Abstract

The lack of consensus sequence, common core structure, and universal endoglycosidase for the release of O-linked oligosaccharides makes O-glycosylation more difficult to tackle than N-glycosylation. Structural elucidation by mass spectrometry is usually inconclusive as the CID spectra of most glycopeptides are dominated by carbohydrate-related fragments, preventing peptide identification. In addition, O-linked structures also undergo a gas-phase rearrangement reaction, which eliminates the sugar without leaving a telltale sign at its former attachment site. In the present study we report the enrichment and mass spectrometric analysis of proteins from bovine serum bearing Galβ1–3GalNAcα (mucin core-1 type) structures and the analysis of O-linked glycopeptides utilizing electron transfer dissociation and high resolution, high mass accuracy precursor ion measurements. Electron transfer dissociation (ETD) analysis of intact glycopeptides provided sufficient information for the identification of several glycosylation sites. However, glycopeptides frequently feature precursor ions of low charge density (m/z > ∼850) that will not undergo efficient ETD fragmentation. Exoglycosidase digestion was utilized to reduce the mass of the molecules while retaining their charge. ETD analysis of species modified by a single GalNAc at each site was significantly more successful in the characterization of multiply modified molecules. We report the unambiguous identification of 21 novel glycosylation sites. We also detail the limitations of the enrichment method as well as the ETD analysis.

Glycosylation is among the most prevalent post-translational modifications of proteins; it is estimated that over half of all proteins undergo glycosylation during their lifespan (1). Glycosylation of secreted proteins and the extracellular part of membrane proteins occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and the contiguous Golgi complex. The side chains of Trp, Asn, and Thr/Ser residues can be modified, termed as C-, N-, and O-glycosylation, respectively (2, 3). In addition, O-glycosylation also occurs within the nucleus and the cytosol: a single GlcNAc residue modifies Ser and Thr residues. O-GlcNAc glycosylation fulfills a regulatory/signaling function similar to phosphorylation (4).

From an analytical point of view, C-glycosylation is the simplest. A consensus sequence has been defined: WXXW where the first Trp is modified, and the modification, a Man moiety, readily survives sample preparation and mass spectrometric analysis, including collisional activation (5). Investigation of N-glycosylation is also facilitated by several factors. First, N-glycosylation again has a well defined consensus sequence: NX(S/T/C) where the middle amino acid cannot be Pro (6). Second, there is a universal core glycan structure: GlcNAc2Man3; and this core is conserved across species. Third, a specific endoglycosidase, peptide N-glycosidase F, has been identified. This enzyme cleaves the carbohydrate structure from the peptide, leaving behind a diagnostic sign: the Asn residue is hydrolyzed to Asp, inducing a mass shift of +1 Da. By contrast, analysis of O-glycosylation is hampered by a lack of (i) a consensus sequence, (ii) a universal core structure, and (iii) a universal endoglycosidase or gentle chemical hydrolysis method to facilitate analysis.

Glycosylation shows a high degree of species and tissue specificity; the same site may be modified by a wide variety of different glycan structures, and unmodified variants of the protein may occur simultaneously (7–9). Disease and physiological changes also may alter the glycosylation pattern (10–12). The biological role(s) of glycosylation has been studied extensively (13–15), although such studies are seriously hampered by the difficulties of glycosylation analysis.

Most secreted proteins are glycosylated; and thus, mammalian serum is rich in glycoproteins. On the other hand, O-linked glycoproteins represent a small percentage of the serum protein content. Glycoproteins may display a befuddling heterogeneity both in site specificity and site occupancy. Thus, the enrichment of modified proteins or peptides is necessary for their characterization, and different techniques have been tested for this purpose. Lectin affinity chromatography is a popular method for selective isolation of glycoproteins and glycopeptides. Concanavalin A can be used to isolate oligomannose type glycopeptides (16), wheat germ agglutinin is applied for GlcNAc-containing compounds (16, 17), and jacalin is selective for core-1 type O-glycopeptides (18, 19). Lectins with preferential affinity for fucosylated and sialylated structures can also be utilized (12). Non-selective capture of glycopeptides can be performed using hydrophilic interaction chromatography (20, 21) or size exclusion chromatography (22). A recent approach applies porous graphite columns for semiselective enrichment (23), whereas the acidic character of sialylated glycopeptides has also been exploited via titanium dioxide-mediated enrichment (24). Finally vicinal cis-diols can be selectively captured using boronic acid derivatives (25–27). All methods described here provide some glycopeptide enrichment from non-glycosylated peptide background, but all also suffer from significant non-selective binding. N-Linked glycoproteins may also be selectively captured on hydrazide resin following periodate oxidation (28). This approach requires enzymatic deglycosylation to release the captured peptides for analysis, therefore excluding the determination of the carbohydrate structure.

Intact glycopeptide characterization still represents a significant challenge. Edman degradation, either alone or in combination with mass spectrometry, has been utilized for such tasks (29, 30). CID analysis of O-linked glycopeptides has limited utility. (i) MS/MS analysis cannot differentiate between the isomeric carbohydrate units and usually does not reveal the linkage positions and the configuration of the glycosidic bonds. (ii) Such spectra are typically dominated by abundant product ions associated with carbohydrate fragmentation, namely non-reducing end oxonium ions and product ions formed via sequential neutral losses of sugar residues from the precursor ions. (iii) The glycan is cleaved from the peptide via a gas-phase rearrangement reaction, and as a result the peptide itself and most peptide fragments (if any) are detected partially or completely deglycosylated (31–33). Recently a different approach, the combination of positive and negative ion mode infrared multiphoton dissociation, was found to provide conclusive structural assignment for some O-linked glycopeptides (34). However, two novel MS/MS techniques, electron capture dissociation (ECD),1 which is performed in FT-ICR mass spectrometers (35), and electron transfer dissociation (ETD), which is performed in various ion trapping devices (36), may represent the real breakthrough. In both cases an electron is transferred to multiply protonated peptide cations, triggering peptide fragmentation at the covalent bond between the amino group and the α-carbon, producing mostly c and radical z· product ions while leaving the side chains intact. ETD is typically more efficient than ECD and thus leads to more comprehensive fragmentation. In addition, ETD can be performed in ion traps and thus, at a higher sensitivity level, especially in a linear ion trap. Because it has been observed that there are instances when the electron transfer is efficient and still no significant fragmentation occurs, ETD is usually combined with supplementary (and gentle) CID activation (37). O-Glycosylation analysis using these new dissociative techniques has been investigated (38, 39). However, because of the complexity of extracellular O-glycosylation, analysis of complex mixtures is rarely attempted (18), and the above techniques are usually restricted to the analysis of purified proteins.

In this study we present the analysis of secreted O-linked glycopeptides. Lectin (jacalin) affinity chromatography was used to achieve some enrichment of core-1 O-GalNAcα type carbohydrate-carrying glycopeptides from bovine serum. The glycopeptide fractions were subjected to CID and ETD analysis. These experiments were performed on a linear ion trap-Orbitrap hybrid mass spectrometer (40). The Orbitrap delivered high resolution, high mass accuracy for the precursor ions, whereas the linear trap provided high sensitivity MS/MS analyses. Some fractions were also subjected to sequential exoglycosidase digestions, and glycopeptides retaining only the proximal GalNAc residues were analyzed. ProteinProspector v5.2.1, developed to accommodate ETD product ion spectra, aided data interpretation (41). We identified 26 glycosylation sites from bovine serum unambiguously; 21 of these sites have never been reported by any other study. No other single study to date has yielded so much information about O-linked glycosylation sites.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Jacalin Affinity Chromatography

Affinity columns were prepared by packing agarose-bound jacalin (Vector Laboratories, AL-1153; binding capacity, >4 mg of asialofetuin/ml of gel) into perfluoroalkoxyalkane tubing (Upchurch Scientific, 1507L) equipped with a 0.5-μm frit at its distal end. The pressure was maintained at <4 megapascals during packing. Two affinity columns were prepared: column 1, 1 × 2000 mm (CV, 1.57 ml); and column 2, 1 × 200 mm (CV, 0.157 ml).

Affinity enrichment was performed on an Amersham Biosciences AKTA FPLC system (complete with P920 pump, M925 gradient mixer, UPC-900 UV conductivity monitor, and Frac 900 fraction collector) equipped with a 2-ml sample loop. After introducing the sample (flow rate, 50 μl/min), the column was washed with solvent A (175 mm Tris·HCl, pH 7.5; flow rate, 150 μl/min), and then the species bound were eluted with solvent B (0.8 m galactose, 175 mm Tris·HCl, pH 7.5; flow rate, 150 μl/min), collecting 2-min fractions.

Single Enrichment

Tryptic peptides from fetal bovine serum were fractionated on column 1 (washing with 8 CVs of solvent A and elution with 6 CVs of solvent B). Fractions of interest were acidified and desalted on C18 reversed phase (Varian Omix A57003100 100-μl pipette tip) prior to LC/MS analysis.

Double Enrichment

Fetal bovine serum was directly injected to column 1 (washing with 8 CVs of solvent A and elution with 6 CVs of solvent B). Combined fractions of interest were digested with trypsin and subjected to a second enrichment on column 2 (washing with 20 CVs of solvent A and elution with 30 CVs of solvent B). Fractions of interest were acidified and desalted on C18 reversed phase (Varian Omix A57003100 100-μl pipette tip) prior to LC/MS analysis.

Tryptic Digestion

Samples were complemented with guanidine hydrochloride to give a final concentration of 6 m. Disulfide bridges were reduced using DTT (56 °C for 60 min), and the resultant free sulfhydryl groups were derivatized using iodoacetamide (1.1× equivalent to DTT; 60 min in the dark at room temperature). Samples were then diluted 8-fold with 100 mm ammonium bicarbonate to reduce the guanidine hydrochloride concentration and incubated with porcine trypsin (Fluka, 93614; 1–2% (w/w) of the estimated protein content) at 37 °C for 6 h. Digestion was stopped by adding acetic acid (final pH 3). The resulting peptide mixtures were desalted on a C18 reversed phase column (Vydac 218TP52205), lyophilized, and stored at −20 °C prior to analysis.

Partial Deglycosylation of O-Glycopeptides

Sialic acid and β-galactose units of glycopeptides were removed by incubation with neuraminidase (New England Biolabs, P0720; 50 units in 100 mm sodium citrate, pH 6.0) for 1 h at 37 °C followed by overnight treatment with β-galactosidase (New England Biolabs, P0726; 10 units in 100 mm sodium citrate, pH 4.5) at 37 °C. Enzymatic deglycosylation was stopped by acidification to pH 3 with formic acid, and the resulting peptide mixtures were desalted on C18 reversed phase (Millipore, ZTC18S960; 10-μl C18 pipette tip).

Mass Spectrometry

Glycopeptide mixtures were separated on a nanoflow reversed phase HPLC system directing the eluent to nanospray sources of ESI-MS instruments operating in positive ion mode. The operating parameters for the different LC/MS systems were as follows. A quadrupole-orthogonal time-of-flight hybrid mass spectrometer (Q-TOF Premier) was on line-coupled with a nano-HPLC system (nanoACQUITY) (both Waters Micromass). For LC, in-line trapping onto a nanoACQUITY UPLC trapping column (Symmetry, C18 5 μm, 180 μm × 20 mm) (15 μl/min with 3% solvent B) followed by a linear gradient of solvent B (10–50% in 40 min; flow rate, 250 nl/min; nanoACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column, 1.7 μm, 75 μm × 200 mm) was used. Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid in water, and solvent B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. For MS, CID spectra were acquired of the most abundant multiply charged ion from each MS survey with collision energy adjusted automatically according to the charge state and m/z value of the ion selected. Dynamic exclusion was also enabled; exclusion time was 60 s.

The linear ion trap-Orbitrap (LTQ-Orbitrap, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was on line-coupled to a nanoACQUITY HPLC system. Reversed phase chromatography was performed using the same column and the same solvents as described above. Peptides were eluted by a gradient from 2 to 35% solvent B in 35 min followed by a short wash at 50% solvent B before returning to starting conditions. For MS, data acquisition was carried out in data-dependent fashion acquiring sequential CID and ETD spectra of the three most intense, multiply charged precursor ions identified from each MS survey scan. (MS spectra were acquired in the Orbitrap, and CID and ETD spectra were acquired in the linear ion trap.) Ion populations within the trapping instruments were controlled by integrated automatic gain control (AGC). For CID, the AGC target was set to 30,000 with dissociation at 35% of normalized collision energy; activation time was 30 ms. For ETD, the AGC target values were set to 30,000 and 200,000 for the isolated precursor cations and fluoranthene anions, respectively, allowing 100 ms of ion/ion reaction time. Supplemental activation for the ETD experiments was enabled. Dynamic exclusion was also enabled; exclusion time was 60 s.

Data Interpretation

Data from the Q-TOF experiments were manually evaluated and were mostly used to ascertain that the samples contained a significant number of glycopeptides.

Peak lists from LTQ-Orbitrap raw data files were created by using the University of California San Francisco in-house peak picking program PAVA (42) as well as Bioworks 3.3.1 SP1. Both softwares generate separated CID and ETD peak lists. Database searching was performed by ProteinProspector v.5.2.1 against the Swiss-Prot database (April 24, 2008), which was supplemented with a random sequence for each entry, and the species was specified as Bos taurus (10170/725568 entries searched). Search parameters were as follows. Trypsin was selected as the enzyme, one missed cleavage was permitted, and nonspecific cleavage was also permitted at one of the peptide termini. The mass accuracy considered was 15 ppm for precursor ions and 0.6 Da for the fragment ions. The fixed modification was carbamidomethylation of Cys residues. Variable modifications were the default modifications, i.e. the acetylation of protein N termini, Met oxidation, and the cyclization of N-terminal Gln residues, supplemented with a HexHexNAc or SAHexHexNAc carbohydrate modification on Thr and Ser residues. A maximum of two modifications per peptide was permitted. The same search parameters were used for the ETD data after the exoglycosidase digestion except Ser and Thr residues were considered modified by HexNAc only, and three modifications per peptide were permitted. Search parameters for CID data acquired after the exoglycosidase treatment also included a modification of 203–203.1 Da on Ser and Thr residues leading to neutral losses of the same mass value; i.e. fragments were assumed to be unmodified. For all reported results the acceptance criteria were as follows: minimum peptide score, 15; minimum protein score, 15. All glycopeptide identifications having a maximal expectation value of 0.5 were manually inspected. We repeated our searches considering two missed cleavages as well as non-tryptic cleavages at both peptide termini and included some glycopeptides from these additional results.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

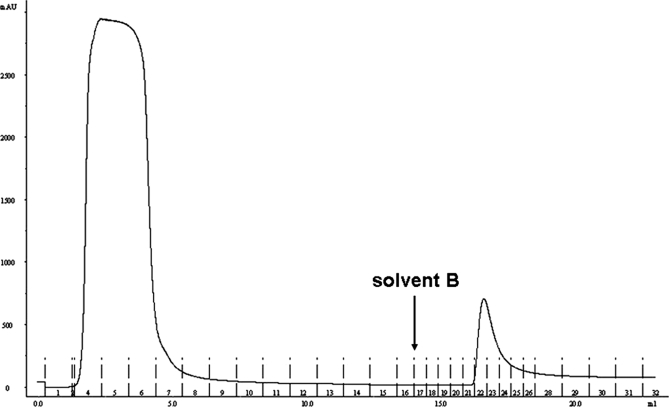

Enrichment of O-glycosylated peptides from bovine serum was achieved by affinity chromatography utilizing jacalin-agarose. Jacalin, a plant lectin from Artocarpus integrifolia, binds GalNAcα that is unsubstituted at C-6 (19, 43). We briefly validated the binding using a standard, fetuin tryptic digest, and then moved onto a more complex sample, the tryptic digest of bovine serum. It was found that O-linked glycopeptides indeed were enriched; however, a very high background due to nonspecific binding was observed. In the hope of eliminating the nonspecific background we also performed a two-step enrichment. First glycoproteins were enriched, and then the tryptic digest of the retained fractions was subjected to a second enrichment step. The result of the protein level enrichment is shown in Fig. 1. The retained fraction accounts for ∼5% of the total UV absorbance. This relatively high amount can be accounted for by considering the high concentration of fetuin in fetal serum (44) but also reflects nonspecific binding to the affinity column.

Fig. 1.

UV absorbance chromatogram (280 nm) of fetal bovine serum-derived proteins subjected to jacalin affinity chromatography. The Gal-containing solution was added as indicated. Approximately 5% of total protein content was retained. Two-minute fractions were collected. Fractions 22–24 were combined for further analyses. mAU, milliabsorbance units.

To confirm that glycopeptide enrichment indeed occurred, the resulting glycopeptide-containing fractions were subjected to a quick (1-h) data-dependent LC/MS/MS analysis on a Q-TOF instrument. Data were screened for characteristic glycopeptide fragments (31–33), for example for oxonium ions at m/z 204 (GalNAc) or m/z 292 (SA) as well as for sequential sugar losses from the precursor ion: −291 Da (SA), −162 Da (Gal), and −203 Da (GalNAc). Carbohydrate assignments were based on the lectin specificity, supported by exoglycosidase digestions (see later text). One of the double enrichment experiments was completely evaluated manually, and CID data indicated the presence of ∼130 glycopeptides. Unfortunately these spectra hardly ever contain sufficient information for the identification of the glycopeptides.

To gain sufficient information to determine both the identity of the glycopeptides and their site(s) of modification, a technique that breaks the peptide backbone while leaving the modification(s) intact is required. Fortunately ETD offers precisely these features.

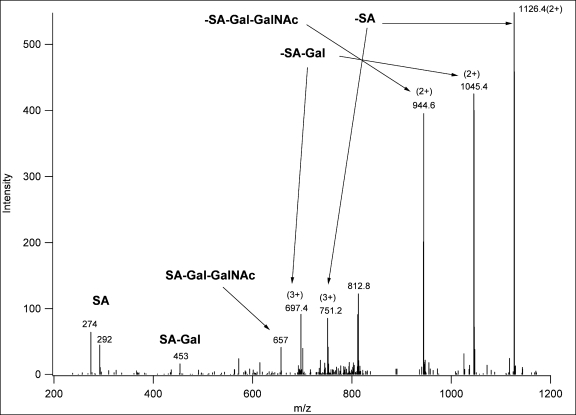

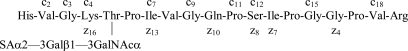

Thus, glycopeptide-containing fractions were subjected to LC/MS/MS experiments on a linear ion trap-Orbitrap hybrid instrument (LTQ-Orbitrap). Mass measurement was performed in the Orbitrap with high resolution and mass accuracy. Multiply charged precursor ions were subjected to both CID and ETD analysis in the linear ion trap. All spectra presented in this study were acquired in these analyses. CID spectra acquired in the linear ion trap were even less informative than those acquired in the Q-TOF instrument; they displayed practically exclusively carbohydrate fragments (oxonium ions as well as glycan-related neutral losses). If the charge state of the precursor ion was higher than 2, such fragment ions were frequently observed in multiple charge states (Fig. 2 and Scheme 1). In summary, low energy CID fragmentation of these glycopeptides provided sufficient information to confirm the presence of a glycopeptide, to determine the size and the number of the sugar units, and to ascertain the mass of the unmodified peptide.

Fig. 2.

Linear ion trap CID spectrum of m/z 848.39 (3+). The corresponding structure was identified as TEELQQQNTAPT(GalNAcGalSA)NSPTK from the ETD spectrum of the asialoglycopeptide (supplemental Fig. 26).

Scheme 1.

Illustration of the fragmentation shown in Fig. 2.

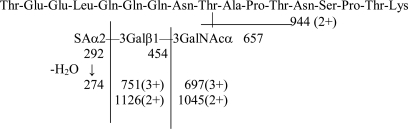

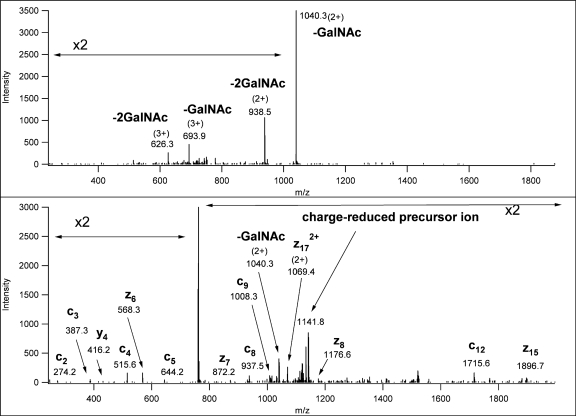

Database searches with the ETD data were performed using ProteinProspector v5.2.1. Two different glycans were considered on Ser and Thr residues: the GalGalNAc disaccharide and its sialylated version. The fractions contained unmodified peptides from a wide variety of serum proteins, and a significant portion of these displayed non-tryptic termini due to proteolytic enzyme activity in the serum (data not shown) similar to glycopeptides identified from these experiments. Half of the glycopeptides listed in Tables I and II feature non-tryptic termini. (For further examples see supplemental Tables 1 and 2.) Manual validation of the automated assignments led to the unambiguous identification of 17 glycosylation sites (listed with the best representative glycopeptide sequences in Table I; all automated assignments are presented in supplemental Table 1). Although ETD fragmentation is considered to leave the amino acid side chains intact, the glycopeptides investigated herein still exhibited a degree of carbohydrate fragmentation from the charge-reduced species (see Fig. 3, Scheme 2, and supplemental figures), which was unaccounted for within the parameters of the database search algorithm. Thus the score would be lowered by the presence of prominent, unassigned product ions. This fragmentation could result from the supplemental activation collisional warming, but radical site-induced glycosidic bond fragmentation has been reported previously in ECD experiments (45).

Table I. Glycosylation sites identified from the ETD data of intact glycopeptides.

Glycosylation sites identified and the carbohydrate structure detected are printed in bold. Residues in parentheses represent the amino acid residues before and after the sequence stretch identified. They are included to demonstrate the extent of nonspecific cleavages.

| Kininogen-1 precursor | (C)126LITPAEGPVVT(GalNAcGalSA)AQY139(E) |

| (F)578KLIS(GalNAcGalSA)DFPETTSPK590(C) | |

| Insulin-like growth factor II precursor | (K)154S(GalNAcGalSA)HRPLIALPT(GalNAcGalSA)QDPATHGGASSK175(A) |

| Fibronectin | (R)274HTSLQTT(GalNAcGalSA)SAGSGSFTDVR291(T) |

| α2-HS-glycoprotein precursor | (S)291VVVGPS(GalNAcGalSA)VVAVPLPLHR306(A) |

| (F)330HVGKT(GalNAcGalSA)PIVGQPSIPGGPVR348(L) | |

| (K)334TPIVGQPS(GalNAcGalSA)IPGGPVR348(L) | |

| β2-Glycoprotein 1 precursor | (A)20GRTC(carbamidomethyl)PKPDELPFST(GalNAcGal)VVPLKR39(T) |

| Apolipoprotein E precursor | (R)209AAT(GalNAcGalSA)LSTLAGQPLLER223(A) |

| (L)303ALRPSPT(GalNAcGalSA)SPPSENH316(−) | |

| Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor, heavy chain H1 precursor | (R)636KTFMLQASQPAPT(GalNAcGalSA)HSSLDIK655(K) |

| Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor, heavy chain H4 precursor | (R)702IKGTT(GalNAcGalSA)PT(GalNAcGalSA)ALPFAPVQAPSVILPLPGQSVDR731(L) |

| Pantetheinase precursor | (R)500LNPKT(GalNAcGalSA)DAWKS510(−) |

| Fetuin-B precursor | (K)284TEELQQQNTAPT(GalNAcGal)NSPTK300(A) |

| Plasma serine protease inhibitor precursor | (K)27IQEVPPAVT(GalNAcGalSA)TAPPGSR42(A) |

Table II. Additional glycosylation sites identified from ETD (or CID as indicated) spectra after exoglycosidase treatment.

Glycosylation sites identified and the carbohydrate structure detected are printed in bold. Residues in parentheses represent the amino acid residues before and after the sequence stretch identified. They are included to demonstrate the extent of nonspecific cleavages.

| Fibrinogen β chain | (−)1<QFPT(GalNAc)DYDEGQDDRPK15(V)a |

| Insulin-like growth factor II precursor | (R)93DVSASTTVLPDDVT(GalNAc)AYPVG111(K)+GalNAca |

| Apolipoprotein E precursor | (A)19DMEGELGPEEPLTT(GalNAc)QQPR36(D)a |

| (L)303ALRPSPT(GalNAc)S(GalNAc)PPSENH316(−) | |

| Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor, heavy chain H1 precursor | (F)639MLQAS(GalNAc)QPAPT(GalNAc)HSSLDIK655(K) |

| Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor, heavy chain H4 precursor | (L)680APAS(GalNAc)APSPTSGPGGASHDTDFR701(I)+GalNAc |

| (R)702IKGT(GalNAc)T(GalNAc)PT(GalNAc)ALPFAPVQAPSVILPLPGQSVDR731(I) | |

| Fetuin-B precursor | (N)281PSKTEELQQQNT(GalNAc)APTNSPTK300(A)+GalNAc |

| Plasma serine protease inhibitor precursor | (K)25KKIQEVPPAVT(GalNAc)T(GalNAc)APPGSR42(D) |

aIdentified from CID spectra.

Fig. 3.

ETD spectrum identifying a novel O-glycosylation site of bovine fetuin. The structure is HVGKT(GalNAcGalSA)PIVGQPSIPGGPVR. Neutral loss of sialic acid from the precursor ion was observed and is indicated as “−SA.”

Scheme 2.

Illustration of the fragmentation shown in Fig. 3.

An additional problem is the reliability of site assignment(s). Database searching algorithms routinely assign a modification site to sequence data even where unambiguous assignment information is unavailable. This is a general computational problem. O-Linked glycopeptides frequently feature Pro residues (see below), which may form y type product ions following the supplemental activation step, but no ETD-induced fragmentation occurs N-terminal to this imino acid residue. O-Linked glycopeptides also frequently feature multiple adjacent hydroxy amino acids, and unless near complete sequence coverage is achieved, the modification site cannot be unambiguously identified. Plenty of examples are listed in the supplementary tables, and supplemental Figs. 13, 21, and 28 illustrate these problems.

Only a small portion of the total glycopeptide content of the sample was fully characterized from these data. Unfortunately ETD fragmentation of precursor ions at m/z > ∼850 was inefficient. In the majority of the product ion spectra generated for these species only the presence of the charge-reduced precursor ions indicated that electron transfer had indeed occurred. This adverse effect of low charge density on peptide fragmentation has been documented (37).

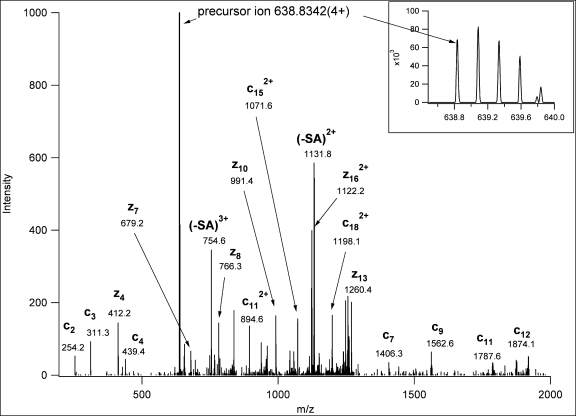

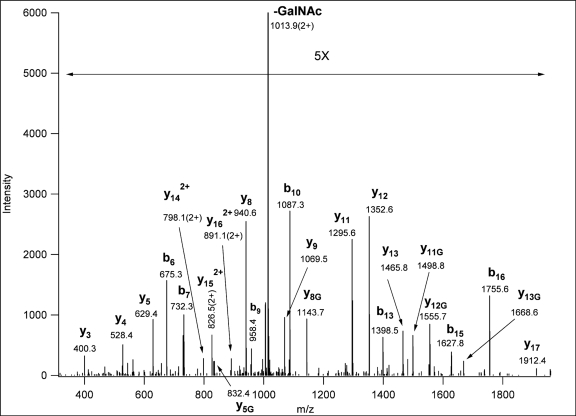

Although we cannot control the extent of ETD fragmentation of any given ion, one could try to increase the charge density to overcome poor fragmentation efficiency. This could be accomplished by reducing the mass of the precursor ion while retaining its charge. We assumed that partial deglycosylation would accomplish this effect. Sialidase and β-galactosidase treatment removes terminal sialic acid and galactose β1–3 residues, respectively. Partial deglycosylation was optimized using a fetuin glycopeptide mixture, and it was found that, although a ∼90-min treatment (37 °C) with neuraminidase is sufficient, complete removal of the galactose β1–3 units necessitates overnight incubation with β-galactosidase (data not shown). A tryptic glycopeptide mixture resulting from a double step enrichment experiment from fetal bovine serum was subjected to this exoglycosidase treatment and then to on-line CID and ETD analyses. This experiment led to the unambiguous determination of nine further glycosylation sites (listed in Table II with the best representative glycopeptide sequences; all identified glycopeptides are listed in supplemental Table 2). It is obvious that more multiply modified sequences were identified from the analysis of these only proximal GalNAc-modified glycopeptides. CID and ETD spectra of a doubly glycosylated peptide are shown in Fig. 4 (assignment of ETD fragment ions is depicted in Scheme 3). Although neutral losses of carbohydrate still dominate the resultant product ion spectra (Fig. 4, upper panel) CID analysis of the partially deglycosylated samples may lead to successful glycopeptide identifications and even to some site assignments (Fig. 5 and Scheme 4).

Fig. 4.

CID (upper panel) and ETD spectra (lower panel) from precursor ion m/z 761.4082 (3+), both acquired in the linear ion trap. The partially deglycosylated mixture was analyzed. The identified structure is KKIQEVPPAVT(GalNAc)T(GalNAc)APPGSR.

Scheme 3.

Illustration of the fragmentation shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

CID spectrum (from precursor ion m/z 1115.5117 (2+) acquired in the linear ion trap from the partially deglycosylated mixture. Neutral sugar loss from the precursor ion is indicated as “−GalNAc.” Fragment ions that retained the carbohydrate are labeled with a “G.” The identified glycopeptide is DMEGELGPEEPLTT(GalNAc)QQPR.

Scheme 4.

Illustration of the fragmentation shown in Fig. 5.

In summary, we successfully identified 26 unambiguous O-glycosylation sites, 21 of which are novel. In four additional cases the information obtained was not sufficient to identify the precise site bearing the modification (the complete list is in Table III; associated product ion spectra are in Figs. 3–5 and supplemental Figs. 1–29). These belong to 12 different proteins with various functions such as binding and transport (apolipoproteins and fetuins), enzymes or enzyme inhibitors (pantetheinase, inter-α-trypsin inhibitor, and plasma serine protease inhibitor), cell signaling factors (insulin-like growth factor II), and proteins involved in blood coagulation (kininogen-1, fibrinopeptide, and fibronectin). None of these are low level proteins in serum. However, a rough estimation is that glycosylation sites identified in the present study belong to proteins that are 2–3 orders of magnitude less abundant than serum albumin in fetal serum.

Table III. Summary of all glycosylation sites identified.

| Identity | Name | Sitea | Evidenceb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETD(3) | ETD(2) | ETD(1) | CID | |||

| P01044 | Kininogen-1 precursor | Thr136c | + | |||

| Ser581 | + | |||||

| P02676 | Fibrinogen β chain precursor (contains fibrinopeptide B) | Thr4 | + | |||

| P07456 | Insulin-like growth factor II precursor | Ser95/97or Thr98/99d (one of these 4 residues) | + | |||

| Thr106 | + | |||||

| Ser154 | + | |||||

| Thr163 | + | + | + | |||

| P07589 | Fibronectin | Thr280 | + | |||

| P12763 | α2-HS-glycoprotein precursor | Ser296e | + | + | ||

| Thr334 | + | + | ||||

| Ser341f | + | + | + | |||

| P17690 | β2-Glycoprotein 1 precursor | Thr33 | + | |||

| P19035 | Apolipoprotein C-III precursor | Ser90 or Thr92g | + | |||

| Thr92 orSer94 | + | |||||

| Q03247 | Apolipoprotein E precursor | Thr32 | + | |||

| Thr211h | + | + | ||||

| Thr309 | + | + | ||||

| Ser310 | + | |||||

| Q0VCM5 | Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H1 precursor | Ser643 | + | |||

| Thr648i | + | + | + | |||

| Q3T052 | Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 precursor | Ser683 | + | + | ||

| Ser686 or Thr688 | + | + | ||||

| Thr705 | + | + | ||||

| Thr706 | + | + | + | |||

| Thr708 | + | + | + | |||

| Q58CQ9 | Pantetheinase precursor | Thr504 | + | |||

| Q58D62 | Fetuin-B precursor | Thr292 | + | |||

| Thr295 | + | + | ||||

| Q9N2I2 | Plasma serine protease inhibitor precursor | Thr35 | + | + | + | |

| Thr36 | + | |||||

aNormal text, sites previously known; italics, sites previously uncharacterized in bovine but reported in human; bold, new sites previously unreported.

bThe modifying carbohydrate group is: ETD(3), GalNAcGalSA; ETD(2), GalNAcGal; ETD(1) and CID, GalNAc.

cSee Ref. 46.

dHuman protein, P01344, is listed as modified at Thr99, which may correspond to the same position in the bovine sequence (47).

eSee Ref. 33.

fSee Ref. 48.

hHuman protein, P02649, is listed as modified at this conserved site (Thr212) in the Swiss-Prot database; no reference provided.

Prediction tools especially tailored to mucin type O-glycosylation have been developed previously. For instance, NetOGlyc (51) considers primary sequence, surface accessibility, secondary structure information, and distance constraints for prediction of glycosylation. This software predicted 10 of the 26 sites identified unambiguously in the present study. The CKSAAP-OGlySite software (52) predicted correctly 7 of the 26 identified glycosylation sites with higher false positive rates compared with NetOGlyc.

The first step in O-glycan synthesis is the transfer of a GalNAc unit from UDP-GalNAc to the protein. At least 21 enzymes, polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases are known to be able to perform this job (2). All these enzymes utilize the same donor substance but may display differential preferences for protein substrates. Thus, it is not surprising that no consensus sequence(s) for O-glycosylation has been determined. Nonetheless there have been attempts to identify sequence motifs for O-glycosylation (53). There are structural features that seem to be preferential for this modification. Most notably, modification sites are located in Ser/Thr-rich surroundings featuring Pro residues. There is speculation that the Pro residues help to expose the Ser/Thr residues for efficient glycosylation. We tested these predictions with the glycosylation sites determined in our study. To uncover any patterns in preferential O-glycosylation within our data set, a symmetrical window of 16 flanking amino acids surrounding the modification sites was interrogated. The frequency of occurrence of these amino acids within flanking sequences was compared with that of the precursor proteins. Increased observation of Pro residues was noted around modification sites with a proline over-representation factor of 2.7 (16.4% frequency around glycosylation sites compared with 6.2% in the full protein sequences). A small over-representation of the combined Ser and Thr content was also observed, but this increment was within one standard deviation of the average of our data. All these observations are in good agreement with previous results (53).

An interesting observation within our data set was that more than half of the glycosylation sites identified are located in the proximity of one of the termini of the protein. For example, the observed glycosylation sites in apolipoprotein C and pantetheinase precursor are both close to the C terminus. Although some of the identified sites seem to be somewhere in the middle of the unprocessed protein sequence, post-translational processing of signal and presequences means that the location of the modification is in fact proximal to the terminus of the processed mature protein. For example, Thr99 and Thr106 of insulin-like growth factor II precursor (Swiss-Prot accession no. P07456) are located near the N terminus of the E-peptide. Similarly all the identified glycosylation sites in inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 precursor (Q3T052) are in the middle of the translated sequence. However, the human homolog of this protein, Q14624, undergoes further processing to generate two separate inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chains, giving one 70-kDa and one 35-kDa protein. The bovine sequence shows close homology to its human counterpart (>70% identity); thus it is reasonable to assume that the bovine preprotein undergoes similar processing. Using the human sequence as a predictive template for the likely sites of cleavage in the mature bovine protein, the newly identified modification sites would lie near the N terminus of the shorter chain. Without a larger data set, we cannot yet make a comprehensive prediction of the likelihood of O-glycosylations to cluster adjacent to protein termini.

CONCLUSIONS: SHORTCOMINGS AND ADVANTAGES

Glycoproteins and glycopeptides have previously been enriched by lectin affinity chromatography. Jacalin has been used for larger scale O-glycopeptide enrichment in a prior study (18). However, in that study, the carbohydrates were removed prior to mass spectrometry analysis by oxidative elimination. Because no diagnostic signs remain at the previously modified residues after such deglycosylation, there is no direct evidence that the peptides identified had been glycosylated. In fact, based on our experience, the degree of nonspecific binding observed in jacalin enrichment is significant. Numerous unmodified peptides were identified in our study even after enrichment at both the protein and peptide level. Moreover in a few cases the same sequences were detected both glycosylated and unmodified (fetuin (P12763) residues 334–348, 330–348, and 334–349). Thus, without direct detection of a carbohydrate-modified peptide, one cannot confirm that a glycopeptide was isolated by jacalin affinity chromatography.

Once the glycopeptides were isolated it became obvious that there is no simple paradigm for their full structural characterization. In most instances, CID analysis is only suitable for confirming the presence of glycopeptides. Although ion traps permit the automated setup of MS3 experiments, one cannot suggest a universal linked scan approach for O-linked glycopeptide analysis because CID analysis of the most abundant MS/MS products will lead to further carbohydrate losses. ETD offers a more successful alternative. However, even with relatively small carbohydrate structures, the low charge density represents an obstacle for efficient ETD fragmentation. Limited fragmentation may prevent the site assignment or even identification of the glycopeptide. Nonspecific proteolytic cleavage due to proteolytic activity in serum and sugar fragmentation further confound data interpretation. There are some potential solutions, each of which is worthy of investigation. With shorter trypsinolysis time, i.e. with more missed cleavages, longer peptides may be created. The larger number of basic residues present in peptides thus generated will increase the charge density and thus improve the ETD fragmentation efficiency. There are two potential pitfalls for this approach. (i) Partial digestion may not improve the charge density, particularly in cases where glycosylation sites are clustered and the adjacent sequences are therefore modified. (ii) Most database searching algorithms do not consider fragment ions bearing charge states higher than 2+; they will therefore not assign such ions, and thus the peptide matching will achieve a lower score and lower confidence. Using a hybrid LTQ-Orbitrap instrument, ETD fragments may also be measured at high resolution and subsequently processed to generate a deconvoluted peak list. With this approach, one has to consider that ion transmission of products from the ion trap to the Orbitrap currently leads to significantly decreased sensitivity. However, the newest LTQ-Orbitrap Velos may solve this problem (54). The solution presented within this study, i.e. partial enzymatic removal of the oligosaccharide moieties, showed a strong improvement in the detection of multiply modified species. Even following partial deglycosylation, ETD fragmentation efficiency is still frequently insufficient to yield confident identification/site localization. A recent study has reported improved quality of ETD product ion spectra following proteolysis using an endoprotease cleaving selectively in front of Lys residues (55). This is an approach that will be further investigated for its general utility in glycopeptide analysis.

Where good quality mass spectrometric data were obtained, ProteinProspector v5.2.1 updated for ETD fragmentation, was used for database searching. We found that a 1.2 Da mass deviation had to be permitted for the product ions, to accommodate the alternate formation of z+1 and c−-1· products (56). Consideration of the formation of these alternate fragments, a unique feature of this search engine, permitted lowering the mass tolerance to 0.6 Da. Introducing weighting factors for the different fragment ions also improved spectral assignments of ETD data (41). However, manual evaluation of the data was still essential. Development of a software package that could combine information obtained during the mass survey (permitting the identification of metal adducts), CID, and ETD experiments would be beneficial to this and other studies.

We present a practical and useful method for deciphering GalGalNAc core glycosylation from serum samples. More extensive fractionation of the samples and the application of different proteolytic enzymes will yield more, confidently assigned modification sites. A reliable catalog of such sites will undoubtedly lead to the development of more reliable modeling and prediction tools and eventually to better understanding of the biological function of the O-glycosylation of serum proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Andor Udvardy of the Biological Research Center, Szeged, Hungary; Drs. Kai Scheffler and Martin Zeller of Thermo Fischer Scientific; and David A. Maltby of the University of California San Francisco for technical assistance. We are very grateful to Dr. Sarah Hart and Dr. Robert J. Chalkley for correcting our “Hunglish.”

Footnotes

* This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RR001614 and RR019934 from the National Center for Research Resources (to the University of California San Francisco Mass Spectrometry Facility; director, A. L. Burlingame). This work was also supported by Hungarian Science Foundation Grant OTKA T60283 (to K. F. M.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.mcponline.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–32 and Tables 1 and 2.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.mcponline.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–32 and Tables 1 and 2.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- ECD

- electron capture dissociation

- AGC

- automatic gain control

- CV

- column volume

- ETD

- electron transfer dissociation

- Hex

- hexose

- HexNAc

- N-acetylhexosamine

- LTQ

- linear ion trap

- SA

- sialic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apweiler R., Hermjakob H., Sharon N. (1999) On the frequency of protein glycosylation, as deduced from analysis of the SWISS-PROT database. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1473, 4– 8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varki A., Cummings R. D., Esko J. D., Freeze H. H., Stanley P., Bertozzi C. R., Hart G. W., Etzler M. E. (2009) Essentials of Glycobiology, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofsteenge J., Müller D. R., de Beer T., Löffler A., Richter W. J., Vliegenthart J. F. (1994) New type of linkage between a carbohydrate and a protein: C-glycosylation of a specific tryptophan residue in human RNase Us. Biochemistry 33, 13524– 13530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart G. W. (1997) Dynamic O-linked glycosylation of nuclear and cytoskeletal proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem 66, 315– 335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartmann S., Hofsteenge J. (2000) Properdin, the positive regulator of complement, is highly C-mannosylated. J. Biol. Chem 275, 28569– 28574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pless D. D., Lennarz W. J. (1977) Enzymatic conversion of proteins to glycoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 74, 134– 138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuzmanov U., Jiang N., Smith C. R., Soosaipillai A., Diamandis E. P. (2009) Differential N-glycosylation of kallikrein 6 derived from ovarian cancer cells or the central nervous system. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 791– 798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medzihradszky K. F., Besman M. J., Burlingame A. L. (1997) Structural characterization of site-specific N-glycosylation of recombinant human factor VIII by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem 69, 3986– 3994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyagarajan K., Lipniunas P. H., Townsend R. R., Forte J. G. (1997) The N-linked oligosaccharides of the beta-subunit of rabbit gastric H,K-ATPase: Site localization and identification of novel structures. Biochemistry 36, 10200– 10212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersch-Björkman Y., Thomsson K. A., Holmén Larsson J. M., Ekerhovd E., Hansson G. C. (2007) Large scale identification of proteins, mucins, and their O-glycosylation in the endocervical mucus during the menstrual cycle. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 708– 716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blomme B., Van Steenkiste C., Callewaert N., Van Vlierberghe H. (2009) Alteration of protein glycosylation in liver diseases. J. Hepatol 50, 592– 603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drake R. R., Schwegler E. E., Malik G., Diaz J., Block T., Mehta A., Semmes O. J. (2006) Lectin capture strategies combined with mass spectrometry for the discovery of serum glycoprotein biomarkers. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 1957– 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lis H., Sharon N. (1993) Protein glycosylation. Structural and functional aspects. Eur. J. Biochem 218, 1– 27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe J. B., Marth J. D. (2003) A genetic approach to mammalian glycan function. Annu. Rev. Biochem 72, 643– 691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varki A. (1993) Biological roles of oligosaccharides: all of the theories are correct. Glycobiology 3, 97– 130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calvano C. D., Zambonin C. G., Jensen O. N. (2008) Assessment of lectin and HILIC based enrichment protocols for characterization of serum glycoproteins by mass spectrometry. J. Proteomics 71, 304– 317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vosseller K., Trinidad J. C., Chalkley R. J., Specht C. G., Thalhammer A., Lynn A. J., Snedecor J. O., Guan S., Medzihradszky K. F., Maltby D. A., Schoepfer R., Burlingame A. L. (2006) O-Linked N-acetylglucosamine proteomics of postsynaptic density preparations using lectin weak affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 923– 934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durham M., Regnier F. E. (2006) Targeted glycoproteomics: Serial lectin affinity chromatography in the selection of O-glycosylation sites on proteins from the human blood proteome. J. Chromatogr. A 1132, 165– 173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hortin G. L. (1990) Isolation of glycopeptides containing O-linked oligosaccharides by lectin affinity chromatography on jacalin-agarose. Anal. Biochem 191, 262– 267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hägglund P., Bunkenborg J., Elortza F., Jensen O. N., Roepstorff P. (2004) A new strategy for identification of N-glycosylated proteins and unambiguous assignment of their glycosylation sites using HILIC enrichment and partial deglycosylation. J. Proteome Res 3, 556– 566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kieliszewski M. J., O’Neill M., Leykam J., Orlando R. (1995) Tandem mass spectrometry and structural elucidation of glycopeptides from a hydroxyproline-rich plant cell wall glycoprotein indicate that contiguous hydroxyproline residues are the major sites of hydroxyproline O-arabinosylation. J. Biol. Chem 270, 2541– 2549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvarez-Manilla G., Atwood J., 3rd, Guo Y., Warren N. L., Orlando R., Pierce M. (2006) Tools for glycoproteomic analysis: size exclusion chromatography facilitates identification of tryptic glycopeptides with N-linked glycosylation sites. J. Proteome Res 5, 701– 708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsen M. R., Højrup P., Roepstorff P. (2005) Characterization of gel-separated glycoproteins using two-step proteolytic digestion combined with sequential microcolumns and mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 4, 107– 119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen M. R., Jensen S. S., Jakobsen L. A., Heegaard N. H. (2007) Exploring the sialiome using titanium dioxide chromatography and mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 1778– 1787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y., Jeppsson J. O., Jörntén-Karlsson M., LinnéLarsson E., Jungvid H., Galaev I. Y., Mattiasson B. (2002) Application of shielding boronate affinity chromatography in the study of the glycation pattern of haemoglobin. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci 776, 149– 160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mallia A. K., Hermanson G. T., Krohn R. I., Fujimoto E. K., Smith P. K. (1981) Preparation and use of a boronic acid affinity support for separation and quantitation of glycosylated hemoglobins. Anal. Lett 14, 649– 661 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sparbier K., Wenzel T., Kostrzewa M. (2006) Exploring the binding profiles of ConA, boronic acid and WGA by MALDI-TOF/TOF MS and magnetic particles. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci 840, 29– 36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H., Li X. J., Martin D. B., Aebersold R. (2003) Identification and quantification of N-linked glycoproteins using hydrazide chemistry, stable isotope labeling and mass spectrometry. Nat. Biotechnol 21, 660– 666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christensen B., Kazanecki C. C., Petersen T. E., Rittling S. R., Denhardt D. T., Sørensen E. S. (2007) Cell type-specific post-translational modifications of mouse osteopontin are associated with different adhesive properties. J. Biol. Chem 282, 19463– 19472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Müller S., Alving K., Peter-Katalinic J., Zachara N., Gooley A. A., Hanisch F. G. (1999) High density O-glycosylation on tandem repeat peptide from secretory MUC1 of T47D breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem 274, 18165– 18172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peter-Kataliniæ J. (2005) O-Glycosylation of proteins. Methods Enzymol 405, 139– 171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medzihradszky K. F., Gillece-Castro B. L., Settineri C. A., Townsend R. R., Masiarz F. R., Burlingame A. L. (1990) Structure determination of O-linked glycopeptides by tandem mass spectrometry. Biomed. Environ. Mass Spectrom 19, 777– 781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medzihradszky K. F., Gillece-Castro B. L., Townsend R. R., Burlingame A. L., Hardy M. R. (1996) Structural elucidation of O-linked glycopeptides by high energy collision-induced dissociation. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 7, 319– 328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seipert R. R., Dodds E. D., Lebrilla C. B. (2009) Exploiting differential dissociation chemistries of O-linked glycopeptide ions for the localization of mucin-type protein glycosylation. J. Proteome Res 8, 493– 501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zubarev R. A., Horn D. M., Fridriksson E. K., Kelleher N. L., Kruger N. A., Lewis M. A., Carpenter B. K., McLafferty F. W. (2000) Electron capture dissociation for structural characterization of multiply charged protein cations. Anal. Chem 72, 563– 573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Syka J. E., Coon J. J., Schroeder M. J., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F. (2004) Peptide and protein sequence analysis by electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 101, 9528– 9533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Good D. M., Wirtala M., McAlister G. C., Coon J. J. (2007) Performance characteristics of electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 1942– 1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perdivara I., Petrovich R., Allinquant B., Deterding L. J., Tomer K. B., Przybylski M. (2009) Elucidation of O-glycosylation structures of the beta-amyloid precursor protein by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry using electron transfer dissociation and collision induced dissociation. J. Proteome Res 8, 631– 642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kjeldsen F., Haselmann K. F., Budnik B. A., Sørensen E. S., Zubarev R. A. (2003) Complete characterization of posttranslational modification sites in the bovine milk protein PP3 by tandem mass spectrometry with electron capture dissociation as the last stage. Anal. Chem 75, 2355– 2361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McAlister G. C., Berggren W. T., Griep-Raming J., Horning S., Makarov A., Phanstiel D., Stafford G., Swaney D. L., Syka J. E., Zabrouskov V., Coon J. J. (2008) A proteomics grade electron transfer dissociation-enabled hybrid linear ion trap-orbitrap mass spectrometer. J. Proteome Res 7, 3127– 3136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chalkley R. J., Thalhammer A., Schoepfer R., Burlingame A. L. (2009) Identification of protein O-GlcNAcylation sites using electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry on native peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 106, 8894– 8899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Medzihradszky K. F., Chalkley R. J., Trinidad J. C., Michaelevski A., Burlingame A. L. (2008) The utilization of Orbitrap higher collision decomposition device for PTM analysis and iTRAQ-based quantitation, in 56th ASMS Conference on Mass Spectrometry, Denver, June 1–5, 2008, American Society for Mass Spectrometry, Santa Fe, NM [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tachibana K., Nakamura S., Wang H., Iwasaki H., Tachibana K., Maebara K., Cheng L., Hirabayashi J., Narimatsu H. (2006) Elucidation of binding specificity of Jacalin toward O-glycosylated peptides: quantitative analysis by frontal affinity chromatography. Glycobiology 16, 46– 53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deutsch H. F. (1954) Fetuin: the mucoprotein of fetal calf serum. J. Biol. Chem 208, 669– 678 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mormann M., Paulsen H., Peter-Kataliniæ J. (2005) Electron capture dissociation of O-glycosylated peptides: radical site-induced fragmentation of glycosidic bonds. Eur. J. Mass. Spectrom 11, 497– 511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sueyoshi T., Miyata T., Hashimoto N., Kato H., Hayashida H., Miyata T., Iwanaga S. (1987) Bovine high molecular weight kininogen. The amino acid sequence, positions of carbohydrate chains and disulfide bridges in the heavy chain portion. J. Biol. Chem 262, 2768– 2779 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hudgins W. R., Hampton B., Burgess W. H., Perdue J. F. (1992) The identification of O-glycosylated precursors of insulin-like growth factor II. J. Biol. Chem 267, 8153– 8160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pisano A., Jardine D. R., Packer N. H., Redmond J. W., Williams K. L., Gooley A. A., Farnsworth V., Carson W., Cartier P. (1996) Identifying sites of glycosylation in proteins, in Techniques in Glycobiology ( Townsend R. R., Hotchkiss A. T., Jr.) pp. 299–320, Marcel Dekker, New York [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maeda H., Hashimoto R. K., Ogura T., Hiraga S., Uzawa H. (1987) Molecular cloning of a human apoC-III variant: Thr 74→Ala 74 mutation prevents O-glycosylation. J. Lipid Res 28, 1405– 1409 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Olsen E. H., Rahbek-Nielsen H., Thogersen I. B., Roepstorff P., Enghild J. J. (1998) Posttranslational modifications of human inter-alpha-inhibitor: identification of glycans and disulfide bridges in heavy chains 1 and 2. Biochemistry 37, 408– 416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Julenius K., Mølgaard A., Gupta R., Brunak S. (2005) Prediction, conservation analysis, and structural characterization of mammalian mucin-type O-glycosylation sites. Glycobiology 15, 153– 164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Y. Z., Tang Y. R., Sheng Z. Y., Zhang Z. (2008) Prediction of mucin-type O-glycosylation sites in mammalian proteins using the composition of k-spaced amino acid pairs. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson I. B., Gavel Y., von Heijne G. (1991) Amino acid distributions around O-linked glycosylation sites. Biochem. J 275, 529– 534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nielsen M. L., Cox J., Olsen J. V., Mann M. (2009) An unbiased tale of in vitro modifications: in-depth analysis of artifacts caused by proteomics sample preparation, in 57th ASMS Conference on Mass Spectrometry, Philadelphia, May 31–June 4, 2009, American Society for Mass Spectrometry, Santa Fe, NM [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taouatas N., Drugan M. M., Heck A. J., Mohammed S. (2008) Straightforward ladder sequencing of peptides using a Lys-N metalloendopeptidase. Nat. Methods 5, 405– 407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bakken V., Helgaker T., Uggerud E. (2004) Models of fragmentations induced by electron attachment to protonated peptides. Eur. J. Mass Spectrom 10, 625– 638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.