Abstract

Liver fibrosis is a common scarring response to all forms of chronic liver injury and is always associated with inflammation that contributes to fibrogenesis. Although a variety of cell populations infiltrate the liver during inflammation, it is generically clear that CD8 T lymphocytes promote while natural killer (NK) cells inhibit liver fibrosis. However, the role of invariant NKT (iNKT) cells, which are abundant in the liver, in hepatic fibrogenesis, remains obscure. Here we show that iNKT-deficient mice are more susceptible to carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced acute liver injury and inflammation. The protective effect of naturally activated iNKT in this model is likely mediated via suppression of the proinflammatory effect of activated hepatic stellate cells. Interestingly, strong activation of iNKT through injection of iNKT activator α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) accelerates CCl4-induced acute liver injury and fibrosis. In contrast, chronic CCl4 administration induced a similar degree of liver injury in iNKT-deficient and wild-type mice, and only slightly higher grade of liver fibrosis in iNKT-deficient mice than wild-type mice 2 weeks but not 4 weeks post CCl4 injection although iNKT cells are able to kill activated stallate cells. An insignificant role of iNKT in chronic liver injury and fibrosis may be due to hepatic iNKT cell depletion. Finally, chronic α-GalCer treatment had little effect on liver injury and fibrosis, which is due to iNKT tolerance after α-GalCer injection.

Conclusion

natural activation of hepatic iNKT cells inhibits while strong activation of iNKT cells by α-GalCer accelerates CCl4-induced acute liver injury, inflammation, and fibrosis. During chronic liver injury, hepatic iNKT cells are depleted and play a role in inhibiting liver fibrosis in the early stage but not the late stage of fibrosis.

Keywords: invariant NKT, liver fibrosis, inflammation, cytokines

Introduction

Worldwide, alcohol drinking, hepatitis viral infection, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis are the 3 major causes of chronic liver inflammation and injury, leading to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver fibrosis is characterized by an accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins, which are mainly produced by activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs).1-5 Increasing evidence suggests that the interaction of HSCs with inflammatory cells that are always associated with liver fibrosis plays an important role in the fibrogenesis.1-5 Most notably, CD8 T cells have been shown to promote liver fibrosis via activation of HSCs 6 while natural killer (NK) cells inhibit liver fibrosis via killing of activated HSCs.7-10 However, the role of invariant NKT (iNKT) cells, which are abundant in the liver, in hepatic fibrogenesis is not clear.

NKT cells are a heterogeneous population of T lymphocytes that express markers of NK cells and T cell receptors (TCR).11, 12 These cells recognize endogenous lipid antigen isoglobotriaosylceramide (iGb3) and exogenous lipid antigens such as α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) by the nonclassical MHC class I like molecule CD1.11, 12 CD1-dependent NKT cells can be broadly categorized into type I and type II NKT cells. Type I NKT cells, also known as “classical” NKT cells, iNKT cells, and Vα14NKT cells, express the semi-invariant αβ TCR encoded by the Vα14 and Jα18 paired with a set of Vβ chains. Type I iNKT cells, which make up 90% to 95% of total NKT cells and recognize α-GalCer, are not detected in either Jα18-/- (iNKT-deficient) or CD1d-/- mice.11, 12 Type II NKT cells, also known as “nonclassical” NKT cells, express diverse TCRs and recognize sulfatide, but not α-GalCer. Type II NKT cells make up less than 5% of total NKT cells and are not detected in CD1d-/- mice, but can be detected in Jα18-/- mice.11, 12

Liver lymphocytes are abundant in iNKT cells.13-17 For example, mouse liver lymphocytes contain about 30% to 40% NKT cells, while peripheral blood lymphocytes contain less than 5% NKT cells.13, 14 Activation of iNKT cells by Concanavalin A or α-GalCer induces acute hepatitis,17-19 suggesting that iNKT cell activation contributes to acute liver injury. Increasing evidence suggests that iNKT cells also contribute to the pathogenesis of a variety of liver disorders,16 including viral hepatitis,20, 21 alcoholic liver injury,22 primary biliary cirrhosis,23, 24 bile duct ligation-induced liver injury,25 and drug-induced liver injury.26, 27 However, the role of iNKT cells in chronic liver inflammation and fibrosis remains poorly understood.28 In this study, we investigated extensively the role of iNKT cells in hepatic inflammation, injury, and fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4). Our findings suggest that natural activation of iNKT cells by endogenous lipid antigens plays a protective role, while strong activation of iNKT cells by exogenous lipid antigen α-GalCer plays a detrimental role in CCl4-induced acute liver injury, inflammation, and fibrosis. Moreover, chronic administration of CCl4 depletes hepatic iNKT and induces a higher grade of liver fibrosis in Jα18-/- (iNKT-deficient) mice than wild-type mice 2 weeks post administration, but similar grade of liver fibrosis 4 weeks post injection. Interestingly, repeated treatment with α-GalCer had little effect on CCl4-induced chronic liver injury and fibrosis, which may be due to iNKT tolerance.

Materials and Methods

Mice

iNKT-deficient (Jα18-/-) mice on C57BL6 background were kindly provided by Dr. Rachel Caspi (NEI, NIH) with permission from Dr. Taniguchi (RIKEN Research Center for Allergy and Immunology, Japan). Mice lacking the Jα18 gene segment are devoid of Vα14 iNKT cells, but other lymphoid cell lineages are intact.29 Mice deficient in interferon-γ (IFN-γ-/-) on C57BL6 background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). STAT1 deficient mice (STAT1-/-) on C57BL6 background were described previously.30 All male mice were used in the present study and were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility and were cared for in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved by the NIAAA animal care and use committee.

Liver injury induced by CCl4

For acute liver injury induced by CCl4, mice were injected IP with a single dose of CCl4 (10% in olive oil, 2 mL/kg). For chronic liver injury, mice were injected IP with CCl4 (10% in olive oil, 2 mL/kg, 3 times/week) for 2 or 4 weeks. Control groups were treated with vehicle (2 mL/kg of olive oil). After mice were sacrificed, liver tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. There was no mortality in wild-type and Jα18-/- mice after acute or chronic CCl4 treatment.

α-GalCer injection

A stock solution of α-GalCer (Alexis Biochemicals Corp., San Diego, CA) was diluted to 0.2 mg/mL in 0.5% polysorbate-20 and stored at −20°C. Mice were treated acutely with α-GalCer (2 μg/200μL in PBS per mouse) by IP injection 3 h before CCl4 administration. Chronic administration of α-GalCer (2 μg/200μL in PBS per mouse) was carried out by IP injection once or twice a week. There was no mortality in mice treated with CCl4+α-GalCer.

Other methods

The following methods are described in the supporting materials. Histology and immunohistochemistry, TUNEL assay, Western blotting, real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR), measurement of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and serum cytokines, isolation and in vitro culture of HSC and Kupffer cells, isolation of mouse liver lymphocytes, liver NKT cells, and flow cytometric analysis, cytotoxicity of liver lymphocytes and NKT cells against HSCs.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means±SD. To compare values obtained from three or more groups, one-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, followed by Tukey's post hoc test. To compare values obtained from two groups, the student t test was performed. Statistical significance was taken at the P<0.05 level.

Results

iNKT-deficient (Jα18-/-) mice are more susceptible to acute liver injury and inflammation induced by CCl4

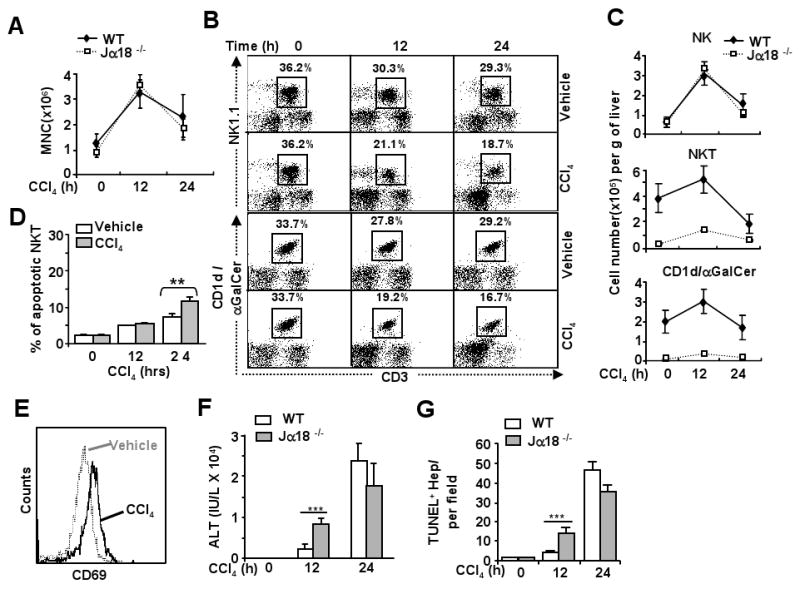

After CCl4 treatment, the total number of mononuclear cells in the liver increased, with peak effect occurring 12 h post administration. A similar increase was also observed in Jα18-/- mice (Fig. 1A). FACS analyses in Fig. 1B show that CCl4 treatment significantly decreased the percentage of NKT cells in liver lymphocytes. The total number of NKT cells increased slightly at 12 h and then decreased significantly 24 h post CCl4 treatment (Fig. 1C). Vehicle injection only caused a slight decrease in NKT cells (Fig. 1B). As expected, the number of NKT cells was very low in Jα18-/- mouse livers (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. Jα18-/- mice are more susceptible to CCl4-induced acute liver injury.

Jα18-/- and wild-type mice were treated with CCl4, and liver lymphocytes were analyzed by FACS. A. Total number of mononuclear cells (MNCs) per gram of liver. B. FACS analyses of liver NK and NKT cells with CD3 and NK1.1 antibodies or α-GalCer/CD1d tetramer. C. Total numbers of NK cells (NK1.1+CD3-), NKT cells (NK1.1+CD3+), or (CD3+CD1d/α-GalCer+). D. Liver lymphocytes were analyzed with anti-NK1.1 and anti-CD3 antibodies and Annexin V to determine NKT cell apoptosis. E. Liver lymphocytes from vehicle or CCl4-treated mice at 12 h time points were analyzed by FACS using NK1.1, CD3, and CD69 antibodies. The density of CD69 expression on NKT cells is shown. F. Serum levels of ALT. G. The number of TUNEL+ hepatoctyes in the livers post CCl4 injection. Values are shown as means±SD from 6 to 10 mice per each group. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

To determine whether downregulation of hepatic NKT cells after CCl4 treatment is due to NKT cell death or loss of NKT markers, iNKT cell apoptosis was examined. As shown in Fig. 1D, hepatic iNKT cell apoptosis increased after injection of vehicle or CCl4, but was much higher in CCl4 group than in vehicle group. Moreover, expression of activation marker CD69 increased on hepatic NKT cells 12 h post CCl4 treatment compared with vehicle group (Fig. 1E), suggesting that hepatic NKT cells are activated after CCl4 treatment.

Shown in Fig. 1F, serum ALT levels were much higher in Jα18-/- mice than in wild-type mice 12 h post CCl4 treatment, but were comparable in both groups at 24 h. TUNEL analyses showed that the number of apoptotic hepatocytes was greater in Jα18-/- mice than in wild-type mice 12 h post CCl4 administration, but no difference was observed between these 2 groups at 24 h (Fig. 1G and supplemental Fig. 1).

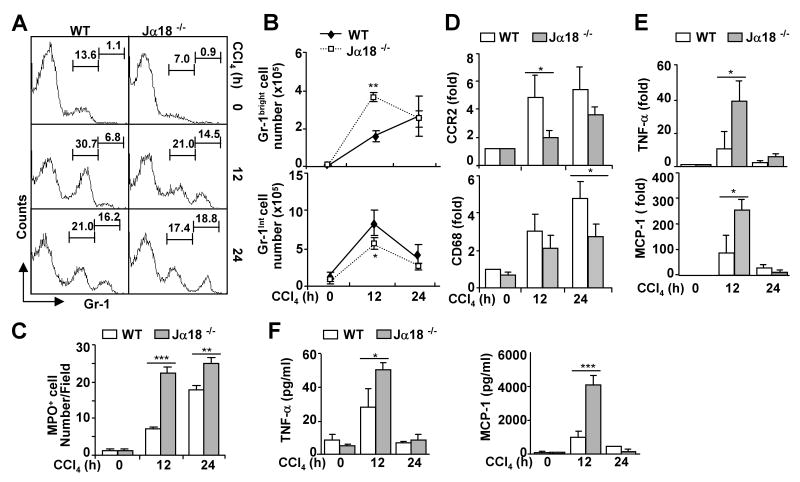

To examine hepatic inflammation after acute CCl4 injection, we measured the infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes into the liver by FACS analyses of Gr-1 expression. It was reported that Gr-1high cells mainly represent neutrophils while Gr-1intermediate cells represent monocytes and eosinophils.31 As shown in Figs. 2A-B, infiltration of Gr-1high neutrophils increased after CCl4 treatment, which was higher in Jα18-/- mice than in wild-type mice 12 h post injection but was comparable 24 h post injection. CCl4 treatment also induced infiltration of Gr-1int monocytes but such infiltration was lower in Jα18-/- mice compared with wild-type mice 12 h post injection. Furthermore, immunohistochemistry staining confirmed the neutrophilic (MPO+ cells) infiltration after CCl4 treatment, which was significantly higher in Jα18-/- mice than in wild-type mice (Fig. 2C and supplemental Fig. 2A). Moreover, expression of hepatic CCR2 and CD68 (markers of monocytes/macrophages) was induced by CCl4 treatment, but such induction was less evident in Jα18-/- mice than in wild-type mice (Fig. 2D), which is consistent with the findings in Fig. 2A showing that the number of Gr-1int monocytes was lower in Jα18-/- mice than in wild-type mice.

Fig. 2. Jα18-/- mice are more susceptible to CCl4-induced acute liver inflammation.

Jα18-/- and wild-type mice were treated with CCl4 for 12 h and 24 h. A. Liver lymphocytes were analyzed by FACS with anti-Gr-1 antibody. B. Total number of Gr-1high cells (neutrophils) and Gr-1int cells (monocytes) from panel A was calculated. C. The number of MPO+ cells in the livers post CCl4 injection. D. Real-time PCR analyses of liver CCR2 and CD68 (markers of monocytes/macrophages) expression. E. Real-time PCR analyses of liver cytokine gene expression. F. Serum levels of cytokines. Values are shown as means±SD from 6 to 10 mice per each group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with the corresponding wild-type groups.

Furthermore, CCl4 treatment elevated serum and hepatic TNF-α and MCP-1, such elevation was higher in Jα18-/- mice than in wild-type mice (Figs. 2E-F). In addition, CCl4–mediated induction of serum and hepatic levels of IL-6 was comparable between Jα18-/- and wild-type mice (supplemental Fig. 3). Hepatic levels of IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 remained unchanged after CCl4 treatment, and were comparable between Jα18-/- and wild-type mice (supplemental Fig. 3).

CCl4 metabolism is comparable between wild-type and Jα18-/- mice

Since p450 CYP2E1-mediated CCl4 metabolism plays a key role in CCl4-induced liver injury, we wondered whether acceleration of liver injury in Jα18-/- mice was due to alterations in CCl4 metabolism in these mice. Expression of CYP2E1 was comparable in the livers from wild-type and Jα18-/- mice (supplemental Fig. 4). After the CCl4 challenge, expression of CYP2E1 decreased significantly in wild-type mice, as shown by Western blot and immunohistochemical analyses (supplemental Fig. 4). A similar downregulation was also observed in Jα18-/- mice, suggesting that CCl4 metabolism is similar in wild-type and Jα18-/- mice (supplemental Fig. 4).

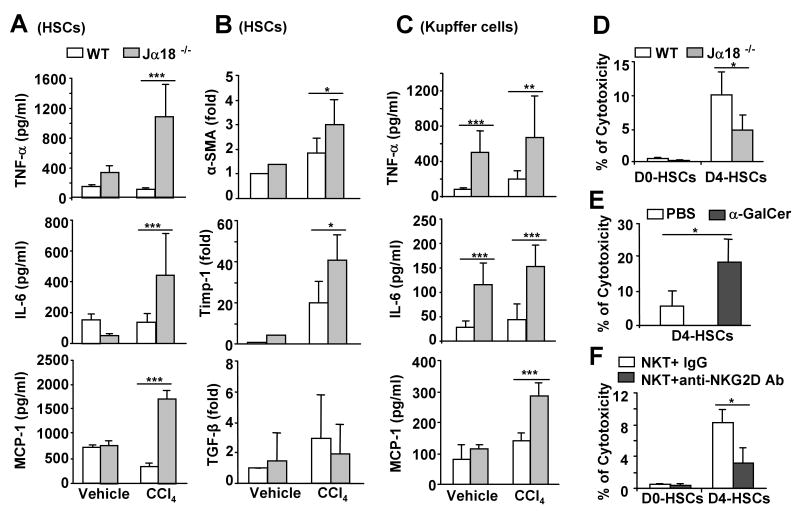

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) from CCl4-treated Jα18-/- mice produce greater levels of proinflammatory cytokines than those from wild-type mice

To understand why serum and hepatic cytokines were higher in Jα18-/- mice than in wild-type mice after CCl4 treatment, Kupffer cells and HSCs from these mice were isolated and cultured. As shown in Figs. 3A-B, HSCs from CCl4-treated Jα18-/- mice produced greater levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1, and expressed higher levels of α-SMA and Timp-1 but not TGF-β compared to those from CCl4-treated wild-type mice. Kupffer cells from CCl4-treated Jα18-/- mice also produced greater levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1 than those from CCl4-treated wild-type mice (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, the basal levels of TNF-α and IL-6 production by Kupffer cells were higher in Jα18-/- mice compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 3C). In contrast, production of IL-12, IFN-γ, and IL-10 by HSCs or Kupffer cells was comparable between Jα18-/- and wild-type mice (data not shown).

Fig. 3. Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) from CCl4-treated Jα18-/- mice produce more cytokines and NKT cells kill early activated HSCs via an NKG2D-dependent mechanism.

HSCs and Kupffer cells were isolated from wild-type and Jα18-/- mice treated with CCl4 or vehicle (olive oil) for 12 h, and cultured in vitro for 12 h. A, The levels of cytokines from the supernatant of cultured HSCs. B. Expression of α-SMA, Timp-1, and TGF-β mRNA from the cultured HSCs. C. The levels of cytokines from the supernatant of cultured Kupffer cells. D. Liver lymphocytes from wild-type and Jα18-/- mice were incubated with freshly isolated HSCs (D0-HSCs) or 4-day cultured HSCs (D4-HSCs) for 4 h. HSC cell death was determined. E. Liver lymphocytes were isolated from mice treated with PBS or α-GalCer for 3 h. Cytotoxicity against D4-HSCs was determined. F. Purified liver NKT cells were incubated with D0- or D4-HSCs in the presence of IgG control or anti-NKG2D antibody for 4 h. The cell death of HSCs was determined. Values in panels represent means±SD from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01,***P<0.001.

The findings that production of higher levels of cytokines by HSCs in Jα18-/- mice after CCl4 treatment suggest that iNKT cells may inhibit HSC activation. Previous studies have shown that NK cells were able to kill HSCs.7-9 This led us to test the hypothesis that NKT cells may also be able to kill HSCs. Shown in Fig. 3D, D0-HSCs were resistant to the cytotoxicity of liver lymphocytes (less than 1% cytotoxicity was observed), while D4-HSCs were susceptible to such killing. Liver lymphocytes from wild-type mice demonstrated 10% cytotoxicity against D4-HSCs, but only 5% from corresponding liver lymphocytes from Jα18-/- mice that are devoid of iNKT cells, suggesting that NKT cells play an important role in killing activated HSCs (D4-HSCs). The cytotoxicity of liver lymphocytes against D4-HSCs was enhanced after acute α-GalCer treatment (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, purified liver NKT cells were able to kill D4-HSCs, which was significantly attenuated by treatment with an anti-NKG2D antibody (Fig. 3F).

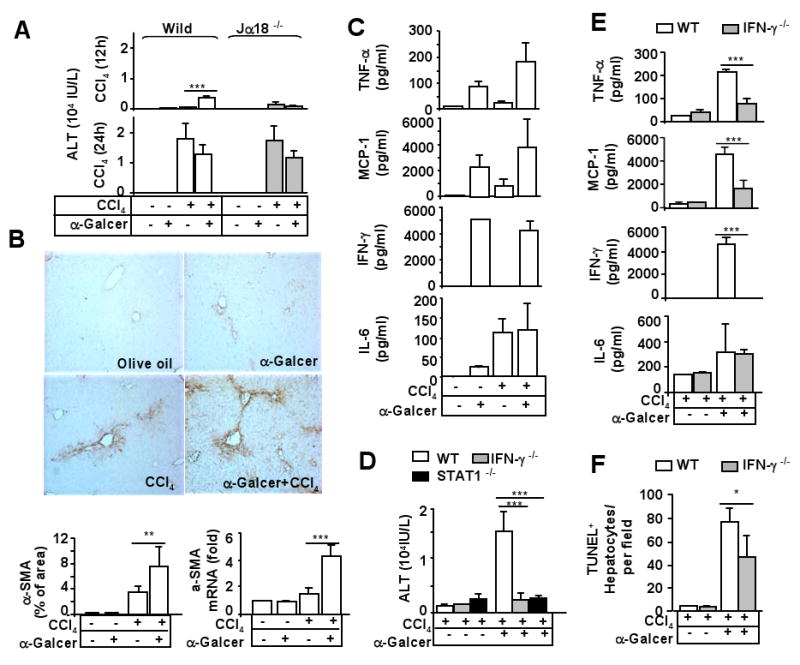

Activation of iNKT cells by a single dose of α-GalCer synergistically enhances CCl4-induced acute liver injury and fibrosis: Dependent on IFN-γ/STAT1

It has been reported that activation of iNKT cells by α-GalCer, an iNKT activator, results in mild liver injury.19 Here we examined the effects of α-GalCer on CCl4-induced liver injury. As shown in Fig. 4A, at 12 h time point, treatment with α-GalCer or CCl4 alone yielded mild elevations in serum ALT levels to 200 IU/L and 1200 IU/L, respectively, while cotreatment with α-GalCer and CCl4 elevated synergistically serum ALT levels up to 6000 IU/L. Such synergistic effect was not observed in Jα18-/- mice. At 24 h time point, treatment with α-GalCer did not further enhance CCl4 –induced elevation of serum ALT levels in wild-type and Jα18-/- mice. Moreover, α-GalCer pre-treatment enhanced significantly liver fibrosis 72 h post CCl4 injection, as demonstrated by enhancing α-SMA immunostaining and mRNA in the liver (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Activation of iNKT by α-GalCer accelerates CCl4-induced acute liver injury via an IFN-γ/STAT1 dependent manner.

A. Wild-type and Jα18-/- mice were treated with CCl4 and/or α-GalCer for 12 h and 24 h. Serum ALT levels were measured. B. C57BL6 mice were treated with CCl4 and/or α-GalCer for 72 h. Liver tissues were collected and stained with anti-α-SMA antibody or subject to real-time PCR analysis with α-SMA primer. The α-SMA+ area was quantified. C. Serum levels of cytokines 12 h post CCl4 and/or α-GalCer treatment. D. Wild-type and knock out mice were treated with CCl4 and/or α-GalCer for 12 h. Serum ALT levels were measured. E, F. Wild-type and IFN-γ-/- mice were treated with CCl4 or CCl4 plus α-GalCer for 12 h. Serum were collected for cytokine measurement (panel E). Liver tissues were collected to determine hepatocyte apoptosis by TUNEL assay (panel F). Values represent means±SD (n=5-10 mice/per group). *P<0.01, **P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

To understand the mechanisms underlying α-GalCer acceleration of CCl4-induced acute liver injury, serum cytokines were measured. Treatment with α-GalCer elevated a variety of serum cytokines, including TNF-α, MCP-1, IFN-γ, and IL-6 (Fig. 4C). Injection with CCl4 by itself elevated TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-6. Co-treatment with CCl4 and α-GalCer induced synergistically elevation of TNF-α but not other cytokines. Since α-GalCer injection induced high levels of serum IFN-γ, we wondered whether IFN-γ and its downstream signal STAT1 contributed to α-GalCer acceleration of CCl4-induced liver injury. As shown in Fig. 4D, CCl4 treatment induced a similar grade of liver injury in wild-type, IFN-γ-/-, and STAT1-/- mice. α-GalCer treatment enhanced synergistically CCl4-mediated liver injury in wild-type mice but not in IFN-γ-/- and STAT1-/- mice. α-GalCer injection alone induced mild liver injury (ALT reached to 300 IU/L) in wild-type mice but not in IFN-γ-/- and STAT1-/- mice (data not shown). Moreover, induction of TNF-α, MCP-1, but not IL-6, by α-GalCer was diminished in IFN-γ-/- mice (Fig. 4E). Finally, α-GalCer treatment significantly increased the number of hepatocyte apoptosis in CCl4-treated mice, which was partially diminished in IFN-γ-/- mice (Fig. 4F).

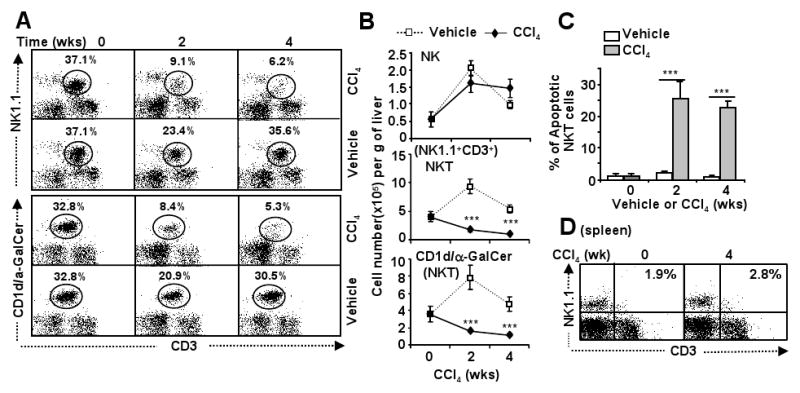

Chronic CCl4 treatment induces hepatic iNKT cell depletion

The data above revealed that acute treatment with CCl4 resulted in iNKT depletion in the liver. Next we examined the effects of chronic CCl4 treatment on hepatic NKT cells. As shown in Fig. 5A, normal C57BL6 mouse liver contains about 37% NK1.1+CD3+ and 32% CD3+CD1d/αGalCer+ cells. In the livers of 2- or 4-week CCl4-treated mice, the percentage of NKT (NK1.1+CD3+ or CD3+CD1d/αGalCer+) cells decreased significantly. Interestingly, vehicle injection also slightly reduced the percentage of NKT cells but increased the total number of NKT cells 2 weeks post injection (Figs. 5A-B). The total number of NKT cells in the liver was markedly decreased 2 and 4 weeks post CCl4 injection (Fig. 5B). In contrast, vehicle and CCl4 both increased the total number of NK cells (Fig. 5B). Fig. 5C shows that the percentage of apoptotic liver NKT cells increased significantly from 2- or 4-week CCl4-treated mice, suggesting that NKT depletion was due to apoptosis after chronic CCl4 treatment. Finally, Fig. 5D shows that the percentage of NKT (NK1.1+CD3+) in the spleen increased slightly after chronic CCl4 treatment.

Fig. 5. Chronic CCl4 treatment induces hepatic iNKT cell depletion.

A, B. C57BL/6 mice were treated with CCl4 or vehicle for up to 4 weeks, and then killed 24 h post the last injection. Liver lymphocytes were analyzed by FACS. Total numbers of NK cells (NK1.1+CD3-) and NKT cells (NK1.1+CD3+ or CD3+CD1d/α-GalCer+) were counted. C. Liver lymphocytes were also analyzed with anti-NK1.1 and anti-CD3 antibodies and Annexin V to determine NKT cell apoptosis. D. Splenocytes were isolated from mice in panel A and analyzed by FACS. Values represent means±SD (n=5-8). ***P<0.001 in comparison with corresponding vehicle-treated groups.

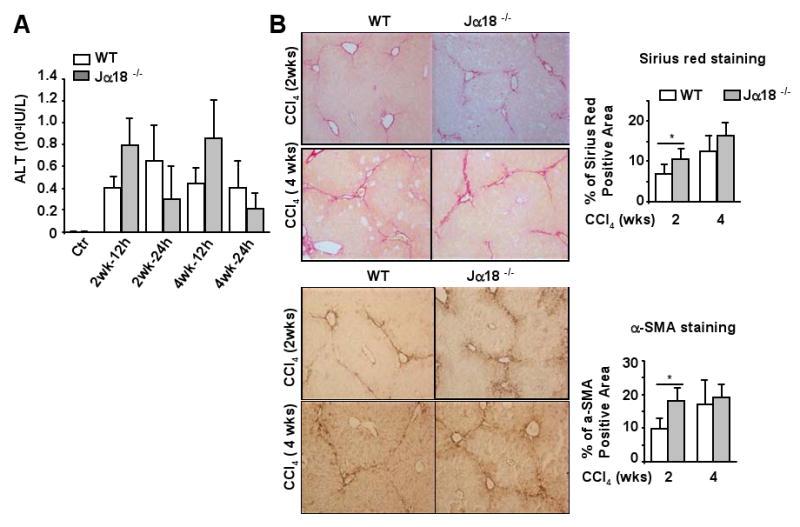

iNKT cells play a role in inhibiting liver fibrosis in the early stage but not late stage of liver fibrosis induced by chronic CCl4 treatment

The role of iNKT cells in CCl4-induced chronic liver injury and fibrosis was examined in wild-type and Jα18-/- mice. As shown in Fig. 6A, serum levels of ALT were similar in Jα18-/- and wild-type mice 2 and 4 weeks post CCl4 injection. Fig. 6B shows that chronic CCl4 injection induced slightly higher levels of collagen deposition (Sirius red staining) and HSC activation (α-SMA staining) in Jα18-/- mice than in wild-type mice 2 weeks but similar grade of liver fibrosis 4 weeks post injection. Serum levels of TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-6, as well as hepatic levels of TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-6, IL-12, and CCR2 were elevated similarly between these 2 groups post CCl4 treatment (data not shown).

Fig. 6. Chronic CCl4 treatment induces a higher grade of liver fibrosis in Jα18-/- mice than in wild-type mice 2 weeks but not 4 weeks post injection.

Jα18-/- and wild-type mice were treated with CCl4 for 2 or 4 weeks, and then killed 12 h or 24 h post the last injection. A. Serum ALT levels were measured. B. Liver tissues were collected 24 h post the last injection and stained with Sirius red or α-SMA antibody. Sirius red and α-SMA positive staining area were quantified. Values represent means ± SD (n=10-12). *P<0.05.

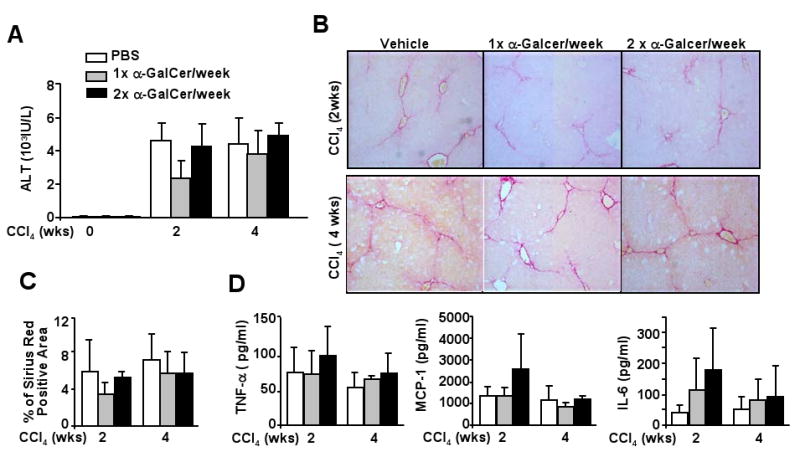

Chronic treatment with α-GalCer has little effect on CCl4-induced chronic liver injury and fibrosis

The effects of chronic treatment with the iNKT activator α-GalCer on CCl4-induced liver injury and fibrosis are shown in Fig. 7. Surprisingly, serum levels of ALT, liver fibrosis grade, and serum cytokine levels (ie, IL-6, MCP-1, and TNF-α) were comparable between groups treated with CCl4 alone or with CCl4 plus α-GalCer injection (Figs. 7A-D). Serum levels of IL-4 and IL-10 were under the detectable limit in these groups. Hepatic expression of Th2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 was comparable between CCl4 and CCl4 plus α-GalCer group (supplemental Fig. 5). Chronic α-GalCer injection alone had little effect on liver injury and fibrosis (data not shown).

Fig. 7. Repeated α-GalCer injection has little effect on CCl4-induced liver fibrosis.

C57BL6 mice were treated with CCl4 plus α-GalCer (once or twice a week) for 2 or 4 weeks, and then killed 24 h post the last injection. A. Serum ALT levels. B, C. Liver tissues were stained with Sirius red, and positive staining area was quantified. D. Serum levels of cytokines. Values represent means±SD (n=10-15).

Discussion

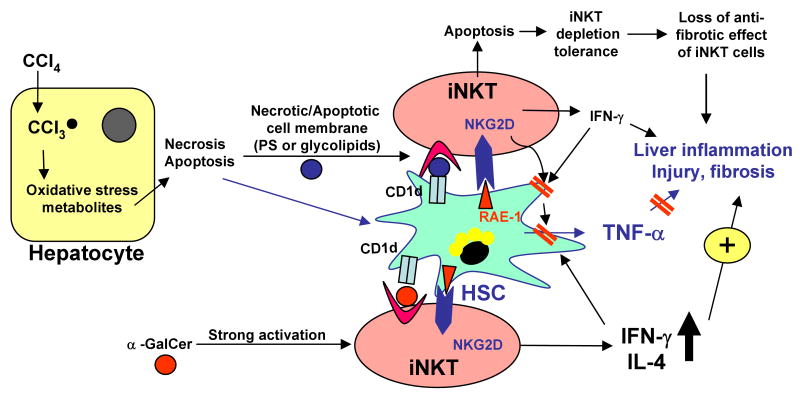

In this paper, we extensively investigated the role of iNKT cells in acute and chronic liver injury, inflammation, and fibrosis. Our findings indicate that (a) natural activation of iNKT cells inhibits CCl4-induced acute liver injury, while strong iNKT activation by the exogenous ligand α-GalCer accelerates CCl4-induced acute liver injury and fibrosis; (b) acute and chronic CCl4 treatment induces hepatic iNKT cell depletion; (c) iNKT cells play a role in inhibiting liver fibrosis at the early stage but not late stage; (d) Repeated injection of exogenous iNKT ligand α-GalCer has little effect on chronic CCl4-induced liver injury and fibrosis. We have integrated these findings into a model (summarized in Fig. 8) depicting the complex role of iNKT in CCl4-induced acute and chronic liver injury, inflammation, and fibrosis.

Fig. 8. Complex roles of iNKT cells in acute and chronic liver injury, inflammation, and fibrosis induced by CCl4.

Acute injection of CCl4 induces hepatocyte necrosis/apoptosis. Damaged hepatocytes release lipid antigens, which can be presented by HSCs via CD1d to iNKT cells, resulting in natural activation of iNKT cells. Liver injury also induces HSC activation. Activated HSCs produce a variety of proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α to participate in liver inflammation. Naturally activated iNKT cells may attenuate the proinflammatory effects of HSCs via inhibition of HSC activation or killing of HSCs. A single injection of α-GalCer induces strong iNKT cell activation and accelerates liver injury, inflammation, and fibrosis via an IFN-γ/STAT1-dependent mechanism. Chronic treatment with CCl4 leads to hepatic iNKT cell apoptosis and depletion. Thus, iNKT cells may play a role in inhibiting liver fibrosis at the early stage but not at the later stage. Repeated α-GalCer treatment leads to iNKT cell anergy and has little effect in chronic liver injury and fibrosis.

Natural activation of iNKT cells inhibits, while strong activation of iNKT cells by α-GalCer accelerates CCl4-induced acute liver injury and inflammation

Although Jα18-/- mice are resistant to Concanavalin A- and α-GalCer-induced acute liver injury and inflammation;17-19 we showed here that Jα18-/- mice were more susceptible to CCl4-induced liver injury and inflammation compared with wild-type mice. This suggests that natural activation of iNKT cells plays an anti-inflammatory role in the CCl4-induced liver injury. In contrast, strong activation of iNKT by α-GalCer markedly accelerated CCl4-induced acute liver injury. Reasons for the existence of opposing roles by naturally activated iNKT and the strongly activated iNKT by α-GalCer in CCl4-induced liver injury is not fully understood. We speculate that natural activation of iNKT after CCl4 treatment occurs locally and weakly in the liver, thereby inhibiting inflammation, while in contrast, α-GalCer-mediated iNKT activation is systemic and strong, resulting in the stimulation of inflammatory responses.

As shown in Fig. 1, expression of CD69, an activation marker, is elevated on liver NKT cells after CCl4 treatment, suggesting that iNKT cells in the liver are activated during CCl4-induced acute liver injury. Additionally, the fact that the number of hepatic iNKT cells decreased after acute CCl4 injection also indirectly suggests activation of iNKT cells because iNKT cells die after activation (a typical activation-induced death).32, 33 Moreover, serum levels of IFN-γ (a major cytokine produced by activated iNKT cells) were elevated only slightly after CCl4 injection (data not shown), indicating that iNKT cell activation after CCl4 treatment may occur weakly in the liver. Moreover, the number of infiltrated neutrophils was significantly higher after acute CCl4 treatment in Jα18-/- mice than in wild-type mice. Taken together, these findings suggest that iNKT cells are activated and play an important role in inhibiting neutrophil infiltration in acute CCl4-induced liver injury. Interestingly, the anti-neutrophil inflammatory response of iNKT cells was also recently reported in another mouse model of cholestatic liver injury.34 However, the mechanisms by which iNKT is naturally activated post CCl4 injection and contributes to antiinflammatory effects are not clear. It has been reported that HSCs are liver-resident antigen-presenting cells that can present lipid antigens to induce iNKT cell activation.35 Thus, hepatic iNKT activation could be caused by HSC presenting lipid antigens released from damaged hepatocytes post CCl4 treatment. Furthermore, we provide evidence suggesting that the antiinflammatory effect of natural activation of iNKT after CCl4 injection is mediated, at least in part, via inhibition of HSC activation. First, HSCs from Jα18-/- mice produce greater TNF-α and IL-6 than wild-type mice during CCl4-induced liver injury, suggesting that iNKT deficiency increases the proinflammatory effect of HSCs. Second, in vitro cytotoxicity assays showed that iNKT cells can directly kill early-activated HSCs, but not quiescent HSCs via an NKG2D-dependent mechanism, similar to NK cell killing of activated HSCs.7 Third, iNKT cells may inhibit HSC activation via production of IFN-γ, a cytokine has been shown to inhibit HSC proliferation and activation.30, 36 Lastly, activated HSCs have been shown to participate in liver inflammation.4, 37, 38

In contrast to weak natural iNKT cell activation, injection of α-GalCer caused strong and systemic iNKT activation as evidenced by markedly elevated serum cytokines including IFN-γ (Fig. 4). Further studies suggest that elevation of IFN-γ contributes to α-GalCer acceleration of CCl4-induced acute liver injury because the acceleration was completely abolished in IFN-γ-/- mice. Since IFN-γ is able to induce hepatocyte apoptosis via an STAT1-dependent mechanism,39 thus it is plausible that IFN-γ production after α-GalCer treatment can increase the susceptibility of hepatocyte apoptosis during CCl4-induced liver injury. Indeed, the number of apoptotic hepatocytes was much greater in α-GalCer plus CCl4 group than in the group treated with CCl4 alone.

iNKT cells are depleted and play a minor role in CCl4-induced chronic liver injury and inflammation

Although CCl4-induced acute liver injury was accelerated in Jα18-/- mice compared with wild-type mice, CCl4-induced chronic liver injury and inflammation were comparable between these 2 groups, suggesting that iNKT cells play a minor role in chronic liver injury in this model. This may occur because hepatic iNKT cells were depleted during chronic CCl4 treatment. The mechanism underlying iNKT cell depletion during CCl4-induced liver injury remains obscure. It was reported that endoplasmic reticulum stress decreases CD1d protein expression on hepatocytes, resulting in downregulation of NKT cells in murine fatty livers.40 Thus, the endoplasmic reticulum stress caused by CCl4 injection may also contribute to hepatic NKT cell depletion during CCl4-induced liver injury. Moreover, depletion of hepatic NKT cells was also observed in a variety of liver injury models induced by Concanavalin A, poly I:C, α-GalCer etc, 17-19 which may be caused by either activation-induced NKT cell death or loss of cell markers such as NK1.1, or a combination of both mechanisms.32, 33 Three lines of evidence from our studies suggest that depletion of hepatic iNKT cells after CCl4 is mainly mediated via activation-induced NKT cell death. First, the number of apopotic NKT cells in the liver was significantly increased after acute and chronic CCl4 treatment. Second, depletion of NKT cells was observed in both analyses using NK.1.1/CD3 markers and CD1 tetramer marker. Third, expression of Vα14 mRNA, a marker of iNKT cells, was downregulated after CCl4 treatment (data not shown).

Diverse roles of iNKT cells in liver fibrosis

In contrast to NK cells that has been shown to play an important role in inhibiting liver fibrosis,7-10 iNKT cells play a less important role in regulating liver fibrosis because of iNKT cell depletion and tolerance. As shown in Fig. 5, chronic CCl4 treatment caused marked depletion of hepatic iNKT cells. Thus chronic CCl4-treated wild-type mice were very similar to Jα18-/- mice, whereby iNKT cells in the liver were depleted in both groups. This may also explain why chronic CCl4 treatment only induced slightly greater liver fibrosis in Jα18-/- mice than in wild-type mice at early stage (2-week treatment) but not later stage (4-week treatment) although NKT cells are able to kill HSCs. In contrast to iNKT cell depletion, the total number of NK cells was not decreased, but rather increased after CCl4 treatment (Figs. 1C and 5B). The cytotoxicity of hepatic NK cells against activated HSCs was also increased after 2 week-CCl4 treatment (Jeong, Park, Gao.: unpublished data). These findings suggest that NK cells could compensate the depletion of iNKT to inhibit liver fibrosis during chronic CCl4 treatment.

Chronic treatment with the NK cell activator, poly I:C, markedly inhibited liver fibrosis as demonstrated previously,7, 9, 41 while chronic treatment with the iNKT activator, α-GalCer, had little effect on chronic liver injury and fibrosis (Fig. 7). The obvious reason for the unresponsiveness of α-GalCer in this model is due to the lack of hepatic iNKT cells during CCl4-induced chronic liver injury. An additional mechanism is likely, due to long-term iNKT cell anergy and tolerance after α-GalCer stimulation.42, 43 Interestingly, in contrast to α-GalCer, a naturally occurring glycolipid, β-glucosylceramide, has been shown to ameliorate liver fibrosis via modulation of NKT and CD8 lymphocyte distribution.44 However, it is not clear whether repeated β-glucosylceramide treatment also causes iNKT cell anergy.

Activation of iNKT cells by α-GalCer has been shown to induce rapidly NK cell activation, NK cell production of IFN-γ, and enhance the anti-tumor activity of NK cells.45, 46 Thus, it is plausible that iNKT cell activation could inhibit liver fibrosis via activation of the anti-fibrogenic effect of NK cells in addition to direct killing of HSCs and production of IFN-γ. However, activation of iNKT cells by a single dose of α-GalCer injection did not inhibit, rather enhanced CCl4-induced acute liver fibrosis although such injection elevated serum IFN-γ levels and enhanced iNKT cell killing of activated HSCs (Fig. 3E). Since a single dose of α-GalCer markedly enhanced CCl4-induced liver injury, we speculated that α-GalCer injection may inhibit liver fibrosis via production of IFN-γ and induction of iNKT cell killing of HSCs, but may also accelerate liver fibrosis via increasing liver injury. Acceleration of liver fibrosis by increased liver injury may dominate over the inhibitory effect of α-GalCer on liver fibrosis, leading to stimulatory effects of a single α-GalCer injection on liver fibrosis induced by acute CCl4 treatment.

In summary, our findings suggest that iNKT cells may play a protective or detrimental role in CCl4-induced acute liver injury depending on the degree of iNKT cell activation. During chronic liver injury, iNKT cells are depleted, playing a role in inhibiting the early stage but not late stage of liver fibrosis. The roles of iNKT cells in human liver injury and fibrosis remain unknown. de Lallat et al.47 reported that iNKT cells increase in chronically infected livers and produce profibrotic cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13, suggesting that iNKT cells may contribute to the progression of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B viral infection.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- iNKT

invariant NKT cells

- HSC

hepatic stellate cell

- MNC

mononuclear cells

- CCl4

carbon tetrachloride

- α-Galcer

α-galactosylceramide

References

- 1.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iredale JP. Models of liver fibrosis: exploring the dynamic nature of inflammation and repair in a solid organ. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:539–548. doi: 10.1172/JCI30542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman SL, Rockey DC, Bissell DM. Hepatic fibrosis 2006: report of the Third AASLD Single Topic Conference. Hepatology. 2007;45:242–249. doi: 10.1002/hep.21459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells: protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:125–172. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safadi R, Ohta M, Alvarez CE, Fiel MI, Bansal M, Mehal WZ, et al. Immune stimulation of hepatic fibrogenesis by CD8 cells and attenuation by transgenic interleukin-10 from hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:870–882. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radaeva S, Sun R, Jaruga B, Nguyen VT, Tian Z, Gao B. Natural killer cells ameliorate liver fibrosis by killing activated stellate cells in NKG2D-dependent and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-dependent manners. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:435–452. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melhem A, Muhanna N, Bishara A, Alvarez CE, Ilan Y, Bishara T, et al. Antifibrotic activity of NK cells in experimental liver injury through killing of activated HSC. J Hepatol. 2006;45:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krizhanovsky V, Yon M, Dickins RA, Hearn S, Simon J, Miething C, et al. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell. 2008;134:657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muhanna N, Doron S, Wald O, Horani A, Eid A, Pappo O, et al. Activation of hepatic stellate cells after phagocytosis of lymphocytes: A novel pathway of fibrogenesis. Hepatology. 2008;48:963–977. doi: 10.1002/hep.22413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kronenberg M. Toward an understanding of NKT cell biology: progress and paradoxes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:877–900. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seino K, Taniguchi M. Functionally distinct NKT cell subsets and subtypes. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1623–1626. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao B, J W, Tian Z. Liver: an organ with predominant innate immunity. Hepatology. 2008;47:729–736. doi: 10.1002/hep.22034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Exley MA, Koziel MJ. To be or not to be NKT: natural killer T cells in the liver. Hepatology. 2004;40:1033–1040. doi: 10.1002/hep.20433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emoto M, Kaufmann SH. Liver NKT cells: an account of heterogeneity. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:364–369. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ajuebor MN. Role of NKT cells in the digestive system. I. Invariant NKT cells and liver diseases: is there strength in numbers? Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G651–656. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00298.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dennert G, Aswad F. The role of NKT cells in animal models of autoimmune hepatitis. Crit Rev Immunol. 2006;26:453–473. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v26.i5.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halder RC, Aguilera C, Maricic I, Kumar V. Type II NKT cell-mediated anergy induction in type I NKT cells prevents inflammatory liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2302–2312. doi: 10.1172/JCI31602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biburger M, Tiegs G. Alpha-galactosylceramide-induced liver injury in mice is mediated by TNF-alpha but independent of Kupffer cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:1540–1550. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmad A, Alvarez F. Role of NK and NKT cells in the immunopathogenesis of HCV-induced hepatitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:743–759. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0304197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong Z, Zhang J, Sun R, Wei H, Tian Z. Impairment of liver regeneration correlates with activated hepatic NKT cells in HBV transgenic mice. Hepatology. 2007;45:1400–1412. doi: 10.1002/hep.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minagawa M, Deng Q, Liu ZX, Tsukamoto H, Dennert G. Activated natural killer T cells induce liver injury by Fas and tumor necrosis factor-alpha during alcohol consumption. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1387–1399. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chuang YH, Lian ZX, Yang GX, Shu SA, Moritoki Y, Ridgway WM, et al. Natural killer T cells exacerbate liver injury in a transforming growth factor beta receptor II dominant-negative mouse model of primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2008;47:571–580. doi: 10.1002/hep.22052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kita H, Naidenko OV, Kronenberg M, Ansari AA, Rogers P, He XS, et al. Quantitation and phenotypic analysis of natural killer T cells in primary biliary cirrhosis using a human CD1d tetramer. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1031–1043. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kahraman A, Barreyro FJ, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Mott JL, Akazawa Y, et al. TRAIL mediates liver injury by the innate immune system in the bile duct-ligated mouse. Hepatology. 2008;47:1317–1330. doi: 10.1002/hep.22136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masson MJ, Carpenter LD, Graf ML, Pohl LR. Pathogenic role of natural killer T and natural killer cells in acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice is dependent on the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide. Hepatology. 2008;48:889–897. doi: 10.1002/hep.22400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu ZX, Govindarajan S, Kaplowitz N. Innate immune system plays a critical role in determining the progression and severity of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1760–1774. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Notas G, Kisseleva T, Brenner D. NK and NKT cells in liver injury and fibrosis. Clinical Immunology. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.08.008. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cui J, Shin T, Kawano T, Sato H, Kondo E, Toura I, et al. Requirement for Valpha14 NKT cells in IL-12-mediated rejection of tumors. Science. 1997;278:1623–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeong WI, Park O, Radaeva S, Gao B. STAT1 inhibits liver fibrosis in mice by inhibiting stellate cell proliferation and stimulating NK cell cytotoxicity. Hepatology. 2006;44:1441–1451. doi: 10.1002/hep.21419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daley JM, Thomay AA, Connolly MD, Reichner JS, Albina JE. Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:64–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hobbs JA, Cho S, Roberts TJ, Sriram V, Zhang J, Xu M, et al. Selective loss of natural killer T cells by apoptosis following infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J Virol. 2001;75:10746–10754. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10746-10754.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harada M, Seino KI, Wakao H, Sakata S, Ishizuka Y, Ito T, et al. Down-regulation of the invariant Valpha14 antigen receptor in NKT cells upon activation. Int Immunol. 2004;16:241–247. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wintermeyer P, Cheng C, Gehring S, Hoffman B, Holub, Brossay L, Gregory S. Invariant natrual killer T cells suppresses the neutrophil inflammatory response in a mouse model of cholestatic liver damage. Gastroenterology. 2008 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.027. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winau F, Hegasy G, Weiskirchen R, Weber S, Cassan C, Sieling PA, et al. Ito cells are liver-resident antigen-presenting cells for activating T cell responses. Immunity. 2007;26:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rockey DC, Chung JJ. Interferon gamma inhibits lipocyte activation and extracellular matrix mRNA expression during experimental liver injury: implications for treatment of hepatic fibrosis. J Investig Med. 1994;42:660–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lang A, Sakhnini E, Fidder HH, Maor Y, Bar-Meir S, Chowers Y. Somatostatin inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion from rat hepatic stellate cells. Liver Int. 2005;25:808–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marra F. Hepatic stellate cells and the regulation of liver inflammation. J Hepatol. 1999;31:1120–1130. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun R, Park O, Horiguchi N, Kulkarni S, Jeong WI, Sun HY, et al. STAT1 contributes to dsRNA inhibition of liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology. 2006;44:955–966. doi: 10.1002/hep.21344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang L, Jhaveri R, Huang J, Qi Y, Diehl AM. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, hepatocyte CD1d and NKT cell abnormalities in murine fatty livers. Lab Invest. 2007;87:927–937. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeong WI, Park O, Gao B. Abrogation of the antifibrotic effects of natural killer cells/interferon-gamma contributes to alcohol acceleration of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:248–258. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biburger M, Tiegs G. Activation-induced NKT cell hyporesponsiveness protects from alpha-galactosylceramide hepatitis and is independent of active transregulatory factors. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:264–279. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parekh VV, Wilson MT, Olivares-Villagomez D, Singh AK, Wu L, Wang CR, et al. Glycolipid antigen induces long-term natural killer T cell anergy in mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2572–2583. doi: 10.1172/JCI24762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Safadi R, Zigmond E, Pappo O, Shalev Z, Ilan Y. Amelioration of hepatic fibrosis via beta-glucosylceramide-mediated immune modulation is associated with altered CD8 and NKT lymphocyte distribution. Int Immunol. 2007;19:1021–1029. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carnaud C, Lee D, Donnars O, Park SH, Beavis A, Koezuka Y, et al. Cutting edge: Cross-talk between cells of the innate immune system: NKT cells rapidly activate NK cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:4647–4650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayakawa Y, Takeda K, Yagita H, Kakuta S, Iwakura Y, Van Kaer L, et al. Critical contribution of IFN-gamma and NK cells, but not perforin-mediated cytotoxicity, to anti-metastatic effect of alpha-galactosylceramide. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1720–1727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Lalla C, Galli G, Aldrighetti L, Romeo R, Mariani M, Monno A, et al. Production of profibrotic cytokines by invariant NKT cells characterizes cirrhosis progression in chronic viral hepatitis. J Immunol. 2004;173:1417–1425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.