Abstract

The Vpu accessory gene that originated in the primate lentiviral lineage leading to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is an antagonist of human tetherin/BST-2 restriction. Most other primate lentivirus lineages, including the lineage represented by simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagm from African green monkeys (AGMs), do not encode Vpu. While some primate lineages encode gene products other than Vpu that overcome tetherin/BST-2, we find that SIVagm does not antagonize physiologically relevant levels of AGM tetherin/BST-2. AGM tetherin/BST-2 can be induced by low levels of type I interferon and can potently restrict two independent strains of SIVagm. Although SIVagm Nef had an effect at low levels of AGM tetherin/BST-2, simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmus Vpu, from a virus that infects the related monkey Cercopithecus cephus, is able to antagonize even at high levels of AGM tetherin/BST-2 restriction. We propose that since the replication of SIVagm does not induce interferon production in vivo, tetherin/BST-2 is not induced, and therefore, SIVagm does not need Vpu. This suggests that primate lentiviruses evolve tetherin antagonists such as Vpu or Nef only if they encounter tetherin during the typical course of natural infection.

Innate and intrinsic immunity plays a vital role as the first line of defense against viral infections. This antiviral response is enhanced by type I interferon (IFN), which can be produced by all nucleated cells in response to a viral infection (4) and activates the induction of genes including the antiviral factors TRIM5α, TRIMCyp, and BST-2/CD317/HM1.24 (7, 28). BST-2/CD317/HM1.24 was first identified as a marker for cells involved in B-cell differentiation and was subsequently found to be overexpressed on multiple myeloma cells (12, 16, 30). Upon the discovery of its antiviral activity, the name “tetherin” was coined to describe the tethering phenotype that BST-2/CD317/HM1.24 causes during virion budding from the plasma membrane (28). For simplicity, we will refer to the protein encoded by this gene only as tetherin for the remainder of the manuscript.

Tetherin is a host restriction factor capable of inhibiting the release of a broad range of viruses from the plasma membrane of infected cells. In addition to inhibiting the release of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) particles, tetherin also inhibits the release of filoviruses (Ebola and Marburg viruses), arenaviruses (Lassa virus), and other retroviruses including gammaretroviruses (murine leukemia virus) and spumaretroviruses (foamy virus) (13, 19, 28, 31). HeLa, Jurkat, and CEM cells constitutively express high levels of tetherin; however, in cells that express low levels of tetherin, such as 293T or HT1080 cells, tetherin can be upregulated by type I IFN (28). This results in permissive 293T cells becoming nonpermissive to infection by HIV type 1 (HIV-1) and Ebola virus (27).

Retroviruses have developed at least three strategies to counteract tetherin (22). First, the Vpu protein from HIV-1 abrogates the retention phenotype in cells that express tetherin and has been observed to be colocalized with tetherin (28, 34). Vpu displays species specificity and counteracts human tetherin by targeting it for degradation (11, 25, 28). Notably, Vpu is encoded by a unique lineage of primate lentiviruses, including HIV-1, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) SIVcpz from chimpanzees, and SIVmus, SIVgsn, and SIVmon from mustached monkeys (Cercopithecus cephus), greater spot-nosed monkeys (Cercopithecus nictitans), and Mona monkeys (Cercopithecus mona), respectively (8), but is not encoded by the other lineages of primate lentiviruses. Second, lentiviruses from the SIVsmm/SIVmac lineage have evolved the ability to counteract tetherin through the Nef protein (17, 39). The Nef proteins from SIVsmm and SIVmac display species specificity in their ability to counteract their hosts, sooty mangabey and rhesus macaque, respectively, and closely related tetherins. Third, the HIV-2 envelope enhances virion particle release and is able to complement HIV-1 that lacks Vpu (6). Ebola virus, a member of the family Filoviridae, has a means to counteract tetherin through its full-length glycoprotein (GP) (20). Overall, the independent acquisitions of a viral tetherin antagonist by multiple viruses emphasize the role of tetherin and the strong selective pressure imposed by its potent restriction.

SIVagm, a primate lentivirus, displays several key differences from pathogenic HIV-1. SIVagm isolates from African green monkeys (AGMs) cluster phylogenetically into four distinct clades, named SIVagmVer, SIVagmGri, SIVagmTan, and SIVagmSab, for their host species, vervet, grivet, tantalus, and sabaeus monkeys, respectively (2, 3, 18, 26, 37). These SIVagm viruses cause a nonpathogenic infection in their natural AGM hosts, in contrast to pathogenic HIV infections of humans (9). Both HIV-1 and SIVagm reach high levels of viral titers in vivo and replicate chronically in infected individuals. However, HIV-1 infection of humans usually results in chronic IFN stimulation (23), whereas there is an absence of chronic stimulation of IFN production in SIVagm infection in naturally infected AGMs despite equivalent high levels of virus titers (10).

Although human tetherin inhibits the release of SIVagm virus-like particles and HIV-1 virus-like particles, SIVagm does not encode Vpu (19). However, SIVmus, which can be found in naturally infected Cercopithecus cephus monkeys, a species closely related to AGMs, does encode a Vpu protein (35). The compelling evidence of an independent acquisition of antitetherin factors in multiple viruses, coupled with the presence of Vpu in a SIV from a closely related host species, led us to the hypothesis that SIVagm might also possess a non-Vpu tetherin counterdefense.

Here, we report that SIVagm is restricted by endogenous AGM tetherin. Surprisingly, AGM tetherin causes a virion retention phenotype against the wild types (WTs) from both tantalus monkeys and sabaeus monkeys. Furthermore, we show that endogenous AGM tetherin expression is induced by type I IFNs, resulting in virion retention phenotypes for WT SIVagm. While we did see an effect of SIVagm on low levels of tetherin, we find that this effect is minor compared to the effects of SIVmus Vpu to overcome AGM tetherin restriction. Thus, SIVagm has not acquired an antagonist of AGM tetherin that is as potent as the antagonists encoded by HIV-1 or SIVmac. We propose that since SIVagm infection occurs in the absence of chronic IFN production (10), SIVagm does not encounter tetherin during the course of infection and does not require Vpu or Nef activity to counteract tetherin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and plasmids.

293T, COS-7, and TZM-bl cells were maintained in a solution containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 8% bovine growth serum, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. TZM-bl cells were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. Chlorocebus sabaeus fibroblasts were obtained from the Coriell Institute and were maintained in a solution containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. SupT1 cells were maintained in a solution containing RPMI 1640 medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

The SIVagm molecular clones pSAB-1 (SIVagmSab) and pSIVagmTan-1 (SIVagmTan) were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. The SIVagmTan Env− Nef− provirus was a gift from Ned Landau (24). The HIV1VpuFS construct, containing a frameshift mutation in Vpu, is based on a molecular clone of HIV-1 described previously (15). The HIV1VpuFSLuc2 double mutant reporter clone was constructed by replacing the Nef gene of HIV1VpuFS with the Nef gene containing an insertion of the modified firefly luciferase, as described previously (38).

Codon-optimized HIV-1 Vpu was a gift from Stephen Bour (29), and codon-optimized (Genscript) SIVmus Vpu was constructed from a calculated ancestral sequence constructed from four SIVmus Vpu sequences reported previously (1, 29). Both Vpu constructs were inserted into a pCDNA3.1 expression vector as HindIII and NotI fragments. The empty pCDNA3.1 vector was used as a negative control. The Nef proteins from SIVagmTan and SIVagmSab were PCR amplified from pSIVagmTan-1 and pSAB-1, respectively, flanked by HindIII and XhoI restriction sites, and ligated into a pCDNA3.1 expression vector.

Human, Cercopithecus cephus, AGM, and chimpanzee tetherins were cloned from human cDNA, C. cephus genomic DNA (Coriell Cell Repository), cDNA from CV-1 cells, and chimpanzee cDNA, respectively. Tetherin was amplified by PCR, resulting in fragments with NgoMIV and NotI sites. A hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag was fused to the N terminus of tetherin and inserted into retroviral expression vector pLPCX. To construct untagged AGM tetherin, the HA epitope tag was removed by restriction digestion, overhangs were filled in with DNA polymerase I and large Klenow fragment (Invitrogen), and blunt-end ligation was performed with T4 DNA ligase (Roche). The empty pLPCX vector was used as a negative control.

Transfection and virus pseudotyping.

293T and COS-7 cells were seeded at 1.67 × 105 and 8.33 × 104 cells/ml, respectively. DNA was transfected with Fugene6 reagent (Mirius) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

To measure the tetherin restriction of HIV1VpuFS, 293T cells were transfected with HIV1VpuFS (100 ng), human tetherin (200 ng), cephus monkey tetherin (400 ng), AGM tetherin (400 ng), HIV-1 Vpu (125 ng), or SIVmus Vpu (100 ng). Transfections involving SIVagm provirus were performed with SIVagmTan (100 ng), SIVagmTan Env− Nef− (100 ng) with vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G) (50 ng), and SIVagmSab (100 ng). AGM titration was performed with 0, 3.12, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 ng of native (untagged) AGM tetherin, VSV-G (50 ng), and SIVagmTan (100 ng) or SIVagmTan Env− Nef− (100 ng). For experiments involving Nef, 293T cells were transfected with HIV1VpuFSLuc2 (100 ng), human tetherin (100 ng), chimpanzee tetherin (100 ng), AGM tetherin (100 ng), and SIVmus Vpu (100 ng), SIVagmTan Nef (250 ng), or SIVagmSab Nef (250 ng). In all experiments, the total amount of DNA was maintained constant by adding the respective amounts of empty vectors. Forty-eight hours after transfection, supernatant containing virus was filtered through a 0.22-μm filter and analyzed by a Western blot or infectivity assay. Cells were washed with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline and removed with 0.05% trypsin for Western blot analysis.

VSV-G-pseudotyped viruses for electron microscopy and Western blot experiments were prepared by the cotransfection of a VSV-G expression vector (pL-VSV-G) (50 ng) with SIVagmTan Env− Nef− (100 ng) or SIVagmTan (100 ng) in 293T cells, as described previously (24). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the supernatant containing pseudotyped viruses was pooled and filtered through a 0.22-μm filter. Virus was concentrated by ultracentrifugation, and titers were determined by infecting reporter TZM-bl cells with serial dilutions of virus stock as described previously (36).

Infectivity assay.

An infectivity assay was performed with TZM-bl cells as described previously (21). TZM-bl cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/ml in 96-well plates. Serial dilutions of virus supernatant were used to infect TZM-bl cells by spinoculation at 1,200 relative centrifugal force (RCF) for 2 h in the presence of 20 μg/ml DEAE-dextran. Forty-eight hours postinfection, 200 μg/ml of 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-galactopyranoside was added to cells, and the resulting fluorescence (lacZ activity) was measured using a spectrophotometer at 30-s intervals at 360 nm/460 nm. The relative infectivity was determined by the linear rate of increasing lacZ activity over time.

An HIV1VpuFSLuc2 infectivity assay was performed with SupT1 cells at 2.5 × 105 cells/ml in 96-well plates. Serial dilutions of virus supernatants were used to infect SupT1 cells by spinoculation at 1,200 RCF for 1 h in the presence of 20 μg/ml DEAE-dextran. Forty-eight hours postinfection, the level of luciferase expression was determined by use of the Bright-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting.

Forty-eight hours after transfection or infection, cells were analyzed by Western blotting as described previously (38), with the following modifications. Lysis was performed with NTE medium (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl) in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) for 5 min, followed by NP40-doc (1%NP-40, 0.2% sodium deoxycholate, 0.12 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris [pH 8.0]) for 10 min. Proteins were separated on a 4 to 12% NuPAGE Novex Bis-Tris precast gel (Invitrogen). The membrane was probed with the following primary antibodies: HA-specific antibody (HA.11 mouse immunoglobulin G; Babco) at a 1:1,000 dilution and anti-actin rabbit antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) at a 1:500 dilution. Primary antibodies were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies, respectively. SIVagm was detected with sera from rhesus macaques infected with SIVagmsab92018 (Cristian Apetrei, Tulane National Primate Research Center) and probed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-monkey immunoglobulin G secondary antibody (Cappel).

IFN studies.

Recombinant human IFN-α2A and IFN-β1b were obtained from PBL Biomedical Laboratories (catalog numbers 11100-1 and 11420-1). Cells were exposed to 0, 100, or 1,000 units/ml IFN for 24 or 48 h and analyzed for tetherin RNA expression by semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) or fixed for thin-section electron microscopy, respectively. For the analysis of endogenous tetherin effects, COS-7 cells were infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped SIVagmTan or VSV-G-pseudotyped SIVagmTan Env− Nef− by spinoculation at 1,200 RCF for 2 h in the presence of 20 μg/ml DEAE-dextran. IFN-β1b was added 6 h later, followed by an additional 42 h of incubation before fixing for thin-section electron microscopy or analysis by Western blotting as described above.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR.

Cells were removed by use of 0.05% trypsin-EDTA, and RNA was extracted by use of an RNeasy minikit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Human tetherin, AGM tetherin, and β-actin were reverse transcribed with a OneStep RT-PCR kit (Qiagen) for 30 min at 50°C, followed by inactivation at 95°C for 15 min. Four microliters of cDNA was amplified by PCR with Taq DNA polymerase (Roche), and amplified products were separated on a 1.25% agarose gel. AGM and human β-actin were amplified with the following set of primers: TGACATTAAGGAGAAGCTGTGCTA and ACTCGTCATACTCCTGCTTGCT. AGM tetherin spanning exon 2 to exon 4 was amplified with the following set of primers: CAAGGACGAAAGAAAGTGGAG and AAGCCCAGCAGCAGAATCAG. Human tetherin spanning exon 1 to exon 4 was amplified with the following set of primers: ATCTCCTGCAACAAGAGCTGAC and GTACTTCTTGTCCGCGATTCTC.

Thin-section electron microscopy.

Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde-2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer and removed with a cell scraper. All washes were performed with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer. As a postfixative, 1% OsO4 was added, followed by 4% aqueous uranyl acetate. Cells were dehydrated in a series of ethanol gradients (50 to 100%), embedded in Epon 812 resin, and cured for 48 h at 60°C. Thin sections (70 to 100 nm) of the samples were obtained and stained with uranyl acetate, followed by lead citrate. Electron micrographs were taken using a Jeol 1230 transmission electron microscope with an Ultrascan 1000 camera.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence for C. cephus tetherin has been deposited in GenBank (accession no. GQ864267).

RESULTS

HIV-1 Vpu and SIVmus Vpu overcome restriction from tetherins from the host and related species.

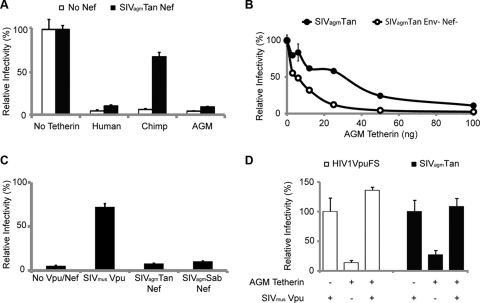

Cercopithecus cephus (also called mustached monkey), AGM, and human tetherins were tested for antiviral activity. We were interested in tetherin from C. cephus because C. cephus monkeys are related to AGMs and because SIVmus that infects C. cephus encodes a Vpu protein, unlike SIVagm (8, 33). We cloned the gene that encodes tetherin from C. cephus and from Chlorocebus tantalus (AGM) into a retroviral vector expressing an N-terminal HA epitope tag. Since HIV-1 Vpu is known to counteract human tetherin, we tested the ability of these tetherins to restrict HIV-1 expressing a frameshift mutation in Vpu (HIV1VpuFS) (28). We also complemented these transfections with either HIV-1 Vpu or SIVmus Vpu expression vectors in trans. For this, plasmids encoding HIV1VpuFS, tetherin, and/or Vpu were transiently cotransfected into 293T cells (which express low levels of endogenous tetherin [28]), and the activity of tetherin or Vpu was measured by the infectivity of released virus on indicator cells (see Materials and Methods).

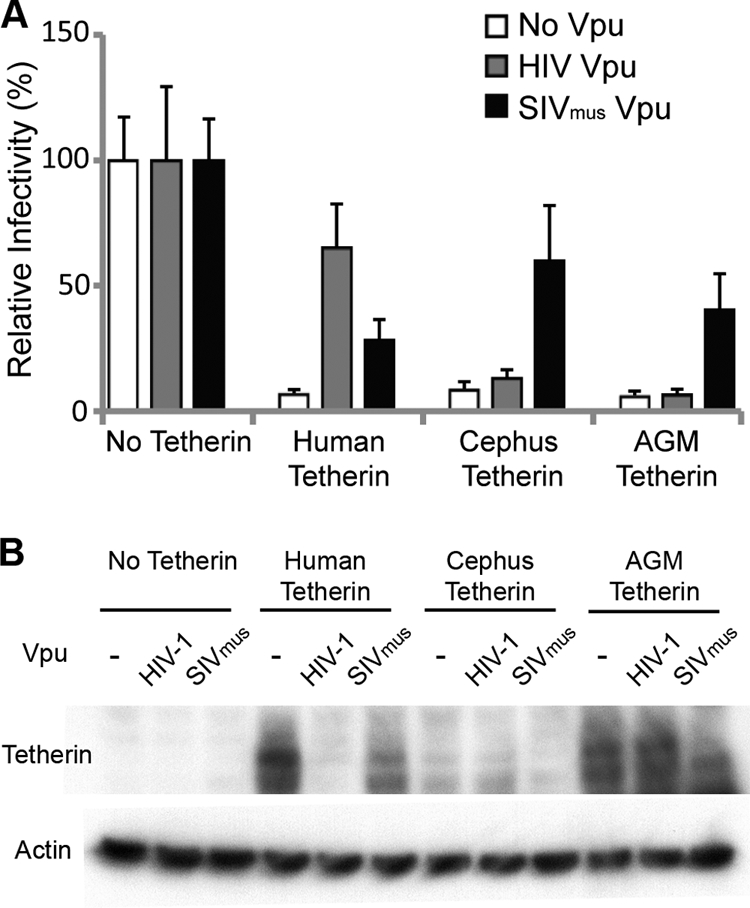

We found that human, cephus monkey, and AGM tetherin all restricted the release of infectious HIV-1 virions by equal amounts in the absence of Vpu (Fig. 1A). HIV-1 Vpu was able to overcome human tetherin restriction but was unable to overcome restriction by C. cephus or AGM tetherin (Fig. 1A). Conversely, SIVmus Vpu was able to overcome restriction by C. cephus and AGM tetherins but had only a mild effect on human tetherin (Fig. 1A). This indicates that while tetherins from all three species are functional, the Vpu proteins of HIV-1 and SIVmus display a species-specific antagonism of tetherin, which corroborates previous findings (11). Furthermore, we found that HIV-1 Vpu resulted in decreased levels of expression of human tetherin but had a minimal effect on C. cephus and AGM tetherin levels (Fig. 1B). Conversely, SIVmus Vpu decreased the levels of C. cephus and AGM tetherins but had little effect on human tetherin (Fig. 1B). This result indicates that the mechanism of SIVmus Vpu activity is likely similar to that of HIV-1 Vpu, likely through the degradation of tetherin (11).

FIG. 1.

AGM and cephus tetherins restrict HIV1VpuFS and are counteracted by SIVmus Vpu. (A) 293T cells were cotransfected with HIV1VpuFS (100 ng), human (200 ng), C. cephus (Cephus) (400 ng), or AGM tetherin (400 ng); HIV-1 Vpu (125 ng); and SIVmus Vpu (100 ng) for 48 h. The respective empty vectors were used, indicated by no tetherin or no Vpu. Equal amounts of virus-containing supernatant were used to infect TZM-bl reporter cells for 48 h. Relative infectivity was determined by the rate of β-galactosidase activity. Bars represent the average data for eight infections, normalized to the relative infectivity of the respective Vpu proteins in the absence of tetherin. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) 293T cell lysates (A) were collected 48 h after transfection and analyzed by Western blot analysis for HA-tagged tetherin and β-actin expression levels.

SIVagmTan and SIVagmSab are restricted by AGM tetherin and do not encode a tetherin counterdefense.

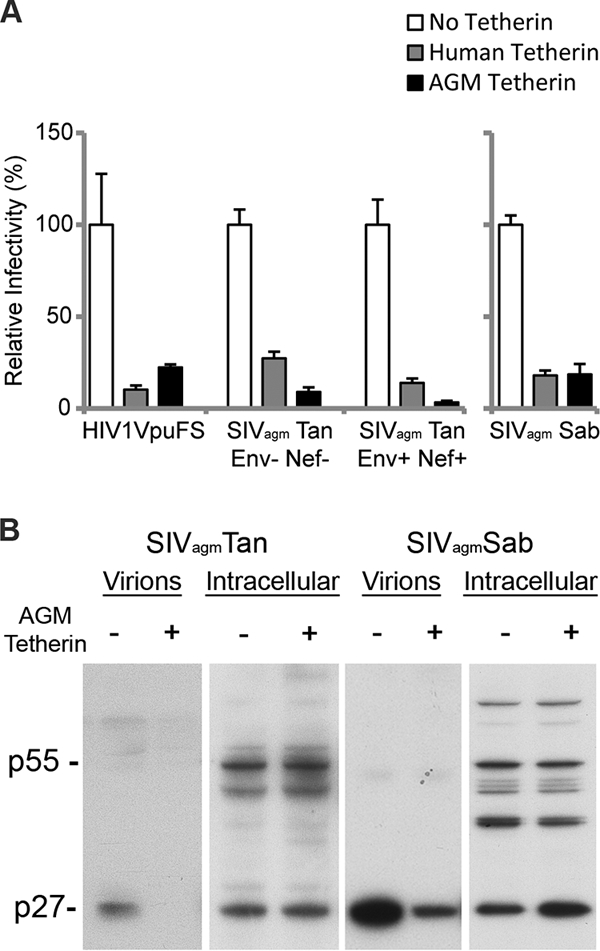

Since AGM tetherin is able to restrict HIV-1 (Fig. 1), we determined whether AGM tetherin could restrict SIVagm. HIV-2, which does not encode a Vpu protein, has Vpu-like activity in its viral envelope (6). Although SIVagm does not encode Vpu, we suspected that the SIVagm envelope protein (Env) or Nef might encode a Vpu-like activity, as seen in HIV-2 and SIVmac/SIVsmm, respectively (6, 17). To test this, we compared the infectivity of SIVagmTan to that of a construct containing a deletion in Env and Nef (SIVagmTan Env− Nef−) in the presence of AGM tetherin. SIVagmTan Env− Nef− was pseudotyped by cotransfection with VSV-G to produce infectious virus. Viral constructs and tetherin were cotransfected in 293T cells, and viral production was analyzed in an infectivity assay. As described above, we found that HIV1VpuFS was restricted by both human and AGM tetherins. Surprisingly, we also found that SIVagmTan and SIVagmTan Env− Nef− were restricted by both human and AGM tetherins (Fig. 2A, left). This means that unlike HIV-2, SIVagmTan Env does not contain a Vpu-like activity, nor is this activity encoded by the Nef gene. Although both SIVagmTan constructs have a premature stop codon in the Vpr coding region, there was no effect on tetherin restriction when virions were complemented with Vpr from SIVagm or HIV-1 (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

SIVagm does not encode Vpu-like activity. (A) 293T cells were cotransfected with HIV1VpuFS, SIVagmTan Env− Nef− (and VSV-G for pseudotyping), SIVagmTan Env+ Nef+ (left), or SIVagmSab (right) and no tetherin (empty vector) or human or AGM tetherin for 48 h. Virus was used to infect TZM-bl reporter cells for 48 h to determine the relative infectivity. (B) 293T cells were transfected with SIVagmTan (left) or SIVagmSab (right) with or without AGM tetherin. Virions from the supernatant were collected and pelleted, while cells were lysed to yield intracellular virions. Western blot analysis was performed to compare the amounts of cell-free virions.

To verify these findings, we also tested the full-length molecular infectious clone of SIVagmSab against human and AGM tetherins. SIVagmSab is closely related to SIVagmTan and is the most basal taxon of the SIVagm lineage (18, 37). Like SIVagmTan, SIVagmSab does not encode a Vpu protein (18, 26, 37), and all of the accessory genes of the SIVagmSab clone are intact. We also independently cloned the tetherin gene from primary fibroblasts of Chlorocebus sabaeus and found it to be identical to the AGM tetherin that we used previously (data not shown). Strikingly, similar to the findings with SIVagmTan, we also found that a full-length SIVagmSab clone was restricted by both human and AGM tetherins to the same extent as HIV1VpuFS (Fig. 2A, right). We also compared the levels of production of cell-free SIVagm virions in the presence of sabaeus monkey tetherin. 293T cells were transfected with SIVagmTan or SIVagmSab in the presence or absence of AGM tetherin. Supernatant fractions containing cell-free virions were filtered and probed with sera obtained from rhesus macaques infected with SIVagmsab92018 (provided by Cristian Apetrei, Tulane National Primate Research Center). There was less cell-free SIVagmTan and SIVagmSab p27 capsid detected in the presence of AGM tetherin (Fig. 2B). In contrast, intracellular levels of p55 and p27 were similar regardless of the level of expression of AGM tetherin. Thus, WT SIVagmSab virions are prevented from release in the presence of AGM tetherin. These results indicate that in at least two SIVagm lineages, viral isolates do not encode a viral antagonist against its host tetherin.

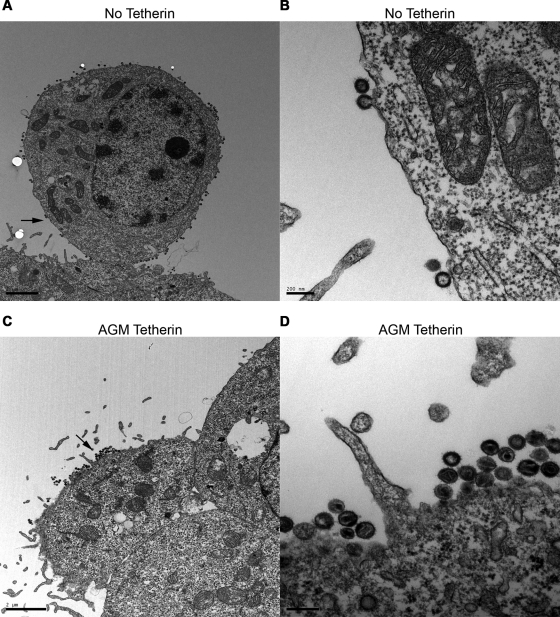

We also examined the fate of SIVagm virions produced in the presence of AGM tetherin by electron microscopy. Human 293T cells were cotransfected with SIVagmSab and AGM tetherins for 48 h and subsequently visualized by thin-section electron microscopy. In the absence of AGM tetherin, SIVagmSab virions were observed to bud from the plasma membrane in a single layer (Fig. 3A and B). In the presence of AGM tetherin, we observed that SIVagmSab virions budding from the plasma membrane were markedly tethered together and extended outward in a layered arrangement (Fig. 3C and D). Notably, most of the tethered virions were mature, as indicated by the condensed capsid. This indicates that AGM tetherin restricts WT SIVagm virion release by tethering mature virions to the plasma membrane (similar to the effect of human tetherin on Vpu mutant HIV-1 [28]).

FIG. 3.

AGM tetherin retains SIVagmSab on the plasma membrane. Shown is thin-section electron microscopy of 293T cells transfected for 48 h with SIVagmSab in the absence of AGM tetherin (A and B) or in the presence of AGM tetherin (C and D). (A) SIVagmSab budding from the plasma membrane in a single layer in the absence of tetherin. The arrow indicates the location of the magnified image. (B) Magnified image from A. (C) Accumulation of budding SIVagmSab cells on the plasma membrane in the presence of AGM tetherin. Note that mature virions form multiple layers. The arrow indicates the location of the magnified image. (D) Magnified image of C. Scale bars, 2 μm (A and C) and 200 nm (B and D).

Since the SIVmac/SIVsmm lineage has evolved Nef to counteract its host and closely related tetherins (17, 39), we directly tested if SIVagmTan Nef had the ability to counteract tetherins from other species. We cloned the Nef gene from SIVagmTan into an expression vector and verified its activity by showing that it could downregulate CD4 levels (data not shown), which is consistent with previously reported findings (32). SIVagmTan Nef was then cotransfected in 293T cells with SIVagmTan Nef; human, chimpanzee, or AGM tetherin; and an HIV-1 construct that had a luciferase gene inserted into the Nef open reading frame and expressed a frameshift mutation in Vpu. The ability of Nef to counteract tetherin was assayed by the infectivity of released virus on SupT1 cells (see Materials and Methods). Consistent with the findings shown in Fig. 2, SIVagmTan Nef did not overcome AGM tetherin restriction (Fig. 4A). SIVagmTan Nef also did not counteract human tetherin restriction; however, chimpanzee tetherin was antagonized by SIVagmTan Nef. Thus, SIVagmTan Nef has the ability to antagonize other species' tetherin but not its host tetherin.

FIG. 4.

AGM tetherin is not antagonized by SIVagm Nef but retains interface with SIVmus Vpu. (A) 293T cells were cotransfected with HIV1VpuFSLuc2 (100 ng), SIVagmTan Nef (250 ng), and human (100 ng), chimpanzee (100 ng), or AGM (100 ng) tetherin. Virus was assayed on SupT1 cells, and relative infectivity was normalized in the absence of tetherin. Bars represent average data for four infections, and error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) 293T cells were cotransfected with VSV-G and SIVagmTan (solid circles) or SIVagmTan Env− Nef− (open circles) with increasing amounts of untagged AGM tetherin (0, 3.12, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 ng). Virus infectivity was assayed on TZM-bl reporter cells, and relative infectivity was normalized in the absence of tetherin. Points represent average data for four infections, and error bars represent standard deviations. (C) 293T cells were cotransfected with HIV1VpuFSLuc2 (100 ng), AGM tetherin (100 ng), SIVmus Vpu (100 ng), SIVagmTan Nef (250 ng), or SIVagmSab Nef (250 ng). Virus was assayed on SupT1 cells, and relative infectivity was normalized in the absence of tetherin. Bars represent average data for four infections, and error bars indicate standard deviations. (D) 293T cells were cotransfected with HIV1VpuFS or SIVagmTan, AGM tetherin, and SIVmus Vpu where indicated for 48 h. Virus was added to TZM.b1 reporter cells for 48 h, and relative infectivity was determined as described in the legend of Fig. 1A, normalized to the respective virus in the absence of tetherin. Bars represent average data for eight readings, and error bars indicate standard deviations.

To verify that the N-terminal HA epitope tag did not interfere with tetherin interactions with viral proteins, we performed a titration of native (untagged) AGM tetherin against WT SIVagmTan and SIVagmTan Env− Nef−. Both viruses were pseudotyped with VSV-G, and the relative infectivity was normalized in the absence of tetherin. There was a difference between WT SIVagmTan (Fig. 4B) and the mutant virus lacking Env and Nef (Fig. 4B) at low levels of AGM tetherin; however, a dramatic restriction was observed at higher levels of tetherin. Importantly, both viruses displayed dose-dependent restriction by AGM tetherin, even at the low levels of tetherin expression (Fig. 4B). Since we saw an effect of WT SIVagm on tetherin only at low levels of tetherin expression, we then directly compared the effects of SIVagmSab Nef, SIVagmTan Nef, and SIVmus Vpu for the ability to counteract AGM tetherin restriction by using the HIV-1 reporter virus lacking Vpu and Nef. Indeed, we found that SIVmus Vpu was able to effectively antagonize AGM tetherin when 100 ng of SIVagm tetherin plasmid was transfected, but the Nef proteins from SIVagmTan and SIVagmSab did not counteract AGM tetherin (Fig. 4C). Thus, even if SIVagm Nef genes encode activity against AGM tetherin, the effects are minor compared to those of SIVmus Vpu.

We also complemented HIV1VpuFS and SIVagmTan with SIVmus Vpu. We found that in the presence of SIVmus Vpu, HIV1VpuFS counteracted AGM tetherin restriction. Similarly, SIVagmTan was rescued by SIVmus Vpu to overcome AGM tetherin restriction (Fig. 4D). Thus, AGM tetherin retains the ability to be counteracted by SIVmus Vpu, yet the SIVagm lineage does not appear to take advantage of this susceptibility to antagonize tetherin.

Type I IFNs induce AGM tetherin.

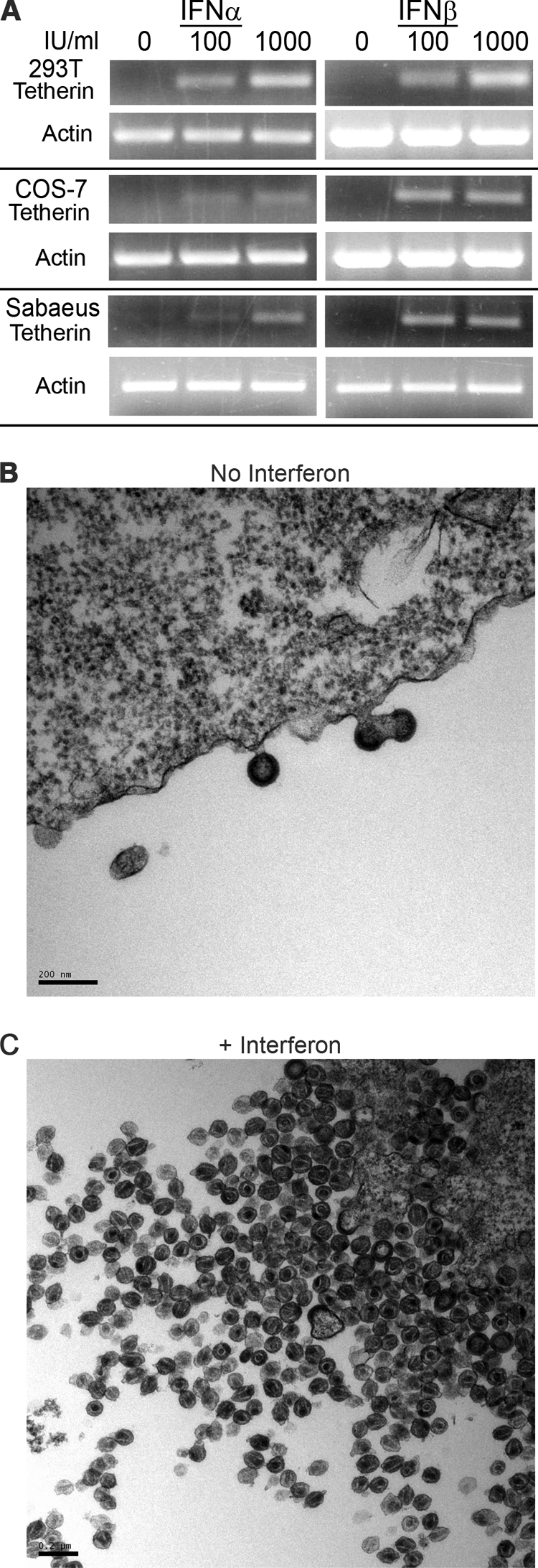

Human tetherin expression is induced by type I IFN (28, 34). Thus, we considered the possibility that SIVagm has not evolved to inhibit tetherin because tetherin is not induced by IFN in AGM cells. We determined whether endogenous AGM tetherin is induced by IFN and if it is functional and active against SIVagm. Two AGM cell lines, COS-7 (C. tantalus) and sabaeus primary fibroblasts (C. sabaeus), and human 293T cells were incubated with increasing amounts of type I IFNs: IFN-α2a or -β1b (0, 100, and 1,000 IU/ml). Tetherin mRNA expression was measured by RT-PCR of equal amounts of RNA. To ensure that we amplified mRNA and not genomic DNA, primer sets specific to human and AGM tetherins were designed to flank introns. As a control, we measured the expression of β-actin, which is not affected by type I IFNs. Twenty-four hours after exposure to IFN-α2a or -β1b, human tetherin mRNA levels were upregulated in 293T cells (Fig. 5A, top). Similarly, in both species of AGM cells, AGM tetherin mRNA levels increased 24 h after exposure to IFN-α2a or -β1b (Fig. 5A, middle and bottom). We conclude that type I IFNs induce AGM tetherin mRNA expression in AGM cells.

FIG. 5.

Type I IFNs induce AGM tetherin and the tetherin virion retention phenotype. (A) 293T (human), COS-7 (AGM), and C. sabaeus primary fibroblast (AGM) cells were incubated with 0, 100, or 1,000 IU/ml IFN-α2a or IFN-β1b for 24 h. Cells were harvested and lysed for RT-PCR analysis. (B and C) Thin-section electron microscopy of accumulated SIVagmTan budding from COS-7 cells exposed to no IFN (B) or 1,000 IU/ml IFN-β1b (C). COS-7 cells were infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped SIVagmTan. Six hours after infection, cells were exposed to 1,000 IU/ml IFN-β1b and fixed for thin-section electron microscopy after an additional 42 h. Scale bars, 0.2 nm.

Next, we determined if type I IFN induces a tetherin-associated virion retention phenotype in AGM cells. SIVagmTan (pseudotyped with VSV-G) was used to infect AGM COS-7 cells, and 6 h after infection, cells were exposed to 1,000 IU/ml IFN-β1b for a further 42 h before being fixed for thin-section electron microscopy. Upon exposure to IFN-β1b, we observed a marked retention of matured SIVagm virions on the plasma membrane of infected AGM cells (Fig. 5C), similar to the retention phenotype seen when AGM tetherin was expressed exogenously (Fig. 3C and D). In comparison, virion budding in the absence of type I IFN (Fig. 5B) was similar to the phenotype observed in the absence of AGM tetherin (Fig. 3A and B). Thus, type I IFN induces a tetherin-associated retention phenotype in AGM cells, which SIVagm is unable to overcome. Although experiments here were not performed using primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells from AGMs, these findings are consistent for primary fibroblasts from AGMs and thus not a result of subspecies specificity or transformed cells.

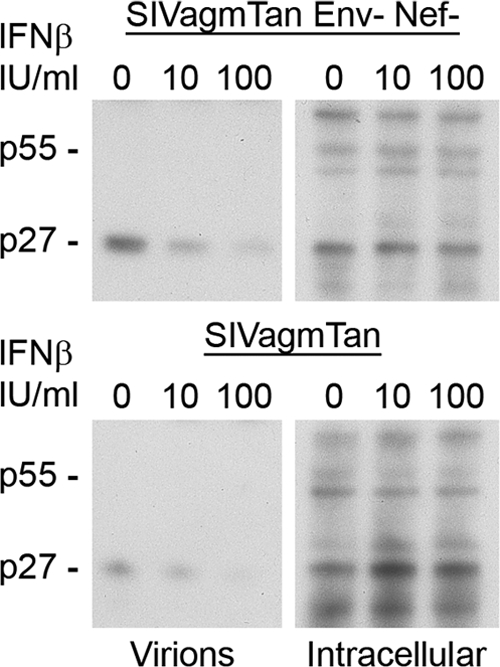

Finally, we verified the restriction of cell-free virus release by endogenous AGM tetherin at lower doses of IFN. The amount of IFN seen in SIVagm-infected AGMs is about 100 to 1,000 IU/ml, peaking at 2,500 IU/ml (10). Therefore, COS-7 cells were infected with equivalent amounts of VSV-G-pseudotyped SIVagmTan or SIVagmTan Env− Nef−, and at 6 h postinfection, cells were exposed to increasing amounts of IFN-β1b (0, 10, and 100 IU/ml). Cell-free virions were compared to cell-associated virions by Western blot analysis. Cell-free SIVagmTan and SIVagmTan Env− Nef− displayed a dose-response decrease upon the addition of 10 and 100 IU/ml IFN regardless of the presence or absence of Env and Nef (Fig. 6). Importantly, there was a major effect on viral release at 100 IU/ml. Thus, relatively low levels of IFN are able to induce the tetherin-associated cell-free virus restriction phenotype.

FIG. 6.

Type I IFNs induce AGM tetherin restriction of virus release. COS-7 (AGM) cells were infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped SIVagmTan Env− Nef− (top) or VSV-G-pseudotyped SIVagmTan (bottom) and exposed to 0, 10, or 100 IU/ml IFN-β1b 6 h postinfection. Virions from the supernatant were collected and pelleted, while cells were lysed to yield intracellular virions. Western blot analysis was performed to compare the amounts of cell-free virions.

DISCUSSION

Many primate lentiviruses encode a viral antagonist against tetherin, such as Vpu in HIV-1, Env in HIV-2, or Nef in SIVmac/SIVsmm. In contrast, we show here that SIVagm does not encode a major viral antagonist against its AGM host tetherin despite AGM tetherin being functionally active, able to be inhibited by Vpu from SIVmus, and induced by type I IFN. Since tetherin is an IFN-regulated gene (even in AGM cells), we propose that SIVagm has evolved to replicate without inducing an IFN response, thus obviating its need for a virally encoded activity to counteract the antiviral effects of tetherin.

Primates naturally infected with their own species of lentiviruses can have a nonpathogenic outcome. In AGMs and other primates naturally infected with SIV, such as sooty mangabeys (SIVsmm), viral replication can reach high titers in the blood (10, 14, 23). However, these primates do not develop AIDS-like symptoms and often have nonpathogenic outcomes. A hallmark of these nonpathogenic SIV infections is the lack of chronic immune activation. In SIVagm-infected AGMs, IFN-α levels in plasma peak 8 days postinfection and quickly recede to undetectable levels by 35 days postinfection (10). The transient immune response correlates with the peak and decrease in plasma viral loads, after which the viral load stabilizes at a set level. The decrease in plasma viral loads observed after the production of type I FIN is consistent with evidence that antiviral factors such as tetherin are induced. Needless to say, the effects of other concurrent cellular responses, such as cytotoxic T lymphocytes, on the decrease in viral titer cannot be discounted.

While the manuscript was under review, Zhang et al. showed that SIVagm Nef had an effect against AGM tetherin (39). We observed that at low levels of AGM tetherin, WT SIVagmTan was more infectious than SIVagmTan Env− Nef− (Fig. 4B). However, the effect of SIVagm Nef is minor compared to that of SIVmus Vpu (Fig. 4C). For example, SIVmus Vpu counteracts even high levels of tetherin, whereas SIVagm Nef and/or Env had only a two- to threefold effect at low levels of AGM tetherin. When we looked at endogenous levels of AGM tetherin induced by IFN, we observed a restriction of WT SIVagmTan even at low levels of IFN (Fig. 5C and 6). Since SIVagmTan Nef can counteract chimpanzee tetherin, SIVagmTan Nef has the ability to antagonize other species' tetherins but not its host tetherin (Fig. 4A). Sequence differences between chimpanzee tetherin and AGM tetherin point to an evolution of AGM tetherin that has resulted in the inability of SIVagmTan Nef to recognize target sequences within AGM tetherin. Therefore, although SIVagm Nef has an effect at low levels of AGM tetherin, we believe that the activity is insufficient to overcome endogenous levels during the course of acute infection.

There are two models of IFN modulation during viral infections. First, viruses can be capable of actively inhibiting the production of type I IFN. An example is the Ebola virus IFN antagonist VP35. VP35 inhibits the transcriptional activation of the IFN regulatory factor 3 promoter, essentially blocking the host from initiating an IFN response (5). Second, hosts can evolve to decrease their immune response to specific viral agonists, such as the polymorphisms of IFN regulatory factor 7 in sooty mangabeys, which result in attenuated type I IFN production when SIVsmm engages Toll-like receptor 7 or Toll-like receptor 9 (23). To date, there is no evidence that the lack of chronic IFN production during SIVagm infection of AGMs is due to either a virally directed or host-adapted response. Nonetheless, given that the stealth replication of SIVagm does not induce chronic immune activation, we expect that tetherin would not be constantly induced. Thus, SIVagm would not need Vpu activity to counteract tetherin. Collectively, retroviruses that do not encounter tetherin during their replication lack the selective pressure to maintain “Vpu” activity.

These guidelines allow us to predict whether viruses encode a viral antagonist of tetherin. SIVmac-infected rhesus macaques and HIV-1-infected humans often display AIDS-like symptoms. These hosts maintain chronically elevated IFN production levels throughout infection (23). As a result, overt viral replication occurs in an environment of chronic tetherin induction. This creates a need for these lentiviruses to acquire and maintain the ability to counteract tetherin restriction, as depicted by Vpu of HIV-1. In the same manner, SIVmac/SIVsmm has adapted Nef to act as a viral counterdefense against tetherin (17, 39). In conclusion, lentiviral replication in an environment of chronic innate immune responses may distinguish pathogenic from nonpathogenic infections (23), and this may subsequently play an important role in determining the viral factors that arose evolutionarily to counteract factors such as tetherin that are induced by such responses.

Acknowledgments

The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: TZM-bl from John C. Kappes, Xiaoyun Wu, and Tranzyme Inc.; pSAB-1 (SIVagmSab) from Mojun Jin and Beatrice Hahn; and pSIVagmTan-1 (SIVagmTan) from Marcelo Soares and Beatrice Hahn. We thank Harmit Malik for the tetherin constructs and reconstructing the ancestral SIVmus Vpu sequence, Christian Apetrei for the SIVagm antibodies, Ned Landau for SIVagmTan Env− Nef−, Stephan Bour for HIV-1 Vpu, the FHCRC Genomics and Scientific Imaging Shared Resources, and Harmit Malik, Masahiro Yamashita, Semih Tareen, and Nisha Duggal for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by NIH grant R37 AI30937.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 September 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aghokeng, A. F., E. Bailes, S. Loul, V. Courgnaud, E. Mpoudi-Ngolle, P. M. Sharp, E. Delaporte, and M. Peeters. 2007. Full-length sequence analysis of SIVmus in wild populations of mustached monkeys (Cercopithecus cephus) from Cameroon provides evidence for two co-circulating SIVmus lineages. Virology 360:407-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allan, J. S., P. Kanda, R. C. Kennedy, E. K. Cobb, M. Anthony, and J. W. Eichberg. 1990. Isolation and characterization of simian immunodeficiency viruses from two subspecies of African green monkeys. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 6:275-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allan, J. S., M. Short, M. E. Taylor, S. Su, V. M. Hirsch, P. R. Johnson, G. M. Shaw, and B. H. Hahn. 1991. Species-specific diversity among simian immunodeficiency viruses from African green monkeys. J. Virol. 65:2816-2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alsharifi, M., A. Müllbacher, and M. Regner. Interferon type I responses in primary and secondary infections. Immunol. Cell Biol. 86:239-245. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Basler, C. F., X. Wang, E. Mühlberger, V. Volchkov, J. Paragas, H. D. Klenk, A. García-Sastre, and P. Palese. 2000. The Ebola virus VP35 protein functions as a type I IFN antagonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:12289-12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bour, S., and K. Strebel. 1996. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 2 envelope protein is a functional complement to HIV type 1 Vpu that enhances particle release of heterologous retroviruses. J. Virol. 70:8285-8300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carthagena, L., M. C. Parise, M. Ringeard, M. K. Chelbi-Alix, U. Hazan, and S. Nisole. 2008. Implication of TRIM alpha and TRIMCyp in interferon-induced anti-retroviral restriction activities. Retrovirology 5:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Courgnaud, V., B. Abela, X. Pourrut, E. Mpoudi-Ngole, S. Loul, E. Delaporte, and M. Peeters. 2003. Identification of a new simian immunodeficiency virus lineage with a vpu gene present among different Cercopithecus monkeys (C. mona, C. cephus, and C. nictitans) from Cameroon. J. Virol. 77:12523-12534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diop, O. M., A. Gueye, M. Dias-Tavares, C. Kornfeld, A. Faye, P. Ave, M. Huerre, S. Corbet, F. Barre-Sinoussi, and M. Müller-Trutwin. 2000. High levels of viral replication during primary simian immunodeficiency virus SIVagm infection are rapidly and strongly controlled in African green monkeys. J. Virol. 74:7538-7547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diop, O. M., M. J.-Y. Ploquin, L. Mortara, A. Faye, B. Jacquelin, D. Kunkel, P. Lebon, C. Butor, A. Hosmalin, F. Barré-Sinoussi, and M. C. Müller-Trutwin. 2008. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell dynamics and alpha interferon production during simian immunodeficiency virus infection with a nonpathogenic outcome. J. Virol. 82:5145-5152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goffinet, C., I. Allespach, S. Homann, H. Tervo, A. Habermann, D. Rupp, L. Oberbremer, C. Kern, N. Tibroni, S. Welsch, J. Krijnse-Locker, G. Banting, H. Kräusslich, O. Fackler, and O. Keppler. 2009. HIV-1 antagonism of CD317 is species specific and involves Vpu-mediated proteasomal degradation of the restriction factor. Cell Host Microbe 5:285-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goto, T., S. Kennel, M. Abe, M. Takishita, M. Kosaka, A. Solomon, and S. Saito. 1994. A novel membrane antigen selectively expressed on terminally differentiated human B cells. Blood 84:1922-1930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Göttlinger, H., T. Dorfman, E. Cohen, and W. Haseltine. 1993. Vpu protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enhances the release of capsids produced by gag gene constructs of widely divergent retroviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:7381-7385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gueye, A., O. Diop, M. Ploquin, C. Kornfeld, A. Faye, M. Cumont, B. Hurtrel, F. Barré-Sinoussi, and M. Müller-Trutwin. 2004. Viral load in tissues during the early and chronic phase of non-pathogenic SIVagm infection. J. Med. Primatol. 33:83-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gummuluru, S., C. Kinsey, and M. Emerman. 2000. An in vitro rapid-turnover assay for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication selects for cell-to-cell spread of virus. J. Virol. 74:10882-10891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa, J., T. Kaisho, H. Tomizawa, B. Lee, Y. Kobune, J. Inazawa, K. Oritani, M. Itoh, T. Ochi, and K. Ishihara. 1995. Molecular cloning and chromosomal mapping of a bone marrow stromal cell surface gene, BST2, that may be involved in pre-B-cell growth. Genomics 26:527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia, B., R. Serra-Moreno, W. Neidermyer, A. Rahmberg, J. Mackey, I. Fofana, W. Johnson, S. Westmoreland, and D. Evans. 2009. Species-specific activity of SIV Nef and HIV-1 Vpu in overcoming restriction by tetherin/BST2. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin, M., H. Hui, D. Robertson, M. Müller, F. Barré-Sinoussi, V. Hirsch, J. Allan, G. Shaw, P. Sharp, and B. Hahn. 1994. Mosaic genome structure of simian immunodeficiency virus from west African green monkeys. EMBO J. 13:2935-2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jouvenet, N., S. Neil, M. Zhadina, T. Zang, Z. Kratovac, Y. Lee, M. McNatt, T. Hatziioannou, and P. Bieniasz. 2009. Broad-spectrum inhibition of retroviral and filoviral particle release by tetherin. J. Virol. 83:1837-1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaletsky, R., J. Francica, C. Agrawal-Gamse, and P. Bates. 2009. Tetherin-mediated restriction of filovirus budding is antagonized by the Ebola glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106:2886-2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimpton, J., and M. Emerman. 1992. Detection of replication-competent and pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus with a sensitive cell line on the basis of activation of an integrated beta-galactosidase gene. J. Virol. 66:2232-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malim, M., and M. Emerman. 2008. HIV-1 accessory proteins—ensuring viral survival in a hostile environment. Cell Host Microbe 3:388-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandl, J., A. Barry, T. Vanderford, N. Kozyr, R. Chavan, S. Klucking, F. Barrat, R. Coffman, S. Staprans, and M. Feinberg. 2008. Divergent TLR7 and TLR9 signaling and type I interferon production distinguish pathogenic and nonpathogenic AIDS virus infections. Nat. Med. 14:1077-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mariani, R., D. Chen, B. Schröfelbauer, F. Navarro, R. König, B. Bollman, C. Münk, H. Nymark-McMahon, and N. Landau. 2003. Species-specific exclusion of APOBEC3G from HIV-1 virions by Vif. Cell 114:21-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNatt, M., T. Zang, T. Hatziioannou, M. Bartlett, I. Fofana, W. Johnson, S. Neil, and P. Bieniasz. 2009. Species-specific activity of HIV-1 Vpu and positive selection of tetherin transmembrane domain variants. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller, M., N. Saksena, E. Nerrienet, C. Chappey, V. Hervé, J. Durand, P. Legal-Campodonico, M. Lang, J. Digoutte, and A. Georges. 1993. Simian immunodeficiency viruses from central and western Africa: evidence for a new species-specific lentivirus in tantalus monkeys. J. Virol. 67:1227-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neil, S., V. Sandrin, W. Sundquist, and P. Bieniasz. 2007. An interferon-alpha-induced tethering mechanism inhibits HIV-1 and Ebola virus particle release but is counteracted by the HIV-1 Vpu protein. Cell Host Microbe 2:193-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neil, S., T. Zang, and P. Bieniasz. 2008. Tetherin inhibits retrovirus release and is antagonized by HIV-1 Vpu. Nature 451:425-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen, K., M. llano, H. Akari, E. Miyagi, E. Poeschla, K. Strebel, and S. Bour. 2004. Codon optimization of the HIV-1 vpu and vif genes stabilizes their mRNA and allows for highly efficient Rev-independent expression. Virology 319:163-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozaki, S., M. Kosaka, S. Wakatsuki, M. Abe, Y. Koishihara, and T. Matsumoto. 1997. Immunotherapy of multiple myeloma with a monoclonal antibody directed against a plasma cell-specific antigen, HM1.24. Blood 90:3179-3186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakuma, T., T. Noda, S. Urata, Y. Kawaoka, and J. Yasuda. 2009. Inhibition of Lassa and Marburg virus production by tetherin. J. Virol. 83:2382-2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schindler, M., J. Münch, O. Kutsch, H. Li, M. Santiago, F. Bibollet-Ruche, M. Müller-Trutwin, F. Novembre, M. Peeters, V. Courgnaud, E. Bailes, P. Roques, D. Sodora, G. Silvestri, P. Sharp, B. Hahn, and F. Kirchhoff. 2006. Nef-mediated suppression of T cell activation was lost in a lentiviral lineage that gave rise to HIV-1. Cell 125:1055-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tosi, A., D. Melnick, and T. Disotell. 2004. Sex chromosome phylogenetics indicate a single transition to terrestriality in the guenons (tribe Cercopithecini). J. Hum. Evol. 46:223-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Damme, N., D. Goff, C. Katsura, R. Jorgenson, R. Mitchell, M. Johnson, E. Stephens, and J. Guatelli. 2008. The interferon-induced protein BST-2 restricts HIV-1 release and is downregulated from the cell surface by the viral Vpu protein. Cell Host Microbe 3:245-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Kuyl, A., C. Kuiken, J. Dekker, and J. Goudsmit. 1995. Phylogeny of African monkeys based upon mitochondrial 12S rRNA sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 40:173-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vodicka, M., W. Goh, L. Wu, M. Rogel, S. Bartz, V. Schweickart, C. Raport, and M. Emerman. 1997. Indicator cell lines for detection of primary strains of human and simian immunodeficiency viruses. Virology 233:193-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wertheim, J., and M. Worobey. 2007. A challenge to the ancient origin of SIVagm based on African green monkey mitochondrial genomes. PLoS Pathog. 3:e95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamashita, M., and M. Emerman. 2004. Capsid is a dominant determinant of retrovirus infectivity in nondividing cells. J. Virol. 78:5670-5678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang, F., S. Wilson, W. Landford, B. Virgen, D. Gregory, M. Johnson, J. Munch, F. Kirchhoff, P. Bieniasz, and T. Hatziioannou. 2009. Nef proteins from simian immunodeficiency viruses are tetherin antagonists. Cell Host Microbe 6:54-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]