Abstract

Viral RNA can trigger interferon signaling in dendritic cells via the innate recognition receptors melanoma-differentiation-associated gene (MDA)-5 and retinod-inducible gene (RIG)-I in the cytosol or via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in intracellular endosomes. We hypothesized that viral RNA would also activate glomerular mesangial cells to produce type I interferon (IFN) via TLR-dependent and TLR-independent pathways. To test this hypothesis, we examined Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-β (TRIF)-deficient mice, which lack a key adaptor for TLR3 signaling. In primary mesangial cells, poly I:C RNA-mediated IFN-β induction was partially TRIF dependent; however, when poly I:C RNA was complexed with cationic lipids to enhance cytosolic uptake, mesangial cells produced large amounts of IFN-α and IFN-β independent of TRIF. Mesangial cells expressed RIG-I and MDA-5 and their mitochondrial adaptor IFN-β promoter stimulator-1 as well, and small interfering RNA studies revealed that MDA5 but not RIG-I was required for cytosolic poly I:C RNA signaling. In addition, mesangial cells produced Il-6 on stimulation with IFN-α and IFN-β, suggesting an autocrine proinflammatory effect. Indeed, blockade of IFN-αβ or lack of the IFNA receptor reduced viral RNA-induced Il-6 production and apoptotic cell death in mesangial cells. Furthermore, viral RNA/cationic lipid complexes increased focal necrosis in murine nephrotoxic serum nephritis in association with increased renal mRNA expression of IFN-related genes. Thus, TLR-independent recognition of viral RNA is a potent inducer of type I interferon in mesangial cells, which can be an important mediator of virally induced glomerulonephritis.

Chronic viral infections can trigger de novo immune complex glomerulonephritis, eg, hepatitis C virus-associated glomerulonephritis, but more frequently, acute viral infections trigger disease activity of pre-existing glomerulonephritis, like in IgA nephropathy, lupus nephritis, or renal vasculitis.1 Viral infections activate systemic antiviral immunity, which may contribute to disease flares of glomerulonephritis by enhancing autoantibody production, immune complex formation, or by systemic interferon (IFN) release.2 In fact, rapid production of type I IFN is a central element of antiviral immunity because type I IFNs inhibit viral replication in the infected cells and have pleiotrophic immunomodulatory effects on macrophages, T cells, and natural killer cells.2,3

The main source of type I IFNs is plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) in the intravascular compartment.4 Several viral components can induce type I IFNs in pDCs. For example, viral proteins activate Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and 4 signaling at the cell surface.5 By contrast, different shapes of viral nucleic acids can activate TLRs in intracellular endosomes, ie, TLR3 (double-stranded (dsRNA)), TLR7/8 (single-stranded (ssRNA)), and TLR9 (CpG-DNA).5 Furthermore, viral RNA can also be detected in the intracellular cytosol, eg, via melanoma-differentiation-associated gene (MDA)-5 (dsRNA) and retinoic-acid-inducible protein (RIG) (dsRNA and 5′-triphosphate RNA).5,6,7,8 Ligation of any of these innate RNA recognition receptors rapidly triggers the production of type I IFN in pDCs.

It is thought that most cells can produce type I IFNs when they are infected with a DNA or RNA virus. For example, TLR3-mediated recognition of viral dsRNA in pancreatic islet cells can trigger autoimmune pancreatic islet destruction via local production of IFN-α.9 But whether locally produced type I IFNs contribute to viral infection-induced glomerulonephritis is not known.10 In fact, to our best knowledge, IFN release by glomerular cells, including mesangial cells, has not been reported. The only nucleic acid-specific TLR expressed by mesangial cells is TLR3, and mesangial cells produce Il-6 and CCL2 on exposure to viral dsRNA.11 However, whether this effect is mediated via endosomal TLR3 or by cytosolic dsRNA receptors is not known. We hypothesized that viral RNA will trigger an innate antiviral response program in glomerular mesangial cells, including the release of type I IFN, and that this effect is mediated by TLR-dependent as well as TLR-independent RNA recognition.

Materials and Methods

Studies with Primary Mesangial Cells

Six-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany). Trif-mutant mice in the C57BL/6 background were generated as described previously.12 IFN-αβ-R-deficient 129Sv/Ev control mice were obtained from B&K Universal Group (North Humberside, UK). For the preparation of primary mesangial cells, capsule and medulla of the kidney were removed, and the renal cortices were diced in cold PBS and subsequently passed through a series of stainless steel sieves (150, 103, 63, 50, and 45 μm) and treated with a 1 mg/ml solution of type IV collagenase (Worthington, Lakewood, NY) for 15 minutes at 37°C. After five passages, the glomerular cell isolates were >99% positive for smooth muscle actin and >99% negative for cytokeratin 18, ie, glomerular mesangial cells. Primary mesangial cells were stimulated with endotoxin-free poly I:C RNA (InvivoGen, Toulouse, France), poly I:C RNA transfected with the cationic lipid Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or ultrapure LPS (InvivoGen) for 24 hours in RPMI 1640 containing 5% FCS in the presence or absence of murine IFN-α (AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK), IFN-β (PBL, Piscataway, NJ), or IFN-γ (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ). Poly I:C RNA and Lipofectamine were preincubated with polymyxin B (Invivogen) before use to block any residual LPS contamination. Rat monoclonal antibodies against mouse IFN-α and IFN-β (PBL) were used to neutralize these IFNs in vitro. Cytokine levels were measured in cell supernatants using commercial ELISA kits for Il-6 (detection limit: 2 pg/ml, OptEiA; BD Pharmingen), IFN-α (detection limit: 15 pg/ml; PBL), IFN-β (detection limit 10 pg/ml; PBL), or IFN-γ (detection limit 10 pg/ml; BD Pharmingen). Proliferation of mesangial cells was assessed using CellTiter 96 Proliferation Assay (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) with and without inhibitors against caspase-2, -8, -9, and -10 (all from Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ).

Western Blot

Proteins from mesangial cells and unstimulated J774 macrophages were harvested using 120 μl of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mmol/L Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0,1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholat, and 1% Nonidet P-40) plus the protease inhibitor tablets Complete (Roche), incubated on ice for 10 minutes, and centrifuged for another 10 minutes at 15,000 × g. Extracted proteins were incubated in 2× loading buffer for 30 minutes at 65°C, resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Eschborn, Germany). After blocking with 3% skim milk, the filter was incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against TLR3 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), Rig-I (2 μg/ml; ProSci, Poway, CA), rabbit polyclonal antibody to Mda5 (AL 180) (1/1000; Alexis), or to β-actin (Abcam) overnight. Binding was visualized using a peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1/10,000; Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany) and processed for detection by enhanced chemiluminescence (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA).

RNA Silencing Studies

Rig-I (DDX58) small interfering RNA (siRNA) ON-TARGETplus SMART pool oligonucleotides (Dharmacon), Mda5 siRNA and negative control siRNA (Ambion/Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany) sequences were as follows: DDX58 (Rig-1), 5′-CAAGAAGAGUACCACUUAAUU-3′, 5′- GUUAGAGGAACACAGAUUAUU-3′, 5′-GUUCGAGAUUCCAGUCAUAUU-3′, 5′-GAAGAGCACGAGAUAGCAAUU-3′; and Mda5, 5′-GAACGUAGACGACAUAUUA-3′, 5′-CAACGAAGCCCUACAAAUC-3′, 5′-CUUGAUGCCUUUACCAUUA-3′, 5′-GGGAGAUUGUUAAUGAUUU-3′. Mesangial cells (1 × 105) were plated in 12-well plates in antibiotic free 2% fetal calf serum-Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium. siRNA (40 nmol/L) was transfected twice with cationic lipid as mentioned above. After 24 hours of second transfection, cells were stimulated with 3 μg of poly I:C RNA with and without cationic lipids for 6 hours. Knockdown efficacy of Rig-1, Mda5, and primary mesangial cell mRNA expression of Cxcl10 and Il-6 mRNA expression were determined by real-time RT-PCR after 6 hours.

Flow Cytometry

Primary mesangial cells were stimulated with poly I:C RNA as before in the presence or absence of the caspase-8 inhibitor Ac-IETD-CHO (5 μg/ml; Biomol, Hamburg, Germany). Propidium iodide staining (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) was used to identify death cells.

Autologous Nephrotoxic Serum Nephritis

Nephritis was induced in groups of C57BL/6 wild-type mice using a rabbit antiserum and protocol as previously described in detail.13 Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation 10 days after injection of the antiserum. Urinary albumin and creatinine concentrations were determined as described previously.13 Two-micrometer renal sections for periodic acid-Schiff stains were prepared following routine protocols. Glomerular focal necrosis score defined by desintegrated glomerular loops with glomerular cell necrosis was assessed on 15 cortical glomerular sections each graded as follows: 0 = intact glomerulus, 1 = necrotic lesion <25% of glomerular tuft, 2 = 25–50% of glomerular tuft, and 3 = >50% of glomerular tuft.

Real-Time PCR and Reverse Transcription

The mRNA expression in cultured cells or renal tissue real-time PCR was quantified using TaqMan as described previously.11 Controls consisting of double-distilled H2O were negative for target and housekeeper genes. Oligonucleotide primer (300 nmol/L) and probes (100 nmol/L) used were from PE Biosystems (Weiterstadt, Germany) and are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Murine Probes Used for Real-Time RT-PCR

| Gene | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Il-6 | FAM 5′-AAATGAGAAAAGAGTTGTGCAATGG-3′ |

| IFN-γ | FAM 5′-CTATTTTAACTCAAGTGGCATAGAT-3′ |

| Ifih/ Mda-5 | FAM 5′-GACACCAGAGAAAATCCATTTAAAG-3′ |

| Ips-1/Visa | FAM 5′-AGTGACCAGGATCGACTGCGGGCTT-3′ |

| Ddx58/Rig-I | FAM 5′-CCAAACCAGAGGCCGAGGAAGAGGCA-3′ |

| Tlr3 | FAM 5′-CACTTAAAGAGTTCTCCC-3′ |

| Tlr7 | FAM 5′-CCAAGAAAATGATTTTAATAAC-3′ |

Predeveloped TaqMan assay reagents from Applied Biosystems Cxcl10, Gapdh, 18srRNA

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparison between single groups were performed using Student’s t-test. Otherwise analysis of variance using posthoc Bonferroni‘s correction was used. A value of P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Poly I:C RNA Induces the Production of Il-6 and IFN-β in Glomerular Mesangial Cells

Murine and human mesangial cell lines express TLR3 and produce Il-6 on exposure to poly I:C RNA, a synthetic mimic of viral double-stranded RNA.11,14 To verify this observation in primary mesangial cells, we used >99% pure mesangial cell cultures isolated from glomerular preparations of C57BL/6 mice as described in Materials and Methods. As expected, incubation with increasing doses of poly I:C RNA induced Il-6 mRNA expression in primary mesangial cells, which peaked at 3 hours after poly I:C RNA stimulation and was maximal at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. (Figure 1). At 6 hours, Il-6 mRNA levels declined below baseline expression (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mesangial cells produce Il-6 and IFN-β on exposure to poly I:C RNA. Mesangial cells were prepared from C57BL/6 mice as described in Materials and Methods. Cultured mesangial cells were stimulated with increasing doses of poly I:C RNA, and Il-6 mRNA expression was determined by real-time RT-PCR after 1, 3, and 6 hours of stimulation with increasing doses of poly I:C RNA as indicated. Data are expressed as the ratio of Il-6 mRNA per respective 18S rRNA expression. Data are means ± SEM from three experiments, each analyzed in duplicate. ∗P < 0.05 versus medium control.

Mesangial Cells Produce High Amounts of IFN-α and IFN-β when Exposed to Poly I:C RNA Complexed with Cationic Lipids in an Tlr3/Trif-Independent Pathway

The recognition of viral RNA in DCs can involve Tlr3/Trif-dependent and Tlr3/Trif-independent pathways.5,6,7,15 To assess the contribution of the Tlr3-dependent pathway for RNA recognition in mesangial cells, we compared the poly I:C RNA-induced Il-6 production in mesangial cells from wild-type and Trif-mutant mice. In wild-type mesangial cells, poly I:C RNA induced the secretion of low amounts but still doubles Il-6 levels as compared with medium (Figure 2A). Lack of functional Trif completely blocked this effect (Figure 2A). At higher doses of poly I:C RNA, Il-6 secretion declined below medium levels consistent with mesangial cell death. In DCs, the Tlr3/Trif-independent signaling pathway was shown to be specifically activated when the viral RNA is complexed with cationic lipids.7 In fact, complexes of cationic lipids with very small doses of poly I:C RNA activated mesangial cells to produce high levels of Il-6 independent of the presence of functional Trif (Figure 2A). Furthermore, complexes of cationic lipids with poly I:C RNA activated mesangial cells to produce high levels of IFN-α and IFN-β independent of Trif (Figure 2, B and C). Mesangial cells did not produce IFN-γ on either of the stimuli tested (data not shown). These data show that mesangial cells can produce large amounts of type I IFN when exposed to poly I:C RNA complexed with cationic lipids via a Trif-independent pathway.

Figure 2.

Viral dsRNA complexed with cationic lipids activates mesangial cells to produce high amounts of Il-6 and type I IFN via a Trif-independent pathway. Primary mesangial cells were isolated from wild-type C56BL/6 mice and Trif-mutant mice as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were stimulated with increasing doses of poly I:C (pI:C) RNA alone or complexed with the cationic lipid (CL) Lipofectamine. Supernatants were harvested after 24 hours and analyzed by ELISA for the following mediators: Il-6 (A), IFN-α (B), and IFN-β (C). Data are means ± SEM from three experiments each analyzed in duplicate and presented in a logarithmic scale. ∗P < 0.05 wild-type versus medium; ∗∗P < 0.05 Trif-mutant versus wild type.

Mesangial Cells Express the Cytosolic Viral RNA Recognition Receptors Mda5 and Rig-I but Only Mda5 Mediates poly I:C RNA Recognition

Trif-independent recognition of poly I:C RNA in DCs involves the cytosolic Rig-like helicases Rig-I and Mda5.6,7 Primary mesangial cells expressed Rig-I and its mitochondrial adaptor IFN-β promoter stimulator-1 but not Mda5 mRNA under basal culture conditions (Figure 3A). Rig-I and Mda5 mRNA expression markedly increase on stimulation with IFN-β like Tlr3 within 6 hours while that of IFN-β promoter stimulator-1 was rather down-regulated (Figure 3A). By contrast, exposure to increasing doses of Il-6 rather down-regulated Rig-I and Mda5 (Figure 3B). At the protein level, mesangial cells showed basal expression of Tlr3, Rig-I, and Mda5 (Figure 3C). Stimulation with poly I:C RNA/cationic lipid complexes transiently reduced Tlr3 and increased Mda5, whereas Rig-I expression was rather stable over a period of 24 hours (Figure 3C). Which of the two viral RNA recognition receptors mediates poly I:C RNA recognition in the cytosol? We used Mda-5- and Rig-I-specific siRNA to answer this question. Each of the specific siRNAs significantly reduced the mRNA levels of its target in mesangial cells but only knockdown of Mda5 impaired the Il-6 or Cxcl10 response on stimulation with poly I:C RNA/cationic lipid complexes as compared with transfection with nonspecific control RNA (Figure 3, D and E). Knockdown of Mda5 did not affect Il-6 or Cxcl10 induction on exposure to uncomplexed poly I:C RNA further demonstrating that cytosolic uptake is mandatory for Mda5 signaling. Taken together, type I IFN induces the expression of Rig-I and Mda5 in mesangial cells, but only Mda-5 is required for the triggering cyokine and chemokine release on cytosolic poly I:C RNA.

Figure 3.

Cytosolic RNA receptors in mesangial cells. A: Primary mesangial cells were cultured in the presence or absence of 2000 U/ml IFN-β (A) or increasing doses of rmIl-6 (B). After 6 hours, mRNA was harvested, and real-time RT-PCR was performed for various RNA recognition molecules, as indicated. Data are expressed as the ratio of the specific mRNA per respective 18S rRNA expression. n.d., not detected; ∗P < 0.05 versus medium. C: Primary mesangial cells were cultured in the presence or absence of poly I:C (pI:C) RNA/CL complexes over various time periods, as indicated. Unstimulated J774 macrophages served as a positive control. Protein expression of Tlr3, Rig-I, and Mda5 was determined by Western blot. β-Actin expression was used as a loading control. D and E: Mesangial cells were transfected twice with Mda-5-specific siRNA (D), Rig-I-specific siRNA (E), or nonspecific control RNA as described in Materials and Methods. Knockdown efficacy was tested by real-time PCR for the respective target (left panels). Impact of knockdown on pI:C recognition was determined by real-time PCR for Il-6 or Cxcl10 after 6 hours of incubation with 3 μg of pI:C RNA either complexed with cationic lipid (CL) or uncomplexed. Data represent means from three experiments ± SEM; ∗P < 0.05 versus nonspecific control RNA (n.c.).

Poly I:C RNA/Cationic Lipid-Induced Activation of Mesangial Cells Involves a Type I IFN Autocrine-Paracrine Activation Loop

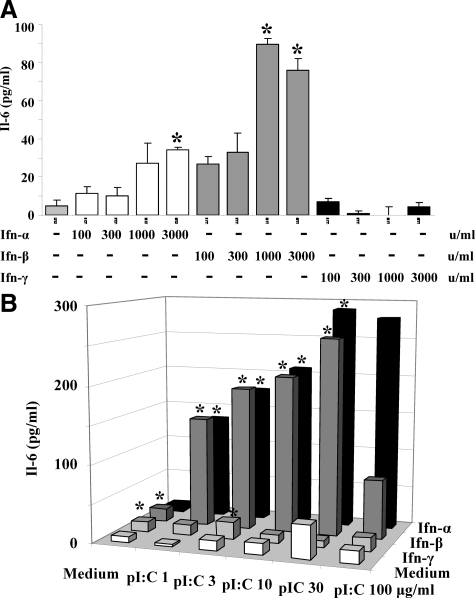

In DCs, the recognition of viral RNA induces the release of type I IFN, which enhances subsequent Tlr signaling via autocrine-paracrine recognition of type I IFN involving the type I IFN receptor (IFNR) and Stat1 phosphorylation.16 Therefore, we questioned whether this autocrine-paracrine activation loop does also apply to mesangial cells. Exposing mesangial cells to increasing doses of IFN-α, IFN-β, or IFN-γ revealed that only IFN-α or IFN-β induced Il-6 release in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4A). Does IFN enhance viral dsRNA-mediated activation of mesangial cells? Prestimulation of mesangial cells with 1000 units of either IFN-α and IFN-β for 24 hours markedly enhanced the Il-6 response induced by poly I:C RNA (Figure 4B). IFN-γ had no significant effect on the Il-6 response induced by poly I:C RNA. Obviously, type I but not type II IFN enhanced the poly I:C RNA-mediated activation of mesangial cells in association with an induction of the RNA recognition machinery. To demonstrate that type I IFN produced by the mesangial cells can mediate this autocrine mechanism, we stimulated primary mesangial cells with poly I:C RNA/cationic lipid complexes in the absence or presence of increasing doses on antibodies that neutralize the functions of IFN-α and IFN-β. By blocking both type I IFN, the poly I:C RNA/cationic lipid-induced Il-6 production was almost completely prevented (Figure 5A). Furthermore, primary mesangial cells from IFNR-deficient mice produced much less Il-6 on poly I:C RNA/cationic lipid exposure as mesangial cells from wild-type mice, respectively (Figure 5B). These data show that poly I:C RNA-induced activation of mesangial cells depends on the production and recognition of type I IFN, ie, an autocrine-paracrine activation loop.

Figure 4.

IFN-α and -β enhance Il-6 release and RNA recognition in mesangial cells. A: Primary mesangial cells were stimulated with increasing doses of IFN-α-γ as indicated. Supernatants were harvested after 24 hours and analyzed by ELISA for Il-6. Data represent means ± SEM from three independent experiments. ∗P < 0.05 versus medium. B: Mesangial cells were prestimulated with 1000 U/ml IFN-α, -β, or -γ for 24 hours. The prestimulated cells were then exposed to increasing doses of pI:C RNA as indicated. Supernatants were harvested after 24 hours and analyzed by ELISA for Il-6. Data represent means ± SEM; ∗P < 0.05 versus medium.

Figure 5.

Poly I:C (pI:C) RNA-induced Il-6 release in mesangial cells depends on type I IFNs. A: Primary mesangial cells were stimulated with increasing doses of pI:C RNA/cationic lipid (CL) complexes as indicated. At given concentrations of such complexes, increasing doses of neutralizing antibodies against IFN-α and IFN-β were added. B: Mesangial cells were prepared from wild-type or IFNa-R−/− mice, and cells were stimulated as before. In A and B, supernatants were harvested after 24 hours and analyzed by ELISA for Il-6. Data are means ± SEM from four experiments each analyzed in duplicate. ∗P < 0.05 versus no IFN-α and IFN-β antibody group.

Poly I:C RNA-Cationic Lipid Complexes Induce Mesangial Cell Death

Viral recognition often triggers a signal for apoptotic cell death that is thought to contribute to the control of viral replication and spreading, which is supported by our finding that exposure to higher doses of poly I:C RNA is associated with a decline in Il-6 and IFN production. In fact, the number of proliferating mesangial cells was reduced on exposure to increasing doses of poly I:C RNA (Figure 6A). The dose effect was enhanced up to a 100-fold when pI:C RNA was complexed to cationic lipids (Figure 6A). Poly I:C RNA-induced cell death involved the extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis pathways because poly I:C RNA-induced cell death was prevented by caspase-8 or -10 and caspase-9 or -2 inhibitors, respectively (Figure 6B). Again, poly I:C RNA-induced cell death largely depended on the autocrine-paracrine type I IFN activation loop because the impact of poly I:C RNA/cationic lipid complexes on cell proliferation was blunted in IFNa-R-deficient mesangial cells (Figure 6C). Thus, triggering a death pathway is part of the innate antiviral response program of mesangial cells on exposure to higher concentrations of viral RNA, especially when it reaches the intracellular cytosol.

Figure 6.

Cytosolic recognition of viral dsRNA-induced mesangial cells death. A: Primary mesangial cells were stimulated with increasing doses of poly I:C (pI:C) RNA with or without cationic lipid (CL) as indicated. After 72 hours, the number of proliferating cells was determined by a bioluminescence assay as described in Materials and Methods. ∗P < 0.05 versus medium; ∗∗P < 0.05 versus sine CL. B: Primary mesangial cells were stimulated with poly I:C RNA+CL (pIC) in the presence or absence of the caspase-2 inhibitor Z-VDVAD-FMK (CI, 5 μg/ml), the caspase-8 inhibitor Ac-IETD-CHO (CI, 5 μg/ml), the caspase-9 inhibitor Z-LEHD-FMK (CI, 5 μg/ml), and the caspase-10 inhibitor Z-AEVD-FMK (CI, 5 μg/ml). After 72 hours, the number of proliferating cells was determined by a bioluminescence assay. ∗P < 0.05 versus pI:C RNA. Note that all caspase inhibitors prevented pI:C RNA+CL-induced inhibition of cell growth. C: In similar experiments, mesangial cells from IFNa-R+/+ (black bars) and IFNa-R−/− cells (white bars) were stimulated with pI:C/cationic lipid complexes. ∗P < 0.05 versus IFNa-R+/+.

Poly I:C RNA-Cationic Lipid Complexes Induce Diffuse Focal Glomerular Necrosis in Nephrotoxic Serum Nephritis in Mice

To test the in vivo relevance of the proposed mechanism, we injected C57BL/6 mice with autologous nephrotoxic serum nephritis with either vehicle, cationic lipids, poly I:C RNA or poly I:C RNA/cationic lipid complexes. The doses of nephrotoxic serum used for these experiments usually cause robust immune complex glomerulonephritis and massive albuminuria after 21 days. Injection of poly I:C RNA and poly I:C RNA/cationic lipid complexes induced proteinuria at day 7, which progressed to massive albuminuria at day 10 so that the mice had to be sacrificed because of massive ascites as a marker of nephrotic syndrome (Figure 7, A–C). However, only poly I:C RNA/cationic lipid complexes led to severe global segmental necrotic glomerular lesions at 10 days (Figures 7). These histopathological changes were associated with increased renal mRNA expression of Rig-I, Mda5, and Cxcl10 in poly I:C RNA-injected mice (Figure 8, A and B).

Figure 7.

Nephrotoxic serum nephritis in C57BL/6 mice. A: Urinary albumin/creatinine ratios were determined from all groups of mice at days 7 and 10 as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent means ± SEM; ∗P < 0.05 versus day 0, ∗∗P < 0.05 versus vehicle on day 10. B: Focal glomerular necrosis was quantified on periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-stained renal sections from all groups on day 10 applying a semiquantitative score from 0 to 3 in 15 glomeruli per section. Data represent means ± SEM; ∗∗P < 0.05 pI:C RNA/cationic lipid versus pI:C; ∗P < 0.05 versus vehicle. C: Renal sections from mice of all groups were stained with PAS. Representative images were taken at an original magnification of ×100 and ×400. Focal necrosis is indicated by asterisk.

Figure 8.

Intrarenal gene expression in nephrotoxic serum nephritis. Real-time RT-PCR was performed for RNA recognition receptors (A) and IFN-related genes (B) on total kidney RNA isolates from four mice of each group. Data are expressed as the ratio of the specific mRNA per respective 18S rRNA expression; ∗P < 0.05 versus vehicle group.

Discussion

The glomerular filtration process exposes mesangial cells to circulating micro- and macromolecules of the intravascular compartment, including viral particles during viral infections. RNA can be protected from RNase digestion when being complexed to proteins such as Igs or nucleoproteins.17,18,19 In glomerulonephritis, such immune complexes are often deposited in the glomerular mesangium where they are taken up by glomerular mesangial cells.20 Studies from our group showed that poly I:C RNA activates human and murine mesangial cells to produce Il-6 and Ccl2 in vitro and in vivo, which we confirmed here at the mRNA level for Il-6. Interestingly, Il-6 mRNA expression fell below the baseline level after 6 hours, but on the protein level, Il-6 production was sustained at 24 hours. The effect of poly I:C RNA was previously attributed to Tlr3, ie, the only RNA-specific Tlr expressed by mesangial cells.11,16 In contrast to our previous studies with a murine mesangial cell line, primary mesangial cells do not constitutively express Tlr3.11 Furthermore, primary mesangial cells produce only small amounts of Il-6 on poly I:C RNA challenge unless activation by IFN-β. However, viral dsRNA can induce the maturation of DCs independent of the Tlr3/Trif pathway.8,21 The discovery of Rig-I and Mda5 as cytosolic viral dsRNA receptors7 suggests an alternative pathway how viral dsRNA could activate mesangial cells. In fact, in nonimmune cells, viral dsRNA appears to preferentially activate the cytosolic Rig-I route rather than the Tlr3 pathway.8,21

Here we provide experimental evidence that Tlr3/Trif-dependent and Tlr-independent recognition of viral dsRNA both can trigger specific antiviral immunity in mesangial cells. Viral dsRNA induced low levels of IFN-β in mesangial cells, a response that was only in part mediated through the Tlr3/Trif-signaling pathway in intracellular endosomes. To test the significance of Tlr-independent RNA recognition requires transfection of viral dsRNA into the intracellular cytosol, which might also be the predominant route of RNA delivery on direct viral infection of cells. Experimentally, we complexed the poly I:C RNA to cationic lipids, which is as effective as other ways of transfection.7,22,23 Interestingly, transfecting poly I:C RNA triggers the production of large amounts of IFN-α and IFN-β as well as cell death of mesangial cells, which involves the apoptosis pathway. Remarkably, poly I:C RNA/cationic lipid complexes induced high levels of Il-6 and type I IFN despite mesangial cell apoptosis unless high doses of poly I:C RNA were applied. Our in vivo studies support the concept that poly I:C RNA/cationic lipid complexes more potently aggravate glomerulonephritis in association with increased renal IFN-related cytokine expression as well as enhanced glomerular cell death. However, only a mesangial cell-specific knockout of Trif could ultimately prove that the Trif-independent activation of mesangial cells proposed by our in vitro studies applies in vivo.

Cytokine secretion as well as apoptosis both are considered to be important local mechanisms to control viral infection. These Tlr3/Trif-independent effects are suggestive for Rig-I- or Mda5-dependent RNA recognition.7 In fact, Rig-I and Mda5 are both expressed in mesangial cells, and Rig-I was recently shown to be expressed in human lupus nephritis,24 a disease state closely linked to type I IFN signaling.25,26 However, our studies with Rig-I- and Mda5-specific siRNA clearly identified Mda5 and not Rig-I as the cytosolic poly I:C RNA receptor in murine mesangial cells. It is of note that mesangial cells produce IFN-α and IFN-β but not IFN-γ, ie, type II IFN, which should relate to the different functions of type I and type II IFN in immunity.2 Hence, poly I:C RNA stimulates glomerular mesangial cells to produce type I IFN, especially when activating Mda5 as part of the Tlr-independent RNA recognition pathway in the cytosol.

When pDCs produce type I IFN, these modulate the function of other cells as well as of the pDC itself, ie, an autocrine-paracrine regulatory mechanism.2,27 For example, in type I IFNR-deficient pDCs, the challenge with poly I:C RNA results in much lower cytokine responses as compared with wild-type pDCs.16 Obviously, the secretion of type-I IFN enhances Tlr signaling in an autocrine-paracrine manner in pDCs, the professional IFN-producing cells. This mechanism was also shown to apply for endothelial and epithelial cells.28 We therefore hypothesized that the same mechanism enhances antiviral responses in glomerular mesangial cells exposed to poly I:C RNA. In fact, mesangial cells produce Il-6 on exposure to IFN-α and IFN-β. The presence of either IFN-α or -β enhanced the poly I:C RNA-induced production of Il-6. The ultimate evidence for an autocrine loop came from blocking intrinsic type I IFN with neutralizing antibodies or by genetic deletion of the type I IFNR in mesangial cells, which dramatically reduced the amount of IL-6 produced on exposure to viral dsRNA.

Hence, viral dsRNA activates mesangial cells to produce type I IFN, which enhances the production of proinflammatory cytokines like Il-6 in an autocrine-paracrine manner via the type I IFNR. In this process, IFN-β induces innate viral RNA recognition receptors in primary mesangial cells just like Tnf/IFN-γ previously shown for cell lines of murine and human mesangial cells.14,29 The pathogenic relevance of this mechanism for glomerulonephritis was recently demonstrated by Jørgensen et al30 autoimmune B6.Nba2 mice and (B6Nba2 × NZW)F1 mice deficient for the type I IFNR failed to develop glomerulonephritis, although the mice had substantial glomerular immune complex deposits.29

In summary, poly I:C RNA stimulates glomerular mesangial cells to produce large amounts of type I IFN, especially when being delivered into the intracellular cytosol where it can interact with Mda5. Type I IFN production enhances the dsRNA-induced production of proinflammatory mediators such as Il-6 as well as cell death in a positive autocrine amplification loop. Thus, the recognition of viral RNA triggers type I IFN in glomerular mesangial cells, which we propose as a novel pathomechanism for glomerular pathology in viral infection-associated glomerulonephritis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Heike Weighardt (Department of Surgery, Technische Universität, Munich, Germany) for providing the IFNa-R-deficient and control 129 Sv/Ev mice. The expert technical assistance of Ewa Radomska, Iana Mandelbaum, and Dan Draganovic is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Hans-Joachim Anders, Medizinische Poliklinik, Universität München, Pettenkoferstr. 8a, 80336 München, Germany. E-mail: hjanders@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (AN372/9-1 and GRK 1202; to H.-J.A.). K.F., R.A., and J.L. were graduate fellows of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft GRK 1202.

Parts of this project were prepared as a doctoral thesis at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Munich, by K.F.

References

- Lai AS, Lai KN. Viral nephropathy. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:254–262. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theofilopoulos AN, Baccala R, Beutler B, Kono DH. Type I interferons (α/β) in immunity and autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:307–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark GR, Kerr LM, Williams BR, Silvemann RH, Schreiber RD. How cells respond to interferons. Ann Rev Biochem. 1998;67:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortman K, Liu YJ. Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:151–161. doi: 10.1038/nri746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama M, Kikuchi M, Natsukawa T, Shinobu N, Imaizumi T, Miyagishi M, Taira K, Akira S, Fujita T. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:730–737. doi: 10.1038/ni1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Matsui K, Uematsu S, Jung A, Kawai T, Ishii KJ, Yamaguchi O, Otsu K, Tsujimura T, Koh CS, Reis e Sousa C, Matsuura Y, Fujita T, Akira S. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Owen DM, Jiang F, Marcotrigiano F, Gale M., Jr Innate immunity induced by composition-dependent RIG-I recognition of hepatitis C virus RNA. Nature. 2008;454:523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature07106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang KS, Recher M, Junt T, Navarini AA, Harris NL, Freigang S, Odermatt B, Conrad C, Ittner LM, Bauer S, Luther SA, Uematsu S, Akira S, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Toll-like receptor engagement converts T cell autoreactivity into overt autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2005;11:138–145. doi: 10.1038/nm1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder M, Bowie AG. TLR3 in antiviral immunity: key player or bystander? Trends Immunol. 2005;26:462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patole PS, Grone HJ, Segerer S, Ciubar R, Belemezova E, Henger A, Kretzler M, Schlondorff D, Anders HJ. Viral double-stranded RNA aggravates lupus nephritis through Toll-like receptor 3 on glomerular mesangial cells and antigen-presenting cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1326–1338. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004100820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoebe K, Du X, Georgel P, Janssen E, Tabeta K, Kim SO, Goode J, Lin P, Mann N, Mudd S, Crozat K, Sovath S, Han J, Beutler B. Identification of Lps2 as a key transducer of MyD88-independent TIR signalling. Nature. 2003;424:743–748. doi: 10.1038/nature01889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vielhauer V, Stavrakis G, Mayadas TN. Renal cell-expressed TNF receptor 2, not receptor 1, is essential for the development of glomerulonephritis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1199–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI23348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wörnle M, Schmid H, Banas B, Merkle M, Henger A, Roeder M, Blattner S, Bock E, Kretzler M, Gröne HJ, Schlöndorff D. Novel role of Toll-like receptor 3 in hepatitis C-associated glomerulonephritis. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:370–385. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier G, Humbert M, Deauvieau F, Scuiller M, Hiscott J, Bates EE, Trinchieri G, Caux C, Garrone P. A type I interferon autocrine-paracrine loop is involved in Toll-like receptor-induced interleukin-12p70 secretion by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1435–1446. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau CM, Broughton C, Tabor AS, Akira S, Flavell RA, Mamula MJ, Christensen SR, Shlomchik MJ, Viglianti GA, Rifkin IR, Marshak-Rothstein A. RNA-associated autoantigens activate B cells by combined B cell antigen receptor/Toll-like receptor 7 engagement. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1171–1177. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda K, Richez C, Maciaszek JW, Agrawal N, Akira S, Marshak-Rothstein A, Rifkin IR. Murine dendritic cell type I IFN production induced by human IgG-RNA immune complexes is IFN regulatory factor (IRF)5 and IRF7 dependent and is required for IL-6 production. J Immunol. 2007;178:6876–6885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savarese E, Chae OW, Trowitzsch S, Weber G, Kastner B, Akira S, Wagner H, Schmid RM, Bauer S, Krug A. U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein immune complexes induce type I interferon in plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TLR7. Blood. 2006;107:3229–3234. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Guerrero C, Lopez-Armada MJ, Gonzalez E, Egido J. Soluble IgA and IgG aggregates are catabolized by cultured rat mesangial cells and induce production of TNF-α and IL-6, and proliferation. J Immunol. 1994;153:5247–5255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Uematsu S, Matsui K, Tsujimura T, Takeda K, Fujita T, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Cell type-specific involvement of RIG-I in antiviral response. Immunity. 2005;23:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun CS, Vetro JA, Tomalia DA, Koe GS, Koe JG, Middaugh CR. The structure of DNA within cationic lipid/DNA complexes. Biophys J. 2003;84:1114–1123. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74927-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetson DB, Medzhitov R. Recognition of cytosolic DNA activates an IRF3-dependent innate immune response. Immunity. 2006;24:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Imaizumi T, Tsugawa K, Ito E, Tanaka H. Expression of retinoic acid-inducible gene-I in lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:2407–2409. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow MK, Kirou KA. Interferon α in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16:541–547. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000135453.70424.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnblom L, Alm GV. An etiopathogenic role for the type I IFN system in SLE. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:427–431. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01955-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K, Sakaguchi S, Nakajima C, Watanabe A, Yanai H, Matsumoto M, Ohteki T, Kaisho T, Takaoka A, Akira S, Seya T, Taniguchi T. Selective contribution of IFN-α/β signaling to the maturation of dendritic cells induced by double-stranded RNA or viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10872–10877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934678100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissari J, Siren J, Meri S, Julkunen I, Matikainen S. IFN-α enhances TLR3-mediated antiviral cytokine expression in human endothelial and epithelial cells by up-regulating TLR3 expression. J Immunol. 2005;174:4289–4294. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patole PS, Pawar RD, Lech M, Zecher D, Schmidt H, Segerer S, Ellwart A, Henger A, Kretzler M, Anders HJ. Expression and regulation of Toll-like receptors in lupus-like immune complex glomerulonephritis of MRL-Faslpr mice. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3062–73. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen TN, Roper E, Thurman JM, Marrack P, Kotzin BL. Type I interferon signaling is involved in the spontaneous development of lupus-like disease in B6.Nba2 and (B6.Nba2 × NZW)F1 mice. Genes Immun. 2007;8:653–662. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]