Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is pathologically characterized by accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ) protein deposits and/or neurofibrillary tangles in association with progressive cognitive deficits. Although numerous studies have demonstrated a relationship between brain pathology and AD progression, the Alzheimer’s pathological hallmarks have not been found in the AD retina. A recent report showed Aβ plaques in the retinas of APPswe/PS1ΔE9 transgenic mice. We now report the detection of Aβ plaques with increased retinal microvascular deposition of Aβ and neuroinflammation in Tg2576 mouse retinas. The majority of Aβ-immunoreactive plaques were detected from the ganglion cell layer to the inner plexiform layer, and some plaques were observed in the outer nuclear layer, photoreceptor outer segment, and optic nerve. Hyperphosphorylated tau was labeled in the corresponding areas of the Aβ plaques in adjacent sections. Although Aβ vaccinations reduced retinal Aβ deposits, there was a marked increase in retinal microvascular Aβ deposition as well as local neuroinflammation manifested by microglial infiltration and astrogliosis linked with disruption of the retinal organization. These results provide evidence to support further investigation of the use of retinal imaging to diagnose AD and to monitor disease activity.

Cerebral abnormalities including neuronal loss, neurofibrillary tangles, senile plaques with aggregated β-amyloid protein (Aβ) deposits, microvascular deposition of Aβ, and inflammation are well-known pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).1,2,3 Despite the controversial evidence about the contribution of Aβ to the development of AD-related cognitive deficits, accumulation of toxic, aggregated forms of Aβ plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of familial types of AD.4,5 Overexpression of amyloid precursor protein (APP) in trisomy 21, altered APP processing resulting from mutations in APP, presenilin 1 (PS1), or 2 (PS2), and, as-of-yet unidentified other familial AD, related mutations, lead to Aβ deposition and Aβ plaques in the brain as well as cognitive abnormalities.6,7 Therefore, to understand the molecular basis of amyloid protein deposition and to detect Aβ plaques in brain, parenchyma ante-mortem are currently among the most active areas of research in AD.

Besides cognitive abnormalities, patients with AD commonly complain of visual anomalies, in particular, related to color vision,8,9 spatial contrast sensitivity,10 backward masking,11 visual fields,12 and other visual performance tasks.13,14,15,16 In addition to the damage and malfunction in the central visual pathways, retinal abnormalities such as ganglion cell degeneration,17 decreased thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer,18,19 and optic nerve degeneration20,21 may, in part, account for AD-related visual dysfunction. Although intracellular Aβ deposition has been detected in both ganglion and lens fiber cells of patients with glaucoma, AD, or Down’s syndrome,22,23,24,25 other typical hallmarks of AD have not yet been demonstrated. Interestingly, thioflavine-S-positive Aβ plaques were recently found in the retinal strata of APPswe/PS1ΔE9 transgenic mice26 but not in the other animal models of AD. The current study used Tg2576 mice that constitutively overexpress APPswe and develop robust Aβ deposits in brain as well as cognitive abnormalities with aging.27 We assessed the pathological changes in the retina of aged mice following different immunization schemes. We immunized Tg2576 with fibrillar Aβ42 and with a prefibrillar oligomer mimetic that gives rise to a prefibrillar oligomer-specific immune response. Both types of immunogens have been shown to be equally effective in reducing plaque deposition and inflammation in Tg2576 mouse brains.28 In this study, we also used another prefibrillar oligomer mimetic antigen that uses the islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) instead of Aβ, but which gives rise to the same generic prefibrillar oligomer-specific immune response that also recognizes Aβ prefibrillar oligomers.29 Aβ plaques and microvascular Aβ deposition were observed in the control Tg2576 mouse retinas. In contrast, Aβ and IAPP prefibrillar oligomer vaccinations differentially removed retinal Aβ deposits but exacerbated retinal amyloid angiopathy and inflammation as demonstrated by a significantly enhanced microglial infiltration and astrogliosis.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Peptides

The Aβ oligomer antigen was prepared from Aβ1-40 based on our previously published work.30 Briefly, lyophilized Aβ1-40 peptides were resuspended in 50% acetonitrile in water and relyophilized. Soluble prefibrillar oligomers were prepared by dissolving 1.0 mg of peptide in 400 μl of hexafluoroisopropanol for 10∼20 minutes at room temperature. The resultant seedless solution (100 μl) was added to 900 μl of MilliQ H2O in a siliconized Eppendorf tube. After 10∼20 minutes incubation at room temperature, the samples were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 14,000 × g, and the supernatant fraction (pH 2.8∼3.5) was transferred to a new siliconized tube and subjected to a gentle stream of N2 for 5∼10 minutes to evaporate the hexafluoroisopropanol. The samples were then stirred at 500 rpm using a Teflon-coated micro stir bar for 24–48 hours at 22°C. Oligomers were validated by atomic force microscopy, electron microscopy, and size exclusion chromatography as described previously.30 The Aβ fibril was prepared from Aβ1-42, because it is more fibrillogenic as compared with Aβ1-40. Aβ1-40, predominantly in fibrillary form, was previously studied in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2a clinical trial, study AN1792(QS-21)-201 by Gilman and colleagues.31 Fibrils were formed by dissolving the lyophilized Aβ1-42 in 50% hexafluoroisopropanol and stirred with closed caps for 7 days. Solution is stirred again for 2 days in capped tubes with 20-gauge needle holes on the top to allow the hexafluoroisopropanol to evaporate. This whole preparation was done in a fume food to accelerate evaporation and minimize falling of dust or other foreign material. Fibrils were precipitated by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 14,000 rpm and washed in PBS, and resuspended at 2 mg/ml. For the prefibrillar oligomer antigen, Aβ oligomer (AO) molecular mimic was prepared by conjugating Aβ1-40 via a C-terminal thioester to 5-nm colloidal gold as described previously.32 The same procedure was used for prefibrillar IAPP oligomers, and products were stored at 4°C until used.

Animals and Immunization Schemes

Both Tg2576 mice derived from the Tg(HuAPP695.K670N-M671L)2576 line, a widely used strain created by K. Hsiao27 that exhibits robust cerebral extracellular Aβ deposits and cognitive deficits in aged animals, and nontransgenic littermates were used for experiments and controls, respectively. Immunization schemes were conducted in a similar way as described previously.28 Briefly, 4-month-old mice were immunized s.c. with a preparation containing 100 μg of AO, IAPP, or Aβ fibrils (AF) and combined with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (1:1 v/v) once a month for 10 months. Administration of an equivalent volume of PBS with the adjuvant but without any peptide antigen to both wild-type and transgenic mice was used as control. All experimental procedures were performed under protocols approved by the University of California Irvine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tissue Preparation

Mice were deeply anesthetized with an overdose of Nembutal (100 mg/kg, i.p.) and perfused transcardially with ice-cold PBS. The eyes were directly collected and fixed overnight with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4, 4°C) following brain removal. Fixed eyes were stored in PBS containing 20% sucrose and 0.05% sodium azide (NaN3) at 4°C until use. Following removal of lenses with forceps fixed eyes were cryomolded with OCT. Cross-retinal cryostat sections (12 μm) were thaw-mounted onto “Superfrost plus” glass slides (Fisher, Tustin, CA), air-dried for 30 minutes and stored at 4°C before staining. Brain tissue was fixed in the same way as eyes and was stored in PBS with 0.05% NaN3. Coronal sections (40 μm) through the dorsal hippocampus were prepared using a Vibratome and were collected in PBS for immunohistochemistry.

Antibodies and Chemicals

The information for all of the antibodies used in this study is summarized in Table 128,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. The avidin-biotin complex kit for diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining and VectaShield fluorescent mounting medium containing 4′,6′-diamidino- 2-phenylindole were purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Unless indicated, all of the chemical reagents used in the experiments were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Table 1.

List of Antibodies Used in the Study

| Antibody and related antigen | Type | Source | Dilution | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPA1-01132 for human APP | Rabbit polyclonal | Affinity Bioreagents (Golden, CO) | 1/100 | 33 |

| BAM01 (6F/3D) for Aβ; cross-reacts with APP | Mouse monoclonal | Neomarkers (Fremont, CA) | 1/100 (retina) | 34, 35 |

| 1/500 (brain) | ||||

| 6E10 for Aβ; cross-reacts with APP | Mouse monoclonal | Covance (Denver, PA) | 1/100 | 28, 36 |

| 12F4 for Aβ42 | Mouse monoclonal | Covance | 1/500 | 37 |

| 5C3 for Aβ40 | Mouse monoclonal | Assay Designs (Ann Arbor, MI) | 1/500 | 34, 35 |

| GA5 for GFAP, a marker for astrocytes or Müller cells | Rabbit polyclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | 1/500 | 38, 39 |

| CP290A for IBA1, a marker for microglia | Rabbit polyclonal | Biocare (Concord, CA) | 1/100 | 40 |

| AT8 for hyperphosphorylated tau | Mouse monoclonal | Pierce (Rockford, IL) | 1/100 | 41 |

| vWF | Rabbit polyclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | 1/100 | 42 |

| Biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG | Goat polyclonal | Vector Laboratories | 1/200 | 43 |

| Biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG | Goat polyclonal | Vector Laboratories | 1/200 | 43 |

| Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG | Goat polyclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | 1/100 | 43 |

| FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG | Goat polyclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | 1/100 | 43 |

| Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG | Donkey polyclonal | Chemicon (Bellerica, MA) | 1/100 | 43 |

Immunohistochemistry and Quantification

For immunohistochemistry, cross-retinal sections were rehydrated, incubated with 70% formic acid for 5 minutes at room temperature for antigen retrieval, rinsed with PBS, soaked in 3% H2O2 for 20 minutes at room temperature to abolish the endogenous peroxidase activity for DAB staining, and/or directly blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 20 mmol/L l-lysine for 30 minutes at room temperature before incubating with specific primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The immunoreactivity of Aβ, von Willebrand factor (vWF), which labels vascular endothelial cells, and IBA1 or glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), which label microglia or astrocytes, respectively, was visualized with immunofluorescence microscopy following staining with Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse or FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and covered with VectaShield 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole-containing mounting medium. The immunoreactivity of APP, hyperphosphorylated tau (AT8), and Aβ in selected sections was also detected using the avidin-biotin complex method, followed by staining with DAB and brief counterstaining with hematoxylin. The histological sublayers of retinal cross-sections were identified based on nuclear counterstaining and/or the presence of sclera or pigment epithelium-choroid layer. Brain sections were immunostained free floating following the same procedure as with retinal immunohistochemistry.

The results were evaluated by either fluorescence or conventional microscopy with a Leica DM microscope. Images were recorded using a Spot II charge-coupled device camera with equal exposure times for all different groups of tissues. For quantification, the number of Aβ plaques, both Aβ and vWF double-stained capillaries or other vessels, or IBA1-positive cells were counted in each section at a magnification of ×400. Two nonadjacent immunostained sections were examined for each animal. The number of Aβ and vWF double-stained microvessels in a given section was used as a score of amyloid angiopathy.

Congo Red Staining

Congo red staining was performed using a Sigma Congo red kit for amyloid staining according to the manufacturer’s protocol with minor modification. Briefly, sections were stained in Mayer’s hematoxylin solution for ∼10 seconds, rinsed in tap water, incubated with alkaline sodium chloride for 20 minutes, stained in alkaline Congo red solution for ∼30 minutes, followed by washing in absolute ethanol and mounting. Congo red fluorescence staining was visualized with fluorescence microscopy.

Measurements of the Retinal Thickness

On both sides of each cross-retinal section two images were taken at 200 and 800 μm from the optic nerve at a magnification of ×200. The distance from the surface of the ganglion cell layer to the outside border of the outer nuclear layer was measured using the Adobe Photoshop 7.0 ruler tool. The mean of all four measurements represented the thickness of the retina. Data from three cross-retinal sections were obtained for each animal.

Data Analysis

In all of the graphs that include error bars, the data points represent the means ± SEM from all individuals in each group of animals (N = 7–9). Where applicable, multiple comparisons were performed by one-way analysis of variance, followed by Student’s t-test using Microsoft Excel software. The differences between groups were considered statistically significant when P values were <0.05.

Results

Accumulation of Aβ Deposits and Phosphorylated Tau in the Retinas of Tg2576 Mice

Numerous studies showed abundant expression of APPswe transgene in the nervous system and Aβ plaques in the brain of APPswe transgenic mice older than 12 months.44 As all of the animals used in this study were 14 months old, immunofluorescence microscopy following 6E10 antibody staining confirmed robust deposition of Aβ plaques in both cortical and hippocampal regions in the Tg2576 mouse brain, whereas an extremely low level of background staining was detected in the wild-type mouse brains (Figure 1, A and B). To assess expression of the transgene in the retina, the immunoreactivity of human APPswe protein was evaluated following APP-specific antibody staining. Consistent with a recently published observation,45 APP immunoreactivity was predominantly detected in the cytoplasm of cells in the ganglion cell layer as well as inner nuclear layer of Tg2576 mice (Figure 1D). By comparison, a much lower intensity of staining was observed in the corresponding regions of the retina from wild-type mice (Figure 1C). Interestingly, examination of Aβ immunoreactivity in cross-retinal sections from Tg2576 mice using the human Aβ-specific monoclonal antibody, BAM01 (6F/3D), revealed a remarkable accumulation of Aβ deposits within the retina. Importantly, most senile plaque-like staining patterns were detected from the ganglion cell layer to the outer nuclear layer (Figure 1, F and H). In rare cases, plaques were found in the photoreceptor outer segment layer and optic nerve as well (data not shown). To ensure that the plaque staining was not due to nonspecific deposition of DAB, adjacent sections were immunostained with another commonly used monoclonal antibody, 6E10, which demonstrated a staining pattern similar to that obtained with BAM01 (Figure 1, I and J). Importantly, although both BAM01 and 6E10 antibodies were raised from the N-terminal sequences of Aβ and may cross-react with APP and/or other APP C-terminal fragments on Western blots or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, they appear to stain predominantly Aβ in immunohistochemistry46,47 and showed distinct staining patterns from that of APP antibody (Figure 1D) using the staining protocol as described here. This was further confirmed by a mouse monoclonal antibody that is specific for Aβ40 (Figure 1K) or Aβ42 (Figure 1L) in corresponding regions of sections close to those shown in Figure 1, J and H. Moreover, some of the Aβ deposits were Congo red-positive (Figure 1, M and P). In contrast, wild-type retinas showed slightly stained background and no plaques (Figure 1, E and G). Quantification of plaques within the cross-retinal sections indicated about two to three visible plaques detected in the retinas from 85.7% of Tg2576 mice, but no plaques in the retinas of wild-type mice (Figure 1, Q and R). As previous studies demonstrated hyperphosphorylated tau in the Tg2576 mouse brain,48,49 we therefore examined whether hyperphosphorylated tau was associated with Aβ deposits in the Tg2576 retina. Adjacent sections were stained with the AT8 antibody, which specifically recognizes hyperphosphorylated tau.48,50 Remarkably, hyperphosphorylated tau immunoreactivity was detected in regions corresponding to those that were stained by 6E10 for Aβ (Figure 1, N and O).

Figure 1.

Accumulation of senile plaques in Tg2576 Alzheimer’s mouse retinas is altered by Aβ-based immunotherapy. Immunofluorescence microscopy following BAM01 antibody staining reveals no signal in the wild-type (A) and robust Aβ senile plaques in Tg2576 mouse brain (B). DAB staining following APP antibody labeling in cross-retinal sections shows endogenous background signal (light brown) and expression of transgene APPsw product (dark brown) in wild-type (C) and Tg2576 (D) mice, respectively. E–H: BAM01 for Aβ yields low background signal in the wild-type (E) and plaque-like Aβ deposits in Tg2576 (F, arrow) mouse retinas; a different field at higher magnification for the control (G) and Tg2576 (H, arrows indicate plaque-like Aβ deposits) mouse retinas. The adjacent section to F was stained with 6E10 antibody and visualized with immunofluorescence microscopy (I). The boxed area in I is shown in J at a higher magnification. Sections close to J were stained with a monoclonal antibody for Aβ40 (K) or for Aβ42 (L) or with Congo red (M). A section from a different Tg2576 mouse stained with Congo red demonstrates condensed Aβ plaques that are similar to those detected in AD brain and mouse retinas by others (P, arrow).26 N: The adjacent section to I was stained with AT8 for hyperphosphorylated tau and visualized by microscopy following DAB staining. The boxed area in N is shown in O at a higher magnification (arrow indicates plaque-like staining). Cell nuclei were counterstained purple by hematoxylin (C–H, N, and O) or blue by 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (K and L). The pigment epithelium-choroid layer (p) is dark brown or black in DAB-stained sections (E, F, and N) and provides red background fluorescence with sclera (s). Quantification of Aβ staining for the cross retinal sections from all of the animals shows percentage of Aβ-positive sections (Q) and number of Aβ plaques per section (R). WT, wild-type; Tg, transgenic; Ctl, Control (sham-vaccinated Tg2576); AF, Aβ fibrils. Bars depict mean ± SEM (n = 7–9), ∗P < 0.05. os, photoreceptor outer segments; onl, outer nuclear layer; opl, outer plexiform layer; inl, inner nuclear layer; ipl, inner plexiform layer; g, ganglion cell layer. Scale bar = 800 μm (A and B), 60 μm (C, D, G, H, J, K, L, M, O, and P), and 300 μm (E, F, I, and N).

Aβ-Related Vaccinations Reduce Aβ Deposits in the Retinas of Tg2576 Mice

To assess the effect of immunotherapy on retinal deposition of Aβ, immunohistochemistry was performed on retinal sections from Tg2576 mice after a 10-month regime of vaccinations. Two adjacent cross-retinal sections from each animal were stained with either BAM01 or 6E10 and analyzed along with sections from control mice. Figure 1, P and Q, shows that there was a decrease in plaque-containing retinas and the number of plaques per section that varied with the vaccination immunogen. Particularly, both AO- and IAPP-immunized animals demonstrated a significant reduction in the number of Aβ plaques compared with mice that received PBS adjuvant. The other groups exhibited less pronounced reductions in Αβ deposits that were not statistically significant.

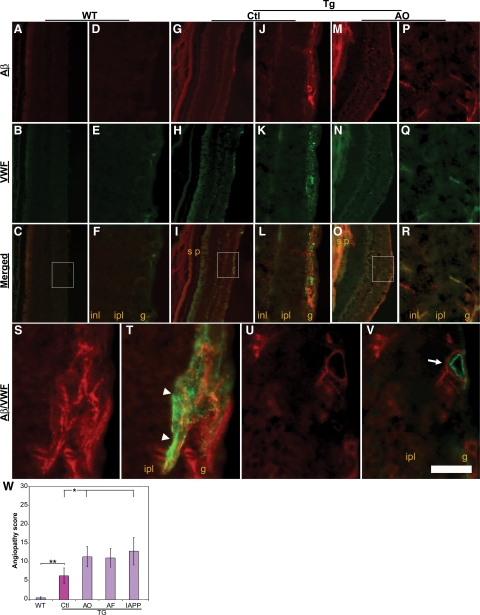

Aβ-Related Vaccinations Exacerbate Retinal Amyloid Angiopathy in Tg2576 Mice

In addition to the accumulation of Aβ plaques in the brain parenchyma, progressive deposition of Aβ peptide in the cerebral microvasculature, that is, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, is a well-known pathological feature of AD.51,52,53 To examine whether there was any microvascular deposition of Aβ in the retina, that is, retinal amyloid angiopathy, of AD transgenic mice, cross-retinal sections were dual-labeled with both BAM01 and a rabbit polyclonal IgG for vWF, an endothelial cell marker of microvessels. Both Aβ and vWF double-labeled microvessels were quantified and used as retinal amyloid angiopathy scores. Figure 2 shows representative photomicrographs from wild-type (Figure 2, A–F) and sham-immunized Tg2576 control mice (Figure 2, G–L) and mice immunized with AO (Figure 2, M–R). A similar staining pattern was seen in the mice immunized with either AF or IAPP oligomers as well (data not shown). Notably, although Aβ immunoreactivity was detected in vWF-labeled microvessels in sections from Tg2576 control mice, even greater Aβ immunoreactivity was present in retinal microvessels from AO-, AF-, or IAPP-immunized mice. Dual-labeled immunoreactivity of Aβ and vWF at a higher magnification demonstrated both intraendothelial (Figure 2, S and T) and perivascular (Figure 2, U and V) deposition of Aβ. In contrast, vWF-labeled microvessels in the wild-type mice exhibited no obvious Aβ immunoreactivity (Figure 2, A–F). Image analysis of sections from groups of animals demonstrated a significant increase in the retinal amyloid angiopathy score of Tg2576 mice compared with wild-type mice (P < 0.005), as well as in immunized compared with sham-immunized Tg2576 control mice (Figure 2W).

Figure 2.

Capillary deposition of Aβ in the retinas from Tg2576 mice following vaccinations. Immunoreactivity of Aβ (red) and capillary the endothelial cell marker vWF (green) was visualized in Tg2576 (Tg, G–R) and wild-type (WT, A–F) mice, with or without AO immunization, by immunofluorescence microscopy. Boxed areas in C, I, and O are shown in F, L, and R, respectively, at a higher magnification. Regions labeled s and p in G–I and M–O denote background fluorescence from sclera and pigment epithelium-choroid layer, respectively. S–V: A field in a cross-retinal section from an AO-immunized Tg2576 mouse shows that Aβ immunoreactivity (red in S and U) overlaps with vWF immunoreactivity within microvasculature (green in T, arrowheads) or surrounds vWF staining in the wall of a microvessel (green in V, arrow). inl, inner nuclear layer; ipl, inner plexiform layer; g, ganglion cell layer. W: Quantification of angiopathy scores for each group of animals. Bars depict mean ± SEM (n = 7–9); ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.005. WT, wild-type; Tg, transgenic; Ctl, Control (sham-vaccinated Tg2576); AF, Aβ fibrils. Scale bar = 300 μm (A–C, G–I, and M–O), 60 μm (D–F, J–L, and P–R), and 20 μm (S–V).

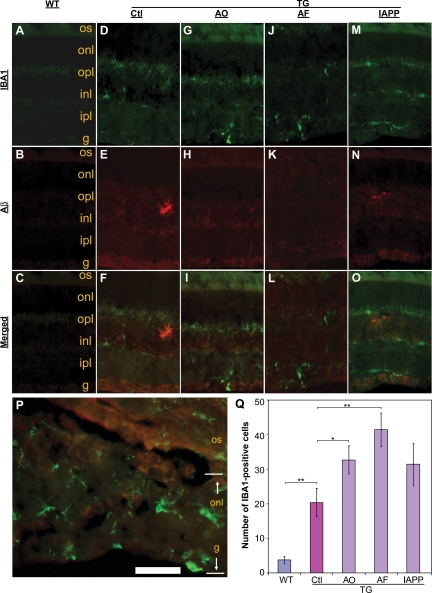

Aβ-Related Vaccinations Stimulate Microglial Infiltration and Astrogliosis in the Retinas of Tg2576 Mice

One of the main characteristics accompanying accumulation of Aβ plaques in both human Alzheimer’s brain and transgenic mouse models of AD is an enhanced neuroinflammatory response characterized by activation of astrocytes and infiltration of microglia. Therefore, we examined expression of GFAP and IBA1, cell type-specific markers of astrocytes and microglia, respectively, and performed quantitative image analysis to evaluate the degree of microglial infiltration in the immunized animals. Figure 3 demonstrates representative microphotographs of IBA1- and Aβ-immunoreactivity in the retinas of wild-type, immunized, and sham-immunized mice. Similar to the microvascular deposition of Aβ, there was a dramatic increase in IBA1-immunoreactivity in the retina of Tg2576 mice (Figure 3, D–O) compared with the wild-type mice (Figure 3, A–C). Importantly, in some cases, the microglial infiltration was closely associated with disrupted retinal architecture in immunized mice (Figure 3P), in which all of the different layers from the ganglion cell layer to the outer nuclear layer were damaged and barely distinguished. Quantification of IBA1-positive cells demonstrated a significant increase in microglia in the AD mouse retina (Figure 3Q). Importantly, each type of vaccination scheme increased microglial infiltration compared with PBS adjuvant-treated Tg2576 control mice.

Figure 3.

Microglial infiltration is associated with Aβ deposition in the retinas from Tg2576 mice following vaccinations. Immunofluorescence microscopy reveals IBA1 immunoreactivity as microglial marker (green) and Aβ deposition (red) in the retinas from different groups of wild-type (A–C) or Tg2576 mice (D–O) as indicated at the top of the figure. P: A field shows both IBA1 (green) and Aβ immunoreactivity in a cross-retinal section from an “AF”-immunized Tg2576 mouse at a higher magnification. Q: Quantification of IBA1-immunoreactive cells within a retina. Bars depict mean ± SEM (n = 7–9); ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.001. WT, wild-type; Tg, transgenic; Ctl, Control (sham-vaccinated Tg2576); AF, Aβ fibrils. os, photoreceptor outer segments; onl, outer nuclear layer; opl, outer plexiform layer; inl, inner nuclear layer; ipl, inner plexiform layer; g, ganglion cell layer. Scale bar = 160 μm (A–O) and 20 μm (P).

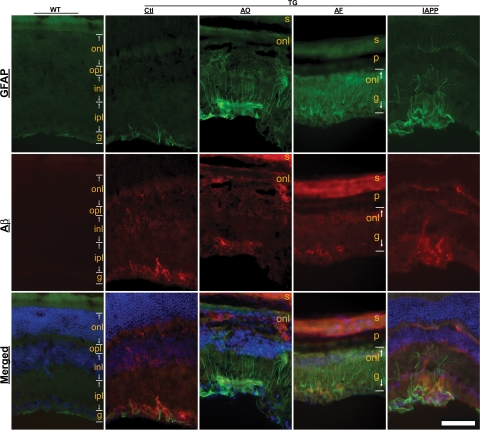

To further examine neuroinflammation in the Alzheimer’s retina, astrocytic/Müller cell activation was evaluated based on the immunoreactivity for GFAP. In wild-type mice GFAP immunoreactivity was predominantly limited to the topmost part of the retina or within the ganglion cell layer (Figure 4). In contrast, the retina of Tg2576 mice exhibited GFAP immunoreactivity not only in the superficial part and the ganglion cell layer as in controls but also in astrocytic processes that penetrated the ganglion cell layer to reach deeper layers. Notably, each of the vaccinations dramatically enhanced this type of staining pattern for GFAP-labeled Müller cell processes (Figure 4). This observation is consistent with the quantitative changes in microglial infiltration following vaccination and supports the notion that Aβ immunotherapy increases neuroinflammatory responses in the retina.

Figure 4.

Enhanced astrogliosis in Tg2576 mouse retinas following vaccinations. Immunofluorescence microscopy reveals GFAP immunoreactivity (green) as a marker for astrocytes or Müller cells and Aβ deposition (red) in the retinas from different treatment groups as indicated at the top of the figure. Cell nuclei are counterstained blue by 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole in the merged images. Background fluorescence is evident in the sclera (s) and pigment epithelium-choroid layer (p) in columns AO and AF. WT, wild-type; Tg, transgenic; Ctl, Control (sham-vaccinated Tg2576); AF, Aβ fibrils; onl, outer nuclear layer; opl, outer plexiform layer; inl, inner nuclear layer; ipl, inner plexiform layer; g, ganglion cell layer. Scale bar = 90 μm.

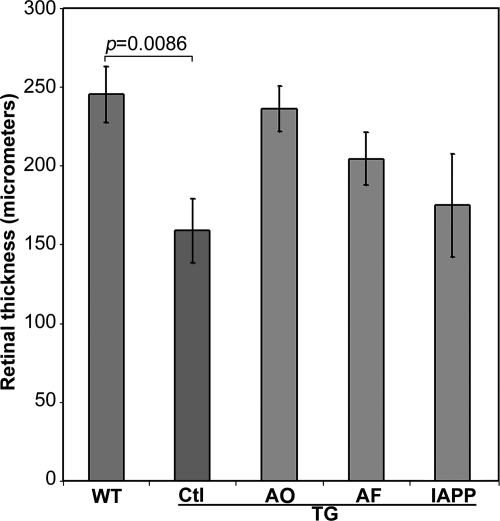

Aβ-Related Vaccinations Differentially Modify Retinal Thickness in Tg2576 Mice

Loss of ganglion cells as well as other retinal neurons has been demonstrated in both human postmortem tissue and mouse models of AD.17,45,54 Reduced retinal thickness, a manifestation of cell loss, has been detected in patients with AD.13,55,56 Because disruption of retinal architecture was evident in Tg2576 mice, the retinal thickness from the surface of the ganglion cell layer to the outside border of the outer nuclear layer was assessed. A significant decrease in the thickness of the retina was found in Tg2576 control mice in comparison with wild-type mice (P = 0.0086; Figure 5). Interestingly, the decrease in retinal thickness was attenuated following a 10-month vaccination protocol, although overall retinal thickness was still reduced compared with wild-type mice.

Figure 5.

Morphormetric analysis of the retinas from wild-type mice and Tg2576 mice that received different vaccinations. Measurements of retinal thickness were made from the ganglion cell layer to the outside border of the outer nuclear layer. WT, wild type; Tg, transgenic; Ctl, Control (sham-vaccinated Tg2576); AF, Aβ fibrils. Bars depict mean ± SEM (n = 7–9).

Discussion

The data presented here are the first demonstration of not only Aβ plaques and amyloid angiopathy in the retina of Tg2576 AD mice but also the effects on retinal pathology of Aβ-related immunotherapy. Detection of the Aβ plaques was confirmed using four different anti-Aβ monoclonal antibodies as well as Congo red fluorescence. Moreover, accumulation of Aβ deposits has been linked with hyperphosphorylation of tau protein, another pathological feature of AD, possibly through the cdk5-mediated phosphorylation pathway in the Tg2576 mouse brain.48,49 In this study, we also found a hyperphosphorylated form of tau associated with Aβ plaques within the retina. Vaccination with either a specific prefibrillar oligomeric conformation of Aβ peptide, Aβ fibrils, or human IAPP prefibrillar oligomers differentially reduced retinal Aβ deposits in the Tg2576 mice. The changes mediated by both AOs and IAPP prefibrillar oligomers in the retinas were statistically significant and in agreement with the changes in the hippocampus (Figure 6, Supplementary information) and neocortex as well as previous studies.28 Resembling cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the brain, however, there was robust microvascular Aβ deposition in the retina of AD transgenic mice and a significant increase in the amyloid angiopathy score following each of the immunotherapy regimens. This is consistent with the pathological changes reported in the brain of Alzheimer’s transgenic mice following Aβ-based immunotherapy.57,58 In this regard, the pathological changes in the retina of Alzheimer’s mice seem to parallel those in their brain (Supplemental Figure S1, see http://ajp.amjpathol/org). Our findings of increased microvascular deposition of Aβ support the notion that vaccination-induced antibodies solubilize Aβ plaques and promote Aβ infiltration into the perivascular space.59,60 Notably, Aβ plaques are observed in the retina of other mouse models of AD such as APPswe/PS1ΔE926 and 3xTg-AD mice (Z. Tan, unpublished observation). Evaluation of retinal amyloid angiopathy may provide an alternative avenue to monitor Aβ clearance mediated by immunotherapy. Additionally, our results demonstrate increased retinal neuroinflammation in AD transgenic mice as shown by immunoreactivity of both the astrocytic marker, GFAP, and the microglial marker, IBA1. As previously proposed, microglial infiltration and astrogliosis may play important roles in Aβ clearance from the central nervous system.61,62,63

Interestingly, although intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ was reported in association with ganglion cell degeneration in Tg2576 mice, no Aβ-associated plaques were found in their retinas in the previous studies.45 Failure to detect retinal Aβ plaques in that study might be explained by variations between different mouse colonies and/or the immunoreactivity of the anti-Aβ antibodies used for Aβ detection. Once the correlation between retinal and brain pathology and cognitive abnormalities is strengthened in the murine models, detection of retinal Aβ might potentially provide an alternative noninvasive approach to assess progression of AD and response to therapy.

Our study also revealed a significant reduction in retinal thickness in the Tg2576 mice compared with the wild-type mice. This is supported by the observations of retinal degeneration in Tg2576 mice in association with intraneuronal Aβ accumulation.45 In addition, Aβ deposits could directly disrupt the organization of the retinal neuropil.26 Although the retinal thickness was partially restored by immunotherapy in our study, the laminar organization of the retina of immunized AD mice was severely disrupted. This might be caused by the enhanced neuroinflammatory response, including infiltration of inflammatory cells and local edema. Importantly, destruction of the retinal architecture because of inflammation and Aβ deposition is associated with severe vision deficits in a vision-based behavioral paradigm (S. Rasool and C. G. Glabe, unpublished observation). In addition, electroretinogram abnormalities have been reported along with Aβ deposition in APPswe/PS1ΔE9 double-transgenic mice,26 and impairment of visual function and visuospatial recognition was previously observed in aged Tg2576 mice.64,65 Thus, the findings reported here and by other investigators regarding retinal damage in AD transgenic mice provide direct physical evidence for the basis of the visual deficits. Because most of the commonly used behavioral paradigms, for example, novel object recognition and water maze learning, require relatively preserved visual function, the overt retinal damage observed in AD transgenic mice may impair performance on these and other vision-based behavioral tasks.66 Therefore, the use of multifaceted behavioral measures may provide a more accurate assessment of cognitive performance in transgenic mouse models of AD. Further studies are warranted to examine correlations between Aβ-associated retinopathy and changes in functional parameters such as the electroretinogram and visual acuity in AD transgenic mice with and without Aβ immunotherapy.

Notably, impairments of visual function were documented in patients with AD more than two decades ago.15,67 Retinal pathology, including ganglion cell degeneration and optic nerve atrophy, might account for such visual function defects.17,54,68 Noninvasive techniques such as fundoscopy, electroretinography, and optical coherence tomography have confirmed the presence of abnormal retinal structure and visual dysfunction in patients with AD.18,20,56,69,70 Historically, Aβ deposits in the AD retina have been difficult to detect because of technical limitations. Recent advances in ocular imaging and immunohistochemistry suggest that current methods may now be able to visualize retinal Aβ.

In summary, our results demonstrate Aβ plaques with increased retinal microvascular deposition of Aβ and neuroinflammation in Tg2576 mouse retinas. Aβ and IAPP prefibrillar oligomer vaccinations reduce retinal Aβ deposits but increase retinal microvascular Aβ deposition and exacerbate local neuroinflammation manifested by microglial infiltration and astrogliosis linked with disruption of retinal organization. Current studies are aimed at evaluating the correlations between retinal and brain pathology as well as cognitive abnormalities in animal models and patients with AD. These studies may help to establish a noninvasive imaging modality to monitor disease progression and the response to therapeutic interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Vitaly Vasilevsko and Kim Green for their technical advice.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Zhiqun Tan, M.D., Ph.D., University of California Irvine School of Medicine/Neurology, 100 Irvine Hall, Zot 4275, Irvine, CA 92697-4275; or Jian Ge, M.D., Ph.D., Professor and Director, Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-sen University, 54 S. Xianlie Road, Guangzhou 510060, China. E-mail: cjiange@hotmail.com and tanz@uci.edu.

Supported by research grants from Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation (290202; to Z.T.), Basic Research Program of China (2007CB512200; to J.G.), University of California Discovery Grant Program, and the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation (to C.G.G.).

B.L. and S.R. contributed equally to this work.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

C.G.G. has stock in and has received consulting fees from Kinexis, Inc.

References

- Yankner BA, Lu T, Loerch P. The aging brain. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:41–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.2.010506.092044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: prospects for clinical diagnosis and treatment. Neurology. 1998;51:690–694. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, O'Banion MK. Inflammatory processes in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;184:69–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankner BA, Lu T. Amyloid β-protein toxicity and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem. 2009:4755–4759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800018200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2004;430:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head E, Lott IT. Down syndrome and β-amyloid deposition. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:95–100. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200404000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pache M, Smeets CH, Gasio PF, Savaskan E, Flammer J, Wirz-Justice A, Kaiser HJ. Colour vision deficiencies in Alzheimer’s disease. Age Ageing. 2003;32:422–426. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D, Crutch SJ, Warrington EK. A disorder of colour perception associated with abnormal colour after-images: a defect of the primary visual cortex. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:515–517. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.4.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshminarayanan V, Lagrave J, Kean ML, Dick M, Shankle R. Vision in dementia: contrast effects. Neurol Res. 1996;18:9–15. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1996.11740369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendola JD, Cronin-Golomb A, Corkin S, Growdon JH. Prevalence of visual deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. Optom Vis Sci. 1995;72:155–167. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker KW, Burdon MA, Shah P. Visual field loss and Alzheimer’s disease. Eye. 2002;16:206–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetewsky SJ, Duffy CJ. Visual loss and getting lost in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1999;52:958–965. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butter CM, Trobe JD, Foster NL, Berent S. Visual-spatial deficits expalin visual symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71969-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Rimmer S. Ophthalmologic manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 1989;34:31–43. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(89)90127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseri PK, Altinas O, Tokay T, Yuksel N. Relationship between cognitive impairment and retinal morphological and visual functional abnormalities in Alzheimer disease. J Neuroophthalmol. 2006;26:18–24. doi: 10.1097/01.wno.0000204645.56873.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanks JC, Hinton DR, Sadun AA, Miller CA. Retinal ganglion cell degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 1989;501:364–372. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90653-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquet C, Boissonnot M, Roger F, Dighiero P, Gil R, Hugon J. Abnormal retinal thickness in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007;420:97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesh-Meyer HV, Birch H, Ku JY, Carroll S, Gamble G. Reduction of optic nerve fibers in patients with Alzheimer disease identified by laser imaging. Neurology. 2006;67:1852–1854. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244490.07925.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CS, Ritch R, Schwartz B, Lee SS, Miller NR, Chi T, Hsieh FY. Optic nerve head and nerve fiber layer in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:199–204. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080020045040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DR, Sadun AA, Blanks JC, Miller CA. Optic-nerve degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:485–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198608213150804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon SJ, Lehman DM, Kerrigan-Baumrind LA, Merges CA, Pease ME, Kerrigan DF, Ransom NL, Tahzib NG, Reitsamer HA, Levkovitch-Verbin H, Quigley HA, Zack DJ. Caspase activation and amyloid precursor protein cleavage in rat ocular hypertension. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1077–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson GA, Edward DP, Wilensky JT. Ocular amyloidosis and secondary glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1363–1366. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)00726-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederikse PH, Ren XO. Lens defects and age-related fiber cell degeneration in a mouse model of increased AβPP gene dosage in Down syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1985–1990. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64475-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LE, Muffat JA, Cherny RA, Moir RD, Ericsson MH, Huang X, Mavros C, Coccia JA, Faget KY, Fitch KA, Masters CL, Tanzi RE, Chylack LT, Jr, Bush AI. Cytosolic β-amyloid deposition and supranuclear cataracts in lenses from people with Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2003;361:1258–1265. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12981-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez SE, Lumayag S, Kovacs B, Mufson EJ, Xu S. β-Amyloid deposition and functional impairment in the retina of the APPswe/PS1δE9 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:793–800. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Fonseca MI, Kayed R, Hernandez I, Webster SD, Yazan O, Cribbs DH, Glabe CG, Tenner AJ. Novel Aβ peptide immunogens modulate plaque pathology and inflammation in a murine model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Head E, Sarsoza F, Saing T, Cotman CW, Necula M, Margol L, Wu J, Breydo L, Thompson JL, Rasool S, Gurlo T, Butler P, Glabe CG. Fibril specific, conformation dependent antibodies recognize a generic epitope common to amyloid fibrils and fibrillar oligomers that is absent in prefibrillar oligomers. Mol Neurodegener. 2007;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman S, Koller M, Black RS, Jenkins L, Griffith SG, Fox NC, Eisner L, Kirby L, Rovira MB, Forette F, Orgogozo JM. Clinical effects of Aβ immunization (AN1792) in patients with AD in an interrupted trial. Neurology. 2005;64:1553–1562. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159740.16984.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Glabe CG. Conformation-dependent anti-amyloid oligomer antibodies. Methods Enzymol. 2006;413:326–344. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)13017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania C, Sotiropoulos I, Silva R, Onofri C, Breen KC, Sousa N, Almeida OF. The amyloidogenic potential and behavioral correlates of stress. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:95–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi RE, McClatchey AI, Lamperti ED, Villa-Komaroff L, Gusella JF, Neve RL. Protease inhibitor domain encoded by an amyloid protein precursor mRNA associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1988;331:528–530. doi: 10.1038/331528a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisodia SS, Price DL. Role of the β-amyloid protein in Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 1995;9:366–370. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.5.7896005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung SS, Gauthier S, Cashman NR. β-Amyloid precursor protein is detectable on monocytes and is increased in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1999;20:249–257. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvathy S, Davies P, Haroutunian V, Purohit DP, Davis KL, Mohs RC, Park H, Moran TM, Chan JY, Buxbaum JD. Correlation between Aβx-40-. Aβx-42-, and Aβx-43-containing amyloid plaques and cognitive decline. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:2025–2032. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.12.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viale G, Gambacorta M, Coggi G, Dell’Orto P, Milani M, Doglioni C. Glial fibrillary acidic protein immunoreactivity in normal and diseased human breast. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1991;418:339–348. doi: 10.1007/BF01600164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarthy PV, Fu M, Huang J. Developmental expression of the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) gene in the mouse retina. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1991;11:623–637. doi: 10.1007/BF00741450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito D, Imai Y, Ohsawa K, Nakajima K, Fukuuchi Y, Kohsaka S. Microglia-specific localisation of a novel calcium binding protein, Iba1. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;57:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M, Jakes R, Vanmechelen E. Monoclonal antibody AT8 recognises tau protein phosphorylated at both serine 202 and threonine 205. Neurosci Lett. 1995;189:167–169. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11484-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchihara T, Akiyama H, Kondo H, Ikeda K. Activated microglial cells are colocalized with perivascular deposits of amyloid-β protein in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Stroke. 1997;28:1948–1950. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.10.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Z, Sankar R, Tu W, Shin D, Liu H, Wasterlain CG, Schreiber SS. Immunohistochemical study of p53-associated proteins in rat brain following lithium-pilocarpine status epilepticus. Brain Res. 2002;929:129–138. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry MC, McNamara M, Fedorchak K, Hsiao K, Hyman BT. APPSw transgenic mice develop age-related Aβ deposits and neuropil abnormalities, but no neuronal loss in CA1. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:965–973. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199709000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning A, Cui J, To E, Ashe KH, Matsubara J. Amyloid-beta deposits lead to retinal degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5136–5143. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, Mori H, Saido T, Kondo H, Ikeda K, McGeer PL. Occurrence of the diffuse amyloid β-protein (Aβ) deposits with numerous Aβ-containing glial cells in the cerebral cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Glia. 1999;25:324–331. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(19990215)25:4<324::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terai K, Iwai A, Kawabata S, Tasaki Y, Watanabe T, Miyata K, Yamaguchi T. β-Amyloid deposits in transgenic mice expressing human β-amyloid precursor protein have the same characteristics as those in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2001;104:299–310. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otth C, Concha II, Arendt T, Stieler J, Schliebs R, Gonzalez-Billault C, Maccioni RB. AβPP induces cdk5-dependent tau hyperphosphorylation in transgenic mice Tg2576. J Alzheimers Dis. 2002;4:417–430. doi: 10.3233/jad-2002-4508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomidokoro Y, Harigaya Y, Matsubara E, Ikeda M, Kawarabayashi T, Shirao T, Ishiguro K, Okamoto K, Younkin SG, Shoji M. Brain Aβ amyloidosis in APPsw mice induces accumulation of presenilin-1 and tau. J Pathol. 2001;194:500–506. doi: 10.1002/path.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Sisk A, Mallory M, Games D. Neurofibrillary pathology in transgenic mice overexpressing V717F β-amyloid precursor protein. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:357–368. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski HM, Vorbrodt AW, Wegiel J. Amyloid angiopathy and blood-brain barrier changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;826:161–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani RJ, Smith MA, Perry G, Friedland RP. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: major contributor or decorative response to Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:599–602; discussion 603–594. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang-Nunes SX, Maat-Schieman ML, van Duinen SG, Roos RA, Frosch MP, Greenberg SM. The cerebral β-amyloid angiopathies: hereditary and sporadic. Brain Pathol. 2006;16:30–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2006.tb00559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NR. Alzheimer’s disease, optic neuropathy, and selective ganglion cell damage. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:7–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keri S, Antal A, Kalman J, Janka Z, Benedek G. Early visual impairment is independent of the visuocognitive and memory disturbances in Alzheimer’s disease. Vision Res. 1999;39:2261–2265. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(98)00310-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi V, Restuccia R, Fattapposta F, Mina C, Bucci MG, Pierelli F. Morphological and functional retinal impairment in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1860–1867. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(01)00620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrushina I, Ghochikyan A, Mkrtichyan M, Mamikonyan G, Movsesyan N, Ajdari R, Vasilevko V, Karapetyan A, Lees A, Agadjanyan MG, Cribbs DH. Mannan-Aβ28 conjugate prevents Aβ-plaque deposition, but increases microhemorrhages in the brains of vaccinated Tg2576 (APPsw) mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:42. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcock DM, Jantzen PT, Li Q, Morgan D, Gordon MN. Amyloid-β vaccination, but not nitro-nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug treatment, increases vascular amyloid and microhemorrhage while both reduce parenchymal amyloid. Neuroscience. 2007;144:950–960. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carare RO, Bernardes-Silva M, Newman TA, Page AM, Nicoll JA, Perry VH, Weller RO. Solutes, but not cells, drain from the brain parenchyma along basement membranes of capillaries and arteries: significance for cerebral amyloid angiopathy and neuroimmunology. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2008;34:131–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boche D, Zotova E, Weller RO, Love S, Neal JW, Pickering RM, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Nicoll JA. Consequence of Aβ immunization on the vasculature of human Alzheimer’s disease brain. Brain. 2008;131:3299–3310. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard F, Cannon C, Barbour R, Burke RL, Games D, Grajeda H, Guido T, Hu K, Huang J, Johnson-Wood K, Khan K, Kholodenko D, Lee M, Lieberburg I, Motter R, Nguyen M, Soriano F, Vasquez N, Weiss K, Welch B, Seubert P, Schenk D, Yednock T. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid β-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2000;6:916–919. doi: 10.1038/78682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Alloza M, Ferrara BJ, Dodwell SA, Hickey GA, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ. A limited role for microglia in antibody mediated plaque clearance in APP mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;28:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsonego A, Weiner HL. Immunotherapeutic approaches to Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2003;302:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1088469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Cudennec C, Faure A, Ly M, Delatour B. One-year longitudinal evaluation of sensorimotor functions in APP751SL transgenic mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7(Suppl 1):83–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale G, Good M. Impaired visuospatial recognition memory but normal object novelty detection and relative familiarity judgments in adult mice expressing the APPswe Alzheimer’s disease mutation. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:884–891. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.4.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Wong AA. The influence of visual ability on learning and memory performance in 13 strains of mice. Learn Mem. 2007;14:134–144. doi: 10.1101/lm.473907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadun AA, Borchert M, DeVita E, Hinton DR, Bassi CJ. Assessment of visual impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:113–120. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(87)90001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanks JC, Schmidt SY, Torigoe Y, Porrello KV, Hinton DR, Blanks RH. Retinal pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. II. Regional neuron loss and glial changes in GCL. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:385–395. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(96)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strenn K, Dal-Bianco P, Weghaupt H, Koch G, Vass C, Gottlob I. Pattern electroretinogram and luminance electroretinogram in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1991;33:73–80. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9135-4_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berisha F, Feke GT, Trempe CL, McMeel JW, Schepens CL. Retinal abnormalities in early Alzheimer’s disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2285–2289. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.