Abstract

In vivo 31P-NMR analyses showed that the phosphate (Pi) concentration in the cytosol of sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus) and Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) cells was much lower than the cytoplasmic Pi concentrations usually considered (60–80 μm instead of >1 mm) and that it dropped very rapidly following the onset of Pi starvation. The Pi efflux from the vacuole was insufficient to compensate for the absence of external Pi supply, suggesting that the drop of cytosolic Pi might be the first endogenous signal triggering the Pi starvation rescue metabolism. Successive short sequences of Pi supply and deprivation showed that added Pi transiently accumulated in the cytosol, then in the stroma and matrix of organelles bounded by two membranes (plastids and mitochondria, respectively), and subsequently in the vacuole. The Pi analog methylphosphonate (MeP) was used to analyze Pi exchanges across the tonoplast. MeP incorporated into cells via the Pi carrier of the plasma membrane; it accumulated massively in the cytosol and prevented Pi efflux from the vacuole. This blocking of vacuolar Pi efflux was confirmed by in vitro assays with purified vacuoles. Subsequent incorporation of Pi into the cells triggered a massive transfer of MeP from the cytosol to the vacuole. Mechanisms for Pi exchanges across the tonoplast are discussed in the light of the low cytosolic Pi level, the cell response to Pi starvation, and the Pi/MeP interactive effects.

Phosphorus, a key constituent of nucleic acids and membrane phospholipids, is an essential element for energy-mediated metabolic processes in all living organisms. In plants, the acquisition of phosphate (Pi), the size of endogenous Pi pools, and the exchange of Pi between different cell compartments have been the major focus of a great number of studies (for review, see Bieleski, 1973; Schachtman et al., 1998; Raghothama, 1999; Drobny et al., 2003; Raghothama and Karthikeyan, 2005). In particular, the concentration and homeostasis of cytoplasmic Pi (cyt-Pi) are considered as crucial for signal transduction pathways and for the regulation of many enzymes (Mimura, 1999; Poirier and Bucher, 2002). For example, Pi concentration in plastids regulates starch synthesis, phosphorylated carbohydrate metabolism, and photosynthesis (Plaxton and Carswell, 1999).

Phosphorous acquisition by plants often fluctuates because this essential nutrient is one of the least available in the soil (Barber et al., 1963). After a prolonged Pi deprivation, cyt-Pi decreases strongly (Gout et al., 2001). In this case, photosynthesis and carbon fixation are severely affected (for review, see Natr, 1992), but not respiration due to the high affinity of mitochondria for Pi (Rébeillé et al., 1984) and to the induction of alternative pathways of glycolysis and mitochondrial electron transport (Theodorou and Plaxton, 1993). On the other hand, cyt-Pi homeostasis is expected to be tightly regulated (Raghothama, 1999). Indeed, during short-term Pi starvation, cyt-Pi level is assumed to be maintained relatively constant at the expense of vacuolar Pi (vac-Pi; Bieleski, 1973; Rébeillé et al., 1983; Tu et al., 1990; Mimura et al., 1996), leaving nucleoside triphosphate content unaffected in maize (Zea mays) roots (Lee and Ratcliffe, 1993). However, early changes are observed in the phospholipids of Pi-starved Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) cells (Jouhet et al., 2003), suggesting the existence of an early Pi deprivation signal. In addition, the supply of tissues with substrates efficiently phosphorylated in the cytoplasm, like d-Man (Loughman et al., 1989), glycerol (Aubert et al., 1994), and choline (Bligny et al., 1989), triggers a decrease of hexose phosphates. These data suggested the existence of a cyt-Pi pool able to rapidly fluctuate according to the Pi supply from external and vacuolar stores and to the Pi demand for metabolism. As the Pi concentration of mitochondria and plastids is tightly regulated (Scarpa, 1979; Plaxton and Carswell, 1999), we hypothesized that the appearance of early Pi deprivation effects correlated with low Pi supply may originate from rapid Pi changes in cytosol.

In this paper, we term cytosol (cytsol) as the cell compartment exterior to the vacuole and organelles bounded by a double membrane (mitochondria and plastids, here called orgmp). Accordingly, the cytsol-Pi regulation is achieved by a combination of Pi transport across plasma membrane, orgmp membranes, and vacuolar membrane (tonoplast) and Pi-related metabolism. To date, only a few publications investigating in vivo Pi transport across the tonoplast have been published, and in none of them was the cytsol-Pi directly measured. This is addressed in this study using in vivo 31P-NMR.

For many years, 31P-NMR has permitted the noninvasive measurement of cyt- and vac-Pi pools (Rébeillé et al., 1983). However, until now, it was not possible to discriminate between cytsol- and orgmp-Pi signals, despite the more alkaline pHs of chloroplasts (ΔpH approximately 0.1–0.2 in the dark; Heldt, 1979) and mitochondria (ΔpH approximately 0.2–0.3; Neuburger and Douce, 1980), because the natural heterogeneity of plant tissues broadens Pi signals, thus favoring overlaps. In spinach (Spinacia oleracea) leaves, for example, we previously hypothesized that the cytsol-Pi signal was swamped by the chloroplast Pi signal (Bligny et al., 1990). In this study, we worked on culture cells first to improve sample homogeneity and second to finely adjust endogenous Pi level. Heterotrophic sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus) cells were most frequently used because they contain small amyloplastids instead of big chloroplasts, thus limiting the orgmp-Pi signal intensity. Finally, perfusion parameters were optimized to narrow the Pi signals. Together, these experimental conditions permitted us to discriminate, to our knowledge for the first time, between cytsol-Pi and orgmp-Pi pools.

To measure the fluctuations of endogenous Pi pools and analyze the movements of Pi across the tonoplast, we used Pi-starved cells containing less endogenous Pi stores and performed successive short sequences of Pi supply and starvation. We also used a Pi analog, methylphosphonate (MeP), which has several advantages: (1) it mimics Pi perception by plant cells but, unlike Pi, is not metabolized and is nontoxic in the short term (Couldwell et al., 2009); (2) its 31P-NMR signal displays a broad amplitude of pH-related shift with pKa at 7.5 (DeFronzo and Gillies, 1987), thus facilitating the discrimination between cytsol-MeP and orgmp-MeP pools (Lebrun-Garcia et al., 2002); and (3) its signals do not overlap with those of Pi and phosphorylated metabolites (Gout et al., 2001).

RESULTS

In Vivo Analysis of Inorganic Pi Pools in Sycamore and Arabidopsis Cells

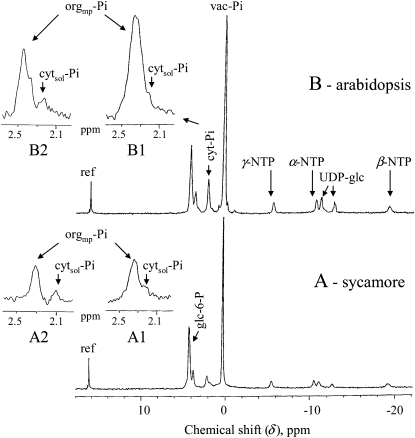

The 31P-NMR spectra from sycamore and Arabidopsis cells (Fig. 1) perfused with an oxygenated nutrient medium (NM) containing 50 μm Pi at pH 6.0 show two distinct signals at approximately 2.3 and 0.3 ppm, classically attributed to cyt- and vac-Pi, respectively (Roberts et al., 1980). Interestingly, enlarged portions of the spectra in the 2.0- to 2.6-ppm area show that the cyt-Pi peaks contain two signals that partially overlap at 2.35 and 2.20 ppm (insets A1 and B1). Since no significant signals corresponding to P-compounds are observed on cell extracts in this area (Aubert et al., 1996), it was concluded that these signals correspond to Pi pools at pH 7.55 and 7.40, respectively. A moderate acidification of the cytosol, by the addition to NM of 2 mm propionic acid at pH 6.4, shifted the 2.20-ppm signal to a lower value (inset A2), increasing the distance between the two signals. Reversely, the illumination of semiautotrophic Arabidopsis cells in the NMR tube, which triggers sugar phosphorylations in chloroplasts and alkalizes the stroma (Heber and Heldt, 1981), lowered and shifted the 2.35-ppm signal to approximately 2.5, thus improving the discrimination between these two signals (inset B2). Consequently, we hypothesized that the major signal (initially recorded at 2.35 ppm) corresponded to the Pi pool present in the slightly more alkaline stroma and matrix of plastids and mitochondria (orgmp-Pi) and the smaller signal (initially recorded at 2.20 ppm) to the Pi pool present in the cytosol (cytsol-Pi). In order to substantiate this hypothesis, we transiently supplied Pi-starved sycamore cells with Pi, expecting to fill successively cytsol and orgmp. Indeed, analysis of the spectra showed that, following the addition of 50 μm Pi in NM, a Pi signal appeared at 2.20 ppm (Fig. 2A). This signal disappeared after removing external Pi, whereas another Pi signal appeared symmetrically at 2.35 ppm (Fig. 2). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the signal at 2.20 ppm corresponds to cytsol-Pi, whereas the signal at 2.35 ppm corresponds to orgmp-Pi, thus permitting us to measure the size of these two Pi pools in sycamore and Arabidopsis cells (Table I). Assuming that the cytoplasm-to-cell ratio is 0.15 in these cells and that the volume of mitochondria plus plastids estimated from electron micrographs represents approximately 12% of the volume of cytoplasm in sycamore cells (Bligny and Douce, 1976) and 20% in Arabidopsis cells, it was calculated that the cytsol-Pi concentration was 60 to 80 μm and 55 to 75 μm in sycamore and Arabidopsis cells, respectively. The orgmp-Pi concentration was 4.0 to 4.4 mm in sycamore cells and 6.8 to 7.2 mm in Arabidopsis cells.

Figure 1.

In vivo proton-decoupled 31P-NMR spectra of sycamore (A) and Arabidopsis (B) culture cells. Experimental conditions were as follows. Cells cultivated in their respective culture medium supplied with Pi were harvested 5 d after subculture and placed in the NMR tube as described in “Materials and Methods.” They were perfused with a NM containing 50 μm Pi at pH 6.0 and 20°C. Insets show enlarged portions of full spectra centered on cyt-Pi: A1 and B1, standard perfusion conditions; A2, sycamore cells are acidified by the addition of 2 mm propionic acid to NM adjusted at pH 6.4; B2, Arabidopsis cells are illuminated as described in “Material and Methods.” Acquisition time was 1 h (6,000 scans). Peak assignments are as follows: ref, reference (methylenediphosphonate) used to measure chemical shifts and for quantifications; glc-6-P, Glc-6-P; cyt-Pi, cytoplasmic Pi; vac-Pi, vacuolar Pi; NTP, nucleoside triphosphate; UDP-glc, uridine-5′-diphosphate-α-d-Glc. orgmp-Pi and cytsol-Pi correspond to the cyt-Pi pools present in the stroma and matrix of plastids and mitochondria and in the cytosol (see text).

Figure 2.

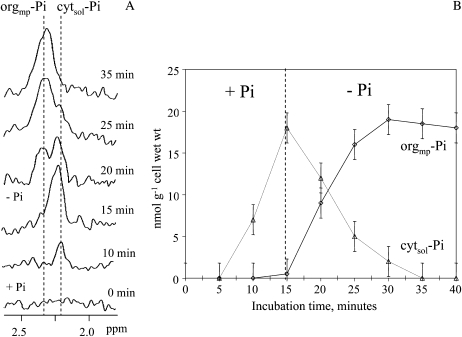

Rapid exchanges of Pi between the cytosol and the organelles (mitochondria and plastids) in Pi-starved sycamore cells transiently supplied with Pi. Experimental conditions were as follows. Prior to NMR analyses, cells were incubated over 5 d in a Pi-free NM in order to decrease Pi and P-compound pools below the threshold of in vivo 31P-NMR detection (approximately 20 nmol g−1). A, Portions of in vivo 31P-NMR spectra (expanded scale) showing the increase of the cytsol-Pi peak shortly after the addition of 50 μm Pi into NM and its decrease with the symmetrical orgmp-Pi increase upon rinsing cells with a Pi-free NM 15 min later. B, Corresponding curves showing the filling of cytosol after the addition of Pi to perfusion NM, and the symmetrical time course changes of cytsol-Pi and orgmp-Pi following the cell rinsing with a Pi-free NM. Acquisition time was 4.5 min (450 scans). Values are means ± sd (n = 10).

Table I.

Pi content (nmol g−1 cell wet weight) of the cytosol and of the stroma and matrix of plastids and mitochondria of sycamore and Arabidopsis cells

Experimental conditions were as follows. Cells were cultivated and harvested as indicated in the legend of Figure 1. Quantifications were performed from 31P-NMR in vivo spectra as indicated in “Materials and Methods.” Values are means ± sd (n = 10).

| Pi | Sycamore | Arabidopsis |

|---|---|---|

| cytsol-Pi | 9 ± 1 | 8 ± 1 |

| orgmp-Pi |

75 ± 5 |

210 ± 10 |

Besides the signals of endogenous Pi pools, other signals corresponding to Glc-6-P, nucleotide triphosphates (NTPs), and UDP-Glc were also observed (Fig. 1). The chemical shift of these signals confirms that these compounds are located in the cytoplasm; however, it was not possible to further specify their positions in either the cytosol or the organelles.

Time Course Changes of Pi and P-Compound Concentrations during Pi Starvation and Recovery

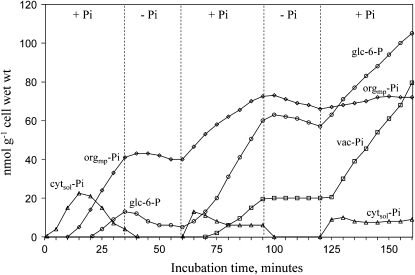

The kinetics curves shown in Figure 3 demonstrate, during successive short sequences of Pi supply/deprivation, that initially Pi-starved sycamore cells transiently accumulated Pi in the cytosol after each addition of Pi in NM. Following the first addition of Pi, cytsol-Pi increased rapidly, reaching approximately 22 nmol g−1 cell wet weight within 15 min, and decreased afterward. NTP recovered an average concentration of 85 to 95 nmol g−1 cell wet weight (data not shown), and orgmp-Pi and Glc-6-P started accumulating. During subsequent Pi supply/deprivation sequences, the overshoot of cytsol-Pi was less pronounced and cytsol-Pi stabilized at about 9 nmol g−1 cell wet weight, which was the concentration measured in cells cultivated on Pi-containing NM. Pi started to accumulate into the vacuole after nearly 45 min of cell incubation in the presence of Pi. Every time cells were rinsed with a Pi-free NM, the cytsol-Pi signal became undetectable in the in vivo 31P-NMR spectra, whereas orgmp-Pi decreased only slightly. Since in our experimental conditions the Pi detection threshold was approximately 20 nmol of Pi and the analyzed cell volume was 10 mL, one can calculate that under Pi-deprived sequences, cytsol-Pi concentration dropped below 15 μm. The decrease of Glc-6-P during the Pi deprivation sequences was assumed to correspond to Pi-related metabolic activities such as the synthesis of NTPs, nucleic acids, or phospholipids. After initiation of vacuole refilling, vac-Pi did not significantly decrease during these short Pi deprivations.

Figure 3.

Time-course evolution of the pools of Pi and Glc-6-P in sycamore cells during successive short sequences of Pi supply and starvation. Experimental conditions were as follows. Prior to NMR analyses, cells were incubated as indicated in the legend of Figure 2. At time zero, 50 μm Pi was added to NM. Afterward, cells were perfused alternatively with a Pi-free or with a Pi-supplied NM as indicated. Acquisition time was 4.5 min (450 scans). Abbreviations are as in Figure 1. This experiment was repeated five times. For the sake of readability, values are not given as means ± sd but are from one representative experiment.

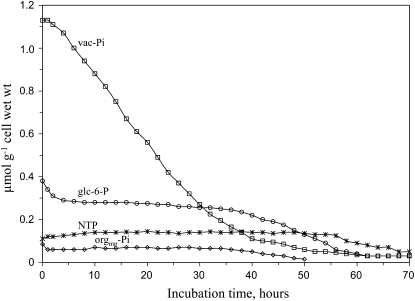

Over the long term, however, when standard (Pi-supplied) sycamore cells were perfused with a Pi-free medium, vac-Pi appeared to decrease steadily. Interestingly, after a limited initial decrease, the pools of orgmp-Pi and Glc-6-P remained stable despite the drop of cytsol-Pi below the threshold for 31P-NMR detection (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the cell NTP concentration did not change as long as vacuole contained detectable amounts of Pi (about 2 d). Since no efflux of Pi in the perfusing medium was detected, it was concluded that vac-Pi was utilized to sustain cell growth, which did not stop immediately after the beginning of the Pi starvation. When vac-Pi was exhausted, orgmp-Pi and P-compound pools including NTP started decreasing (Fig. 4). These observations confirm the role of vac-Pi as an endogenous Pi pool sustaining cell metabolism during the first days of Pi starvation. They also highlight the importance of the vac-Pi efflux to sustain the homeostasis of P-compounds in plant cells. To further analyze the exchanges of Pi between cytosol and vacuole, we incubated cells in the presence of the Pi analog MeP.

Figure 4.

Time-course evolution of the pools of Pi, NTP, and Glc-6-P in sycamore cells following the onset of Pi starvation. Experimental conditions were as follows. Standard cells harvested 5 d after subculture were used. Cells were analyzed by in vivo 31P-NMR as described in the legend of Figure 1. At time zero, cells were perfused with a Pi-free NM. Acquisition time was 2 h (12,000 scans). Abbreviations are the same as in Figure 1. Values are from a representative experiment chosen among five.

Incorporation of MeP to Plant Cells

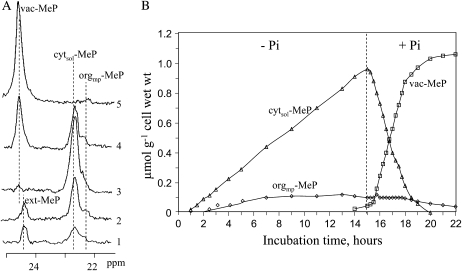

MeP incorporation in Pi-starved sycamore cells is shown in Figure 5. At time zero, 200 μm MeP was added in the Pi-free NM at pH 6.0, giving rise to a MeP signal (ext-MeP) at 24.4 ppm. One hour later, a second signal appeared at 22.7 ppm, and a third signal appeared at 22.3 ppm after 2.5 h of incubation (spectrum 1). By reference to a MeP pH-dependent calibration curve, these two signals were attributed to MeP pools at pH 7.40 and 7.55, respectively (note that MeP and Pi signals shift in opposite directions according to pH). For the same reasons given above to discriminate between cyt-Pi pools, the signals at 22.7 and 22.3 ppm were attributed to cytsol-MeP and orgmp-MeP, respectively. After 15 h of incubation, cells were rinsed with a MeP-free perfusion medium, revealing the presence of a small signal at 24.6 ppm that was overlapped by ext-MeP (spectrum 3). This signal corresponded to a MeP pool at pH 5.0 and was thus attributed to vacuolar MeP (vac-MeP). However, it remained negligible compared with the signal of cytsol-MeP even after longer incubation times (1–2 d; data not shown). Whereas cytsol-MeP increased steadily, reaching 1.0 ± 0.1 μmol g−1 cell after 15 h of incubation, orgmp-MeP reached only 0.1 ± 0.01 μmol g−1 cell after 8 to 10 h and remained stable (Fig. 5B; Table II). Assuming the relative volume of different cell compartments as described above, it was calculated that cytsol-MeP and orgmp-MeP concentrations were about 7.6 and 5.6 mm, respectively, after 15 h of cell incubation with MeP. These intracellular MeP concentrations, therefore, were largely higher than the ext-MeP concentration. When the maximal rates of MeP uptake by Pi-starved cells (i.e. the rate of cytsol-MeP plus orgmp-MeP accumulation) are presented as a double-reciprocal plot, then Michaelis-Menten kinetics are observed (Supplemental Fig. S1A). For five experiments carried out at pH 6.0 and 20°C, the apparent Km for MeP uptake was 130 ± 15 μm and the Vmax was 80 ± 8 nmol MeP incorporated h−1 g−1 cell wet weight. Supplemental Figure S1 also shows both that Pi exhibited a strong competitive inhibition on MeP uptake (Ki = 4 ± 0.5 μm; A) and that the pH dependence of MeP uptake had an optimum at about pH 5 (B), very similar to that of Pi. Finally, the Vmax for MeP uptake by Pi-starved cells was higher than that of nonstarved cells (80 ± 6 versus 35 ± 3 nmol h−1 g−1 cell wet weight), whereas the value of Km was the same (data not shown), indicating that in sycamore cells the MeP influx was enhanced by Pi starvation like that of Pi (Rébeillé et al., 1983).

Figure 5.

Exchanges of MeP between cytosol, organelles (mitochondria and plastids), and vacuole in sycamore cells. Experimental conditions were as follows. Prior to NMR analyses, cells were incubated as indicated in the legend of Figure 2. At time zero, 200 μm MeP was added in the Pi-free NM; at 15 h, cells were rinsed with a MeP-free NM and afterward perfused with a NM containing 50 μm Pi. A, Portions of in vivo 31P-NMR spectra (expanded scale) showing the signals corresponding to different MeP pools: spectra 1, 2, and 3 were assigned to times 1.5, 7 h, and 15 h after MeP addition (at the beginning of spectrum 3 acquisition, ext-MeP was rinsed); spectra 4 and 5 were assigned to times 1.5 and 4 h after subsequent cell perfusion with a MeP-free and Pi-supplied NM. B, Curves showing the filling of cytsol-MeP, orgmp-MeP, and vac-MeP pools during the incubation with MeP and the drop of cytsol-MeP and symmetrical increase of vac-MeP after the subsequent cell perfusion with the MeP-free and Pi-supplied NM. Acquisition time was 15 min (1,500 scans); note that variable delays separate acquisitions on the curves. ext-MeP, cytsol-MeP, orgmp-MeP, and vac-MeP represent MeP pools present in external medium, cytosol, organelles, and vacuole, respectively. Values are from a representative experiment chosen among five.

Table II.

Concentrations of MeP (μmol g−1 cell wet weight) in Pi-starved sycamore cells measured 15 h after the addition of 200 μm MeP and then 5 h after cell rinsing with a MeP-free NM supplied with 50 μm Pi

Experimental conditions were as follows. Cells were cultivated and harvested as indicated in the legend of Figure 5 (spectra 3 and 5). Quantifications were performed from 31P-NMR in vivo spectra as indicated in “Materials and Methods.” Values are means ± sd (n = 5). nd, Not detected (<40 nmol MeP in our experimental conditions).

| MeP | +MeP (15 h) | +Pi (5 h) |

|---|---|---|

| cytsol-MeP | 1.0 ± 0.1 | nd |

| orgmp-MeP | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| vac-MeP |

0.05 ± 0.01 |

1.1 ± 0.1 |

Inhibition of Vacuolar Pi Efflux by Cytosolic MeP

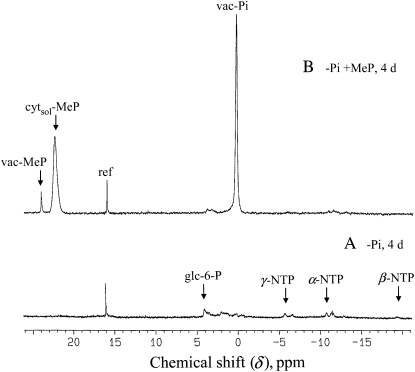

In the experiment described in Figure 6, control sycamore cells were incubated for 4 d in a Pi-free NM, either without (A) or with (B) 200 μm MeP. By comparison with the reference spectrum shown in Figure 1, both spectra displayed dramatic declines of cytoplasmic phosphorylated metabolites and cyt-Pi. However, a striking difference between the two spectra was observed: in the presence of MeP (spectrum B), the vac-Pi pool did not decrease, remaining similar to that of Pi-supplied cells (Fig. 1A). However, this sequestration of Pi in the vacuole had no effect on cell survival, as proved by the restarting of cell growth when Pi was added back to cell cultures. In fact, we observed that Pi-starved sycamore cells grown as described by Bligny and Leguay (1987) can survive during several weeks in the presence or not of MeP. Since the vac-MeP concentration remained low in this experiment, we hypothesized that cytsol-MeP inhibited the flux of Pi from the vacuole.

Figure 6.

In vivo proton-decoupled 31P-NMR spectra of sycamore cells incubated in a Pi-free NM containing or not containing MeP. Experimental conditions were as follows. Prior to NMR analyses, standard cells were incubated 4 d in a Pi-free NM (A) or in a Pi-free NM supplied with 200 μm MeP (B). During NMR acquisition, cells were perfused with a MeP-free NM at pH 6.0. Acquisition time was 1 h (6,000 scans). Abbreviations are the same as in Figures 1 and 5. This experiment was repeated with various incubation times (data not shown), showing that in the presence of MeP vac-Pi remained stable, contrary to what was observed in the absence of MeP, where it became undetectable after 2 d, and P-compounds became hardly detectable after only 1 d of incubation.

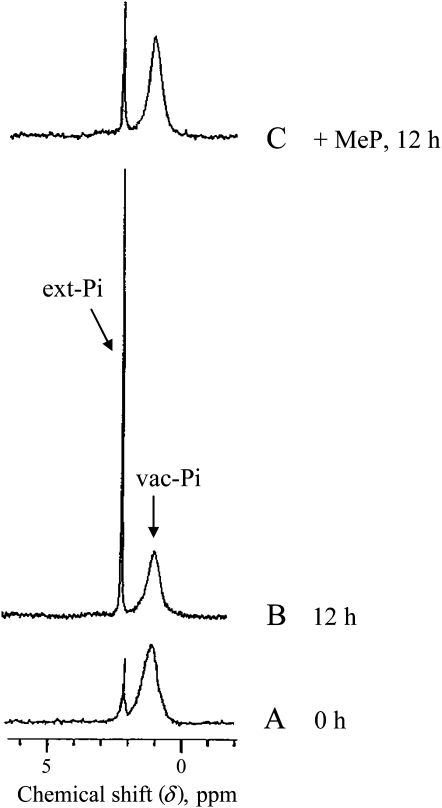

The inhibition of vac-Pi efflux by MeP was confirmed by experiments carried out with isolated vacuoles prepared from standard Pi-supplied cells as described in “Materials and Methods.” The NMR spectra of vacuoles suspended in buffer A adjusted to pH 7.5 show a broad signal centered at 1.2 ppm (Fig. 7A). This signal corresponded to a Pi pool at around pH 6.2 and was attributed to the Pi sequestered in vacuoles. A minor signal at 2.3 ppm corresponded to a Pi pool at pH 7.5 and was attributed to the Pi released by vacuoles in the suspension medium during their purification. When the vacuoles were kept for 12 h at 20°C in buffer A, the vac-Pi signal decreased, whereas the signal corresponding to ext-Pi increased correspondingly (Fig. 7B), thus reflecting a flux of Pi from the vacuole into the external medium. The quantification of Pi pools indicated that nearly 20% of vac-Pi effluxed within 12 h. In contrast, when 1 mm MeP was added in buffer A, the efflux of Pi across tonoplast was lowered by a factor of 5 to 6 (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7.

Proton-decoupled 31P-NMR spectra showing the efflux of Pi from isolated sycamore cell vacuoles. Vacuoles were isolated from standard cells as indicated in “Materials and Methods.” Experimental conditions were as follows. For each condition, 0.5 mL of the thick purified vacuole suspension was diluted in 1.5 mL of buffer A adjusted to pH 7.5. Each sample (2 mL) was analyzed using 10-mm NMR tubes and a 10-mm probe. Acquisition time was 1 h (1,000 scans). A, Freshly prepared vacuoles (time zero). B, Vacuoles kept for 12 h in buffer A. C, Vacuoles kept for 12 h in buffer A containing 1 mm MeP. This experiment was repeated three times.

The inhibition of vac-Pi efflux by cytsol-MeP, although having no effect on the survival of cells, sped up the physiological consequences of Pi deficiency (Table III). Indeed, when cells were incubated in a Pi-free NM containing MeP, the soluble P-compounds reached the limit of NMR detection much earlier than in the absence of MeP (data not shown). In addition, cell growth stopped almost immediately and the cell respiration decline observed after 2 to 3 d of Pi deprivation in the absence of MeP appeared after less than 1 d when MeP was added to Pi-free NM. In Arabidopsis cells, an arrest of photosynthesis activity was observed after 1 d of incubation with MeP (data not shown). These results indicate that the MeP-triggered sequestration of Pi in the vacuole accelerated the decrease of cell metabolism and growth.

Table III.

Time course of growth and respiration rates of sycamore cells incubated in a standard medium, a Pi-free medium, and a Pi-free + MeP nutrient medium

Standard sycamore cells were incubated at time zero in a standard NM, a Pi-free NM, and a Pi-free NM supplied with 200 μm MeP. Temperature of incubation was 20°C. Cell concentration of culture (expressed as mg cell wet weight mL−1) and cell respiration rate (expressed as μmol O2 consumed min−1 g−1 cell wet weight) were measured as indicated in “Materials and Methods.” Values are means ± sd (n = 5).

| Time | Cell Concentration |

Cell Respiration Rate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +Pi | −Pi | −Pi, +MeP | +Pi | −Pi | −Pi, +MeP | |

| 0 h | 10 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.02 |

| 24 h | 13 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 | 11 ± 1 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.30 ± 0.02 |

| 48 h | 18 ± 2 | 16 ± 2 | 12 ± 1 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.02 |

| 120 h |

40 ± 3 |

22 ± 2 |

12 ± 1 |

0.36 ± 0.02 |

0.30 ± 0.02 |

0.22 ± 0.02 |

Pi-Catalyzed Influx of MeP into Vacuoles

After the 15-h sequence of MeP incorporation into Pi-starved sycamore cells described above, cells were rinsed with MeP-free NM and 50 μm Pi was added to the perfusion medium. As expected, this resulted in the rapid influx of Pi into the cytosol, in the restoration of the pools of P-compounds, including hexose-P and NTPs, and in the influx of Pi into the vacuole (data not shown). Unexpectedly, however, this addition of Pi triggered a sharp and steady decline of cytsol-MeP and the symmetrical increase of vac-MeP (Fig. 5) until MeP became undetectable in the cytosol. The rate of MeP transfer to the vacuole reached 300 ± 30 nmol h−1 g−1 wet weight, higher than that of Pi (100 ± 10 nmol h−1 g−1 wet weight). In addition, the rate of MeP influx into the vacuole was found to be the same in nonstarved cells. These results suggest that the mechanisms of MeP uptake across tonoplast and plasma membrane are quite different. Finally, when cells containing 1 μmol MeP g−1 cell wet weight in the vacuole were rinsed with a Pi-free NM, an efflux of vac-MeP toward the cytosol was observed, which was not observed when cells were rinsed with a Pi-containing NM (data not shown). This indicates that cytsol-Pi inhibited vac-MeP efflux.

DISCUSSION

The first discovery presented in this report is that the concentration of Pi in the cytosol of Pi-supplied plant cells is very low (60–80 μm). In particular, the cytsol-Pi concentration was found to be much lower than that of orgmp-Pi (approximately 5 mm in sycamore cells). This result was obtained using an improved in vivo NMR technique giving, to our knowledge for the first time, the possibility to discriminate between the Pi pools present in the cytosol and in the more alkaline (ΔpH approximately 0.2) double membrane-surrounded organelles (plastids and mitochondria; Heldt, 1979; Neuburger and Douce, 1980). In sycamore cells, we found a 0.15-pH unit difference between cytsol and orgmp, which is slightly less than the above mentioned value. However, this might be due to the fact that most of the orgmp inner volume is that of mitochondrial matrix (Bligny and Douce, 1976) and that in cells mitochondria are not at state 4 but between state 3 and state 4, with a lower ΔpH across the mitochondrial inner membrane. The 60 to 80 μm cytsol-Pi concentration measured in this work is in contrast with the millimolar cyt-Pi concentrations measured in the literature (Lee et al., 1990; Mimura, 1999). In our opinion, one reason for such a large discrepancy is that the signals corresponding to cytsol-Pi and orgmp-Pi usually overlap on in vivo NMR spectra. As a matter of fact, in the mesophyll cells of mature spinach leaves, where the chloroplast constitutes more than 60% of cytoplasmic volume (Winter et al., 1994), it was not possible to identify cytsol-Pi (Bligny et al., 1990; this work). Under these conditions, assuming that orgmp-Pi concentration averages 5 mm in sycamore cells and more than 10 mm in green cells (Mourioux and Douce, 1981; Douce and Joyard, 1990) and that the volume of the organelles relative to the volume of the cytosol may vary between 10% and 70%, it is easy to demonstrate that the concentration of Pi in the cytoplasm should be in the millimolar range, as reported in the literature. In this case, the so-called cyt-Pi signal should mainly correspond to orgmp-Pi stores. Subsequently, the differences observed between the cyt-Pi concentrations (1–10 mm) reported in various plants (Rébeillé et al., 1983; Lee et al., 1990; Mimura, 1999; Gout et al., 2001) might be attributed to the variable relative volume occupied by plastid and mitochondria in the cytoplasm of plant cells. For example, in this work, we observed that the cyt-Pi pool of Arabidopsis cells that contain chloroplasts was nearly 3-fold greater than that of sycamore cells that contain small amyloplasts, even though the concentration of cytsol-Pi was equivalent in both species. Similarly, embryonic tissues like root tips containing a high density of mitochondria in their cells also display an important cyt-Pi signal (Lee et al., 1990).

Fluctuation of the Concentration of Pi in the Cytosol

The second discovery is that the cytsol-Pi concentration dropped below the threshold of 31P-NMR detection within minutes upon cell incubation in a Pi-free NM. Nevertheless, it is probable that cytsol-Pi equilibrated at a new lower concentration (below 15 μm) that depends both on vac-Pi efflux and on the cell demand for Pi. In support, after a limited initial decrease, orgmp-Pi concentration remained nearly constant over 2 d, whereas vac-Pi decreased steadily, thus temporarily sustaining cell metabolism and growth. The release of vac-Pi may thus appear as buffering the cyt-Pi concentration under low-Pi status, as pointed out by numerous reports and reviews (Bieleski, 1973; Lauer et al., 1989, Mimura et al., 1996; Mimura, 1999; Raghothama, 1999). On the contrary, when the vac-Pi efflux was blocked by MeP, then the concentration of orgmp-Pi and phosphorylated compounds such as Glc-6-P decreased faster, cell respiration decreased, and cell growth stopped.

After the addition of Pi to their NM, a transient overshoot of cytsol-Pi was observed in Pi-deprived cells, with a 200 μm peak attained within 15 min. During the following minutes, cytsol-Pi decreased, probably because it started to be metabolized. This initial overshoot weakened with time during the successive short sequences of Pi supply/deprivation, possibly because the synthesis of Pi-containing cell components and the filling of the vac-Pi pool restarted more rapidly than after the first addition of Pi, and finally cytsol-Pi concentration stabilized at about 60 μm.

These rapid fluctuations of cytsol-Pi concentration were hypothesized to have important physiological consequences, since cytosol plays a central role both in the incorporation of a number of nutrients to cells and in their dispatching in the different cell compartments. On the one hand, the low concentration of cytsol-Pi should facilitate the proton-coupled transport of Pi across the plasma membrane, which occurs against a concentration gradient much less important than the 1,000-fold or higher gradient usually admitted (Mimura, 1999; Raghothama, 1999; Poirier and Bucher, 2002). On the other hand, the steeper Pi gradient between the cytosol and the organelles would place a greater energetic demand on the transporters (McIntosh and Oliver, 1994; Douce et al., 1997; Flügge, 1999). At the level of the tonoplast, the situation analyzed here with the Pi analog MeP is more contrasted, depending on whether influx or efflux of Pi is considered.

Incorporation of MeP to Cells

Until now, the Pi transport across the tonoplast (into and out of the vacuole) has been mainly analyzed either in situ by measuring vac-Pi changes using 31P-NMR or in vitro with isolated vacuoles that permit the supply of substrates and facilitate the use of inhibitors. However, the mechanisms of Pi transfer across the tonoplast remain poorly understood. In this study, the utilization of MeP, which is not metabolized (Couldwell et al., 2009) and does not participate in cell energy metabolism, permitted us both to mimic Pi movements between the cytoplasmic and vacuolar compartments and to interfere in situ with Pi transport. Our results indicate that MeP is readily incorporated by plant cells, provided that either Pi is absent from the external medium or MeP is present in large excess, since the transport of MeP across plasmalemma was competitively inhibited by Pi. The rate of MeP incorporation into cells was about 4-fold lower than that of Pi. An acidic pH favors a maximal rate of uptake both for Pi and MeP, indicating that MeP transport is coupled to a proton symport process. These data altogether suggest that the MeP uptake through the plasma membrane was supported by a Pi carrier. Similar MeP/Pi and phosphite/Pi competitions have been reported in the yeast Candida utilis (Bourne, 1990) and in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) BY-2 cells (Danova-Alt et al., 2008), respectively.

Pi Influx into the Vacuole

The influx of Pi into the vacuole was observed when the cytosol of cells perfused with Pi-supplied NM contained about 50 μm Pi. Considering the H2PO4−/HPO42− pKa of 6.8, HPO42− predominates in the cytosol at pH 7.4 as the permeant Pi species involved in the influx of cytsol-Pi into the vacuole. Consequently, if we postulate, as Massonneau et al. (2000) did, that the electrochemical potential gradient across the tonoplast is the main driving force, the transported form of Pi should be HPO42−. In addition, the protonation of HPO42− into H2PO4− within the acidic vacuole tends to maximize vac-Pi accumulation. A vacuolar channel for Pi uptake, similar to that characterized in Beta vulgaris by Dunlop and Phung (1998), could be involved in sycamore cells. However, whereas the Pi uptake is enhanced in Pi-deficient plant materials (Rébeillé et al., 1983; Shimogawara and Usuda, 1995; Mimura, 1999; Rausch and Bucher, 2002), we did not detect any enhancement of Pi influx into the vacuole in Pi-deprived sycamore cells. This was also observed with MeP. Our results contrast with the activation, under low-Pi status, of Pi uptake into purified vacuoles of Catharanthus roseus culture cells (Ohnishi et al., 2007). This discrepancy may be due to the fact that the cytsol-Pi concentration is much lower than the concentration of Pi added to the vacuole suspension medium by the authors. As a matter of fact, when the cytosol was loaded with a high concentration of MeP (>5 mm), the rate of MeP influx into vacuole was 3-fold higher than that of Pi. From a physiological point of view, the absence of in situ-detected stimulation of Pi transport into the vacuole of Pi-starved cells is consistent with the cell's need for Pi in the cytoplasm.

In contrast to the situation found at the plasma membrane, where external Pi inhibits the uptake of MeP into the cell, we observed that cytosolic Pi is a strong activator of the transfer of MeP to the vacuole. Indeed, until Pi was added to the cell perfusion medium, MeP was only poorly transported inside the vacuole, as similarly observed for phosphite in tobacco BY-2 cells by Danova-Alt et al. (2008). However, whereas phosphite effluxes into the medium after Pi resupply in tobacco cells, we only observed a rapid influx of cytsol-MeP into the vacuole of sycamore cells in that case. A first hypothesis to explain the key role played by Pi in the transfer of MeP into the vacuole is that the vacuolar-type H+-ATPase and the H+-pyrophosphatase located in the tonoplast, which provide the driving force (Sze et al., 1999; Drobny et al., 2003), may be weaker after the cytsol-Pi drop triggered by Pi deprivation, particularly in the presence of MeP blocking vac-Pi release. However, H+ pumps remained active under low-Pi status, as shown by unchanged cytosolic and vacuolar pHs. A second hypothesis is that the putative channel for vac-Pi influx requires it to be phosphorylated to facilitate the transport of MeP, and probably Pi, into the vacuole. It is known, for example, that plant cells control the transport of water across their plasma membrane by regulating the channel opening of aquaporins either via the phosphorylation of Ser residues (Törnroth-Horsefield et al., 2006) or via the deprotonation of a His residue (Tournaire-Roux et al., 2003). Interestingly, we previously observed that, like water, Pi was not transferred into the vacuole of Arabidopsis root cells when anoxia inhibited phosphorylation and acidified the cytosol (Tournaire-Roux et al., 2003). In addition, the loss of cytosolic enzymes during vacuole preparation, such as protein kinases, could be the cause of the generally low Pi transport rates obtained when isolated vacuoles or tonoplast vesicles were used.

Pi Efflux from the Vacuole

In the vacuole at pH 5.0, the monoanion H2PO4− predominates as the permeant Pi species involved in the efflux of vac-Pi. In standard culture cells, its concentration is in the millimolar range. Inversely, H2PO4− represents only a small fraction of cytsol-Pi in the cytosol at pH 7.4, with a concentration close to 15 μm. In Pi-deprived cells, the rapid drop of cytsol-Pi still reduces the cytosolic H2PO4− concentration, thus facilitating the efflux of vac-Pi. Similarly, an efflux of Pi from isolated vacuoles was observed in a Pi-free suspension medium. The Pi analog MeP also effluxed from the vacuole of cells loaded with MeP. Taken together, these results suggest that Pi and its analogous MeP passively equilibrate across the tonoplast according to electrochemical gradients.

Currently, there is no information on the molecular mechanisms that mediate Pi efflux across the tonoplast. At this level, MeP acted as a potent inhibitor of Pi efflux from the vacuole both in vivo and in vitro, whereas the very low concentration of MeP in the vacuole where Pi was sequestered proves that there was no significant exchange between Pi and MeP across the tonoplast. To explain these unexpected data, we propose that H2PO4− might be passively transported out of the vacuole through a monovalent ion channel, the functioning of which is blocked by MeP present in cytosol (perhaps under its monoanionic form CH4PO3−, with pKa of 7.5). As the vac-Pi efflux was independent from the initial status of cells, standard or Pi deprived and partially refilled with Pi before Pi starvation experiments, we conclude that this putative Pi channel was unlikely to be overexpressed in the tonoplast of Pi-starved cells. Interestingly, cytsol-Pi blocked vac-MeP efflux, since MeP remained sequestered in vacuoles as long as NM contained Pi, whereas it effluxed when cells were incubated in a Pi-free medium. By analogy with MeP, this suggests that in Pi-supplied cells, cytsol-Pi could inhibit vac-Pi efflux, thus preventing a possible energy-consuming Pi efflux/influx cycle across the tonoplast.

CONCLUSION

Following the onset of Pi starvation, the Pi efflux from the vacuole is insufficient to compensate for a rapid decrease of the cytosolic Pi concentration. Consequently, the sudden drop of cytosolic Pi could be the first endogenous response to Pi starvation triggering a signal transduction pathway that activates the Pi starvation rescue metabolism. This cytsol-Pi drop also facilitates the efflux of Pi from the vacuole, whereas it would hardly be the case if the cytosolic Pi was maintained at a constant high level during short-term Pi starvation, as claimed by numerous authors (for review, see Mimura, 1999; Raghothama, 1999). On the contrary, the low cytsol-Pi concentration fluctuates rapidly according to cell Pi supply and metabolism. The use of MeP as a structural Pi analog contributed to show that, in addition to being a nutrient required for cell metabolism and signaling, Pi mediates its own transport across the tonoplast. Finally, our results emphasize the need for further research to identify the hypothesized H2PO4− and HPO42− channels of the tonoplast, particularly since no vac-Pi transporter has so far been characterized (Misson et al., 2005; Jaquinod et al., 2007). It would also be desirable to precisely delineate the temporal sequence of the cell response to cytsol-Pi drop. This includes the expression of Pi starvation signaling proteins (Fang et al., 2009), the expression of high-affinity Pi transporters (Muchhal and Raghothama, 1999), the replacement of phospholipids with lipids devoid of phosphorus (Dörmann and Benning, 2002; Jouhet et al., 2003), and more generally the expression (Stefanovic et al., 2007) and transcription (Misson et al., 2005; Tran and Plaxton, 2008) of numerous genes involved in Pi metabolism and associated with the Pi deficiency response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Heterotrophic sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus) cells and semiautotrophic Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; wild-type Columbia ecotype) cells were grown at 20°C in Lamport (1964) and Murashige and Skoog (1962) liquid NM, respectively, as described by Bligny and Leguay (1987). The Pi status of the different NM used is stated in the text and in the corresponding legends of figures and tables. The cell suspensions used were maintained in exponential growth by repeated subculture every 7 d. The cell wet weight was measured after filtration of culture aliquots onto a glass-fiber filter.

Isolation of Vacuoles

Protoplasts were prepared from standard sycamore cells (10 g) using a cocktail of enzymes as described by Pugin et al. (1986). The purification of vacuoles from protoplast contamination was carried out according to the method of Pugin et al. (1986), using a discontinuous gradient of Ficoll 400. The gradient was prepared in a solution containing 0.7 m mannitol, 2 mm MgCl2, 2 mm EDTA, and 25 mm MES/Tris adjusted to pH 7.5 (buffer A). After centrifugation at 150,000g for 1 h (Beckman 70 Ti rotor), liberated vacuoles were located at two different interfaces: “heavy vacuoles” and “light vacuoles” corresponding to bands at the 6/4 and 4/0 interface, respectively (the numbers refer to the percentage of Ficoll). The two vacuole populations were combined and washed with buffer A. Subsequent to a centrifugation step at 300g for 10 min, the vacuolar pellet was resuspended in a minimal volume of buffer A. The purified vacuoles represented about 50% of this suspension, and 1.5 to 2 mL of thick vacuole suspension was obtained at each preparation. The intactness of vacuoles was controlled with the microscope via their ability to concentrate neutral red.

NMR Spectroscopy

In vivo 31P-NMR spectra of suspension culture cells were recorded on a Bruker NMR spectrometer (AMX 400, wide bore; Bruker Instrument) equipped with a 25-mm multinuclear probe tuned at 161.9 MHz. Cells (10 g) were placed in a 25-mm NMR tube equipped with a perfusion system as described earlier (Aubert et al., 1996). In order to better separate the Pi resonance peaks corresponding to the Pi pools located in the cytosol and in the stroma of the slightly more alkaline (ΔpH approximately 0.1–0.2 in the dark) organelles (plastids and mitochondria), the perturbation of the magnetic field induced by the heterogeneity of plant samples was diminished. For this, cells were simply left to sediment on the filter placed at the bottom of the NMR tube and then perfused with a moderate NM flux (20 mL min−1). We checked that this perfusion flux was sufficient for a perfect oxygenation of all cells and that it avoided local compressions of packed cells and subsequent NM channeling. In addition, the concentration of macronutrients added to perfusion media (4 L) was diluted 4-fold to limit possible local elevations of temperature that might create losses of field homogeneity. Micronutrients, and in particular Mn2+, were not added to perfusion medium to improve signal-to-noise ratio. The deuterium resonance of 2H2O was used as a lock signal to adjust field homogeneity. For this, cells were initially perfused with 250 mL of NM containing 10 mL of 2H2O. The 31P-NMR acquisition conditions were also optimized to improve the signal-to-noise ratio: 50° pulses (70 μs) at 0.6-s intervals; 8.9 kHz spectral width; Waltz-16 1H-decoupling sequence (2.5 W during acquisition, 0.5 W during delay); free induction decays were collected as 8,000 data points, zero filled to 16,000, and processed with a 2-Hz exponential line broadening; the number of scans was chosen according to the time of kinetics and is indicated in the legends of the corresponding figures. Spectra are referenced to methylenediphosphonate (pH 8.9) contained in a 0.8-mm capillary placed in the center of the NMR tube at 16.38 ppm. Assignments and quantifications were carried out by comparison with the spectra of corresponding perchloric acid extracts according to Roberts and Jardetzky (1981) and Aubert et al. (1996). The concentration of metabolites in different cell compartments was calculated assuming that the cytoplasm-to-cell ratio was close to 0.15 in the cell culture suspensions used (Bligny and Douce, 1976) and that mitochondria + plastids occupy 12% of the cytoplasmic volume in sycamore and 20% in Arabidopsis.

Where specified, Arabidopsis cells were illuminated in the NMR tube with a quartz light-scattering rod placed in the center of the tube parallel to its axis. The rod was connected to an 1,800-W light source (Oriel) delivering a 700-μmol m−2 s−1 photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) at the contact of the sample. The PPFD measured at the outer surface of the tube containing packed cells was approximately 300 to 400 μmol m−2 s−1, indicating that illumination was attenuated by the cells and was not uniform throughout the sample. However, we verified that it was still sufficient to saturate the photosynthetic activity of all cells.

In vitro 31P-NMR spectra of isolated sycamore cell vacuoles were recorded on the Bruker AMX 400 NMR spectrometer equipped with a 10-mm multinuclear probe tuned at 161.9 MHz. Acquisition conditions were as follows: 70° pulses (15 μs) at 3.6-s intervals; 8.2 kHz spectral width; Waltz-16 1H-decoupling sequence (1 W during acquisition, 0.5 W during delay); 16,000 data points for free induction decays were zero filled to 32,000 and processed with a 1-Hz exponential line broadening. Spectra are referenced to methylenediphosphonate (pH 8.9) contained in a 0.8-mm capillary placed in the NMR tube at 16.38 ppm.

Other Analytical Methods

The wet weight of cell samples and the growth of suspension culture cells were measured as described by Bligny and Leguay (1987). Cell respiration and photosynthesis were controlled over all experiments using a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Hansatech) at 25°C. For photosynthesis measurements, 0.1 mm potassium hydrogenocarbonate (pH 6.8) was added to NM and samples were lightened above saturation (400 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD) using a Shott KL 1500 light generator.

Supplemental Data

The following material is available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Characterization of MeP uptake by sycamore cells in the presence and absence of Pi.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. George Ratcliffe for helpful discussion during the preparation of the manuscript. We thank Drs. Fabrice Rébeillé, Maryse Block, and James Tabony for reading the draft of the manuscript and for critical comments. We thank Jean-Luc Lebail for his assistance with NMR.

This work was supported by the Unité Mixte de Recherche 5168, the Institut de Recherche en Technologies et Sciences pour le Vivant, and the European Union (grant no. BIO 4 CT 960770 to J.P.).

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Richard Bligny (rbligny@cea.fr).

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Open Access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Aubert S, Bligny R, Douce R (1996) NMR studies of metabolism in cell suspensions and tissue cultures. In Y Shachar-Hill, P Pfeffer, eds, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance in Plant Biology. American Society of Plant Physiologists, Rockville, MD, pp 109–144

- Aubert S, Gout E, Bligny R, Douce R (1994) Multiple effects of glycerol on plant cell metabolism. J Biol Chem 269 21420–21427 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber SA, Walker JM, Vasey EH (1963) Mechanisms for the movements of plant nutrients from the soil and fertilizer to the plant root. J Agric Food Chem 11 204–207 [Google Scholar]

- Bieleski RL (1973) Phosphate pools, phosphate transport, and phosphate availability. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 24 225–252 [Google Scholar]

- Bligny R, Douce R (1976) Les mitochondries de cellules végétales isolées (Acer pseudoplatanus L.). Physiol Veg 14 499–515 [Google Scholar]

- Bligny R, Foray MF, Roby C, Douce R (1989) Transport and phosphorylation of choline in higher plant cells: phosphorous-31 nuclear magnetic resonance studies. J Biol Chem 264 4888–4895 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligny R, Gardestrom P, Roby C, Douce R (1990) 31P NMR studies of spinach leaves and their chloroplasts. J Biol Chem 265 1319–1326 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligny R, Leguay JJ (1987) Techniques of cell suspension culture. Methods Enzymol 148 3–16 [Google Scholar]

- Bourne RM (1990) A 31P-NMR study of phosphate transport and compartmentation in Candida utilis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1055 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couldwell DL, Dunford R, Kruger NJ, Lloyd DC, Ratcliffe RG, Smith AMO (2009) Response of cytoplasmic pH to anoxia in plant tissues with altered activities of fermentation enzymes: application of methyl phosphonate as an NMR pH probe. Ann Bot (Lond) 103 249–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danova-Alt R, Dijkema C, De Waard P, Köck M (2008) Transport and compartmentation of phosphite in higher plant cells: kinetic and 31P nuclear magnetic resonance studies. Plant Cell Environ 31 1510–1521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFronzo M, Gillies RJ (1987) Characterization of methylphosphonate as a 31P NMR pH indicator. J Biol Chem 262 11032–11037 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörmann P, Benning C (2002) Galactolipids rule in seed plants. Trends Plant Sci 7 112–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douce R, Aubert S, Neuburger M (1997) Metabolite exchange between the mitochondrion and the cytosol. In DT Dennis, DH Turpin, DD Lefebvre, DB Layzell, eds, Plant Metabolism. Addison Wesley Longman, Essex, UK, pp 234–251

- Douce R, Joyard J (1990) Biochemistry and function of the plasmid envelope. Annu Rev Cell Biol 6 173–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobny M, Fischer-Schliebs E, Lüttge U, Ratajczak R (2003) Coordination of V-ATPase and V-PPase at the vacuolar membrane of plant cells. In Progress in Botany, Vol 64. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 171–216

- Dunlop J, Phung T (1998) Phosphate and slow vacuolar channels in Beta vulgaris. Aust J Plant Physiol 25 709–718 [Google Scholar]

- Fang ZY, Shao C, Meng YJ, Wu P, Chen M (2009) Phosphate signaling in Arabidopsis and Oryza sativa. Plant Sci 176 170–180 [Google Scholar]

- Flügge UI (1999) Phosphate translocators in plastids. Annu Rev Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50 27–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gout E, Boisson AM, Aubert S, Douce R, Bligny R (2001) Origin of the cytoplasmic pH changes during anaerobic stress in higher plant cells: carbon-13 and phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance studies. Plant Physiol 125 912–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heber U, Heldt HW (1981) The chloroplast envelope: structure, function, and role in leaf metabolism. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 32 139–168 [Google Scholar]

- Heldt HW (1979) Light-dependent changes of stromal H+ and Mg+2 concentrations controlling CO2 fixation. In M Gibbs, E Latzko, eds, Photosynthesis II, Vol 6. Springer, Berlin, pp 202–207

- Jaquinod M, Villiers F, Kieffer-Jaquinod S, Hugouvieux V, Bruley C, Garin J, Bourguignon J (2007) A proteomics dissection of Arabidopsis thaliana vacuoles isolated from cell culture. Mol Cell Proteomics 6 394–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouhet J, Maréchal E, Bligny R, Joyard J, Block MA (2003) Transient increase of phosphatidylcholine in plant cells in response to phosphate deprivation. FEBS Lett 544 63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamport DTA (1964) Cell suspension cultures of higher plants: isolation and growth energetics. Exp Cell Res 33 195–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer MJ, Blevins DG, Gracz SH (1989) 31P-Nuclear magnetic resonance determination of phosphate compartmentation in leaves of reproductive soybeans (Glycine max L.) as affected by phosphate nutrition. Plant Physiol 89 1331–1336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun-Garcia A, Chiltz A, Gout E, Bligny R, Pugin A (2002) Questioning the role of salicylic acid and cytosolic acidification in mitogen-activated protein kinase activation induced by cryptogein in tobacco cells. Planta 214 792–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RB, Ratcliffe RG (1993) Subcellular distribution of inorganic phosphate, and levels of nucleoside triphosphate, in mature maize roots at low external phosphate concentrations: measurements with 31P NMR. J Exp Bot 44 587–598 [Google Scholar]

- Lee RB, Ratcliffe RG, Southon TE (1990) 31P NMR measurements of the cytoplasmic and vacuolar Pi content of mature maize roots: relationships with phosphorus status and phosphate fluxes. J Exp Bot 41 1063–1078 [Google Scholar]

- Loughman BC, Ratcliffe RG, Southon TE (1989) Observations on the cytoplasmic and vacuolar orthophosphate pools in leaf tissues using in vivo 31P-NMR spectroscopy. FEBS Lett 242 279–284 [Google Scholar]

- Massonneau A, Martinoia E, Dietz KJ, Mimura T (2000) Phosphate uptake across the tonoplast of intact vacuoles isolated from suspension-cultured cells of Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don. Planta 211 390–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh CA, Oliver DJ (1994) The phosphate transporter from pea mitochondria: isolation and characterization in proteolipid vesicles. Plant Physiol 105 47–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura T (1999) Regulation of phosphate transport and homeostasis in plants. Int Rev Cytol 191 149–200 [Google Scholar]

- Mimura T, Sakano K, Shimmen T (1996) Studies on the distribution, re-translocation and homeostasis of inorganic phosphate in barley leave. Plant Cell Environ 19 311–320 [Google Scholar]

- Misson J, Raghothama KG, Jain A, Jouhet J, Block MA, Bligny R, Ortet P, Creff A, Somerville S, Rolland N, et al (2005) A genome-wide transcriptional analysis using Arabidopsis thaliana Affymetrix gene chips determined plant responses to phosphate deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102 11934–11939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourioux G, Douce R (1981) Slow passive diffusion of orthophosphate between intact isolated chloroplasts and suspending medium. Plant Physiol 67 470–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchhal US, Raghothama KG (1999) Transcriptional regulation of plant phosphate transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96 5868–5872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassay with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant 15 473–497 [Google Scholar]

- Natr L (1992) Mineral nutrients: a ubiquitous stress factor for photosynthesis. Photosynthetica 27 271–294 [Google Scholar]

- Neuburger M, Douce R (1980) Effect of bicarbonate and oxaloacetate on malate oxidation by spinach leaf mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta 589 176–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi M, Mimura T, Tsujimura T, Mitsuhashi N, Washitani-Nemoto S, Maeshima M, Martinoia E (2007) Inorganic phosphate uptake in intact vacuoles isolated from suspension-cultured cells of Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don under varying Pi status. Planta 225 711–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaxton WC, Carswell MC (1999) Metabolic aspects of the phosphate starvation response in plants. In HR Lerner, ed, Plant Responses to Environmental Stresses: From Phytohormones to Genome Reorganization. Marcel Dekker, New York, pp 349–372

- Poirier Y, Bucher M (2002) Phosphate transport and homeostasis in Arabidopsis. In CR Somerville, EM Meyerowitz, eds, The Arabidopsis Book. American Society of Plant Biologists, Rockville, MD, pp 1–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pugin A, Montrichard F, Le-Quoc K, Le-Quoc D (1986) Incidence of the method for the preparation of vacuoles on the vacuolar ATPase activity of isolated Acer pseudoplatanus cells. Plant Sci 47 165–172 [Google Scholar]

- Raghothama KG (1999) Phosphate acquisition. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50 665–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghothama KG, Karthikeyan AS (2005) Phosphate acquisition. Plant Soil 274 37–49 [Google Scholar]

- Rausch C, Bucher M (2002) Molecular mechanisms of phosphate transport in plants. Planta 216 23–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rébeillé F, Bligny R, Douce R (1984) Is the cytosolic Pi concentration a limiting factor for plant cell respiration? Plant Physiol 74 355–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rébeillé F, Bligny R, Martin JB, Douce R (1983) Relationship between the cytoplasm and the vacuole phosphate pool in Acer pseudoplatanus cells. Arch Biochem Biophys 225 143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JKM, Jardetzky O (1981) Monitoring of cellular metabolism by NMR. Biochim Biophys Acta 639 53–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JKM, Ray PM, Wade-Jardetzky N, Jardetzky O (1980) Estimation of cytoplasmic and vacuolar pH in higher plant cells by 31P NMR. Nature 283 870–872 [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A (1979) Transport across mitochondrial membranes. In G Giebisch, DC Tosteson, HH Ussing, eds, Membrane Transport in Biology, Vol II. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 263–355

- Schachtman DP, Reid RJ, Ayling SM (1998) Phosphorus uptake by plants: from soil to cell. Plant Physiol 116 447–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimogawara K, Usuda H (1995) Uptake of inorganic phosphate by suspension-cultured tobacco cells: kinetics and regulation by Pi starvation. Plant Cell Physiol 36 341–351 [Google Scholar]

- Stefanovic A, Ribot C, Rouached H, Wang Y, Chong J, Belbahri L, Delessert S, Poirier Y (2007) Members of the PHO1 gene family show limited functional redundancy in phosphate transfer to the shoot, and are regulated by phosphate deficiency via distinct pathways. Plant J 50 982–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze H, Li X, Palmgren MG (1999) Energization of plant cell membranes by H+-pumping ATPases: regulation and biosynthesis. Plant Cell 11 677–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodorou ME, Plaxton WC (1993) Metabolic adaptations of plant respiration to nutritional phosphate deprivation. Plant Physiol 101 339–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Törnroth-Horsefield S, Wang Y, Hedfalk K, Johanson U, Karlsson M, Tajkhorshid E, Neutze R, Kjellbom P (2006) Structural mechanism of plant aquaporin gating. Nature 439 688–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournaire-Roux C, Sutka M, Javot H, Gout E, Gerbeau P, Luu DT, Bligny R, Maurel C (2003) Cytosolic pH regulates root water transport during anoxic stress through gating of aquaporins. Nature 425 393–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran HT, Plaxton WC (2008) Proteomic analysis of alterations in the secretome of Arabidopsis thaliana suspension cells subjected to nutritional phosphate deficiency. Proteomics 8 4317–4326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu SI, Cavanaugh JR, Boswell RT (1990) Phosphate uptake by excised maize root tips studied by in vivo 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Plant Physiol 93 778–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter H, Robinson DG, Heldt HW (1994) Subcellular volumes and metabolite concentrations in spinach leaves. Planta 193 530–535 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.