Abstract

AIM: To evaluate serum neopterin levels and their correlations with liver function tests and histological grade in children with hepatitis-B-related chronic liver disease.

METHODS: The study population comprised 48 patients with chronic active hepatitis B, 32 patients with hepatitis-B-related active liver cirrhosis and 40 normal controls. Serum neopterin was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

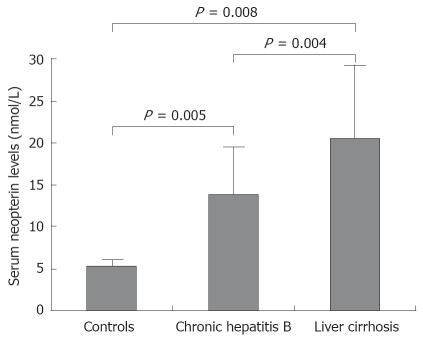

RESULTS: The mean ± SD serum neopterin levels were 14.2 ± 5.6 nmol/L in patients with chronic hepatitis, 20.3 ± 7.9 nmol/L in patients with liver cirrhosis and 5.2 ± 1.4 nmol/L in control group. Serum neopterin levels were significantly higher in patients with chronic hepatitis (P = 0.005) and cirrhosis patients (P = 0.008), than in control subjects. Cirrhotic patients had significantly higher serum neopterin levels than patients with chronic hepatitis (P = 0.004). There was a positive correlation between serum neopterin levels and alanine aminotransferase levels in patients with chronic hepatitis (r = 0.41, P = 0.004) and cirrhotic patients (r = 0.39, P = 0.005). Positive correlations were detected between serum neopterin levels and inflammatory score in patients with chronic hepatitis (r = 0.51, P = 0.003) and cirrhotic patients (r = 0.49, P = 0.001).

CONCLUSION: Our results suggest that serum neopterin levels can be considered as a marker of inflammatory activity and severity of disease in children with hepatitis-B-related chronic liver disease.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, Chronic liver disease, Serum neopterin, Histological grade, Children

INTRODUCTION

Neopterin is a pteridine derivative produced by macrophages activated under the control of gamma-interferon and released from T-cells by the activation of the cellular immune system[1]. It has been demonstrated that there is a relation between neopterin levels in biological materials, the changes in their elimination rates and various pathological conditions. In addition to its association with activation of cell-mediated immunity and with cell expansion, significant changes were seen in neopterin levels and elimination rates in viral diseases (for example viral hepatitis)[2,3], atypical phenylketonuria[4], organ and tissue rejection[5], autoimmune diseases (such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus[6]), genital cancer and hematologic neoplastic disorders[7,8]. In all these cases, enhanced concentrations of neopterin have been shown to have prognostic significance[9].

In chronic active hepatitis, necrosis is observed as disseminated to the parenchyma and the perilobular consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The gamma-interferon released from T-lymphocytes in the area stimulates and activates macrophages[10]. Lymphocytic cell infiltration was shown, in addition to the macrophages within the fibrous bands in the liver of patients with cirrhosis resulting from various etiologies[11]. Thus, it is suggested that neopterin secreted from the inflammation-activated macrophages can be an indication of the inflammation in the liver in chronic liver diseases[10-12].

Studies in adult patients with acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis have shown that serum neopterin levels are elevated and this elevation is correlated with the severity of disease. However, there is no data about serum neopterin concentrations in children with chronic hepatitis B and liver cirrhosis. Therefore, we investigated serum neopterin concentrations in children with hepatitis-B-related chronic liver disease and correlated these concentrations with liver function tests and inflammatory activity of the liver. The aim of this study was to demonstrate a possible relationship between serum neopterin levels and severity of the disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study population comprised 48 patients with chronic active hepatitis B, 32 patients with hepatititis-B-related active liver cirrhosis and 40 normal controls. The control group consisted of otherwise healthy, age- and sex-matched children whose biochemical tests were also within normal limits. The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and all parents gave informed consent for the participation of their children in the study.

Chronic active hepatitis B was diagnosed on the basis of Hepatitis B surface antigen (HbsAg) and Hepatitis B e antigen (HbeAg) positivity in serum for a period over 6 mo, positive HBV-DNA determined at least twice in one-month intervals (> 5 pg/mL), and evidence of chronic active hepatitis B in a liver biopsy carried out within the last 6 mo. None of the patients in this group had Hepatitis C or Hepatitis D infections, decompensated liver disorder, autoimmune hepatitis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson disease or any other liver disease. The patients were evaluated before no treatment was initiated.

Hepatitis-B-related active liver cirrhosis was diagnosed by clinical, serological, and biochemical tests as well as histopathological investigation of liver biopsy. The cirrhotic patients were classified by the Child-Pugh classification defined by Pugh et al[13].

Liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), alkaline phosphase (AP) and albumin) were also performed in all subjects using an autoanalyzer.

Serum neopterin levels were examined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Neopterin ELISA, IBL Immuno-Biological-Laboratories, Hamburg).

All patients with chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis underwent liver biopsy. Liver biopsy was performed according to the Menghini technique. The biopsy material was kept in 10% formaldehyde solution and evaluated by a pathologist experienced in liver pathology. In the samples obtained from the patients with chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis, histological activity index (HAI) score was defined as suggested by Knodell et al[14] and modified by Desmet et al[15]. It was graded 0-18 by adding the scores for periportal ± bridging necrosis (0-10), intralobular degeneration and focal necrosis (0-4) and portal inflammation (0-4).

All data was shown in mean ± SD values. A Chi square test was used to analyze the categorical data, whereas an ANOVA test was used to compare the numerical data of the groups. The homogeneity of the intergroup variance was tested by the Levene method. If the variance was homogenous (P > 0.05), then the Tukey test was used, and if not (P > 0.05), then the Tamhane test was used to evaluate the significance of the difference between the groups. The correlations between serum neopterin levels and biochemical and histological parameters were determined by the Pearson correlation test. The differences between the groups were taken statistically significant if it is P < 0.05.

RESULTS

The characteristics of all the subjects are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the three groups in terms of sex and age. Serum neopterin levels (mean ± SD) were found to be 14.2 ± 5.6 nmol/L (range 2.7-32) in patients with chronic active hepatitis B, 20.3 ± 7.9 nmol/L (range 12-41) in patients with hepatitis-B-related active liver cirrhosis and 5.2 ± 1.4 nmol/L (range 2.2-6.8) in controls. Serum neopterin levels were significantly elevated in patients with chronic hepatitis B (P = 0.005) and liver cirrhosis (P = 0.008) than in healthy controls. Patients with liver cirrhosis had higher serum neopterin levels compared to patients with chronic hepatitis B (P = 0.008) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, biochemical and histological characteristics of all subjects (mean ± SD)

| Chronic hepatitis B | Liver cirrhosis | Control | |

| n | 48 | 32 | 40 |

| Sex (M/F) | 22/26 | 15/17 | 19/21 |

| Age (yr) | 8.2 ± 3.4 (2-17) | 7.4 ± 5.3 (1-16) | 7.1 ± 2.2 (2-16) |

| ALT (IU/L) | 68.8 ± 52.6 (14-280) | 108.9 ± 76.8 (24-240) | 26.1 ± 7 (14-36) |

| AST (IU/L) | 64.6 ± 51.4 (21-276) | 153.4 ± 147.6 (39-580) | 27.5 ± 6.7 (18-38) |

| GGT (IU/L) | 23.4 ± 21.6 (14-162) | 115.4 ± 30.3 (88-439) | 36.8 ± 8.8 (18-48) |

| AP (IU/L) | 528 ± 193.5 (199-1055) | 705.7 ± 487.4 (228-1851) | 167.1 ± 50.7 (98-240) |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 3.6 ± 0.7 (2.5-4.7) | 3.2 ± 1 (2-5.1) | 4.4 ± 0.6 (3.7-5.4) |

| Neopterin (nmol/L) | 14.2 ± 5.6 (2.7-32) | 20.5 ± 8.6 (13-38) | 5.2 ± 1.4 (2.2-6.8) |

| HAI | 6.2 ± 2.9 (1-12) | 9.1 ± 2.2 (5-12) | - |

Figure 1.

Serum neopterin levels in normal controls and patients with chronic hepatitis B and liver cirrhosis.

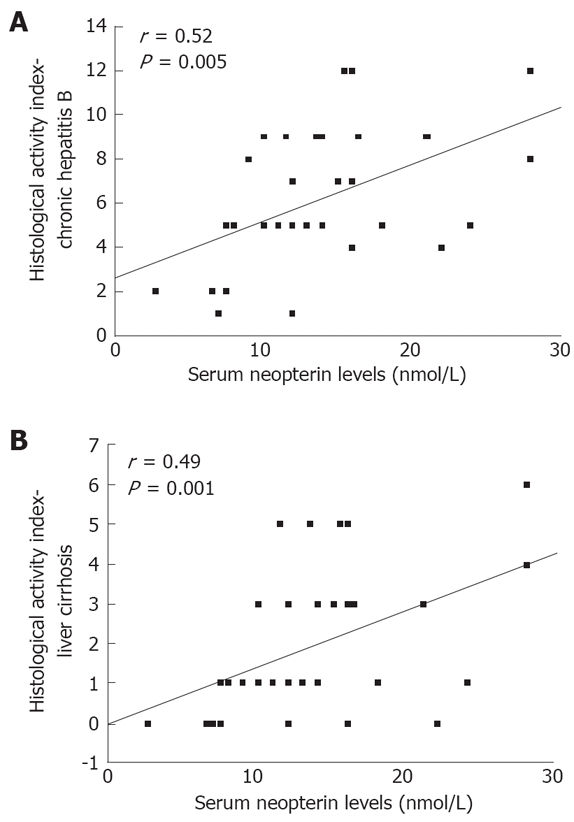

There was a positive significant correlation between serum neopterin levels and ALT levels (r = 0.41, P = 0.004). No significant correlations were found between serum neopterin levels and AST (r = 0.18, P = 0.22), GGT (r = 0.33, P = 0.07), AP (r = 0.09, P = 0.64), and albumin (r = -0.34, P = 0.06) levels in patients with chronic hepatitis B. A positive significant correlation was observed between neopterin levels and HAI (r = 0.52, P = 0.001) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Correlation between serum nopterin levels and histological activity index. A: Chronic hepatitis B; B: Hepatitis-B-related liver cirrhosis.

According to the Child-Pugh classification, all of the 32 patients with liver cirrhosis were in stage A. In the liver cirrhosis group, serum neopterin levels were significantly related to ALT values (r = 0.39, P = 0.005) and HAI (r = 0.49, P = 0.001) (Figure 2B). There were no correlations between serum neopterin levels and AST (r = 0.20, P = 0.517), GGT (r = 0.35, P = 0.263), AP (r = 0.09, P = 0.772), and albumin (r = -0.11, P = 0.731) levels.

DISCUSSION

It has been reported that neopterin levels increase in body fluids and change in parallel to the activity of the disease in many infectious diseases and various malign disorders in which activation of the cellular immune system plays an important role in the pathogenesis[7,16,17]. It has been shown that the activation of cellular immune system stimulates the secretion of γ-interferon from the T lymphocytes, and γ-interferon is an effective inducer of neopterin release by monocytes/macrophages[10]. Gamma-interferon is produced by the stimulation of T-lymphocytes by several specific antigens, primarily viral antigens, thus it was found that the neopterin levels were especially elevated in viral infections.[3,17].

Evidence of elevation in neopterin levels in body fluids due to the activation of immune system, which was also supported by several studies involved in diseases leading to activation of the immune system, suggests that elevated neopterin can also be a marker for the follow-up of chronic liver disorders, especially of viral liver disorders[9]. However, since no such data is available related to children, our results can only be compared to results obtained from the studies carried out with adult patients.

It is suggested that serum neopterin levels can be used as a significant parameter for the differential diagnosis of non-infectious hepatitis and viral hepatitis[18]. Serum neopterin levels of the patients with acute and chronic hepatitis B were found to be significantly higher than the donors’ serum. The relation between neopterin levels and severity of the disease has been proved, and it can be used in combination with clinical data as a prognostic evidence for the progress of the disease[19]. In asymptomatic HbsAg carriage, acute hepatitis, chronic inactive hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and alcoholic liver disease, serum and urine neopterin levels were found to be higher than in controls. The most elevated neopterin levels were seen in patients with acute hepatitis[20].

In adult patients with liver cirrhosis, serum neopterin levels were more elevated than non-cirrhotic patients and control groups[9,21] whereas out of non-cirrhotic patients, patients with chronic hepatitis B had also elevated neopterin levels[9].

Serum neopterin levels were elevated in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis[22]. Neopterin measurement was reported to be beneficial for the differential diagnosis of viral and alcoholic liver diseases, and it has been shown that patients with viral hepatitis had higher neopterin concentrations compared to patients with alcoholic liver diseases[20].

Serum and urine neopterin levels were elevated from baseline after the initiation of interferon therapy in HbeAg positive patients with chronic hepatitis B, and they remained markedly elevated during the treatment. However, the neopterin levels were restored rapidly to baseline values after the end of the therapy. Therefore it was suggested that serum and urine neopterin levels could be a good marker of the cellular immunity during interferon treatment in the chronic hepatitis B infection[23].

In our study, serum neopterin levels was found to be markedly higher in the pediatric patients with chronic hepatitis B and liver cirrhosis than in healthy controls, which is in agreement with the data obtained from the adult patients. It was also higher in patients with cirrhosis when compared with chronic hepatitis B patients. The patients in the cirrhotic stage, independent of their etiology, have elevated concentrations of serum neopterin levels released from the activated macrophages. In those patients, substances that are considered to stimulate the macrophages such as immune complexes or endotoxins, increase in blood due to the lack of peptide clearance by the liver[24]. These mechanisms explain the highest concentrations of serum neopterin in patients with cirrhosis.

Although no correlation was found between serum neopterin levels and ALT, AST and AP levels in adults with various chronic liver diseases of various etiologies, a negative correlation was found with albumin[9]. While neopterin levels were found correlated with liver function tests in patients with acute hepatitis, this correlation was not verified in patients with chronic liver diseases[20]. However, in other studies, a correlation was found between serum neopterin levels and biochemical tests or liver inflammatory grading in patients with chronic hepatitis C and B[9,25]. We found a significant correlation between serum neopterin levels and ALT or HAI in children with hepatitis-B-related chronic hepatitis B and liver cirrhosis. This data agrees with the data obtained from the adult patients.

In conclusion, these results suggest that measurement of serum neopterin levels can be considered as a marker of inflammatory activity and severity of disease in children with hepatitis-B-related chronic liver disease. However, this needs to be further studied in children.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Reza Malekzadeh, Professor, Director, Digestive Disease Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Shariati Hospital, Kargar Shomali Avenue, 19119 Tehran, Iran

S- Editor Li JL L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Rigby AS, Chamberlain MA, Bhakta B. Behcet's disease. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1995;9:375–395. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3579(05)80196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reibnegger G, Auhuber I, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Judmaier G, Prior C, Werner ER, Wachter H. Urinary neopterin levels in acute viral hepatitis. Hepatology. 1988;8:771–774. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denz H, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Huber H, Nachbaur D, Reibnegger G, Thaler J, Werner ER, Wachter H. Value of urinary neopterin in the differential diagnosis of bacterial and viral infections. Klin Wochenschr. 1990;68:218–222. doi: 10.1007/BF01662720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman S. Hyperphenylalaninaemia caused by defects in biopterin metabolism. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1985;8 Suppl 1:20–27. doi: 10.1007/BF01800655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bron D, Wouters A, Barekayo I, Snoeck R, Stryckmans P, Fruhling P. Neopterin: an useful biochemical marker in the monitoring of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Acta Clin Belg. 1988;43:120–126. doi: 10.1080/17843286.1988.11717919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reibnegger G, Egg D, Fuchs D, Gunther R, Hausen A, Werner ER, Wachter H. Urinary neopterin reflects clinical activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1063–1070. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abate G, Comella P, Marfella A, Santelli G, Nitsch F, Fiore M, Perna M. Prognostic relevance of urinary neopterin in non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Cancer. 1989;63:484–489. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890201)63:3<484::aid-cncr2820630316>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeitler HJ, Andondonskaja-Renz B. Evaluation of pteridines in patients with different tumors. Cancer Detect Prev. 1987;10:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilmer A, Nolchen B, Tilg H, Herold M, Pechlaner C, Judmaier G, Dietze O, Vogel W. Serum neopterin concentrations in chronic liver disease. Gut. 1995;37:108–112. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.1.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huber C, Batchelor JR, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Lang A, Niederwieser D, Reibnegger G, Swetly P, Troppmair J, Wachter H. Immune response-associated production of neopterin. Release from macrophages primarily under control of interferon-gamma. J Exp Med. 1984;160:310–316. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.1.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woloszczuk W, Troppmair W, Leiter E, Flener R, Schwarx M, Kovarik J, Pohanka E, Margreiter R, Huber C. Relationship of interferon-gamma and neopterin levels during stimulation with alloantigens in vivo and in vitro. Tranplantation. 1986;41:716–719. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas HC. Immunological mechanisms in chronic liver disease. In: Zakim D, Boyer TD, eds , editors. Hepatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990. pp. 1144–1126. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646–649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knodell RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, Chen TS, Craig R, Kaplowitz N, Kiernan TW, Wollman J. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology. 1981;1:431–435. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840010511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desmet VJ, Gerber M, Hoofnagle JH, Manns M, Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic hepatitis: diagnosis, grading and staging. Hepatology. 1994;19:1513–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wachter H, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Reibnegger G, Werner ER. Neopterin as marker for activation of cellular immunity: immunologic basis and clinical application. Adv Clin Chem. 1989;27:81–141. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2423(08)60182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reibnegger G, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Werner ER, Werner-Felmayer G, Wachter H. Neopterin and viral infections: diagnostic potential in virally induced liver disease. Biomed Pharmacother. 1989;43:287–293. doi: 10.1016/0753-3322(89)90010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prior C, Fuchs D, Hausen A, Judmaier G, Reibnegger G, Werner ER, Vogel W, Wachter H. Potential of urinary neopterin excretion in differentiating chronic non-A, non-B hepatitis from fatty liver. Lancet. 1987;2:1235–1237. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91852-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samsonov MIu, Golban TD, Nasonov EL, Masenko VP. [Serum neopterin in hepatitis B] Klin Med (Mosk) 1992;70:40–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daito K, Suou T, Kawasaki H. Clinical significance of serum and urinary neopterin levels in patients with various liver diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:471–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez E, Rodrigo L, Riestra S, Carcia S, Gutierrez F, Ocio G. Adenosine deaminase isoenzymes and neopterin in liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:181–186. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200003000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonio DR, Gernot PT, Francısco G. Neopterin and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor type1 in alcohol-induced cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1995;21:976–978. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840210414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daito K, Suou T, Kawasaki H. Serum and urinary neopterin levels in patients with chronic active hepatitis B treated with interferon. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1994;83:303–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovacs EJ. Fibrogenic cytokines: the role of immune mediators in the development of scar tissue. Immunol Today. 1991;12:17–23. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zwirska-Korczala K, Dziambor AP, Wiczkowski A, Berdowska A, Gajewska K, Stolarz W. [Hepatocytes growth factor (HGF), leptin, neopterin serum concentrations in patients with chronic hepatitis C] Przegl Epidemiol. 2001;55 Suppl 3:164–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]