Abstract

Objective

Triptolide (TP) has been reported to suppress the expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphatase-1 (MKP-1), of which main function is to inactivate the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 (ERK-1/2), the p38 MAPK and the c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1/2 (JNK-1/2), and to exert antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activities. However, the mechanisms underlying antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activities of TP are not fully understood. The purpose of this study was to examine whether the down-regulation of MKP-1 expression by TP would account for antiproliferative activity of TP in immortalized HT22 hippocampal cells.

Methods

MKP-1 expression and MAPK phosphorylation were analyzed by Western blot. Cell proliferation was assessed by 3H-thymidine incorporation. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) against MKP-1, vanadate (a phosphatase inhibitor), U0126 (a specific inhibitor for ERK-1/2), SB203580 (a specific inhibitor for p38 MAPK), and SP600125 (a specific inhibitor for JNK-1/2) were employed to evaluate a possible mechanism of antiproliferative action of TP.

Results

At its non-cytotoxic dose, TP suppressed MKP-1 expression, reduced cell growth, and induced persistent ERK-1/2 activation. Similar growth inhibition and ERK-1/2 activation were observed when MKP-1 expression was blocked by MKP-1 siRNA and its activity was inhibited by vanadate. The antiproliferative effects of TP, MKP-1 siRNA, and vanadate were significantly abolished by U0126, but not by SB203580 or SP600125.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that TP inhibits the growth of immortalized HT22 hippocampal cells via persistent ERK-1/2 activation by suppressing MKP-1 expression. Additionally, this study provides evidence supporting that MKP-1 may play an important role in regulation of neuronal cell growth.

Keywords: Triptolide, HT22 hippocampal cell, Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1, Extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2, Mitogen-activated protein kinase, Proliferation

INTRODUCTION

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, including the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 (ERK-1/2), the c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1/2 (JNK-1/2), and the p38 MAPK, is involved in the survival, proliferation and differentiation of neuronal cells18). Some of the MAPKs appropriately regulate cellular proliferation, and others promote the differentiation towards the neuron lineage15). The MAPKs are also involved in survival and apoptosis of neuronal cells2). The MAPK pathway is activated through a cascade of sequential phosphorylation events, and dephosphorylation of MAPKs mediated by phosphatases represents a highly efficient mode of kinase deactivation. A number of protein phosphatases are known to deactivate MAPKs, including tyrosine, serine/threonine, and dual-specificity phosphatases. In mammalian cells, the dual-specificity protein phosphatases, which are often referred to as MAPK phosphatases (MKPs), are the primary phosphatases responsible for dephosphorylation/deactivation of MAPKs19). To date, at least 10 MKPs have been identified in mammalian cells, with MKP-1 being the archetype1). Although MKP-1 was initially thought to be a phosphatase specific for the ERK-1/2, recent studies demonstrated that MKP-1 also efficiently inactivated JNK-1/2 and p38 MAPK1).

Triptolide (TP) is the active component of the Chinese herb Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F., which has been used for thousands of years as a therapeutic agent against various inflammatory diseases4). Recently, accumulating evidence demonstrates that besides its anti-inflammatory activity, TP also possesses antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activities in various tumors and immortalized cells11,16,27). However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic activities of TP are not fully understood.

TP has been screened originally as a potent inhibitor that can block the expression of MKP-1 and widely used for understanding the relationship between MKP-1 expression and MAPK inactivation5,13,24,28,29), which raises a question regarding whether the down-regulation of MKP-1 expression by TP would account for at least one of its biological activities. Because MKP-1 down-regulates MAPK activation that plays important roles in proliferation and apoptosis2,15), we have hypothesized that the down-regulation of MKP-1 expression by TP would account for its antiproliferative and/or pro-apoptotic activities in immortalized HT22 hippocampal cells. Here, we have demonstrated that TP at a non-cytotoxic dose potently inhibits the proliferation of HT22 cells through its inhibition of MKP-1 expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Dulbecco's-modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), TP, paclitaxel, 4', 6-diamidine-2-phenylindole (DAPI), Trypan blue solution, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), rhodanine 6G, a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay kit, and sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). U0126, SB203580 and SP600125 were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). The antibodies for anti-p38 MAPK, anti-phospho-p38 MAPK (P-p38), anti-ERK-1/2, anti-phospho-ERK-1/2 (P-ERK-1/2), anti-JNK-1/2, anti-phospho-JNK-1/2 (P-JNK-1/2), anti-MKP-1, anti-phospho-MKP-1 (P-MKP-1), and anti-β-actin, and the small interfering RNA (siRNA) against mouse MKP-1 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Antibody for horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-IgG antibody was obtained from Sigma Aldrich. The enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) solution was purchased from Lifesciences (Piscataway, NJ, USA). The mouse MKP-1 expression plasmid, pSG5-MKP-1 containing a single copy of the Myc epitope tag, was kindly provided by K. T. Kim (Pohang University of Science and Technology, Pohang, Korea). All other chemicals used were of the highest grade available commercially.

Cell culture and transfection

The hippocampal cell line (HT22 cells) used in this study is a sub-line cloned from the parent HT4 cells that were immortalized from primary mouse hippocampal neurons using a temperature-sensitive small virus-40 T antigen6). HT22 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 50 µg/mL gentamicin, 0.05 unit/mL penicillin, 50 µg/mL streptomycin, pH 7.4 at 37℃ in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. In a 6-well tissue culture plate, HT22 cells were seeded at a density of about 2 × 105 cells per well. When the density of cells reached 50-60%, cells were transfected with pSG5-MKP-1 or MKP-1 siRNA, using Lipofectamine™, reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. After incubation for 24 h, the transfected cells were treated as indicated for analysis.

Assessment of cell viability and apoptosis

Cell viability was determined by Trypan blue dye-exclusion assay. HT22 cells were collected at an indicated time and incubated with 0.4% Trypan blue, observed under a microscope, and the stained and unstained cells were then counted on a hemocytometer separately. Cell viability was calculated according to the following formula : cell viability (%) = (unstained cells number/total cells number) × 100. Cell death was calculated by the following formula : cell death (%) = (stained cells number/total cells number) × 100. To assess apoptosis, the nuclei of HT22 cells were stained with DAPI, as previously reported10). Cells were fixed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. After fixation, cells were washed twice with PBS and then stained with DAPI. After three washes, cells were observed under fluorescence microscope.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were treated with TP, scraped and collected in 1 × PBS and then centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 3 min. The pellets were then disrupted in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1 × Nonidet P-40, supplemented with protease inhibitor (Sigma Aldrich). The solubilized lysates were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min at 4℃ and supernatants were collected for further analysis. Equivalent amount of total protein (20-30 µg) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 10% polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to polyvinylidine membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% dry milk in PBS/0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (PBST) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4℃ in PBST. The membranes were then washed three times with PBST (10 min each time), incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 40 min at room temperature and followed by three time washes with PBST. Immunoreactive bands were then revealed by ECL solution, using standard X-ray film.

Assessment of proliferation

5 × 104 cells were cultured in 96-well plates for 12 h, then incubated for 12 h with indicated concentrations of TP or vanadate. The cultures then were pulsed with 0.5 µCi/well [3H]-thymidine (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) for 12 h, and harvested onto cellulose filters. The cellulose filters were placed in vials with 3 mL of scintillation liquid and read in a beta radiation counter (Beckman LS 6000SE, Fullerton, CA, USA). Results are expressed in percentages. The mean counts per minute obtained from the control cells were considered to be 100%.

Determination of LDH release

The release of LDH into the culture medium was regarded as an indicator of necrotic cellular damage and cytotoxicity. LDH is a stable cytoplasmic enzyme in all cells, and is rapidly released into the cell culture if the plasma membrane was damaged by oxidant, such as H2O2. An increase of LDH activity in the culture supernatant indicated an increase in the number of necrotic cell dead. Briefly, after immortalized HT22 cells were exposed to various concentrations of TP or 300 µM of H2O2 (as a positive control), the supernatant was collected for LDH determination in the cell-free medium. The cell pellet and the cells remaining on the well were lysed in 0.5 mL of lysis buffer (0.5% Triton X-100 in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5). The release of intracellular LDH to extracellular medium was measured by determining LDH activity and was expressed as the percentage of total LDH activity (total LDH activity = LDH activity in the cell-free medium + LDH activity in the cell medium). LDH released was calculated according to the following equation : LDH released (%) = (LDH activity in the cell-free medium/total LDH activity) × 100. LDH activity was measured with a commercial kit (Sigma Aldrich).

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as mean ± SE. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test was performed to compare the mean values between various groups. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

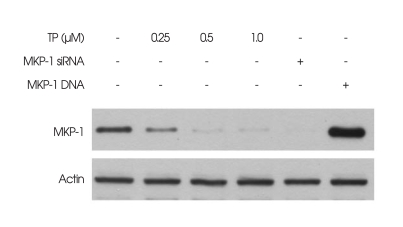

Given that TP was previously identified as an inhibitor for MKP-1 expression5,13,24,28,29), the effect of TP on MKP-1 expression in immortalized HT22 hippocampal cells was first analyzed by Western blot. As shown in Fig. 1, TP (0.5 µM) almost completely inhibited MKP-1 expression at 6 h, as compared with control cells not exposed to TP. The MKP-1 expression was confirmed by the positive and negative control cells transfected with MKP-1 siRNA (for blockage of MKP-1 cellular synthesis) or MKP-1 gene (for over-expression of MKP-1), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Effect of triptolide (TP) on the expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) in immortalized HT22 cells. Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of TP for 6 h. The cells that were transiently transfected with either MKP-1 small interfering RNA (MKP-1 siRNA; Lane 5) or MKP-1 gene (Lane 6) served as the controls for MKP-1 expression, and were cultured for 6 h. Expression of MKP-1 was examined by Western blot analysis with anti-MKP-1 antibody, as described in materials and methods. Representative Western blots of three independent experiments are shown.

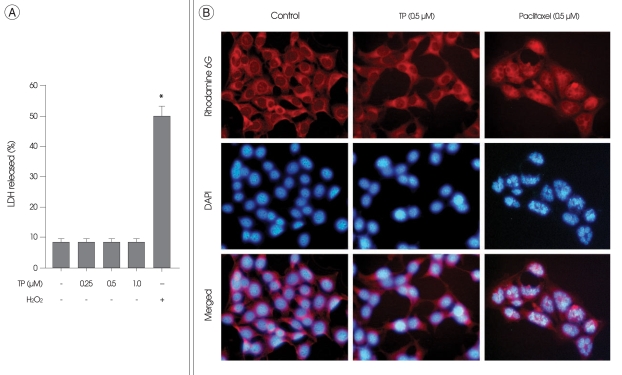

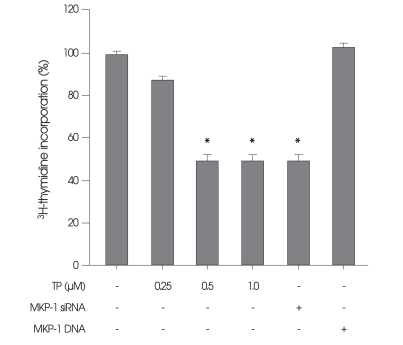

The effect of TP on the viability of HT22 cells was next examined after incubation in medium containing TP for 24 h. HT22 cells were incubated with H2O2, served as a positive control of necrosis, or with paclitaxel, an anti-cancer drug that is well known to inhibit cell growth through induction of apoptosis17), served as a positive control of apoptosis. There was no significant change in the viability and the nuclei of HT22 cells (Fig. 2), as compared with control cells not exposed to TP. In contrast, necrotic LDH release were observed in H2O2-treated cells (Fig. 2A). Condensed chromatin and fragmented nuclei were also found in paclitaxel-treated cells (Fig. 2B), which were classic characteristics of apoptotic cells. Although TP had no significant effect on the viability of HT22 cells for 24 h, this drug obviously inhibited cell growth even without cytotoxicity (Fig. 3). Interestingly, similar growth inhibition was also observed when the cells were transiently transfected with siRNA against MKP-1 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Effect of triptolide (TP) on necrosis and apoptosis of immortalized HT22 cells. A : Immortalized HT22 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of TP or 300 µM of H2O2 for 24 h. For the analysis of necrosis, the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the culture medium was determined by a LDH assay kit, as described in materials and methods. Values represent mean ± SE of four replicates in three different experiments. *p < 0.05 versus untreated control cells. B : Immortalized HT22 cells were treated with 0.5 µM of TP or 0.5 µM of paclitaxel (positive control) for 24 h. For the analysis of apoptosis, the nuclei of HT22 cells were stained with 4',6-diamidine-2-phenylindole, and observed under a fluorescent microscope. To visualize cell morphology, cytoplasm was stained with rhodamin 6G, a cell-permeable fluorescence dye. The fragmented nuclei that are characteristics of apoptotic cells are shown only in paclitaxel-treated cells.

Fig. 3.

Effect of triptolide (TP) on proliferation of immortalized HT22 cells. Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of TP for 24 h. The cells that were transiently transfected with either mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) small interfering RNA (MKP-1 siRNA; column 5) or MKP-1 gene (column 6) served as the controls for MKP-1-dependent proliferation, and were cultured for 24 h. Cell proliferation was determined by 3H-thymidine incorporation, as described in materials and methods. Values represent mean ± SE of four replicates in three different experiments. *p < 0.05 versus untreated control cells.

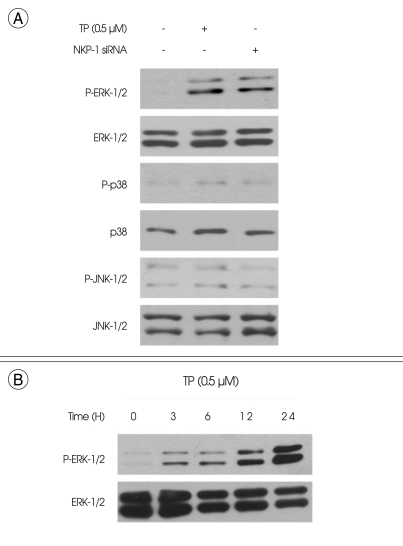

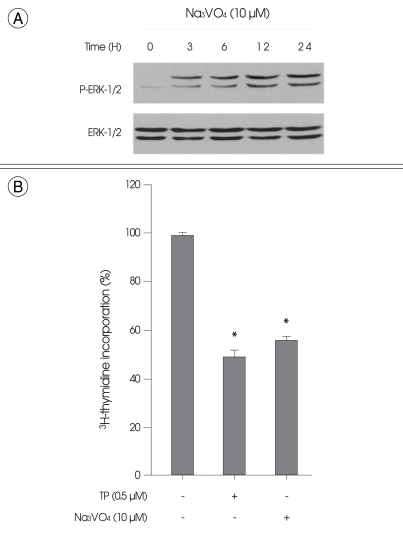

Treatment of HT22 cells with TP (0.5 µM) for 6 h resulted in ERK-1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 4A). In contrast, TP had no significant effect on the phosphorylation of either p38 MAPK or JNK-1/2 (Fig. 4A). The same results were also observed when the cells were transiently transfected with MKP-1 siRNA (Fig. 4A). The time course of ERK-1/2 phosphorylation level showed that ERK-1/2 phosphorylation by TP was detected throughout the time course experiment up to 24 h (Fig. 4B). Similarly, the phosphatase inhibitor vanadate at 10 µM, which has been used extensively for the blockage of MKP-1 enzyme activity by other investigators12,21-23), induced persistent ERK-1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 5A) and reduced cell growth (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of triptolide (TP) on phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) in immortalized HT22 cells. A : Cells were treated with 0.5 µM of TP for 6 h. The cells that were transiently transfected with MAPK phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) small interfering RNA (MKP-1 siRNA; lane 3) served as the control for MKP-1-dependent phosphorylation of MAPKs, and were cultured for 6 h. B : Cells were treated with 0.5 µM of TP for indicated times. Phosphorylation and expression of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 (ERK-1/2), the p38 MAPK and the c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1/2 (JNK-1/2) were examined by Western blot analysis, as described in materials and methods. Representative Western blots of three independent experiments are shown.

Fig. 5.

Effect of the phosphatase inhibitor vanadate on the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 (ERK-1/2) phosphorylation and proliferation of immortalized HT22 cells. A : Cells were treated with 10 µM of vanadate for indicated times. Phosphorylation and expression of ERK-1/2 were examined by Western blot analysis, as described in materials and methods. Representative Western blots of three independent experiments are shown. B : Cells were treated with 0.5 µM of triptolide or 10 µM of vanadate for 24 h. Cell proliferation was determined by 3H-thymidine incorporation, as described in materials and methods. Values represent mean ± SE of four replicates in three different experiments. *p < 0.05 versus untreated control cells.

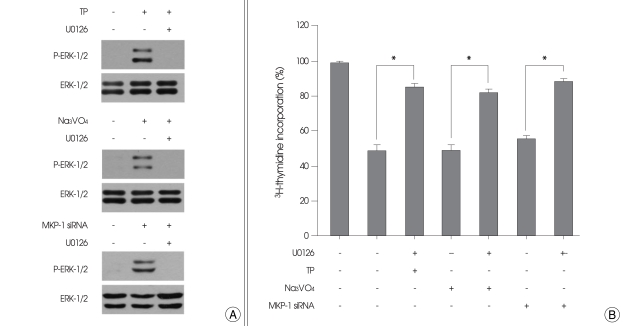

Finally, we investigated whether ERK-1/2 activation would involve in the inhibition of cell growth by TP, MKP-1 siRNA, and vanadate, using specific inhibitors for MAPKs. U0126, a specific ERK-1/2 inhibitor, completely inhibited the ERK-1/2 phosphorylation by TP, MKP-1 siRNA, and vanadate (Fig. 6A). When the cells were treated with U0126, the inhibitory effects of TP, MKP-1 siRNA, and vanadate on cell growth were also abolished (Fig. 6B). In contrast, a p38 MAPK inhibitor, SB203580, or a JNK-1/2 inhibitor, SP600125, had no effect on cell growth regardless of the presence or absence of TP, MKP-1 siRNA, or vanadate (not shown).

Fig. 6.

Effect of U0126 on cell growth inhibition by triptolide (TP), vanadate, and mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) small interfering RNA (siRNA). A : Immortalized HT22 cells were transiently transfected with MKP-1 siRNA, or treated for 6 h with 0.5 µM of TP or 10 µM of vanadate in the presence or absence of 10 µM of U0126. Phosphorylation and expression of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 were examined by Western blot analysis as described in materials and methods. Representative Western blots of three independent experiments are shown. B : Immortalized HT22 cells were transfected with MKP-1 siRNA or treated for 24 h with 0.5 µM of TP or 10 µM of vanadate in the presence or absence of 10 µM of U0126. Cell proliferation was determined by 3H-thymidine incorporation, as described in materials and methods. Values represent mean ± SE of four replicates in three different experiments. *p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

It is worthy to mention that TP can penetrate the blood-brain barrier easily because of its lipophilic character and small molecular size and may, thus, influence neuronal cells in the brain7,8). On the basis of the results presented here, it is most likely that TP may be effective in controlling the abnormal proliferation of malignant cells, such as a brain tumor. In our study, immortalized HT22 hippocampal cells were used as in vitro malignant cells, because of their ability to continually proliferate under normal culture condition6). Interestingly, MKP-1 is continually expressed during proliferation of HT22 cells20). We previously found that the down-regulation of MKP-1 expression by MKP-1 siRNA had no significant effect on cell viability7). The present study further confirmed that the blockage of MKP-1 expression by either MKP-1 siRNA or TP, an inhibitor for MKP-1, had no effect on cell viability; neither apoptosis nor necrosis was found in our study. Instead, TP completely blocked MKP-1 expression and significantly inhibited cell growth. Moreover, the same effects could be also observed when the cellular synthesis of MKP-1 and its enzymatic activity were blocked by MKP-1 siRNA and a phosphatase inhibitor, respectively. These findings raised the possibility that there could be a close relationship between the down-regulation of MKP-1 expression and the inhibition of cell growth. In this regard, the present study examined whether the down-regulation of MKP-1 expression by TP would account for its antiproliferative activity in immortalized HT22 hippocampal cells.

Since MKP-1 down-regulates ERK-1/2 activity via dephosphorylation5), we investigated whether the down-regulation of MKP-1 expression by TP could affect ERK-1/2 activation. Indeed, TP potentially induced ERK-1/2 phosphorylation, and the level of phosphorylated ERK-1/2 was sustained even for 24 h. This effect of TP on ERK-1/2 phosphorylation could be also mimicked by both MKP-1 siRNA and a phosphatase inhibitor, suggesting that the down-regulation of MKP-1 expression by TP could be responsible for the increased and persistent activation of ERK-1/2.

The rapid and transient activation of ERK-1/2 has been shown to correlate with the proliferative response14). In contrast, delayed and persistent activation of ERK-1/2 has been reported to inhibit cellular proliferation3). In our study, U0125, a specific inhibitor for ERK-1/2, abolished the inhibitory effects of TP on both ERK-1/2 phosphorylation and cell growth. Moreover, the antiproliferative effects of MKP-1 siRNA and a phosphatase inhibitor also abolished when ERK-1/2 phosphorylation was blocked by U0126. These findings suggest that the persistent activation of ERK-1/2 may account for the inhibition of cell growth by TP, MKP-1 siRNA, and vanadate. It should be noted that we could not detect the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and JNK-1/2 during TP exposure until 6 h. Moreover, treatment with specific inhibitors of p38 MAPK and JNK-1/2 failed to block the antiproliferative effects of TP and MKP-1 siRNA, suggesting that p38 MAPK and JNK-1/2 may not be involved in the inhibition of cell growth by TP.

MKP-1 has been extensively studied in the context of regulating various physiological processes, including cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and inflammation1). MKP-1 may function as a feedback control mechanism that governs cell growth and survival by limiting the activation of MAPKs. MKP-1 was found to be over-expressed in a number of human cancer tissues or immortalized cell lines9), and this may contribute to tumorigenesis. Interestingly, it has been reported that MKP-1-deficient fibroblasts exhibited reduced cell growth26). It has been also reported that the inhibition of MKP-1 expression using siRNA technology or synthetic inhibitors led to persistent ERK-1/2 activity and significant blockage of cytokine-dependent proliferation of macrophages25). In the light of these reports, it is most likely that TP at a non-cytotoxic dose can inhibit the proliferation of immortalized HT22 hippocampal cells via persistent activation of ERK-1/2 by suppressing MKP-1 expression.

CONCLUSION

The present study was undertaken to examine whether the down-regulation of MKP-1 expression by TP would account for its antiproliferative activity in HT22 hippocampal cells that were immortalized by viral oncogene. The data presented here suggest that TP at a non-cytotoxic dose inhibits cell growth via persistent activation of ERK-1/2 by inhibiting MKP-1 expression. Additionally, this study provides evidence that MKP-1 may play an important role in regulation of neuronal cell growth.

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by Wonkwang University in 2009.

References

- 1.Boutros T, Chevet E, Metrakos P. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase/MAP kinase phosphatase regulation : roles in cell growth, death, and cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:261–310. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.00106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke RE. Inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase and stimulation of Akt kinase signaling pathways : two approaches with therapeutic potential in the treatment of neurodegenerative disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;114:261–277. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerignoli F, Rahmouni S, Ronai Z, Mustelin T. Regulation of MAP kinases by the VHR dual-specific phosphatase : implications for cell growth and differentiation. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2210–2215. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.19.3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen LW, Wang YQ, Wei LC, Shi M, Chan YS. Chinese herbs and herbal extracts for neuroprotection of dopaminergic neurons and potential therapeutic treatment of Parkinson's disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2007;6:273–281. doi: 10.2174/187152707781387288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen P, Li J, Barnes J, Kokkonen GC, Lee JC, Liu Y. Restraint of proinflammatory cytokine biosynthesis by mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. J Immunol. 2002;169:6408–6416. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frederiksen K, Jat JS, Valtz N, Levy D, McKay R. Immortalization of precursor cells from the mammalian CNS. Neuron. 1988;1:439–448. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao JP, Sun S, Li WW, Chen YP, Cai DF. Triptolide protects against 1-methyl-4-phenyl pyridinium-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity in rats : implication for immunosuppressive therapy in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Bull. 2008;24:133–142. doi: 10.1007/s12264-008-1225-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiao J, Xue B, Zhang L, Gong Y, Li K, Wang H, et al. Triptolide inhibits amyloid-beta1-42-induced TNF-alpha and IL-1beta production in cultured rat microglia. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;205:32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keyse SM. Dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs) and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DW, Ahan SH, Kim TY. Enhancement of Arsenic Trioxide (As2O3)-Mediated Apoptosis Using Berberine in Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cells. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2007;42:392–399. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2007.42.5.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiviharju TM, Lecane PS, Sellers RG, Peehl DM. Antiproliferative and proapoptotic activities of triptolide (PG490), a natural product entering clinical trials, on primary cultures of human prostatic epithelial cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2666–2674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li B, Yang L, Shen J, Wang C, Jiang Z. The antiproliferative effect of sildenafil on pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells is mediated via upregulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 and degradation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 phosphorylation. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1034–1041. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000278736.81133.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH, Choudhry MA. A role of PP1/PP2A in mesenteric lymph node T cell suppression in a two-hit rodent model of alcohol intoxication and injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:453–462. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0705369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mebratu Y, Tesfaigzi Y. How ERK1/2 activation controls cell proliferation and cell death is subcellular localization the answer? Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1168–1175. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.8.8147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miloso M, Scuteri A, Foudah D, Tredici G. MAPKs as mediators of cell fate determination : an approach to neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:538–548. doi: 10.2174/092986708783769731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyata Y, Sato T, Ito A. Triptolide, a diterpenoid triepoxide, induces antitumor proliferation via activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1 by decreasing phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in human tumor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336:1081–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicolini G, Rigolio R, Scuteri A, Miloso M, Saccomanno D, Cavaletti G, et al. Effect of trans-resveratrol on signal transduction pathways involved in paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neurochem Int. 2003;42:419–429. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orton RJ, Sturm OE, Vyshemirsky V, Calder M, Gilbert DR, Kolch W. Computational modeling of the receptor-tyrosine-kinase-activated MAPK pathway. Biochem J. 2005;392:249–261. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owens DM, Keyse SM. Differential regulation of MAP kinase signaling by dual-specificity protein phosphatases. Oncogene. 2007;26:3203–3213. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pae HO, Jeong SO, Zheng M, Ha HY, Lee KM, Kim EC, et al. Curcumin attenuates ethanol-induced toxicity in HT22 hippocampal cells by activating mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1. Neurosci Lett. 2009;453:186–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palm-Leis A, Singh US, Herbelin BS, Olsovsky GD, Baker KM, Pan J. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases mediate the inhibitory effects of all-trans retinoic acid on the hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54905–54917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan MR, Chang HC, Hung WC. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs suppress the ERK signaling pathway via block of Ras/c-Raf interaction and activation of MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1134–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serini S, Trombino S, Oliva F, Piccioni E, Monego G, Resci F, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid induces apoptosis in lung cancer cells by increasing MKP-1 and down-regulating p-ERK1/2 and p-p38 expression. Apoptosis. 2008;13:1172–1183. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shepherd EG, Zhao Q, Welty SE, Hansen TN, Smith CV, Liu Y. The function of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 in peptidoglycan-stimulated macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54023–54031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408444200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valledor AF, Arpa L, Sánchez-Tilló E, Comalada M, Casals C, Xaus J, et al. IFN-γ-mediated inhibition of MAPK phosphatase expression results in prolonged MAPK activity in response to M-CSF and inhibition of proliferation. Blood. 2008;112:3274–3282. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-123604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu JJ, Bennett AM. Essential role for mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase phosphatase-1 in stress-responsive MAP kinase and cell survival signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16461–16466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao G, Vaszar LT, Qiu D, Shi L, Kao PN. Anti-inflammatory effects of triptolide in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L958–L966. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.5.L958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao Q, Shepherd EG, Manson ME, Nelin LD, Sorokin A, Liu Y. The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 in the response of alveolar macrophages to lipopolysaccharide : attenuation of proinflammatory cytokine biosynthesis via feedback control of p38. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8101–8108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Y, Ling EA, Dheen ST. Dexamethasone suppresses monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 production via mitogen activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 dependent inhibition of Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in activated rat microglia. J Neurochem. 2007;102:667–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]