Abstract

We examined DSM-IV Conduct disorder (CD) symptom criteria in a community sample of adolescent males and females to evaluate the extent to which DSM-IV criteria characterize the range of severity of adolescent antisocial behavior within and across sex.

Method

Interviews were conducted with 3208 adolescents between the ages of 11–18 years using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC). Item Response Theory (IRT) analyses were performed to obtain severity and discrimination parameters for each of the lifetime DSM-IV CD symptom criteria. Additionally, IRT-based Differential Item Functioning (DIF) analyses were conducted to examine the extent to which the symptom criteria function similarly across sex.

Results

The DSM-IV CD symptom criteria are useful and meaningful indicators of severe adolescent antisocial behavior. A single item (“Stealing without Confrontation) was a poor indicator of severe antisocial behavior. The CD symptom criteria function very similarly across sex; however, three items had significantly different severity parameters.

Conclusions

The DSM-IV CD criteria are informative as categorical and continuous measures of severe adolescent antisocial behavior; however, some CD criteria display sex-bias.

Keywords: DSM-V, Item Response Theory, Conduct Disorder, adolescent

An Item Response Theory analysis of DSM-IV Conduct Disorder Psychiatry is moving rapidly towards a revision of the diagnostic definitions of psychiatric disorders (i.e., DSM-V). This revision aims to include dimensional scaling of disorders 1, in addition to the categorical scaling used in the current system. Dimensional scaling refers to the use of symptom criteria to indicate the severity of disorder on a continuous scale, which, when compared with diagnostic categories, allows for flexibility in cutoff points for different social and clinical decisions 1 and may provide more information on disorder severity. Surprisingly, there has been little research on the extent to which the current criteria are appropriate for diagnostic categories or dimensional scaling. We use Item Response Theory (IRT) 2 to address this question for Conduct Disorder (CD).

Many researchers have conducted IRT analyses on DSM disorders such as depression 3, bulimia 4, substance use 5–7, and anxiety and mood disorders 8. To our knowledge, no prior studies have examined CD. IRT is attractive because it allows for characterization of individual item properties, dimensional scaling of the severity of traits, and can facilitate comparisons of latent trait estimates across measures with common criteria (e.g., DSM-III and DSM-IV where some criteria were added for CD).

Instead of examining only symptom count data, IRT uses additional information provided by symptom endorsement patterns because it directly models individual diagnostic criteria 9. Sets of diagnostic criteria in DSM-IV are not intended to completely describe the behavioral abnormalities of patients. Instead, they should concretely represent important aspects of those abnormalities, so that the number of criteria met by a patient reflects the severity of that patient’s disorder. However, what if one criterion reflects greater severity than another? The utility of IRT for application to psychiatric data has been previously described: “For example, two children may be similarly classified as having Conduct Disorder, one because he often lies, fights frequently, and is truant from school, and the other because he has forced someone into sexual activity, sets fires, and steals, without any clear distinction between the two in the severity ratings ascribed to each one.”10 With IRT, information regarding the severity of disorder in each patient can be obtained by examining the specific symptoms each patient endorsed.

IRT is useful for examining psychopathology for at least three reasons. First, it allows one to examine the extent to which the current diagnostic symptom criteria indicate the dimensional severity of patients’ behavioral abnormalities. For example, IRT can evaluate whether certain criteria are informative only at extreme severity levels of pathology or if they are useful for scaling severity across a wide range of pathology. Second, IRT can provide additional information about the implications of current diagnostic threshold cutoff points by characterizing the levels of psychopathology in the community. Third, IRT allows for the examination of specific properties of individual symptom criteria to test which criteria significantly indicate psychopathology, and to identify the level of severity of psychopathology at which the criteria are most informative. Thus, one can statistically compare the criteria across groups (e.g., males and females) to examine whether the symptom criteria function consistently.

In the present paper, we use IRT to examine CD. Previous research on the individual CD symptoms is limited. The current CD criteria were derived largely from research on clinical samples 11–13. Additionally, most previous studies examined samples that were too small to provide meaningful information about individual criteria.

There is also limited research on whether CD criteria are equally appropriate for girls and boys. There is a marked discrepancy in the prevalence of CD between sexes; CD occurs approximately 2–3 times as frequently in males (6–16%) compared to females (2–9%) 14, 15. The type of CD symptom criteria endorsed also varies by sex. It has been reported that males are more likely to display confrontational and aggressive behaviors (e.g., fighting, vandalism), while females are more likely to display more non-confrontational behaviors (e.g., lying, running away) 14, 16.

There are many possible explanations for the sex differences in prevalence and symptom endorsement patterns of CD. One hypothesis posits that boys and girls have alternate manifestations of the same underlying antisocial trait. This hypothesis suggests that prevalence differences exist across sex because the CD criteria are gender-biased toward the male manifestations of the trait, and behaviors typical of antisocial adolescent females are not identified 17, 18. For example, males are more likely to display overt forms of aggression, and 7 of the 15 CD symptom criteria characterize some form of aggression. In contrast, females are more likely to display relational aggression, defined as harming others through the purposeful manipulation and damage of their peer relationships 19, 20. None of the current CD symptom criteria address relational aggression. A second hypothesis posits that females are both less aggressive 21 and less antisocial, and that the prevalence differences that we observe reflect true prevalence differences across sex.

Finally, it is important to examine psychiatric diagnostic criteria in large community samples, as they may provide information that cannot be obtained solely from studies of clinical samples. Despite lower prevalence of pathology in community samples compared to clinical samples, clinical samples may contain bias due to differences in willingness, resources, or ability to seek treatment, greater severity of pathology, or due to an excess proportion of patients with comorbid disorders compared to community samples. Finally, sex differences observed within or across clinical samples may be due to either true differences in the patterns of behavior across sex or, alternatively, to the different recruiting biases for males and females.

The aim of the present study is to use IRT to examine the DSM-IV CD symptom criteria in a community sample of adolescents, to assess the suitability of the criteria in facilitating dimensional scaling of antisocial behavior (ASB), and to test for sex-differences in the criteria.

Method

Participants

Participants included 1610 male and 1598 female adolescents, aged 11–18. The sample included 1373 males from twin pairs and their non-twin brothers, and 1499 females from twin pairs and their non-twin sisters recruited through two community-based twin samples: the Colorado Longitudinal Twin Sample (LTS) 22–24 and the Colorado Community Twin Sample (CTS) 22, 24. The LTS includes twins whose emotional, cognitive and behavioral development has been studied since birth. LTS twins were identified through the Colorado Department of Health’s Division of Vital Statistics, and those that were at or beyond their 12th birthday were eligible for participation. Details of recruitment procedures and demographics are provided elsewhere 24, 25. The CTS twins were identified through the Department of Health and through 170 of 176 school districts in Colorado 24. Community-based adolescent twin samples have rates of psychopathology, including CD, that are comparable to what is found in epidemiological samples 26, and prevalence rates cited in the DSM-IV 14.

The sample also included 237 males and 99 females from a community-based control sample from the Adolescent Substance Abuse Family Study 27. The control families were chosen to have an adolescent matched in age, sex, ethnicity, and zip code to an adolescent being treated for severe substance abuse and conduct problems (the clinical adolescents were not included in the present study). Control subjects were not selected for the absence of psychopathology. For all samples, exclusion criteria included IQ scores less than 80, current cognitive problems, or other medical problems that would preclude participation. No individuals were excluded because of the presence of behavioral problems. Briefly, the sample was 82% Caucasian, 12% Hispanic, 2% African American and 4% Other. The sample had a mean age of 14.85 (S.D. = 2.12) years.

The overall sample includes many families with multiple participants. We weighted cases to correct for the non-independence of these data so that each family represented a single case in the analyses (e.g., in a family with 2 people, each case was weighted .5; in a family with 4 people, each case was weighted .25). After appropriate weighting, the overall sample size was 1408 observations. This weighting scheme was chosen rather than random selection of a single individual from each family because it allowed for inclusion of every observed response pattern into the analysis (i.e., maximum information) without allowing multiple non-independent observations from the same family to have an undue influence on the results. The mean age of the participants was 14.7 (SD 2.11) years. The sample was 82% Caucasian, 12% Hispanic, 2% African-American, and 4% multiracial or unknown.

Measures and Procedures

All participants completed the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV; 28), a structured interview that includes a module to assess lifetime DSM-IV CD criteria. Previous studies suggest that with the DISC, youths reports significantly more unique conduct disorder related information than their parents 29, and that the DISC is at least as reliable as other available child diagnostic instruments 30. Interviews were conducted by trained lay interviewers who met bi-weekly to discuss issues regarding standardization of interviews. Participants were paid a nominal fee for participation and gave written informed assent (minors) and/or consent (adults/guardians). The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Colorado.

Analyses

The IRT model and item parameter estimation

The item response theory model most appropriate for binary data such as psychopathology symptoms is the 2-parameter model (2PL) 2, 31, 32. The 2PL model can be parameterized as the probability that person s endorses item i with the equation:

where Xis represents the response of participant s to item i, θs represents the severity of antisocial pathology (i.e., the latent trait) of participant s, βi represents severity of item i, and αi represents discrimination of item i. The βi value indicates the level of severity at which, for a particular item, an individual would have a 50% chance of endorsing the item. The αi represents the ability of each criterion to discriminate between persons who are of very similar but not identical severity. The αi is analogous to a factor loading in traditional factor analysis. Hereafter, the αi parameter will be referred to as discrimination and the βi parameter will be referred to as severity.

Assumptions of the IRT model

There are two major assumptions of IRT analyses. First, the assumption of unidimensionality means that all items indicate a single latent dimension. Previous reports have satisfied the unidimensionality assumption with a preliminary factor analysis 8, 31, 33. We conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the CD symptom criteria in each sex using the Mplus software 34. Mplus allows the user to specify observed variables as categorical (dichotomous) and implements a model that allows non-linear relationships between observed and latent variables. The factor analysis was conducted using the more appropriate tetrachoric rather than Pearson correlations 33, 35. Typically in EFA, large ratios of first to second eigenvalues and a better fit of single versus multiple factor models are considered appropriate evidence for unidimensionality 8, 31, 33, 36. Demonstrating that a single factor adequately explains the data also satisfies the second assumption of local independence. This assumption means that after accounting for each item’s contribution to the CD factor, there are no residual relationships between the items.

IRT Differential Item Functioning (DIF) analyses

After IRT parameter estimation for individual items, Differential Item Functioning (DIF) analysis was conducted to examine whether the CD criteria function similarly across sex. The presence of DIF suggests an item-by-group interaction. In the 2-parameter (2PL) model, there are two potential sources of DIF 37. First, DIF in the item severity parameter (βι) suggests that symptoms are of unequal severity across sex. Second, DIF in the discrimination parameter (αι) suggests that the extent to which the symptom is related to the latent trait varies across sex. IRT parameter estimation and DIF analyses were conducted using the software PARSCALE 38. The CD criterion “Forced Sex” was not endorsed by any participants; therefore, it was not included in subsequent analyses.

Results

The overall endorsement rates of the lifetime CD symptom criteria are presented in Table 1 for each sex.

Table 1.

DIF results Males versus Females (parameters with significant DIF boxed)

| Severitya |

Discriminationb |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endorsement (%) |

Male |

Female |

Group Severity DIF |

Male |

Female |

Group Slope DIF |

||||

| DSM-IV CD criteria | Male | Female | Severity (S.E.) | Severity (S.E.) | Contrast (S.E.) | p | Slope (S.E.) | Slope (S.E.) | Contrast (S.E.) | p |

| Bully | 10.5 | 3.8 | 1.80 (0.12) | 1.86 (0.18) | 0.07 (0.22) | 0.76 | 1.00 (0.08) | 0.99 (0.09) | 0.98 (0.12) | 0.85 |

| Fights | 4.8 | 1.1 | 2.40 (0.16) | 2.56 (0.29) | 0.16 (0.33) | 0.63 | 1.05 (0.09) | 1.03 (0.10) | 0.99 (0.13) | 0.88 |

| Weapons | 8.3 | 2.8 | 2.08 (0.13) | 1.98 (0.19) | −0.10 (0.23) | 0.67 | 1.02 (0.09) | 1.06 (0.10) | 1.04 (0.12) | 0.75 |

| Cruel to People | 2.9 | 0.9 | 2.88 (0.21) | 2.71 (0.30) | −0.17 (0.37) | 0.65 | 1.00 (0.09) | 1.03 (0.10) | 1.03 (0.14) | 0.82 |

| Cruel to Animals | 9.6 | 1.3 | 2.06 (0.13) | 2.57 (0.28) | 0.52 (0.31) | 0.09 | 0.91 (0.07) | 1.03 (0.10) | 1.13 (0.14) | 0.36 |

| Steal with Confront | 1 | 0.2 | 3.01 (0.21) | 3.54 (0.52) | 0.52 (0.57) | 0.36 | 1.09 (0.10) | 1.04 (0.10) | 0.96 (0.13) | 0.74 |

| Forced Sexc | ||||||||||

| Fire Setting | 0.4 | 0.1 | 3.97 (0.38) | 3.76 (0.66) | −0.21 (0.76) | 0.77 | 1.04 (0.10) | 1.07 (0.10) | 1.03 (0.15) | 0.82 |

| Destruction of Property | 21.5 | 6.6 | 1.07 (0.08) | 1.44 (0.14) | 0.37 (0.16) | 0.02 | 1.14 (0.09) | 0.99 (0.11) | 0.87 (0.11) | 0.23 |

| B & E | 7.3 | 1.8 | 1.98 (0.12) | 2.15 (0.22) | 0.18 (0.25) | 0.49 | 1.11 (0.10) | 1.06 (0.09) | 0.96 (0.13) | 0.73 |

| Lies | 11.1 | 6.5 | 1.69 (0.11) | 1.54 (0.16) | −0.15 (0.19) | 0.43 | 0.97 (0.08) | 0.88 (0.11) | 0.90 (0.10) | 0.35 |

| Steal no Confront | 47.2 | 34.8 | 0.24 (0.06) | −0.38 (0.07) | −0.62 (0.09) | 0.00 | 0.98 (0.08) | 0.87 (0.07) | 0.88 (0.10) | 0.25 |

| Out Late | 3.3 | 0.7 | 2.75 (0.21) | 2.91 (0.38) | 0.16 (0.43) | 0.71 | 0.97 (0.09) | 1.04 (0.10) | 1.07 (0.14) | 0.62 |

| Runaway | 2.4 | 2.2 | 2.89 (0.20) | 2.13 (0.22) | −0.76 (0.30) | 0.01 | 1.02 (0.09) | 1.04 (0.10) | 1.02 (0.14) | 0.87 |

| Truant | 3.5 | 1.3 | 2.19 (0.16) | 2.23 (0.22) | 0.04 (0.27) | 0.85 | 0.83 (0.06) | 1.00 (0.09) | 1.20 (0.15) | 0.17 |

significant Differential Item Functioning (DIF) indicated by boxes

severity = the level of severity of disorder at which the item is most informative

discrimination = the relationship of the symptom to the latent trait (analagous to factor loadings from a factor analysis)

criterion was not endorsed by anyone in the sample and could not be included in the analyses

Exploratory Factor Analyses

The exploratory factor analyses suggest that, in each sex, the CD criteria comprise a single factor. The ratio of first to second eigenvalues was 3.44 and 4.05 in males and females, respectively (RMSR=.09). A single-factor confirmatory factor analysis model yields an RMSEA=.037, while the two-factor model specifying aggressive and non-aggressive subtypes yields an RMSEA=.035.

IRT item parameters

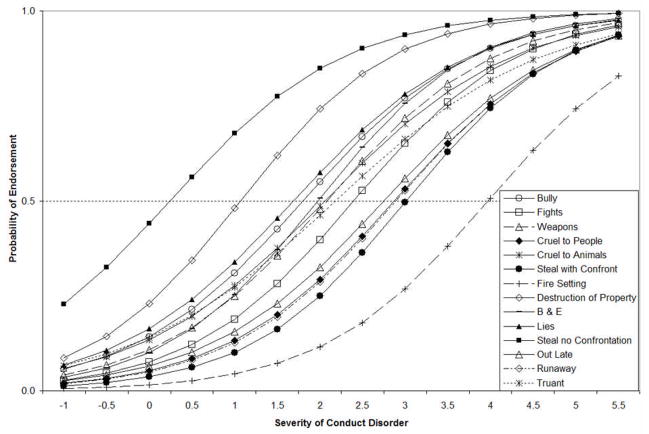

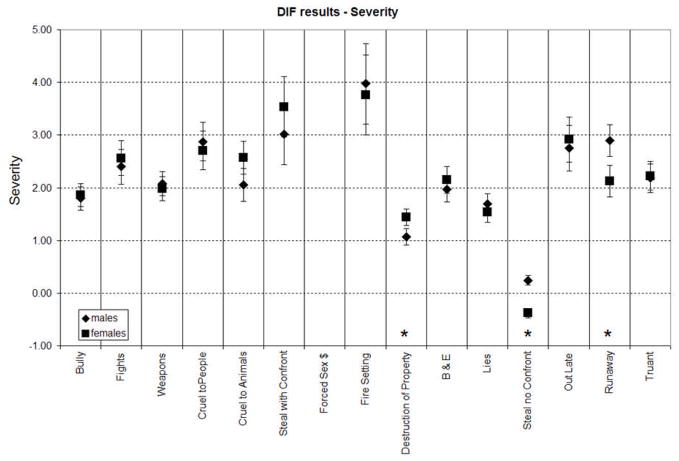

The individual item parameters with their standard errors and the DIF results with the standard error for the differences are presented in Table 1. The item characteristic curves are presented in Figure 1. Figure 2 shows the item severity parameter estimates and the confidence interval for the differences between the two sexes. The item severity parameters for the CD criteria indicate the level of the latent trait at which the criterion is most informative. For example, βi=1 suggests that criterion i is most useful for distinguishing between patients who are close to 1 standard deviation above the mean on the latent antisocial trait. Item severity parameters for the CD criteria range from 0.24 to 3.97 in males, and from −0.38 to 3.76 in females. The −0.38 item severity parameter for “Steal without Confrontation” in females means that this particular item is commonly endorsed even by those females who have lower than average antisocial behavior (i.e., 0.38 standard deviations below the mean of the latent antisocial trait). There is significant DIF across sex in the β parameters of: “Destruction of Property,” “Steal without Confrontation” and “Runaway.” The criterion “Cruel to Animals” was marginally significant (p=.09); this is notable because there is reduced power for this comparison due to low endorsement.

Figure 1.

Item Characteristic Curves for Conduct Disorder items

Figure 1 shows the item characteristic curves (ICCs) for each of the CD symptoms. On the x-axis, the severity of CD is scaled to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 in males. The severity parameter for an item can be determined by identifying the point on the x-axis where the probability of endorsement (y-axis) is 50% (indicated by a dashed line). For example, the severity parameter for “Steal no Confrontation” is 0.24. The ICCs also depict the discrimination parameters of items; ICCs with steeper slopes have higher discrimination parameters.

Figure 2.

Differential Item Functioning (DIF) results: Severity parameters (β)

Figure 2 shows the results of tests of Differential Item Functioning (DIF) for each individual CD symptom. Each item is listed across the bottom of the figure. Squares indicate the severity parameters for each item for females, severity parameters for males are indicated by diamonds. Error bars provide the standard errors for these estimates. Items with significant DIF are identified by asterisks in the lower portion of the figure. DIF suggests that items do not indicate the same level of severity in males and females.

Item discrimination parameters indicate the strength of the relationship of the individual items to the latent trait. These values are analogous to item loadings from a factor analysis. For the CD criteria, the item discrimination parameters are all close to 1.00 and there is no significant DIF for any discrimination parameters.

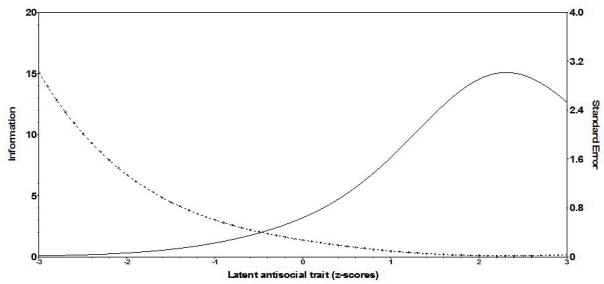

Figure 3 shows the test information curve (TIC) for this set of CD criteria. TICs indicate where the severity of disorder can be most accurately scaled across the range of the latent trait. The severity parameters for the CD criteria are in the range we would expect for a clinical measure. Nine of the 14 criteria were most informative above 2 standard deviations from the mean; the TIC reflects this showing that the CD criteria provide the best information for the dimensional scaling of individuals with severe disorder.

Figure 3.

Test information curve for DSM-IV Conduct Disorder

Figure 3 shows the test information curve (TIC) which displays how all Conduct Disorder criteria function together to provide information across the range of severity of the latent antisocial trait. X-axis = the latent antisocial trait expressed as z-scores. Solid line; left axis = total information aggregated across all Conduct Disorder criteria for each level of severity of the latent antisocial trait. Dotted line; right axis = standard error of estimation for each level of severity of the latent antisocial trait.

Discussion

The present study is an Item Response Theory (IRT)-based examination of lifetime DSM-IV Conduct Disorder (CD) symptom criteria in a community sample of adolescents. This study investigates DSM-IV CD symptom criteria as the field embarks on revision of the DSM. Examining the symptom criteria in community samples of adolescents versus clinical samples is useful because it allows us to assess the extent to which the criteria indicate severe pathology. IRT analyses can provide information regarding: the extent to which the DSM symptom criteria may be useful for the dimensional scaling of traits, the range of item severities that are indicated by the current criteria, and the extent to which the symptom criteria function similarly across distinct groups (e.g., sex). Our results suggest that: 1) CD criteria are most informative at the most severe levels of the latent antisocial trait 2) CD criteria may be useful for dimensional scaling of ASB, and 3) there are some differences in criterion functioning across sex.

CD criteria are informative for severe levels of ASB

The severity of the CD criteria, that is, the level of severity at which the criteria are most informative, varies considerably but fairly uniformly across the upper range of ASB problems (see Table 1). The item severity parameters are fairly evenly spaced between +1 and +4 standard deviations above the mean. This set of criteria is suitable for identifying extremely antisocial individuals, but may be less useful if dimensional scaling across the entire range of severity of the latent trait is desired.

The only criteria that appear to be redundant in terms of item severity level are “Weapons” and “Cruel to Animals” (β = 2.08 & 2.06, respectively). Individuals who are near two standard deviations above the mean on the latent CD scale are approximately equally likely to endorse these criteria. One exception to the relative uniformity of the item severity parameters exists for the criterion “Steal without Confrontation,” which had an extremely low item severity parameter. This behavior might deserve consideration as normative during adolescence, rather than as a criterion for a psychiatric disorder. In contrast, in a dimensional scaling system, this criterion may be important, when comparison with mean levels of the trait is desired. In our adolescent community sample, 35% of females and 45% of males endorsed this criterion; 83% of females and 71% of males who endorsed only one CD criterion endorsed “Steal without Confrontation” as their only deviant behavior.

CD IRT parameters and dimensional scaling

The test information curve (TIC) presented in Figure 3 demonstrates that the current CD symptom criteria tap a range of the latent antisocial trait, providing the most information on severity of the latent CD trait for those who are between 1.5–3 standard deviations above the mean. The TIC peaked at approximately 3 standard deviations above the mean, suggesting that dimensional scaling on this latent antisocial trait is optimal for the most severe individuals, and declines as the severity of disorder decreases. This TIC is appropriate for a set of psychiatric symptom criteria that are intended only to identify and distinguish the most severely affected individuals. However, should a dimensional scaling of antisociality across a broader range of the latent trait be desired, additional criteria at lower item severity levels (e.g., 0–1.5 standard deviations) should be added. This approach might allow for earlier “indicators” of pathology, and better dimensional scaling across the range of the latent trait. If DSM-V is to incorporate both dimensional and categorical scaling of antisociality, addition of lower item severity criteria might be necessary.

There may be additional information available from the response patterns compared with information obtained by summing the number of criteria endorsed. For example, a patient who endorses “Steal without Confrontation,” “Vandalism” and “Lies” may be considered of lower severity on the latent CD trait than a patient who endorses “Cruel to People,” “Out Late” and “Fights.” The first case endorsed the 3 least severe criteria that all have item severity parameters of less than 2 standard deviations, whereas the second case endorsed 3 of the more severe criteria with item severity parameters between 2–3 standard deviations above the mean. While this additional information might be burdensome for diagnostic purposes, it may prove useful for treatment or research.

Additionally, a useful application of the IRT-based item parameters could be employed in the absence of full or honest disclosure from patients or research participants. External reports of behaviors (e.g., specific criminal charges, family reports), though imperfect, may be considerably more informative in the context of the item characteristics. This limited information may provide at least a rough assessment of CD in people for whom limited information is available due to dishonesty, unwillingness to cooperate with clinicians or interviewers, absence, or other reasons. For example, knowledge that a patient was expelled from school for using a weapon might suggest severity of latent antisocial behavior greater than 2 standard deviations above the mean (based on “Weapons” item severity parameter of ~ 2.05).

One criterion, “Forced Sex” was not included in our IRT analysis because it was not endorsed by anyone in our sample. “Forced Sex” may be a criterion that is indicative of ASB, but the extremely low prevalence results in this symptom having limited utility as a CD criterion for diagnosis based on self-report.

Differential Item Functioning - CD criteria display some differences across sex

In general, the CD criteria provided the same information in both male and female adolescents. However, there were 3 criteria with significant differences in item severity parameters across sex. As shown in Figure 2, these criteria were “Destruction of Property,” “Steal without Confrontation” and “Runaway.” “Destruction of Property” was less severe in males. In contrast, the other two criteria (“Steal without Confrontation” and “Runaway”) were significantly less severe in females. These results are consistent with reported differences in the types of behaviors typically displayed by each sex (i.e., females showing more non-aggressive behaviors).

Surprisingly, the results do not show statistically significant sex differences in item severity for most aggressive criteria (e.g., “Fights,” etc.). Rather than find CD criteria that were gender-biased toward male manifestations of the CD trait, the analyses suggest that two criteria (“Steal without Confrontation” and “Runaway”) are, in fact, gender-biased toward females. In other words, females are more likely to endorse these particular criteria when they are of lower severity on the latent antisocial trait. There are some potential explanations for these findings. For example, the criterion “Runaway” may reflect that females who are not highly antisocial might run away from home for reasons other than antisociality, such as to escape a sexually abusive relationship in the home.

The statistically significant sex difference in the item severity parameter for “Steal without Confrontation” further reinforces that this criterion may not be ideal for assessing CD. The magnitude of the difference in item severity parameters for the criteria showing DIF ranged from .37 to .76 standard deviations. There were no criteria that appeared extremely different across sex, suggesting that the current CD criteria do not have any single criterion that is substantially sex-biased.

CD symptom criteria tend to have far greater endorsement rates in males, yet most criteria show similar item severity parameters across the two genders. DIF analyses account for overall mean gender differences. After controlling for these mean differences, these analyses suggest that the majority of CD symptom criteria are not sex-biased despite sex differences in average severity for the latent trait. This result supports the hypothesis that males are generally more aggressive and more antisocial than females rather than males and females displaying alternate manifestations of the same underlying antisocial trait.

Differences in item functioning across sex do not automatically imply that the criteria should be eliminated from the DSM criteria. DIF may indicate real differences in the criteria based on sex, or alternatively, DIF may indicate that the criteria are poorly operationalized or worded. Researchers attempting to improve clinical criteria may choose to rework these criteria to more precisely target the construct of interest, or conversely, seek to examine whether biological and/or social factors are contributing to the observed differences.

The results of the present study should be considered in view of the following limitations. First, the analyses were conducted on a community sample with limited representation of the most severe end of the antisocial spectrum. This may have resulted in decreased power to detect significant differences. Second, the interview used to assess the CD criteria represents one operationalization of the DSM-IV CD criteria and the results should be interpreted in this context. Third, we limited our investigation to lifetime criteria because this provided sufficient statistical power in our community sample.

This study has substantial clinical implications. First, it emphasizes that certain CD behaviors are more likely than others to represent severe antisocial status. Thus, while “Stealing without Confrontation” may be almost normative in adolescence, “Stealing with Confrontation” may be indicative of serious ASB. Clinicians should consider both the item severity (i.e., the severity of endorsed behaviors) and the patterns of symptom endorsement of CD youth when assessing the disorder, and not focus solely on the diagnostic status. Further supporting this approach is the finding that the CD criteria differentially predict the severity and the persistence of ASB into adulthood 39. The results suggest that future editions of DSM might successfully incorporate a more dimensional model of antisocial and externalizing behavior 40, 41. For example, symptom threshold cutoff values and symptom endorsement patterns might be considered conjointly and viewed as complimentary and mutually valuable sources of information.

To our knowledge, this study is the first IRT–based analysis of DSM-IV CD. The results suggest that the current conceptualization of CD is based on symptom criteria that vary uniformly and meaningfully across the most severe range of the antisocial trait. The current symptom criteria may provide a firm basis for dimensional scaling of adolescent ASB. As expected of clinical criteria, the criteria are most informative at severe levels of the latent trait, suggesting that if dimensional scaling of the entire range of the latent trait is desired, additional criteria assessing less severe pathology should be added. Additionally, the CD symptom criteria (operationalized by DISC) appear to be substantially, but not perfectly, consistent across sex. Results of this study largely support the utility and appropriateness of the current diagnostic criteria and provide information for revisions of the DSM and investigations into sex differences in CD.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported through the following NIH grants DA-011015, DA-012845, DA-016314 and DA-015522, MH-01865.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Crowley’s past consultations to Wayne State University and CRS Associates were funded by Reckitt Benkiser Pharmaceuticals.

The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Widiger TA, Simonsen E, Krueger R, Livesley WJ, Verheul R. Personality disorder research agenda for the DSM-V. J Personal Disord. 2005 Jun;19(3):315–338. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.3.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lord FM, Novick MR. Statistical theories of mental test scores. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aggen SH, Neale MC, Kendler KS. DSM criteria for major depression: evaluating symptom patterns using latent-trait item response models. Psychol Med. 2005 Apr;35(4):475–487. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowe R, Pickles A, Simonoff E, Bulik CM, Silberg JL. Bulimic symptoms in the Virginia Twin Study of Adolescent Behavioral Development: correlates, comorbidity, and genetics. Biol Psychiatry. 2002 Jan 15;51(2):172–182. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Martin C, Mezzich A, Brown S. Application of item response theory to quantify substance use disorder severity. Addict Behav. 2006 Jun;31(6):1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin CS, Chung T, Kirisci L, Langenbucher JW. Item response theory analysis of diagnostic criteria for alcohol and cannabis use disorders in adolescents: implications for DSM-V. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006 Nov;115(4):807–814. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saha TD, Chou SP, Grant BF. Toward an alcohol use disorder continuum using item response theory: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006 Jul;36(7):931–941. doi: 10.1017/S003329170600746X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krueger RF, Finger MS. Using item response theory to understand comorbidity among anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Psychol Assess. 2001 Mar;13(1):140–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bock RD, Gibbons R, Muraki EJ. Full information item factor analysis. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1988;12:261–280. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bird HR, Shrout PE, Davies M, et al. Longitudinal development of antisocial behaviors in young and early adolescent Puerto Rican children at two sites. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Jan;46(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242243.23044.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lahey BB, Loeber R, Quay HC, et al. Validity of DSM-IV subtypes of conduct disorder based on age of onset. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(4):435–442. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199804000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams JB, Spitzer RL. Research diagnostic criteria and DSM-III: an annotated comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982 Nov;39(11):1283–1289. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290110039007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frick PJ, Lahey BB, Applegate B, et al. DSM-IV field trials for the disruptive behavior disorders: symptom utility estimates. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33(4):529–539. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199405000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2004. (DSM-IV) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Prevalence, subtypes, and correlates of DSM-IV conduct disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med. 2006 May;36(5):699–710. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelhorn HL, Stallings MC, Young SE, Corley RP, Rhee SH, Hewitt JK. Genetic and environmental influences on conduct disorder: symptom, domain and full-scale analyses. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;46(6):580–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoccolillo M. Gender and the development of conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:65–78. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohan JL, Johnston C. Gender appropriateness of symptom criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional-defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2005 Summer;35(4):359–381. doi: 10.1007/s10578-005-2694-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crick NR, Casas JF, Mosher M. Relational and overt aggression in preschool. Dev Psychol. 1997 Jul;33(4):579–588. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Dev. 1995 Jun;66(3):710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maccoby EE, Jacklin CN. Sex differencecs in aggression: A rejoinder and reprise. Child Dev. 1980;51:964–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young SE, Stallings MC, Corley RP, Krauter KS, Hewitt JK. Genetic and environmental influences on behavioral disinhibition. Am J Med Genet. 2000;96(5):684–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson JL, McGrath J, Corley RP. The Conduct of the Study. In: Emde RN, Hewitt JK, editors. Infancy to Early Childhood: Genetic and Environmental Influences on Developmental Change. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhea SA, Gross AA, Haberstick BC, Corley RP. Colorado Twin Registry. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006 Dec;9(6):941–949. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plomin R, Campos J, Corely RP, et al. Individual differences during the second year of life: the MacArthur Longitudinal Twins Study. In: Colombo J, Fagan J, editors. Individual differences in infancy: reliability, stability, prediction. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1990. pp. 431–455. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hewitt JK, Silberg JL, Rutter M, et al. Genetics and developmental psychopathology: 1. Phenotypic assessment in the Virginia Twin Study of Adolescent Behavioral Development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(8):943–963. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miles DR, Stallings MC, Young SE, Hewitt JK, Crowley TJ, Fulker DW. A family history and direct interview study of the familial aggregation of substance abuse: the adolescent substance abuse study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;49(2):105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000 Jan;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colins O, Vermeiren R, Schuyten G, Broekaert E, Soyez V. Informant agreement in the assessment of disruptive behavior disorders in detained minors in Belgium: a diagnosis-level and symptom-level examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008 Jan;69(1):141–148. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts RE, Solovitz BL, Chen YW, Casat C. Retest stability of DSM-III-R diagnoses among adolescents using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-2.1C) J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1996 Jun;24(3):349–362. doi: 10.1007/BF01441635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reise SP, Waller NG. How many IRT parameters does it take to model psychopathology items? Psychol Methods. 2003 Jun;8(2):164–184. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.8.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Embretson SE, Reise SP. Item response theory for psychologists. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langenbucher JW, Labouvie E, Martin CS, et al. An application of item response theory analysis to alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine criteria in DSM-IV. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004 Feb;113(1):72–80. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mplus [computer program]. Version. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hulin CL, Drasgow F, Parsons CK. Item response theory: application to psychological measurement. Homewood, Ill: Dow-Jones Irwin; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirisci L, Vanyukov M, Dunn M, Tarter R. Item response theory modeling of substance use: an index based on 10 drug categories. Psychol Addict Behav. 2002;16(4):290–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thissen D, Steinberg L, Gerrard M. Beyond group mean differences: The concept of item bias. Psychol Bull. 1986;99:118–128. [Google Scholar]

- 38.PARSCALE [computer program]. Version. Chicago: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gelhorn HL, Sakai JT, Price RK, Crowley TJ. DSM-IV conduct disorder criteria as predictors of antisocial personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2007 Nov-Dec;48(6):529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferdinand RF, Visser JH, Hoogerheide KN, et al. Improving estimation of the prognosis of childhood psychopathology; combination of DSM-III-R/DISC diagnoses and CBCL scores. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004 Mar;45(3):599–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Iacono WG. Externalizing psychopathology in adulthood: a dimensional-spectrum conceptualization and its implications for DSM-V. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005 Nov;114(4):537–550. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]