Abstract

AIM: To study the prevalence and risk factors associated with triple infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/hepatitis B virus (HBV)/hepatitis C virus (HCV) in an urban clinic population.

METHODS: Retrospective chart review of 5639 patients followed at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital HIV Clinic (Center for Comprehensive Care) in New York City, USA from January 1999 to May 2007. The following demographic characteristics were analyzed: age, sex, race and HIV risk factors. A multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the influence of demographic factors on acquisition of these viruses.

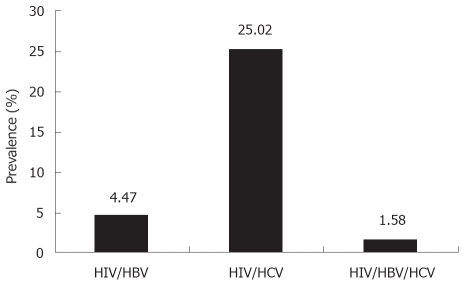

RESULTS: HIV/HBV, HIV/HCV and HIV/HBV/HCV infections were detected in 252/5639 (4.47%), 1411/5639 (25.02%) and 89/5639 (1.58%) patients, respectively. HIV/HBV co-infections were associated with male gender (OR 1.711; P = 0.005), black race (OR 2.091; P < 0.001), men having sex with men (MSM) (OR 1.747; P = 0.001), intravenous drug use (IDU) (OR 0.114; P < 0.001), IDU and heterosexual activity (OR 0.247; P = 0.018), or unknown (OR 1.984; P = 0.004). HIV/HCV co-infections were associated with male gender (OR 1.241; P = 0.011), black race (OR 0.788; P = 0.036), MSM (OR 0.565; P < 0.001), IDU (OR 8.956; P < 0.001), IDU and heterosexual activity (OR 9.106; P < 0.001), IDU and MSM (OR 9.179; P < 0.001), or transfusion (OR 3.224; P < 0.001). HIV/HBV/HCV co-infections were associated with male gender (OR 2.156; P = 0.015), IDU (OR 6.345; P < 0.001), IDU and heterosexual activity (OR 9.731; P < 0.001), IDU and MSM (OR 9.228; P < 0.001), or unknown (OR 4.219; P = 0.007).

CONCLUSION: Our study demonstrates that co-infection with HBV/HCV/HIV is significantly associated with IDU. These results highlight the need to intensify education and optimal models of integrated care, particularly for populations with IDU, to reduce the risk of viral transmission.

Keywords: Prevalence, Demographics, Human immunodeficiency virus, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C

INTRODUCTION

Co-infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is common and well-recognized worldwide, as they are blood-borne pathogens that share similar routes of transmission, such as intravenous drug use (IDU), sexual contact, percutaneous exposure, or from mother to child during pregnancy or birth[1]. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization estimate that 1.2 million people live with HIV in the United States of America (US)[2]. Among HIV-infected patients studied from Western Europe and the US, chronic HBV infection has been found in 6%-14%, while chronic HCV has been found in approximately 33%[3,4]. Co-infections of HBV or HCV with HIV have been associated with increased risk of antiretroviral-therapy-related hepatotoxicity and increased risk of progression to liver disease, which is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected patients[5-8]. It is well known that in the US and Europe, HIV/HBV co-infection is linked most often to sexual intercourse [both heterosexual and men who have sex with men (MSM)], followed by IDU, while HIV/HCV co-infection has predominantly been associated with a non-sexual parenteral route of transmission of blood or blood products, particularly IDU[9-13]. Although the rate of HBV and/or HCV co-infection in HIV patients varies according to geographic region and various risk groups, there is limited data on the prevalence and risk factors associated with triple infections with HIV/HBV/HCV in an urban clinic population. Therefore, we investigated the co-infection patterns of HBV and HCV among HIV-infected patients coming to a HIV clinic located in New York City, to determine the prevalence and risk factors associated with triple infections with HIV/HBV/HCV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

We conducted a retrospective chart review of 5639 patients followed in two HIV/AIDS clinics that comprise the Center for Comprehensive Care at St. Luke’s–Roosevelt Hospital in New York City. The study period was from January 1999 to May 2007. All patients were HIV-infected and were analyzed for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and HCV antibody, along with demographic characteristics and risk factors for HIV acquisition.

Virological assays

HIV infection was defined by positivity on an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (HIVABTM HIV-1/HIV-2 (rDNA) EIA, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) and confirmatory Western Blot test (HIV 1/HIV 2 WESTERN BLOT/IMMUNOBLOT, Quest Diagnostics, USA) with viral detection of HIV RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Roche HIV-1 Amplicor Monitor , version 1.5, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland).

HCV serology was performed using an ELISA (VITROSR Immunodiagnostics, Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, USA). Positive HCV serology results were confirmed by PCR test [VERSANTR HCV RNA 3.0 Assay (bDNA); Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, USA]. HBV serology was performed using ELISA (VITROSR Immunodiagnostics, Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics).

HIV/HBV, HIV/HCV, and HIV/HBV/HCV co-infections were defined as positive HIV and HBV serology, positive HIV and HCV serology, and positive HIV and HBV and HCV serology results, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The tables describe the distribution of co-infections among HIV-infected patients according to several characteristics. The χ2 test was performed in order to investigate the association between the presence of HIV/HBV/HCV co-infections and demographic variables. The Fisher exact test was used where applicable. In order to identify factors associated with HIV/HBV, HIV/HCV and HIV/HBV/HCV co-infections, three multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to determine odd ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The level of statistical significance was fixed at P = 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Epidemiological characteristics

Of the 5639 HIV-infected patients investigated, 1752 (31.07%) were co-infected with hepatitis viruses [252/5639 (4.47%) HIV/HBV, 1411/5639 (25.02%) HIV/HCV, and 89/5639 (1.58%) HIV/HBV/HCV]. The main epidemiological demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Epidemiological demographic characteristics of HIV, HIV/HBV, HIV/HCV and HIV/HBV/HCV n (%)

| HIV | HIV/HBV | HIV/HCV | HIV/HBV/HCV | |

| Number of patients and prevalence | 3887 (68.93) | 252 (4.47) | 1411 (25.02) | 89 (1.58) |

| Mean age (yr) | 45.0 | 44.2 | 50.4 | 47.8 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1266 (32.6) | 48 (19.0) | 392 (27.8) | 13 (14.6) |

| Male | 2583 (66.5) | 203 (80.6) | 1005 (71.2) | 75 (84.3) |

| Male->Female or Female->Male | 38 (1.0) | 1 (0.4) | 14 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Ethnic group | ||||

| White | 551 (14.2) | 34 (13.5) | 203 (14.4) | 16 (18.0) |

| Hispanic | 1267 (32.6) | 44 (17.5) | 553 (39.2) | 34 (38.2) |

| African American | 1951 (50.2) | 169 (67.1) | 630 (44.6) | 39 (43.8) |

| Other | 118 (3.0) | 5 (2.0) | 25 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Risk factor of HIV acquisition | ||||

| Hetero | 1683 (43.3) | 90 (35.7) | 285 (20.2) | 9 (10.1) |

| MSM | 1233 (31.7) | 117 (46.4) | 148 (10.5) | 17 (19.1) |

| Hetero and MSM | 38 (1.0) | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| IDU | 407 (10.5) | 6 (2.4) | 702 (49.8) | 38 (42.7) |

| IDU and hetero | 90 (2.3) | 3 (1.2) | 165 (11.7) | 13 (14.6) |

| IDU and MSM | 24 (0.6) | 3 (1.2) | 57 (4.0) | 5 (5.6) |

| IDU and hetero and MSM | 6 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Transfusion | 36 (0.9) | 3 (1.2) | 21 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Perinatal | 101 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 31 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Unknown | 238 (6.1) | 26 (10.3) | 32 (2.3) | 6 (6.7) |

Data are number (%) of patients, unless otherwise indicated. Hetero, heterosexual; Other, including sexually abused, transfusion, needle stick injury.

HIV and HBV co-infection

Of the 252 HIV/HBV co-infected patients, the majority was male (203/252, 80.6%). Mean age was 44.2 years old. Black race was dominant (169/252, 67.1%). Risk factors for acquisition of HIV included: heterosexual contact (35.7%), MSM (46.4%) and IDU (2.4%). The results of the multiple regression analyses are presented in Table 2. HIV/HBV co-infections were associated with male gender (OR 1.711; 95% CI 1.179-2.482; P = 0.005), Black race (OR 2.091; 95% CI 1.404-3.114; P < 0.001), MSM (OR 1.747; 95% CI 1.247-2.448; P = 0.001), IDU (OR 0.114; 95% CI 0.049-0.262; P < 0.001), IDU and heterosexual activity (OR 0.247; 95% CI 0.077-0.789; P = 0.018), or unknown (OR 1.984; 95% CI 1.249-3.153; P = 0.004).

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression analysis of factors associated with HIV/HBV, HIV/HCV, and HIV/HBV/HCV co-infection

|

HIV/HBV |

HIV/HCV |

HIV/HBV/HCV |

||||

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female (Ref) | ||||||

| Male | 1.711 (1.179-2.482) | 0.005 | 1.241 (1.052-1.464) | 0.011 | 2.156 (1.159-4.011) | 0.015 |

| Male->Female or Female->Male | 0.399 (0.053-3.020) | 0.374 | 1.978 (0.939-4.167) | 0.073 | 2.091 (0.250-17.529) | 0.496 |

| Ethnic group | ||||||

| White (Ref) | ||||||

| Hispanic | 0.766 (0.480-1.222) | 0.263 | 0.956 (0.761-1.201) | 0.699 | 0.915 (0.492-1.702) | 0.779 |

| Black | 2.091 (1.404-3.114) | < 0.001 | 0.788 0.631-0.984) | 0.036 | 0.851 (0.464-1.561) | 0.602 |

| Other | 0.811 (0.309-2.125) | 0.670 | 0.827 (0.493-1.388) | 0.473 | 0.000 (0.000- . ) | 0.996 |

| Risk factor of HIV aquisition | ||||||

| Hetero (Ref) | ||||||

| MSM | 1.747 (1.247-2.448) | 0.001 | 0.565 (0.446-0.715) | < 0.001 | 1.798 (0.763-4.238) | 0.180 |

| Hetero and MSM | 1.371 (0.408-4.606) | 0.610 | 0.000 (0.000- . ) | 0.998 | 0.000 (0.000- . ) | 0.998 |

| IDU | 0.114 (0.049-0.262) | < 0.001 | 8.956 (7.502-10.693) | < 0.001 | 6.345 (3.015-13.351) | < 0.001 |

| IDU and hetero | 0.247 (0.077-0.789) | 0.018 | 9.106 (6.905-12.007) | < 0.001 | 9.731 (4.082-23.196) | < 0.001 |

| IDU and MSM | 0.714 (0.217-2.344) | 0.578 | 9.179 (5.767-14.609) | < 0.001 | 9.228 (2.897-29.391) | < 0.001 |

| IDU and hetero and MSM | 0.000 (0.000- . ) | 0.999 | 0.900 (0.107-7.550) | 0.923 | 0.000 (0.000- . ) | 0.999 |

| Transfusion | 1.161 (0.354-3.807) | 0.806 | 3.224 (1.866-5.572) | < 0.001 | 0.000 (0.000- . ) | 0.998 |

| Perinatal | 0.000 (0.000- . ) | 0.996 | 0.000 (0.000- . ) | 0.996 | 0.000 (0.000- . ) | 0.997 |

| Other | 0.594 (0.080-4.437) | 0.612 | 0.000 (0.000- . ) | 0.998 | 5.857 (0.715-47.994) | 0.100 |

| Unknown | 1.984 (1.249-3.153) | 0.004 | 0.703 (0.476-1.039) | 0.077 | 4.219 (1.478-12.044) | 0.007 |

HIV and HCV co-infection

The majority of patients were male (1005/1411, 71.2%). Mean age was 50.4 years old. Hispanic and black ethnic group constituted the majority (553/1411 39.2%, 630/1411 44.6%, respectively). Concerning the risk factors of acquiring HIV, 702 patients (49.8%) reported IDU and 148 patients (10.5%) reported MSM.

Table 2 illustrates the factors associated with HIV/HCV co-infection, which show that co-infections were significantly associated with male gender (OR 1.241; 95% CI 1.052-1.464; P = 0.011), Black race (OR 0.788; 95% CI 0.631-0.984; P = 0.036), MSM (OR 0.565; 95% CI 0.446-0.715; P < 0.001), IDU (OR 8.956; 95% CI 7.502-10.693; P < 0.001), IDU and heterosexual activity (OR 9.106; 95% CI 6.905-12.007; P < 0.001), IDU and MSM (OR 9.179; 95% CI 5.767-14.609; P < 0.001), transfusion (OR 3.224; 95% CI 1.866-5.572; P < 0.001).

HIV and HBV/HCV co-infection

The prevalence of triple co-infection was found to be 1.58% (89/5639). Mean age was 47.8 years old and the majority was male (75/89, 84.3%). Hispanic and black ethnic group constituted the majority (34/89 38.2%, 39/89 43.8%). Regarding the risk factors of HIV acquisition, 38 patients (42.7%) reported IDU and 17 (19.1%) reported MSM.

The multiple regression analysis showed that factors associated with triple infections with HIV/HBV/HCV, were male gender (OR 2.156; 95% CI 1.159-4.011; P = 0.015), IDU (OR 6.345; 95% CI 3.015-13.351; P < 0.001), IDU and heterosexual activity (OR 9.731; 95% CI 4.082-23.196; P < 0.001), IDU and MSM (OR 9.228; 95% CI 2.897-29.391; P < 0.001), or unknown (OR 4.219; 95% CI 1.478-12.044; P = 0.007).

DISCUSSION

Our clinics serve a large number of diverse HIV-infected populations in New York City. Most of our patients are men, black and Hispanic, which reflects the national epidemic of HIV infection[2]. In our study period of 8.5 years and the review of 5639 HIV-infected patients, as Figure 1 shows, the prevalence of HIV/HCV co-infection was remarkably high, at 25.02%. Co-infection with HBV was not uncommon, at 4.47%, and triple co-infected patients with HIV/HBV/HCV were not rare either, at 1.58%.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of HIV and HBV and/or HCV co-infections (%).

The results of the present study are consistent with previous studies conducted in urban HIV/HBV or HCV co-infected populations in the US and Western Europe[14,15].

In our study, HIV/HBV co-infection was more likely associated with male gender, black race and MSM, but less likely associated with IDU, and IDU plus heterosexual activity, than with heterosexual reference. These results are consistent with previous studies, demonstrating that HIV/HBV co-infection is highly linked to sexual intercourse, including MSM.

In our study, HIV/HCV co-infection was significantly associated with male gender, IDU, IDU plus heterosexual activity, IDU plus MSM, and transfusion, but less likely associated with black race and MSM than heterosexual reference. These results are in agreement with previous reports that HCV is not efficiently transmitted by perinatal or sexual exposure, which are major modes of transmission for HBV and HIV. HCV is predominantly found in persons who have had percutaneous exposure to blood products and IDU in particular[16]. Even though we did not analyze patients for unsafe sexual practices, recent evidence shows increased incidence of HCV infection in MSM population who do not use condoms, especially young individuals, and in the heterosexual population who report multiple sexual partners[17]. 10.5% and 20.2% of our HIV/HCV co-infected patients are MSM and heterosexual, respectively. Not counting for other possible risk factors, sexual acquisition of HCV is likely very important in HIV-infected MSM and heterosexual individuals with multiple partners.

The prevalence of triple infection with HIV/HBV/HCV in our cohort was 1.58% and significantly associated with male gender, IDU, IDU plus heterosexual activity, and IDU plus MSM. Our results demonstrate that IDU is the most important factor associated with triple infections with HIV/HBV/HCV in urban HIV-infected populations. Therefore, the study results highlight the need for special attention to populations with IDU for screening viral co-infections with HIV and HBV/HCV.

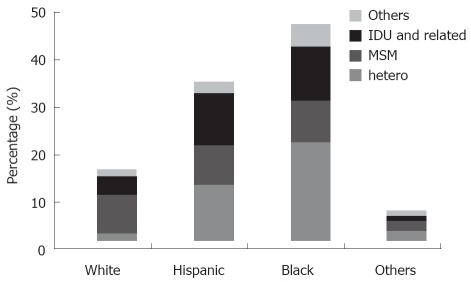

Interestingly, among intravenous drug users, we found that the prevalence of IDU in heterosexuals was significantly higher than that of MSM with a history of IDU in HIV/HBV/HCV and HIV/HCV co-infected patients (14.6% vs 5.6% P < 0.001, 11.7% vs 4% P < 0.001), which is consistent with previous studies conducted in the US[18,19]. This could be explained by fewer high-risk IDU practices, such as needle sharing, among MSM in our cohort, although IDU behavior was not assessed in our study. As Figure 2 illustrates, overall IDU-related prevalence in our cohort was 26.49%, 32.14%, 24.31% in white, Hispanic and black ethnic groups, respectively. Our findings contrast with recent data, in which blacks were more likely to inject than whites, while Hispanics and whites had similar injecting rates[20]. This indicates another example of considerable variations in disparities of IDU in ethnic groups in large urban US cities.

Figure 2.

Ethnicity-related distribution of HIV acquisition risk factors of HIV and HBV and/or HCV co-infected patients.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic in the US affects ethnic and racial groups disproportionally. This was clearly depicted in our study. Co-infection with hepatotropic viruses shows similar trends. Physicians who care for patients with HIV/AIDS should be vigilant to frequently screen for these infections and vaccinate for hepatitis A and B when appropriate. Also, our study demonstrates that co-infection with all three viruses, HIV/HBV/HCV, is significantly associated with IDU. These results highlight the need to intensify risk reduction education, such as needle exchange programs, safe sex programs, and optimal models of integrated care, particularly for populations with IDU, to reduce the risk of viral transmission of HIV and hepatotropic viruses.

COMMENTS

Background

Co-infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients has been recognized worldwide. HIV and hepatitis co-infections have considerable impact, and result in increased morbidity and mortality in these co-infected patients. However, there are limited data on prevalence and risk factors associated with triple co-infections with HIV/HBV/HCV in an urban clinic population.

Research frontiers

To investigate epidemiological characteristics of triple co-infected patients with HIV/HBV/HCV.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In this study, the prevalence of triple co-infected patients was 1.58% and it was significantly associated with male gender and intravenous drug use (IDU). The prevalence of HIV and HCV co-infected patients was 25.02%, and it was associated with male gender and IDU. Whereas, the prevalence of HIV and HBV co-infected patients was 4.47% and was associated with male gender, black race, and MSM, but not likely associated with IDU than heterosexual reference.

Applications

This study demonstrates that triple co-infections with HIV/HBV/HCV are significantly associated with IDU. Therefore, education and integrated care, particularly for populations with IDU, would help reduce the risk of viral infections.

Peer review

This is an interesting paper. The authors demonstrated that co-infection with all three viruses, HBV/HCV/HIV, is significantly associated with IDU. These results highlight the need to intensify education and optimal models of integrated care, particularly for populations with IDU, to reduce the risk of viral transmission.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to J Park and T Robinson from the Center for Comprehensive Care at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital in New York City for assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Rosemar Joyce Burnett, PhD, Department of Epidemiology, National School of Public Health, University of Limpopo, Medunsa Campus, PO Box 173, MedunsA, Pretoria 0204, South Africa

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Koziel MJ, Peters MG. Viral hepatitis in HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1445–1454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra065142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) AIDS Epidemic Update Regional Summary: North America, Western and Central Europe. Genena, UNAIDS/08.14E, 2008. Available from: URL: http://www.unaids.org.

- 3.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol. 2006;44:S6–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulkowski MS. Viral hepatitis and HIV coinfection. J Hepatol. 2008;48:353–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber R, Sabin CA, Friis-Møller N, Reiss P, El-Sadr WM, Kirk O, Dabis F, Law MG, Pradier C, De Wit S, et al. Liver-related deaths in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: the D:A:D study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1632–1641. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gebo KA, Diener-West M, Moore RD. Hospitalization rates differ by hepatitis C satus in an urban HIV cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34:165–173. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200310010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham CS, Baden LR, Yu E, Mrus JM, Carnie J, Heeren T, Koziel MJ. Influence of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the course of hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:562–569. doi: 10.1086/321909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sulkowski MS, Thomas DL, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Hepatotoxicity associated with antiretroviral therapy in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus and the role of hepatitis C or B virus infection. JAMA. 2000;283:74–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas DL, Cannon RO, Shapiro CN, Hook EW 3rd, Alter MJ, Quinn TC. Hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and human immunodeficiency virus infections among non-intravenous drug-using patients attending clinics for sexually transmitted diseases. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:990–995. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilson RJ, Hawkins AE, Beecham MR, Ross E, Waite J, Briggs M, McNally T, Kelly GE, Tedder RS, Weller IV. Interactions between HIV and hepatitis B virus in homosexual men: effects on the natural history of infection. AIDS. 1997;11:597–606. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kellerman SE, Hanson DL, McNaghten AD, Fleming PL. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B and incidence of acute hepatitis B infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:571–577. doi: 10.1086/377135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodríguez-Méndez ML, González-Quintela A, Aguilera A, Barrio E. Prevalence, patterns, and course of past hepatitis B virus infection in intravenous drug users with HIV-1 infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1316–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, Rajicic N. Hepatitis C Virus prevalence among patients infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the US adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:831–837. doi: 10.1086/339042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thio CL. Hepatitis B in the human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient: epidemiology, natural history, and treatment. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:125–136. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rockstroh JK, Mocroft A, Soriano V, Tural C, Losso MH, Horban A, Kirk O, Phillips A, Ledergerber B, Lundgren J. Influence of hepatitis C virus infection on HIV-1 disease progression and response to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:992–1002. doi: 10.1086/432762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wasley A, Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C: geographic differences and temporal trends. Semin Liver Dis. 2000;20:1–16. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alter MJ, Hadler SC, Judson FN, Mares A, Alexander WJ, Hu PY, Miller JK, Moyer LA, Fields HA, Bradley DW. Risk factors for acute non-A, non-B hepatitis in the United States and association with hepatitis C virus infection. JAMA. 1990;264:2231–2235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogt RL, Richmond-Crum S, Diwan A. Hepatitis C virus infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive cohort in Hawaii. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:542–543. doi: 10.1086/517287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tedaldi EM, Hullsiek KH, Malvestutto CD, Arduino RC, Fisher EJ, Gaglio PJ, Jenny-Avital ER, McGowan JP, Perez G. Prevalence and characteristics of hepatitis C virus coinfection in a human immunodeficiency virus clinical trials group: the Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1313–1317. doi: 10.1086/374841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper H, Friedman SR, Tempalski B, Friedman R, Keem M. Racial/ethnic disparities in injection drug use in large US metropolitan areas. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]