Abstract

The organization of metazoa is based on the formation of tissues and on tissue-typical functions and these in turn are based on cell–cell connecting structures. In vertebrates, four major forms of cell junctions have been classified and the molecular composition of which has been elucidated in the past three decades: Desmosomes, which connect epithelial and some other cell types, and the almost ubiquitous adherens junctions are based on closely cis-packed glycoproteins, cadherins, which are associated head-to-head with those of the hemi-junction domain of an adjacent cell, whereas their cytoplasmic regions assemble sizable plaques of special proteins anchoring cytoskeletal filaments. In contrast, the tight junctions (TJs) and gap junctions (GJs) are formed by tetraspan proteins (claudins and occludins, or connexins) arranged head-to-head as TJ seal bands or as paracrystalline connexin channels, allowing intercellular exchange of small molecules. The by and large parallel discoveries of the junction protein families are reported.

Werner Franke looks back over more than three decades of research into the structure and function of cell junctions.

In the year of the bicenturial jubilee of Charles Darwin (born 1809) and his 1859 publication of the concept of natural selection as the decisive driving force of evolution, it is perhaps appropriate to begin this review with the notion that the four major kinds of cell–cell junctions are among the oldest and most important structures contributing to the formation and functional diversification of multilayered metazoan organisms. From mere associations of individual cells, whether protozoan or parazoan, it was the cooperation of the molecular ensembles of these junctions to provide the basis for eumetazoan life. Note, however, that some protocadherin glycoproteins and armadillo-type proteins already occur in certain nonmetazoa (e.g., King et al. 2003; Nichols et al. 2006; for refs. Halbleib and Nelson 2006). In particular, diverse cell–cell junction molecules were—and are—needed to assemble and organize metazoan architecture, notably that of the Bilateria, to allow the formation of the epithelial layers of ectoderm and endoderm, mesoderm-derived tissues, and the segregation of diverse kinds of interstitial cells and the organs derived therefrom. So, it is not so surprising that major kinds of cell junctional structures already exist in the lowest divisions of eumetazoa (e.g., Hobmayer et al. 1996, 2000).

In general, metazoan animals possess three intercellular junction systems of the adhering type formed by characteristic transmembrane molecules and proteins that assemble into specific submembranous plaques (Table 1). A fundamentally different type, gap junctions, serves primarily as a system of assemblies of intercellular channels but also contributes to cell–cell adhesion. In summarizing the history of the discoveries of the molecular ensembles forming these junctions, it is striking that remarkably different arts of science and tribes of cell biologists have contributed to the progress in this field. The intercellular junctional systems are:

Desmosomes (maculae adherentes) are by far the most abundant junctions in stratified epithelia and have been studied with special impetus by researchers analyzing the cytoskeleton and tissue architecture, and by dermatologists.

Adherens junctions, including the zonulae and fasciae adherentes, have first attracted the special interest of developmental biologists because of their importance in mammalian embryogenesis.

Tight junctions (zonulae occludentes), and in particular the transmembrane molecules involved, had long been sought as this structure was important in controlling the paracellular transport of molecules and particles. Finally, the centrally important tetraspan proteins, desired by a generation of physiologists and membranologists, have been found as the result of careful cell particle fractionation work and immunoelectron microscopy.

Gap junctions (nexus) had always fascinated electron microscopists and crystallographers because of their esthetic paracrystalline substructural order, as well as physiologists studying lateral direct molecule exchange from cell to cell. Here, the stability of the structure itself helped in its isolation and reconstitution in vitro.

Table 1.

Constitutive molecular components of the major types of symmetrical (homotypic) junctions

| Occurrence | Associated filaments | Transmembrane proteins and glycoproteins | Specific plaque proteins | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DesmosomesMaculae adherentes | Epithelial cells, various types of cardiomyocytes, meningothelial cells, dendritic reticulum cells of the thymus and lymph follicles | Intermediate-sized filaments (keratins, vimentin, desmin) | Desmogleins 1–4a desmocollins 1–3a | Plakoglobinb desmoplakin I/II plakophilins 1–3a |

| Adherens junctionsZonulae adherentes Fasciae adherentes Puncta adhaerentia | Epithelial cells, endothelial cells, various types of cardiomyocytes, mesenchymal and neural cells | Microfilaments (actin) | Typical cadherinsa (e.g., E-cadherin, N-cadherin, P-cadherin, VE-cadherin, cadherin-11) | α- and β-Catenin, plakoglobin, protein p120, protein ARVCF, protein p0071, neurojungin (δ-catenin)a, (plakophilin-2c) proteins ZO-1, ZO-2, ZO-3 |

| Tight junctionsZonulae occludentes Fasciae occludentes Puncta adhaerentia | Epithelial cells, endothelial cells | –d | Occludin, claudins 1–24a tricellulin(s)e proteins of the JAMA-group, CARa, ESAMa | Proteins ZO-1, ZO-2, ZO-3, cingulin |

| Gap junctions (nexus) | All kinds of tissue-forming cells | – | Connexins 1–21a | Proteins ZO-1, ZO-2, ZO-3 |

Only established, i.e., repeatedly confirmed, constituent structural molecules are mentioned here; some further regulatory or peripherally associated molecules are not listed here but are discussed in the text.

aOne or combinations of a few representatives, with cell type and cell layer specificities.

bProteins of the so-called armadillo family are in italics.

cOnly in specific proliferatively active cells (Rickelt et al. 2009).

dActin microfilaments are seen near some tight junctions but their specific association is not clear.

eThere are at least two mRNA splice products but only one protein has so far been localized.

Thus, at about the same time in the late 1970s, when the ultrastructural organization and specificities of the diverse kinds of these junctions had been well determined (for reviews, see Farquhar and Palade 1963; Staehelin 1974), the race by cell biologists to elucidate the molecular compositions of these junctions began. Although this analytical research period is not quite over and a few new junction diamonds may still just lie around the corner, the prime interest of the community of cell biological researchers has already moved on to the next research arena, studying the mechanisms of junction formation and the functions of the junctions. Over the last two decades, these major structural elements of our bodies have also become objects of intense medical research, already with some startling results.

In the following, the by and large parallel searches for constituent molecules of the four major categories of cell–cell junctions in vertebrate cells is described. However, only constituents localized and confirmed by different groups and with various methods are mentioned as generally accepted components. This, of course, does not exclude the presence of others for which the available evidence does not yet seem sufficient. Furthermore, certain special types of junctions that do not fit one of the four major categories will be reviewed elsewhere (Franke et al. 2009).

HARD-CORE ANCHORS OF CYTOSKELETAL ELEMENTS: THE DESMOSOMES

The desmosomes represent a category of intercellular junctions that typically reveal a highly distinctive subarchitecture. They are abundant in epithelial and meningothelial tissues and cell cultures, as well as in certain types and stages of cardiomyocyte differentiation, but are also known to connect reticulum cells of the thymus and lymphatic follicles. Because of their relatively good preservation after diverse electron microscopic fixation procedures and their abundance in certain tissues (e.g., in some regions of the stratum spinosum of the epidermis and other stratified squamous epithelia, they occupy 50% or even more of the total cell surface), the ultrastructural principles of desmosome architecture were more or less already clear in the 1970s (see, e.g., Farquhar and Palade 1963; Campbell and Campbell 1971; Staehelin, 1974; for cardiomyocytes see Fawcett and McNutt, 1969).

The appearance of desmosomes in electron micrographs of ultrathin sections impresses observers by the parallel alignment of two trilaminar plasma membrane domains, an organized 20–30-nm interface (the “desmogloea”), which often reveals a dense midline structure (the glutinamentum), and periodical cross-striations between this midline and the plasma membranes (Fig. 1A,B). On their cytoplasmic side, the membranes of the desmosomal halves are coated by an electron-dense, 15–25 nm thick plaque, which, in turn, is coated by somewhat less dense material onto which in many, but not in all cells, bundles of intermediate-sized filaments (IFs) insert. Freeze-fractures further reveal the membrane interior of desmosomes as relatively loosely arranged arrays of clustered transmembrane complexes (Fig. 1C) (Leloup et al. 1979).

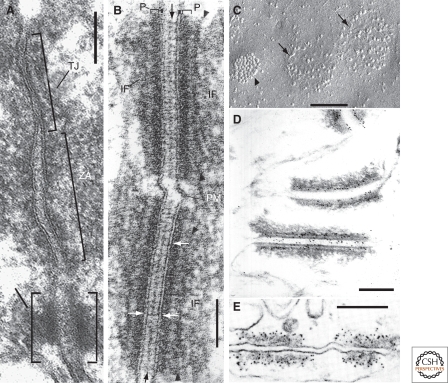

Figure 1.

Electron microscopic aspects of intercellular junctions, in particular desmosomes. (A) Characteristic subapical trias of tight junction (TJ), zonula adhaerens (ZA), and desmosome (D) of murine intestinal epithelial cells in a longitudinal section. (B) Higher magnification of two adjacent desmosomes in fetal (20 wk) human foot-sole epidermis, showing desmosomal substructures (black arrows: midline structure; white arrows: trilaminar “unit membrane” structure of the plasma membrane domain proper, also pointing to electron dense cross-bridge structures; arrowheads: secondary dense layer of the plaque; P: electron-dense primary plaques; IF; anchoring structures of intermediate-sized filaments). (C) Freeze-fracture image of spinous layer of murine epidermis, showing the intramembranous fracture plane of the plasma membrane with two desmosomes (arrows) and a gap junction (arrowhead). Note the typical paracrystalline packing of the connexin substructures in the gap junction in comparison with the loosely and irregularly arranged transmembrane elements of the desmosomes. (D) Immunoelectron microscopy of an ultrathin section through an epithelium, showing the immunogold decoration (5-nm particles) of desmoplakin at—or near—the desmosomal plaque structures. (E) Immunoelectron microscopy of an ultrathin cross-section through the zonula adhaerens of plasma membranes connecting two endothelial cells of a cardiac capillary, showing the specific 5-nm immunogold decoration of the junctional plaque with plakoglobin antibodies, thus demonstrating that plakoglobin can also occur in the plaques of nondesmosomal adhering junctions. Bars denote 0.1 µm (A, B) and 0.5 µm (C–E). For details, see Cowin et al. (1985a), Franke et al. (1987b), Kapprell et al. (1987), and Schlüter et al. (2007).

The basis for biochemical analyses and the molecular identification of components was laid by a good choice of appropriate tissues, for example bovine muzzle epidermis, for the enrichment of isolated desmosomal structures. The results were markedly dependent on the specific fractionation method used, with more or less preserved plaque structures and “contaminations” by other elements, in particular IF bundle residues (e.g., Skerrow and Matoltsy 1974a,b; Drochmans et al. 1978; Colaco and Evans 1981; Franke et al. 1981; Gorbsky and Steinberg 1981; Mueller and Franke 1983; for review see Skerrow 1986). Although gel electrophoretic analyses of proteins from such fractions allowed some educated guesses about molecular components of desmosomes, it took the direct demonstration of specific proteins by immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy to provide definitive evidence of desmosomal protein localizations. This was first presented at the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium on the “Organization of the Cytoplasm” in the summer of 1981 for the major desmosome-specific plaque protein, desmoplakin, using antibodies that identified desmoplakins I and II and some proteolytic breakdown products thereof (cf. Franke et al. 1982b; see also Franke et al. 1981, 1982a,b) (for an example, see Fig. 1D). Later, K. Green and her group determined that desmoplakins I and II are two splice mRNA forms derived from the same gene and that this large protein presents a very special organization with a near–amino-terminal plakin domain, a central coiled–coil region, and a so-called plakin-repeat domain in the carboxy-terminal portion (Green et al. 1988, 1990; Virata et al. 1992; Godsel et al. 2004), so to say the prototype of what later was termed the “plakin family” of proteins (Ruhrberg and Watt 1997).

The identification of the desmoplakins was soon followed by the localization of epidermal-type desmosomal proteins and glycoproteins in various cell types and species, although not in all cells that were known to contain true desmosomes (cf. Cohen et al. 1983; Cowin and Garrod 1983; Mueller and Franke 1983; Cowin et al. 1984a,b, 1985a,b; Giudice et al. 1984; Gorbsky et al. 1985). As an explanation for cell-type differences, the problem of cell-type specific proteins of complex gene families arose, an experience this research field had just come across with the bewildering complexity of IF proteins.

Two additonal constitutive proteins of desmosomal plaques were identified based on peptide mapping and immunoblotting: They were originally counted as desmosomal bands five- and six-proteins (Franke et al. 1983b) and later named plakoglobin and plakophilin-1 (see also Table 1). Plakoglobin was a particularly challenging component as it turned out also to be a major protein of the plaques of diverse morpho-types of adherens junctions (AJs), including the zonulae adherentes of endothelia (e.g., Fig. 1E) (Cowin et al. 1986; Franke et al. 1987a,b). Plakoglobin was also a very attractive molecule for cDNA- and gene-cloning and soon after the human amino acid sequence had been published (Franke et al. 1989, 1992; Fouquet et al. 1992), Peifer and Wieschaus (1990) recognized that plakoglobin was a close homolog to the armadillo protein encoded by the Drosophila melanogaster segment polarity gene (see also McCrea et al. 1991). This finding resulted in an avalanche of publications leading to the definition of a large and important multigene family, the armadillo (arm) proteins of adhering junctions in general, i.e., AJs and desmosomes. This family includes a number of components (e.g., plakoglobin, β-catenin, proteins p120, p0071, ARVCF, neurojungin, and the plakophilins) that serve more than one function and occur in junction-bound forms as well as in special cytoplasmic and nuclear forms (Peifer et al. 1992, 1994; for reviews, see Hatzfeld 1999; Schmidt and Koch 2008).

In parallel, several laboratories had begun to clone and identify the genes encoding the polypeptide chains of the two prominent desmosomal glycoproteins, desmoglein (Dsg) and desmocollin (Dsc), again starting with RNA isolated from bovine muzzle or related stratified epithelia. Both the Dsg and Dsc molecules revealed amino acid sequences and carbohydrate branch sites that were markedly homologous to those of the “classic” cadherins such as E- and N-cadherin, which had just been identified as the major transmembrane AJ molecules (Koch et al. 1990, 1991a,b; Goodwin et al. 1990; Holton et al. 1990; Amagai et al. 1991; Collins et al. 1991; Mechanic et al. 1991; Nilles et al. 1991; Parker et al. 1991; Wheeler et al. 1991a,b; King et al. 1993a,b; Theis et al. 1993). Remarkably, in less than 3 years, the cDNAs of all six known desmosomal cadherins were cloned and sequenced. Again, however, these amino acid sequences showed that Dsg and Dsc from different cell types differed from each other. Furthermore, the cytoplasmic carboxy-terminal portion of Dsg contained several distinct sequence subdomains (Koch et al. 1990; reviews: Franke et al. 1992; Koch and Franke 1994; Garrod et al. 2002; Godsel et al. 2004) and not only spans the plasma membrane but also extends through the cytoplasmic plaque, as shown by the accessibility to antibodies directly injected into living cultured cells (Schmelz et al. 1986a,b).

Both Dsg and Dsc appeared in cell type- and cell layer-specific subforms (Parrish et al. 1990; Buxton and Magee 1992; Koch et al. 1992; Buxton et al. 1993; King et al. 1993a,b, 1995, 1996, 1997; Koch and Franke 1994). Only one of each group, Dsg2 and Dsc2, was found in all proliferative cells such as one-layered (“simple”) epithelia, basal cell layers of stratified epithelia, meningothelia, cardiomyocytes, and reticulum cells of lymphatic tissues (Schäfer et al. 1994, 1996; Nuber et al. 1995, 1996). By contrast, highly differentiated upper cell layers of several stratified epithelia contained Dsg1 and Dsc1 as predominant desmosomal cadherins, often together with Dsg3 and Dsc3 (Arnemann et al. 1993; King et al. 1993b, 1997; Theis et al. 1993; Legan et al. 1994; Nuber et al. 1996). Dsg4 was a very late addition, synthesized only in the uppermost living cell strata of the epidermis (Kljuic et al. 2003; Bazzi et al. 2006; reviews: Godsel et al. 2004; Schmidt and Koch 2008).

It is striking in desmosomes that both Dsg and Dsc almost always appear together as a pair, probably forming isostoichiometric oligomers that are stabilized by plakoglobin (see, e.g., Troyanovsky et al. 1993, 1994a,b, 1996; Chitaev et al. 1996; Witcher et al. 1996; Chitaev and Troyanovsky 1997; Marcozzi et al. 1998; review: Troyanovsky 2005). Therefore, it came as a surprise when it was recently noted that at least in some nonepithelial cell types (e.g., melanocytes and melanoma cells growing in culture, and melanoma cells in situ), a desmosomal glycoprotein, Dsg2, can occur as an abundant surface component out of any junctional complex (Schmitt et al. 2007; Rickelt et al. 2008).

The last elucidated subfamily of desmosomal components were the plakophilins, apparently located deep in the plaque (see, e.g., Mertens et al. 1996; for differential electron microscopy of desmosomal components, see North et al. 1999; Stokes 2007). Plakophilin was originally numbered as “band 6 protein” in bovine muzzle desmosomes and had been identified as a protein restricted to stratified and complex epithelia (Kapprell et al. 1988). However, it still took several years until the amino acid sequence of this protein, then named plakophilin-1, had been determined as another arm-protein (Schäfer et al. 1993; Hatzfeld et al. 1994; Schmidt et al. 1994). This protein was soon followed by plakophilin-2, the most widespread member of this subgroup of arm-proteins and the only one present in the desmosomes of simple epithelial cells as well as in nonepithelial desmosomes (Mertens et al. 1996, 1999). Finally, plakophilin-3, which coexists with plakophilin-2 in many desmosomes, has also been sequenced and localized (Bonné et al. 1999, 2003; Schmidt et al. 1999). Similar to plakoglobin and β-catenin, plakophilins are frequently found in distinct particles in the nucleus and the cytoplasm, and such particles may include essential nuclear components such as the complexes containing RNA polymerase III (e.g., Mertens et al. 1996, 2001; Schmidt et al. 1997; Bonné et al. 1999).

With remarkable speed, the cell biological insights obtained and the reagents generated for desmosomes were introduced into developmental biology and the medical sciences. Desmosomal molecules could be shown in very different normal and malignantly transformed cell types, either in layers of tightly associated cells or in arrays resembling spinous layer-type growth forms, in which the cells are connected by special bridges containing desmosomes (Fig. 2A,B) as well as AJs of the puncta adherentia type (Vasioukhin et al. 2000). Moreover, the use of subtype-specific antibodies against members of the plakophilin and the cadherin glycoprotein families allowed the determination of not only the cell type but also a certain state of epithelial differentiation in normal tissues and in tumors (Koch et al. 1992; King et al. 1995, 1996, 1997; Nuber et al. 1995, 1996; Schäfer et al. 1996). Consequently, very soon after their first publications in scientific journals, antibodies against cell-type-specific desmosomal proteins were added to the immunodiagnostic armamentarium of pathologists (e.g., Franke et al. 1983a; Schwechheimer et al. 1984; Denk et al. 1985b; Parrish et al. 1986, 1987; Vilela et al. 1987; reviews: Moll et al. 1986; Garrod et al. 1996; Kottke et al. 2006).

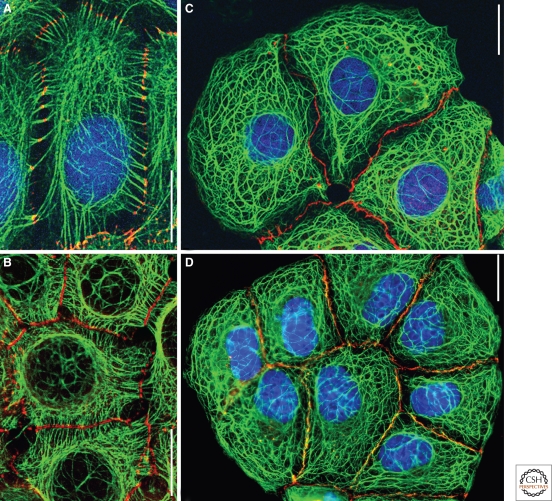

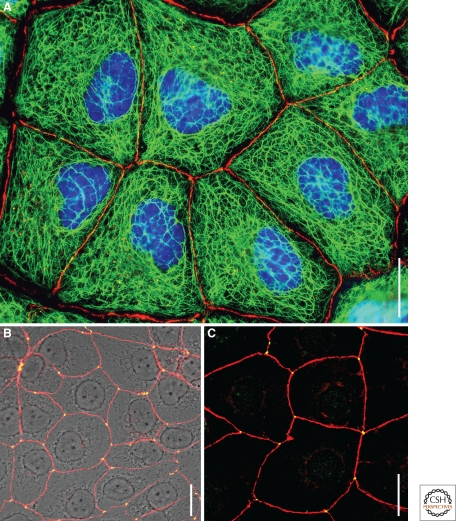

Figure 2.

Double-label immunofluorescence microscopy of monolayer cultures of epithelial cells derived from human multilayered (A, keratinocytes of line HaCaT; B, squamous cell carcinoma-derived line A-431) or one-layered (C, D: liver carcinoma cells of line PLC) tissues. Two forms of attachment of bundles of keratin IFs (green, mouse monoclonal antibody mAb lu-5) to the plaques of desmosomes (A, B: red, desmoplakin, guinea pig antibodies) represent a continuous transcellular cytoskeletal system (the chromatin in the nuclei of A, C, and D is stained blue with DAPI reagent): The cells in A are connected by cell-to-cell bridges with near-centrally located desmosomes, whereas in B the bodies of the cells are directly and tightly associated with each other via numerous, closely spaced desmosomes. In contrast, no specific anchorage of keratin IF bundles is seen at cell junctions of the zonula or punctum adherens type, which are seen by immunoreaction for β-catenin (C, red, guinea pig antibodies) or protein p0071 (D, red, murine mAb). Bars: 20 µm.

Specific probes for desmosomal molecules and their genes soon allowed valuable and pioneering contributions to the elucidation of, for example, autoantibody-caused diseases such as those of the pemphigus kind (Korman et al. 1989; Amagai et al. 1991; reviews: Amagai 1999; Kottke et al. 2006; Holthöfer et al. 2007; Schmidt and Koch 2008; Waschke 2008; see also Delva et al. 2009). Notably, studies of the molecular biology of the genes encoding desmosomal proteins, in particular gene abrogation experiments in mice (e.g., Bierkamp et al. 1996; Ruiz et al. 1996; Gallicano et al. 1998, 2001; Grossmann et al. 2004; Zhou et al. 2004), paved the way for the identification of the causes of a large proportion of human hereditary cardiomyopathies, most strikingly the majority of the forms of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathies, which often lead to so-called “sudden death” (Gerull et al. 2004; Franke et al. 2009; and Delva et al. 2009).

The definition of the molecular ensembles characteristic of various types of desmosomes and the reagents to distinguish desmosomal and desmosome precursor assemblies from components of AJs (Geiger et al. 1983) also provided the basis for studies of molecular mechanisms involved in the intracellular assembly of desmosomes, their IF anchorage, their exocytotic exposure on the cell surface, and their endocytotic resumption, notably on depletions of Ca2+ ions in the surrounding media (e.g., Kartenbeck et al. 1982, 1991; Watt et al. 1984; Duden and Franke 1988; Pasdar and Nelson 1988a,b; Stappenbeck et al. 1993; Kowalczyk et al. 1994, 1997, 1998; Demlehner et al. 1995; Bornslaeger et al. 1996; Palka and Green 1997; Smith and Fuchs 1998; Hofmann et al. 2000; Chen et al. 2002; Koeser et al. 2003; Goossens et al. 2007; see also Green et al. 2009). Desmosomes had changed from stable anchor structures to highly dynamic cell elements and had finally become subjects of general physiological research.

Aside from the structure-bound states of desmosomal proteins in junction plaques and in nuclear or cytoplasmic particles, it had also become clear that the dynamic basis of all the reactions, the diffusible “regulation-ready” form, must exist somewhere in the cell. This “free” soluble form, however, is one of the most under-researched entities. The major soluble state of only plakoglobin, a 7S dimer, has been determined so far (Kapprell et al. 1987; see also Fouquet et al. 1992).

The molecular definition of true desmosomal components had also allowed the observations that in certain cell types these junctions do not anchor bundles of keratin IFs but rather vimentin IFs (Kartenbeck et al. 1984; Schwechheimer et al. 1984; Moll et al. 1986). Desmin-rich IFs and actin-containing myofilaments have also been shown to insert at the desmosomes and areae compositae of cardiomyocytes (Table 1) (Franke et al. 1982a, 2006; Kartenbeck et al. 1983). Note also that it was shown early on that the formation and maintenance of desmosomes can occur independently of anchorage to IFs (Denk et al. 1985a), indicating that desmosomes have functions other than as anchors and organizers of IF bundles (Green and Gaudry 2000).

THE DECADE OF THE ARMADILLOS AND THE MOLECULAR DIVERSITY OF ADHERENS JUNCTIONS

The discovery of the molecular ensembles forming the plaque-coated AJs has a history very different from that of the research on desmosomes. Here, seminal findings had been made many decades back and almost exclusively in the field of developmental biology. At the turn of the previous century, embryologists and zoologists recognized the importance of certain cell-surface entities for specific cell–cell adhesion and cell sorting in animal embryology as well as in tissue-like cell assemblies in culture dishes, from sponges and polyps to amphibian and chicken embryos, and, ultimately, mammalian organ development and regeneration (reviews to be recommended here: Wilson 1907; Holtfreter 1939; Moscona 1962; Okada 1996).

In the late 1970s, several research groups attempted to identify the molecules and the molecular principles governing cell sorting and adhesion mechanisms essential in embryogenesis. Steinberg (1958) recognized the general importance of Ca2+ ions in these processes. Following the phenomenon of Ca2+-mediated cell–cell assemblies to higher order structures, Takeichi’s group in Kyoto identified a glycoprotein of around 150 kDa mol. wt. (Takeichi, 1977), which a few years later was described—somewhat down-sized to 124 kDa—as a central player in cell–cell adhesion events, in particular in “morula compaction” of early embryogenesis. Consequently, this molecule was named “cadherin” for its Ca2+ dependence and cell adhesion effect (Yoshida-Noro et al. 1984; see also Yoshida-Noro and Takeichi 1982).

The Kyoto group was not alone in their search for the cell surface molecules involved in cell–cell interaction and homophilic sorting in early embryogenesis. Using different experimental approaches, the groups of G. Edelman in New York and F. Jacob in Paris had also embarked on the elucidation of these embryonal cell-adhesion principles and had independently arrived at the same kind of major interaction molecule, which they named uvomorulin, a molecule and concept that was then followed further by R. Kemler’s group (Kemler et al. 1977; Hyafil et al. 1980, 1981; Peyrieras et al. 1983; Vestweber and Kemler 1984, 1985; Boller et al. 1985; Ringwald et al. 1987), or L-CAM (Edelman et al. 1983; Gallin et al. 1983, 1987; Cunningham et al. 1984; see also Thiery et al. 1984). Other groups, using slightly different experimental approaches, called this glycoprotein A-CAM (Volk and Geiger 1984; Geiger et al. 1985a,b) or “glycoprotein Cell-CAM 120/80” (Damsky et al. 1983, 1985). In parallel studies using cell culture approaches, W. Birchmeier and his collaborators (Imhof et al. 1983; Behrens et al. 1985) had also identified this cell-surface glycoprotein, which turned out to be E-cadherin, and the “120/80 kDa” polypeptides were soon identified as a mixture of intact and truncated E-cadherin molecules. So, at a small expert meeting entitled “The Cell in Contact” on the campus of Rockefeller University in 1985, the representatives of these groups recognized that in the previous years they all had worked on the same molecule, the first AJ-specific component identified (for reviews, see Cunningham 1985; Damsky et al. 1985; Edelman 1985; Geiger et al. 1985a; Takeichi et al. 1985; Thiery et al. 1985).

As with the identification of desmosomal proteins, the identification of a cadherin was not the end of a research track but the beginning of a global outburst of hectic and cell biology-complicating work, as it started simultaneously two avalanches of cell type-specific proteins, the “cadherins” and the “armadillos.” Luckily, effective cDNA cloning methods were already at hand so that in only a few years the major cell type-specific cadherins were sequenced and could be localized by effective antibodies: E-cadherin (Gallin et al. 1983; Schuh et al. 1986; Bussemakers et al. 1993), N-cadherin (Hatta and Takeichi 1986; Hatta et al. 1987, 1988; Nose and Takeichi 1986), P-cadherin (Nose and Takeichi 1986; Nose et al. 1987), and the vascular endothelium-characteristic VE-cadherin (Lampugnani et al. 1995; Dejana 1996; Dejana et al. 2000). Finally, more than 50 members of a large “superfamily” in mammals have been identified, including so-called “classic” cadherins, “type II cadherins,” and “protocadherins” (reviews: Takeichi 1988, 1990; Gumbiner 1996; Nollet et al. 2000; Angst et al. 2001; Wheelock and Johnson 2003; Perez and Nelson 2004; Halbleib and Nelson 2006), not to mention the bewildering numbers of cadherins and their splice variants in some other parts of the animal kingdom (for arthropod cadherins, see, e.g., Hsu et al. 2009). Each of these newly discovered cadherins immediately produced “daughter avalanches” of publications dealing with the molecular interactions of the specific cadherins with each other and with AJ plaque proteins, the regulation of assembly or disassembly of AJs, and the functions of different cadherins during development and in the mature tissue, beginning with the study of Matsunaga et al. (1988; see also Meng and Takeichi 2009). In addition, each of the identified cadherins immediately produced questions as to its molecular complex state (for evidence of Ca2+-dependent cis-homodimers, see, e.g., the E-cadherin study by Takeda et al. 1999).

During the early period of cadherin discoveries, a number of researchers noted the biological specificity of the cadherin ensemble of a given cell type but also that there are examples of drastic changes of the type of cadherin produced when cells change their character, for example during wound healing (e.g., Hinz et al. 2004). A very conspicuous change often occurs when epithelial cells turn into mesenchymal cells during development, and when cells transform to malignancy and develop to carcinomas. Increased malignancy often appeared to be associated with the down-regulation of E-cadherin and an up-regulation or even induction of N-cadherin (e.g., Behrens et al. 1989, 1993; Frixen et al. 1991; Mareel et al. 1991, 1994; Vleminckx et al. 1991; Birchmeier et al. 1993, 1995). In addition, an increasing number of cadherin mutations and mRNA splicing errors have been reported that result in, or at least contribute to, carcinogenesis (e.g., Kanai et al. 1994). These principles were in a short period of time confirmed many times and have opened a totally new avenue of cancer research (for recent reviews, see Brabletz 2004; Strumane et al. 2004; Wheelock et al. 2008; see also Berx and van Roy 2009).

In parallel, we all had to watch with care and concern the other avalanche of reports on discoveries of proteins located in the cytoplasmic AJ plaque and directly or indirectly complexed with the cadherins. Soon after the discovery of the prototypic arm-protein, β-catenin, in 1989, this name could then only be used in the plural form (Tables 1 and 2): Six arm-proteins plus the actin-binder and -regulator, α-catenin, were identified in a short time, including some that are restricted to certain cell types and diseases (Ozawa et al. 1989, 1990a,b; Peifer and Wieschaus 1990; Nagafuchi et al. 1991; McCrea and Gumbiner 1991; McCrea et al. 1991; Peifer et al. 1992). Indeed, some of them were so specific that diverse AJ subforms could readily be distinguished not only from desmosomes but also from each other (e.g., Figs. 2C,D and 3).

Table 2.

The armadillo-report avalanche in the 1990s: Some results on arm-repeat and associated actin-interacting proteins in plaques of AJsa

aIncluding some recent review articles.

bHomologous proteins: ezrin, radixin, moesin, and merlin.

cIQ-domain GTPase-activating proteins.

Figure 3.

High-resolution double-label immunofluorescence (A–C) and immunoelectron (D) microscopy of monolayer cell cultures of human breast-carcinoma cells of line MCF-7, as seen after reactions with antibodies to the desmosomal plaque component, desmoplakin (green, guinea pig antibodies), or to the adherens plaque protein, p0071 (red, as in Fig. 2B), as seen on the background of differential interference contrast (DIC) (A), allowing for the most part to distinguish the small puncta adhaerentia from the similarly small desmosomes, located side-by-side. (B, C) Higher magnification micrographs of cells as shown in A, presenting details of cell–cell junctions along close membrane contact regions, allowing to distinguish in many places the alternating pairs of symmetrical plaques of desmosomes (green) and puncta adhaerentia (red). (D) Equivalent comparison at the electron microscopic level, showing an ultrathin section through junctions after immunogold reaction of puncta adhaerentia with antibodies to protein p0071 (brackets, immunogold granules enhanced by secondary silver reaction), in comparison with the negative small desmosomes (D). For details, see Hofmann et al. (2008, 2009). Bars: 20 µm (A), 5 µm (B, C), and 0.1 µm (D).

Perhaps the greatest surprise and an additional attraction for researchers were observations that several of the arm-proteins were detected and seemed to function in very distant and different places in the cell: as structure-integrated rather insoluble components of junctional plaques, and as components of diffusible, relatively small regulatory complexes in the nucleus, involved in diverse processes including gene transcription and other nuclear functions. Thus, it was almost to be expected that an ever increasing number of cell biology groups embarked on research projects trying to unravel the molecular interactions of these proteins, both in the AJ plaques and in nuclei. This led to the founding of several new fields of regulatory cell biology, perhaps best illustrated by the affluence of reports on arm-proteins involved in regulatory pathways, including the Wnt-pathway (Choi and Weis 2004; Brabletz 2004; Drees et al. 2005; Lewis-Tuffin and Anastasiadis 2008; see also Heuberger and Birchmeier 2009, and Cadigan and Peifer 2009). Finally, it should be noted that sizeable portions of arm-proteins generally occur in small diffusible forms in the cytoplasm, such as in the maternal pools of the amphibian ooplasm (e.g., Fouquet et al. 1992).

Some puzzling complications, however, were brought to the field of “cadherinology” by discoveries of a series of special, carboxy-terminally truncated cadherins, i.e., molecules with a significantly longer extracellular portion, but only a very short, e.g., 20 amino acids, cytoplasmic portion. These cadherins included mammalian LI-cadherin found in the polar simple epithelia of liver and/or intestine (Berndorff et al. 1994; Kreft et al. 1997), and Ksp-cadherin of certain kidney epithelia (Thomson et al. 1995). An even further truncated type of cadherin was found in which a normal extracellular element comprising five repeating elements lacked a membrane-anchor but was attached to the plasma membrane by a glycosylphospatidyl inositol residue (for T-cadherin, see Ranscht and Dours-Zimmermann 1991; Tanihara et al. 1994). However, these cadherins are not integrated into an AJ structure but widely scattered over the plasma membrane.

In the mid 1990s, just when the cell biological community thought that it finally knew the composition of AJs, again a disturbing call “halt—not so fast” was heard. The group of Y. Takai had identified yet another cell surface membrane complex, in this case with major transmembrane molecules of the immunoglobulin-like category: The nectins represent a family of four major and several minor (splice-) isoforms that can bind to each other in trans-interactions in a Ca2+-independent mechanism. They are bound to a submembranous plaque-type protein, afadin, which also occurs in several splice variants and in turn is associated with some specific actin-binding proteins, one of which has been named ponsin. This complex was observed close to, and often colocalizing with, AJ structures (Mandai et al. 1997; Takahashi et al. 1999; Satoh-Horikawa et al. 2000; for reviews see Takai and Nakanishi 2003; Irie et al. 2004; Takai et al. 2008a,b). Afadin apparently can also interact with α-catenin, thus providing the possibility of an indirect actin microfilament bridge connection between nectin and cadherin complexes (e.g., Tachibana et al. 2000; see also Takai et al. 2008a). So, why have these “Takai group” molecules still not been “officially” added to the AJ ensemble? One remaining problem is that although they colocalize, even at the electron microscopic level, with some of the typical AJ structures, for example with the zonula adhaerens of polar epithelia, they have not been seen to occur in other AJs such as those of the nearby puncta adhaerentia along the lateral surfaces of the same cells (e.g., Mandai et al. 1997; Takai et al. 2008a,b). Another problem is that components of these two strikingly close structural complexes have not been coimmunoprecipitated or cross-linked by short-distance chemical cross-linkers. However, recent studies indicate that the nectin–afadin transmembrane elements play an important pioneering and dynamic role in AJ assembly because the nectin complex provides the first cell–cell contact structures between two cells whereupon the cadherin-containing AJ elements follow (Takai et al. 2003, 2008a,b; see also Meng and Takeichi 2009).

Finally, a special “border guard” role has been ascribed to the groups of relatively small puncta adhaerentia-type AJs, which in certain brain regions surround neural synapses and seem to be important in the formation and maintained organization of the spatial junction relationship and the proper functioning of these specific synapses (Uchida et al. 1996; see Giagtzoglou et al. 2009).

THE SECRETS OF THE KISSES: THE MEMBRANE MOLECULES FORMING TIGHT JUNCTIONS

The electron microscopic appearance of the subapical TJs of simple epithelial cells (zonulae occludentes) was relatively well-known since the mid 1970s. Transmission electron microscopy of cross sections showed one or a few rather small direct contact sites of the two plasma membranes, commonly called “kisses.” Planar freeze-fractures through the membrane interior revealed, after metal-shadowing, a linear, or ornamentally woven in some tissues, branched relief of one or several ridges (Farquhar and Palade 1963; Goodenough and Revel 1970; Friend and Gilula 1972; Claude and Goodenough 1973; Staehelin 1974; Montesano et al. 1975; Hull and Staehelin 1976; Diamond 1977; reviews: Schneeberger and Lynch 1992; Mitic and Anderson 1998; Förster 2008; see also Goodenough and Paul 2009). Early on, it was also obvious that this structure must be most important in the establishment, maintenance, and functions of epithelia and endothelia, and hence in metazoan life in general. Most convincingly, the barrier role of TJ structures for paracellular diffusion, transport processes, and particle translocations had been directly shown by electrophysiological experiments and by electron microscopy using heavy metal-labeled tracers (see also Anderson and Van Itallie 2009). It had also been suggested that a number of physiological phenomena and diseases, from tissue swellings to liquid losses, were caused by partial or transient interruptions of such a barrier (e.g., Claude 1978; Madara and Dharmsathaphorn 1985; Simons 1990; Matter and Balda 1999; Van Itallie and Anderson 2006). Naturally, this field of research was closely watched by pharmacologists and drug developers awaiting the emergence of principles or molecules that would allow restoration of an interrupted barrier, or to induce a controlled transient permeability of the blood-brain-barrier for drugs of other components.

Molecular candidates and insights, however, arrived only dropwise. The first relevant discovery was made by Stevenson et al. (1986) who isolated and localized a component of the relatively thin plaque on the cytoplasmic face of TJs, therefore named protein ZO-1 (“zonula occludens”-1; identical to the ca. 220-kDa protein described by Itoh et al. 1991, 1993), which was later followed by the identification of ZO-2 (Gumbiner et al. 1991) and ZO-3 (Haskins et al. 1998). These proteins were founding members of the so-called MAGUK (membrane-associated guanylate kinase) family of proteins (for homologous proteins in invertebrates, see the finding in Drosophila by Willott et al. 1993), which soon turned out not to be exclusive for TJs but to be almost as regularly found in AJ- and GJ-associated plaques (Tables 1 and 2) (for reviews, see Anderson 1996; Balda and Matter 2000). These proteins can also occur in the nucleus (Gottardi et al. 1996) and in several other locations and functions, from transcriptional factors to regulators of the behavior of tumor cells (see the anthology edited by Cereijido and Anderson 2001, and the reviews of González-Mariscal et al. 2003; Gottardi and Niessen 2008).

Soon thereafter, Citi et al. (1988, 1989, 1991) discovered and localized another major TJ plaque protein of ∼Mr 140 kDa, which they named cingulin (from the Latin cingulum, i.e., stringlike girdle), which is clearly TJ-specific, albeit seemingly confined to epithelial TJs (e.g., Cordenonsi et al. 1999; Citi 2001; Fanning 2001). Altogether, about a dozen TJ plaque proteins have now been described, but so far their detailed molecular interactions and locations have only partly been elucidated. Although for some of them only molecular complexes with classic TJ components have been reported, others, again, show the phenomenon of dual localization outside of TJs (reviews: Citi 2001; Fanning 2001).

But what was the “core of the barriers,” the “real seal,” the “nature of the kisses,” the “hydrophobic transmembrane stuff?” Here, a first answer came at Christmas 1993 as a present, an unexpected major breakthrough in TJ membranology, a fruit of both “good old” cell fractionation work combined with biologically conceived strategic experimentation. “The Tsukitas,” Sachiko and Shoichiro, already known for the high-quality standard of their plasma membrane fractions from liver tissue (Tsukita and Tsukita 1989) and profiting from the enthusiasm and courage of a young graduate student, M. Furuse, had decided to take the classic route by homogenizing the most suitable tissue and enrich the desired structure by the most suitable techniques. The biological source was cleverly chosen—the bile canalicular front fraction from chicken liver, which is naturally enriched in all major kinds of junctions. Their first “eureka” candidate was a tetraspan transmembrane protein, which they could immunolocalize to the TJ structure, the zonula occludens, of liver and other simple epithelia, and so they named it “occludin” (Furuse et al. 1993; for the appropriate welcome ceremony, see Gumbiner 1993). Particularly satisfying was the result that on transfection of occludin-encoding cDNA expression constructs into TJ-possessing cells, the newly synthesized occludin integrated into pre-existing TJ structures, and when injected into TJ-lacking cells, the gene product was able to form de novo TJ-typical intramembranous “ridges” as well as cytoplasmic stacks of lamellae closely resembling typical TJ membrane structures (Furuse et al. 1994, 1996; Saitou et al. 1997). So, in a wide range of mammals, occludin and its various phosphorylation forms appeared to be the basis of TJ membranes (Fig. 4A) (Ando-Akatsuka et al. 1996; Sahakibara et al. 1997).

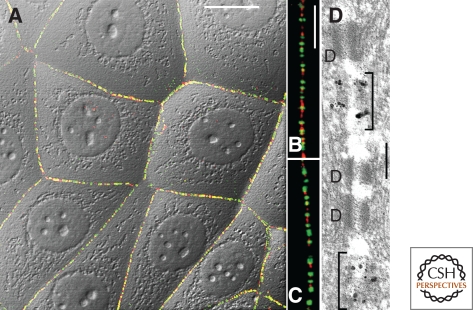

Figure 4.

Double-label immunofluorescence microscopy showing the tight junction (TJ) systems of monolayer cell cultures of human hepatocellular carcinoma-derived cells of line PLC (A) and of cultures of human keratinocytes of line HaCaT beginning to form the first suprabasal cell layer (B, C), using antibodies to keratin (A, green, mAb lu-5), in comparison with the TJ protein, occludin (A, red), or comparing the localization of the protein tricellulin (B, green, rat antibodies) with the TJ plaque protein, ZO-1 (B, red, rabbit antibodies), or the transmembrane TJ protein, occludin (C, red, rabbit antibodies). Note that these cells are totally interconnected by the TJ system (zonula occludens), which is completed at the tricellular corners by the occludin-related, but very specifically located protein, tricellulin, presenting complete colocalization with protein ZO-1 and occludin at the tricellular corners. For details, see also Schlüter et al. 2007. Bars: 20 µm.

Then, suddenly came a deep disappointment—not an uncommon one in modern biology, but in this case fortunately only a short one. Deletion of both alleles of the occludin gene had resulted in occludin-deficient mice, which, however, not only lived but formed typical TJ structures in the typical tissues, combined with plaque proteins of the ZO-1–3 protein family and TJ-typical functions (Saitou et al. 1998; only later, a series of occludin–/– mice with defects in several tissues and functions were reported: Saitou et al. 2000). Consequently, in their 1998 paper, Saitou et al. had to conclude: “These findings indicate that there are as yet unidentified TJ integral membrane protein(s) that can form strand structures, recruit ZO-1, and function as a barrier without occludin.” And so, without much mourning, they went back to square one, the chicken liver bile canalicular membrane fraction, and noticed two further bands of smaller (∼22 kDa) polypeptides that had amino acid sequences also indicative of molecules traversing the TJ membrane four times but without any occludin homology. Nevertheless, the new, very small, kind of protein immunolocalized to TJs, incorporated into TJs of living cells, and formed de novo intramembranous, TJ-typical ridge structures on cDNA transfection, even in TJ-lacking cells. Consequently, our Japanese friends had to expand their Latin vocabulary and named these new TJ proteins “claudins” nos. 1 and 2 (Furuse et al. 1998a,b; Tsukita and Furuse 1998).

But TJ life did not become much easier, and the ups and downs of TJ protein research emotions were not over. Japanese scientists are usually not regarded as hectic, but with the TJ proteins everything was new and different. Shoichiro (Tsukita) had just informed me and a few others about the first claudin amino acid sequence, but then came the stop-fax “hold it” and then the phone call “Sorry: Something strange has happened, these sequences are already in the computer.” Very quickly, however, his good mood returned with the solution: Two claudins were identical to the receptors of a food poisoning enterotoxin of the bacillus Clostridium perfringens, a known cause of gastrointestinal disease (Sonoda et al. 1999). Thus, another medical research path had just been opened: Claudins were recognized as membrane-bound receptors of certain toxins produced by prokaryotic pathogens (for a special review, see, e.g., Hecht 2001).

As we have already experienced with desmosomal molecules, and with cadherin and arm-protein constituents of the AJs, the claudins likewise did not come only as a pair of genes. To the contrary, the Tsukita group had stumbled into another large, novel gene family, the claudins, with very complex and functionally important, cell-type-specific combinations of a few selected representatives (e.g., Furuse et al. 1999; Morita et al. 1999a-c; Tsukita and Furuse 2000). And at the end of that year, coincidentally also the end of the millenium, already 15 different claudins had been discovered and soon thereafter a total number of 24 claudins were found to be encoded in the human genome (Tsukita et al. 2001; Tsukita and Furuse 2002). Some of the claudins came with a list of specific medical research questions, the first example being the Mg++-reabsorption problem protein, just called “paracellin,” now reclassified as claudin-16 (Simon et al. 1990; for a special review see Choate et al. 2001). Even higher claudin gene complexities are found in some other vertebrate species, with a—so far—record number of a total of 56 claudin genes in the—yes, no joke—Japanese puffer fish, Fugu rubripes (Loh et al. 2004; see there for further references). Thus, the smallest vertebrate genome known presents the highest claudin gene number known, an ironical paradox of Mother Nature. And while these sentences are written, a new claudin message comes in, indicating further bewildering complexity: Just one claudin, claudin-10, can occur in six spliced isoforms with different tissue and intracellular localizations and functions (Günzel et al. 2009). Evolution has indeed been merciless to cell biologists!

So the search for claudin functions in the different tissues and for claudin-connected diseases began. But halt once more! When the cell biological world thought that the TJ ensemble was finally complete, it turned out that not all essential facts of TJ structures had been carefully considered. Although complete TJs encircle individual cells of a simple, one-layered epithelium or an endothelium, thus forming a tight-looking barrier (Fig. 4A), in some epithelia, small intercellular “gaps” remain at places where three cells meet each other, a “three corner state” problem, representing gaps through which sizable molecules or even particles might translocate. Again, the Tsukita laboratory came through, identifying, as a very late addition to cell junction biology at the end of the year 2005, the protein “tricellulin,” just in time to let the late Shoichiro be sure about the publication (Ikenouchi et al. 2005). This protein, related by partial sequence homology to occludin, assembles exactly at those “three corner” sites to make the epithelial tight junction system really tight (Fig. 4B,C; Table 1).

In the meantime, systematic function-oriented studies had tried to elucidate the biological roles as well as the potential importance of specific claudins by gene mutation and deletion experiments. However, it was important to recognize that certain claudins occur in very specific cell types: For example, claudin-11, formerly known as “oligodendrocyte-specific protein” (OSP), was identified in cells as different as Sertoli cells of testis and myelin sheath-forming oligodendrocytes, biological distances and differences difficult to bridge by simple biological hypotheses (e.g., Morita et al. 1999b). The first systematic study of specific claudin gene deletion deficiencies brought both surprises and clarity. Claudin-1-deficient mice died on the first day after birth with wrinkled, dried-out skin, caused by massive transepidermal water loss (Furuse et al. 2002), a finding difficult to explain on the basis of the then prevailing textbook dogma that there are no TJ structures in the upper living layer (stratum granulosum) of the epidermis and other stratified epithelia. However, it was a lucky coincidence that in the summer of 2002, typical TJ structures, positive for claudins and occludin, had also been noted and localized in these uppermost layers of the epidermis and other squamous stratified epithelia (Fig. 5A–C) (Brandner et al. 2002; Furuse et al. 2002; Langbein et al. 2002; Schlüter et al. 2004; see also Morita et al. 1998, 2002; Pummi et al. 2001). These findings have changed the view of how the body surface is sealed from the outside world. Recently, tricellulin was also identified in suprabasal cell layers of keratinocyte cultures (Fig. 5B,C) (Schlüter et al. 2007).

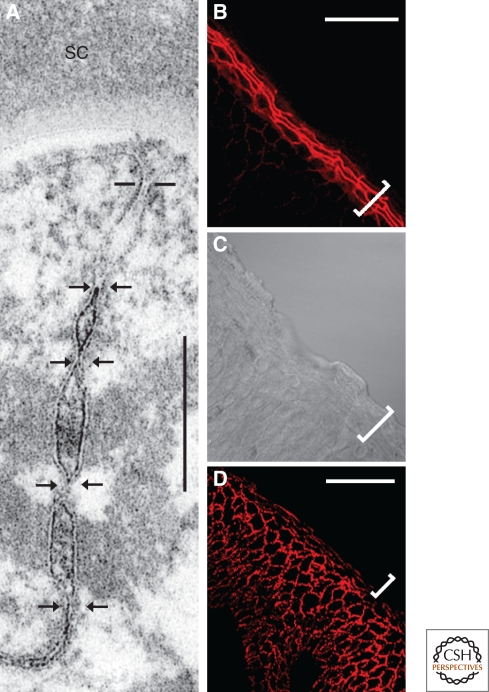

Figure 5.

Electron (A) and immunofluorescence (B–D) microscopy, showing the tight junction (TJ) system in the granular layer (stratum granulosum) of stratified epithelia. (A) The uppermost living layer of human epidermis (the first cornified layer, stratum corneum, is labeled SC) contains a subapical system of TJ structures (horizontal bars and pairs of arrows denote distinct membrane contact and fusion points: “kisses”). Note that the four lowermost TJs (arrows) are interspersed between desmosomes. (B–D) Near-vertical cryostat section through bovine gingiva, showing the TJ system in the uppermost living layers by immunostaining with antibodies to occludin (B, bracket; C, corresponding phase contrast image), whereas the cell–cell junction structures positive for the TJ protein, claudin-1, are not limited to the granular layer but extend basally into a number of stratum spinosum cell layers as well, indicating that there exist further, not yet fully characterized, partly punctate structures containing claudin-1 but not occludin (for methods used, see also Brandner et al. 2002; Schlüter et al. 2007).

Bars: 0.2 µm (A), 50 µm (B–D).

Here, the TJ story could end. There is, however, a remaining fundamental cell biological problem. TJ-type structures, appearing as “kisses” or other close membrane–membrane contacts, can also be seen in interdesmosomal regions of the spinous layer of the epidermis and the equivalent layers of several other stratified epithelia. They appear as small “lamellated” or “sandwich” junctions or even as “stud junctions” (puncta occludentia), exactly in places intensely immunopositive for occludin or certain claudins (Fig. 5B,C) (e.g., Brandner et al. 2002; Langbein et al. 2002, 2003; Schlüter et al. 2007). Could it be that there still exists a so far ignored world of TJ-related junctions? Could it be that discoveries of TJ molecule assemblies are not only history?

GAP JUNCTIONS: THE BEAUTY AND COMPLEXITY OF INTERCELLULAR CHANNELS

In the “good old,” although rather controversial days of molecular discoveries, cell biological discussions of possible functions of a given protein or structure started with educated guesses but often ended with less-educated, semitired jokelike comments. In the case of GJs, intercellular communication and exchange was one of the favorite discussion subjects early on, but non-GJ colleagues said that they were there “only to give pleasure to electron microscopists.” Indeed, these near-ubiquitous tissue structures seemed to have been precipitated out of an electron microscopist’s dreams as they comprised variously sized and shaped, densely packed, planar paracrystalline assemblies of short vertical hollow cylinders (“channels”) made up of symmetrically head-on-head contacting hemichannels. All of these structural details were well-demonstrable in the electron microscope, either in transverse or horizontal ultrathin sections, by freeze fractures (see, e.g., Fig. 1C) or in negatively stained isolated GJs. Thus, it was well known already in the 1960s that the hemichannel interior could be filled, at least partly, with heavy metal molecules but also that the small extracellular spaces in between the channels, the “gaps,” were also penetrable by such agents added from the outside. Moreover, in cell fractionation experiments, GJs were among the more stress-, detergent-, and even alkaline pH-resistant structures (e.g., Dewey and Barr 1964; Goodenough 1974; Henderson et al. 1979; Hertzberg and Gilula 1979; Hertzberg 1984; Stauffer et al. 1993). As a result of these near-optimal conditions, the ultrastructural organization of GJs was essentially known at the end of the 1970s (e.g., Goodenough and Revel 1970, 1971; McNutt and Weinstein 1970; Caspar et al. 1977; Unwin and Zampighi 1980; for reviews see, e.g., Loewenstein 1981; Gilula 1985, 1987, 1990; Revel et al. 1985, 1987; Unwin 1987; Goodenough 1990; Sosinsky 2000; see also Goodenough and Paul 2009). There was indeed no shortage of structural GJ models when the molecular phase began.

The major GJ proteins identified in fractions enriched in isolated junction structures from liver, heart, and eye lens were soon analyzed and characterized, including protein chemistry and reconstitution experiments, and cDNA cloning and sequencing (e.g., Goodenough 1974; Henderson et al. 1979; Hertzberg and Gilula 1979; Hertzberg et al. 1982; Hertzberg and Skibbens 1984; Kumar and Gilula 1986; Paul 1986; for review, see Goodenough 1990). A major protein constitutent was obvious, but it was also recognized early that the molecules representing this major GJ protein in different tissues were related but not identical. “Connexins” was chosen as the family name (Goodenough 1974) and, after some discussion on the molecular relatedness alphabetical nomenclature of the Westcoast and the “connexin plus apparent molecular weight” (e.g., Cx26, etc.) proposal from the Eastcoast, the “Cx plus Mr value” version found more friends. One inherent problem, however, was also noted from the beginning that the Mr value even of the ortholog protein could vary between species. Another problem was the same as encountered with the other cell–cell junctions. Yes, you are right: Connexins are another large junction protein family showing cell-type specificity.

Definitive evidence that a certain protein is indeed part of a GJ channel structure came when antibodies specific for a given type of connexin(s) had been generated. This enabled immunoblot testing for specific reactions with a connexin, or a few related ones, from GJ-enriched fractions, and the identification and exact GJ localization using immunoelectron and immunofluorescence microscopy with isolated gap junction membranes or, most convincing, GJ structures in situ (Willecke et al. 1982; Janssen-Timmen et al. 1983; Dermietzel et al. 1984; Paul 1985; Beyer et al. 1989; Fromaget et al. 1990, 1992, 1993; Gilula 1990; Yeager 1993). As with the transmembrane proteins of the other three major categories of junctions, antibodies that bound to certain epitopes located in the cell–cell bridge domains of connexins were also able to interfere with, or even disrupt, cell–cell coupling (e.g., Warner et al. 1984; Gilula 1990; Hertzberg et al. 1985).

In parallel, an increasing number of connexins had been characterized by cloning and sequencing, using cDNA clones from a wide variety of tissues (Kumar and Gilula 1986; Nicholson et al. 1985; Heynkes et al. 1986; Paul 1986; Beyer et al. 1987, 1990; Traub et al. 1989; Zhang and Nicholson 1989; Kanter et al. 1991; reviews: Beyer et al. 1993; Willecke et al. 1993; Yeager 1993). These studies led to an extremely complex cell-type-specific catalog of mammalian connexins. Twenty-one human Cx gene products have been identified so far, and so one has to recognize the great potential of Cx-type combinations to form GJs (homomeric, heteromeric, homotypic, or heterotypic), and further different properties that may result from phosphorylations and other modifications (reviews: Bruzzone et al. 1996; Goodenough et al. 1996; Kumar and Gilula 1996; Sosinsky 2000; see, e.g., the anthology edited by Peracchia 2000; for a special review integrating recent results and insights, see Goodenough and Paul 2009).

In view of the fundamentally different ultrastructural organization of the GJs, compared to the other three junctional complexes, and the obvious lack of homology between the connexins and the cadherins or claudins, it was finally some surprise, at least to this author, that connexin cytoplasmic domains also specifically associated with certain AJ-typical plaque proteins such as MAGUK proteins of the ZO-1 to ZO-3 group (Giepmans and Molenaar 1998; Toyofuku et al. 1998, 2001; Giepmans et al. 2001; Kausalya et al. 2001; Laing et al. 2001a,b; Nielsen et al. 2001, 2002, 2003; Barker et al. 2002; Jin et al. 2004; Singh et al. 2005; Talhouk et al. 2008). That this interaction reflects direct binding of the MAGUK protein to the connexin partner has perhaps most convincingly been shown using pure ZO-1 protein synthesized by translation in vitro (e.g., Laing et al. 2001a,b). So it is justified to hypothesize that MAGUK proteins are also important components involved in regulatory mechanisms of GJ formation and functions, and that the intracellular GJ membrane surface is a “hot spot” of interactions with diverse cytoplasmic proteins (Table 1) (review: Dbouk et al. 2009). The list of GJ-associated proteins and of interactions of GJs with other cell structures is still growing, although a distinct electron-dense plaque structure has not been demonstrated (for examples and references, see recent reviews: Park et al. 2007; Koval 2008; Prochnow and Dermietzel 2008).

The history of the elucidation of the molecular composition of GJs has been for some time under some strange clouds and question marks. For example, a radically alternative concept of GJ structures in various invertebrates and vertebrates was based on the existence of GJ-like structures assembled from very small (16–27 kDa) polypeptides, later named “ductins” (for references, see Finbow et al. 1985; Finbow and Pitts 1993; Finbow 1997; Ashrafi et al. 2000). Very recently, now such “GJ-mimicking” structures and the ductins could be definitively ascribed to proteins of the vacuolar ATPase proton pump and to be absent from GJs (M. Finbow, personal communication). Another long-standing question mark had already been answered at the turn of the millenium: The so-called major intrinsic polypeptides (MPs or MIPs) of the eye lens, one of the best studied structures in cell biology, were finally identified as true connexins (e.g., MP70 is Cx50; here, the reader is referred to “translations” of MP into Cx language as, e.g., in Graw et al. 2001).

In view of the important cell–cell comunication and exchange functions of GJs, it was expected that studies on the functions of specific GJs and GJ proteins would also bring valuable information about the functions of individual proteins, not only from gene deletion or mutation experiments but also from the growing list of human disorders and diseases that can be clearly related to mutant or disregulated connexins (for examples, see recent reviews: Meşe et al. 2007; Koval 2008). Thus, with connexins as with the constitutive molecules of the other three categories of cell–cell junctions, cell biologists can finally also conclude with satisfaction that basic cell research here has not only revealed the molecular organizations and functions of junction components, but has also made an unexpectedly high number of contributions to medical research and practice.

SOME CONCLUDING REMARKS

Although on a first glance the molecular ensembles and the morphology of the four homotypic cell–cell junctions differ in many aspects, one can also note a series of similarities in structural organization:

All four forms of symmetrical junctions are clusters of densely packed, specific transmembrane molecules.

The transmembrane molecules are either once-spanning glycoproteins (cadherins) or tetraspan proteins.

The cytoplasmically projecting domains of the transmembrane molecules are intimately associated with proteins that form layers or plaques, which widely vary in thickness and density and in certain cases can connect the junction with the cytoskeleton.

The transmembrane molecules of a hemi-junction are connected head-to-head with their counterparts of a hemi-junction of an adjacent cell.

The positions are often not at random but topogenically integrated into the specific cell and tissue architecture.

The types, the sizes, and the topological positions of these junctions are under developmental and functional control. Consequently, disorders often result in disease.

Footnotes

Editors: W. James Nelson and Elaine Fuchs

Additional Perspectives on Cell Junctions available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Aberle H, Schwartz H, Kemler R 1996. Cadherin-catenin complex: Protein interactions and their implications for cadherin function. J Cell Biochem 61:514–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghib DF, McCrea PD 1995. The E-cadherin complex contains the src substrate p120. Exp Cell Res 218:359–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aho S, Rothenberger K, Uitto J 1999. Human p120ctn catenin: Tissue-specific expression of isoforms and molecular interactions with BP180/type XVII collagen. J Cell Biochem 73:390–399 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amagai M 1999. Autoimmunity against desmosomal cadherins in pemphigus. J Dermatol Sci 20:92–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amagai M, Klaus-Kovtun V, Stanley JR 1991. Autoantibodies against a novel epithelial cadherin in pemphigus vulgaris, a disease of cell adhesion. Cell 67:869–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiadis PZ, Reynolds AB 2000. The 120 catenin family: Complex roles in adhesion, signaling and cancer. J Cell Sci 113:1319–1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiadis PZ, Moon SY, Thoreson MA, Mariner DJ, Crawford HC, Zheng Y, Reynolds AB 2000. Inhibition of RhoA by p120 catenin. Nat Cell Biol 2:637–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JM 1996. MAGUK magic. Curr Biol 6:326–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JM, Van Itallie CM 2009. Physiology and function of the tight junction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1:a002584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando-Akatsuka Y, Saitou M, Hirase T, Kishi M, Sakakibara A, Itoh M, Yonemura S, Furuse M, Tsujita Sh 1996. Interspecies diversity of the occludin sequence: cDNA cloning of human, mouse, dog, and rat-kangaroo homologues. J Cell Biol 133:43–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst BD, Marcozzi C, Magee AI 2001. The cadherin superfamily: Diversity in form and function. J Cell Sci 114:629–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnemann J, Sullivan KH, Magee AI, King IA, Buxton RS 1993. Stratification-related expression of isoforms of the desmosomal cadherins in human epidermis. J Cell Sci 104:741–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi GH, Pitts JD, Faccini AM, McLean P, O’Brien V, Finbow ME, Campo MS 2000. Binding of bovine papillomavirus type 4 E8 to ductin (16K proteolipid), down-regulation of gap junction intercellular communication and full cell transformation are independent events. J Gen Virol 81:689–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda MS, Matter K 2000. The tight junction protein ZO-1 and an interacting transcription factor regulate ErbB-2 expression. EMBO J 19:2024–2033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker RJ, Price RL, Gourdie RG 2002. Increased association of ZO-1 with connexin43 during remodeling of cardiac gap junctions. Circ Res 90:317–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzi H, Getz A, Mahoney MG, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Langbein L, Wahl KK III, Christiano AM 2006. Desmoglein 4 is expressed in highly differentiated keratinocytes and trichocytes in human epidermis and hair follicle. Differentiation 74:129–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens J, Birchmeier W, Goodman SL, Imhof BA 1985. Dissociation of Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells by the monoclonal antibody anti-arc-1: Mechanistic aspects and identification of the antigen as a component related to uvomorulin. J Cell Biol 101:1307–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens J, Mareel MM, Van Roy FM, Birchmeier W 1989. Dissecting tumour cell invasion: Epithelial cells acquire invasive properties after the loss of uvomorulin-mediated cell–cell adhesion. J Cell Biol 108:2435–2447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens J, Vakaet L, Friis R, Winterhager E, Van Roy F, Mareel MM, Birchmeier W 1993. Loss of epithelial morphotype and gain of invasiveness correlates with tyrosine phosphorylation of the E-cadherin/β-catenin complex in cells transformed with a temperature-sensitive v-src gene. J Cell Biol 120:757–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndorff D, Gessner R, Kreft B, Schnoy N, Lajous-Petter A-M, Loch N, Reutter W, Hortsch M, Tauber R 1994. Liver-intestine cadherin: Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel Ca2+-dependent cell adhesion molecule expressed in liver and intestine. J Cell Biol 125:1353–1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berx G, van Roy F 2009. Involvement of members of the cadherin superfamily in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1:a003129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer EC, Goodenough DA, Paul DL 1990. Connexin family of gap-junction proteins. J Membr Biol 116:187–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer EC, Paul DL, Goodenough DA 1987. Connexin43: A protein from rat heart homologous to a gap junction protein from liver. J Cell Biol 105:2621–2629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer EC, Kistler J, Paul DL, Goodenough DA 1989. Antisera directed against connexin43 peptides react with a 43-kD protein localized to gap junctions in myocardium and other tissues. J Cell Biol 108:595–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer EC, Kanter HL, Rup DM, Westphale EM, Reed KE, Larson DM, Saffitz JE 1993. Expression of multiple connexins by cells of the cardiovascular system and lens. Gap junctions (eds. Hall J.E., Zampighi G.A., Davis R.M.), Progr Cell Res. Vol. 3, pp. 171–175 Elsevier, Amsterdam [Google Scholar]

- Bierkamp C, McLaughlin KJ, Schwarz H, Huber O, Kemler R 1996. Embryonic heart and skin defects in mice lacking plakoglobin. Dev Biol 180:780–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchmeier W, Hülsken J, Behrens J 1995. E-cadherin as an invasion suppressor. Junctional complexes of epithelial cells, Ciba Found. Symp.125, pp. 124–141 J. Wiley and Sons, Chichester: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchmeier W, Weidner KM, Hülsken J, Behrens J 1993. Molecular mechanisms leading to cell junction (cadherin) deficiency in invasive carcinomas. Sem Cancer Biol 4:231–239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller K, Vestweber D, Kemler R 1985. Cell-adhesion molecule uvomorulin is localized in the intermediate junctions of adult intestinal epithelial cells. J Cell Biol 100:327–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonné S, van Hengel J, Nollet F, Kools P, van Roy F 1999. Plakophilin-3, a novel armadillo-like protein present in nuclei and desmosomes of epithelial cells. J Cell Sci 112:2265–2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonné S, Gilbert B, Hatzfeld M, Chen X, Green KJ, van Roy F 2003. Defining desmosomal plakophilin-3 interactions. J Cell Biol 161:403–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornslaeger EA, Corcoran CM, Stappenbeck TS, Green KJ 1996. Breaking the connection: Displacement of the desmosomal plaque protein desmoplakin from cell–cell interfaces disrupts anchorage of intermediate filament bundles and alters intercellular junction assembly. J Cell Biol 134:985–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrmann CM, Mertens C, Schmidt A, Langbein L, Kuhn C, Franke WW 2000. Molecular diversity of plaques of epithelial adhering junctions. Ann NY Acad Sci 915:144–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabletz T 2004. In vivo functions of catenins. Cell adhesion (eds. Behrens J., Nelson W.J.), Handbook Exp. Pharmacol., Vol. 165, pp. 105–135 Springer, Berlin: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandner JM, Kief S, Grund C, Rendl M, Houdek P, Kuhn C, Tschachler E, Franke WW, Moll I 2002. Organization and formation of the tight junction-system in human epidermis and cultured keratinocytes. Eur J Cell Biol 81:253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher A 1986. Purification of the intestinal microvillus cytoskeletal proteins villin, fimbrin, and ezrin. Meth Enzymol 134:24–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill S, Li S, Lyman CW, Church DM, Wasmuth JJ, Weissbach L, Bernards A, Snijders AJ 1996. The Ras GTPase-activating-protein-related human protein IQGAP2 harbors a potential actin binding domain and interacts with calmodulin and Rho family GTPases. Mol Cell Biol 16:4869–4878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R, White TW, Paul DL 1996. Connections with connexins: The molecular basis of direct intercellular signalling. Eur J Biochem 238:1–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussemakers MJG, van Bokhoven A, Mees SGM, Kemler R, Schalken JA 1993. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human E-cadherin cDNA. Mol Biol Rep 17:123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton RS, Magee AI 1992. Structure and interactions of desmosomal and other cadherins. Semin Cell Biol 3:157–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton RS, Cowin P, Franke WW, Garrod DR, Green KJ, King IA, Koch PJ, Magee AI, Rees DA, Stanley JR, et al. 1993. Nomenclature of the desmosomal cadherins. J Cell Biol 121:481–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM, Peifer M 2009. Wnt signaling from development to disease: insights from model systems. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1:a002881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RD, Campbell JH 1971. Origin and continuity of desmosomes. Origin and continuity of cell organelles (eds. Reinert J., Ursprung H.), pp. 261–298 Springer Verlag, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- Caspar D, Goodenough D, Makowski L, Phillips W 1977. Gap junction structures. I. Correlated electron microscopy and x-ray diffraction. J Cell Biol 74:605–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereijido M, Anderson J (eds.) 2001. Tight Junctions 2. edn CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Bonné S, Hatzfeld M, van Roy F, Green KJ 2002. Protein binding and functional characterization of plakophilin 2. J Biol Chem 277:10512–10522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitaev NA, Troyanovsky SM 1997. Direct Ca2+-dependent heterophilic interaction between desmosomal cadherins, desmoglein and desmocollin, contributes to cell–cell adhesion. J Cell Biol 138:193–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitaev NA, Leube RE, Troyanovsky RB, Eshkind LG, Franke WW, Troyanovsky SM 1996. The binding of plakoglobin to desmosomal cadherins: Patterns of binding sites and topogenic potential. J Cell Biol 133:359–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choate KA, Lu Y, Lifton RP 2001. Claudins mediate specific paracellular fluxes in vivo: Paracellin-1 is required for paracellular Mg2+ flux. Tight junctions (eds. Cereijido M., Anderson J.), pp. 483–492 CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- Choi H-J, Weis WI 2004. Structural aspects of adherens junctions and desmosomes. In Cell adhesion (eds. Behrens J., Nelson W.J.), Handbook Exp. Pharmacol., Vol. 165, pp. 23–52 Springer, Berlin: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citi S 2001. The cytoplasmic plaque proteins of the tight junction. Tight junctions (eds. Cereijido M., Anderson J.), pp. 231–264 CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- Citi S, Sabanay H, Jakes R, Geiger B, Kendrick-Jones J 1988. Cingulin, a new peripheral component of tight junctions. Nature 333:272–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citi S, Sabanay H, Kendrick-Jones J, Geiger B 1989. Cingulin: Characterization and localization. J Cell Sci 93:107–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citi S, Amorosi A, Franconi F, Giotti A, Zampi G 1991. Cingulin, a specific protein component of tight junctions, is expressed in normal and neoplastic human epithelial tissues. Am J Pathol 138:781–789 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claude P 1978. Morphological factors influencing transepithelial permeability: A model for the resistance of the zonula occludens. J Membr Biol 10:219–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claude P, Goodenough DA 1973. Fracture faces of zonulae occludentes from “tight” and “leaky” epithelia. J Cell Biol 58:390–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM, Gorbsky GJ, Steinberg MS 1983. Immunochemical characterization of related families of glycoproteins in desmosomes. J Biol Chem 258:2621–2627 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colaco CALS, Evans WH 1981. A biochemical dissection of the cardiac intercalated disk: Isolation of subcellular fractions containing fascia adherentes and gap junctions. J Cell Sci 52:313–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JE, Legan PK, Kenny TP, MacGarvie J, Holton JL, Garrod DR 1991. Cloning and sequence analysis of desmosomal glycoproteins 2 and 3 (desmocollins): Cadherin-like desmosomal adhesion molecules with heterogeneous cytoplasmic domains. J Cell Biol 113:381–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordenonsi M, D’Atri F, Hammar E, Parry DA, Kendrick-Jones J, Shore D, Citi S 1999. Cingulin contains globular and coiled-coil doamins and interacts with ZO-1, ZO-2, ZO-3, and myosin. J Cell Biol 147:1569–1582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin P, Garrod DR 1983. Antibodies to epithelial desmosomes show wide tissue and species cross-reactivity. Nature 302:148–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin P, Kapprell H-P, Franke WW 1985b. The complement of desmosomal plaque proteins in different cell types. J Cell Biol 101:1442–1454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin P, Mattey DM, Garrod DR 1984a. Distribution of desmosomal components in the tissues of vertebrates, studied by fluorescent antibody staining. J Cell Sci 66:119–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin P, Mattey DM, Garrod DR 1984b. Identification of desmosomal surface components (desmocollins) and inhibition of desmosome formation by specific Fab. J Cell Sci 70:41–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin P, Franke WW, Grund C, Kapprell HP, Kartenbeck J 1985a. The desmosome-intermediate filament complex. In The cell in contact (eds. Edelman G.M., Thiery J.-P.), pp. 427–460 John Wiley and Sons, New York [Google Scholar]

- Cowin P, Kapprell H-P, Franke WW, Tamkun J, Hynes RO 1986. Plakoglobin: A protein common to different kinds of intercellular adhering junctions. Cell 46:1063–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham BA 1985. Structures of cell adhesion molecules. In The cell in contact (eds. Edelman G.M., Thiery J.-P.), pp. 197–217 John Wiley and Sons, New York [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham BA, Leutzinger Y, Gallin WJ, Forkin BC, Edelman GM 1984. Linear organization of the liver cell adhesion molecule L-CAM. Proc Natl Acad Sci 81:5787–5791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsky CH, Richa J, Solter D, Knudsen K, Buck CA 1983. Identification and purification of a cell surface glycoprotein mediating intercellular adhesion in embryonic and adult tissue. Cell 34:455–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]