derived from cells which have mucosal priming in the gut. These cells are detected in the peripheral circulation while they are rehoming back to the gut (20). The highest level of ALS response was seen during the early phase of disease, and this decreased at convalescence showing that the antigen-specific cells had decreased and hence the levels of antibodies that were being measured. For this reason, and to further characterize mucosal IgA responses during typhoid, we analyzed anti-serovar Typhi IgA responses in ALS fluid and found that anti-MP and anti-WC IgA responses were present and that anti-MP IgA responses were present in the ALS fluid in 100% of individuals with blood culture-confirmed typhoid, in 100% individuals with an illness highly suspicious for typhoid, and in 70% of individuals with possible typhoid fever in our study (a compatible illness and a Widal titer of ≥320). We were particularly intrigued by our observation that we could divide individuals with a negative blood culture and negative Widal titer into two groups: those with a positive serovar Typhi-specific IgA ALS response and those with a negative anti-serovar Typhi ALS IgA response. Whether this distinction reflects the presence or absence of active serovar Typhi infection is currently uncertain.

The ALS requires ex vivo culturing of recovered lymphocytes and, as such, may have limited clinical utility for direct development as a diagnostic assay in many resource-poor areas; however, we believe our ALS results suggest that serovar Typhi-specific IgA responses are detectable at the time of presentation for clinical care in all individuals with typhoid (confirmed cases) and that such an IgA response could be the basis of a point-of-care diagnostic assay. We also observed that a single measurement at the time of presentation of IgA in plasma reacting with the serovar Typhi MP had high positive and negative predictive values in this endemic setting, including when comparing responses in individuals with other febrile illnesses difficult to clinically distinguish from typhoid fever in endemic settings (leptospirosis and dengue). Whether these results could be improved upon by use of a purified antigen or amplification of reactivity is currently unknown.

Our study has a number of shortcomings. The absence of a gold standard for diagnosing typhoid means that we can only approximate response rates across our clinical groups. The fact that many of our patients received antibiotics prior to presenting for medical care likely affected their likelihood of blood culture positivity, as well as the host-pathogen interactions that could have occurred during infection, including antibody responses. We feel, however, that our study represents an accurate clinical representation of how individuals with enteric fever present in areas of endemicity, and our blood culture positivity rate of almost 30% supports our observation that many of these individuals did indeed have serovar Typhi infection. Although serovar Typhi infection can cause a range of illness, all individuals in the present study were ill enough to seek medical care, and all had a minimum of 3 days of high level fever (with a median of 5 days). Despite these shortcomings, our results suggest that an IgA response to serovar Typhi-specific antigens is present in the peripheral circulation of many individuals with serovar Typhi infection (documented or highly suspected) at the time of presenting for clinical care and that such a response of especially the ALS specimen could be the basis of improved diagnostic point-of-care-assay for typhoid and warrants further evaluation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the ICDDR,B and grants from the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI072599 [E.T.R.] and AI058935 [R.C.C. and S.B.C.]), a Training Grant in Vaccine Development from the Fogarty International Center (TW05572 [A.S., M.S.B., and F.Q.]), and Career Development Awards (K01) from the Fogarty International Center (TW007409 [J.B.H.] and TW07144 [R.C.L.]), and a Physician-Scientist Early Career Award from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (R.C.L.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 September 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akoh, J. A. 1991. Relative sensitivity of blood and bone marrow cultures in typhoid fever. Trop. Doctor 21:174-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asaduzzaman, M., E. T. Ryan, M. John, L. Hang, A. I. Khan, A. S. Faruque, R. K. Taylor, S. B. Calderwood, and F. Qadri. 2004. The major subunit of the toxin-coregulated pilus TcpA induces mucosal and systemic immunoglobulin A immune responses in patients with cholera caused by Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. Infect. Immun. 72:4448-4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Begum, Y. A., K. A. Talukder, G. B. Nair, S. I. Khan, A. M. Svennerholm, R. B. Sack, and F. Qadri. 2007. Comparison of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from surface water and diarrhoeal stool samples in Bangladesh. Can. J. Microbiol. 53:19-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhuiyan, T. R., F. Qadri, A. Saha, and A. M. Svennerholm. 2009. Infection by Helicobacter pylori in Bangladeshi children from birth to two years: relation to blood group, nutritional status, and seasonality. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 28:79-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks, W. A., A. Hossain, D. Goswami, K. Nahar, K. Alam, N. Ahmed, A. Naheed, G. B. Nair, S. Luby, and R. F. Breiman. 2005. Bacteremic typhoid fever in children in an urban slum, Bangladesh. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:326-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler, T., A. Islam, I. Kabir, and P. K. Jones. 1991. Patterns of morbidity and mortality in typhoid fever dependent on age and gender: review of 552 hospitalized patients with diarrhea. Rev. Infect. Dis. 13:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang, H. S., and D. A. Sack. 2001. Development of a novel in vitro assay (ALS assay) for evaluation of vaccine-induced antibody secretion from circulating mucosal lymphocytes. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:482-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crump, J. A., S. P. Luby, and E. D. Mintz. 2004. The global burden of typhoid fever. Bull. W. H. O. 82:346-353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falklind-Jerkerus, S., F. Felici, C. Cavalieri, C. Lo Passo, G. Garufi, I. Pernice, M. M. Islam, F. Qadri, and A. Weintraub. 2005. Peptides mimicking Vibrio cholerae O139 capsular polysaccharide elicit protective antibody response. Microbes Infect. 7:1453-1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forrest, B. D. 1992. Indirect measurement of intestinal immune responses to an orally administered attenuated bacterial vaccine. Infect. Immun. 60:2023-2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gasem, M. H., W. M. Dolmans, B. B. Isbandrio, H. Wahyono, M. Keuter, and R. Djokomoeljanto. 1995. Culture of Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi from blood and bone marrow in suspected typhoid fever. Trop. Geogr. Med. 47:164-167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilman, R. H., M. Terminel, M. M. Levine, P. Hernandez-Mendoza, and R. B. Hornick. 1975. Relative efficacy of blood, urine, rectal swab, bone-marrow, and rose-spot cultures for recovery of Salmonella typhi in typhoid fever. Lancet i:1211-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris, J. B., R. C. Larocque, F. Chowdhury, A. I. Khan, T. Logvinenko, A. S. Faruque, E. T. Ryan, F. Qadri, and S. B. Calderwood. 2008. Susceptibility to Vibrio cholerae infection in a cohort of household contacts of patients with cholera in Bangladesh. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2:e221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatta, M., and H. L. Smits. 2007. Detection of Salmonella typhi by nested polymerase chain reaction in blood, urine, and stool samples. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 76:139-143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herath, H. M. 2003. Early diagnosis of typhoid fever by the detection of salivary IgA. J. Clin. Pathol. 56:694-698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iperepolu, O. H., P. E. Entonu, and S. M. Agwale. 2008. A review of the disease burden, impact and prevention of typhoid fever in Nigeria. West Afr. J. Med. 27:127-133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.John, T. J., R. Samuel, V. Balraj, and R. John. 1998. Disease surveillance at district level: a model for developing countries. Lancet 352:58-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalhan, R., I. Kaur, R. P. Singh, and H. C. Gupta. 1998. Rapid diagnosis of typhoid fever. Indian J. Pediatr. 65:561-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kantele, A. 1996. Peripheral blood antibody-secreting cells in the evaluation of the immune response to an oral vaccine. J. Biotechnol. 44:217-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kantele, J. M., H. Arvilommi, S. Kontiainen, M. Salmi, S. Jalkanen, E. Savilahti, M. Westerholm, and A. Kantele. 1996. Mucosally activated circulating human B cells in diarrhea express homing receptors directing them back to the gut. Gastroenterology 110:1061-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirkpatrick, B. D., M. D. Bentley, A. M. Thern, C. J. Larsson, C. Ventrone, M. V. Sreenivasan, and L. Bourgeois. 2005. Comparison of the antibodies in lymphocyte supernatant and antibody-secreting cell assays for measuring intestinal mucosal immune response to a novel oral typhoid vaccine (M01ZH09). Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12:1127-1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirkpatrick, B. D., R. McKenzie, J. P. O'Neill, C. J. Larsson, A. L. Bourgeois, J. Shimko, M. Bentley, J. Makin, S. Chatfield, Z. Hindle, C. Fidler, B. E. Robinson, C. H. Ventrone, N. Bansal, C. M. Carpenter, D. Kutzko, S. Hamlet, C. LaPointe, and D. N. Taylor. 2006. Evaluation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi (Ty2 aroC-ssaV-) M01ZH09, with a defined mutation in the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2, as a live, oral typhoid vaccine in human volunteers. Vaccine 24:116-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaRocque, R. C., R. F. Breiman, M. D. Ari, R. E. Morey, F. A. Janan, J. M. Hayes, M. A. Hossain, W. A. Brooks, and P. N. Levett. 2005. Leptospirosis during dengue outbreak, Bangladesh. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:766-769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundgren, A., J. Kaim, and M. Jertborn. 2009. Parallel analysis of mucosally derived B- and T-cell responses to an oral typhoid vaccine using simplified methods. Vaccine 27:4529-4536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGhee, J. R., and H. Kiyono. 1993. New perspectives in vaccine development: mucosal immunity to infections. Infect. Agents Dis. 2:55-73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nieminen, T., H. Kayhty, and A. Kantele. 1996. Circulating antibody secreting cells and humoral antibody response after parenteral immunization with a meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 28:53-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pang, T., and S. D. Puthucheary. 1983. Significance and value of the Widal test in the diagnosis of typhoid fever in an endemic area. J. Clin. Pathol. 36:471-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pohan, H. T. 2004. Clinical and laboratory manifestations of typhoid fever at Persahabatan Hospital, Jakarta. Acta Med. Indones. 36:78-83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qadri, F., T. Ahmed, F. Ahmed, M. S. Bhuiyan, M. G. Mostofa, F. J. Cassels, A. Helander, and A. M. Svennerholm. 2007. Mucosal and systemic immune responses in patients with diarrhea due to CS6-expressing enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 75:2269-2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qadri, F., R. Raqib, F. Ahmed, T. Rahman, C. Wenneras, S. K. Das, N. H. Alam, M. M. Mathan, and A. M. Svennerholm. 2002. Increased levels of inflammatory mediators in children and adults infected with Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 9:221-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qadri, F., E. T. Ryan, A. S. Faruque, F. Ahmed, A. I. Khan, M. M. Islam, S. M. Akramuzzaman, D. A. Sack, and S. B. Calderwood. 2003. Antigen-specific immunoglobulin A antibodies secreted from circulating B cells are an effective marker for recent local immune responses in patients with cholera: comparison to antibody-secreting cell responses and other immunological markers. Infect. Immun. 71:4808-4814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rollman, E., T. Ramqvist, B. Zuber, K. Tegerstedt, A. Kjerrstrom Zuber, J. Klingstrom, L. Eriksson, K. Ljungberg, J. Hinkula, B. Wahren, and T. Dalianis. 2003. Genetic immunization is augmented by murine polyomavirus VP1 pseudocapsids. Vaccine 21:2263-2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saha, S. K., M. Ruhulamin, M. Hanif, M. Islam, and W. A. Khan. 1996. Interpretation of the Widal test in the diagnosis of typhoid fever in Bangladeshi children. Ann. Trop. Paediatr. 16:75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarma, V. N., A. N. Malaviya, R. Kumar, O. P. Ghai, and M. M. Bakhtary. 1977. Development of immune response during typhoid fever in man. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 28:35-39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talawadekar, N., P. Vadher, D. Antani, V. Kale, and S. Kamat, and 1989. Chloramphenicol resistant Salmonella species isolated between 1978 and 1987. J. Postgrad. Med. 35:79-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wain, J., V. B. Pham, V. Ha, N. M. Nguyen, S. D. To, A. L. Walsh, C. M. Parry, R. P. Hasserjian, V. A. HoHo, T. H. Tran, J. Farrar, N. J. White, and N. P. Day. 2001. Quantitation of bacteria in bone marrow from patients with typhoid fever: relationship between counts and clinical features. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1571-1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wenneras, C., F. Qadri, P. K. Bardhan, R. B. Sack, and A. M. Svennerholm. 1999. Intestinal immune responses in patients infected with enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and in vaccinees. Infect. Immun. 67:6234-6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willke, A., O. Ergonul, and B. Bayar. 2002. Widal test in diagnosis of typhoid fever in Turkey. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 9:938-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yew, F. S., S. K. Chew, K. T. Goh, E. H. Monteiro, and Y. S. Lim. 1991. Typhoid fever in Singapore: a review of 370 cases. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 94:352-357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]