Abstract

We tested the effect of multiple exemplar instruction on the transfer of stimulus function for unfamiliar pictures across listener responses (i.e., matching and pointing) and speaker responses (i.e., pure tacts and impure tacts). Three preschool students, who were 3- and 4-year-old males and did not have the listener to speaker component of the naming repertoire, participated in the experiment. The dependent variable was numbers of correct responses to probe trials of both untaught listener responses (“point to__”) and speaker responses (tact and impure tacts) following mastery of matching responses for two sets of five unfamiliar pictures (Set 1 and Set 3). After each participant mastered matching (e.g., “match Labrador”) for Set 1 pictures they were probed on the three untaught responses to Set 1 words. That is, they were asked to point to Labrador, tact the picture of Labrador, and respond to the picture of a Labrador and the question “What is this?” Next, the participants were taught mastery of all four types of responses using MEI for a second set of five pictures (Set 2) and probed again on the 3 untaught Set 1 responses. Finally, matching responses were taught to mastery for a novel set of pictures (Set 3) and then probed on the three untaught responses. The results showed that untaught speaker responses emerged at 60% to 85% for two participants, and 40%–70% for one participant. We discuss the role of instructional history in the development of the listener to speaker component of naming.

Keywords: naming, generative verbal behavior, novel verbal behavior, multiple exemplar experiences

Naming is a fundamental verbal repertoire (Greer & Keohane, 2004). Children with naming repertoires can hear caretakers' tact a stimulus and respond to the stimulus as both a listener and a speaker without direct instruction. A caretaker on seeing a small blue bird directs the child's attention to the bird and says, “That's a blue bunting.” If the child has naming, the child, as a listener, can point to the blue bunting when asked to “Point to the blue bunting.” The child can also respond with a pure tact as a speaker as well tact the name of the bird when the bird is present and the child is asked, “What is that?” Naming allows the proliferation of vocabulary.

Naming is a higher class that involves arbitrary stimulus classes (things or events with particular names) and corresponding arbitrary verbal topographies (the words serve as their names) in a bidirectional relationship. Prerequisites for naming include at least three components: 1) listener behavior, in looking for things and pointing based on what's been said; 2) echoic behavior, in repeating names when they are spoken; and 3) tacting, in saying the names given the objects. Naming is generated from the ordinary interactions between children and their caretakers. Once available as a higher-order class, naming allows expansions of vocabulary in which the introduction of new words in particular functional relations (such as tacting) involves these words in a range of other emergent classes. (Catania, 1998, p. 398)

Instructional responses such as match-to-sample, point-to, pure tact, and impure tact responses are all different behaviors that can be emitted to common stimuli. Young children, or individuals with developmental delays, who can match pictures as a teacher speaks the word for the picture, such as matching the picture of a Labrador to another picture of a Labrador, cannot necessarily point to the same picture when then asked to point to the picture of a Labrador among an array of other pictures. However, only the point-to response tests the listener response. That is, children may successfully match pictures without being under the control of the teacher's spoken word by responding to the visual stimuli solely. However, in a pointing response that is done after the initial an exposure of matching while hearing the name, the child must be under the control of the spoken word in addition to the visual stimuli, while in the match response the child can be under the visual stimulus control but may not be under the control of the spoken word of the teacher. In the latter case the listener component of naming is absent. Most typically developing children, at some point, do acquire the listener response after hearing the name of the stimulus as part of the matching instruction. However, when students can match the picture and point to pictures (i.e., have the listener response), but cannot emit pure or impure tacts to the same pictures without direct instruction (i.e., they cannot tact the picture) they are missing the speaker component of naming. The pointing response is a listener response and the tact response is a speaker responses. However, most children do learn to acquire speaker responses after learning a listener response at some point, and this listener to speaker relationship is another of the components of naming (Catania, 1998).

Learning to emit tact after learning the listener responses is a key component of naming, and naming makes the rapid and incidental expansion of tact responses to novel stimuli possible. While naming involves a bidirectional relation between speaker and listener, one key component is the capability to emit speaker responses after hearing the spoken word, the echoic response, and then the tact response. This bidirectional phenomenon of naming was identified and experimentally isolated by Horne and Lowe (Horne & Lowe, 1996; Lowe, Horne, Harris, & Randle, 2002). Of course, the echoic is a key component of naming, but this is expressed most commonly in the appearance of the tact response and the tact response for a new spoken word requires the echo in a kind of echoic-to-tact function.

Naming is one type of speaker-as-own-listener response (Lodhi & Greer, 1989; Lowe et al., 2002; Skinner, 1957). Naming includes the presence of joint stimulus control from listener to speaker functions; that is, learning the listener responses occasions a tact response. By joint control, we mean a single stimulus controls two different responses as in the case in which written and spoken spelling responses are controlled by the same stimulus. The student can spell the word in the two different responses; therefore, the stimulus has joint control over the two different behaviors. The naming repertoire has been classified as a higher order operant (Catania, 1998) or a relational frame (Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Homes, & Cullinan, 2001). The identification of the controlling variables for the acquisition of this joint stimulus control across different operants is of interest to the basic and applied science.

Multiple exemplar instruction is a procedure that has resulted in the development of either (a) abstract stimulus control (Becker, 1992) or (b) joint stimulus control for what was originally independent verbal operants (Greer, Yuan, & Gautreaux, 2004). Becker (1992) summarized a research and an application program for the development of the abstraction for classes of stimuli through multiple exemplar instruction. Fields et al. (2003) demonstrated the formation of generalized categorizations as a function of training with multiple domains, samples, and comparisons. Both the Becker (1992) and the Fields et al. (2003) research identified the role of multiple exemplar experiences or instruction in the acquisition of essential stimulus control or abstractions. In research that identified the emergence of joint stimulus control for initially independent operants, Greer, Chavez-Brown, Nirgudkar, Stolfi, and Rivera-Valdes (2003a) demonstrated untaught novel responses across spoken and written spelling as a function of multiple exemplar instruction for a subset of spelling words. In other work, Nuzzolo-Gomez and Greer (2004) also reported emergence of joint establishing operation control across the mand and tact functions as a function of multiple exemplar instructional history and Greer, Nirgudkar, and Park (2003b) replicated this finding. Thus, a stimulus may acquire joint control of different responses such as writing and saying, or a single response may come under the control of different establishing operations.

In the experiments reported herein we tested whether the participants who could not emit speaker responses after learning listener responses would do so after experiencing multiple exemplar instruction across speaker and listener responding with a training subset of pictures. We wanted to determine if children who did not have the listener-to-speaker component of naming with pictures would do so after multiple exemplar experiences. If joint stimulus control resulted from the MEI, when our children were taught matching to sample with unfamiliar pictures on hearing the words for the pictures, they would point to the picture upon hearing the word for the picture, and tact the picture as a pure tact, or as an impure tact in the presence of the picture and the question “What is it?”

METHOD

Participants

There were three participants in the study, Participants A, C, and D. They all attended a publicly funded preschool for children with and without developmental delays that used a behavior analytic approach to all instruction. The children's existing academic, verbal, self-management, problem solving repertoires and their community of reinforcers were determined by assessments with the PIRK (Greer & McCorkle, 2003). According to the PIRK, none of these children had the naming repertoire and they were selected for participation based on their lack of a naming repertoire.

Participant A was a three-year-old male, diagnosed as having language delays at entry to the school; however, at the time of the experiment he performed close to his age level norms. He functioned at a basic listener and speaker level of verbal behavior (Greer & Keohane, 2004). He textually responded to 19 of the 26 uppercase letters and the numbers 1 through 20. He followed one-step directions, matched and pointed to pictures of classes of stimuli across irrelevant dimensions, and emitted social intraverbals. He emitted single utterance mands, as well as tacts of pictures and objects.

Participant C was a four-year-old male diagnosed as having a developmental delay at entry to the school. At the time of the experiment he functioned on a listener/speaker emergent reader/writer level of verbal behavior; that is, he performed at or above the level of his typically developing peers. The participant followed one-step vocal directions, emitted appropriate rates of social intraverbals, and textually responded to all letters and the numbers 1 through 10. He was just beginning to imitate basic writing strokes.

Participant D was 2.5-year-old male diagnosed as having a developmental delay at entry to the school. At the time of the experiment he functioned at a listener/speaker emergent reader level of verbal behavior consistent with same age peers. He emitted mands and tacts using autoclitics, as well as intraverbal responses. He did not emit conversational units.

Setting

The study was conducted in a publicly funded private school for children with developmental delays, behavioral problems, and for typically developing children located in a major metropolitan area. The school used the CABAS® (Comprehensive Application of Behavior Analysis to Schooling) model of instruction (Greer, 2003; Greer, Keohane, & Healey, 2002). All instruction was presented in the form of learn units (Bahadorian, 2000; Emurian, Hu, Wang, & Durham, 2000; Greer, 2003; Greer & McDonough, 1999).

The experiment was conducted in two classrooms in which five other children received individualized behavior analytic instruction by one teacher and one or two teacher assistants. The responses of all of the children in the classroom to all instruction were measured as learn units. Probes of the participants were also conducted with instructional stimuli as a means of testing the presence or absence of certain repertoires. Thus, the procedures received by the participants were the same as those received by all children in the classroom. Each child sat at a child-sized table in a child-sized chair while the data collector also sat at the table along with the independent observer when the independent observer was present. Other children were receiving small group or individual instruction at adjacent tables.

Definition of the Behaviors

The behaviors consisted of match, point-to, pure tact, and impure tact responses (i.e., responses to “What's this?”) to Sets of five pictures. Set 1 consisted of pictures of 5 national monuments, Set 2 of 5 dog breeds, and Set 3 of 5 constructed pictures with arbitrary nonsensical names. Each response of 1) match, 2) point-to, 3) pure tact, and 4) impure tact (with a teacher verbal antecedent) for all three sets of five pictures were probed separately in separate 20-trial sessions for each set of pictures requiring the students to respond four times to the five pictures. Participants matched the pictures by placing the target picture on a matching picture when presented with the target picture and a rotating non-target picture following the teacher saying, “Match ___ [picture name].” Point-to responses consisted of pointing to the target picture in an array of pictures consisting of the target picture and other pictures as the negative exemplars (sometimes referred to as foils), following the teacher saying, “Point to ___.” These negative exemplars were changed across presentations. The pure tact response consisted of the child saying the name of the stimulus following the teacher's presentation of the picture with no verbal antecedent. The impure tact response consisted of the participant saying the name of the picture following the presentation of the picture and the teacher saying, “What's this?” Each of the sets of pictures was counterbalanced across participants to control for picture difficulty and to insure that the responses were not echoic. The specific pictures and the counterbalance scheme of pictures across the Participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sets of Pictures for Participants for Participants A, B, and C.

| Participant | Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 |

| D | Labrador | Statue of Liberty | Lev |

| Collie | Grand Canyon | Fleek | |

| Poodle | Liberty Bell | Fleg | |

| German Shepard | White House | Weg | |

| Doberman | Mount Rushmore | Ceeg | |

| C | Lev | Statue of Liberty | Labrador |

| Fleek | Grand Canyon | Collie | |

| Fleg | Liberty Bell | Poodle | |

| Weg | White House | German-Shepard | |

| Ceeg | Mount Rushmore | Doberman | |

| A | Statue of Liberty | Lev | Labrador |

| Grand Canyon | Fleek | Collie | |

| Liberty Bell | Fleg | Poodle | |

| White House | Weg | German Shepard | |

| Mount Rushmore | Ceeg | Doberman |

Data Collection

Data were collected for the dependent variable in sessions consisting of 20-probe trials that consisted of presentations followed by the opportunity to respond within 3 seconds of the presentation. Correct and incorrect responses to probe and learn unit presentations were recorded on a data form using pencil and paper. A correct response was recorded as a plus (+), and an incorrect response was recorded as a minus (−). Data were graphed as the number of correct responses per session. There were no reinforcement operations or corrections following probe-trial response opportunities

Data were collected in the same manner for responses during instructional sessions. However, these data consisted of responses to learn units that were conducted for instruction in the match-to-sample responses taught for Sets 1 and 3 prior to probing for the untaught Set 1 and Set 3 responses consistent with the design (Greer & McDonough, 1999). Data were also collected on responses to learn units for teaching Set 2 pictures using the multiple exemplar procedure as a test of the fidelity of treatment for mastery of Set 2 under multiple exemplar conditions.

Correct responses included: matching pictures when given the instruction, “Match the picture of the ___ [name of picture spoken by the teacher]”; pointing to the corresponding picture when given the antecedent “Point to the ___ [tact of picture spoken by the teacher],” tacting the picture when presented with picture alone and no verbal antecedent (student tacts the picture after the teacher presents the picture with no spoken teacher antecedent), and impure tact responses to the picture in the presence of the picture when the teacher asks, “What is this?” In the multiple exemplar instruction the response types for the stimuli were rotated. For example, match, point-to, pure tact, and impure tact for Labrador; match, point-to, pure tact, and impure tact for Collie; and so on for Poodle, German Shepard, and Doberman; thus, four responses for five pictures totaling 20 trials. Incorrect responses included: matching or pointing to the incorrect picture, emitting an incorrect pure tact, emitting an incorrect impure tact, emitting no response at all, or producing vocal responses that were unintelligible to the instructor and/or observer. If the student did not respond within 3 seconds the response was also counted as incorrect.

Interobserver Agreement

Interobserver agreement observations were conducted for 61% of the total sessions, and the percentage of agreements was 100% for all sessions done with an independent observer. The interobserver agreement scores were calculated by dividing the total numbers of paired observer agreements by the total numbers of agreements plus disagreements, and then multiplying that number by 100%.

Design

A multiple-probe design across word sets and across participants was used in which untaught responses were probed following each of the two training conditions (Horner & Baer, 1978). Probes were time lagged across participants according to multiple baseline logic, thus controlling for maturation and instructional history resulting in a true experimental design. The sequence of steps in the experiment consisted of 1) pre-experimental probes for all pictures for all four types of responses, 2) baseline instruction in matching responses for Set 1 pictures in which the child hears the name of the picture (i.e., “match ____”), 3) probes on untaught responses to Set 1 pictures (point-to, tact response with no verbal antecedent and a tact response with verbal antecedent), 4) Multiple exemplar instruction, alternating the four responses to Set 2 pictures until mastery, 5) post MEI probes to untaught responses for Set 1 pictures, 6) mastery instruction for matching with Set 3 pictures, again with the children hearing the name for the picture they were to match, and 7) probes of untaught functions for Set 3 pictures. Each of these phases is described in detail below.

Pre-experimental probe conditions. The instructor presented each of the three sets of five pictures under probe-trial conditions prior to the baseline. Each of the five pictures in a set was presented four times and counterbalanced such that the child could not receive a correct response by echoing. The probes consisted of four response types for each of the five pictures and each picture had four opportunities to respond for a total of 80 preexperimintal probe trials. The probes were arranged so that they were presented in a counterbalanced order within and across participants.

Baseline procedures. During baseline teaching conditions each child was taught matching responses using learn unit presentations and the teacher spoke the name of the picture as the child matched (Greer & McDonough, 1999). That is, when students emitted correct responses they received a consequence that functioned as a generalized reinforcer for them in their instructional programs (e.g., praise or tokens for backup reinforcers). When they emitted an incorrect response, the teacher provided a correction that the child repeated, while the child was attending to the picture card. These conditions define the learn unit. The criterion for mastery was set at 90% accuracy across two consecutive sessions, or 100% for a single session. Once criterion was met for the matching responses, a probe was conducted for the untaught repertoires—pointing, tacting with no teacher verbal antecedent, and tacting after the teacher asked, “What is this?” Again, the four response types for the five pictures in the set were probed four times. Following the probes, the students were introduced to the multiple exemplar instruction for Set 2 words that they were taught to mastery.

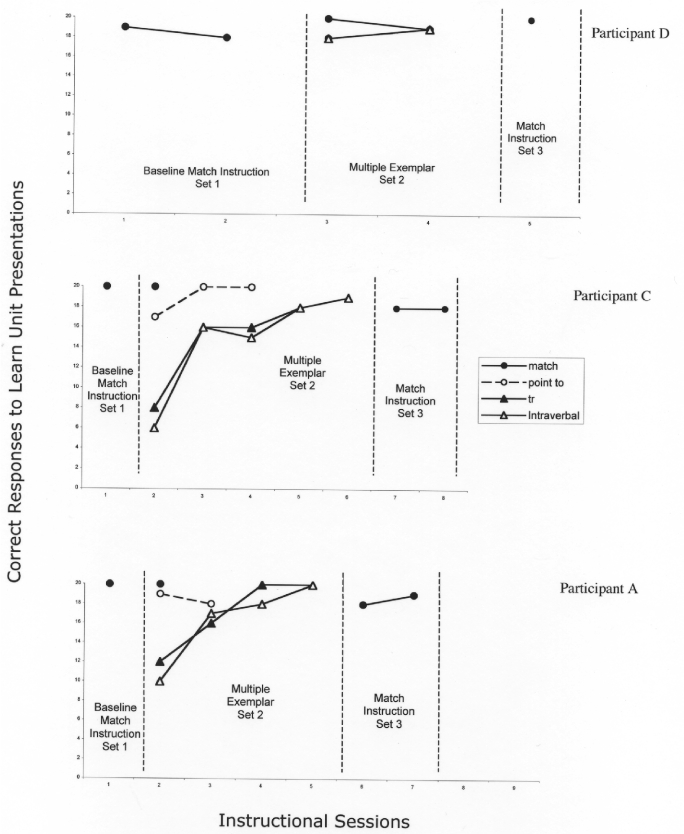

Multiple exemplar instruction. During multiple exemplar instruction, the participants were taught all repertoires for Set 2 pictures, using learn units that were rotated across all responses as the method of instruction. A single complete multiple exemplar exposure for a picture set (Set 2) consisted of 80 learn unit presentations in which the opportunity to emit a response for a given repertoire was rotated within the session. That is, the student matched picture 1 in the first learn unit, followed by a matching learn unit for picture 2. Pictures 3, 4, and 5, respectively, were introduced during subsequent matching learn units. Next, five learn units, one for each picture, were presented for each of the other repertoires in the manner described above (i.e., point-to, tact without a verbal antecedent, and tact with a verbal antecedent). To avoid fatigue the actual instructional sessions, a single seating, consisted of sessions of 20-learn units with a single response opportunity for each of the five pictures with each of the response types. For visual display purposes, the data were cumulatively blocked into 20-trial sessions according to the response types to determine mastery of the pictures in a specific response (i.e. 20 learn unit blocks for each response). When the student had met the criterion for all four responses to the five pictures (90% accuracy in two consecutive sessions or 100% for a single session) the MEI concluded (See Figure 2). If the child met the criterion for a particular response before other responses, the mastered function(s) continued to be presented as an instructional antecedent until the nonmastered response(s) was/were mastered. The Set 2 pictures were the only ones taught using multiple exemplar instruction, and these pictures were not used in any other part of the study. Figure 2 shows the acquisition and mastery of each of the responses as an index of the fidelity of the treatment. The data are learning trend data and showed for the MEI phases that Participant D mastered the four responses in two sessions or 160 learn units, Participant C required 280 learn units, Participant A required 200 learn units. In the matching only instruction for the pre-MEI instruction for Set 1, Participants C and D required one session (20-learn units), while Participant D required 2 sessions (40 learn units). Following the MEI instruction for Set 2, mastering the matching response required two sessions (40 learn units) for Participants C and D, and one session (20 learn units) for Participant A.

Figure 2.

Correct responses to learn unit presentations of Participants A, B, and C while: (a) teaching them the match repertoire for their first set of pictures prior to the baseline; (b) providing the multiple exemplar instruction across point-to, pure tact, and impure tact responses for their second set of pictures (data points shown for each type of response); and (c) teaching them the match responses for their third set of pictures prior to the final probe for untaught speaker and listener responses. These data constitute measures of the implementation of the independent variable that was mastery of a subset of stimuli (Set 2 pictures) under MEI conditions.

Post MEI probes for untaught responses for Set 1 pictures. Following the MEI for Set 2 words the students were again probed on the untaught three functions for Set 1 pictures (point-to, pure tact, and impure tact) as they had been prior to the MEI instruction.

Matching instruction for Set 3 pictures. At this point, the participants were taught the matching repertoire only for Set 3 pictures using learn units as the method of instruction until they met criterion. This constituted the same procedure that was used in the baseline phase to teach the Set 1 pictures.

Probes for untaught responses for Set 3 words. Once the participants met criterion for matching Set 3 pictures, a probe was conducted for the untaught repertoires of Set 3 (pointing to, tacting without a verbal antecedent, and tacting with a verbal antecedent). That is, they were probed on the untaught responses to Set 3 pictures as they had been prior to the MEI for the untaught responses to Set 1 pictures in order to test for the emergence of the untaught speaker responses for Set 3 pictures.

RESULTS

The students' correct responses to the pictures prior to the experiment are shown in Table 2. These data show that the students had some matching responses for the unfamiliar pictures in their repertoire, fewer point-to responses, and minimal pure tact or impure tact responses. Since the point-to responses were forced choice responses the responses were at least in some cases attributable to chance. Also, the tact responses that were correct were probably also chance responses (e.g., the students repeated the same tact for all pictures).

Table 2.

Pre-experimental Probes of Match, Point-to, Pure Tact, and Impure Tact Responses (i.e., “What is this?”) for Participants D, C, and A.

| Participant | Match | Point-to | Pure Tact | Impure Tact |

| D | ||||

| Set 1 | 13 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Set 2 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Set 3 | 12 | 9 | 3 | 1 |

| C | ||||

| Set 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Set 2 | 13 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Set 3 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| A | ||||

| Set 1 | 18 | 13 | 1 | 3 |

| Set 2 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Set 3 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

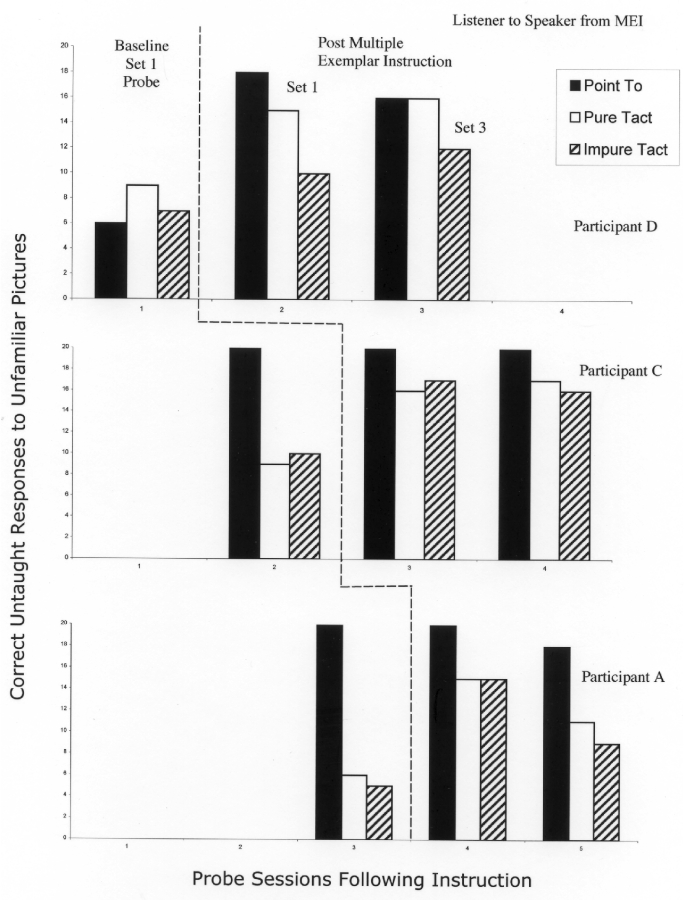

Figure 1 shows the participants' correct responses to the untaught listener or speaker response to the picture sets following mastery of the matching responses only for their first set of words, their responses to the first set of pictures following MEI with a separate or second set of pictures, and their responses to a third set of pictures after being taught the match responses only.

Figure 1.

Correct untaught listener and speaker responses to unfamiliar pictures for Participants A, B, and C following: (a) baseline matching instruction for their first set of pictures in which they heard the name of the picture spoken, (b) multiple exemplar instruction across response forms for their second set of pictures, and (c) matching instruction alone for their third set of pictures.

Participant D emitted 6 point-to responses, 9 pure tact responses, and 7 impure tact responses to his first set of pictures following mastery of the matching responses only. Following the MEI with a second set of pictures, he emitted 18 pointing, 16 pure tact, and 10 impure tact responses to his first set of pictures. Following mastery of the matching response with his third set he emitted the following untaught responses: 16 point-to, 16 pure tact, and 12 impure tact responses. More correct responses were emitted for pure tacts than for impure tacts; however, because no reinforcement operations were delivered for the probe trials, the responses for the impure tact probe followed 40 non-reinforced responses before the initiation of the impure tact probes.

Participant C emitted 20 correct pointing responses, 8 pure tacts, and 9 impure tact responses to his first set of pictures following mastery of the matching responses only. Following the MEI with a second set of pictures, he emitted 20 point-to, 16 pure tact, and 17 impure tact responses to his first set of pictures. Following mastery of the matching response with his third set he emitted the following untaught responses: 20 pointing, 17 pure tact, and 16 impure tact responses. There were little differences between pure and impure tacts.

Participant A emitted 20 point-to responses, 5 pure tact responses, and 4 impure tact responses to his first set of pictures following mastery of the matching responses only. Following the MEI with a second set of pictures, he emitted 20 point-to responses, 16 pure tact responses, and 16 impure tact responses to his first set of pictures. Following mastery of the matching response with his third set he emitted the following untaught responses: 18 pointing responses, 12 pure tact responses, and 9 impure tact responses. His impure tact responses were lower than the pure tact response for his Set 3 pictures. Also, his Set 3 speaker responses were lower than his speaker responses to his Set 2 pictures. The difference between his Set 1 and Set 3 responding may have been due to the fact that Set 3 pictures were novel; alternately, since probe responses were not reinforced, the differences between the two sets may be attributable to extinction effects.

During the first probe following the instruction in matching only, Participants C and A emitted either 19 or 20 correct responses on the point-to responses demonstrating that they had acquired the listener response following the matching instruction and their listener responding remained accurate for the other phases. Participant D emitted only 8 correct responses to the point-to probe showing lack of a listener repertoire. The listener repertoire emerged for Participant D after the MEI. None of the Participants demonstrated strong speaker repertoires prior to the MEI treatment with accuracy ranging from 4 to 9 correct response. Following MEI, Participant D emitted 16 or 17 accurate speaker responses to his Set 1 and Set 3 pure tact probes, with responding at 10 and 12 correct responses respectively on his impure probes. Participant C emitted 16 or 17 correct responses for all 4 speaker probes following MEI. Participant A showed the weakest speaker accuracy following MEI, with his first 2 probe sessions showing 12 correct responses for both pure and impure tacts and the last 2 showing 10 correct responses for the pure tact and 8 correct responses for the impure tact. For Participant D, impure tact responses were slightly weaker than the pure tact responses, while there was little difference in the pure and impure responding for the other participants.

DISCUSSION

The data show the emergence of joint stimulus control across listener and speaker repertoires for children for whom this control was not present prior to the MEI experiences. Participant A showed weaker control in his probes for the novel Set 3 pictures, but this may have been a function of the lack of reinforcement in the probe trials. Indeed, Participant D showed weaker responses for the impure tacts after having received 40 probes for the pointing and the pure tact responses—this difference may also be attributable to extinction effects. It may be wise to insert opportunities to respond to previously mastered but unrelated stimuli with reinforcement for correct responses between probe trials to avoid response extinction for some children.

We did not test for the other side of naming that requires the child to go from speaker to listener. The research of Lowe et al. (2002) suggests that this component of naming is evoked commonly for typically developing children once the tact is acquired. Still we need to investigate this component also. It is possible that the bi-directionality in naming may involve different stages; that is, one may master listener-to-speaker but not emit speaker-to-listener or vice versa and that each of these may be separate stages, at least for some children.

We suggest that naming, and each of its bidirectional components, is a critical developmental milestone in the acquisition of more complex verbal repertoires by children. Barnes-Holmes et al. (2001) suggested that behavior is not truly verbal until these kinds of frames are present. We suggest that the higher order operant or frame is actually a progression in verbal repertoires and that the prerequisite components are simply not yet under the joint control of stimuli. The acquisition of the naming repertoire makes it possible for the child to acquire new tacts and new textual responses simply by exposure as a listener. Perhaps the “listener repertoire is observed by the speaker repertoire,” so to speak, and that observation provides the wherewithal for the individual to emit a speaker response without direct instruction. The speaker and listener are operating within the same skin to use Skinner's (1957) terminology. However, until a particular instructional history provides joint stimulus control across the speaker and listener responses, novel use of speaker responding resulting from listener exposure may not be possible (Hayes, Gifford, Wilson, Barnes-Holmes, & Healy, 2001; Skinner, 1957, p. 92; Skinner, 1989). If typically developing children have certain prerequisites, they may require only a brief set of experiences to develop single or bidirectional joint stimulus control between speaker and listener. We are currently investigating this.

While typically developing children may acquire these components of naming incidentally, children with language delays are likely to require intensive direct instruction. In our application of these procedure to over two dozen children in CABAS® schools, we have found that some children require MEI with several subsets of pictures or objects before the joint stimulus control emerges. We probably should have done two sets of MEI instruction in the present experiment; nevertheless, with only a single set of MEI our children showed remarkable results. When the desired effects were not forthcoming in our application of these procedures with children in several schools, we found that if we returned to instruction that provided fluent basic literacy using procedures that we described in Greer et al. (2003b), those students then acquired joint stimulus control after a reapplication of the MEI across speaker and listener responding. These latter findings suggest that basic listener fluency is a key prerequisite repertoire needed to maximize the effectiveness of the procedure described herein. One may need to insure that the point-to listener response is mastered because the listener repertoire must be present.

What's interesting about these findings and the related findings from Nuzzolo and Greer (2004), Greer et al. (2003), and Greer, Yuan, & Gautreaux (2003) is that they point to environmental histories that result in “generative” verbal behavior, heretofore attributed solely to neurological capabilities by some theorists (Pinker, 1999). The work of Lowe et al. (2002) demonstrated the phenomenon of naming. And, like self-talk involving conversational units (Donley & Greer, 1993; Lodhi & Greer, 1989), naming is a kind of speaker-as-own-listener type of responding. Speaker-as-own-listener responding requires joint stimulus control across the speaker and listener repertoires. The role of the listener in verbal behavior, as it is related to the speaker repertoire, seems to be a prerequisite in the evolution of more complex verbal repertoires such as self-editing and problem solving. The identification of such phenomena as naming, relational frames, or types of relational frames such as stimulus equivalence in typically developing children is an important step forward. However, when we locate children who do not have these repertoires, and we can induce them through experimental interventions, we can not only provide the means to move a child through more advanced repertoires of verbal behavior, but we simultaneously test for the possible sources for key verbal stages of development, including higher order “controlling relations.” Skinner wrote:

The origin of most forms of [verbal] responses will probably always remain obscure, but if we can explain the beginnings of even the most rudimentary verbal environment, the well-established processes of linguistic change will explain the multiplication of verbal forms and the creation of new controlling relations. (Skinner, 1957, p. 469)

Perhaps, we have identified one way to untangle some of those formerly obscure origins, thanks to the opportunity to work with individuals who did not have the rudimentary forms, or more complex types of controlling relations, together with the development of procedures to test the origins of new controlling relations. While it does not necessarily hold that typically developing children acquire these new controlling relations through incidental experiences in the same manner as the children we have studied, it does seem to be a more parsimonious explanation than the attribution of the generative responses to neurological capabilities independent of experiences. Armed with the identification of higher-order verbal operants or relational frames, the analysis of verbal behavior may come to identify key verbal behavior stages. As we identify the instructional histories that lead to the key stages, we can test for the presence or absence of particular instructional histories to determine how and if they relate to more complex verbal capabilities. Through such a process verbal development could be related to experiences rather than age alone. This could result in empirically based stages of verbal development that are the foundations of complex human behavior.

Footnotes

R. Douglas Greer, Lauren Stolfi, Mapy Chavez-Brown, and Celestina Rivera-Valdes, of Teachers College and The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University. We thank the staff, students, and families of The Fred S. Keller School for their participation and continued support.

REFERENCES

- Bahadorian A.J. The effect of the learn unit on student's performance in two university courses. Columbia University; 2000. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y, Cullinan V. Relational frame theory and Skinner's Verbal Behavior. The Behavior Analyst. 2001;23:69–84. doi: 10.1007/BF03392000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker W. Direct instruction: A twenty-year review. In: West R, Hamerlynck L, editors. Design for educational excellence: The legacy of B. F. Skinner. Longmont, CO: Sopris West; 1992. pp. 71–112. [Google Scholar]

- Catania A. C. Learning. (4th ed.) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Donley C. R, Greer R. D. Setting events controlling social verbal exchanges between students with developmental delays. Journal of Behavioral Education. 1993;3(4):387–401. [Google Scholar]

- Emurian H. H, Hu X, Wang J, Durham D. Learning JAVA: A programmed instruction approach using applets. Computers in Human Behavior. 2000;16:395–42. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Fields L, Reeve K. F, Mateneja P, Varelas A, Belanich J, Fitzer A, Shannon K. The formation of a generalized categorization repertoire: Effects of training with multiple domains, samples, and comparisons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2003;78:291–31. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-291. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D. Designing teaching strategies: An applied behavior analysis systems approach. New York: Academic Press; 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, Chavez-Brown M, Nirgudkar A, Stolfi L, Rivera-Valdes July 2003. The effects of a procedure to teach fluent listener responses to students with autism and changes in the numbers of learn units students required to meet instructional objectives. Paper presented at the First Congress of the European Association for Behavior Analysis, Parma, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, Keohane D. The evolution of verbal behavior. 2004. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, Keohane D. D, Healey O. Quality and applied behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2002;2002;3(1) [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, McCorkle N. CABAS® international curriculum and inventory of repertoires from pre-school through kindergarten. Yonkers, NY: CABAS® and the Fred S. Keller School; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, McDonough S. Is the learn-unit the fundamental measure of pedagogy. The Behavior Analyst. 1999;20:5–16. doi: 10.1007/BF03391973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, Nirgudkar A, Park H. 2003b. The effect of multiple exemplar instruction on the transformation of mand and tact functions. Paper Presented at the International Conference of the Association for Behavior Analysis, San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, Yaun L, Gautreaux G. Novel Dictation and Intraverbal Responses as a Function of a Multiple Exemplar Instructional History. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2005;21:99–116. doi: 10.1007/BF03393012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C, Gifford E. V, Wilson K. G, Barnes-Holmes D, Healy O. Derived relational responding as learned behavior. In: Hayes S. C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, editors. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001. pp. 21–49. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Horne P. J, Lowe C. F. On the origins of naming and other symbolic behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1996;65:185–241. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1996.65-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner R. D, Baer D. M. Multiple-probe technique: A variation on the multiple baseline. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1978;11:189–196. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodhi S, Greer R.D. The speaker as listener. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1989;51:353–360. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1989.51-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe C. F, Horne P. J, Harris D. S, Randle V. R. L. Naming and categorization in young children: Vocal tact training. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;78:527–549. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzolo-Gomez R, Greer R. D. Emergence of Untaught Mands or Tacts with Novel Adjective-Object Pairs as a Function of Instructional History. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2004;24:30–47. doi: 10.1007/BF03392995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinker S. Words and rules. New York: Perennial; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B. F. The behavior of the listener. In: Hayes S. C, editor. Rule-governed behavior: Cognition, contingencies and instructional control. New York: Plenum; 1989. pp. 85–96. (Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Verbal Behavior. Acton, MA: Copley Publishing Group; 1957, 1992. [Google Scholar]