INTRODUCTION

Pancreaticopleural fistula is a rare complication of acute and chronic pancreatitis caused by an inflammatory or traumatic injury to the pancreatic duct. The ensuing thoracic collections may be in the form of pleural effusions, pleural pseudocysts or mediastinal pseudocysts. Treatment options may be conservative or surgical. We present a case of post endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) acute pancreatitis with a pancreaticopleural fistula where conservative management failed.

CASE REPORT

A 51 year old lady presented with dyspnoea, cough, chest pain and a pleural effusion two months after recovering from an episode of ERCP-induced pancreatitis. A CT scan revealed pancreatic necrosis and bilateral pleural effusions. Bilateral chest drains were inserted and the amylase content of the pleural fluid was elevated at 5488 IU. The presence of a pancreaticopleural fistula was considered as a differential diagnosis. She developed multiorgan failure requiring ventilation, inotropic support and renal dialysis. A repeat CT scan (fig.1) revealed a pancreatic pseudocyst (7 × 2 cm), a mediastinal fluid collection, partial collapse of the left lung and bilateral pleural effusions (fig.2). Magnetic resonance cholangio-pancreatography (MRCP) suggested a fluid containing tract extending from the pancreas into the chest, associated with a collection in the left pleural cavity.

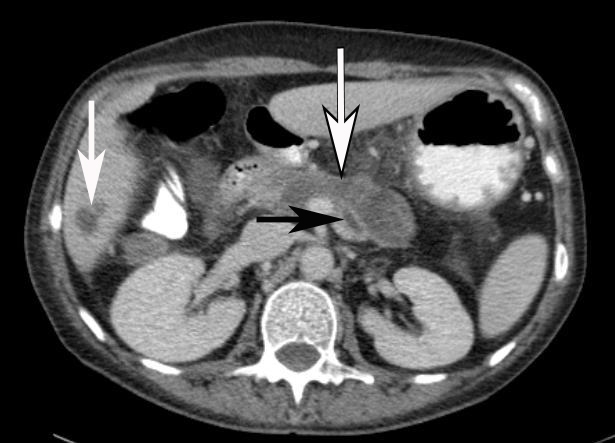

Fig 1.

CT of abdomen demonstrating 7×2cm pancreatic pseudocyst (outlined arrow) and dilated pancreatic duct (black arrow). Incidental finding of cyst in VI liver lobe (white arrow) is noted.

Fig 2.

CT scan of chest demonstrating collapse of the left lung and effusions in the left pleural cavity (arrows).

She initially improved clinically with supportive and conservative measures but deteriorated again and surgical drainage of the pseudocyst was undertaken via a cystgastrostomy. At operation a communicating tract leading superiorly through the oesophageal hiatus was identified. The wall of the cavity was sutured to the posterior wall of the stomach and a nasogastric tube was placed into the pseudocyst cavity to allow it to collapse and fibrose. Parenteral nutrition was commenced post-operatively. The pseudocyst and pleural effusions resolved. She was discharged on day 12 and remains asymptomatic with no evidence of recurrence after four years.

DISCUSSION

Pancreaticopleural fistula is an uncommon complication of both acute and chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic trauma with duct disruption. The majority of cases (80%) are associated with alcohol induced chronic pancreatitis1–3. There is an incidence of 0.4% in patients presenting with pancreatitis and 4.5% in those presenting with a pancreatic pseudocyst3. The pathogenesis involves recurrent, chronic inflammation of the gland eventually leading to ductal disruption. If this occurs posteriorly pancreatic secretions will tract through the retroperitoneal space via the path of least resistance to the pleural cavity4,5. Fistulization through the oesophageal or aortic hiatus is most frequent, although extension directly through diaphragmatic muscle has been reported6. Conversely, anterior ductal disruption is responsible for pancreatic ascites.

Clinical presentation is often misleading, as symptoms are usually associated with a significant pleural effusion, and consist of dyspnoea, cough and chest pain. Rarely do patients complain of abdominal pains typical of pancreatitis3,7. In one study only 52% of patients had a prior history of pancreatitis highlighting that a pancreaticopleural fistula may be the first presentation of significant pancreatic disease3. Pleural effusions of this nature tend to be large and recurrent despite repeated thoracocentesis. Frequently, the diagnosis is delayed and it is therefore of vital importance to have a high index of suspicion, enquire about excess alcohol consumption, assess nutritional status, and examine for the presence of ascites.

Pleural effusions associated with pancreaticopleural fistulae should be distinguished from the small, reactive, self-limiting left-sided effusions that commonly occur in 3–17% of patients with acute pancreatitis8. A pancreaticopleural fistula may be suspected on the basis of the clinical picture and an extremely elevated pleural fluid amylase level (normal range <150 IU/L) following thoracocentesis. Importantly, however, pleural fluid amylase may also be elevated in acute pancreatitis (<4000 IU/L), oesophageal perforation and certain neoplastic processes including lung adenocarcinoma, lymphoma and ovarian, rectal, cervical, breast and pancreatic carcinoma2.

The pleural effusions are predominantly left sided, however right sided and bilateral effusions occur in 19% and 14% of patients respectively. Simple chest radiography is the first line investigation but this provides only limited information about the fluid collection in pleural cavity. Currently, the gold standard for investigating pleural effusions is CT. It is very useful in determining the site and size of the effusion but overall ability to provide accurate delineation of the fistula is disputable2,8. MCRP and ERCP are also available to visualise the biliary tree and pancreatic duct. The latter is less sensitive but offers the therapeutic option of stent insertion1,2.

Currently there are no systematic studies evaluating the optimal management of pancreaticopleural fistulae and current methods derive from case reports and small case series1. Initial management should be directed at achieving symptomatic control of the pleural effusion, with thoracocentesis and chest drain insertion if required. Suppression of pancreatic exocrine secretions by somatostatin or its analogue octreotide should then be considered. In one study a combination of thoracocentesis, octreotide analogues and TPN resulted in a 48% closure rate after three weeks9. Surgical treatment, however, is safe and effective and is appropriate either when medical management fails or where the underlying condition requires surgical intervention. Cystgastrostomy, cystjejenostomy, and distal or middle segment pancreatectomy are appropriate options in the setting of symptomatic pancreatic pseudocysts or pancreatic duct obstruction. Finally, ERCP and pancreatic duct stenting is a less invasive alternative to surgery. Fistulae are unlikely to heal with medical measures alone if drainage is impaired by a pseudocyst or stricture. A pancreatic stent that bridges the ductal disruption facilitates closure of the fistula by decreasing ductal pressure and occluding the luminal defect1. Sphincterotomy and non-bridging stents have also been reported as being successful but overall a significant proportion of patients undergoing ERCP still ultimately require surgical intervention1. In one study, 7 of 18 cases managed endoscopically eventually required surgical intervention and even advocates of ERCP acknowledge that the issue of how long to persist with this form of treatment is, as yet, unresolved1,10.

CONCLUSION

Pancreaticopleural fistulae are difficult to diagnose and require a high index of suspicion, particularly in the setting of recurrent pleural effusions with a coexisting history of pancreatitis or alcohol abuse. Early pleural fluid amylase testing will avoid a delayed diagnosis. First line treatment includes drainage of the effusion, inhibition of pancreatic secretions with octreotide and possibly ERCP plus stenting of the pancreatic duct. As demonstrated by this case, surgery is appropriate when medical measures fail or if there is an associated symptomatic or complicated pseudocyst.

The authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dhebri AR, Ferran N. Nonsurgical management of pancreaticopleural fistula. JOP. 2005;6(2):152–61. Available online from: http://www.joplink.net/prev/200503/13.html Last accessed June 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockey DC, Cello JP. Pancreaticopleural fistula. Report of 7 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990;69(6):332–44. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fulcher AS, Capps GW, Turner MA. Thoracopancreatic fistula: clinical and imaging findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23(2):181–7. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199903000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron JL, Kieffer RS, Anderson WJ, Zuidema GD. Internal pancreatic fistulas: pancreatic ascites and pleural effusions. Ann Surg. 1976;184(5):587–93. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197611000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipsett PA, Cameron JL. Internal pancreatic fistula. Am J Surg. 1992;163(2):216–20. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(92)90104-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedingfield JA, Anderson MC. Pancreatopleural fistula. Pancreas. 1986;1(3):283–90. doi: 10.1097/00006676-198605000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shibasaki S, Yamaguchi H, Nanashima A, Tsuji T, Jibiki M, Sawai T, et al. Surgical treatment for right pleural effusion caused by pancreaticopleural fistula. Hepatogastroenterol. 2003;50(53):1678–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakefield S, Tutty B, Britton J. Pancreaticopleural fistula: a rare complication of chronic pancreatitis. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72(884):115–6. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.72.844.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cameron JL. Chronic pancreatic ascites and pancreatic pleural effusion. Gastroenterol. 1978;74(1):134–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neher JR, Brady PG, Pinkas H, Ramos M. Pancreaticopleural fistula in chronic pancreatitis: resolution with endoscopic therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52(3):416–8. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]