Abstract

AIM: To introduce and evaluate the efficacy and technical aspects of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) using a novel device, the Fork knife.

METHODS: From March 2004 to April 2008, ESD was performed on 265 gastric lesions using a Fork knife (Endo FS®) (group A) and on 72 gastric lesions using a Flexknife (group B) at a single tertiary referral center. We retrospectively compared the endoscopic characteristics of the tumors, pathological findings, and sizes of the resected specimens. We also compared the en bloc resection rate, complete resection rate, complications, and procedure time between the two groups.

RESULTS: The mean size of the resected specimens was 4.27 ± 1.26 cm in group A and 4.29 ± 1.48 cm in group B. The en bloc resection rate was 95.8% (254/265 lesions) in group A and 93.1% (67/72) in group B. Complete ESD without tumor cell invasion of the resected margin was obtained in 81.1% (215/265) of group A and in 73.6% (53/72) of group B. The perforation rate was 0.8% (2/265) in group A and 1.4% (1/72) in group B. The mean procedure time was 59.63 ± 56.12 min in group A and 76.65 ± 70.75 min in group B (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: The Fork knife (Endo FS®) is useful for clinical practice and has the advantage of reducing the procedure time.

Keywords: Fork knife, Novel device, Endoscopic submucosal dissection, Flexknife, Procedure time

INTRODUCTION

The emergence of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has allowed the achievement of histologically complete en bloc resection of gastric tumors regardless of size, which permits the resection of previously non-resectable tumors[1-4]. Although the fundamental incision and dissection method are the same for all ESD procedures, ESD can be classified by the type of knife that is used; for example, an IT knife (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan)[5-8], a Flexknife (Olympus Co.)[9], or a Hook knife (Olympus Co.)[10]. Each step of ESD, such as marking of a lesion, injection, incision and dissection, may require a different accessory or a knife, depending on the location and shape of the tumor[11]. Therefore, when performing ESD, the accessories may be frequently changed through the working channel of the endoscope[12,13], which results in a longer procedure time and a delay in controlling gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. A two-channel endoscope can use one accessory or two accessories at the same time during a procedure[14]. However, two-channel endoscopes have a thicker diameter, which may cause additional discomfort to the patient and impede the field of view in some situations. Consequently, the development of an instrument capable of multiple functions, such as injection, incision, dissection, coagulation, and irrigation, without the need for changing accessories is an attractive idea.

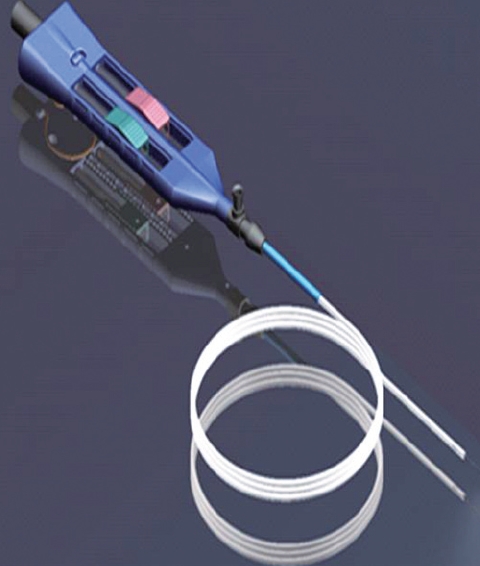

The Fork knife (Endo FS®; Kachu Technology Co., Seoul, Korea) is a device that was developed to enable an endoscopist to perform the multiple steps of ESD without the need to change accessories during the procedure. The Fork knife is capable of performing every step of ESD, including marking, injection, saline irrigation, and coagulation, and thus may enable the endoscopist to reduce the procedure time.

The aim of the present study was to introduce and evaluate the efficacy and technical aspects of ESD performed with a Fork knife, which we made ourselves in cooperation with the Kachu Technology Company.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fork knife

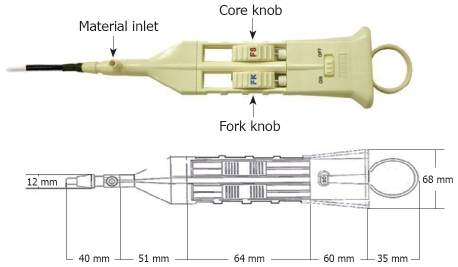

The Fork knife (Endo FS®) has two interchangeable knives, a fixed flexible snare and a forked knife, which form a single working unit, and has an inlet for material injection or saline irrigation during the procedure (Figures 1 and 2). The knives can be changed during a procedure by using two switches, the fork knob and core knob, located on the center of the body (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The Fork knife (Endo FS®).

Figure 2.

Working body of the Fork knife. Two switches, the fork knob and core knob, are located on the center of the body and enable the knives to be changed during the procedure. A material inlet for injection and irrigation is located forward of the body.

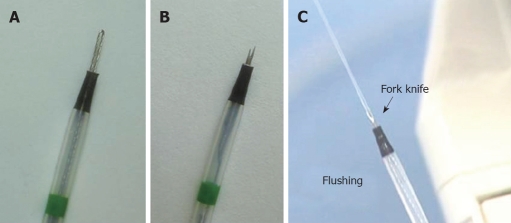

Fixed flexible snare: The first of the two knives that constitute the Fork knife is the fixed flexible snare (Figure 3A), which is operated by sliding the core knob switch forward. The blade is shaped into an elongated loop much like the Flexknife. We mainly use the fixed flexible snare for marking and making incisions around lesions. Marking around a lesion can be done using the tip of the fixed flexible snare. Additionally, the tip can be used for the incision and dissection of a lesion. Although the incision and dissection techniques are similar to those used with a Flexknife, the fixed flexible snare has the advantage of a fixed exposed body length with the snare located inside the tube, which allows the snare to be used more firmly than a Flexknife during dissection. An endoscopist does not need to be concerned about controlling the length of the body to prevent perforation in the event of a sudden movement by the patient, such as belching or coughing. The length of the blade, which can be adjusted using the switch on the center of the body, is usually set to 2.5 ± 1.0 mm in order to minimize the risk of perforation.

Figure 3.

Close-up views of the two inter-changeable knives of the Fork knife. A: Fixed flexible snare knife; B: Forked knife with a double-bladed tip; C: Saline irrigation can be performed using either knife.

Forked knife: The second knife is the forked knife, which has a double-tipped blade (longer tip length, 2 mm; shorter tip length, 1.5 mm) with a forked shape (Figure 3B). The forked knife is located on the opposite side from the fixed snare knife and is operated by sliding the fork knob switch forward. It is a form of a needle knife with an M-shape that maximizes the power applied to contacted surfaces, which is advantageous for dissection and coagulation. The longer tip of the forked knife can be used as an injection needle for making a submucosal cushion, or for injecting agents such as epinephrine. The opening of the needle is located in the center of the knife, between both tips, so that the mucosa must be injected deeply and at an oblique angle for maximum injection into the submucosa. We use the forked knife mainly for submucosal dissection performed in the proximal to distal direction of the endoscope, under direct visualization of the dissection area.

Multi-functions: The Fork knife has a built-in irrigation system via the material inlet, which allows saline irrigation while using either knife (Figure 3C). This allows the endoscopist to perform the dissection more comfortably and with prompt control of bleeding to maintain a clear endoscopic view. Additionally, by softly touching a vessel with the tip of knife and using the forced coagulation mode (40 W), an endoscopist can coagulate small vessels that may be exposed during a procedure. Thus, the use of the Forked knife permits better and faster control of any bleeding during a procedure, which reduces the time during which the endoscopic view is obscured.

Patients

From March 2004 to April 2008, we performed 715 ESDs on gastric lesions. We enrolled 337 patients with gastric lesions who underwent ESD from January 2006 to April 2008. One endoscopist, who performed ESD in over 400 cases, performed ESD on gastric lesions during the investigation period. ESD was performed using the Fork knife from January 2006 to October 2007, and the Flexknife was used from November 2007 to April 2008. We designed this study prospectively and reviewed retrospectively all of the enrolled ESD data. A total of 265 lesions were dissected with the Fork knife (group A), and 72 lesions were dissected with the Flexknife (group B). This study was approved by the institutional review boards of our hospital.

Methods

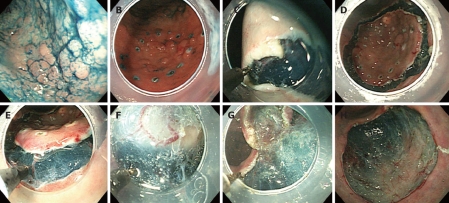

Patients were sedated with intravenous diazepam (20-40 mg) while in the endoscopic suite, and conscious sedation was maintained with additional injections during the procedure. All patients had a performance status of < 2 on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale and fulfilled the following expanded ESD indication established by the Japanese Gastroenterologic Endoscopic Society: (1) non-ulcerated, differentiated-type mucosal carcinoma, regardless of tumor size; and (2) differentiated-type mucosal carcinoma with an ulcer scar < 30 mm[15]. The Fork knife was used for all ESD steps in group A, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

ESD using the Fork knife. A: Indigo carmine spray for deciding the tumor border; B: Circumferential marking by the fixed flexible snare tip with soft coagulation current; C: Making an incision with a fixed flexible snare in ENDOCUT mode; D: Circumferential mucosal incision at the periphery of the marking dots; E: Dissecting the submucosal layer with a forked knife; F: Additional submucosal injection using the long tip of the forked knife without changing accessories; G: Dissecting the submucosal layer with a fixed flexible snare; H: Large ESD defect after complete en bloc resection.

Marking: After spraying of indigo carmine dye (Figure 4A), using the fixed flexible snare tip of the Fork knife, circumferential markings were made at 5 mm around the outline of the lesion, with 2-mm intervals between each marking dot, using a soft coagulation current of 40-50 W (ICC 200EA, ERBE Elektromedizin GmbH, Tübingen, Germany) (Figure 4B). For marking the lesion, the length of the fixed snare tip of the knife was set to approximate 1 mm, and then using the tip, the mucosa was touched lightly with electricity for 1 s.

Injection: Using the long tip of the forked knife, 2-5 mL of a saline/epinephrine solution was injected into the submucosa until the mucosa was raised. Additional injections were repeated as necessary during the procedure, without changing accessories.

Mucosal incision: After the lesion was lifted, the knife was subsequently changed to the fixed flexible snare for incision around the lesion. The fixed flexible snare was used to make the incision along the markings, using an electrosurgical generator in ENDOCUT mode, effect 3 (output, 80 W) (Figure 4C and D). The tip of the knife was set to approximate 2 mm. Precutting was not needed.

Dissection: Followed by incision around the lesion with the fixed flexible snare, dissection was done with either the forked knife or the fixed-flexible snare, with an electrical current of 40-50 W for swift coagulation (Figure 4F-H).

Bleeding: If bleeding occurs during dissection, saline can be irrigated without delay using either blades of the knife. Usually for small vessels that are smaller than or similar to the tip of the knives, the fixed flexible snare or the forked knife is sufficient to coagulate the vessels, with an electrical current of 40 W for forced coagulation. This allows the endoscopist to prompt control of bleeding (Figure 4E). Instead of a Fork knife, a Flexknife was used for ESD in group B, according to the same steps as described for group A.

Measurements

We compared the endoscopic appearance of tumors, location of tumors, en bloc resection rate, complete resection rate, size of resected specimens, complications, pathological findings, and procedure time between the two groups. The resected specimens were divided into two categories, en bloc and piecemeal. Complete resection was identified when the lateral and vertical margins of the specimen were free from tumor involvement. The resected specimens were classified into three size categories based on the longest diameter (< 3 cm, 3 to < 5 cm, and ≥ 5 cm), and the proportion of each category was compared between the two groups. To observe the complications of bleeding and perforation, blood samples, radiological examinations, and follow-up endoscopy were performed 1 and 2 d after ESD. Control of bleeding, difficult dissection caused by fibrosis, and lesion size were the major factors that affected the procedure time. Bleeding was identified when a hemostatic treatment such as endoscopic clipping and/or electrocoagulation was required during or after the procedure. Perforation was identified by endoscopy just after the resection and/or by the presence of free air on plain abdominal radiography. Fibrosis was identified as fibrotic tissue observable during dissection; the fibrosis rate was compared with the procedure time. The procedure time was measured as the time between the marking of the first dot and the withdrawal of the endoscope. The mean procedure time was compared between the two groups.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (version 12.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The data are presented as the mean ± SD or the median and range. Categorical parameters were compared using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were compared with Student’s t-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The mean age of group A was 62.4 ± 9.5 years and 63.3 ± 9.3 years in group B (Table 1). Gender ratios were similar between groups A and B. The number of differentiated adenocarcinomas was similarly high in both groups (36.2% in group A, 33.3% in group B), and the pathological distribution and mean size of the resected specimens were similar between the groups. Undifferentiated, signet ring cell cancer was confirmed based on resected specimens after ESD, instead of by initial biopsy before ESD. The mean longest diameter of the resected specimens was 4.27 ± 1.26 cm in group A and 4.29 ± 1.48 cm in group B.

Table 1.

Baseline and tumor characteristics of the patients in each group

| Characteristic | Group A (n = 265) | Group B (n = 72) |

| Gender (M/F) (%) | 189 (71.3)/76 (28.7) | 51 (70.8)/21 (29.2) |

| Mean age (yr) | 62.4 ± 9.5 | 63.3 ± 9.3 |

| Size of specimen (cm) | 4.27 ± 1.26 | 4.29 ± 1.48 |

| Pathologic report, n (%) | ||

| TALG | 51 (19.2) | 10 (13.9) |

| TAHG/CIS | 30 (11.3) | 9 (12.5) |

| Adenocarcinoma WD | 96 (36.2) | 24 (33.3) |

| Adenocarcinoma MD | 64 (24.2) | 19 (26.4) |

| Adenocarcinoma PD | 15 (5.7) | 7 (9.7) |

| Signet ring cell type | 8 (3.0) | 3 (4.2) |

| Other tumor1 | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

TALG: Tubular adenoma lower-grade dysplasia; TAHG: Tubular adenoma high-grade dysplasia; CIS: Carcinoma in situ; WD: Well-differentiated; MD: Moderately differentiated; PD: Poorly differentiated.

Carcinoid tumor.

Table 2 summarizes the depth, location, and endoscopic appearance of the tumors in the two groups. The table excludes adenomatous lesions and is limited to only those lesions confirmed to be cancerous by pathological reports. The tumor depth distribution was similar between the two groups (83.3% of mucosal layer cancer in group A, 81.1% in group B), although group B showed a higher portion of submucosal cancers. The endoscopic appearance showed a similar pattern of distribution between the two groups. The occurrence of depressed lesions was higher in group B than in group A (35.8% vs 28.1%), and the occurrence of mixed lesions was lower in group B than in group A (17.1% vs 27.1%). With regard to tumor location, group A showed a higher proportion of antral area cancers (54.8%) than group B (39.6%), but the locations were not significantly different between the two groups.

Table 2.

Clinical aspects of gastric cancer in the two groups n (%)

| Clinical aspect | Group A (n = 210) | Group B (n = 53) |

| Tumor depth | ||

| Mucosal layer | 175 (83.3) | 43 (81.1) |

| Submucosal layer | 35 (16.7) | 10 (18.9) |

| Endoscopic appearance | ||

| Protruded/Elevated | 77 (36.7) | 21 (39.6) |

| Flat | 17 (8.1) | 4 (7.5) |

| Depressed | 59 (28.1) | 19 (35.8) |

| Mixed | 57 (27.1) | 9 (17.1) |

| Tumor location | ||

| Cardia, Fundus | 11 (5.2) | 4 (7.5) |

| Body | 54 (25.7) | 15 (28.3) |

| Angle | 29 (13.8) | 12 (22.6) |

| Antrum, Pylorus | 115 (54.8) | 21 (39.6) |

| Subtotal gastrectomy state | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.9) |

The mean procedure time was significantly shorter in group A (59.63 ± 56.12 min), compared with group B (76.65 ± 70.75 min, P < 0.05) (Table 3). Other features such as fibrosis and resected specimen size, which play important roles in determining the procedure time, were similar between the groups. However, ulcerous lesions were significantly more common in group A than in group B (13.6% vs 6.9%, P < 0.05). Size of specimens was similarly distributed between the two groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of procedure time and lesions in the two groups n (%)

| Group A (n = 265) | Group B (n = 72) | P | |

| Procedure time (min) | 59.63 ± 56.12 | 76.65 ± 70.75 | 0.043 |

| Fibrosis | NS | ||

| Yes | 42 (15.8) | 11 (15.3) | |

| No | 223 (84.2) | 61 (84.7) | |

| Specimen size | NS | ||

| < 3 cm | 26 (9.8) | 7 (9.7) | |

| 3 to < 5 cm | 177 (66.8) | 42 (65.3) | |

| ≥ 5 cm | 62 (23.4) | 18 (25) | |

| Ulcer lesion | 0.041 | ||

| Yes | 36 (13.6) | 5 (6.9) | |

| No | 229 (86.4) | 67 (93.1) |

NS: Not significant.

The en bloc resection rate tended to be higher in group A (254, or 95.8% of cases) than in group B (67, or 93.1% of cases) (Table 4). The overall complication rate was 6.4% in group A and 2.8% in group B. Bleeding was more common in group A, but not significantly so. Perforation was observed in three cases in both group, and all cases were treated by conservative management with endoscopic clipping and fasting.

Table 4.

Resection type and complication rates in the two groups n (%)

| Group A (n = 265) | Group B (n = 72) | |

| Resection | ||

| En bloc | 254 (95.8) | 67 (93.1) |

| Piecemeal | 11 (4.2) | 5 (6.9) |

| Complication | ||

| None | 250 (94.3) | 70 (97.2) |

| Bleeding | 13 (4.9) | 1 (1.4) |

| Perforation | 2 (0.8) | 1 (1.4) |

The en bloc resection rates were high for specimens of all size categories and were not statistically different between the two groups. En bloc resection was performed for 92.3% of lesions < 3 cm, 97.7% of lesions 3 to < 5 cm, and 91.9% of lesions ≥ 5 cm in group A. In group B, en bloc resection was performed for 85.7% of lesions < 3 cm, 95.7% of lesions 3 to < 5 cm, and 88.9% of lesions ≥ 5 cm. The rate for complete ESD was higher in group A than in group B (Table 5), but the difference was not significant. Overall, four cases could not be evaluated regarding the invasion of cancer in the resected margins because of cellular autolysis and coagulation artifacts.

Table 5.

Comparison of ESD in the two groups n (%)

| ESD | Group A (n = 265) | Group B (n = 72) |

| Complete | 215 (81.1) | 53 (73.6) |

| Incomplete | 47 (17.7) | 18 (25) |

| Could not be evaluated | 3 (1.1) | 1 (1.4) |

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to introduce and evaluate the efficacy and technical aspects of ESD using a novel device, the multi-functional, convenient Fork knife.

ESD is an innovative technique that improves the rate of successful en bloc resection at an early stage of GI neoplasia[1-4]. Since Hirao et al[16] first introduced the ESD technique in 1988, many investigators have improved the technique and designed several devices, such as the needle-knife[16], insulated-tip (IT) knife[5-8], and Flexknife[9], that allow en bloc resection of widespread tumors. ESD and EMR techniques were developed mainly in Japan[16-18]. However, these techniques have now become major therapeutic modalities in Korea[19], which has a high incidence of early gastric cancer similar to that in Japan, for the treatment of early gastric cancer associated with minimal risk for lymph node metastasis[20,21]. Performing ESD is technically difficult and carries a high risk for complications such as perforation and bleeding[22-25]. The IT knife, which is commonly used for ESD, has been reported to have complication rates of 5%-22%[7,8,26]. There are no standard methods for preventing complications, and no rules exist for selecting proper devices during ESD. The proper devices for safe ESD are determined by the preference of the endoscopist and the circumstances of the dissection. Currently, ESD requires that the accessories be frequently changed through the working channel of the endoscope, according to the procedure being performed[12,13]. Using a two-channel endoscope is more convenient because two accessories can be loaded into the endoscope at the same time[14]. However, the thicker endoscopic diameter causes additional discomfort to the patient and increases the bend angle of the endoscope. The obtuse bend angle of the scope increases the difficulty of each step of ESD and complicates the response to specific conditions such as bleeding.

The Fork knife is a new device developed for ESD. It consists of two knives, a fixed flexible snare knife and a forked knife, in a single working unit. These two knives can be interchanged easily and with minimal time during the procedure. The Fork knife has the advantage of being multi-functional, such as marking, injection, incision, irrigation, dissection, and bleeding control. The fixed flexible snare tip can be used for marking and performing incisions in the early steps of ESD, and the forked knife can be used for injections and for dissection of the submucosal layer. Both knives can also perform simple irrigation and coagulation of point bleeding from exposed vessels, without changing accessories during the procedure. This enables the endoscopist to perform ESD more conveniently and easily and thus potentially shortens the total procedure time.

The devices needed during ESD vary according to the technique used, such as a one-knife or multi-knife method. There is no principle that ESD should be performed with only one device (one-knife method). It depends on the preference of the endoscopist who performs ESD or on the technical difficulty of the target lesion. We prefer a multi-knife method and believe that it allows safer and easier ESD procedures. Also, the Fork knife enables endoscopists to perform ESD without changing accessories during the whole procedure time.

The knife tip of the Fork knife and the Flexknife are similar to that of a needle knife, and afford easier horizontal than vertical dissection. Nevertheless, a skilled endoscopist can dissect a lesion without considering the direction of the knife relative to the plane of the wall.

In the present study, most of the conditions such as tumor location, endoscopic appearance, resected specimen size, and fibrosis that can affect procedure time were similar between the two groups. However, ulcerations were significantly more common in group A than in group B. The rates of complete ESD, en bloc resection, and bleeding were higher in group A, but the difference was not significant. The bleeding rate in group A was 4.9%, whereas bleeding rates of 0.7% and 22% have been reported for the Flexknife[9] and IT knife[8]. The definition of bleeding in our study, i.e., all hemostatic processes that occurred during the procedure, was broader than that in the Flexknife study[9], which may account, at least in part, for the difference in the reported rates. Despite the tendency toward more frequent bleeding complications in group A, the procedure time was significantly shorter in the Fork knife than in the Flexknife group. The shorter procedure time cannot be attributed to differences in the distributions of resected specimen size, tumor location, or endoscopic appearance, as all of these factors were similar between the two groups. It is likely that the shorter procedure time in group A resulted from the faster control of bleeding with the Fork knife compared with the Flexknife.

This study was limited by the different numbers of enrolled patients in each group; group A had four times the number of subjects in group B. This may present concerns regarding statistical comparisons between the groups. Another matter to consider is that ESD using the Fork knife was performed by a single endoscopist, who developed the design. Therefore, the endoscopist may have taken exceptional care to avoid complications or to shorten the procedure time. Also, we did not take into consideration the technical improvement of the endoscopist that resulted from his accumulated experience. Nevertheless, it is our belief that the multi-functional Fork knife can potentially reduce the time required for ESD and make ESD a more acceptable procedure for experienced endoscopists. The aim of this study was not to compare resection techniques such as ESD with the Flexknife vs ESD with the Fork knife, but to report on our preliminary experience of using a multi-functional and convenient tool that may save time.

In conclusion, the Fork knife is a multi-functional instrument that can perform various therapeutic endoscopic procedures such as marking, injection, dissection, coagulation, and simple saline irrigation, without the need to change accessories during procedures. The major advantage of the Fork knife is that it allows endoscopists to perform ESD more easily. The Fork knife may be a very useful device for performing ESD.

COMMENTS

Background

Each step of ESD, such as lesion marking, injection, incision, and dissection, may require a different accessory or a knife, depending on the location and shape of the tumor. Therefore, when performing ESD, the accessories may need to be changed frequently through the working channel of the endoscope, prolonging the procedure and delaying the control of GI bleeding.

Research frontiers

Many investigators have improved the technique of ESD and have designed various knives that enable the endoscopist to perform ESD more easily, such as the IT knife, Hookknife, Flexknife, and triangle-tipped knife. These knives have contributed to the development of ESD techniques, and each has merits and demerits.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The authors introduced and evaluated the efficacy and technical aspects of ESD using a novel device, a convenient multi-functional Fork knife. The Fork knife consists of two knives in a single working unit: a fixed flexible snare knife and a forked knife. These two knives can be interchanged easily and have the advantage of being multifunctional; they can be used for marking, injecting, incising, irrigating, dissecting, and controlling bleeding. This enables the endoscopist to perform ESD more conveniently, thus shortening the procedure.

Applications

The Fork knife may be useful for ESD of gastric lesions, such as early gastric cancer and gastric adenoma. The feasibility and safety of the novel device is similar to that of other knives but it may actually be more convenient because of its design.

Terminology

The ESD technique was first introduced in 1988 in Japan. ESD is an innovative technique that improves the rate of successful en bloc resection of early-stage GI neoplasms.

Peer review

An interesting article on a timely topic, endoscopic submucosal resection of early gastric cancer. The authors compared two newer instruments and found no real difference between them. The paper is well written, the study well conceived, and I learned a lot about the new treatments of early gastric cancer.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Michael E Zenilman, MD, Clarence and Mary Dennis Professor and Chairman, Department of Surgery, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Box 40, 450 Clarkson Avenue, Brooklyn NY 11202, United States

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Watanabe K, Ogata S, Kawazoe S, Watanabe K, Koyama T, Kajiwara T, Shimoda Y, Takase Y, Irie K, Mizuguchi M, et al. Clinical outcomes of EMR for gastric tumors: historical pilot evaluation between endoscopic submucosal dissection and conventional mucosal resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:776–782. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yokoi C, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Oda I. Endoscopic submucosal dissection allows curative resection of locally recurrent early gastric cancer after prior endoscopic mucosal resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kakushima N, Yahagi N, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Nakamura M, Omata M. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for tumors of the esophagogastric junction. Endoscopy. 2006;38:170–174. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-921039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Nakamura M, Kakushima N, Kodashima S, Ono S, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto T, Yamamichi N, Tateishi A, et al. Successful outcomes of a novel endoscopic treatment for GI tumors: endoscopic submucosal dissection with a mixture of high-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid, glycerin, and sugar. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyamoto S, Muto M, Hamamoto Y, Boku N, Ohtsu A, Baba S, Yoshida M, Ohkuwa M, Hosokawa K, Tajiri H, et al. A new technique for endoscopic mucosal resection with an insulated-tip electrosurgical knife improves the completeness of resection of intramucosal gastric neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:576–581. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.122579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyazaki S, Gunji Y, Aoki T, Nakajima K, Nabeya Y, Hayashi H, Shimada H, Uesato M, Hirayama N, Karube T, et al. High en bloc resection rate achieved by endoscopic mucosal resection with IT knife for early gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:954–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Hosokawa K, Shimoda T, Yoshida S. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225–229. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohkuwa M, Hosokawa K, Boku N, Ohtu A, Tajiri H, Yoshida S. New endoscopic treatment for intramucosal gastric tumors using an insulated-tip diathermic knife. Endoscopy. 2001;33:221–226. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kodashima S, Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, Ichinose M, Omata M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasia: experience with the flex-knife. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2006;69:224–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oyama T, Tomori A, Hotta K, Morita S, Kominato K, Tanaka M, Miyata Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early esophageal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S67–S70. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00291-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotoda T. A large endoscopic resection by endoscopic submucosal dissection procedure for early gastric cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S71–S73. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00251-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shim CS. Endoscopic mucosal resection: an overview of the value of different techniques. Endoscopy. 2001;33:271–275. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monkewich GJ, Haber GB. Novel endoscopic therapies for gastrointestinal malignancies: endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic ablation. Med Clin North Am. 2005;89:159–186, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neuhaus H, Costamagna G, Deviere J, Fockens P, Ponchon T, Rosch T. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) of early neoplastic gastric lesions using a new double-channel endoscope (the "R-scope") Endoscopy. 2006;38:1016–1023. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929–942. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1954-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirao M, Masuda K, Asanuma T, Naka H, Noda K, Matsuura K, Yamaguchi O, Ueda N. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer and other tumors with local injection of hypertonic saline-epinephrine. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:264–269. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(88)71327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakajima T. Gastric cancer treatment guidelines in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s101200200000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uedo N, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Ishihara R, Higashino K, Takeuchi Y, Imanaka K, Yamada T, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Longterm outcomes after endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:88–92. doi: 10.1007/s10120-005-0357-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JJ, Lee JH, Jung HY, Lee GH, Cho JY, Ryu CB, Chun HJ, Park JJ, Lee WS, Kim HS, et al. EMR for early gastric cancer in Korea: a multicenter retrospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:693–700. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tajima Y, Nakanishi Y, Ochiai A, Tachimori Y, Kato H, Watanabe H, Yamaguchi H, Yoshimura K, Kusano M, Shimoda T. Histopathologic findings predicting lymph node metastasis and prognosis of patients with superficial esophageal carcinoma: analysis of 240 surgically resected tumors. Cancer. 2000;88:1285–1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, Kato Y. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219–225. doi: 10.1007/pl00011720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujishiro M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for stomach neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5108–5112. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i32.5108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onozato Y, Ishihara H, Iizuka H, Sohara N, Kakizaki S, Okamura S, Mori M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancers and large flat adenomas. Endoscopy. 2006;38:980–986. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imagawa A, Okada H, Kawahara Y, Takenaka R, Kato J, Kawamoto H, Fujiki S, Takata R, Yoshino T, Shiratori Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: results and degrees of technical difficulty as well as success. Endoscopy. 2006;38:987–990. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gotoda T, Friedland S, Hamanaka H, Soetikno R. A learning curve for advanced endoscopic resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:866–867. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeuchi Y, Uedo N, Iishi H, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto S, Yamada T, Higashino K, Ishihara R, Tatsuta M, Ishiguro S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection with insulated-tip knife for large mucosal early gastric cancer: a feasibility study (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.03.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]