Abstract

Eosinophils expressing indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO) may contribute to T-helper cell (Th)2 predominance. To characterize human thymus IDO+ eosinophil ontogeny relative to Th2 regulatory gene expression, we processed surgically obtained thymi from 22 children (age: 7 days to 12 years) for immunohistochemistry and molecular analysis, and measured cytokine and kynurenine levels in tissue homogenates. Luna+ eosinophils (∼2% of total thymic cells) decreased in number with age (P = 0.02) and were IDO+. Thymic IDO immunoreactivity (P = 0.01) and kynurenine concentration (P = 0.01) decreased with age as well. In addition, constitutively-expressed interleukin (IL)-5 and IL-13 in thymus supernatants was highest in youngest children. Eosinophil numbers correlated positively with expression of the Th2 cytokines IL-5, IL-13 (r = 0.44, P = 0.002), and IL-4 (r = 0.46, P = 0.005), transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription-6 (r = 0.68, P = 0.001), and the chemokine receptor, CCR3 (r = 0.17, P = 0.04), but negatively with IL-17 mRNA (r = −0.57, P = 0.02) and toll-like receptor 4 expression (r = −0.74, P = 0.002). Taken together, these results suggest that functional thymic IDO+ eosinophils during human infant life may have an immunomodulatory role in Th2 immune responses.

It is recognized that infants are born with an immature immune system with considerable maturation occurring during childhood.1 Fetal immune responses are dominated by T-helper cell (Th)2 cytokine production with characteristically negligible interferon (IFN)γ production,2 in the absence of appropriate environmentally-driven postnatal maturation of Th1 immunity. Studies with hepatitis B virus and poliovirus vaccines have shown that although Th2 responses are similar following primary vaccination in adults and infants, there is an enhanced memory Th2 response in vaccinated infants compared with adult vaccines.3 Thus, the propensity to develop a Th2 response to environmental allergens during early life may be an important factor in deviating subsequent immune responses toward the selection of persistent, potentially pathogenic Th2 polarized memory. This highlights the importance of developmental factors associated with postnatal maturation of overall immune competence.

The thymus is a primary lymphoid organ, critical for the development of normal adaptive immunity. Although the immunological importance of the thymus may partially diminish with age, its function persists even in later life. A critical aspect of the education of the immune system in the thymus is acquiring tolerance to self-antigens while mounting carefully-controlled adaptive responses against foreign antigens.4 The precise mechanisms that regulate human thymic instruction of immune maturation after birth remains poorly understood; even less in humans where there is a paucity of available data. Conversely, studies in mice have shown that thymic selection of CD4+ T cells plays a role in the regulation of immune response to environmental proteins,5 suggesting that dysregulation of thymic T cell selection is a potential factor in the development of allergic disease.

Allergic asthma is often defined as a complex set of chronic inflammatory airway syndromes characterized by eosinophilic infiltration and airway hyperreactivity. Characteristically associated with host defense against parasitic helminth infection (associated with activation, exocytosis and release of toxic proteins), eosinophils also synthesize, store and release a wide range of potent pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and growth factors, known to be involved in regulating the allergic response. Over the last few years, a new paradigm has emerged describing eosinophils as significant contributors to both localized innate and acquired immunity associated with Th1 and Th2 immune profiles and systemic adaptive responses.6 Eosinophils were recently shown to act as antigen-presenting cells since they express several important co-stimulatory molecules,7 further supporting the notion of their modulatory role in adaptive immune responses. Eosinophils home naturally to the thymus in neonates in the absence of any detectable “danger signal”8 and data from mice suggest that thymic eosinophils (along with thymic dendritic cells) may be involved in the education of thymocytes.9

Our own studies have indicated that eosinophils in asthmatic airways may promote Th1/Th2 imbalance (in favor of Th2) through expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO).10 IDO is an intracellular enzyme that depletes tryptophan (an essential amino acid for cell proliferation and protein biosynthesis). IDO-mediated tryptophan catabolism generates a cascade of pharmacologically-active catabolites known collectively as kynurenines (KYNs), which have been shown to be involved in immune regulation.11 Previous studies have shown that KYNs exert immunosuppressive effects through induction of apoptosis and inhibition of cell proliferation of Th1, but not Th2 cells.12 A recent study from our group showed that in vivo, inhibition of IDO by 1-methyl tryptophan resulted in reversal of oral immune tolerance in an ovalbumin (OVA)-induced murine model. Repeated intranasal administration of OVA generated tolerance and prevented a subsequent sensitization to OVA via the i.p. route. However, tolerance was abolished in 1-methyl tryptophan-treated mice following an i.p. injection of a mixture of KYN and hydroxyanthranilic acid; two potent IDO-induced tryptophan catabolites. This suggests that products of tryptophan catabolism have an important role in prevention of sensitization to potential allergens in the respiratory airway.13

Further evidence supporting a role for eosinophils in adaptive immunity was provided in a recent study in mice devoid of eosinophils (the transgenic PHIL mouse model).14,15 PHIL mice sensitized and challenged with allergen (OVA) showed reduced airway Th2 cytokine levels compared with OVA-treated wild-type. This also correlated with a reduced capacity to recruit effector T cells to the airways. In contrast, adoptive transfer of T cells and eosinophils from OVA sensitive mice into PHIL mice resulted in increase in effector T cells and airway Th2 immune responses. This suggests, therefore, that eosinophils are essential for recruitment of effector T cells into the airway.15 However, there are no studies to date on the role of eosinophils and their products in influencing the immunological processes occurring in the human thymus. In this study, we examined the hypothesis that the presence of eosinophils in the thymus vary with age and that eosinophil numbers and their IDO expression correlate with Th2 but not Th1 markers in early life.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

We processed 22 thymi from children (age range: 7 days to 12 years) who were admitted to Princess Margaret Hospital in Perth for elective open-heart surgery for various congenital heart conditions. A major part of the thymus gland is routinely removed and discarded to provide surgical access for cardiopulmonary bypass. Subjects were subgrouped into four age-groups (<6 months, n = 7; 6 to 12 months, n = 5; 1 to 5 years, n = 7; and >5 years, n = 3). All individuals were free of any viral or bacterial infections during the month before surgery. Informed consent was obtained from parents of all of the children donors and the study was approved by the Princess Margaret Hospital Ethics Committee. All of the human studies were conducted according to the Helsinki protocol and the National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines.

Tissue Preparation

Two separate small portions of surgically resected thymus (∼1 cm3) were processed either for histological and immunocytochemistry analysis, for flow cytometry or RNA isolation (see details below). Single cell suspension was prepared by mechanically disturbing the thymic tissue using an end of a syringe plunger while tissue was sitting on nylon gauze and submersed in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Cells were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 500g in 4°C and supernatant collected to measure constitutive cytokine protein and KYN levels using sandwich-type time resolved fluorometry as previously described.16 After another two washes in media, half of the cells were either cryopreserved and later used for fluorescence activated cell sorting analysis or were resuspended in 100 μl RNALater (Ambion) and stored at −20°C for later RNA extraction and real-time PCR. Routinely, the time between thymus excision and tissue processing was less than 1 hour.

Histology and Immunocytochemistry

For histological analysis and immunocytochemistry, thymic tissue was fixed for 2 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed in 15% sucrose/phosphate-buffered saline, and paraffin processed using a standard 13-hour overnight schedule on a Shandon Pathcenter tissue processor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Sydney, Australia). Tissue was sectioned at 4-μm thickness onto glass slides. Eosinophil counts were performed using Luna stained sections, which used Hematoxylin-Biebrich Scarlet solution to demonstrate eosinophil granules against a blue background.17 To confirm IDO expression by eosinophils, we performed a double immunohistochemical stain using the labeled streptavidin-biotin and alkaline phosphatase/anti-alkaline phosphatase technique on paraffin sections as previously described18 using i) an in-house generated mouse monoclonal antibody19 directed against human eosinophil major basic protein (clone BMK-13, 1:20) and ii) monoclonal antibody raised in mouse against human IDO (Clone 10.1) (Upstate, NY) (1:200). BMK13-positive eosinophils appeared red and IDO-positive cells as brown. As a positive control, sections were also stained with the macrophage marker, CD68 (Clone PG-M1) (DAKO, Kingsgrove, Australia) (1:75) as these cells are also a known source of IDO. For negative controls, the primary antibody step was omitted. Total number of Luna+ eosinophils and IDO+ eosinophils were counted on 10 random, non-overlapping grids from all regions of the thymus (trabecular, capsular, medullary, and cortico-medullary regions) using a Leica DM LB 100L light microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) with ×40 magnification and an eyepiece graticule of 0.202 mm2.

For immunofluorescence we used BMK-13 monoclonal antibody conjugated to BODIPY FL (green, C) (Invitrogen, CA) and IDO human antibody conjugated to tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate (red, D) (ZYMED Laboratories, Invitrogen, CA). Co-localization of eosinophils with IDO was visualized as yellow (red/green combined) immunostaining. For negative controls, BMK-13 and IDO antibodies were replaced with the same concentration of their respective isotype-matched control antibodies (IgG1 for BMK-13 and IgG1, IgG2α, IgG2β, and IgG3 for IDO) (Dako, NSW).

KYN-positive cells were identified on frozen tissue sections (7 μm) using a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against L-KYN (1:3200) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Detection system used was EnVision Dual Link System HRP (Dako) and visualized with Dako Liquid DAB+ Substrate-Chromogen System. Slides were counterstained using Carazzi’s Hematoxyline, sections dehydrated and coverslipped in Ultramount permanent mountant. KYN-positive cells appeared brown.

Flow Cytometry

To phenotype the cell populations in the human thymus we stained thymocytes with mAbs against CD3, CD4, CD8 (T cells), CCR3 (CD193, receptor for eosinophil chemo-attractant eotaxin); directly conjugated to fluorochromes (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Indirect intracellular staining for eosinophils major basic protein was achieved using BMK-1319 following 4% paraformaldehyde fixation and permeabilization with 0.01% Saponin. Alexa488-Chicken-anti-mouse (BD Biosciences) was used for indirect detection of BMK-13 intracellular staining. Samples were collected using a FACSCanto (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer and analyzed using WinMDI V2.8 software (SCRIPPS Research Institute, La Jolla, CA).

RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cell pellets using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Clifton Hill, AUS) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Reverse transcription was performed using the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen, Doncaster VIC AUS) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with oligo-dT (Promega, Madison, WI) and Superasin (Geneworks, Hindmarsh SA, Australia). Intron-spanning primers were designed in-house using Primer Express Software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA). Reverse transcribed RNA samples were diluted 1:5 and quantitated by real-time PCR using QuantiTect SYBR Green Master Mix (Qiagen) on the ABI PRISM 7900HT (Applied Biosystems). Melting and dissociation curve analysis was used to confirm the specificity of product amplification. Relative copy numbers were determined by 10-fold serial dilutions of plasmid or PCR product standard curves and normalized to the endogenous reference gene ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2D2, which was previously validated as a house-keeping gene for expression profiling of T cell differentiation using quantitative real-time (RT)-PCR.20 RT-PCR was used to measure constitutive or basal mRNA expression of IDO, Th1 (T-bet, IFNγ), Th2 (GATA-3, signal transducer and activator of transcription [STAT]-6, interleukin [IL]-4, IL-5, IL-13, CCR3 and Fractalkine), and genes associated with regulatory T cells (FOXP3, IL-10), as well as innate receptors (toll-like receptors [TLR]-2, -4, -7, -9, MD-2) in thymocytes.

Cytokine and Chemokine Measurements

Supernatant was used to measure basal interleukin IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor protein levels using in-house time-resolved fluorometry. PharMingen (San Jose, CA) antibody pairs were used for capture and detection and standard curves were generated by using serial dilutions of antibodies. Europium–labeled streptavidin and enhancement solution (Delfia Wallac) were used for detection. The limit of detection for time-resolved fluorometry assays was 5 pg/ml.

Kynurenine Measurements in Thymus Homogenates

Kynurenine concentration was measured in the supernatants from thymus homogenates spectrophotometrically.21 Briefly 100 μl of 30% trichloroacetic acid was added to 200 μl of the supernatant, vortexed, and then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 10,000 rpm in 4°C. Supernatant (125 μl) was added to 125 μl of Ehrlich’s reagent (100 mg of p-dimethyl amino benzaldehyde salt in 5 ml of glacial acetic acid) in a microtiter plate well (96-well). Samples were read against a reagent blank with a 492-nm filter in a microplate reader. Results were extrapolated from KYN standards and given in μM.

Statistical Methods

All results are expressed as mean ± SE. Differences between individual groups were analyzed initially using the non-parametric Friedman Test followed by a Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test for paired responses and Mann-Whitney U-test for unpaired responses. Correlations between the number of Luna+ eosinophils or IDO-immunoreactive cells in the thymus with various Th1 and Th2 markers were assessed by using the Spearman or Kendall tau Tests. SPSS statistical package (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analysis. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Eosinophils Are Present in Human Thymus and Their Number Decreases with Age

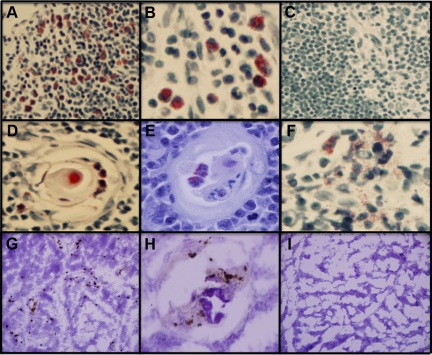

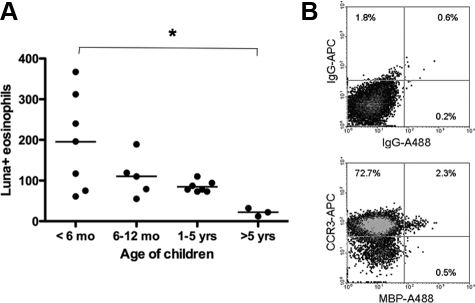

We detected Luna-positive eosinophils in thymi of children (Figure 1A-I). They were primarily located in the medullary region of the thymus (Figure 1A) but also many were found in the trabeculi (Figure 1B) as well as within the structure of Hassall’s corpuscles (Figure 1, D and E). The presence of eosinophils within the corpuscles was frequently observed in thymi from very young children (2 to 4 weeks of age) but was rarely seen in older children (Figure 1C). There was evidence for extracellular deposition of eosinophil granules (Figure 1F). The eosinophils had the characteristic cytoplasmic granules, but many had large and often poorly or unlobed nuclei. Frequency of eosinophils in the thymus decreased with age (P = 0.02) (Figure 2A). Using intracellular staining on fixed and permeabilized cells for MPB and flow cytometry analyses, we determined eosinophil (CCR3+MBP+) frequency to represent ∼2% of the total thymic cell population of which greater than 70% of all cells were CCR3+ (Figure 2B). Staining of non-permeabilized cells indicated that 60% of thymic population was CD3+CD4+CD8+ T cells (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Presence of eosinophils and l-kynurenine in the thymus of young children. Representative histological sections of Luna-positive eosinophils in the thymus of children at 1 week (A), 1 year (B), and 12 (C) years of age. We also detected eosinophils within Hassall’s corpuscles in the early perinatal period, at 2 weeks (D) and 4 weeks (E) after birth. Many of these eosinophils were degranulated (F, age 4 weeks). In the same 4-week-old neonate, kynurenine-immunoreactive cells were detected throughout the thymus (G) including Hassall corpuscles (H). Isotype control staining for kynurenine antibody is shown in (I).

Figure 2.

Age-dependent decrease in the number of eosinophils in the thymus. A: Number of Luna-positive eosinophils in the thymus of children <6 months of age (n = 7), 6 to 12 months of age (n = 5), 1 to 5 years (n = 7), and older than 5 (n = 3). The bar represents group means. *P = 0.02 between <6-month and >5-year age groups. B: Representative flow cytometry density plot illustrating the presence of eosinophils (CCR3+ and MBP+) in the thymus of a 2-week-old infant, which make up approximately 2% of the total cell population.

Eosinophils in the Thymus Express IDO and Their Number Decreases with Age

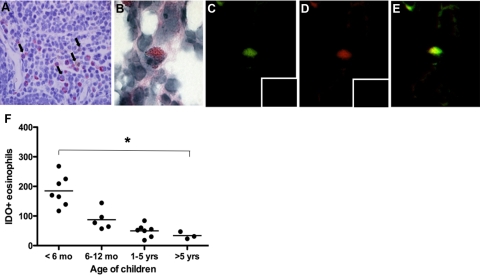

To determine whether eosinophils in the thymus contain IDO, we performed double immunocytochemistry. These immunohistopathological studies demonstrated that the majority of Luna-positive eosinophils (red) were immunoreactive for IDO (brown) (Figure 3A, arrow illustrating co-localization). Figure 3B is a representative eosinophil and confirmation of IDO presence within thymic eosinophils is shown by yellow co-localization in Figure 3E. BMK-13+ eosinophils are depicted as green (Figure 3C) and IDO-positive cells as red (Figure 3D). No immunofluorescence was detected when BMK-13 or IDO antibodies were replaced with their respective control isotype antibodies (inserts in Figure 3, C and D). The number of IDO+ eosinophils in the thymus significantly decreased with age (P = 0.01)(Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Thymic eosinophils contain IDO and their numbers decrease with age. A: Immunodetection of Luna-positive eosinophils (red) and IDO-positive cells (brown) showing the majority of eosinophils to contain IDO (co-localization shown by arrows). B: Confirmatory immunofluorescent staining using BMK-13 monoclonal antibody (directed against human eosinophil major basic protein) conjugated to BODIPY FL (green, C) and IDO human antibody conjugated to rhodamine tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate (red, D) demonstrating co-localization of the two markers (E). Inserts illustrate lack of staining with isotype controls for BMK-13 (IgG1 conjugated to BODIPY FL in C) or IDO (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 conjugated to tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate in D). The number of IDO-positive eosinophils in the thymus decreased with age (F). *P = 0.01 between <6-month and >5-year-age groups.

Basal Cytokine and Chemokine mRNA Expression in the Human Thymus

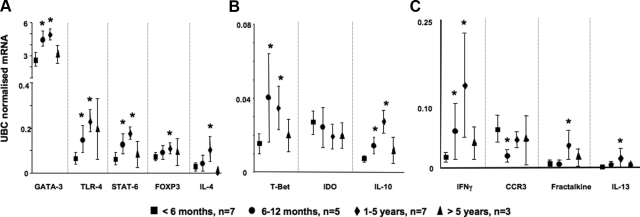

To characterize the cytokine and chemokine milieu in the thymus we used quantitative RT-PCR to measure mRNA levels for genes of interest. We detected high mRNA expression of GATA-3, TLR-4 (innate LPS receptor), STAT-6 (Th2 transcription factors), FOXP3 (suppressor of T cells), and IL-4 (Th2 cytokine) genes in the thymus (Figure 4A) and moderate expression of T-bet (Th1 transcription factor), IDO, and IL-10 (immunoregulatory cytokine) mRNA (Figure 4B). We detected low expression of IFN-γ mRNA, CCR3 mRNA (receptor for the potent eosinophil chemoattractant, eotaxin), fractalkine (CX3C chemokine), and IL-13 mRNA (Th2 cytokines) (Figure 4C). IL-5 mRNA and IL-17 mRNA were also measured but these were below level of detection (data not shown). For the majority of these targets, their mRNA expression in the thymus increased with age, reaching a plateau between 1 and 5 years of age and declining thereafter (Figure 4). IDO mRNA expression, however, showed a steady decline with age although this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.07) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

The ontogeny of global expression of Th1/Th2 genes in the thymus. High (A), moderate (B), and low (C) baseline expression of Th1 and Th2 genes in the thymus obtained from children <6 months of age (black squares, n = 7), 6 to 12 months of age (black circles, n = 5), 1 to 5 years (black diamond, n = 7), and children >5 years of age (black triangle, n = 3). Targets were examined using real-time PCR and results are represented as means ± SEM. IL-5 mRNA and IL-17 mRNA were measured but values were below level of detection. *P < 0.05 versus <6-month-old age group.

Correlations between IDO Expression and Cytokine Patterns in Human Thymus

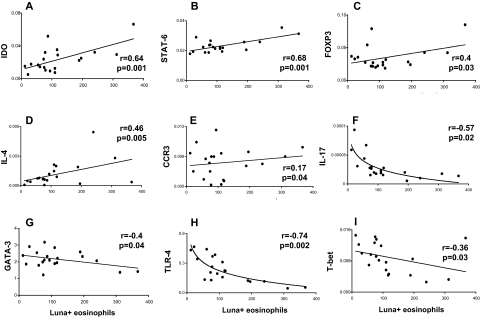

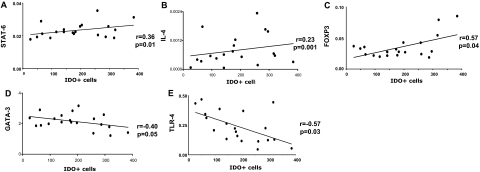

To examine the relationship between Th1/Th2-related genes and i) the number of eosinophils (determined by Luna positivity) (Figure 5) or ii) the number of IDO-positive cells (Figure 6) we determined the correlation co-efficient for each of the pair-wise comparisons. Our results showed strong positive correlation between the number of Luna+ eosinophils and total IDO mRNA (Figure 5A, r = 0.64, P = 0.001), STAT-6 mRNA (Figure 5B, r = 0.68, P = 0.001), FOXP3 mRNA (Figure 5C, r = 0.40, P = 0.03), IL-4 mRNA (Figure 5D, r = 0.46, P = 0.005), and CCR3 mRNA (Figure 5E, r = 0.17, P = 0.04) in the thymus. Negative correlations were detected between the number of Luna+ eosinophils and total IL-17 mRNA (Figure 5F, r = −0.57, P = 0.02), GATA-3 mRNA (Figure 5G, r = −0.40, P = 0.04), TLR4 mRNA (Figure 5H, r = −0.74, P = 0.002), and T-bet mRNA (Figure 5I, r = −0.36, P = 0.03) (Figure 5). The number of IDO-positive cells were positively correlated with STAT-6 mRNA (Figure 6A, r = 0.36, P = 0.01), IL-4 mRNA Figure 6 (B, r = 0.23, P = 0.001), and FOXP3 mRNA (Figure 6C, r = 0.57, P = 0.04), but negatively correlated with total GATA-3 mRNA (Figure 6D, r = −0.40, P = 0.05) and TLR4 mRNA (Figure 6E, r = −0.57, P = 0.03).

Figure 5.

Correlations between Luna-positive eosinophils and Th1/Th2 markers. Correlation between individual subjects’ Luna-positive eosinophil count and IDO (A), STAT-6 (B), FOXP3 (C), IL-4 (D), CCR3 (E), IL-17 (F), GATA-3 (G), TLR-4 (H), or T-bet (I) mRNA gene expression. R values are the correlation coefficients between the two variables. All correlations are linear except for IL-17 (F) and TLR-4 (H).

Figure 6.

Correlations between IDO-positive cells and Th1/Th2 markers. Correlation between individual subjects’ IDO-positive cells and STAT-6 (A), IL-4 (B), FOXP3 (C), GATA-3 (D), and TLR-4 (E) mRNA expression. R values are the correlation coefficients between the two variables.

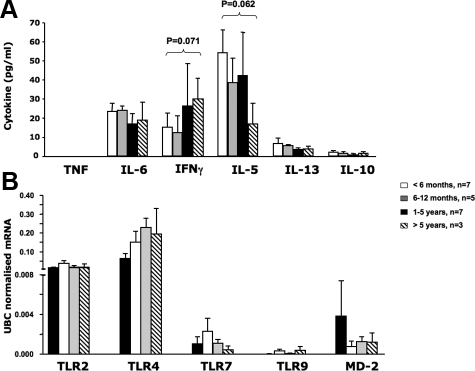

Basal Cytokine Protein Expression in the Human Thymus

Using the supernatant from thymus homogenates we measured constitutive (or basal) pro-inflammatory (tumor necrosis factor, IL-6), Th1 (IFN-γ), Th2 (IL-5, IL-13) and immunoregulatory (IL-10) cytokine levels in the four age groups (Figure 7A). There was no statistical differences in the amount of cytokine detected between the different age groups, however, IL-5 was the most abundant cytokine measured. There was a trend toward decreased IL-5 (P = 0.062) and increased IFNγ protein (P = 0.071) in children >5 years of age compared with those <6 months old (Figure 7A). We found a positive and significant correlation between the number of IDO+ cells and total IL-5 (r = 0.56, P = 0.002) or IL-13 (r = 0.44, P = 0.002) protein in the supernatant. Tumor necrosis factor was measured and was below level of detection for all age groups tested.

Figure 7.

Baseline cytokine and innate gene expression in the human thymus. A: Baseline cytokine protein production in the supernatants from homogenized thymic tissue and B: mRNA expression of innate (TLR) genes in unstimulated cells from neonates <6 months old (white bars, n = 7), infants between 6 and 12 months of age (gray bars, n = 5), 1- to 5-year-old children (black bars, n = 7), and children older than 5 years (striped bars, n = 3). Results are represented as means ± SE. In (B), RNA results are normalized to the reference housekeeping gene for ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2D2 and represented as means ± SE. There was no significant differences in constitutive (or basal) cytokine levels or expression of innate TLRs in the thymus between age groups although a trend for increased IFNγ (P = 0.071) and decreased IL-5 (P = 0.062) protein is seen in children >5 years of age compared with <6-month-old infants.

Expression of Innate TLRs in Human Thymus

Using a real-time PCR we detected basal expression of TLR-2, TLR-4, TLR-7, TLR-9, and MD-2 mRNA in thymi obtained from all age groups tested. No significant difference was detected between the 4 age groups although TLR-2 and TLR-4 mRNA expression appeared to be the most abundant when compared with other innate immunity markers (Figure 7B).

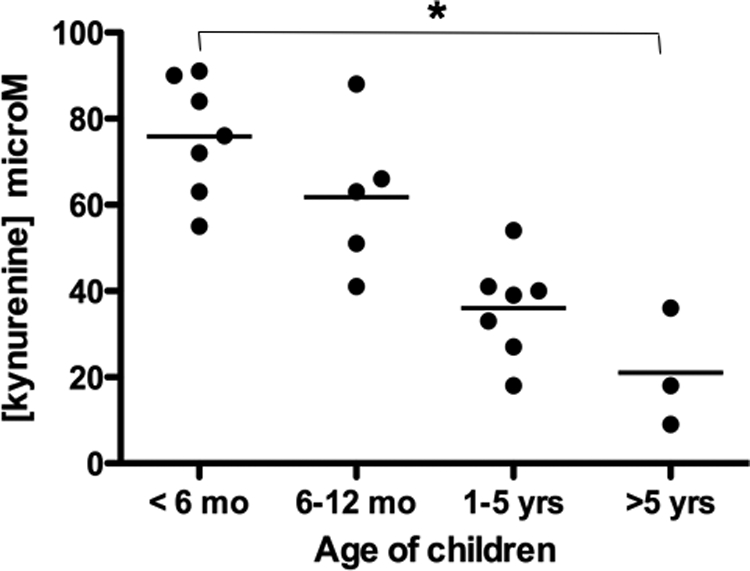

Immunodetection of KYNs and Measurement of KYN Activity in Thymus Homogenates

In the same section where abundant IDO+ eosinophils were localized (4-week-old neonate), we also detected KYN+ cells by immunohistochemistry (Figure 1G). KYNs were detected intracellularly and around the positive cells. Morphologically, KYN+ cells resembled eosinophils. Strong KYN immunoreactivity was also demonstrated in Hassall’s Corpuscles (Figure 1H). The concentration of KYN in the thymus homogenates significantly decreased with age (P = 0.01) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Age-dependent decrease in l-kynurenine activity in the human thymus. Age-dependent decrease in l-kynurenine concentration in the supernatants from thymus of neonates <6 months of age (n = 7), infants between 6 and 12 months of age (n = 5), 1- to 5-year-old children (n = 7), and children older than 5 years of age (n = 3). The bar represents group means. *P = 0.01 between <6-month and >5-year age groups. Concentration is given in μM/L.

Discussion

Although asthma and allergic disease are associated with the preponderance of allergen-reactive Th2 cells and their associated cytokines, the basis for this relative Th1/Th2 imbalance is not yet understood. Additionally, the relationship between eosinophils and T cells within a Th2 milieu remain to be fully clarified. The controversy around the precise role of the eosinophil in asthma and Th2-biased allergic inflammatory responses continues. However, new evidence from various laboratories suggests that this cell phenotype may have a wide range of biological, pathophysiological, structural, and immunological functions spanning the immune and inflammatory spectrum.22

Eosinophils are considered as terminal effectors of allergic responses in asthma and other inflammatory conditions, including inflammatory responses in favor of the host against parasitic helminth infections.23 These cells also have the capacity to interact with T cells, present antigen, and promote Th2 polarization,7,24 and thereby modulating adaptive immune responses. Although the presence of eosinophils in the human thymus has previously been described,8,25,26,27,28 their ontogeny and immunomodulatory role in the thymic microenvironment is unclear. This study describes for the first time, the ontogeny of eosinophils in the human thymus (from birth to adolescence), their expression of an immunomodulatory enzyme IDO and its catabolite KYN, and the correlation of IDO-positive eosinophils with a number of Th2 markers. These findings may play a pivotal role in T cell development in the thymus and early initiation of allergic Th2 responses.

In this study we have shown an age-dependent decrease in the number of eosinophils, with the most frequent expression seen in the youngest group of children (<6 months). In this age group, eosinophils were found within intralobular septa and at the cortico-medullary junction and made up approximately 2% of the total thymocytes. These Luna-positive, granular cells were not uniform in size. This was in contrast to the low numbers of eosinophils found in the older children (>5 years of age) whose eosinophils were less dense, regular in size, and found scattered throughout the thymus. Although thymus is considered not to be a hematopoietic organ,29 Lee and colleagues have shown eosinophil precursors (promyelocyte, myelocytes, and metamyelocytes) to be readily identified within the thymus (particularly in younger children) and to make up 30% to 50% of total eosinophilic population.8 These precursors were particularly frequent in children less than 5 years of age. Although tempting to speculate that the abundance of nonuniform eosinophilia detected in the thymus of our youngest cohort may suggest these to be the immature, eosinophil precursors, further studies are needed to confirm these findings. It is noteworthy that in murine thymus, eosinophils appeared to be recruited since their presence was dependent on the expression and biological activity of eotaxin, a potent chemoattractant of eosinophils both in vitro and in vivo.30 Fulkerson and colleagues31 have demonstrated complete absence of eosinophilia in eotaxin knockout mice and our data showing a positive correlation between CCR3 mRNA expression and eosinophils in the thymus support the role for eotaxin in recruiting eosinophils to the thymus.

The second aim of this study was to determine whether human thymic eosinophils express IDO. This is the first report of IDO expression in human thymus. Using immunofluorescence, we have additionally provided the first evidence that IDO enzyme is present in thymic eosinophils (visualized as yellow co-localization staining, Figure 3E) and that IDO is functionally active (as demonstrated by the presence of intracellular KYN staining). Human peripheral eosinophils express IDO constitutively, without IFNγ priming10 and they are positively associated with the IL-5 protein in the supernatants. IDO-dependent tryptophan catabolites including 3-hydroxyanthranilic and quinolinic acids are known to induce selective apoptosis of Th1 but not Th2 cells in the mouse.32 Our data suggest that thymic eosinophils may be key cells to contribute to this apoptotic process and to the Th2 milieu within the human thymic microenvironment. Our current data also support the hypothesis that early Th2 bias within the thymus illustrated by high constitutive mRNA expression of Th2 transcription factors (GATA-3 and STAT-6), Th2 cytokine IL-4, as well as immunoregulatory IL-10 and IDO itself (Figure 4). All of these targets correlated with IDO-positive eosinophils. Furthermore, constitutive IL-5 protein levels (Figure 7A) and KYN concentrations (Figure 8) in the thymus homogenates were greatest in the youngest children. This early Th2 bias (characterized by high expression of IL-5 mRNA) has been described in the thymic perivascular space of infants less than 2 years of age whereas IL-5 mRNA was undetectable in thymus derived from patients 3 years or older.28

IDO is not exclusively confined to eosinophils. Dendritic cells are the other important source of IDO33; these cells express both constitutive and IFNγ-inducible forms of the enzyme.34,35 Macrophages and monocytes can also express IDO but only following IFNγ stimulation.10 While not claiming exclusivity, our data demonstrate that functionally active IDO is constitutively expressed in thymic eosinophils during early life when immune responses are generally characterized by low IFNγ milieu.36

Another notable finding in this study was that in the neonates, Hassall’s corpuscles not only contain eosinophils (Figure 1, D and E) but show strong KYN immunoreactivity (Figure 1H). The physiological function of Hassall’s Corpuscles in vivo is unclear (particularly since murine thymus lacks this anatomical structure). However, in vitro evidence has shown that epithelial cells within Hassall’s corpuscles are a potent source of thymic stromal lymphopoietin, which instructs thymic dendritic cells to convert high-affinity, self-reactive T cells into CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells.37 Sharma and colleagues have recently demonstrated that IDO functions as a molecular switch in tumor-draining lymph nodes38; in its active state IDO maintains Tregs in their normal suppressive phenotype but when IDO is blocked it induces conversion of Foxp3+ Tregs to TH17-like cells. The exact mechanism by which this instruction occurs, in vivo, is poorly understood. As murine systemic Th2 inflammatory responses to thymic stromal lymphopoietin are eosinophil-dependent,39 our data suggest a worthwhile link to study the role of IDO+ eosinophils, KYN catabolites, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin in function of Hassall’s Corpuscles.

To gain a better understanding of the microenvironment milieu in the immediate vicinity of IDO+ eosinophils, we have measured KYN levels in thymus tissue homogenates. Measurement of KYN in any given site indicates IDO activity. We demonstrated age-dependent reduction in KYN concentration in the thymus (Figure 8). The abundance of active IDO-expressing eosinophils and, therefore, KYN catabolites in neonatal thymus may be a basis for the early Th2 polarization of the immature immune system. Moreover, by the very nature of KYN′s direct effect on Th1, but not Th2 cells, these results alone would support our contention of a possible early Th2-driven microenvironment in the thymus and maturation of local immunity from Th2 toward Th1 responses. This is supported by our PCR data showing a temporal increase in IFNγ mRNA (Figure 4C, P < 0.05) and a trend toward increased IFNγ protein (Figure 7A, P = 0.071) and innate TLR4 gene (Figure 7B) expression from birth to age 5.

In summary, our findings suggest an immunomodulatory role for eosinophils under non-pathological conditions and may have important implications for immune development. Our study indicates that IDO-positive eosinophils are detected in human thymus in early postnatal life and are associated with Th2 markers. In addition, this early period is associated with an abundant expression of KYN-immunoreactive cells and high concentration of KYNs in the thymus. Although, we did not perform co-localization studies, KYN+ cells morphologically resembled eosinophils. Eosinophils may, therefore, play an important role in controlling the ensuing immune responses and this response can be either stimulatory or suppressive depending on IDO inducibility. IDO is induced by infections, viruses, lipopolysaccharides, or interferons resulting in significant catabolism of tryptophan, an indispensable amino acid in protein biosynthesis. While biolevels of tryptophan are important for cell survival, it is likely that KYNs are the main culprits influencing T-cell fate in a milieu of tryptophan catabolism via IDO.

Thus, induction of IDO and oxidative catabolism of tryptophan may promote a Th2 biased setting (eg, allergy and asthma) through selective apoptosis of Th1 cells. Conversely, IDO/tryptophan may foster a Th1 condition (eg, autoimmune disease including diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis) through suppression of adaptive T cell-mediated immunity associated with inflammation and host immune defense.

Acknowledgments

We thank all parents and children who participated in this study. The authors would also like to thank Dr Brad Guicheng Zhang for expert statistical advice.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Redwan Moqbel, Ph.D., FRCPath, Professor and Head, Department of Immunology, Room 471 Apotex Centre, 750 McDermot Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3E 0T5. E-mail: moqbelr@cc.umanitoba.ca.

Supported by the following peer-reviewed granting agencies in Canada and Australia: The Canadian Institutes of Health Research, AllerGen Network of Canadian Centres of Excellence, Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, Canada, The National Health, and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC), including a Peter Doherty Fellowship to M.K.T.

This study was conducted during a sabbatical leave for RM who was an Alberta Heritage Medical Scientist at the University of Alberta.

P.D.S. and P.G.H. are senior Principal Research Fellows of the NHMRC.

References

- Holt PG, Jones CA. The development of the immune system during pregnancy and early life. Allergy. 2000;55:688–697. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott SL, Macaubas C, Holt BJ, Smallacombe TB, Loh R, Sly PD, Holt PG. Transplacental priming of the human immune system to environmental allergens: universal skewing of initial T cell responses toward the Th2 cytokine profile. J Immunol. 1998;160:4730–4737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota MO, Vekemans J, Schlegel-Haueter SE, Fielding K, Whittle H, Lambert PH, McAdam KP, Siegrist CA, Marchant A. Hepatitis B immunisation induces higher antibody and memory Th2 responses in newborns than in adults. Vaccine. 2004;22:511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladi E, Yin X, Chtanova T, Robey EA. Thymic microenvironments for T cell differentiation and selection (Review). Nat Immunol. 2006;7:338–343. doi: 10.1038/ni1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Sofi MH, Yeh N, Sehra S, McCarthy BP, Patel DR, Brutkiewicz RR, Kaplan MH, Chang CH. Thymic selection pathway regulates the effector function of CD4 T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2145–2157. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen EA, Taranova AG, Lee NA, Lee JJ. Eosinophils: singularly desrtuctive effector cells or purveyors of immunoregulation? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1313–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo V, De Andrés B, Martín E, Cárdaba B, Fernández JC, Gallardo S, Tramón P, Leyva-Cobian F, Palomino P, Lahoz C. Eosinophil as antigen-presenting cell: activation of T cell clones and T cell hybridoma by eosinophils after antigen processing. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1919–1925. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Yu E, Good RA, Ikehara S. Presence of eosinophilic precursors in the human thymus: evidence for intra-thymic differentiation of cells in eosinophilic lineage. Pathol Int. 1995;45:655–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1995.tb03518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Throsby M, Herbelin A, Pleau JM, Dardenne M. CD11c+ eosinophils in the murine thymus: developmental regulation and recruitment upon MHC class I-restricted thymocyte deletion. J Immunol. 2000;165:1965–1975. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odemuyiwa SO, Ghahary A, Li Y, Puttagunta L, Lee JE, Musat-Marcu S, Ghahary A, Moqbel R. Cutting edge: human eosinophils regulate T cell subset selection through indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Immunol. 2004;173:5909–5913. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.5909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belladonna ML, Puccetti P, Orabona C, Fallarino F, Vacca C, Volpi C, Gizzi S, Pallotta MT, Fioretti MC, Grohmann U. Immunosuppression via tryptophan catabolism: the role of kynurenine pathway enzymes. Transplantation. 2007;84:S17–S20. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000269199.16209.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallarino F, Grohmann U, Vacca C, Orabona C, Spreca A, Fioretti MC, Puccetti P. T cell apoptosis by kynurenines. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;527:183–190. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0135-0_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odemuyiwa SO, Ebeling C, Duta V, Abel M, Puttagunta L, Cravetchi O, Majaesic C, Vliagoftis H, Moqbel R. Tryptophan catabolites regulate mucosal sensitization to ovalbumin in respiratory airways. Allergy. 2009;64:488–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ, Dimina D, Macias MP, Ochkur SI, McGarry MP, O'Neill KR, Protheroe C, Pero R, Nguyen T, Cormier SA, Lenkiewicz E, Colbert D, Rinaldi L, Ackerman SJ, Irvin CG, Lee NA. Defining a link with asthma in mice congenitally deficient in eosinophils. Science. 2004;305:1773–1776. doi: 10.1126/science.1099472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen EA, Ochkur SI, Pero RS, Taranova AG, Protheroe CA, Colbert DC, Lee NA, Lee JJ. Allergic pulmonary inflammation in mice is dependent on eosinophil-induced recruitment of effector T cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:699–710. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulic MK, Hurrelbrink RJ, Prele CM, Laing IA, Upham JW, Le Souef P, Sly PD, Holt PG. TLR4 polymorphisms mediate impaired responses to respiratory syncytial virus and lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2007;179:132–140. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna L. Manual of Histologic Staining Methods of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1968:114–115. [Google Scholar]

- Tulic MK, Fiset PO, Manoukian JJ, Frenkiel S, Lavigne F, Eidelman DH, Hamid Q. Role of toll-like receptor 4 in protection by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in the nasal mucosa of atopic children but not adults. Lancet. 2004;363:1689–1697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moqbel R, Barkans J, Bradley BL, Durham SR, Kay AB. Application of monoclonal antibodies against major basic protein (BMK-13) and eosinophil cationic protein (EG1 and EG2) for quantifying eosinophils in bronchial biopsies from atopic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 1992;22:265–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1992.tb03082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamalainen HK, Tubman JC, Vikman S, Kyrola T, Ylikoski E, Warrington JA, Lahesmaa R. Identification and validation of endogenous reference genes for expression profiling of T helper cell differentiation by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Analyt Biochem. 2001;299:63–70. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takikawa O, Kuroiwa T, Yamazaki F. Mechanism of interferon-γ action: characterization of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in cultured human cells by interferon-g and evaluation of the enzyme mediated tryptophan degradation in its anticellular activity. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:2041–2048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamko DJ, Odemuyiwa SO, Vethanayagam D, Moqbel R. The rise of the phoenix: the expanding role of the eosinophil in health and disease. Allergy. 2005;60:13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan SP, Rosenberg HF, Moqbel R, Phipps S, Foster PS, Lacy P, Kay AB, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophils: biological properties and role in health and disease. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:709–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.02958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura N, Ishii N, Nakazawa M, Nagoya M, Yoshinari M, Amano T, Nakazima H, Minami M. Requirement of CD80 and CD86 molecules for antigen presentation by eosinophils. Scand J Immunol. 1996;44:229–238. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1996.d01-303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller E. Localization of eosinophils in the thymus by the peroxidase reaction. Histochemistry. 1977;52:273–279. doi: 10.1007/BF00495862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dourov N. Microscopy of the thymus in the perinatal period. (French). Ann Pathol. 1982;2:255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Kephart GM, Talley NJ, Wagner JM, Sarr MG, Bonno M, McGovern TW, Gleich GJ. Eosinophil infiltration and degranulation in normal human tissue. Anat Rec. 1998;252:418–425. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199811)252:3<418::AID-AR10>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores KG, Li J, Sempowski GD, Haynes BF, Hale LP. Analysis of the human thymic perivascular space during aging. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1031–1039. doi: 10.1172/JCI7558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg ME. Eotaxin. An essential mediator of eosinophil trafficking into mucosal tissues. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21:291–295. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.3.f160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AN, Friend DS, Zimmermann N, Sarafi MN, Luster AD, Pearlman E, Wert SE, Rothenberg ME. Eotaxin is required for the baseline level of tissue eosinophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:6273–6278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson PC, Fischetti CA, McBride ML, Hassman LM, Hogan SP, Rothenberg ME. A central regulatory role for eosinophils and the eotaxin/CCR3 axis in chronic experimental allergic airway inflammation. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2006;103:16418–16423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607863103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallarino F, Grohmann U, Vacca C, Bianchi R, Orabona C, Spreca A, Fioretti MC, Puccetti P. T cell apoptosis by tryptophan catabolism. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:1069–1077. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor AL, Baban B, Chandler P, Marshall B, Jhaver K, Hansen A, Koni PA, Iwashima M, Munn DH. Cutting edge: induced indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase expression in dendritic cell subsets suppresses T cell clonal expansion. J Immunol. 2003;171:1652–1655. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallarino F, Vacca C, Orabona C, Belladonna ML, Bianchi R, Marshall B, Keskin DB, Mellor AL, Fioretti MC, Grohmann U, Puccetti P. Functional expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by murine CD8 alpha(+) dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2002;14:65–68. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwu P, Du MX, Lapointe R, Do M, Taylor MW, Young HA. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase production by human dendritic cells results in the inhibition of T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2000;164:3596–3599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott SL, Macaubas C, Smallacombe T, Holt BJ, Sly PD, Holt PG. Development of allergen-specific T-cell memory in atopic and normal children. Lancet. 1999;353:196–200. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N, Wang YH, Lee HK, Ito T, Wang YH, Cao W, Liu YJ. Hassall’s corpuscles instruct dendritic cells to induce CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in human thymus. Nature. 2005;436:1181–1185. doi: 10.1038/nature03886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma MD, Hou DY, Liu Y, Koni PA, Metz R, Chandler P, Mellor AL, He Y, Munn DH. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase controls conversion of Foxp3+ Tregs to TH17-like cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes. Blood. 2009;113:6102–6111. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessup HK, Brewer AW, Omori M, Rickel EA, Budelsky AL, Yoon BR, Ziegler SF, Comeau MR. Intradermal administration of thymic stromal lymphopoietin induces a T cell- and eosinophil-dependent systemic Th2 inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2008;181:4311–4319. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]