Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The objective was to determine the effects of antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) on reversal and attenuation of established interstitial fibrosis in the cardiac troponin T (cTnT) mouse model of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) mutation.

BACKGROUND

Interstitial fibrosis is a characteristic pathological feature of HCM and a risk factor for sudden cardiac death. The cTnT-Q92 transgenic mice, generated by cardiac-restricted expression of human HCM mutation, show a two- to four-fold increase in interstitial fibrosis.

METHODS

We randomized the cTnT-Q92 mice to treatment with a placebo or NAC (250, 500, or 1,000 mg/kg/day) and included non-transgenic mice as controls (N = 5 to 13 per group). We performed echocardiography before and 24 weeks after therapy, followed by histologic and molecular characterization.

RESULTS

There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics of the groups. Treatment with NAC reduced myocardial concentrations of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2(E)-nonenal, markers of oxidative stress, by 40%. Collagen volume fractions comprised 1.94 ± 0.76% of the myocardium in non-transgenic, 6.2 ± 1.65% in the placebo, and 1.56 ± 0.98% in the NAC (1,000 mg/kg/day) groups (p < 0.001). Expression levels of Col1a1 and Col1a2 were also reduced significantly, as were levels of phosphorylated but not total p44/42, p38, and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Levels of oxidized mitochondrial and nuclear DNA were not significantly different.

CONCLUSIONS

Treatment with NAC reduced myocardial oxidative stress, stress-responsive signaling kinases, and fibrosis in a mouse model of HCM. The potential beneficial effects of NAC in reversal of cardiac phenotype in human HCM, the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in the young, merits investigation.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a relatively common disease characterized clinically by diastolic heart failure and sudden cardiac death (SCD) and pathologically by myocyte hypertrophy, disarray, and interstitial fibrosis (1,2). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is the most common cause of SCD in the young and a major cause of morbidity in elderly (3). Several clinical and pathological phenotypes, including the extent of interstitial fibrosis, have been associated with the risk of SCD and diastolic heart failure in HCM (4-6).

The genetic basis of HCM has been all but elucidated, and several hundred mutations in over a dozen sarcomeric proteins have been identified (1). In addition, mutations in several non-sarcomeric genes have been associated with cardiac hypertrophy. The latter phenotype is considered a phenocopy and not true HCM (1). Genotype-phenotype correlation studies show a considerable overlap in the phenotypic expression of HCM, and no phenotype is considered unique to a specific gene or mutation (7). Nevertheless, despite the presence of significant variability, the causal mutations impart considerable effects on the phenotypic expression of HCM. Accordingly, mutations in cardiac troponin T (cTnT), a major gene for HCM (1,8), are generally associated with relatively mild hypertrophy but severe myocyte disarray and interstitial fibrosis (8-11). The observed phenotype is recapitulated in the transgenic mouse models expressing mutant cTnT proteins, which show myocyte disarray and interstitial fibrosis but no discernible cardiac hypertrophy (12-15).

The pathogenesis of cardiac phenotype in HCM is largely unknown. We and others have proposed that the initial phenotypes imparted by the mutant sarcomeric proteins, although diverse, are functional (16). Accordingly, morphologic and histologic phenotypes are secondary phenotypes and hence could be reversed, attenuated, or prevented through interventions aimed at blocking the intermediary molecular phenotypes (17,18). Concerning the pathogenesis of interstitial fibrosis, the balance between oxidants and antioxidants is considered important for maintaining normal collagen homeostasis (19,20). Treatment with antioxidants, such as N-acetylcysteine (NAC), has been shown to attenuate interstitial fibrosis in several pathological states but not in the myocardium (19,20). Thus, we performed a randomized study to determine whether treatment with NAC could reverse or attenuate evolving interstitial fibrosis in the CTnT-Q92 transgenic mouse model of HCM, known to show a two-to four-fold increase in interstitial fibrosis (12,15).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The cTnT-Q92 transgenic mice

The Animal Subjects Committee of Baylor College of Medicine approved the experiments. The cTnT-Q92 transgenic mouse model has been published (12,15,17,21). In brief, cardiac-restricted expression of cTnT-Q92 leads to myocyte disarray, encompassing 10% to 30% of the myocardium, a two-to four-fold increase in interstitial collagen content, no cardiac hypertrophy, and increased Ca+2 sensitivity of isolated cardiac myofilaments (12,15,17,21).

Randomized placebo-controlled therapy

We randomized adult age- and gender-matched cTnT-Q92 mice to treatment with a placebo or NAC administered at 1,000 mg/kg/day (N = 13 per group). Age- and gender-matched non-transgenic mice (NTG) were included as controls (n = 13). To determine an effective dose range on interstitial fibrosis, two additional smaller groups of cTnT-Q92 were treated with 250 and 500 mg/kg/day of NAC (N = 5 per group). All mice underwent two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography before randomization and on completion of the six-month treatment. The mean daily water consumption per mouse was determined, and then aliquots of 7, 3.5, and 1.75 g NAC were dissolved in 800 ml water (pH was adjusted to 6.7) to deliver approximately 250, 500, and 1,000 mg/kg/day NAC to each mouse. The placebo group was given water alone. The duration of therapy was 24 weeks. After follow-up echocardiography, mice were euthanized for morphometric and molecular phenotyping.

M mode, two-dimensional, and Doppler echocardiography

Transthoracic and Doppler echocardiography were performed before and after completion of NAC therapy using an HP 5500 Sonos echocardiography unit equipped with a 15-MHz linear transducer, as published (15).

Myocardial lipid peroxide levels

Myocardial levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxyalkenals (HAE), the end products derived from peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and related esters, were measured using a commercially available kit per instructions of the manufacturer (Calbiochem Inc., San Diego, California). The assay is based on the spectrophotometric measurement of a chromophore at 586 nm, generated by condensation of either MDA or 4-HAE, with two molecules of N-methyl-2-phenylindole, as the chromogenic reagent. The reactions were performed in triplicate and in eight animals per group.

Morphometric analyses

All morphometric analyses were performed by an investigator who had no knowledge of the group assignment and in a random order of groups. Collagen volume fraction (CVF) was determined by quantitative automated planimetry as described previously (15). In brief, thin ventricular sections, cut parallel to the atrioventricular groove, were stained with collagen-specific Sirius red F3BA in 5% saturated picric acid. The percent myocardial area stained positive for Sirius R was determined in 12 fields per each thin section and 10 sections per mouse.

Real-time (RT) polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Expression levels of selected genes were determined by quantitative PCR using specific TaqMan probes and oligonucleotide primers in a 7900HT Sequence Detection System unit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, California) and were normalized to levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), as described previously (15). In brief, total cellular RNA was extracted by the guanidinium isothiocyanate method (TRIzol reagents, Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, California). Expression levels of the mRNAs for the Col1a1, Col1a2, and Col3A1, which encode procollagen Col1(α1), Col1(α2) and Col3(α1), respectively, the predominant cardiac collagens, were quantified by RT-PCR. Experiments were performed at least three times, and the mean values were used for comparisons.

Isolation of mtDNA and detection of oxidized nuclear DNA and mtDNA levels

Nuclear DNA and mtDNA were extracted from myocardial tissues as published (22). The purity of isolated mtDNA was determined by gel electrophoresis of mtDNA digested with BamHI. Immuno-slot blots were performed after incubation of the membranes with an anti-7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-guanine antibody (22). The intensity of the signal was quantified by densitometry and compared among the groups (N = 6 per group).

Immunoblotting

Expression levels and activation of selected signaling molecules implicated in mediating response to oxidative stress, including total and phosphorylated p44/42, p38, and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases (JNK), were detected as described (15). To re-probe, the membranes were stripped by incubating in 1% sodium dodecyl sulphate and 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol in Tris buffered saline (TBS) for 30 min at room temperature and then washed in TBS at least six times. The membranes were probed with specific antibodies to detect levels of total signaling proteins as well as levels of tubulin (monoclonal mouse antitubulin from Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, California) or sarcomeric actin as controls for loading conditions. Each set of the experiments was repeated three to five times, and expression levels of the proteins were quantified by spot densitometry.

Detection of myocardial matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity by zymography

Aliquots (50 mg) of myocardial tissues were homogenized in ice-cold extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 75 mM NaCl, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonylfluoride, pH 7.5, with 1 ml buffer per 50 mg tissue). The homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000g at 4°C for 20 min. Protein concentration of the supernatants was determined by Bradford assay. Protein samples were incubated for 10 min at room temperature in a double volume of Zymogram Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California) and loaded onto 10% gel (SDS-PAGE) containing 0.1% gelatin as the substrate under non-reducing conditions.

After electrophoresis, the gel was incubated in 1× Zymogram Renaturating Buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories) for 30 min at room temperature with gentle agitation. The renaturing buffer was decanted, and the gel was equilibrated in 1× Zymogram Developing Buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories) for 30 min at room temperature with gentle agitation. Gel was then incubated overnight in fresh developing buffer at 37°C. After the reaction, the gel was stained with 0.5% Coomassie brilliant blue R 250 for 30 min, and destained with methanol:acetic acid:water at a 50:10:40 ratio. Zones of protease activity were visualized as clear bands against the dark-blue background and were quantified by quantitative image analysis (N = 4 per group).

Statistical methods

Homogeneity of the variances was analyzed by Bartlett test. Differences in variables among the non-transgenic, placebo, and NAC groups were compared by analysis of variance for variables with equal standard deviation and by the non-parametric Kurskall-Wallis test for variables with unequal standard deviation. Pairwise comparisons were performed by Tukey test. Differences between the baseline and follow-up values in each group were compared by paired t test for variables with equal standard deviation and by Mann-Whitney test for variables with unequal standard deviation.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the cTnT-Q92 transgenic mice

The mean age, male:female ratio, heart rate, blood pressure, and body weight were not significantly different among the groups (Table 1). Cardiac phenotype in the cTnT-Q92 mice was as published (12,15,17). It was notable for normal wall thickness, left ventricular end diastolic diameter, aortic outflow maximum velocity, and mitral inflow E velocity. In contrast, left ventricular end systolic diameter was smaller and three indexes of left ventricular systolic performance, namely fractional shortening, velocity of circumferential fiber shortening, and left ventricular ejection fraction, were increased (Table 1). In addition, aortic ejection time was prolonged and mitral inflow E/A velocity was modestly reduced. The CVF was increased by approximately three-fold, and myocyte disarray comprised approximately 20% of the myocardium.

Table 1.

Effects of N-Acetylcysteine on Cardiac Structure and Function in cTnT-Q92 Mice

| cTnT-Q92 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-Acetylcysteine (mg/g/d) |

|||||

| Non-transgenic | Placebo | 250 | 500 | 1,000 | |

| N | 13 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 13 |

| Age (months) | 9.1 ± 2.2 | 9.3 ± 4.8 | 8.4 ± 3.6 | 8.7 ± 3.7 | 9.5 ± 3.7 |

| Gender (M/F) | 7/6 | 7/6 | 3/2 | 3/2 | 6/7 |

| Body weight (g) | 34.1 ± 4.3 | 33.9 ± 2.3 | 31.9 ± 6.2 | 33.7 ± 5.4 | 35.3 ± 3.2 |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 415 ± 36 | 409 ± 35 | 436 ± 42 | 420 ± 37 | 418 ± 39 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 89 ± 12 | 92 ± 17 | 84 ± 15 | 99 ± 21 | 91 ± 16 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 48 ± 9 | 42 ± 13 | 49 ± 11 | 45 ± 13 | 43 ± 14 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | |||||

| IVST (mm) | |||||

| BL | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 0.75 ± 0.04 | 0.71 ± 0.04 | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 0.72 ± 0.04 |

| FU | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 0.73 ± 0.07 | 0.78 ± 0.03 | 0.77 ± 0.06 | 0.76 ± 0.07 |

| PWT (mm) | |||||

| BL | 0.80 ± 0.08 | 0.78 ± 0.05 | 0.75 ± 0.04 | 0.72 ± 0.03 | 0.72 ± 0.08 |

| FU | 0.75 ± 0.05 | 0.72 ± 0.08 | 0.80 ± 0.09 | 0.76 ± 0.06 | 0.73 ± 0.05 |

| LVEDD (mm) | |||||

| BL | 4.2 ± 0.22 | 4.0 ± 0.31 | 3.8 ± 0.33 | 3.9 ± 0.29 | 4.3 ± 0.28 |

| FU | 4.3 ± 0.37 | 4.0 ± 0.29 | 4.1 ± 0.38 | 3.8 ± 0.35 | 4.3 ± 0.30 |

| LVESD (mm) | |||||

| BL | 3.0 ± 0.27 | 2.2 ± 0.44* | 2.1 ± 0.33* | 2.3 ± 0.40* | 2.4 ± 0.31* |

| FU | 3.1 ± 0.32 | 2.4 ± 0.38* | 2.3 ± 0.48* | 2.5 ± 0.29* | 2.6 ± 0.27* |

| FS (%) | |||||

| BL | 32.0 ± 3.7 | 44.1 ± 8.5* | 43.5 ± 6.9* | 41.1 ± 5.5* | 43.3 ± 5.7* |

| FU | 31.1 ± 5.1 | 40.0 ± 6.5* | 43.9 ± 4.8* | 42.7 ± 6.2* | 39.6 ± 3.5* |

| LVEF (%) | |||||

| BL | 63.7 ± 6.1 | 79.9 ± 8.1* | 78.3 ± 5.9* | 74.0 ± 7.2* | 79.9 ± 6.0* |

| FU | 61.5 ± 7.9 | 78.9 ± 7.3* | 79.0 ± 6.8 | 76.9 ± 8.4 | 75.9 ± 4.2* |

| Vcf (cm/s) | |||||

| BL | 5.8 ± 1.1 | 7.3 ± 1.6* | 7.4 ± 1.4* | 7.1 ± 1.5* | 7.2 ± 1.1* |

| FU | 5.4 ± 1.0 | 6.8 ± 1.7* | 7.2 ± 1.8* | 6.9 ± 1.7* | 6.5 ± 0.7* |

| Aortic peak ejection rate (cm/s) | |||||

| BL | 1.04 ± 0.12 | 1.1 ± 0.19 | 1.0 ± 0.17 | 0.99 ± 0.12 | 1.08 ± 0.14 |

| FU | 0.99 ± 0.12 | 0.93 ± 0.15 | 0.97 ± 0.09 | 1.03 ± 0.13 | 1.06 ± 0.12 |

| Aortic ejection time (ms) | |||||

| BL | 52.5 ± 3.6 | 62.1 ± 4.0* | 60.1 ± 4.5* | 61.1 ± 3.8* | 60.3 ± 4.2* |

| FU | 53.1 ± 6.0 | 63.8 ± 4.5* | 62.4 ± 4.3* | 60.9 ± 5.3* | 57.6 ± 4.3* |

| E/A ratio | |||||

| BL | 2.57 ± 1.2 | 2.01 ± 0.70 | 2.17 ± 0.9 | 2.09 ± 0.8 | 2.14 ± 0.65 |

| FU | 2.68 ± 1.1 | 2.40 ± 0.34 | 2.21 ± 1.2 | 2.22 ± 0.9 | 2.40 ± 0.84 |

All pairwise comparisons were performed by Tukey test. The following were compared by Kruskal-Wallis test because of unequal variances: age between NTG and placebo and between NTG and cTnT-Q92 (1,000); IVST between BL and FU in the placebo and in NAC-1,000 groups; LVEDD between BL and FU values; FS (%) at BL between NTG and placebo groups; FS (%) BL and FL values in NAC-1,000 group; LVEF (%)–FU between NTG and NAC-1,000; E/A ratio; FU values among the groups; and between BL and FU values in the placebo group.

p < 0.05 as compared with NTG.

BL = baseline; cTnT = cardiac troponin T; E/A ratio = mitral inflow early to late velocities; FS = fractional shortening; FU = follow-up; IVST = interventricular septal thickness; LVEDD = left ventricular end diastolic dimension; NTG = non-transgenic; PWT = posterior wall thickness; Q = glutamine; Vcf = velocity of circumferential fiber shortening.

Effects of NAC on cardiac structure and function

All mice survived the treatment with all three doses of NAC. Treatment with NAC had no significant effect on echocardiographic indexes of wall thickness, left ventricular size, or function, with the exception of a modest improvement in mitral inflow E/A ratio, which was of borderline statistical significance (Table 1).

Effects of NAC on plasma and myocardial lipid peroxide levels

Both plasma and myocardial lipid peroxide levels were reduced significantly (~40%) in the NAC group (1,000 mg/kg/day as compared with the placebo or NTG group (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Plasma and myocardial levels of lipid peroxides. Myocardial (A) and plasma (B) levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxyalkenals (HAE) are depicted in non-transgenic (NTG) and cardiac troponin T-Q92 (cTnT-Q92) transgenic mice treated with placebo or with N-acetylcysteine (NAC). *p < 0.05 for pairwise comparisons.

Effects of NAC on CVF and myocyte disarray

The CVF, quantified in 120 high-magnification microscopic fields (×400) per mouse, was increased by approximately threefold in the placebo group as compared with the NTG (Fig. 2). The CVF was within the normal range in all three NAC groups, regardless of the dose. Because all three doses of NAC were effective in reducing CVF to normal levels in the cTnT-Q92 mice, data are primarily presented for the 1,000 mg/kg/day group (Fig. 2). Myocyte disarray, determined in 120 high-magnification microscopic fields per mouse, comprised 3.1 ± 1.5% of the myocardium in the NTG mice, 12.6 ± 4.1% in the cTnT-Q92 transgenic mice in the placebo group (p < 0.001 compared with NTG), and 11.0 ± 3.2% in the NAC group (p = 0.673 compared with placebo).

Figure 2.

Effect of NAC on CVF. Panels in 2A show representative high-magnification microscopic fields (×400) in non-transgenic (NTG), cTnT-Q92 mice treated with placebo and cTnT-Q92 mice treated with NAC. (B) Quantitative values in the three groups. *p < 0.05 for pairwise comparisons.

Effects of NAC on expression levels of procollagen genes

Concordant with histologic data on CVF, expression levels of Col1a1 and Col1a2 mRNAs were increased by two- to three-fold in the placebo group but were normal in the NAC groups (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Expression levels of procollagen genes. Relative expression levels, corrected for the levels in NTG mice, are depicted for Col1a1, Col1a2, and Col3a1 procollagen genes.

Effects of NAC on levels of oxidized nuclear DNA and mtDNA

We detected no significant differences in the levels of oxidized nuclear DNA and mtDNAs among the experiment’s groups (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Oxidized nuclear and mitochondrial DNA levels. (A) mtDNA isolated and digested with BamH1 restriction enzyme, which results in two bands of approximately 8 and 9 kbp, indicating the purity of the isolated mtDNA. (B) Immuno-slot blot of mtDNA (upper blot) and the corresponding ethidium bromide stained blot (lower blot) in three mice in each of the experimental groups. (C) Immuno-slot blot (upper blot) of nuclear DNA and ethidium bromide stained blot (lower blot) in three mice per experimental group.

Effects of NAC on expression levels of MAPK signaling molecules

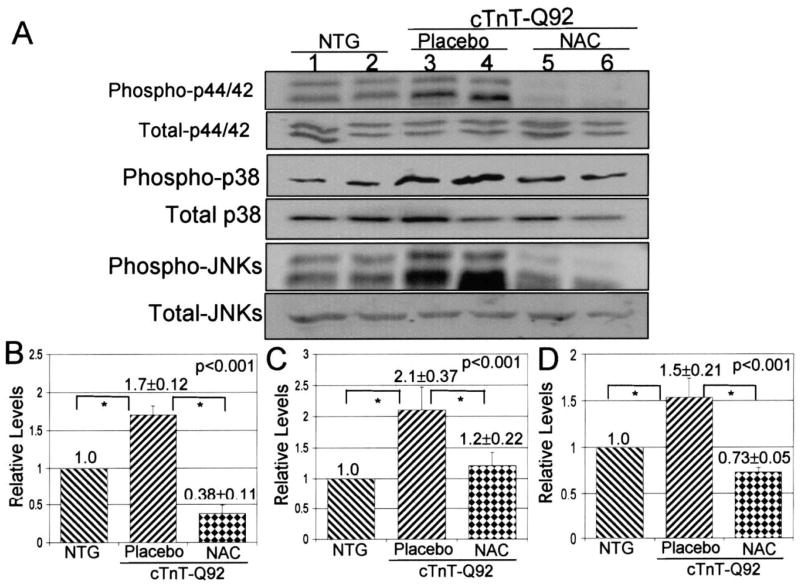

Expression levels of phosphorylated p44/42, p38, and JNK MAPKs were reduced significantly in all three NAC groups as compared with placebo or the NTG group (Fig. 5), and expression levels of total p44/42, p38, and JNK were not changed significantly.

Figure 5.

Expression levels of selected signaling kinases. (A) Immunoblots showing expression levels of phosphorylated and total p44/42, p38, and JNK. (B, C, and D) Quantitative analysis of the relative levels of phosphorylated p44/42, p38, and JNK, respectively, all normalized to levels in the corresponding NTG group, in the experimental groups. The sum of density of 44 and 42 kDa bands were used to quantify levels of p44/42. Similarly, the sum density of 46 and 54 kDa bands were used for quantification of JNK. *p < 0.05 for pairwise comparisons.

Effects of NAC on the activity of myocardial MMPs

Myocardial MMP-1 (interstitial collagenase) activity was increased by 44 ± 19% in the NAC group as compared with NTG. The difference was of borderline statistical significance (p = 0.078).

DISCUSSION

In a randomized placebo-controlled study, we showed that treatment with three different doses of antioxidant NAC reversed and normalized interstitial fibrosis in a mouse model of human HCM mutation without discernible effects on cardiac function. Treatment with NAC was associated with significant reductions in the expression levels of Col1a1 and Col1a2 mRNAs, major collagens in the myocardium. In addition, myocardial and to a lesser extent plasma levels of lipid peroxides were also reduced, as were levels of activated p44/42, p38, and JNK proteins. These findings in a transgenic mouse model of human HCM illustrate the potential utility of NAC in treatment of interstitial fibrosis, a major phenotype of human HCM and an important determinant of arrhythmogenesis and risk of SCD (4,6). Because interstitial fibrosis is a common response of the heart to all forms of stress or injury, the potential beneficial effects of NAC in reversal of fibrosis may not be restricted to this particular model of HCM but could encompass a variety of cardiovascular pathologies.

The finding of reversal of established cardiac fibrosis, although novel in a genetic animal model of human HCM mutation, is in accord with the data showing beneficial effects of the antioxidants in treatment of fibrosis in other conditions, including pulmonary, renal, and liver fibrosis (19,20). The observed antifibrotic effects occurred despite the absence of discernible increase in markers of myocardial oxidative stress in the cTnT-Q92 mice, as detected by levels of myocardial lipid peroxides and oxidized mtDNA. The latter finding could reflect the relative insensitivity of the methods for detection of a potentially modest and yet chronic increase in oxidative stress in a genetic animal model wherein the stimulus is relatively of low magnitude and chronic. Therefore, the data do not necessarily exclude potential involvement of a low level and chronic increase in oxidative stress in the development of interstitial fibrosis in the cTnT-Q92 mice. Alternatively, the finding could also suggest that treatment with NAC could impart antifibrotic effects in conditions wherein oxidative stress does not play a major or direct role in the pathogenesis of the phenotype.

The molecular mechanism(s) by which NAC imparts the antifibrotic effect is yet to be fully determined. Our data show reduced expression of procollagen genes as a potential mechanism for the antifibrotic effects of NAC in the myocardium. The results also implicate involvement of oxidative stress-responsive MAPK signaling in mediating the effects. In addition, myocardial MMP-1 and to a lesser degree MMP-9 activities were increased. However, the changes were modest and of borderline statistical significance. Additional experiments will be required to further delineate the role and contribution of MMPs and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases to resolution of interstitial fibrosis in the cTnT-Q92 mice. N-acetylcysteine is a precursor for glutathione, the most abundant intracellular non-protein thiol and a major redox molecule with various functions (19). Glutathione scavenges free radicals and other reactive oxygen species, reacts with other metabolites as well as with nitric oxide, and participates in the generation of prostaglandins (19). Oxidative stress and other noxious stimuli could deplete cellular glutathione, and hence exert adverse biological effects, which could be prevented by the administration of NAC. Accordingly, treatment with NAC has been shown to abrogate fibrosis induced by transforming growth factor-beta-1 (23). In addition, NAC could suppress expression of the procollagen genes even in the absence of transforming growth factor-beta-1 (23,24). As shown in the present study, treatment with NAC inhibited activation of p44/42, p38, and JNK kinases, important mediators of cell signaling in response to many forms of stress or injury. In addition, treatment with NAC has been shown to prevent activation of redox-sensitive activating protein-1 and nuclear factor kappa B transcription factors (19). Thus, the antifibrotic effects of NAC could entail multiple interacting or independent pathways, not necessarily restricted to transcriptional regulation of procollagen genes but also posttranslational modifications of the expressed proteins.

In the absence of an effective therapy to reverse or attenuate interstitial fibrosis in human patients with HCM, the findings of this study, once extended to human patients with HCM, could have considerable clinical implications. Elucidation of the molecular genetic basis of HCM has led to efforts to identify and establish an effective therapy for the HCM phenotype. We have previously shown the potentially beneficial effects of statins and inhibitors of the rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in attenuating an established phenotype in animal models of HCM (15,18). It is noteworthy that satins as well as the inhibitors of the rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone system all show antioxidant effects, a common theme with the salutary effects of NAC observed in the present study. It is intriguing to propose the antioxidants as potential therapeutic choices for human HCM. The cTnT-Q92 mice, however, do not show cardiac hypertrophy, which is often the case in human HCM caused by mutations in the cTnT protein (8-11). The phenotype in the cTnT-Q92 mice also differs from that in pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy, wherein stress-responsive signaling molecules are induced in early stages of cardiac hypertrophy and in the absence of fibrosis. The latter is a late phenotype that often occurs after deterioration of cardiac function. Nevertheless, the findings may not directly apply to conditions wherein interstitial fibrosis is accompanied by myocardial hypertrophy, such as most cases of human HCM. The existing data, however, suggest that the antifibrotic effect of NAC is independent of the underlying substrate and applicable to a broad range of pathological states (19,20). In addition, the plausibility of the clinical utility of NAC in treatment of human HCM is further underscored by the known antihypertrophic effects of NAC and other antioxidants (25,26). Moreover, NAC is considered a very safe drug with no known major side effects. Thus, HCM, a paradigm of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, could prove to be an excellent disease model for the salutary effects of NAC. Nonetheless, the potential utility of NAC in the treatment of human HCM, although biologically plausible, must await proof through direct experimentation. It is also noteworthy that there was no significant correlation between the extent or resolution of interstitial fibrosis and the echocardiographic indexes of ventricular diastolic function. The finding may reflect the relatively small extent of interstitial fibrosis in the cTnT-Q92 mice (6.2% of the myocardium) as well as involvement of additional extracellular matrix and cellular proteins, such as titin in the regulation of diastolic function (27). Finally, the three doses of NAC tested in this study were equally effective and within the doses shown to exerts biological effects in mice under various pathological states including fibrosis (28-30). Studies will be needed to determine the effective antifibrotic and possibly antihypertrophic doses of NAC in humans with HCM.

In conclusion, in a randomized placebo-controlled study, we have shown that treatment with NAC completely reverses established fibrosis in a mouse model of human HCM mutation. The findings could have considerable impact for treatment of interstitial fibrosis and possibly cardiac hypertrophy in humans with HCM. The significance of the findings is further enhanced in view of the absence of an established effective therapy to reverse interstitial fibrosis or hypertrophy in HCM, the most common cause of SCD in the young (3). Finally, given that interstitial fibrosis is a common phenotypic response of the heart to all forms of stress or injury, the findings could have implications for treatment of a variety of cardiovascular diseases.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Specialized Centers of Research P50-HL54313, RO1 HL68884, and grants from Greater Houston Community Foundation (TexGen) and The Methodist DeBakey Heart Center.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- cTnT

cardiac troponin T

- CVF

collagen volume fraction

- HCM

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- JNK

c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- mtDNA

mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- SCD

sudden cardiac death

References

- 1.Marian AJ. Clinical and molecular genetic aspects of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2005;1:53–63. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marian AJ. Recent advances in genetics and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Future Cardiol. 2005;1:341–53. doi: 10.1517/14796678.1.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maron BJ, Shirani J, Poliac LC, Mathenge R, Roberts WC, Mueller FO. Sudden death in young competitive athletes. Clinical, demographic, and pathological profiles. JAMA. 1996;276:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shirani J, Pick R, Roberts WC, Maron BJ. Morphology and significance of the left ventricular collagen network in young patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:36–44. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spirito P, Bellone P, Harris KM, Bernabo P, Bruzzi P, Maron BJ. Magnitude of left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1778–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006153422403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varnava AM, Elliott PM, Mahon N, Davies MJ, McKenna WJ. Relation between myocyte disarray and outcome in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:275–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01640-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arad M, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Phenotypic diversity in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2499–506. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.20.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watkins H, McKenna WJ, Thierfelder L, et al. Mutations in the genes for cardiac troponin T and alpha-tropomyosin in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1058–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504203321603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varnava AM, Elliott PM, Baboonian C, Davison F, Davies MJ, McKenna WJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: histopathological features of sudden death in cardiac troponin T disease. Circulation. 2001;104:1380–4. doi: 10.1161/hc3701.095952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujino N, Shimizu M, Ino H, et al. Cardiac troponin T Arg92Trp mutation and progression from hypertrophic to dilated cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol. 2001;24:397–402. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960240510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu M, Ino H, Yamaguchi M, et al. Autopsy findings in siblings with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by Arg92Trp mutation in the cardiac troponin T gene showing dilated cardiomyopathy-like features. Clin Cardiol. 2003;26:536–9. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960261112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oberst L, Zhao G, Park JT, et al. Dominant-negative effect of a mutant cardiac troponin T on cardiac structure and function in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1498–505. doi: 10.1172/JCI4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tardiff JC, Factor SM, Tompkins BD, et al. A truncated cardiac troponin T molecule in transgenic mice suggests multiple cellular mechanisms for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2800–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tardiff JC, Hewett TE, Palmer BM, et al. Cardiac troponin T mutations result in allele-specific phenotypes in a mouse model for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:469–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsybouleva N, Zhang L, Chen SN, et al. Aldosterone, through novel signaling proteins, is a fundamental molecular bridge between the genetic defect and the cardiac phenotype of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2004;109:1284–91. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121426.43044.2B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marian AJ. Pathogenesis of diverse clinical and pathological phenotypes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2000;355:58–60. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)06187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim DS, Lutucuta S, Bachireddy P, et al. Angiotensin II blockade reverses myocardial fibrosis in a transgenic mouse model of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;103:789–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.6.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel R, Nagueh SF, Tsybouleva N, et al. Simvastatin induces regression of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis and improves cardiac function in a transgenic rabbit model of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2001;104:317–24. doi: 10.1161/hc2801.094031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zafarullah M, Li WQ, Sylvester J, Ahmad M. Molecular mechanisms of N-acetylcysteine actions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:6–20. doi: 10.1007/s000180300001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poli G, Parola M. Oxidative damage and fibrogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;22:287–305. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solaro RJ, Varghese J, Marian AJ, Chandra M. Molecular mechanisms of cardiac myofilament activation: modulation by pH and a troponin T mutant R92Q. Basic Res Cardiol. 2002;97(Suppl 1):I102–10. doi: 10.1007/s003950200038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senthil V, Chen SN, Tsybouleva N, et al. Prevention of cardiac hypertrophy by atorvastatin in a transgenic rabbit model of human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2005;97:285–92. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000177090.07296.ac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu RM, Liu Y, Forman HJ, Olman M, Tarpey MM. Glutathione regulates transforming growth factor-β-stimulated collagen production in fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L121–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00231.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segawa M, Kayano K, Sakaguchi E, Okamoto M, Sakaida I, Okita K. Antioxidant, N-acetyl–cysteine inhibits the expression of the collagen α2 (I) promoter in the activated human hepatic stellate cell line in the absence as well as the presence of transforming growth factor-β. Hepatol Res. 2002;24:305–15. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(02)00089-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakagami H, Takemoto M, Liao JK. NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide anion mediates angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:851–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higuchi Y, Otsu K, Nishida K, et al. Involvement of reactive oxygen species-mediated NF-κ B activation in TNF-α-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:233–40. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granzier HL, Labeit S. The giant protein titin: a major player in myocardial mechanics, signaling, and disease. Circ Res. 2004;94:284–95. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000117769.88862.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shahzeidi S, Sarnstrand B, Jeffery PK, McAnulty RJ, Laurent GJ. Oral N-acetylcysteine reduces bleomycin-induced collagen deposition in the lungs of mice. Eur Respir J. 1991;4:845–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ivanovski O, Szumilak D, Nguyen-Khoa T, et al. The antioxidant N-acetylcysteine prevents accelerated atherosclerosis in uremic apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Kidney Int. 2005;67:2288–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghezzi P, Ungheri D. Synergistic combination of N-acetylcysteine and ribavirin to protect from lethal influenza viral infection in a mouse model. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2004;17:99–102. doi: 10.1177/039463200401700114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]