Abstract

In Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, which causes porcine pleuropneumonia, ilvI was identified as an in vivo-induced (ivi) gene and encodes the enzyme acetohydroxyacid synthase (AHAS) required for branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) biosynthesis. ilvI and 7 of 32 additional ivi promoters were upregulated in vitro when grown in chemically defined medium (CDM) lacking BCAA. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that BCAA would be found at limiting concentrations in pulmonary secretions and that A. pleuropneumoniae mutants unable to synthesize BCAA would be attenuated in a porcine infection model. Quantitation of free amino acids in porcine pulmonary epithelial lining fluid showed concentrations of BCAA ranging from 8 to 30 μmol/liter, which is 10 to 17% of the concentration in plasma. The expression of both ilvI and lrp, a global regulator that is required for ilvI expression, was strongly upregulated in CDM containing concentrations of BCAA similar to those found in pulmonary secretions. Deletion-disruption mutants of ilvI and lrp were both auxotrophic for BCAA in CDM and attenuated compared to wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae in competitive index experiments in a pig infection model. Wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae grew in CDM+BCAA but not in CDM−BCAA in the presence of sulfonylurea AHAS inhibitors. These results clearly demonstrate that BCAA availability is limited in the lungs and support the hypothesis that A. pleuropneumoniae, and potentially other pulmonary pathogens, uses limitation of BCAA as a cue to regulate the expression of genes required for survival and virulence. These results further suggest a potential role for AHAS inhibitors as antimicrobial agents against pulmonary pathogens.

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae is the causative agent of porcine pleuropneumonia, a disease of significant economic importance throughout the swine-raising areas of the world (6, 48). This pathogen possesses several well-studied virulence factors, including Apx toxins (20), capsular polysaccharides (57, 58), lipopolysaccharide (1, 17, 41), fimbriae (63), and iron-scavenging proteins (13, 50), which aid in the pathogenesis of acute pleuropneumonia marked by edema, hemorrhage, and necrosis (6, 26). In a search for additional virulence factors of this pathogen, we developed an in vivo expression technology (IVET) system and used this genetic tool to identify A. pleuropneumoniae gene promoters that are upregulated in vivo in the swine lung during infection compared to growth on laboratory media (22, 55).

One of the A. pleuropneumoniae in vivo-induced (ivi) promoters that we identified drives the ilvIH operon, which encodes both large and small subunits of acetohydroxy acid synthase isozyme III (AHAS) (55). AHAS enzymes catalyze pivotal steps in the biosynthesis of the branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) isoleucine, leucine, and valine (31). In a survey of IVET, signature-tagged mutagenesis, and microarray studies of other pathogens, we observed that genes involved in BCAA biosynthesis were frequently identified in studies of pathogens that cause pneumonia, meningitis, or septicemia but not in pathogens of the gastrointestinal tract (55). This observation suggests that the ability to synthesize BCAA is critical for pathogens of the respiratory tract but not for gastrointestinal pathogens. BCAA are essential amino acids that must be acquired from ingested food for most mammals, including humans and pigs, and it is possible that fluids in “clean” body sites such as the lungs have only limited supplies of BCAA compared to the digestive tract.

To test whether limitation of BCAA affects the expression of A. pleuropneumoniae genes that are induced in vivo, we compared expression from the A. pleuropneumoniae ivi promoters in a chemically defined medium (CDM) containing or lacking BCAA (55). We found that 25% (8 of 32) of the ivi promoters were upregulated during growth in CDM lacking BCAA compared to complete CDM. These included the ilvI promoter, as well as promoters for other genes potentially involved in survival within the host and virulence, such as hfq, a global regulator that binds sRNAs and mRNA and affects expression of virulence-associated genes in many pathogens (9, 49). These results strongly suggest that the environmental conditions encountered by A. pleuropneumoniae during infection of the swine lung include limitation of BCAA.

The goals of the present study were to quantify free BCAA in porcine pulmonary secretions, to evaluate the effect of these concentrations of BCAA on expression of genes required for BCAA biosynthesis, and to test whether A. pleuropneumoniae mutants that cannot synthesize BCAA were attenuated. A. pleuropneumoniae deletion-disruption mutants of the ilvI biosynthetic gene and the lrp gene, which encodes a global regulator required for expression of several genes involved in BCAA biosynthesis, were constructed and shown to be attenuated in a porcine infection model. The low levels of available BCAA in pulmonary secretions and the attenuation of these mutants led us to examine the effect of small molecule inhibitors of AHAS on growth of A. pleuropneumoniae in vitro. Several AHAS inhibitors were shown to prevent growth in CDM lacking BCAA but not complete CDM. These results demonstrate that A. pleuropneumoniae, and likely other bacterial pathogens of the respiratory tracts of other mammals, encounter conditions where BCAA are available only in limited supply during infection, that these low levels of BCAA can affect bacterial gene expression, and that these pathogens must be able to synthesize BCAA to survive and cause disease in the lung.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, primers, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in the present study are listed in Table 1. A. pleuropneumoniae strains were routinely grown on Bacto brain heart infusion (BHI) (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) or CDM (55) supplemented with 10 μg of β-NAD (V factor; Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO)/ml and incubated either at 35°C with 5% CO2 for agar media or at 35°C shaking at 160 rpm for broth media. To make CDM containing various concentrations of BCAA, a BCAA stock was added separately to CDM lacking BCAA to final concentrations equivalent to 10, 20, 50, or 100% of the BCAA concentration in complete CDM. For growth rate, in vitro competitive index, and experimental infection experiments, Bacto heart infusion broth (Becton Dickinson) supplemented with 10 μg of β-NAD/ml was also used. For plasmid selection in A. pleuropneumoniae, ampicillin and kanamycin were added at 50 μg/ml. For mating experiments, nalidixic acid was added at 50 μg/ml, and chloramphenicol was added at 2 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| A. pleuropneumoniae | ||

| AP100 | ATCC 27088, serotype 1A, passaged through pigs | ATCCb |

| AP225 | A. pleuropneumoniae ATCC 27088, serotype 1A, nalidixic acid resistant, passaged through pigs | 23 |

| AP359 | lrp double-crossover mutant of AP225 | 54 |

| AP364 | ilvI single-crossover mutant of AP225 | This study |

| AP365 | ilvI double-crossover mutant of AP225 | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| XL1-Blue mRF′ | Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| S17-1(λpir) | Δpir recA thi pro hsd (rK− mK+) RP4-2-Tc::Mu Km::Tn7; Tmpr Smr | 43 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | Apr; high-copy-number cloning vector | 62 |

| pGZRS18/19 | Apr; A. pleuropneumoniae-E. coli shuttle vectors | 59 |

| pGZRS39 | Kanr; A. pleuropneumoniae-E. coli shuttle vector | 59 |

| pER187 | Apr Cmr; CAT cassette-containing vector | 42 |

| pUC4K | Apr Kanr; Kan cassette-containing vector; source of the Kan promoter | 53 |

| pUM24Cm | Cmr Kanr; sacR-sacB-nptI cassette-containing vector | 40 |

| pGP704 | Apr; broad-host-range suicide vector | 34 |

| pGP704SacKan | Cmr Kanr; sacR-sacB-nptI from pUM24Cm cloned into pGP704 | This study |

| pTW415 | Kanr; rnd′-lrp-ftsK′ from AP100 cloned into pGZRS39 | 54 |

| pTW429 | Apr; 653 bp of the 5′ end of ilvI and 789 bp of the 3′ end of ilvI amplified by PCR from AP100 and cloned into SphI/SalI-digested pUC18 | This study |

| pRL100 | Apr Cmr; 300 bp containing Kan promoter from pUC4K cloned upstream of the CAT cassette of pER187 | This study |

| pRL101 | Apr Cmr; KanP-CAT cassette from pRL100 inserted into NsiI site in center of ilvI in pTW429 | This study |

| pRL102 | Apr Cmr Kanr; 2.5-kb fragment from pRL101 containing ΔilvI::KanP-CAT cloned into pGP704SacKan | This study |

| pRL103 | Apr; 2.8-kb fragment containing full ilvIH genes amplified from AP100 genomic DNA cloned into SalI/XbaI-digested pGZRS19 | This study |

| pIviI | Apr; pTF86 A. pleuropneumoniae IVET vector containing a 623-bp insert with the ilvI promoter upstream of promoterless luxAB and ribBAH genes | 22 |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Tetr, tetracycline resistance; Tmpr, trimethoprim resistance; Apr, ampicillin resistance; Smr, streptomycin resistance; Kanr, kanamycin resistance.

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Escherichia coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and E. coli S17-1 (λpir), used for cloning and mating, respectively, were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C on agar medium and at 37°C with rapid shaking in broth medium. For plasmid selection in E. coli, ampicillin was added at 100 μg/ml, kanamycin was added at 100 μg/ml, and chloramphenicol was added at 10 μg/ml.

Primers used for construction of plasmids or for quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Description |

|---|---|---|

| MM727 | CGTTGGAGGATTGCATGCAAAAACTTTCCG | Forward primer for construction of pTW429 (first ilvI fragment) |

| MM512 | GAGAATGCATCTCCACCAATGTATAAAACCG | Reverse primer for construction of pTW429 (first ilvI fragment) |

| MM513 | AACCGTTATGCATTATATTCCGATTGTGGG | Forward primer for construction of pTW429 (second ilvI fragment) |

| MM734 | CTGATGTCGACCTACGCATCTGTTCTC | Reverse primer for construction of pTW429 (second ilvI fragment) |

| MM668 | GTTGTGTGGAATTCTGAGCGGATAAC | Forward primer for construction of pRL100 (Kan promoter) |

| MM710 | CCCATTGGTACCCATATAAATCAGCATC | Reverse primer for construction of pRL100 (Kan promoter) |

| MM744 | CAATAAACCCGTCGACCAATCAAATCC | Forward primer for construction of pRL103 (full ilvIH operon plus promoter) |

| MM745 | CGTCATCTAGAGTTATAAAGCAATTAGGGT | Reverse primer for construction of pRL103 (full ilvIH operon plus promoter) |

| MM588 | CCATGCCGCGTGAATGA | 16S forward Q-PCR primer |

| MM589 | TTCCTCGCTACCGAAAGAACTT | 16S reverse Q-PCR primer |

| MM590 | TGTCGGTCAGCACCAAATGT | ilvI forward Q-PCR primer |

| MM591 | GCGACGAGGTTTTTCAAACG | ilvI reverse Q-PCR primer |

| MM592 | AATTGCTTGAAGCACCGCTATT | lrp forward Q-PCR primer |

| MM593 | CGTCCGGCTTACCTCTGACT | lrp reverse Q-PCR primer |

Restriction sites inserted by PCR are underlined.

Collection and analysis of BALF.

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was collected from five healthy 12- to 14-week-old Yorkshire-Landrace pigs by using standard veterinary procedures (52). All animal use protocols were approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Pigs were kept off feed for 4 h prior to the collection of BALF. Pigs were anesthetized, placed in ventral recumbency, and intubated to ensure respiratory function, and a flexible catheter was inserted through the tracheal tube. A total of 25 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.0005% methylene blue, kept at body temperature, was slowly introduced into the lungs. After 1 min, the fluid was aspirated with a syringe. This procedure was repeated with a second 25 ml of lavage fluid. The two samples were combined, and the total volume of the aspirated BALF was measured. BALF was centrifuged at 1,300 × g for 20 min to remove cells and filtered through a Millipore Centrifree cartridge (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

The volume of pulmonary epithelial lining fluid (ELF) in the recovered BALF was calculated both by measurement of the concentration of methylene blue in the BALF (3, 52) and by using urea as a marker of dilution (39). Concentration of free amino acids and of urea in the BALF were measured by physiological amino acid analysis on a Hitachi I-8800 amino acid analyzer (Hitachi High Technologies America, Pleasanton, CA) (45) at the Michigan State University Macromolecular Structure Facility and compared to the concentration of urea in a plasma sample collected immediately prior to the lavage procedure. Using urea as a marker for dilution, which was found to be more reproducible than the methylene blue method, the volume of ELF in each sample was calculated as follows: (the concentration of urea in the BALF × the volume of BALF)/the concentration of urea in plasma (39). The dilution factor was calculated as the volume of BALF divided by the volume of ELF. The concentration of each amino acid in ELF was calculated as the concentration in BALF times the dilution factor.

Luciferase reporter assays.

Expression from the ilvI promoter was quantified by using a luciferase expression plasmid (pIviI) in which the ilvI promoter drives the expression of promoterless luxAB genes (54). Wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae strain AP225 containing pIviI grown overnight on BHI agar supplemented with 10 μg of V factor/ml (BHIV) containing 50 μg of ampicillin/ml was suspended in CDM−BCAA and then diluted to an optical density at 520 nm (OD520) of ∼0.2 in 30 ml of prewarmed CDM containing 50 μg of ampicillin/ml and supplemented with 0, 10, 20, 50, or 100% of the concentration of BCAA found in complete CDM. Growth, measured as OD520, and luciferase activity were determined at 0, 1, 2, and 3 h time points. Luciferase activity was measured as relative light units (RLU) using N-decyl aldehyde substrate (Sigma) and a Turner model 20e luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA) as previously described (22, 55). Each sample was measured in triplicate, and the average RLU were normalized to the optical density of the culture. Three biological replicates of the complete experiment were performed.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of gene expression.

Wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae AP100 was grown to mid-exponential phase (OD520 = 0.5 to 0.6) in complete CDM+BCAA and cells pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended to an OD520 of ∼0.2 in 30 ml of prewarmed CDM supplemented with 0, 10, 20, 50, or 100% of the concentration of BCAA found in complete CDM. One hour after the shift to fresh medium, 30 ml of ice-cold methanol was added to each culture to stop growth, the resulting samples were chilled on ice for at least 5 min, and the cells were pelleted by centrifugation. RNA was isolated by using an RNeasy Midi kit protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), with the modification that 5 mg of lysozyme/ml was used instead of the recommended 400 μg/ml. Residual genomic DNA was removed with Turbo DNase (Ambion, Austin, TX), and the RNA was concentrated. The RNA concentration was measured by using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop, Wilmington, DE), and the RNA quality was verified by gel electrophoresis. The RNA was used as a template for RT, using random hexamers and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) was performed using gene-specific primers (Table 2) and SYBR green PCR Core reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The results were analyzed by using the SDS 2.1 software (Applied Biosystems) and the relative standard curve method, with normalization to 16S rRNA. Each sample was measured in triplicate, and three biological replicates of the complete experiment were performed.

Construction and verification of an A. pleuropneumoniae ilvI mutant.

To construct an A. pleuropneumoniae ilvI mutant, we used a similar technique to that previously reported by our laboratory for the construction of an lrp mutant (54). The 5′ and 3′ ends of the ilvI gene from A. pleuropneumoniae AP100 were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR and cloned into pUC18. Primers MM727 and MM512 (Table 2) were used to amplify a 653-bp fragment from the 5′ end of the ilvI gene, which was digested with SphI and NsiI. Primers MM513 and MM734 were used to amplify a 789-bp fragment from the 3′ end of the gene, which was digested with NsiI and SalI. These amplicons were ligated into pUC18 which had been digested with SphI and SalI, resulting in pTW429, which contains the ilvI gene with 259 bp deleted from the center of the gene. Next, the Kan promoter-chloramphenicol resistance (Cmr) cassette was digested from pRL100 with PstI and ligated into the newly generated NsiI site of pTW429 to generate pRL101. The 2.5-kb insert containing ilvI-5′-KanP-cat-ilvI-3′ was digested from pRL101 with SphI and SacI and ligated into SphI/SacI-digested pGP704SacKan to generate pRL102. This conjugal suicide plasmid was electroporated into E. coli S17-1(λpir) and conjugated into nalidixic acid-resistant A. pleuropneumoniae AP225 as previously described (35). Transconjugants were isolated on BHIV agar supplemented with 2 μg of chloramphenicol/ml and 50 μg of nalidixic acid/ml. Screening for single- or double-crossover mutants was performed by PCR analysis of the ilvI locus. A single-crossover transconjugant (AP364) was exposed to chloramphenicol selection and sucrose counterselection, as previously described (35), to generate a double-crossover ilvI mutant. This mutant, designated AP365, was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot to contain the deleted-disrupted ilvI gene and the Cmr cassette in the appropriate location in the AP225 chromosome but not the pGP704 vector, the kanamycin resistance gene, or the sacR-sacB cassette.

Preparation of challenge inocula.

Bacterial cultures were grown at 35°C, shaking at 160 rpm, in heart infusion broth containing 10 μg of V factor/ml and 5 mM CaCl2 to an OD520 of 0.8. Cells were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 5,000 × g, washed once with sterile PBS, diluted in PBS to the appropriate cell density, and administered within 60 min of preparation. The actual CFU/ml in the inocula were calculated by viable cell count on BHIV agar.

Experimental infection of pigs.

Three separate experimental infection experiments were performed. In the first experiment, 15 10-week-old specific-pathogen-free (SPF) Yorkshire-Landrace crossbred pigs (Whiteshire Hamroc, Albion, IN) were divided into five groups of three pigs by a random-stratified sampling procedure, balancing each group for body weight. Group 1 was challenged by percutaneous intratracheal inoculation with 4 × 106 CFU of wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae AP225 in 10 ml of PBS, as previously described (23, 28). Group 2 received 4 × 106 CFU of AP359, an lrp mutant of AP225 (54). Group 3 received 2 × 107 CFU of AP359. Group 4 received 4 × 106 CFU of AP359 complemented with plasmid pTW415, which contains the lrp gene in a pGZRS18 vector (54). Group 5 received 10 ml of PBS.

In the second experiment, eight 10-week-old SPF pigs were divided into four groups of two pigs. Group 1 was challenged by intratracheal inoculation with 106 CFU of wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae AP225 in 10 ml of PBS. Group 2 received 106 CFU of AP359, the lrp mutant, by intratracheal inoculation. Group 3 received a mixture of 5 × 105 CFU each of the wild type and the mutant intratracheally. Group 4 received with 2.5 × 106 each of the wild type and the mutant in 2 ml of PBS, inoculated intranasally.

In the third experiment, 10 10-week-old SPF pigs were divided into four groups. Group 1 (three pigs) received 106 CFU of AP225. Group 2 (three pigs) received 5 × 105 CFU each of the wild type and the lrp mutant. Group 3 (two pigs) received 5 × 105 CFU of the wild type and the ilvI mutant. Group 4 (two pigs) received PBS only. All pigs in this experiment were inoculated intratracheally.

After experimental infection, pigs were monitored for the development of clinical signs of pleuropneumonia, including elevated rectal temperature, increased respiratory rate, dyspnea, decreased appetite, and decreased activity (depression), as previously described (23, 28). Pigs were euthanized by lethal injection either when mild-to-moderate clinical signs, particularly dyspnea and/or depression, were seen or at the end of the experiment. All animals were necropsied, and lungs were examined macroscopically for pleuropneumonia lesions. The percentage of lung tissue and pleural surface area affected was estimated for each of the seven lung lobes, and the total percent pneumonia and pleuritis was calculated by using a formula that weights the contribution of each lung lobe to the total lung volume (28). BALF and lung tissue samples from six areas of the lungs were collected and processed for culture and histopathology in all experiments and for quantitative plate counts in experiments 2 and 3. All animal use protocols were approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Determination of competitive indices.

For in vivo competitive index determination, serial 10-fold dilutions of BALF samples and of lung samples homogenized in a Stomacher-80 (Seward Laboratory Systems, Bohemia, NY) were plated on BHIV agar containing 25 μg of nalidixic acid/ml for a total viable count of wild-type and mutant bacteria and on BHIV containing 1 μg of chloramphenicol/ml to select for the mutants. The numbers of wild-type bacteria were calculated as the CFU on BHIV containing nalidixic acid minus the CFU on BHIV containing chloramphenicol. The competitive index for each sample was calculated by using the following formula: the competitive index at time X = the ratio of mutant to the wild type at time X/the ratio of the mutant to the wild type at time zero. The average competitive index for each animal was calculated as the average of all seven specimens (BALF plus lung), with the exception that data for any specimen with no growth were excluded. Similar methods were used to calculate competitive indices in broth media.

Determination of MICs of AHAS inhibitors.

Four sulfonylurea herbicide compounds—metsulfuron methyl, primisulfuron methyl, and chlorsulfuron (all purchased from Riedel-de-Haen Laborchemikalien, Seelze, Germany) and chlorimuron ethyl (Chem Service, West Chester, PA)—and the two imidazolinone herbicide compounds imazapyr and imazaquin (Riedel-de-Haen) were tested for their ability to inhibit the growth of A. pleuropneumoniae in CDM+BCAA and CDM−BCAA. Serial twofold dilutions of each inhibitor were made in CDM+BCAA and CDM−BCAA in either test tubes or microtiter plates. A. pleuropneumoniae AP100 was grown overnight on BHIV agar and suspended in either CDM+BCAA or CDM−BCAA, and this suspension was used to inoculate both tubes and microtiter plate wells at a concentration of ∼5 × 107 CFU/ml. Tubes were incubated overnight at 35°C shaking at 160 rpm; microtiter plates were incubated overnight at 35°C under 5% CO2. MICs were determined as the lowest concentration of chemical compound that inhibited growth. The full experiment was repeated four times.

RESULTS

Analysis of free amino acid concentration in porcine pulmonary ELF.

To determine whether BCAA are present in only limited amounts in the porcine lung, we measured the concentrations of free amino acids in porcine plasma and BALF from healthy Yorkshire-Landrace feeder pigs and calculated the levels of free amino acids in pulmonary ELF using urea as a marker of dilution. Free amino acid concentrations in porcine plasma and ELF are shown in Table 3. The amino acid concentrations found in plasma were similar to those previously reported for porcine plasma (11). Many amino acids, including the essential amino acids lysine and threonine, were present in ELF at ∼50% of the concentration in plasma, and aspartic acid and glutamic acid were present in higher concentrations in ELF than in plasma. In contrast, for the BCAA leucine, isoleucine, and valine, the available levels in pulmonary ELF ranged from 8.4 to 30 μmol/liter, which was 9.8 to 16.8% of the levels found in porcine plasma. The concentrations of BCAA in porcine ELF were 10 to 20% of the amounts of these amino acids in the CDM used for A. pleuropneumoniae (55).

TABLE 3.

Concentration of free amino acids in porcine plasma and pulmonary ELF

| Amino acida | Amino acid concn in μmol/liter (avg ± SD) |

Avg ELF/ plasma ratio (%)b | Amino acid concn in CDM in μmol/liter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | ELF | |||

| Alanine | 509 ± 204 | 92.9 ± 45.2 | 20.5 | 370 |

| Arginine | 29.6 ± 39.1 | 2.6 ± 5.7 | 24.4 | 240 |

| Aspartic acid | 5.9 ± 3.9 | 47.9 ± 25.8 | 640 | 1,250 |

| Cysteine | 71.7 ± 15.8 | 8.7 ± 10.9 | 10.5 | 700 |

| Glutamic acid | 132 ± 41.7 | 172 ± 80.4 | 114 | 2,950 |

| Glutamine | 926 ± 612 | 76.3 ± 61.4 | 12.8 | 110 |

| Glycine | 816 ± 166 | 291 ± 177 | 38.7 | 110 |

| Histidine | 15.7 ± 20.5 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 59.9 | 43 |

| Isoleucine* | 80.6 ± 9.8 | 8.4 ± 9.5 | 9.8 | 80 |

| Leucine* | 146 ± 25.7 | 25.5 ± 21.8 | 16.6 | 230 |

| Lysine* | 57.1 ± 82.3 | 11.9 ± 26.7 | 54.2 | 90 |

| Methionine* | 27.7 ± 7.2 | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 5.2 | 30 |

| Phenylalanine* | 68.3 ± 18.1 | 18.1 ± 11.8 | 26.1 | 50 |

| Proline | 820 ± 206 | 345 ± 202 | 46.2 | 140 |

| Serine | 125 ± 26.4 | 58.2 ± 39.2 | 42.9 | 160 |

| Threonine* | 63.6 ± 11.9 | 28.2 ± 15.9 | 46.8 | 140 |

| Tyrosine | 62.2 ± 13.1 | 5.5 ± 4.1 | 9.2 | 130 |

| Valine* | 171 ± 30 | 30.4 ± 23.4 | 16.8 | 170 |

Values for asparagine, cystine, and tryptophan were below detectable limits on most or all samples. *, Essential amino acid.

ELF/plasma amino acid concentration ratios were calculated for each pig, and the averages of these ratios are presented.

Expression of genes involved in BCAA biosynthesis in CDM.

We have previously shown that A. pleuropneumoniae ilvI, which is required for BCAA biosynthesis, is upregulated both in vivo during infection (22) and in CDM lacking BCAA (CDM−BCAA) compared to complete CDM (CDM+BCAA) (55) and that leucine-responsive regulatory protein, encoded by the gene lrp, is required for the response of ilvI to BCAA limitation (54). To determine whether expression of ilvI and lrp correlates with the concentrations of BCAA available in the porcine lung, we used luciferase reporter assays and quantitative RT-PCR to measure the expression of these genes in CDM samples containing various concentrations of BCAA.

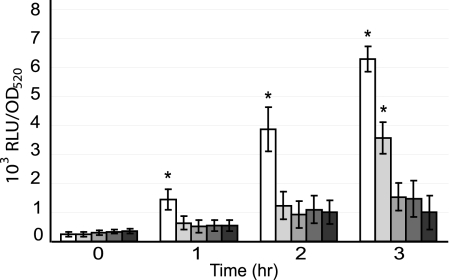

Expression of ilvI, as measured using a luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 1), increased rapidly in CDM−BCAA (0% BCAA), with a 6-fold increase at 1 h and a 26-fold increase at 3 h, compared to the 0-h time point. ilvI expression was significantly higher (P ≤ 0.02) in CDM−BCAA at 1, 2, and 3 h than in all other concentrations of BCAA tested. Expression of ilvI also increased significantly, albeit more slowly, in CDM plus 10% BCAA, reaching 14-fold times the baseline level by 3 h, which was significantly increased compared to expression in 20, 50, and 100% BCAA (P ≤ 0.01).

FIG. 1.

Expression from the ilvI promoter in CDM containing various concentrations of BCAA. A. pleuropneumoniae AP225/pIviI was grown in CDM containing 0, 10, 20, 50, and 100% of the amount of BCAA in complete CDM+BCAA. Growth was measured as the OD520, and the luciferase activity expressed from the ilvI promoter-luxAB fusions was measured as RLU. Luciferase activity was normalized to RLU per OD520 for each sample. The data are presented as the means ± the standard deviations from three separate experiments. Asterisks indicate values that are significantly different (P ≤ 0.02) from all other values at the same time point, as determined by using a Student t test.

We also measured changes in expression of both ilvI and lrp in CDM containing different concentrations of BCAA by quantitative RT-PCR (Table 4). At 1 h after a shift to fresh medium, the expression of ilvI was strongly upregulated in CDM−BCAA compared to CDM plus 100% BCAA and moderately upregulated in CDM plus 10% and plus 20% BCAA, which paralleled the results seen with the reporter assays. Expression of lrp was also upregulated in CDM−BCAA and CDM plus 10% BCAA, although to a much smaller degree than ilvI. The results using reporter assays and Q-PCR indicated that expression of ilvI and lrp was highest in CDM containing no BCAA but also increased in CDM containing the low concentrations of BCAA found in porcine ELF.

TABLE 4.

Q-PCR analysis of ilvI and lrp expression

| Medium | Avg ± SDa |

|

|---|---|---|

| ilvI | lrp | |

| CDM + 0% BCAA | 27.1 ± 0.32 | 2.82 ± 0.48 |

| CDM + 10% BCAA | 6.93 ± 1.32 | 2.35 ± 0.34 |

| CDM + 20% BCAA | 6.21 ± 1.99 | 1.89 ± 0.72 |

| CDM + 50% BCAA | 3.91 ± 1.91 | 1.70 ± 0.93 |

Data are presented as the ratio of the concentration of specific RNA from cultures grown in the medium indicated divided by the concentration of RNA from cultures grown in CDM + 100% BCAA. Transcript levels for each gene were normalized to the level of 16S rRNA. The data represent the average of triplicate samples from two replicate experiments.

Growth of wild-type, ilvI mutant, and lrp mutant A. pleuropneumoniae in CDM.

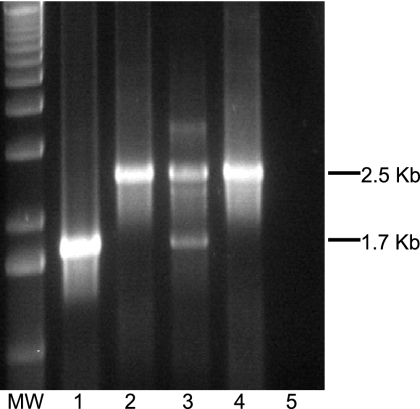

To investigate whether the levels of BCAA in porcine ELF are sufficient for the growth and virulence of A. pleuropneumoniae that is unable to synthesize these amino acids, we constructed A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 strains with mutations in the ilvI gene (AP365) (see Materials and Methods) and in the lrp gene (AP359) (54). The construction of the ilvI mutant was confirmed by both PCR and Southern blot analyses. PCR analysis showed the predicted 2.5-kb product with ilvI-specific primers in AP365, the double-crossover mutant, compared to a 1.7-kb product in wild-type AP225; both products were seen with AP364, a single-crossover mutant (Fig. 2). In addition, AP365 was shown to contain the Kan-promoter-Cmr cassette in a chromosomal location immediately upstream of the ilvH gene and to lack the pGP704 vector (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Confirmation of the ilvI mutant. PCR was performed using A. pleuropneumoniae ilvI-specific primers MM727 and MM734 and the following templates: AP225 wild-type genomic DNA (lane 1), AP365 double-crossover ilvI mutant (lane 2), AP364 single-crossover ilvI mutant (lane 3), knockout plasmid pRL102 (lane 4), and no DNA (lane 5).

Growth of wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae AP100, the ilvI mutant, a complemented ilvI mutant containing plasmid pRL103, the lrp mutant, and a complemented lrp mutant containing plasmid pTW415 were compared on CDM agar plates containing various concentrations of BCAA. Both mutants grew well on 100 and 50% BCAA but showed reduced growth on 20% BCAA, a faint haze of growth on 10% BCAA, and no growth on 0% BCAA (data not shown). In contrast, wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae and both complemented mutants grew well on all concentrations of BCAA.

Exponential growth rates in CDM broth containing various concentrations of BCAA were determined for wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae and both ilvI and lrp mutants (Table 5). Specific growth rates were highest for all three strains in CDM plus 100% BCAA and dropped for all three strains as the concentration of BCAA in the medium dropped. The growth rates for the wild type were higher than for the lrp mutant, although both strains grew in all of the media, despite very low growth rates in CDM−BCAA. The growth rates were lowest in all media for the ilvI mutant, which failed to grow at all in CDM−BCAA and grew very poorly in CDM plus 10% BCAA.

TABLE 5.

Specific growth rates of the wild type, the ilvI mutant, and the lrp mutant in CDM containing various concentrations of BCAA

| Medium | Avg specific growth rate μ (h−1) ± SDa |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| AP100 (wild type) | AP365 (ilvI mutant) | AP359 (lrp mutant) | |

| CDM + 100% BCAA | 0.91 ± 0.08 | 0.67 ± 0.08 | 0.75 ± 0.09 |

| CDM + 20% BCAA | 0.60 ± 0.09 | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 0.53 ± 0.05 |

| CDM + 10% BCAA | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.04 |

| CDM + 0% BCAA | 0.33 ± 0.03 | NG | 0.26 ± 0.04 |

Data are presented as the averages from at least three separate growth curves. The specific growth rate μ was calculated as ln2/Td, where Td is the doubling time during exponential growth. NG, no growth.

Evaluation of virulence of A. pleuropneumoniae ilvI and lrp mutants in pigs.

To measure the relative virulence of an A. pleuropneumoniae lrp mutant, we first compared wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae AP225, the lrp mutant (AP359), and a complemented mutant (AP359/pTW415) for virulence in pigs at a relatively high infective dose of 4 × 106 CFU/pig. At this dose, all pigs except the uninfected control group developed clinical signs of pneumonia, including elevated rectal temperature, dyspnea, depression, and loss of appetite, within 4 to 8 h postinfection, and most of the infected animals were euthanized due to moderate-to-severe dyspnea and/or depression within 16 to 20 h postinfection. At this dose, there were no significant differences between the groups receiving wild-type AP225, the lrp mutant, and the complemented mutant in either percent pneumonia (average = 8.1, 17.3, and 14.3%, respectively), maximum temperature (average = 106.1, 106.2, and 104.0°F, respectively), maximum respiratory rate (85, 85, and 86 breaths/min, respectively), or other parameters measured. The group of pigs that received the lrp mutant at a higher dose of 2 × 107 CFU developed disease more rapidly, with all three animals showing clinical signs at 4 h postinfection and requiring euthanasia between 10 and 14 h postinfection. This group had a higher average percent pneumonia of 36.6%. A. pleuropneumoniae was cultured from all infected animals but not from uninfected controls. Gross pathology showed typical lesions of severe pleuropneumonia in all infected animals, including hemorrhage, regions of necrosis with fibrin deposits, congestion, edema, and consolidation. Histopathology showed large areas of severe hemorrhage and necrosis surrounded by streaming neutrophils, with bacteria visible within these lesions. There was accumulation of fibrin, blood, and necrotic debris in the affected areas. The alveolar septae were necrotic, with loss of nuclear detail and loss of delineation between air spaces, and vascular walls were inflamed. Edema and hemorrhage were evident, resulting in fluid-filled alveoli and bronchi. The animals receiving the higher dose of the lrp mutant were most severely affected, but there was no visible difference between the wild type, the lrp mutant, and the complemented mutant receiving the same dose. PBS-challenged control animals did not develop any clinical signs of pneumonia and showed no lung lesions at necropsy. In this experiment, where all animals were infected with a high infective dose and rapidly developed disease, the A. pleuropneumoniae lrp mutant showed no loss in virulence compared to wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae.

Although the methods used in this first experiment were similar to those we have previously used successfully to measure the attenuation of a riboflavin-requiring mutant of A. pleuropneumoniae (23), we were concerned that the high infective dose and rapid severe hemorrhagic lung damage might have masked small differences in virulence between the lrp mutant and wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae. Therefore, we used a lower infective dose and a more sensitive technique, competitive index analysis, to measure the relative virulence of both lrp and ilvI mutants in pigs in two sets of experiments. In these experiments, most pigs were infected intratracheally with 106 CFU of bacteria, either of the wild-type or mutant alone or as a mixture of 5 × 105 CFU of the wild type and 5 × 105 CFU of the mutant. To test whether lrp might be critical for initial adherence and survival in the upper respiratory tract rather than at entry into the lung, two animals were infected with a combination of the wild type and the lrp mutant by the intranasal route rather than the intratracheal route. Animals were monitored for clinical signs of disease as in the previous experiment. At this lower infective dose, all animals developed elevated rectal temperatures but otherwise showed only mild clinical signs of respiratory disease, with the exception of pigs 2199 and 2202, which developed moderate-to-severe disease. The two pigs infected with the lrp mutant alone showed less severe clinical signs, lower percent pneumonia, and less severe pathology than that seen in pigs infected with either the wild-type alone or with a mixture of wild-type and lrp mutant (data not shown).

Pigs were euthanized either as disease signs became moderate to severe or at 18, 42, and 66 h postinfection, and BALF and lung samples from six different lung locations were collected. The CFU/ml of BALF or per g of lung tissue were measured for both the wild type and the mutant, and competitive indices were calculated as a measure of how well the mutant competed with virulent wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Competitive index analysis of virulence of A. pleuropneumoniae mutantsa

| Mutant | Pig | Dose (CFU) | Route | Time postinfection (h) | Avg CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ilvI mutant | 33 | 1 × 106 | Intratracheal | 42 | 0.22 |

| 38 | 1 × 106 | Intratracheal | 66 | 0.05 | |

| lrp mutant | 35 | 1 × 106 | Intratracheal | 18 | 0.24 |

| 2199 | 1 × 106 | Intratracheal | 32 | 0.14 | |

| 29 | 1 × 106 | Intratracheal | 42 | 0.06 | |

| 41 | 1 × 106 | Intratracheal | 66 | <0.06 | |

| 2203 | 1 × 106 | Intratracheal | 66 | 0.04 | |

| 2202 | 5 × 106 | Intranasal | 18 | 0.44 | |

| 2205 | 5 × 106 | Intranasal | 42 | 0.19 |

The table includes data on all pigs from experiments 2 and 3 that received both mutant and wild-type strains. Pigs 2199, 2202, 2203, and 2205 were from experiment 2. Pigs 29, 33, 35, 38, and 41 were from experiment 3. CI, competitive index.

In these competitive index experiments, we found that neither the lrp mutant nor the ilvI mutant competed well with wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae. This was true for the lrp mutant in infections by both the intratracheal and the intranasal routes. For both mutants, the competitive index tended to drop over time, with average CIs of 0.2 to 0.4 for animals euthanized 18 h postinfection, 0.06 to 0.22 at 32 to 42 h, and 0.04 to 0.06 at 66 h. The competitive index was always lower than 1 and declined as the disease progressed. These results indicate that both the ilvI mutant and the lrp mutant are attenuated in our swine experimental infection model.

Effect of AHAS inhibitors on growth of A. pleuropneumoniae.

Six compounds that are inhibitors of plant AHAS enzymes routinely used in herbicides, namely, the sulfonylureas metsulfuron methyl, primisulfuron methyl, chlorimuron ethyl, and chlorsulfuron and the imidazolinones imazapyr and imazaquin, were tested for their ability to inhibit the growth of wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae. All four of the sulfonylureas that were tested inhibited the growth of A. pleuropneumoniae in CDM−BCAA but not CDM+BCAA (Table 7). Metsulfuron methyl was the most effective, with an MIC of 0.5 nmol/ml (0.2 μg/ml), whereas primisulfuron methyl was the least effective, with an MIC of 16 nmol/ml (7.5 μg/ml). In contrast, neither of the imidazolinones tested inhibited growth of A. pleuropneumoniae in either CDM+BCAA or CDM−BCAA.

TABLE 7.

MICs of AHAS inhibitors against A. pleuropneumoniae AP100 in CDM+BCAA and CDM−BCAA

| AHAS inhibitor | Avg MIC (nmol/ml)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| CDM+BCAA | CDM−BCAA | |

| Sulfonylureas | ||

| Chlorimuron ethyl | >2,000 | 1 |

| Chlorsulfuron | >2,000 | 2 |

| Metsulfuron methyl | 2,000 | 0.5 |

| Primisulfuron | >2,000 | 16 |

| Imidazolinones | ||

| Imazapyr | >2,000 | ≥1,000 |

| Imazaquin | >2,000 | ≥2,000 |

Average of at least four independent replicate experiments.

DISCUSSION

Our IVET studies on A. pleuropneumoniae (22, 55) and a review of other similar studies (7, 8, 21, 33, 46, 56) identified genes involved in BCAA biosynthesis as in vivo induced or required for survival and virulence in pathogens of relatively clean body sites such as the lungs, cerebrospinal fluid, and bloodstream, but not in pathogens of the gastrointestinal tract. Further, we found that 25% of the A. pleuropneumoniae promoters that we had identified as specifically induced in vivo were upregulated in vitro in CDM lacking BCAA (55). These studies suggested that a previously unrecognized environmental condition—limitation of the BCAA leucine, isoleucine, and valine—exists in the healthy mammalian lung, that bacteria can sense this environmental condition and respond to it, and that pulmonary pathogens unable to synthesize BCAA will be attenuated. Since no data were available on the actual concentrations of BCAA in mammalian lung fluids, we first measured the free amino concentrations in porcine pulmonary ELF and serum. We found that most amino acids, with the exception of aspartic acid and glutamic acid, were present in lower concentrations in ELF than in serum, although many were present at roughly 40 to 50% of the serum level, including the essential amino acids lysine and threonine. In contrast, the essential BCAA were present in pulmonary ELF at ∼10 to 17% of the concentration in serum. This is the first report of actual free amino acid concentrations in porcine ELF. When tested in vitro in a CDM, the low concentrations of BCAA found in pulmonary ELF led to reduced growth rates of wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae, as well as to increased expression of genes required for BCAA biosynthesis. During infection, even a slight reduction in growth rate of a pathogen can allow the host natural defenses to clear the pathogen before disease develops.

To test whether the ability to synthesize BCAA is critical for survival and virulence of A. pleuropneumoniae in its natural swine host, we constructed two mutants that require exogenous BCAA for growth. The first mutant contained a mutation in the ilvI gene, which encodes the large subunit of acetohydroxy acid synthase, an enzyme required for biosynthesis of all three BCAA. The A. pleuropneumoniae genome contains two sets of genes that encode putative AHAS enzymes, ilvIH and ilvGM (18, 61), and there was concern that the ilvGM-encoded enzyme might substitute for that encoded by ilvIH. However, the ilvI mutant failed to grow in vitro in the absence of exogenous BCAA, indicating that the ilvGM-encoded AHAS enzyme did not substitute for the ilvIH-encoded AHAS under these conditions.

The second mutant was constructed to knock out lrp, which encodes a global regulator of BCAA synthesis and degradation in E. coli (10, 12, 38). We have previously shown that an lrp homologue is required for ilvI expression in A. pleuropneumoniae (54). Lrp is frequently a pleiotropic regulator of a wide variety of genes in addition to those involved in amino acid biosynthesis and catabolism, although the Lrp regulon varies between even closely related species (14, 30). Lrp has also been shown to regulate a variety of virulence-associated genes in many other pathogens (2, 19, 24, 29, 32, 60). Although Lrp is essential for virulence in Xenorhabdus nematophila (15, 29), it appears to act as a virulence repressor in Salmonella enterica subtype Typhimurium (2).

In initial attenuation experiments comparing wild-type and Lrp− A. pleuropneumoniae in experimental infections in pigs using the high inoculating dose of 4 × 106 CFU, the pigs rapidly developed severe hemorrhagic pneumonia, and there was no obvious difference in severity or pathology between the wild-type and mutant infections. However, when a lower inoculating dose of 106 was used, the pigs infected with the lrp mutant showed less severe clinical signs and less severe pathology than those infected with the wild type. We chose to use a competitive index design for further studies. Competitive index experiments can be a more sensitive measure of virulence attenuation than standard infection experiments to calculate differential LD50 values for wild-type and mutant strains (4). In competitive index experiments using a combined dose of 1 × 106 CFU for intratracheal inoculation and 5 × 106 CFU for intranasal inoculation, we found that neither the lrp mutant nor the ilvI mutant competed well with wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae and that the lrp mutant was attenuated in animals infected by both methods.

The observation that the lrp mutant is virulent at high doses but attenuated at lower doses might be explained by the disease process. At high infecting doses, lung damage occurs very rapidly in this disease. This is most likely due to the extracellular Apx toxins, since growth of the infecting inoculum under conditions that enhance Apx toxin production leads to increased virulence and increased rapidity of disease progression. The Apx toxins, which can be hemolytic or cytotoxic or both, are the key virulence factors leading to severe lung damage (47). These toxins kill neutrophils that are attracted to the site of infection, releasing toxic neutrophil contents into tissues, which causes tissue damage; the Apx toxins are also cytotoxic for porcine alveolar epithelial cells (27, 51). The severe damage to cells and tissues that results can lead to release of cytoplasmic contents such as hemoglobin and free amino acids from host cells. In addition, A. pleuropneumoniae produces extracellular proteases that may degrade proteins within the lung tissues (36, 37). Together, Apx toxins plus secreted proteases could release sufficient BCAA to allow the lrp mutant to survive and grow. In contrast, at lower infecting doses, there is generally a lag of several hours before the development of clinical signs, and the reduction in tissue damage at the early stages of infection may result in decreased release of free amino acids from host cells and therefore insufficient levels of BCAA to allow multiplication of the infecting lrp or ilvI mutants. It is likely that BCAA are present in limiting amounts at the initial stages of A. pleuropneumoniae infection and that the damage caused by the disease leads to increased availability of BCAA.

We observed that limitation of BCAA stimulated the expression of both ilvI and lrp in the present study, with levels of gene expression increased with decreasing concentrations of BCAA. Expression measured both by Q-PCR to quantitate RNA transcripts for ilvI and lrp and by luciferase reporter assay for ilvI showed elevated RNA and reporter enzyme at 1 h after a shift to conditions of BCAA limitation. We had previously reported that BCAA limitation induced expression in vitro of 25% of the A. pleuropneumoniae gene promoters identified as specifically expressed in vivo in our IVET studies (55). These results suggest that low levels of BCAA may be an important environmental cue regulating gene expression in A. pleuropneumoniae and other pulmonary pathogens. Recent studies in our laboratory to identify the A. pleuropneumoniae transcriptome in response to limitation of BCAA indicate that expression of many genes is modulated by BCAA limitation, including increased expression of several adhesins (M. H. Mulks, unpublished data). These results suggest a model in which BCAA limitation acts as an early signal regulating expression of genes required for survival and virulence, such as adhesins, whose expression may later be altered by increased levels of BCAA.

The results reported here demonstrate that the ability to synthesize BCAA is critical for the survival and virulence of A. pleuropneumoniae in the swine lung. These results suggested that BCAA biosynthesis is a potential target for the development of antimicrobials against A. pleuropneumoniae and similar pathogens. Many AHAS inhibitors have been developed as potent herbicides that show little toxicity for mammals (16). We tested two classes of inhibitors of AHAS enzymes, sulfonylureas and imidazolinones, for their ability to inhibit growth of A. pleuropneumoniae. We predicted that these inhibitors would have minimal effect on growth in CDM+BCAA, where the ability to synthesize BCAA is not required because there are sufficient levels of exogenous BCAA, and would have significant effect on growth in CDM−BCAA, where the bacteria must be able to synthesize BCAA. Our results show that all four sulfonylureas that were tested inhibited growth of wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae in CDM−BCAA but not in CDM+BCAA. However, neither imidazolinone had any effect on growth in either medium. Since both classes of compounds inhibit AHAS enzymes, the difference is likely to be in uptake of the compound into bacterial cells. Sulfonylureas have also been shown to inhibit growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis both in vitro and in a mouse model (25, 44) and of Brucella suis in macrophages (5). These results indicate that AHAS inhibitors have excellent potential for development as antimicrobials against infections of the respiratory tract or other “clean” body sites, although their utility against fulminant A. pleuropneumoniae infection may be limited in vivo due to the effect of the Apx toxins. However, only a few pulmonary pathogens, such as A. pleuropneumoniae and Mannheimia haemolytica, produce large amounts of repeat-in-toxin toxins, and AHAS inhibitors may function well in vivo against pathogens that cause less destruction of tissues and blood cells, or as prophylactic measures against spread of diseases such as porcine pleuropneumonia within a herd.

In summary, our IVET studies on A. pleuropneumoniae led us to hypothesize that BCAA limitation is an environmental condition encountered by this pathogen in the healthy pig lung and that the ability to synthesize BCAA would be critical for full virulence of this pathogen. We have shown that BCAA are indeed present in only limited amounts in porcine pulmonary ELF, that the growth of wild-type A. pleuropneumoniae was reduced in vitro when such low levels of BCAA were available and was inhibited by sulfonylureas, and that two mutants unable to synthesize BCAA were attenuated in an experimental infection model in swine. We have also shown that the concentration of available BCAA affects expression of ilvI and lrp, with increased expression correlating with decreased BCAA concentration. Further studies to identify the full A. pleuropneumoniae transcriptome that responds to BCAA limitation and regulatory molecules that control this response are in progress. These results demonstrate how data from IVET and signature-tagged mutagenesis studies can be used to define the environment encountered by pathogens in vivo and to suggest promising avenues for the development of new tools to control infectious diseases.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Michigan State University Center for Microbial Pathogenesis, the Respiratory Research Initiative, and the College of Veterinary Medicine Genetics Endowment Fund. T.K.W. was supported in part by a USDA National Needs Training Program graduate fellowship.

We thank George Bohart for assistance with collection of BALF and James Crawford for assistance with the animal infection studies.

Editor: B. A. McCormick

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 August 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abul-Milh, M., S. E. Paradis, J. D. Dubreuil, and M. Jacques. 1999. Binding of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae lipopolysaccharides to glycosphingolipids evaluated by thin-layer chromatography. Infect. Immun. 67:4983-4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baek, C.-H., S. Wang, K. L. Roland, and R. Curtiss III. 2009. Leucine-responsive regulatory protein (Lrp) acts as a virulence repressor in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 191:1278-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baughman, R. P., C. H. Bosken, R. G. Loudon, P. Hurtubise, and T. Wesseler. 1983. Quantitation of bronchoalveolar lavage with methylene blue. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 128:266-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beuzon, C. R., and D. W. Holden. 2001. Use of mixed infections with Salmonella strains to study virulence genes and their interactions in vivo. Microbes Infect. 3:1345-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boigegrain, R.-A., J.-P. Liautard, and S. Kohler. 2005. Targeting of the virulence factor acetohydroxyacid synthase by sulfonylureas results in inhibition of intramacrophagic multiplication of Brucella suis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3922-3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosse, J. T., H. Janson, B. J. Sheehan, A. J. Beddek, A. N. Rycroft, J. S. Kroll, and P. R. Langford. 2002. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae: pathobiology and pathogenesis of infection. Microbes Infect. 4:225-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyce, J. D., I. Wilkie, M. Harper, M. L. Paustian, V. Kapur, and B. Adler. 2004. Genomic-scale analysis of Pasteurella multocida gene expression during growth within liver tissue of chickens with fowl cholera. Microbes Infect. 6:290-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyce, J. D., I. Wilkie, M. Harper, M. L. Paustian, V. Kapur, and B. Adler. 2002. Genomic scale analysis of Pasteurella multocida gene expression during growth within the natural chicken host. Infect. Immun. 70:6871-6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennan, R. G., and T. M. Link. 2007. Hfq structure, function, and ligand binding. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:125-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brinkman, A. B., T. J. Ettema, W. M. de Vos, and J. van der Oost. 2003. The Lrp family of transcriptional regulators. Mol. Microbiol. 48:287-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai, X., H. Chen, P. J. Blackall, Z. Yin, L. Wang, Z. Liu, and M. Jin. 2005. Serological characterization of Haemophilus parasuis isolates from China. Vet. Microbiol. 111:231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calvo, J. M., and R. G. Matthews. 1994. The leucine-responsive regulatory protein, a global regulator of metabolism in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 58:466-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chin, N., J. Frey, C. F. Chang, and Y. F. Chang. 1996. Identification of a locus involved in the utilization of iron by Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 143:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho, B.-K., C. L. Barrett, E. M. Knight, Y. S. Park, and B. O. Palsson. 2008. Genome-scale reconstruction of the Lrp regulatory network in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105:19462-19467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowles, K. N., C. E. Cowles, G. R. Richards, E. C. Martens, and H. Goodrich-Blair. 2007. The global regulator Lrp contributes to mutualism, pathogenesis and phenotypic variation in the bacterium Xenorhabdus nematophila. Cell Microbiol. 9:1311-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duggleby, R. G., and S. S. Pang. 2000. Acetohydroxyacid synthase. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 33:1-36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenwick, B. W., B. I. Osburn, and H. J. Olander. 1986. Isolation and biological characterization of two lipopolysaccharides and a capsular-enriched polysaccharide preparation from Haemophilus pleuropneumoniae. Am. J. Vet. Res. 47:1433-1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foote, S. J., J. T. Bosse, A. B. Bouevitch, P. R. Langford, N. M. Young, and J. H. Nash. 2008. The complete genome sequence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae L20 (serotype 5b). J. Bacteriol. 190:1495-1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser, G. M., L. Claret, R. Furness, S. Gupta, and C. Hughes. 2002. Swarming-coupled expression of the Proteus mirabilis hpmBA haemolysin operon. Microbiology 148:2191-2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frey, J. 1995. Virulence in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and RTX toxins. Trends Microbiol. 3:257-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuller, T. E., M. J. Kennedy, and D. E. Lowery. 2000. Identification of Pasteurella multocida virulence genes in a septicemic mouse model using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Microb. Pathog. 29:25-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuller, T. E., R. J. Shea, B. J. Thacker, and M. H. Mulks. 1999. Identification of in vivo induced genes in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Microb. Pathog. 27:311-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuller, T. E., B. J. Thacker, and M. H. Mulks. 1996. A riboflavin auxotroph of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae is attenuated in swine. Infect. Immun. 64:4659-4664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gally, D. L., T. J. Rucker, and I. C. Blomfield. 1994. The leucine-responsive regulatory protein binds to the fim switch to control phase variation of type 1 fimbrial expression in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 176:5665-5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grandoni, J. A., P. T. Marta, and J. V. Schloss. 1998. Inhibitors of branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis as potential antituberculosis agents. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 42:475-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haesebrouck, F., K. Chiers, I. Van Overbeke, and R. Ducatelle. 1997. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae infections in pigs: the role of virulence factors in pathogenesis and protection. Vet. Microbiol. 58:239-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jansen, R., J. Briaire, H. E. Smith, P. Dom, F. Haesebrouck, E. M. Kamp, A. L. Gielkens, and M. A. Smits. 1995. Knockout mutants of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 that are devoid of RTX toxins do not activate or kill porcine neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 63:27-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jolie, R. A., M. H. Mulks, and B. J. Thacker. 1995. Cross-protection experiments in pigs vaccinated with Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae subtypes 1A and 1B. Vet. Microbiol. 45:383-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin, W., G. Kovacikova, and K. Skorupski. 2007. The quorum sensing regulator HapR downregulates the expression of the virulence gene transcription factor AphA in Vibrio cholerae by antagonizing Lrp- and VpsR-mediated activation. Mol. Microbiol. 64:953-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lintner, R., P. Mishra, P. Srivastava, B. Martinez-Vaz, A. Khodursky, and R. Blumenthal. 2008. Limited functional conservation of a global regulator among related bacterial genera: Lrp in Escherichia coli, Proteus, and Vibrio. BMC Microbiol. 8:60-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCourt, J. A., and R. G. Duggleby. 2006. Acetohydroxyacid synthase and its role in the biosynthetic pathway for branched-chain amino acids. Amino Acids 31:173-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McFarland, K. A., S. Lucchini, J. C. Hinton, and C. J. Dorman. 2008. The leucine-responsive regulatory protein, Lrp, activates transcription of the fim operon in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium via the fimZ regulatory gene. J. Bacteriol. 190:602-612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mei, J. M., F. Nourbakhsh, C. W. Ford, and D. W. Holden. 1997. Identification of Staphylococcus aureus virulence genes in a murine model of bacteraemia using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 26:399-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mulks, M. H., and J. M. Buysse. 1995. A targeted mutagenesis system for Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Gene 165:61-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Negrete-Abascal, E., R. M. Garcia, M. E. Reyes, D. Godinez, and M. de la Garza. 2000. Membrane vesicles released by Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae contain proteases and Apx toxins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 191:109-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Negrete Abascal, E., V. R. Tenorio, J. J. Serrano, C. Garcia, and M. de la Garza. 1994. Secreted proteases from Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1 degrade porcine gelatin, hemoglobin, and immunoglobulin A. Can. J. Vet. Res. 58:83-86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newman, E. B., and R. Lin. 1995. Leucine-responsive regulatory protein: a global regulator of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:747-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rennard, S. I., G. Basset, D. Lecossier, K. M. O'Donnell, P. Pinkston, P. G. Martin, and R. G. Crystal. 1986. Estimation of volume of epithelial lining fluid recovered by lavage using urea as marker of dilution. J. Appl. Physiol. 60:532-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ried, J. L., and A. Collmer. 1987. An nptI-sacB-sacR cartridge for constructing directed, unmarked mutations in gram-negative bacteria by marker exchange-eviction mutagenesis. Gene 57:239-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rioux, S., C. Begin, D. Dubreuil, and M. Jacques. 1997. Isolation and characterization of LPS mutants of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 1. Curr. Microbiol. 35:139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosey, E. L., M. J. Kennedy, and R. J. Yancey. 1996. Dual flaA1 flaB1 mutant of Serpulina hyodysenteriae expressing periplasmic flagella is severely attenuated in a murine model of swine dysentery. Infect. Immun. 64:4154-4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Puhler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sohn, H., K.-S. Lee, Y.-K. Ko, J.-W. Ryu, J.-C. Woo, D.-W. Koo, S.-J. Shin, S.-J. Ahn, A.-R. Shin, C.-H. Song, E.-K. Jo, J.-K. Park, and H.-J. Kim. 2008. In vitro and ex vivo activity of new derivatives of acetohydroxyacid synthase inhibitors against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 31:567-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spackman, D. H., W. H. Stein, and S. Moore. 1958. Automatic recording apparatus for use in chromatography of amino acids. Anal. Chem. 30:1190-1206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun, Y.-H., S. Bakshi, R. Chalmers, and C. M. Tang. 2000. Functional genomics of Neisseria meningitidis pathogenesis. Nat. Med. 6:1269-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tascon, R. I., J. A. Vazquez-Boland, C. B. Gutierrez-Martin, I. Rodriguez-Barbosa, and E. F. Rodriguez-Ferri. 1994. The RTX haemolysins ApxI and ApxII are major virulence factors of the swine pathogen Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae: evidence from mutational analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 14:207-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor, D. J. 1999. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae, p. 343-354. In B. E. Straw, S. D'Allaire, W. L. Mengeling, and D. J. Taylor (ed.), Diseases of swine, 8th ed. Iowa State University Press, Ames, IA.

- 49.Toledo-Arana, A., F. Repoila, and P. Cossart. 2007. Small non-coding RNAs controlling pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:182-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tonpitak, W., S. Thiede, W. Oswald, N. Baltes, and G. F. Gerlach. 2000. Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae iron transport: a set of exbBD genes is transcriptionally linked to the tbpB gene and required for utilization of transferrin-bound iron. Infect. Immun. 68:1164-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van de Kerkhof, A., F. Haesebrouck, K. Chiers, R. Ducatelle, E. M. Kamp, and M. A. Smits. 1996. Influence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae and its metabolites on porcine alveolar epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 64:3905-3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Leengoed, L. A. M. G., and E. B. Kamp. 1989. A method for bronchoalveolar lavage in live pigs. Vet. Q. 11:65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vieira, J., and J. Messing. 1982. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene 19:259-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wagner, T. K., and M. H. Mulks. 2007. Identification of the Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae leucine-responsive regulatory protein and its involvement in the regulation of in vivo-induced genes. Infect. Immun. 75:91-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wagner, T. K., and M. H. Mulks. 2006. A subset of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae in vivo induced promoters respond to branched-chain amino acid limitation. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 48:192-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang, J., A. Mushegian, S. Lory, and S. Jin. 1996. Large-scale isolation of candidate virulence genes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by in vivo selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:10434-10439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ward, C. K., and T. J. Inzana. 1994. Resistance of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae to bactericidal antibody and complement is mediated by capsular polysaccharide and blocking antibody specific for lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 153:2110-2121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ward, C. K., M. L. Lawrence, H. P. Veit, and T. J. Inzana. 1998. Cloning and mutagenesis of a serotype-specific DNA region involved in encapsulation and virulence of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 5a: concomitant expression of serotype 5a and 1 capsular polysaccharides in recombinant A. pleuropneumoniae serotype 1. Infect. Immun. 66:3326-3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.West, S. E., M. J. Romero, L. B. Regassa, N. A. Zielinski, and R. A. Welch. 1995. Construction of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors: expression of antibiotic-resistance genes. Gene 160:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weyand, N. J., and D. A. Low. 2000. Regulation of Pap phase variation. Lrp is sufficient for the establishment of the phase off pap DNA methylation pattern and repression of pap transcription in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 275:3192-3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu, Z., Y. Zhou, L. Li, R. Zhou, S. Xiao, Y. Wan, S. Zhang, K. Wang, W. Li, H. Jin, M. Kang, B. Dalai, T. Li, L. Liu, Y. Cheng, L. Zhang, T. Xu, H. Zheng, S. Pu, B. Wang, W. Gu, X. L. Zhang, G. F. Zhu, S. Wang, G. P. Zhao, and H. Chen. 2008. Genome biology of Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae JL03, an isolate of serotype 3 prevalent in China. PLoS ONE. 3:e1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang, Y., J. M. Tennent, A. Ingham, G. Beddome, C. Prideaux, and W. P. Michalski. 2000. Identification of type 4 fimbriae in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 189:15-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]