Abstract

Objective

The Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor-gamma (PPARγ) protein is a nuclear transcriptional activator with importance in diabetes management as the molecular target for the thiazolidinedione (TZD) family of drugs. Substantial evidence indicates that the TZD family of PPARγ agonists may retard the development of atherosclerosis. However, recent clinical data has suggested that at least one TZD may increase the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular disease. In this study, we used a genetic approach to disrupt PPARγ signaling to probe the protein's role in smooth muscle cell (SMC) responses that are important for atherosclerosis.

Results/Methods

SMC isolated from transgenic mice harboring the dominate-negative P465L mutation in PPARγ (PPARγL/+) exhibited greater proliferation and migration then did wild-type cells. Upregulation of ETS-1, but not ERK activation, correlated with enhanced proliferative and migratory responses PPARγL/+ SMCs. Following arterial injury, PPARγL/+ mice had a ~ 4.3-fold increase in the development of intimal hyperplasia.

Conclusion

These findings are consistent with a normal role for PPARγ in inhibiting SMC migration and proliferation in the context of restenosis or atherosclerosis.

INTRODUCTION

PPARγ, a dynamic nuclear transcriptional regulator, has well characterized roles in adipocyte differentiation1, lipid metabolism2 and insulin sensitivity3, 4. Clinically PPARγ is the molecular target of the insulin sensitizing thiazolidinedione (TZD) class of drugs that includes rosiglitazone and pioglitazone5. TZD 6 and other PPARγ agonists 7 effectively increase insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Many preclinical and clinical studies have suggested that PPARγ agonists protect against the development of atherosclerosis 8–11 and reduce the development of intimal hyperplasia9, 12–14. In the PROACTIVE trial, the PPARγ agonist pioglitazone had beneficial effects on the combined secondary endpoints of myocardial infarction, stroke and death15. However a recent meta-analysis suggested that the use of the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone for the treatment of diabetes was associated with an increase in risk of myocardial infarction and a trend towards a higher risk of cardiovascular death 16. Endogenous ligands for PPARγ include unsaturated and oxidized fatty acids, eicosanoids, prostaglandins and possibly lysophospholipids. The putative PPARγ agonist lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) accelerates neointimal formation after vessel injury in rodents in a PPARγ-dependent manner17, suggesting that activation of PPARγ may promote the development of intimal hyperplasia. However, at present, the role that PPARγ plays in regulating vascular responses that underlie atherosclerosis and restenosis remain incompletely understood.

Proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) are key events in the development of intimal hyperplasia that occurs in the context of atherosclerosis and restenosis18 . PPARγ is present in vascular SMCs19, and the atheroprotective effects of PPARγ ligands have been proposed to relate in part to beneficial effects on SMC biology. Indeed, studies have shown that TZDs inhibit vascular SMC proliferation 12, 13 and migration 12, 13, 20, while increasing apoptosis21. It is not clear whether this is a direct effect of TZDs on PPARγ or an “off-target” effect of the drugs, as most studies have inferred a role for PPARγ in atherosclerosis on the basis of results with pharmacologic interventions. Homozygous deficiency of PPARγ is embryonic lethal 1. Atherosclerosis and the development of intimal hyperplasia in a vascular SMC-specific PPARγ knock-out mouse have not been reported. However, there is genetic evidence to support a role for PPARγ in SMC biology. For example, a generalized PPARγ knock-out model was created by breeding floxed PPARγ mice to Mox2-Cre mice to inactivate PPARγ in the embryo but not in trophoblasts 22. The resulting mice have hypotension and impaired SMC contraction. PPARγ variants with dominant negative function have been documented in families of humans with insulin resistance, type II diabetes and hypertension. Dominant negative loss-of-function PPARγ mutations have also been introduced into mice to phenocopy abnormalities identified in humans. In humans, the substitution of a leucine for proline at amino acid 465 (P465L) is associated with severe insulin-resistance and significantly reduced PPARγ activity 23. The homologous mutation in mice, P467L, causes hypertension, abnormal fat distribution but not insulin resistance 24, and cerebral vascular dysfunction 25. Thus, mice with the PPARγ-P465L mutation (PPARγL/+ mice) may be a useful model to examine the role of PPARγ signaling in SMC function.

In the present study, we examined the response of primary cultures of SMCs obtained from aortas of mice harboring the PPARγL/+ mutation or sibling controls. We report increases in proliferation and migration that translated into enhanced neointimal hyperplasia following vascular injury in vivo.

METHODS

Animals

The generation and genotyping of 129/SvEv mice containing the P465L mutation in PPARγ (PPARγL/+) mutation has been previously described 24, 25. To minimize background-specific effects, the PPARγL/+ mice on the 129/SvEv background were crossed with female C57BL/6J mice from Jackson laboratories to generate F1 mice with the same complement of genes varying only in the presence (PPARγL/+) or absence (PPARγ+/+) of the P465L mutation. Carotid ligation was performed in eight week old wild type PPARγ+/+ and PPARL/+ sibling matched mice and analyzed as previously described 26, 27. Carotid arteries were stained with combined Mason's Trichrome and elastin stain. Serial sections taken at 0.4 mm intervals from the ligation for histomorphometric analysis.

Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells

Aortas from sibling-paired mice aged 4 and 6 weeks old were digested in collagenase (175 U/ml; Worthington, NJ) and then adventitial tissue removed with by gentle tractios using forceps. The adventitia-free aorta was incubated overnight in a Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), and then digested with elastase (concentration 0.25mg/ml, Sigma, MO) and collagenase (175 U/ml) in Hank's Balanced Salt Solution to generate isolated cells. Cells were cultured in DMEM containing 0.5 ng/ml EGF, 5 μg/ml insulin, 2 ng/ml bFGF, 10%FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. SMCs were isolated from endothelial cells by magnetic bead separation system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and cell purity verified by SM α-actin staining.

For proliferation assays, cells at 70% confluence were serum starved in a 0.1% FBS for 72 hours and then plated at a concentration of 5,000 cells/well on a 96-well plate. Cells were treated with 0.1% BSA in PBS (vehicle), 20 ng/ml mouse platelet derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB,Ray Biotech, GA), or 10% FBS. The number of viable cells was quantified after 24, 48, 72, and 96 through incubation for 2 hours in a WST-1 solution (Biochain, CA). WST-1 is cleaved by mitochondrial succinate-tetrazolium reductase in viable cells to form formazan dye. The amount of formazan is proportional to the number of viable cells. After 2 hours of incubation in WST-1, absorbance at 450 nm was measured. For ERK activity, cells were washed with ice cold PBS and lysed (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.2, 1% Nonidet P-40, 158 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate). Total protein in clarified cell lysates (16,000g × 10 min) was determined (BCA protein assay; Pierce, Rockford, IL) and equal amounts loaded onto 10% SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting was performed with antibodies to actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), ERK/phospho-ERK Thr202/Tyr204, and ETS-1 (Santa Cruz) and quantified using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). Equal sample loading was confirmed by Coomassie blue staining.

In the scratch migration assays, cells were grown to confluence and then serum starved for 72 hours at which time a 400 μm scratch was placed through the confluent layer of cells using the end of a 200 μl pipette tip. After 12 hours, migration into the scratch was imaged through phase contrast microscopy with a Leica DM IRB inverted microscope. Cells in at least three fields were manually counted and the area occupied measured with NIH Image J software. In separate experiments, chemotactic migration was assessed by placing serum starved cells (1.8 × 104 cells/well) in the upper well of a chamber of a multiwellchambers (Neuroprobe Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) with a polyvinylpyrrolidone-free polycarbonate filter (5 μm pore). The bottom chamber was filled with DMEM containing 0.1% FBS and the indicated chemotactic agent (1 μM LPA [18:1 LPA in 0.1% BSA; Avanti Polar Lipids], 10% FBS, 20 ng/ml PDGF) or vehicle. The chamber was incubated for 12-h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator, at which time the filter was removed from the chamber and the non-migrated cells were scraped from the upper surface. The membranes were fixed, and the migrated cells stained with Diff-Quik® (VWR Scientific Products, West Chester, PA). Digital images of the membranes were obtained with a Nikon 80i microscope using a 20× objective (NA = 0.5). The total area (μm2) occupied by migrated cells was determined with Metamorph imaging software.

For siRNA experiments, SMCs were placed in serum and antibiotic-free medium (10% (v/v) FBS in DMEM) at least 2 h before transfection and incubated with approximately 100nM of siRNA oligonucleotides to ETS-1 and scrambled control (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) and 1μl/cm2 plate of X- tremeGENE siRNA Transfection Reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). siGLO Green Transfection Indicator was used as a qualitative indicator of delivery. After 24 hours, the medium was changed to low or high glucose DMEM medium containing antibiotics (10% (v/v) FBS, 1% (m/v) penicillin and streptomycin and the chemotactic migration assay was performed as described above.

Statistical analysis

In vitro experiments were performed a minimum of three times with cells prepared from at least three different cohorts of animals. All results were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (se). All data was analyzed using non-paired t-test or ANOVA, where indicated, using Sigma-STAT software, version 3.5 (Systat Software, Inc. San Jose, CA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

PPARγL/+ vascular smooth muscle cells exhibit enhanced proliferation and migration

A key element in the development of neointima is the proliferation and migration of SMCs from the vessel media to intima. Studies using synthetic PPARγ agonists such as TZDs have identified a potential role for PPARγ as a regulator of SMC proliferation and migration. To probe the normal role of PPARγ in SMC responses, we employed a genetic strategy in which PPARγ activity was attenuated by the introduction of a dominant-negative PPARγ mutation in mice. SMCs were isolated from aortas of wild-type mice or heterozygous knock-in mice carrying the dominant negative P465L mutation in PPARγ (PPARγL/+) and their proliferative properties examined. PPARγL/+ SMCs displayed a modest 1.6-fold increase in proliferation in response to 10% FBS as compared to wild-type PPARγ+/+cells at 72 hours (P = 0.003; Supplemental Figure 1). The enhanced proliferation was not observed in vehicle-treated PPARγL/+ cells or in the presence of PDGF (Supplemental Figure 1).

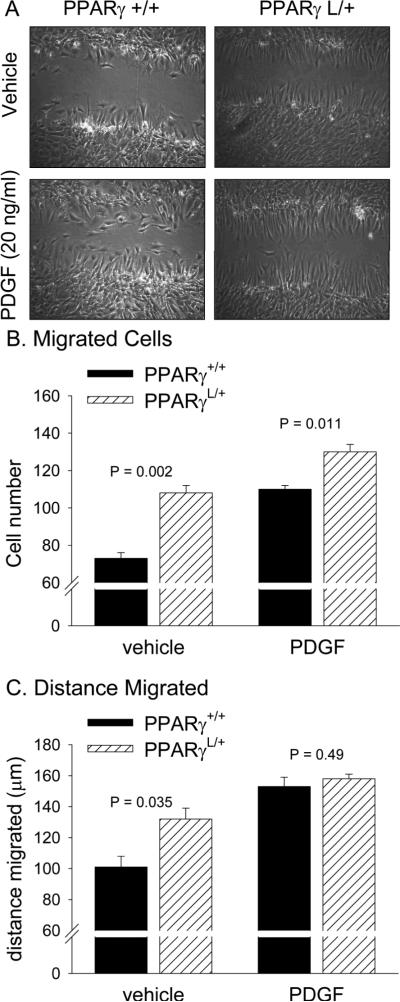

PPARγL/+ SMCs also displayed enhanced wound closure in a scratch assay (Figure 1A). Twelve hours after a single scratch injury, significantly more PPARγL/+ SMCs migrated into the wound (108±4 PPARγL/+ cells versus 73±3 wild-type PPARγ+/+ cells, P = 0.002, Figure 1B) and they migrated a greater distance (132±7 μm for PPARγL/+ cells compared 101±7 μm for PPARγ+/+ cells; P = 0.035; Figure 2C). PDGF (20 ng/ml) increased the number of PPARγ+/+ cells and the distance they migrated and nearly rescued the defect in the PPARγL/+ cells. In the presence of PDGF, 130±4 PPARγL/+ cells and 110±2 PPARγ+/+ cells (P = 0.011) migrated a distance of 158±3 μm and 153±6 μm (P = 0.49), respectively (Figure 2C).

Figure 1. Enhanced wound closure in PPARγL/+ aortic SMC.

SMCs were grown to confluence, serum starved, and then a 400 μm scratch was made through the lawn of confluent cells. After 12 hours, the region containing the scratch was imaged. The number of migrated cells was measured from digital images (A). Significantly more PPARγ L/+ SMCs migrated into the scratch (P = 0.002). The addition of PDGF to the media after scratch injury increased numbers of both PPARγ +/+ and PPARγ L/+ SMCs in the wound at 12 hours. (B): PPARγ L/+ cells migrated further into the wound than did PPARγ +/+ cells in the absence (P = 0.035) but not the presence of PDGF (P = 0.49). Values are presented as mean ± se.

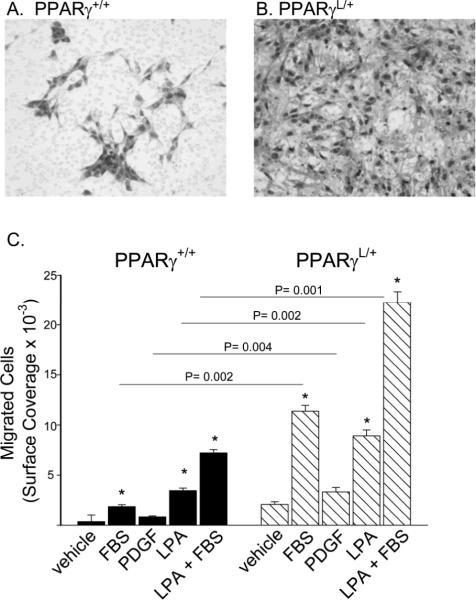

Figure 2. Enhanced migration in PPARγL/+ SMC.

SMCs were stained with Diff-Quik® on the undersurface of a membrane with a 5 μm pore following migration to media containing vehicle, 10% FBS, 20 ng/ml PDGF, or 1 μM LPA. Representative images of migrated PPARγ +/+ SMCs (A) and PPARγ L/+ SMCs (B). The area occupied by migrated cells is presented as mean ± se (C). Combined results from three experiments are shown. *P<0.05 versus vehicle treatment by ANOVA. Values are presented as mean ± se.

The behavior of wild-type PPARγ+/+ (Figure 2A) and mutant PPARγL/+ (Figure 2B) cells was also measured in a chemotactic assay in which the cells migrated towards a gradient of FBS, PDGF, or lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), which, in addition to its well-described actions at cell surface receptors, has been proposed to also serve as a PPARγ agonist 28. In wild-type PPARγ+/+ cells, migration increased 5.2 fold in the presence of FBS and 10-fold with LPA, whereas migration increased ~20 fold with the combination of FBS and LPA (Figure 2C). In comparison to wild-type cells, the migration of PPARγL/+ cells was 6.1-fold higher towards FBS (P= 0.002, by ANOVA), 4-fold higher to PDGF (P= 0.004 by ANOVA), and 2.6-fold higher to LPA (P = 0.002 by ANOVA).

Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways involving ERK contribute to SMC proliferative and migratory responses. We previously reported that SMC migration to FBS and LPA requires ERK activity 27. In keeping with these observations, the MEK1 inhibitor PD 98059 reduced chemotactic migration of wild-type PPARγ+/+ and PPARγL/+ SMCs by 62% and 58%, respectively (Supplemental Figure 1). In addition, the TZDs rosiglitazone and pioglitazone inhibited wild-type PPARγ+/+ cell migration by ~50% and 40%. Interestingly, rosiglitazone but not pioglitazone partially blocked PPARγL/+ cell migration by ~40% (Supplemental Figure 1).

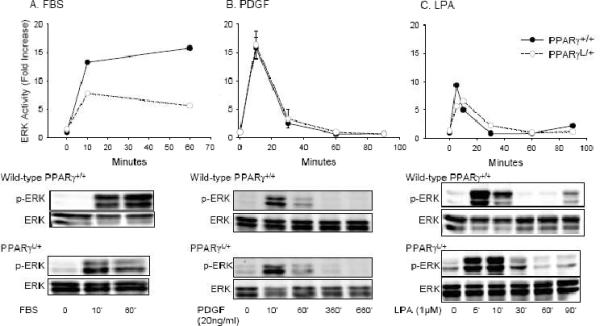

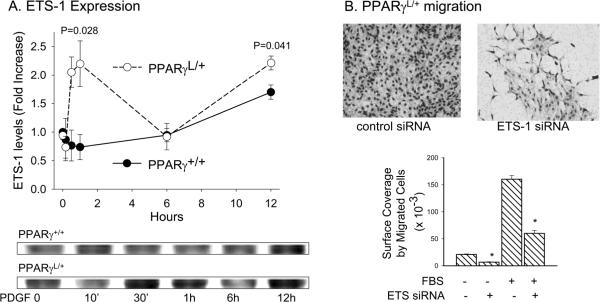

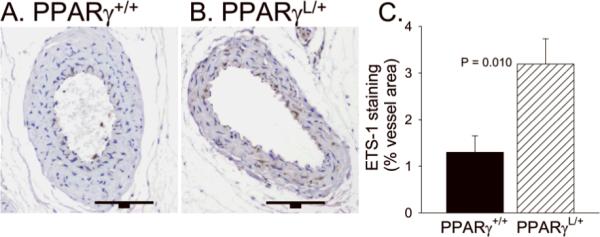

TZDs have been variably proposed to alter ERK activity in SMCs, with some studies suggesting a role for TZDs in regulating cytosolic ERK 29 and other studies showing an effect downstream of cytosolic ERK 30, 31. Therefore, we examined the effects of the PPARγ P465L mutation on ERK activation in SMC. In wild-type PPARγ+/+ cells, FBS elicited an increase in ERK activity at 10 min that persisted for 60 min (Figure 3A). PDGF also increased ERK activity rapidly and resulted in a slight, but sustained elevation in ERK activity at 6 hours (Figure 4B). LPA stimulated a rapid increase in ERK phosphorylation that was maximal at 5 – 10 min (Figure 3C) and a second phase of late ERK activation. Biphasic ERK activation also occurs in thrombin stimulated SMC, where the second phase of ERK activation is triggered by HB-EGF expression32. No substantial differences were observed in ERK activation in mutant PPARγL/+ cells in response to FBS (Figure 4A), PDGF (Figure 3B), or LPA (Figure 3C). Based on these results, the enhanced migration observed in the presence of the PPARγ dominant negative mutation is unlikely to be the result of increased ERK activity. Others have reported that PPARγ agonists prevent SMC migration by acting downstream of ERK to block expression of ETS-1 31. ETS-1 also regulates the ability of PPARγ agonists to inhibit telomerase activity in SMC 33. We therefore examined the effects of the dominant-negative PPARγ P465L mutation on ETS-1. Following stimulation with FBS or PDGF, PPARγL/+ cells upregulated ETS-1 to a significantly greater extent at earlier (~ 1 hour; P= 0.028) and later (~12 hours; P= 0.041) time points than did PPARγ+/+ cells (Figure 4A). Moreover, down regulation of ETS1 using RNA-dependent gene silencing (siRNA) blunted the enhanced PPARγL/+ cell migration (Figure 4B)

Figure 3. Normal ERK activation in PPARγL/+ SMC.

Time course of activation of ERK, as measured by phosphoERK/total ERK ratios, in cells following exposure to 10% FBS (A), 20 ng/ml PDGF (B), or 1 μM LPA (C). Results are presented as mean ± se and representative of three experiments with independent cultures of SMCs of each genotype.

Figure 4. Alterations in ETS-1 in PPARγL/+ SMC may account for enhanced migration.

(A) Time course of effects of 20 ng/ml PDGF on ETS-1 levels. Results are presented as mean ± se and are representative of three experiments. (B) Migration of PPARγ L/+ was performed 72h after transfection with scrambled control siRNA or siRNA to ETS-1. Images are representative of results obtained in three experiments. Results are graphed as mean ± sd. * P <0.05.

PPARγL/+ mice show increased neointimal formation during vascular remodeling

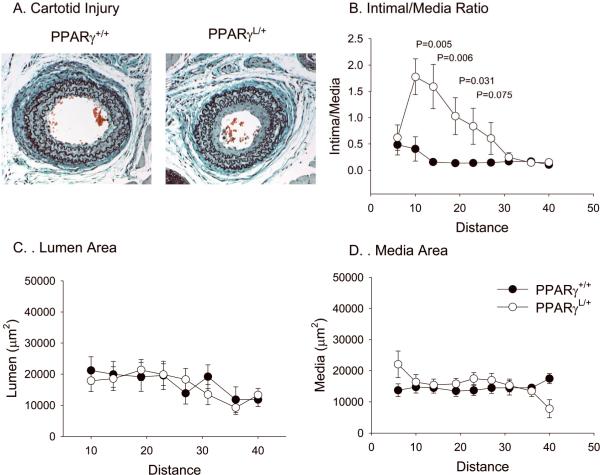

To determine if the enhanced SMC proliferation and migration observed in PPARγL/+ SMC in culture also occurs in vivo, we examined the response to arterial injury in PPARγ+/+ and PPARγL/+ mice using a well-characterized mouse model in which robust development of intimal hyperplasia occurs 26. At four weeks following carotid injury, intimal hyperplasia develops along the length of the vessel (Figure 5A and B). In response to injury, PPARγL/+ mice develop more extensive neointima with a statistically greater intima/media ratio (Figure 5A and 5B; n = 8 PPARγ+/+, n = 9 PPARγL/+). At 10 mm from the ligation, the PPARγL/+ vessels display a 4.3 fold increase in neointima formation compared to the wild-type PPARγL/+ vessel (P = 0.005 by ANOVA). The difference in intima:media ratio persisted until 24 mm from the ligation (Figure 5B). No difference in lumen (P = 0.317; Figure 5C) or medial (P = 0.447; Figure 5D) areas were observed between mice of different genotypes. Consistent with the observations in isolated cells, ETS-1 expression was higher in PPARγL/+ vessels following injury (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Enhanced remodeling in PPARγL/+ mice in response to arterial injury.

Injured vessels were sectioned, imaged and measured with Image J to quantify vessel intima and media areas. Representative cross section of an injured PPARγ +/+ and PPARγ L/+ artery at 10 mm from the ligation (A). Intima to media ratios (B), lumen areas (C) and media areas (D) were calculated along the length of the vessel. Values are graphed as mean ± se.

Figure 6. Upregulation of ETS-1 expression in PPARγL/+ arteries after injury.

Immunohistochemistry for ETS-1 was performed on sections of injured vessels. Representative cross section of an injured PPARγ +/+ and PPARγ L/+ artery are presented. The bar is 100 μm. The average area of ETS-1 in 5 vessels of each genotype is graphed (mean ± se). *P <0.05

DISCUSSION

Studies in animal models have shown that PPARγ agonists inhibit atherosclerotic development 10. However, the precise role for PPARγ signaling in vascular SMCs remains unclear. In this report, we used a strain of mice harboring a dominant-negative acting PPARγ allele that suppresses endogenous PPARγ function24 to probe the normal role of PPARγ signaling in SMC phenotypic modulation that is important for atherosclerosis and restenosis. SMCs with the PPARγ P465L mutation display dramatically enhanced migration and a modest increase in proliferation in in vitro assays. These in vitro observations appear relevant in vivo because mice with the PPARγ P465L mutation exhibit exaggerated development of intimal hyperplasia following arterial injury. Upregulation of ETS-1 correlates with the enhanced migration in PPARγL/+ SMCs, and transient reduction of ETS-1 inhibited PPARγL/+ SMC migration. ETS-1 levels were also higher in PPARγL/+ arteries after injury. Our findings are consistent with previous demonstrations that ETS-1 mediates the effects of PPARγ agonists on migration31 and telomerase activity33. Interestingly, although ERK activation contributes to SMC migration, we did not observe substantial differences in ERK activation in WT and PPARγL/+ SMCs. Others have also suggested that the anti-migratory effects of TZDs occur down-stream of ERK 31.

Our results are consistent with a normal role for PPARγ in attenuating injury-induced SMC proliferation, migration, and vascular remodeling. Our findings are in agreement with previous studies documenting inhibition of neointimal formation by TZD agonists in animal models 34 and a slowing of progression of carotid intima-media thickness by TZDs in individuals with Type2 diabetes 35. The beneficial effects of TZDs in nondiabetic preclinical models and our results in nondiabetic mice suggest that the reduction in intimal hyperplasia associated with PPARγ activity is not simply a consequence of normalizing blood glucose and other metabolic abnormalities of diabetes. Because the PPARγ P465L mutation may affect signaling through other PPAR isoforms 9, we can not exclude a role of PPARα or PPARδ in regulating SMC responses. However our results, when considered in the context of the beneficial effects of TZDs, are most consistent with a central role of PPARγ in attenuating SMC proliferative and migratory responses in the context of vascular injury. While our results suggest a direct role for PPAR signaling in SMCs, effects in other vascular cells, such as monocytes and endothelial cells, may also indirectly influence SMC function following arterial injury. Together with published experiments using pharmacologic approaches, our observations in a genetic model of altered PPARγ activity support a role for endogenous PPARγ in modulating important pathophysiologic processes underlying restenosis and atherosclerosis.

Surprisingly, rosiglitazone but not pioglitazone was able to suppress migration and proliferation in cells from mice with the PPARγ P465L mutation. The lack of effect of pioglitazone was specific, in that under identical conditions, both pioglitazone and rosiglitazone inhibited wild-type SMC migration and proliferation. These findings would be consistent with rosiglitazone eliciting “off-target” effects that are not mediated by PPARγ. In this context it is interesting to note that clinical trials have tended to show a beneficial vascular effect of pioglitazone15 but not of rosiglitazone16. It is possible, however, that the PPARγL/+ cells have low levels of PPARγ activity that for unknown reasons are selectively enhanced by rosiglitazone but not pioglitazone.

Our findings are also relevant to the role of the lysolipid mediator LPA in regulating SMC responses. In addition to acting on G-protein coupled receptors, LPA has been proposed as an endogenous agonist of PPARγ28. In contrast to the inhibitory effects on the development of intimal hyperplasia reported with the TZD class of agonists, infusion of LPA into rodent carotid arteries has been associated with the formation of neointimal hyperplasia in a PPARγ-dependent manner17. We observed enhanced LPA-migration in SMC with the dominant-negative loss-of-function PPARγL/+ mutation, which appears to be non-selective with regards to agonists in that PPARγL/+ SMC migration to PDGF was also enhanced. Our results suggest that LPA-, FBS- and PDGF-promoted chemotactic migration of SMCs is normally inhibited by PPARγ-dependent pathways. Whether PPARγ mediates other effects of LPA on vascular SMC function or regulates the effects of endogenous LPA is not known.

In conclusion, our findings are consistent with a normal role for PPARγ in attenuating SMC migratory and proliferative properties which translate into beneficial vascular effects in terms of limiting the development of neointima. If future studies substantiate the initial reports of an association of at least one TZD with higher rates of adverse cardiovascular events, our results might suggest that the adverse cardiovascular profile for TZDs are due either to “off-target” effects or are the result of proatherothrombotic effects mediated by PPARγ agonism in other blood and vascular cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Kirk McNaughton and Alyssa Moore for excellent technical assistance.

Disclosures This work was supported by NIH grants HL078663and HL074219 to S.S.S. and DK67320 to NM. S.S.S. received Atorvastatin Research Award from Pfizer and previous grant funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

Reference List

- 1.Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, Koder A, Evans RM. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:585–595. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoonjans K, Peinado-Onsurbe J, Lefebvre AM, Heyman RA, Briggs M, Deeb S, Staels B, Auwerx J. PPARalpha and PPARgamma activators direct a distinct tissue-specific transcriptional response via a PPRE in the lipoprotein lipase gene. EMBO J. 1996;15:5336–5348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rangwala SM, Rhoades B, Shapiro JS, Rich AS, Kim JK, Shulman GI, Kaestner KH, Lazar MA. Genetic modulation of PPARgamma phosphorylation regulates insulin sensitivity. Dev Cell. 2003;5:657–663. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hevener AL, He W, Barak Y, Le J, Bandyopadhyay G, Olson P, Wilkes J, Evans RM, Olefsky J. Muscle-specific Pparg deletion causes insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2003;9:1491–1497. doi: 10.1038/nm956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehmann JM, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Wilkison WO, Willson TM, Kliewer SA. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12953–12956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolan JJ, Ludvik B, Beerdsen P, Joyce M, Olefsky J. Improvement in glucose tolerance and insulin resistance in obese subjects treated with troglitazone. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1188–1193. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411033311803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger J, Leibowitz MD, Doebber TW, Elbrecht A, Zhang B, Zhou G, Biswas C, Cullinan CA, Hayes NS, Li Y, Tanen M, Ventre J, Wu MS, Berger GD, Mosley R, Marquis R, Santini C, Sahoo SP, Tolman RL, Smith RG, Moller DE. Novel peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma and PPARdelta ligands produce distinct biological effects. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:6718–6725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chawla A, Boisvert WA, Lee CH, Laffitte BA, Barak Y, Joseph SB, Liao D, Nagy L, Edwards PA, Curtiss LK, Evans RM, Tontonoz P. A PPAR gamma-LXR-ABCA1 pathway in macrophages is involved in cholesterol efflux and atherogenesis. Mol Cell. 2001;7:161–171. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan SZ, Usher MG, Mortensen RM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-mediated effects in the vasculature. Circ Res. 2008;102:283–294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li AC, Brown KK, Silvestre MJ, Willson TM, Palinski W, Glass CK. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands inhibit development of atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:523–531. doi: 10.1172/JCI10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marfella R, D'Amico M, Esposito K, Baldi A, Di FC, Siniscalchi M, Sasso FC, Portoghese M, Cirillo F, Cacciapuoti F, Carbonara O, Crescenzi B, Baldi F, Ceriello A, Nicoletti GF, D'Andrea F, Verza M, Coppola L, Rossi F, Giugliano D. The ubiquitin-proteasome system and inflammatory activity in diabetic atherosclerotic plaques: effects of rosiglitazone treatment. Diabetes. 2006;55:622–632. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Law RE, Meehan WP, Xi XP, Graf K, Wuthrich DA, Coats W, Faxon D, Hsueh WA. Troglitazone inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell growth and intimal hyperplasia. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1897–1905. doi: 10.1172/JCI118991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law RE, Goetze S, Xi XP, Jackson S, Kawano Y, Demer L, Fishbein MC, Meehan WP, Hsueh WA. Expression and function of PPARgamma in rat and human vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2000;101:1311–1318. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.11.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minamikawa J, Tanaka S, Yamauchi M, Inoue D, Koshiyama H. Potent inhibitory effect of troglitazone on carotid arterial wall thickness in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1818–1820. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, Erdmann E, Massi-Benedetti M, Moules IK, Skene AM, Tan MH, Lefebvre PJ, Murray GD, Standl E, Wilcox RG, Wilhelmsen L, Betteridge J, Birkeland K, Golay A, Heine RJ, Koranyi L, Laakso M, Mokan M, Norkus A, Pirags V, Podar T, Scheen A, Scherbaum W, Schernthaner G, Schmitz O, Skrha J, Smith U, Taton J. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2457–2471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang C, Baker DL, Yasuda S, Makarova N, Balazs L, Johnson LR, Marathe GK, McIntyre TM, Xu Y, Prestwich GD, Byun HS, Bittman R, Tigyi G. Lysophosphatidic acid induces neointima formation through PPARgamma activation. J Exp Med. 2004;199:763–774. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362:801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marx N, Schonbeck U, Lazar MA, Libby P, Plutzky J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activators inhibit gene expression and migration in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1998;83:1097–1103. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.11.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruemmer D, Yin F, Liu J, Berger JP, Kiyono T, Chen J, Fleck E, Van Herle AJ, Forman BM, Law RE. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma inhibits expression of minichromosome maintenance proteins in vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1005–1018. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruemmer D, Yin F, Liu J, Berger JP, Sakai T, Blaschke F, Fleck E, Van Herle AJ, Forman BM, Law RE. Regulation of the growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene 45 (GADD45) by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2003;93:e38–e47. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000088344.15288.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan SZ, Ivashchenko CY, Whitesall SE, D'Alecy LG, Duquaine DC, Brosius FC, III, Gonzalez FJ, Vinson C, Pierre MA, Milstone DS, Mortensen RM. Hypotension, lipodystrophy, and insulin resistance in generalized PPARgamma-deficient mice rescued from embryonic lethality. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:812–822. doi: 10.1172/JCI28859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barroso I, Gurnell M, Crowley VE, Agostini M, Schwabe JW, Soos MA, Maslen GL, Williams TD, Lewis H, Schafer AJ, Chatterjee VK, O'Rahilly S. Dominant negative mutations in human PPARgamma associated with severe insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Nature. 1999;402:880–388. doi: 10.1038/47254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai YS, Kim HJ, Takahashi N, Kim HS, Hagaman JR, Kim JK, Maeda N. Hypertension and abnormal fat distribution but not insulin resistance in mice with P465L PPARgamma. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:240–249. doi: 10.1172/JCI20964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beyer AM, Baumbach GL, Halabi CM, Modrick ML, Lynch CM, Gerhold TD, Ghoneim SM, de Lange WJ, Keen HL, Tsai YS, Maeda N, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Interference with PPARgamma signaling causes cerebral vascular dysfunction, hypertrophy, and remodeling. Hypertension. 2008;51:867–871. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.103648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Lindner V. Remodeling with neointima formation in the mouse carotid artery after cessation of blood flow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2238–2244. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panchatcharam M, Miriyala S, Yang F, Rojas M, End C, Vallant C, Dong A, Lynch K, Chen J, Morris AJ, Smyth SS. Lysophosphatidic acid receptors 1 and 2 play roles in regulation of vascular injury responses, but not blood pressure. Circ Res. 2008;103 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.180778. ePrint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McIntyre TM, Pontsler AV, Silva AR, St HA, Xu Y, Hinshaw JC, Zimmerman GA, Hama K, Aoki J, Arai H, Prestwich GD. Identification of an intracellular receptor for lysophosphatidic acid (LPA): LPA is a transcellular PPARgamma agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:131–136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135855100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hattori Y, Akimoto K, Kasai K. The effects of thiazolidinediones on vascular smooth muscle cell activation by angiotensin II. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:1144–1149. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Game BA, Maldonado A, He L, Huang Y. Pioglitazone inhibits MMP-1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells through a mitogen-activated protein kinase-independent mechanism. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goetze S, Kintscher U, Kim S, Meehan WP, Kaneshiro K, Collins AR, Fleck E, Hsueh WA, Law RE. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligands inhibit nuclear but not cytosolic extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase-regulated steps in vascular smooth muscle cell migration. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2001;38:909–921. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200112000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sastre AP, Grossmann S, Reusch HP, Schaefer M. Requirement of an intermediate gene expression for biphasic ERK1/2 activation in thrombin-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25871–25978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800949200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogawa D, Nomiyama T, Nakamachi T, Heywood EB, Stone JF, Berger JP, Law RE, Bruemmer D. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma suppresses telomerase activity in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2006;98:e50–e59. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000218271.93076.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruemmer D, Law RE. Thiazolidinedione regulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Med. 2003;115(Suppl 8A):87S–92S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazzone T, Meyer PM, Feinstein SB, Davidson MH, Kondos GT, D'Agostino RB, Sr., Perez A, Provost JC, Haffner SM. Effect of pioglitazone compared with glimepiride on carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2572–2581. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.joc60158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.