SYNOPSIS

Objectives

We sought to determine whether low acculturation, based on language measures, leads to disparities in cardiovascular risk factor control in U.S. Hispanic adults.

Methods

We studied 4,729 Hispanic adults aged 18 to 85 years from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2004. We examined the association between acculturation and control of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, blood pressure, and hemoglobin A1c based on national guidelines among participants with hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and diabetes, respectively. We used weighted logistic regression adjusting for age, gender, and education. We then examined health insurance, having a usual source of care, body mass index, fat intake, and leisure-time physical activity as potential mediators.

Results

Among participants with hypercholesterolemia, Hispanic adults with low acculturation were significantly more likely to have poorly controlled LDL cholesterol than Hispanic adults with high acculturation after multivariable adjustment (odds ratio [OR] = 3.4, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2, 9.5). Insurance status mildly attenuated the difference in LDL cholesterol control. After adjusting for diet and physical activity, the magnitude of the association increased. Other covariates had little influence on the observed relationship. Among those with diabetes and hypertension, we did not observe statistically significant associations between low acculturation and control of hemoglobin A1c (OR=0.5, 95% CI 0.2, 1.2), and blood pressure (OR=1.1, 95% CI 0.6, 1.7), respectively.

Conclusions

Low levels of acculturation may be associated with increased risk of inadequate LDL cholesterol control among Hispanic adults with hypercholesterolemia. Further studies should examine the mechanisms by which low acculturation might adversely impact lipid control among Hispanic adults in the U.S.

The Hispanic population comprised 44.3 million (14.8%) of the U.S. population in 20061 and is projected to rise to 102.6 million (24.4%) by 2050.2 Despite recent federal initiatives to eliminate health disparities among racial/ethnic groups, leading indicators of health continue to demonstrate disparities for the Hispanic population.3

The role of acculturation in explaining variation in health within racial/ethnic groups has received increasing attention in recent years. Acculturation has been previously defined as the process of adapting to a new culture, measured by the degree to which immigrants have integrated the values, beliefs, and attitudes of a new country into their daily lives.4 Language comprises an important part of acculturation, particularly for the Hispanic population, as more than three-quarters of the U.S. Hispanic population speak a language other than English at home. Language barriers negatively affect the health-care experiences of Spanish-speaking patients.5 More specifically, patients with limited English proficiency are more likely to have problems understanding a medical situation and more trouble understanding drug labels.6

The “Hispanic paradox”—the finding that people of Hispanic origin have better health and mortality profiles than non-Hispanic white people—may distract efforts to improve the health of Latino populations, despite more recent evidence indicating that this health advantage is limited.7 In fact, studies have shown that the Hispanic population has worse control of cardiovascular risk factors compared with the non-Hispanic white and black populations.8,9 However, the mediators underlying this disparity are not known. Mexican Americans with a low level of acculturation are less likely to be screened and diagnosed for cardiovascular disease than Mexican Americans with a high level of acculturation.10,11 Furthermore, Hispanic people may be more likely to have inadequate intensification of their medications than their non-Hispanic white and black counterparts.12 However, it is unknown whether acculturation is a contributing factor to disparities in cardiovascular risk factor control.

We hypothesized that Hispanic adults with a low level of acculturation have greater risk for poorly controlled cardiovascular risk factors than Hispanic adults with a high level of acculturation. We investigated the relationship of acculturation and the control of hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and diabetes among a national sample of U.S. Hispanic adults.

METHODS

Participants

We analyzed cross-sectional data from Hispanic participants aged 18 to 85 years in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1999–2004. After excluding 47 participants who were missing information on acculturation variables, 4,729 Hispanic participants comprised our study sample.

Data collection

NHANES is a cross-sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the civilian, noninstitutionalized U.S. population. Detailed in-home interviews are conducted in Spanish and English. Physical examinations include measurement of height, weight, blood pressure, and collection of blood samples by trained personnel. Participants had their blood pressure measured at least three times using a mercury sphygmomanometer according to the standards of the American Heart Association Human Blood Pressure Determination.13

The NHANES design includes an oversampling of Mexican Americans and African Americans. NHANES uses a complex, multistage probability sampling design to select participants representative of the U.S. population. Although we recognize that “Latino” may be more appropriate for describing this study population, we have used “Hispanic” throughout this article, as this was the term used by NCHS to describe its study participants.

Measures

We assessed the degree of acculturation using the Short Acculturation Scale, a five-item scale measuring use of the Spanish language that has good internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha ≥0.90) and has been shown to be comparable to longer published acculturation scales. This scale has been validated in several Hispanic populations and correlates with other measures of acculturation, including number of generations living in the U.S., length of time lived in the U.S., age at the time of arrival in the U.S., and self-reported acculturation.14 The scale consists of the following five questions: (1) In general, what language do you read and speak? (2) What was the language(s) you used as a child? (3) What language(s) do you usually speak at home? (4) In which language(s) do you usually think? and (5) What language(s) do you usually speak with your friends? The options for answering each question are “only English,” “more English than Spanish,” “both equally,” “more Spanish than English,” and “only -Spanish.” These responses were each scored on a scale from 1 to 5, yielding a total score ranging from 5 to 25, with lower scores signifying greater acculturation.

We based our classification of acculturation status on approximate tertiles of the scale distribution as follows: Short Acculturation Scores of 5 (most acculturated), 6–15 (less acculturated), and 16–25 (least acculturated). For ease of reporting, we will refer to participants in the least acculturated group as participants with low acculturation and compare them with the most acculturated group, which we will refer to as participants with high acculturation. We also examined control of cardiovascular risk factors using acculturation as a continuous variable. We observed similar trends. As categories of acculturation are more interpretable than point differences in a continuous acculturation measure, tertiles of acculturation are presented in the results section.

Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors was defined by self-reported diagnosis, current use of disease-specific medication from the medication list given by the patient during the NHANES interview, and/or laboratory/physical examination diagnosis. Hypercholesterolemia was prevalent if any of the following was true: (1) a “yes” response to the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that your blood choleseterol level was high?”, (2) being on a cholesterol-lowering drug, and/or (3) having elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol on the NHANES laboratory exam, as defined later in this article.

Hypertension was prevalent if any of the following was true: (1) a “yes” response to the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had hypertension, also called high blood pressure?”, (2) being on a high blood pressure medication, and/or (3) having systolic blood pressure ≥140 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg on the NHANES physical exam.

Diabetes was present if any of the following was true: (1) a “yes” response to the question, “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?”, (2) being on a blood glucose regulator, (3) having a fasting glucose ≥126 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL), and/or (4) having a random glucose ≥200 mg/dL on the NHANES laboratory exam.

We categorized participants according to control of cardiovascular risk factors. Poor hypercholesterolemia control was defined by Adult Treatment Panel II guidelines,15 as these were in use during the majority of the study period 1999–2004 and would also reduce probability of false positives. The guidelines were LDL cholesterol ≥190 mg/dL for 0–1 risk factors, ≥160 mg/-dL for ≥2 risk factors, and ≥130 mg/dL for a history of coronary heart disease. Inadequate hypertension control was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg. Inadequate diabetes control was defined as a hemoglobin A1c ≥7.0 mg/dL.

Analysis

We assessed statistical comparisons for categorical variables using Chi-square tests and for continuous variables using t-tests (p<0.05). All analyses were appropriately weighted and adjusted for the complex sampling design effects in NHANES using SUDAAN® software.16 We used weighted logistic regression to examine the relationship between acculturation and control of LDL cholesterol, hemoglobin A1c, and blood pressure among those subjects with hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and hypertension, respectively, while adjusting for age and gender. We included education (<high school or ≥high school) in our models as a potential confounder given its possible influence on acculturation status. Initially, we used a three-level education variable (<12 years, 12 years, and >12 years) but later combined the 12 years and >12 years categories because they were similar in their association to cardiovascular risk factor control among our acculturation groups.

In our modeling approach, we assessed potential mediation by adding each covariate separately into our models. Potential mediators were factors that may have been influenced by acculturation level and thereby contributed to our outcomes. In our second model, we assessed for health insurance (none, Medicare/Medicaid/other government insurance, or other—comprised mostly of private insurance) and having a usual source of care in the event of sickness or requiring health advice. In our third model, we assessed for body mass index (BMI) (<25 kilograms per meter squared [kg/m2], 25–29 kg/m2, and ≥30 kg/m2), percent of calories from total fat (<3%, 3%–39%, and ≥40% to assess national guidelines17), and physical activity (engaged in leisure-time physical activity in the past month, including exercise, sports, and physically active hobbies, as previously described18). We did assess smoking status, but did not include smoking in our model given the large number of other covariates and because it had little effect on the observed relationships. We also attempted to assess income, but because more than 10% of this population did not report income, we excluded this measure from the model.

We tested correlation coefficients for all covariates; none was significantly different from zero and no observed correlation was higher than 0.4. In a post-hoc analysis to better understand the observed associations between acculturation status and LDL control, we explored subgroups of people with hyperlipidemia according to whether or not they self-reported hyperlipidemia/high cholesterol.

RESULTS

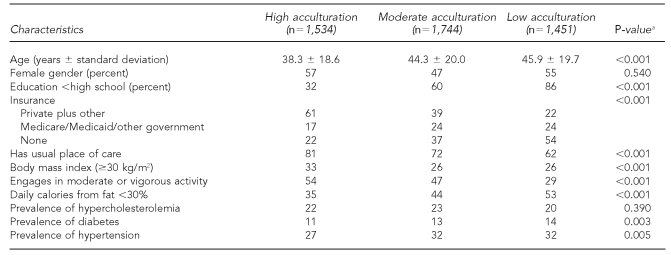

Hispanic participants with low acculturation were older, less educated, and more likely to be uninsured compared with Hispanic participants with high acculturation (Table 1). We found the prevalence of risk factors among Hispanic participants was 22% for hypercholesterolemia, 13% for diabetes, and 31% for hypertension. Prevalence of diabetes and hypertension was higher among Hispanic participants with low acculturation compared with Hispanic participants with high acculturation. Of participants classified as having risk factors, some participants met diagnostic criteria using only self-report: 59% for hypercholesterolemia, 22% for diabetes, and 26% for hypertension. Some participants met diagnostic criteria at the NHANES exam using only laboratory or physical findings: 15% for hypercholesterolemia, 12% for diabetes, and 27% for hypertension.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for Hispanic participants by acculturation status in NHANES, 1999–2004

aMantel-Haenzel Chi-square test for trend (1 degree of freedom) for all analyses except t-test for age

NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

kg/m2 = kilograms per meter squared

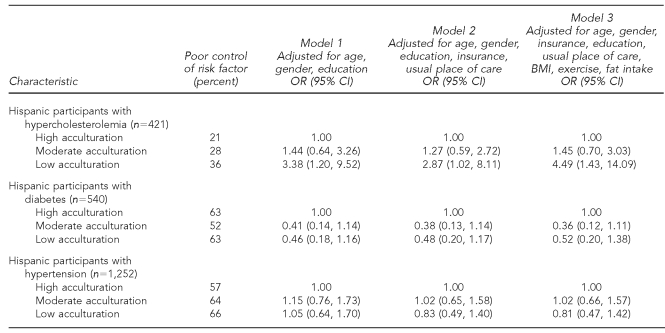

After adjusting for age, gender, and education, Hispanic participants with low acculturation were more than three times as likely to have poorly controlled LDL cholesterol compared with Hispanic participants with high acculturation (Table 2). Among those with diabetes, Hispanic participants with low acculturation appeared to have slightly better hemoglobin A1c control, but this did not reach statistical significance. Among those with hypertension, Hispanic participants with low acculturation had similar control of blood pressure compared with Hispanic participants with high acculturation.

Table 2.

Odds ratios for poor risk factor control by acculturation status among Hispanic participants with hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and hypertension in NHANES, 1999–2004

NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

BMI = body mass index

The observed difference in LDL control among Hispanic participants with hypercholesterolemia was mildly attenuated by health insurance (odds ratio [OR] = 2.70, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.20, 6.10). There did not appear to be a substantial influence by having a usual place of care after adjustment (OR=2.87, 95% CI 1.02, 8.11). Additional adjustment for BMI had little influence on the observed effect (OR=2.90, 95% CI 1.10, 8.30). However, adjusting for physical activity strengthened the association (OR=3.50, 95% CI 1.30, 9.70). Similarly, subsequent adjustment for diet by fat intake further strengthened the assocation (OR=4.49, 95% 1.43, 14.09).

In our final model, we also adjusted for anti-lipid medication use, which did not materially affect the association between acculturation and LDL cholesterol control. As a subgroup analysis, we investigated whether awareness of hyperlipidemia was associated with improved lipid control. Among those who were aware of their hypercholesterolemia, participants with low acculturation were more likely to have poor LDL control (OR=1.70, 95% CI 0.30, 10.60). Among those without known hypercholesterolemia, those with low acculturation had even worse control of LDL (OR=1.96, 95% CI 0.89, 4.30); however, these differences were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that, in comparison with Hispanic adults with high acculturation, Hispanic adults with low acculturation have a significantly greater risk of poor hypercholesterolemia control, but not hypertension or diabetes control. This relationship was only partially accounted for by the socioeconomic factors that we assessed. As might be expected, those with low acculturation had less access to health care measured by health insurance status. After adjusting for differential access to care, the difference in LDL cholesterol control was modestly attenuated. Conversely, additional adjustment for fat intake and physical activity strengthened the association between acculturation and inadequate LDL control.

Similar to previous studies,19,20 our data show that Hispanic adults with high acculturation tend to participate more in physical activity and have worse diets. In our study, fat intake appeared to have a stronger influence than leisure-time physical activity on the OR. This may be related to evidence showing that Hispanic adults with low acculturation actually have better diets than Hispanic adults with high acculturation.21

Reasons are unclear for the differential influence of acculturation on the control of the three cardiovascular risk factors we studied. One possibility may be the public's greater awareness of hypertension and diabetes and their sequelae, including tangible complications such as visual impairment, renal impairment, and stroke. That is, those who are more acculturated may have better controlled hypertension and diabetes over hypercholesterolemia, perhaps due to less awareness of the importance of cholesterol control on their cardiovascular health.

Our results also demonstrated a higher prevalence of diabetes and hypertension among Hispanic participants with low acculturation compared with those with high acculturation. These differences could not be attributed to a particular mode of diagnosis (e.g., self-report, being on risk factor-specific medication, or by physical/laboratory NHANES exam). It is unclear why these participants with low acculturation had a higher prevalence of diabetes and hypertension given that it has been well documented that newly arrived immigrants tend to be healthier. However, we could not assess the influence of duration of U.S. residence, which was unavailable for most study participants.

For this study, acculturation status was largely composed of language variables. It is possible that participants who did not speak English were not being told by doctors that they were at risk for diabetes or hypertension, not getting appropriate medication, or not having the appropriate testing. Furthermore, our own previous work has shown that using mass media in Spanish rather than English is associated with underdiagnosis of hypertension.10 That is, those who watch television, listen to the radio, or read newspapers and magazines in Spanish rather than English are more likely to have undiagnosed hypertension. There may also be differences in health education content in Spanish- vs. English-language media sources with regard to cardiovascular risk factors.

The findings from this study may identify one potential area for improvement that could be addressed through culturally competent initiatives. For example, educational programs that focus on Hispanic patients with limited English proficiency, particularly providing information and medical care in Spanish, may improve lipid control among Hispanic patients with hypercholesterolemia. Low acculturation may affect lipid control at different points, including a patient's decision to seek care, access to a primary care physician, diagnosis of disease, the patient-physician relationship, and adherence to treatment regimens. This study was not designed to differentiate among these etiologies.

Limitations

One limitation of this study was the small sample size of the participants with cardiovascular risk factors, which diminished the ability to detect differences between some groups, particularly those with diabetes. We were also unable to assess for other possible mediators and confounders, including patient-physician language concordance and medication adherence. As this was an observational cross-sectional study, the results only point to associations and not causal relationships.

Another limitation was our use of an abbreviated acculturation scale based largely on language. This scale did not capture the true breadth of one's acculturation. However, there is currently no gold standard scale to measure acculturation.22 Our acculturation scale did capture various aspects of language and has been validated. NHANES oversamples for Mexican Americans and, although they do comprise the largest immigrant group from Latin America, data gathered from NHANES cannot be generalized to the entire Latino population or to any non-Mexican American subgroup.23 There is ample evidence to indicate that health outcomes for the Latino population vary by subgroup.7 One strength of our study was the use of national guidelines to determine control of cardiovascular risk factors rather than simply differences in cardiovascular risk factor levels, as control is clinically relevant.

CONCLUSIONS

Compared with Hispanic adults with high acculturation, Hispanic adults with low acculturation are less likely to achieve control of hypercholesterolemia. Further studies should be performed to confirm this finding and examine the mechanisms by which limited English proficiency has an adverse impact on lipid control among the U.S. Hispanic population. Programs that bridge the language gap may improve lipid control among the Hispanic population with low acculturation and reduce its risk for cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Russell Phillips for his review of this article. This research was supported by an Institutional National Research Service Award #T32 HP11001-18.

References

- 1.Census Bureau (US) Annual estimates of the resident population by sex, race, and Hispanic origin for the United States. [cited 2009 Jun 9]. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov?jpc/www/usinterimproj.

- 2.Census Bureau (US) 2006 American Community Survey. [cited 2009 Jun 9]. Available from: URL: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DatasetMainPageServlet?_program=ACS&_submenuId=&_lang=en&_ts=

- 3.Department of Health and Human Services (US) Data 2010: the Healthy People 2010 database. Hyattsville (MD): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (US); 2004. [cited 2009 Jun 9]. Also available from: URL: http://wonder.cdc.gov/data2010/focus.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peragallo NP, Fox PG, Alba ML. Acculturation and breast self-examination among immigrant Latina women in the USA. Int Nurs Rev. 2000;47:38–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2000.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez-Stable EJ, Napoles-Springer A, Miramontes JM. The effects of ethnicity and language on medical outcomes of patients with hypertension or diabetes. Med Care. 1997;35:1212–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199712000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson E, Chen AH, Grumbach K, Wang F, Fernandez A. Effects of limited English proficiency and physician language on health care comprehension. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:800–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajat A, Lucas JB, Kington R. Health outcomes among Hispanic subgroups: data from the National Health Interview Survey, 1992–95. Adv Data. 2000:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He J, Muntner P, Chen J, Roccella EJ, Streiffer RH, Whelton PK. Factors associated with hypertension control in the general population of the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1051–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.9.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McBean AM, Huang Z, Virnig BA, Lurie N, Musgrave D. Racial variation in the control of diabetes among elderly Medicare managed care beneficiaries. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3250–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eamranond PP, Patel KV, Legedza AT, Marcantonio ER, Leveille SG. The association of language with prevalence of undiagnosed hypertension among older Mexican Americans. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:699–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jurkowski JM, Johnson TP. Acculturation and cardiovascular disease screening practices among Mexican Americans living in Chicago. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:411–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hicks LS, Shaykevich S, Bates DW, Ayanian JZ. Determinants of racial/ethnic differences in blood pressure management among hypertensive patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perloff D, Grim C, Flack J, Frohlich ED, Hill M, McDonald M, et al. Human blood pressure determination by sphygmomanometry. Circulation. 1993;88(5 Pt 1):2460–70. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marin G, Sabogal RF, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic J Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Summary of the second report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel II) JAMA. 1993;269:3015–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Research Triangle Institute. Research Triangle Park (NC): Research Triangle Institute; 1995. SUDAAN®. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Diabetes Association Task Force for Writing Nutrition Principles and Recommendations for the Management of Diabetes and Related Complications. American Diabetes Association position statement: evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:109–18. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sundquist J, Winkleby M. Country of birth, acculturation status and abdominal obesity in a national sample of Mexican-American women and men. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:470–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ham SA, Yore MM, Kruger J, Moeti R, Heath GW. Physical activity patterns among Latinos in the United States: putting the pieces together. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4:A92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abraido-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Florez KR. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1243–55. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:367–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter-Pokras O, Zambrana RE, Yankelvich G, Estrada M, Castillo-Salgado C, Ortega AN. Health status of Mexican-origin persons: do proxy measures of acculturation advance our understanding of health disparities? J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10:475–88. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Center for Health Statistics (US) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2000: addendum to the NHANES III analytic guidelines. [cited 2009 Jun 9]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/nhanes2003-2004/analytical_guidelines.htm.