Abstract

We have identified an active Medicago truncatula copia-like retroelement called Medicago RetroElement1-1 (MERE1-1) as an insertion in the symbiotic NSP2 gene. MERE1-1 belongs to a low-copy-number family in the sequenced Medicago genome. These copies are highly related, but only three of them have a complete coding region and polymorphism exists between the long terminal repeats of these different copies. This retroelement family is present in all M. truncatula ecotypes tested but also in other legume species like Lotus japonicus. It is active only during tissue culture in both R108 and Jemalong Medicago accessions and inserts preferentially in genes.

Transposable elements are mobile genetic elements present in a wide range of organisms from bacteria to eukaryotes and are usually classified in two different groups. Class I elements, called retrotransposons, transpose through an RNA intermediate that is reverse transcribed into a linear double-stranded DNA before its integration into the host genome (copy-and-paste mechanism). Class II elements, called DNA transposons, transpose directly via a DNA intermediate (cut-and-paste mechanism). The replicative mode of transposition of class I retrotransposons may rapidly increase their copy number, which can be extremely high in eukaryote genomes.

Because they can invade genomes, minimizing their copy number is particularly important to maintain the genome integrity, and active retroelements are generally found in low-copy-number families (Madsen et al., 2005). These elements are present in plants and mammals, but long terminal repeat (LTR) transposons appear to be rare in the latter. LINEs, SINEs, Ty3-gypsy, and Ty1-copia appear to be abundant in plants (Kumar and Bennetzen, 1999). Transposable elements are usually located in intergenic regions and tend to accumulate in centromeres, telomeres, and heterochromatic regions. An analysis of 233 Mb of the Medicago truncatula genome shows that retroelements constitute about 9.6% of the currently available genomic sequence, and the majority of the LTR retroelements belong to either the copia or gypsy superfamily (Wang and Liu, 2008).

Despite the fact that they are widespread and abundant, only a few of them have been described as active in plants: Tnt1 (Grandbastien et al., 1989), Tto1 (Hirochika et al., 2000), Tos17 (Hirochika, 1997), and LORE1 and LORE2 (Fukai et al., 2008). New transposition events in genomes have been noticed, but the correlation between transcription induction and transposition is not always obvious. Plant retroelements can be activated by tissue culture in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum [Tto1]; Hirochika, 1993), rice (Oryza sativa [Tos17]; Hirochika et al., 1996; Miyao et al., 2003), and M. truncatula (Tnt1; d'Erfurth et al., 2003). Plant retroelements are also activated by wounding or pathogen attack (Mhiri et al., 1997; Takeda et al., 1999; Melayah et al., 2001). For other plant mobile retroelements, the activation conditions have not been established (LORE1; Madsen et al., 2005). The main characteristic of these retroelements is their ability to insert randomly in the genome and to alter gene function following disruption. The creation of this genetic variability might play an important role as a source of genome plasticity needed for plant evolution (Wessler et al., 1995).

Retroelements carry in their LTR region, which can be subdivided into U3, R, and U5 regions, cis-acting sequences that control their expression in the host (Kumar and Bennetzen, 1999). Specific sequences in the LTR U3 regions have been shown to be involved in the induction of the retroelement transcription by various biotic and abiotic stress factors (Casacuberta and Grandbastien, 1993; Vernhettes et al., 1997; Takeda et al., 1999). The variability observed in these U3 regions among the different subfamilies of Tnt1 is thought to be associated with the ability of these promoters to respond to different signaling stress molecules (Vernhettes et al., 1997; Araujo et al., 2001; Beguiristain et al., 2001). DNA methylation seems to be an important factor controlling retroelement expression in plants (Martienssen and Colot, 2001), because high levels of cytosine methylation have been associated with transcriptional inactivity. This control process is apparently different between mammals and plants. Repetitive elements are methylated in both organisms, but whereas most mammalian exons are methylated, plant exons are generally not. Thus, targeting methylation specifically to transposons appears to be restricted to plants (Rabinowicz et al., 2003). Transcription reduction of Tto1, Ttnt1, and Tos17 was correlated to their methylation status in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and rice (Hirochika et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2004; Perez-Hormaeche et al., 2008), but the factors controlling this methylation are not clearly understood. Moreover, posttranscriptional regulation of the transposition is also an important step of the retrotransposition. In Neurospora crassa, the LINE1-like retroelement is repressed by the posttranscriptional gene silencing machinery independently of DNA methylation (Nolan et al., 2005). In contrast, the DNA methylation machinery had no obvious effects on its expression. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Ty1 copy number control occurs by both transcriptional and posttranscriptional cosuppression (Garfinkel et al., 2003).

We describe here Medicago RetroElement1-1 (MERE1-1), an active retroelement in M. truncatula. This retroelement belongs to a small copia-like retroelement family of five to 10 members corresponding to the Mtr16 family defined by Wang and Liu (2008). This family is also present in other legumes. MERE1-1 has transposed in several M. truncatula mutant collections, and its transposition activity is correlated to in vitro tissue culture and to methylation of its sequence.

RESULTS

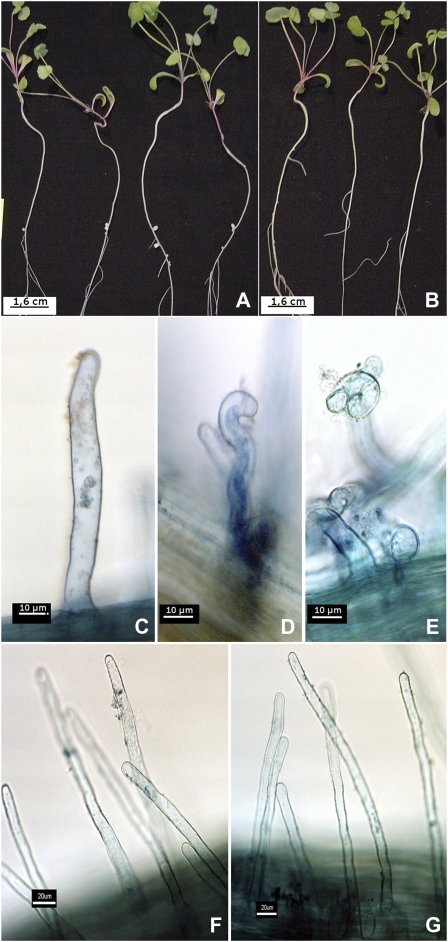

Identification of MERE1, an Active Retroelement in M. truncatula

During a screen for M. truncatula nodulation mutants in a T-DNA mutant collection (Scholte et al., 2002), a nonnodulating (nod−) mutant (ms219) was identified (Brocard et al., 2006). We have shown that the corresponding (somaclonal) mutation does not correlate with the presence of the T-DNA in this mutant line. No root hair deformation or primordium formation was observed after inoculation of the mutant with Sinorhizobium meliloti, indicating that the symbiotic process was blocked early (Fig. 1), similarly to the nfp mutant (Amor et al., 2003). The expression of marker genes for early nodule development, ENOD11 (Journet et al., 2001), ENOD12 (Journet et al., 1994), and MtN6 and Rip1 (Cook et al., 1995), was absent (ENOD11 and ENOD12) or reduced (MtN6 and Rip1) in the mutant, in agreement with an alteration of Nod factor perception (Supplemental Fig. S1). Allelic tests performed between ms219 and other mutants affected in early Nod factor signaling, nfp (Amor et al., 2003), dmi1, dmi2, and dmi3 (Catoira et al., 2000), indicated that these genes were not affected in ms219 (data not shown). Because the phenotype and the allelic tests indicated that the mutation could correspond to a new symbiotic locus, the mutation was mapped using crosses between the ms219 mutant (background R108) and the Jemalong 5 (J5) line. The F2 populations from six independent crosses were used for mapping using markers based on PCR fragment-length polymorphisms (see “Materials and Methods”; Supplemental Table S1). The mutation was located to a 3-centimorgan region on chromosome 3 bordered by bacterial artificial chromosomes AC149303 and AC126782 (www.medicago.org). This genomic region includes the NSP2 gene (Kalo et al., 2005). Therefore, this gene was considered as a candidate for the symbiotic gene despite the different phenotype described for the known nsp2 mutant (root hair branching). Amplification of the NSP2 coding sequence in three independent ms219 plants using long-range DNA polymerase demonstrated that the NSP2 sequence contained an insert of approximately 5.3 kb, which was likely responsible for the mutation (data not shown). Sequencing of the insert identified a retrotransposon, inserted at base pair 1,062 (Fig. 2A) of the NSP2 coding sequence. We named this transposon MERE1-1.

Figure 1.

Phenotype of the nsp2 nonnodulating mutant. A and B, Wild-type (A) and nsp2-4 (B) plants inoculated with S. meliloti FSM.Ma strain. C, Light microscopy of wild-type noninoculated root hairs. D and E, Curled wild-type root hairs or forming “shepherd's crook” observed after inoculation with Rm1021 strain. F, Nonnoculated root hair in MtNSP2. G, Noncurling MtNSP2 root hair inoculated with Rm1021 strain. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

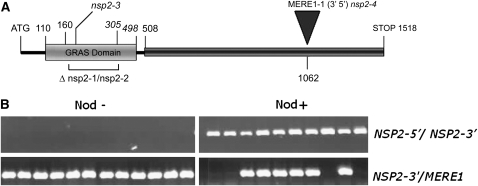

Figure 2.

Characterization of the nsp2-4 mutant. A, Structure of the NSP2 gene. The locations of the NSP2 GRAS domain (gray box) and variable N-terminal region (black box) are indicated. Positions are given in base pairs relative to the AUG. MERE1-1 is inserted at base pair 1,062 in the variable N-terminal region (3′–5′ direction). nsp2-1 and nsp2-2 are two fast-neutron-generated mutants containing a 435-bp in-frame deletion. nsp2-3 is an ethylmethane sulfonate mutant allele. B, Cosegregation of the MERE1 insertion in the NSP2 locus (NSP2-4∷MERE1) with the nonnodulating phenotype of nsp2-4. A total of 41 F2 nod− and 96 F2 nod+ plants from a backcross between R108 NSP2-4 and J5 NSP2 were used to PCR amplify wild-type or mutant loci (the results for 10 nod− and 10 nod+ plants are presented). The absence of amplification products using NSP2-specific primers (NSP2-5′/NSP2-3′) indicates that all nod− individuals are homozygous for the NSP2-4∷MERE1 insertion. Amplification of a NSP2-3′/MERE1-specific product using primers NSP2-3′ and MERE1 in the same samples shows the presence of the MERE1 insertion. The nod+ individuals are either wild type (no NSP2-MERE1 product) or heterozygous (presence of the two PCR products) for the NSP2-4∷MERE1 insertion.

To demonstrate that the insertion of MERE1-1 into the NSP2 gene cosegregated with the mutant phenotype, the wild type and the nsp2 mutant allele, named nsp2-4 hereafter, were PCR amplified using primers specific for both alleles (Fig. 2B). This showed that the nsp2-4∷MERE1-1 insertion cosegregated with the nod− phenotype. Finally, to prove that the insertion in the NSP2 gene is responsible for the phenotype, the nsp2-4 allele was crossed with the nsp2-1 allele (Kalo et al., 2005). The F1 individuals had a nod− phenotype, demonstrating the allelism of both mutants.

MERE1-1 Belongs to a Small Family of Copia Retroelements

The MERE1-1 retroelement identified at the NSP2 locus is a 5,300-bp-long element and has two long terminal repeat (LTR) regions of 574 bp (Fig. 3A). This element is flanked by a 5-bp duplication of host DNA corresponding to the target site duplication (TSD). A single 1,305-amino acid open reading frame (ORF), starting at base pair 746 and ending at base pair 4,660, displays, after in silico translation, a strong similarity with the GAG-POL protein of plant retroviral elements. The location of the reverse transcriptase domain behind the endonuclease (endo) classifies MERE1 as a Ty1-copia retrotransposon.

Figure 3.

Structure of the MERE1-1 retroelement representing the MERE1 family. A, Schematic representation of MERE1-1. Gray boxes at the two extremities represent LTRs, divided into three parts: U3 (promoter), R (polyadenylation signal), and U5. Shaded boxes indicate regions showing homology with characteristic retrotransposon proteins. The hatched box below the RT region represents the DNA fragment used as a probe in Southern- and northern-blot analyses. From N to C terminus, the unique MERE1-1 ORF shows extensive amino acid homology to copia GAG (structural core proteins), PROT (protease involved in maturation of GAG polyproteins), ENDO (endonuclease involved in integration into the host DNA) and RT (reverse transcriptase) domains. Putative primer binding sites (PBS) and polypurine tract (PPT), necessary for cDNA synthesis of the retrotransposon, are shown below, as well as the complementary region between PBS and the 3′ end of legume tRNAmet. B, Sequence comparison of the LTR regions from MERE1-1 to MERE1-5. The U5 region shows a high level of identity between the five sequences, whereas the U3 region shows significant variability. The putative TATA box is indicated by the box. The positions of the different oligonucleotides used in this study are indicated by arrows above the sequences. MERE6N and MERE5N represent the positions of the specific oligonucleotides MERE61, MERE62, MERE63, MERE64, MERE51, and MERE52 (for sequences, see “Materials and Methods”). [See online article for color version of this figure.]

BLAST searches against the M. truncatula Jemalong genome sequence allowed the identification of five complete MERE1 elements, numbered MERE1-1 to MERE1-5, corresponding to the Mtr16 family recently described by Wang and Liu (2008; for accession numbers, see “Materials and Methods”). MERE1-1 has been identified as the element present at the NSP2 locus. Three of the MERE1 elements have the 1,305-amino acid full-length ORF (MERE1-1, MERE1-3, and MERE1-4). The MERE1-2 sequence has an additional T at nucleotide 2,852, creating a frame shift generating a truncated 707-amino acid ORF. The MERE1-5 sequence contains a stop codon at position 1,950, resulting in a truncated 425-amino acid ORF. The three full-length ORF elements (MERE1-1, -3, and -4) could represent active retroelements, and the two others could represent inactive ones. Comparison of the MERE1 family LTR sequences shows conservation of the U5 region but many differences in the U3 promoter region (Fig. 3B). Among the five elements described above, MERE1-1, -2, and -3 have identical 5′ and 3′ LTRs. The two LTRs from MERE1-4 show 3-bp differences, and MERE1-5 LTRs show 6-bp differences. BLASTn search analysis indicated the presence of at least five solo LTRs related to the MERE1 family in the Medicago pseudogenome. Phylogenetical analysis indicated that none of these correspond to the LTRs of the MERE1-1 to MERE1-5 elements (Supplemental Fig. S2).

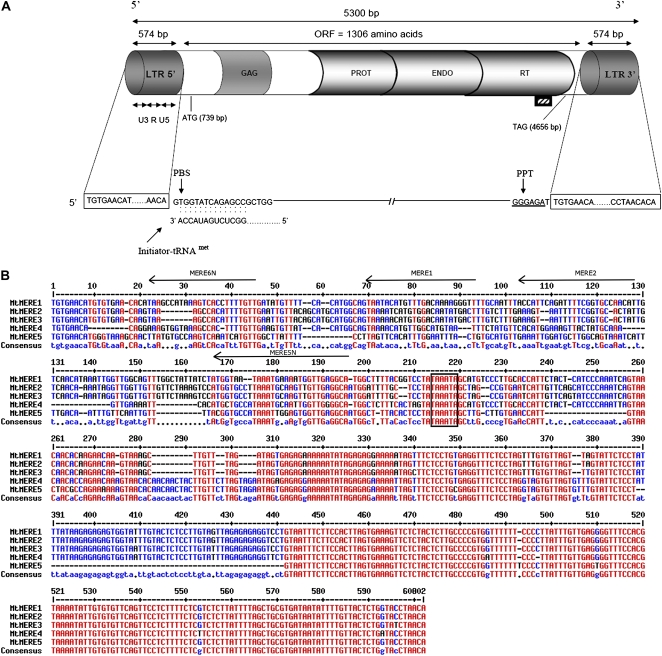

The MERE1 Element Is Present at Low Copy Number in M. truncatula and Other Legume Species

To evaluate the copy number of the MERE1 element in the entire Medicago genome, a Southern-blot analysis was performed using a probe corresponding to the 3′ extremity of the polymerase region (Fig. 3A). This analysis indicates that the MERE1 family is present at moderate copy number in the different lines analyzed (Fig. 4A), suggesting that only a few additional copies are present in the heterochromatic unsequenced region of the genome. To analyze the MERE1 family members in more detail, a retrotransposon display method (see “Materials and Methods”) was used, which allowed a better discrimination of the different MERE1 elements present in the genome. Figure 4B shows that many bands are common to J5 and the related 2HA line and to R108 and its derivative nsp2-4. However, a polymorphism is detected between the Jemalong and R108 lines. Similarly, using this technique, a polymorphism can be detected between the different lines from a small M. truncatula ecotype collection (Fig. 4C), despite a rather constant copy number of the element in these different lines. Bands shared by some of these ecotypes (e.g. F83.005.9, DZA0517, F20061A, F34024A, and ESP158A) were identified, probably indicating a common geographical origin.

Figure 4.

Copy number of the MERE1 retroelement in M. truncatula. A, Southern-blot analysis of M. truncatula 2HA, J5, R108, and NSP2-4 lines. Ten micrograms of gDNA was double digested with HpaI and NcoI restriction enzymes. The probe used is indicated in Figure 3A. B, Transposon display of MERE1 5′ insertion sites in wild-type and NSP2-4 mutant lines. The fragments labeled with asterisks represent copies of the MERE1-1 element different between 2HA and J5 lines. DNA was digested with the AseI restriction enzyme. PCR amplification was done using the oligonucleotide pairs MERE2/Ase1 and MERE1/Ase2. C, Transposon display of MERE1-1 insertion sites in different Medicago accessions. Arabidopsis (ecotype Columbia [Col0]) was used as a negative control for this experiment. The average number of retroelements in the different ecotypes is less than 10. The origin of the different Medicago lines is given in “Materials and Methods.” DNA was digested with the AseI restriction enzyme. PCR amplification was done using the oligonucleotide pairs MERE2/Ase1 and MERE1/Ase2.

Data mining also indicated that MERE1-1 belongs to clade 1 (Wang and Liu, 2008) of copia plant retroelements and that MERE1-like retroelements are present in different legume species (Supplemental Fig. S3). The MERE1 family is related to the Cajanus Panzee element described by Lall et al. (2002), and we could identify at least two full-length retroelements with LTR sequences similar to MERE1 in the Lotus japonicus MG.20 genome (AP004536 and AP006407). The LTR sequences from these two elements are 65% similar, and only one L. japonicus element has a complete GAG-POL protein. The analysis also indicates that closely related elements are present in Populus tremulus and Ipomoea batatas plants.

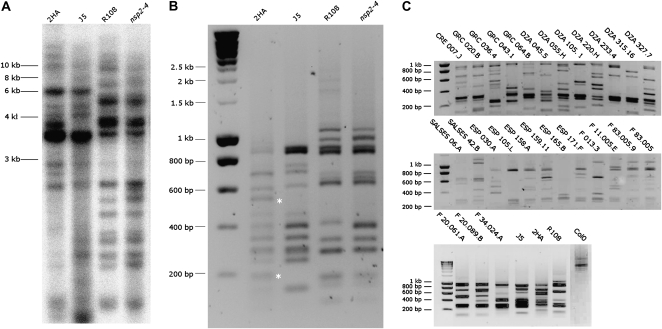

MERE1 Transposes in in Vitro-Produced M. truncatula Plants

Because the MERE1 copy number is low and seems to be stable in wild-type Medicago plants, we hypothesized that transposition at the NSP2 locus was induced by the tissue culture treatment in our Medicago transgenic plants. Thus, in order to rule out that the transposition of the MERE1 element was restricted to the ms219 nod− mutant, the presence of MERE1 additional copies was monitored in transgenic plants of different mutant collections generated by in vitro culture in our laboratory.

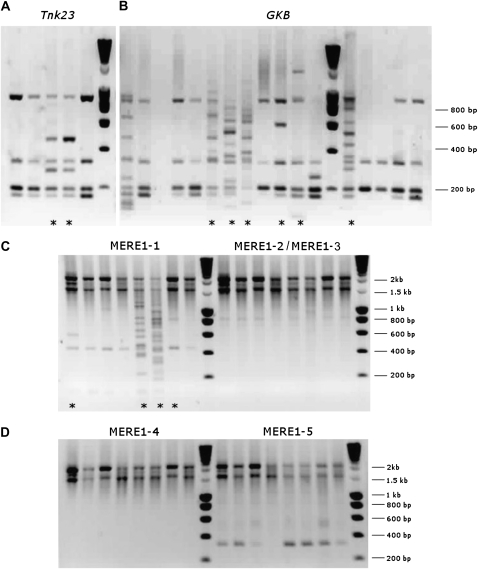

MERE1 transposition was first tested using two Medicago R108 collections: the Tnt1 R108 collection (Tnk mutants, 250 lines; d'Erfurth et al., 2003) and the T-DNA collection (GKB mutants, 500 lines; Scholte et al., 2002; Brocard et al., 2006). The different MERE1 borders produced in these experiments suggest that transposition occurred in some of the mutant lines (Fig. 5, A and B), because the pattern of fragments observed for these plants is unique. Altogether, this experiment demonstrates that transposition occurred in 73 plants over a total of 183 analyzed plants (40% of plants with new transposition events). This represents one to more than 10 new insertions in the regenerated plants and an average of one new copy per plant in these collections.

Figure 5.

Transposon display of MERE1 elements in in vitro-regenerated plants. DNA was digested with the AseI restriction enzyme. The additional fragments detected in lines marked with asterisks correspond to new insertion sites of MERE1. Bands larger than 1,500 bp are PCR experimental artifacts. A, Tnk23 regenerated plants from the Tnt1 collection (R108 background); five out of 23 analyzed plants are shown. PCR amplification was done using the oligonucleotide pairs MERE51+MERE52/Ase1 and MERE61/Ase2. B, GKB regenerated plants from the T-DNA collection (R108 background); 16 out of 39 analyzed plants are shown. PCR amplification was done using the oligonucleotide pairs MERE51+MERE52/Ase1 and MERE61/Ase2. C and D, Transposition of the various MERE1 elements in regenerated 2HA Jemalong plants. The analysis of eight out of 96 lines is shown. PCR amplification was done using the oligonucleotide pairs MERE51+MERE52/Ase1 for PCR1 followed by MERE61/Ase2 for MERE1-1, MERE62/Ase2 for MERE1-2/MERE1-3, MERE63/Ase2 for MERE1-4, and MERE64/Ase2 for MERE1-5 for PCR2.

MERE1 activity was also tested in regenerated Jemalong 2HA plants (Tnt1 insertion mutant collection). As the LTRs of the different MERE1 members present in the Jemalong genome have differences in the 3′ extremity, specific primers were designed to allow the specific amplification of the different transposon borders (MERE1-2 and MERE1-3 cannot be discriminated by this technique). This experiment (Fig. 5, C and D) shows that new MERE1-specific fragments could be detected in some of the transgenic plants, indicating that transposition of MERE1 occurs in a subset of the regenerated plants from this collection. Surprisingly, we were able to detect the presence of new copies only for the MERE1-1 element, indicating that it could be the only active/mobile retroelement during tissue culture in Medicago.

PCR amplification of the MERE1-specific borders in a larger number of regenerated Jemalong 2HA and R108 plants confirmed that MERE1-1 is indeed the only active retroelement in these two plants (data not shown). In addition, this analysis indicates that in the two Medicago lines transposition is restricted to tissue culture, because no new copies could be detected in the progeny of these plants (data not shown).

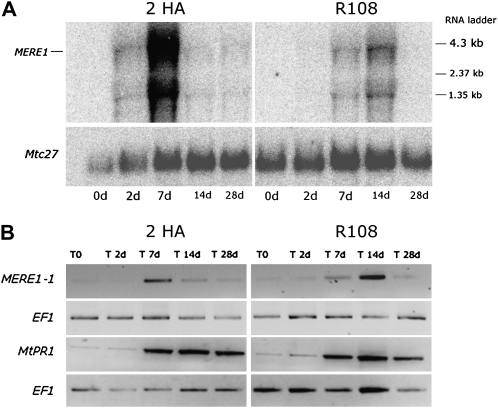

MERE1 Is Expressed during in Vitro Tissue Culture

As described above, MERE1 transposition was observed in Medicago plants produced using in vitro tissue culture. To investigate the regulation of MERE1 activity under these conditions, its transcription activity was monitored in calli from 2HA and R108 lines cultivated on the SH3a callus-inducing medium (Cosson et al., 2006). In the two experiments, MERE1 expression was transiently induced in both lines (Fig. 6A). The induction in the 2HA line started 2 d after in vitro culture and decreased after 7 d. For the R108 line, the induction was delayed and reached a peak at 14 d. In both lines, a decrease of the expression was observed later on. In this northern-blot experiment, the probe could not discriminate the different members of the MERE1 family. Figure 6B shows that similar results were obtained in reverse transcription (RT)-PCR experiments using oligonucleotides specific for the active MERE1-1 retroelement, suggesting that this copy is active under the test conditions.

Figure 6.

Analysis of MERE1 expression in the Jemalong 2HA and R108 lines during in vitro culture. A, Northern-blot analysis of MERE1 expression. For each time point, 10 μg of total mRNA was loaded on the gel and the blot was hybridized with the probe indicated in Figure 3A or with the Mtc27 constitutive gene probe. The 4.3-kb transcript corresponds to a full-length MERE1 transcript. B, RT-PCR analysis of MERE1-1 and MtPR1 expression. MERE1-1 expression was analyzed using oligonucleotides specific for this element (MERE61-2/MERE61-4). The EF1α gene was used as a constitutive gene control.

In order to better visualize the expression of the complete MERE1 family present in the sequenced and unsequenced parts of the genome, a PCR experiment was done with nonspecific oligonucleotides that allow the amplification of a 471-bp region (positions 4,251–4,722 in MERE1-1) at the C-terminal extremity of the GAG-POL protein. In this region, 43 positions allow discrimination between the different MERE1 members. The PCR experiment was done using cDNA of 14-d in vitro explants and 2HA genomic DNA (gDNA), and 66 independent PCR fragments were analyzed for cDNA and gDNA. The sequence analysis showed that all MERE1 full-length members were detected in gDNA (Supplemental Table S2). In addition, incomplete copies present in the sequenced genome as well as a limited number of unknown MERE-like sequences, including some MERE1-1/MERE1-4 and MERE1-5 closely related sequences, could also be detected. These latter are probably present in the part of the genome not yet sequenced, and for this reason we cannot know if they represent complete MERE1 copies. Using the cDNAs, MERE1-3, MERE1-4, and MERE1-5 sequences were not detected, suggesting that these copies are not expressed under these conditions. The other MERE1-related sequences could be identified in the cDNA sample. Supplemental Table S2 shows that the MERE1-1 element is the only fully described element with a complete ORF and identical 5′ and 3′ LTRs whose expression is induced during the early stages of the tissue culture conditions. This result is in agreement with its transposition activity during tissue culture.

In order to test if, as described for other elements (Casacuberta and Grandbastien, 1993; Grandbastien et al., 1997; Vernhettes et al., 1997; Takeda et al., 1999), MERE transcription was associated with stresses induced by the in vitro conditions, we studied the expression of a pathogenesis-related (PR) protein marker, MtPR1 (Szybiak-Strozycka et al., 1995), in the experiment described above. Szybiak-Strozycka et al. (1995) have shown that MtPR1 is most strongly similar to pathogenesis-related proteins that are known to be induced upon stress, pathogen attack, and abiotic stimuli. PR up-regulation, therefore, is a good indication of various stress-related stimuli. MtPR1 expression was already detectable at the beginning of the in vitro culture (T0) but increased 7 d after the beginning of the experiment for 2HA and R108 lines (Fig. 6B). This induction correlates with the MERE1 induction in these samples, in agreement with the fact that the in vitro culture conditions (callus formation) used for plant regeneration represent stress conditions. However, no specific induction of MERE1-1 expression could be observed after culture of leaf explants cultivated in vitro on medium supplemented with aminoethoxyvinylglycine, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid, salicylic acid, or methyl jasmonate (data not shown). This suggests that these stress-related hormones are not directly responsible for induction of MERE1-1 expression in vitro. Similarly, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and benzylaminopurine growth hormones used during in vitro regeneration were unable to induce MERE1 expression on their own (data not shown), suggesting that the expression of the element is not directly controlled by these growth hormones.

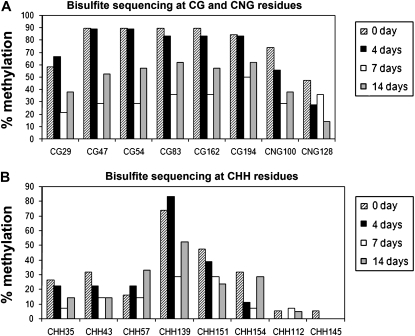

MERE1 Transcription Is Correlated with Its Methylation Status

DNA methylation may regulate the transposition of retroelements. For example, the transposition of Tto1 and Tnt1 in Arabidopsis (Hirochika et al., 2000; Perez-Hormaeche et al., 2008) or MAGGY in the fungus Magnaporthe grisea (Nakayashiki et al., 2001) is controlled by methylation.

To examine the methylation status of the MERE1 element, the cytosine methylation pattern was determined for the MERE1 family using the bisulfite methylation profiling method (Reinders et al., 2008). With this treatment, unmethylated cytosines are converted to uracil, in contrast to 5-methylcytosine located mainly in symmetrical CG and CNG (N = A or T) or nonsymmetrical CHH (H = A, T, or C) sequences (Frommer et al., 1992; Vanyushin, 2006). Bisulfite-mediated cytosine conversion and subsequent PCR create C-to-T transitions, which can be detected by sequencing. In order to detect modification of the MERE1 methylation status, gDNA was extracted from 2HA and R108 leaf explants cultivated on SH3a for 0, 4, 7, and 14 d of culture and treated with bisulfite (see “Materials and Methods”). A 225-bp specific fragment (positions 4,462–4,687; see “Materials and Methods”) was selected to study the methylation status on the MERE1 family (Supplemental Fig. S4A). This sequence was chosen because it is the most accurate to detect changes in the methylation pattern of the MERE sequence as determined by the MethPrimer program (Li and Dahiya, 2002). For each CG, CNG, and CHH present in the sequence and for each time point of the experiment, we determined the percentage of methylation (percentage of C unconverted to T; Fig. 7A; Supplemental Fig. S4B). The results obtained for the two lines (Jemalong and R108) are similar (Fig. 7A; data not shown) and indicated that the MERE1 cytosines are highly methylated before the beginning of the experiment and after 4 d of culture, when the expression of the element is still very low (Fig. 7). A significant decrease of the methylation status can be detected after 7 d using the 2HA gDNA (14 d for R108), corresponding to the peak of induction of the element as shown by northern blot. At 14 d (21 d for R108), the percentage of mCG methylation increased again. This experiment showed that the percentage of cytosine methylation of this region is inversely correlated with the activity of the retroelement, indicating a close connection between MERE1 expression and the methylation status of the CG and CNG cytosines present in its sequence. The CHH residues that were highly methylated at the beginning of the experiments also showed a transient demethylation. However, this is not the case for the residues that were much less methylated (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Methylation status at the MERE1 locus. The graph represents the level of methylation (% methylation; y axis) at the different C residues in the sequenced fragment. The DNA methylation level was determined using the bisulfite sequencing method and presented for each different sequence motif: CG, CNG, and CHH (N = A or T; H = A, T, or C). The position in the sequence indicates C residues. For complete sequence analysis, see Supplemental Fig. S4A. A, Percentage methylation of the CG and CNG residues present within the analyzed sequence. B, Percentage methylation of the CHH residues. These residues are divided into two groups: those with a methylation level superior to 20% at time 0, and those with a methylation level inferior to 20%. The results for representative CHH residues (CHH35, CHH43, CHH57, CHH139, CHH151, and CHH154) from the first group (>20%) and residues CHH112 and CHH145 from the second group (<20%) are shown.

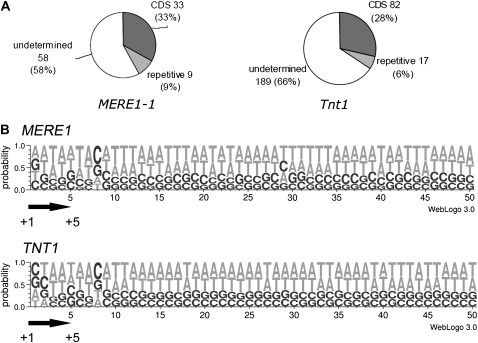

MERE1-1 Can Insert into Genes

In order to compare the nature of the sequences flanking new MERE1-1 insertions and the ones of the well-described Tnt1 tobacco element, 100 MERE1 flanking sequence tags (FSTs) and 288 Tnt1 Medicago FSTs were analyzed. The flanking sequences were classified in three classes: CDS (coding sequences), repetitive (repetitive elements), and unknown when a target sequence could not clearly be identified (Fig. 8A). Within the 100 MERE1-1 FSTs, we could identify 33 ESTs using BLASTn analysis (http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/; E value of 10−10). Similarly, a BLASTx analysis (E value of 10−10) showed that 33 sequences belong to the CDS class and nine to the repetitive elements class. The same analysis using 288 Tnt1 FSTs shows nearly the same results: 28% of the 288 FSTs belong to the CDS class and 6% to the repetitive elements. These results are in agreement with those of Tadege et al. (2008), who showed using a larger population that 34.1% of the Tnt1 inserts are in ORFs, despite CDS representing only 15.9% of the M. truncatula pseudogenome. This result indicates that coding sequences are tagged at a similar frequency by MERE1-1 and Tnt1. Moreover, the analysis of the sequences flanking the two retroelements indicated no clear consensus target site for the two elements (Fig. 8B). The GC composition of the 50 bp downstream of the two elements, including the TSD sequence, is roughly identical to the M. truncatula pseudogenome. However, a small increase in the frequency of G/C was observed at positions 1 and 5 of the TSD. In addition, at position TSD+3, G and C frequency was increased to 29% and 41%, respectively, instead of 17.5% each (Fig. 8B; Supplemental Table S3). Thus, as for Tnt1, there is a modest preferences for GC versus AT at several positions of the MERE1 integration site.

Figure 8.

MERE1-1 has no target sequence site specificity but tends to insert within the ORF. A, Distribution of the genomic sequences flanking newly transposed MERE1-1 (100 inserts) and Tnt1 (288 inserts). CDS are indicated in black, repetitive sequences in gray, and undetermined sequences in white. B, Target site sequence analysis. A total of 157 sequences were analyzed for the MERE1-1 element and 1,725 sequences for the Tnt1 element using the program WebLOGO 3.0. The size of the letters indicates the frequency of each base pair. The positions of the TSD are indicated by the arrows.

DISCUSSION

The nsp2-4 Mutant Phenotype Differs from Previously Described nsp2 Mutants

Despite being an allele of nsp2-1 and nsp2-2, which show root hair branching, nsp2-4, similar to the M. truncatula nfp mutant (Amor et al., 2003), is characterized by an absence of root hair branching under our test conditions. Different genetic background (R108 versus Jemalong) might explain the different root hair responses. In line with these differences, we observed that R108 wild-type plants showed reduced curling and branching compared with the Jemalong wild-type plants 2 d after infection, a time point when the branching phenotype appears in the nsp mutants (data not shown).

The NSP2 Gene Is Tagged by the Copia MERE1 Retroelement

In this work, we have identified an active Medicago retroelement (MERE1) that belongs to a family composed of five to 10 members in the M. truncatula genome. Our study using M. truncatula ecotypes of different geographical origin shows a constant MERE1 copy number. This suggests a relative stability of this element copy number throughout the Medicago genus. Three of the five copies, MERE1-1, -3, and -4, are complete LTR retroelements, with complete GAG-POL coding regions. Surprisingly, only one of these five elements (MERE1-1) was active during tissue culture. The two other members with intact coding capacity were stable under our experimental conditions. BLAST analysis and PCR experiments indicated that MERE1-like elements are present in other legume species like L. japonicus and Cajanus cajan, but we did not detect related elements in Arabidopsis. Interestingly, the U5 region of the LTRs is highly conserved between the elements in L. japonicus and M. truncatula, whereas the U3 region, which contains the promoter region, is more variable. This more variable sequence of the promoter region may represent an evolutionary adaptation to control the activity of the retroelement (see below).

Interestingly, the sequenced part of the genome contains only five solo LTRs, which have significant sequence differences from the full-length MERE1 LTRs. This suggests that other MERE1-1-like elements may exist in the nonsequenced part of the genome, but it also reflects the low activity of the MERE1-1 family.

MERE1 Is an Active Retroelement in M. truncatula

The mutation induced by MERE1-1 was first detected in a M. truncatula R108 background. Our work demonstrated that transposition occurred in 40% of the R108 regenerated plants from a small mutant collection, with an average new copy number of one element per plant in the total collection, indicating a mild activity of the element in this background during tissue culture. The stability of the MERE1 retroelement copy number in M. truncatula (and L. japonicus) might result, as for Tnt1 (Grandbastien et al., 1994), from a long coevolution of this particular family of retroelements with its host organism. Interestingly, this element was also found active in the M. truncatula Jemalong 2HA line used to generate the Medicago Tnt1 insertion mutant collection (www.eugrainlegume.org). In this line, the MERE1 element was also activated by the in vitro tissue culture procedure, used primarily to activate the Tnt1 element. This experiment suggests that the two retroelements might be activated under the same tissue culture conditions and at the same time in the mutant plants.

The analysis of the MERE1 integration site sequences showed that there is no hot spot for integration and no consensus sequence, except an increase of G/C residue in the TSD+3 position, for MERE1 integration site. In addition, the analysis of 100 insertion site sequences showed that, like Tnt1 (Tadege et al., 2008), MERE1 inserts twice as much as expected inside genes in M. truncatula.

The MERE1 Activity Is Detected during Tissue Culture

The induction of MERE1-1 during tissue culture reaches its maximum at different time points depending on the genotype used (7 d for 2HA versus 14 d for R108). A plausible explanation for these differences comes from the genetic background and the regeneration history of both genotypes. R108 and 2HA were subjected to several cycles of somatic embryogenesis on different growth media to select highly regenerable plants (Trinh et al., 1998; Rose et al., 1999). 2HA, therefore, will have a different regeneration capacity on a R108 medium, which was used herein to investigate MERE1 induction during tissue culture. Thus, besides being genetically different, medium-dependent callus growth may contribute to the observed shift in MERE1-1 induction.

Plants with new MERE1-1 copies did not show any transposition activity in their T2 generation, suggesting that the MERE1-1 activation was restricted to tissue culture. The absence of transposition in further generations suggests that this might be the consequence of an increase in methylation, thus silencing and stabilizing the MERE1 retroelement in regenerated plants. Transposition activity in the course of tissue culture could not be induced by stress-related or plant growth hormones, since MERE1-1 expression was not detected when either hormone was added separately to the regeneration medium (see “Results”). Our study indicated that only MERE1-1 transposes, since no copies of the additional MERE1 could be detected. The most likely explanation is that the remaining full-length MERE1 elements (MERE1-2, -4, and -5) have lost their coding capacities because of the incomplete ORF or aging restricts their transposition, as they have sequence differences between the 3′ and 5′ LTRs. The identity between 5′ and 3′ LTR sequences has been previously reported to be correlated to the activity of retroelements in mouse (Ribet et al., 2004). Those authors have shown that mobilization of MusD transposon is correlated to 100% identity between its LTRs, which is consistent with their recent transposition and them being active. More recently, Maisonhaute et al. (2007) have shown that the newly inserted 1,731 LTR retrotransposon copies in Drosophila show 100% identity compared with older copies. An exception is MERE1-3, which was not expressed (no cDNA detected) and was not recovered in any of the mutant screens despite having an intact ORF and identical LTRs. This suggests that MERE1-3 might be the target of an epigenetic regulation. Its insertion in a particular region of the M. truncatula genome might trigger genomic position effects that could result from a single phenomenon or a combination of diverse epigenetic phenomena such as DNA hypermethylation, histone modifications, or any other evolution of the chromatin state. Epigenetic regulation of retrotransposons is a known phenomenon reported in rice, Brassica rapa, Drosophila, and many other organisms (Cheng et al., 2006; Eickbush et al., 2008; Fujimoto et al., 2008). We cannot know if the other copies detected in this analysis as cDNA and gDNA fragments represent MERE1 functional elements. Further investigations will shed light on the underlying mechanisms responsible for the differential regulation of MERE1 copies in M. truncatula.

We could not detect new copies of the Lotus MERE1-like element in the progeny of transgenic Lotus plants regenerated in vitro (data not shown). Interestingly, transposition could also not be detected in Arabidopsis transgenic plants transformed with the R108 MERE1-1 element isolated from the MtNSP2 locus (data not shown). It should be noted that both transgenic Arabidopsis plants and regenerated L. japonicus plants were produced using transformation/regeneration methods not based on somatic embryogenesis. This suggests that transposition of MERE1 is dependent on the genetic background used, on tissue culture conditions, on the combination of both, or on other unknown regulatory mechanisms. Such genotype- and tissue culture-dependent transposition activity was described for Tnt1 in the M. truncatula 2HA line (Iantcheva et al., 2009). It might thus be interesting to regenerate MERE1-containing Arabidopsis or L. japonicus plants using an embryogenesis-mediated method in order to know if this procedure is crucial for the activation of these elements.

Interestingly, a phylogenetic analysis including most of the plant copia retroelement clades indicates that several tissue culture-activated plant copia elements (MERE1-1, Tnt1, and Tto1) belong to the same subfamily of the copia clade 1 (Supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that they may have retained common regulatory mechanisms that allow their activation during tissue culture.

Transcription of MERE1 Correlates with Partial Demethylation

Methylation is generally correlated with the repression of retroelements (Martienssen and Colot, 2001). We observed a clear correlation between the expression of the element and a transient diminution of the methylation status of the MERE1 element during the early steps of our in vitro experiments. The transient reduction of the methylation was particularly clear for the CG residues and for one of the two methylated CNG residues present in the analyzed sequence. The highly methylated CHH residues also showed a transient demethylation. Thus, there is a clear correlation between the methylation status of the element and its transposition activity during in vitro culture. Such tissue culture-induced demethylation was previously reported in soybean (Glycine max) and maize (Zea mays; Quemada et al., 1987; Kaeppler and Phillips, 1993). Although decrease in methylation is often associated with tissue culture, it is still unclear why this happens. We can only hypothesize an adaptive response of the plant to tissue culture stress conditions that allows a transcriptional activation of appropriate genes. Reduced methylation of MERE1 suggests that our in vitro culture conditions (somatic embryogenesis-mediated plant regeneration) might induce important changes in the methylation status of the retroelement, probably reflecting a transient demethylation of large regions of the Medicago genome that might be responsible for the activation of the MERE1 retroelement. One might speculate that this could also be the case for the transposition of Tnt1. This is a likely scenario, since it was shown in Arabidopsis that Tnt1 silencing is released in decrease in DNA methylation and polymerase IVa mutants (Pérez-Hormaeche et al., 2008). Furthermore, those authors report a negative correlation between Tnt1 copy number and its silencing, which was shown to be associated with short interfering RNAs, suggesting an RNA-directed DNA methylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

The NSP2-4 allele was originally called ms219. The first NSP2-1 allele was described by Kalo et al. (2005). Medicago truncatula lines J5, 2HA (2HA3-9-10-3), and R108 (Trinh et al., 1998; Rose et al., 1999) were used as the wild type. The M. truncatula accessions were provided by J.M. Prosperi (INRA UMR DIAPC; http://www1.montpellier.inra.fr/BRC-MTR/) and were characterized previously using microsatellite markers as described by Ronfort et al. (2006). DZA lines originate from Algeria, F and Salses lines from France, ESP lines from Spain, GRC lines from Greece, and CRE lines from Crete. The Jemalong Tnt1 insertion mutant collection was constructed in the frame of the FP6 GLIP program (www.eugrainlegumes.org). GKB mutants were described by Brocard et al. (2006). Plants for leaf explants were grown 4 weeks on SHb10 medium (EMBO Practical Course on the New Plant Model System Medicago truncatula: Module 2; http://www.isv.cnrs-gif.fr/embo01/index.html) in environmentally controlled walk-in growth chambers at 24°C and 200 μmol photon m−2 s−1 light intensity. MERE1-1 corresponds to the Mtr16 element recently described by Wang and Liu (2008), localized on bacterial artificial chromosome clone CR931743.

Bacterial Strains

The Escherichia coli strain XL1 Blue (Stratagene) was used for cloning and propagation of different vectors. Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 strain (Hood et al., 1993) was used in all plant transformation experiments. Plant transformation vectors were introduced into this strain by electroporation (Mattanovich et al., 1989). For the nodulation tests, plants were inoculated 4 d after germination using strain FSM.Ma (www.ccmm.ma) or Sinorhizobium meliloti 1021 (NC 003047; Galibert et al., 2001) culture resuspended in sterile water (optical density at 600 nm = 0.3).

Plant Tissue Culture

Regenerated plants and calli were obtained according to Cosson et al. (2006). For time course experiments, plants were first cultivated in vitro during 4 weeks, and leaf explants were scarified with surgical blades and placed on SH3a medium as described by (Cosson et al., 2006) for 4 weeks in two independent experiments.

Isolation of the NSP2-4 Allele

The nsp2-4 allele was identified by forward genetic screening of an R108-derived T-DNA mutant collection (Brocard et al., 2006) inoculated with Sm1021. The nodulation test was carried out in the greenhouse with approximately 30 T2 plants grown in a sand:perlite mix (1:3, v/v) for 4 weeks after inoculation. Nonnodulating plants were screened a second time 3 weeks later after a second inoculation. Nonnodulating plants recovered from the second screen were grown to seed in standard soil in greenhouse conditions.

Root Hair Observations

Seeds were germinated in sterile water overnight at room temperature. Plants were cultivated on buffered nodulation medium (Ehrhardt et al., 1992) for 2 d and inoculated with a suspension of bacteria at optical density at 600 nm = 0.3. Plants were stained for 15 min with 0.02% methylene blue, rinsed three times with liquid buffered nodulation medium, and observed with a Polyvart Reichert microscope equipped with a Nikon DXM1200 camera.

Mapping Population

Two independent T1 plants of ms219 were backcrossed with the J5 accession. Six independent crosses were obtained, and the F2 population was tested for its symbiotic phenotype as described above. The mapping population contained 45 nod− plants and 113 nod+ plants. gDNA was extracted from 137 plants (41 nod− plants and 96 nod+ plants) and used for the PCR mapping experiments. Genetic markers are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Southern-Blot Analysis

Ten micrograms of DNA was digested with restriction enzyme under conditions specified by the suppliers and separated on a 1× Tris-acetate EDTA, 1% agarose gel overnight at 1 V cm−1. Southern blotting was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (1989), and probe hybridization as described by Church and Gilbert (1984). The MERE1 probe consists of a 520-bp PCR fragment located between MERE1 nucleotides 4,198 and 4,718 (Fig. 3A).

Transposon Display Analysis

MERE1 borders were isolated using the transposon display method. gDNA was extracted, and 1 μg was digested with AseI restriction enzyme for 3 h. The enzyme was inactivated at 65°C for 20 min. AseI adaptors (Ase-adap1 [5′-CCCCTCGTAGACTGCGTACC-3′] plus Ase-adap2 [5′-TAGGTACGCAGTCTACGA-3′]) were ligated (T4 DNA ligase; Fermentas) at 16°C overnight. Preamplification (PCR1) was done using MERE2 or MERE51/MERE52 and Ase1 primers, and the PCR products were diluted 1:100 for a second PCR (PCR2) using MERE1, MERE61, MERE62, MERE63 or MERE64, and Ase2 primers.

The PCR1 program was as follows: 94°C for 2 min; five times 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 1.5 min; five times 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 1.5 min; 20 times 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 1.5 min. The PCR2 program was as follows: 94°C for 2 min; 10 times 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 1.5 min; 25 times 94°C for 20 s, 52°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 1.5. PCR products were analyzed on 1.5% agarose gels.

Primers were as follows: MERE1 (5′-AGCCCTTTTGTCAAACATGTATTA-3′), MERE2 (5′-AATGTTGGCACCGAAAATCTGAATGGT-3′), MERE61 (5′-AACAAAAGGTGACTTTATGGCTT-3′), MERE62 (5′-CAACAAAATGTGGCTTTACTTGT-3′), MERE63 (5′-CAACAAAAGTGGCTTTACCACT-3′), MERE64 (5′-CAACATGATTTGACTTGGCACA-3′), MERE51 (5′-GCCTCAACCATTTTCATTTATTACCAT-3′), and MERE52 (5′-TGCCTCAACCAMTYSMATTTAWGGCA-3′).

Northern Blot

Total RNA was extracted from 2 g of plant material according to Kay et al. (1987). The RNA concentration was measured with a spectrophotometer (ND-100; Nanodrop). Ten micrograms of RNA was used for northern blotting according to Sambrook et al. (1989). The MERE1 probe is the same as the one used for Southern blotting. Constitutively expressed gene Mtc27 was used as a control (TC 85211; Verdier et al., 2008).

RT-PCR

Samples were collected at 0, 2, 7, 14, and 28 d of in vitro culture and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA for RT-PCR analysis was prepared from M. truncatula samples using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Residual gDNA was removed using RNase-free DNase (Qiagen). From 2 μg of total RNA, cDNA was generated using SuperScript reverse transcriptase (GibcoBRL/Life Technologies). The MERE1-specific primer pair used was MERE61-2 (5′-GTGAACATGTGTGAACACATAAGCC-3′) and MERE61-4 (5′-GCAAGGGACATGCTATTTATAGGACC-3′). PRL-1-specific primers were designed against the PRL-1 gene (X79778). The constitutively expressed M. truncatula elongation factor gene (MtEF1α; EF1a [5′-AGTCTCTCTCTGCGGCTGAG-3′] and EF1b [5′-CGATTTCATCGTACCTAGCCTT-3′]) was used in control amplifications. Twenty-five cycles of PCR (94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s) were carried out for MtEF1α and 30 cycles for other genes. Amplification products were analyzed using 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Segregation Analysis

For the segregation analysis, we used primers NSP2-5′ (5′-CCGGCAGGCGATTAACCTCCTT-3′), NSP2-3′ (5′-GCATCCTATAAATCAGAATCTGAA-3′), and MERE1 (5′-AGCCCTTTTGTCAAACATGTATTA-3′). Thirty cycles of PCR were carried out at 94°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s. Amplification products were analyzed using 0.7% agarose gel electrophoresis.

DNA Methylation Analysis

gDNA was extracted from 2HA leaf explants after 0, 4, 7, and 14 d of in vitro culture on SH3a medium. Two micrograms of each DNA sample was subjected to bisulfite treatment using the EpiTect Bisulfite Modification Kit (Qiagen), which includes a DNA protective buffer.

Primers were designed using the MethPrimer Web site (http://www.urogene.org/methprimer/index.html).

The Bi1 (5′-TAACAACTAAAATTAACAAAATAAAAAA-3′) and Bi2 (5′-GAATGAAAAGTTGGATTTTTTGTAA-3′) primers amplified the converted (+)DNA strands corresponding to MERE1 positions from 4,462 to 4,687 bp. Three aliquots of 2 μL of converted DNA were prepared for each time point. In addition to the DNA samples, controls of gDNA without bisulfite conversion and template-free controls (“no-template control”) were prepared in parallel. Amplification could not be detected on nonconverted DNA using Bi1 and Bi2 primers. Primers BiWT1 (5′-TAGCAACTGGAGTTGGCAAGGTAGAGAG-3′) and BiWT2 (5′-GAATGAAAAGCTGGATTCCTTGCAA-3′) were designed to amplify the nonconverted sequences. Using these primers, we obtained PCR products on nonconverted DNA but no products on bisulfite-converted DNA. PCR (94°C for 2 min, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, 35 cycles) was performed according to the supplier with 0.4 units of Taq polymerase (Eurobio). PCR products for each time point were pooled and cloned in the pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega). For each time point, between 18 and 21 sequences were analyzed between base pairs 4,462 and 4,687 of the MERE1 sequence.

Bioinformatics Analysis

Sequences were analyzed by BLAST (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/), BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor (1997–2007; Tom Hall), and Multalin (http://bioinfo.genopole-toulouse.prd.fr/multalin/multalin.html). The alignments of the GAG-POL regions were conducted using ClustalX (Thompson et al., 1997). Relationship tree building was conducted using MEGA version 4 (Tamura et al., 2007).

FST sequences were generated in the framework of the EU-GLIP program by the Genoscope (www.genoscope.cns.fr) and analyzed using the program WebLOGO 3.0 (http://weblogo.threeplusone.com/).

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers FI495319 to FI495418 for the FSTs. Other accession numbers are as follows: MERE1-1-J5, FJ544851; MERE1-2-J5, FJ544852; MERE1-3-J5, FJ544853; MERE1-4-J5, FJ544854; MERE1-5-J5, FJ544855; MERE1-1-R108-1, FJ544856; MERE1-LIKE-1, FJ544857; and MERE1-LIKE-2, FJ544858. Tnt1 FSTs sequences were deposited at http://bioinfo4.noble.org/mutant/

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. RT-PCR analysis of nodulin gene expression in the wild type and ms219 after infection by S. meliloti.

Supplemental Figure S2. Evolutionary relationships of MERE1 LTRs and related solo LTRs.

Supplemental Figure S3. Evolutionary relationships of 155 copia-related retroelements.

Supplemental Figure S4. Methylation status at the MERE1 locus.

Supplemental Table S1. Sequences of genetic markers on linkage groups 1, 3, and 5.

Supplemental Table S2. MERE1-1 is the only member of the MERE1 family with all requirements for transposition.

Supplemental Table S3. Base composition of MERE1-1 insertion sites.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Valérie Geffroy and Gabriella Endre for kind help in the marker design and analysis of results. We are very grateful to Lene Heegaard Madsen and Jens Stougaard, who provided us with gDNA of the progeny of transgenic L. japonicus plants. Thanks to Peter Kalo and Giles Oldroyd, who provided us with the nsp2-1 mutant. Thanks to Pavel Neumann and Jiri Macas for the sequence data of the plant copia elements. We are grateful to Drs. M. Schultze, R. Benlloch, and M.A. Grandbastien for careful reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a fellowship from the French Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, to A.R., by the Grain Legumes Integrated Project (grant no. FOOD–CT–2004–506223 to L.B. and A.C.), and by a UNESCO-L'OREAL-cosponsored Fellowship for Young Women in Life Science-2006 to G.A.A.E.-H.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantphysiol.org) is: Pascal Ratet (pascal.ratet@isv.cnrs-gif.fr).

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

References

- Amor BB, Shaw SL, Oldroyd GE, Maillet F, Penmetsa RV, Cook D, Long SR, Denarie J, Gough C (2003) The NFP locus of Medicago truncatula controls an early step of Nod factor signal transduction upstream of a rapid calcium flux and root hair deformation. Plant J 34 495–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo PG, Casacuberta JM, Costa AP, Hashimoto RY, Grandbastien MA, Van Sluys MA (2001) Retrolyc1 subfamilies defined by different U3 LTR regulatory regions in the Lycopersicon genus. Mol Genet Genomics 266 35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beguiristain T, Grandbastien MA, Puigdomenech P, Casacuberta JM (2001) Three Tnt1 subfamilies show different stress-associated patterns of expression in tobacco: consequences for retrotransposon control and evolution in plants. Plant Physiol 127 212–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocard L, Schultze M, Kondorosi A, Ratet P (2006) T-DNA mutagenesis in the model plant Medicago truncatula: is it efficient enough for legume molecular genetics? CAB Reviews: Perspectives in Agriculture, Veterinary Science, Nutrition and Natural Resources 1: 7 pp

- Casacuberta JM, Grandbastien MA (1993) Characterisation of LTR sequences involved in the protoplast specific expression of the tobacco Tnt1 retrotransposon. Nucleic Acids Res 21 2087–2093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catoira R, Galera C, de Billy F, Penmetsa RV, Journet EP, Maillet F, Rosenberg C, Cook D, Gough C, Denarie J (2000) Four genes of Medicago truncatula controlling components of a nod factor transduction pathway. Plant Cell 12 1647–1666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C, Daigen M, Hirochika H (2006) Epigenetic regulation of the rice retrotransposon Tos17. Mol Genet Genomics 276 378–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church GM, Gilbert W (1984) Genomic sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81 1991–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D, Dreyer D, Bonnet D, Howell M, Nony E, VandenBosch K (1995) Transient induction of a peroxidase gene in Medicago truncatula precedes infection by Rhizobium meliloti. Plant Cell 7 43–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosson V, Durand P, d'Erfurth I, Kondorosi A, Ratet P (2006) Medicago truncatula transformation using leaf explants. Methods Mol Biol 343 115–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Erfurth I, Cosson V, Eschstruth A, Lucas H, Kondorosi A, Ratet P (2003) Efficient transposition of the Tnt1 tobacco retrotransposon in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant J 34 95–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt DW, Atkinson EM, Long SR (1992) Depolarization of alfalfa root hair membrane potential by Rhizobium meliloti Nod factors. Science 256 998–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickbush DG, Ye J, Zhang X, Burke WD, Eickbush TH (2008) Epigenetic regulation of retrotransposons within the nucleolus of Drosophila. Mol Cell Biol 28 6452–6461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommer M, McDonald LE, Millar DS, Collis CM, Watt F, Grigg GW, Molloy PL, Paul CL (1992) A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89 1827–1831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto R, Sasaki T, Inoue H, Nishio T (2008) Hypomethylation and transcriptional reactivation of retrotransposon-like sequences in ddm1 transgenic plants of Brassica rapa. Plant Mol Biol 66 463–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukai E, Dobrowolska AD, Madsen LH, Madsen EB, Umehara Y, Kouchi H, Hirochika H, Stougaard J (2008) Transposition of a 600 thousand-year-old LTR retrotransposon in the model legume Lotus japonicus. Plant Mol Biol 68 653–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galibert F, Finan TM, Long SR, Puhler A, Abola P, Ampe F, Barloy-Hubler F, Barnett MJ, Becker A, Boistard P, et al (2001) The composite genome of the legume symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. Science 293 668–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel DJ, Nyswaner K, Wang J, Cho JY (2003) Post-transcriptional cosuppression of Ty1 retrotransposition. Genetics 165 83–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandbastien MA, Audeon C, Casacuberta JM, Grappin P, Lucas H, Moreau C, Pouteau S (1994) Functional analysis of the tobacco Tnt1 retrotransposon. Genetica 93 181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandbastien MA, Lucas H, Morel JB, Mhiri C, Vernhettes S, Casacuberta JM (1997) The expression of the tobacco Tnt1 retrotransposon is linked to plant defense responses. Genetica 100 241–252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandbastien MA, Spielmann A, Caboche M (1989) Tnt1, a mobile retroviral-like transposable element of tobacco isolated by plant cell genetics. Nature 337 376–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirochika H (1993) Activation of tobacco retrotransposons during tissue culture. EMBO J 12 2521–2528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirochika H (1997) Retrotransposons of rice: their regulation and use for genome analysis. Plant Mol Biol 35 231–240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirochika H, Okamoto H, Kakutani T (2000) Silencing of retrotransposons in Arabidopsis and reactivation by the ddm1 mutation. Plant Cell 12 357–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirochika H, Sugimoto K, Otsuki Y, Tsugawa H, Kanda M (1996) Retrotransposons of rice involved in mutations induced by tissue culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93 7783–7788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood E, Gelvin S, Melchers L, Hoekema A (1993) New Agrobacterium helper plasmids for gene transfer to plants. Transgenic Res 2 208–218 [Google Scholar]

- Iantcheva A, Chabaud M, Cosson V, Barascud M, Schutz B, Primard-Brisset C, Durand P, Barker DG, Vlahova M, Ratet P (2009) Osmotic shock improves Tnt1 transposition frequency in Medicago truncatula cv Jemalong during in vitro regeneration. Plant Cell Rep (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Journet EP, El-Gachtouli N, Vernoud V, de Billy F, Pichon M, Dedieu A, Arnould C, Morandi D, Barker DG, Gianinazzi-Pearson V (2001) Medicago truncatula ENOD11: a novel RPRP-encoding early nodulin gene expressed during mycorrhization in arbuscule-containing cells. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14 737–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Journet EP, Pichon M, Dedieu A, de Billy F, Truchet G, Barker DG (1994) Rhizobium meliloti Nod factors elicit cell-specific transcription of the ENOD12 gene in transgenic alfalfa. Plant J 6 241–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeppler SM, Phillips RL (1993) Tissue culture-induced DNA methylation variation in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90 8773–8776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalo P, Gleason C, Edwards A, Marsh J, Mitra RM, Hirsch S, Jakab J, Sims S, Long SR, Rogers J, et al (2005) Nodulation signaling in legumes requires NSP2, a member of the GRAS family of transcriptional regulators. Science 308 1786–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay R, Chan A, Daly M, McPherson J (1987) Duplication of CaMV 35S promoter sequences creates a strong enhancer for plant genes. Science 236 1299–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Bennetzen JL (1999) Plant retrotransposons. Annu Rev Genet 33 479–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lall IP, Maneesha, Upadhyaya KC (2002) Panzee, a copia-like retrotransposon from the grain legume, pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L.). Mol Genet Genomics 267 271–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LC, Dahiya R (2002) MethPrimer: designing primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics 18 1427–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZL, Han FP, Tan M, Shan XH, Dong YZ, Wang XZ, Fedak G, Hao S, Liu B (2004) Activation of a rice endogenous retrotransposon Tos17 in tissue culture is accompanied by cytosine demethylation and causes heritable alteration in methylation pattern of flanking genomic regions. Theor Appl Genet 109 200–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen LH, Fukai E, Radutoiu S, Yost CK, Sandal N, Schauser L, Stougaard J (2005) LORE1, an active low-copy-number TY3-gypsy retrotransposon family in the model legume Lotus japonicus. Plant J 44 372–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonhaute C, Ogereau D, Hua-Van A, Capy P (2007) Amplification of the 1731 LTR retrotransposon in Drosophila melanogaster cultured cells: origin of neocopies and impact on the genome. Gene 393 116–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen RA, Colot V (2001) DNA methylation and epigenetic inheritance in plants and filamentous fungi. Science 293 1070–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattanovich D, Ruker F, Machado AC, Laimer M, Regner F, Steinkellner H, Himmler G, Katinger H (1989) Efficient transformation of Agrobacterium spp. by electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res 17 6747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melayah D, Bonnivard E, Chalhoub B, Audeon C, Grandbastien MA (2001) The mobility of the tobacco Tnt1 retrotransposon correlates with its transcriptional activation by fungal factors. Plant J 28 159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhiri C, Morel JB, Vernhettes S, Casacuberta JM, Lucas H, Grandbastien MA (1997) The promoter of the tobacco Tnt1 retrotransposon is induced by wounding and by abiotic stress. Plant Mol Biol 33 257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyao A, Tanaka K, Murata K, Sawaki H, Takeda S, Abe K, Shinozuka Y, Onosato K, Hirochika H (2003) Target site specificity of the Tos17 retrotransposon shows a preference for insertion within genes and against insertion in retrotransposon-rich regions of the genome. Plant Cell 15 1771–1780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayashiki H, Ikeda K, Hashimoto Y, Tosa Y, Mayama S (2001) Methylation is not the main force repressing the retrotransposon MAGGY in Magnaporthe grisea. Nucleic Acids Res 29 1278–1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan T, Braccini L, Azzalin G, De Toni A, Macino G, Cogoni C (2005) The post-transcriptional gene silencing machinery functions independently of DNA methylation to repress a LINE1-like retrotransposon in Neurospora crassa. Nucleic Acids Res 33 1564–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez -Hormaeche J, Potet F, Beauclair L, Le Masson I, Courtial B, Bouche N, Lucas H (2008) Invasion of the Arabidopsis genome by the tobacco retrotransposon Tnt1 is controlled by reversible transcriptional gene silencing. Plant Physiol 147 1264–1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quemada H, Roth EJ, Lark KG (1987) Changes in methylation of tissue cultured soybean cells detected by digestion with the restriction enzymes HpaII and MspI. Plant Cell Rep 6 63–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowicz PD, Palmer LE, May BP, Hemann MT, Lowe SW, McCombie WR, Martienssen RA (2003) Genes and transposons are differentially methylated in plants, but not in mammals. Genome Res 13 2658–2664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinders J, Delucinge Vivier C, Theiler G, Chollet D, Descombes P, Paszkowski J (2008) Genome-wide, high-resolution DNA methylation profiling using bisulfite-mediated cytosine conversion. Genome Res 18 469–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribet D, Dewannieux M, Heidmann T (2004) An active murine transposon family pair: retrotransposition of “master” MusD copies and ETn trans-mobilization. Genome Res 14 2261–2267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronfort J, Bataillon T, Santoni S, Delalande M, David JL, Prosperi JM (2006) Microsatellite diversity and broad scale geographic structure in a model legume: building a set of nested core collection for studying naturally occurring variation in Medicago truncatula. BMC Plant Biol 6 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose R, Nolan K, Bicego L (1999) The development of the highly regenerative seed line Jemalong 2 HA for transformation of Medicago truncatula: implications for regenerability via somatic embryogenesis. J Plant Physiol 155 788–791 [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EJ, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

- Scholte M, d'Erfurth I, Rippa S, Mondy S, Cosson V, Durand P, Breda C, Trinh H, Rodriguez-Llorente I, Kondorosi E, et al (2002) T-DNA tagging in the model legume Medicago truncatula allows efficient gene discovery. Mol Breed 10 203–215 [Google Scholar]

- Szybiak-Strozycka U, Lescure N, Cullimore JV, Gamas P (1995) A cDNA encoding a PR-1-like protein in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol 107 273–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadege M, Wen J, He J, Tu H, Kwak Y, Eschstruth A, Cayrel A, Endre G, Zhao PX, Chabaud M, et al (2008) Large-scale insertional mutagenesis using the Tnt1 retrotransposon in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant J 54 335–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S, Sugimoto K, Otsuki H, Hirochika H (1999) A 13-bp cis-regulatory element in the LTR promoter of the tobacco retrotransposon Tto1 is involved in responsiveness to tissue culture, wounding, methyl jasmonate and fungal elicitors. Plant J 18 383–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S (2007) MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 24 1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG (1997) The CLUSTAL_X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 25 4876–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh T, Ratet P, Kondorosi E, Durand P, Kamaté K, Bauer P, Kondorosi A (1998) Rapid and efficient transformation of diploid Medicago truncatula and Medicago sativa ssp. facata in vitro lines improved in somatic embryogenesis. Plant Cell Rep 17 345–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyushin BF (2006) DNA methylation in plants. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 301 67–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdier J, Kakar K, Gallardo K, Le Signor C, Aubert G, Schlereth A, Town CD, Udvardi MK, Thompson RD (2008) Gene expression profiling of M. truncatula transcription factors identifies putative regulators of grain legume seed filling. Plant Mol Biol 67 567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernhettes S, Grandbastien MA, Casacuberta JM (1997) In vivo characterization of transcriptional regulatory sequences involved in the defence-associated expression of the tobacco retrotransposon Tnt1. Plant Mol Biol 35 673–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Liu JS (2008) LTR retrotransposon landscape in Medicago truncatula: more rapid removal than in rice. BMC Genomics 9 382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessler SR, Bureau TE, White SE (1995) LTR-retrotransposons and MITEs: important players in the evolution of plant genomes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 5 814–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.