Abstract

AIM: To investigate the frequency of gastroen-terological diseases in the etiology and the efficacy of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in the treatment of cardiac syndrome X (CSX) as a subform of non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP).

METHODS: We investigated 114 patients with CSX using symptom questionnaires. A subgroup of these patients were investigated regarding upper gastrointestinal disorders (GIs) and treated with PPI. Patients not willing to participate in investigation and treatment served as control group.

RESULTS: Thirty-six patients denied any residual symptoms and were not further evaluated. After informed consent in 27 of the remaining 78 patients, we determined the prevalence of disorders of the upper GI tract and quantified the effect of treatment with pantoprazole. We found a high prevalence of gastroenterological pathologies (26/27 patients, 97%) with gastritis, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and acid reflux as the most common associated disorders. If treated according to the study protocol, these patients showed a significant improvement in the symptom score. Patients treated by primary care physicians, not according to the study protocol had a minor response to treatment (n = 19, -43%), while patients not treated at all (n = 26) had no improvement of symptoms (-0%).

CONCLUSION: Disorders of the upper GI tract are a frequent origin of CSX in a German population and can be treated with pantoprazole if given for a longer period.

Keywords: Non-cardiac chest pain, Gastroesophageal reflux disease, Proton pump inhibitor, Cardiac syndrome X

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac syndrome X (CSX) is a specific subform of non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP), defined as recurrent episodes of substernal chest pain or discomfort (exercise-related or not) with pathologic electrocardiographic (ECG) changes, but without significant cardiac abnormalities[1]. As relatively specific symptom complex involving ECG abnormalities, it often leads to cardiac catheterization after non-invasive cardiac diagnostic procedures, including treadmill exercise. Several studies indicate that about 15%-20% of all invasive cardiac diagnostic procedures can not detect any significant coronary abnormalities, reliably ruling out cardiac origin of the symptoms, supporting the assumption that the prevalence of NCCP (including CSX) is approximately 25% in the general population[2]. Several studies have contributed in elucidation of the origin and possible therapeutic approaches of NCCP with partially quite heterogenous results[2]. However, there are very limited data for the subgroup of CSX patients.

Interestingly, many patients with NCCP are not forwarded to gastroenterologists for further diagnostic work-up after exclusion of cardiac origin for chest pain[3]. Thus, they remain with their symptoms, which may cause significant economic and psychological burden because of frequent work absenteeism, frequent consultation of healthcare providers and reduced quality of life[4]. NCCP represents an important determinant of resource utilization and health care costs[5]. A defined further diagnostic work-up and targeted therapy of NCCP, therefore, is not only useful for patients, but also for the society as a whole.

Previous studies have shown that NCCP originates mostly from GERD and other gastrointestinal diseases, including motility disorders, often combined with visceral hypersensitivity or abnormal cerebral processing of visceral stimuli[6]. Musculoskeletal diseases may be a minor origin of NCCP. Additionally, psychological abnormalities play an important role in causing or modulating NCCP[7]. Published mechanistic hypotheses involve the presence of an esophagocardiac reflex, leading to coronary spasms when the distal esophageal mucosa is exposed to hypochloric acid[8]. This mechanism is also called “linked angina” and would serve as an explanation for NCCP in patients with clear pathologic ECG signs despite normal coronary angiography, which has frequently been termed as CSX[9,10].

Treatment studies of general NCCP focus on proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and there are clear data that omeprazole, rabeprazole and lansoprazole are effective in symptom relieve of NCCP[10].

To investigate prevalence of disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract and treatment in CSX, we designed a study enrolling patients with abnormal treadmill exercise results, but angiographic exclusion of coronary abnormalities. Firstly, these patients were investigated thoroughly regarding gastrointestinal disorders (GIs). In a second step, they were included into a therapeutic trial with pantoprazole, initially intended as a randomized, double-blind study, to test the efficacy of the drug in this subgroup of NCCP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients at least 18 years of age with recurrent chest pain, a pathological treadmill exercise and a normal coronary angiogram fulfilled the inclusion criteria of the study. Patients were excluded from the study if they had medications lowering the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter (calcium antagonists, nitrates), were already on acid-suppressive drugs during cardiologic work-up (PPI or histamine blockers) or had clearly identifiable and established musculoskeletal pain in the thoracic spine or the chest. The study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee.

Patients

In the period between May, 2003 and November, 2004, all patients with chest pain, a pathological treadmill exercise and with a normal coronary angiogram were identified in the Cardiology Center of Aachen University, Germany. All patients were contacted by phone and, after testing the eligibility, were asked whether they still suffered from chest pain. Patients without any symptoms immediately after the angiography and without any specific medication were considered to have chest pain at least modulated by psychological diseases and were excluded from further questioning. Patients with ongoing chest pain, but treated with PPI after the normal angiography by their primary care physicians (PPI test approach[10]), were included into an external PPI group. Patients with ongoing chest pain and no specific medication were asked to join the study.

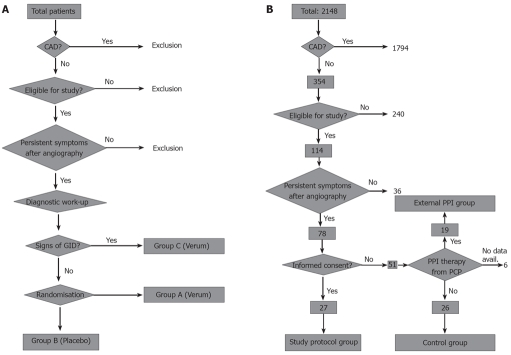

In total, 78 patients were eligible for the study, but only 72 agreed to participate in data collection. Twenty-seven patients gave written informed consent to participate in the PITFALL study protocol including diagnostic work up and therapy with pantoprazole. The initial study design is depicted in Figure 1A. The planned study randomization arms A and B were closed shortly after beginning of the study, due to low patient recruitment. Ninety seven percent (26/27) of the study patients had to be included into study arm C because of pathological findings during the diagnostic work-up. In order to establish an external control group, we included patients with ongoing chest pain who were not willing to participate in the diagnostic and therapeutic study in another group. These patients and the patients in the external PPI group received questionnaires regarding symptoms and treatment at study entry and 8 wk after study entry. The adapted study design is shown in Figure 1B. Characteristics of study patients from each group are given in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Study design. A: Original study design with 3 patient groups. Randomization was planned after the diagnostic procedures in order to randomize only patients without overt signs of gastrointestinal disease. After recruitment of the first 10 patients only for patient group C, the other two patient groups were closed and the study design was adapted as depicted in B (CAD: Coronary artery disease; GID: Gastrointestinal disease); B: Adapted study design without randomization. To compare the results of per protocol treatment to patients treated in a non-standardized fashion or untreated patients, an external PPI group and a control group were built by recruiting patients who were treated by their primary care physicians (external PPI group, 19 patients) or were not willing to undergo treatment at all (control group, 26 patients). These patients were not matched to the study protocol group and most of them did not receive diagnostic procedure regarding gastrointestinal diseases (CAD: Coronary artery disease; PCP: Primary care physician).

Table 1.

Mean age and proportion of female patients in all patient groups

| Patient group | Age (yr, mean ± SD) | Female gender (%) |

| Study protocol group | 59 ± 10 | 56 |

| External PPI group | 63 ± 8 | 63 |

| Control group | 62 ± 9 | 73 |

Quantitation of symptoms

All patients (study group, both external groups) ranked the symptoms using a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 0 to 10 each for intensity, duration and frequency of chest pain. Characteristics of each scale are given in Table 2. The three parameters were added (maximum score: 30 points) and used as symptom score (VAS total score). These four different VAS scores were evaluated before and after therapy (in the external placebo group in a time difference of 8 wk). Patients in both external groups were also asked regarding their co-medication during the 8-wk period.

Table 2.

Definitions of ranks in visual analogue scale (characteristics of symptoms)

| Grade | Frequency | Duration | Intensity |

| 10 | Permanent | Permanent | |

| 9 | Several times daily | Almost whole day | |

| 8 | Daily | More than 6 h | |

| 7 | Almost daily | More than 2 h | |

| 6 | Several times weekly | About 1 h | Grading by patients on a scale from 0 to 10 |

| 5 | Up to 3 times weekly | 10-30 min | |

| 4 | Once weekly | 5-10 min | |

| 3 | Several times in 1 mo | 1-5 min | |

| 2 | Up to 3 times in 1 mo | Less than 1 min | |

| 1 | Once per month | A few seconds | |

| 0 | Never or very seldom | Never |

Patients were asked for symptoms and were helped to grade the frequency, duration and intensity using the characteristics below.

Diagnostic work-up

All patients in the study group received gastroscopy, 24-h esophageal pH-monitoring and concurrent impedancometry and manometry (CIM) in the gastroenterological endoscopy unit of Aachen University Medical Center. The latter procedure (CIM) was conducted using a custom-made catheter consisting of 11 impedance segments (each 2 cm long) and 4 semiconductor pressure transducers. The solid-state pressure transducers are located between the impedance channels 1-2, 4-5, 7-8 and 10-11 with an intertransducer distance of 6 cm. The configuration of the catheter allows a simultaneous registration of bolus transport and esophageal peristalsis (details in reference by Nguyen et al[11]). The catheter was passed through the nose into the esophagus with the most distal pressure sensor placed at the level of the lower esophageal sphincter.

If the diagnosis of acid-related disorders such as gastritis, ulcer disease or GERD was established, the patients were enrolled into study arm C. This led to closure of study arms A and B as described above.

Diagnostic findings from patients in the external groups were not used for study purposes.

Therapeutic study protocol

Patients in study arm C received pantoprazole 40 mg bid for 8 wk. After this period, treatment strategy was open and depending on symptoms. If tested positive for H pylori, eradication treatment was initiated. Intolerance of pantoprazole led to prescription of omeprazole 20 mg bid. After completion of the therapeutic study arm, patients gave information about their symptoms using the same VAS scores as described above and most patients underwent control investigations of gastroscopy and 24-h esophageal pH-monitoring.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were summarized as absolute and corresponding relative frequencies. Observed VAS scores were condensed by minimum, maximum, median and corresponding interquartile range, separately for the two different time points (before therapy, after therapy) in each of the three study groups. Parallel boxplots were used for graphical comparison of the obtained VAS scores between the time points before and after therapy within each study group.

In each group, paired Wilcoxon tests were conducted for comparison of the different VAS scores before and after therapy. A global significance level of α = 5% was chosen. Only the results (P-values) of the tests carried out with respect to the VAS total scores were interpreted in a confirmatory fashion, while results for the scores of intensity, duration and frequency were meant solely exploratively. Thus, P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical analysis software package R (http://www.R-project.org).

RESULTS

Large subgroup of patients without symptoms after angiography

Only patients with normal coronary angiography performed for chest pain, with abnormal treadmill exercise and without any further diagnostic procedures or therapy after angiography were included into the study. In telephone interviews, 114 eligible patients were asked for persisting symptoms following the diagnostic procedure. Thirty-six (31%) of the 114 interviewed patients without further therapy denied any residual symptoms. It is likely that a substantial subset of these patients had chest pain due to psychosomatic reasons. These patients were excluded from further investigations of this study.

Further stratification of study population

Only 27 of the 78 patients meeting the inclusion criteria of the study group agreed to join the diagnostic and therapeutic study according to the PITFALL study protocol. Of the remaining 51 patients, 19 discussed the possibility of gastrointestinal diseases with their primary care physicians and received diagnostic work-up and therapy from them, mostly in the form of a PPI test. They agreed to give information about their symptoms during and after the primary care physician-guided therapy. The gained information was included in the study and the patients were grouped as “external PPI group”. The prescribed therapy did not follow the study protocol in most cases regarding dose and length of treatment (data not shown) and involved prescription of several different proton-pump inhibitors, as well as different length and follow-up of therapy.

Twenty-six of 51 patients denied any diagnostic procedure and therapy and explained that they were not interested in any further work-up of persisting symptoms. These patients, however, agreed to give information about their symptoms in certain intervals and were grouped as “external control group”; the gained information (i.e. different VAS scores at different time points) of these patients was included into statistical evaluation of the study as well. Age and gender distribution of all patient groups are given in Table 1.

Six of 51 patients refused any cooperation or data collection and were excluded from further questioning.

Prevalence of GIs in NCCP patients

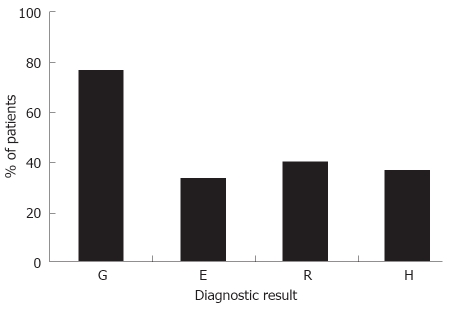

Fifty-seven percent of the study patients had signs of acid reflux consistent with GERD (De Meester Score > 14, pH time < 4 more than 5% and/or gastroscopic evidence of esophagitis). Relevant gastritis with or without erosive changes of the mucosa was present in 78% of the patients (histologically proven), from which 27% had no signs of GERD. H pylori was detected in 11% and eradicated using the French triple therapy with amoxicillin and clarithromycin. In total, 97% (26/27) patients showed a relevant acid-related disorder (GERD or histologically proven gastritis) of the upper gastrointestinal tract (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of study protocol patients with gastritis (G, partially erosive or ulcerative), esophagitis (E), reflux as diagnosed by pH monitoring (R) and/or hiatal hernia (H). Multiple diagnoses in a patient were possible so that the total percentage is above 100.

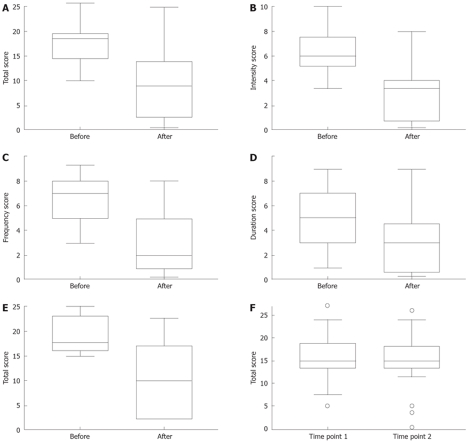

Symptomatic improvement in the study protocol group

Results of the total symptom score before and after PPI therapy are given in Figure 3A. The study patients experienced a statistically significant improvement in symptoms after 8 wk of PPI therapy in doubled standard dose (P < 0.0001). If analyzed in an explorative fashion for all subscores, this improvement turned out to be valid for all three quantities (intensity, frequency and duration of symptoms, Figure 3B-D, P < 0.001 for all quantities).

Figure 3.

Results of the different group by graphical representation (parallel boxplot). A: Total score; B: Intensity score; C: Frequency score; D: Duration score. The three symptom scores (B-D) are before and after treatment with pantoprazole in the study protocol group. There was statistically significant difference between the scores before and after therapy (P < 0.001 for all four scores). E: Graphical representation (parallel boxplot) of the total score before and after treatment in the external PPI group. The total score after treatment was significantly different compared to the total score before treatment (P = 0.0011); F: Graphical representation (parallel boxplot) of the total score before and after an observation period of 8 wk in the control group. There was no significant difference between the scores before and after the observation period (P = 0.2448).

Symptomatic improvement in the external PPI group

Similar to the study group, patients in the external PPI group reported statistically significant improvement in symptoms after a variable PPI therapy (P = 0.0011).

The improvement was not as large as in the study group (Figure 3E). Explorative analysis of the subscores showed a benefit for all three symptom quantities (similar to the study group, data not shown).

No symptomatic improvement in the external control group

In contrast to the first two groups, we observed no improvement of the total VAS score for the patients in the external control group. Scores at start and 8 wk later without any specific treatment were not statistically significant different (P = 0.2448, Figure 3F).

Identification of specific risk factors for gastrointestinal causes of NCCP or treatment success

In the original study protocol, a multivariate analysis was planned to identify specific risk factors for stratifying NCCP patients with gastrointestinal causes. Furthermore, we wanted to identify specific parameters to predict the extent of treatment success in the study group. Due to the changed study design and the low patient volume in all groups, especially in the study protocol therapy group, we did not conduct such data analysis.

DISCUSSION

Patients with a special subgroup of NCCP, the so-called CSX, were investigated in the present study. This syndrome is defined as recurrent chest pain with pathological electrocardiography, but normal coronary angiography. Given the results of pathophysiological studies and the common efferent and afferent nerve supply of the upper gastrointestinal tract and the heart[8,9], our results confirm that symptoms of CSX patients are almost invariably caused by acid-related disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract. The described symptoms consequently could be treated very well using the doubled standard dose of pantoprazole.

Interestingly, there is a large group of patients with CSX, which presents with much improved or absent symptoms after coronary angiography. This seems to indicate that many patients probably exhibit stress-induced symptoms of psychosomatic character. Recent studies show a prevalence of psychological abnormalities between 17% and 43% in NCCP patients[7], which is in line with our results (31%) in patients with CSX. Additionally, stress can provoke gastrointestinal acid-related disorders as well. However, many patients with psychosomatic origin of NCCP still have persistent symptoms after cardiac diagnostic procedures and they often do not respond to PPI therapy. In our study protocol group, 2/27 patients (7%, but 30% in the external PPI group) showed no or only little benefit of PPI therapy (defined as improvement < 10%), so that these patients may have psychosomatic disorders as well. Very recently, it was shown that hypnosis might contribute to symptom improvement in this patient group[12].

The referral rate of patients with chest pain, after exclusion of cardiac abnormalities, was low in our study. Only 8 of 78 (10%) patients were already in diagnostic work-up for or in treatment of GIs. This result is in agreement with previous studies indicating a low interest or strain in further diagnostic work-up after cardiologic examination[2]. Whether this low referral rate is due to the patients or their primary care physicians is not completely clear and deserves further studies. Nevertheless, this finding clearly demonstrates the need for a closer follow-up of NCCP patients in every day practice.

All but one patient in the treatment group had evidence of upper gastrointestinal tract disease of different degrees. The most important diagnostic tool in this setting was gastroscopy, followed by 24-h esophageal pH-monitoring. Interestingly, we could not find one relevant motility disorder using a highly sensitive method with measurement of impedance and motility in the esophagus (CIM). This indicates that motility disorders are rare in causing the investigated subform of NCCP/CSX. Though dysmotility has often been demonstrated in NCCP[13], its impact on chest pain is unclear. There is no specific treatment for dysmotility and PPI therapy has no influence on the motility disorder. Data observing an effect of PPI therapy on chest pain associated with motility disorders[14] showed only a very minor effect on the respective motility disorder itself. These data indicate that dysmotility only is a facet or associated symptom of NCCP, not the main origin[15].

Interestingly, a large subgroup of patients presented with different degrees of histologically proven gastritis. These patients did not complain about epigastric pain, but exhibited chest pain. GERD has been the central investigated acid-related disorder in causing NCCP[6]. Gastritis may play a more important role in the etiology of CSX or has been underestimated up till now for causing NCCP. It is also possible that gastritis is, in our study, simply an expression for esophageal acid reflux, which could not be detected by 24-h esophageal pH-monitoring. It has been shown that extending the recording time of pH measurement to 48 h increases the sensitivity of the procedure[16]. Further studies with larger patient groups and improved pH measurement are necessary to solve this issue.

Treatment with pantoprazole, in the treatment group, led to a significant improvement in the symptom score. This supports our assumption that the symptoms were caused by the diagnosed GIs including gastritis, and indicates the value of the tested substance in treating NCCP patients. Seven of 27 patients were completely asymptomatic after 8 wk of treatment with pantoprazole and 54% of the patients showed an improvement of at least 50% in the symptom score. In the external PPI group, the improvement of symptoms was lower, mostly owing to shorter treatment periods and lower dosages of PPI. This clearly indicates that treatment of gastrointestinal NCCP causes requires a clear protocol with initial high doses (double the standard dose per day) and long treatment periods. Several recent studies, especially those using a “test therapy approach”, treated for only 7 d which may have led to underestimation of the PPI benefit[10]. In the external control group, we observed no improvement in the symptom score. This is in line with our expectations and underlines, though we were not able to randomize these patients, the treatment effect of pantoprazole in our study group.

Unfortunately, we were not able to identify any significant predictor (other than the diagnosis of an acid-related disorder) for treatment response in our patient group. Additionally, our sample size was too small to identify predictors for NCCP before cardiac catheterization in order to reduce normal coronary angiographic results and induce a PPI test treatment in such patients which may benefit from this approach. It has been shown in the past that the “PPI-test” is cost-effective in terms of avoiding the traditional invasive gastroenterological diagnostic strategy[17]. However, we consider an approach to identify patients with NCCP before they receive invasive cardiological diagnostic procedures much more important, because these diagnostic procedures are more expensive and more prone to side effects than gastroscopy and 24-h esophageal pH-monitoring.

In conclusion, we have shown that in patients with CSX, acid-related disorders are frequent and respond very well to a long-term therapy with pantoprazole. Motility disorders obviously are extremely rare, as shown by a very sensitive diagnostic tool (CIM) in our study. The rate of gastroenterological referral after exclusion of cardiac abnormalities is still too low. It is useful to conduct additional studies with more patients, which should lead to criteria to identify patients having a benefit from a PPI therapy before coronary angiography is done.

COMMENTS

Background

Non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP) and its subform cardiac syndrome X (CSX) have a high incidence in Western countries and represent a significant health burden.

Research frontiers

In this study, authors investigated, for the first time, the pathogenesis and possible treatment of the specific NCCP subform CSX in a German population.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The authors established that gastrointestinal disorder (GI)-tract-associated disorders in a high percentage are responsible for CSX and that the symptoms can be treated by proton pump inhibitor (PPI).

Applications

The results of this study are important for primary care physicians, cardiologists and gastroenterologists in the medical care of chest pain patients.

Terminology

NCCP denotes angina-like typical chest pain which could not be linked to the heart by specific investigations (including angiography). CSX is a subform of NCCP and means that these patients showed typical electrocardiographic (ECG) abnormalities despite a normal angiogram.

Peer review

This is an interesting paper. It investigated the frequency of gastroenterological diseases in the etiology and the efficacy of PPIs in the treatment of CSX as a subform of NCCP. It provided useful information to the readers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rüdiger Hoffmann and Karin Lung, Department of Cardiology at Aachen University, for valuable assistance and help in identifying potential study patients. We also thank Wolfgang Fischbach for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful comments.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Bernardino Rampone, PhD, Department of General Surgery and Surgical Oncology, University of Siena, viale Bracci, Siena 53100, Italy

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Kumar M E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Kachintorn U. How do we define non-cardiac chest pain? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20 Suppl:S2–S5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fass R, Dickman R. Non-cardiac chest pain: an update. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:408–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong WM, Beeler J, Risner-Adler S, Habib S, Bautista J, Fass R. Attitudes and referral patterns of primary care physicians when evaluating subjects with noncardiac chest pain--a national survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:656–661. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eslick GD, Talley NJ. Non-cardiac chest pain: predictors of health care seeking, the types of health care professional consulted, work absenteeism and interruption of daily activities. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:909–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eslick GD. Noncardiac chest pain: epidemiology, natural history, health care seeking, and quality of life. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2004;33:1–23. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8553(03)00125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Handel D, Fass R. The pathophysiology of non-cardiac chest pain. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20 Suppl:S6–S13. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aziz Q. Acid sensors in the gut: a taste of things to come. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:885–888. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200108000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chauhan A, Petch MC, Schofield PM. Cardio-oesophageal reflex in humans as a mechanism for "linked angina". Eur Heart J. 1996;17:407–413. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaski JC. Pathophysiology and management of patients with chest pain and normal coronary arteriograms (cardiac syndrome X) Circulation. 2004;109:568–572. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116601.58103.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong WM. Use of proton pump inhibitor as a diagnostic test in NCCP. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20 Suppl:S14–S17. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen HN, Silny J, Matern S. Multiple intraluminal electrical impedancometry for recording of upper gastrointestinal motility: current results and further implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:306–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones H, Cooper P, Miller V, Brooks N, Whorwell PJ. Treatment of non-cardiac chest pain: a controlled trial of hypnotherapy. Gut. 2006;55:1403–1408. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.086694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dekel R, Pearson T, Wendel C, De Garmo P, Fennerty MB, Fass R. Assessment of oesophageal motor function in patients with dysphagia or chest pain - the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:1083–1089. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Achem SR, Kolts BE, Wears R, Burton L, Richter JE. Chest pain associated with nutcracker esophagus: a preliminary study of the role of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiMarino AJ Jr, Allen ML, Lynn RB, Zamani S. Clinical value of esophageal motility testing. Dig Dis. 1998;16:198–204. doi: 10.1159/000016867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prakash C, Clouse RE. Value of extended recording time with wireless pH monitoring in evaluating gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:329–334. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fass R, Fennerty MB, Ofman JJ, Gralnek IM, Johnson C, Camargo E, Sampliner RE. The clinical and economic value of a short course of omeprazole in patients with noncardiac chest pain. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:42–49. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]