Abstract

Objectives To develop a new methodology to systematically compare evidence across diverse risk markers for coronary heart disease and to compare this evidence with guideline recommendations.

Design “Horizontal” systematic review incorporating different sources of evidence.

Data sources Electronic search of Medline and hand search of guidelines.

Study selection Two reviewers independently determined eligibility of studies across three sources of evidence (observational studies, genetic association studies, and randomised controlled trials) related to four risk markers: depression, exercise, C reactive protein, and type 2 diabetes.

Data extraction For each risk marker, the largest meta-analyses of observational studies and genetic association studies, and meta-analyses or individual randomised controlled trials were analysed.

Results Meta-analyses of observational studies reported adjusted relative risks of coronary heart disease for depression of 1.9 (95% confidence interval 1.5 to 2.4), for top compared with bottom fourths of exercise 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0), for top compared with bottom thirds of C reactive protein 1.6 (1.5 to 1.7), and for diabetes in women 3.0 (2.4 to 3.7) and in men 2.0 (1.8 to 2.3). Prespecified study limitations were more common for depression and exercise. Meta-analyses of studies that allowed formal Mendelian randomisation were identified for C reactive protein (and did not support a causal effect), and were lacking for exercise, diabetes, and depression. Randomised controlled trials were not available for depression, exercise, or C reactive protein in relation to incidence of coronary heart disease, but trials in patients with diabetes showed some preventive effect of glucose control on risk of coronary heart disease. None of the four randomised controlled trials of treating depression in patients with coronary heart disease reduced the risk of further coronary events. Comparisons of this horizontal evidence review with two guidelines published in 2007 showed inconsistencies, with depression prioritised more in the guidelines than in our review.

Conclusions This horizontal systematic review pinpoints deficiencies and strengths in the evidence for depression, exercise, C reactive protein, and diabetes as unconfounded and unbiased causes of coronary heart disease. This new method could be used to develop a field synopsis and prioritise future development of guidelines and research.

Introduction

Clinical guidelines for the prevention of coronary heart disease are important not only because they influence practice but also because they present a highly cited collation of evidence for a multitude of risk markers.1 2 For example, the European primary prevention guidelines published in 20031 mentioned more than 40 risk markers and have been cited more than 800 times.

A fundamental problem in developing rational clinical guidelines has been the lack of explicit, systematic comparisons of the strength of causal evidence across the diverse range of risk markers, which compete for clinical attention. Traditional vertical systematic reviews, which focus on one risk marker or a relatively homogeneous group of related risk markers, are an important influence on the development of clinical guidelines. However, individual risk markers may be championed by different experts, with few attempts at harmonising, displaying, and comparing the evidence across different markers. This may contribute to an ad hoc selection not based on strength of causal evidence, of which risk markers beyond smoking, blood pressure, and cholesterol concentration are included in guidelines. The European guidelines,1 for example, did not consider atrial fibrillation, unlike the contemporaneous American guidelines.2 The large3 and expanding array of risk markers underscores the importance of this problem, particularly since many of the markers are of uncertain causal relevance and few yet provide targets for prevention of disease.

We developed a new methodology of horizontal systematic review to assess causal relevance across a range of risk markers. We provide a high level overview of synthesised evidence, based on explicit criteria of biases and causal relevance. To show the potential of this approach we focused on four risk markers: depression, exercise, C reactive protein, and diabetes. We selected these four markers because they differ in several respects, including conceptual domain (psychosocial marker, behavioural marker, circulating biomarker, defined metabolic disease), measurement properties (presence or absence of standard instruments and internationally agreed definitions), and whether exposure was endogenous (proximal in the putative causal pathway) or exogenous (more distal). We purposively selected one risk marker—diabetes—widely accepted as having an established causal role, as well as three markers where the causal role is not universally accepted. We hypothesised that concordance of research evidence from differing research designs each with different sources of error provides the strongest evidence on the causal relevance of a putative risk factor.4 Specifically, we sought evidence from three major study designs that offer different approaches to tackling confounding and reverse causation: traditional prospective observational studies with multivariate adjustments, studies that use genetic variants as instruments to tackle confounding (so called Mendelian randomisation),5 6 and randomised controlled trials where exposure to the risk marker is experimentally manipulated. Finally, in the light of the horizontal comparison we compared the recommendations made for these four risk markers in the most recent guidelines on prevention of coronary heart disease.

Methods

The horizontal systematic review assesses causal relevance across a range of risk markers and study designs. We set out a priori eligibility criteria for studies, systematically obtained the studies, and extracted and displayed the data. Firstly, we separated information on risk markers for first coronary heart disease events in people initially free from clinical disease and prognostic factors in patients with existing coronary heart disease because of the clinical importance of distinguishing between primary and secondary prevention. Secondly, where more than one systematic review was identified we displayed the largest meta-analysis or study (which tended to be better quality according to the MOOSE,7 and QUORUM8 statements) in the tables of main results and included details of the others in the web extra appendix. Thirdly, we agreed a priori that if we could find no systematic review for any randomised controlled trials of the risk marker then we would review the largest individual study. Fourthly, we stratified data extraction and synthesis by study design (observational studies, genetic association studies, and randomised controlled trials), but analysed horizontally.

Observational studies

In January 2008 we searched Medline to identify meta-analyses of observational studies in healthy populations (aetiologic) and among patients with existing coronary disease (prognostic), and contacted experts. Existing coronary disease included patients with myocardial infarction or those undergoing coronary revascularisation or coronary angiography. Search terms included the expanded medical subject heading (MESH) of cardiovascular disease, meta-analysis as a MESH topic or publication type, and then the four individual risk markers as either the MESH term or text words. English and non-English language publications were eligible. Eligible outcomes were fatal coronary heart disease and non-fatal myocardial infarction (aetiologic and prognostic studies) and, for prognostic studies only, all cause mortality. Meta-analyses were only eligible for inclusion if they reported summary estimates based on longitudinal studies.

Two reviewers (HK and AAS) extracted data, with recourse to a third reviewer in the event of disagreement. We extracted summary data on prespecified items: age adjusted (or unadjusted) relative risks with 95% confidence intervals; adjusted relative risks with 95% confidence intervals; number of studies adjusting for smoking, blood pressure, and cholesterol concentration (aetiologic) or disease severity (prognostic); attenuation between age and multivariate adjusted relative risks; the prevalence of exposure in individual studies; the methods used to measure exposure; the number and type of outcomes; the level of meta-analysis (literature only, or pooled analysis of individual participant data across the studies); measure of heterogeneity; whether separate estimates were reported among people aged over 75 years, women, or non-Western populations; evidence of the presence of a dose-response relation—that is, extending beyond dichotomous comparisons; the extent to which the duration of follow-up influenced the strength of the estimates (if effects are stronger with shorter periods of follow-up this is consistent with reverse causality); and evidence of publication bias.

Genetic studies

We searched for meta-analyses of the associations between genotype and each of the four individual risk markers through Medline using gene as the MESH term or text words or Mendelian in any field; meta-analysis as a MESH topic or publication type; and then the four individual risk markers as either the MESH term or text words. To identify meta-analyses of the association between genotype and coronary heart disease outcome we searched individual single nucleotide polymorphisms in all fields identified from recent systematic reviews for depression (SLC6A4, MTHFR, APOEw1), the CRP gene,w2 and type 2 diabetes (TCF7L2, FTO, CDKN2A/CDKN2B, PPARG, ICF2BP2, KCNJ11, HHEXIDE, CDKAL1, SLC30A8w3) together with expanded MESH headings of cardiovascular disease and meta-analysis as a MESH topic or publication type. For each variant two independent reviewers (HH and AN) extracted information on prespecified items: whether the single nucleotide polymorphism was identified from genome wide scans, the number of outcome events, the number of studies in the meta-analysis, unadjusted relative risks (95% confidence intervals), and whether there was a formal test on the use of the genetic variant as an instrumental variable.6

Randomised trials

Randomised controlled trials and meta-analyses of these were identified through searches of Medline. Search terms included the MESH heading of coronary heart disease or CHD or myocardial infarction or MI; trial as a MESH heading; the four individual risk markers as either the MESH term or text words; and meta-analysis or systematic review as a MESH heading or review as a publication type. Given the importance of evidence from randomised controlled trials to inform guidelines, we accepted individual trials where no meta-analyses were available. We also searched through the reference list from the guideline publications to identify relevant randomised controlled trials. Only randomised controlled trials that reported coronary heart disease event outcomes were eligible (aetiologic and prognostic studies) or death in the setting of patients with coronary heart disease (prognostic studies). Two independent reviewers (HK and AAS) extracted details on the nature of the intervention, the number of studies in the meta-analysis, the number and type of end points, the relative risk (95% confidence interval) of coronary heart disease or death, and whether the intervention had an effect on the risk marker.

Selection of guidelines

To make contemporaneous comparisons with our evidence review we included guidelines only published in 2007 as this was the most recent information available to us. We identified two guidelines, which were developed through independent processes, from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network9 and the fourth Joint European Societies10 11 (coordinated by the European Society of Cardiology, and representing nine professional organisations). Across each guideline and risk marker we compared the evidence cited, description of the causal relevance of the marker, recommendations on measurement in healthy population settings, inclusion in risk scores, recommendations for specific interventions, and target levels or goals for risk marker levels.

Results

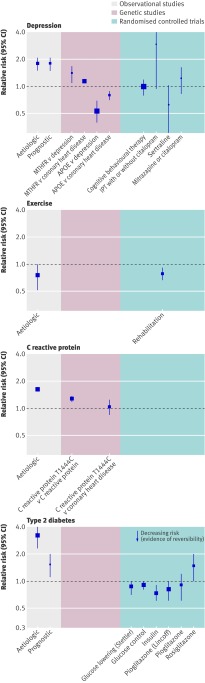

The figure shows the results of the meta-analyses of observational studies, genetic variants, and randomised controlled trials for depression, exercise, C reactive protein, and diabetes in relation to risk of coronary heart disease. These risk markers differed noticeably in the type and amount of evidence identified.

Meta-analyses of observational studies, genetic variants, and randomised controlled trials for depression, exercise, C reactive protein, and diabetes in relation to risk of coronary heart disease. IPT=interpersonal psychotherapy

Observational studies

Table 1 summarises the largest meta-analyses found for each of the risk markers. Meta-analyses of observational studies reported adjusted aetiologic relative risks of coronary heart disease for depression of 1.9 (95% confidence interval 1.5 to 2.4; 1262 events in 11 studies), for top compared with bottom fourth of exercise of 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0; 500 events in three studies), for top compared with bottom third of C reactive protein of 1.6 (1.5 to 1.7; 7068 events in 22 studies), and for diabetes in women of 3.0 (2.4 to 3.7) and in men of 2.0 (1.8 to 2.3; >4964 events in 29 studies). Meta-analyses of the association in patients with coronary heart disease (prognostic studies) reported an adjusted relative risk of further coronary heart disease events or death for depression of 1.6 (1.3 to 1.9; >525 events in 11 studies) and an adjusted relative risk of cardiac death for diabetes of 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0; 240 events in four studies). No prognostic meta-analyses were identified for the effect of exercise or C reactive protein on outcome among patients with coronary heart disease. A dose-response effect was reported for intensity of physical activity but not consistently for major depression compared with minor depression, concentration of C reactive protein, or glucose control in people with diabetes. None of the meta-analyses reported effects separately among those older than 75 years (or other age groups of older people), and only for diabetes was there evidence of consistent effects in non-Western populations. Effect estimates for C reactive protein and diabetes were presented separately for men and women, with observational evidence for diabetes showing a stronger association with coronary heart disease among women than among men. No sex differences were found for the association of C reactive protein with coronary heart disease. The exercise meta-analysis was restricted to women and the depression meta-analysis did not report effects separately in women and men.

Table 1.

Indicators of causal relevance and potential bias in meta-analyses of observational studies of depression, exercise, C reactive protein concentration, and diabetes in relation to coronary heart disease

| Variables | Depression | Exercise | C reactive protein | Type 2 diabetes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy population | Patients with coronary heart disease | Healthy population | Patients with coronary heart disease | Healthy population | Patients with coronary heart disease | Healthy population | Patients with coronary heart disease (stents) | ||||

| Outcomes | Non-fatal myocardial infarction or fatal coronary heart disease | Death | Coronary heart disease | Death or coronary heart disease | Coronary heart disease | Death or coronary heart disease | Fatal coronary heart disease | Death, repeat revascularisation, or myocardial infarction | |||

| Comparison | Depression v no depression | Depression v no depression | Top fourth v bottom fourth | Top third v bottom third | Diabetes mellitus v no diabetes mellitus | Diabetes mellitus v no diabetes mellitus | |||||

| Largest meta- analysis | Nicholson 2006w10 | Nicholson 2006w10 | Oguma 2004w11 | Danesh 2004w12 | Huxley 2000w13 | Lee 2006w14 | |||||

| Level of data source | Literature | Literature | Literature | New data and literature | Literature | Pooled data | |||||

| No of outcome events | 4016 | 1867 | 500 | 7068 | >8261 | 240 | |||||

| No of studies in meta-analysis | 22 | 34 | 3 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 37 | 4 | |||

| Measurement of exposure | Scale=16*; antidepressant=4; doctor diagnosed=2 | Scale=34† | Leisure time physical activity=2; total physical activity=1 | 22/22 studies used high sensitivity C reactive protein assay methods | NR | History of diabetes requiring current treatment with insulin, oral agents, or dietary therapy | |||||

| Prevalence of exposure (%) | 2-50 | 2-51 | 25 | 33 | 1-48 | 21 | |||||

| Age adjusted or unadjusted relative risk (95% CI) | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.1); subset of 21 studies with 3990 events | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.1); subset of 31 studies with 1719 events | NR | NR | Women: 3.7 (2.6 to 5.2); men: 2.2 (1.8 to 2.6); subset of 22 studies, events NR | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) | |||||

| Adjusted relative risk (95% CI) | 1.9 (1.5 to 2.4); subset of 11 studies with 1262 events | 1.6 (1.3 to 1.9); subset of 11 studies with >525 events | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.7) | Women: 3.0 (2.4 to 3.7); men: 2.0 (1.8 to 2.3); subset of 29 studies with >4964 events | 1.5 (1.1 to 2.0) | |||||

| No of studies adjusted for smoking/cholesterol concentration and blood pressure (causal) or disease severity (prognostic) | 4/22 | 13/34; relative risk reduced from 2.2 (1.6 to 3.0) to 1.5 (1.1 to 2.1) after adjustment for left ventricular function | 1/3 | 20/22 reported adjustment for smoking and “some other established risk markers” | 26/37 | 4/4 Adjustment for disease severity | |||||

| Heterogeneity I2 (%) (any markers that explain) | 52 (Measurement instrument) | 54 | NR | 54 (year of publication) | Women 74; men 43 | Not applicable (pooled data) | |||||

| Older people (≥75) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||||

| Women | NR | NR | Only women | Effect similar in women and men | Effect stronger in women | NR | |||||

| Non-Western populations | Studies lacking | Studies lacking | Studies lacking | Studies lacking | Yes | No | |||||

| Effect changes with duration of follow-up | Yes; stronger effects with shorter follow up | NR | No | No | NR | ||||||

| Length of follow-up (years) | 3-37 | 0.25-15 | 7 | 3-20 | 4-36 | 5 | |||||

| Publication bias | Present (Egger’s test39 P=0.08) | Present (Egger’s test P=0.01) | No evidence (Egger’s test P=0.45) | Not formally investigated | No evidence (Egger’s test) | NR | |||||

| Dose response | Evidence for dose response: stronger association for clinical depression (2.3, 1.8 to 3.1) than depressive symptom scale (1.7, 1.4 to 2.0) | No evidence for dose response: weaker association for clinical depression (1.4, 0.8 to 2.5) than depressive symptom scale (1.9, 1.6 to 2.3) | NS (P=0.20) | NR | NR | NR | |||||

NR=not reported.

*General wellbeing schedule=2, Center for Epidemiological Studies depression scale=5, diagnostic interview schedule=2, geriatric depression scale=1, Zung self rating depression scale=1, general health questionnaire/present state examination=1, general health questionnaire=1, Hamilton rating scale=1, symptom=1, Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory—depression=1.

†Center for Epidemiological Studies depression scale=6, Zung self rating depression scale=4, Millon=3, Becks depression inventory alone=6, Becks depression inventory combined=3, diagnostic interview schedule=2, own=2, cognitive behaviour assessment=1, schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia=1, Hamilton rating scale for depression=1, depression anxiety stress scales=1, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders=1, interview=1, hospital anxiety and depression scale=1, amitryptiline=1.

Confounding—Adjustments for a priori confounders of smoking, blood pressure, and cholesterol concentration were found in four of 22 aetiologic studies for depression and coronary heart disease and one of three studies for physical activity. Adjustments in the C reactive protein studies (20/22) and diabetes studies (26/37) were generally more consistent and complete, although beyond smoking it was unclear which variables were included in multivariate analyses. For aetiological meta-analyses of the four risk markers, the effect on coronary heart disease was apparent after multivariable adjustments. Reporting of unadjusted or age adjusted and multivariate adjusted results was inconsistent.

Biases—Statistical heterogeneity, present in all the meta-analyses, was partly attributable to differences in measurement of exposure for depression and physical activity, and year of publication for C reactive protein. Depression was defined by 12 different methods, but relatively standardised methods were used for measurement of C reactive protein concentration and diabetes. For depression, but not for C reactive protein or diabetes, stronger effects were observed with shorter follow-up. Adjustment for severity of coronary heart disease in prognostic studies reduced the relative risk for depression by 45%. Evidence of small study bias (often indicative of publication bias or a strong association between methodological weakness and a non-null association in the expected direction in smaller studies compared with larger studies) was present for depression but absent for physical activity, diabetes, and C reactive protein.

Other meta-analyses of observational studies—The findings of the meta-analyses of observational studies included in our analysis were consistent with results of other eligible meta-analyses on this subject (see web extra appendix). For depression, adjusted relative risks ranged between 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) and 1.9 (1.5 to 2.4). Similarly, a consistently strong association was found between diabetes and the incidence and mortality after coronary heart disease, with stronger relations identified for women than for men. Exercise was consistently protective for coronary heart disease, ranging from 0.5 (0.5 to 0.6) to 0.8 (0.6 to 1.2). Other meta-analyses confirmed the increased risk for coronary heart disease for people in the highest third of C reactive protein concentrations.

Genetic evidence

Table 2 summarises the results of our search for meta-analyses of genetic variants, indexing differences in the risk markers of interest. Meta-analyses for two genetic variants were identified, which have been investigated in relation to both depression and coronary heart disease: MTHFR12 and APOE.13 14 The MTHFR variant was positively associated with both depression and coronary heart disease, whereas the ε2 APOE genotype was linked to a reduced risk of depression and of coronary heart disease.12 15 w4 No replicated genetic variant for physical activity was identified that could be assessed in relation to coronary heart disease. We identified two syntheses of a genetic variant in the CRP gene in which the expected relation for coronary heart disease events under a causal model, in the light of its effect on C reactive protein levels, was not observed.16 w2 Despite the large number of meta-analyses showing genes associated with diabetes, none examined the association of these variants with coronary heart disease.

Table 2.

Genetic variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) associated with risk marker (depression, exercise, C reactive protein, and diabetes) and coronary heart disease in healthy populations

| Variable | MTHFR C677T (TT v CC) rs1801133 | APOE carriers (ε2 v ε3/3) | No SNPs | CRP T1444C rs1130864 (TT v any C) | 8 SNPs identified in recent review* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Depression | Coronary heart disease | Depression ε2 v ε3 allele | Coronary heart disease ε2 carriers v ε3/3 | Exercise | C reactive protein | Coronary heart disease | Type 2 diabetes | Coronary heart disease | ||

| SNP identified from genome wide scans | No | No | No | No | — | No | No | Yes | Not same as for type 2 diabetes | ||

| Largest meta-analysis | Gilbody 2007w15 | Lewis 2005w4 | Lopez-Leon 2008w1 | Bennett 2007w16 | — | Lawlor 2008w2 | Lawlor 2008w2 | Jafar-Mohammadi 2008w3 | — | ||

| No of outcome events | 1280 | 26 000 | 827 | 21 331 | — | NA | 4610 | >6700 | — | ||

| No of studies in meta-analysis | 10 | 80 | 7 | 17 | — | 5 | 5 | 5 reports (each with multiple replication studies) | — | ||

| Unadjusted relative risk (95% CI) | 1.36 (1.11 to 1.67) | 1.14 (1.05 to 1.24) | 0.51 (0.39 to 0.68) | 0.80 (0.70 to 0.90) | 1.21 (1.09 to 1.43) (geometric weighted mean difference) | 1.01 (0.74 to 1.38)† | Range 1.12-1.37 | — | |||

| Instrumental variable test* | NA | NA | NA | NA | — | Null finding (underpowered) | Null finding (underpowered) | NA | NA | ||

NA=not available.

*Testing whether risk marker is associated with coronary heart disease to extent it is associated with genetic variant—that is, exploiting part of phenotypic variation which is not related to potential confounding markers. A positive finding supports causality whereas a null finding suggests that observed association between risk marker and coronary heart disease may be confounded or due to reverse causality.

†Adjusted estimate.

Randomised controlled trials

We identified four randomised controlled trials of different interventions for the treatment of depression among patients with coronary heart disease (table 3). None of these trials showed a beneficial effect on death or cardiovascular events.w5-w8 No randomised controlled trials were identified on the effect of treating depression in healthy populations (or on the effect of prevention of depression) in relation to risk of coronary heart disease. No randomised controlled trials were found of interventions that specifically increased physical activity (in isolation from, for example, improvements in diet, or compliance with drugs) in healthy populations, whereas exercise based rehabilitation reduced the risk of mortality among people with coronary heart disease (0.7, 0.6 to 1.0).w9 Currently there are no interventions that specifically lower C reactive protein levels, and hence no randomised controlled trials that could test the causal importance of C reactive protein in coronary heart disease. Randomised controlled trials (four meta-analyses and 70 individual trials) of different hypoglycaemic agents in patients with diabetes without or with manifest coronary heart disease provided some, but not consistent, support that lowering glucose concentrations reduced the rate of coronary heart disease events.w17-w21

Table 3.

Randomised trials of interventions that alter depression, exercise, C reactive protein, and glycaemic control and their effects on coronary heart disease events

| Depression | Exercise | C reactive protein | Type 2 diabetes | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Sertraline | CBT, group therapy | Mitrazapine or citalopram | IPT or citalopram | None | Exercise only | None | None | Glucose control | Pioglitazone | Rosiglitazone | Glucose control (various) | Pioglitazone | ||||

| Population | Healthy | Coronary heart disease plus depression | Coronary heart disease plus depression | Coronary heart disease plus depression | Coronary heart disease plus depression | Healthy | Coronary heart disease | Healthy | Coronary heart disease | Type 2 diabetes | Type 2 diabetes | Type 2 diabetes | Type 2 diabetes | Type 2 diabetes plus coronary heart disease | |||

| Outcomes | — | Death | Death | Coronary heart disease | Cardiovascular disease event | Coronary heart disease | Death | Coronary heart disease | Death | Non-fatal myocardial infarction or death from coronary heart disease | Myocardial infarction | Myocardial infarction | Cardiac event | Death | |||

| RCT or MA | — | RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT | 0 | MA | 0 | 0 | MA | MA | MA | MA | RCT | |||

| No of studies in meta-analysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 19 | 42 | 6 | 0 | |||

| Reference | — | Sadheartw6 | ENRICHDw5 | MIND-ITw8 | CREATEw7 | — | Jolliffe 2005w9 | — | — | Huang 2001w17 | Lincoff 2007w18 | Nissen 2007w19 | Stettler 2006w20 | Erdmann 2007w21 | |||

| No of outcome events | — | 7 | 340 | 42 | 12 | — | 215 | — | — | NR | 290 | 158 | 1,197 | 176 | |||

| Unadjusted effect on outcome relative risk (95% CI) | — | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.0) | 1.5 (0.4 to 6.9) | — | 0.7 (0.6 to 1.0) | — | — | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.0) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.0) | 1.4 (1.0 to 2.0) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.2) | |||

| Intervention effect on risk marker | — | Sertraline significantly superior to placebo on CGI-I scale but not on HAM-D scale | Significant but modest reduction in depression with intervention | No difference in prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms | Citalopram effective, but no additional impact of IPT | — | NR | — | — | Fasting plasma glucose and HbA1C lower in intervention than control groups | NR | NR | HbA1C lower after intervention in all six studies | Significant impact on lowering HbA1C | |||

CBT=cognitive behavioural therapy; CG-I=clinical global impression improvement scale; HAM-D=Hamilton depression; IPT=interpersonal psychotherapy; MA=meta-analysis; RCT=randomised controlled trial; NR=not reported.

Guidelines

Neither the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network nor the European guidelines adopted an explicit method for displaying and comparing evidence across risk markers (table 4). The Scottish but not European guidelines reported a level of evidence for some statements. Both guidelines made clear, albeit differing, statements on the importance of depression in the onset and progression of coronary heart disease. Neither the only randomised trial with statistical power to detect differences in event rates (ENRICHD)w5 nor the Cochrane meta-analysis of psychological interventions17 was cited in the executive summary of the European guidelines. Post hoc subgroup analyses were cited.18 The Scottish guidelines cited neither trials nor meta-analyses but did cite a previous position statement, which itself cites only an older narrative systematic review. Neither guideline suggested that C reactive protein was an important risk marker: for the Scottish guidelines it was neither mentioned nor any rationale given as to why not. Observational studies and Mendelian randomisation studies were cited for the European guidelines meta-analyses, and the association was stated as “often seriously confounded.”

Table 4.

Guideline recommendations for primary prevention of coronary heart disease in relation to depression, exercise, C reactive protein, and diabetes in fourth Joint European Societies10 11 and Scottish Intercollegiate Network (SIGN) guidelines9 (both published in 2007)

| Variables | Depression | Exercise | C reactive protein | Diabetes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4th Joint European Societies | SIGN | 4th Joint European Societies | SIGN | 4th Joint European Societies | SIGN | 4th Joint European Societies | SIGN | |

| Meta-analyses and trials cited | Observational: Rugulies 2002,w22 Wulsin 2003,w23 Barth 2004w24; Trials MA: Rees 2004,w25 Linden 1996,w26 Dusseldorp 1999w27 | Observational: nil; trials: Rees 2004w25 | Observational: nil; trials: nil | Observational: nil; trials: nil | Observational: Danesh 2004w12: trials: nil | Observational: nil; trials: nil | Observational: nil; trials: UKPDSw28 | Observational: nil; trials: nil |

| Description of causal relevance | “Increasing scientific evidence that psychosocial factors (including depression) contribute independently to the risk of CHD [coronary heart disease]” (E26) | “strong and consistent evidence . . . independent risk factor” (p43); evidence level 2++ | “A lack of regular physical activity may contribute to the early onset and progression of CVD [cardiovascular disease]” (E19) | “independent risk factor” (p16); level of evidence 2++ | “seriously confounded” (E28) | Not included in guideline (and no rationale for exclusion) | No clear statement but referred to EASD guidelines (E25) | “Important risk factor” (p4) |

| Measurement recommended in opportunistic assessment of healthy populations | Yes: “Assess all patients for psychosocial risk factors” (E27) | No clear statement: “Depression…should be taken into account when assessing individual risk” (p44) | Yes: “Assessment . . . core task[s] for physicians and other health workers” (E20) | No | No | — | No clear statement | Yes: “Glucose should be measured when assessing cardiovascular risk” and “risk should be estimated at least once every five years in adults over the age of 40” (p9) |

| Method of measurement recommended | Yes: “clinical interview or standardised questionnaires”; two screening questions are proposed (E27) | No | Yes: ”Brief interview concerning . . physical activity at work and leisure”; no specific standardised instrument recommended (S38) | No | No | — | No | Yes: random glucose in all; if ≥6.1 but ≤7 mmol/l then fasting glucose if ≥7.0 mmol/l then glucose tolerance test |

| Use in risk prediction scores* | No | No (but social deprivation is included) | No (but a “key element of risk evaluation”) (E19) | No | No: “Contribution to risk estimation generally modest”) (E11) | — | No | Yes: presence or absence of diabetes |

| Interventions | Yes: “Prescribe multimodal, behavioural intervention, integrating individual or group counselling for psychosocial risk markers and coping with stress and illness. Refer to a specialist in case of clinically significant emotional distress” (E27) | No: “No clear evidence that treating depression is effective” (p43); “Smokers with CHD and comorbid clinical depression should have their depression treated both for alleviation of depressive symptoms and to increase the likelihood of stopping smoking” (p21) | Yes: “Professional advice about the intensity, duration and frequency of exercise” (S40) | Not described (national guidance cited) | None | — | Yes | No: hypoglycaemic agents not discussed |

| Goals for risk marker change | None | None | Yes: “30 minutes of moderately vigorous exercise on most days of the week will reduce risk” (E19) | Yes: “All adults should accumulate 30 minutes of moderate intensity activity on most days of the week” (p17); level of evidence 4 | No | — | Yes: in all to achieve “Blood glucose <6 mmol/l”; “More rigorous risk factor control in high risk subjects: fasting blood glucose <6 mmol/l and HbA1C <6.5% if feasible” (E9) | No |

UKPDS=United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study; EASD=European Society for Diabetes.

E=executive summary page number; S=full text page number. Levels of evidence used in SIGN: 2++=high quality systematic reviews of case-control or cohort studies; high quality case-control studies or cohorts with low risk of confounding or bias and high probability that relation is causal; 4=expert opinion.

*Assessing cardiovascular risk using SIGN guidelines to assign preventive treatment (ASSIGN score) in SIGN and HeartScore in fourth Joint European Societies.

Discussion

The horizontal systematic review is a new method to compare the evidence on diverse risk markers in a unified explicit framework of the largest available syntheses of the most important forms of evidence. This approach highlighted differences and deficiencies in the evidence of causal relevance across the four selected risk markers: psychosocial, behavioural, biomarker, and metabolic disease. The evidence that depression, low physical activity, or C reactive protein concentration causes coronary heart disease seems less strong than that for diabetes. Randomised trials of specific interventions are lacking for C reactive protein and null for depression, and although they support the role of exercise in the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease they are not available to test the causal hypothesis. Neither the European nor Scottish guidelines gave explicit criteria for assessing evidence to enable prioritisation of the impact of individual risk markers. However the emphasis given to the causal and clinical relevance of depression in the guidelines was inconsistent with the available evidence.

Closing the translational gap

Discordance exists between the large number of markers that are associated with coronary heart disease3 and the small number of targets for intervention. This highlights the need for our approach, which aims to prioritise targets. Our approach is horizontal in two senses: a comparison was made across diverse markers and a comparison was made across different forms of evidence. We selected four risk markers as examples; the approach is scaleable to all risk markers.

Three complementary designs for obtaining causal evidence

Associations between putative risk markers and coronary heart disease are easy to show in observational studies but may be confounded, as has been shown by negative trials of hormone replacement therapy and vitamins on coronary heart disease.19 We marshalled three approaches, which aimed, with varying limitations, to mimic the ideal, unconfounded experiment; prospective observational studies (multivariate adjustment for confounders), genetic studies (which utilise genetic variants that influence the modifiable exposure and that are assigned at random and can therefore be used as an instrument for the unconfounded and unbiased association of the genetic variant with the outcome of interest), and randomised trials (where the investigator influences exposure). Low density lipoprotein cholesterol provides an example with converging evidence from all these approaches: robust associations between high concentrations of low density lipoprotein cholesterol and coronary heart disease shown in observational cohort studies20; genetic variants that relate to lower concentrations of low density lipoprotein cholesterol (for example, in PCSK9,21 the APOE,22 and LDL receptor gene)23 also found to be associated with a reduced risk of coronary heart disease; and trials on low density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering confirmed the protection against coronary heart disease.24 We excluded study designs that may be associated with lower validity, such as individual observational studies that have not (yet) been synthesised, non-randomised trials, and studies on biological mechanisms. Such studies have been the basis for guideline recommendations.25 We included the forms of large scale evidence, which aims to evaluate the causal hypothesis, with a low tolerance for false positive findings. Our approach could be extended to incorporate small scale experimental studies in humans (as part of a “teleoanalysis” approach)26 and, with due caveats,27 experimental studies in animals. Such extensions to other forms of evidence should acknowledge that studies in the discovery phase have a higher tolerance for false positive findings, as the aim is not to abandon a potentially important risk marker prematurely.28

Observational evidence

Risk markers were associated with relative risks from 1.5 (C reactive protein) to over 3 (diabetes), but adjustment for established risk factors of smoking, blood pressure, and cholesterol concentration was least common among studies of depression and exercise. These psychosocial (depression) and behavioural (exercise) factors were also more prone to information biases, with multiple instruments used to determine exposure. There was evidence of reverse causality and publication bias for depression. We found no meta-analyses in a prognostic setting of C reactive protein or exercise. Given that the guidelines make recommendations in secondary prevention and since aetiological markers may not necessarily be prognostic, this lack of synthesised evidence is important. Thus, for example, meta-analyses of body mass index in the prognosis of patients with coronary disease suggest no adverse effect for obesity,29 whereas those for aetiological associations show an increased risk.30

Genetic evidence

Genetic studies using Mendelian randomisation have been more frequently applied to assessing C reactive protein31 w2 than for our other three risk factors. Despite being relatively underpowered, the emerging evidence does not suggest an important role for C reactive protein in causing coronary heart disease. A new and large collaboration should provide a more definitive answer in the near future.32 For depression, exercise, and diabetes, evidence from Mendelian randomisation for their causal role in risk of coronary heart disease was limited. The robust positive associations of MTHFR with both depression and coronary heart disease could indicate a causal effect of depression on coronary heart disease but is more likely to reflect folate intake and metabolism as a causal marker for both outcomes. The emergence of whole genome association studies and complete genome sequencing is improving our understanding of the genomic architecture underlying complex traits. Mendelian randomisation may offer a powerful tool to understand causality, particularly for risk marker traits that are controlled by a limited number of genetic variants of relatively strong effect.

Randomised controlled trials

Successful treatment of depression in patients with established coronary heart disease in randomised controlled trials does not show benefits in subsequent death or rates of coronary heart disease events. This provides no support for the causal hypothesis that avoiding depression is important in the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease, but it is a matter of debate whether it provides evidence against. For example, it might be argued that it is the intervention rather than the hypothesis that is wrong. Trials were lacking for the effect of C reactive protein concentration or physical activity among healthy populations, whereas there was evidence that glucose control may provide some reduction in coronary heart disease events. Interpretation was difficult in the situation of trials with pleiotropic effects; for instance, the evidence that exercise in combination with other aspects of rehabilitation reduced the risk of death among patients with coronary heart disease.w9 A new specific C reactive protein inhibitor drug is being used to determine the functions of C reactive protein in the experimental setting and will be tested in the setting of acute coronary events. However, the lack of oral bioavailability and short half life currently precludes its use in long term prevention trials in humans.33 Randomised controlled trials of lipid lowering statins are a non-specific test of the role of C reactive protein and coronary heart disease, because of the major effect on low density lipoprotein concentrations.34 It has been shown that false findings from observational studies continue to be influential, despite being contradicted by randomised trial evidence.35 Null randomised trials have led to revisions in the causal and mechanistic hypotheses—for example, the finding that positive inotropic agents do not prolong life in heart failure, refocused attention away from a mainly haemodynamic model of heart failure.36

Clinical implications and consistency of the guidelines

By using horizontal systematic reviews, clinicians, guideline developers, funders of research, public health policy makers, and journal editors and their peer reviewers might be aided in making more consistent and less biased decisions. The graphical summary of evidence may serve a practical purpose in guideline groups, facilitating more explicit debate of the importance of risk markers across the multiple fields of interest of contributors. The two most recent guidelines on primary prevention of cardiovascular disease refer to a wide “penumbra” of risk markers beyond smoking, blood pressure, and cholesterol concentration; over 50 markers in the most recent European guidelines.1 The guidelines cite more than 1100 references (joint societies) and 315 references (Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network) but do not provide a systematic comparison of the quality or strength of evidence across the risk markers that were included. There was inconsistency in the conclusions reached by the two guidelines across the four risk markers that we evaluated. For instance, C reactive protein was not considered by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network. Depression was accorded higher prominence in the European guidelines than in the Scottish guidelines and within the European guidelines was accorded higher prominence than C reactive protein, which is not consistent with the evidence in the horizontal systematic review. Depression is worth treating in its own right, irrespective of any causal relation with coronary heart disease; but the same is true for other conditions, such as chronic obstructive airways disease, which are not mentioned in the guidelines.

Limitations of this horizontal systematic review

There are important limitations in this initial illustration of a horizontal systematic review. Firstly, the method depends on the availability and quality of large scale syntheses of evidence. These are more commonly available for blood based markers than for behavioural or psychosocial markers; horizontal systematic reviews may stimulate research groups to raise or defend the profile of research in their subdisciplines. A range of measures of effect were included in the reviews, and where the confidence intervals for the effect estimates were wide this precluded reaching firm conclusions. Increasing use of horizontal systematic reviews may provide an impetus to improving the number and quality of meta-analyses, particularly those using individual participant data. Secondly, the horizontal systematic review is narrative, without novel methods for data analysis, offering no explicit ranking of causal relevance nor attempting to posit a decision threshold above which a marker might be considered causal.

Research implications and need for unbiased field synopses

Further research is required to develop the method of horizontal systematic review. Firstly, methods could be developed to derive relative weights of evidence building on the judgments of groups of experts,37 Bayesian methods could be used for the synthesis of evidence, or models could be developed to combine features from different studies to derive quantitative estimates.38 Secondly, extension is required to the whole range of risk markers that are included in guidelines, thus providing a systematic synopsis of the specialty. Thirdly, extension to other chronic diseases should be explored—for example, in the specialty of cancer, horizontal systematic reviews could build on the assessment of causality used by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. Fourthly, horizontal systematic reviews should be regularly updated as evidence changes to minimise the lag time between the generation of evidence and the development of guidelines and could take advantage of continually updated databases of genetic studies in this process. The conclusions of our review are not altered if the publication year of evidence is truncated two years before the publication of guidelines—that is, 2005. Fifthly, there are important considerations beyond causal relevance when developing guidelines, such as economic considerations and the additional deleterious effects of the risk markers (for example, the impact of depression on quality of life), and the framework could be extended to encompass these considerations. Sixthly, it should be noted that non-causal markers can be used in risk prediction (for example, socioeconomic position) and this requires distinct consideration in the observational evidence.

Conclusion

Horizontal systematic review in which the causal relevance of diverse risk markers is compared in an explicit framework helps clarify the relative standing of each risk marker. Field synopses, expanded to include the whole range of risk markers considered of potential clinical or public health relevance, should be developed to prioritise research efforts and to focus recommendations on those markers most likely to be causal.

What is already known on this topic

Diverse psychosocial, behavioural, and biological markers are claimed to be independently associated with coronary heart disease and are included in guidelines

Traditional vertical systematic reviews focus on one risk marker and one research design at a time

Horizontal comparisons across different types of risk markers, incorporating different research designs each with differing limitations, are lacking

What this study adds

Observational evidence from horizontal systematic review was strongest for diabetes and C reactive protein concentration as risk markers for coronary heart disease

Evidence from Mendelian randomisation was present for C reactive protein only, which did not support a causal association with coronary heart disease

Randomised trial evidence was lacking for C reactive protein and did not show a protective effect in coronary heart disease from treating depression; for no risk marker did it provide strong support for the causal hypothesis

This work was developed during meetings of the Nucleus of Epidemiology and Public Health, European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, European Society of Cardiology in Paris 2007 and Sofia Antipolis 2008 (HH chair, members GC, JED, PH, XJ, SM, BMM, SS, TT, JCMW, ADH, and DAL).

Contributors: The writing group included HK, AN, MK, and HH. HK, AN, and MK contributed equally to the study. HK, HH, AN, and AAS carried out the searches and extracted the data. All authors took part in the discussion group where the new methodology was developed, commented on early drafts of the manuscript through to revisions, approved the final draft, had full access to all the data, and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: MK is supported by the Academy of Finland. HK is supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust. DAL is supported by a UK Department of Health Career Scientist Award and works in a centre that receives support from the UK Medical Research Council. ADH is supported by a British Heart Foundation senior research fellowship (FS 05/125).

Competing interests: ADH is a member of the editorial board of Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin and has acted as an adviser to GlaxoSmithKline and London Genetics. He has received honorariums for speaking at educational meetings sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry and has donated all or most of these to charity.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data are available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b4265

References

- 1.De Backer G, Ambrosioni E, Borch-Johnsen K, Brotons C, Cifkova R, Dallongeville J, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Third Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1601-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearson TA, Blair SN, Daniels SR, Eckel RH, Fair JM, Fortmann SP, et al. AHA guidelines for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke: 2002 update: consensus panel guide to comprehensive risk reduction for adult patients without coronary or other atherosclerotic vascular diseases. American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Circulation 2002;106:388-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hopkins PN, Williams RR. A survey of 246 suggested coronary risk factors. Atherosclerosis 1981;40:1-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shrier I, Boivin JF, Steele RJ, Platt RW, Furlan A, Kakuma R, et al. Should meta-analyses of interventions include observational studies in addition to randomized controlled trials? A critical examination of underlying principles. Am J Epidemiol 2007;166:1203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. ‘Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JA, Timpson N, Davey Smith G. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med 2008;27:1133-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses. Lancet 1999;354:1896-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scottish Intercollegiate Network. Risk estimation and the prevention of cardiovascular disease. In: SIGN, ed. Edinburgh: SIGN, 2007.

- 10.Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, Boysen G, Burell G, Cifkova R, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary. Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007;14(suppl 2):E1-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, Boysen G, Burell G, Cifkova R, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: full text. Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007;14(suppl 2):S1-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klerk M, Verhoef P, Clarke R, Blom HJ, Kok FJ, Schouten EG. MTHFR 677C-->T polymorphism and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2002;288:2023-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez Leon S, Croes EA, Sayed-Tabatabaei FA, Claes S, Van Broeckhoven C, van Duijn CM. The dopamine D4 receptor gene 48-base-pair-repeat polymorphism and mood disorders: a meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57:999-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopez-Leon S, Janssens AC, Gonzalez-Zuloeta Ladd AM, Del-Favero J, Claes SJ, Oostra BA, et al. Meta-analyses of genetic studies on major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2008;13:772-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song Y, Stampfer MJ, Liu S. Meta-analysis: apolipoprotein E genotypes and risk for coronary heart disease. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:137-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casas JP, Shah T, Cooper J, Hawe E, McMahon AD, Gaffney D, et al. Insight into the nature of the CRP-coronary event association using Mendelian randomization. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:922-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rees K, Bennett P, West R, Davey SG, Ebrahim S. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(2):CD002902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneiderman N, Saab PG, Catellier D, Powell LH, DeBusk R, Williams RB. Psychosocial treatment within sex by ethnicity subgroups in the enhancing recovery in coronary heart disease clinical trial. Psychosom Med 2004;66:475-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawlor DA, Davey Smith G, Kundu D, Bruckdorfer KR, Ebrahim S. Those confounded vitamins: what can we learn from the differences between observational versus randomised trial evidence? Lancet 2004;363:1724-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, et al. Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet 2007;370:1829-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH Jr, Hobbs HH. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1264-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bennet AM, Di Angelantonio E, Ye Z, Wensley F, Dahlin A, Ahlbom A, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E genotypes with lipid levels and coronary risk. JAMA 2007;298:1300-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linsel-Nitschke P, Gotz A, Erdmann J, Braenne I, Braund P, Hengstenberg C, et al. Lifelong reduction of LDL-cholesterol related to a common variant in the LDL-receptor gene decreases the risk of coronary artery disease—a Mendelian randomisation study. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005;366:1267-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO 3rd, Criqui M, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2003;107:499-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wald NJ, Morris JK. Teleoanalysis: combining data from different types of study. BMJ 2003;327:616-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perel P, Roberts I, Sena E, Wheble P, Briscoe C, Sandercock P, et al. Comparison of treatment effects between animal experiments and clinical trials: systematic review. BMJ 2007;334:197-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Alexiou GA, Gouvias TC, Ioannidis JP. Medicine. Life cycle of translational research for medical interventions. Science 2008;321:1298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romero-Corral A, Montori VM, Somers VK, Korinek J, Thomas RJ, Allison TG, et al. Association of bodyweight with total mortality and with cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease: a systematic review of cohort studies. Lancet 2006;368:666-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogers RP, Bemelmans WJ, Hoogenveen RT, Boshuizen HC, Woodward M, Knekt P, et al. Association of overweight with increased risk of coronary heart disease partly independent of blood pressure and cholesterol levels: a meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies including more than 300 000 persons. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1720-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kivimaki M, Lawlor DA, Davey Smith G, Kumari M, Donald A, Britton A, et al. Does high C-reactive protein concentration increase atherosclerosis? The Whitehall II Study. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e3013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Danesh J, Erqou S, Walker M, Thompson SG, Tipping R, Ford C, et al. The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration: analysis of individual data on lipid, inflammatory and other markers in over 1.1 million participants in 104 prospective studies of cardiovascular diseases. Eur J Epidemiol 2007;22:839-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM, Tennent GA, Gallimore JR, Kahan MC, Bellotti V, et al. Targeting C-reactive protein for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Nature 2006;440:1217-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Casas JP, Shah T, Hingorani AD, Danesh J, Pepys MB. C-reactive protein and coronary heart disease: a critical review. J Intern Med 2008;264:295-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tatsioni A, Bonitsis NG, Ioannidis JP. Persistence of contradicted claims in the literature. JAMA 2007;298:2517-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz AM. Pathophysiology of heart failure: identifying targets for pharmacotherapy. Med Clin North Am 2003;87:303-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hemingway H, Chen R, Junghans C, Timmis A, Eldridge S, Black N, et al. Appropriateness criteria for coronary angiography in angina: reliability and validity. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:221-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mouchart M, Russo F, Wunsch G. Structural modelling, exogeneity, and causality. In: Engelhardt H, Kohler HP, Prskwetz A, eds. Causal analysis in population studies: concepts, methods, applications. Dordrecht: Springer, 2008.

- 39.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]