Abstract

Coffee, tea, and maté may cause esophageal cancer (EC) by causing thermal injury to the esophageal mucosa. If so, the risk of EC attributable to thermal injury could be large in populations in which these beverages are commonly consumed. In addition, these drinks may cause or prevent EC via their chemical constituents. Therefore, a large number of epidemiologic studies have investigated the association of an indicator of amount or temperature of use of these drinks or other hot foods and beverages with risk of EC.

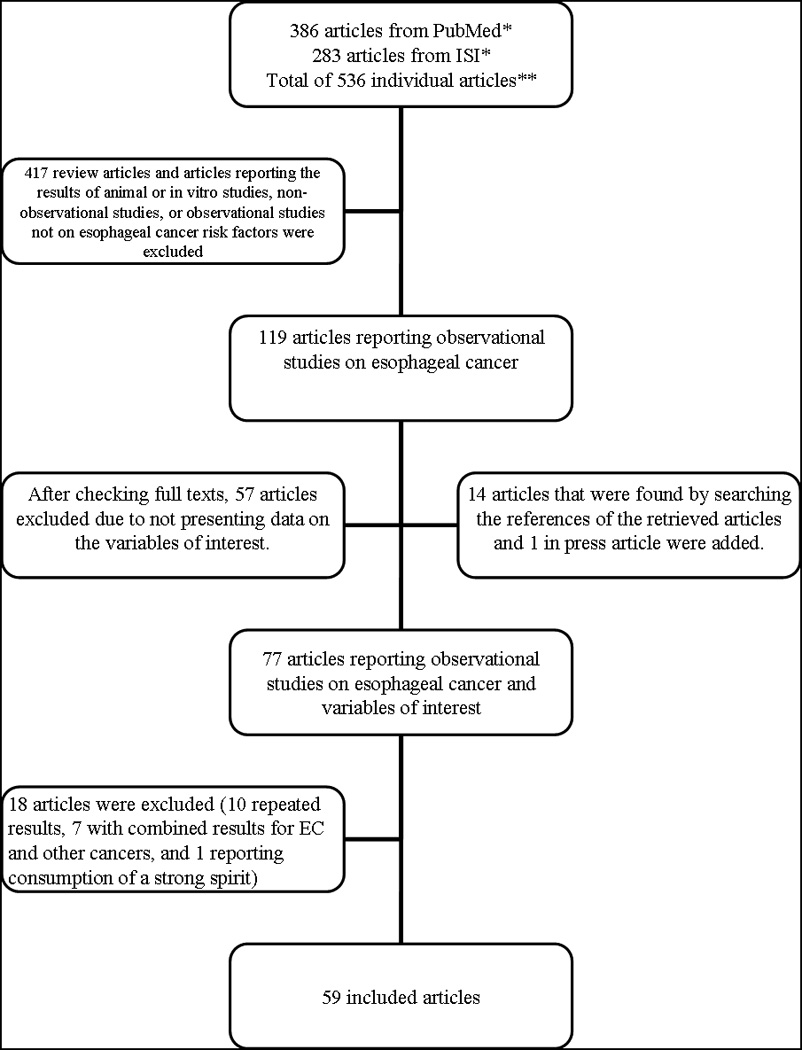

We conducted a systematic review of these studies, and report the results for amount and temperature of use separately. By searching PubMed and the ISI, we found 59 eligible studies.

For coffee and tea, there was little evidence for an association between amount of use and EC risk; however, the majority of studies showed an increased risk of EC associated with higher drinking temperature which was statistically significant in most of them. For maté drinking, the number of studies was limited, but they consistently showed that EC risk increased with both amount consumed and temperature, and these two were independent risk factors. For other hot foods and drinks, over half of the studies showed statistically significant increased risks of EC associated with higher temperature of intake.

Overall, the available results strongly suggest that high-temperature beverage drinking increases the risk of EC. Future studies will require standardized strategies that allow for combining data, and results should be reported by histological subtypes of EC.

Introduction

Recurrent thermal injury to the esophageal mucosa due to consuming large amounts of hot drinks has long been suspected to be a risk factor for esophageal cancer (EC). In 1939, WL Watson, after reviewing clinical records from 771 EC cases, wrote: “thermal irritation is probably the most constant factor predisposing to the cancer of the esophagus”.1 If hot drinks indeed cause EC, they can explain a large proportion of all cases in populations in which drinking tea, coffee, or maté (an herbal infusion of Ilex paraguariensis, commonly consumed in several South American countries), or eating hot foods are common. Nevertheless, the association of hot drinks with EC has been questioned both based on biologic reasons and empirical evidence.

It has been argued that the temperature of hot foods and drinks may fall rapidly in the mouth and oropharynx so that it cannot cause thermal injury to the esophageal mucosa.2 To test this hypothesis, De Jong and colleagues measured intraesophageal temperature after consuming hot drinks. The results of their study showed that drinking hot beverages could substantially increase the intra-esophageal temperature and this increase was a function of the initial drinking temperature and more importantly, the size of the sip.3 For example, drinking 65 °C coffee increased the intra-esophageal temperature by 6–12 °C, depending on the sip size.3

Tea, coffee, and maté may affect cancer risk not only through thermal effects but also via their chemical constituents. Although some studies have shown mutagenic effects for tea, coffee, and unprocessed maté herb (Ilex paraguariensis) extracts,4–10 a number of more recent experimental studies in animals have reported cancer preventive activities for these beverages (reviewed in refs. 11–15). A number of epidemiological studies have investigated a possible effect of these beverages on cancer risk. With respect to gastrointestinal cancers, recent meta-analyses did not find any significant association between tea drinking and gastric and colorectal cancers,16–18 but coffee drinking was shown to be inversely associated with risk of liver cancer.19,20

In 1990, a Working Group of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded that there was not sufficient evidence to recognize tea, coffee, or maté, in toto, as risk factors of human cancer, but they found that drinking hot maté was a probable risk factor in humans.21 The strongest evidence was for an association with EC. Since then, a large number of additional studies have investigated the association of the beverages and EC. We conducted a systematic review of the results of epidemiologic studies on the association of tea, coffee, or maté drinking or of high-temperature food consumption with EC.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a comprehensive search of the PubMed and ISI-Web of Knowledge databases for all case-control or cohort studies published in English language on the association of tea, coffee, maté, or other hot drinks or high temperature foods and risk of EC. All results were updated on January 23, 2009. The following terms were used in the PubMed Database search: “(esophag* OR oesophag*) AND (cancer OR carcinoma OR adenocarcinoma OR neoplasm OR neoplasia OR neoplastic) AND (tea OR mate OR coffee OR beverage)”; the search was repeated by replacing the last phrase with “(liquid OR drinks OR alcohol OR food) AND (hot OR cold OR warm OR temperature)”. The same terms were used to search text words in the ISI Database. In addition, references cited in the identified articles were searched manually. Two of the authors (FI and FK) reviewed the search results to reduce the possibility of missing the published papers.

Using the above-mentioned approach, a total of 536 articles were retrieved. Figure 1 shows a summary of the article selection process. After reading the abstracts of the retrieved articles, we excluded 417 articles because they were not case-control or cohort studies of hot drinks and EC; the excluded articles were reviews, animal studies, in vitro studies, case-series, studies of cancers other than EC, or studies of treatment and complications of EC. In case of any doubt, we also reviewed the full texts of those articles. After reviewing the full texts of the remaining 119 articles, we excluded another 57 because they did not present data on the variables of interest, but we found an additional 14 articles by searching the references of the articles. We also included a study which was in press at the time of our review.22 Therefore, a total of 77 relevant articles were found. Of these, 7 articles 23–29 were excluded because they reported data on EC in combination with other cancers and an additional 10 publications 30–39 were excluded because their results were reported in other publications or in combined analyses. One more study that referred to drinking of hot Calvados,40 a strong spirit which is a well established cause of EC, was excluded because separating the effect of temperature from that of the spirit per se would be difficult. Finally, a total of 59 full-text articles were included in this systematic review.22,41–98

Figure 1.

A summary of the search process

Tea, coffee, and maté constitute the three major types of hot drinks consumed around the world. Therefore, we present data for each one of these, as well as for the mixed group of other hot foods and drinks, in separate tables. The two main variables of interest were: 1) an indicator of amount consumed (frequency per day, amount per day, duration of use, or a composite variable indicating cumulative use); and 2) temperature.

The etiological factors responsible for the two main histological of EC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), may be different, and any role of hot drinks and foods might be more relevant for ESCC etiology.99 Therefore, where data are available, we present the results for ESCC and EAC separately.

Where both crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were reported in the paper, we only present the adjusted results. A small number of studies showed crude numbers but not ORs and 95% CIs, in which case we calculated these statistics using simple logistic regression models and present them. Throughout the article, P values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Tea

After excluding duplicate publications, we found 38 papers, published between 1974 and 2008, that reported on the association of tea drinking with EC (Table 1). These included 33 individual case-control studies, a pooled analysis of 5 case-control studies, a pooled analysis of 2 case-control studies, and 3 prospective studies. The studies were conducted in United States, South America, Europe, South-Africa, Middle-East, and South and East Asia, and included both high-risk and low-risk regions. Two of the prospective studies were from Japan and one was from China. There were large differences in study size, but the majority of the studies had between 100 and 400 EC cases. Whereas some studies described the type of tea consumed (e.g., green tea or black tea), the large majority did not report on tea type; however, black tea represents the predominant type of tea traditionally drunk in most regions outside East Asia.21

Table 1.

A summary of studies on the association between tea consumption and risk of esophageal cancer

| First author; year of publication (Country; period of study) |

Case / controla |

Amount, frequency, duration, or status of tea drinking |

OR/RR/HR (95% CI)b |

Tea drinking temperature |

OR/RR/HR (95% CI)b |

Comments (1. Study design; 2. histological subtypes of EC, if available; 3. matching criteria, if applicable; and 4. the adjustments in statistical models that were done for the presented results) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Jong; 197441 (Singapore; 1970–1972) |

131 / 665 (95 / 465 men and 36 / 200 women) |

Tea drinking frequency (men) Not daily Daily (women) Not daily Daily |

1 0.99 (NS/NR) 1 0.82 (NS/NR) |

(men) Other Burning hot (women) Other Burning hot |

1 2.96 (P <0.01) 1 2.28 (NS/NR) |

|

| Cook-Mozaffari; 197942 (Iran; 1975– 1976) |

344 / 688 (217 / 434 men and 127 / 254 women) |

Tea drinking amount | NS/NR |

(men) Other Hot tea (women) Other Hot tea |

1 1.72 (P <0.01) 1 2.17 (P <0.01) |

|

| Van Rensburg; 198543 (South Africa; 1978–1981) |

211 / 211 |

Tea with milk drinking amount |

NS/NR | - | - |

|

| Notani; 198744 (India; 1976– 1984) |

236 / 392 |

Tea drinking frequency (vs. hospital controls) ≤ 2 cups/day 2+ cups/day (vs. pupulation controls) ≤ 2 cups/day 2+ cups/day |

1 1.18 (0.8–1.8) 1 2.39 (1.5–3.9) |

- | - |

|

| Yu; 198845 (USA; 1975– 1981) |

275 / 275 |

Tea drinking frequency and the manner of drinking (sipped or gulped) |

NS/NR | Temperature | NS/NR |

|

| Brown; 198846 (USA; 1982–1984 for ‘incidence series’,1977– 1981 for ‘mortality series’) |

207 / 422 |

Tea drinking amount (both regular tea and local herbal teas) |

NS/NR | Temperature | NS/NR |

|

| Graham; 199047 (USA; 1975– 1986) |

178 / 174 |

Tea drinking frequency Nil 1–15 cups/month 16–28 cups/month 29–280 cups/month |

1 1.12 (0.60–2.09) 1.21 (0.68–2.17) 0.76 (0.41–1.41) |

- | - |

|

| La Vecchia; 199248 (Italy; 1983– 1990) |

294 / 6147 |

Tea drinking status Non-drinkers Drinkers |

1 1.0 (0.7–1.4) |

- | - |

|

| Wang, YP; 199249 (China, Shanxi; 1988–1989) |

326 / 396 | Tea drinking amount | NS/NR | - | - |

|

| Memik; 199250* (Turkey; not reported) |

78 / 558 |

Tea drinking frequency 0–3 glasses/day 4–10 glasses/day 11+ glasses/day |

1 0.28 (0.16–0.46) 0.25 (0.11–0.59) |

- | - |

|

| Hu; 199451 (China; 1985– 1989) |

196 / 392 |

Tea drinking amount Nil 50–1500 g/year 1501–3000 g/year 3000+ g/year Strength of tea Non-drinkers Weak Medium Strong |

1 1.2 (0.7–2.1) 1.8 (1.04–3.3) 3.9 (1.7–9.1) 1 0.8 (0.3–2.0) 1.1 (0.6–1.9) 2.5 (1.4–4.3) |

- | - |

|

| Gao, YT; 199452 (China; cases were ascertained during 1990– 1993, controls were ascertained during 1986– 1987) |

902 / 1552 |

Green tea Amount (men) Non-tea drinker Tea drinker 1–199 g/month 200+ g/month (women) Non-tea drinker Tea drinker 1–149 g/month 150+ g/month Amount × duration (men) Non-tea drinker 1–3499 (g/month × years) 3500+ (g/month × years) (women) Non-tea drinker 1–3499 3500+ Never smoker/drinkers Amount (men) Non-tea drinker Tea drinker 1–199 g/month 200+ g/month (women) Non-tea drinker Tea drinker 1–149 g/month 150+ g/month Amount × duration (men) Non-tea drinker 1–3499 (g/month × years) 3500+ (g/month × years) (women) Non-drinker 1–3499 (g/month × years) 3500+ (g/month × years) |

1 0.80 (0.58–1.09) 0.79 (0.53–1.17) 0.79 (0.56–1.13) 1 0.50 (0.30–0.83) 0.77 (0.39–1.53) 0.34 (0.17–0.69) 1 0.73 (0.48–1.11) 0.83 (0.59–1.16) 1 0.74 (0.40–1.38) 0.29 (0.13–0.65) 1 0.43 (0.22–0.86) 0.33 (0.14–0.80) 0.62 (0.25–1.54) 1 0.40 (0.20–0.77) 0.70 (0.31–1.58) 0.17 (0.05–0.58) 1 0.24 (0.08–0.72) 0.63 (0.29–1.41) 1 0.66 (0.32–1.37) 0.07 (0.01–0.54) |

See Table 4. |

|

|

| Srivastava; 199553 (India; not reported) |

75 / 75 | - | - | Hot Very hot |

1 NS/NR |

|

| Inoue; 199854 (Japan; 1990– 1995) |

185 / 21128 |

Green tea frequency Rarely Occasionally 1–3 cups/day 4-6 cups/day 7+ cups/day Black tea frequency Rarely Occasionally Daily |

1 1.02 (0.50–2.10) 1.07 (0.58–2.00) 0.96 (0.50–1.83) 1.14 (0.55–2.34) 1 0.44 (0.26–0.74) 1.03 (0.53–2.00) |

- | - |

|

| Kinjo; 199855 (Japan; 1966– 1981) |

440 / 220272 | - | - |

Green tea Non hot Hot |

1 1.5 (1.1–1.9) |

|

| Gao, CM; 199956 (China, 1995) |

81 / 234 |

Tea drinking amount Nil 1–199 g/month 200+ g/month |

1 0.63 (0.28–1.42) 0.42 (0.19–0.95) |

- | - |

|

| Tao; 199957 (China; 1984– 1988) |

71 / 1122 |

Tea drinking frequency < 1 cup/day 1+ cup/day |

1 0.70 (0.39–1.25) |

- | - |

|

| Castellsagué; 200058 (Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay;1985– 1992) |

830 / 1779 |

Tea drinking status Never-drinker Ever-drinker Amount Non-drinker 1–500 ml/day >500 ml/day |

1 0.81 (0.62–1.06) 1 0.90 (0.67–1.20) 0.62 (0.40–0.96) |

Cold/warm Hot Very hot |

1 0.66 (0.35–1.25) 3.73 (1.41–9.89) |

|

| Bosetti; 200059 (Italy; 1992– 1997) |

304 / 743 |

Coffee & tea frequency ≤ 7.9 times/week 8–14.4 times/week 14.5–20.9 times/week 21.0–24.9 times/week 25+ times/week (quintiles) |

1 0.91 (0.56–1.48) 0.82 (0.47–1.43) 0.91 (0.57–1.44) 0.71 (0.42–1.19) |

- | - |

|

| Nayar; 200060 (India; 1994– 1997) |

147 / 140 | - | - | Warm Hot Burning hot |

1 1.11 (0.62–1.96) 1.27 (0.60–2.69) |

|

| Cheng; 200061 (England, Scotland; 1993– 1996) |

74 / 74 |

Tea drinking amount Never/<1 /day ≤ 6 dcl/day 7–11 dcl/day 12+ dcl/day |

1 0.83 (0.26–2.63) 0.95 (0.30–3.08) 0.49 (0.14–1.72) |

Tea or coffee Warm Hot Very/burning hot |

1 0.75 (0.32–1.76) 0.51 (0.18–1.45) |

|

| Terry; 200162 (Sweden; 1995– 1997) |

167 ESCC and 189 EAC / 815 |

- | - |

Tea or coffee (ESCC) None, cold, lukewarm Hot Very hot (EAC) None, cold, lukewarm Hot Very hot |

1 1.0 (0.6–1.6) 0.8 (0.4–1.8) 1 0.7 (0.5–1.1) 0.6 (0.3–1.3) |

|

| Takezaki; 200163 (China; 1995– 2000) |

195 / 333 |

Tea drinking amount 0 g/month 1–149 g/month 150+ g/month |

1 0.73 (0.44–1.22) 0.64 (0.36–1.15) |

- | - |

|

| Sharp; 200164 (England, Scotland; 1993– 1996) |

159 / 159 |

Tea drinking amount Nil/<1 dcl/day ≤ 6 dcl/day 7-11 dcl/day 12+ dcl/day |

1 2.33 (0.62–8.86) 2.99 (0.85–10.56) 3.36 (0.99–11.29) |

Tea or coffee Very/burning hot Hot Warm |

1 0.75 (0.38–1.47) 0.34 (0.13–0.88) |

|

| Ke; 200265 (China; 1997– 2000) |

1248 / 1248 |

Congou tea Non-drinker Drinker (amount) 500− g/year 10000− g/year 20000− g/year 30000+ g/year Hot Congou tea Non-drinker Drinker (amount) 500− g/year 10000− g/year 20000− g/year 30000+ g/year |

1 0.40 (0.28–0.57) 1 0.52 (0.38–0.70) 0.44 (0.29–0.67) 0.05 (0.01–0.22) 1 0.04 (0.01–0.13) 1 0.41 (0.28–0.62) 0.57 (0.34–0.97) 0.03 (0.00–0.23) |

- | - |

|

| Sun; 200266 (China; 1986– 1998) |

42 / 209 |

Urinary tea polyphenols (epigallocatechin) Negative Positive ≤ 0.196 mg/g creatinine > 0.196 mg/g creatinine (epicatechin) Negative Positive ≤ 0.311 mg/g creatinine > 0.311 mg/g creatinine (M4) Negative Positive ≤ 0.220 mg/g creatinine > 0.220 mg/g creatinine (M6) Negative Positive ≤ 0.448 mg/g creatinine > 0.448 mg/g creatinine |

1 0.87 (0.38–2.02) 0.84 (0.32–2.19) 0.91 (0.36–2.31) 1 1.22 (0.48–3.10) 1.32 (0.51–3.45) 0.99 (0.32–3.04) 1 0.91 (0.44–1.89) 0.96 (0.43–2.15) 0.83 (0.32–2.14) 1 0.79 (0.38–1.66) 0.90 (0.40–2.01) 0.61 (0.22–1.65) |

- | - |

|

| Onuk; 200267 (Turkey; 1999– 2000) |

44 / 100 | - | - | Not hot Hot |

1 8.7 (2.5–30.2) |

|

| Gao, CM; 200268 (China; 1998– 2000) |

141 / 223 |

Tea drinking amount 0 g/month 1+ g/month |

1 0.45 (0.26–0.78) |

- | - |

|

| Tavani; 200369 (Italy, Switzerland; 1991–1997) |

395 / 1066 |

Tea drinking frequency <1 cup/day 1+ cup/day |

1 0.9 (0.7–1.2) |

- | - |

|

| Hung; 200470 (Taiwan; 1996– 2002) |

365 / 532 |

Tea drinking frequency (age 20–40 years) <1 time/week 1–6 times/week 7+ times/week (age 40+ years) <1 time/week 1–6 times/week 7+ times/week |

1 1.0 (0.5–1.7) 0.7 (0.4–1.1) 1 0.7 (0.4–1.2) 0.5 (0.3–0.8) |

- | - |

|

| Chitra; 200471 (India; 1999– 2000) |

90 / 90 |

Tea drinking frequency ≤3 cups/day 3+ cups/day |

1 3.3 (1.7–6.3) |

- | - |

|

| Yang CX; 200572 (China; 2003– 2004) |

185 / 185 |

Tea drinking frequency ≤ 1 time/week 2–4 times/week >4 times/week |

1 0.45 (0.15–1.36) 0.57 (0.25–1.31) |

- | - |

|

| Ishikawa; 200673 (Japan; 1984– 1992 cohort 1, 1990–1997 cohort 2) |

78 / 196686 person-year |

Green tea Frequency Never/occasionally 1–2 cups/day 3–4 cups/day 5+ cups/day |

HR (95% CI) 1 1.03 (0.46–2.28) 1.13 (0.53–2.42) 1.67 (0.89–3.16) |

- | - |

|

| Wang, Z; 200674 (China; 2002– 2003) |

107 / 107 |

Green tea Non-drinker Drinker |

1 0.13 (0.03–0.62) |

- | - |

|

| Wang, JM; 200775 (China; 2004– 2006) |

355 / 408 |

Green tea Status (men) Non-drinker Drinker (Women) Non-drinker Drinker Duration (men) Nil <30 years 30+ years (Women) Nil <30 years 30+ years |

1 1.37 (0.95–1.98) 1 0.26 (0.07–0.94) 1 1.31 (0.85–2.03) 1.44 (0.91–2.27) 1 0.33 (0.06–1.68) 0.18 (0.02–1.54) |

- | - |

|

| Gledovic; 200776 (Serbia; 1998– 2002) |

102 / 102 |

Tea drinking status Non-drinkers Drinkers |

1 NS/NR |

- | - |

|

| Wu; 200877 (China; 2003– 2007) |

1520 / 3879 |

Green tea High-risk area (status) Never drinker Ever drinker Former drinker Current drinker (duration) Never drinker <25 years 20–34 years 35+ years (monthly consumption) Never drinker 1–149 g 150–249 g 250+ g (age at tea drinking start) Never drinker <25 years 25–34 years 35–44 years 45+ years Low-risk area (status) Never drinker Ever drinker Former drinker Current drinker (duration) Never drinker <25 years 20–34 years 35+ years (monthly consumption) Never drinker 1–149 g 150–249 g 250+ g (age at tea drinking start) Never drinker <25 years 25–34 years 35–44 years 45+ years |

1 1.0 (0.7–1.3) 2.2 (1.6–5.3) 0.8 (0.6–1.1) 1 1.0 (0.6–1.4) 0.9 (0.6–1.4) 1.1 (0.7–1.8) 1 1.0 (0.7–1.3) 1.0 (0.6–1.8) 1.0 (0.6–2.0) 1 0.8 (0.4–1.5) 1.2 (0.8–1.8) 1.2 (0.7–1.9) 0.8 (0.6–1.2) 1 1.3 (0.9–1.7) 4.2 (2.3–7.6) 1.1 (0.8–1.5) 1 0.8 (0.5–1.5) 1.4 (1.0–2.0) 1.1 (0.8–1.6) 1 1.1 (0.7–1.7) 1.0 (0.7–1.6) 1.6 (1.1–2.2) 1 1.2 (0.8–1.9) 1.3 (1.0–1.9) 1.1 (0.7–1.8) 0.9 (0.4–1.9) |

Green tea High-risk area Never drinking Normal temperature High temperature Low-risk area Never drinking Normal temperature High temperature |

1 1.0 (0.7-1.3) 2.2 (1.6-5.3) 1 1.3 (0.9-1.7) 4.2 (2.3-7.6) |

|

| Islami; in press22 (Iran; |

298 / 568 |

Black tea (amount- quintiles) 0–675 ml/day 676–920 ml/day 921–1215 ml/day 1216–1725 ml/day 1726+ ml/day Green tea (frequency) Never, <weekly Daily, weekly |

1 0.91 (0.43–1.91) 0.68 (0.34–1.37) 1.46 (0.75–2.86) 1.83 (0.93–3.59) 1 0.86 (0.38–2.09) |

Temperature Warm or lukewarm Hot Very hot Time interval** 4+ minutes 2–3 minutes <2 minutes |

1 2.07 (1.28–3.35) 8.16 (3.93–16.91) 1 2.49 (1.62–3.83) 5.41 (2.63–11.14) |

|

Abbreviations: EAC, esophageal adenocarcinoma; EC, esophageal cancer; ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; M4, 5-(3′,4′,5′-trihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone (a metabolite of epigallocatechin); M6, 5-(3′,4′-trihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone (a metabolite of epicatechin); NR, not reported; NS/NR, non-significant/not reported (when the exact OR or 95% CI was not reported but the association was reported as non-significant); OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Number of cases and controls in case-control or prospective studies or number of person-years of follow-up in cohort studies, if it is indicated

If studies reported both crude and adjusted ORs (95% CIs), we only present the adjusted results.

These studies showed crude numbers but not ORs and 95% CIs; we calculated these statistics using simple logistic regression models and present them.

Time interval between pouring tea into a cup and drinking it.

Amount consumed

Most studies (n = 33) provided results for one of the indicators of amount consumed, e.g., amount per day, frequency per day, duration of use, or an indicator of cumulative use. However, not all studies reported ORs (95% CIs) or crude numbers. There was no clear pattern of association between amount of tea consumed and EC risk; 7 studies showed an increase in risk (4 were statistically significant), and this was counterbalanced by 15 individual studies and a pooled analysis of 5 case-control studies that showed an inverse association between tea drinking and EC risk, either in the main analyses or in subgroup analyses (the association in 8 studies was statistically significant). Four studies reported ORs close to one, on both sides of the null line, which were not statistically significant. In addition, 6 other studies only stated that the results were not statistically significant, without reporting detailed results. We did not find a clear pattern of association by geographic region. However, the majority of the inverse associations were from East-Asian countries, especially China, where mostly green tea is used.

Temperature

Results for the association of tea drinking temperature and EC were reported in 14 publications. Of these, 7 individual case-control studies, a combined analysis of 5 other case-control studies, and a prospective study found an increased risk; of these, the association was statistically significant in 8 studies. Two case-control studies reported statistically non-significant inverse associations, and 3 other studies only stated that the results were not statistically significant, without reporting crude numbers or ORs.

Coffee

We found 22 independent papers, published between 1974 and 2008, that reported on the association between coffee intake and EC (Table 2). These included 17 individual case-control studies, a pooled analysis of 5 case-control studies, a pooled analysis of 2 case-control studies, and 3 cohort studies. Most reports (n = 14) were from the United States or Europe. Most studies included between 100 and 400 EC cases.

Table 2.

A summary of studies on the association between coffee consumption and risk of esophageal cancer

| First author; year of publication (Country; period of study) |

Case / control a |

Amount, frequency, or status of coffee drinking |

OR/RR/HR (95% CI) b |

Coffee drinking Temperature |

OR/RR/HR (95% CI) b |

Comments (1. Study design; 2. histological subtypes of EC, if available; 3. matching criteria, if applicable; and 4. the adjustments in statistical models that were done for the presented results) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Jong; 197441 (Singapore; 1970–1972) |

131 / 665 |

Coffee drinking frequency (men) Not daily Daily (women) Not daily Daily |

1 0.93 (NS/NR) 1 1.42 (NS/NR) |

(men) Other Burning hot (women) Other Burning hot |

1 4.22 (NR, P <0.01) 1 4.09 (NR, P <0.01) |

|

| Jacobsen; 198678 (Norway; 1967– 1978) |

15 / See Notes |

Coffee drinking frequency (all) ≤2 cups/day 7+ cups/day (men) ≤2 cups/day 7+ cups/day |

1 1.19 (P = 0.85) 1 0.79 (P = 0.88) |

- | - |

|

| Yu; 198845 (USA; 1975– 1981) |

275 / 275 |

Coffee drinking frequency, the manner of drinking (sipped or gulped), and coffee type (caffeinated or decaffeinated) |

NS/NR | Temperature | NS/NR |

|

| Brown; 198846 (USA; 1982–1984 for ‘incidence series’,1977– 1981 for ‘mortality series’) |

207 / 422 | Coffee drinking amount | NS/NR | Temperature | NS/NR |

|

| La Vecchia; 198979 (Italy; 1983– 1988) |

209 / 1944 |

Coffee drinking frequency 0–1 cup/day 2 cups/day 3+ cups/day |

1 0.90 (NS) 0.98 (NS) |

- | - |

|

| Graham; 199047 (USA; 1975– 1986) |

178 / 174 | Coffee drinking amount | NS/NR | - | - |

|

| Memik; 199250 (Turkey; not reported) |

78 / 610 | Coffee drinking amount | NS/NR | - | - |

|

| Garidou; 199680 (Greece; 1989– 1991) |

43 ESCC and 56 EAC / 200 |

Coffee drinking frequency (ESCC) 1 cup/day more (EAC) 1 cup/day more |

1.15 (0.84–1.58) 1.11 (0.86–1.43) |

- | - |

|

| Inoue; 199854 (Japan; 1990– 1995) |

185 / 21128 |

Coffee drinking frequency Rarely Occasionally 1–2 cups/day 3+ cups/day |

1 0.82 (0.51–1.31) 0.77 (0.52–1.12) 0.79 (0.46–1.36) |

- | - |

|

| Castellsagué; 200058 (Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay; 1986– 1992) |

830 / 1779 |

Coffee drinking (status) Never-drinker Ever-drinker (amount) Non-drinker 1–500 ml/day >500 ml/day Coffee with milk (status) Never-drinker Ever-drinker (amount) Non-drinker 1–500 ml/day >500 ml/day |

1 1.04 (0.83–1.30) 1 0.96 (0.74–1.24) 1.26 (0.88-1.81) 1 1.15 (0.94–1.42) 1 1.12 (0.90–1.40) 1.31 (0.89–1.95) |

Coffee Cold/warm Hot Very hot Coffee with milk Cold/warm Hot Very hot |

1 0.54 (0.33–0.87) 1.01 (0.52–1.98) 1 0.89 (0.62–1.29) 2.29 (1.37–3.81) |

|

| Bosetti; 200059 (Italy; 1992– 1997) |

304 / 743 |

Coffee & tea frequency ≤ 7.9 times/week 8–14.4 times/week 14.5–20.9 times/week 21.0–24.9 times/week 25+ times/week (quintiles) |

1 0.91 (0.56–1.48) 0.82 (0.47–1.43) 0.91 (0.57–1.44) 0.71 (0.42–1.19) |

- | - |

|

| Terry; 200081 (Sweden; 1994– 1997) |

185 / 815 |

Coffee drinking frequency 0–2 cups/day 2–4 cups/day 4–7 cups/day >7 cups/day (quartiles) |

1 0.8 (0.5–1.4) 0.9 (0.5–1.5) 0.8 (0.5–1.4) |

- | - |

|

| Cheng; 200061 (England, Scotland; 1993– 1996) |

74 / 74 |

Coffee drinking amount Never/<1 /day ≤ 3 dcl 4–7 dcl 8+ dcl |

1 0.65 (0.27–1.53) 1.62 (0.53–4.94) 1.95 (0.68–5.57) |

Tea or coffee Warm Hot Very/burning hot |

1 0.75 (0.32–1.76) 0.51 (0.18–1.45) |

|

| Terry; 200162 (Sweden; 1995– 1997) |

167 ESCC and 189 EAC / 815 |

- | - |

Tea or coffee (ESCC) None, cold, lukewarm Hot Very hot (EAC) None, cold, lukewarm Hot Very hot |

1 1.0 (0.6–1.6) 0.8 (0.4–1.8) 1 0.7 (0.5–1.1) 0.6 (0.3–1.3) |

|

| Sharp; 200164 (England, Scotland; 1993– 1996) |

159 / 159 | - | - |

Tea or coffee Very/burning hot Hot Warm |

1 0.75 (0.38–1.47) 0.34 (0.13–0.88) |

|

| Onuk; 200267 (Turkey; 1999– 2000) |

44 / 100 |

Coffee drinking amount Low High |

1 0.8 (0.3–1.6) |

- | - |

|

| Tavani; 200369 (Italy, Switzerland; 1991–1997) |

395 / 1066 |

Coffee drinking frequency ≤1 cup/day >1–2 cup/day >2–3 cup/day 3+ cup/day Decaffeinated coffee <1 cup/day 1+ cup/day |

1 1.1 (0.8–1.6) 0.9 (0.6–1.3) 0.6 (0.4–0.9) 1 0.6 (0.2–1.5) |

- | - |

|

| Hung; 200470 (Taiwan; 1996– 2002) |

365 / 532 |

Coffee drinking frequency (age 20–40 years) <1 time/week 1+ times/week (age 40+ years) <1 time/week 1+ times/week |

1 0.7 (0.4–1.2) 1 0.7 (0.4–1.2) |

|

||

| Ishikawa; 200673 (Japan; 1984– 1992 cohort 1, 1990–1997 cohort 2) |

78 / 196686 person-year |

Coffee drinking frequency Never drinkers 1–2 cups/day 3+ cups/day |

1 0.63 (0.32–1.27) 0.94 (0.36–2.45) |

- | - |

|

| Gledovic; 200776 (Serbia; 1998– 2002) |

102 / 102 |

Coffee ever drinking and amount |

NS/NR | - | - |

|

| Rossini; 200882* (Brazil; 1995– 2000) |

36 / 290 |

Coffee drinking frequency <5 times a week 5+ times a week |

1 1.89 (0.43–8.27) |

- | - |

|

| Naganuma; 200883 (Japan; 1990– 2003) |

112 / 495138 person-year |

Coffee drinking frequency Never Occasionally 1+ cup/day |

1 0.56 (0.35–0.90) 0.60 (0.37–0.97) |

- | - |

|

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; EAC, esophageal adenocarcinoma; ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; HR, hazard ration; NR, not reported; NS/NR, non-significant/not reported (when the exact OR or 95% CI was not reported but the association was reported as non-significant); OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Number of cases and controls in case-control or prospective studies or number of person-years of follow-up in cohort studies, if it is indicated

If studies reported both crude and adjusted ORs (95% CIs), we only present the adjusted results.

These studies showed crude numbers but not ORs and 95% CIs; we calculated these statistics using simple logistic regression models and present them.

Amount consumed

Most studies (n = 20) reported one of the indicators of amount consumed and EC. Four case-control studies showed statistically non-significant positive associations. Seven studies reported an inverse association between coffee drinking and EC risk, of which only 1 prospective study from Japan and a combined analysis of 2 case-control studies from Italy and Switzerland showed statistically significant results for drinking 3 or more cups per day. Four other studies, including 2 prospective studies, showed non-significant results with ORs close to one, on both sides of null line. The remaining 5 studies only reported that the results were not statistically significant.

Temperature

Six individual case-control studies and a pooled analysis of 5 other case-control studies reported on temperature of coffee consumption in relation to EC risk. Of these, 2 individual studies and the pooled analysis showed an increased risk with drinking hot or very hot coffee, either in the main analyses or in subgroup analyses; 2 studies suggested statistically non-significant inverse associations, and 2 other studies only reported that the results were not statistically significant.

Maté

We found 4 independent papers, including 3 individual case-control studies and a combined analysis of 5 other case-control studies. These reports were published between 1985 and 2008 and all came from South American countries (Table 3).

Table 3.

A summary of studies on the association between maté consumption and risk of esophageal cancer

| First author; year of publication (Country; period of study) |

Case / control a |

Amount, frequency, duration, or status of maté drinking |

OR (95% CI) b | Maté drinking temperature |

OR (95% CI) b | Comments (1. Study design; 2. histological subtypes of EC, if available; 3. matching criteria, if applicable; and 4. the adjustments in statistical models that were done for the presented results) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vassallo; 198584 (Uruguay; 1979– 1984) |

226 / 469 |

Ever vs. never maté use Men Women Maté drinking amount (men) Non-drinker 0.01–0.49 l/day 0.50–0.99 l/day 1.0+ l/day (women) Non-drinker 0.01–0.49 l/day 0.50–0.99 l/day 1.0+ l/day |

3.9 (2.0–7.5) 11.9 (2.0–69.6) 1 1.1 (0.2–5.0) 3.1 (1.2–7.8) 4.8 (1.9–12.1) 1 2.1 (0.1–31.7) 12.5 (2.0–80.1) 34.6 (4.9–246.5) |

- | - |

|

| Castellsagué; 200058 (Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay; 1986– 1992) |

830 / 1779 |

Maté drinking (status) Never-drinker Ever-drinker Ex-drinker Current-drinker (amount) Nil 0.01–0.50 l/day 0.51–1.00 l/day 1.01–1.50 l/day 1.51–2.00 l/day >2.00 l/day (duration) Nil 1–29 years 30-39 years 40–49 years 50–59 years 60+ years (amount: cold/hot drinkers) ≤0.50 l/day 0.51–1.00 l/day 1.01–1.50 l/day 1.50+ l/day (amount: very hot drinkers) ≤0.50 l/day 0.51–1.00 l/day 1.01–1.50 l/day 1.50+ l/day |

1 1.52 (1.10–2.12) 1.87 (1.25–2.80) 1.47 (1.06–2.05) 1 1.39 (0.98–1.98) 1.34 (0.95–1.90) 1.96 (1.27–3.03) 2.03 (1.32–3.13) 3.04 (1.84–5.02) 1 1.40 (0.91–2.13) 1.39 (0.93–2.07) 1.53 (1.06–2.21) 1.47 (1.00–2.17) 1.92 (1.25–2.96) 1 0.91 (0.71–1.16) 1.50 (1.05–2.14) 1.38 (1.00–1.90) 0.99 (0.48–2.02) 1.59 (0.96–2.63) 0.73 (0.24–2.26) 4.14 (2.24–7.67) |

Cold/warm Hot Very hot |

1 1.11 (0.84–1.47) 1.89 (1.24–2.86) |

|

| Sewram; 200385 (Uruguay; 1988– 2000) |

344 / 469 |

Maté drinking (status) Never-drinker Ever-drinker (lifetime amount) Nil 1–8000 l-years 8001–16000 l-years 16001–24000 l-years 24001+ l-years (duration) Nil 1–35 years 36–49 years 50–58 years 59+ years (daily amount) Nil 0.01–0.50 l 0.51–1.00 l 1.01+ l |

1 2.26 (1.19–4.27) 1 1.43 (0.68–3.01) 2.21 (1.12–4.35) 2.43 (1.22–4.83) 3.07 (1.53–6.16) 1 1.31 (0.61–2.81) 2.29 (1.16–4.52) 2.58 (1.27–5.24) 4.31 (1.99–9.34) 1 1.69 (0.85–3.35) 2.47 (1.28–4.77) 2.84 (1.41–5.73) |

Non-drinkers Warm/hot Very hot |

1 2.00 (1.05–3.81) 3.98 (1.98–8.44) |

|

| De Stefani; 200886* and 200887* (Uruguay; 1996– 2004) |

234/936 for drinking amount 234/468 for drinking temperature |

Maté drinking amount Nil 0.01–0.99 l/day 1.00–1.99 l/day 2.00+ l/day |

1 1.86 (0.93–3.72) 3.05 (1.59–5.85) 3.30 (1.64–6.62) |

Warm Hot Very hot |

1 2.03 (1.23–3.34) 5.76 (2.92–11.35) |

|

Abbreviations: EAC, esophageal adenocarcinoma; ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk;95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Number of cases and controls

If studies reported both crude and adjusted ORs (95% CIs), we only present the adjusted results.

These studies showed crude numbers but not ORs and 95% CIs; we calculated these statistics using simple logistic regression models and present them.

Amount consumed

All reports showed significantly increased EC risk with amount consumed, with approximately 3-fold higher risk in those in the highest category of consumption compared to those who did not consume maté. The pooled analysis of the case-control studies found that amount per day and duration of drinking both increased risk.

Temperature

Three of these publications reported on the association of temperature of maté drinking and EC risk and all showed significant increased risk with increasing temperature. Mutual adjustment for temperature and amount in the pooled analysis suggested that amount and temperature of use were independent risk factors for EC.

High temperature food or other drinks

We found 19 publications (17 individual case-control studies, a combined analysis of 5 other case-control studies, and 1 prospective study) that presented results on the association of consumption of high temperature food, other drinks, or all beverages combined with risk of EC (Table 4). The reports were published between 1974 and 2008, and the studies were conducted in South Americas, Europe, Africa, and South and East Asia. For this category, we only present results on temperature.

Table 4.

A summary of studies on the association between high temperature foods or drinks (other than tea, coffee and maté, unless the results have been reported as a combination of them) and risk of esophageal cancer

| First author; year of publication (Country; period of study) |

Case / control a |

Food or drink temperature | OR/RR (95% CI)b | Comments (1. Study design; 2. histological subtypes of EC, if available; 3. matching criteria, if applicable; and 4. the adjustments in statistical models that were done for the presented results) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Jong; 197441 (Singapore; 1970–1972) |

131 / 665 |

Barely temperature (men) Other Burning hot (women) Other Burning hot |

1 6.97 (P < 0.01) 1 15.28 (P < 0.01) |

|

| Astini; 199088* (Ethiopia; 1988– 1989) |

25 / 50 |

High temperature food Non-user User |

1 36.0 (4.5–287.8) |

|

| Cheng; 199289 and 199590 (Hong Kong; 1989–1990) |

400 / 1598 (68 never smoker & 52 never drinker / 540 never smoker & 407 never drinker) |

Preference for hot drinks or soups (all participants) No Yes (never smokers) No Yes (never drinkers) No Yes |

1 1.64 (1.30–2.08) 1 1.51 (0.80–2.83) 1 1.76 (0.90–3.45) |

|

| Hu; 199451 (China; 1985– 1989) |

196 / 392 |

Eaten gruel temperature Cold Mild Hot Scalding |

1 1.1 (0.4–3.4) 2.4 (0.9–6.4) 5.3 (1.4–20.9) |

|

| Gao, YT; 199452 and 199491 (China; 1990– 1993) |

902 / 1552 |

Burning hot fluids (men) No + no green tea drinking Yes + no green tea drinking No + green tea drinking Yes + green tea drinking (women) No + no green tea drinking Yes + no green tea drinking No + green tea drinking Yes + green tea drinking Soup/porridge (men) Cold/lukewarm Hot Burning hot (women) Cold/lukewarm Hot Burning hot |

1 4.80 (2.85–8.08) 0.88 (0.61–1.29) 3.09 (1.94–4.93) 1 4.78 (2.89–7.90) 0.50 (0.27–0.91) 2.00 (0.75–5.07) 1 1.21 (0.88–1.66) 4.75 (3.33–6.79) 1 1.90 (1.29–2.79) 6.77 (4.09–11.20) |

|

| Hanaoka; 199492 (Japan; 1989– 1991) |

141 / 141 |

High temperature food and drink Dislike Indifferent Like |

1 2.06 (0.94–4.52) 2.99 (1.18–7.55) |

|

| Guo; 199493 (China; 1986– 1991) and Tran; 200594 (China; 1986– 2001) |

640 / 3200 |

Hot liquids 0 time/month 1+ times/month |

1 0.9 (0.7–1.0) |

|

| 1958 / 29584 |

Hot liquid in summer 0 time/year 1+ times/year Hot liquid in winter 0 time/year 1+ times/year |

1 0.96 (0.87–1.07) 1 0.95 (0.87–1.04) |

|

|

| Srivastava; 199553 (India; not reported) |

75 / 75 |

Food temperature Warm Hot |

1 NS/NR |

|

| Garidou; 199680 (Greece; 1989– 1991) |

43 ESCC and 56 EAC / 200 |

Preference for beverage & food (ESCC) Cold to hot Very hot (EAC) Cold to hot Very hot (ESCC + EAC) Cold to hot Very hot |

1 1.89 (0.80–4.49) 1 1.82 (0.85–3.91) 1 >1 (NR, P = 0.02) |

|

| Castellsagué; 200058 (Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay; 1986–1992) |

830 / 1779 |

Beverage temperature (any beverage, excluding maté) Never very hot Ever very hot (any beverage, including maté) Never very hot Ever very hot |

1 2.45 (1.72–3.49) 1 2.07 (1.55–2.76) |

|

| Nayar; 200060 (India; 1994– 1997) |

150 / 150 |

Food temperature Warm Hot |

1 0.68 (NS/NR) |

|

| Phukan; 200195 (India; 1997– 1998) |

502 / 1004 |

Food temperature Moderate Cold Hot |

1 1.2 (0.04–4.1) 2.8 (P <0.05) [See Note] |

|

| Yokoyama; 200296* (Japan; 2000– 2001) |

234 / 634 |

Preference for high temperature food (categories: Dislike very much, Dislike somewhat, Neither like nor dislike, Like somewhat, Like very much) |

NS/NR |

|

| Hung; 200470 (Taiwan; 1996– 2002) |

365 / 532 |

Hot drink or soup (age 20–40 years) <3 times/week 3+ times/week (age 40+ years) <3 times/week 3+ times/week Eating overheated food (age 20–40 years) No Yes (age 40+ years) No Yes |

1 1.8 (1.1–3.0) 1 1.3 (0.8–2.1) 1 2.7 (1.6–4.4) 1 2.1 (1.3–3.4) |

|

| Yang; 200572 (China; 2003– 2004) |

185 / 185 |

Eating high temperature food Rarely Occasionally Often |

1 0.43 (0.17–1.09) 0.40 (0.14–1.16) |

|

| Yokoyama; 200697 (Japan; 2000– 2004) |

52 / 412 |

Preference for hot food or drinks Dislike very much Dislike somewhat Neither like nor dislike Like somewhat Like very much |

1 0.21 (0.01–3.60) 1.00 (0.12–8.17) 1.53 (0.18–12.92) 3.43 (0.39–30.46) |

|

| Wu, M; 200698 (China; 2003– 2005) |

531 / 531 (291 / 291 from a high risk and 240 / 240 from a low risk area) |

Food temperature (high risk area) Normal Hot (low risk area) Normal Hot |

1 0.51 (0.24–1.09) 1 1.14 (0.55–2.41) |

|

| Wang, JM; 200775 (China; 2004– 2006) |

355 / 408 (223/252 men, 132/156 women) |

Food temperature (men) Warm Hot (women) Warm Hot |

1 2.13 (1.39–3.25) 1 3.05 (1.73–5.36) |

|

| Rossini; 200882* (Brazil; 1995– 2000) |

36 / 290 |

Hot drinks <1 time a week 1–2 times a week 3–4 times a week 5+ times a week Food temperature Cool Warm Hot |

1 0.69 (0.20–2.41) 0.71 (0.09–5.75) 1.14 (0.44–2.97) 1 1.13 (0.27–4.66) 0.98 (0.20–4.82) |

|

Abbreviations: EAC, esophageal adenocarcinoma; ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; OR, odds ratio; RR, relative risk;95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Number of cases and controls

If studies reported both crude and adjusted ORs (95% CIs), we only present the adjusted results.

These studies showed crude numbers but not ORs and 95% CIs; we calculated these statistics using simple logistic regression models and present them.

Temperature

In all, 11 individual case-control studies and the combined analysis showed positive associations (11 were statistically significant), whereas 2 case-control studies found statistically non-significant inverse associations. Two case-control studies and the prospective study reported ORs close to one, on both sides of null line, with no statistically significant association. Two other studies only stated that the results were not statistically significant, without reporting crude numbers or ORs.

Summary of all hot foods and drinks

A summary of the associations between amount or temperature of consumed tea, coffee, or maté, or consumption of high temperature food or other beverages, and risk of EC is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

A summary of the associations between amount or temperature of consumed tea, coffee, maté, or consumption of high temperature food or other beverages and risk of esophageal cancer by study design

| Variable | Prospective |

Case-control |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↓ | ↑ | ↔ | NS/NR | ↓ | ↑ | ↔ | NS/NR | Total | |

| Tea (38 papers) | |||||||||

| Amount | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 14 (8‡*) | 6 (4) | 4** | 6 | 33 |

| Temperature | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0) | 8 (7*) | 0 | 3 | 14 |

| Coffee (22 papers) | |||||||||

| Amount | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 | 0 | 6 (1**) | 4*(0) | 2 | 5 | 20 |

| Temperature | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0) | 3 (3*∫) | 0 | 2 | 7 |

| Maté (4 papers) | |||||||||

| Amount | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (4*) | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Temperature | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (3*) | 0 | 0 | 3 |

|

Temperature of food or other beverages (29 papers) |

0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1┴ | 0 | 2 (0) | 12 (11*) | 2 | 2 | 19 |

Numbers in parentheses represent statistically significant studies.

Associations: ↓, decreased risk; ↑, increased risk; ↔, ORs close to 1 or ORs with no clear trend in two sides of null line; NS/NR, there was no statistically significant association but crude numbers or ORs were not reported or ORs for adjusted models cannot be calculated.

In two studies, the inverse association was observed only among women.

One of the studies was a pooled analysis of 5 other studies.

One of the studies was a pooled analysis of 2 other studies.

In the pooled analysis of 5 other studies, the positive association was reported for drinking very hot coffee and milk.

In the nested control study, an odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of 0.9 (0.7–1.0) was reported. When the cases from an extended study were compared with a sub-cohort, no significant association was found.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we collected the published literature on the association between consuming tea, coffee, maté, or other high-temperature beverages or foods and risk of EC. We analyzed the results for amount consumed and temperature of drinking separately. For tea and coffee, there was little evidence that the amount consumed was associated with EC risk, but the majority of the publications reported statistically significant increased risks associated with higher temperature of use. For maté, individual studies and the combined analyses showed increased risk of EC associated with both amount consumed and with temperature of drinking, and these two seemed to be independent risk factors. For other hot foods and drinks, the majority of studies showed higher risk of EC associated with higher temperature of use.

There are several limitations to making definitive conclusions about the association of amount or temperature of these drinks with EC risk. Some of these limitations are due to the design of the published studies (retrospective nature of the data, subjective questions, incomplete questionnaires, and lack of information on histologic type of EC) and others are due to incomplete analysis or reporting of the data. The large majority of the reports were based on retrospective case-controls studies, so the data might have been subject to interviewer bias or recall bias. This is further complicated by asking subjective questions, such as “how hot do you drink your tea?”, which can be particularly prone to such biases. To our knowledge, very few published studies have actually measured the actual temperature of tea, coffee, or maté drinking (reviewed in ref 22). Obtaining data on amount or frequency of drinking per day, total duration of drinking, sip size (or an indicator of this), and temperature of drinking are important. Unfortunately, many of the published studies did not collect data on several of these factors or did not report the results; studying the effect of hot temperature drinks was not the main aim of most of these studies. Furthermore, few studies adjusted the results of drinking temperature for amount consumed and vice versa, and many studies failed to adjust the results for other confounders. Also, many studies combined the results for several types of beverages (e.g., tea and coffee), which made it difficult to look at effects of these drinks separately; this problem was more prominent for black and green tea use. A number of studies reported that the results were not significant, but provided no counts or ORs (95% CIs). Such incomplete reporting prohibits use of the results in future meta-analyses. There is a large body of evidence suggesting that the risk factors for ESCC and EAC may be different. For example, there is strong evidence for a positive dose-response association between body mass index and risk of EAC,100 whereas several studies have reported an inverse association between body mass index and risk of ESCC.99 Nevertheless, few studies reported the results for ESCC and EAC separately.

Because of large heterogeneity in design and reporting, and also incomplete reporting in several studies, we conducted a systematic review but avoided formal combination of the results as a meta-analysis. However, many of the limitations mentioned above can be addressed in future studies. Using a standard questionnaire across studies would help in collecting uniform data. Actual measurement of tea temperature is already being conducted in a cohort study in Iran,22,101 where very high rates of ESCC are seen.102,103 In this study, two simultaneous cups of tea are poured; one is given to the study subject and a thermometer is put in the second cup.101 At intervals of 5°C (75°C, 70°C, 65°C, …) the subject is asked to sip the tea and tell the interviewer whether this is the usual temperature at which he/she drinks tea. This method for measuring tea temperature had shown a very good repeatability 101 and can be used in future studies, especially in areas with very high risk of EC. Measurement of relevant metabolites in biological samples might be helpful to validate the self-reported data on amount of consumed beverages.

Thermal injury may cause EC via both direct and indirect pathways. Inflammatory processes associated with chronic irritation of the esophageal mucosa by local hyperthermia might stimulate the endogenous formation of reactive nitrogen species, and subsequently, nitrosamines.104 This hypothesis is supported by high rates of somatic G > A transitions in CpG dinucleotides of the TP53 gene in ESCC tumor samples from areas in which drinking hot beverages is considered an important risk factor for ESCC;105–108 these mutations may indicate increased nitric oxide synthase activity in tumors.109 Thermal injury can also impair the barrier function of the esophageal epithelium, which may increase the risk of damage from exposure to intra-luminal carcinogens.110 An association between hot drinks and precancerous lesion of the esophagus has also been reported.111,112 Nevertheless, further prospective studies are indicated to investigate the association between high-temperature beverage or food consumption and risk of EC.

Chemical composition of tea, coffee, and maté has been reviewed in detail elsewhere.21 Some constituents of tea, coffee, and maté may have anti-carcinogenic properties; for example, flavonoids and caffeine show antioxidant activities.12,13,113 Composition of the beverages may change during production procedures; for example, in production of black tea and coffee, fermentation of tea leaves reduces a large percentage of some flavonoids,12,13 and severe roasting of coffee beans can considerably reduce their total cholorogenic acid content.21 Furthermore, black tea and maté may acquire some potentially carcinogenic contaminants, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) and mycotoxins, when being processed;114,115 high levels of PAH exposure has been reported among black tea and maté drinkers.116,117 Both black and green tea drinking may increase plasma antioxidant activity in humans.118 On the other hand, in a clinical trial in Linxian and Huixian, China, decaffeinated green tea was not shown to have beneficial effects in alleviating esophageal precancerous lesions and abnormal cell proliferation patterns after 11 years of follow-up.119 Other hot foods and drinks, such as foods containing processed meat and preserved fish,120 may potentially have carcinogenic chemical constituents. However, most studies used in this review compared the intake of the same food in higher versus lower temperatures. Therefore, unless higher temperature results in further formation or release of carcinogens, the results should not be confounded by chemical constituents, and any association should be attributed to thermal injury.

Although the number of studies that reported inverse associations between amount of tea or coffee consumed is higher than the number of studies that showed positive associations, the overall results are mixed. Despite cancer preventive activity of tea in experimental studies, it is not clear why epidemiological studies have not consistently shown an inverse association between tea drinking and risk of EC. Furthermore, all of the epidemiological studies that showed a statistically significant inverse association between tea drinking and risk of EC were case-control studies. In case-control studies, a possible reduction in tea intake by EC cases following their symptoms might lead to under-reporting of past tea consumption, and subsequently, resulting in spurious inverse associations. Tea and coffee contain several compounds other than flavonoids21 and may have some contaminants, which their interactions and their complex metabolisms might alter the protective effect of the individual compounds.17 It has also been suggested that flavonoids, or other anti-oxidants, in high doses may act as pro-oxidant that can generate free radicals, which may lead to DNA damage and finally irreversible pre-neoplastic lesions (reviewed in refs. 8,121).

In conclusion, there was little evidence for an association between EC risk and amount of tea or coffee consumed but the results suggest an increased risk of EC associated with higher drinking temperature. Amount, duration, and temperature of maté intake were all associated with higher EC risk, but number of the studies that investigated these associations was limited. For other hot foods and drinks, there was some evidence showing increased risk with higher temperature. Overall, the available results strongly suggest that high-temperature beverage drinking increases the risk of EC. Future studies will require standardized strategies that allow for combining data, and results should be reported by histological subtypes of EC.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Watson WL. Cancer of the esophagus: some etiological considerations. Am J Roentgenol. 1939;14:420–424. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steiner PE. The etiology and histogenesis of carcinoma of the esophagus. Cancer. 1956;9:436–452. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195605/06)9:3<436::aid-cncr2820090303>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Jong UW, Day NE, Mounier-Kuhn PL, Haguenauer JP. The relationship between the ingestion of hot coffee and intraoesophageal temperature. Gut. 1972;13:24–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.13.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uyeta M, Taue S, Mazaki M. Mutagenicity of hydrolysates of tea infusions. Mutat Res. 1981;88:233–240. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(81)90035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagao M, Fujita Y, Wakabayashi K, Nukaya H, Kosuge T, Sugimura T. Mutagens in coffee and other beverages. Environ Health Perspect. 1986;67:89–91. doi: 10.1289/ehp.866789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alejandre-Duran E, Alonso-Moraga A, Pueyo C. Implication of active oxygen species in the direct-acting mutagenicity of tea. Mutat Res. 1987;188:251–257. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(87)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tewes FJ, Koo LC, Meisgen TJ, Rylander R. Lung cancer risk and mutagenicity of tea. Environ Res. 1990;52:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0013-9351(05)80148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skibola CF, Smith MT. Potential health impacts of excessive flavonoid intake. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:375–383. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorado G, Barbancho M, Pueyo C. Coffee is highly mutagenic in the L-arabinose resistance test in Salmonella typhimurium. Environ Mutagen. 1987;9:251–260. doi: 10.1002/em.2860090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonseca CA, Otto SS, Paumgartten FJ, Leitao AC. Nontoxic, mutagenic, and clastogenic activities of Mate-Chimarrao (Ilex paraguariensis) J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2000;19:333–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambert JD, Yang CS. Mechanisms of cancer prevention by tea constituents. J Nutr. 2003;133:3262S–3267S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.10.3262S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang CS, Lambert JD, Ju J, Lu G, Sang S. Tea and cancer prevention: molecular mechanisms and human relevance. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;224:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shukla Y. Tea and cancer chemoprevention: a comprehensive review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8:155–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen D, Milacic V, Chen MS, Wan SB, Lam WH, Huo C, Landis-Piwowar KR, Cui QC, Wali A, Chan TH, Dou QP. Tea polyphenols, their biological effects and potential molecular targets. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:487–496. doi: 10.14670/hh-23.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heck CI, de Mejia EG. Yerba Mate Tea (Ilex paraguariensis): a comprehensive review on chemistry, health implications, and technological considerations. J Food Sci. 2007;72:R138–R151. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun CL, Yuan JM, Koh WP, Yu MC. Green tea, black tea and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1301–1309. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myung SK, Bae WK, Oh SM, Kim Y, Ju W, Sung J, Lee YJ, Ko JA, Song JI, Choi HJ. Green tea consumption and risk of stomach cancer: A meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Int J Cancer. 2008 doi: 10.1002/ijc.23880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou Y, Li N, Zhuang W, Liu G, Wu T, Yao X, Du L, Wei M, Wu X. Green tea and gastric cancer risk: meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17:159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsson SC, Wolk A. Coffee consumption and risk of liver cancer: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1740–1745. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bravi F, Bosetti C, Tavani A, Bagnardi V, Gallus S, Negri E, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Coffee drinking and hepatocellular carcinoma risk: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2007;46:430–435. doi: 10.1002/hep.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.IARC Working Group. IARC monographs on evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. vol 51. Lyon: IARC Press; 1991. Coffee, Tea, Mate, Methylxanthines and Methylglyoxal. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Islami F, Pourshams A, Nasrollahzadeh D, Kamangar F, Fahimi S, Shakeri R, Abedi-Ardekani B, Merat S, Vahedi H, Semnani S, Abnet CC, Brennan P, et al. Tea drinking habits and oesophageal cancer in a high risk area in Northern Iran. BMJ. 2009 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b929. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez I. Retrospective and prospective study of carcinoma of the esophagus, mouth, and pharynx in Puerto Rico. Bol Asoc Med P R. 1970;62:170–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez I. Factors associated with ccer of the esophagus, mouth, and pharynx in Puerto Rico. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1969;42:1069–1094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li JY, Ershow AG, Chen ZJ, Wacholder S, Li GY, Guo W, Li B, Blot WJ. A case-control study of cancer of the esophagus and gastric cardia in Linxian. Int J Cancer. 1989;43:755–761. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chyou PH, Nomura AM, Stemmermann GN. Diet, alcohol, smoking and cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract: a prospective study among Hawaii Japanese men. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:616–621. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown LM, Swanson CA, Gridley G, Swanson GM, Schoenberg JB, Greenberg RS, Silverman DT, Pottern LM, Hayes RB, Schwartz AG. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus: role of obesity and diet. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:104–109. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.2.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng W, Doyle TJ, Kushi LH, Sellers TA, Hong CP, Folsom AR. Tea consumption and cancer incidence in a prospective cohort study of postmenopausal women. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:175–182. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turkdogan MK, Akman N, Tuncer I, Uygan I, Kosem M, Ozel S, Kara K, Bozkurt S, Memik F. Epidemiological aspects of endemic upper gastrointestinal cancers in eastern Turkey. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:496–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Stefani E, Ronco A, Mendilaharsu M, Deneo-Pellegrini H. Case-control study on the role of heterocyclic amines in the etiology of upper aerodigestive cancers in Uruguay. Nutr Cancer. 1998;32:43–48. doi: 10.1080/01635589809514715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Stefani E, Deneo-Pellegrini H, Boffetta P, Mendilaharsu M. Meat intake and risk of squamous cell esophageal cancer: a case-control study in Uruguay. Int J Cancer. 1999;82:33–37. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990702)82:1<33::aid-ijc7>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Stefani E, Deneo-Pellegrini H, Mendilaharsu M, Ronco A. Diet and risk of cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract--I. Foods. Oral Oncol. 1999;35:17–21. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Stefani E, Deneo-Pellegrini H, Ronco AL, Boffetta P, Brennan P, Munoz N, Castellsague X, Correa P, Mendilaharsu M. Food groups and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus: a case-control study in Uruguay. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1209–1214. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Stefani E, Boffetta P, Deneo-Pellegrini H, Ronco AL, Correa P, Mendilaharsu M. The role of vegetable and fruit consumption in the aetiology of squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus: a case-control study in Uruguay. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:130–135. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Victora CG, Munoz N, Day NE, Barcelos LB, Peccin DA, Braga NM. Hot beverages and oesophageal cancer in southern Brazil: a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1987;39:710–716. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910390610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rolon PA, Castellsague X, Benz M, Munoz N. Hot and cold mate drinking and esophageal cancer in Paraguay. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castelletto R, Castellsague X, Munoz N, Iscovich J, Chopita N, Jmelnitsky A. Alcohol, tobacco, diet, mate drinking, and esophageal cancer in Argentina. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:557–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Stefani E, Munoz N, Esteve J, Vasallo A, Victora CG, Teuchmann S. Mate drinking, alcohol, tobacco, diet, and esophageal cancer in Uruguay. Cancer Res. 1990;50:426–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Stefani E, Ronco AL, Boffetta P, Deneo-Pellegrini H, Acosta G, Correa P, Mendilaharsu M. Nutrient intake and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: a case-control study in Uruguay. Nutr Cancer. 2006;56:149–157. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5602_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Launoy G, Milan C, Day NE, Faivre J, Pienkowski P, Gignoux M. Oesophageal cancer in France: potential importance of hot alcoholic drinks. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:917–923. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970611)71:6<917::aid-ijc1>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Jong UW, Breslow N, Hong JG, Sridharan M, Shanmugaratnam K. Aetiological factors in oesophageal cancer in Singapore Chinese. Int J Cancer. 1974;13:291–303. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910130304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cook-Mozaffari PJ, Azordegan F, Day NE, Ressicaud A, Sabai C, Aramesh B. Oesophageal cancer studies in the Caspian Littoral of Iran: results of a case-control study. Br J Cancer. 1979;39:293–309. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1979.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Rensburg SJ, Bradshaw ES, Bradshaw D, Rose EF. Oesophageal cancer in Zulu men, South Africa: a case-control study. Br J Cancer. 1985;51:399–405. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1985.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Notani PN, Jayant K. Role of diet in upper aerodigestive tract cancers. Nutr Cancer. 1987;10:103–113. doi: 10.1080/01635588709513945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu MC, Garabrant DH, Peters JM, Mack TM. Tobacco, alcohol, diet, occupation, and carcinoma of the esophagus. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3843–3848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown LM, Blot WJ, Schuman SH, Smith VM, Ershow AG, Marks RD, Fraumeni JF., Jr Environmental factors and high risk of esophageal cancer among men in coastal South Carolina. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80:1620–1625. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.20.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graham S, Marshall J, Haughey B, Brasure J, Freudenheim J, Zielezny M, Wilkinson G, Nolan J. Nutritional epidemiology of cancer of the esophagus. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:454–467. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S, D'Avanzo B, Boyle P. Tea consumption and cancer risk. Nutr Cancer. 1992;17:27–31. doi: 10.1080/01635589209514170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang YP, Han XY, Su W, Wang YL, Zhu YW, Sasaba T, Nakachi K, Hoshiyama Y, Tagashira Y. Esophageal cancer in Shanxi Province, People's Republic of China: a case-control study in high and moderate risk areas. Cancer Causes Control. 1992;3:107–113. doi: 10.1007/BF00051650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Memik F, Gulten M, Nak SG. The etiological role of diet, smoking, and drinking habits of patients with esophageal carcinoma in Turkey. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 1992;11:197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hu J, Nyren O, Wolk A, Bergstrom R, Yuen J, Adami HO, Guo L, Li H, Huang G, Xu X. Risk factors for oesophageal cancer in northeast China. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:38–46. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao YT, McLaughlin JK, Blot WJ, Ji BT, Dai Q, Fraumeni JF., Jr Reduced risk of esophageal cancer associated with green tea consumption. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:855–858. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.11.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Srivastava M, Kapil U, Chattopadhyaya TK, Shukla NK, Gnanasekaran N, Jain GL, Joshi YK, Nayar D. Nutritional risk factors in carcinoma esophagus. Nutr Res. 1995;15:177–185. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Inoue M, Tajima K, Hirose K, Hamajima N, Takezaki T, Kuroishi T, Tominaga S. Tea and coffee consumption and the risk of digestive tract cancers: data from a comparative case-referent study in Japan. Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9:209–216. doi: 10.1023/a:1008890529261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kinjo Y, Cui Y, Akiba S, Watanabe S, Yamaguchi N, Sobue T, Mizuno S, Beral V. Mortality risks of oesophageal cancer associated with hot tea, alcohol, tobacco and diet in Japan. J Epidemiol. 1998;8:235–243. doi: 10.2188/jea.8.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao CM, Takezaki T, Ding JH, Li MS, Tajima K. Protective effect of allium vegetables against both esophageal and stomach cancer: a simultaneous case-referent study of a high-epidemic area in Jiangsu Province, China. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1999;90:614–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1999.tb00791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tao X, Zhu H, Matanoski GM. Mutagenic drinking water and risk of male esophageal cancer: a population-based case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;150:443–452. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Castellsague X, Munoz N, De Stefani E, Victora CG, Castelletto R, Rolon PA. Influence of mate drinking, hot beverages and diet on esophageal cancer risk in South America. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:658–664. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001115)88:4<658::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bosetti C, La Vecchia C, Talamini R, Simonato L, Zambon P, Negri E, Trichopoulos D, Lagiou P, Bardini R, Franceschi S. Food groups and risk of squamous cell esophageal cancer in northern Italy. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:289–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nayar D, Kapil U, Joshi YK, Sundaram KR, Srivastava SP, Shukla NK, Tandon RK. Nutritional risk factors in esophageal cancer. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:781–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheng KK, Sharp L, McKinney PA, Logan RF, Chilvers CE, Cook-Mozaffari P, Ahmed A, Day NE. A case-control study of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in women: a preventable disease. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:127–132. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Terry P, Lagergren J, Wolk A, Nyren O. Drinking hot beverages is not associated with risk of oesophageal cancers in a Western population. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:120–121. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takezaki T, Gao CM, Wu JZ, Ding JH, Liu YT, Zhang Y, Li SP, Su P, Liu TK, Tajima K. Dietary protective and risk factors for esophageal and stomach cancers in a low-epidemic area for stomach cancer in Jiangsu Province, China: comparison with those in a high-epidemic area. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92:1157–1165. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2001.tb02135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharp L, Chilvers CE, Cheng KK, McKinney PA, Logan RF, Cook-Mozaffari P, Ahmed A, Day NE. Risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus in women: a case-control study. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1667–1670. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ke L, Yu P, Zhang ZX, Huang SS, Huang G, Ma XH. Congou tea drinking and oesophageal cancer in South China. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:346–347. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun CL, Yuan JM, Lee MJ, Yang CS, Gao YT, Ross RK, Yu MC. Urinary tea polyphenols in relation to gastric and esophageal cancers: a prospective study of men in Shanghai, China. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1497–1503. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.9.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Onuk MD, Oztopuz A, Memik F. Risk factors for esophageal cancer in eastern Anatolia. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1290–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao CM, Takezaki T, Wu JZ, Li ZY, Liu YT, Li SP, Ding JH, Su P, Hu X, Xu TL, Sugimura H, Tajima K. Glutathione-S-transferases M1 (GSTM1) and GSTT1 genotype, smoking, consumption of alcohol and tea and risk of esophageal and stomach cancers: a case-control study of a high-incidence area in Jiangsu Province, China. Cancer Lett. 2002;188:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tavani A, Bertuzzi M, Talamini R, Gallus S, Parpinel M, Franceschi S, Levi F, La Vecchia C. Coffee and tea intake and risk of oral, pharyngeal and esophageal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2003;39:695–700. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hung HC, Huang MC, Lee JM, Wu DC, Hsu HK, Wu MT. Association between diet and esophageal cancer in Taiwan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:632–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chitra S, Ashok L, Anand L, Srinivasan V, Jayanthi V. Risk factors for esophageal cancer in Coimbatore, southern India: a hospital-based case-control study. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23:19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang CX, Wang HY, Wang ZM, Du HZ, Tao DM, Mu XY, Chen HG, Lei Y, Matsuo K, Tajima K. Risk factors for esophageal cancer: a case-control study in South-western China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2005;6:48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ishikawa A, Kuriyama S, Tsubono Y, Fukao A, Takahashi H, Tachiya H, Tsuji I. Smoking, alcohol drinking, green tea consumption and the risk of esophageal cancer in Japanese men. J Epidemiol. 2006;16:185–192. doi: 10.2188/jea.16.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang Z, Tang L, Sun G, Tang Y, Xie Y, Wang S, Hu X, Gao W, Cox SB, Wang JS. Etiological study of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in an endemic region: a population-based case control study in Huaian, China. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:287. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang JM, Xu B, Rao JY, Shen HB, Xue HC, Jiang QW. Diet habits, alcohol drinking, tobacco smoking, green tea drinking, and the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in the Chinese population. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:171–176. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32800ff77a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gledovic Z, Grgurevic A, Pekmezovic T, Pantelic S, Kisic D. Risk factors for esophageal cancer in Serbia. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007;26:265–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu M, Liu AM, Kampman E, Zhang ZF, Van't Veer P, Wu DL, Wang PH, Yang J, Qin Y, Mu LN, Kok FJ, Zhao JK. Green tea drinking, high tea temperature and esophageal cancer in high- and low-risk areas of Jiangsu Province, China: A population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2008 doi: 10.1002/ijc.24142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jacobsen BK, Bjelke E, Kvale G, Heuch I. Coffee drinking, mortality, and cancer incidence: results from a Norwegian prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;76:823–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.La Vecchia C, Ferraroni M, Negri E, D'Avanzo B, Decarli A, Levi F, Franceschi S. Coffee consumption and digestive tract cancers. Cancer Res. 1989;49:1049–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garidou A, Tzonou A, Lipworth L, Signorello LB, Kalapothaki V, Trichopoulos D. Life-style factors and medical conditions in relation to esophageal cancer by histologic type in a low-risk population. Int J Cancer. 1996;68:295–299. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961104)68:3<295::AID-IJC5>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Terry P, Lagergren J, Wolk A, Nyren O. Reflux-inducing dietary factors and risk of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. Nutr Cancer. 2000;38:186–191. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC382_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rossini AR, Hashimoto CL, Iriya K, Zerbini C, Baba ER, Moraes-Filho JP. Dietary habits, ethanol and tobacco consumption as predictive factors in the development of esophageal carcinoma in patients with head and neck neoplasms. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:316–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Naganuma T, Kuriyama S, Kakizaki M, Sone T, Nakaya N, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Nishino Y, Fukao A, Tsuji I. Coffee Consumption and the Risk of Oral, Pharyngeal, and Esophageal Cancers in Japan: The Miyagi Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vassallo A, Correa P, De Stefani E, Cendan M, Zavala D, Chen V, Carzoglio J, Deneo-Pellegrini H. Esophageal cancer in Uruguay: a case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:1005–1009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sewram V, De Stefani E, Brennan P, Boffetta P. Mate consumption and the risk of squamous cell esophageal cancer in uruguay. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:508–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.De Stefani E, Boffetta P, Fagundes RB, Deneo-Pellegrini H, Ronco AL, Acosta G, Mendilaharsu M. Nutrient patterns and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: a factor analysis in uruguay. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:2499–2506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Stefani E, Boffetta P, Ronco AL, Deneo-Pellegrini H, Correa P, Acosta G, Mendilaharsu M. Exploratory factor analysis of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus in Uruguay. Nutr Cancer. 2008;60:188–195. doi: 10.1080/01635580701630487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Astini C, Mele A, Desta A, Doria F, Carrieri MP, Osborn J, Pasquini P. Drinking water during meals and oesophageal cancer: a hypothesis derived from a case-control study in Ethiopia. Ann Oncol. 1990;1:447–448. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a057802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cheng KK, Day NE, Duffy SW, Lam TH, Fok M, Wong J. Pickled vegetables in the aetiology of oesophageal cancer in Hong Kong Chinese. Lancet. 1992;339:1314–1318. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91960-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cheng KK, Duffy SW, Day NE, Lam TH. Oesophageal cancer in never-smokers and never-drinkers. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:820–822. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gao YT, McLaughlin JK, Gridley G, Blot WJ, Ji BT, Dai Q, Fraumeni JF., Jr Risk factors for esophageal cancer in Shanghai, China. II. Role of diet and nutrients. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:197–202. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hanaoka T, Tsugane S, Ando N, Ishida K, Kakegawa T, Isono K, Takiyama W, Takagi I, Ide H, Watanabe H. Alcohol consumption and risk of esophageal cancer in Japan: a case-control study in seven hospitals. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1994;24:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guo W, Blot WJ, Li JY, Taylor PR, Liu BQ, Wang W, Wu YP, Zheng W, Dawsey SM, Li B. A nested case-control study of oesophageal and stomach cancers in the Linxian nutrition intervention trial. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:444–450. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tran GD, Sun XD, Abnet CC, Fan JH, Dawsey SM, Dong ZW, Mark SD, Qiao YL, Taylor PR. Prospective study of risk factors for esophageal and gastric cancers in the Linxian general population trial cohort in China. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:456–463. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Phukan RK, Chetia CK, Ali MS, Mahanta J. Role of dietary habits in the development of esophageal cancer in Assam, the north-eastern region of India. Nutr Cancer. 2001;39:204–209. doi: 10.1207/S15327914nc392_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yokoyama A, Kato H, Yokoyama T, Tsujinaka T, Muto M, Omori T, Haneda T, Kumagai Y, Igaki H, Yokoyama M, Watanabe H, Fukuda H, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases and glutathione S-transferase M1 and drinking, smoking, and diet in Japanese men with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1851–1859. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.11.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yokoyama A, Kato H, Yokoyama T, Igaki H, Tsujinaka T, Muto M, Omori T, Kumagai Y, Yokoyama M, Watanabe H. Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 genotypes in Japanese females. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:491–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu M, Zhao JK, Hu XS, Wang PH, Qin Y, Lu YC, Yang J, Liu AM, Wu DL, Zhang ZF, Frans KJ, van' V. Association of smoking, alcohol drinking and dietary factors with esophageal cancer in high- and low-risk areas of Jiangsu Province, China. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1686–1693. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i11.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Fraumeni JF. Esophageal Cancer. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF, editors. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 697–706. [Google Scholar]

- 100.World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington DC: AICR; 2007. [Google Scholar]