Abstract

We tested the effect of multiple exemplar instruction (MEI) on acquisition of joint spelling responses, vocal to written and vice versa, for three sets of five words by four kindergarteners with language delays using a delayed multiple probe design. First, students were taught to spell Set 1 as either vocal or written responses (two vocal and two written) and probed on untaught responses. Next students were taught Set 2 using MEI (i.e., alternating responses) and again probed untaught responses for Set 1. Finally, Set 3 was taught in a single response and students were probed on untaught responses. Two students spelled none of Set 1 untaught responses before MEI, while two spelled the words at 60% accuracy or 10% accuracy. After MEI on Set 2, all students spelled untaught responses for Set 1 at 80% to 100% accuracy and Set 3 at 80% to 100% accuracy. The MEI resulted in joint stimulus function such that formerly independent responses came under the same stimulus control. We replicated these results with four other kindergartners with autism who performed academically above their typically developing peers. The results are discussed in terms of Skinner's treatment of the independence of the two verbal operants.

Keywords: spelling, multiple exemplar instruction, independence of verbal operants, transformation of function

According to several experiments with young children and individuals with developmental disabilities, the same word or form of verbal behavior is often a component of different verbal operants which must be separately learned; for example, learning a form as a mand did not result in the use of the form in a tact function without direct instruction (Lamarre & Holland, 1985; Ross & Greer, 2003; Stafford, Sundberg, & Braam, 1988; Tsiouri, & Greer, 2003; Twyman, 1996; Williams & Greer, 1993). Other verbal forms also have independent functions, at least initially. Moreover, Skinner describes also how the same response occurs in different media; that is, a word may occur in the “media” of speaking or writing. After hearing someone say a word, one may write the word (i.e., dictation) or say the letters of the word (i.e., respond intraverbally as a kind of dictation response). The writing of the letters and the saying of the letters are two different behaviors. When children learn to spell they must learn to respond with two different spelling responses—spoken and written responses. While Skinner did not directly address spelling, he did describe the independence of vocal and written responses following a spoken stimulus. It would appear that one of the earliest occasions in which these repertoires can be analyzed is in the formative stages when children are learning to spell.

. . . Speaking and writing are obviously different kinds of behavior…. Where we could paraphrase “the same word used in different ways” as “the same response used in different operants,” here we must attempt to bridge the gap between the spoken and written behavior [italics added] either by pointing to the occasions upon which the behaviors occur or among the effects which they have upon the listener and the reader. But common controlling variables acting either prior to the behavior in the stimulating occasion or after the behavior in the event called reinforcement, will not get from one form of the response to another. The two forms of the behavior must be separately conditioned (Skinner, 1957, p.191).

Skinner goes on to state that every literate individual eventually acquires a repertoire of responding to a spoken stimulus with either a written or vocal response after learning only one (p. 191). When children first learn to spell in the separate responses of writing and saying, the two are independent; however, at some point individuals learn to emit the untaught operant when taught a single response (e.g., writing the word after having learned to spell the word vocally or vice versa). Children at some point can emit either a written or vocal spelling response after learning only one response. What experiences bridge the gap? The basic science of behavior requires an explanation for this and related generative verbal behavior, and the utility of such an explanation for applications to education is apparent.

Experimental analyses of instructional histories offer possible explanations for generative verbal behavior. Multiple exemplar instruction (also termed general case instruction) is an instructional operation from the research literature associated with teaching concepts or abstractions as essential stimulus control. Positive exemplars of a subset of a category of stimuli are taught across presentations that include a range of irrelevant properties such that the critical or essential attribute of the classification is identified in response forms not directly taught. For example, teaching the critical attributes of a range of mammals leads to the identification of animals not encountered before as mammals. Englemann and his colleagues (Becker, 1992; Engelmann & Carnine, 1982) applied the multiple exemplar strategy to a range of curricula from instruction in mathematics to reading. Several experiments showed generalization and maintenance were significantly stronger as a result of multiple exemplar instruction including basic discriminations by young children (Granzin & Carnine, 1977), the use of vending machines by individuals with significant developmental delays (Sprague & Horner, 1984), and the identification of complex auditory stimuli by high school students (Greer & Lundquist, 1976), a finding that was replicated with pigeons by Porter and Neuringer (1985). In these and other studies (Young, Krantz, McClannahan, & Polson, 1994) the same response was taught to stimuli that vary widely but have certain stimulus characteristics that come to control a single response. Fields et al. (2003) found that a novel categorization repertoire emerged as a result of instruction across multiple domains, samples, and comparisons. All of these applications of multiple exemplar instruction concerned aspects of stimulus control. It is also possible that the manipulation of initially independent response topographies with the same stimulus may generate the joint stimulus control such that a single stimulus can evoke both responses—a different application of multiple exemplar instruction.

The objective of the present experiment was to test whether teaching joint stimulus control across written and spoken spelling forms as a common response class for a sample or subset of words, using multiple exemplar instructional tactics, would result in the emission of untaught response topographies for novel words. If the experience resulted in a joint control of stimulus function across the two operant classes, then the students could be taught new words in one response form and produce the other response form without instruction as a result of the multiple exemplar experience with a subset of words. Moreover, the identification of the source of this form of generative behavior would be a contribution to the fundamental science of verbal behavior.

The determination of a functional relationship between instructional histories composed of multiple exemplar experiences and the emission of different verbal operants without direct instruction calls for: (a) the selection of individuals without particular instructional histories for whom the two operants are independent, and (b) an experimental analysis involving the manipulation of multiple exemplar experiences. Next, the emergence of the untaught operant must be shown to be a direct function of the multiple exemplar instructional experience using a design logic that permits the identification of functional relationships for responses that are not reversible. The following experiment and the subsequent direct replication tested the relationship between a multiple exemplar instructional history and the production of untaught spelling responses with students for whom the responses were initially independent.

EXPERIMENT 1

Method

Participants

Four kindergarten students with beginning writing and reading repertoires participated in the experiment (i.e., formation of letters and transcription, and minimal textual responses). We taught 2 of the 4 students minimal vocal spelling responses during the period immediately before the experiment, while two students had no instructional history with spelling dictation except for the repertoire of emitting dictation to spoken letters. None of the students demonstrated joint stimulus control of spelling across written and spoken functions, nor could they spell any of the words used in the experiment in either topography, as determined in pre-experimental probes, continuous measurement of all instructional responses, and comprehensive assessments of the students' repertoires (Greer & McCorkle, 2002). Prior to the experiment, we taught all of the students the prerequisite writing skills (i.e., formation of letters and transcription) and textual responding that were component skills for spelling (i.e., the students could textually respond to the words that they were to spell). The consequence used for reinforcement was based on the extensive instructional experience with each student. Consequences that were used in reinforcement operations ranged from generalized reinforcers such as praise or tokens to edible reinforcement. Each student is described individually in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of Participants in Experiment 1.

| Participants | Repertoires taught prior to the experiment | Chronological age, diagnoses and relevant missing repertoires |

| Student A | Write dictated letters A-Z, and textually respond, vocally spell 4 words, textually respond to 15 words, and words he was to spell | Five-year-old male, Stanford Binet verbal IQ 59, speech impairment and language delays, transformation of stimulus function across speaking and writing missing |

| Student B | Write dictated letters A-Z and textually respond, vocally spell 5 words, textually respond to 150 words, and words he was to spell | Five-year-old male, Stanford Binet verbal IQ 71, speech impairment and language delays, transformation of stimulus function across speaking and writing missing |

| Student T | Vocal mand and tact with related autoclitics, write dictated letters A-Z and textually respond to 200 words, and words she was to spell | Five-year-old female, Stanford Binet composite score of 60, autism and mental retardation, no spelling instruction, transformation of stimulus function across speaking and writing missing |

| Student J | Write dictated letters A-Z and textually respond, textually to respond to 75 words, and words he was to spell | Six-year-old male, Stanford Binet verbal IQ 76, autism and speech impairment, no spelling instruction, transformation of stimulus function across speaking and writing missing |

Setting

The experiment and pre-experimental instruction for the students occurred in classrooms that applied behavior analysis strategies and tactics to all of the instruction received by the students (Greer, 2002). All of the students' responses to instruction in all of their 20 to 40 curricular goals were measured and the accuracy of the measurement monitored on a continual basis. The classrooms had one teacher and two teacher assistants and eight students. Data were collected in the classroom as a part of normal instructional procedures. Thus, the data were collected in a one-to-one tutorial setting for the target students as other students in the classroom received individualized instruction or worked independently. Students were accustomed to receiving instruction individually while other instruction occurred. Probe trials or learn units were presented only when the students were attending. No more than two sessions were conducted in a single day. Students were assigned to the classroom on the basis of their diagnoses and their minimal verbal behavior repertoires. The school was a public school that offered countywide specialized services and was located in the suburbs of a large metropolitan area.

Description of Responses

The dependent variables consisted of untaught spelling responses in both written and spoken forms. The target behaviors were written and spoken responses to vocal dictation by the teacher. When the student was to say the letters of the word the teacher said, “Spell _____,” and when the student was to write the word the teacher said, “Write ______.” Written responses that were consistent with common spelling were counted as correct (i.e., the student's printed response showed correspondence to the conventional spelling of the dictated word after the teacher said, “Write cat”). Spoken spelling responses showed point-to-point correspondence to conventional spelling in vocal form (i.e., the student vocally says “c-a-t” after the teacher said, “Say cat”). Written responses were done on large and lined paper used for elementary school age children's writing instruction. Skinner (1957) characterized the spoken response as an intraverbal function and the written response as a dictation function. Each involves different response topography to the same spoken stimulus.

Each student was assigned three sets of five words. The three sets of words for each student are shown in Table 2. The students could not spell the word in either response topography preceding baseline instruction. The words were two-, three-, or four-letter simple words from a list of the 100 most frequently used English words. There were different words associated with the three sets for each student. The choice was based on the particular student's experience or lack of experience with spelling and textually responding (i.e., the textual response for the words had to be taught to the student or in the student's repertoire in order for the words to be selected for inclusion).

Table 2.

Word Sets for Students A, B, J and T.

| Student | Set 1 Words | Set 2 Words | Set 3 Words |

| A | fun, ear, shoe, boat, what | two, me, red, star, coat | up, can, big, man, book |

| B | toy, pen, fun, hall, us | to, car, nice, we, she | this, and, big, me, get |

| J | out, me, yes, hat, foot | play, six, ran, tree, we | it, ten, help, ball, cake |

| T | dad, boy, who, girl, jump | token, good, work, cat, bus | the, run, fish, play, what |

Data Collection

The primary data collector and the independent observer were graduate-level behavior analyst teachers who had extensive training and frequent calibration in recording student responses to learn units for teaching responses (see Greer & McDonough, 1999, for the research literature identifying the learn unit as a predictor of student learning) and probe trial conditions for testing untaught or generalization responses. Data were collected in pre-experimental probe trials on untaught written and spoken spelling responses that served as the dependent variable (Set 1 and Set 3 words).

Data were collected also on the responses of the students to learn-unit instruction for both written and spoken topographies for Set 2 words, as well as the taught topographies for Set 1 and Set 3 words—the process leading to the implementation of the independent variable. Therefore, two data points are shown in Figure 2 for the multiple exemplar phases. We measured the accuracy of learn-unit presentations as indices of the reliability of implementation of the independent variable (achievement of criterion for the multiple exemplar instruction) for Set 2 words and the baseline learn-unit instruction in single topographies with Set 1 words and the post treatment instruction in a single topography for Set 3 words. Correct responses were recorded using pencil and paper as pluses (+) and incorrect responses and no responses were recorded as minuses (−). The incorrect vocal or written responses were those that had the wrong letter in the sequence (e.g., “Tat” for “Cat”), omissions or additions of incorrect letters, or no response in the topography presented under probe trial conditions. Probe trials consisted of no reinforcement for correct responses and no corrections to the students' responses to untaught spelling response forms.

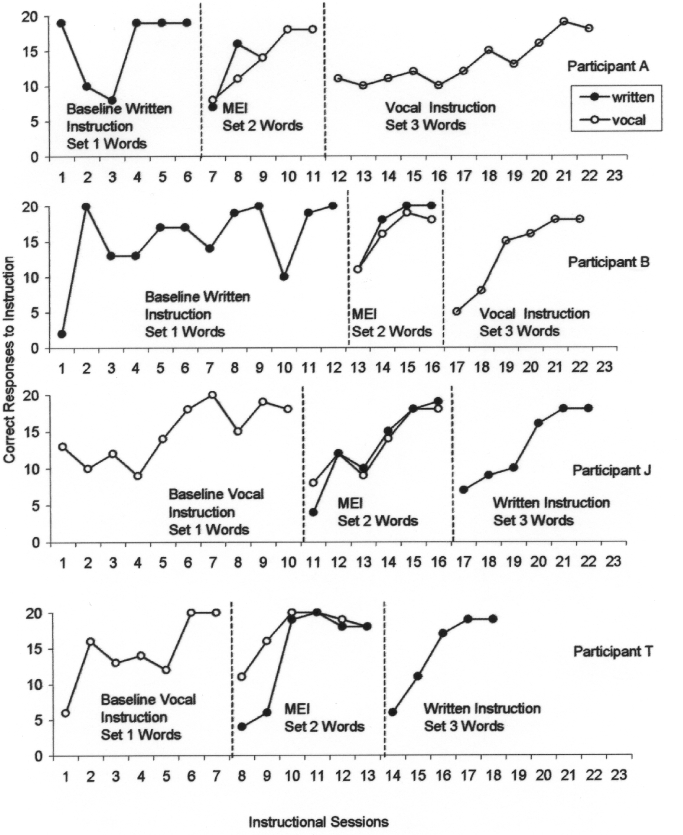

Figure 2.

The 4 students' correct responses to instruction in single response functions for Set 1 and Set 3 words and their correct responses to multiple exemplar instruction across the two response functions for Set 2 words for Experiment 1.

Instructional trials or learn units consisted of corrections to incorrect responses that required the student to provide a corrected response (not reinforced) for incorrect responses, and the delivery of consequences that were known to reinforce acquisition of other discriminations for the students' correct responses. Learn units began when the child was attending to the teacher per the requirements of a learn unit. This was followed by the presentation of the spoken word by the teacher. The students had 3 s to begin their response to the teacher's stimulus presentation. Responses that occurred after 3 s were recorded as errors. Incorrect responses resulted in the teacher providing the correct response followed by the student repeating the correct response. Correct responses resulted in a reinforcement operation using reinforcers that were know to be effective throughout the child's instructional day. At the conclusion of the learn unit, the next learn unit was presented. No other spelling instruction occurred in the class for the duration of the experiment. The details of the data collection procedures are described below.

Pre-Experimental Probe Conditions

The teacher presented each of the three sets of five words under probe trial conditions prior to the baseline (four presentations for each of the five words in 20-trial sessions for each of the three sets of words, respectively). The probes consisted of one session of 20 trials for each of the responses—written or spoken. The child had to be attending to the teacher for a probe trial to occur. There were 20 consecutive trials for spoken responses and 20 consecutive trials for written responses for each of the three sets of words—a total of 40 probe trials in one sitting. None of the students emitted any correct responses in either written or spoken response forms to any of the three sets of words during the pre-experimental probe trials. If students were inattentive prior to a probe presentation, presentations of material known to the child were made and reinforced to insure attention to the non-reinforced probe trial presentations.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable consisted of correct or incorrect responses to probe trials for untaught response topographies, written or spoken, according to the different phases of the experimental design. Probe trial responses received no reinforcement or corrections.

Prior to the baseline probe for Set 1 words, the students were taught one of the two response forms (i.e., say or write) to the spoken words using learn units. The teacher said, “spell,” when the student was to say the letters, and “write,” when the student was to write the letters. Correct and incorrect responses were recorded for these responses as described and are displayed in Figure 1.

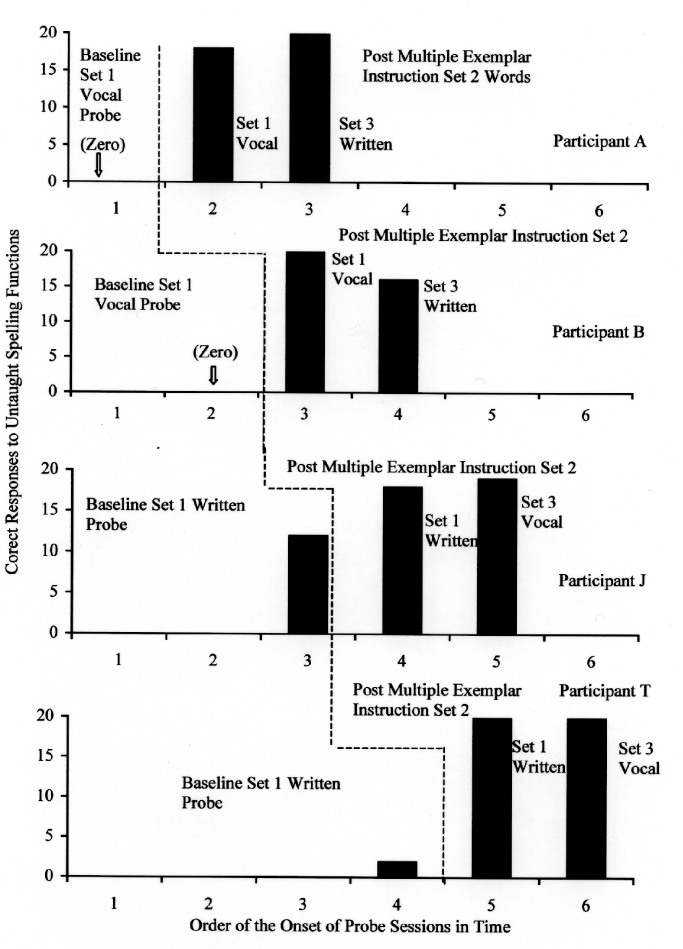

Figure 1.

Correct responses to untaught spelling responses by the four students following: (a) baseline instruction in untaught spelling responses, and (b) the students' responses to untaught responses for Set 1 and Set 3 words following multiple exemplar instruction in Set 2 words for Experiment 1.

Independent Variable

The independent variable consisted learn-unit presentations of the two different spelling functions on Set 2 words—both written and spoken functions. The learn-unit presentations consisted of teacher instructions to spell words that included presentations to which the student attended and there was a response opportunity, a reinforcement operation for correct responses, or a correction operation for incorrect responses. In the correction response, the teacher provided the correct response and the student repeated or wrote, depending on the presentation condition, the correct response after the teacher said “spell _____” for the spoken response, or “write _____” for the written response. Instructional presentations included all of the components identified in the research on learn units (Albers & Greer, 1991; Emurian, Hu, Wang, & Durham, 2000; Greer & McDonough, 1999; Ingham & Greer, 1992; Lamm & Greer, 1991; Selinske, Greer, & Lodhi, 1991). Corrected responses were not reinforced. Correct and incorrect responses were recorded as described above for the probe trial conditions. These data are displayed in Figure 2.

Interobserver Agreement

Independent observers recorded correct and incorrect responses to probe conditions for both spoken and written responses in 30% of the pre-experimental probe sessions. Independent observers were used for 50% of the sessions for the spoken responses and 50% of the written responses that served as the dependent variable (i.e., untaught responses to Set 1 and Set 3 words). The percentage of agreement for the dependent variable, probe trials, across all conditions was 100%, and the percentage of agreement for responses to learn-unit instruction was 100%.

Design

The design was a multiple baseline probe design across students in which each set of words was probed preceding and following each of the training conditions (i.e., untaught responses before and after instruction in a sample subset using multiple exemplar procedures) staggered by time. Sessions were time lagged across subjects using multiple baseline logic (Horner & Baer, 1978) to control for maturation and history. That is, each successive participant was probed in the baseline phase consistent with the prior participant's completion of the post multiple exemplar instruction probe (see Figures 1 and 3 where the x axis represents the sequence of probes in time). Probe sessions in which there was no data represent periods of time before the participants were exposed to baseline conditions consistent with the standard protocol for multiple baseline probe designs. The order of response type, written or spoken, was counterbalanced across participants, such that participants who received written response instruction for Set 1 words received vocal response instruction for Set 3 words and vice versa.

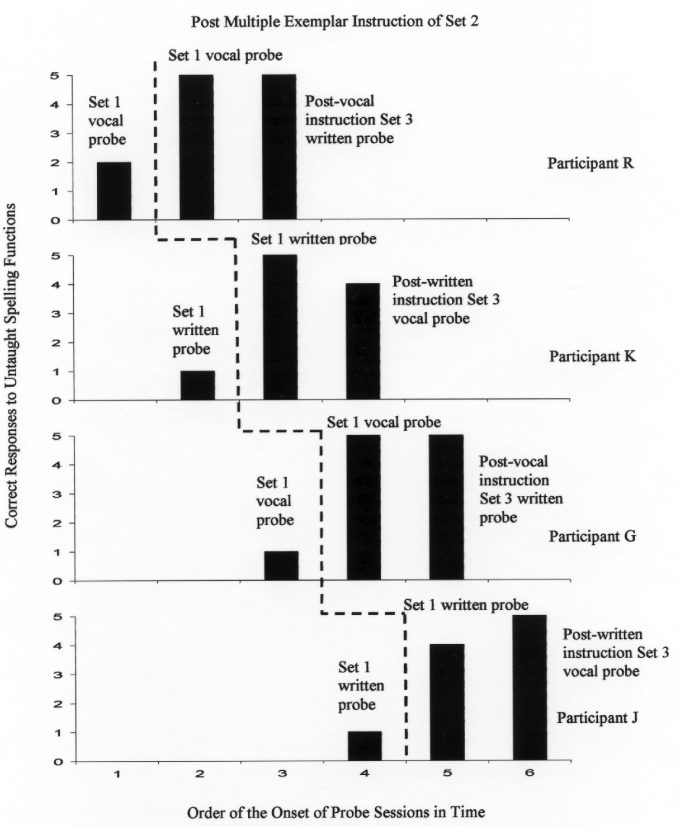

Figure 3.

Correct responses to untaught spelling responses by the four students in Experiment 2 following: (a) baseline instruction in a one type of responding, and (b) the students' responses to untaught responses for Set 1 and Set 3 words following multiple exemplar instruction in Set 2 words.

The order of procedures was as follows. (1) Pre-experimental probes of both responses to all three sets of words were conducted and showed that the children could not spell any of the words as spoken or written responses. (2) After the pre-experimental probes, the children were taught mastery of either spoken or written responses for Set 1 words in 20 learn-unit sessions according to the counterbalance scheme. They were then probed on untaught Set 1 responses. (3) Next, the children were taught Set 2 words for both vocal and written responses using multiple exemplar instruction as the treatment. That is, they received 20 learn units for each response and the learn units for the different responses were rotated (i.e., a written response followed by a vocal response for the same word). The orders of presentation of written or vocal learn units were rotated. (4) Subsequently, the students were again probed on the untaught responses to Set 1 words. (5) Finally, the students were taught Set 3 words in one response in 20 learn-unit sessions until mastery and then probed on the untaught responses to these novel words. Detail for each of these steps follows.

Baseline instruction and probes. Prior to the baseline probe, students were taught one of two topographies for Set 1 words, either the vocal spelling or the written spelling depending on the counterbalance scheme, to a minimum criterion of 90% correct responses for two successive 20-learn-unit sessions. Students A and B were taught written responses and probed after the training for vocal responses, while Students T and J were taught vocal responses and probed after the training for written responses. Following the baseline probe, the multiple exemplar instruction on Set 2 words was begun.

Multiple exemplar instructional treatment. During multiple exemplar instruction, the students were taught both written and spoken responses for Set 2 words in an alternating fashion, using learn units as described above, until each topography met a criterion of 90% or better for two successive sessions. Instruction consisted of 20 learn-unit sessions, but sessions alternated the opportunity to spell in written topographies with the opportunity to spell in spoken topographies. The student was taught in alternating fashion to spell a word in one topography then the other, until criterion was achieved for both functions. Each of the five words was first presented as a learn unit in one topography then presented as a learn unit to spell the word using the other topography. The order of the presentations for written responses or spoken responses was rotated. In cases where one of the response topography was mastered prior to the other, the mastered topography continued to be rotated with the form not yet mastered until criterion was achieved for the latter. That is, once a student met criterion with particular response topography, the correct response was treated as a part of the instructional antecedent for responding to the response not yet mastered (i.e., the student continued to emit the mastered response as a prerequisite to responding to the response not yet mastered).

While the instructional sessions consisted of 10 learn units in each response topography resulting in sessions of 20 learn-units, the data were blocked in 20 learn-unit sessions for each topography respectively for the visual displays (Figure 2). The Set 2 words were the only words taught using the multiple exemplar procedure and these words were not used in any other part of the experiment.

Post multiple exemplar instruction on Set 3 words. The students were taught to spell the Set 3 words in a single response topography using learn units to a minimum of 90% accuracy for two consecutive sessions. However, the specific topography taught was different from the topography taught for Set 1 words according to the counterbalance scheme.

Results and Discussion

The students were unable to spell any of the words in either function prior to the experiment. Figure 1 shows that following baseline training in the written response form, Participants A and B did not respond correctly to any of the untaught vocal responses. Participant J emitted 12 correct responses (60%) to the written probes after mastering the vocal response forms, and Participant T emitted two correct vocal responses (10%) after being taught the written form.

After the multiple-exemplar training on Set 2 words, 20-trial probe sessions showed that Participant A emitted 18 correct responses (90%) to the untaught vocal response forms for Set 1 words, and Participant B emitted 20 correct responses (100%) to the untaught vocal forms for Set 1 words. After multiple exemplar instruction on Set 2 words, Participant J emitted 18 correct responses (90%), or 6 more correct responses than he had emitted in the baseline probe for the untaught written forms for Set 1 words. After the multiple exemplar instruction for Set 2 words, Participant T emitted 20 correct responses (100%) or 18 more correct responses than he had emitted in the baseline probe on the untaught written response forms for Set 1 words.

In the final training phase, in which the students were taught one topography for Set 3 words and probed in 20-trial sessions on the untaught Set 3 forms, Participant A emitted 20 correct responses (100%) on the untaught written response forms, and Participant B emitted 16 correct responses (80%) on the untaught written forms. Participant J emitted 19 correct responses (95%) on the untaught vocal forms, and Participant T emitted 20 correct responses (100%)n on the untaught vocal forms.

Figure 2 shows the instruction needed to meet the acquisition criterion for single response topographies for Set 1 and Set 3 words, and the instruction needed to meet the acquisition criterion for multiple exemplar training for Set two words across the two response topographies. The multiple exemplar instruction produced “joint control” over the different behaviors. The term transformation might apply since the control of the stimulus, the spoken word, was transformed from control of a single topography to joint control over two topographies (Dougher, Perkins, Greenway, Koons, & Chiasson, 2002).

We conducted a systematic replication of the experiment at another site three months following the initial experiment to test the reliability findings and the generality of the findings to children with the academic repertoires of typically developing children.

EXPERIMENT 2: SYSTEMATIC REPLICATION

Method

All of the procedures were the same as those used in Experiment 1 for this experiment with the following exceptions. In the replication, probes for the untaught relations were limited to five probe trials (one probe trial for each of the five words taught in each set instead of the 20-trial probe sessions used in Experiment 1). The participants selected for the experiment were students in a behavior analysis school replication site in Ireland; however, unlike the participants in Experiment 1, the participants in Experiment 2 performed at or above grade level extending the test of the procedure to students with more advanced repertoires—repertoires that are characteristic of typically developing children. For this experiment, the words selected for the experiment included two syllable words. Each of these differences is described below.

Participants

Four Kindergarten male students with diagnoses of autism served as participants in the second experiment. All of the five-year-old students were taught to take dictation for the letters of the alphabet in the months preceding the experiment. They were taught also to textually respond to letters of the alphabet and to spell other words vocally in the same time frame. Each student read at or above first grade level. All of the students were taught to read and use functional vocal communication in the two years that they had been in the behavioral school for the education of students with autism. While all of the students had some vocal verbal responses when they entered the school program, most of the vocal verbal behavior was not functional. After approximately 18 months in the school, all four students were mainstreamed in regular education schools in Ireland for portions of their school week and all performed academically at or above the grade level of their non-categorized peers. All of the children could textually respond to the words used in the experiment. Each student is described in detail in Table 3.

Table 3.

Description of Participants in Experiment 2.

| Participants | Repertoires taught prior to the experiment | Chronological age, diagnoses and relevant missing repertoires |

| Student R | Functional mands and tacts with relevant autoclitics, read and other academic skills at or above first grade level, self-management skills, mainstreamed for portions of the day, spell words vocally, dictation for letters of the alphabet | Five-year-old male, autism, school entry Stanford Binet composite IQ 76, score at outset of experiment 130, no transformation of stimulus control for spelling from written to to spoken or vice versa |

| Student K | Functional mands and tacts with relevant autoclitics, read and and other academic skills at or above first grade level, self-management skills, mainstreamed for portions of the day, spell words vocally, dictation for letters of the alphabet | Five-year-old male, IQ scores not available, autism, no transformation of stimulus control for spelling from written to spoken or vice versa |

| Student G | Functional mands and tacts with relevant autoclitics, read and other academic skills at or above grade level, self-management skills, mainstreamed for portions of the day, spell words vocally, dictation for letters of the alphabet | Five-year-old male, autism, IQ scores not available, no transformation of stimulus control for spelling from written to spoken or vice versa |

| Student J | Functional mands and tacts with relevant autoclitics, read and other academic skills at or above grade level, self-management skills, mainstreamed for portions of the day, spell words vocally, dictation for letters of the alphabet | Five-year-old male, autism, IQ scores not available, no transformation of stimulus control for spelling from written to spoken or vice versa |

Word Sets and Probe Conditions

The words taught to each student are shown in Table 4 and the students emitted no correct responses to pre-experimental probe conditions. Pre-experimental and post-training probes consisted of one trial for each of the words or a total of five probe trials for each probe session.

Table 4.

Word Sets for Students R, S, K and G.

| Student | Set 1 Words | Set 2 Words | Set 3 Words |

| R | people, because, morning, circle, question | would, answer, nothing, women, friend | country, family, button, breakfast, minute |

| S | count, family, clothes, minute, corner | follow, because, behind, please, different | people, across, beside, middle, laugh |

| K | nothing, computer, minute, second | country, question, before garden, quiet, because | morning, family, friend, answer, clothes |

| G | back, about, work, could, door | some, more, from, many, letter | make, show, thing, must, wash |

Interobserver Agreement

Interobserver agreement was collected for all vocal responses and written responses in the probe conditions for untaught topographies—the dependent variable. The Interscorer agreement for written responses was 100% and the interobserver agreement for vocal responses was 100%. Interobserver agreement was obtained for 50% of the learn-unit instructional sessions and it was 100%.

Results and Discussion

The results of the probes for untaught responses, following instruction to criterion on a single response, are shown in Figure 3. In the probes for untaught topographies, Participant R emitted two correct vocal responses to the Set 1 words following written instruction. Following the MEI for Set 2 words, he emitted correct vocal responses to all Set 1 words and correct written responses to all Set 3 words that were taught in an intraverbal function only. Student K emitted one correct response to written probes for Set 1 words following vocal instruction for those words. After the MEI for Set 2 words, he emitted correct written responses to all of Set 1 words and four correct responses to vocal probes for Set 3 words, after having been taught Set 3 words in a written form. Student G emitted one correct vocal response to Set 1 words after being taught written responses only. Following MEI on Set 2 words he emitted correct vocal responses to all Set 1 words and correct written responses to all Set 3 words after learning them as vocal responses only. Student J emitted one correct written response to Set 1 words after learning them in a vocal function. Following the MEI in Set 2 words he emitted four correct written responses to the Set 1 words. He emitted five correct responses (100%) to Set 3 words vocally following instruction in written responses only. One of the students emitted two correct responses (40%) in untaught functions and three students emitted one correct response (20%) in their baseline probes. All students demonstrated untaught responses at 80% to 100% accuracy for Set 1 and Set 3 words following MEI on Set 2 words. The data for the learn-unit sessions for teaching single response topographies for Set 1 and Set 3 words and the multiple exemplar instruction for Set 2 were similar to those in the first experiment and are not reported for brevity's sake; they are available from the first author.

The second experiment replicated the findings of Experiment 1 and extended the effects to students who were performing at, or above, the academic grade level of typically developing children. The results showed that the spoken stimulus, which initially controlled only the topographies that were directly taught, came to have joint stimulus control over untaught topographies following the multiple exemplar instruction with a subset of words. We limited the probe sessions to five trials, one for each word, in the replication experiment to avoid possible extinction effects, although no such effects were found in the first experiment. Also, few basic science studies require probe tests that require four responses tests as we did in Experiment 1.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Research studies that embrace both the conceptual underpinnings and applications of Skinner's verbal behavior have provided useful tactics for teaching children functional speaking, writing, and verbally mediated repertoires (Ingham & Greer, 1992, Greer, 2002; Greer & Ross, in press; Lodhi & Greer, 1989; Marsico, 1999; Ross & Greer, 2003; Stafford et al., 1988; Tsiouri & Greer, 2003; Williams & Greer, 1993). These and other applications of verbal behavior have also contributed to the basic science of behavior. If the effects of multiple exemplar instruction, like those we report here, extend to the formation of other generative verbal behavior, the contributions of Skinner's verbal behavior to a science of language function and its applications will be enhanced significantly (Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, & Cullinan, 2000; Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001; Hayes, Fox, Gifford, & Wilson, 2001).

Research in verbal behavior has affirmed Skinner's theory on the independence of some verbal operants, such as the independence of mands and tacts at least at certain instructional stages (Lamarre & Holland, 1985, Williams & Greer, 1993; Twyman, 1996). While these repertoires are independent early on, it is clear that joint control occurs for most children rapidly. Perhaps the mechanisms for the development of joint control are multiple exemplar experiences. Joint control of stimulus function across the response topographies of listener (e.g., match, point) to speaker or vice versa (e.g., tact, and intraverbal responses) is not present for young children and individuals with developmental disabilities. For example, teaching a child to match colors does not result in repertoires of pointing, pure tacting, or impure tacting (i.e., “what color?”) without explicit instruction in other or all functions. That is, because children demonstrate match-red-with-red does not mean they can respond to the question, “What color is this?” Most children do acquire joint stimulus function without direct instruction, while others require extensive instruction. Arguably, these different responses involve the different repertoires of listener and speaker within the same organism (Lodi & Greer, 1989); that is, responding to vocal instructions to point to a stimulus or match a stimulus are listener responses, whereas pure tact and impure tact responses are speaker responses. Indeed, Lowe, Horne, Harris, and Randle (2002) reported that teaching tacts resulted in joint stimulus control across different repertoires of verbal behavior or naming. Presumably, their students already had a naming repertoire. Students with the naming repertoire have speaker as own listener repertoires (Greer, 2002; Skinner, 1957). Multiple exemplar instruction also provides a source to bring about this transformation of stimulus function or naming for those children who do not have the repertoire (Greer, 2002; Greer & Keohane, 2004; Greer, Stolfi, Chavez-Brown, & Rivera-Valdez, 2004).

We suggest that what we characterize as the acquisition of joint stimulus function for the children in our experiments resulted from multiple exemplar training in which the students were taught both responses to a subset of words. It would seem that alternation of instruction across responses that occurred in the instructional procedures for a subset of words produced joint stimulus function for both responses to novel words taught as a single response. Moreover, the experience produced correct responding to untaught response that they could not do prior to the multiple exemplar instruction. Catania (1998, p. 392) characterized this kind of responding as a “higher-order class” of behavior.

One interpretation is that the students acquired a kind of “overarching” control of the spoken word for written and vocal responding as described by Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, and Cullinan (2000). From this perspective, the MEI experiences transformed the spoken words emitted by the experimenter from stimulus control over taught responses to joint stimulus control over taught and untaught responses. In the present studies, specific instructional experience resulted in the acquisition of untaught responses after learning a single response. Initially, the stimulus controlled only the responses taught; after we provided the multiple exemplar instructional history with a subset of words, the stimulus control was transformed such that the learning of one response controlled responses not directly taught.

Whether or not a multiple exemplar history results in the emergence of the more basic derived relations within the stimulus equivalence or relational frame match-to-sample scenarios was not tested in the present experiments (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001). It is probable that the fundamental derived relations were already present for all of our students. That is, all of our children could textually respond to letters (i.e., see and say the letters) and take dictation for letters (i.e., hear and write letters) prior to the experiment. It is possible that these repertoires provided the instructional prerequisites or derived relations that allowed the students to then acquire joint stimulus functions as a result of the MEI. That is, the alternation between hearing the words and saying the letters and hearing the words and writing for the subset of words used in the MEI provided the necessary experience to produce untaught responses. They could hear and write letters and they could see and say letters but required rotation between hear and say and hear and write to acquire the joint stimulus control that was made possible by the letter stimulus control across both saying and writing. Several of the children were observed to begin to say the letters as they wrote them, suggesting that the transformation of stimulus function resulted from a derived relation between saying the letters and writing them. Indeed Skinner (1957, p. 191) suggested it was likely that the experiences of transcription and dictation lead to the development of what he called the “same response in different media.” Once individuals have derived relations between saying the letter and writing the letter, rotated experiences for a subset of exemplars can result in the emission of untaught response forms. While we did not test for the presence of this derived relation, it is possible that the design and procedures that we employed could be used to test the role of multiple exemplar instructional histories on the emergence of equivalences or derived relations for the more basic saying and writing of letters.

We considered the possibility that there may have been some advantage to the order in which the response forms are taught. The two students who emitted some correct responses in the baseline probe were taught the vocal response in baseline and probed on the written responses (Students J and T), while the two students who were taught the written response and probed on the vocal response emitted no correct responses on the vocal probes for the baseline. This suggested that the mastery of vocal spelling first might have been advantageous for these students; however, in Experiment 2, no advantages were seen. When individuals have phonetic textual repertoires, which the students in the second experiment may have had, and also relevant writing and saying of words, the phonetic responding probably allows the emission of untaught responses provided that the word is spelled phonetically. The students in the first experiment had no phonetic training; hence the letters controlled the acquisition of the joint stimulus. However, the students in the second experiment had some phonetic reading instruction and phonetic control may have occurred.

A critical aspect of the validity of the functional relationship between the multiple exemplar instruction and the development of joint stimulus control concerns the instructional history of the students. Indeed, our choice of educationally important responses (i.e., actual words) is one of the attributes of our study that distinguished our experiment from typical laboratory studies. Match-to-sample research typically uses contrived stimuli to avoid any possible confounds that might be related to instructional history. However, our knowledge of the relevant instructional history of each of these students was well documented because we had taught and measured the acquisition of these repertoires. Replication of our procedures using nonsense words would enhance the internal validity of our findings and needs to be done in cases in which the instructional history is not controlled. A second attribute that distinguished our work from typical laboratory studies was the fact that we collected the data in a classroom rather than an isolated area. While the latter aspect might seem unusual in a laboratory study, there are scientifically desirable aspects; to wit, the results are not attributable to any novelty effects associated with collecting data or providing behaviorally based instruction.

Our students in the first experiment had no instruction in spelling words in either response topographies prior to the instruction provided in the classrooms in the months preceding the experiment. In that period of time we taught one student to spell four words vocally and one to spell five words vocally, while the other two students had no spelling experience in either response forms. None of them had written responses nor simple match, point, pure tact, or impure tact repertoires prior to our instruction. None of the students had skills of writing letters, functional writing, textual responding, or text-picture match-to-sample repertoires prior to our instruction. Moreover, two of the students did not have simple tact or mand repertoires at the beginning of the year in which they were introduced to the behavior analysis classroom as assessed by the PIRK (Greer & McCorkle, 2000). The other two had minimal tact and mand repertoires as assessed also by the PIRK. During the five months prior to the experiment, the students were taught prerequisite verbal repertoires, including, in the cases of two of the students, vocal-spelling responses to a few words as described. Thus, the complete instructional history in the repertoire was known, and any minimal instruction in related repertoires was provided in the classroom in a controlled instructional environment (i.e., all responses to all instruction was directly recorded by reliable transducers). The students in the replication experiment had received instruction in spelling prior to the experiment and they had more advanced academic repertoires; however, prior to the multiple exemplar instruction they could produce only minimal untaught spelling topographies. Moreover their complete instructional history was known also. That is, the students in the second experiment were performing above their non-categorized peers at the time of the experiment; however over the two years prior to the study we taught them listener repertoires, speaker repertoires, textual responding, and writing responses.

Multiple exemplar instruction, also termed general case instruction, has been used extensively in the curricular design procedures associated with Direct Instruction (Becker, 1992). Becker (1992) and others (Engelmann & Carnine, 1982) reported the successful effects of multiple exemplar instruction on teaching phonetic textual responding, in particular phonetic pronunciation of novel words not encountered in instruction. It is possible that the use of multiple exemplar instruction for teaching the general case in the Direct Instruction curricula represents a testament to the utility of the multiple exemplar experience.

The applications of MEI by Engelmann and Carnine (1982), Becker (1992), Greer and Lundquist (1976), and Fields et al. (2003) were directed towards the development of abstract stimulus control. Whereas in the present studies, the target is the development of joint stimulus control for what were initially independent verbal responses. Nuzzolo-Gomez and Greer (2004) also used MEI to induce usage of untaught mand and tact operants in children for whom these were initially independent. Thus, multiple exemplar experiences in the present and related experiments involve the transformation of stimulus or establishing operation control rather than abstraction of stimulus control.

If the effects of multiple exemplar experiences hold widely for the transformation of stimulus or establishing operations control in instructional settings, tests of the presence or absence of these functions can lead to instructional interventions that provide new verbal capabilities for student for whom these higher order operants are missing. These and related findings suggest that the presence or absence of joint stimulus control may constitute critical verbal milestones, ones that constitute true “developmental” repertoires (Greer & Keohane, 2004). More importantly research on producing transformation of functions may allow students who do not have these critical repertoires to acquire them. Greer (2002) described how students may be reliably and usefully categorized according to levels of verbal behavior (pre listener, listener, speaker, speaker/listener, speaker as own listener, reader, writer, self-editor). Each of these levels constitutes a milestone in what might be characterized as critical verbal repertoires. MEI may provide the wherewithal to teach students to acquire these capabilities more reliably than we have been able to do in the past.

We use the term learn units because the term identifies the tested components of instruction that have been found to be strong predictors of instructional effectiveness (Emurian et al., 2000; Greer & McDonough, 1999). A learn unit is a measure of instructional validity in that instructional presentations that are learn units insure attention by the subject to the stimulus conditions, a response opportunity followed by the presentation of known reinforcers for responding in the case of a correct response, and a correction operation that insures the student emits the corrected response without reinforcement for the correction following an incorrect response. The evidence shows the learn unit to be a necessary, if not sufficient, set of conditions to implement an independent variable that requires a test of the relation between the acquisition of a particular repertoire and the effect of that repertoire on the emergence of another repertoire. The literature on the learn unit reports that it is critical to the reliability of an intervention to specify whether learn units are in place.

While our results call for additional replications and extensions to other types of responses, the data are compelling for the development of joint stimulus function across spoken and written verbal operants. They add credibility to the notion that generative verbal behavior can be a result of instructional history or incidental multiple exemplar histories. While we do not know whether the development of joint stimulus function is necessarily a result of multiple exemplar histories in all or most cases, in the experiments we reported such experiences were sufficient to produce novel verbal functions. While we did not address the component derived relations such as the sounding and writing of letters, we do speculate that the necessary components were present and that the presence of this repertoire was a necessary prerequisite for the multiple exemplar experience to develop joint stimulus control. Additional analyses are needed to test this possibility.

Although it would be difficult to prove that changes in responses in one medium bring about changes in responses in another medium at least the contrary has not been proved. Functional connections between the two media must be carefully specified and analyzed in accounting for specific instances, and the traditional point of view offers no help in simplifying this analysis. (Skinner, 1957, p. 195)

Footnotes

We are grateful to Claire Eagan for her assistance in the collection of the data. In addition we are appreciative of the efforts of Regina Spilotras for her assistance in the reliable assessment of the instructional histories of each of the students. We are also indebted to Olive Healy and Yvonne and Dermot Barnes-Holmes for assisting us in our efforts to build more powerful scientifically based instruction. Finally, we are especially appreciative of the accurate, useful, and informative comments of the anonymous reviewers of this paper and the editor of The Analysis of Verbal Behavior.

REFERENCES

- Albers A, Greer R. D. Is the three term contingency trial a predictor of effective instruction. Journal of Behavioral Education. 1991;1:337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y, Cullinan V. Relational frame theory and Skinner's verbal behavior: A possible synthesis. The Behavior Analyst. 2000;23:69–84. doi: 10.1007/BF03392000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker W. Direct instruction: A twenty-year review. In: West R, Hamerlynck L, editors. Design for educational excellence: The legacy of B. F. Skinner. Longmont, CO: Sopris West; 1992. pp. 71–112. [Google Scholar]

- Catania A. C. Learning. (4th Edition) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dougher M, Perkins D. R, Greenway D, Koons A, Chiasson C. Contextual control of equivalence-based transformation of functions. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;78:63–93. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emurian H. H, Hu X, Wang J, Durham D. Learning JAVA: A programmed instruction approach using applets. Computers in Human Behavior. 2000;16:395–422. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann S, Carnine D. Theory of instruction: Principles and applications. New York: Irvington; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Fields L, Reeve K. F, Mateneja P, Varelas A, Belanich J, Fitzer A, Shannon K. The formation of a generalized categorization repertoire: Effects of training with multiple domains, samples, and comparisons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2003;78:291–313. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granzin A. C, Carnine D. Child performance on discrimination tasks: Effects of amount of stimulus variation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 1977;24:232–242. [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D. Designing teaching strategies: An applied behavior analysis systems approach. New York: Academic Press; 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, Keohane D. The evolution of verbal behavior. 2004. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, Keohane D, Meincke K, Gautreaux G, Pereira J, Chavez-Brown M, Yuan L. Key instructional components of effective peer tutoring for tutors, tutees, and peer observers. In: Moran D, Malott R, editors. Empirically Validated Educational Methods. New York: Elsevier; (in press) (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, Lundquist A. Discrimination of musical form through conceptual [general case operations] and nonconceptual successive approximation strategies. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education. 1976;47:8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, McCorkle N. CABAS® international curriculum and inventory of repertoires from pre-school through kindergarten. Yonkers, NY: CABAS and the Fred S. Keller School; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, McDonough S. H. Is the learn-unit a fundamental measure of pedagogy. The Behavior Analyst. 1999;21:5–16. doi: 10.1007/BF03391973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, Ross D. E. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavioral Intervention. Verbal Behavior Analysis: A Program of Research in the Induction and Expansion of Complex Verbal Behavior. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Greer R. D, Stolfi L, Chavez-Brown, Rivera-Valdez C. The emergence of the listener to speaker component of naming in children as a function of multiple exemplar instruction. 2004. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B, editors. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of language and cognition. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001. (Eds.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C, Fox E, Gifford E. V, Wilson K.G. Derived relational responding as learned behavior. In: Hayes S. C, Barnes-Holmes D, Roche B. E, editors. Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2001. (Eds.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner R. D, Baer D. M. Multiple-probe technique: A variation on the multiple baseline. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1978;11:189–196. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham P, Greer R. D. Changes in student and teacher responses in observed and generalized settings as a function of supervisor observations of teachers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:153–164. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarre J, Holland J. G. The functional independence of mands and tacts. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1985;43:5–19. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1985.43-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm N, Greer R. D. A systematic replication of CABAS in Italy. Journal of Behavioral Education. 1991;1(4):427–444. [Google Scholar]

- Lodhi S, Greer R. D. The speaker as listener. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1989;51:353–359. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1989.51-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe C. F, Horne P. J, Harris D. S, Randle V. R. L. Naming and categorization in young children: Vocal tact training. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;78:527–549. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsico M. J. Textual stimulus control of independent math performance and generalization to reading. 1999. (Doctoral Dissertation, 1998, Columbia University) UMI Proquest Digital Dissertations [on line]. DissertationsAbstract Items: AAT 9970241. [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzolo-Gomez R, Greer R. D. Emergence of untaught mands or tacts of novel adjective-object pairs as a function of instructional history. Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2004;20:63–76. doi: 10.1007/BF03392995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter D, Neuringer A. Music discrimination by pigeons. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1985;10:138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ross D. E, Greer R. D. Generalized imitation and the mand: Inducing first instances of functional speech in nonvocal children with autism. Journal of Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2003;24:58–74. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(02)00167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B. F. Verbal behavior. Boston MA: Copley; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Selinski J, Greer R. D, Lodhi S. A functional analysis of the comprehensive application of behavior analysis to schooling. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:107–118. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague J. R, Horner R. H. The effects of single instance, multiple instance, and general case training on generalized vending machine use by moderately and severely handicapped students. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1984;17:273–278. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1984.17-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford M.W, Sundberg M.L, Braam S.J. A preliminary investigation of the consequences that define the mand and the tact. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1988;6:61–71. doi: 10.1007/BF03392829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiouri I, Greer R. D. Inducing vocal verbal behavior through rapid motor imitation responding in children with severe language delays. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2003;12(3):185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Twyman J. The functional independence of impure mands and tacts of abstract stimulus properties. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 1996;13:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Williams G, Greer R. D. A comparison of verbal behavior and linguistic curricula. Behaviorology. 1993;1:31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Young J. M, Krantz P. J, McClannahan L. E, Polson C. L. Generalized imitation and response class formation in children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Anlysis. 1994;27:685–697. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]