Abstract

Frankia species are the most geographically widespread gram-positive plant symbionts, carrying out N2 fixation in root nodules of trees and woody shrubs called actinorhizal plants. Taking advantage of the sequencing of three Frankia genomes, proteomics techniques were used to investigate the population of extracellular proteins (the exoproteome) from Frankia, some of which potentially mediate host-microbe interactions. Initial two-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of culture supernatants indicated that cytoplasmic proteins appeared in supernatants as cells aged, likely because older hyphae lyse in this slow-growing filamentous actinomycete. Using liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry to identify peptides, 38 proteins were identified in the culture supernatant of Frankia sp. strain CcI3, but only three had predicted export signal peptides. In symbiotic cells, 42 signal peptide-containing proteins were detected from strain CcI3 in Casuarina cunninghamiana and Casuarina glauca root nodules, while 73 and 53 putative secreted proteins containing signal peptides were identified from Frankia strains in field-collected root nodules of Alnus incana and Elaeagnus angustifolia, respectively. Solute-binding proteins were the most commonly identified secreted proteins in symbiosis, particularly those predicted to bind branched-chain amino acids and peptides. These direct proteomics results complement a previous bioinformatics study that predicted few secreted hydrolytic enzymes in the Frankia proteome and provide direct evidence that the symbiosis succeeds partly, if not largely, because of a benign relationship.

The Frankia-actinorhizal plant symbiosis is widespread in nature, providing fixed nitrogen to nearly 200 known species of plants collectively distributed on every continent, except Antarctica, and in most climate zones (5). Actinorhizal plants are pioneer species that add nitrogen and organic material to nutrient-poor or new soils. Some species are grown commercially for timber and windbreaks, such as Alnus (alder) and Casuarina trees. When infected with Frankia, root nodules that appear as repeatedly branching truncated lateral roots are induced.

Frankia spp. are N2-fixing, filamentous members of the Actinobacteria. Strains are phenotypically diverse, colonizing distinct subgroups of plants. Three sequenced genomes (strains CcI3, ACN14a, and EAN1pec) span a range of sizes from 5.4 Mb to 9 Mb (26). Genome sequencing has allowed the use of high-throughput technologies, such as proteomics and transcriptomics, to discover actively expressed genes and shape conclusions about Frankia physiology in culture and symbiosis.

Extracellular and surface-associated proteins are of particular interest in symbioses, as the interface between the bacterium and plant is the first zone of contact, where proteins involved in molecular recognition, polymer degradation, solute binding, or defense may be localized. In the rhizobium-legume symbiosis, secreted proteins implicated in plant interactions include some that sense plant flavonoids, modify surface polysaccharides, bind calcium, or otherwise directly affect the biology of the host, such as the “Nops” (nodulation outer proteins), which are injected into host cells by type III or type IV secretion systems in some strains (8, 11). Essentially nothing is known about bacterial proteins involved in molding the actinorhizal symbiosis on plant roots.

Unlike related soil actinobacteria, such as Streptomyces spp., that secrete an array of degradative enzymes, Frankia strains have been predicted to secrete comparatively few proteins, according to an extensive bioinformatics study that predicted frankial secreted proteomes based on consensus signal peptides and transmembrane domains (12, 22). While several Streptomyces species are predicted to secrete more than 100 hydrolases, the Frankia secreted proteomes have only 10 to 20, and these are primarily lipases, esterases, and proteases, rather than putative polysaccharide-degrading enzymes (22). This observation raises the hypothesis that frankiae are successful symbionts at least partly because they present an innocuous visage to the plant host.

The culture supernatant of Frankia alni strain ACN14a, an Alnus symbiont, was recently investigated, using individual protein spots excised from two-dimensional (2D) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels (1). Several glycolytic and tricarboxylic acid cycle enzymes, among other cytoplasmic proteins, were found in the extracellular fraction, but few signal peptide-containing proteins were detected (1), raising the possibility that cell lysis was responsible for many of the proteins detected. A comparison with the symbiotic state was not done at that time.

To provide a more complete overview of secreted proteins in light of our previous bioinformatics study (22), we investigated both free-living and symbiotic cells of another Frankia strain, the Casuarina symbiont CcI3, using 2D SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC MS/MS) of trypsin-digested protein samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture.

Frankia sp. strain CcI3, originally isolated from greenhouse-grown Casuarina cunninghamiana (38), was grown in liquid Frankia defined minimal medium (FDM) with 0.5% pyruvate in stationary 100-ml cultures, in 250-ml screw-cap flasks, at 30°C (http://web.uconn.edu/mcbstaff/benson/Frankia/FDM.htm). Every 3 or 4 days, cells were collected by centrifugation, homogenized with a Dounce-type tissue homogenizer to break up mycelia, and washed twice in fresh medium before transfer. Cells corresponding to ∼0.5 mg total protein were transferred into each flask. Strain CpI1, originally isolated from Comptonia peregrina (7), was cultured similarly, but in FDM containing 0.5% succinate, with shaking at 125 rpm at 30°C.

Preparation of samples for 2D gel electrophoresis.

For proteins in the culture supernatant, cells were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g, and the supernatant was clarified by vacuum filtration through a 0.22-μm filter. Protein from the filtered supernatant (100 ml) was concentrated by dialysis against polyethylene glycol (PEG 8000; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to a final volume of 1 to 5 ml. Cytoplasmic protein was obtained from ∼0.5 ml of packed cells, resuspended in FDM, and sonicated (4 min at 40% duty cycle). After sonication, the suspension was centrifuged at 16,000 × g, and the supernatant was saved as the cytoplasmic sample.

Protein was quantified from culture supernatants and cytoplasmic extracts with the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL) (32). To concentrate the samples, proteins were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), either at 4°C overnight or at −20°C for several hours. The precipitate was centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 30 min, washed twice with ice-cold acetone, and collected by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min.

For 2D SDS-PAGE, TCA-precipitated protein pellets were dissolved in rehydration/sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), applied to a 7-cm immobilized-pH-gradient strip (pH 4 to 7), and then subjected to isoelectric focusing using the conditions recommended by the manufacturer (Bio-Rad). Protein loading on gels was empirically determined to give similar spot intensities on both cytoplasmic and supernatant gels. Generally, around 20 to 30 μg of protein was loaded. After equilibration of the immobilized-pH-gradient strip according to the manufacturer's instructions, the second dimension was run on an 11% polyacrylamide gel, at 200 V for 45 min. Gels were stained using a silver staining procedure based on the study by Blum et al. (6), as follows: fixation for 10 min in 40% methanol-13.5% formalin, with two 5-min rinses in water; addition of 0.02% Na2S2O3 for 1 min; 0.1% AgNO3 staining for 10 min; developing with a solution of 3% Na2CO3-0.05% formalin-0.000016% Na2S2O3; stopping development with 2.3 M citric acid.

Preparation of root nodule protein samples.

Casuarina cunninghamiana and Casuarina glauca seeds were washed with 20% household bleach and germinated on water agar or in sterile sand. Seedlings (2 to 4 weeks old) were inoculated with Frankia sp. strain CcI3, by soaking roots for several hours in 10 mM phosphate buffer containing bacterial cells. Plants were grown under natural sunlight in a greenhouse and transferred to larger pots containing sterile sand as needed. Three root nodule samples were collected: two from C. cunninghamiana (9 and 11 months old) and one from C. glauca (4 years old). Nodules were dissected in ice-cold TEA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 20 mM sodium ascorbate [pH 7.6]) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The younger, 1- to 2-mm tips of nodule lobes were collected to enrich for metabolically active bacterial cells, and the root epidermis was gently peeled using a scalpel and dissecting forceps while being viewed through a dissecting microscope. The infected cortical cells were then scraped from the vascular tissue and placed in a separate microcentrifuge tube. The remains of 150 peeled root nodule lobes per sample were macerated in TEA buffer, using a Dounce-type tissue homogenizer. The nodule cell material was washed several times in TEA buffer, followed by six washes in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 6.8) to remove plant phenolics. The infected plant cells were sonicated for 5 to 10 min (50% duty cycle) in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 6.8) plus 5 mM Na2EDTA, to release bacterial proteins. Insoluble material was pelleted, and the soluble protein was quantified using the Pierce BCA assay (32). The resulting protein extract was enriched in Frankia proteins from all cellular compartments, along with plant proteins that were associated with the infected cells. The resulting peptides were binned using an informatics approach into plant and bacterial fractions and further into those that are in the predicted Frankia exoproteome. We report here only those proteins predicted to form part of the exoproteome.

Field-collected root nodules of Alnus incana subsp. rugosa and Elaeagnus angustifolia were sampled from 2- to 3-foot-tall shrubs growing in roadside lots off Route 32 (Willington, CT) and Route 195 (Willington, CT), respectively, in June and July 2008. Nodules were dissected within 2 hours of collection in ice-cold TEA buffer and prepared as described above. Roughly 100 root nodule lobes were harvested per plant.

Preparation of samples for LC MS/MS analysis.

Supernatants from four separate CcI3 cultures between 2 and 5 days old were analyzed; one was analyzed from strain CpI1 (3 days old). Instead of PEG precipitation, supernatants were lyophilized, frozen at −80°C, and then thawed and resuspended in 5 to 10 ml water prior to TCA precipitation (described above). Root nodule protein extracts, containing 0.35 to 1 mg protein as measured by the BCA assay, were also TCA precipitated.

Precipitated protein pellets were dried briefly (5 min) and dissolved in 8 M urea-0.4 M NH4HCO3 (pH 7.5 to 8.5). Disulfide bonds were reduced by adding 7.5 mM of dithiothreitol and incubating for 20 min at 37°C. Iodoacetamide was added to 15 mM to block sulfhydryl groups, and the solution was incubated at room temperature for 20 min in the dark. The solution was diluted fourfold in water, and sequencing-grade trypsin was added according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Trypsin digestion was carried out at 37°C for 18 to 24 h, and digested samples were frozen at −80°C.

LC MS/MS of culture supernatant samples.

LC MS/MS analysis was performed on a Waters capillary LC coupled to a Micromass Q-Tof Ultima mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA). Trypsin-digested peptides were dried and resuspended in 3 μl 70% formic acid, and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was added to bring the volume to 10 μl. Samples (5 μl) were injected into a 0.1-mm by 150-mm Atlantis C18 column (Waters) and run at 500 nl/minute. High-performance liquid chromatography was started with 95% buffer A (98% water, 2% acetonitrile, 0.1% acetic acid, and 0.01% TFA) and 5% buffer B (20% water, 80% acetonitrile, 0.09% acetic acid, and 0.01% TFA). A linear gradient was run with increasing amounts of buffer B, as follows: 5% buffer B for 3 min, 37% buffer B for 43 min, 75% buffer B for 75 min, and 95% buffer B for 85 min. Eluted peptides were ionized by electrospray, peptide masses were measured, and doubly or triply charged peptides were fragmented. To enhance fragmentation, a collision energy ramp corresponding to mass and charge state was established. The mass spectrometer was run in data-dependent acquisition mode, alternating between MS and MS/MS modes when the total ion current exceeded a threshold of 1.5 counts/second. MS/MS spectra were analyzed with the Mascot database search algorithm (Matrix Science, Boston, MA) (30).

LC MS/MS of root nodule extracts with multidimensional protein identification technology.

The trypsin digests from the root nodule protein samples were fractionated by strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography on an Applied Biosystems Vision workstation. Prior to SCX, the sample was acidified with 2 μl of 1 M phosphoric acid. A linear gradient was run for 118 min on a 2.1-mm by 200-mm PolySulfoethyl A column (PolyLC Inc.). The gradient was from 99.3% to 2.0% of buffer A (10 mM potassium phosphate, 25% acetonitrile [pH 3.0]), with increasing concentrations of buffer B (same as buffer A but with 1 M potassium chloride added). Fractions were dried, dissolved in 5 μl of 70% formic acid, and diluted to 15 μl in 0.1% TFA. For each of the three Casuarina nodule replicate samples, 10 pooled fractions were used. For the A. incana and E. angustifolia samples (one each), 20 pooled fractions were analyzed.

LC MS/MS of pooled SCX fractions was performed with a nanoAcquity ultra-performance LC system (Waters) coupled to an LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). LC columns were a Waters Symmetry C18 (180-μm by 20-mm) trap column and a 1.7-μm particle nanoAcquity ultra-performance LC column (75 μm × 250 mm). Initial conditions were 95% buffer A (100% water, 0.1% formic acid) and 5% buffer B (100% acetonitrile, 0.075% formic acid). A 51-min linear gradient was run with increasing amounts of buffer B, as follows: 5% buffer B starting, up to 50% buffer B at 50 min, and 85% buffer B at 51 min. The LTQ Orbitrap performs one microscan to acquire the MS, and then eight data-dependent MS/MS acquisitions are carried out in the ion trap. MS/MS spectra were analyzed with the Mascot database search algorithm (30).

Identification of supernatant protein spots by MS/MS.

Three of the darkest protein spots detected in CcI3 supernatants were selected for identification. Using a 2D gel of protein concentrated from four combined flasks of 4-day-old supernatants (400 ml total), Coomassie blue-stained gel spots were excised, cut into small pieces, and added to 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes (prewashed with 500 μl 0.1% TFA-60% CH3CN). Gel pieces were washed with 250 μl of 50% H2O-50% acetonitrile for 5 min. After the wash solution was removed, 250 μl of 50% CH3CN-50 mM NH4HCO3 was added, and samples were washed for 30 min at room temperature on a tilt table. Another 30-min wash was performed, using 50% CH3CN-10 mM NH4HCO3 instead. Gel pieces were dried with a Speedvac, and 0.1 μg of modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) was added per 15 mm3 of gel in 15 μl 10 mM NH4HCO3 to all samples. After 5 to 10 min, an additional 20 μl 10 mM NH4HCO3 was added. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and then stored at −80°C prior to MS/MS analysis, which was performed on a Micromass Q-Tof Ultima mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA) as described above for LC MS/MS of culture supernatants.

Protein identification with Mascot program.

MS/MS spectra were converted into Mascot-compatible files by using the Mascot distiller program, which combines MS/MS scans from the same precursor ion. The program selects +2 and +3 ions with a signal-to-noise ratio of at least 1.2 and creates a peak list, which was searched by the Mascot algorithm against one or more Frankia genomes. All CcI3 protein samples (and the CpI1 supernatant sample) were searched versus the strain CcI3 genome, while the data from field-collected nodules were searched against the CcI3, ACN14a, and EAN1pec genomes. The FASTA amino acid sequences of the three Frankia genomes (CcI3, NCBI reference sequence [RefSeq] NC_007777; ACN14a, NCBI RefSeq NC_008278; EAN1pec, NCBI RefSeq NC_009921) were obtained from the NCBI RefSeq FTP site (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/Bacteria).

Mascot specifications included a peptide tolerance window of ±0.6 Da, an MS/MS fragment tolerance of ±0.4 Da, peptide charges of +2 or +3, allowance of one missed cleavage by trypsin, and inclusion of amino acid modifications, such as methionine oxidation. Peptides are assigned a probability-based ion score, equal to −10 × log10P, where P is the absolute probability that a match (between the observed peak lists and the theoretical peak lists in the database) is random. The probability of a random match depends on the size of the database, which is defined as the number of theoretical masses that fall within the peptide tolerance window provided. In this analysis, the threshold scores for significant peptide matches (P < 0.05) were assigned by Mascot as follows: ion scores of >15 were significant when using the CcI3 genome as a database, while scores of >16 were significant using the other two Frankia genomes. We considered a protein to be identified by Mascot if two or more unique peptides matched the protein. Mascot also assigns a nonprobabalistic protein score, derived from the individual peptide matches and the total number of queries. Mascot protein scores and peptide sequences identified in this study are provided in the supplemental material.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

2D SDS-PAGE.

As a first step, we visualized proteins secreted from growing CcI3 cells by using a traditional 2D SDS-PAGE approach with cultures of various ages. Frankia cells grow slowly by hyphal tip extension rather than binary division, conferring a pseudo-linear, rather than exponential, mode of growth, without a clear stationary phase. Preliminary experiments indicated that frequent transfer (every 3 to 4 days) of washed hyphae, fragmented by homogenization, produces the most-uniform culture. Many Frankia studies use cells cultured for 10 days or more between transfer that contain a pronounced diversity of cells, including growing hyphal tips, nongrowing cells, and developing sporangia (4). Such cultures generally include an abundance of empty hyphae, indicating cell lysis (15).

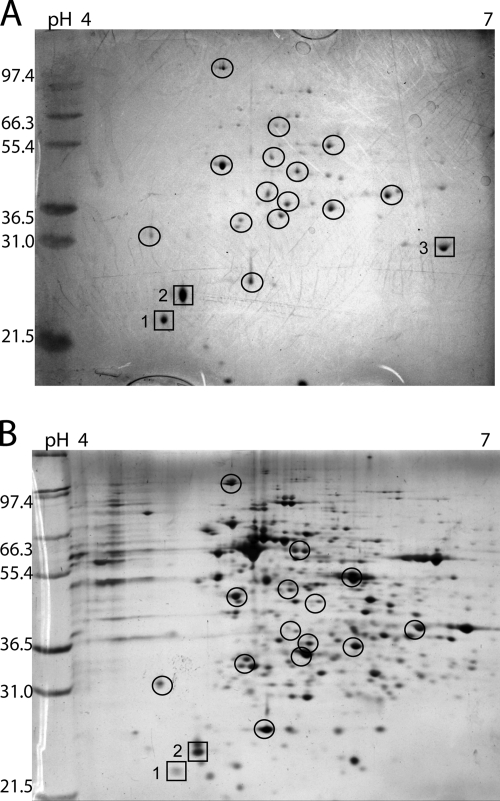

Proteins in the supernatant of young, 3- or 4-day-old Frankia cells were visualized by 2D SDS-PAGE. When using carefully washed cells to start cultures, extracellular proteins concentrated from 100 ml of 3-day-old culture supernatants were at the limits of detection of silver-stained 2D gels, with fewer than 20 faint spots seen (not shown). When a greater volume (400 ml) was concentrated from 4-day-old cultures, roughly 40 spots could be visualized by Coomassie staining (Fig. 1A). Most of the protein spots from the supernatant were also found in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 1B). This slow accumulation of extracellular proteins that overlap with cytoplasmic protein spots strongly suggests that cell lysis accounts for many of the proteins in the culture medium.

FIG. 1.

(A) 2D gel of CcI3 supernatant from 4-day-old cultures (four 100-ml flasks combined). Approximately 150 μg protein was loaded, and the gel was stained with Coomassie blue. (B) 2D gel of CcI3 cytoplasmic extract from 4-day-old cells. Approximately 50 μg protein was loaded, and the gel was silver stained. Protein spots present in both extracts are circled. Three protein spots (boxes) were identified by MS/MS, as follows: spot 1, stress protein (gi 86738980); spot 2, stress protein (gi 86742358); spot 3, phosphoesterase (gi 86739452).

Three of the more abundant proteins were cut from the gels and identified by MS/MS (Fig. 1). Spots 1 and 2 were identified as small stress proteins, and were also present in the supernatants of strains CpI1 and ACN14a (gi 86738980 and gi 86742358) (Table 1). Homologs of these proteins were upregulated in several Frankia strains and Streptomyces coelicolor upon exposure to plant extracts (2, 13, 19). Their presence in the supernatant cannot be ascribed to specific secretion mechanisms, since neither has an identifiable signal peptide. Spot 3 is annotated as a phosphoesterase or a phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate phosphatase, and contains a putative secretion signal sequence predicted by SignalP (3). The protein was also detected by one peptide in Casuarina nodules. Its gene is part of an operon containing several glycosyl transferase genes, suggesting a cell surface-related function. Spot 3 was the only major spot not visible in the cytoplasmic extract 2D gel (Fig. 1), an observation supporting its extracellular localization.

TABLE 1.

Proteins identified by LC MS/MS in the CcI3 culture supernatantc

| Proteins | gi no. | Annotation | Molecular size (kDa) | No. of replicates | Detection in supernatant: |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CpI1a | ACN14ab | |||||

| Sec signal peptidesd | 86739057 | Extracellular ligand-binding receptor (LivK domain) | 39.8 | 1 | − | + |

| 86742940 | Periplasmic phosphate binding protein | 37.6 | 2 | − | − | |

| Central metabolism proteins | 86740018 | Aconitate hydratase 1 | 98.8 | 3 | − | − |

| 86743039 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, class II | 36.9 | 3 | − | + | |

| 86738768 | Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | 60.4 | 3 | − | − | |

| 86740342 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, type I | 35.6 | 3 | + | − | |

| 86742701 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, type I | 36.2 | 4 | − | − | |

| 86740901 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase, NADP-dependent | 79.0 | 2 | + | − | |

| 86742576 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (GTP) | 66.9 | 3 | − | − | |

| 86740343 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 40.9 | 3 | + | + | |

| 86742602 | Phosphopyruvate hydratase (enolase) | 44.8 | 3 | + | + | |

| 86739365 | Succinyl-CoA synthetase, α subunit | 29.8 | 1 | − | − | |

| 86739364 | Succinyl-CoA synthetase, β subunit | 40.2 | 3 | − | − | |

| 86740353 | Transaldolase | 39.8 | 2 | + | − | |

| 86739985 | Transketolase-like | 65.9 | 2 | − | − | |

| Other metabolism proteins | 86742537 | 4Fe-4S ferredoxin, iron-sulfur binding | 11.6 | 3 | + | − |

| 86742165 | Acyl carrier protein | 8.5 | 2 | + | − | |

| 86743129 | Adenosylhomocysteinase | 51.7 | 3 | − | − | |

| 86741632 | Alcohol dehydrogenase, zinc-binding | 35.1 | 3 | − | − | |

| 86742312 | Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase | 34.0 | 2 | − | + | |

| 86740866 | Butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase | 44.0 | 2 | − | − | |

| 86741123 | Cysteine synthase A | 32.5 | 1 | − | − | |

| 86741828 | Glutamine synthetase, type I | 53.8 | 3 | + | − | |

| 86738805 | Phosphoserine aminotransferase, putative | 39.9 | 2 | + | − | |

| Stress proteins | 86743073 | Chaperonin GroEL | 56.7 | 2 | − | − |

| 86738980 | Stress protein/tellurium resistance protein | 20.7 | 4 | + | + | |

| 86742358 | Stress protein/tellurium resistance protein TerE | 20.2 | 4 | + | + | |

| 86741504 | Superoxide dismutase | 22.0 | 3 | + | + | |

| Other proteins | 86740042 | Chlorite dismutase | 26.5 | 1 | − | − |

| 86741905 | Glutamyl-tRNA synthetase | 51.5 | 1 | − | − | |

| 86738903 | Glyoxylase/bleomycin dioxygenase domain | 29.6 | 3 | + | − | |

| 86741081 | Ham1-like protein | 19.2 | 2 | − | − | |

| 86740212 | Hypothetical protein Francci3_1507 (DsbA domain) | 22.3 | 2 | + | + | |

| 86742100 | Hypothetical protein Francci3_3417 | 11.1 | 2 | − | − | |

| 86742609 | Nucleotidyl transferase | 31.5 | 2 | − | − | |

| 86739868 | Peptidase M1, aminopeptidase N actinomycete-type | 95.8 | 3 | + | − | |

| 86739165 | Protein of unknown function DUF1416 | 10.2 | 1 | − | + | |

LC MS/MS analysis of the Frankia sp. strain CpI1 supernatant (this study).

Frankia alni strain ACN14a proteins identified from spots on 2D gels of the supernatant (1).

All proteins were identified by Mascot by two or more peptides with ion scores of >15, using the CcI3 genome as a database. CoA, coenzyme A.

Predicted by Signal P v.3.0 (3) to have signal peptides.

LC MS/MS identification of CcI3 supernatant proteins.

A more sensitive way to identify proteins in a complex sample is by using LC MS/MS of tryptic peptides. Silver staining on gels has a visualization limit of about 10 pg/mm2 (24); LC MS/MS can provide information on individual peptides at 1 to 10 pg. Direct LC MS/MS analysis of proteins from supernatants of 2- to 5-day-old CcI3 cultures yielded 37 protein identifications (Table 1; also see Table SM1 in the supplemental material). Fifteen homologs were detected in supernatants of strain CpI1 in this study, and 10 were detected in ACN14a in a previous study (1).

Consistent with the overlap observed between the supernatant and cell extract patterns on 2D gels, mainly cytoplasmic proteins were identified by LC MS/MS. With the exception of two proteins predicted to be secreted by the Sec pathway (Table 1), all others are predicted to be cytoplasmic using the LocateP program, a subcellular location predictor (39). Most of the proteins were either small (<30 kDa) or naturally abundant in the cytoplasm. Thirteen of the 37 proteins are enzymes in carbon central metabolic pathways, and others, such as glutamine synthetase and GroEL, are also abundant. Since cells were cultivated on pyruvate, which enters central metabolism through the TCA cycle and is converted to glucose by gluconeogenesis, enzymes of these pathways are highly expressed during growth and are expected to be the first detected during cell lysis.

Some studies have reported that certain glycolytic enzymes are associated with the cell surface in gram-positive bacteria (27). A surface-localized glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in streptococci binds to host extracellular matrix glycoproteins and cytoskeletal proteins, and a GAPDH abundant in the cell wall proteome of Lactobacillus plantarum is implicated in adhesion to mucin (17, 28). CcI3 also has a second GAPDH that is homologous to that located on the surface in other gram-positive bacteria. This cognate GADPH gene (gi 86742701) is between hypothetical protein genes, while the major GADPH is among genes encoding other glycolytic enzymes.

Extracellular localization of some other proteins is logical, such as the hypothetical protein (gi 86740212) with a “DsbA” (22.2 kDa; periplasmic disulfide bond oxidoreductase) domain, found in the supernatant of the three strains. Lysyl aminopeptidase activity was measured from CcI3 supernatant extracts, which is ascribed to “peptidase M1/aminopeptidase N” (gi 86739868), sharing 56% sequence identity with PepN purified from the supernatant of a Streptomyces culture (16). PepN may be responsible for cell wall turnover or amino acid scavenging outside the cell, though it does not appear to be exported by the Sec pathway.

Surprisingly, only two proteins detected contained predicted signal peptides for secretion via the Sec pathway: an extracellular ligand-binding receptor with a “LivK” (leucine/isoleucine/valine) conserved domain and a phosphate-binding protein (Table 1). These are not restricted to the supernatant, but were also detected in proteomics analyses of root nodules and cells (see Table 2). The signal peptide-containing phosphoesterase (Fig. 1, spot 3) was not identified by direct LC MS/MS analysis of the supernatant. As only one peptide was identified from the spot excised from the gel (see Table SM1 in the supplemental material), it is possible that this protein is less readily detected by LC MS/MS due to poor trypsin digestion, suboptimal ionization or fragmentation, or masking of peptides by other abundant spectra.

TABLE 2.

Signal peptide-containing Frankia proteins detected in actinorhizal root nodulesb

| Proteins | Frankia gi no. | Annotation | Detection in: |

LocateP prediction | LocateP subcellular localization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casuarina nodule | Alnus nodule | Elaeagnus nodule | CcI3 cytoplasma | |||||

| Cell wall/growth enzymes | 86742989 | ATP-dependent metalloprotease FtsH | + | + | + | + | Membrane | Multitransmembrane |

| 86742986 | d-Alanyl-d-alanine carboxypeptidase | − | + | + | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 86742615 | Lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis | + | + | − | + | Membrane | Multitransmembrane | |

| 158317879 | NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase | − | − | + | − | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 86740618 | OmpA/MotB domain protein | + | − | + | + | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 86738783 | Poly-gamma-glutamate biosynthesis protein | − | − | + | − | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 86742138 | Putative lipoprotein | + | − | + | + | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 86742932 | Putative lipoprotein | + | + | − | + | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 86739919 | Rod shape-determining protein MreC | + | + | + | − | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 86743040 | Transglycosylase-like | + | − | − | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 158316857 | UDP-N-acetylmuramoylalanine-d-glutamate ligase | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| Hydrolytic enzymes | 86741105 | Metalloprotease-like protein | + | + | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored |

| 158312797 | Peptidase S16 Lon domain protein | − | − | + | − | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 86743135 | Polyhydroxybutyrate depolymerase | − | + | + | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 111224419 | Putative alkaline serine protease | − | − | + | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 111219534 | Putative exported lipase | − | + | + | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 111223109 | Putative lipase | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| Solute-binding proteins (amino acids) | 86740324 | Branched-chain amino acid ABC transporter, substrate-binding | − | − | + | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) |

| 86739057 | Extracellular ligand-binding receptor (LivK domain) | + | + | − | + | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 86741514 | Extracellular ligand-binding receptor (LivK domain) | + | − | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 111222939 | Putative branched-chain amino acid transport, substrate-binding | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 111222806 | Putative branched-chain amino acid transport, substrate-binding | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 86739565 | Putative Leu/Ile/Val/Thr-binding protein precursor | + | + | + | + | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 86742202 | Putative glutamate binding protein of ABC transporter system | + | + | − | + | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 86741119 | Extracellular solute-binding protein, family 3 (Gln-binding) | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| Solute-binding proteins (peptides) | 111222240 | Dipeptide-binding lipoprotein | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored |

| 158313902 | Extracellular solute-binding protein family 5 | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 158314797 | Extracellular solute-binding protein family 5 | − | + | + | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 158318094 | Extracellular solute-binding protein family 5 | − | + | + | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 158315708 | Extracellular solute-binding protein family 5 | − | − | + | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 158316615 | Extracellular solute-binding protein family 5 | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 158317996 | Extracellular solute-binding protein family 5 | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| Solute-binding proteins (inorganic ions) | 86742252 | ABC transporter, aliphatic sulfonate-binding | + | + | + | + | Extracellular | Lipid anchored |

| 158317681 | Periplasmic binding protein (FepB domain, iron-binding) | − | − | + | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 158314107 | Periplasmic molybdate-binding protein | − | + | + | + | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 86742940 | Periplasmic phosphate-binding protein | + | + | − | + | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 86741175 | Periplasmic solute-binding protein (TroA domain) | + | − | − | + | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 86738968 | Putative sulfonate-binding protein precursor | + | − | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| Solute-binding proteins (other) | 86741521 | Extracellular solute-binding protein family 1 | + | − | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored |

| 158318778 | Extracellular solute-binding protein family 1 | − | − | + | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 158317895 | Extracellular solute-binding protein family 1 | − | + | + | + | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 111221811 | Putative ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 111223273 | Putative ABC transporter, membrane-binding protein | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| Proteins involved in cell processes | 86742499 | Alkaline phosphatase | − | − | + | − | Membrane | N-terminally anchored |

| 86739476 | Amidophosphoribosyltransferase-like | + | − | − | − | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 86742209 | DEAD/DEAH box helicase-like | + | + | − | + | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 86739994 | Diguanylate cyclase/phosphodiesterase | + | + | + | − | Membrane | Multi-transmembrane | |

| 158315891 | d-Isomer-specific 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase NAD-binding | − | + | − | − | Cell wall | LPxTG cell wall anchored | |

| 86740326 | DNA polymerase I | + | + | + | + | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 86742982 | DNA-directed DNA polymerase | + | − | − | − | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 86740098 | FAD dependent oxidoreductase | − | + | + | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 86738950 | FMN-binding | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 86739182 | Glycine cleavage T protein aminomethyl transferase | − | + | − | + | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 158311946 | Integral membrane sensor signal transduction histidine kinase | − | − | + | − | Membrane | Multitransmembrane | |

| 86742607 | MazG family protein | − | + | − | − | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 86741365 | N-6 DNA methylase | + | + | − | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 86739036 | Periplasmic sensor signal transduction histidine kinase | − | + | + | − | Membrane | Multitransmembrane | |

| 86741547 | Periplasmic sensor signal transduction histidine kinase | − | + | − | + | Membrane | Multitransmembrane | |

| 86740996 | Protoporphyrin IX magnesium-chelatase | − | + | + | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 111223706 | Putative copper resistance protein partial match | − | + | − | − | Membrane | C-terminally anchored | |

| 111223594 | Putative hybrid sensor histidine kinase/response regulator | − | + | − | + | Membrane | Multitransmembrane | |

| 111223825 | Putative IS605 family transposase | − | − | + | + | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 111222332 | Putative modular polyketide synthase | − | + | + | + | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 111223507 | Putative non-ribosomal peptide synthetase; putative signal peptide | − | + | + | − | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 111221481 | Putative S-adenosyl-l-methionine-dependent methyltransferases | − | + | − | − | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 158312253 | Putative sensor with HAMP domain | − | + | − | + | Membrane | Multitransmembrane | |

| 111219913 | Putative short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase | − | + | − | + | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 158313514 | Secreted protein | − | − | + | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 158317049 | Stage II sporulation E family protein | − | − | + | − | Membrane | Multitransmembrane | |

| 86741563 | Superoxide dismutase, copper/zinc binding | + | − | − | + | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 86739099 | Thiamine biosynthesis protein ThiC | + | − | + | + | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 111225298 | Threonine synthase | − | + | − | + | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 86742403 | Transcription termination factor Rho | + | + | + | + | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

| 86740221 | Transcriptional regulator, MerR family | − | + | − | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 86740783 | Transcriptional regulator, TetR family | + | + | − | − | Extracellular | Secretory (released) | |

| 158312181 | Type II secretion system protein | − | − | + | + | Membrane | Multitransmembrane | |

| 86741605 | von Willebrand factor, type A | − | − | + | + | Extracellular | Lipid anchored | |

| 86740906 | YceI | + | − | − | + | Membrane | N-terminally anchored | |

Data from multidimensional LC MS/MS analysis of cytoplasmic extract from cultured CcI3 cells provided as a comparison to CcI3 in Casuarina nodules (our unpublished data).

All proteins were predicted to contain signal peptides by both methods of SignalP v. 3.0 (Neural Networks and Hidden Markov Models), and predicted to contain zero to two transmembrane domains by TMHMM v. 2.0. Proteins were identified by Mascot by two or more significant peptides with ion scores of >15, using the CcI3 genome as a database for Casuarina nodule proteins and CcI3 cytoplasm, and either the CcI3, ACN14a, or EAN1pec genome for the Alnus and Elaeagnus nodule proteins.

Studies of culture filtrates from the actinobacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis have shown a high proportion of proteins derived from cell lysis, with the exception of a specially prepared filtrate analyzed by Malen et al. (20, 23, 34). Tullius et al. reported that abundantly produced proteins accumulate in the culture supernatant of Mycobacterium (35). Other actinobacteria have been reported to secrete substantially more proteins. Roughly 50% of the extracellular proteins of Corynebacterium diphtheriae had signal peptides, and 75% of supernatant proteins had signal peptides in Streptomyces lividans (10, 14). The low degree of protein secretion in Frankia could be related to the medium used. In minimal medium, exported proteins may not be produced; for example, Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis secrete large amounts of protein when grown in rich medium (36). Conversely, in Streptomyces species grown in minimal medium, the lack of complex nutrients stimulates cells to secrete proteins in order to scavenge resources (10). Bioinformatics analysis of the three Frankia genomes predicted few degradative enzymes, so it is unlikely that the medium alone accounts for the minimal secretome in strain CcI3 (22).

LC MS/MS identification of signal peptide-containing proteins in root nodules.

While we can conclude that few proteins are actively secreted in culture under the conditions used, proteins produced in symbiosis that also have predicted signal sequences reveal more about how frankiae function in symbiosis. To study these proteins, we used fractionation techniques to detect Frankia-specific proteins among a host of other proteins present in root nodules from three different nodule types. Since the Frankia genomes were searched by Mascot to identify peptides, Frankia proteins are specifically identified, despite the presence of plant proteins in the nodule extract.

The three sequenced Frankia genomes have genes for components of the Sec (general secretory) and Tat (twin arginine translocation) protein secretion pathways (22). At least four of the 10 Sec machinery components were found in each nodule sampled. SecA, YajC, FfH, and FtsY were detected in Casuarina nodules; SecA, SecD, and SecF in both A. incana and E. angustifolia nodules; FtsY in A. incana; and SecY in E. angustifolia. Since sampling for proteomics is rarely complete, we conclude that the major secretory machinery is synthesized and operational in symbiosis.

Unlike the situation in culture, 42 CcI3 proteins with predicted Sec signal peptides were detected from symbiotic CcI3 in Casuarina nodules, out of a total of 1,031 proteins identified by LC MS/MS (our unpublished data). To identify Frankia proteins expressed by uncharacterized Frankia strains from field-collected root nodules, peptides were matched to sequences from one or more sequenced Frankia genomes. Of 1,300 proteins from A. incana nodules, 32 with predicted signal peptides were identified when matched to the ACN14a genome; a total of 73 were identified when matched to all three Frankia genomes. Similarly, of 1,100 EAN1pec hits in field-grown E. angustifolia nodules, 31 with predicted signal peptides were identified when matched to the EAN1pec genome, and 53 were identified when matched with all three genomes.

Table 2 lists the Frankia proteins with predicted signal peptides (and two or fewer predicted transmembrane domains) identified from root nodule extracts. The complete list of signal peptide-containing proteins detected (including hypothetical proteins) and the peptide sequences matching each protein are provided in Tables SM2 to SM5 of the supplemental material. LocateP subcellular location predictions are shown to provide some distinction between extracellular and membrane- anchored proteins (39).

The “cell wall/growth” category contains known cell division and cell wall-modifying enzymes, many of which are predicted by LocateP to be released from the cell. Proteins with “OmpA” and “lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis” domains suggest cell envelope modification functions in Frankia.

Only one putative secreted hydrolase, a hypothetical protein possessing a metalloprotease domain, was detected in Casuarina root nodules, while two other proteases were detected in E. angustifolia nodules. Two putative secreted lipases were found in A. incana nodules. Surprisingly, the “exported lipase” (gi 111219534) in E. angustifolia nodules matched 15 peptides from the ACN14a protein sequence (see Table SM5 in the supplemental material), but did not match any peptides in the genome of the more closely related Elaeagnus strain EAN1pec, despite the 59% amino acid identity shared between homologous ACN14a and EAN1pec sequences.

Solute-binding proteins were the most common class of secreted proteins observed in the symbiotic proteomes. All but one were predicted by LocateP to be anchored to the membrane rather than released, which is a typical arrangement for such proteins in gram-positive bacteria (33). Conserved protein domains and top-scoring BLAST hits suggest which nutrients, metabolites, and ions are exchanged between the symbiont and host by the use of ABC transporters. Inorganic ion transport components include molybdate, phosphate, sulfonate, and possibly iron and other metal ions (“TroA” domain). Of the organic substrates, amino acid- and peptide-binding proteins were frequently detected, with the latter found only in the A. incana and E. angustifolia nodules. Three solute-binding proteins were expressed by CcI3 in Casuarina root nodules, but not detected in the proteome of CcI3 in culture. One of these is a “LivK” domain protein (gi 86741514) possessing sequence similarity to Azorhizobium and Bradyrhizobium proteins (E value of 10−44, with 30% amino acid identity). Proteomic studies have detected expression of branched-chain amino acid transporters in Bradyrhizobium and Sinorhizobium symbiotic bacteroids (9, 31). It is noteworthy that branched-chain amino acid-binding and peptide-binding protein genes fall into the top 20 duplicated gene families in both the ACN14a and EAN1pec genomes (26). Thus, amino acid transport in symbiosis may be an important component of bacterium-plant interactions.

An intriguing finding was the presence of multiple “extracellular solute-binding family 5” proteins, predicted to bind oligopeptides, in field-collected nodules. This provides another instance of an environmental Frankia strain, in this case the A. incana symbiont, expressing a protein more similar to a heterologous frankial sequence (EAN1pec). The EAN1pec genome contains seven paralogous “family 5” proteins, but the CcI3 and ACN14a genomes lack clear orthologs. The top-scoring BLAST hits to these duplicated EAN1pec sequences are putative peptide-binding proteins in Agrobacterium tumefaciens (31% identity, E value of 10−60) and Rhizobium leguminosarum (30% identity, E value of 10−55). Other proteins involved in a variety of cell processes, including transcriptional regulation, have signal peptides predicted. Many are associated with the membrane and are thus not secreted outside the cell.

Conclusions.

The gradual appearance of protein spots on 2D gels of supernatants as cultures age, the identity of peptides in the supernatant determined by LC MS/MS, and the observation that most members of the exoproteome were abundant and/or of small molecular size suggest cell lysis during growth rather than targeted secretion. It is probable that additional secreted proteins in Frankia remain either anchored to the membrane or associated with the cell envelope and are thus not found in the medium.

Symbiotic Frankia cells, prepared by sonication, yielded a greater number of cell wall-bound or membrane-bound proteins with signal peptides. In Casuarina root nodules and in field-collected nodules of other actinorhizal species, solute-binding proteins emerged as the most common class of secreted proteins. In gram-positive bacteria, solute-binding proteins are generally tethered to the cell wall, in contrast to gram-negative bacteria, where most reside in the periplasm (33). Branched-chain amino acid-binding proteins were detected in all nodules, but biochemical characterization is necessary to determine which ligands are bound.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of this study is that hydrolytic enzymes were rarely detected in either culture or symbiosis, indicating that plant cell wall or membrane digestion is not likely to be used by Frankia cells colonizing plant cells inside root nodules. Most plant pathogens secrete cellulases, pectinases, xylanases, or other enzymes to hydrolyze plant cell wall polymers (18, 29, 37). The lack of secreted hydrolases has been proposed to be favorable for microorganisms that form beneficial associations with plants (21, 25). Evidence presented here and reported in a previous bioinformatics study (22) that showed a diminutive secreted proteome strongly suggests that frankiae fall into this schema.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

LC MS/MS and Mascot data analyses were performed by Kathy Stone, Mary LoPresti, and Tom Abbott at the Mass Spectrometry and Protein Chemistry facility of the W. M. Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory at Yale University.

This work was supported by grant no. EF-0333173 from the National Science Foundation Microbial Genome sequencing program to D.R.B.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 September 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alloisio, N., S. Felix, J. Marechal, P. Pujic, Z. Rouy, D. Vallenet, C. Medigue, and P. Normand. 2007. Frankia alni proteome under nitrogen-fixing and nitrogen-replete conditions. Physiol. Plant. 130:450-453. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagnarol, E., J. Popovici, N. Alloisio, J. Marechal, P. Pujic, P. Normand, and M. P. Fernandez. 2007. Differential Frankia protein patterns induced by phenolic extracts from Myricaceae seeds. Physiol. Plant. 130:380-390. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendtsen, J. D., H. Nielsen, G. von Heijne, and S. Brunak. 2004. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340:783-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benson, D. R., and N. A. Schultz. 1990. Physiology and biochemistry of Frankia in culture, p. 107-127. In C. R. Schwintzer and J. D. Tjepkema (ed.), The biology of Frankia and actinorhizal plants. Academic Press, Inc., New York, NY.

- 5.Benson, D. R., and W. B. Silvester. 1993. Biology of Frankia strains, actinomycete symbionts of actinorhizal plants. Microbiol. Rev. 57:293-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum, H., H. Beier, and H. J. Gross. 1987. Improved silver staining of plant proteins, RNA and DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis 8:93-99. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callaham, D., P. DelTredici, and J. G. Torrey. 1978. Isolation and cultivation in vitro of the actinomycete causing root nodulation in Comptonia. Science 199:899-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deakin, W. J., and W. J. Broughton. 2009. Symbiotic use of pathogenic strategies: rhizobial protein secretion systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:312-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Djordjevic, M. A. 2004. Sinorhizobium meliloti metabolism in the root nodule: a proteomic perspective. Proteomics 4:1859-1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Escutia, M. R., G. Val, A. Palacin, N. Geukens, J. Anne, and R. P. Mellado. 2006. Compensatory effect of the minor Streptomyces lividans type I signal peptidases on the SipY major signal peptidase deficiency as determined by extracellular proteome analysis. Proteomics 6:4137-4146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fauvart, M., and J. Michiels. 2008. Rhizobial secreted proteins as determinants of host specificity in the rhizobium-legume symbiosis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 285:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodfellow, M., S. T. Williams, and M. Mordarski (ed.). 1988. Actinomycetes in biotechnology. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, CA.

- 13.Hammad, Y., J. Marechal, B. Cournoyer, P. Normand, and A. M. Domenach. 2001. Modification of the protein expression pattern induced in the nitrogen-fixing actinomycete Frankia sp. strain ACN14a-tsr by root exudates of its symbiotic host Alnus glutinosa and cloning of the sodF gene. Can. J. Microbiol. 47:541-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansmeier, N., T. C. Chao, J. Kalinowski, A. Puhler, and A. Tauch. 2006. Mapping and comprehensive analysis of the extracellular and cell surface proteome of the human pathogen Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Proteomics 6:2465-2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harriott, O. T., and A. Bourret. 2003. Improving dispersed growth of Frankia using Carbopol. Plant Soil 254:69-74. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatanaka, T., J. Arima, M. Uraji, Y. Uesugi, and M. Iwabuchi. 2007. Characterization, cloning, sequencing, and expression of an aminopeptidase N from Streptomyces sp. TH-4. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 74:347-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izquierdo, E., P. Horvatovich, E. Marchioni, D. Aoude-Werner, Y. Sanz, and S. Ennahar. 2009. 2-DE and MS analysis of key proteins in the adhesion of Lactobacillus plantarum, a first step toward early selection of probiotics based on bacterial biomarkers. Electrophoresis 30:949-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazemi-Pour, N., G. Condemine, and N. Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat. 2004. The secretome of the plant pathogenic bacterium Erwinia chrysanthemi. Proteomics 4:3177-3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langlois, P., S. Bourassa, G. G. Poirier, and C. Beaulieu. 2003. Identification of Streptomyces coelicolor proteins that are differentially expressed in the presence of plant material. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1884-1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malen, H., F. S. Berven, K. E. Fladmark, and H. G. Wiker. 2007. Comprehensive analysis of exported proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Proteomics 7:1702-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin, F., A. Aerts, D. Ahren, A. Brun, E. G. Danchin, F. Duchaussoy, J. Gibon, A. Kohler, E. Lindquist, V. Pereda, A. Salamov, H. J. Shapiro, J. Wuyts, D. Blaudez, M. Buee, P. Brokstein, B. Canback, D. Cohen, P. E. Courty, P. M. Coutinho, C. Delaruelle, J. C. Detter, A. Deveau, S. DiFazio, S. Duplessis, L. Fraissinet-Tachet, E. Lucic, P. Frey-Klett, C. Fourrey, I. Feussner, G. Gay, J. Grimwood, P. J. Hoegger, P. Jain, S. Kilaru, J. Labbe, Y. C. Lin, V. Legue, F. Le Tacon, R. Marmeisse, D. Melayah, B. Montanini, M. Muratet, U. Nehls, H. Niculita-Hirzel, M. P. Oudot-Le Secq, M. Peter, H. Quesneville, B. Rajashekar, M. Reich, N. Rouhier, J. Schmutz, T. Yin, M. Chalot, B. Henrissat, U. Kues, S. Lucas, Y. Van de Peer, G. K. Podila, A. Polle, P. J. Pukkila, P. M. Richardson, P. Rouze, I. R. Sanders, J. E. Stajich, A. Tunlid, G. Tuskan, and I. V. Grigoriev. 2008. The genome of Laccaria bicolor provides insights into mycorrhizal symbiosis. Nature 452:88-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mastronunzio, J. E., L. S. Tisa, P. Normand, and D. R. Benson. 2008. Comparative secretome analysis suggests low plant cell wall degrading capacity in Frankia symbionts. BMC Genomics 9:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattow, J., U. E. Schaible, F. Schmidt, K. Hagens, F. Siejak, G. Brestrich, G. Haeselbarth, E. C. Muller, P. R. Jungblut, and S. H. Kaufmann. 2003. Comparative proteome analysis of culture supernatant proteins from virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv and attenuated M. bovis BCG Copenhagen. Electrophoresis 24:3405-3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merril, C. R., D. Goldman, S. A. Sedman, and M. H. Ebert. 1981. Ultrasensitive stain for proteins in polyacrylamide gels shows regional variation in cerebrospinal fluid proteins. Science 211:1437-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagendran, S., H. E. Hallen-Adams, J. M. Paper, N. Aslam, and J. D. Walton. 2009. Reduced genomic potential for secreted plant cell-wall- degrading enzymes in the ectomycorrhizal fungus Amanita bisporigera, based on the secretome of Trichoderma reesei. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46:427-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Normand, P., P. Lapierre, L. S. Tisa, J. P. Gogarten, N. Alloisio, E. Bagnarol, C. A. Bassi, A. M. Berry, D. M. Bickhart, N. Choisne, A. Couloux, B. Cournoyer, S. Cruveiller, V. Daubin, N. Demange, M. P. Francino, E. Goltsman, Y. Huang, O. R. Kopp, L. Labarre, A. Lapidus, C. Lavire, J. Marechal, M. Martinez, J. E. Mastronunzio, B. C. Mullin, J. Niemann, P. Pujic, T. Rawnsley, Z. Rouy, C. Schenowitz, A. Sellstedt, F. Tavares, J. P. Tomkins, D. Vallenet, C. Valverde, L. G. Wall, Y. Wang, C. Medigue, and D. R. Benson. 2007. Genome characteristics of facultatively symbiotic Frankia sp. strains reflect host range and host plant biogeography. Genome Res. 17:7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pancholi, V., and G. S. Chhatwal. 2003. Housekeeping enzymes as virulence factors for pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 293:391-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pancholi, V., and V. A. Fischetti. 1992. A major surface protein on group A streptococci is a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase with multiple binding activity. J. Exp. Med. 176:415-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paper, J. M., J. S. Scott-Craig, N. D. Adhikari, C. A. Cuomo, and J. D. Walton. 2007. Comparative proteomics of extracellular proteins in vitro and in planta from the pathogenic fungus Fusarium graminearum. Proteomics 7:3171-3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perkins, D. N., D. J. Pappin, D. M. Creasy, and J. S. Cottrell. 1999. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis 20:3551-3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarma, A. D., and D. W. Emerich. 2006. A comparative proteomic evaluation of culture grown vs. nodule isolated Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Proteomics 6:3008-3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith, P. K., R. I. Krohn, G. T. Hermanson, A. K. Mallia, F. H. Gartner, M. D. Provenzano, E. K. Fujimoto, N. M. Goeke, B. J. Olson, and D. C. Klenk. 1985. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150:76-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tam, R., and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1993. Structural, functional, and evolutionary relationships among extracellular solute-binding receptors of bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57:320-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tjalsma, H., H. Antelmann, J. D. Jongbloed, P. G. Braun, E. Darmon, R. Dorenbos, J. Y. Dubois, H. Westers, G. Zanen, W. J. Quax, O. P. Kuipers, S. Bron, M. Hecker, and J. M. van Dijl. 2004. Proteomics of protein secretion by Bacillus subtilis: separating the “secrets” of the secretome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:207-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tullius, M. V., G. Harth, and M. A. Horwitz. 2001. High extracellular levels of Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthetase and superoxide dismutase in actively growing cultures are due to high expression and extracellular stability rather than to a protein-specific export mechanism. Infect. Immun. 69:6348-6363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voigt, B., H. Antelmann, D. Albrecht, A. Ehrenreich, K. H. Maurer, S. Evers, G. Gottschalk, J. M. van Dijl, T. Schweder, and M. Hecker. 2009. Cell physiology and protein secretion of Bacillus licheniformis compared to Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 16:53-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watt, S. A., A. Wilke, T. Patschkowski, and K. Niehaus. 2005. Comprehensive analysis of the extracellular proteins from Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris B100. Proteomics 5:153-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, Z., M. F. Lopez, and J. G. Torrey. 1984. A comparison of cultural characteristics and infectivity of Frankia isolates from root nodules of Casuarina species. Plant Soil 78:79-90. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou, M., J. Boekhorst, C. Francke, and R. J. Siezen. 2008. LocateP: genome-scale subcellular-location predictor for bacterial proteins. BMC Bioinformatics 9:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.