Abstract

To better understand light regulation of C4 plant maize development, we investigated dynamic proteomic differences between green seedlings (control), etiolated seedlings, and etiolated seedlings illuminated for 6 or 12 h using a label-free quantitative proteomics approach based on nanoscale ultraperformance liquid chromatography-ESI-MSE. Among more than 400 proteins identified, 73 were significantly altered during etiolated maize seedling greening. Of these 73 proteins, 25 were identified as membrane proteins that seldom had been identified with two-dimensional electrophoresis methods, indicating the power of our label-free method for membrane protein identification; 31 were related to light reactions of chlorophyll biosynthesis, photosynthesis, and photosynthetic carbon assimilation. The expression of photosystem II subunits was highly sensitive to light; most of them were not identified in etiolated maize seedlings but drastically increased upon light exposure, indicating that the complex process of biogenesis of the photosynthetic apparatus correlates with the transition from a dark-grown to a light-grown morphology. However, transcriptional analysis indicated that most transcripts encoding these proteins were not regulated by light. In contrast, the levels of mRNAs and proteins for enzymes involved in carbon assimilation were tightly regulated by light. Additionally phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, the key enzyme of the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase C4 pathway, was more tightly regulated by light than the key enzymes of the NADP-malic enzyme C4 pathway. Furthermore phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase 1C, which was originally reported to be specifically expressed in roots, was also identified in this study; expression of this enzyme was more sensitive to light than its isoforms. Taken together, these results represent a comprehensive dynamic protein profile and light-regulated network of C4 plants for etiolated seedling greening and provide a basis for further study of the mechanism of gene function and regulation in light-induced development of C4 plants.

Light is not only the energy resource for all green plants but also an essential environmental regulatory signal that influences diverse aspects of plant growth and development, such as seed germination, gravitropism, phototropism, chloroplast development, shade avoidance, circadian rhythms, and flowering time (1, 2). Light-induced greening of angiosperms often has been used as the model to study mechanisms of light regulation (3, 4). Both dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous dark-grown seedlings present typical etiolated characters of elongated hypocotyls and stems as well as undifferentiated chloroplast precursors (3–5). Upon exposure to light, seedlings undergo a number of dramatic changes, including a substantial reduction in the rate of elongation, opening of the apical hook, expansion of true leaves, and development of mature chloroplasts (5, 6). The transition from etiolated to de-etiolated seedlings is a very complicated process that includes chloroplast development, pigment synthesis, and assembly of the photosystems in thylakoids, all of which are accomplished by and depend on the differential expression of a large number of genes (4). Phytochromes play an important role in regulating de-etiolation (7–9), and certain photosynthesis-related genes also can be regulated by light; for example, the genes encoding chlorophyll a/b-binding light-harvesting proteins are down-regulated by excess light exposure (10), and the gene encoding Rieske FeS protein (10) and genes GAPA and GAPB, which encode different subunits of chloroplast glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (11) in Arabidopsis, are up-regulated by light. It has been estimated that the expression of at least 1000 plant genes is controlled by light (12–14). However, sometimes these transcriptional changes do not directly reflect changes in the levels of the encoded proteins. Therefore, an investigation is necessary, and thus this important aspect must be investigated via systemic proteomics.

In the past decade, proteome analysis has been most commonly accomplished by the combination of two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE)1 and MS. This method has identified 25 light-induced proteins in Arabidopsis (3) and 52 in rice (4) during the de-etiolating process. Further differential accumulation of Lhcb proteins in thylakoid membranes of maize plants grown under contrasting light and temperature conditions was also analyzed (15). However, 2-DE suffers from certain drawbacks that primarily arise from ambiguity in the identification of multiple proteins present in a single spot, identification of proteins at both extremes of the pI range, small proteins, natural variants and fragments resulting from in-gel degradation, and variation in extraction efficiency (16). As a complementary alternative, LC-MS-based relative quantification methods have emerged to identify and quantify peptides and proteins in mixtures of varying complexity. In the majority of these techniques, stable isotopes are introduced into the sample; such methods include ICAT (17), isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) (18), in vivo stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) (19), and 18O labeling (20, 21). Although these approaches potentially provide the greatest accuracy, isotopic labeling has disadvantages such as relative high cost, procedural complexity, and the potential danger for artifacts. As such, these techniques have not been used extensively in plant proteomics studies.

Recently label-free LC-MS quantification methods have been described to determine relative abundance of proteins in different samples (22–28). As with isotopic labeling, these methods are based on the measurement and comparison of the MS signal intensities of peptide precursor ions. This method has been problematic for quantitative proteomics analysis because of the low reproducibility of nano-LC runs and the requirement for MS to MS/MS switching to obtain sequence information, resulting in low quality chromatograms (29). The development of ultraperformance LC (UPLC) (30, 31), however, has greatly increased thereproducibility. The level of reproducibility in nano-UPLC allows quantitative assessment of changes between samples with high precision but without the need for stable isotope-based techniques in particular when combined with low/high collision energy MS (MSE) analysis (16, 23, 32, 33). MSE-based data acquisition permits one to collect sufficient data points in low collision mode to quantify peak ion intensities and, at the same time, obtain fragmentation data in high collision mode for protein identification. The development of MSE has allowed the collection of 5–10 times more precursor ions and fragmentation data as compared with data-dependent acquisition modes (33). As such, the newly developed label-free method has sufficient sensitivity and reproducibility to meet the requirements of stability of intensity, mass measurement, and retention time for label-free quantitative LC-MS measurements. Moreover label-free LC-MS methods allow the estimation of absolute protein concentrations that can be used for stoichiometry studies (23, 32).

The present study describes a method based on nano-UPLC coupled with MSE-based label-free quantitative shotgun proteomics to qualitatively and quantitatively assess the transition from dark to light of maize seedlings. Although many proteomics investigations have been done on light-regulated proteins in C3 plants during seedling de-etiolation, particularly in rice and Arabidopsis (3, 4), few such studies have been done in C4 plants. Maize, which is quite distinct from Arabidopsis and rice, is a prototypical C4 plant that exhibits classical Kranz leaf anatomy during development (34, 35). In Kranz anatomy, each vein is surrounded by a ring of bundle sheath cells followed by one or more concentric rings of mesophyll cells. Each cell type accumulates a distinct set of C4 photosynthetic enzymes (36, 37). Both gel-based and non-gel-based techniques have shown that proteins differentially accumulate in chloroplasts in bundle sheath cells and mesophyll cells, resulting in a model for C4 photosynthesis (38, 39). Undoubtedly these investigations will become a cornerstone for further work on C4 photosynthesis and differentiation. Based on these reports, we performed a comparative proteomics study on maize seedlings during the transition from dark to light using a label-free method. The proteomic changes illustrated in this study exactly reflect the dynamic changes in the protein expression pattern associated with de-etiolation of maize seedlings. Transcriptional patterns of genes encoding proteins whose levels changed drastically during maize seedling de-etiolation were also analyzed by quantitative real time RT-PCR (QRT-PCR). The correlation between mRNA abundance and protein accumulation revealed different light-regulating mechanisms for these proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant Material and Treatment

Seeds of Zea mays L. ecotype B73 were used in this study. After imbibition for 24 h, the maize seeds were divided into two groups and cultured under different illumination conditions at 28 °C for 1 week. One group was grown with a normal light regime (12-h light/12-h darkness) as control seedlings, and another was grown in darkness as experimental seedlings. The 7-day-old etiolated seedlings (termed “0 h”) were exposed to white light (100 mmol of photons/m2 s) and illuminated for 6 h (termed “6 h”) or 12 h (termed “12 h”). The 7-day-old green seedlings were harvested after 12 h of continuous illumination (termed “control”).

Chlorophyll Extraction and Calculation

Fresh leaf slices (0.2 g) were immersed in 15 ml of 95% ethanol, which was generally sufficient to completely extract chlorophyll for 12 h at room temperature in complete darkness (light-impermeable box). Debris in the extract were separated by filtration through filter paper, and the debris were rinsed with 95% ethanol several times to completely extract residual chlorophyll. The clear filtrate was transferred to a brown volumetric flask, and the final volume was brought to 25 ml with 95% ethanol. After thorough mixing, 2 ml of filtrate of each sample was taken, and the absorbance was measured at 665 and 649 nm using a spectrophotometer. Total chlorophyll content (chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b) was calculated using the following equations: Chlorophyll a = 13.95A665 − 6.88A649; Chlorophyll b = 24.96A649 − 7.32A665. Chlorophyll content in each sample was determined based on three absorbance measurements.

Protein Extraction

Leaves harvested after being illuminated for various periods were ground in liquid nitrogen. The powder was precipitated in a 10% (w/v) TCA, acetone solution containing 0.07% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol at −20 °C for 2 h. After centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 1 h, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was rinsed with −20 °C acetone containing 0.07% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol. The final pellet was vacuum-dried and solubilized in 3 ml of 7 m (w/v) urea containing 2 m (w/v) thiourea, 40 mm DTT, 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), 0.2 mm Na2VO3, and 1 mm NaF on ice for about 1 h. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h. The protein concentration was determined using the 2-D Quant kit (GE Healthcare) with BSA as a standard. Samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for further experiments.

Protein Digestion

Protein digestion was performed as described previously (40). After adjusting the pH to 8.5 with 1 m ammonium bicarbonate, total protein extracted from each sample was chemically reduced for 45 min at 55 °C by adding DTT to 10 mm and carboxyamidomethylated in 55 mm iodoacetamide for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Then CaCl2 was added to 20 mm, endoprotease Lys-C (Roche Applied Science) was added to a final substrate/enzyme ratio of 100:1 (w/w), and the reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 12 h. The Lys-C digest was diluted to 1 m urea with 100 mm ammonium bicarbonate, and modified trypsin (Roche Applied Science) was added to a final substrate/enzyme ratio of 50:1 (w/w). The trypsin digest was incubated at 37 °C for 12 h. After digestion, the peptide mixture was acidified by 10 μl of formic acid for further MS analysis. Samples not immediately analyzed were stored at −80 °C.

Analysis by Nano-UPLC-MSE Tandem MS

Nanoscale LC separation of peptides digested by Lys-C and trypsin was performed with a nanoACQUITY system (Waters) equipped with a Symmetry C18 5-μm, 180-μm × 20-mm precolumn and a ethylene bridged hybrid (BEH) C18 1.7-μm, 75-μm × 250-mm, analytical reversed-phase column (Waters). The samples were initially transferred with an aqueous 0.1% formic acid solution to the precolumn at a flow rate of 7 μl/min for 3 min. Mobile phase A was water with 0.1% formic acid, and mobile phase B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. The peptides were separated with a linear gradient of 3–40% mobile phase B over 90 min at 200 nl/min followed by 10 min at 90% mobile phase B. The column was re-equilibrated at initial conditions for 20 min. The column temperature was maintained at 35 °C. The lock mass was delivered from the auxiliary pump of the nanoACQUITY pump with a constant flow rate of 300 nl/min at a concentration of 100 fmol/μl [Glu1]fibrinopeptide B. All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Analysis of tryptic peptides was performed using a SYNAPT high definition mass spectrometer (Waters). For all measurements, the mass spectrometer was operated in the v-mode with a typical resolving power of at least 10,000 full-width half-maximum. The TOF analyzer of the mass spectrometer was calibrated with the MS/MS fragment ions of [Glu1]fibrinopeptide B from m/z 50 to 1600. The reference sprayer was sampled with a frequency of 30 s. Accurate mass LC-MS data were collected in high definition MSE mode (low collision energy, 4 eV; high collision energy, ramping from 15 to 45 eV; switching every 1.0 s; interscan time, 0.02 s) (24, 33). The mass range was from m/z 300 to 1990. To confirm optimal column loading, all proteins present were quantified by comparison with 100 fmol of rabbit glycogen phosphorylase trypsin digest spiked into the sample using the Hi3 quantification method (22).

Data Processing and Protein Identification

Continuum LC-MS data were processed and searched using ProteinLynx GlobalServer version 2.3 (PLGS 2.3) (Waters). Raw data sets were processed including ion detection, deisotoping, deconvolution, and peak lists generated based on the assignment of precursor ions and fragments based on similar retention times. The principles of the applied data clustering and normalization have been explained previously in great detail (22, 24). Components are typically clustered together with a <10-ppm mass precision and a <0.25-min time tolerance. Alignment of elevated energy ions with low energy precursor peptide ions was conducted with an approximate precision of ±0.05 min.

A downloaded NCBI maize database (released in July 2008; 11,653 sequences; 3,295,141 residues) was used to search each triplicate run with the following parameters: peptide tolerance and fragment tolerance, automatic (usually 10 ppm for peptide tolerance and 20 ppm for fragment tolerance); trypsin missed cleavages, 1; fixed modification, carbamidomethylation of cysteine; variable modifications, N-terminal acetylation, deamidation of asparagine and glutamine, and oxidation of methionine. The database search algorithm was described in detail in a newly published study (41). Rabbit glycogen phosphorylase was appended to the database as an internal standard. The protein identifications were based on the detection of at least three fragment ions per peptide with more then two peptides identified per protein. A maximum false positive rate of 4% was allowed.

Quantitative Analysis

The analysis of quantitative changes in protein abundance, which is based on measuring peptide ion peak intensities observed in low collision energy mode in a triplicate set, was carried out using Waters ExpressionE, which is part of PLGS 2.3. For protein quantification, data sets were normalized using the PLGS “autonormalization” function. In this type of normalization routine the data are normalized to the intensity of the many qualitatively matched proteins (or peptides) whose abundances do not change between conditions as established by statistical analysis. Included limits were all protein hits that were identified with a confidence of >95%. Identical peptides from each triplicate set per sample were clustered based on mass precision (typically ∼5 ppm) and a retention time tolerance of <0.25 min using clustering software included in PLGS 2.3. Only those proteins identified in at least two of three injections and having -fold changes >1.3 were regarded as having undergone a significant change. All proteins whose abundances were significantly different between samples were manually assessed by checking the matched peptide and replication level across samples.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein samples were prepared as described above and subjected to Western blot analysis. The samples (50 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE (12.5% gel) at 100 V for 2 h. Gels were then equilibrated for 20 min in transfer buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 192 mm glycine, and 20% methanol) and then transferred to a PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare; the membrane was presoaked for 10 s in methanol and then equilibrated for 20 min in transfer buffer) at 200 mA for 2 h. Each PVDF membrane was blocked overnight with 0.5% BSA in TBS-T (20 mm Tris, 500 mm NaCl, and 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20), washed three times for 15 min each with TBS-T, and then incubated with a specific primary antibody (anti-Lhcb1 (LHCP) or anti-Lhcb6 (CP29); Agrisera, Vännäs, Sweden) in TBS-T with gentle shaking at room temperature for 1 h. Each membrane was washed three times for 15 min each with TBS-T and then incubated with the secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG) in TBS-T with gentle shaking at room temperature for 1 h. Each membrane was rinsed three times for 20 min each with TBS-T and developed with the SuperEnhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Applygen Technologies Inc., Beijing, China), and immunoreactive bands were visualized after exposure of the membranes to FUJIFILM medical x-ray film.

Quantitative Real Time RT-PCR

Maize seedlings illuminated for different periods (0, 6, and 12 h and control) were harvested. Total RNA was extracted with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed with a PrimeScript RT Reagent kit (TaKaRa, Otsu, Shiga, Japan) according to the respective manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative real time PCR assays were performed in triplicate with the DNA Engine Opticon 2 System (MJ Research) using actin and tubulin (GenBank™ accession numbers X97726 and AJ420859) as internal standards. Diluted aliquots of the reverse transcribed cDNAs were used as templates in quantitative PCRs containing the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix Plus (Applied Biosystems). Primers of the assayed genes and internal standard genes are listed in supplemental Table S1. PCR cycling conditions comprised an initial activation step of the DNA polymerase at 94 °C for 30 s followed by 45 cycles of 94 °C for 12 s, 58 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 40 s, 79 °C for 1 s, and a step of plate reading. Triplicate reactions were carried out for each sample to ensure reproducibility. Negative controls lacked template DNA but contained gene-specific primer pairs, and the no RT-PCR controls were set up in duplicate using primers for the actin and tubulin genes. At the end of each PCR program, a melting curve was generated and analyzed with Dissociation Curves Software (Opticon Monitor 2, MJ Research). PCR product lengths were verified by agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm the specificity of PCR products. Gene expression was quantified using the comparative cycle treshold (CT) method (42).

RESULTS

Morphological and Chlorophyll Changes during Etiolated Maize Seedling Greening

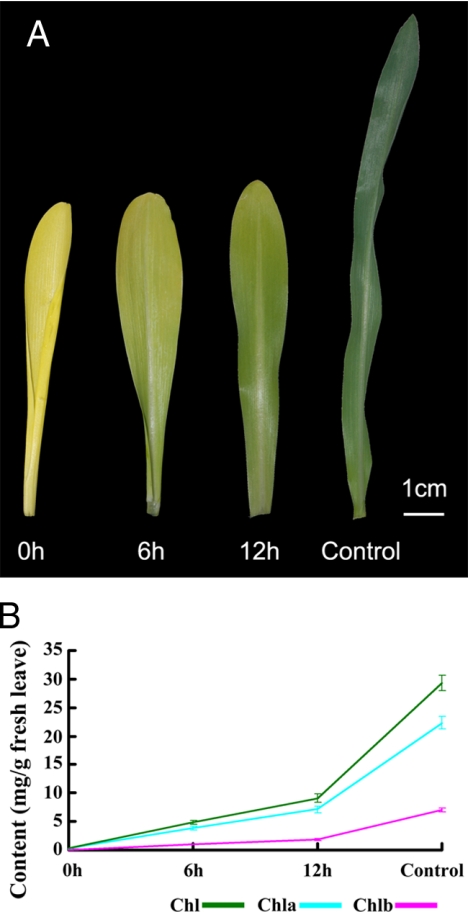

Maize seeds were cultured in the dark and light, respectively, from seed germination. Compared with green seedlings (control), the leaves of 7-day-old etiolated seedlings (0 h) were light yellow and gradually turned green only after they were exposed to light for 6 or 12 h (Fig. 1A). Chlorophyll content under different lighting conditions was carefully assayed; it was barely detectable in etiolated maize seedlings but rapidly rose to 5 mg/g of dry weight (6-h illumination) and 10 mg/g (12-h illumination) and even reached 30 mg/g in control seedlings. Although chlorophyll content increased in control seedlings and in etiolated seedlings after 6 or 12 h of illumination (Fig. 1B), the chlorophyll a/chlorophyll b ratio remained fairly constant (about 3.4).

Fig. 1.

Maize leaves during de-etiolation. A, representative leaves from the various treatment groups: 0 h, not exposed to light; 6 h, exposed to light for 6 h; 12 h, exposed to light for 12 h; control, continuously exposed to light. B, chlorophyll (Chl) content of etiolated maize leaves after exposure to light for 6 or 12 h and of control leaves. Data for each sample represent the mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments.

Data Quality Evaluation

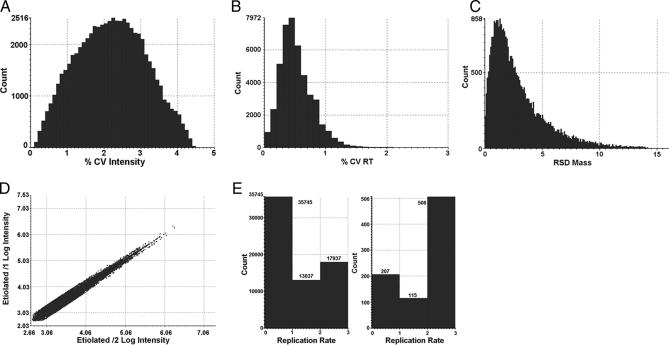

Before conducting the relative protein profiling analysis among the four conditions, a variety of quality control measures were performed on the replicates of each condition to determine analytical reproducibility. Data quality assessment of the final results was performed with the protein expression software PLGS 2.3 (Waters) using a clustering algorithm for accurate mass and retention time (AMRT) data and database search (identified proteins) results analysis. The mass precision of the extracted peptide components was typically within 5 ppm. In the present study, taking 0 h as an example, the median and average mass errors were 2.20 and 3.00 ppm, respectively; the median and average intensity errors were 2.40 and 2.25%, respectively; and the median and average retention time was 0.50 and 0.58%, respectively (Fig.2, A–C). Other samples gave similar results as shown in supplemental Fig. S1 A–C

Fig. 2.

Assessment of the analytical reproducibility. A, error distribution associated with the intensity measurements for the 30,974 replicating AMRT clusters detected in the 0-h sample. The median and average intensity errors were ±2.40 and ±2.25%, respectively. B, relative standard deviation (RSD) of the 30,974 replicating AMRT clusters detected in the 0-h sample. The median and average retention time (RT) errors were 0.50 and 0.58%, respectively. C, error distribution associated with the mass accuracy for the 30,974 replicating AMRT clusters (in at least two of three injections) detected in the 0-h sample. The median and average mass errors were ±2.20 and ±3.00 ppm, respectively. D, log intensity AMRT clusters for injection 1 versus log intensity AMRT clusters for injection 2 of one of the investigated conditions (0-h sample); 38,681 clusters were detected in both injections. E, the availability of triplicate data sets provides information about the data quality, such as replicate rates between repeated runs (left panel) and the confidence and reproducibility of protein identification (right panel). Under these conditions, 17,937 AMRT clusters were detected in all three runs, 13,037 were detected in two of three repeats, and 35,745 were detected in one replicate, representing low abundance peaks. In total, 66,719 clusters were detected in the 0-h sample. Under these conditions, 506 proteins were identified in all three runs (triplicates) and are therefore of high confidence, 115 proteins were assigned in two of three repeats and are therefore of intermediate confidence, and 207 proteins were identified in one replicate, representing low confidence hits. Similar profiles were observed for the other three samples (supplemental Fig. S1) CV, coefficient of variation.

A binary comparison of the peptide precursor intensity measurements of two injections of one sample from the investigated conditions (0 h) is presented in Fig. 2D. A 45° diagonal line was obtained with almost no variation throughout the detection range. As reported previously (23), this example demonstrates the expected distribution in the instance of no obvious change between the investigated injections. These types of quality control measurements were performed on all injections and conditions, and very similar diagonal lines were obtained for all conditions (supplemental Fig. S1D).

The availability of triplicate data sets can also provide information about data quality, such as AMRT reproducibility between replicate analyses and the confidence of protein identification. This assessment determines how many ions are in common between analytical replicates. The replication rate plots extracted from PLGS for 0 h are shown in Fig. 2E. Under these conditions, AMRT clusters observed in more than two runs were 46.4, 48.4, 44.3, and 46.0% for 0-, 6-, and 12-h illumination and control group, respectively, and proteins identified in more than two runs accounted for 75.0, 69.4, 75.2, and 73.0% of all proteins identified for 0-, 6-, and 12-h illumination and control group, respectively. The numbers of proteins identified in all three runs (triplicates) were 506 (0 h), 500 (6 h), 498 (12 h), and 434 (control), accounting for 81.5, 85.3, 83.6, and 76.5%, respectively, of proteins identified in more than two runs. Therefore, these proteins were identified with high confidence (supplemental Fig. S1E).

The data for all four samples appeared to be reproducible in terms of mass accuracy, retention time, and intensity. This emphasizes the required stability of intensity, mass measurement, and retention time for label-free quantitative LC-MS measurements. These observations are within typical error measurements (22) in which careful scrutiny was given to accurate mass and retention time clustering, data normalization, and quantification.

Relative Quantification

Prior to making quantitative comparisons between conditions, the observed intensity measurements were normalized using the PLGS autonormalization function. It has been reported that data set normalization performed based on a spiked standard yields results very similar to those obtained using the PLGS autonormalization function (33). In this study, the internal standard was used to optimize and normalize the loading amount. Details on protein identification and quantification are described under “Experimental Procedures.” Expression analysis (relative quantification processed by PLGS software) yielded the relative -fold change of all identified proteins for the four investigated conditions. The significance of regulation level was specified at 30%. Hence 1.3-fold (±0.30 natural log scale) change was used as a threshold to identify significantly up- or down-regulated expression; this is typically 2–3 times the estimated error of the intensity measurement. All protein hits that were identified with a confidence of >95% and observed in more than two runs were regarded as positive up- or down-regulated proteins. In total, 73 non-redundant differentially expressed proteins were identified in the four different light treatments (Table I) of which 56 proteins were detected in all four treatments. Six proteins were not identified in the 0-h condition but were identified in the 6- and 12-h conditions and control; four were not identified in control but were identified in 0-, 6-, and 12-h conditions; five were only identified in the 12-h condition and control; one was only identified in control; and one was only identified in the 0-h condition. The unique identified peptide number and sequence coverage of each protein in each sample and each run are listed in supplemental Table S2. The peptide sequence, [M + H]+ of identified peptide, PLGS score, retention time, intensity, matched fragment ion, and other relative information for all of these 73 significant changed proteins are listed in supplemental Tables S3–S14 for 12 runs of the four samples. The replicate level data profiles of 31 representative proteins that are involved in photosynthesis are shown in supplemental Fig. S3.

Table I . Differentially expressed proteins during de-etiolated maize seedling greening analyzed by LC-MSE.

| Accession no. | Protein name | NPIa |

Coverage |

Score | Protein expression ratio |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 6 h | 12 h | Cb | 0 h | 6 h | 12 h | C | 6 h/0 h | 12 h/0 h | 6 h/12 h | C/0 h | C/6 h | C/12 h | |||

| % | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 Photosynthesis (31) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1.1 Chlorophyll synthesis (3) | ||||||||||||||||

| CAD99008.1 | POR | 18 | 19 | 12 | 11 | 64.15 | 78.17 | 47.98 | 56.6 | 882.02 | 0.52 ± 0.13 | 0.40 ± 0.17 | 1.28 ± 0.13 | 0.23 ± 0.19 | 0.45 ± 0.18 | 0.58 ± 0.18 |

| AAZ14053.1 | Magnesium chelatase subunit I | 9 | 11 | 13 | 10 | 47.23 | 47.95 | 47.47 | 45.3 | 708.61 | 1.57 ± 0.16 | 1.15 ± 0.16 | 1.36 ± 0.14 | 1.08 ± 0.19 | 0.69 ± 0.16 | 0.94 ± 0.16 |

| ABB77211.1 | Plastid coproporphyrinogen-III oxidase | 6 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 52.75 | 42.75 | 40.5 | 41.25 | 277.91 | 1.54 ± 0.44 | 1.40 ± 0.44 | 1.09 ± 0.39 | 0.97 ± 0.57 | 0.63 ± 0.49 | 0.69 ± 0.45 |

| 1.2 Light reaction (17) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1.2.1 Photosystem II (11) | ||||||||||||||||

| P12329.1 | LHCP (Lhcb1) | 4 | 6 | 6 | 48.09 | 57.63 | 32.44 | 544.20 | 6 h | 12 h | 0.18 ± 0.27 | C | 6.55 ± 0.33 | 1.19 ± 0.23 | ||

| CAA37474.1 | LHCP (Cab-m7) | 5 | 2 | 4 | 53.96 | 38.49 | 47.17 | 475.78 | 6 h | 12 h | 0.35 ± 0.47 | C | 4.39 ± 0.46 | 1.55 ± 0.32 | ||

| CAM55603.1 | CP24 | 7 | 5 | 44.35 | 31.05 | 216.15 | 12 h | 12 h | C | C | 1.45 ± 0.26 | |||||

| AAA64415.1 | CP26 | 7 | 6 | 46.29 | 48.76 | 331.21 | 12 h | 12 h | C | C | 1.49 ± 0.28 | |||||

| CAM55524.1 | CP29 (Lhcb6) | 4 | 5 | 18.84 | 25 | 209.91 | 12 h | 12 h | C | C | 2.10 ± 0.42 | |||||

| NP_001105228.1 | PsbS | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 29.43 | 26.79 | 39.25 | 38.49 | 308.61 | 1.51 ± 0.37 | 3.32 ± 0.31 | 0.46 ± 0.27 | 1.82 ± 0.40 | 1.20 ± 0.29 | 0.55 ± 0.27 |

| AAA20823.1 | OEE3 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 52.07 | 35.94 | 43.78 | 46.08 | 528.29 | 0.80 ± 0.21 | 1.27 ± 0.17 | 0.63 ± 0.17 | 2.72 ± 0.18 | 3.39 ± 0.17 | 2.14 ± 0.14 |

| CAA81421.1 | OEE3 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 51.64 | 50.23 | 54.46 | 50.23 | 382.95 | 0.92 ± 0.22 | 1.45 ± 0.20 | 0.64 ± 0.22 | 3.42 ± 0.16 | 3.67 ± 0.20 | 2.34 ± 0.17 |

| AAN33184.1 | Photosystem II D1 protein | 3 | 2 | 11.61 | 11.61 | 226.26 | 12 h | 12 h | C | C | 1.93 ± 0.31 | |||||

| P48184.1 | Photosystem II D2 protein | 5 | 3 | 21.25 | 12.46 | 261.87 | 12 h | 12 h | C | C | 2.16 ± 0.16 | |||||

| ABQ53629.1 | Plastid high chlorophyll fluorescence 136 | 15 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 59.14 | 48.48 | 49.24 | 59.9 | 385.58 | 1.02 ± 0.34 | 1.42 ± 0.24 | 0.72 ± 0.33 | 1.08 ± 0.35 | 1.06 ± 0.45 | 0.76 ± 0.34 |

| 1.2.2 Photosystem I (1) | ||||||||||||||||

| CAM55476.1 | PSI type III chlorophyll a/b-binding protein | 6 | 6 | 7 | 44.64 | 44.64 | 53.57 | 635.00 | 6 h | 12 h | 0.26 ± 0.41 | C | 5.99 ± 0.38 | 1.54 ± 0.18 | ||

| 1.2.3 Photosynthetic electron transfer (2) | ||||||||||||||||

| NP_043037.1 | Apocytochromef | 7 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 44.69 | 43.75 | 43.75 | 31.88 | 426.76 | 0.70 ± 0.24 | 1.19 ± 0.18 | 0.59 ± 0.18 | 1.35 ± 0.19 | 1.93 ± 0.20 | 1.14 ± 0.14 |

| NP_001104851.1 | Ferredoxin- NADP reductase | 7 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 37.5 | 36.96 | 43.48 | 48.1 | 520.14 | 1.36 ± 0.29 | 1.60 ± 0.28 | 0.85 ± 0.20 | 2.89 ± 0.27 | 2.12 ± 0.18 | 1.80 ± 0.16 |

| 1.2.4 ATP synthase (3) | ||||||||||||||||

| P05022.1 | ATP synthase subunit α | 11 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 33.73 | 40.04 | 36.49 | 42.41 | 1862.17 | 1.09 ± 0.08 | 1.39 ± 0.08 | 0.79 ± 0.07 | 1.95 ± 0.07 | 1.79 ± 0.07 | 1.40 ± 0.07 |

| NP_043032.1 | ATP synthase subunit β | 21 | 21 | 26 | 23 | 69.28 | 67.87 | 78.51 | 70.28 | 2737.21 | 1.01 ± 0.06 | 1.20 ± 0.06 | 0.84 ± 0.05 | 1.97 ± 0.06 | 1.97 ± 0.05 | 1.65 ± 0.05 |

| P0C1M0.1 | ATP synthase subunit γ | 7 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 40.11 | 42.9 | 29.53 | 48.19 | 244.72 | 1.43 ± 0.46 | 1.39 ± 0.39 | 1.03 ± 0.31 | 2.36 ± 0.42 | 1.65 ± 0.26 | 1.70 ± 0.25 |

| 1.3 Carbon dioxide fixation (11) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1.3.1 Calvin cycle (5) | ||||||||||||||||

| NP_043033.1 | Rubisco large subunit | 17 | 15 | 9 | 17 | 42.44 | 43.28 | 27.52 | 43.28 | 1015.16 | 2.64 ± 0.15 | 1.55 ± 0.12 | 1.70 ± 0.10 | 2.34 ± 0.11 | 0.89 ± 0.10 | 1.51 ± 0.07 |

| CAA70416.1 | Rubisco small subunit | 5 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 63.53 | 61.76 | 57.65 | 64.12 | 279.87 | 5.37 ± 0.22 | 1.67 ± 0.27 | 3.25 ± 0.19 | 6.69 ± 0.22 | 1.25 ± 0.12 | 4.01 ± 0.18 |

| CAA33455.1 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase A | 7 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 35.73 | 60.05 | 32.51 | 36.97 | 932.70 | 1.75 ± 0.14 | 1.92 ± 0.17 | 0.91 ± 0.09 | 2.53 ± 0.17 | 1.45 ± 0.08 | 1.32 ± 0.10 |

| AAC97932.3 | Rubisco activase | 11 | 15 | 11 | 16 | 54.04 | 54.97 | 47.81 | 60.74 | 776.33 | 1.27 ± 0.14 | 1.34 ± 0.13 | 0.94 ± 0.11 | 1.93 ± 0.14 | 1.52 ± 0.11 | 1.45 ± 0.09 |

| AAM51721.1 | Phosphoglycerate kinase | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 33.56 | 29.87 | 34.23 | 29.19 | 318.59 | 1.36 ± 0.20 | 1.06 ± 0.22 | 1.28 ± 0.23 | 1.46 ± 0.18 | 1.07 ± 0.21 | 1.39 ± 0.19 |

| 1.3.2 C4 cycle (6) | ||||||||||||||||

| AAA86945.1 | Carbonic anhydrase | 5 | 11 | 14 | 17 | 44.63 | 38.28 | 36.6 | 42.88 | 485.50 | 2.72 ± 0.45 | 4.95 ± 0.39 | 0.55 ± 0.18 | 7.03 ± 0.38 | 2.56 ± 0.18 | 1.40 ± 0.14 |

| AAP33011.1 | Malic enzyme | 16 | 20 | 15 | 16 | 35.85 | 48.43 | 40.25 | 48.27 | 432.93 | 1.92 ± 0.23 | 2.20 ± 0.23 | 0.87 ± 0.15 | 2.94 ± 0.21 | 1.54 ± 0.16 | 1.34 ± 0.13 |

| CAA33316.1 | PEPC 1 | 21 | 23 | 28 | 31 | 29.18 | 34.12 | 37.53 | 41.13 | 1589.3 | 1.63 ± 0.15 | 2.16 ± 0.14 | 0.76 ± 0.07 | 2.18 ± 0.14 | 1.34 ± 0.06 | 1.01 ± 0.06 |

| NP_001105503.1 | PEPC 1C | 9 | 9 | 7 | 25.94 | 28.02 | 20.63 | 664.06 | 6 h | 12 h | 0.57 ± 0.28 | C | 2.29 ± 0.25 | 1.32 ± 0.18 | ||

| Q9SLZ0.1 | PEPCK | 9 | 13 | 17 | 30.78 | 35.29 | 39.34 | 887.66 | 6 h | 12 h | 0.64 ± 0.27 | C | 2.69 ± 0.27 | 1.73 ± 0.22 | ||

| AAA33498.1 | Pyruvate, phosphate dikinase 1 | 22 | 32 | 25 | 32 | 49.1 | 61.25 | 51.74 | 61.25 | 2951.50 | 1.38 ± 0.06 | 1.60 ± 0.06 | 0.86 ± 0.06 | 2.48 ± 0.05 | 1.80 ± 0.07 | 1.55 ± 0.04 |

| 2 Glycolysis (6) | ||||||||||||||||

| CAA83914.1 | Phosphoglyceromutase | 12 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 43.83 | 40.97 | 32.74 | 35.42 | 418.80 | 0.99 ± 0.25 | 0.93 ± 0.25 | 1.06 ± 0.25 | 0.67 ± 0.31 | 0.68 ± 0.38 | 0.72 ± 0.35 |

| AAC50048.1 | Phosphoglucomutase | 13 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 42.54 | 34.82 | 27.1 | 31.56 | 470.27 | 1.11 ± 0.27 | 1.19 ± 0.27 | 0.93 ± 0.27 | 0.83 ± 0.34 | 0.75 ± 0.35 | 0.7 ± 0.31 |

| P26301.1 | Enolase 1 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 12 | 37.89 | 43.05 | 43.5 | 39.01 | 730.50 | 0.88 ± 0.21 | 0.88 ± 0.16 | 1.00 ± 0.21 | 0.68 ± 0.22 | 0.77 ± 0.18 | 0.77 ± 0.22 |

| AAA87578.1 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 10 | 11 | 8 | 8 | 52.23 | 56.08 | 48.07 | 44.51 | 1917.46 | 0.60 ± 0.08 | 0.72 ± 0.09 | 0.84 ± 0.08 | 0.49 ± 0.10 | 0.82 ± 0.09 | 0.68 ± 0.08 |

| CAA53075.1 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (NADP+) | 9 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 38.55 | 27.51 | 34.94 | 31.73 | 327.53 | 1.42 ± 0.42 | 1.40 ± 0.37 | 1.01 ± 0.46 | 1.60 ± 0.38 | 1.13 ± 0.41 | 1.14 ± 0.28 |

| BAA00009.1 | Triose-phosphate isomerase | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 50.99 | 55.34 | 54.94 | 49.41 | 423.82 | 0.79 ± 0.30 | 0.83 ± 0.24 | 0.96 ± 0.24 | 0.70 ± 0.30 | 0.88 ± 0.34 | 0.84 ± 0.37 |

| 3 Gluconeogenesis/glyoxylate cycle (5) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1604473A | Malate dehydrogenase (NADP) | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 40.28 | 42.13 | 38.89 | 40.28 | 924.61 | 1.09 ± 0.20 | 1.25 ± 0.18 | 0.88 ± 0.20 | 1.88 ± 0.14 | 1.72 ± 0.19 | 1.51 ± 0.14 |

| Q08062.2 | Malate dehydrogenase | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 40.66 | 34.04 | 40.06 | 33.13 | 630.25 | 1.02 ± 0.17 | 0.80 ± 0.17 | 1.27 ± 0.18 | 0.68 ± 0.15 | 0.66 ± 0.19 | 0.84 ± 0.18 |

| CAM55515.1 | β-d-Glucosidase precursor (glu2) | 12 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 38.72 | 33.04 | 41.03 | 36.77 | 884.50 | 1.26 ± 0.13 | 0.91 ± 0.14 | 1.36 ± 0.11 | 0.85 ± 0.13 | 0.68 ± 0.13 | 0.92 ± 0.13 |

| P49036.1 | Sucrose synthase 2 | 12 | 17 | 16 | 11 | 28.06 | 33.95 | 31.37 | 21.57 | 840.47 | 1.27 ± 0.14 | 1.23 ± 0.17 | 1.03 ± 0.16 | 0.34 ± 0.22 | 0.27 ± 0.19 | 0.28 ± 0.22 |

| Q6XZ78.1 | Fructokinase 2 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 45.97 | 48.96 | 34.93 | 34.03 | 472.92 | 1.25 ± 0.20 | 1.16 ± 0.20 | 1.07 ± 0.17 | 0.44 ± 0.24 | 0.35 ± 0.26 | 0.38 ± 0.19 |

| 4 Mitochondrial electron transport/ATP synthesis (4) | ||||||||||||||||

| P19023.1 | ATP synthase subunit β | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 56.42 | 55.88 | 58.77 | 55.7 | 2051.46 | 0.84 ± 0.09 | 0.83 ± 0.10 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 0.63 ± 0.10 | 0.75 ± 0.10 | 0.75 ± 0.10 |

| AAA80346.1 | V-ATPase subunit A | 14 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 52.23 | 46.52 | 40.29 | 45.81 | 612.15 | 1.22 ± 0.22 | 0.87 ± 0.21 | 1.00 ± 0.11 | 1.08 ± 0.23 | 0.89 ± 0.26 | 1.23 ± 0.23 |

| AAA92464.1 | Thioredoxin M-type | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 35.33 | 35.33 | 28.74 | 35.33 | 358.66 | 1.22 ± 0.35 | 1.01 ± 0.23 | 1.00 ± 0.12 | 1.36 ± 0.22 | 1.12 ± 0.33 | 1.35 ± 0.18 |

| P12857.2 | ADP/ATP translocase 2 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 36.95 | 28.94 | 48.84 | 25.06 | 311.3 | 1.16 ± 0.33 | 0.82 ± 0.40 | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 0.81 ± 0.34 | 0.70 ± 0.30 | 0.99 ± 0.34 |

| 5 Redox regulation (2) | ||||||||||||||||

| AAG43988.1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | 7 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 21.68 | 31.88 | 31.69 | 37.7 | 332.13 | 1.35 ± 0.34 | 1.07 ± 0.35 | 1.26 ± 0.36 | 1.09 ± 0.43 | 0.80 ± 0.31 | 1.01 ± 0.43 |

| AAC37357.1 | Catalase isozyme 3 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 38.31 | 28.83 | 19.76 | 471.39 | 0.72 ± 0.22 | 0.61 ± 0.32 | 1.19 ± 0.34 | 0 h | 6 h | 12 h | ||

| 6 Protein (9) | ||||||||||||||||

| 6.1 Protein biosynthesis (5) | ||||||||||||||||

| NP_001105396.1 | eIF-4A | 6 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 30.19 | 29.95 | 24.88 | 34.3 | 545.44 | 1.72 ± 0.32 | 1.42 ± 0.40 | 1.22 ± 0.34 | 1.03 ± 0.38 | 0.59 ± 0.36 | 0.73 ± 0.39 |

| AAF42979.1 | EF 1-α | 4 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 23.04 | 27.74 | 15.21 | 19.69 | 386.08 | 1.52 ± 0.25 | 1.22 ± 0.49 | 1.25 ± 0.34 | 0.74 ± 0.31 | 0.49 ± 0.21 | 0.61 ± 0.34 |

| NP_043060.1 | 50 S ribosomal protein L14 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 52.85 | 47.15 | 48.78 | 47.97 | 158.10 | 1.79 ± 0.44 | 1.72 ± 0.44 | 1.04 ± 0.25 | 1.38 ± 0.43 | 0.77 ± 0.27 | 0.80 ± 0.27 |

| NP_001105104.1 | Translationally controlled tumor protein homolog | 9 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 81.44 | 45.51 | 46.11 | 79.04 | 366.56 | 1.17 ± 0.42 | 1.46 ± 0.32 | 0.81 ± 0.32 | 0.98 ± 0.41 | 0.83 ± 0.36 | 0.67 ± 0.31 |

| CAN08528.1 | Putative ribosomal protein S3a | 6 | 4 | 7 | 36 | 34.33 | 35.67 | 396.41 | 0.85 ± 0.34 | 1.20 ± 0.27 | 0.72 ± 0.25 | 0 h | 6 h | 12 h | ||

| 6.2 Protein folding, assembly, and fate (4) | ||||||||||||||||

| AAA92743.1 | Luminal binding protein 2 | 11 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 34.98 | 29.63 | 29.22 | 33.95 | 784.86 | 1.26 ± 0.22 | 1.46 ± 0.21 | 0.85 ± 0.16 | 0.97 ± 0.27 | 0.77 ± 0.20 | 0.66 ± 0.20 |

| CAA48638.1 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | 7 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 55.23 | 34.88 | 34.3 | 34.3 | 577.35 | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 0.80 ± 0.15 | 1.12 ± 0.20 | 0.62 ± 0.18 | 0.70 ± 0.19 | 0.78 ± 0.22 |

| AAT90346.1 | Rubisco subunit binding-protein β subunit | 16 | 14 | 14 | 11 | 66.26 | 53.3 | 60.88 | 63.08 | 615.89 | 1.02 ± 0.15 | 1.21 ± 0.14 | 0.85 ± 0.13 | 0.45 ± 0.19 | 0.44 ± 0.17 | 0.37 ± 0.13 |

| P11143.1 | Heat shock 70-kDa protein | 14 | 17 | 14 | 15 | 47.75 | 37.52 | 49.15 | 41.4 | 1045.52 | 1.04 ± 0.11 | 1.16 ± 0.10 | 0.90 ± 0.11 | 0.71 ± 0.13 | 0.68 ± 0.12 | 0.61 ± 0.13 |

| 7 Lipid metabolism (1) | ||||||||||||||||

| CAA80822.1 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase | 14 | 24 | 25 | 24 | 32.8 | 28.74 | 38.58 | 32.74 | 863.23 | 1.3 ± 0.37 | 0.93 ± 0.34 | 1.39 ± 0.31 | 0.76 ± 0.33 | 0.58 ± 0.33 | 0.81 ± 0.32 |

| 8 Amino acid metabolism (4) | ||||||||||||||||

| AAL33589.1 | Methionine synthase | 23 | 26 | 27 | 23 | 52.74 | 57.44 | 62.53 | 51.17 | 930.27 | 1.22 ± 0.14 | 1.6 ± 0.14 | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 0.76 ± 0.17 | 0.62 ± 0.15 | 0.47 ± 0.15 |

| NP_001105813.1 | Anthranilate synthase α subunit | 12 | 12 | 10 | 44.37 | 39.57 | 36.59 | 291.73 | 0.98 ± 0.66 | 1.63 ± 0.51 | 0.60 ± 0.48 | 0 h | 6 h | 12 h | ||

| AAL40137.1 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase | 16 | 13 | 12 | 9 | 47.23 | 41.54 | 34.99 | 39.54 | 523.46 | 1.77 ± 0.28 | 1.67 ± 0.31 | 1.07 ± 0.20 | 0.76 ± 0.46 | 0.43 ± 0.40 | 0.45 ± 0.41 |

| AAV64199.1 | Putative alanine aminotransferase | 7 | 46.51 | 291.73 | 0 h | 0 h | 0 h | |||||||||

| 9 Hormone metabolism (2) | ||||||||||||||||

| CAP12267.1 | Lipoxygenase (LOX6) | 21 | 18 | 20 | 14 | 33.52 | 32.96 | 37.56 | 29.93 | 1153.90 | 0.52 ± 0.18 | 0.49 ± 0.19 | 1.07 ± 0.21 | 0.55 ± 0.17 | 1.06 ± 0.19 | 1.14 ± 0.21 |

| ABF01002.1 | Lipoxygenase (LOX11) | 21 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 43.03 | 28.76 | 18.99 | 19.54 | 679.45 | 0.84 ± 0.29 | 0.71 ± 0.25 | 1.16 ± 0.21 | 0.72 ± 0.30 | 0.86 ± 0.20 | 1.00 ± 0.23 |

| 10 Cofactor and vitamin metabolism (1) | ||||||||||||||||

| AAA96738.1 | Thiazole biosynthetic enzyme 1-1 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 41.53 | 29.66 | 54.52 | 296.10 | 2.01 ± 0.43 | 5.05 ± 0.32 | 0.40 ± 0.25 | 0 h | 6 h | 12 h | ||

| 11 Nucleotide metabolism (1) | ||||||||||||||||

| CAB40376.1 | Adenosine kinase | 11 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 70.39 | 71.6 | 59.52 | 58.01 | 511.00 | 1.46 ± 0.41 | 1.17 ± 0.38 | 1.25 ± 0.29 | 1.23 ± 0.40 | 0.84 ± 0.36 | 1.05 ± 0.33 |

| 12 Structural proteins (4) | ||||||||||||||||

| AAB86960.1 | Profilin-4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 32.06 | 51.15 | 51.15 | 51.91 | 251.02 | 0.79 ± 0.30 | 1.04 ± 0.30 | 0.76 ± 0.25 | 0.68 ± 0.34 | 0.86 ± 0.33 | 0.65 ± 0.35 |

| CAN08626.1 | Tubulin β-5 chain | 14 | 14 | 10 | 8 | 52.35 | 46.37 | 46.37 | 29.7 | 1168.23 | 1.28 ± 0.13 | 1.07 ± 0.13 | 1.20 ± 0.14 | 0.38 ± 0.24 | 0.29 ± 0.21 | 0.35 ± 0.24 |

| AAB40104.1 | Actin | 10 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 55.95 | 60.42 | 46.73 | 58.63 | 654.72 | 1.32 ± 0.16 | 1.13 ± 0.14 | 1.19 ± 0.17 | 0.74 ± 0.15 | 0.55 ± 0.16 | 0.66 ± 0.20 |

| AAB49896.1 | UPTGc | 6 | 9 | 6 | 39.84 | 39.29 | 46.7 | 381.70 | 6 h | 12 h | 2.36 ± 0.38 | C | 0.41 ± 0.36 | 0.96 ± 0.10 | ||

| 13 Miscellaneous (3) | ||||||||||||||||

| CAB38118.1 | Glutathione transferase IIIb | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 45.7 | 40.27 | 41.63 | 38.46 | 263.97 | 0.71 ± 0.30 | 0.65 ± 0.28 | 1.09 ± 0.32 | 0.44 ± 0.31 | 0.62 ± 0.38 | 0.68 ± 0.34 |

| AAL57037.1 | UDP-glucosyltransferasec BX8 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 15 | 37.25 | 49.24 | 39.65 | 40.52 | 315.62 | 1.07 ± 0.31 | 0.75 ± 0.43 | 1.43 ± 0.38 | 0.78 ± 0.37 | 0.73 ± 0.38 | 1.04 ± 0.45 |

| AAT70082.1 | Hydroxymethylbutenyl 4-diphosphate synthase | 8 | 10 | 11 | 7 | 24.93 | 23.73 | 23.32 | 31.23 | 433.55 | 0.83 ± 0.37 | 1.01 ± 0.37 | 0.82 ± 0.37 | 0.74 ± 0.42 | 0.90 ± 0.44 | 0.73 ± 0.42 |

a NPI, number of peptides identified. Because each experiment was run in triplicate, each protein, therefore, was identified triply. The median (or the second largest number) number of the three NPIs is displayed in this table.

b C, control.

cUPTG, UDP, glucose: protein transglucosylase.

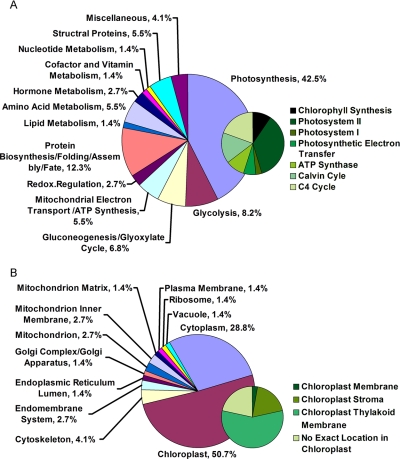

Differential Protein Classification

The identified proteins were further classified based on (i) gene product subcellular localization and (ii) biological process of each gene product according to annotations in the Swiss-Prot database and Plant Proteome Database. For proteins lacking exact functional and localization annotations in these databases, we used Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) alignment of the identified GenBank accession numbers to the non-redundant protein sequence database at NCBI to reveal annotations of their homologs (Table I and supplemental Table S2). Finally all of these identified proteins were classified into 13 functional groups (Fig.3A) localized to 12 cellular components (Fig. 3B and supplemental Table S2), which covered a wide range of pathways and functions. The identified proteins localize mainly in chloroplasts (51%), including thylakoid membranes (28.8%), stroma (9.6%), chloroplast membrane (1.4%), and the proteins with no exact localized annotation in chloroplast (11.0%) (Fig. 3B). The presence of a large number of chloroplast proteins is consistent with the fact that during the transformation from etioplast to fully developed chloroplast the protein repertoire of chloroplasts changes dramatically. This change in protein repertoire reflects differences in different biological processes of photosynthesis and carbon assimilation, and the change includes enzymes participating in chlorophyll biosynthesis, the Calvin cycle, and the C4 pathway and subunits of photosystem I (PSI) and PSII (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Functional classification and distribution (A) and protein locations (B) of all 73 identified and quantified proteins. Unknown proteins include those whose functions have not been described but can be deduced based on analysis of amino acid sequence homology as listed in Table I.

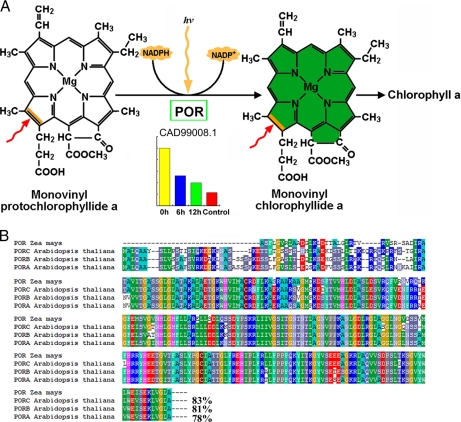

NADPH-protochlorophyllide Oxidoreductase (POR) Is Drastically Down-regulated during the Transition from Dark to Light

We identified and quantified three maize enzymes involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis, namely POR, coproporphyrinogen-III oxidase, and magnesium chelatase subunit I. POR catalyzes the only light-dependent reaction in the chlorophyll biosynthetic pathway and is hence intimately involved in the greening of angiosperms (43). Interestingly POR expression is high in etiolated seedlings (0 h) but drastically lower in seedlings exposed to light (Fig. 4A). The expression ratios were 0.54, 0.4, and 0.23 for 6 h/0 h, 12 h/0 h, and control/0 h, respectively (Table I), suggesting that this protein is negatively regulated by light (Fig. 4A). Sequence comparison indicated that maize POR shares 83% similarity to Arabidopsis PORC, 81% to Arabidopsis PORB, and 78% to PORA (Fig. 4B). This high degree of sequence similarity between the two species suggests a conserved and ancestral function for this maize POR. Coproporphyrinogen-III oxidase is an enzyme of the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis pathway catalyzing the oxidative decarboxylation of coproporphyrinogen III to protoporphyrinogen IX, the precursor for both chlorophyll and heme biosynthesis (44), and magnesium chelatase catalyzes the first committed step in chlorophyll biosynthesis, insertion of Mg2+ into protoporphyrinogen IX (45, 46). However, these two proteins differ from POR in that they were nearly equally expressed in both 0 h and control, and their expression only modestly increased after exposure to light, reaching a maximum after 6 h of illumination (Table I).

Fig. 4.

POR expression profile during etiolated maize seedling greening and amino acid sequence comparison with Arabidopsis homologs. A, POR catalyzes the only light-dependent reaction of chlorophyll synthesis, whereas the level of POR drastically decreases during etiolated seedling greening. B, amino acid sequence alignment indicating that maize POR shares similarities of 83% with Arabidopsis PORC, 81% with PORB, and 78% with PORA.

Expression of Components of the Photosynthetic Apparatus Changes Most Dramatically in Response to Light

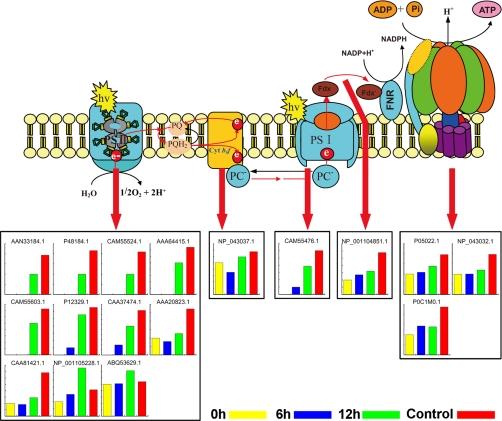

Light-dependent reactions in plants take place on the thylakoid membrane inside chloroplasts. There are four major protein complexes in the thylakoid membrane, namely PSI, PSII, cytochrome b6f complex, and ATP synthase, that work together to produce ATP and NADPH. We identified and quantified 17 proteins involved in photosynthetic electron transport in the thylakoid membrane, including 11 subunits of PSII, one subunit of cytochrome b6f complex (apocytochrome f), one subunit of PSI, ferredoxin-NADP reductase, and three subunits of ATP synthase (Fig.5 and Table I). PSII is a large multisubunit pigment protein complex in which light energy is captured by the peripheral antenna and is transferred to the core complex where it is trapped. The peripheral antennas are composed of major trimeric and minor monomeric light-harvesting complex II (LHCII) proteins (47). The LHCs are encoded by nuclear genes, their mRNAs are translated in the cytosol, and their products are then post-translationally directed to chloroplasts where they associate with pigments and insert into the thylakoid membrane (48). In this research, three LHCII minor proteins (CP24, CP26, and CP29) and two core subunits (D1 and D2) were identified and quantified only in 12 h and control; a major LHCII protein and Lhcb1, a light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding protein (CAA37474.1), were identified in the light-treated seedlings (6 and 12 h and control) but not in 0-h seedlings. All these proteins increased in abundance with increased illumination time. In addition, the level of PSII subunit PsbS, which plays an essential role in the dissipation of excess energy during photosynthesis, also increased after exposure to light. These results suggested that the expression or accumulation of these PSII proteins strongly depends on light. Similar to the components of PSII, a PSI subunit, PSI type III chlorophyll a/b-binding protein, was also strongly induced by light (Fig. 5 and Table I). PSI type III chlorophyll a/b-binding protein was not expressed in 0-h seedlings, and its level increased, however, after longer exposure to light (12 h and control) (Table I).

Fig. 5.

Significant changed proteins involved in the photosynthetic electron transport chain of the thylakoid membrane. These proteins include 11 subunits of PSII, a subunit of cytochrome (Cyt) b6f complex, one subunit of PSI, ferredoxin (Fdx)-NADP reductase, and three subunits of ATP synthase. The Swiss-Prot database accession numbers correspond to those listed in Table I. PQ, plastoquinone; PQH2, plastoquinol. hv, luminous energy; FNR, Fd-NADP+ reductase; PC, plastocyanin.

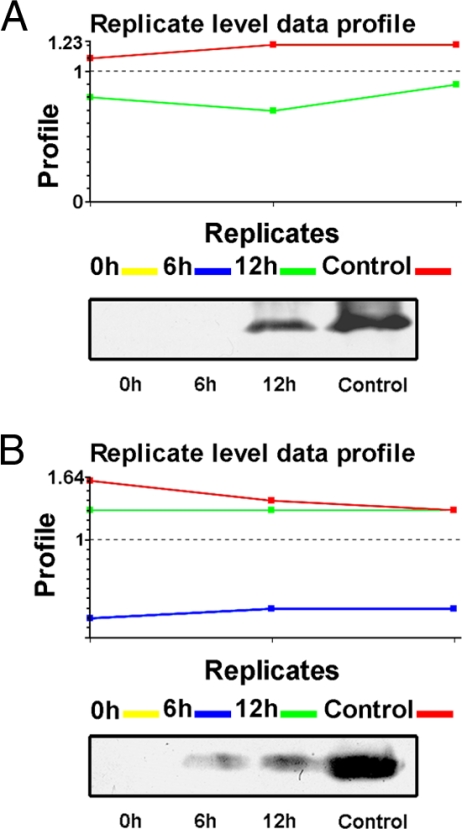

To confirm the label-free quantitative results, Western blot was performed to compare expression of leaf proteins of maize seedlings under different illumination conditions. Fig.6 presents the replicated level data by MS and the results of using antibodies against Lhcb1 and CP29 (Lhcb6). Lhcb1 was not identified in 0-h seedlings using our label-free method, but its level increased dramatically after exposure to light (6 and 12 h and control) (Fig. 6, A and B, upper panels); Lhcb6 was only expressed in 12-h and control seedlings. Western blot results for both proteins agreed well with the quantification of the label-free method (Fig. 6, A and B, lower panels).

Fig. 6.

Replicate level data profiles. A, profile of Lhcb1. Upper panel, each sample was analyzed in triplicate with LC-MSE. Lhcb1 was only detected in 12-h (green line) and control (red line) seedlings, and the amount is higher in control (red line). Lower panel, Western blot analysis showing the same results. B, replicate level data profile of CP29. Upper panel, each sample was analyzed in triplicate. CP29 (Lhcb6) was not detected in 0-h (yellow line) seedlings but was detected in 6-h (blue line), 12-h (green line), and control (red line) seedlings. CP29 was of low abundance at 6 h but increased dramatically in the 12-h and control samples. Lower panel, Western blot analysis showing the same results.

The Expression of Key Enzymes Involved in Carbon Fixation Strongly Depends on Light

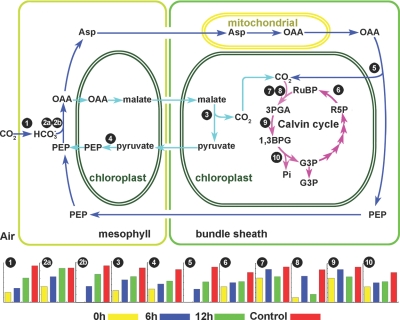

Although maize has been traditionally recognized as a classical NADP-ME subtype C4 plant, accumulating evidence indicates that it also has another complementary PEPCK decarboxylating C4 pathway (49–51). Here we identified and quantified 11 key enzymes involved in both the C4 pathway and Calvin cycle. Fig.7, a modified version of a figure from a previous study (51), shows changes in the levels of proteins involved in the carbon assimilation pathway during greening of etiolated maize seedlings. The first enzymatic step in C4 photosynthesis is the reversible hydration reaction catalyzed by carbonic anhydrase, which converts CO2 to HCO3− in the mesophyll cytoplasm (53, 54). Pyruvate, phosphate dikinase catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate to phosphoenolpyruvate; this reaction requires inorganic phosphate and ATP plus pyruvate, producing phosphoenolpyruvate, AMP, and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi). The HCO3− is subsequently fixed via phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) that diffuses to the bundle sheath cells for decarboxylation (54). Malic enzyme catalyzes the four-carbon acid malate conversion to pyruvate in bundle sheath cells. The levels of all these enzymes drastically increased during the transition from dark to light (Fig. 7). Notably PEPCK, the key enzyme of the PEPCK C4 pathway, was not detected until etiolated seedlings were exposed to light for 6 h, and its level increased drastically after longer exposure to light (12 h and control). In addition, two PEPCs (PEPC 1 and PEPC 1C) were identified. Among the 41 identified peptides for PEPC 1, only five identical peptides matched PEPC 1C, and only three of 21 identified peptides in PEPC 1C matched PEPC 1, indicating that these proteins are distinct (supplemental Table S7). Amino acid sequence comparison of the two PEPCs revealed that they are 81% identical (supplemental Fig. S2). PEPC 1C is apparently much more sensitive to light regulation than PEPC 1 as PEPC 1C was not identified in 0-h etiolated seedlings, but its level increased substantially after seedlings were exposed to light.

Fig. 7.

Pathways involved in carbon assimilation. PEPCK C4 pathway is depicted as following the blue arrows. The NADP-ME C4 pathway is depicted as following the light blue arrows. The Calvin cycle is depicted as following the pink arrows. Only those proteins whose abundance changed in response to light are mapped. 1, carbonic anhydrase (AAA86945.1); 2a, PEPC 1 (CAA33316.1); 2b, PEPC 1C (NP_001105503.1); 3, malic enzyme (AAP33011.1); 4, pyruvate, phosphate dikinase (AAA33498.1); 5, PEPCK (Q9SLZ0.1); 6, Rubisco activase (AAC97932.3); 7, Rubisco large subunit (NP_043033.1); 8, Rubisco small subunit (CAA70416.1); 9, phosphoglycerate kinase (AAM51721.1); 10, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase A (CAA33455.1). PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; OAA, oxaloacetate; G3P, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; 3PGA, 3-phosphoglyceric acid; RuBP, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate; R5P, ribose 5-phosphate; 1,3BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate.

Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) catalyzes the first major step of carbon fixation in the Calvin cycle. Here we identified and quantified a Rubisco large subunit, a Rubisco small subunit, and Rubisco activase. The levels of these proteins, particularly the large and small subunits, increased drastically after etiolated seedlings were exposed to light. To our surprise, Rubisco small subunit increased in abundance by 4-fold after 6 h of exposure but decreased by 3-fold by 12 h relative to 6 h; this subunit increased by 5-fold in control seedlings (Fig. 7 and Table I). The observed anomalous expression of this Rubisco small subunit might have resulted from some post-translational modifications that lowered the apparent abundance of the unmodified peptide. Another key enzyme, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, also increased in abundance during maize seedlings de-etiolation. Taken together, these results suggested that the C4 photosynthetic pathway is tightly regulated by light via modulation of expression of these key enzymes.

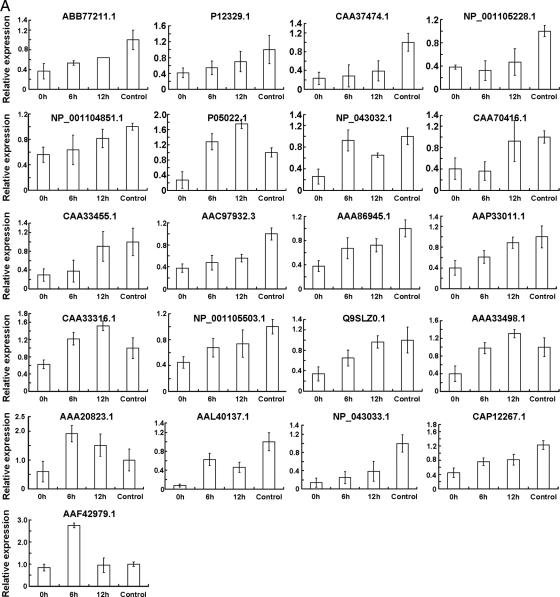

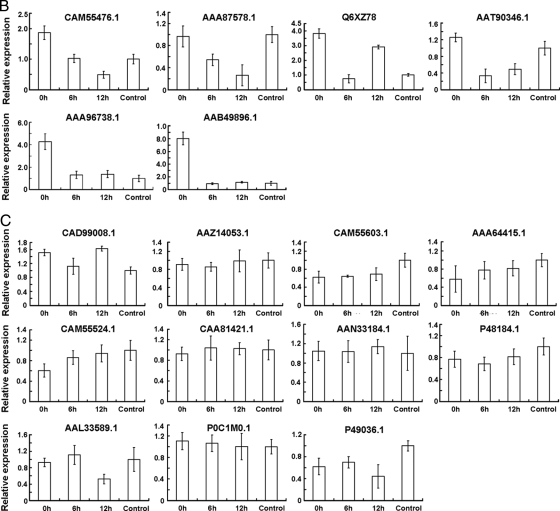

QRT-PCP Analysis of Genes Encoding Proteins Whose Abundance Changed Dramatically upon Exposure to Light

To understand the relationship between protein accumulation and their encoding gene transcription, we carried out a comparison of mRNA and protein expression. The transcripts of 38 genes encoding proteins whose levels changed by >2-fold during etiolated seedling greening were analyzed by reverse transcription followed by QRT-PCR. Among these, 21 genes were up-regulated (Fig. 8A and Table I), six were down-regulated (Fig. 8B), and 11 did not change significantly during the dark/light transition (Fig. 8C and Table I). We found that changes in the pattern of transcription of genes encoding the key enzymes involved in carbon assimilation were highly similar to the observed changes in protein abundance; these included genes encoding carbonic anhydrase (AAA86945.1), malic enzyme (AAP33011.1), PEPC 1 (CAA33316.1), PEPC (NP_001105503.1), PEPCK (Q9SLZ0.1), Rubisco large subunit (NP_043033.1) and small subunit (CAA70416.1), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase A (CAA33455.1), Rubisco activase (AAC97932.3), and pyruvate, phosphate dikinase (AAA33498.1). Interestingly POR (CAD99008.1) and the subunits of PSI (PSI type III chlorophyll a/b-binding protein) and PSII (LHCP (Lhcb1), LHCP (Cab-m7), CP24 (CAM55603.1), CP26 (AAA64415.1), CP29 (Lhcb6) (CAM55524.1), D1 (AAN33184.1), and D2 (P48184.1)) exhibited the most drastic changes in protein abundance upon exposure to light, and their corresponding mRNA levels remained nearly unchanged except for LHCP1 (P12329.1) and LHCP (CAA37474.1) for which the mRNA levels increased (Fig. 8 and Table I). Also noteworthy is that some of the PSII and PSI subunits could not be detected in 0-h or in both 0- and 6-h seedlings, whereas their mRNAs accumulated to high levels at these time points, suggested that the levels of these mRNAs do not always correlate with the abundance of their corresponding proteins.

Fig. 8.

Transcriptional profiles of the genes encoding the proteins whose levels changed by over 2-fold during etiolated maize seedling greening. Total RNA samples prepared from leaves of control seedlings or leaves of etiolated seedlings exposed to light for 0, 6, or 12 h were used as templates for QRT-PCR analysis. Error bars indicate means ± S.E. obtained from three amplification experiments using independent RNA samples.Based on their transcriptional change profile during etiolated maize seedling greening, these genes were divided into three groups, namely up-regulated (A), down-regulated (B), and no evident change (C). The NCBI database accession numbers correspond to those listed in Table I.

DISCUSSION

The identification of proteins that are differentially expressed during greening of etiolated maize seedlings is a crucial step to elucidating the mechanisms underlying light responses. In the present study, we initiated a proteomics investigation during maize seedling de-etiolation by using a label-free method in which two of the most important elements are reproducibility of LC and mass measurement accuracy. The mass accuracy was typically within 5 ppm, and the retention time coefficient variation was within 0.6%, which is well within the specification of the system we used and suitable for label-free quantitative analysis.

As mentioned in the Introduction, the label-free method presented advantages for analyzing hydrophobic proteins and low abundance proteins. As expected, in our study 25 membrane proteins were identified and quantified (Table I); to our knowledge, few gel-based proteomics studies have identified so many membrane proteins. For example, we identified POR, which is abundant in etiolated seedlings but has never been identified in similar experiments using 2-DE methods (3, 4). These results indicate that our newly developed MSE-based label-free method is robust, highly reproducible, and sensitive and thus is ideally suited to proteomics studies of this type. And if the membrane was isolated or enriched, undoubtedly additional low abundance membrane proteins could be identified by our newly developed label-free method.

During etiolated maize seedling greening, the abundance of 37 chloroplast proteins changed, accounting for 51% of the total changed proteins. This indicates that the presence or absence of light dramatically influences plastid development. This result is consistent with the fact that proteins involved in chlorophyll synthesis and photosynthesis, particularly the photosynthetic apparatus, must be rapidly synthesized and accumulated as etioplasts develop into chloroplasts.

The increase in pigment concentration is an essential step during the transformation from etioplasts to fully developed chloroplasts, and the increase in pigment content is mainly due to the synthesis of chlorophylls a and b (51). In our present study, chlorophyll a and b were barely detectable in etiolated seedlings, but their abundance rapidly increased upon exposure to light (Fig. 1B). Three enzymes participating in chlorophyll synthesis were identified in etiolated seedlings, suggesting that a large amount of the chlorophyll precursors, protochlorophyllides, might have been synthesized and accumulated in etioplasts; when the etiolated seedlings were exposed to light, they rapidly converted protochlorophyllide into chlorophyll. Interestingly POR, which catalyzes the only light-dependent reaction in the chlorophyll biosynthetic pathway and is hence intimately involved in angiosperm greening (56), was drastically down-regulated after dark-grown maize seedlings were exposed to light (Table I). POR is present at high levels as a ternary complex with protochlorophyllide and NADPH, forming a prolamellar body that is the specific apparatus in the etioplast of dark-grown angiosperms (57). Therefore, a drastic decrease in the level of POR could result in dispersion of the prolamellar body, which would accelerate etioplast development into chloroplasts. In Arabidopsis, there are three PORs denoted as PORA–C (58, 59). PORA is negatively regulated by light, and its level drops as a result of the concerted effect of light at the levels of transcription, mRNA stability, plastid import, and protein degradation (60). PORB is constitutively expressed in dark-grown, illuminated, and light-adapted plants (61). Transcription from the PORC gene is tightly regulated by light (62). Although the maize POR we identified is highly similar to Arabidopsis PORC (Fig. 4B), the accumulation pattern of maize POR was similar to that of PORA, which is negatively regulated by light. Moreover the transcriptional pattern of maize POR was similar to that of Arabidopsis PORB (Fig. 8C, CAD99008.1), which is not affected by a dark/light shift. All these results indicate that maize POR might be subject to complex post-transcriptional regulation in response to light.

It has been reported that illumination of etioplasts initiates the dispersal of the prolamellar body and the formation of thylakoid membranes where the chlorophyll a/b-binding proteins and chlorophyll form the pigment-protein complexes of the photosynthetic apparatus (63). Upon insertion into thylakoid membrane, the LHCII apoprotein undergoes a major structural change to accommodate chlorophyll and carotenoids (64). Consistent with these findings, three minor LHCII proteins (CP24, CP26, and CP29) were absent in both 0- and 6-h seedlings, and a major LHCII (Lhcb1), a light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding protein (Cab-m7), and a PSI type III chlorophyll a/b-binding protein were absent in 0-h seedlings. Besides these proteins, PSII reaction center proteins D1 and D2 were also absent in both 0- and 6-h seedlings (Fig. 5 and Table I). At these two time points, the chlorophylls were barely detectable in etioplasts or at very low levels in developing chloroplasts (Fig. 1B). This finding agrees with previous data that chlorophyll plays an essential role in the accumulation of LHCI and LHCII, and chlorophyll may be required to induce correct folding of these proteins (65, 66). QRT-PCR analysis of the genes encoding the PSI and PSII subunits, which were absent in 0-h or in both 0- and 6-h seedlings, revealed that the mRNAs accumulated at very high levels at these time points (Fig. 8C). This suggests that transcriptional regulation is not the rate-limiting step in the biosynthesis of these proteins. A similar phenomenon was observed by Flachmann and Kühlbrandt in tobacco (64). Taken together, these results indicate that POR might have two different functions, one as a structural protein to form the prolamellar body in etioplasts and another as an enzyme or a plastid-specific photon sensor that triggers chlorophyll biosynthesis and membrane reorganization during the transformation of etioplasts into chloroplasts. Most PSI and PSII subunits were not directly regulated at the transcriptional level by light. Sufficient levels of both chlorophyll and mature thylakoid membrane are necessary for the formation of pigment-protein complexes to avoid rapid turnover via the proteasome system.

Distinct from results obtained for POR and the subunits of PSI and PSII, light directly promotes the accumulation of nine enzymes involved in carbon assimilation by inducing expression of their genes (Fig. 8A). Five of these proteins have been reported to be regulated at the transcriptional level by light: transcription genes of the Rubisco small subunit, PEPC, malic enzyme, and pyruvate, phosphate dikinase are regulated by light, and their promoter cis-regulatory elements, which are responsible for light regulation, also have been identified (67–70); the level of PEPCK mRNA is also much higher in daytime than at night (51). Therefore, it is possible that the remaining four genes also have similar light-regulated cis-elements in their promoters. By regulating these elements, light induces rapid transcription of these genes so that their encoded enzymes can accumulate to meet the requirements during the transition from etiolated to green seedlings.

C4 plants have been classified as NADP-ME, NAD-ME, and PEPCK subtypes according to the major decarboxylase involved in the decarboxylation of C4 acids in bundle sheath cells (71, 72). Maize (Z. mays) is the classical member of the NADP-ME subgroup of C4 plants. Accumulating evidence indicates, however, that there are two distinct pathways for the decarboxylation of malate and aspartic acid in maize and probably in other species previously classified as NADP-ME types (48, 51). In our current study, PEPCK, the key enzyme of the PEPCK C4 pathway, was not identified in etiolated maize seedlings but was highly expressed after exposure to light (6 and 12 h and control), whereas the NADP-ME pathway enzymes for the decarboxylation of malate were all identified in etiolated seedlings, although they were at much lower abundance than in seedlings exposed to light (Fig. 7). These results suggest that between the two complementary C4 pathways in maize the PEPCK pathway might be much more sensitive to light. In addition, we identified and quantified two PEPCs. One is the C4 form, PEPC 1, which plays a cardinal role in the initial CO2 fixation during C4 photosynthesis by incorporating atmospheric CO2 into C4 dicarboxylic acids (52), and the other is the root form, PEPC 1C, which reportedly is specifically expressed in roots and plays various anaplerotic roles, including providing the carbon skeletons for nitrogen assimilation, pH maintenance, and osmolarity regulation, etc. (55). Our results are not in agreement with previous research, however, in that we detected both PEPC 1C mRNA and protein in young maize leaves, and levels of both were strongly sensitive to light (Fig. 7, 2b and Fig. 8A, NP_001105503.1). These results suggest that PEPC 1C might function similarly to PEPC 1 and take part in light-regulated carbon assimilation.

In conclusion, our label-free quantitative proteomics approach based on nano-UPLC-MSE provided for precise and reproducible quantification of over 400 proteins during de-etiolation of maize seedlings. This method constitutes a powerful means of proteins quantification and identification, particularly of membrane proteins identification, that is far superior to 2-DE methods. The method also revealed detailed information that could not be obtained with other proteomics and genomics approaches. Our current experimental results illustrate the power of label-free quantitative proteomics to enhance our understanding of maize seedling de-etiolation and provide important clues for further study of light-induced development of C4 plants. Furthermore this study sets a good example for using a nano-UPLC-MSE label-free method in plant research. We expect that this approach will find broad applications in studies of any plant biological process, such as development, environment stress, and mutation, in which changes in protein expression are to be measured.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

* This work was supported by Basic Natural Sciences Foundation of Northeast Forestry University Grant 010-602049.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.mcp.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and Tables S1–S15.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.mcp.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and Tables S1–S15.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- 2-DE

- two-dimensional electrophoresis

- AMRT

- accurate mass and retention time

- ME

- malic enzyme

- MSE

- low/high collision energy MS

- nano-UPLC

- nanoscale ultraperformance LC

- PEPC

- phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase

- PEPCK

- phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase

- PLGS

- ProteinLynx GlobalServer

- POR

- NADPH-protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase

- PS

- photosystem

- QRT-PCR

- quantitative real time RT-PCR

- Rubisco

- ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase

- UPLC

- ultraperformance LC

- NCBI

- National Center for Biotechnology Information

- LHCP

- light-harvesting complex protein

- LHC

- light-harvesting complex

- BEH

- ethylene bridged hybrid

REFERENCES

- 1.Deng X. W., Quail P. H. (1999) Signalling in light-controlled development. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 10, 121– 129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang H., Deng X. W. (2003) Dissecting the phytochrome A-dependent signaling network in higher plants. Trends Plant Sci. 8, 172– 178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang B. C., Pan Y. H., Meng D. Z., Zhu Y. X. (2006) Identification and quantitative analysis of significantly accumulated proteins during the Arabidopsis seedling de-etiolation process. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 48, 104– 113 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang P., Chen H., Liang Y., Shen S. (2007) Proteomic analysis of de-etiolated rice seedlings upon exposure to light. Proteomics 7, 2459– 2468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chory J., Chatterjee M., Cook R. K., Elich T., Fankhauser C., Li J., Nagpal P., Neff M., Pepper A., Poole D., Reed J., Vitart V. (1996) From seed germination to flowering, light controls plant development via the pigment phytochrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 12066– 12071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clouse S. D. (2001) Integration of light and brassinosteroid signals in etiolated seedling growth. Trends Plant Sci. 6, 443– 445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alabadí D., Gil J., Blázquez M. A., García-Martínez J. L. (2004) Gibberellins repress photomorphogenesis in darkness. Plant Physiol. 134, 1050– 1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chory J., Reinecke D., Sim S., Washburn T., Brenner M. (1994) A role for cytokinins in de-etiolation in Arabidopsis. Det mutants have an altered response to cytokinins. Plant Physiol. 104, 339– 347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terzaghi W. B., Cashmore A. R. (1995) Photomorphogenesis: Seeing the light in plant development. Curr. Biol. 5, 466– 468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phee B. K., Cho J. H., Park S., Jung J. H., Lee Y. H., Jeon J. S., Bhoo S. H., Hahn T. R. (2004) Proteomic analysis of the response of Arabidopsis chloroplast proteins to high light stress. Proteomics 4, 3560– 3568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan C. S., Peng H. P., Shih M. C. (2002) Mutations affecting light regulation of nuclear genes encoding chloroplast glyceraldehyde- 3-phosphate dehydrogenase in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 130, 1476– 1486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neff M. M., Fankhauser C., Chory J. (2000) Light: an indicator of time and place. Genes Dev. 14, 257– 271 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fankhauser C., Chory J. (1997) (1997) Light control of plant development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13, 203– 229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuno N., Furuya M. (2000) Phytochrome regulation of nuclear gene expression in plants. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 485– 493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caffarri S., Frigerio S., Olivieri E., Righetti P. G., Bassi R. (2005) Differential accumulation of Lhcb gene products in thylakoid membranes of Zea mays plants grown under contrasting light and temperature conditions. Proteomics 5, 758– 768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vissers J. P., Langridge J. I., Aerts J. M. (2007) Analysis and quantification of diagnostic serum markers and protein signatures for Gaucher disease. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 755– 766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tam E. M., Morrison C. J., Wu Y. I., Stack M. S., Overall C. M. (2004) Membrane protease proteomics: Isotope-coded affinity tag MS identification of undescribed MT1-matrix metalloproteinase substrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101,6917– 6922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross P. L., Huang Y. N., Marchese J. N., Williamson B., Parker K., Hattan S., Khainovski N., Pillai S., Dey S., Daniels S., Purkayastha S., Juhasz P., Martin S., Bartlet-Jones M., He F., Jacobson A., Pappin D. J. (2004) Multiplex protein quantification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3, 1154– 1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ong S. E., Blagoev B., Kratchmarova I., Kristensen D. B., Steen H., Pandey A., Mann M. (2002) Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1, 376– 386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shevchenko A., Chernushevich I., Ens W., Standing K. G., Thomson B., Wilm M., Mann M. (1997) Rapid ‘de novo’ peptide sequencing by a combination of nanoelectrospray, isotopic labeling and a quadrupole/ time-of-flight mass spectrometer. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 11, 1015– 1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao X., Freas A., Ramirez J., Demirev P. A., Fenselau C. (2001) 18O labeling for comparative proteomics: model studies with two serotypes of adenovirus. Anal. Chem. 73, 2836– 2842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva J. C., Denny R., Dorschel C. A., Gorenstein M., Kass I. J., Li G. Z., McKenna T., Nold M. J., Richardson K., Young P., Geromanos S. J. (2005) Quantitative proteomic analysis by accurate mass retention time pairs. Anal. Chem. 77, 2187– 2200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva J. C., Denny R., Dorschel C., Gorenstein M. V., Li G. Z., Richardson K., Wall D., Geromanos S. J. (2006) Simultaneous qualitative and quantitative analysis of the Escherichia coli proteome: a sweet tale. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 589– 607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes M. A., Silva J. C., Geromanos S. J., Townsend C. A. (2006) Quantitative proteomic analysis of drug-induced changes in mycobacteria. J. Proteome Res. 5, 54– 63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang W., Zhou H., Lin H., Roy S., Shaler T. A., Hill L. R., Norton S., Kumar P., Anderle M., Becker C. H. (2003) Quantification of proteins and metabolites by mass spectrometry without isotopic labeling or spiked standards. Anal. Chem. 75, 4818– 4826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radulovic D., Jelveh S., Ryu S., Hamilton T. G., Foss E., Mao Y., Emili A. (2004) Informatics platform for global proteomic profiling and biomarker discovery using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3, 984– 997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiener M. C., Sachs J. R., Deyanova E. G., Yates N. A. (2004) Differential mass spectrometry: a label-free LC-MS method for finding differences in complex peptide and protein mixtures. Anal. Chem. 76, 6085– 6096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.America A. H., Cordewener J. H., van Geffen M. H., Lommen A., Vissers J. P., Bino R. J., Hall R. D. (2006) Alignment and statistical difference analysis of complex peptide data sets generated by multidimensional LC-MS. Proteomics 6, 641– 653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian W. J., Jacobs J. M., Liu T., Camp D. G., 2nd, Smith R. D. (2006) Advances and challenges in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based proteomics profiling for clinical applications. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 1727– 1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plumb R., Castro-Perez J., Granger J., Beattie I., Joncour K., Wright A. (2004) Ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to quadrupole-orthogonal time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 18, 2331– 2337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Motoyama A., Venable J. D., Ruse C. I., Yates J. R., 3rd (2006) Automated ultra-high-pressure multidimensional protein identification technology (UHP-MudPIT) for improved peptide identification of proteomic samples. Anal. Chem. 78, 5109– 5118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silva J. C., Gorenstein M. V., Li G. Z., Vissers J. P., Geromanos S. J. (2006) Absolute quantification of proteins by LCMSE: a virtue of parallel MS acquisition. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 144– 156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu D., Suenaga N., Edelmann M. J., Fridman R., Muschel R. J., Kessler B. M. (2008) Novel MMP-9 substrates in cancer cells revealed by a label-free quantitative proteomics approach. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7, 2215– 2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edwards G, Walker D. A. (eds) (1983) C3, C4: Mechanisms, Cellular and Environmental Regulation of Photosynthesis, pp. 326–410, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson T., Langdale J. A. (1992) Developmental genetics of C4 photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 43, 25– 47 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langdale J. A. (1998) Cellular differentiation in the leaf. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 10, 734– 738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheen J. (1999) C4 gene expression. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 187– 217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Majeran W., Cai Y., Sun Q., van Wijk K. J. (2005) Functional differentiation of bundle sheath and mesophyll maize chloroplasts determined by comparative proteomics. Plant Cell 17, 3111– 3140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Majeran W., Zybailov B., Ytterberg A. J., Dunsmore J., Sun Q., van Wijk K. J. (2008) Consequences of C4 differentiation for chloroplast membrane proteomes in maize mesophyll and bundle sheath cells. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7, 1609– 1638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Washburn M. P., Wolters D., Yates J. R., 3rd (2001) Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 242– 247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]