Abstract

Probable transmission of an extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli strain (sequence type ST131) between a father and daughter was documented. The father developed severe, recurrent pyelonephritis with multiple small abscesses; the daughter later developed septic shock, bacteremia, and extensive emphysematous pyelonephritis. This multidrug-resistant E. coli clone appears to be highly pathogenic and transmissible.

CASE REPORT

Patient 1, a 68-year-old male, was admitted to the hospital with a 3-month history of poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, fever, weight loss, and malaise. A Foley catheter was placed for urinary retention, and urinary tract infection (UTI) was diagnosed. Therapy was started with levofloxacin but was changed to ertapenem when the urine culture revealed extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase (ESBL)-positive Escherichia coli. The patient received 10 days of ertapenem with clinical improvement and was transferred to a transitional care facility.

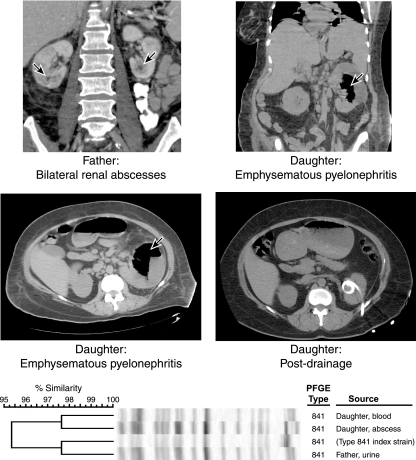

Symptoms recurred soon thereafter. Repeat urine culture again showed ESBL-positive E. coli. Piperacillin-tazobactam was given for 7 days in the transitional care facility, without symptomatic improvement. The patient was admitted to a different hospital for further evaluation and management. Blood cultures were negative. Urinalysis revealed pyuria and bacteriuria; urine culture again grew ESBL-positive E. coli. Ertapenem was resumed, but fever persisted. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography demonstrated bilateral pyelonephritis and numerous small abscesses within both kidneys (Fig. 1). The patient received 6 weeks of ertapenem, with clinical and radiographic resolution of the pyelonephritis and abscesses.

FIG. 1.

Computed tomograms (CTs) and PFGE profiles in two cases of severe pyelonephritis caused by the same E. coli strain. (Top left) Father's abdominal CT from the second hospital admission. The kidneys demonstrate patchy enhancement bilaterally, suggesting acute pyelonephritis. Both kidneys also contain several hypoattenuating foci, some of which appear to demonstrate peripheral rim enhancement, consistent with small intrarenal abscesses (arrows). (Top right and middle left) Daughter's predrainage abdominal CT. The left kidney contains air-fluid levels and mottled gas collections (arrows), compatible with emphysematous pyelonephritis. The right kidney is enlarged and somewhat inhomogeneous in attenuation, suggesting acute pyelonephritis. (Middle right) Daughter's postdrainage abdominal CT, showing a left-sided drainage catheter and resolution of the large intrarenal fluid/gas collection. (Bottom) PFGE profiles of three clinical E. coli isolates from the case patients, plus the index strain for (ST131-associated) PFGE type 841. All isolates exhibit >95% similar profiles (according to Dice coefficients).

Patient 2, the 42-year-old independently dwelling diabetic daughter of patient 1, was admitted to the hospital with septic shock and multiorgan system failure. Several weeks prior to admission, she had visited patient 1 for about 90 min during his initial admission for the ESBL-positive E. coli UTI and had used his hospital bathroom. During this brief visit, the daughter did not have any close contact with her father's health care providers. The encounter occurred at a remote hospital for which information regarding local infection control practices is unavailable. The daughter's only other encounter with her father within the preceding 6 months was a 1-h visit 2 months prior to his initial UTI episode. The daughter had not taken antimicrobials for several years prior to her present illness.

Approximately 10 days after the hospital visit with her father, patient 2 developed a nonspecific febrile illness. She received courses of azithromycin and levofloxacin without improvement. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography revealed retroperitoneal adenopathy and enlarged kidneys with inflammatory changes. Urine culture grew ESBL-positive E. coli; blood cultures were negative. She refused admission for parenteral antimicrobials and received levofloxacin, then nitrofurantoin, without improvement. Ertapenem was given for 5 days in an ambulatory infusion center, with modest improvement. She then refused further treatment and remained off antibiotics.

Two weeks later, patient 2 was found to be febrile and confused at home and was admitted urgently to the intensive care unit. She was resuscitated and received ventilator support, vasopressors, and meropenem plus vancomycin. Computed tomography revealed bilateral pyelonephritis, with extensive emphysematous changes and a large gas abscess involving the left kidney, which was drained percutaneously (Fig. 1). Blood and urine cultures grew ESBL-positive E. coli. The antimicrobial regimen was simplified to ertapenem. The patient was gradually weaned off ventilator support and vasopressor therapy and slowly defervesced. During the hospital stay, the patient remained in contact isolation and no clinically apparent transmission of the organism among health care providers occurred. Due to the extensive emphysematous pyelonephritis, the patient received 4 months of ertapenem and percutaneous drainage. Three months after stopping all antimicrobials, she remains well.

A detailed laboratory analysis of the clinical isolates was performed. According to established PCR-based methods (5), the isolates from samples obtained from patient 1 (urine from the relapsed UTI episode) and patient 2 (blood and renal abscess fluid) derived from E. coli phylogenetic group B2, exhibited the O25b rfb (lipopolysaccharide) variant, and (according to Dice similarity coefficients) had >95% similar pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) profiles (Fig. 1). They also exhibited a conserved virulence genotype that included afa and dra (encoding Dr-binding adhesins), fimH (encoding type 1 fimbriae), iha (encoding an adhesin-siderophore), iutA (encoding an aerobactin system), fyuA (encoding yersiniabactin), kpsM II (encoding a group 2 capsule), sat (encoding a secreted autotransporter toxin), usp (encoding a uropathogen-specific protein), ompT (encoding outer membrane protease), traT (associated with serum resistance), and malX (a pathogenicity island marker). They were resistant to ampicillin, ampicillin-sulbactam, extended-spectrum cephalosporins, gentamicin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and fluoroquinolones and were susceptible to amikacin, tobramycin, and carbapenems; susceptibility to piperacillin-tazobactam was variable. The presence of blaCTX-M-15 was confirmed by PCR (6). These similarities indicated that the isolates represented the same strain, consistent with transmission between father and daughter.

Membership in the E. coli sequence type ST131 group was confirmed by (i) PCR-based detection of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in gyrB and mdh and (ii) comparative random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis (5) (data not shown). The isolates' XbaI PFGE profiles corresponded with PFGE type 841, the ninth-most-common PFGE type within an internal reference library of PFGE profiles for 255 U.S. and international ST131 isolates (J. R. Johnson, unpublished data).

Commentary.

ESBL-producing gram-negative bacteria are an increasingly common cause of human infection. These organisms are frequently resistant to many of the antimicrobial agents used to treat infections with gram-negative bacteria. They were first described in 1985 and have become progressively more prevalent in the community since 2000 (8). E. coli is now one of the main gram-negative species to cause infections with ESBL-positive bacteria in humans.

Transmission of extraintestinal pathogenic and ESBL-producing E. coli bacteria occurs among household members (2, 9). These colonizing organisms have the potential to cause extraintestinal infections.

A broadly disseminated E. coli clonal group, ST131, which is associated with the CTX-M-15 ESBL, has recently been identified in Europe, Asia, and North America, including the United States (3, 5-7). One reported case of infection suggested household transmission of the causative ST131 strain (7).

This report provides strong evidence of transmission of an ESBL-positive, highly virulent E. coli strain after minimal contact between two family members. The apparent transmission was from a father, while hospitalized for pyelonephritis, to his visiting adult daughter, who shortly thereafter developed emphysematous pyelonephritis, renal abscess, bacteremia, and septic shock. E. coli isolates from both individuals were identified as representing a single pulsotype within the recently described CTX-M-15-positive ST131 clonal group, which appears to be particularly virulent and is commonly resistant to most antimicrobials used to treat infections with gram-negative bacteria.

Transmission of the causative organism is supported by both laboratory and epidemiologic evidence. Molecularly, the isolates exhibited highly similar PGFE profiles (>95% similarity according to Dice coefficients, reflecting a ≤3-band difference) and identical O types, virulence profiles, and antimicrobial resistance profiles, including the presence of blaCTX-M-15, evidence that they represented the same strain. This conclusion suggests either host-to-host transmission or parallel acquisition from a common external source. Epidemiologically, approximately 10 days before the daughter became ill she had visited her father while he was hospitalized for his initial E. coli infection and had used his hospital toilet. The toilet and/or adjacent items or surfaces may have been contaminated with the father's acute-UTI strain. The possibility of microbial spread via this mechanism is supported by environmental research describing colonization by and aerosolization of E. coli in association with household toilets (1). In contrast, the daughter had very limited previous contact with her father and had not shared any meals with him in the recent past, making shared exposures or more remote person-to-person transmission less likely. She also lacked other known risk factors for ESBL E. coli colonization such as previous antimicrobial use, hospitalization, or admission to an extended care facility, making independent acquisition of an ESBL strain (especially of the same pulsotype) unlikely.

This particular ESBL-positive E. coli strain appears to be particularly virulent. Although both patients had underlying risk factors for complications of UTI (i.e., diabetes, with or without urinary retention), the development of severe, emphysematous pyelonephritis with abscesses is quite uncommon even among individuals with such risk factors. That both the father and daughter developed renal abscesses due to the same strain implies that this strain and, by extension, ST131 isolates in general have robust intrinsic virulence potential. This assumption is consistent with the strain's virulence genotype, which is typical of previously described ST131 isolates but more extensive than typically observed among other ESBL-positive E. coli strains (4). This pattern also comports with other anecdotal evidence of unusually severe, invasive extraintestinal infections due to ST131 strains (7, 10).

In summary, we describe the occurrence of severe, emphysematous pyelonephritis with septic shock after presumed transmission of an ESBL-positive E. coli strain during limited contact between a father and daughter. The causative organism represents a recently described, highly pathogenic, ESBL-positive E. coli clonal group, which is now reported to cause extraintestinal infections widely in the United States and internationally. This emerging clonal group appears to be particularly antimicrobial resistant, virulent, and transmissible. New approaches to prevention, detection (including via the clinical microbiology laboratory), and management will be needed for this and similar strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yashwant Chudasama for his laboratory assistance. Dave Prentiss (VA Medical Center) prepared the image.

This material is based upon work supported by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs (through funding to J.R.J.). J.R.J. has received grants and/or consultancies from Bayer, Merck, Ortho-McNeil, Procter and Gamble, Rochester Medical, and Wyeth-Ayerst. Other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 September 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gerba, C. P., C. Wallis, and J. L. Melnick. 1975. Microbiological hazards of household toilets: droplet production and the fate of residual organisms. Appl. Microbiol. 30:229-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson, J. R., and C. Clabots. 2006. Sharing of virulent Escherichia coli clones among household members of a woman with acute cystitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:e101-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson, J. R., B. D. Johnston, J. H. Jorgensen, J. Lewis II, A. Robicsek, M. Menard, C. Clabots, S. J. Weissman, N. D. Hanson, R. Owens, K. Lolans, and J. Quinn. 2008. CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli in the United States: predominance of sequence type ST131 (O25:H4), abstr. K-3444. Abstr. 48th Annu. Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. (ICAAC)-Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. (IDSA) 46th Annu. Meet.

- 4.Johnson, J. R., M. A. Kuskowski, K. Owens, A. Gajewski, and P. L. Winokur. 2003. Phylogenetic origin and virulence genotype in relation to resistance to fluoroquinolones and/or extended-spectrum cephalosporins and cephamycins among Escherichia coli isolates from animals and humans. J. Infect. Dis. 188:759-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson, J. R., M. Menard, B. Johnston, M. A. Kuskowski, K. Nichol, and G. G. Zhanel. 2009. Epidemic clonal groups of Escherichia coli as a cause of antimicrobial-resistant urinary tract infections in Canada (2002-2004). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2733-2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicolas-Chanoine, M., J. Blanco, V. Leflon-Guibout, R. Demarty, M. P. Alonso, M. M. Canica, Y. Park, J. Lavigne, J. Pitout, and J. R. Johnson. 2008. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:273-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owens, R. C., P. Stogsdill, L. Yarmus, K. Lolans, J. Johnson, and J. Quinn. 2008. Community transmission in the United States (US) of a confirmed CTX-M-15-producing sequence type ST131 Escherichia coli strain resulting in death, abstr. C1-123. Abstr. 48th Annu. Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. (ICAAC)-Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. (IDSA) 46th Annu. Meet.

- 8.Pitout, J. D., P. Nordmann, K. B. Laupland, and L. Poirel. 2005. Emergence of Enterobacteriaceae producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) in the community. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:52-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valverde, A., F. Grill, T. M. Coque, V. Pintado, F. Baquero, R. Cantón, and J. Cobo. 2008. High rate of intestinal colonization with extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing organisms in household contacts of infected community patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2796-2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vigil, K. J., J. R. Johnson, B. Johnston, D. Kontoyiannis, V. Mulanovich, J. Tarrand, R. Chemaly, R. Reitzel, I. Raad, H. L. Dupont, and J. A. Adachi. 2008. Escherichia coli (Ec) pyomyositis in hematology cancer patients: clinical manifestations, virulence factors and genomic analysis, abstr. K-1414. Abstr. 48th Annu. Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. (ICAAC)-Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. (IDSA) 46th Annu. Meet.