Abstract

The major papilla of Vater is usually located in the second portion of the duodenum, to the posterior medial wall. Sometimes the mouth of the biliary duct is located in other areas. Drainage of the common bile duct into the pylorus is extremely rare. A 73-year old man, with a history of duodenal ulcer, was admitted to hospital with the diagnosis of cholangitis. Dilatation of the extrahepatic biliary duct was observed by abdominal ultrasonography, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed. No area suggesting the presence of the papilla of Vater was found within the second duodenal portion. Finally the major papilla was located in the theoretical pyloric duct. Cholangiography was performed and choledocholithiasis was found in the biliary tree. The patient underwent dilatation of the papilla with a balloon tyre and removal of a 7 mm stone using a Dormia basket, which solved the problem without further complications. This anomaly increased the difficulty of performing therapeutic interventions during ERCP. This alteration in anatomy may increase the risk of complications during papillotomy, with a theoretically higher risk of perforation. Dilatation using a balloon was the chosen therapeutic technique both in our case and in the literature, due to its low rate of complications.

Keywords: Ectopic common bile duct, Endoscopic dilatation, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Papilla of Vater, Papillotomy, Pyloric drainage

INTRODUCTION

The major papilla of Vater is usually located in the second portion of the duodenum, to the posterior medial wall. Both the common bile duct and the main pancreatic duct empty into it. Sometimes the mouth of the biliary duct is located in other areas along the duodenum, mainly within the third or the fourth portion[1-3], although it has also been found with a much lower frequency in the duodenal bulb[4-6]. In such cases it is common to find a previous duodenal ulcerous pathology[7]. Very rarely has the papilla been found in the stomach[8-10], although the frequent use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has increased its recognition. In the literature we found a case in the 1930’s describing common bile duct drainage into the pylorus[2], and another more recent case of drainage into the duodenal wall adjacent to the pylorus[11], however, no more cases have been published. We describe a case in which the mouth of the biliary duct was found in the pyloric channel.

CASE REPORT

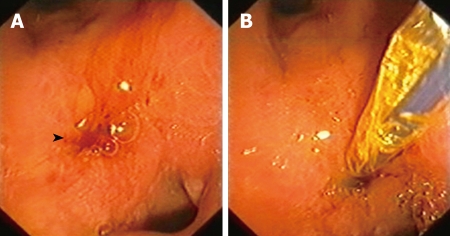

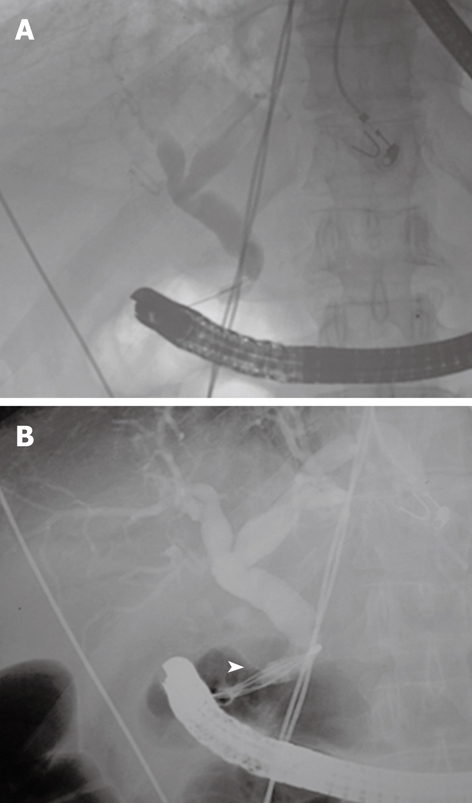

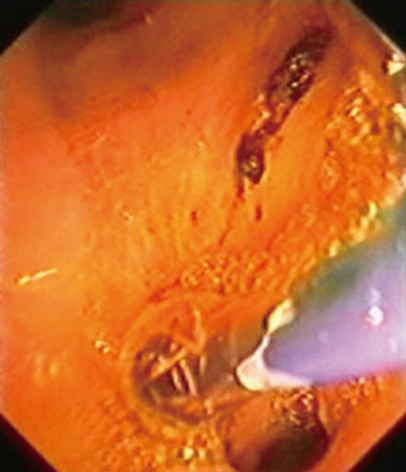

A 73-year-old patient, with a history of digestive bleeding secondary to duodenal ulcer 10 years previously, presented to hospital due to high temperature and pain in the right hypochondrium. His C-reactive protein level was 190 mg/dL, alanine-aminotransferase 40 IU/L, leucocytes 15 500/mm3 and total bilirubin 2.62 mg/dL. Abdominal ultrasonography showed dilatation of the extrahepatic biliary duct, with no lithiasis. After the diagnosis of cholangitis with increased bilirubin and dilatation of the biliary duct was made, ERCP was performed. No area suggesting the presence of the papilla of Vater was found within the second duodenal portion. Finally the major papilla was located in the theoretical pyloric duct (Figure 1), since the patient showed a duodenal bulb which was deformed and post-ulcerous, having disappeared almost completely. The papilla did not show clear anatomical signs which made it inadvisable to perform a papillotomy. Cholangiography was carried out and choledocholithiasis was found in the biliary tree (Figure 2A). The patient underwent dilatation of the papilla with a balloon tyre and removal of a 7 mm stone using a Dormia basket, which solved the problem without further complications (Figures 2B and 3).

Figure 1.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. A: View of the papilla located in the pylorus (arrow head); B: Piping of the papilla.

Figure 2.

Cholangiography. A: Common bile duct ending in a hook shape, common in proximal drainage of the papilla; B: Removal of choledocholithiasis with Dormia basket (arrow head).

Figure 3.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Balloon dilatation of the ectopic papilla.

DISCUSSION

The papilla of Vater is a bulge in the duodenal mucosa into which both the common bile duct and the Wirsung empty, sometimes shaping into a Y, or they can be separated by a mucosa layer making them independent. The most common location of the papilla of Vater is within the posterior medial wall of the second portion of the duodenum. The frequent use of ERCP has allowed better observation of papillae in an ectopic location. Although the diagnosis of ectopic papillae have been described by other types of radiological studies such as computed tomography[4], X-ray of the esophagusgastroduodenal tract[12], intraoperative cholangiography[1] and echoendoscopy[5], most ectopic papillae are identified by ERCP. An ectopic location distal to the second duodenal portion, within the third and fourth duodenal portions, has been described frequently, and has a frequency rate of 5.6% to 23%[13]. Ectopic papillae are much less frequent in a proximal location, and a few cases have been located in the gastric, pylorus and duodenal bulb areas[14]. Filippini in 1931 described the first case of papilla located in the pylorus[2], although Quintana and Labat[2] mentioned 3 cases of dual drainage in the duodenum and pylorus. Another recent case has been described where the papilla was located in the posterior duodenal wall below the pylorus[11]. In our subject the papilla was located in the pylorus, with a duodenal bulb which was deformed due to previous ulcerous pathology.

A theory on the origin of ectopic papillae has been suggested which describes their occurrence during embryonic formation. The liver originates in the hepatic diverticulum, which is divided into the hepatic pars and the cystic pars during embryogenesis. The hepatic pars then develops into both the liver and the hepatic ducts, while the cystic pars develops into the gall-bladder and the cystic duct. The common bile duct originates in the hepatic antrum, which is the common area of the hepatic diverticulum. Boyden[15] claimed that an earlier subdivision of the hepatic diverticulum could cause the common bile duct to empty into different locations other than the usual location.

Ectopic papillae located in the bulb may be secondary to an ulcerous duodenal pathology, which could cause, due to contiguity, anomalous drainage in the duodenum[11]. In our patient the location of the papilla in the pyloric channel might be related to the patient’s previous ulcerous duodenal pathology. Nevertheless, since we did not find signs of the papilla in the second duodenal portion, his condition was probably due to a congenital malformation with biliary and pancreatic drainage in the posterior pyloric area, which could have caused the later development of a duodenal ulcer. In our subject we observed the diagnosis requirements for an ectopic papilla as described by Lee et al[14], for a location in the bulb which were: (1) an orifice was observed in the bulb by duodenoscopy or upper endoscopy, and the bile duct and/or the pancreatic duct were directly visualized radiographically, when contrast was injected via this opening; (2) there was direct drainage of the common bile duct into the duodenal bulb without evidence of any other drainage into the duodenum on cholangiography; and (3) there was no evidence of a papilla-like structure in the second or third duodenal portion on duodenoscopic examination. Fistula secondary to ulcer disease or choledocholithiasis, spontaneous or iatrogenic surgical fistula, and surgical choledochoenteric diversion should be included in the differential diagnosis[8].

The clinical importance of the ectopic location of the papilla means that there is a tendency for the development of choledocholithiasis through anomalous bile drainage, due to the lack of a sphincter mechanism. Likewise, it can also lead to mucosal damage in the area, with swelling and ulcer formation, due to the action of biliary pancreatic secretion[14]. The clinical symptoms may include recurrent abdominal pain, which could explain the high percentage of patients undergoing cholecystectomy described in some series[13]. The absence of a sphincter would allow passage of the gastroduodenal contents into the main bile duct, possibly causing cholangitis in association with biliary obstruction[7,13,14]. In a recent study by Disibeyaz et al[13] on 39 patients where the papilla was located in the bulb, they detected episodic abdominal pain in 95% of patients and cholangitis in 59% of patients. The predominance of male sex and an association with ulcerous duodenal pathology in 61.5% of the patients should be emphasized. In our case, the patient had a history of duodenal ulcer and was admitted to hospital suffering from cholangitis, which led us to think that this patient had a papilla in an ectopic location when we failed to find it in its usual location, making it necessary to check both the duodenal bulb and the stomach.

This anomaly increased the difficulty of performing therapeutic interventions during ERCP. This alteration in anatomy, when there are no clear anatomic signs, may increase the risk of complications during papillotomy, with a theoretically higher risk of perforation, as has been described in the literature[13]. Balloon dilatation may be the chosen technique for these patients when there is a biliary obstruction. Its effectiveness has recently been suggested, especially when gallstones need to be removed, without relevant complications[13]. Stent installation may be necessary when balloon dilatation is unsuccessful and the patient has comorbidities which make surgery inadvisable. The surgical option should only be taken in these cases when endoscopic treatment is not effective.

In conclusion, ectopic location of the papilla is a rare finding, however, the frequent use of ERCP may increase the number of cases diagnosed. Although a distal location is found most frequently, a proximal location must be taken into account, especially in patients with a history of recurrent abdominal pain, cholangitis, ulcerous duodenal pathology and biliary obstruction in whom the papilla cannot be found in its usual location during ERCP. Although further studies are necessary, balloon dilatation was the chosen therapeutic technique both in our case and in the literature, due to its low rate of complications. Technical difficulty and a higher probability of perforation when performing a papillotomy, due to the lack of anatomic reference, make its use inadvisable.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Dr. Aydin Karabacakoglu, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology, Meram Medical Faculty, Selcuk University, Konya 42080, Turkey

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Lindner HH, Peña VA, Ruggeri RA. A clinical and anatomical study of anomalous terminations of the common bile duct into the duodenum. Ann Surg. 1976;184:626–632. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197611000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quintana EV, Labat R. Ectopic drainage of the common bile duct. Ann Surg. 1974;180:119–123. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197407000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doty J, Hassall E, Fonkalsrud EW. Anomalous drainage of the common bile duct into the fourth portion of the duodenum. Clinical sequelae. Arch Surg. 1985;120:1077–1079. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390330083018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee HJ, Ha HK, Kim MH, Jeong YK, Kim PN, Lee MG, Kim JS, Suh DJ, Lee SG, Min YI, et al. ERCP and CT findings of ectopic drainage of the common bile duct into the duodenal bulb. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:517–520. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.2.9242767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krstic M, Stimec B, Krstic R, Ugljesic M, Knezevic S, Jovanovic I. EUS diagnosis of ectopic opening of the common bile duct in the duodenal bulb: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5068–5071. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i32.5068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozaslan E, Saritaş U, Tatar G, Simşek H. Ectopic drainage of the common bile duct into the duodenal bulb: report of two cases. Endoscopy. 2003;35:545. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song MH, Jun DW, Kim SH, Lee HH, Jo YJ, Park YS. Recurrent duodenal ulcer and cholangitis associated with ectopic opening of bile duct in the duodenal bulb. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:324–325; discussion 325. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira-Lima J, Pereira-Lima LM, Nestrowski M, Cuervo C. Anomalaous location of the papilla of vater. Am J Surg. 1974;128:71–74. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(74)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanematsu M, Imaeda T, Seki M, Goto H, Doi H, Shimokawa K. Accessory bile duct draining into the stomach: case report and review. Gastrointest Radiol. 1992;17:27–30. doi: 10.1007/BF01888503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katsinelos P, Papaziogas B, Paraskevas G, Chatzimavroudis G, Koutelidakis J, Katsinelos T, Paroutoglou G. Ectopic papilla of vater in the stomach, blind antrum with aberrant pyloric opening, and congenital gastric diverticula: an unreported association. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:434–437. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181257256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung HY, Kim JI, Park YB, Cheung DY, Cho SH, Park SH, Han JY, Kim JK. The papilla of Vater just below the pylorus presenting as recurrent duodenal ulcer bleeding. Intern Med. 2007;46:1853–1856. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holz K. [Atypical orifice of the common bile duct during localization of the Vater papilla on the rear wall of the duodenal bulb] Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Nuklearmed. 1970;112:409–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Disibeyaz S, Parlak E, Cicek B, Cengiz C, Kuran SO, Oguz D, Güzel H, Sahin B. Anomalous opening of the common bile duct into the duodenal bulb: endoscopic treatment. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Kim KP, Kim HJ, Bae JS, Kim HJ, Seo DW, Ha HK, Kim JS, et al. Ectopic opening of the common bile duct in the duodenal bulb: clinical implications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:679–682. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyden EA. The problem of the double ductus choledochus (an interpretation of an accessory bile duct found attached to the pars superior of the duodenum) Anat Rec. 1932;55:71–94. [Google Scholar]