Abstract

Purpose of Review

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), an inflammatory rheumatic disease characterized by autoantibody production and diverse clinical manifestations, disproportionately affects vulnerable groups: women, racial and ethnic minorities, the poor, and those lacking medical insurance and education. We summarize the current knowledge of the disparities observed in SLE and highlight recent research that aims to dissect the causes of these disparities and to identify the potentially modifiable factors contributing to them.

Recent Findings

Several remediable causes, including lack of education, self-efficacy, and access to quality, experienced healthcare, have been found to contribute to observed disparities in SLE prevalence and outcomes.

Summary

SLE is associated with alarming disparities in incidence, severity and outcomes. The causes of these disparities are under study by several research groups. Identifying potentially correctable contributory factors should allow for the development of effective strategies to improve the healthcare delivery and outcomes in all SLE patients.

Keywords: Systemic lupus erythematosus, health disparities, socioeconomic status, heath care access

Introduction

Health disparities, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Working Group on Health Disparities, have been defined as, “differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality and burden of diseases and other adverse health conditions that exist among specific population groups in the US”1. The study of disparities in health outcomes and their causes is now a national priority. Sociodemographic disparities in the incidence and severity of many chronic diseases, including obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic renal disease, have been observed1–3. Vulnerable populations may be defined by age, race/ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, geographic residence or other characteristics1.

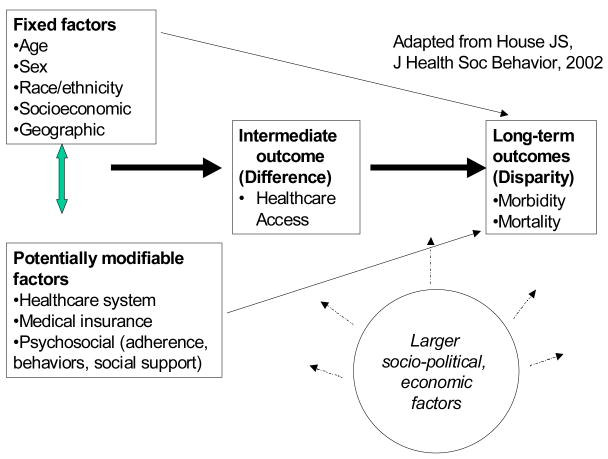

Of the numerous conceptual frameworks describing determinants of health outcomes disparities, a conceptual model articulated by House includes sociodemographic factors that are relatively fixed, such as age, sex, race, ethnicity and geographic location, and those that are potentially modifiable4, 5 (Figure 1). The NIH Strategic Plan on Health Disparities focuses on differences in health care delivery6, an important potentially modifiable factor in the pathway between belonging to a specific sociodemographic group and ultimate healthcare outcomes. Healthcare system factors, medical insurance, and psychosocial factors, including adherence, education, and social support, are also potentially modifiable factors that may interact with fixed sociodemographic factors or act independently and influence long-term outcomes, creating health outcomes disparities.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework For Understanding sociodemographic Differences and Disparities in SLE

Health Disparities in SLE

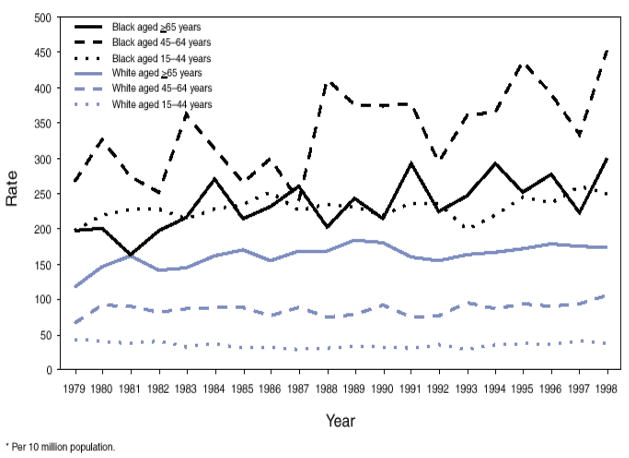

Among the rheumatic diseases, SLE is the most strongly associated with disparities in its incidence, prevalence, and long-term outcomes7, 8. SLE incidence appears to have increased in the general U.S. population over the past four decades9 and SLE has one of the highest mortality rates of the rheumatic diseases9, 10. Prognosis is improved by prolonged, complex and potentially toxic therapies. For unknown reasons, SLE is most prevalent among women and those of non-Caucasian descent; those of African heritage are the most affected population. Lupus incidence rates among Black females, for example, are 3–4 times those of white females. Mean age at onset of lupus is younger among Blacks11, 12, and disease damage accrues more quickly13. Non-whites with lupus have mortality rates at least > 3 times as high as whites10, 14–17. The Centers of Disease Control documented that lupus mortality rates from 1979–1998 were more than 5 times higher for women than for men10. The highest and fastest increasing SLE mortality rates in the U.S. from 1979–98 were observed among African American women aged 45–6410. In this population, a 69.7% increase in mortality was seen. (Figure 2). Other racial and ethnic minorities, including Hispanics, Asians and Native Americans, the poor, those lacking medical insurance and education, are also at increased risk of developing SLE and of poor outcomes from the disease.

Figure 2.

Systemic lupus erythematosus death rates* among females, by age group and race – United States 1979–1998

*per 10 million population

The root causes of these disparities and the potentially remediable factors contributing to them remain poorly understood. The disparities observed in SLE are likely to be explained only partially by genetic, hormonal and biologic factors. Genetic and biologic differences between racial and ethnic groups and between males and females cannot explain the socioeconomic “gap” in SLE incidence, severity and outcomes, nor the widening of this gap over time.

Several research groups are investigating the underlying causes of disparities in the incidence, prevalence and health outcomes among individuals with SLE. In particular, we reviewed those that have focused on healthcare system factors. The studies reviewed herein have significantly contributed to our growing understanding of the multiple causes of SLE disparities and have helped to identify potentially correctable contributory factors. Although lupus does affect some males, it is predominantly a disease of women. Before puberty, lupus is approximately twice as common in girls. At the onset of puberty, the rate in females begins to climb, reaching a peak ratio of 8–9:1 from ages 15–45. After menopause, the disproportionate incidence rates in women decline to approximately twice those in men18, 19. Rates of lupus nephritis and lupus nephritis end-stage renal disease, necessitating renal dialysis or transplantation, are also much higher among women compared to men20. Genetic and/or hormonal differences may underlie much of the female predominance in SLE, but have yet to be well quantified21.

By most measures, including income, educational level, wealth, medical insurance, occupation and area-based socioeconomic measures, individuals with lower socioeconomic status (SES) have higher rates of incidence, severity and mortality from SLE than do those of higher SES 16, 22–33. SLE mortality is highest in the U.S. South and associated with poverty and Hispanic ethnicity34, 35. Women also earn substantially less income than men and more women than men live below the Federal poverty level in the U.S. (22.5% of women vs. 18.3% of men in 2004)36. SES may thus be contributing to observed disparities in SLE incidence and outcomes with regard to sex.

SLE incidence, morbidity and mortality are all much higher among non-white than white racial and ethnic groups in the U.S10, 37. Constituted in 1994, LUpus in MInorities: NAture vs. nurture (LUMINA) is a multi-ethnic (Hispanic, African American and Caucasian), longitudinal SLE cohort study based in Alabama, Texas and Puerto Rico 28–33. It currently has 636 participants who meet the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for the classification of SLE38, 39, have disease duration of at least 5 years, and are at least 16 years of age40. The relationship of race/ethnicity and SES to the increased SLE incidence and poorer survival in African and Hispanic-American patients have been studied in LUMINA 28–33. An early analysis followed 288 SLE patients for 5 years from study onset. During this time, 34 (11.8%) patients died and LUMINA investigators have attempted to disentangle race/ethnicity from SES as predictors of SLE mortality28. Those with incomes below the Federal poverty level were four times more likely to die than were those with higher incomes28, 41. After adjustment for poverty and medical insurance, the risk of SLE progression was greatly reduced among both African American and Hispanic participants24. Significant predictors of poor outcomes and disease progression in this cohort have included Hispanic and African American ancestry, as well as poverty, lack of education, and lack of social support (not married or living together)33.

The LUMINA cohort has also allowed the investigation of racial and ethnic disparities in specific SLE manifestations and outcomes, including renal disease, myocarditis, hypertension, and work disability31, 42–45. LUMINA participants who developed renal disease were younger, had more hypertension and more were African American or Texan Hispanic 31, 42, 43. African American and Texan-Hispanic ethnicity and obesity were also risk factors for developing hypertension in LUMINA46. Abrupt SLE onset, as opposed to a more insidious subacute onset, was associated with younger age, lower SES and predicted more severe ongoing clinical manifestations and higher disease activity40. African Americans in LUMINA had a strikingly higher risk of developing myocarditis (60.9%) compared to (1.9%) of Hispanics from Puerto Rico44. LUMINA investigators found that age, smoking, alcohol intake, education, poverty and health insurance were not associated with the risk of myocarditis however. In addition, LUMINA SLE patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds were more likely to become disabled45. Lotstein and colleagues found in past work that women with SLE of lower SES as captured by the Hollingshead Index, which incorporates educational level and occupational prestige, had more functional disability and more cumulative organ damage47. In LUMINA, poverty, total disease duration, disease activity and damage accrual were predictors of work disability45.

In the Hopkins Lupus Cohort of 1378 individuals with SLE, low SES, defined as a household income less than $25,000, had a 70% survival compared to an 86% survival rate for those with a higher household income48. African American background was associated with decreased survival in univariate analysis, but was not an independent predictor after adjustment for income and education48. This suggests that SES influences SLE severity and mortality independently of race/ethnicity.

Following the documentation of clear health disparities in SLE, the research impetus over the past few years has been to go beyond description and to address fundamental questions about their causes. In particular, what aspects of low SES are responsible for disparities in SLE, and can specific potentially modifiable factors be identified to allow the targeting of future efforts to decrease disparities in SLE? These two questions are enormously challenging. The multiple causes of poor outcomes in SLE are overlapping and interactive. Race, SES, and factors closely associated with each, such as reduced access to quality healthcare, reduced comprehension of disease and the medical system, increased competing home and work demands, and reduced self-confidence and social support, have been tightly correlated and predictive of SLE disease activity, organ damage and functional ability in past research studies26, 27, 47, 49–51. Genetic factors undoubtedly contribute to racial and ethnic disparities in SLE outcomes. The identification of new genetic factors involved in SLE pathogenesis promises improved understanding and identification of new molecular pathways and targets. Given the large sociodemographic “gap” in SLE outcomes that continues to grow, genetic factors alone are unlikely entirely responsible. Additionally genetic factors, like sex, are not modifiable and thus not amenable to interventions to decrease observed disparities. Current research is taking on the challenge of dissecting the overlapping, non-discrete aspects of race/ethnicity and SES, and how their components could be acting to create disparities in SLE incidence and long-term outcomes.

1. Education and self-efficacy

In several studies, the educational level of SLE subjects has been predictive of outcomes. A greater number of years of education may improve outcomes by increasing medical understanding, confidence in one’s ability to manage a chronic disease, and/or the ability to communicate and self-advocate effectively in patient-doctor interactions. In a multicenter SLE study, lower self-efficacy for disease management (the belief that one has the ability to control one’s disease), less social support, and younger age at diagnosis were associated with greater disease activity and cumulative organ damage 51. Employing data from the US Multiple Causes of Death data from 1994 to 1997, Ward found that fewer years of education was associated with increased SLE-related mortality, particularly among whites52. This was not found among ethnic minorities, however, possibly due to under-ascertainment of lupus-related deaths in less-educated patients. Not surprisingly, lower educational level was associated with adverse SLE pregnancy outcomes in the LUMINA cohort53.

Educational level, and related medical understanding and self-efficacy, are likely related to the quality of patient-physician interactions. Ward and colleagues audiotaped routine visits between 79 women with SLE and their rheumatologists and assessed for active patient participation and the degree of patient-centered communication of the physician54. Patients who had participated more actively in their visits had less permanent organ damage at the end of a median of 4.7 years follow-up. Karlson and colleagues enrolled 122 women with SLE into a 12-month randomized controlled trial of a theory-based intervention to improve patient self-efficacy and social support for management of SLE. At the end of the trial, those subjects who had received the intervention had improved significantly in measures of global mental and physical health, as well as fatigue, illustrating that self-efficacy and social support are modifiable predictors of long-term outcomes in SLE55.

2. Depression and lack of social support

In several studies, being married or living with another person, or having identified individuals to provide social support, has been associated with better outcomes in SLE33, 51. In a randomized trial setting, an educational intervention involving SLE patients and an identified social support person to improve both self-efficacy and social support, improved SLE outcomes, underscoring the importance of social support55. Depression on the other hand, likely impedes self-efficacy, adherence, patient-physician communication and is more common in lower SES groups47, 56.

3. Adherence and non-adherence

Lack of education and understanding, distrust in medical institutions and cultural misunderstanding may lead to non-adherence to medical therapy. In an older study, Petri and colleagues reported that while African American lupus patients in the Johns Hopkins Rheumatology Clinic had lower education, income, and job status and poorer medical insurance coverage than did white lupus patients, they also had poorer adherence to medical care as assessed by the physician23. In multivariable analyses, medical adherence and hypertension were more important predictors of the development of renal disease than were race or classical measures of SES. Lack of disease comprehension and reduced self-confidence and social support are related to racial/ethnic background and to SES, and are also predictive of SLE activity, organ damage and functional ability26, 27, 47, 49–51. In the LUMINA cohort, loss to follow up, defined as failure to attend two or more of the consecutive yearly visits, was highest among African Americans, followed by white and then Hispanic patients, who were the least likely to become lost due to follow-up57.

4. Access to care: provider and hospital experience (volume), subspecialist care

Employing data from the U.S. Renal Datasystem, which includes approximately 94% of all individuals in the U.S. with end-stage renal disease requiring chronic renal replacement, Ward examined the age at onset of end-stage renal disease among patients with lupus nephritis according to their medical insurance 58. He found that when analyzed within their own racial/ethnic group, those with Medicaid or no insurance were younger at onset of end-stage renal disease than those with private insurance. This illustrates that the type of medical insurance is related to the rate of progression of renal failure in SLE, but it is not clear what aspect of medical insurance or a variable closely associated with medical insurance is responsible.

Access to quality healthcare or, “the realized ability to receive appropriate medical care in a timely manner, free from geographic or financial barriers”27, is a challenge for minority and disadvantaged groups, and a potentially remediable factor that is associated with outcomes in SLE. Care for patients with lupus, like that of many chronic diseases, necessitates advanced training, experience, strong physician-patient communication skills, and access to other sub-specialists and medical technology. In many complex diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease, the involvement of medical specialists results in better long-term outcomes59–66.

In California, lack of medical insurance was strongly associated with fewer physician visits for SLE patients 27. Yazdany and colleagues conducted a telephone survey of more than 900 SLE patients concerning their subspecialty care and found that older age, lower income and being male were associated with lack of rheumatology follow-up care67. Medicaid SLE patients in California also traveled farther to receive SLE healthcare and were more likely to see a generalist or be seen in the emergency department compared to those with other insurance68. In addition, SLE patients enrolled in health maintenance organizations, compared to those in fee-for-service health plans, utilized less ambulatory care and were less likely to have outpatient surgery and hospital admissions69. In other diseases, lack of physician continuity and regular follow-up, which can be dictated by medical insurance plans, is associated with medical non-adherence as well70. Hospital and physician experience in treating SLE have been associated with SLE outcomes. In-hospital mortality was lower for SLE patients hospitalized at California hospitals with more SLE admissions per year compared to those at hospitals with less experience71. Ward found that the risk of in-hospital mortality for SLE patients in New York and Pennsylvania was inversely associated with the average number of SLE patients that the attending physician had recently admitted72. The inverse relationship between physician experience and SLE mortality was stronger for non-white than white patients. This suggests that provider volume may be an important, and potentially modifiable, barrier to better long-term outcomes among non-white SLE patients 72. The association between physician volume and SLE patient mortality was also stronger for those patients without private medical insurance than for those having it, suggesting that for this vulnerable population in particular access to high quality care is paramount72. Among lupus nephritis patients, having an attending physician who was highly experienced was associated with a 60% reduction in in-hospital mortality risk72.

In another study, Ward examined 16751 hospitalizations for patients with SLE and classified 12.3% as avoidable, an indicator of underutilization or poor access to healthcare 73. Rates of “avoidable hospitalizations”, such as those for pneumonia, cellulitis and congestive heart disease, all potentially avoidable with prompt and correct medical attention and indicative of substandard outpatient care, were lower at medical centers in New York State with high volumes of SLE admissions73. These avoidable hospitalizations for SLE patients were most frequent for older patients and for those in the lowest quartile of SES quartile73. These findings reinforce the importance of physician and hospital experience in preventing avoidable SLE admissions.

Among 6521 hospitalized SLE patients in South Carolina, African Americans were more likely than whites to experience both in-hospital mortality and mortality after one year following hospital discharge74. In South Carolina where 30% of the population is African American, African Americans with SLE had lower levels of education, were more likely to have public insurance, earned lower incomes, had increased hospitalizations and also died at significantly younger ages than their white counterparts. Even after multivariable adjustment for comorbidities, which were more common in African Americans, African American lupus patients had a 15% increased mortality risk compared to whites with lupus74.

5. Geographic and area-level factors

There is growing literature about the important effects of geographic residence and area-level factors, neighborhood poverty level, population composition, employment, educational level, dwelling type, household and family size, and housing occupancy, on a variety of health outcomes including infectious diseases, childhood asthma, orthopedic surgery, and end stage renal disease75–80. In many cases, one’s individual behavior may be better explained by the characteristics of one’s neighbors than by individual factors.

Investigators from the University of California at San Francisco utilized data from a large geographically, socioeconomically and racially diverse SLE cohort to assess the independent effects of neighborhood poverty and individual SES on SLE outcomes56. Both low neighborhood SES and individual SES were associated with increased disease activity, poorer physical functioning, and greater symptoms of depression. The increase in depressive symptoms suggests that SLE patients living in low income neighborhoods have more difficulty dealing with chronic disease, and this likely contributes to decreased self-efficacy for disease management.

Employing the US Renal Data System, Ward examined the influence of area-level SES on the incidence of end-stage renal disease due to SLE, diabetes mellitus and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease81. He used an area-based measure of SES based on subjects’ zip codes of residence, encompassing area poverty, household income, house value, employment and education levels. Among whites, the risk of developing end-stage renal disease from lupus nephritis for those in the lowest compared to highest category was 50–60% higher. For African Americans, however, there was no statistically significant change in risk related to this SES measure. Thus, while this area-based SES measure was associated with SLE renal outcomes among whites, it was not independently predictive among African Americans. When comparing different disease causes of end-stage renal disease, area-based SES had a more important influence on outcomes for SLE renal disease than for polycystic kidney disease, where genetic factors may play a larger role, but less so than for diabetic renal disease, where area SES factors had an even larger influence.

6. Environmental exposures

Factors responsible for the increased incidence and severity of SLE in disadvantaged populations may also be driving increased severity of disease and poorer survival in these groups. As with many complex diseases, environmental exposures likely trigger disease development, in particular in individuals who are genetically predisposed82. Disadvantaged groups may have higher rates of incident SLE and of SLE progression due to both genetic and environmental factors. Cigarette smoking and exposure to occupational and agricultural silica, as well as use of exogenous reproductive hormones among women, have been associated with increased risk of developing SLE in epidemiologic studies83–86. Smoking is associated with more severe SLE and worse outcomes from lupus nephritis in several studies87–89, as has hypertension87, 90, 91. Differential rates of comorbidities such as smoking, obesity and hypertension may explain some of observed sociodemographic disparities in SLE. Exposures to infectious agents, occupational hazards, pollutants, drugs, dietary, cosmetic or recreational factors that could heighten SLE risk could very likely be related to socioeconomic position.

Conclusion

Alarming sociodemographic disparities in the incidence and severity of SLE have been documented. Their causes are multifactorial and SES-related factors play a large role. The complex effects of SES include access to appropriate medical care with delayed and poorer quality healthcare, poor medical understanding and medication adherence, and lower self-efficacy and confidence in the healthcare system and its providers.

W. E. B. Du Bois prophetically declared at the beginning of this century that, “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line”92. DuBois also wrote, “To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars, is the very bottom of hardships”92. Belonging to a racial or ethnic minority group and having low socioeconomic status are significant predictors of increased risk of SLE and poor SLE outcomes even today.

Recent research has identified factors that may contribute to these observed disparities in SLE, including, but not limited to education, adherence, social support, medical insurance type, geographic area of residence, access to high volume hospitals and physicians, and potential environmental exposures. This research suggests we should focus on healthcare access, education and increasing disease awareness and adherence among high-risk patients, concentrating on regular follow-up and adherence to therapy. We should also develop strategic interventions designed to eliminate these disparities aimed at the barriers research has shown to exist. Developing teams of experienced physicians, educators and caregivers, working with patients and their loved ones to strengthen social support, enhance self-efficacy, decrease comorbidities such as smoking, hypertension and obesity, and increase adherence would be a good start 50.

References

- 1.Sundquist J, Johansson SE. The influence of socioeconomic status, ethnicity and lifestyle on body mass index in a longitudinal study. International journal of epidemiology. 1998;27(1):57–63. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agodoa L, Norris K, Pugsley D. The disproportionate burden of kidney disease in those who can least afford it. Kidney Int Suppl. 2005;(97):S1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shai I, Jiang R, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Hu FB. Ethnicity, obesity, and risk of type 2 diabetes in women: a 20-year follow-up study. Diabetes care. 2006;29(7):1585–90. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.House JS. Understanding social factors and inequalities in health: 20th century progress and 21st century prospects. Journal of health and social behavior. 2002;43(2):125–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241(4865):540–5. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NIH Conference on Understanding and Reducing Disparities in Health: Behavioral and Social Sciences Research Contributions. 2006 (Accessed at http://obssr.od.nih.gov/HealthDisparities/presentation.html.); 2006.

- 7.Odutola J, Ward MM. Ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in health among patients with rheumatic disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17(2):147–52. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000151403.18651.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rom M, Fins JJ, Mackenzie CR. Articulating a justice ethic for rheumatology: A critical analysis of disparities in rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(8):1343–5. doi: 10.1002/art.23110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uramoto KM, Michet CJ, Jr, Thumboo J, Sunku J, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Trends in the incidence and mortality of systemic lupus erythematosus, 1950–1992. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(1):46–50. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199901)42:1<46::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trends in deaths from systemic lupus erythematosus--United States, 1979–1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(17):371–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarty DJ, Manzi S, Medsger TA, Jr, Ramsey-Goldman R, LaPorte RE, Kwoh CK. Incidence of systemic lupus erythematosus. Race and gender differences. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(9):1260–70. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper GS, Parks CG, Treadwell EL, St Clair EW, Gilkeson GS, Cohen PL, Roubey RA, Dooley MA. Differences by race, sex and age in the clinical and immunologic features of recently diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus patients in the southeastern United States. Lupus. 2002;11(3):161–7. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu161oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alarcon GS, Friedman AW, Straaton KV, Moulds JM, Lisse J, Bastian HM, McGwin G, Jr, Bartolucci AA, Roseman JM, Reveille JD. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: III. A comparison of characteristics early in the natural history of the LUMINA cohort. LUpus in MInority populations: NAture vs. Nurture. Lupus. 1999;8(3):197–209. doi: 10.1191/096120399678847704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaslow RA, Masi AT. Age, sex, and race effects on mortality from systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1978;21(4):473–9. doi: 10.1002/art.1780210412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reveille JD, Bartolucci A, Alarcon GS. Prognosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Negative impact of increasing age at onset, black race, and thrombocytopenia, as well as causes of death. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(1):37–48. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Studenski S, Allen NB, Caldwell DS, Rice JR, Polisson RP. Survival in systemic lupus erythematosus. A multivariate analysis of demographic factors. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30(12):1326–32. doi: 10.1002/art.1780301202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopkinson ND, Jenkinson C, Muir KR, Doherty M, Powell RJ. Racial group, socioeconomic status, and the development of persistent proteinuria in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59(2):116–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.2.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boddaert J, Huong DL, Amoura Z, Wechsler B, Godeau P, Piette JC. Late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a personal series of 47 patients and pooled analysis of 714 cases in the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004;83(6):348–59. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000147737.57861.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchez-Guerrero J, Villegas A, Mendoza-Fuentes A, Romero-Diaz J, Moreno-Coutino G, Cravioto MC. Disease activity during the premenopausal and postmenopausal periods in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med. 2001;111(6):464–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00885-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward MM. Changes in the incidence of end-stage renal disease due to lupus nephritis, 1982–1995. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(20):3136–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.20.3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lockshin MD. Biology of the sex and age distribution of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(4):608–11. doi: 10.1002/art.22676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ginzler EM, Diamond HS, Weiner M, Schlesinger M, Fries JF, Wasner C, Medsger TA, Jr, Ziegler G, Klippel JH, Hadler NM, Albert DA, Hess EV, Spencer-Green G, Grayzel A, Worth D, Hahn BH, Barnett EV. A multicenter study of outcome in systemic lupus erythematosus. I. Entry variables as predictors of prognosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25(6):601–11. doi: 10.1002/art.1780250601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petri M, Perez-Gutthann S, Longenecker JC, Hochberg M. Morbidity of systemic lupus erythematosus: role of race and socioeconomic status. Am J Med. 1991;91(4):345–53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90151-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barr RG, Seliger S, Appel GB, Zuniga R, D’Agati V, Salmon J, Radhakrishnan J. Prognosis in proliferative lupus nephritis: the role of socio-economic status and race/ethnicity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18(10):2039–46. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward MM, Studenski S. Clinical manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Identification of racial and socioeconomic influences. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(4):849–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutcliffe N, Clarke AE, Gordon C, Farewell V, Isenberg DA. The association of socio-economic status, race, psychosocial factors and outcome in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38(11):1130–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.11.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waters TM, Chang RW, Worsdall E, Ramsey-Goldman R. Ethnicity and access to care in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. 1996;9(6):492–500. doi: 10.1002/art.1790090611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Bastian HM, Roseman J, Lisse J, Fessler BJ, Friedman AW, Reveille JD. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. VII [correction of VIII]. Predictors of early mortality in the LUMINA cohort. LUMINA Study Group. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(2):191–202. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)45:2<191::AID-ANR173>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastian HM, Roseman JM, McGwin G, Jr, Alarcon GS, Friedman AW, Fessler BJ, Baethge BA, Reveille JD. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XII. Risk factors for lupus nephritis after diagnosis. Lupus. 2002;11(3):152–60. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu158oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calvo-Alen J, Vila LM, Reveille JD, Alarcon GS. Effect of ethnicity on disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(5):962–3. author reply 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alarcon GS, Bastian HM, Beasley TM, Roseman JM, Tan FK, Fessler BJ, Vila LM, McGwin G., Jr Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multi-ethnic cohort (LUMINA) XXXII: [corrected] contributions of admixture and socioeconomic status to renal involvement. Lupus. 2006;15(1):26–31. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2260oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Sanchez ML, Bastian HM, Fessler BJ, Friedman AW, Baethge BA, Roseman J, Reveille JD. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XIV. Poverty, wealth, and their influence on disease activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(1):73–7. doi: 10.1002/art.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33•.Fernandez M, Alarcon GS, Calvo-Alen J, Andrade R, McGwin G, Jr, Vila LM, Reveille JD. A multiethnic, multicenter cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) as a model for the study of ethnic disparities in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(4):576–84. doi: 10.1002/art.22672. This important study documents the racial and ethnic disparities that exist in lupus. Using a diverse cohort of patients, LUMINA investigators concluded that clinical factors including environmental, socioeconomic, psychosocial, and genetic factors contribute to the ethnic disparities observed in SLE. This study also offers recommendations, interventions and future research to improve these inequalities. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walsh SJ, DeChello LM. Geographical variation in mortality from systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States. Lupus. 2001;10(9):637–46. doi: 10.1191/096120301682430230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walsh SJ, Gilchrist A. Geographical clustering of mortality from systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States: contributions of poverty, Hispanic ethnicity and solar radiation. Lupus. 2006;15(10):662–70. doi: 10.1191/0961203306071455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Lee CH. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2004. US Census, Current Population Reports 2005. :P60–229. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krishnan E, Hubert HB. Ethnicity and mortality from systemic lupus erythematosus in the US. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(11):1500–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.040907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, Schaller JG, Talal N, Winchester RJ. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25(11):1271–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertoli AM, Vila LM, Reveille JD, Alarcon GS. Systemic lupus erythaematosus in a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA) LIII: disease expression and outcome in acute onset lupus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(4):500–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Duran S, Apte M, Alarcon GS. Poverty, not ethnicity, accounts for the differential mortality rates among lupus patients of various ethnic groups. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(10):1196–8. This editorial comments on the latest findings in the research on lupus disparities. They suggest that poverty, a modifiable factor, accounts for the differences in mortality outcomes and health disparities more than ethnicity or genetics. However, due to the intricate relationship between socioeconomic status and ethnicity, clinicians must be extremely attentive when caring for SLE patients from low socioeconomic backgrounds and/or ethnic minority groups since they pose a greater risk for developing negative outcomes. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bastian HM, Alarcon GS, Roseman JM, McGwin G, Jr, Vila LM, Fessler BJ, Reveille JD. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA) XL II: factors predictive of new or worsening proteinuria. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(4):683–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jr, Petri M, Ramsey-Goldman R, Fessler BJ, Vila LM, Edberg JC, Reveille JD, Kimberly RP. Time to renal disease and end-stage renal disease in PROFILE: a multiethnic lupus cohort. PLoS medicine. 2006;3(10):e396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Apte M, McGwin G, Jr, Vila LM, Kaslow RA, Alarcon GS, Reveille JD. Associated factors and impact of myocarditis in patients with SLE from LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LV). [corrected] Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47(3):362–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bertoli AM, Fernandez M, Alarcon GS, Vila LM, Reveille JD. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic US cohort LUMINA (XLI): factors predictive of self-reported work disability. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(1):12–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.055343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaiamnuay S, Bertoli AM, Roseman JM, McGwin G, Apte M, Duran S, Vila LM, Reveille JD, Alarcon GS. African-American and Hispanic ethnicities, renal involvement and obesity predispose to hypertension in systemic lupus erythematosus: results from LUMINA, a multiethnic cohort (LUMINAXLV) Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(5):618–22. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.059311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lotstein DS, Ward MM, Bush TM, Lambert RE, van Vollenhoven R, Neuwelt CM. Socioeconomic status and health in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(9):1720–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kasitanon N, Magder LS, Petri M. Predictors of survival in systemic lupus erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85(3):147–56. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000224709.70133.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Lew RA, Wright EA, Partridge AJ, Roberts WN, Stern SH, Straaton KV, Wacholtz MC, Grosflam JM, et al. The independence and stability of socioeconomic predictors of morbidity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(2):267–73. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang MH, Partridge AJ, Daltroy LH, Straaton KV, Galper SR, Holman HR. Strategies for reducing excess morbidity and mortality in blacks with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34(9):1187–96. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Lew RA, Wright EA, Partridge AJ, Fossel AH, Roberts WN, Stern SH, Straaton KV, Wacholtz MC, Kavanaugh AF, Grosflam JM, Liang MH. The relationship of socioeconomic status, race, and modifiable risk factors to outcomes in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(1):47–56. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ward MM. Education level and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): evidence of underascertainment of deaths due to SLE in ethnic minorities with low education levels. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(4):616–24. doi: 10.1002/art.20526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andrade R, Sanchez ML, Alarcon GS, Fessler BJ, Fernandez M, Bertoli AM, Apte M, Vila LM, Arango AM, Reveille JD. Adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with systemic lupus erythematosus from a multiethnic US cohort: LUMINA (LVI) Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26(2):268–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ward MM, Sundaramurthy S, Lotstein D, Bush TM, Neuwelt CM, Street RL., Jr Participatory patient-physician communication and morbidity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(6):810–8. doi: 10.1002/art.11467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karlson EW, Liang MH, Eaton H, Huang J, Fitzgerald L, Rogers MP, Daltroy LH. A randomized clinical trial of a psychoeducational intervention to improve outcomes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(6):1832–41. doi: 10.1002/art.20279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56•.Trupin L, Tonner MC, Yazdany J, Julian LJ, Criswell LA, Katz PP, Yelin E. The Role of Neighborhood and Individual Socioeconomic Status in Outcomes of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2008 Sep;35(9):1782–8. Neighborhood socioeconomic status was correlated with high depressive symptoms in patients with SLE. Individual SES was also related to greater disease activity, poor physical functioning and depressive behavior/symptoms. This is an important new study highlighting the role of neighborhood status in SLE outcomes. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bertoli AM, Fernandez M, Calvo-Alen J, Vila LM, Sanchez ML, Reveille JD, Alarcon GS. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic U.S. cohort (LUMINA) XXXI: factors associated with patients being lost to follow-up. Lupus. 2006;15(1):19–25. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2257oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ward MM. Medical insurance, socioeconomic status, and age of onset of endstage renal disease in patients with lupus nephritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(10):2024–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ward MM, Leigh JP, Fries JF. Progression of functional disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Associations with rheumatology subspecialty care. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(19):2229–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yelin EH, Such CL, Criswell LA, Epstein WV. Outcomes for persons with rheumatoid arthritis with a rheumatologist versus a non-rheumatologist as the main physician for this condition. Med Care. 1998;36(4):513–22. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199804000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lafata JE, Martin S, Morlock R, Divine G, Xi H. Provider type and the receipt of general and diabetes-related preventive health services among patients with diabetes. Med Care. 2001;39(5):491–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valderrabano F, Golper T, Muirhead N, Ritz E, Levin A. Chronic kidney disease: why is current management uncoordinated and suboptimal? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16 (Suppl 7):61–4. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.suppl_7.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Avorn J, Winkelmayer WC, Bohn RL, Levin R, Glynn RJ, Levy E, Owen W., Jr Delayed nephrologist referral and inadequate vascular access in patients with advanced chronic kidney failure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(7):711–6. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Winkelmayer WC, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Mittleman MA, Pliskin JS, Avorn J. Late nephrologist referral and access to renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73(12):1918–23. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200206270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Winkelmayer WC, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Owen W, Jr, Avorn J. Late referral and modality choice in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001;60(4):1547–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Winkelmayer WC, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Owen WF, Jr, Avorn J. Determinants of delayed nephrologist referral in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38(6):1178–84. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.29207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67•.Yazdany J, Gillis JZ, Trupin L, Katz P, Panopalis P, Criswell LA, Yelin E. Association of socioeconomic and demographic factors with utilization of rheumatology subspecialty care in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(4):593–600. doi: 10.1002/art.22674. This study analyzed the relationship between socioeconomic and demographic factors including income, education, age, race, ethnicity, and sex in the utilization of rheumatology subspeciality care in SLE. Although race and educational level were not associated with visiting a rheumatologist, older age. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68•.Gillis JZ, Yazdany J, Trupin L, Julian L, Panopalis P, Criswell LA, Katz P, Yelin E. Medicaid and access to care among persons with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(4):601–7. doi: 10.1002/art.22671. This study evaluated the association between SLE patients’ type of health insurance and the distances they traveled to see a physician. Medicaid patients with SLE traveled longer distances to see an SLE physician suggesting that these patients may face challenges in obtaining quality and comprehensive care in proximity to their residences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69•.Yelin E, Trupin L, Katz P, Criswell LA, Yazdany J, Gillis J, Panopalis P. Impact of health maintenance organizations and fee-for-service on health care utilization among people with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(3):508–15. doi: 10.1002/art.22625. A survey of 982 SLE patients compared the health care utilization of patients enrolled in health maintenance organizations (HMO) to those with fee-for-service (FFS) health plans. Their results suggest that patients with SLE in HMOs utilized substantially less ambulatory care and were less likely to have outpatient surgery and hospital admissions than those in FFS. This study is important in highlighting the influence of insurance type on SLE outcomes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brookhart MA, Patrick AR, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, Dormuth C, Shrank W, van Wijk BL, Cadarette SM, Canning CF, Solomon DH. Physician follow-up and provider continuity are associated with long-term medication adherence: a study of the dynamics of statin use. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):847–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ward MM. Hospital experience and mortality in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(5):891–8. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<891::AID-ANR7>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ward MM. Association between physician volume and in-hospital mortality in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(6):1646–54. doi: 10.1002/art.21053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73•.Ward MM. Avoidable hospitalizations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(2):162–8. doi: 10.1002/art.23346. Avoidable hospitalizations can indicate underutilization or poor access to health care. In this study, avoidable hospitalizations occurred more commonly among older and poorer SLE patients. These avoidable hospital visits suggest inequity and inefficiency in the health care delivery system and more specifically in the treatment of older and socio-economically disadvantaged lupus patients. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74•.Anderson E, Nietert PJ, Kamen DL, Gilkeson GS. Ethnic disparities among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in South Carolina. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(5):819–25. When compared to Caucasians and after controlling for co-morbidities, African American SLE patients in South Carolina had a greater risk of in-hospital mortality and mortality after discharge possibly reflecting the existing inequalities of access and quality of care for people of different ethnic backgrounds. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(11):1783–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2002;21(2):60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Choosing area based socioeconomic measures to monitor social inequalities in low birth weight and childhood lead poisoning: The Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project (US) Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2003;57(3):186–99. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.3.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rodriguez RA, Sen S, Mehta K, Moody-Ayers S, Bacchetti P, O’Hare AM. Geography matters: relationships among urban residential segregation, dialysis facilities, and patient outcomes. Annals of internal medicine. 2007;146(7):493–501. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Losina E, Wright EA, Kessler CL, Barrett JA, Fossel AH, Creel AH, Mahomed NN, Baron JA, Katz JN. Neighborhoods matter: use of hospitals with worse outcomes following total knee replacement by patients from vulnerable populations. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(2):182–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Volkova N, McClellan W, Klein M, Flanders D, Kleinbaum D, Soucie JM, Presley R. Neighborhood poverty and racial differences in ESRD incidence. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(2):356–64. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ward MM. Socioeconomic status and the incidence of ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(4):563–72. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sarzi-Puttini P, Atzeni F, Iaccarino L, Doria A. Environment and systemic lupus erythematosus: an overview. Autoimmunity. 2005;38(7):465–72. doi: 10.1080/08916930500285394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Costenbader KH, Kim DJ, Peerzada J, Lockman S, Nobles-Knight D, Petri M, Karlson EW. Cigarette Smoking and the Risk of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Meta-Analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:849–57. doi: 10.1002/art.20049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Finckh A, Cooper GS, Chibnik LB, Costenbader KH, Fraser PA, Watts J, Pankey H, Karlson EW. Occupational silica and solvent exposures and risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in urban women. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54(11):3648–54. doi: 10.1002/art.22210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Parks CG, Cooper GS, Nylander-French LA, Sanderson WT, Dement JM, Cohen PL, Dooley MA, Treadwell EL, St Clair EW, Gilkeson GS, Hoppin JA, Savitz DA. Occupational exposure to crystalline silica and risk of systemic lupus erythematosus: a population-based, case-control study in the southeastern United States. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(7):1840–50. doi: 10.1002/art.10368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Costenbader KH, Feskanich D, Stampfer MJ, Karlson EW. Reproductive and menopausal factors and risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in women. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(4):1251–62. doi: 10.1002/art.22510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ward MM, Studenski S. Clinical prognostic factors in lupus nephritis. The importance of hypertension and smoking. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152(10):2082–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Falk RJ. Treatment of lupus nephritis--a work in progress. The New England journal of medicine. 2000;343(16):1182–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010193431610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Golbus J, McCune WJ. Lupus nephritis. Classification, prognosis, immunopathogenesis, and treatment. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1994;20(1):213–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ginzler EM, Felson DT, Anthony JM, Anderson JJ. Hypertension increases the risk of renal deterioration in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(10):1694–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.de Castro WP, Morales JV, Wagner MB, Graudenz M, Edelweiss MI, Goncalves LF. Hypertension and Afro-descendant ethnicity: a bad interaction for lupus nephritis treated with cyclophosphamide? Lupus. 2007;16(9):724–30. doi: 10.1177/0961203307081114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.DuBois WEB. The Souls of Black Folk. Cambridge, MA: University Press; 1903. [Google Scholar]