Summary

Fine-tuning of the biophysical properties of biological membranes is essential for adaptation of cells to changing environments. For instance, to lower the negative charge of the lipid bilayer, certain bacteria add lysine to phosphatidylglycerol (PG) converting the net negative charge of PG (–1) to a net positive charge in Lys-PG (+1). Reducing the net negative charge of the bacterial cell wall is a common strategy used by bacteria to resist cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs) secreted by other microbes or produced by the innate immune system of a host organism. The article by Klein et al. in the current issue of Molecular Microbiology reports a new modification of the bacterial membrane, addition of alanine to PG, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In spite of the neutral charge of Ala-PG, this modified lipid was found to be linked to several resistance phenotypes in P. aeruginosa. For instance, Ala-PG increases resistance to two positively charged antibacterial agents, a β-lactam and high concentrations of lactate. These findings shed light on the mechanisms by which bacteria fine-tune the properties of their cell membranes by adding various amino acids on the polar head group of phospholipids.

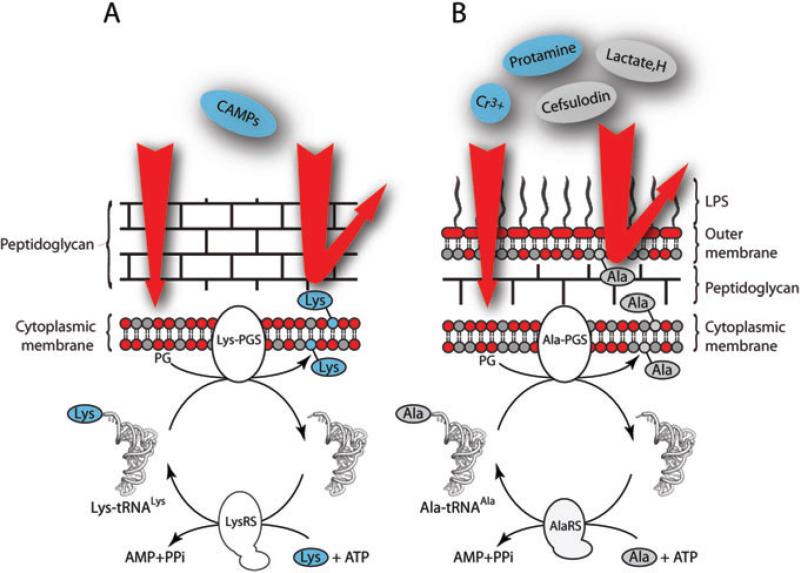

Aminoacyl-phosphatidylglycerol synthases (aa-PGS) are integral membrane proteins found at the cytoplasmic membrane of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. These enzymes are responsible for the addition of amino acids to the polar head of phosphatidylglycerol (PG) within the membrane in a tRNA-dependent fashion, using aminoacylated tRNA as donor molecule (Fig. 1). Klein et al. (2008) report for the first time several resistance phenotypes linked to the biosynthesis of Ala-PG in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and demonstrate that under acidic conditions Ala-PG biosynthesis accounts for up to 6% of the total lipids in the membrane. This is a fairly high proportion that is comparable to cardiolipin levels in Escherichia coli (5%), a lipid known to have an impact on membrane fluidity and function (Cronan, 2003). The authors also show that Ala-PG biosynthesis is not under the control of the general response regulator sigma S (rpoS) or the stringent response regulator SpoT/RelA, both of which are often responsible for the rapid adaptation of bacteria to environmental stresses.

Fig. 1.

tRNA-dependent pathway of PG aminoacylation in the membranes of Staphylococcus aureus (A) and P. aeruginosa (B). Addition of Lys or Ala to the PG of bacterial membranes is accomplished by a specific aminoacyl-phosphatidylglycerol synthase (Lys-PGS or Ala-PGS) using aminoacyl-tRNAs (Lys-tRNALys or Ala-tRNAAla) as amino acid donors. Each aminoacyl-tRNA is formed by its cognate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (LysRS or AlaRS) in the presence of amino acid and ATP. Addition of Lys enhances the resistance of S. aureus to various CAMPs and addition of Ala increases the resistance of P. aeruginosa to several bactericidal agents including the CAMP protamine. Positively charged molecules are indicated in red and neutral ones in grey.

The biological role of Ala-PG was further investigated by using phenotypic microarrays to compare wild-type P. aeruginosa and a mutant strain deficient in its ability to synthesize Ala-PG. In this high-throughput screening technique, both strains were tested in over a thousand different growth conditions to explore the effects on bacterial growth of various nutrients, antibiotics, pH and osmotic conditions. Ala-PG conferred a growth advantage when the bacteria were cultured in the presence of a diverse group of substances such as the cationic antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) protamine, the heavy metal chromium(III), the osmolyte sodium lactate and the β-lactam cefsulodin. This screen, which included a wide variety of antibiotics and other inhibitors, did not reveal any other compound for which the biosynthesis of Ala-PG led to a significant improvement in growth. This result is of special interest because of the recent identification in Clostridium perfringens of two ORFs encoding each a Lys-PG synthase (Lys-PGS) and an Ala-PG synthase (Ala-PGS) (Roy and Ibba, 2008). The physiological significance of Lys-PG has been investigated in several organisms and it has been demonstrated that this lipid modification helps microorganisms evade the action of CAMPs (see the article by Klein et al. for references). The bacterial membrane is essentially composed of phospholipids that have a high net negative charge. Addition of Lys lowers the net negative charge of the cellular membrane and diminishes its affinity for CAMPs, thereby enhancing the resistance of the bacteria to these compounds (Peschel et al., 2001). The biological significance of Ala-PG was not clear, since addition of Ala only neutralizes the negative charge of PG and would not be expected to impart a net positive charge to the membrane. It was proposed that the Ala modification might be involved in other cellular mechanisms and may not play a direct role in cellular evasion of CAMPs (Roy and Ibba, 2008). Klein et al. (2008) show that, despite the neutral charge of Ala-PG, this modification is also involved in resistance to CAMPs such as protamine. In addition, this work shows that Ala-PG is important for sustaining bacterial growth in other environmental contexts and suggests that Ala-PG might also be used to change more general permeability properties of the cellular membrane.

CAMPs are evolutionarily ancient ‘weapons’ that are found in all domains of life. Their size ranges from a few to several hundred amino acids and they display a wide range of structures, charge distribution and post-translational modifications. The variety of their many unique modes of action reflects their structural diversity. CAMPs kill bacteria by forming pores in membranes using mechanisms that involve interacting either with phospholipids or with specific structures found at the membrane surface. Once pores are formed, cell death is caused by leakage of intracellular metabolites and dissipation of the proton motive force. Offensive and defensive strategies between competing microorganisms from the same niche, or between a host and a pathogen, are the consequence of dynamic co-evolutionary processes (Peschel and Sahl, 2006). The finding that Ala-PG is involved, like Lys-PG, in resistance to CAMPs, illustrates one example of how organisms have co-evolved defence mechanisms to respond to attack from other organisms. Since Ala-PGS and Lys-PGS are evolutionary related, it is possible that one protein evolved into the other to better adapt the bacterial response to a specific set of CAMPs found in a particular environment. Understanding whether Ala-PG and Lys-PG are each required to provide protection against specific subgroups of CAMPs, and how much overlap there is between these activities, will provide new insights into microbial adaptation to hostile environments.

Klein et al. (2008) also show that Ala-PG increases the resistance of P. aeruginosa to the β-lactam cefsulodin, whose antibiotic activity is mechanistically distinct from that of CAMPs. β-Lactams block periplasmic penicillin-binding proteins, which are required for the transpeptidation of peptidoglycan chains. The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria provides an efficient barrier against β-lactams, which cannot diffuse freely through the lipid bilayer. Uptake of these molecules into the periplasmic space is achieved through channels formed by porins located in the outer membrane. Some non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria, such as P. aeruginosa, are inherently resistant to most conventional antibiotics and are clinically difficult to treat (Hancock, 1997). The mechanism of resistance of these bacteria is mainly associated with the low permeability of their outer membrane to antibiotics, which is less than 5% of that observed with Escherichia coli (Hancock, 1997). P. aeruginosa porins are larger and are as numerous as those found on the surface of E. coli. The difference in membrane permeability between the two organisms lies in the fact that only a small fraction of the P. aeruginosa pores have the ability to form open channels on the surface of the cell (for review see Nikaido, 2003). In addition to the low outer membrane permeability, P. aeruginosa resistance to β-lactams is enhanced by the presence of β-lactamase and multi-drug-efflux pumps. The factors that direct the different folding pathways leading to the open and closed conformations of porins remain elusive. Previous work showed that porin permeability can be modulated by temperature (De Jaouen et al., 2004). Klein et al. (2008) show that Ala-PG is found in the inner and the outer membranes and enhances the resistance of P. aeruginosa to cefsulodin. Lipid composition and the presence of certain phospholipids in the membrane are known to modulate the folding and activity of certain membrane proteins (Cronan, 2003; Lee, 2003), and it is attractive to think that Ala-PG might influence porin permeability either directly or indirectly, thus modulating the uptake of nutrients and of this antibiotic.

While Ala-PG expands the spectrum of resistances to antibiotics, the work of Klein et al. (2008) shows for the first time that aminoacylated lipids can also influence the permeability of the lipid bilayer to osmolytes. Bacteria can resist dramatic changes in their environments and their survival depends on being able to adapt their membrane lipid composition in response to changes in temperature, osmolarity and pH as well as antibacterial agents (e.g. CAMPs). Fluidity and permeability must be maintained in a wide range of conditions, not only to ensure the proper function of membrane proteins but also to maintain selective movement of osmolytes in and out of the cellular compartment. To maintain the biological properties of their membrane, bacteria can modify the pre-existing membrane phospholipids to adapt their cell wall rapidly to new environmental conditions. Modifications can affect either the nature of the polar head group or the level of unsaturation of the acyl chains of lipids. Ala-PG synthesis provides an advantage for P. aeruginosa challenged with high concentrations of lactate in the culture medium. These findings suggest that Ala-PG might diminish the membrane permeability, resulting in decreased diffusion of lactate into the cell. Lactate is an efficient bactericidal molecule, as evidenced by its ability to preserve food upon lactic fermentation. Lactate is a weak acid (pKa = 3.9) and, at neutral pH, a fraction of the molecules are protonated. This undissociated form can act as a proton carrier and diffuse passively into the cell through the lipid bilayer. High concentrations of lactate outside the cell result in the accumulation of lactic acid and protons inside the cell (Rubin et al., 1982). It is not clear whether lactate accumulation or a decrease in pH inside the cell is at the origin of the bactericidal activity of lactate (McWilliam Leitch and Stewart, 2002). Whichever is the case, Ala-PG not only reduces the sensitivity of P. aeruginosa to CAMPs, but also plays a role in the permeability of the cellular membrane, since Ala-PG confers an advantage to P. aeruginosa cultured in the presence of large amounts of lactate. These findings suggest that Ala-PG might be involved in a general mechanism that affects the permeability of the bacterial membrane.

Previous reports showed that several microorganisms use other amino acids besides Ala and Lys to modify phospholipids (see article by Klein et al., 2008). The functions of these other modifications remains unexplored and the possible use of other amino acids in addition to those previously reported is not yet known. The recent discovery of lipid domains in bacteria emphasizes the expanding role of lipid aminoacylation in bacterial physiology (Matsumoto et al., 2006). Lipid domains in membranes are involved in cell division and sporulation, and are suspected to be induced by lipid–lipid and lipid–protein interactions. In this context, aminoacylated phospholipids provide a rich collection of functional groups that are able to create an assortment of interactions between the phospholipid head groups, thereby modifying the organization and function of lipid domains within the membrane. The work of Klein et al. in the current issue of Molecular Microbiology underlines the physiological significance of Ala-PG under a variety of challenging growth conditions, and provides new insights into the dynamic processes that allow bacteria to adapt rapidly to new and changing niches.

Acknowledgements

Work in the authors’ lab on this topic is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM65183 to M.I.).

References

- Cronan JE. Bacterial membrane lipids: where do we stand? Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:203–224. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jaouen TE, Chevalier S, Orange N. Pore size dependence on growth temperature is a common characteristic of the major outer membrane protein OprF in psychrotrophic and mesophilic Pseudomonas species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6665–6669. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6665-6669.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock RE. The bacterial outer membrane as a drug barrier. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:37–42. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)81773-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S, Lorenzo C, Hoffmann S, Walther JM, Storbeck S, Piekarski T, et al. Adaptation of Pseudomona aeruginosa to various conditions includes tRNA-dependent formation of alanyl-phosphatidylglycerol. Mol Microbiol. 2008;71:551–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AG. Lipid–protein interactions in biological membranes: a structural perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1612:1–40. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam Leitch EC, Stewart CS. Escherichia coli O157 and non-O157 isolates are more susceptible to l-lactate than to d-lactate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:4676–4678. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.9.4676-4678.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Kusaka J, Nishibori A, Hara H. Lipid domains in bacterial membranes. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:1110–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschel A, Sahl HG. The co-evolution of host cationic antimicrobial peptides and microbial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:529–536. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschel A, Jack RW, Otto M, Collins LV, Staubitz P, Nicholson G, et al. Staphylococcus aureus resistance to human defensins and evasion of neutrophil killing via the novel virulence factor MprF is based on modification of membrane lipids with l-lysine. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1067–1076. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.9.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy H, Ibba M. RNA-dependent lipid remodeling by bacterial multiple peptide resistance factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4667–4672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800006105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin HE, Nerad T, Vaughan F. Lactate acid inhibition of Salmonella typhimurium in yogurt. J Dairy Sci. 1982;65:197–203. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(82)82177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]